Abstract

The application of repair materials is essential for maintaining the service life of reinforced concrete structures. Dimensional compatibility with the substrate is crucial for the repair material. This study assesses the impact of graphene and carbon nanotubes on dimensional stability and bond strength. Bulk density and consistency index were analysed in the fresh state, while weight loss, dry shrinkage, coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) and bond strength were evaluated in the hardened state. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to assess the impact of carbon nanoparticles on the microstructure. Graphene particles can mitigate dimensional variation caused by dry shrinkage. However, incorporating carbon nanotubes led to higher shrinkage due to the refinement of the cementitious matrix and an increase in capillary pressure. Furthermore, using nanoparticles combined with superplasticisers enhanced bond strength by increasing adhesion points in the interfacial transition zone between the repair and the concrete substrate. SEM analyses demonstrated the formation of crystals on the graphene surface and the good dispersion of carbon nanotubes into the cementitious matrix.

Keywords

Bond strength; Graphen; Carbon nanotube; Drying shrinkage; Dimensional variation

Resumo

A aplicação de materiais de reparo é essencial para a manutenção da vida útil de estruturas de concreto armado. A compatibilidade dimensional com o substrato é crucial para o material de reparo. Este estudo avalia o impacto do grafeno e nanotubos de carbono na estabilidade dimensional e aderência. A densidade aparente e o índice de consistência foram analisados no estado fresco, enquanto a perda de massa, a retração, coeficiente de expansão térmica (CTE) e aderência foram avaliados no estado endurecido. A microscopia eletrônica de varredura (MEV) foi empregada para avaliar a influência das nanopartículas de carbono na microestrutura. As partículas de grafeno podem mitigar a variação dimensional causada pela retração. No entanto, a incorporação de nanotubos de carbono resultou em maior retração devido ao refinamento da matriz cimentícia e ao aumento da pressão capilar. Além disso, o uso de nanopartículas combinadas com superplastificantes melhorou a aderência pelo aumento os pontos de ancoragem na zona de transição entre o material de reparo e o substrato de concreto. As análises de MEV demonstraram a formação de cristais na superfície do grafeno e a boa dispersão dos nanotubos de carbono na matriz cimentícia.

Palavras-chave

Aderência; Grafeno; Nanotubo de carbono; Retração por secagem; Variação dimensional

Introduction

Concrete structures are exposed to various environmental factors that significantly impact their durability. The extent of these effects depends on exposure conditions, often necessitating repairs to restore functionality. A common technique involves removing damaged areas and applying repair materials to re-establish structural integrity (Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022).

The efficiency of a repair system relies on identifying the cause and extent of damage and selecting appropriate materials and repair strategy techniques (ACI, 2014). Inadequate material selection and poor application are the primary reasons for repair failures (Su et al., 2021). The National Association of Corrosion Engineers Impact Report (Koch et al., 2016) states that nearly 50% of reinforced concrete structures require repairs within ten years of construction. In this context, Brazil lacks specific regulations for repair materials, which can lead to inconsistencies in material selection and performance requirements (Silva Junior; Helene, 2001).

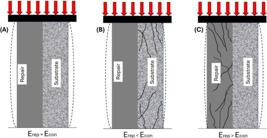

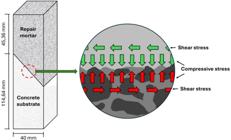

Achieving dimensional compatibility between the repair material and the substrate is essential for long-term performance (Medeiros; Helene; Selmo, 2009; Toklu; Şimşek; Aruntaş, 2019; Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022). Compatibility encompasses physical, chemical, and dimensional properties that influence system behaviour, which includes the repair material itself, the concrete substrate, and an interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between them (Emmons; Vaysburd, 1996; Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022). Dimensional stability, influenced by elastic modulus, coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), and dry shrinkage, plays a crucial role in repair performance. In structural repairs, the elastic modulus (Erep) should closely match that of the substrate (Econ) to ensure uniform stress distribution (ACI, 2014), as presented in Figure 1(A). Mismatched modulus values can lead to stress concentration, cracking, and damage, as shown in Figures 1(B) and 1(C).

Mangat and O’Flaherty (1999, 2000) examined how stiffness affects repair material performance in bridge structural elements. Their findings suggest that when Erep > Econ, strain transfer is more efficient, forming well-defined deformation zones. Conversely, when Erep < Econ, strain transfer is hindered, increasing tensile stresses in the bond zone, leading to cracking. This aligns with Yunpeng et al. (2016), who highlighted the role of elastic modulus in stress/strain transfer between repair and substrate. The American Concrete Institute, in its Guide to Materials Selection for Concrete Repair 546.3R (ACI, 2014), recommends that repair materials exhibit an elastic modulus compatible with the substrate concrete in structural repair applications. In contrast, for non-structural repair applications, the elastic modulus of the repair should be lower than that of the substrate concrete to accommodate strains caused by shrinkage or other volumetric changes. These recommendations are further supported by the research of Hassan, Brooks and Al-Alawi (2001) and Toklu, Şimşek and Aruntaş (2019).

Shrinkage in cement-based materials leads to volumetric changes in both the fresh and hardened states due to the loss of adsorbed water in the crystal structure of the hydrated paste when exposed to an environment with relative humidity below the saturation point (Mehta; Monteiro, 2008). Plastic shrinkage occurs within the first 24 hours and is linked to the material setting, while drying shrinkage, which happens in the hardened state, takes place after 24 hours (Wu et al., 2017). Furthermore, other types of shrinkage can occur, such as autogenous and carbonation shrinkage (Metalssi et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2017; Lu; Li; Huang, 2021).

Dry shrinkage is influenced by factors such as supplementary cementitious materials (SCM), water-to-cement ratio, cement content, aggregate size, air entrainment, chemical admixtures, overlay thickness, and humidity (Emmons; Vaysburd, 1996; Hassan; Brooks; Al-Alawi, 2001; Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022). These factors impact pore formation and distribution, affecting internal stresses during drying. Achieving dimensional compatibility is challenging once the concrete substrate has stabilised and no longer undergoes shrinkage. However, the repair material will still display shrinkage at early ages (Mangat; O’Flaherty, 1999).

Figure 2 demonstrates the effect of dry shrinkage on a repaired system. Without shrinkage, no stress is induced in the ITZ (Figure 2(A)). However, once shrinkage occurs, dimensional variability takes place, leading to shear stresses at the interface between the repair, steel, and substrate (Figure 2(B)). Cracking may occur when these stresses exceed the material’s shear strength (Araújo, 2022).

Mangat and O’Flaherty (1999) observed that, in repairs applied to reinforced concrete, the tensile stresses caused by restrained shrinkage were higher in the ITZ between the repair and the steel reinforcement than in the ITZ between the repair and substrate. This suggests that cracks may initiate at the repair-steel interface due to the higher incompatibility between the elastic modulus of steel and the repair.

In addition to dry shrinkage, the CTE, which reflects how cementitious materials expand or contract in response to temperature changes, significantly impacts dimensional compatibility, particularly in environments with substantial temperature fluctuations (Zhou; Shu; Huang, 2014). The CTE of cementitious materials depends on their multiphase composition, including binder type, chemical admixtures, aggregates type and ratio, and fibres. Aggregates have the most significant influence due to their mineralogical composition. High CTE values lead to higher stresses in the ITZ, increasing the susceptibility to degradation under thermal fluctuations (Won, 2005).

In this context, thermal incompatibility between repair and substrate directly affects the repair system efficiency. The adherence between the phases restricts dimensional changes, inducing stresses on the same mechanism as those caused by dry shrinkage. Furthermore, temperature fluctuation increases these stresses within the materials and the ITZ, as illustrated in Figure 2(B) (Emmons; Vaysburd, 1996; Zhou; Shu; Huang, 2014; Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022).

Durability is critical in selecting repair materials, as it provides a barrier against aggressive agents. Identifying the specific agents causing structural damage is essential to choosing the most suitable material. Studies have shown that incorporating SCM, such as silica fume, enhances the durability. SCMs react with portlandite through the pozzolanic reaction, forming additional C-S-H in the microstructure, reducing water absorption, and improving surface electrical resistivity, thereby increasing overall durability (Wosniack et al., 2021; Araújo et al., 2022; Araújo; Macioski; Medeiros, 2022; Araújo et al., 2024). However, a mismatch in electrical resistivity between the repair material and concrete substrate can lead to electrochemical incompatibility, increasing corrosion potential (Remenche et al., 2024).

The bond strength between repair and substrate is a key indicator of repaired system performance, enabling the composite to withstand mechanical and environmental stresses (Trigo; Conceição; Liborio, 2010; Sanchéz et al., 2018). The ITZ, characterised by high porosity and non-hydrated cement particles, significantly influences bond strength. Dry substrates absorb water from fresh repair material, reducing the water-to-cement ratio and porosity, while saturated substrates supply water to the ITZ, enhancing hydration (Zhou; Ye; Breugel, 2016).

Dimensional variation effects caused by dry shrinkage in repair systems – (A) Repair with no shrinkage and (B) repair with shrinkage

Rheological properties, such as viscosity, also influence bond strength, with lower-viscosity mortars exhibiting better substrate coverage and adhesion (Costa; Cincotto; Pileggi, 2005; Kudlanvec Junior, 2017; Bentz et al., 2018). The American Concrete Institute (ACI, 2014) recommends a minimum direct tension bond strength of 1.4 MPa, though higher values than the minimum standard requirements are advisable due to variable application conditions.

Nanomaterials, such as graphene and carbon nanotube, enhance the cement matrix by acting as nucleation sites for hydration reactions and contributing to matrix densification through filling effects (Saleem; Zaidi; Alnuaimi, 2021; Araújo, 2022; Araújo et al., 2022). Graphene, a carbon allotrope with a hexagonal honeycomb structure, exhibits exceptional mechanical properties, including a tensile strength of up to 130 GPa and an elastic modulus of 1 TPa. These properties, along with those of its derivatives – graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and pristine graphene (PRG) – have attracted significant attention in cementitious materials research. However, their hydrophobic nature makes dispersion in aqueous solutions challenging, leading to particle agglomeration and potential defects in the cement matrix, which can reduce mechanical performance. On the other hand, when well dispersed, these particles improve compressive strength, flexural strength, and elastic modulus in cementitious composites (Liu; Li; Xu, 2019; Qureshi; Panesar, 2019; Araújo et al., 2022).

Carbon nanotubes are formed by rolling graphene sheets and are categorised as single-walled (SWCNT) or multi-walled (MWCNT). SWCNTs consist of a single graphene sheet, while MWCNTs contain multiple layers (Zarbin; Oliveira, 2013). Carbon nanotubes reinforce the cementitious matrix, enhancing compressive and flexural strength, with the latter showing more pronounced improvements (Liew; Kai; Zhang, 2016). Their nanometric dimensions refine pore structures, reducing permeability. However, in the fresh state, carbon nanotubes decrease workability due to their high aspect ratio, and in the hardened state, they increase autogenous shrinkage and dimensional variation under sulphate attack. The effectiveness of both graphene and carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites depends critically on their dispersion (Konsta-Gdoutos; Metaxa; Shah, 2010; Marcondes et al., 2015, 2019; Medeiros et al., 2015; Marcondes; Medeiros, 2016; Souza et al., 2017; Mendes; Medeiros, 2023).

A survey of studies focusing on ‘dry shrinkage’, ‘graphene’, and/or ‘carbon nanotube’ was conducted according to the Methodi Ordinatio proposed by Pagani, Kovaleski and Resende (2015) on the Science Direct database. Table 1 shows the summary of studies found. It is possible to note a knowledge gap in studies that evaluate the dimensional stability and bond strength when incorporating carbon nanoparticles in cementitious composites.

In this context, this study aims to discuss the influence of carbon-based nanoparticles, specifically graphene and carbon nanotube, on the dimensional stability and bond strength of repair cement mortars. It focuses on properties such as dry shrinkage, weight loss, CTE, and bond strength (via slant shear test), providing valuable insights into the potential application of these materials in repair mortars. Furthermore, the microstructural analysis was correlated with these properties to enhance the understanding of their performance.

Experimental program

Materials characterisation

A high-early-strength cement type CP V-ARI (similar to ASTM type III) containing up to 10% limestone filler with a specific density of 3.09 g/cm³ was used as a binder. Table 2 presents the chemical composition and mechanical characterisation of CP V-ARI.

