Abstract

BINGO (BAO from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations) is a unique radio telescope designed to map the intensity of neutral hydrogen distribution at cosmological distances, making the first detection of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO) in the frequency band 980 MHz - 1260 MHz, corresponding to a redshift range 0.127 < z < 0.449. BAO is one of the most powerful probes of cosmological parameters and BINGO was designed to detect the BAO signal to a level that makes it possible to put new constraints on the equation of state of dark energy. The telescope will be built in Paraíba, Brazil and consists of two \(\thicksim\) 40m mirrors, a feedhorn array of 50 horns, and no moving parts, working as a drift-scan instrument. It will cover a 15\(^{\circ}\) declination strip centered at \(\sim \delta\) =-15\(^{\circ}\), mapping \(\sim\) 5400 square degrees in the sky. The BINGO consortium is led by University of São Paulo with co-leadership at National Institute for Space Research and Campina Grande Federal University (Brazil). Telescope subsystems have already been fabricated and tested, and the dish and structure fabrication are expected to start in late 2020, as well as the road and terrain preparation.

Key words

21cm cosmology; radio astronomy; baryon acoustic oscillations; BAO

Introduction

One of the main cosmological challenges in the 21st century is to explain the present acceleration in the expansion of the universe, first unequivocally inferred in 1998 by two independent groups measuring supernovae of type Ia, one led by S. Perlmutter (Perlmutter et al. 1998PERLMUTTER S, ALDERING G, DELLA VALLE M, DEUSTUA S, ELLIS RS, FABBRO S, FRUCHTER A, GOLDHABER G, GROOM DE & HOOK IM. 1998. Discovery of a supernova explosion at half the age of the Universe. Nature 391(6662): 51-54. doi:10.1038/34124.) and the other by A. Riess (Riess et al. 1998RIESS AG, FILIPPENKO AV, CHALLIS P, CLOCCHIATTI A, DIERCKS A, GARNAVICH PM, GILLILAND RL, HOGAN CJ, JHA S & KIRSHNER RP. 1998. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. Astron J 116(3): 1009-1038. doi:10.1086/300499.). This led to the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics and can be explained by postulating a negative pressure from a new component, the so-called Dark Energy (hereafter, DE). In combination with other observations, such as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), there is little doubt about the existence of such an accelerated phase and the main focus of observational cosmology is now to try to determine its detailed properties.

Among the various programs to measure those properties, Baryonic Acoustic Oscillations (BAO) are recognised as one of the most powerful probes of the properties of DE (e.g. Albrecht et al. 2006ALBRECHT A ET AL. 2006. Report of the Dark Energy Task Force. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 0609591., Weinberg et al. 2013WANG B, ZANG J, LIN CY, ABDALLA E & MICHELETTI S. 2007. Interacting dark energy and dark matter: Observational constraints from cosmological parameters. Nucl Phys B 778(1-2): 69-84. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.04.037.). BAO are a signature in the matter distribution from the recombination epoch and are imprinted in the distribution of galaxies at redshifts less than that of the epoch of reionization (\(z \lesssim\) 0.5). In the context of the standard cosmological model (\(\Lambda\textrm{CDM}\) model), BAO can be identified as a small but detectable excess of galaxies with separations of order of 150 Mpc.h-1 (Anderson et al. 2014ANDERSON L ET AL. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Releases 10 and 11 Galaxy samples. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441(1): 24-62. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu523., Eisenstein et al. 2005EISENSTEIN DJ ET AL. 2005. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. Astrophys J 633: 560-574. doi:10.1086/466512., Planck Collaboration et al. 2018PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2018. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1807.06209: arXiv:1807.06209.). This excess is the imprint of the acoustic oscillations generated during CMB times and its linear scale is known from basic physics. Consequently, a measure of its angular scale can be used to determine the distance up to a given redshift. The same oscillations produce the familiar peaks observed in the CMB anisotropy power spectrum.

To date, BAOs have only been detected by performing large galaxy redshift surveys in the optical waveband, where they are used as tracers of the underlying total matter distribution. It is important they are confirmed in other wavebands and measured over a wide range of redshifts. Since optical surveys demand more time to detect individual galaxies and cover a relatively small fraction of the sky, just a few percent of the local volume has been mapped with such a type of technique. The radio band provides a complementary observational window for studying BAO, and the natural radio tracer is the redshifted 21cm emission line. However, the volume emissivity associated with this line is low, meaning that detecting individual galaxies up to \(z \sim 0.5\) requires a very substantial collecting area. It has been proposed that mapping the Universe measuring the collective 21cm emission of the underlying matter distribution, using a technique known as intensity mapping, hereafter IM (Loeb & Wyithe 2008LOEB A & WYITHE JSB. 2008. Possibility of Precise Measurement of the Cosmological Power Spectrum with a Dedicated Survey of 21 cm Emission after Reionization. Phys Rev Lett 100: 161301., Masui et al. 2013MASUI KW ET AL. 2013. Measurement of 21 cm Brightness Fluctuations at z \sim 0.8∼0.8 in Cross-correlation. Astrophys J Lett 763: L20. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/763/1/L20., Peterson et al. 2006PETERSON JB, BANDURA K & PEN UL. 2006. The Hubble Sphere Hydrogen Survey. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 0606104., Switzer et al. 2013SWITZER ER ET AL. 2013. Determination of z \sim 0.8∼0.8 neutral hydrogen fluctuations using the 21 cm intensity mapping autocorrelation. Mon Not R Astron Soc 434: L46-L50. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt074.), can be many times more efficient than optical surveys (e.g., Chang et al. 2008CHANG TC, PEN UL, PETERSON JB & MCDONALD P. 2008. Baryon Acoustic Oscillation Intensity Mapping as a Test of Dark Energy. Phys Rev Lett 100: 091303. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.091303., Loeb & Wyithe 2008LOEB A & WYITHE JSB. 2008. Possibility of Precise Measurement of the Cosmological Power Spectrum with a Dedicated Survey of 21 cm Emission after Reionization. Phys Rev Lett 100: 161301.).

The BINGO (BAO from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations) telescope is a new instrument designed specifically for observing BAO in frequency band around \(1~{\rm GHz}\) and to provide a new insight into the Universe at \(0.13 \lesssim z \lesssim 0.45\) with a dedicated instrument. The optical configuration consists of a compact, two 40m diameter, static dishes with an exceptionally wide field-of-view (\(\sim\) 12\(^{\circ}\) \(\times\) 10\({^\circ}\)) and 50 feed horns in the focal plane. BAO observations will be carried through IM HI surveys (see, e.g., Peterson et al. 2006PETERSON JB, BANDURA K & PEN UL. 2006. The Hubble Sphere Hydrogen Survey. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 0606104.). BINGO’s main scientific goal is to claim the first BAO detection in radio in this redshift range, mapping the three dimensional distribution of HI, yielding a fundamental contribution to the study of DE, with observations spanning several years. No detection of BAOs in radio has been claimed so far, making BINGO an interesting and appealing instrument in the years to come. Moreover, in view of the observation strategy and with some adjustment in its digital backend, BINGO will also be capable to detect transient phenomena at very short time scales (\(\lesssim 1~{\rm ms}\)), such as pulsars and Fast Radio Bursts (FRB, Cordes & Chatterjee 2019CORDES JM & CHATTERJEE S. 2019. Fast radio bursts: an extragalactic enigma. Ann Rev Astron Astrophys 57: 417-465., Lorimer et al., 2007LORIMER DR, BAILES M, MCLAUGHLIN MA, NARKEVIC DJ & CRAWFORD F. 2007. A Bright Millisecond Radio Burst of Extragalactic Origin. Science 318: 777. doi:10.1126/science.1147532..

