Abstract

Although the Last Planner System (LPS) has often been studied as a method for production planning and control, specific characteristics of the construction sector require planning and control processes to assume broader, more systemic roles that normally fall under the concept of production strategy. Based on this understanding, this paper draws on an appropriate theoretical framework to examine the full range of LPS roles within both production strategy and production management. We argue for enhancing Medium-Term Planning (MTP) through practices that support the LPS at these two levels. Using Design Science Research procedures, the study identifies the main barriers that prevent the Medium-Term Planning process from fully supporting LPS roles. The literature review and empirical evidence allowed the development of a new MTP process model, designed not only to integrate planning levels but to align actions across company sectors. In doing so, the model helps establish the LPS as a genuine source of competitive advantage, which enables the production function to lead other functional areas.

Keywords

Medium-term planning; Last Planner System; Production strategy; Production management

Resumo

Embora o Last Planner System (LPS) seja pesquisado como um método de planejamento e controle da produção, existem peculiaridades da construção civil que levam o planejamento e controle a assumir atribuições mais sistêmicas, típicas da estratégia de produção. Partindo dessa percepção, esse artigo fundamenta-se numa teoria apropriada para discernir as atribuições amplas do LPS, tanto na estratégia como na gestão da produção. Argumentos são apresentados para a melhoria do Planejamento de Médio Prazo (PMP) por meio de práticas que promovam os atributos do LPS nestas duas frentes. Utilizando Design Science Research, a pesquisa identificou as principais barreiras que impedem o PMP de apoiar as atribuições amplas do LPS. A literatura consultada e os dados empíricos levantados possibilitaram a proposição de um modelo de processo para o PMP, que inova por buscar uma melhor integração dos níveis de planejamento bem como das ações dos diferentes setores da empresa. Com isso, contribui-se para tornar o LPS numa vantagem competitiva, que credencia a produção a liderar as demais áreas funcionais.

Palavras-chave

Planejamento de Médio Prazo; Sistema Last Planner; Estratégia de Produção; Gestão da Produção

Introduction

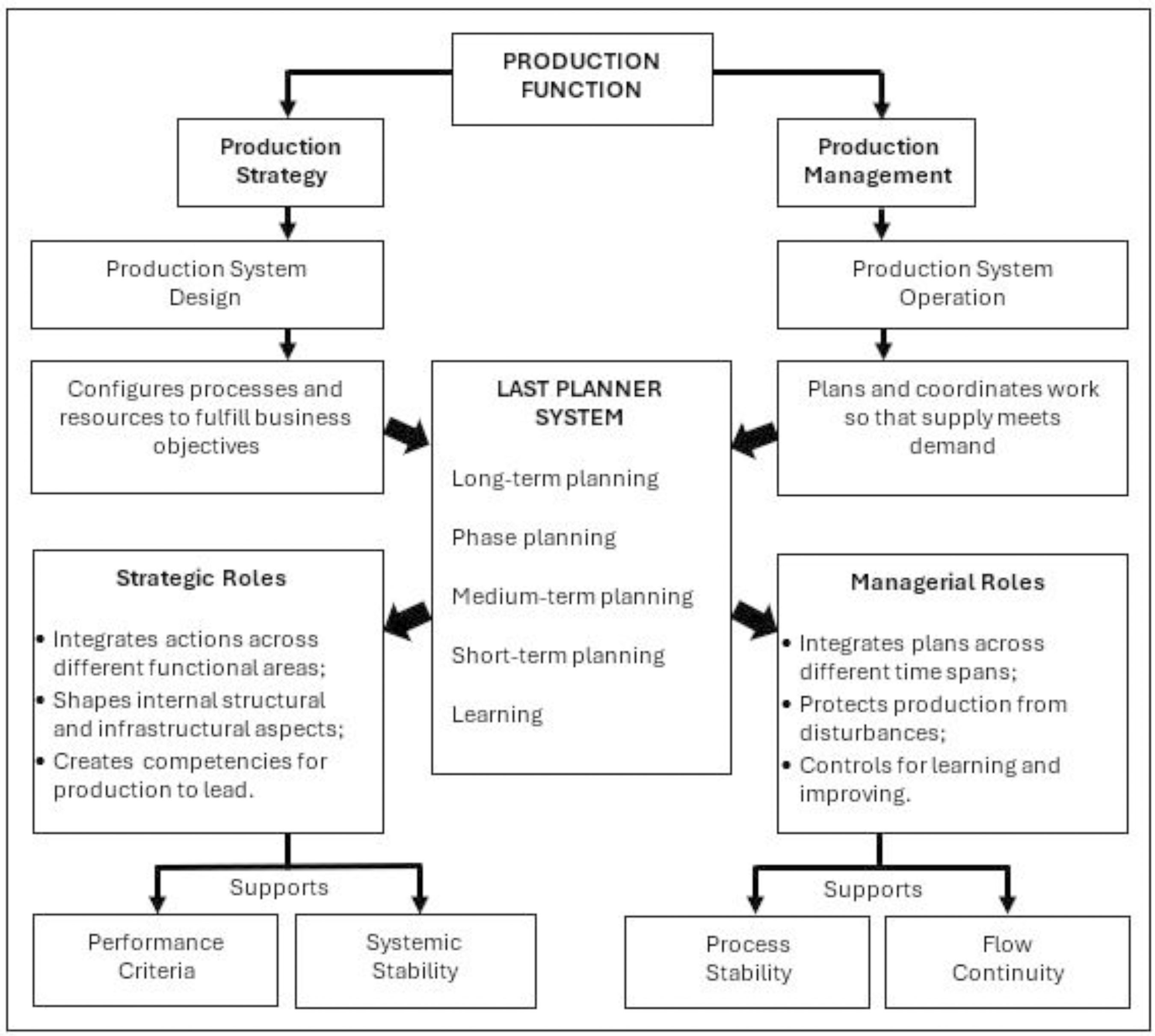

Unlike research in the field of production and operations management, studies in construction management rarely distinguish the concepts of production management and production strategy. Evidence from other sectors, however, suggests that properly acknowledging these concepts is essential for achieving high-performing production systems. Production strategies align production system configurations with business objectives, whereas production management ensures their effective operation to match supply with demand (Wheelwright, 1984; Girke et al., 2025). The former is concerned with systemic and long-term initiatives, while the latter focuses on detailed, short-term actions (Acur et al., 2003; Corrêa; Corrêa, 2017).