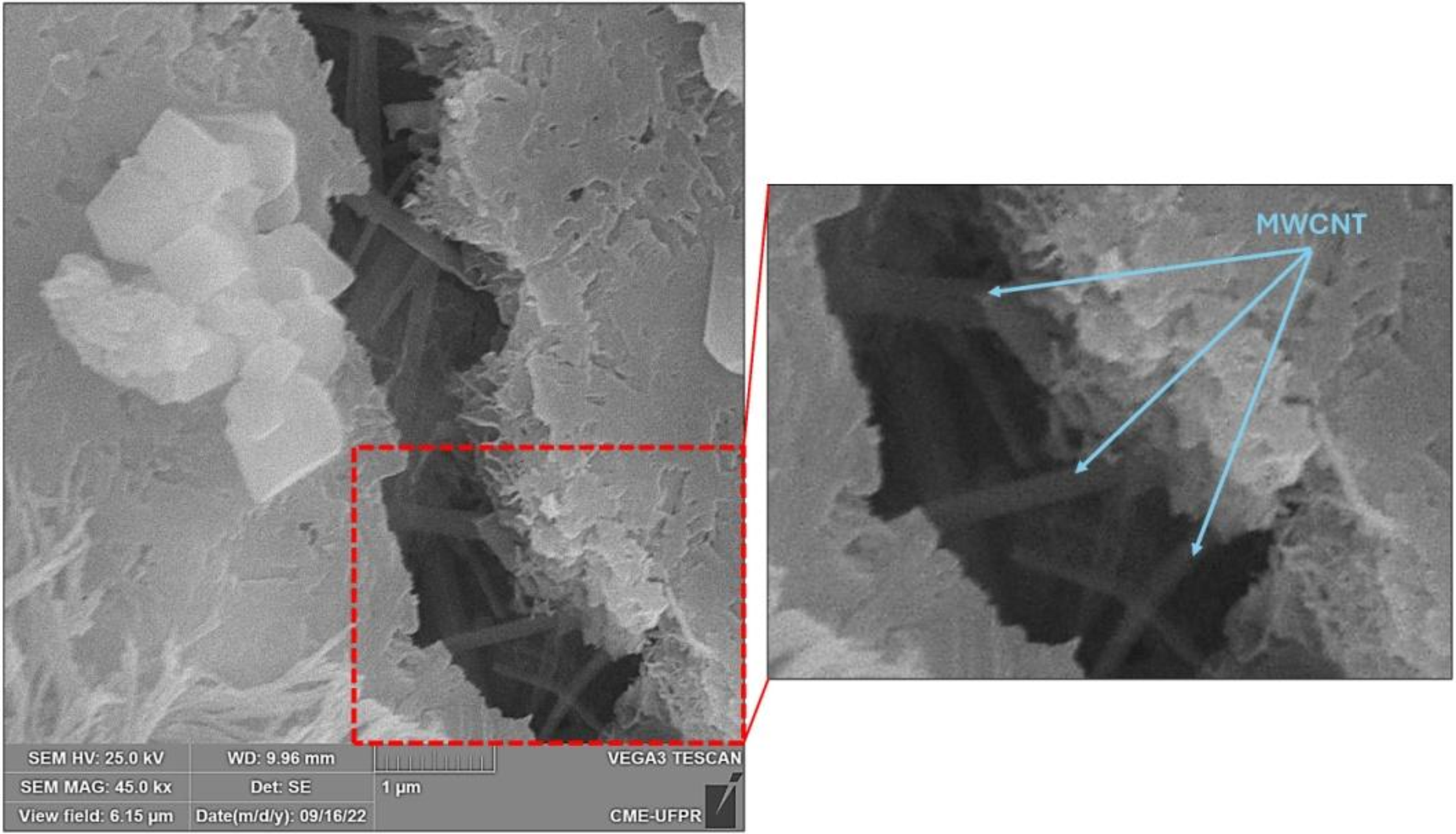

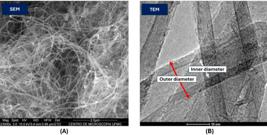

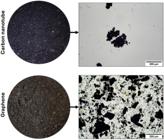

The MWCNT used in this study was synthesised via chemical vapour deposition (CVD) using ethylene as a carbon precursor and iron and cobalt supported on Al2O3 as a catalyst/subtract complex. The production was carried out by the Centre for Technology in Nanomaterials and Graphene (CTNANO) at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil. Figure 3 presents the Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images provided by the manufacturer, highlighting the entanglement (Figure 3(A)) of MWCNT due to its high aspect ratio, high specific surface area and energy originating from van der Waals forces, which increases their tendency to form these clusters (Atif; Inam, 2016). Figure 3(B) shows the outer and inner diameters, a characteristic influenced by the production process (Herbst; Macêdo; Rocco, 2004). Table 3 summarises the characterisation data supplied by the manufacturer.

The graphene particles used were in powder form and had a density of 2.38 g/cm³ measured according to NM 23 (ABNT, 2000a). Figure 4 shows the nanoparticles visible to the naked eye and images obtained by a transmitted light microscope (Amtechne, XSZ-N107). MWCNT clusters can be observed, corroborating with SEM analysis (Figure 3(A)). Furthermore, graphene particles have a high size variability with particles up to 200 µm.

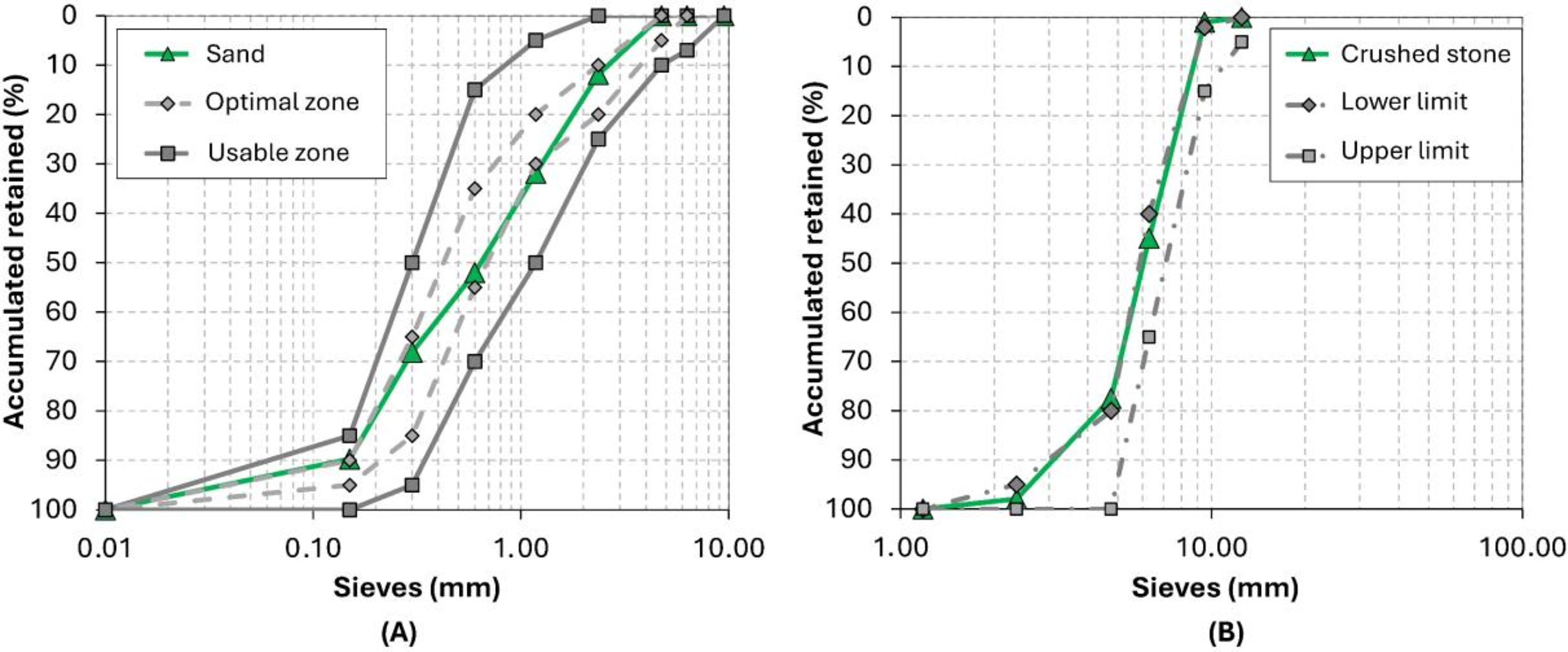

Natural sand and granitic crushed stone were used as fine and coarse aggregates, respectively. Table 4 presents the aggregate characterisation and the respective standards. The crushed stone has a maximum aggregate size of 9.5 mm, which is adequate for the specimen mortar dimensions and the mould (prism of 40x40x160 mm). Figure 5 shows the particle size distributions of the aggregates obtained according to NM 248 (ABNT, 2001).

A polycarboxylate ether-based (PCE) superplasticiser with a specific density of 1.07 g/cm³ was employed to improve the dispersion of nanoparticles. The content was set at 0.15% of the cement weight in the reference mixture (without nanomaterials) and 0.50% in mixtures containing nanomaterials. Previous studies have used up to 3.0% dispersant ratios to achieve effective nanoparticle dispersion (Marcondes et al., 2015; Medeiros et al., 2015, 2019; Souza et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). In this study, the low-selected dosage aimed to maintain a consistency index between 260 and 290 mm, ensuring adequate workability for casting the mortar samples in prismatic moulds without compromising the material’s properties.

MWCNT and graphene particles visible to the naked eye (left) and observed under a transmitted light microscope (right)

–

Repair cement mortar and concrete substrate

The repair cement mortar mix design was adopted from the literature (Souza et al., 2017; Toklu; Şimşek; Aruntaş, 2019; Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022) and fixed as 1:2.5:0.40 (cement: fine aggregate: water), by mass. Four mixtures were cast: I) MREF – reference mixture without any nanomaterial addition; II) MCNT – Addition of 0.2 wt% of MWCNT; III) MGRAF – Addition of 0.2 wt% of graphene; IV) MCNGR – Addition of 0.2 wt% of carbon nanotube and 0.2 wt% of graphene, all the dosage by weight of cement.

Although the proportion of both materials in the MCNGR mixture is higher than in the MCNT and MGRAF mixtures, this increase is justified by the distinct ways they can act due to their differing granulometry. Carbon nanotube is essentially nanometric, while graphene particles also include micrometric dimensions, which influence their interaction distinctly within the cement matrix.

These dosages are based on previous studies that have utilised carbon nanotubes up to 0.6 wt% and graphene up to 0.5 wt% (Marcondes et al., 2015; Medeiros et al., 2015; Isfahani; Li; Redaelli, 2016; Song et al., 2017; Souza et al., 2017; Medeiros et al., 2019; Qureshi; Panesar, 2019; Tafesse; Kim, 2019; Zhao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Araújo et al., 2022; Gholampour et al., 2023; Ikhlasi; Gholampour; Vincent, 2023; Mendes; Medeiros, 2023; Kiamahalleh et al., 2024). Furthermore, a rational proportion of these nanomaterials is desirable due to their high cost and dispersion challenges in cementitious materials. In this context, this study established a reasonable dosage to produce repair materials suitable for practical applications, ensuring that the prescribed limits found in the literature were not exceeded, even in combinations. Material consumption per m³ of each mixture is presented in Table 5.

The sonication process is widely used for dispersing nanoparticles (Chen et al., 2014; Medeiros et al., 2015; Souza et al., 2017; Araújo, 2022; Araújo et al., 2022). This physical method involves subjecting the solution (liquid medium) to ultrasound mechanical vibrations. These vibrations cause the collapse of microbubbles, a phenomenon known as cavitation, which facilitates the separation and dispersion of nanoparticles (Parveen; Rana; Fangueiro, 2013; Korayem et al., 2017). Although this process can have a secondary effect due to shear vibration, the nanoparticles can be chopped due to the energy applied to the process, reducing the efficiency of its utilisation in the cement matrix (Chen et al., 2014).