Earlier versions of the BINGO telescope concept are described in Battye et al. 2013BATTYE RA, BROWN ML, BROWNE IWA, DAVIS RJ, DEWDNEY P, DICKINSON C, HERON G, MAFFEI B, POURTSIDOU A & WILKINSON PN. 2012. BINGO: a single dish approach to 21cm intensity mapping. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1209.1041. and Wuensche & the BINGO Collaboration 2019WUENSCHE CA & THE BINGO COLLABORATION. 2019. The BINGO telescope: a new instrument exploring the new 21 cm cosmology window. In: Journal of Physics Conference Series. Journal of Physics Conference Series, vol. 1269, p. 012002. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1269/1/012002. and a comprehensive analysis of foregrounds and \(1/f\) noise that can limit the BINGO performance was published by Bigot-Sazy et al. 2015BIGOT-SAZY MA, DICKINSON C, BATTYE RA, BROWNE IWA, MA YZ, MAFFEI B, NOVIELLO F, REMAZEILLES M & WILKINSON PN. 2015. Simulations for single-dish intensity mapping experiments. Mon Not R Astron Soc 454(3): 3240-3253. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2153.. The Project Design Review that ocurred in July 2019 fixed the telescope location in the hills of “Serra do Urubu“ in the municipality of Aguiar, Paraíba, Brazil (Lon: \(38^{\circ}~16'~4.8``\) W, Lat: \(7^{\circ}~2'~27,6``\)S). It presents a very clean radio environment, as reported by Peel and collaborators (Peel et al. 2019PEEL MW ET AL. 2019. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: Radio Frequency Interference Measurements and Telescope Site Selection. Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation 8(1): 1940005. doi:10.1142/S2251171719400051.), which is one of the most critical requirements for high-quality measurements.

The main institutions in the BINGO consortium are: University of São Paulo (USP), National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and Campina Grande Federal University (UFCG), in Brazil, University of Manchester and University College London (United Kingdom), and Yang Zhou University (China). This paper reports the current status of the BINGO project as of June 2020 as presented in the BRICS Astronomy Working Group in October, 2019.

Science Goals

Recent observational results have been useful in shedding new light onto aspects of dark matter and DE, which comprise about 95% of the mass of the Universe, and it is expected that maybe a new physical picture emerges once we find more about the structure of the Dark Sector (Abdalla et al. 2010ABDALLA FB, BLAKE C & RAWLINGS S. 2010. Forecasts for Dark Energy Measurements with Future HI Surveys. Mon Not R Astron Soc 401: 743. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15704.x.). BAO studies are one of the most powerful probes of the properties of DE (see, e.g., Albrecht et al. 2006ALBRECHT A ET AL. 2006. Report of the Dark Energy Task Force. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 0609591., Weinberg et al. 2013WANG B, ZANG J, LIN CY, ABDALLA E & MICHELETTI S. 2007. Interacting dark energy and dark matter: Observational constraints from cosmological parameters. Nucl Phys B 778(1-2): 69-84. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.04.037.) and have only been probed by optical galaxy redshift surveys (see, e.g., Anderson et al. 2014ANDERSON L ET AL. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Releases 10 and 11 Galaxy samples. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441(1): 24-62. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu523., Eisenstein et al., 2005EISENSTEIN DJ ET AL. 2005. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. Astrophys J 633: 560-574. doi:10.1086/466512., Percival et al. 2010PERCIVAL WJ ET AL. 2010. Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 7 galaxy sample. Mon Not R Astron Soc 401(4): 2148-2168. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15812.x., Reid et al. 2015REID B ET AL. 2015. SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey Data Release 12: galaxy target selection and large-scale structure catalogues. Mon Not R Astron Soc 455(2): 1553-1573., Tojeiro et al. 2014TOJEIRO R, ROSS AJ, BURDEN A, SAMUSHIA L, MANERA M, PERCIVAL WJ, BEUTLER F, BRINKMANN J, BROWNSTEIN JR & CUESTA AJ. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: galaxy clustering measurements in the low-redshift sample of Data Release 11. Mon Not R Astron Soc 440(3): 2222-2237. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu371.).

Constraints on various existing DE models (see, e.g., Feng et al. 2008FENG C, WANG B, ABDALLA E & SU R. 2008. Observational constraints on the dark energy and dark matter mutual coupling. Phys Lett B 665(2-3): 111-119. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.05.066., Ferreira et al. 2017FERREIRA EGM, QUINTIN J, COSTA AA, ABDALLA E & WANG B. 2017. Evidence for interacting dark energy from BOSS. Phys Rev D 95(4): 043520. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.95.043520., He et al. 2009HE JH, WANG B & ABDALLA E. 2009. Stability of the curvature perturbation in dark sectors’ mutual interacting models. Phys Lett B 671(1): 139-145. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.11.062., 2011HE JH, WANG B & ABDALLA E. 2011. Testing the interaction between dark energy and dark matter via the latest observations. Phys Rev D 83: 063515. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.83.063515. URL https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.83.063515., Micheletti et al. 2009MICHELETTI S, ABDALLA E & WANG B. 2009. A Field Theory Model for Dark Matter and Dark Energy in Interaction. Phys Rev D D79: 123506. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.79.123506., Wang et al., 2005VIEIRA FAS. 2020. Protótipo de radiômetro simples para pesquisa em Fast Radio Bursts com o radiotelescópio BINGO. Master’s thesis. INPE. (Unpublished)., 2007WANG B, GONG Y & ABDALLA E. 2005. Transition of the dark energy equation of state in an interacting holographic dark energy model. Phys Lett B 624(3-4): 141-146. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.08.008.) coming from BAO measurements break the degeneracies between cosmological parameters that are present when inferring them from the CMB observations. This potentially allows to constrain extensions of the standard cosmological model which are usually degenerate with the Hubble constant.

Following the first detection of BAOs using SDSS surveys (Eisenstein et al. 2005EISENSTEIN DJ ET AL. 2005. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. Astrophys J 633: 560-574. doi:10.1086/466512.), BAOs have been measured with several new generation galaxy and quasar redshift surveys. In particular, the recent measurements with the BOSS survey achieve a precision in the BAO scale of a few percent in the redshift range \(z = [0, 2]\)(Anderson et al. 2014ANDERSON L ET AL. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Releases 10 and 11 Galaxy samples. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441(1): 24-62. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu523., Reid et al. 2015REID B ET AL. 2015. SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey Data Release 12: galaxy target selection and large-scale structure catalogues. Mon Not R Astron Soc 455(2): 1553-1573., Tojeiro et al. 2014TOJEIRO R, ROSS AJ, BURDEN A, SAMUSHIA L, MANERA M, PERCIVAL WJ, BEUTLER F, BRINKMANN J, BROWNSTEIN JR & CUESTA AJ. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: galaxy clustering measurements in the low-redshift sample of Data Release 11. Mon Not R Astron Soc 440(3): 2222-2237. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu371.). New large experiments are being designed or are already under construction to refine BAO measurements in the optical band, such as DESI (Aghamousa et al. 2016AGHAMOUSA A ET AL. 2016a. The DESI Experiment Part I: Science,Targeting, and Survey Design. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1611.00036., 2016AGHAMOUSA A ET AL. 2016b. The DESI Experiment Part II: Instrument Design. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1611.00037.), Euclid (Refregier et al. 2010REFREGIER A, AMARA A, KITCHING TD, RASSAT A, SCARAMELLA R & WELLER J. 2010. Euclid Imaging Consortium Science Book. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1001.0061.) and WFIRST (Green & others 2011GREEN J ET AL. 2011. Wide-Field InfraRed Survey Telescope (WFIRST) Interim Report. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1108.1374., Levi et al. 2011LEVI ME, KIM AG, LAMPTON ML & SHOLL MJ. 2011. Science Yield of an Improved Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST). arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1105.0959.), as well as LSST for imaging (Tyson et al. 2002TYSON T, WITTMAN D, HENNAWI J & SPERGEL D. 2002. LSST as a precision probe of dark energy. In: APS April Meeting Abstracts. APS Meeting Abstracts. p. Y6.004.). Their goal is to achieve a precision below the percent level at higher redshifts. Nevertheless, all of them are large endeavours and the first light of any of them is not expected before the mid-2020’s decade.