Coherence between these two managerial levels is vital. The systemic stability provided by production strategy must be complemented by the process stability achieved through production management. Production strategy emphasizes the overall business process, structuring the production function in alignment with decisions in other functional areas (quality, safety, finance, etc.) to meet competitive criteria (Hill, 1993). It involves sporadic decisions that shape the structural and infrastructural aspects of the production system (Barros Neto, 2002). Production management, in turn, emphasizes planning and control processes that organize production orders and volumes. It encompasses routine actions for the provision of supplies, workflow balance, and quality assurance (Shavarini et al., 2013).

In construction, the lack of clear boundaries between these concepts stems from sector-specific characteristics, which include temporary organizations that deliver unique products built on construction sites (Koskela, 2000). This often requires production planning and control (PP&C) to extend beyond its conventional scope, encompassing production system redesign throughout a project’s life cycle (Schramm; Rodrigues; Formoso, 2006). Decisions that in other industries belong to production strategy – production layout, collective safety, subcontracting, supplier management – are often part of the scope of PP&C, which becomes essential both to avoid disturbances in processes and to provide overall conditions needed to meet deadlines and budget (Hitt; Ireland; Hoskisson, 2003; Miranda Filho; Heineck; Costa, 2011).

In fact, over the years, the scope of PP&C in construction has expanded to include primary and support functions as well as their outputs. In this context, the Last Planner System (LPS) stands out as a collaborative method for planning and control that protects production flows by integrating long-term, medium-term, and short-term planning (Ballard, 2000; Ballard; Tommelein, 2016). Among these, Medium-Term Planning (MTP) is central to LPS success, acting as a shield against disturbances and uncertainty by identifying and removing constraints for each task (Ballard, 1997; Tommelein; Ballard, 1997; Lagos et al., 2023). The removal of constraints improves plan reliability and is one of LPS’s key roles in the production function (Figure 1).

Rooted in lean production principles originally developed for manufacturing, the LPS has delivered gains in coordination, predictability, productivity, and organizational learning for construction companies (Kemmer et al., 2016; Lappalainen et al., 2022). Field studies show that, even when partially implemented, the LPS can strengthen internal relationships and enhance production management, yielding positive outcomes (Priven; Sacks, 2015). As a result, this system has been used worldwide, being recognized as the most widely adopted lean construction method (Gao; Low, 2014). Still, previous studies have pointed out that results can be improved if less fragmented procedures are adopted (Hamzeh; Ballard; Tommelein, 2008; Fernandez-Solis et al., 2013). Practices related to MTP and learning for continuous improvement are often the ones missing (Hamzeh et al., 2015; Khanh; Kim, 2016). Therefore, many researchers call for in-depth studies on MTP implementation challenges in order to fill gaps in knowledge (Mohan; Iyer, 2005; Bortolazza; Formoso, 2006; Kemmer et al., 2007; Hamzeh; Ballard; Tommelein, 2012; Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2013; Salvatierra et al., 2015; Toledo; Olivares; Gónzalez, 2016).

Nevertheless, some studies indicate that solutions to implementation challenges may lie at the organizational level. Although widespread adoption of LPS practices correlates with positive production management outcomes, its success depends on more than fine-tuning on-site processes (Maylor et al., 2015). Achieving higher performance requires supportive, organization-related characteristics that remain underexplored (Castillo et al., 2018). This is why some suggestions, such as disseminating the LPS among subcontractors and frontline workers, seem simplistic and limited to the commonly adopted production management perspective (Daniel; Pasquire; Brenda et al., 2019). They overlook strategic, organizational-level LPS roles that could be developed not only to better configure the production function but also to lead and integrate efforts of other functional areas.

Recognizing the broadened role of PP&C in construction, this study argues that fully exploring the LPS as a competitive advantage requires clarifying and strengthening its different roles based on an appropriate conceptual framework. This research study aims to propose a process model for MTP that supports the LPS both by integrating planning levels and by aligning actions across different functional areas. As secondary objectives, we seek to understand three aspects related to MTP: barriers to implementation, practices to overcome them, and LPS roles promoted. By framing the LPS from an organizational perspective, this research innovates by introducing an MTP model that highlights LPS contributions to both production management and production strategy.

Understanding LPS roles

LPS Components

The goal of the LPS is to convert what should be done into what can be done, breaking away from traditional planning models that concentrate decisions in a single planning level (Tommelein; Ballard, 1997; Hamzeh, 2009, 2011). It involves representatives from different teams working collaboratively to improve the reliability of plans and promote stability (Ballard, 2000). The LPS is often described as a system because it encompasses procedures that support both core and supporting processes (Ballard; Tommelein, 2021). It structures a hierarchy of plans and controls, each with different time horizons, to address various types of uncertainty (Ballard; Tommelein, 2016). Its main components are:

-

Long-Term Planning: establishes the Master Plan, defining project milestones and major phases. It is done at an early stage, when information on activity duration or input supply is still inaccurate (Ballard, 2000). Tools such as the Location-Based Management System (LBMS) can support this level of planning. This spatial approach organizes activities based on their physical location at the construction site, enabling visualization of progress across work fronts and helping identify conflicts, overlaps, or gaps (Seppänen; Modrich; Ballard, 2015);

-

Phase Planning: bridges long-term and medium-term planning. It details project phases according to master plan milestones, defines logical activity sequences, and sets readiness criteria for execution. This stage promotes early collaboration, anticipates interferences, and reduces downstream uncertainty. Despite its importance to the LPS, phase planning remains less common in practice than medium- or short-term planning because of operational difficulties (Ribeiro; Costa; Magalhães, 2017). Its effectiveness depends on engaging different functional areas, securing senior management support, and systematizing the planning process (Ribeiro; Costa; Magalhães, 2017; Ballard; Tommelein, 2021);

-

Medium-Term Planning: creates the conditions needed for reliable execution, identifying and removing constraints that may hinder production progress (Bellaver et al., 2022). It also ensures stakeholder commitment to plans (Javanmardi et al., 2018). While phase planning structures project phases, the MTP seeks the operational feasibility of each phase by making tasks viable and reliable (Ballard; Tommelein, 2021). The goal is to avoid Making-Do, which means reducing improvisations that can lead to workflow instability, rework, low productivity, and workplace hazards (Koskela, 2004; Formoso et al., 2017). Monitoring such problems helps assess MTP performance, adjust plans, and prevent recurrent failures (Hamzeh et al., 2012);

-

Short-Term Planning: prepares the weekly production schedule, authorizing only work packages that meet all requirements (Ballard, 2000). Short-term plans only include activities that have the required inputs, specifications, and other prerequisites for a sound execution; and

-

Learning: compares execution with plans, recording problems that caused the non-completion of activities. Data provided is useful to improve both planning procedures and production system features. Weekly meetings are held to examine root causes, define corrective actions, and verify their effectiveness (Ballard; Tommelein, 2016).