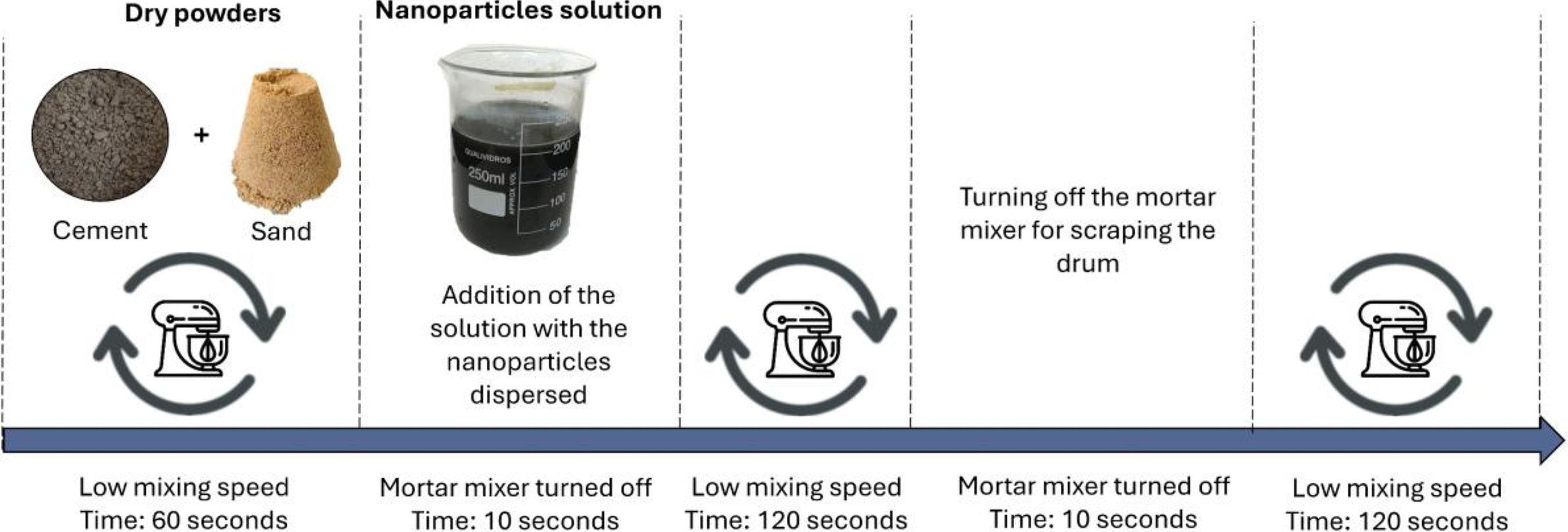

An ultrasonic bath (Schuster, Model L-100, operating at 60 Hz and 160 W) was used to apply the sonication process in a solution composed of water, nanoparticles, and a superplasticiser for 40 minutes. Figure 6 presents the mixing steps of cement mortars, which add up to 320 seconds.

The concrete substrate has a mix design of 1:1.61:2.99:0.38 (cement: fine aggregate: crushed stone: water), with a 425 kg/m³ cement consumption. According to NBR 9779 (ABNT, 2013) and NBR 5739 (ABNT, 2018b), capillary water absorption and compressive strength were utilised as characterisation parameters of the substrate, respectively. The capillary water absorption test results were used to calculate the sorptivity coefficient (KS) as per TC 116-PCD (RILEM, 1999). Table 6 presents the concrete substrate characterisation. The values are the average of four-cylinder specimens with dimensions of φ10x20 cm for both tests.

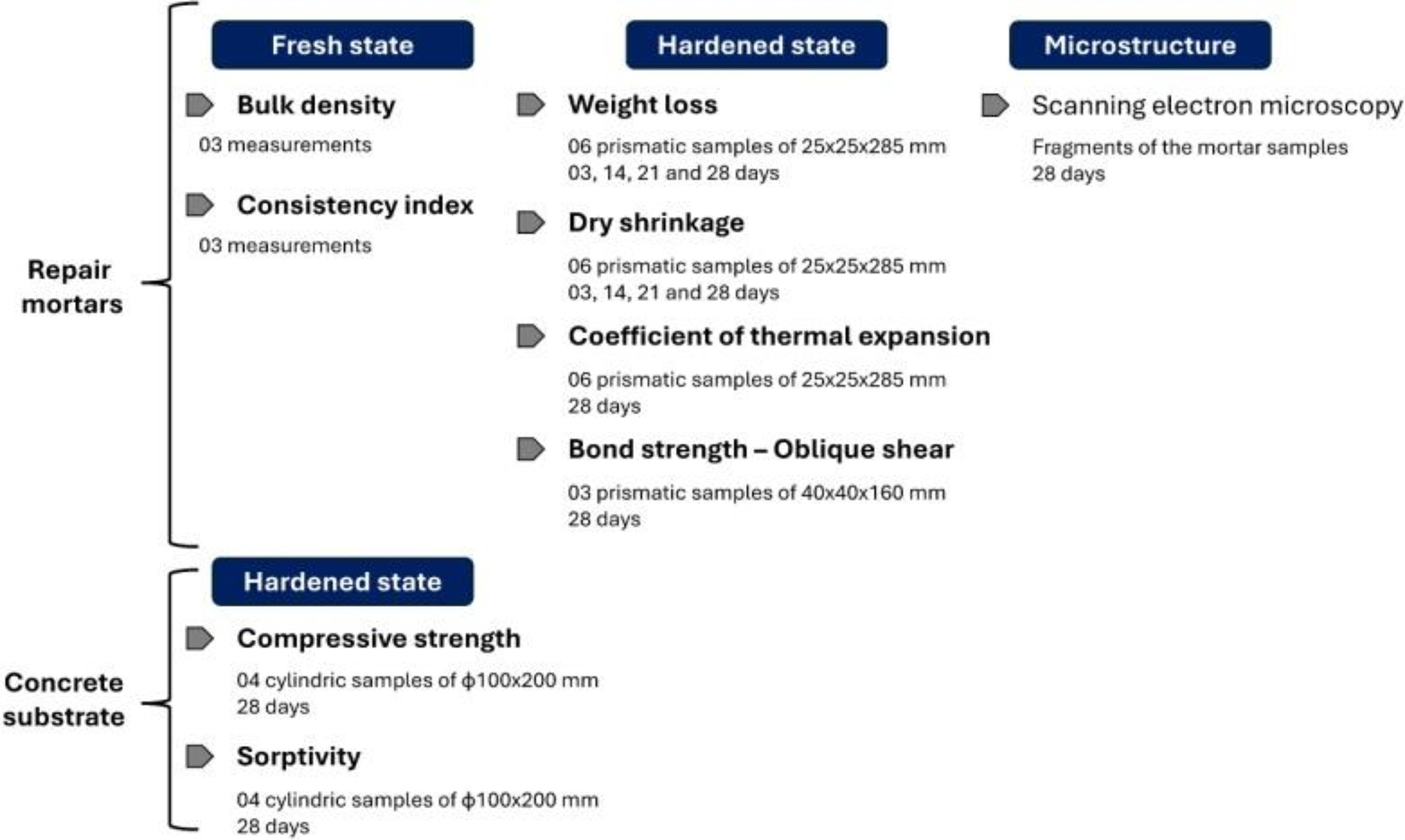

Physical and mechanical tests

The bulk density and consistency index (flow table) of cement mortars were evaluated in the fresh state according to NBR 13278 (ABNT, 2005a) and NBR 13276 (ABNT, 2016). For the former, a metallic mould with a known volume was used, and the measurement was performed immediately after mixing. For the latter, the mean of three diameter measures was taken as the value after submitting the fresh mortar to some fixed drops on the flow table.

According to NBR 15261 (ABNT, 2005b), weight loss and dry shrinkage by the linear dimensional variation (LDV) were measured at 03, 14, 21, and 28 days in the hardened state. The specimens for these tests were kept in a dry chamber with a temperature of 23±2 °C and relative humidity of 50±5%. The shrinkage was calculated according to Equation 1.

Where:

ΔL is the length change of the specimen (%);

CRD is the difference between the comparator reading of the specimen and the reference bar (mm); and

G is the gage length (mm).

The CTE (α) was calculated according to Equation 2 using the same type of sample casting for the LDV.

Where:

α is the coefficient of thermal expansion (ºC-1);

L0 is the initial length (mm);

Lf is the length at age ‘‘i’’ (mm);

T0 is the initial temperature (ºC); and

Tf is the final temperature (ºC).

The initial test temperature was 23 °C, and the final was 100 °C.

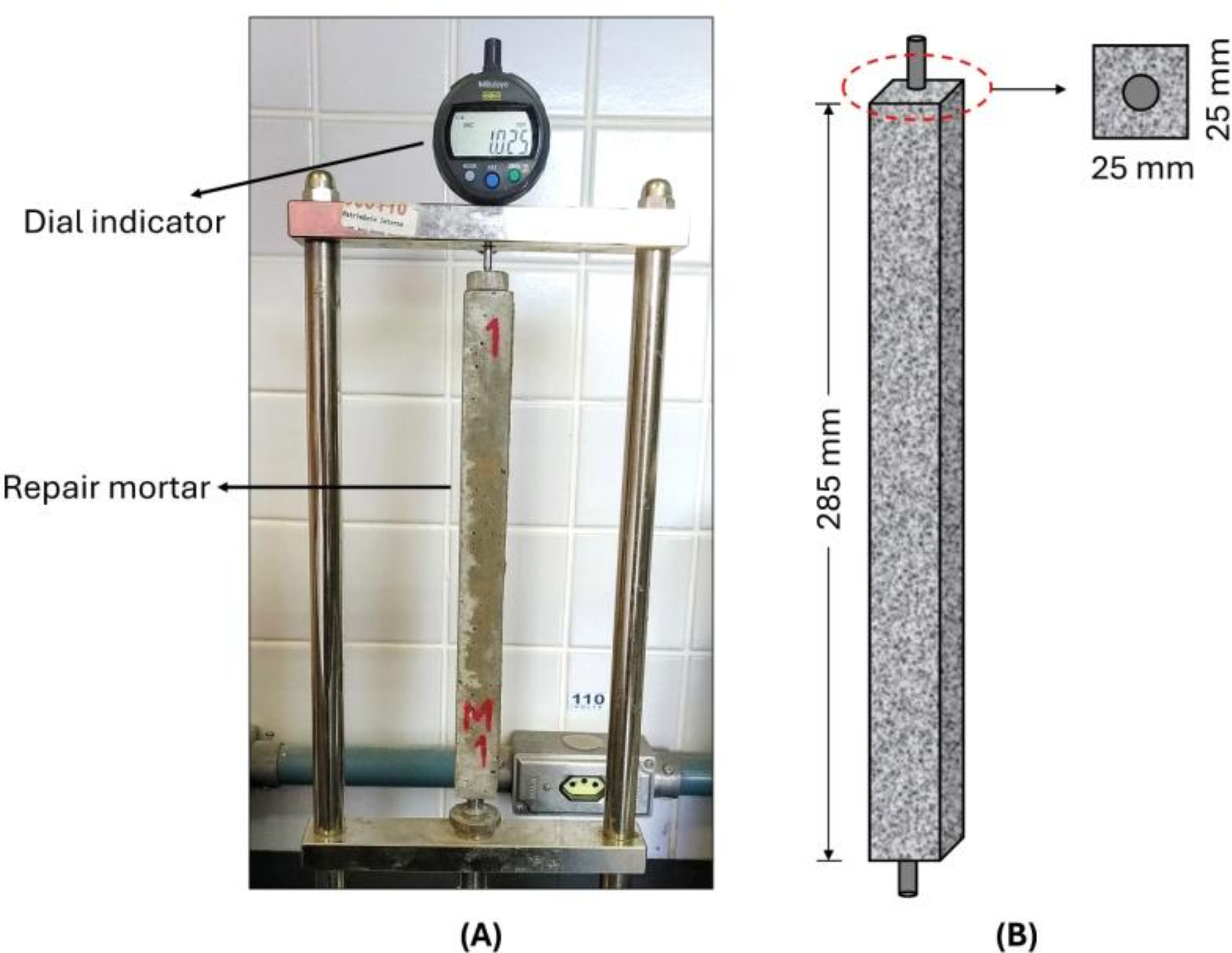

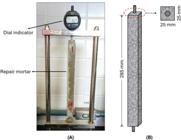

Dry shrinkage, weight loss, and CTE were evaluated on mortar prisms. Figure 7 shows the device and setup for these test measurements and the specimen dimensions.