This is why it is so important that the current results are confirmed in other wavebands and measured over a wide range of redshifts. The radio band provides a unique and complementary observational window for the understanding of DE via measurements of integrated redshifted 21cm hydrogen emission line (Abdalla et al. 2010ABDALLA FB, BLAKE C & RAWLINGS S. 2010. Forecasts for Dark Energy Measurements with Future HI Surveys. Mon Not R Astron Soc 401: 743. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15704.x.). HI redshift data allow us to construct a unique three dimensional map of the mass distribution, with a different perspective compared to the data obtained with optical telescopes. Indeed, HI is expected to be one of the best tracers of the total matter (see, e.g., Padmanabhan et al. 2015PADMANABHAN H, CHOUDHURY TR & REFREGIER A. 2015. Theoretical and observational constraints on the H I intensity power spectrum. Mon Not R Astron Soc 447(4): 3745-3755. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2702.).

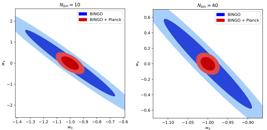

The combination of BAO radio measurements with other data sets (for instance, CMB and optical BAO) can be a powerful strategy to put more stringent constraints in the cosmological parameters analysis. Fig. 1 shows the forecast of the constraints from BINGO, combined with other data sets, for the time dependent parametrisation the equation of state of the DE with \(w_{0}\) and \(w_a\) (\(1^{st}\) time derivative of \(w_{0}\)) for various data sets. The constraints were computed using the Fisher matrix approach as described by Bull et al. 2015BULL P, FERREIRA PG, PATEL P & SANTOS MG. 2015. Late-time Cosmology with 21 cm Intensity Mapping Experiments. Astrophys J 803(1): 21. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/803/1/21..

Constraints on DE equation of state, including forecasts from CHIME and BINGO. Note the tight error elipse obtained with combined radio data (BAO from CHIME and BINGO + Planck).

The plot shows the improvement in the constraints obtained with the combination of simulated results from BINGO and CHIME (Newburgh et al. 2014NEWBURGH LB, ADDISON GE, AMIRI M, BANDURA K, BOND JR, CONNOR L, CLICHE JF, DAVIS G, DENG M & DENMAN N. 2014. Calibrating CHIME: a new radio interferometer to probe dark energy. In: Ground-based and Airborne Telescopes V. Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Conference Series.) , compared to the current constraints given by the combination of the results of the Planck and WMAP satellites (Bennett et al. 2013BENNETT CL ET AL. 2013. Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results. Astrophys J Supp 208: 20. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20., Planck Collaboration et al. 2014PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2014. Planck 2013 results. XVI. Cosmological parameters. Astron Astrophys 571: A16. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321591., 2016PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2016. Planck 2015 results. I. Overview of products and scientific results. Astron Astrophys 594: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527101., 2018PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2018. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1807.06209: arXiv:1807.06209.), with the optical galaxy surveys (BOSS (Anderson et al. 2014ANDERSON L ET AL. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Releases 10 and 11 Galaxy samples. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441(1): 24-62. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu523., Tojeiro et al. 2014TOJEIRO R, ROSS AJ, BURDEN A, SAMUSHIA L, MANERA M, PERCIVAL WJ, BEUTLER F, BRINKMANN J, BROWNSTEIN JR & CUESTA AJ. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: galaxy clustering measurements in the low-redshift sample of Data Release 11. Mon Not R Astron Soc 440(3): 2222-2237. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu371.), WiggleZ (Kazin et al. 2014KAZIN EA ET AL. 2014. The WiggleZ Dark Energy Survey: improved distance measurements to z = 1 with reconstruction of the baryonic acoustic feature. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441: 3524-3542. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu778.) and 6dF (Beutler et al. 2011BEUTLER F, BLAKE C, COLLESS M, JONES DH, STAVELEY-SMITH L, CAMPBELL L, PARKER Q, SAUNDERS W & WATSON F. 2011. The 6dF Galaxy Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations and the local Hubble constant. Mon Not R Astron Soc 416(4): 3017-3032. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19250.x.)). For constant \(w\), the measurement would lead to an accuracy on \(w\) of \(\lesssim 8\%\) when including BINGO together with CHIME and Planck.

Tight constraints can be obtained with radio data alone (BAO from CHIME and BINGO plus Planck), providing a completely independent measurement from optical surveys. The improvement from the red to the yellow contour is due to having two independent measurements at different redshifts, showing the importance of BINGO. We have made estimates of the projected errors of the DE parameters assuming that all the other cosmological parameters are fixed. BINGO will be competitive and complementary to optical surveys, which are limited by different systematic errors.

The combination of BINGO and Planck only also place good constraints in the values of the equation of state of DE. In figure 2 we compare the \(68 \%\) and \(95 \%\) confidence levels constraints on the parameters of the DE equation of state using BINGO alone and BINGO plus Planck. The constraints improve with increasing number of redshift bins. Those figures can be compared with the optimal case results from Olivari et al. 2018OLIVARI LC, DICKINSON C, BATTYE RA, MA YZ, COSTA AA, REMAZEILLES M & HARPER S. 2018. Cosmological parameter forecasts for H I intensity mapping experiments using the angular power spectrum. Mon Not R Astron Soc 473: 4242-4256. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx2621.. Our marginalised \(68 \%\) c.l. constraints on the DE equation of state parameters are \(2.4 \%\) for \(w_0\) and \(\sigma_{w_a} = 0.11\). Olivari et al. obtained \(4 \%\) for a constant equation of state model.

68% and 95% confidence level constraints on the DE equation of state parameters using BINGO and BINGO + Planck. The results are show for two different number of redshift bins (Costa et al. 2021).

A more detailed work discussing the forecast methods under development for the BINGO data analysis is being developed by Costa et al. 2021COSTA A ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: cosmological forecasts. Astron Astrophys..