LPS broader roles

Uncertainties in construction stem from factors also found in other sectors, such as project complexity, long lead times, climate influence, and high reliance on labor (Nakagawa; Shimizu, 2004; Fischer, 2009; Murguia et al., 2022). However, these are usually intensified by the uniqueness of each product and by the nature of on-site production. Hence, construction requires multiple specialists in different phases, generating temporary organizations and production systems that undergo frequent changes throughout the project life cycle (Koskela, 2003).

The dynamic behavior of production systems is perhaps the most visible embodiment of construction peculiarities. As construction progresses, the site layout undergoes some major changes as well as smaller alterations on a daily basis. Workstations shift and material flows adapt as mobile teams enter and leave locations according to planned activities. Thus, product flows often diverge from the expected movement of materials, equipment, and labor, adding greater uncertainties to planning (Choo; Tommelein, 1999). In situations like these, performing simulations or producing reliable plans becomes difficult because the work configuration is constantly changing (Alves; Tommelein; Ballard, 2006).

In this environment, aspects related to production management, such as delivery schedules and workload, need to be regularly revised by the production function to adjust and limit the number of activities in the system according to interdependencies and spatial constraints. Similarly, aspects covered by the production strategy, such as resource capacity, collective safety, and physical flows, need to be often reviewed in coordination with other functional areas to meet the goals in each phase. This context highlights the broad roles of PP&C in construction, which need to be clearly understood for the improvement of the LPS. It also highlights the importance of developing Medium-Term Planning accordingly, as many systemic conditions for plan reliability take shape at this level.

Roles in production management

The main goal of Medium-Term Planning (MTP) is to maintain an uninterrupted, stable flow of construction activities so targets can be met (Ballard; Howell, 2003). Based on the analysis of work packages defined for each project phase, MTP seeks to ensure, in preceding weeks, that all conditions are in place for the reliable execution of work packages to be carried out in the short term (Bellaver et al., 2022). This is achieved through collaborative planning conducted to provide resources, assign responsibilities, monitor material deliveries, and track the progress of predecessor tasks (Ballard, 1997; Ballard; Tommelein, 2016).

Most literature treats MTP implementation as supporting three LPS roles:

-

integrating planning levels;

-

shielding production from disturbances and uncertainties; and

-

controlling performance for learning and improvement (Ballard, 2000; Ballard; Howell, 1998; Hamzeh, 2009).

Regarded as the basic roles of the LPS, all three fall within the domain of production management because they focus on resource supply readiness, workload leveling, and output quality. Studies frequently focus on identifying and mitigating barriers to these roles. Among them, production shielding stands out as the one receiving the most attention in case studies due to the perception of recurrent failures in constraint analysis and removal (Britt et al., 2014 Salvatierra et al., 2015; Khanh; Kim, 2016; Toledo; Olivares; Gónzalez, 2016).

Roles in production strategy

In addition to the aforementioned LPS basic roles, Coelho (2003) pointed out secondary roles often overlooked in MTP studies, which include the management of physical flows, costs, and safety. For instance, flow management is typically limited to LBMS use in long-term planning or ad hoc redesigns of site layouts during phase planning (Kenley, 2004). Such decisions, which have lasting impacts on spatial organization, should be coordinated within MTP and supported by other areas like safety and procurement. In practice, however, they are often improvised and lack collaboration among stakeholders (Olivieri; Granja; Pichi, 2016). Similar gaps occur in cost control, people management, waste disposal, and other aspects that require aligned actions between the production function and different company areas. Interactions between them are often limited to information exchange in planning meetings, without any support or integration of management systems (Bellaver et al., 2022).

Due to long-term impacts, some of these secondary roles extend beyond the scope of production management and are clearly connected to the concept of production strategy. Though no single definition dominates the literature on production and operations management (Acur et al., 2003), production strategy is commonly defined as a pattern of consistent and longer-impact decisions aligning production objectives, processes, and resources with business goals (Kim et al., 2014). It also seeks horizontal coherence between production and other functions to ensure their vertical coherence with the business strategy (Wheelright, 1984). Developing this integrative capability grants the production function leadership over other areas, making it a source of competitive advantage (Slack et al., 2018). These strategic roles are inherent in the LPS, even if not formally embedded in its procedures or emphasized in construction management literature. Clarifying them through a different theoretical lens helps in recognizing the ample roles of the LPS and opens opportunities to enhance MTP, where they are realized.

The importance of MTP for LPS roles

This study frames the LPS through three key insights:

-

the so-called secondary roles of the LPS are in fact strategic, as they seek to integrate actions across different functional areas with initiatives in the production function;

-

the LPS should be understood as part of the process of production strategy implementation, configuring and aligning structural and infrastructural elements of production systems; and

-

the conversion of the LPS into a genuine competitive advantage depends on strengthening MTP with practices that empower the production function to lead other areas.

After all, it is through MTP that actions involving different areas of the company can be started.

The discussion herein highlights a misconception regarding the use of the terms “basic roles” and “secondary roles”. The common labels “basic” and “secondary” imply a hierarchy that obscures the equally important role of the LPS in shaping the production system. To better balance and reflect their importance, this paper recommends the terms “managerial roles in production management” and “strategic roles in production strategy” (Figure 2). This framing underpins the process model proposed here for improving MTP across different contexts.

Research method

Methodological approach

This study is framed as qualitative and exploratory research, drawing on information collected from a literature review, insights from professionals and experts, and data obtained through an empirical study (Yin, 2016). The research strategy adopted was Design Science Research (DSR), which is described as prescriptive in nature, as it connects the problem with its solution through accumulated theoretical knowledge (Kasanen; Lukka; Siitonen, 1993). Within the DSR approach, a solution concept is developed for classes of practical problems, generating knowledge that can be generalized and applied to a limited range of situations by practitioners or other researchers (Dresch; Lacerda; Antunes Junior, 2015).

Description of the research stages

This research study was divided into six stages, as illustrated in Figure 3. The procedures adopted in each stage are described below.

The first stage consisted of identifying a problem of practical and theoretical relevance and getting a better understanding of it through a systematic literature review (SLR). The comprehension of barriers to MTP was supported by the StArt (State of the Art through Systematic Review) tool, in which academic papers were inserted in a single batch for analysis. The SLR protocol was structured in the following steps:

-

choice of search terms;

-

choice of databases;

-

criteria for inclusion of papers in the SLR;

-

reading and analysis of the full text; and

-

result summary.