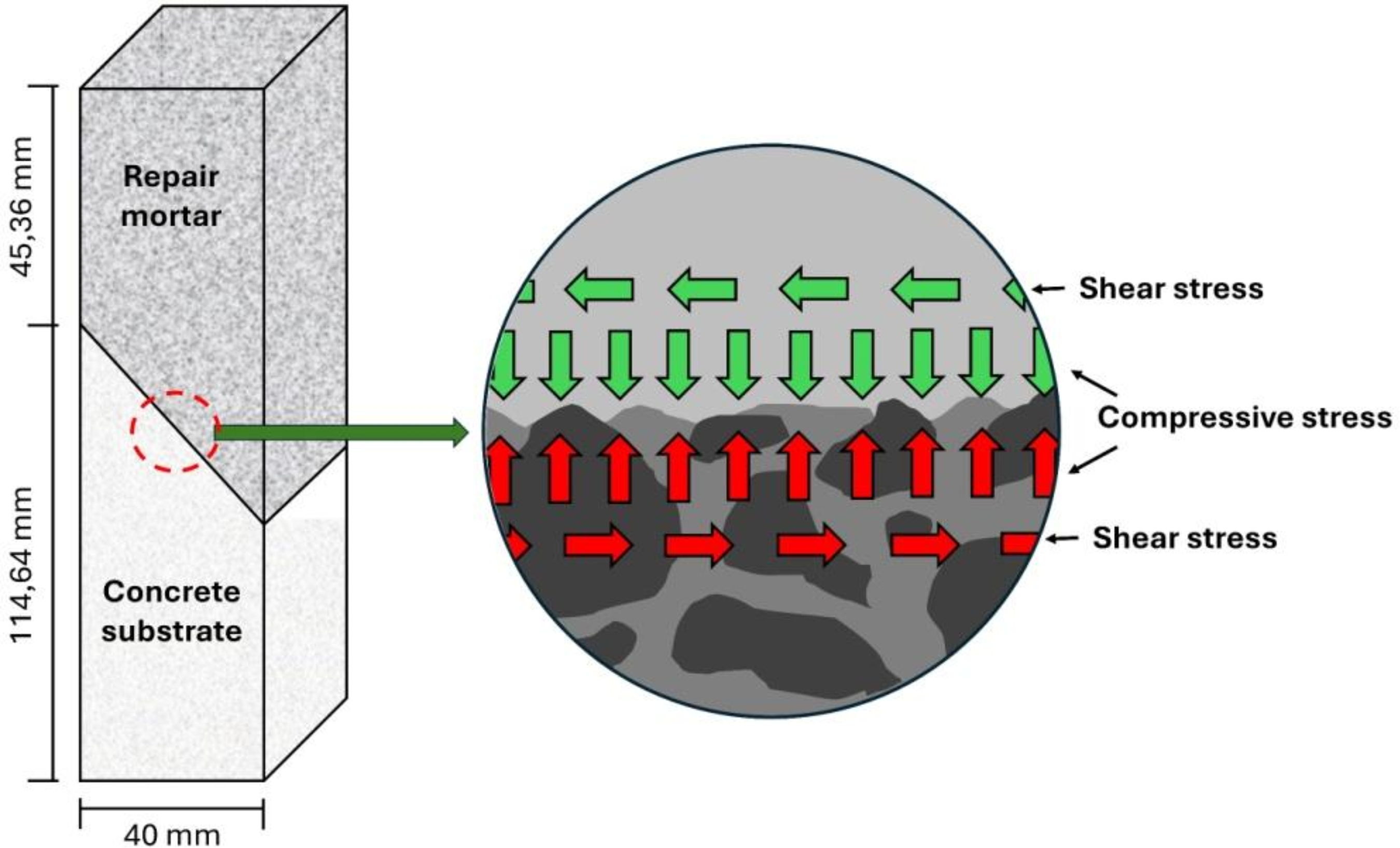

The oblique shear bond strength, also known as the slant shear test, was employed in analysing the repaired composite performance, according to C882 (ASTM, 2020a). Figure 8 shows the test setup and the stress action of the oblique shear methodology. This method was chosen due to its ability to simultaneously evaluate compression and shear forces, simulating the actual conditions of a repaired system (Qian et al., 2014). The bond strength was calculated using Equation 3.

Where:

Fss – oblique shear bond strength (MPa);

F – failure load (N); and

A – bond surface area (mm²).

The experiment was conducted with a loading rate of 50 N/s on a universal testing machine (EMIC, DL10.000).

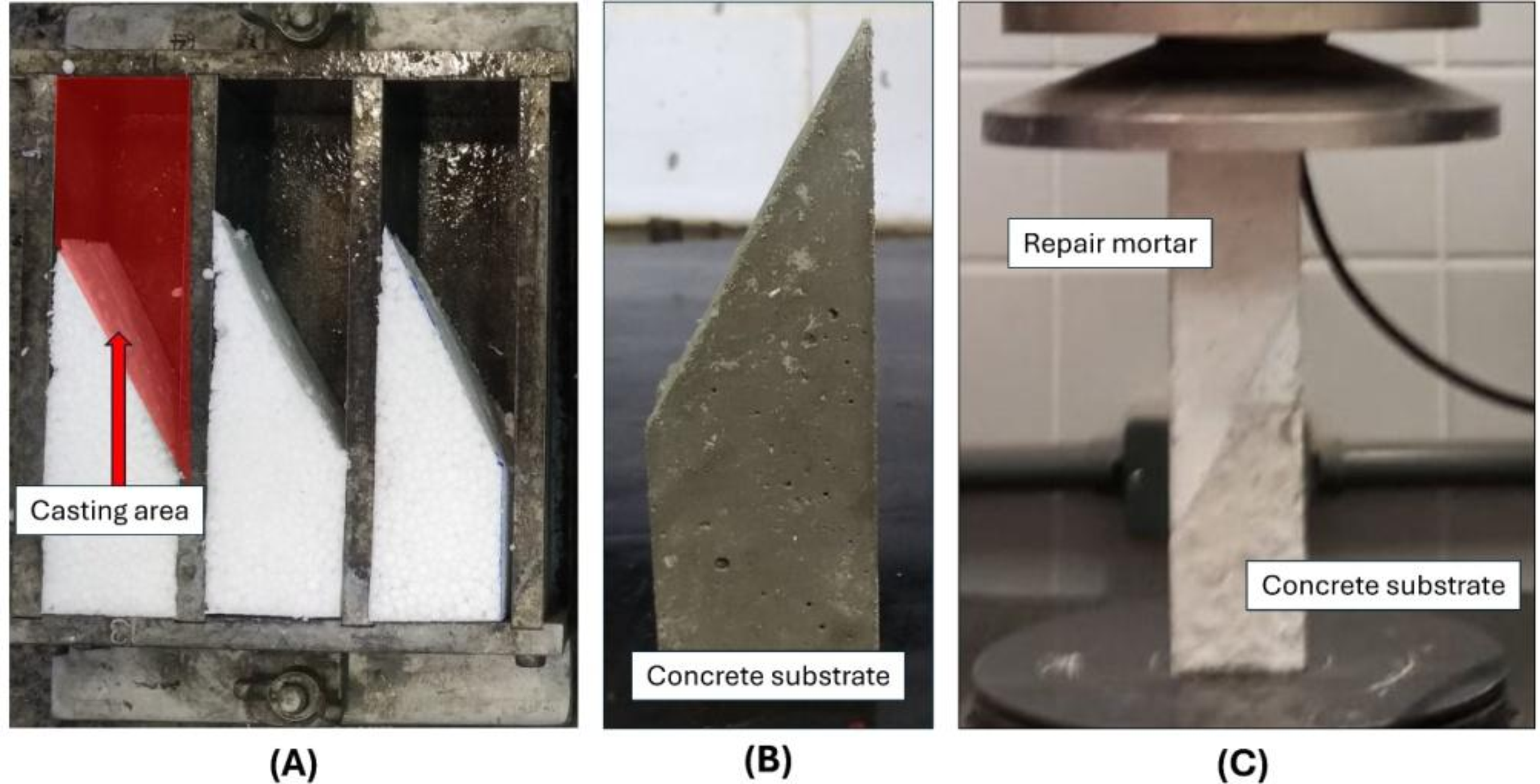

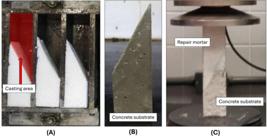

Polystyrene moulds embedded in metallic forms were used to cast the concrete substrate. After 24 hours of casting, the concrete samples were subjected to water curing in a lime-saturated solution. At 28 days, the samples were removed from the curing process, reconditioned in the moulds (saturated surface dry condition), and the repair mortar was cast. After 24 hours of casting, the substrate composite and repair were subjected to curing under the same conditions as the concrete until it reached 28 days of age. Figure 9 presents the casting of the substrate and repair system.

In the hardened state, the results were calculated as the mean of three samples per mix for the bond strength test and six for the dry shrinkage, weight loss, and CTE tests. The data were statistically analysed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test with a significance level of 0.05.

(A) Device, setup, and (B) sample dimensions used in the weight loss, dry shrinkage, and coefficient of thermal expansion test

Configuration and stress distribution in the interfacial transition zone between the concrete substrate and repair material in the oblique shear bond test

Casting of the Substrate and Repair System: (A) Mold Used; (B) Hardened Substrate; (C) Substrate-Repair Composite

A SEM analysis was conducted to understand the influence of nanoparticles on the evaluated properties at the microscopic level. Before the analysis, hydration was stopped in the samples. This process was carried out on fragments obtained from specimens cured in lime-saturated water for 28 days. The samples were immersed in isopropyl alcohol for 24 hours to remove water from the open pores due to the difference in density. They were then oven-dried at 40 °C until a constant mass was reached (Hoppe Filho et al., 2021).

The SEM analysis was performed with a TESCAN VEGA3 LMU scanning electron microscope, which features a 3 nm resolution, magnifications up to 300kX, and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The samples with stopped hydration were mounted on metallic stubs using graphite-based adhesive and coated with gold to enable image acquisition via the SEM technique.

Figure 10 presents a flowchart of the experimental programme, including the testing ages and the number of samples per mix.

Results e discussions

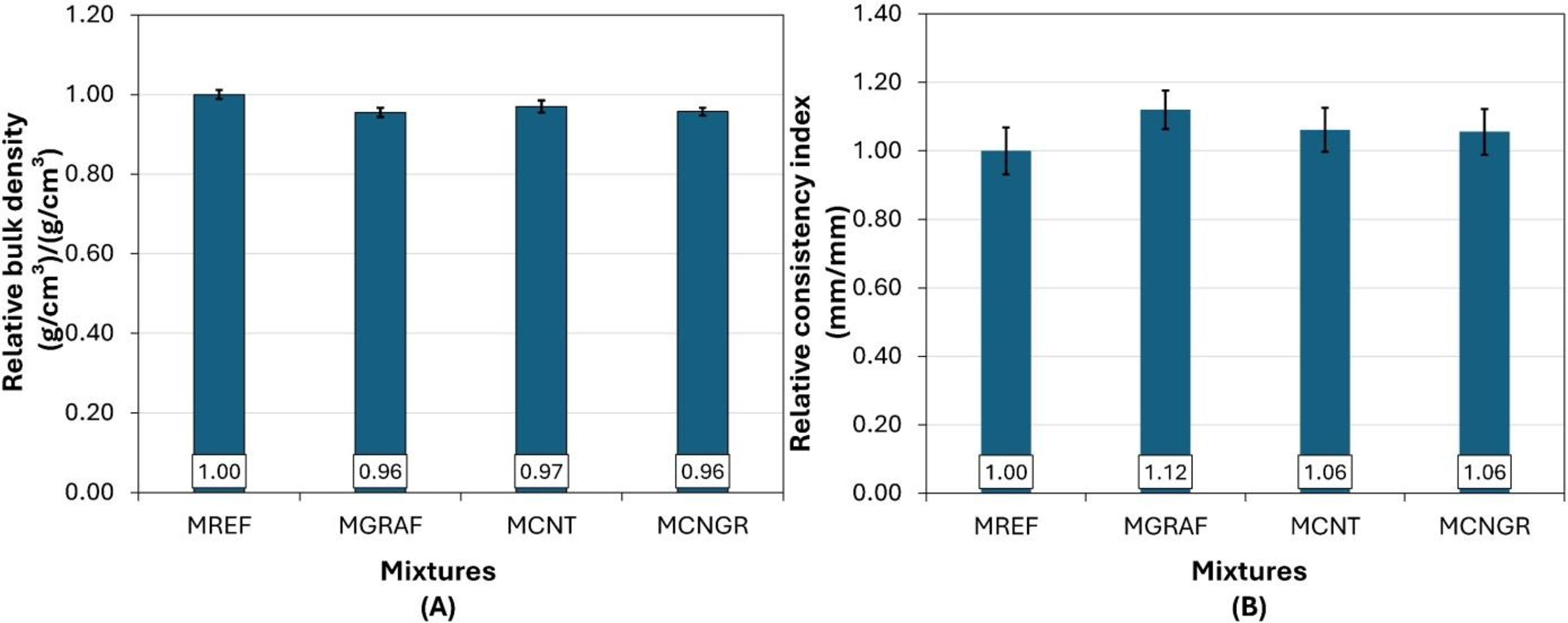

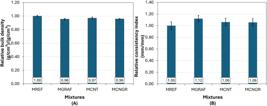

Figure 11 presents the relative results for the bulk density and consistency index, i.e., the ratio between the average value of the evaluated mixture ‘‘i’’ and the average value of the reference mixture (Bulk density.Mix-i/Bulk density.Ref and Consistency index.Mix-i/Consistency index.Ref). It is important to note that the reference mixture contains a lower admixture dosage (0.15%) than the other mixtures with nanoparticles (0.50%). As mentioned previously, the adoption of a 0.50% superplasticiser content was due to the concern of ensuring proper dispersion during the sonication process of these nanoparticles.