HI intensity mapping

Together with other experiments, IM radio surveys can become a very promising complementary route to study BAOs. Indeed, optical experiments are required to gather data with very high angular resolution (of the order of an arcsecond) to detect individual galaxies, while the BAO scale is typically of the order of a degree. On the other hand, radio BAO experiments have angular resolutions which are well matched to the BAO scale and thus offer a very low cost-effective approach. IM experiments are a more direct tracer of dark matter being less sensitive to “peak statistics“ bias. Moreover, radio experiments can use other elements/molecules (CO, \(H-{\alpha}\)) besides neutral hydrogen (Kovetz et al. 2017KOVETZ ED ET AL. 2017. Line-Intensity Mapping: 2017 Status Report. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1709.09066.), and are subject to different astrophysical effects and systematics when compared to optical surveys. The combination of their results with those obtained from optical surveys can significantly reduce systematic effects during cosmological parameter analysis.

BINGO will also use IM to map the three-dimensional distribution of HI, with observations spanning a few years. Also, an experiment such as BINGO will pave the way to the extension of the use of 21cm IM to high redshifts, opening a new window on cosmological epochs, which cannot be probed in the optical or near-infrared bands. Extensive simulations of the expected BAO signal and how it can be extracted are currently in progress, with results to be published in the near future.

At frequencies below a few GHz the future of radio astronomy will be dominated by SKA (Square Kilometre Array) project (Maartens et al. 2015MAARTENS R, ABDALLA FB, JARVIS M & SANTOS MG. 2015. Overview of cosmology with the SKA. Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array (AASKA14) 16.), that should operating by mid-2020’s. Its design has been strongly driven to probe the HI 21cm line from its rest frequency (1420 MHz) down to 50 MHz. The great importance of the IM technique is highlighted by the decision to change the baseline design of the SKA Phase 1 to enable a IM approach (Square Kilometre Array Cosmology Science Working Group et al. 2020SQUARE KILOMETRE ARRAY COSMOLOGY SCIENCE WORKING GROUP ET AL. 2020. Cosmology with Phase 1 of the Square Kilometre Array Red Book 2018: Technical specifications and performance forecasts. Publ of the Astr Soc Asia 37: e007. doi:10.1017/pasa.2019.51.). Albeit SKA is designed to work mainly in interferometric mode, the proposed IM observations are to work in autocorrelation mode; i.e. using each dish separately, so that SKA and BINGO operation modes will be somewhat similar. Each BINGO beam will be equivalent to a single SKA dish, so that the hardware and software know-how acquired during BINGO development will be readily available to take advantage of the much larger signal to noise ratio achieved by SKA (Abdalla et al. 2015ABDALLA F, MARINS A, MOTA P, FORNAZIER K ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: optical design. Astron Astrophys., Bull et al. 2015BULL P, FERREIRA PG, PATEL P & SANTOS MG. 2015. Late-time Cosmology with 21 cm Intensity Mapping Experiments. Astrophys J 803(1): 21. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/803/1/21.).

The instrument

Interferometers are the most suitable instruments to perform IM in the angular resolution of \(\sim 0.5^{\circ}\), covering very large areas of the sky. However, they also require expensive hardware and sophisticated electronics and time-keeping systems to make the necessary correlations. A number of approaches has been proposed to conduct IM surveys using interferometer arrays rather than a single dish (see, for instance, the papers from Baker et al. 2011BAKER T, FERREIRA PG, SKORDIS C & ZUNTZ J. 2011. Towards a fully consistent parameterization of modified gravity. Phys Rev D 84: 124018. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.84.124018., Pober et al. 2013POBER JC, PARSONS AR, DEBOER DR, MCDONALD P, MCQUINN M, AGUIRRE JE, ALI Z, BRADLEY RF, CHANG TC & MORALES MF. 2013. The Baryon Acoustic Oscillation Broadband and Broad-beam Array: Design Overview and Sensitivity Forecasts. Astron J 145: 65. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/145/3/65., vanBemmel:2012cj?) and a detailed discussion about advantages and disadvantages for both was published by Bull et al. 2015BULL P, FERREIRA PG, PATEL P & SANTOS MG. 2015. Late-time Cosmology with 21 cm Intensity Mapping Experiments. Astrophys J 803(1): 21. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/803/1/21..

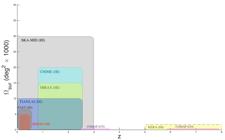

Single-dish telescopes with stable receivers can be a low-cost, good efficiency approach to BAO IM studies at redshifts (\(z \lesssim 0.5\)) (Battye et al. 2012BATTYE R ET AL. 2016. Update on the BINGO 21cm intensity mapping experiment. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1610.06826.) and BINGO belongs to this class. No detection of BAOs in radio has been claimed so far, making BINGO an interesting and appealing instrument in the years to come, with a strong potential for a pioneering discovery of the BAO in this wavelength. For comparison, we show some of the IM experiments planned for the near future, or already in operation, in Figure 3, with covered area in the sky as a function of redshift. Albeit operating in the same redshift range of TIANLAI, FAST and SKA telescopes, we believe BINGO can be still be a strong competitor, producing good quality data before their relatives.

Comparative plot of sky and redshift coverage for different IM experiments. CHIME and FAST are in operation.

The difficulty in doing a statistically significant BAO detection is due to the high intensity of the Galactic and extragalactic signals in the BINGO frequency band (\(980 \le \nu \le 1260 {\rm GHz}\) ) . The HI signal is typically \(\thicksim 100~\mu K\) whereas the foreground continuum emission from the Galaxy is \(\thicksim 1~K\) with spatial fluctuations \(\thicksim 100~mK\). Detecting signals of \(\thicksim 100~\mu K\) with a non-cryogenic receiver implies that every pixel in our intensity map requires an accumulated integration time larger than 1 day over the course of the observing campaign, which is expected to last a few years. The total integration time can be built up by many returns to the same patch of sky but between these returns the receiver gains need to be highly alike and achieving this stability is a major design concern.

Fortunately, the integrated 21cm emission exhibits characteristic variations as a function of frequency whereas the continuum emission has a very smooth spectrum; this allows for the two signals to be separated (Chang et al. 2008CHANG TC, PEN UL, PETERSON JB & MCDONALD P. 2008. Baryon Acoustic Oscillation Intensity Mapping as a Test of Dark Energy. Phys Rev Lett 100: 091303. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.091303., Chang et al. 2010CHANG TC, PEN UL, BANDURA K & PETERSON JB. 2010. An intensity map of hydrogen 21-cm emission at redshift z \sim∼ 0.8. Nature 466: 463-465. doi:10.1038/nature09187., Liu & Tegmark 2011LIU A & TEGMARK M. 2011. A Method for 21 cm Power Spectrum Estimation in the Presence of Foregrounds. Phys Rev D 83: 103006., Olivari et al. 2016OLIVARI LC, REMAZEILLES M & DICKINSON C. 2016. Extracting H I cosmological signal with generalized needlet internal linear combination. Mon Not R Astron Soc 456: 2749-2765. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2884.). However, while there is a clear-cut statistical signature that allows for the separation of different components, the design of an instrument to measure the HI contribution to the detected signal needs to be very careful. It should contemplate a very clean and symmetric beam, with low sidelobe levels and very good polarisation purity, to avoid systematic effects that can result in leakage of the Galactic foreground emission, which is partially linearly polarised and concentrated towards the Galactic plane, into the HI signal.

A declination strip of \(\thicksim 15^{\circ}\), centered at \(\delta \thicksim -15^{\circ}\) aims at minimising the Galactic foreground contamination and will be the optimal choice for the BINGO survey. The need to clearly resolve structures of angular sizes corresponding to a linear scale of around \(150~Mpc\) at BINGO’s chosen redshift range implies that the required angular resolution has to be \(\thicksim 40'\).