The search strategy used the terms “last planner system”, “lookahead planning”, “medium term planning”, “operations management”, “operations strategy”, “production system design”, often combined with the words “production” or “construction”. This search took place in the second half of 2023 and encompassed several databases, including Web of Science Scopus, ScienceDirect, and proceedings of annual conferences of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC). The inclusion of IGLC conference papers in the SLR is justified by the significant contributions of this community to the advancement of Lean Construction (LC) and the Last Planner System. As Jacobs (2010) and Daniel, Pasquire and Brenda (2019) point out, the IGLC repository currently concentrates most of the publications on LC worldwide, including those related to MTP in construction projects.

Regarding the studies on the Last Planner System and MPT, the selection and analysis of the papers were conducted by an independent reviewer. Three criteria were taken into account for their inclusion: studies that specifically addressed MTP; studies on the LPS that contained data on MTP in their results; and studies on the implementation of LC that included information about MTP. The StArt tool allowed an automatic identification of duplicate papers. The process resulted in the collection of 173 papers, of which 15 were initially eliminated due to duplication. After title and abstract screening, another 81 were excluded for not meeting the criteria. A total of 77 papers remained for full-text reading, of which 21 were excluded for not providing sufficient information on MTP, yielding 56 studies that constituted the final basis of the SLR, all of which were read and analyzed in full.

The analysis of the selected papers was divided into two main categories:

-

the identification of the main barriers faced during the implementation of MTP in construction projects; and

-

the systematization of practices, recommendations, and relevant contributions to LPS roles.

This knowledge base was essential to guide the development of the model proposed in this study.

In the second stage, an empirical study was conducted in a local construction company, selected because of its participation in an ongoing Construction Industry Innovation Program. The aim was to understand barriers in MTP implementation and the solutions adopted. The research was carried out in one of their residential projects located in the town of Fortaleza, Brazil. Situated on a land plot of 9,518 m², the project consisted of three towers, each with a basement, a ground floor, a leisure floor, and 21 floors, totaling 560 apartments in their finishing phase (77% completed at the time of the research).

Founded in 1983, the construction company operates in both commercial and residential segments, employs more than 500 staff, and has been a lean construction practitioner since 2010. Production planning and control (PP&C) is carried out internally and is based on LPS, although its procedures are not formally documented within the Quality Management System (QMS). Long-term plans are performed using the Line-of-Balance technique, with the support of CPM software. The MTP is structured over a 90-day horizon and is conducted without any support of Building Information Modeling (BIM), which is only used during the design phase for clash detection and quantity take-offs.

Data collection lasted for three months, during which the researcher carried out participant observation in MTP meetings that were 2 hours long on average. The meetings were attended by the site engineer, construction foreman, subcontractors, safety technicians, and interns. Additionally, five semi-structured interviews were conducted with the following professionals: engineering director (senior management); site production engineer (operational manager); planning assistant (responsible for updating records and conducting MTP meetings); technical supervisor of the aluminum frames subcontractor; and technical supervisor of the drywall and painting subcontractor. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and followed a protocol addressing topics such as: experience with the LPS, MTP structure and procedures, operational barriers, suggestions for process improvement, and perceptions on LPS roles. Besides interviews and participant observation, company documents were analyzed, including MTP spreadsheets, the long-term schedule, weekly short-term records, and constraint analysis reports. This methodological triangulation aimed to enhance the robustness and validity of the data collected.

In stage three, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five construction industry specialists – four from construction companies and one from a consultancy firm specialized in project planning – all with 12 to 30 years of professional experience, and varying levels of expertise in LPS implementation. This stage sought to deepen the analysis of challenges and practices related to MTP, as well as their perceived roles.

In stage four, semi-structured interviews were carried out with six researchers recognized for their academic and scientific contributions in the field of construction management. They had between 15 and 38 years of experience at the time. The selection of five of these participants was based on the identification of Brazilian academics with relevant publications on topics directly related to MTP. The sixth interviewee was included due to his internationally recognized expertise in lean production and project management. Most interviews were conducted face-to-face, except for one conducted via videoconference due to the participant residing abroad. These interviews contributed to the evaluation and refinement of the initial MTP model developed from the SLR and empirical study.

The interview scripts in stages three and four followed similar thematic blocks, covering barriers and practices related to shielding production against uncertainties, operations design, physical flow analysis, cost management, and safety planning and control. However, the stage three script included specific questions on schedule control and corrective actions in response to MTP changes. In stage four, these topics were distributed into different sets of questions. The interviewees in this stage were also asked to suggest other practices relevant to MTP, using their broad theoretical domain on the topic. These differences demonstrate the adaptation of the scripts to the practical experience of specialists and the analytical expertise of researchers, which helped to enrich the analysis and enhance the MTP model.

Stage five of the research consisted of designing and evaluating the process model for MTP, using the knowledge acquired from the SLR, empirical data, and expert/researcher interviews. The artifact emerged from the analysis of barriers to MTP implementation and was structured using an Ishikawa diagram, which grouped causes into four categories: processes, methods, people, and management. The evaluation of the artifact was guided by the constructs of utility and ease of use, since the intended users are project managers and planning consultants.

The usefulness of the model was assessed across six sub-constructs from the MTP: ability to protect production, integration of planning levels, provision of control and learning, facilitation of physical flow analysis, integration with financial planning and cost control, and incorporation of safety into planning. Ease of use was evaluated in terms of three dimensions: clarity of processes to sustain MTP routines, enhancement of cross-functional collaboration and guidance, and improved subcontractor relationships. Model evaluation was conducted through semi-structured interviews with three evaluators – one researcher and two consultants with extensive experience in construction planning – who reviewed the artifact before its final version. This approach allowed the verification of the model’s functionality, relevance to LPS roles, and practical applicability in construction project contexts.

Finally, stage six involved a reflection on lessons learned and consolidation of research results, highlighting practical and theoretical implications of the proposed model for production strategy and management. All six stages were conducted according to procedures approved by the University’s Ethics Committee (protocol nº 6.873.634).

Results

Existing barriers and proposals for improvement

The main barriers related to MTP implementation, identified through the SLR, the empirical study, and interviews, are presented in Table 1. In total, 32 barriers are listed, of which only seven had been previously reported in the literature, showing the significant contribution of empirical research in expanding knowledge on the topic. Barriers are organized into four categories – Processes, Methods, Management, and People – and divided into main and secondary causes to point out the frequency of identification according to different data sources (empirical study, experts, researchers, and SLR). For each barrier, improvement proposals gathered from multiple sources are outlined. These were incorporated into the proposed model, forming a set of best practices to overcome the observed challenges.