Fresh state results: (A) Relative bulk density and (B) Relative consistency index for cement repair mortars

Statistical analysis of the data indicated that, for bulk density, the MGRAF and MCNGR mixtures showed values significantly different from the MREF mixture. This behaviour is possibly due to graphene’s larger dimensions than MWCNT (see Figure 4). Furthermore, due to their morphology, graphene particles may have influenced the particle packing between cement particles, increasing the interparticle spaces and reducing this property associated with the high content of superplasticiser, which can potentially increase the air incorporation in the fresh material (Romano; Cincotto; Pileggi, 2018).

On the other hand, for the consistency index, only the MGRAF mixture exhibited significant changes in this property. Despite having a higher superplasticiser content (0.50%) than the reference mixture (0.15%), the mixtures containing MWCNT (MCNT and MCNGR) did not significantly increase the mortar consistency index. This behaviour may be attributed to the carbon nanotubes’ properties such as high specific surface area and aspect ratio, which increase the water demand for particle wetting, thereby reducing the amount of water available for particle lubrication and, consequently, the flowability.

Workability, defined as how easily a material can be handled, is critical to repair efficiency. It affects how the repair material is applied to the substrate and the quality of the repair-substrate interface. Mortars with low workability (i.e., low consistency) may fail to create adequate anchorage points on the substrate surface, thereby reducing adhesion (Costa; John, 2011; Costa; Cincotto; Pileggi, 2005; Kudlanvec Junior, 2017). Consequently, the selection of repair mortars should also consider their fresh-state properties, which can be adjusted using chemical additives.

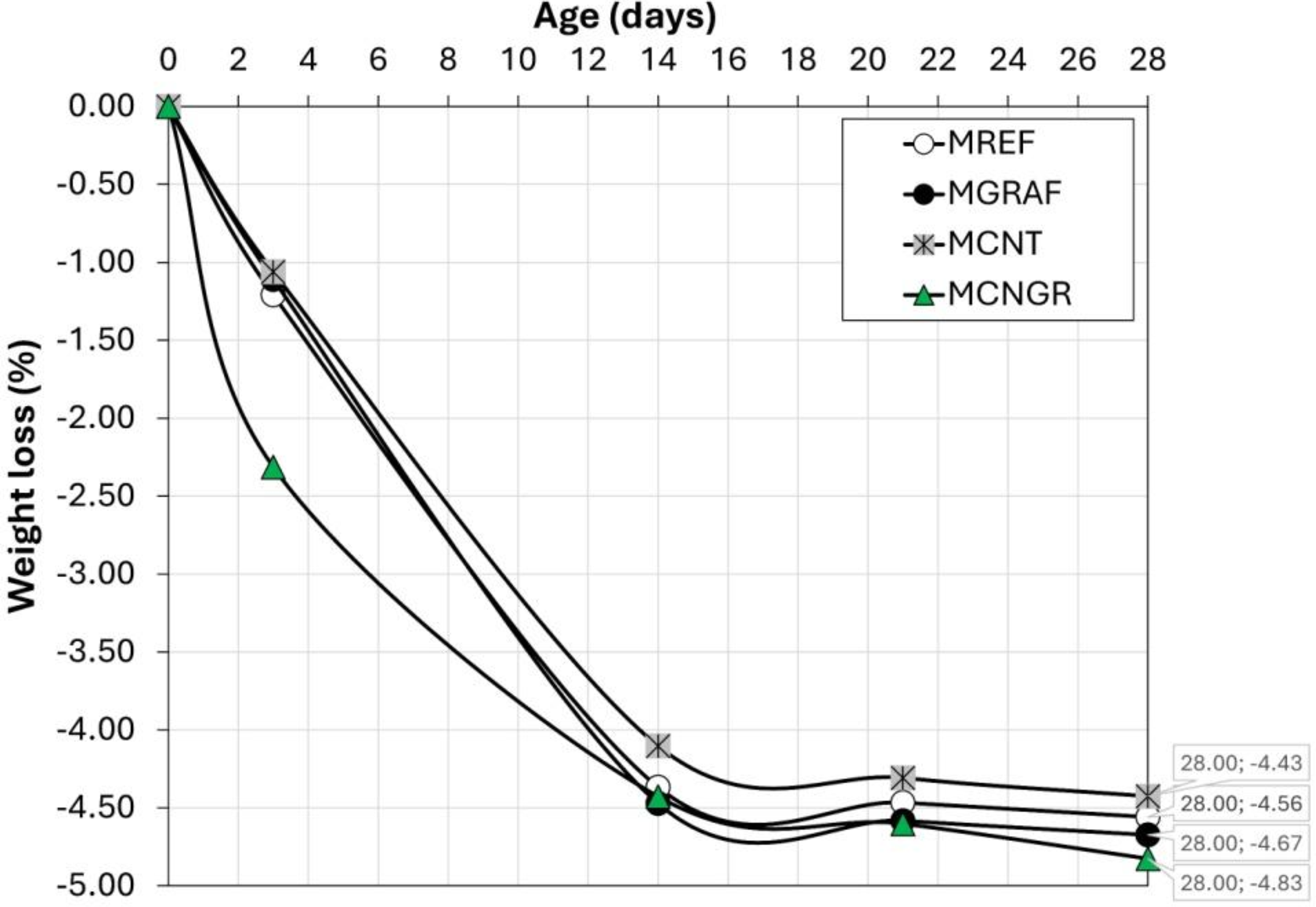

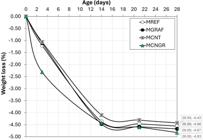

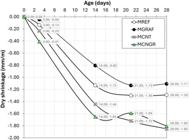

Dry shrinkage is a phenomenon that occurs in cementitious materials due to water evaporation in the environment with relative humidity below the saturation point. In the context of repair materials, the dimensional variation can compromise the repaired system due to stress on the ITZ between repair and substrate (Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022). Figure 12 shows the repair weight loss at different ages. The mortar weight loss is related to water loss from the pores due to drying or curing conditions. The mixture of MWCNT and graphene (MCNGR) increases weight loss at an early age. This behaviour may be associated with the greater available specific surface area, which enhances the nucleation effect for cement hydration reactions. Additionally, since carbon nanotube nanoparticles are hydrophobic, they can accelerate water movement and evaporation at an early age. These effects were not observed in the other mixtures, possibly due to the lower content of added nanoparticles. Although, at 28 days, all the mixtures showed statistically similar behaviour in the 4.43% to 4.83% range.

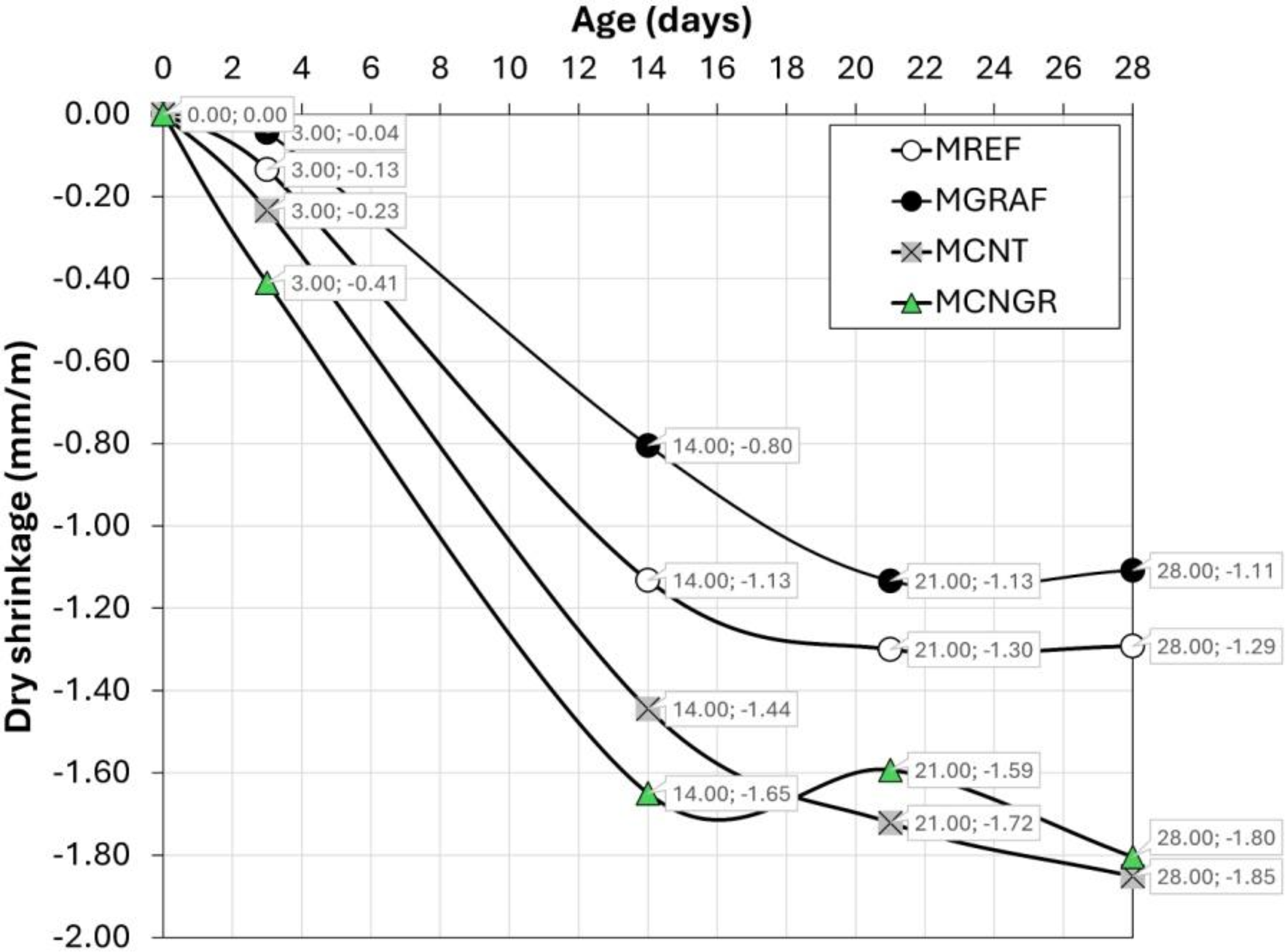

Figure 13 presents the dry shrinkage of cement mortars at 03, 14, 21, and 28 days. At 28 days, mortars with carbon nanotubes exhibited higher dimensional instability, reaching 1.80 mm/m and 1.85 mm/m, while MREF and MGRAF showed lower values of 1.29 mm/m and 1.11 mm/m, respectively. These results showed that adding graphene can increase the dimensional stability of cement mortar.