The general concept for the BINGO instrument is described in Battye et al. 2013BATTYE RA, BROWN ML, BROWNE IWA, DAVIS RJ, DEWDNEY P, DICKINSON C, HERON G, MAFFEI B, POURTSIDOU A & WILKINSON PN. 2012. BINGO: a single dish approach to 21cm intensity mapping. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1209.1041., Battye et al. 2016BATTYE RA, BROWNE IWA, DICKINSON C, HERON G, MAFFEI B & POURTSIDOU A. 2013. H I intensity mapping: a single dish approach. Mon Not R Astron Soc 434: 1239-1256. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1082. and updated in Wuensche & the BINGO Collaboration 2019WUENSCHE CA & THE BINGO COLLABORATION. 2019. The BINGO telescope: a new instrument exploring the new 21 cm cosmology window. In: Journal of Physics Conference Series. Journal of Physics Conference Series, vol. 1269, p. 012002. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1269/1/012002.. The current stage of the instrument construction is as follows: 1) horn prototype is completed, tested and approved for electromagnetic and mechanical performance; 2) front end, including polariser, transitions, OMT (“magic-tees“) and rectangular-to-coaxial transitions are completed, tested and approved for electromagnetic and mechanical performance; 3) the LNA and receiver chain is completed, passed the initial testing and needs to be improved for a better system temperature; 4) different LNA types are under testing to improve the first stage performance; 5) optical design is nearly completed, with the final dish parameters and focal plane arrangement simulated and tested in the mission pipeline data reduction software. The main parameters describing the telescope can be found in Table 1.

The optics

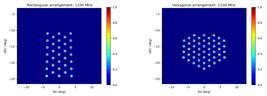

The final optical system consists of an off-axis dual mirror telescope following the Dragone-Mizuguchi condition in order to minimise the cross-polarisation. Combined with the use of corrugated feedhorns, similarly to CMB experiments, such configuration allows for low sidelobes, low spillover and superb polarisation performance. The focal plane includes 50 feed horns giving an overall field of view of 13 deg x 10 deg. The forward gain of each beam formed by the combination of the feedhorn and the telescope do not vary by more than 1 dB for all the pixels across the whole focal plane, while keeping low beam aberration and ellipticity. The current mirror and focal plane configuration are found in figure 4. Since the smallest operational wavelength is \(23.8\)cm, the surface profile of the telescope mirrors should have an \(rms\) error \(\lesssim~15\) mm to allow for maximum efficiency. The final optical design is described in the work of Abdalla et al. 2021ABDALLA FB, BULL P, CAMERA S, BENOIT-LÉVY A, JOACHIMI B, KIRK D, KLOECKNER HR, MAARTENS R, RACCANELLI A & SANTOS MG. 2015. Cosmology from HI galaxy surveys with the SKA. In: Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array (AASKA14), p. 17..

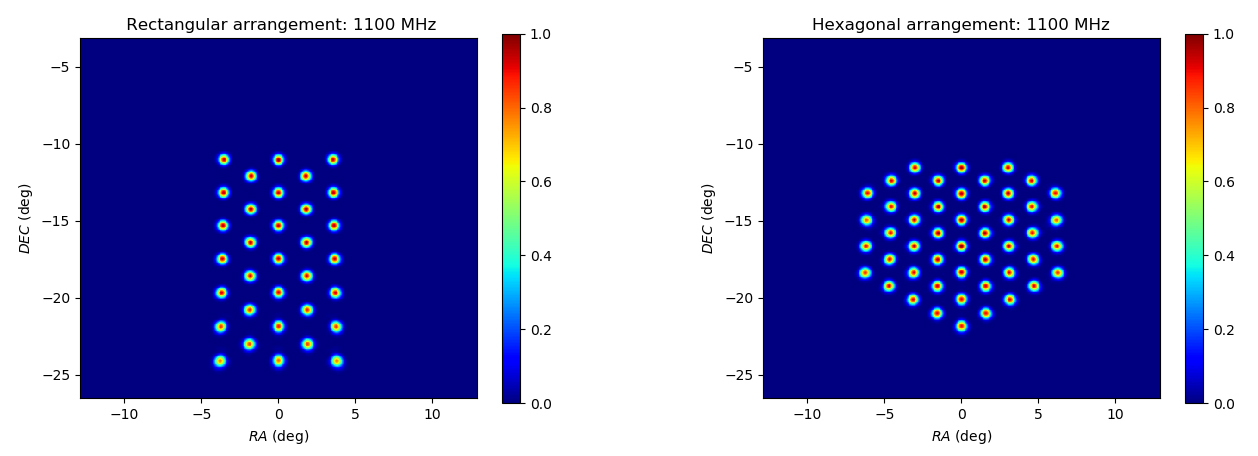

The gain of the telescope beams associated with the feed horns at the edge of the array are less than 1 dB lower compared with those from the horns at the centre; optical aberrations are slight, the edge beams being almost circular. Various arrangements for the horns in the focal plane were simulated in order to achieve an optimal sky coverage with the least distortion of the outer horns. All the optical analysis was performed with the GRASP package (TICRA - Reflector Antenna and EM Modelling Software)1 http://https://www.ticra.com/software/grasp/ . The beam patterns shown in figure 5 correspond to the best solutions for the horn arrangement in the focal plane. The corresponding beam response as a function of declination for both arrangements are shown in figure 6.

Beam pattern response for the Stokes parameters as a function of celestial coordinates, for the focal plane arrangement of a rectangular horn arrangement configuration (left) and for a hexagonal horn arrangement configuration (right). The colour scale on the right refers to intensity (dB) (Abdalla et al. 2021).

Combined beam response for rectangular arrangement (columns 2 and 3, left to right) and hexagonal arrangement (columns 4 and 5, left to right) shown in figure 5 at 1100 MHz (Abdalla et al. 2021ABDALLA FB, BULL P, CAMERA S, BENOIT-LÉVY A, JOACHIMI B, KIRK D, KLOECKNER HR, MAARTENS R, RACCANELLI A & SANTOS MG. 2015. Cosmology from HI galaxy surveys with the SKA. In: Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array (AASKA14), p. 17.).

The guiding principle in the design of BINGO is simplicity. All components should be as simple as possible to minimize costs. Moreover, since there will be no moving parts, design, operation and instrument modelling will also be simpler than doing the same tasks for a conventional telescope. Another key advantage of a simple design is that it is being built in a relatively small amount of time, allowing for results within a competitive science time window.

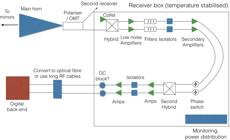

Receiver

Each receiver chain contains a correlation system, as shown in fig. 7, operating with room temperature amplifiers. The receiver is expected to operate at temperature \(T_{sys} \thicksim 70\) K in the frequency interval \(980 - 1260\) MHz, at ambient temperature. A number of tests were performed at INPE’s Division of Astrophysics, using two different low noise amplifiers (LNA). We tested a radiometer chain, with one LNA, one first stage filter and second stage LNAs. The testing was conducted in the laboratory, with no specific shielding in the amplifier structure. The measured receiver noise temperature was \(T_R = (58 \pm 6)\) K, taken as an upper limit, since the environment in which the measurements were made is permeated by RFI. Table II shows the temperature for each component of the BINGO radio telescope. Thus, the system temperature is given by \(T_{\rm sys} = T_A + T_R = 89\) K. To estimate the sensitivity of the BINGO using this simple radiometer, two ratios are used, one for the minimum temperature variation that can be detected by the radiometer and another for the flow density that such temperature represents:

Block diagram of the main components of the BINGO correlation receiver. The correlation is achieved by means of the hybrids (in our case, “magic tees“) , which in our case will be waveguide magic tees.