Figure 4 complements Table 1 by offering a visual representation of the barriers through a cause-and-effect diagram, highlighting the interrelations among the challenges affecting MTP implementation. This graphical synthesis facilitates the understanding of the complex set of factors involved and underscores the critical issues that the proposed model seeks to address. In this sense, Figure 4 works as a conceptual map of the challenges the model aims to overcome. The triangulation of data sources (literature, practice, and expert/researcher perceptions) enabled the formulation of the improvement proposals presented in the final column of Table 1.

MTP model

A generic Medium-Term Planning (MTP) model is presented in Figure 5, combining solutions proposed for the barriers identified in Table 1. The feedback from semi-structured interviews during the model evaluation allowed further improvements, which are highlighted in red in the same figure. The model is structured in four main steps:

-

input of required information, data, and documents;

-

phase planning of new activities, based on the LBMS plan;

-

execution of MTP procedures; and

-

interface with short-term planning to ensure continuous feedback and adjustment.

The model assumes that LBMS is used for long-term planning. Based on master plan milestones, phase planning can detail project phases, allowing evaluation of work packages, sequences, paces, and production locations (Seppänen; Modrich; Ballard, 2015).

In each new phase, the management team initiates lookahead planning by consulting the Quality System Manual to verify prerequisites for work packages. More than describing sequential tasks and technical aspects, the Quality Manual offers a comprehensive list of specific prerequisites for each work package, which are constantly reviewed or updated with the help of people from different company areas. The prerequisites encompass construction materials, work tools, workforce qualifications, collective and personal protective equipment, design drawings, and other specifications required to avoid “making-do”. The Manual also contains inspection criteria for desirable outputs of each work package, as well as indicators for measuring undesirable outputs like defects, waste, and pollutants.

The Quality System Manual has gained a newfound utility in the MTP model. It is intended not only to compile technical procedures to be followed but also to capture and preserve the knowledge accumulated over time across functional areas such as human resources, procurement, quality, and safety. By documenting prerequisites, it reduces reliance on the tacit experience of site managers and other key personnel. As more prerequisites are known, fewer constraints are likely to emerge or unexpectedly challenge those responsible for planning. Most importantly, the prerequisites transform the Quality System Manual into a valuable instrument for production management teams, enabling them to integrate and lead the actions of other functional areas throughout Phase Planning and Medium-Term Planning. This is fundamental to supporting strategic LPS roles.

By using the Manual, the site manager identifies those responsible for meeting the prerequisites and allocates the corresponding tasks. This optimizes both the time and conduct of planning meetings, as it frees participants to focus on analyzing actual constraints and their potential interferences. The constraints are recorded alongside the prerequisites in a spreadsheet that specifies those responsible and the deadlines for their resolution (Figure 6). The deadlines are established based on assumptions regarding the minimum lead times for resource acquisition (Figure 7). It should be noted that the model adopts a six-week horizon for MTP, a timeframe commonly applied in medium- and large-scale construction projects. However, this horizon can be adjusted according to project-specific characteristics.

To further maximize the effectiveness of MTP meetings, it is critical to communicate work packages, prerequisites, and even potential constraints in advance. An agenda with a standard script has been suggested for MTP meetings, designed to clarify and communicate objectives to all stakeholders (Figure 8). Moreover, MTP meetings should promote active participation of representatives from different functional areas, PP&C team, subcontractors, and key site personnel. Top management should also get involved to encourage participation and ongoing collaboration, especially from subcontractors.

During MTP meetings, constraints that may interrupt the production flow are analyzed collaboratively. The model proposes a spreadsheet for recording and monitoring prerequisites and constraints, developed in electronic format with filters and a lessons-learned database (Figure 9). It is regarded as a prototype for future digital systems. This tool automatically generates two indicators: the Percentage of Constraint Removal (PCR) and Anticipated Tasks (TA). These are based on the requirement that work packages consolidate all prerequisites and be cleared of constraints at least two weeks prior to their scheduled start (Ballard, 1997). However, this two-week anticipation may be adjusted according to project goals for constraint removal.

Figure 7 shows one of the practices identified during the empirical study: recording lead-time assumptions related to procurement of materials and services. The form accounts for deadlines required for quotation, approval, and delivery, thereby calculating the minimum lead time for requesting each item. This practice ensures on-time delivery of materials and services, standardizes requisition timelines across projects, and guarantees that other functional areas receive demands within an appropriate timeframe. By avoiding last-minute requests, this practice helps the production function to consolidate its leadership and to establish a good relationship with other areas.

Another practice identified in the empirical study is the basic agenda for MTP meetings (Figure 8). It guides functional areas and other stakeholders to analyze prerequisites and constraints before meetings. This anticipation can sometimes accelerate actions to gather prerequisites or even to remove constraints. Standardizing meeting procedures increases productivity, optimizes participant time, and ensures all critical topics are addressed. Furthermore, it promotes alignment among functional areas, facilitates action prioritization, and strengthens collaborative decision-making.

Figure 9 presents the constraint analysis spreadsheet, which incorporates additional elements to earlier versions that typically show only constraint categories and the PCR indicator. It includes the TA indicator and an email log column to improve communication with responsible staff after meetings. The idea is to find ways in which people from different functional areas or companies can stay in touch between meetings, exchanging information regarding constraint removal.

These practices underscore the need to automate constraint management, recommending the adoption of an online system modeled after Figure 9. Such a system would enable automatic notification of prerequisites and constraints to responsible parties, real-time status tracking, and recording of actual removal dates. This would allow site managers and other stakeholders to access real-time data, expedite verification of constraint-free activities, and implement contingency measures when necessary. However, to be effectively implemented, this process requires top management support and the engagement of functional areas, which would enable the performance monitoring of individual sectors through PCR. Whether developed internally or acquired, project and issue tracking software can enhance the production function’s ability to integrate and coordinate actions.

Following MTP, the model integrates with short-term planning to reinforce quality inspections, verify work package completion, and analyze production problems. The goal is to ensure integrated feedback within the system to support and align both strategic and managerial-level decisions. A critical element is the analysis of causes for non-completion of work packages, linking work package closure control with quality inspections. The model also proposes the analysis of root causes for short-term problems, correlating them with possible MTP failures. This generates the “% MTP Failure” indicator, which is fed into a lessons-learned database of unforeseen or unremoved constraints.