Zhao et al. (2020) observed similar behaviour. It is likely that, due to their micrometric dimensions, graphene particles acted as micro-reinforcements within the matrix, reducing dry shrinkage effects. Ikhlasi, Gholampour and Vincent (2023) observed that PRG reduced dry shrinkage by creating a denser microstructure and absorbing excess water through its 2D surface. Al-Fakih et al. (2024) reported a 10.7% dry shrinkage reduction with 0.3 wt% graphene oxide nanocomposite, improving compressive strength and reducing cracking in the cement matrix.

On the other hand, carbon nanotubes, due to their nanometric dimensions, may act in pore refinement when well dispersed, leading to an increase in capillary pressure and, consequently, an increase in the matrix’s dimensional variation (Souza et al., 2017). Excessive nanomaterial dosages can compromise dimensional stability by increasing water demand and promoting particle agglomeration, leading to capillary pore formation and facilitating water migration to the surrounding environment.

Despite these variations, all mortars tested in this study remained within the C928 (ASTM, 2020b) limit of 0.15% shrinkage after curing, with MREF, MGRAF, MCNT, and MCNGR exhibiting values of 0.09%, 0.07%, 0.12%, and 0.13%, respectively. Therefore, all the results obtained are within the limits recommended by this standard.

Adding carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly graphene particles, helps enhance dimensional stability, reduce shrinkage-induced cracking, and improve the durability of repair materials. However, achieving satisfactory performance requires careful control of nanomaterial dosage and uniform dispersion to avoid excessive water demand and unintended porosity. Field applications must also consider environmental conditions to select the most suitable curing method. Furthermore, appropriate strategies should be adopted to manage dimensional variations, such as adjusting curing methods, incorporating expansion joints, or avoiding repair configurations with a high length-to-thickness ratio (ACI, 2014).

While this study observed an increase in dry shrinkage with carbon nanotube incorporation, other studies have reported the opposite effect (Li et al., 2015; Hawreen; Bogas, 2019; Tafesse; Kim, 2019). This underscores the importance of evaluating carbon nanotube dosage and intrinsic properties to optimise their application in cementitious composites.

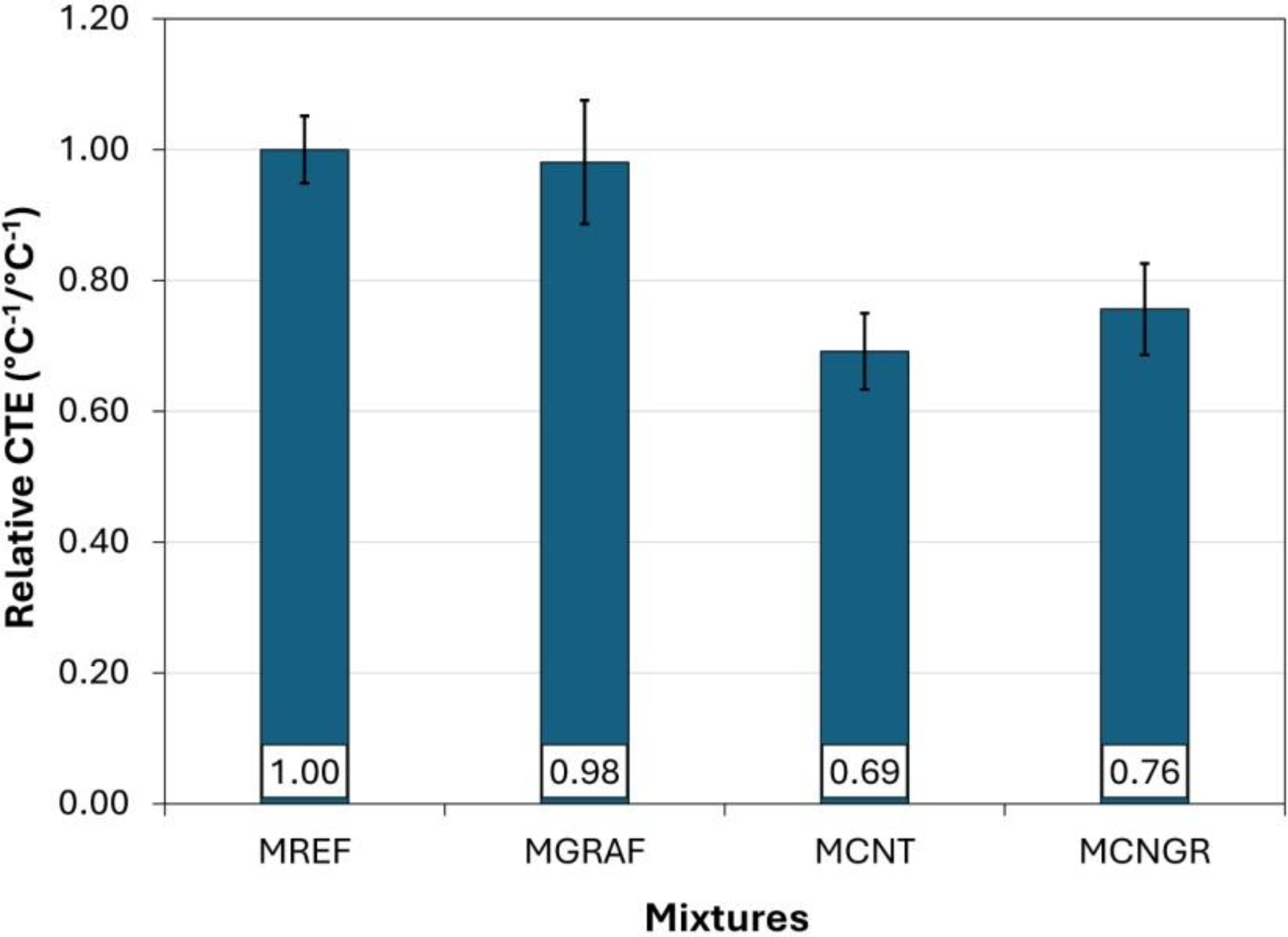

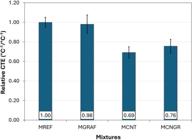

The CTE is a material property related to dimensional variations due to thermal changes (Zhou; Shu; Huang, 2014; Araújo, 2022; Medeiros; Daschevi; Araújo, 2022). Figure 14 shows the relative results of repair mortars CTE (CTE.Mix-i/CTE.Ref). The incorporation of graphene alone (MGRAF) did not affect this property. However, mixtures with carbon nanotubes, namely MCNT and MCNGR, significantly reduced this coefficient. As noted by Kwon, Berber and Tománek (2004), this behaviour is attributed to the response of carbon nanotubes when exposed to temperatures between 0-400 K (-273.15 to 126.85 °C). Unlike other materials, carbon nanotube filaments experience both volumetric and axial shrinkage with increasing temperature, which explains the results obtained in this study once the temperature evaluation was between 23 °C and 100 °C.

These results suggest that incorporating carbon nanotubes, especially in applications exposed to temperatures up to 100 °C, can enhance the dimensional stability of repaired systems, reducing the risk of cracking and system failure in the ITZ. The CTE is critical in repair materials due to thermal stresses arising from the restrictions imposed by the bond between the repair material and the substrate (Enzell; Tollsten, 2017). High CTE values can lead to cracking and deterioration of concrete structures submitted to high temperature fluctuations such as dam spillways, sun-exposed slabs, concrete pavements, bridges, and airport runways.

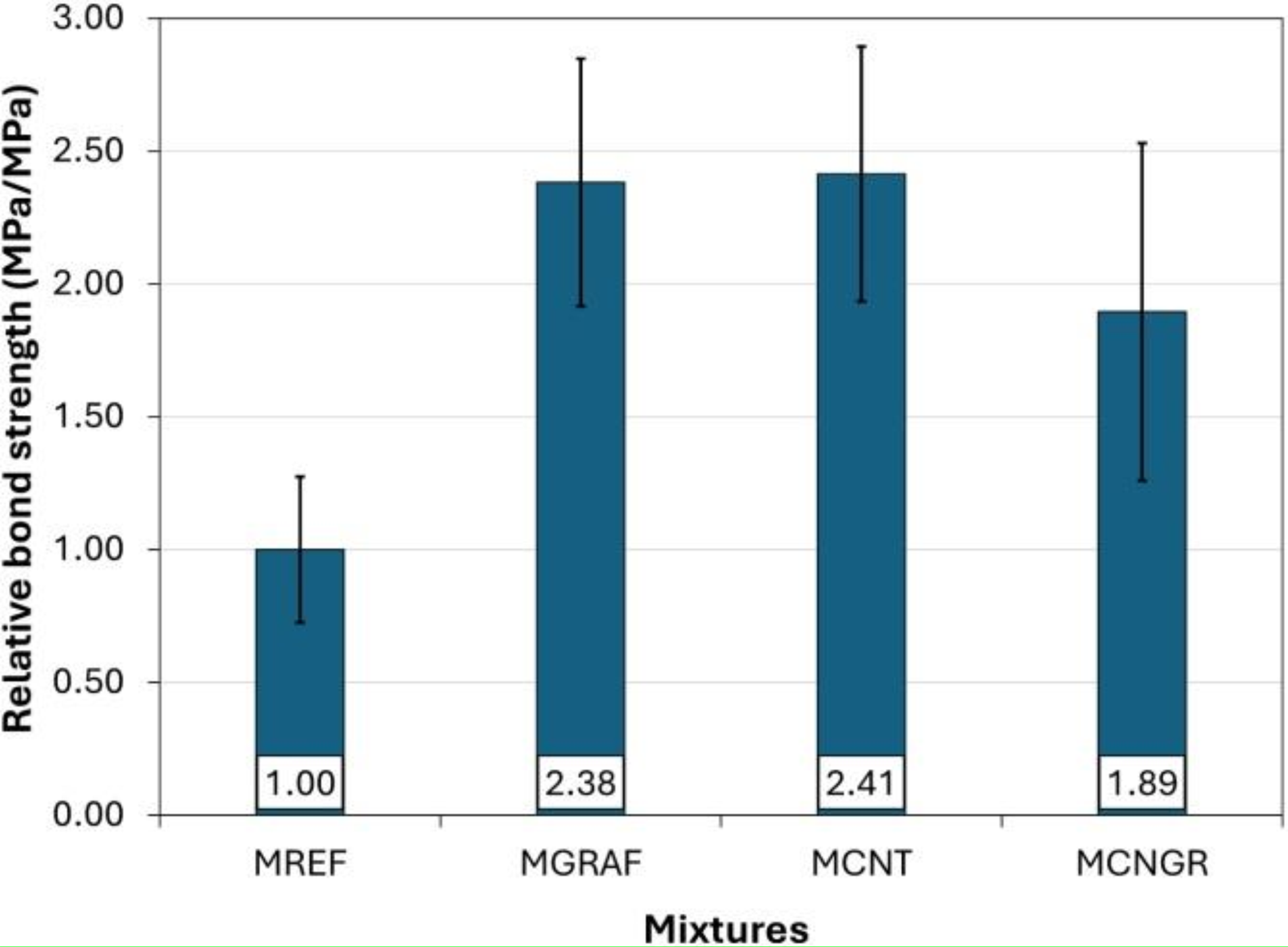

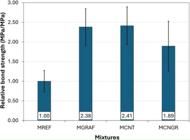

Figure 15 presents the relative shear bond strength results (Bond strength.Mix-i/Bond strength.Ref). The results indicate that incorporating nanomaterials enhances the bond strength values with the concrete substrate for all mixtures, with the reference mortar showing an oblique shear bond strength of 3.61 MPa. Nanoparticles can act as nucleation sites for the hydration reactions of Portland cement, contributing to the agglomeration of crystals within the cementitious matrix (Song et al., 2017). Additionally, the higher superplasticiser contents in mixtures containing nanomaterials (0.50%) may have promoted a better dispersion of the binder particles, promoting the formation of additional adherence points at the transition with the concrete substrate. Superplasticisers also enable the dispersed cement particles to penetrate the pores at the contact zone with the concrete substrate, where they precipitate and react, further enhancing bond strength (Reese et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021). Gao et al. (2023) highlighted that graphene oxide can promote the growth of hydration products and increase the matrix density at the ITZ of different materials, such as between the repair layer and the substrate, effectively improving the bond strength.