In eq. (1), B is the frequency operating bandwidth, \(\tau\) the integration time, \(k\) is the Boltzmann constant and \(A_{\rm eff}\) the effective area of the radio telescope. In this work, the bandwidth is \(2.8 \times 10^8\) Hz and the integration time is 1 s. The effective area used considers that 50 % of the total area of the primary mirror receives electromagnetic waves. For BINGO, this area is \(785.40~ {\rm m}^2\). The minimum temperature obtained in this case is \(\Delta T_ {\rm min} = 11\) mK and the corresponding flux, from eq. (2) is \(S (\Delta T_{min}) = 0.037\) Jy. After one year of observations, BINGO should achieve a \(40'\) pixel noise of \(36.9~\mu\)K in a 7.5 MHz frequency channel, with the parameters described in Table I. A more detailed discussion of the receiver tests can be found in the M.Sc. dissertation of Vieira 2020VAN BEMMEL IM, VAN ARDENNE A, GERALT BIJ DE VAATE J, FAULKNER AJ & MORGANTI R. 2012. Mid-frequency aperture arrays: the future of radio astronomy. PoS RTS2012: 037. doi:10.22323/1.163.0037..

Feedhorns and polariser

BINGO will use specially designed conical corrugated horns to illuminate the secondary mirror of the telescope. These need to be corrugated in order to provide the required low sidelobes coupled with very good polarisation performance. Because of the large focal ratio needed to provide the required wide field of view, the horns have \(\thicksim 1.9\)m diameter and \(\thicksim 4.9\)m length. The electromagnetic design of such horns is well understood and the first prototype was successfuly developed and tested in the Laboratory of Integration and Tests at INPE. Insertion and return loss, as well as the beam profile, were measured for the frequency interval \(900 - 1300\) MHz, in \(25\) MHz steps, for vertical and horizontal polarisations. A summary of the main properties of the horn prototype is found in Tables III and IV and the main results of the construction and testing of the feed horns and polariser are discussed in Wuensche et al. (Wuensche et al. 2020WUENSCHE CA ET AL. 2020. Baryon acoustic oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: Broadband corrugated horn construction and testing. Experimental Astronomy 50(1): 125-144. doi:10.1007/s10686-020-09666-9.).

Feedhorn beam measurements. Left: horizontal polarisation. Right: vertical polarisation. Minimum rejection was not measured at all frequencies.

Mission simulations

The assessment of the instrument performance and the reliability with which the cosmological signal can be extracted from the observed data is done through a Pipeline developed inside the collaboration and used in previous works (e.g., Bigot-Sazy et al. 2015BIGOT-SAZY MA, DICKINSON C, BATTYE RA, BROWNE IWA, MA YZ, MAFFEI B, NOVIELLO F, REMAZEILLES M & WILKINSON PN. 2015. Simulations for single-dish intensity mapping experiments. Mon Not R Astron Soc 454(3): 3240-3253. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2153., Harper & Dickinson 2018HARPER SE & DICKINSON C. 2018. Potential impact of global navigation satellite services on total power H I intensity mapping surveys. Mon Not R Astron Soc 479(2): 2024-2036. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty1495.). We briefly describe the data processing and component separation algorithm used to obtain the BINGO maps we use for our analysis. Details of the algorithm and data processing can be found in the works of Liccardo et al. 2021LICCARDO V, WUENSCHE C, MERICIA E ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: instrument performance assessment. Astron Astrophys. and Fornazier et al. 2021FORNAZIER K ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: component separation and bispectrum analysis. Astron Astrophys..

The Pipeline takes input maps of different emission mechanisms, produced by theoretical models or by observations, as well as various instrument characteristics (such as such as the number of horns and their positioning in the focal plane, receiver system temperature, focal length, etc.) and contamination from the environment. Pipeline outputs are time series which can be turned into maps that simulate the signal as measured by the instrument during a defined mission duration.

To detect BAOs in the Hi signal we will need to remove the contributions from much brighter emissions coming from our Galaxy and extragalactic sources, the most relevant emissions at \(\sim 1~{\rm GHz}\) being a combination of extragalactic point sources and diffuse Galactic synchrotron emission. These two foregrounds combined contribute \(\sim 1\) K rms at 1 GHz, while the 21cm signal fluctuations are \(\sim\) 100 \(\mu\)K rms. Some very efficient methods of component separation are being tested for BINGO, so that we can recover the cosmological Hi component.

The Pipeline operation makes use of a mission simulator, which processes all the input information described above, producing a time series (TOD), used to produce the maps at each frequency determined by the band and the number of channels. Currently, the set of maps produced is processed by a component separation algorithm to recover the cosmological Hi signal. Future plans are that this procedure should be integrated in the Pipeline body.

We are currently investigating the instrument performance using a number of different optical arrangements produced by the collaboration Abdalla et al. 2021ABDALLA FB, BULL P, CAMERA S, BENOIT-LÉVY A, JOACHIMI B, KIRK D, KLOECKNER HR, MAARTENS R, RACCANELLI A & SANTOS MG. 2015. Cosmology from HI galaxy surveys with the SKA. In: Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array (AASKA14), p. 17. and testing component separation methods, such as GNILC, developed for the Planck mission, following the work from Remazeilles et al. 2011REMAZEILLES M, DELABROUILLE J & CARDOSO JF. 2011. CMB and SZ effect separation with constrained Internal Linear Combinations. Mon Not R Astron Soc 410: 2481-2487. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17624.x. and Olivari et al. 2016OLIVARI LC, REMAZEILLES M & DICKINSON C. 2016. Extracting H I cosmological signal with generalized needlet internal linear combination. Mon Not R Astron Soc 456: 2749-2765. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2884..

A detailed description of the instrument performance and capabilities, as well as some discussion regarding the separation of components can be found in the work of Liccardo et al. 2021LICCARDO V, WUENSCHE C, MERICIA E ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: instrument performance assessment. Astron Astrophys.. A deeper analysis of the component separation process, especially regarding GNILC, and the construction of a non-gaussianity estimator module is presented in the work of Fornazier et al. 2021FORNAZIER K ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: component separation and bispectrum analysis. Astron Astrophys..

Current status

BINGO is currently funded, with about 70% of the funding already secured, mostly coming from Brazilian funding agencies (FAPESP, FINEP, MCTIC and CNPq) and a smaller amount coming from China, through purchase of components and electronic items for the instrument.

There was a major project review in July 2019, with a committee of five scientists, including two radio astronomers and and one Hi IM specialist. The result of this review was very positive, with fourteen recommendations in total. Out of these fourteen, four of them requires the close attention of the collaboration working groups and started being addressed immediately after the conclusion of the review. Namely, these four recommendations are: 1) the definition of the final receiver configuration to be used; 2) the final optical design; 3) the recommendation of adopting a full polarisation analysis (or a good motivation to avoid it); and 4) the preparation of an “end-to-end“ pipeline to simulate the mission behaviour well in advance of the beginning of operations. We have solved items 1) and 3) and item 2) is being completed. We are presently working intensely in item 4).