At the end of each month, unremoved constraints and project design changes (e.g., client requests, scope alterations, or specification modifications) are verified to assess their impact on the schedule. The short- and medium-term indicators – PPC, TA, PCR, % MTP Failure, planning failures, and work package completeness – are jointly consolidated and analyzed for learning and deviation analysis. The LBMS-based plan is updated by comparing actual versus planned progress. Corrective actions are subsequently defined based on observed delays or advances and may involve increasing team size, introducing parallel activities, or adjusting activity durations.

Discussion

The evaluation of the proposed MTP model was based on six usefulness constructs and three ease-of-use constructs defined in the methodology section. Although the model has not yet been implemented in practice, it was validated through semi-structured interviews with three experts — one researcher and two consultants with extensive experience in construction planning. The model was first reviewed individually, followed by an in-depth collective discussion.

Evaluators emphasized the comprehensiveness and alignment of the model with MTP demands, highlighting its potential to foster integration across planning levels and functional areas to shield production against disturbances. Among the positive aspects, they particularly stressed the structuring of phase planning for predictability and MTP performance. While conceptually acknowledged in prior studies, its practical adoption has been limited. The proposed model not only systematizes phase planning, proposing a structured form (Figure 6), but also integrates it with other planning levels and functional areas (e.g., procurement, quality, safety). They also highlighted the support of BIM, attention to safety prerequisites, calculation of environmentally sensitive outcomes, and the systematic management of lessons learned on constraints, which is considered a key contribution for institutionalizing organizational learning.

The idea of mapping prerequisites for work packages was considered another strong feature of the model and perceived to be critical for the production function to lead and integrate actions across different areas. The inclusion of safety prerequisites into the Quality System Manual was seen as a very positive initiative. The structured agenda for MTP meetings was also valued for fostering collaboration and engagement across functional areas. However, as mentioned by the evaluators, actual ease of use will depend on the commitment and discipline of different stakeholders, as well as digitalization, which is promising for automating routines, monitoring results, and structuring accessible databases to support MTP decision-making.

Despite recognizing advances, some improvements were suggested, such as replacing the term “anticipations” with “phase planning” to reduce ambiguity. Additionally, detailing and standardizing PP&C procedures within the Quality Management System were recommended as a means to further enhance MTP performance, given that such formalization is accompanied by training sessions and internal audits.

The development of digital tools to structurally record MTP failures was also suggested to enhance control and learning. Strengthening integration with cost and cash flow management was also noted as essential, requiring methodological adjustments and adoption of a specific constraint category. Furthermore, the inclusion of “training needs” as another MTP aspect and constraint category was advised for better integration with the human resources team. These modifications are represented in red in Figure 5. As for physical flow analysis on construction sites, it was regarded as essential but challenging, due to the diversity of project conditions and process characteristics.

This study thus offers significant theoretical and practical contributions. From a theoretical perspective, it advances knowledge by proposing a process model for MTP that holistically and systematically integrates best practices that were previously discussed in a fragmented manner by different authors. The model also integrates practices previously recommended in the literature with novel practices identified through empirical research and expert interviews, thereby advancing the theoretical and practical understanding of LPS implementation. Furthermore, combining SLR, empirical study, and interviews enabled the identification of 32 MTP barriers, 25 of which were recorded for the first time in this study, highlighting underexplored gaps and offering new directions for future research on PP&C in construction.

From a practical standpoint, the model consolidates a set of best practices drawn from multiple sources, aimed at overcoming barriers to MTP implementation and expanding LPS roles. Targeted at construction professionals, such as project managers and planning consultants, the model provides a structured reference to mitigate recurring obstacles, foster greater cross-functional integration between company areas, and enhance production management consistently and reliably.

Among the innovations incorporated into the model, the proposal of an MTP process that empowers the production function to lead other functional areas stands out. Ensuring coherence in decision-making across company departments is crucial for meeting the firm’s competitive objectives and the project’s performance targets. More than integrating plans across different time horizons, it is the ability to align routine actions and strategic initiatives that makes the LPS a genuine source of competitive advantage for the production function.

Conclusions

Adopting a more organizational perspective, this study proposed a process model for MTP that seeks to incorporate more systemic and strategic roles into the LPS, in addition to its well-established production management attributes. The model aims to develop MTP not only as a link between planning levels but also as a mechanism for aligning the actions of different functional areas, thus expanding and enhancing LPS roles within the production function. Nonetheless, some limitations are acknowledged. The model has not yet been implemented in real-world contexts, which limits the assessment of its applicability and effectiveness. Moreover, the empirical context investigated, which focused on residential building projects, may not fully reflect the demands and peculiarities of sectors such as infrastructure construction and complex industrial projects.

Regarding the strategic roles of the LPS, although the model incorporates them into MTP practices, further research is needed to explore existing gaps, particularly in how these roles adapt to different competitive priorities and organizational settings. This issue is especially relevant because organizations emphasize distinct dimensions of competition, such as delivery speed, reliability, and flexibility. Moreover, the current model is largely grounded in the integration of the PP&C system with the Quality Management System. Broader contributions could be achieved if MTP procedures were also integrated with the management systems of other functional areas, such as human resources and sustainability. Additional research addressing these interconnections would be highly valuable for strengthening the roles of the LPS in both production management and production strategy.

Therefore, future research is recommended to:

-

implement and empirically evaluate the proposed model, assessing its impact on the performance of planning and control systems;

-

develop digital systems to support its application and monitoring;

-

investigate its applicability across different types of projects; and

-

deepen analysis of its alignment with production strategy implementation, exploring metrics and indicators to assess its contributions and effectiveness.

-

ANGELIM, V. L.; MIRANDA FILHO, A. N. de; BARROS NETO, J. de P.; HEINECK, L. F. M.; ALVES, A. C. Medium-term planning considering the roles of the Last Planner System in production strategy and management. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 25, e146585, jan./dez. 2025. ISSN 1678-8621 Associação Nacional de Tecnologia do Ambiente Construído. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1678-86212025000100936

Declaração de Disponibilidade de Dados

Os dados de pesquisa estão disponíveis no corpo do artigo.

References

- ACUR, N. et al The formalization of manufacturing strategy and its influence on the relationship between competitive objectives, improvement goals and action plans. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, v. 23, n. 10, p. 1114–1141, 2003.

- ALVES, T. C. L.; TOMMELEIN, I. D.; BALLARD, H. G. Simulation as a tool for production system design in construction. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 14., Santiago, 2006. Proceedings […] Santiago, 2006.

- ALVES, T. da C. L.; BRITT, K. Working to improve the lookahead plan. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 19., Lima, 2011. Proceedings […] Lima, 2011.

- BALLARD, G.; HOWELL, G. An update on Last Planner. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 11., Virgínia, 2003. Proceedings […] Virgínia, 2003.