Nanoparticle incorporation is a promising strategy for increasing the performance of repair materials due to their role as nucleation sites for hydration reactions, especially those with structural functions that require high bond strength. Although this aspect is beyond the scope of the present study, it is essential to consider the influence of substrate surface treatment and roughness, as different methods can significantly alter the characteristics of the transition zone (Júlio; Branco; Silva, 2004; Yazdi et al., 2020).

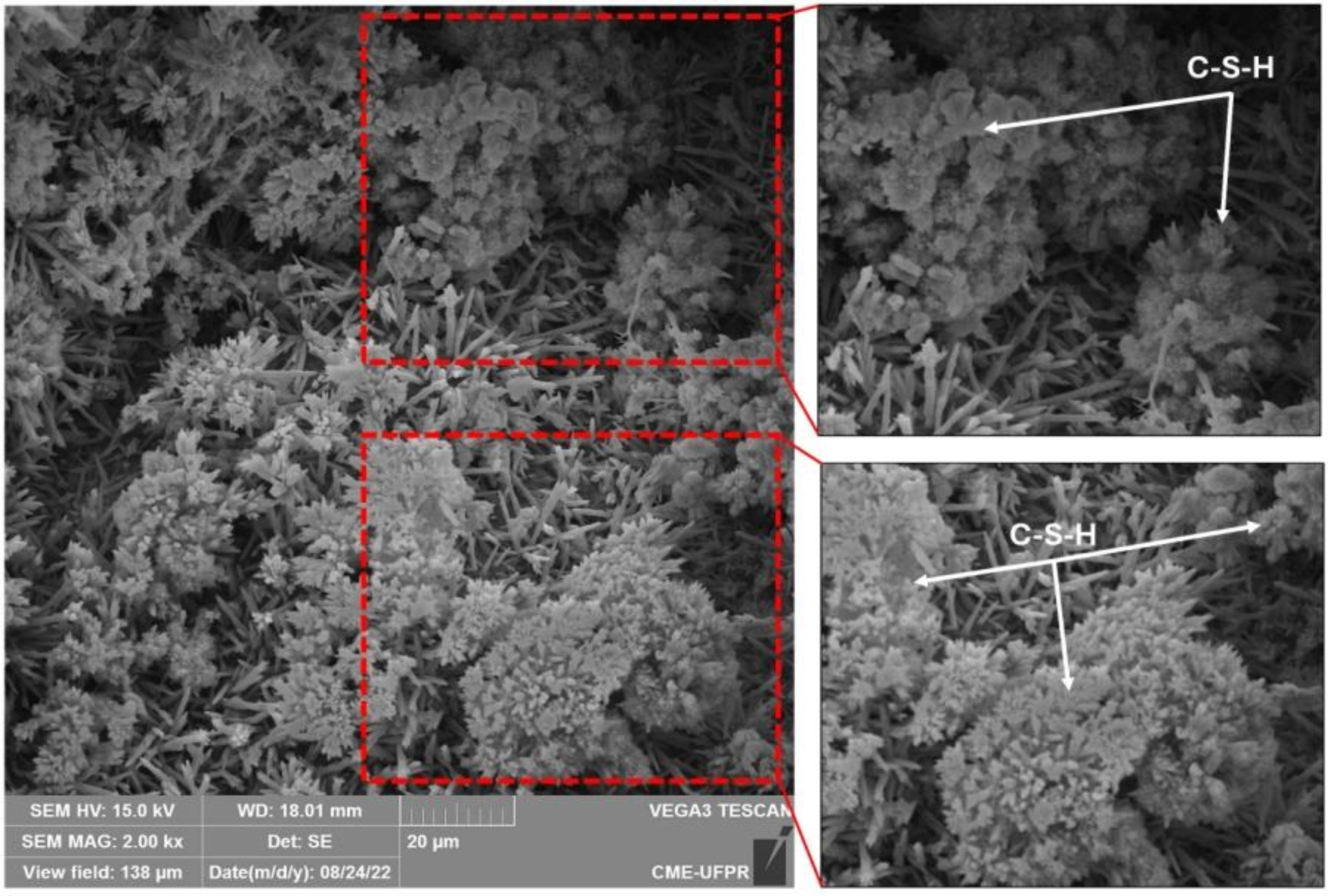

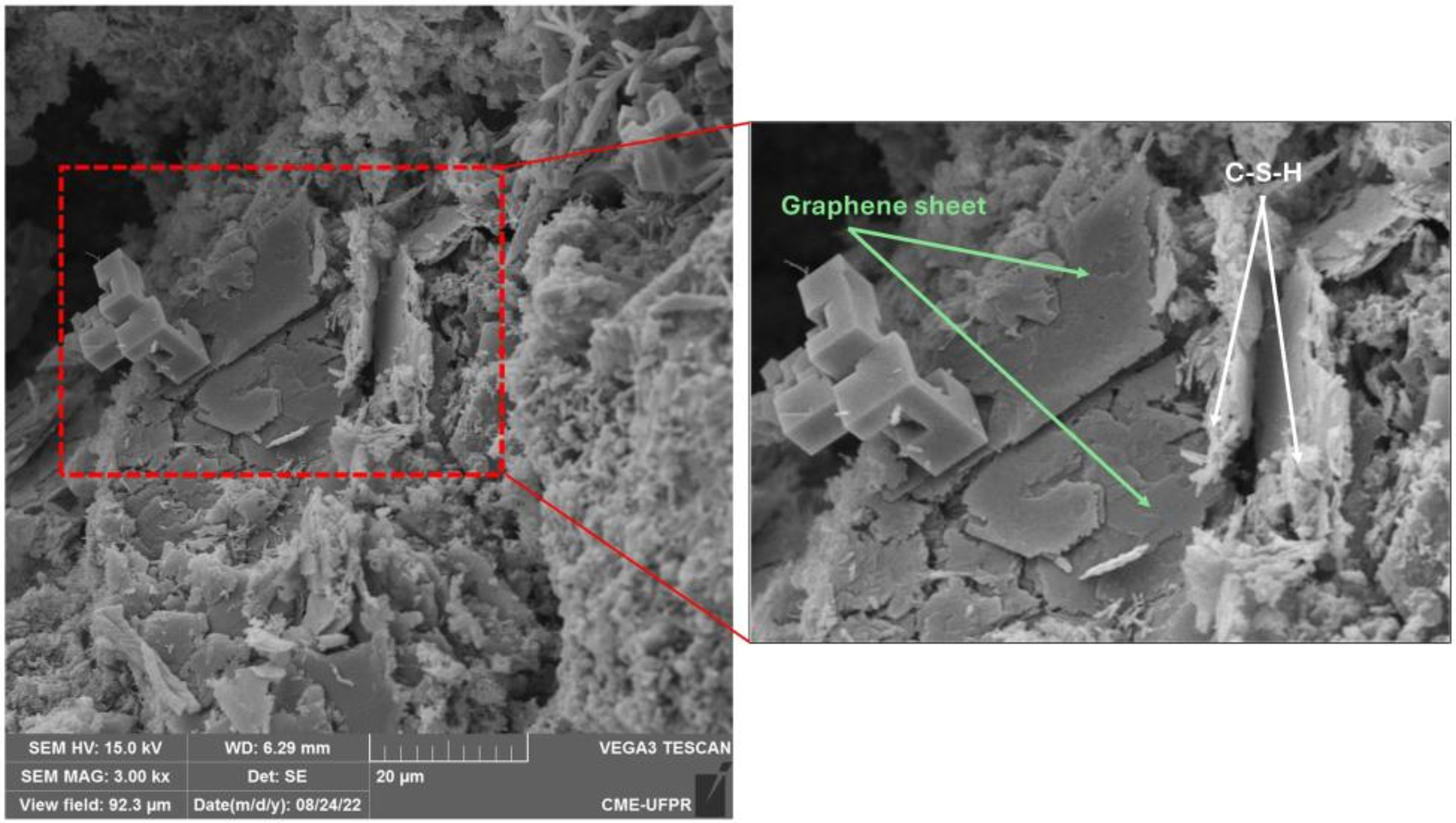

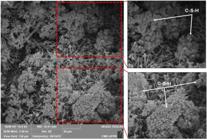

The microstructural SEM analyses were conducted on the MREF, MGRAF, and MCNT mixtures. Due to experimental limitations, the study of the MCNGR mixture samples was not feasible. Figure 16 presents the microstructure of the MREF mixture. A matrix with the formation of floc-like C-S-H phases can be observed. Figure 17 shows the SEM image of the MGRAF mixture, where the graphene particles embedded in the cementitious matrix can be seen. Crystals are present on their surface and edges, possibly due to the nucleation effect of these particles, as previously pointed out.

This condition supports the earlier hypothesis regarding the effect of graphene particles on enhancing the dimensional stability of the mortars. As these particles are embedded in the matrix, they may contribute to reinforcing the cementitious structure, reducing the dimensional variations.

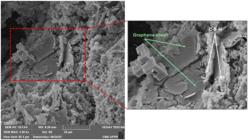

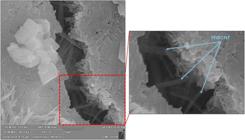

Finally, Figure 18 shows the SEM image of the MCNT mixture, where fibrillar materials can be observed crossing a crack and being randomly dispersed. This indicates that the sonication dispersion method, combined with the presence of a superplasticiser, effectively disperses these particles. This also aligns with the behaviour of carbon nanotube particles about drying shrinkage. When well dispersed, these particles act as nucleation sites, increasing the rate of hydration reactions due to their high specific surface area, increasing the matrix refinement, which increases capillary pressure, causing dimensional instability.

The enhanced performance of repair materials with nanomaterials can significantly extend the service life of structures. This increased durability reduces the frequency of repair interventions, thereby minimising the overall consumption of additional materials for future repairs and contributing to long-term sustainability (Singh; Sharma; Kapoor, 2024).

However, the practical application of these nanomaterials is closely tied to their rational use (given their hydrophobic behaviour and associated cost), determining an appropriate dosage is crucial for ensuring the desired performance in structural or non-structural applications. It is important to note that using a material with high mechanical performance is unnecessary if the repair does not demand it. Therefore, a preliminary study is essential to assess the repair’s specific performance requirements and determine the most appropriate nanomaterial type and dosage, considering environmental conditions such as relative humidity, temperature, substrate condition, and repair orientation (horizontal, vertical, inclined).

This comprehensive evaluation links the enhanced performance to the specific needs of repairs while also helping to control costs. As highlighted by Vafaeva and Zegait (2024), the successful integration of carbon nanotube, and by extension, other types of nanomaterials, depends on a collaborative effort among material scientists, engineers, and industry professionals to meet specific application requirements and drive advancements in construction.

Incorporating graphene into repair mortars (MGRAF) improved essential properties, such as bond strength, dimensional stability, and reduction in the CTE. In contrast, mortars containing carbon nanotubes (MCNT and MCNGR) did not show significant enhancements across all the evaluated properties. However, improvements in bond strength and a reduction in CTE were observed. Table 7 summarises the performance of the compositions in this study regarding each property evaluated.

It should be noted that this study was conducted using a fixed concentration of 0.02% by weight of cement for both nanomaterials, thereby limiting the assessment of the effects of dosage variation on performance. The graphene-based (MGRAF) mix exhibited the best mechanical performance for the evaluated properties among the compositions tested. However, further research exploring a range of nanoparticle concentrations is required to determine the optimal dosage for different performance criteria. Furthermore, future studies should assess the effects of varying dosages under various curing conditions, given that repair materials in practical applications may be exposed to diverse environmental environments.