Final remarks

BINGO is a radio telescope designed to claim the first BAO detection, in the redshift interval \(0.13 \leq z \leq 0.45\), at radio wavelengths around \(1~{\rm GHz}\) and is currently being constructed in Paraı́ba, Northeastern Brazil, counting on the local support and expertise of Campina Grande Federal University. The measured signal is produced by the redshifted 21cm HI line, detected through an IM survey covering \(\sim~1/8\) of the sky and will probe the same redshift interval as the most important optical BAO surveys, but with different systematics. BINGO will also provide Galactic foreground maps in the frequency range 980 - 1260 MHz, with its sky coverage overlapping with a number of radio surveys. It will likely be the only radio instrument operating in its redshift range for a few years.

BINGO will provide high quality data, covering a wide range of scientific areas from cosmology to Galactic science. In view of its observation strategy and with some adjustment in the digital backend, BINGO will also be capable to detect transient phenomena, such as pulsars and FRB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.A.W. acknowledges the CNPq grant 313597/2014-6 and FAPESP Thematic project grant 2014/07885-0. E.A. acknowledges FAPESP by the grant 2014/07885-0 and FAPESP and CNPq for various other grants. R.G.L. acknowledges CAPES (process 88881.162206/2017-01) and Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for the financial support. M.P. acknowledges funding from a FAPESP Young Investigator fellowship, grant 2015/19936-1. F.A.B acknowledges a CNPq/PRONEX/FAPESQ-PB (Grant no. 165/2018). C.A.W. and F.B.A. acknowledge the UKRI-FAPESP Visiting Professor Grant 2019/05687-0. The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest regarding the contents of this paper.

REFERENCES

- ABDALLA F, MARINS A, MOTA P, FORNAZIER K ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: optical design. Astron Astrophys.

- ABDALLA FB, BLAKE C & RAWLINGS S. 2010. Forecasts for Dark Energy Measurements with Future HI Surveys. Mon Not R Astron Soc 401: 743. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15704.x.

- ABDALLA FB, BULL P, CAMERA S, BENOIT-LÉVY A, JOACHIMI B, KIRK D, KLOECKNER HR, MAARTENS R, RACCANELLI A & SANTOS MG. 2015. Cosmology from HI galaxy surveys with the SKA. In: Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array (AASKA14), p. 17.

- AGHAMOUSA A ET AL. 2016a. The DESI Experiment Part I: Science,Targeting, and Survey Design. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1611.00036.

- AGHAMOUSA A ET AL. 2016b. The DESI Experiment Part II: Instrument Design. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1611.00037.

- ALBRECHT A ET AL. 2006. Report of the Dark Energy Task Force. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 0609591.

- ANDERSON L ET AL. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Releases 10 and 11 Galaxy samples. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441(1): 24-62. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu523.

- BAKER T, FERREIRA PG, SKORDIS C & ZUNTZ J. 2011. Towards a fully consistent parameterization of modified gravity. Phys Rev D 84: 124018. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.84.124018.

- BATTYE R ET AL. 2016. Update on the BINGO 21cm intensity mapping experiment. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1610.06826.

- BATTYE RA, BROWN ML, BROWNE IWA, DAVIS RJ, DEWDNEY P, DICKINSON C, HERON G, MAFFEI B, POURTSIDOU A & WILKINSON PN. 2012. BINGO: a single dish approach to 21cm intensity mapping. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1209.1041.

- BATTYE RA, BROWNE IWA, DICKINSON C, HERON G, MAFFEI B & POURTSIDOU A. 2013. H I intensity mapping: a single dish approach. Mon Not R Astron Soc 434: 1239-1256. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1082.

- BENNETT CL ET AL. 2013. Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results. Astrophys J Supp 208: 20. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20.

- BEUTLER F, BLAKE C, COLLESS M, JONES DH, STAVELEY-SMITH L, CAMPBELL L, PARKER Q, SAUNDERS W & WATSON F. 2011. The 6dF Galaxy Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations and the local Hubble constant. Mon Not R Astron Soc 416(4): 3017-3032. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19250.x.

- BIGOT-SAZY MA, DICKINSON C, BATTYE RA, BROWNE IWA, MA YZ, MAFFEI B, NOVIELLO F, REMAZEILLES M & WILKINSON PN. 2015. Simulations for single-dish intensity mapping experiments. Mon Not R Astron Soc 454(3): 3240-3253. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2153.

- BULL P, FERREIRA PG, PATEL P & SANTOS MG. 2015. Late-time Cosmology with 21 cm Intensity Mapping Experiments. Astrophys J 803(1): 21. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/803/1/21.

- CHANG TC, PEN UL, PETERSON JB & MCDONALD P. 2008. Baryon Acoustic Oscillation Intensity Mapping as a Test of Dark Energy. Phys Rev Lett 100: 091303. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.091303.

- CHANG TC, PEN UL, BANDURA K & PETERSON JB. 2010. An intensity map of hydrogen 21-cm emission at redshift z \(\sim\) 0.8. Nature 466: 463-465. doi:10.1038/nature09187.

- CORDES JM & CHATTERJEE S. 2019. Fast radio bursts: an extragalactic enigma. Ann Rev Astron Astrophys 57: 417-465.

- COSTA A ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: cosmological forecasts. Astron Astrophys.

- EISENSTEIN DJ ET AL. 2005. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. Astrophys J 633: 560-574. doi:10.1086/466512.

- FENG C, WANG B, ABDALLA E & SU R. 2008. Observational constraints on the dark energy and dark matter mutual coupling. Phys Lett B 665(2-3): 111-119. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.05.066.

- FERREIRA EGM, QUINTIN J, COSTA AA, ABDALLA E & WANG B. 2017. Evidence for interacting dark energy from BOSS. Phys Rev D 95(4): 043520. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.95.043520.

- FORNAZIER K ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: component separation and bispectrum analysis. Astron Astrophys.

- GREEN J ET AL. 2011. Wide-Field InfraRed Survey Telescope (WFIRST) Interim Report. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1108.1374.

- HARPER SE & DICKINSON C. 2018. Potential impact of global navigation satellite services on total power H I intensity mapping surveys. Mon Not R Astron Soc 479(2): 2024-2036. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty1495.

- HE JH, WANG B & ABDALLA E. 2009. Stability of the curvature perturbation in dark sectors’ mutual interacting models. Phys Lett B 671(1): 139-145. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.11.062.

- HE JH, WANG B & ABDALLA E. 2011. Testing the interaction between dark energy and dark matter via the latest observations. Phys Rev D 83: 063515. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.83.063515. URL https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.83.063515.

- KAZIN EA ET AL. 2014. The WiggleZ Dark Energy Survey: improved distance measurements to z = 1 with reconstruction of the baryonic acoustic feature. Mon Not R Astron Soc 441: 3524-3542. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu778.

- KOVETZ ED ET AL. 2017. Line-Intensity Mapping: 2017 Status Report. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1709.09066.

- LEVI ME, KIM AG, LAMPTON ML & SHOLL MJ. 2011. Science Yield of an Improved Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST). arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1105.0959.

- LICCARDO V, WUENSCHE C, MERICIA E ET AL. IN PRESS. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: instrument performance assessment. Astron Astrophys.

- LIU A & TEGMARK M. 2011. A Method for 21 cm Power Spectrum Estimation in the Presence of Foregrounds. Phys Rev D 83: 103006.