- BALLARD, G.; HOWELL, G. Shielding production: essential step in production control. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 124, n. 1, p. 11–17, 1998.

- BALLARD, G.; TOMMELEIN, I. Current process benchmark for the Last Planner System. Lean Construction Journal, Berkeley, p. 57–89, 2016.

- BALLARD, G.; TOMMELEIN, I. D. Current process benchmark for the last planner® system of project planning and control Berkeley: University of California, 2021. Technical Report, Project Production Systems Laboratory (P2SL).

- BALLARD, H. G. Lookahead planning: the missing link in production control. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 5., Gold Coast, 1997. Proceedings […] Gold Coast, 1997.

- BALLARD, H. G. The Last Planner System of production control. Birmingham, 2000. 192f. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, 2000.

- BARROS NETO, J. P. The relationship between strategy and lean construction. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 10., Gramado, 2002. Proceedings [...] Gramado, 2002.

- BELLAVER, G. et al Implementing lookahead planning and digital tools to enable scalability and set of information in a multi-site lean implementation. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 30., Edmonton, 2022. Proceedings […] Edmonton, 2022.

- BORTOLAZZA, R. C.; FORMOSO, C. T. A quantitative analysis of data collected from the last planner system in Brazil. In: THE 14TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 14., Santiago, 2006. Proceedings […] Santiago, 2006.

- BRITT, K. et al Lessons learned from the make ready process in a hospital project. In: THE 22nd ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 22., Oslo, 2014. Proceedings […] Oslo, 2014.

- CASTILLO, T. D. et al. Exploring the Relationship Between Social Networks and Performance in the Last Planner System. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 26., Chennai, 2018. Proceedings [...] Chennai, 2018.

- CHOO, H. J.; TOMMELEIN, I.D. Space scheduling using flow analysis. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 7., Berkeley, 1999. Proceedings […] Berkeley, 1999.

- CHUA, D. K. H.; SHEN, L. J.; BOK, S. H. Constraint-based planning with integrated production scheduler over internet. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 129, n. 3, p. 293–301, 2003.

- CHUA, D.; JUN, S.; HWEE, B. Integrated production scheduler for construction look-ahead planning. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 7., Berkeley, 1999. Proceedings […] Berkeley, 1999.

- CHUA, K. H.; SHEN, L. J. Constraint modeling and buffer management with integrated production scheduler. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 9., Singapore, 2001. Proceedings […] Singapore, 2001.

- COELHO, H. O. Diretrizes e requisitos para o planejamento e controle da produção em nível de médio prazo na construção civil Porto Alegre, 2003. 135f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia civil) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Civil, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2003.

- CORRÊA, H. L.; CORRÊA, C. A. Administração de produção e operações: manufatura e serviços: uma abordagem estratégica. 4. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2017.

- DANIEL, E. I.; PASQUIRE, C.; BRENDA, M. Exploring the relationship between the Last Planner System and social capital. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 27., Dublin, 2019. Proceedings […] Dublin: IGLC, 2019.

- DAVE, B.; SEPPÄNEN, O.; MODRICH, R. U. Modeling information flows between last planner and location based management system. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 24., Boston, 2016. Proceeding [...] Boston, 2016.

- DONG, N. Automated look-ahead schedule generation and optimization for the finishing phase of complex construction projects Stanford, 2012. Doctor of Philosophy, CIFE Technical Report, Stanford University, Stanford, 2012.

- DONG, N. et al A genetic algorithm-based method for look-ahead scheduling in the finishing phase of construction projects. Advanced Engineering Informatics, v. 26, n. 4, p. 737–748, 2012.

- DONG, N. et al. A method to automate look-ahead schedule (LAS) generation for the finishing phase of construction projects. Automation in Construction, v. 35, p. 157–173, 2013.

- DRESCH, A.; LACERDA, D. P.; ANTUNES JÚNIOR, J. A. V. Design science research: método de pesquisa para avanço da ciência e tecnologia. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2015.

- FERNANDEZ-SOLIS, J. L. et al Production theory: Toward a new paradigm in construction. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 21., Fortaleza, 2013. Proceedings […] Fortaleza: IGLC, 2013.

- FISCHER, M. Reshaping the life cycle process with virtual design and construction methods. In: VIRTUAL Futures for Design, Construction & Procurement. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2009.

- FORMOSO, C. T. et al. The identification and analysis of making-do waste: insights from two Brazilian construction sites. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre v. 17, n. 3, p. 183-197, jul./set. 2017.

- GAO, S.; LOW, S. P. The Last Planner System in China’s construction industry: a SWOT analysis on implementation. International Journal of Project Management, v. 32, n. 7, p. 1260–1272, 2014.

- GIRKE, R. et al From cost to capability: technology multiplier in EV manufacturing strategy. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, v. 82, p. 319-332, 2025.

- HAMZEH, F. R. et al. Is improvisation compatible with look ahead planning? An exploratory study. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 20., San Diego, 2011. Proceedings […] San Diego, 2012.

- HAMZEH, F. R. et al Understanding the role of “tasks anticipated” in lookahead planning through simulation. Automation in Construction, v. 49, p. 18–26, 2015.

- HAMZEH, F. R. Improving construction workflow: the role of production planning and control Berkeley, 2009. 271f. Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering, Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, 2009.

- HAMZEH, F. R. The lean journey: Implementing the last planner system in construction. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 19., Lima, 2011. Proceedings […] Lima, 2011.

- HAMZEH, F. R.; BALLARD, G.; TOMMELEIN, I. D. Improving construction work flow: the connective role of lookahead planning. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 16., Manchester, 2008. Proceedings […] Manchester, 2008.

- HAMZEH, F. R.; ZANKOUL, E.; ROUHANA, C. How can ‘tasks made ready’ during lookahead planning impact reliable workflow and project duration? Construction Management and Economics, v. 33, n. 4, p. 243–258, 2015.

- HAMZEH, F.; BALLARD, G.; TOMMELEIN, I. D. Rethinking lookahead planning to optimize construction workflow. Lean Construction Journal, p. 15–34, 2012.

- HAMZEH, F.; LANGERUD, B. Using simulation to study the impact of improving lookahead planning on the reliability of production planning. In: SIMULATION CONFERENCE, Grand Arizona Resor Phoenix, 2011. Proceedings […] Grand Arizona Resor Phoenix, 2011.

- HILL, T. J. Manufacturing strategy Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1993.

- HITT, M. A.; IRELAND, D.; HOSKISSON, R. E. Strategic management: competitiveness and globalization Mason: South-Western College Publishing, 2003.

- JACOBS, G. F. Review of lean construction conference proceedings and relationship to the Toyota production system framework Colorado, 2010. 165 f. Doctor of Philosophy, Colorado State University, Colorado, 2010.

- JAVANMARDI, A. et al. Constraint removal and work plan reliability: a bridge project case study. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 26., Chennai, 2018. Proceedings […] Chennai, 2018.

- KASANEN, E.; LUKKA, K.; SIITONEN, A. The constructive approach in management accounting research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, v. 5, n. June 1991, 1993.

- KEMMER, S. et al. Implementing last planner in the context of social housing retrofit. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 24., Boston, 2016. Proceedings […] Boston, 2016.

- KEMMER, S. L. et al. Medium-term planning: contributions based on field application. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 13., Sydney, 2007. Proceedings [...] Sydney, 2007.

- KENLEY, R. Project micro-management: practical site planning and management of work flow. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 12., Helsingor, 2004. Proceedings [...] Helsingor, 2004.

- KHANH, H. D.; KIM, S. Y. A survey on production planning system in construction projects based on Last Planner System. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, v. 20, n. 1, p. 1–11, 2016.

- KIM, Y. H. et al. Top-down, bottom-up, or both? Toward an integrative perspective on operations strategy formation. Journal of Operations Management, v. 32, p. 462–474, 2014.

- KIM, Y. W.; JANG, J. W. Applying organizational hierarchical constraint analysis to production planning. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 14., Santiago, 2006. Proceedings [...] Santiago, 2006.

- KOSKELA, L. An exploration towards a production theory and its application to construction. Espoo, 2000. Tese (Doutorado em Engenharia Civil), Helsinki University of Technology, Espoo, 2000.

- KOSKELA, L. Is structural change the primary solution to the problems of construction? Building Research and Information, v. 31, n. 2, p. 85-96, 2003.

- KOSKELA, L. Making-do: the eighth category of waste. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 12., Elsinore, 2004. Proceedings […] Elsinore, 2004.

- LAGOS, C. I. et al. Methodology to quantitatively assess collaboration in the make-ready process. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 31., Lille, 2023. Proceedings […] Lille, 2023.

- LAPPALAINEN, E. et al. Findings on the use of the Last Planner System: a case study. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 30., Edmonton, 2022. Proceedings […] Edmonton, 2022.

- MAYLOR, H. et al. It worked for manufacturing…! Operations strategy in project-based operations. International Journal of Project Management, v. 33, p. 103–115, 2015.

- MIRANDA FILHO, A. N.; HEINECK, L. F. M.; COSTA, J. M. A project-based view of the link between strategy, structure and lean construction. In: CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 19., San Diego, 2011. Proceedings […] San Diego, 2011.

- MOHAN, S. B.; IYER, S. Effectiveness of lean principles in construction. In: 13TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 13., Sydney, 2005. Proceedings […] Sydney, 2005.

- MURGUIA, D. et al. Digital measurement of construction performance: data-todashboard strategy. In: WORLD BUILDING CONGRESS, 22., Melbourne, 2022. Proceedings […] Melbourne, 2022.

- NAKAGAWA, Y.; SHIMIZU, Y. Toyota production system adopted by building construction in Japan. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 12., Helsingør, 2004. Proceedings […] Helsingør, 2004

- OLIVIERI, H.; GRANJA, A. D.; PICHI, F. A. Planejamento tradicional, Location-Based Management System e Last Planner System: um modelo integrado. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 16, n. 1, p. 265-283, jan./mar. 2016.

- PEREZ, A. M.; GHOSH, S. Barriers faced by new-adopter of Last Planner System®: a case study. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 25, n. 9, p. 1110–1126, 2018.

- PRIVEN, V.; SACKS, R. Effects of the Last Planner System on social networks among construction trade crews. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 23., Perth, 2015. Proceedings […] Perth, 2015.

- RIBEIRO, F. S.; COSTA, D. B.; MAGALHÃES, P. A. Phase Schedule Implementation and the impact for subcontractors. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 25., Heraklion, 2017. Proceedings […] Heraklion, 2017.

- SALVATIERRA, J. L. et al Lean diagnosis for chilean construction industry: towards more sustainable Lean practices and tools. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 23., Perth, 2015. Proceedings […] Perth, 2015.

- SCHRAMM, F. K.; RODRIGUES, A. A.; FORMOSO, C. T. The role of production system design in the management of complex projects. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 14., Santiago, 2006. Proceedings […] Santiago, 2006.

- SEPPÄNEN, O.; BALLARD, G.; PESONEN, S. The combination of last planner system and location-based management system. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 18., Haifa, 2010. Proceedings […] Haifa, 2010.

- SEPPÄNEN, O.; MODRICH, R.-U.; BALLARD, G. Integration of Last Planner System and Location-Based Management System. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 23., Perth, 2015. Proceedings […] Perth, 2015.

- SHAVARINI, S. K. et al Operations strategy and business strategy alignment model: case of Iranian industries. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, v. 33, n. 9, p. 1108-1130, 2013.

- SLACK, N. et al. Administração da produção 8. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2018.

- TOLEDO, M. et al. Using 4D models for tracking project progress and visualizing the owner’s constraints in fast-track retail renovation projects. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 22., Oslo, 2014. Proceedings […] Oslo, 2014.

- TOLEDO, M.; OLIVARES, K.; GÓNZALEZ, V. Exploration of a Lean-Bim Planning Framework: a Last Planner System and Bim-Based case study. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 24., Boston, 2016. Proceedings […] Boston, 2016.

- TOMMELEIN, I. D.; BALLARD, H. G. Look-ahead-Planning-Screening-and-Pulling. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 2., São Paulo, 1997. Proceedings […] São Paulo, Brazil, 1997.

- WESZ, J.; FORMOSO, C. T.; TZORTZOPOULOS, P. Design process planning and control: last planner system adaptation. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 21., Fortaleza, 2013. Proceedings […] Fortaleza, 2013.

- WHEELWRIGHT, S. Manufacturing strategy: defining the missing link. Strategic Management Journal, v. 5, p. 77–91, 1984.

- YIN, R. K. Pesquisa qualitativa do início ao fim 5.ed. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2016.

Edited by

-

Editores:

Carlos Torres Formoso, Ariovaldo Denis Granja e Dayana Bastos Costa

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

01 Dec 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

25 Mar 2025 -

Accepted

08 Oct 2025

Medium-term planning considering the roles of the Last Planner System in production strategy and management

Medium-term planning considering the roles of the Last Planner System in production strategy and management