- LOEB A & WYITHE JSB. 2008. Possibility of Precise Measurement of the Cosmological Power Spectrum with a Dedicated Survey of 21 cm Emission after Reionization. Phys Rev Lett 100: 161301.

- LORIMER DR, BAILES M, MCLAUGHLIN MA, NARKEVIC DJ & CRAWFORD F. 2007. A Bright Millisecond Radio Burst of Extragalactic Origin. Science 318: 777. doi:10.1126/science.1147532.

- MAARTENS R, ABDALLA FB, JARVIS M & SANTOS MG. 2015. Overview of cosmology with the SKA. Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array (AASKA14) 16.

- MASUI KW ET AL. 2013. Measurement of 21 cm Brightness Fluctuations at z \(\sim 0.8\) in Cross-correlation. Astrophys J Lett 763: L20. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/763/1/L20.

- MICHELETTI S, ABDALLA E & WANG B. 2009. A Field Theory Model for Dark Matter and Dark Energy in Interaction. Phys Rev D D79: 123506. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.79.123506.

- NEWBURGH LB, ADDISON GE, AMIRI M, BANDURA K, BOND JR, CONNOR L, CLICHE JF, DAVIS G, DENG M & DENMAN N. 2014. Calibrating CHIME: a new radio interferometer to probe dark energy. In: Ground-based and Airborne Telescopes V. Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Conference Series.

- OLIVARI LC, REMAZEILLES M & DICKINSON C. 2016. Extracting H I cosmological signal with generalized needlet internal linear combination. Mon Not R Astron Soc 456: 2749-2765. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2884.

- OLIVARI LC, DICKINSON C, BATTYE RA, MA YZ, COSTA AA, REMAZEILLES M & HARPER S. 2018. Cosmological parameter forecasts for H I intensity mapping experiments using the angular power spectrum. Mon Not R Astron Soc 473: 4242-4256. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx2621.

- PADMANABHAN H, CHOUDHURY TR & REFREGIER A. 2015. Theoretical and observational constraints on the H I intensity power spectrum. Mon Not R Astron Soc 447(4): 3745-3755. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2702.

- PEEL MW ET AL. 2019. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: Radio Frequency Interference Measurements and Telescope Site Selection. Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation 8(1): 1940005. doi:10.1142/S2251171719400051.

- PERCIVAL WJ ET AL. 2010. Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 7 galaxy sample. Mon Not R Astron Soc 401(4): 2148-2168. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15812.x.

- PERLMUTTER S, ALDERING G, DELLA VALLE M, DEUSTUA S, ELLIS RS, FABBRO S, FRUCHTER A, GOLDHABER G, GROOM DE & HOOK IM. 1998. Discovery of a supernova explosion at half the age of the Universe. Nature 391(6662): 51-54. doi:10.1038/34124.

- PETERSON JB, BANDURA K & PEN UL. 2006. The Hubble Sphere Hydrogen Survey. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 0606104.

- PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2014. Planck 2013 results. XVI. Cosmological parameters. Astron Astrophys 571: A16. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321591.

- PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2016. Planck 2015 results. I. Overview of products and scientific results. Astron Astrophys 594: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527101.

- PLANCK COLLABORATION ET AL. 2018. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1807.06209: arXiv:1807.06209.

- POBER JC, PARSONS AR, DEBOER DR, MCDONALD P, MCQUINN M, AGUIRRE JE, ALI Z, BRADLEY RF, CHANG TC & MORALES MF. 2013. The Baryon Acoustic Oscillation Broadband and Broad-beam Array: Design Overview and Sensitivity Forecasts. Astron J 145: 65. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/145/3/65.

- REFREGIER A, AMARA A, KITCHING TD, RASSAT A, SCARAMELLA R & WELLER J. 2010. Euclid Imaging Consortium Science Book. arXiv reprint:astro-ph 1001.0061.

- REID B ET AL. 2015. SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey Data Release 12: galaxy target selection and large-scale structure catalogues. Mon Not R Astron Soc 455(2): 1553-1573.

- REMAZEILLES M, DELABROUILLE J & CARDOSO JF. 2011. CMB and SZ effect separation with constrained Internal Linear Combinations. Mon Not R Astron Soc 410: 2481-2487. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17624.x.

- RIESS AG, FILIPPENKO AV, CHALLIS P, CLOCCHIATTI A, DIERCKS A, GARNAVICH PM, GILLILAND RL, HOGAN CJ, JHA S & KIRSHNER RP. 1998. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. Astron J 116(3): 1009-1038. doi:10.1086/300499.

- SQUARE KILOMETRE ARRAY COSMOLOGY SCIENCE WORKING GROUP ET AL. 2020. Cosmology with Phase 1 of the Square Kilometre Array Red Book 2018: Technical specifications and performance forecasts. Publ of the Astr Soc Asia 37: e007. doi:10.1017/pasa.2019.51.

- SWITZER ER ET AL. 2013. Determination of z \(\sim 0.8\) neutral hydrogen fluctuations using the 21 cm intensity mapping autocorrelation. Mon Not R Astron Soc 434: L46-L50. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt074.

- TOJEIRO R, ROSS AJ, BURDEN A, SAMUSHIA L, MANERA M, PERCIVAL WJ, BEUTLER F, BRINKMANN J, BROWNSTEIN JR & CUESTA AJ. 2014. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: galaxy clustering measurements in the low-redshift sample of Data Release 11. Mon Not R Astron Soc 440(3): 2222-2237. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu371.

- TYSON T, WITTMAN D, HENNAWI J & SPERGEL D. 2002. LSST as a precision probe of dark energy. In: APS April Meeting Abstracts. APS Meeting Abstracts. p. Y6.004.

- VAN BEMMEL IM, VAN ARDENNE A, GERALT BIJ DE VAATE J, FAULKNER AJ & MORGANTI R. 2012. Mid-frequency aperture arrays: the future of radio astronomy. PoS RTS2012: 037. doi:10.22323/1.163.0037.

- VIEIRA FAS. 2020. Protótipo de radiômetro simples para pesquisa em Fast Radio Bursts com o radiotelescópio BINGO. Master’s thesis. INPE. (Unpublished).

- WANG B, GONG Y & ABDALLA E. 2005. Transition of the dark energy equation of state in an interacting holographic dark energy model. Phys Lett B 624(3-4): 141-146. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.08.008.

- WANG B, ZANG J, LIN CY, ABDALLA E & MICHELETTI S. 2007. Interacting dark energy and dark matter: Observational constraints from cosmological parameters. Nucl Phys B 778(1-2): 69-84. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.04.037.

- WEINBERG DH, MORTONSON MJ, EISENSTEIN DJ, HIRATA C, RIESS AG & ROZO E. 2013. Observational probes of cosmic acceleration. Phys Rep 530: 87-255. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2013.05.001.

- WUENSCHE CA & THE BINGO COLLABORATION. 2019. The BINGO telescope: a new instrument exploring the new 21 cm cosmology window. In: Journal of Physics Conference Series. Journal of Physics Conference Series, vol. 1269, p. 012002. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1269/1/012002.

- WUENSCHE CA ET AL. 2020. Baryon acoustic oscillations from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations: Broadband corrugated horn construction and testing. Experimental Astronomy 50(1): 125-144. doi:10.1007/s10686-020-09666-9.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

26 May 2021 -

Date of issue

2021

History

-

Received

14 July 2020 -

Accepted

10 Aug 2020