Figure 18 – SEM image of MCNT (0.2 wt% MWCNT)

Conclusions

This study provided valuable insights into the influence of carbon-based nanoparticles, specifically graphene and carbon nanotubes, on dimensional stability, bond strength, and microstructure of repair mortars. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the practical implications of nanomaterials-based repairing cementitious systems. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

in the fresh state, carbon nanotube mortars (MCNT and MCNGR), even with a higher superplasticiser content (0.50%) than the reference mixture (0.15%), did not change the workability. This behaviour is associated with the high specific surface area and aspect ratio, which demand a high amount of water to involve the particles and then reduce this property;

-

at 28 days, mortars containing carbon nanotubes (MCNT and MCNGR) exhibited increased shrinkage of 33-44% compared to the reference mixture. In contrast, the graphene-based mortar (MGRAF) reduced shrinkage by 22%. This effect is likely due to pore refinement in carbon nanotube mixtures (which increases capillary pressure and shrinkage) and the reinforcing effect of graphene particles (reducing shrinkage);

-

the presence of graphene particles in the mortars did not affect the CTE. However, mixtures containing carbon nanotubes (MCNT and MCNGR) exhibited reductions in this property, aligning with the known thermal behaviour of this nanomaterial in temperatures up to 126 °C;

-

all nanomaterial mixtures significantly improved oblique shear bond strength compared to the reference mortar. This enhancement is attributed to the nanoparticles acting as nucleation sites during the hydration, increasing adhesion points between the repair material and the substrate. Additionally, using a high superplasticiser content, necessary for adequate nanoparticle dispersion via sonication, may have contributed to improved cement particle dispersion, improving the dispersion of cement particles; and

-

SEM analysis confirmed that graphene particles acted as a nucleation site for hydration products, with crystal formations observed on their surfaces and edges. MWCNTs were well dispersed within the matrix, reinforcing the observed effects on dimensional stability and bond strength.

These findings highlight that incorporating carbon-based nanomaterials improves dimensional stability and bond strength. However, since this study used fixed nanoparticle content, further research is needed to explore a broader range of nanomaterial dosages and their interactions with different curing conditions to optimise performance across various environmental exposures. In repair applications, these nanomaterials can either increase or decrease shrinkage depending on particle size, specific surface area, and dispersion within the cementitious matrix. Understanding these interactions is crucial for tailoring nanomaterial-based repair mortars to specific practical applications, ultimately contributing to more durable and reliable repair solutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Laboratory of Materials and Structures (LaME), the Post-Graduate Program in Civil Engineering (PPGEC), the Civil Engineering Studies Center (CESEC) at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), the Multiuser Photonics Laboratory (FOTON) at UTFPR, the Araucária Foundation, the National Water and Sanitation Agency (ANA), and the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) for the physical and financial support provided for the development of this study, as well as the material suppliers Cimentos Itambé and MC-Bauchemie.

References

- AL-FAKIH, A. et al. Hybrid effects of graphene oxide-zeolitic imidazolate framework-67 (GO@ZIF-67) nanocomposite on mechanical, thermal, and microstructure properties of cement mortar. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 97, 110803, 2024.

- AMERICAN CONCRETE INSTITUTE. 546-3R: guide to materials selection for concrete repair. Farmington Hills, 2014.

- AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR TESTING AND MATERIALS. C882: standard test method for bond strength of epoxy-resin systems used with concrete by slant shear. West Conshohocken, 2020a.

- AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR TESTING AND MATERIALS. C928: standard specification for packaged, dry, rapid-hardening cementitious materials for concrete repairs. West Conshohocken, 2020b.

- ARAÚJO, E. C. Eficiência de argamassa de reparo com nano materiais: propriedades mecânicas, durabilidade e microestrutura. Curitiba, 2022. 146 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia Civil) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2022.

- ARAÚJO, E. C. et al. Influência da densidade de empacotamento de partículas na resistividade elétrica de pastas compostas por silica ativa. In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE PATOLOGIA DAS CONSTRUÇÕES, 6., Fortaleza, 2024. Anais […] Fortaleza, 2024.

- ARAÚJO, E. C. et al. Influência da incorporação de grafeno e sílica ativa nas propriedades físicas e de durabilidade de argamassas cimentícias. In: SEMINÁRIO BAIANO DE DURABILIDADE E DESEMPENHO DAS CONSTRUÇÕES, 4., Ilhéus, 2022. Anais […] Ilhéus: UESC, 2022.

- ARAÚJO, E. C.; MACIOSKI, G.; MEDEIROS, M. H. F. Concrete surface electrical resistivity: effects of sample size, geometry, probe spacing and SCMs. Construction and Building Materials, v. 324, 126659, 2022.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 13276: argamassa para assentamento e revestimento de paredes e tetos: determinação do índice de consistência. Rio de Janeiro, 2016.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 13278: argamassa para assentamento e revestimento de paredes e tetos: determinação da densidade de massa e do teor de ar incorporado. Rio de Janeiro, 2005a.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 15261: argamassa para assentamento e revestimento de paredes e tetos: determinação da variação dimensional (retração ou expansão linear). Rio de Janeiro, 2005b.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 16697: cimento Portland: requisitos. Rio de Janeiro, 2018a.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 5739: concreto: ensaio de compressão de corpos de prova cilíndricos. Rio de Janeiro, 2018b.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 7211: agregados para concreto: requisitos. Rio de Janeiro, 2022.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 9779: argamassa e concreto endurecidos: determinação da absorção de água por capilaridade. Rio de Janeiro, 2013.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NM 23: cimento Portland e outros materiais em pó: determinação da massa específica. Rio de Janeiro, 2000a.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NM 248: agregados: determinação da composição granulométrica. Rio de Janeiro, 2001.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NM 30: agregado miúdo: determinação da absorção de água. Rio de Janeiro, 2000b.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NM 45: agregados: determinação da massa unitária e do volume de vazios. Rio de Janeiro, 2006.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NM 52: agregado miúdo: determinação de massa específica e massa específica aparente. Rio de Janeiro, 2002.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NM 53: agregado graúdo: determinação de massa específica, massa específica aparente e absorção de água. Rio de Janeiro, 2009.

- ATIF, R.; INAM, F. Reasons and remedies for the agglomeration of multilayered graphene and carbon nanotubes in polymers. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology, v. 7, p. 1174-1196, 2016.

- BENTZ, D. P. et al. Influence of substrate moisture state and roughness on interface microstructure and bond strength: slant shear vs. pull-off testing. Cement and Concrete Composites, v. 87, p. 63-72, 2018.

- BHEEL, N. et al. Synergetic effect of multiwalled carbon nanotubes on mechanical and deformation properties of engineered cementitious composites: RSM modelling and optimization. Diamond & Related Materials, v. 147, 111299, 2024.

- COSTA, E. B. C.; JOHN, V. M. Aderência substrato-matriz cimentícia: estado da arte. In: SIMPÓSIO BRASILEIRO DE TECNOLOGIA DE ARGAMASSAS, 9., Belo Horizonte, 2011. Anais […] Belo Horizonte, 2011.

- COSTA, M. R. M. M.; CINCOTTO, M. A.; PILEGGI, R. G. Análise comparativa de argamassas colantes de mercado e o seu comportamento reológico. In: SIMPÓSIO BRASILEIRO DE TECNOLOGIA DAS ARGAMASSAS, 6., Florianópolis, 2005. Anais […] Florianópolis, 2005.

- CHEN, S. J. et al. Predicting the influence of ultrasonication energy on the reinforcing efficiency of carbon nanotubes. Carbon, v. 77, p. 1-10, 2014.

- CHEN, Y-H. et al. Preparation and properties of graphene/carbon nanotube hybrid reinforced mortar composites. Magazine of Concrete Research, v. 71, n. 8, p. 395-407, 2019.

- EMMONS, P. H.; VAYSBURD, A. M. System concept in design and construction of durable concrete repairs. Construction and Building Materials, v. 10, n. 1, p. 69-75, 1996.

- ENZELL, J.; TOLLSTEN, M. Thermal cracking of a concrete arch dam due to seasonal temperature variations. Stockholm, 2017. Master of Science Degree Project – Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, 2017.

- GAO, Y. et al. Fabrication of graphene oxide/fiber reinforced Polymer cement mortar with remarkable repair and bonding properties. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, v. 24, p. 9413-9433, 2023.

- GHOLAMPOUR, A. et al. Performance of concrete containing pristine graphene-treated recycled concrete aggregates. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, v. 199, 107266, 2023.

- GHOLAMPOUR, A.; SOFI, M.; TANG, Y. Effect of recycled aggregate treatment methods by pristine graphene on mechanical and durability properties of concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research, v. 76, n. 14, p. 769-782, 2024.

- HASSAN, K. E.; BROOKS, J. J.; AL-ALAWI, L. Compatibility of repair mortars with concrete in a hot-dry environment. Cement and Concrete Composites, v. 23, n. 1, p. 93-101, 2001.

- HAWREEN, A.; BOGAS, J. A. Creep, shrinkage and mechanical properties of concrete reinforced with different types of carbon nanotubes. Construction and Building Materials, v. 198, p. 70-81, 2019.

- HERBST, M. H.; MACÊDO, M. I. F.; ROCCO, A. M. Tecnologia dos nanotubos de carbono: Tendências e perspectivas de uma área multidisciplinar. Química Nova, v. 27, n. 6, p. 986-992, 2004.

- HOPPE FILHO, J. et al. Evaluation of sample drying methods to determine the apparent porosity and estimation of degree of hydration of Portland cement pastes. Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation, v. 6, n. 2021.

- IKHLASI, Z.; GHOLAMPOUR, A.; VINCENT, T. Drying shrinkage of waste-based concrete reinforced with pristine graphene (PRG) nanomaterial. Materials Today: Proceedings, 23 May, 2023.

- ISFAHANI, F. T.; LI, W.; REDAELLI, E. Dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and its effect on the properties of cement composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, v. 74, p. 154-163, 2016.

- JING, G. et al. Improving the cracking resistance of mortar by reduced graphene oxide. Construction and Building Materials, v. 310, 125150, 2021.

- JÚLIO, E. N. B. S.; BRANCO, F. A. B.; SILVA, V. D. Concrete-to-concrete bond strength. Influence of the roughness of the substrate surface. Construction and Building Materials, v. 18, n. 9, pp. 675-681, 2004.

- KIAMAHALLEH, M. V. et al Incorporation of reduced graphene oxide in waste-based concrete including lead smelter slag and recycled coarse aggregate. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 88, 109221, 2024.

- KOCH et al NACE international impact report: international measures of prevention, application, and economics of corrosion technologies study. Houston, 2016.

- KONSTA-GDOUTOS, M. S.; METAXA, Z. S.; SHAH, S. P. Highly dispersed carbon nanotube reinforced cement based materials. Cement and Concrete Research, v. 40, p. 1052-1059, 2010.

- KORAYEM, A. H. et al. A review of dispersion of nanoparticles in cementitious matrices: nanoparticle geometry perspective. Construction and Building Materials, v. 153, p. 346-357, 2017.

- KUDLANVEC JUNIOR, V. L. Aderência de argamassas de reparo em substrato de concreto com ênfase no comportamento reológico Curitiba, 2017. 181 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia de Construção Civil) – Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2017.

- KWON, Y.; BERBER, S.; TOMÁNEK, D. Thermal contraction of carbon fullerenes and nanotubes. Physical Review Letters, v. 92, n. 1, 2004.

- LI, W. et al. Investigation on the mechanical properties of a cement-based material containing carbon nanotube under drying and freeze-thaw conditions. Materials, v. 8, n. 12, pp. 8780-8792, 2015.

- LIEW, K. M.; KAI, M. F.; ZHANG, L. W. Carbon nanotube reinforced cementitious composites: An overview. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, v. 91, p. 301-323, 2016.

- LIU, J.; LI, Q.; XU, S. Reinforcing mechanism of graphene and graphene oxide sheets on cement-based materials. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, v. 31, n. 4, 2019.

- LU, T.; LI, Z.; HUANG, H. Restraining effect of aggregates on autogenous shrinkage in cement mortar and concrete. Construction and Building Materials, v. 289, 123166, 2021.

- MANGAT, P. S.; O’FLAHERTY, F. J. Influence of elastic modulus on stress redistribution and cracking in repair patches. Cement and Concrete Research, v. 30 n. 1, p. 125-136, 2000.

- MANGAT, P. S.; O’FLAHERTY, F. J. Long-term performance of high-stiffness repairs in highway structures. Magazine of Concrete Research, v. 51, n. 5, p. 325-339, 1999.

- MARCONDES, C. G. N. et al. Carbon nanotubes in Portland cement concrete: Influence of dispersion on mechanical properties and water absorption. Revista ALCONPAT, v. 5, n. 2, 2015.

- MARCONDES, C. G. N.; MEDEIROS, M. H. F. Analyzing the dispersion of carbon nanotubes solution for use in Portland cement concrete. Revista ALCONPAT, v. 6, n. 2, p. 84-100, 2016.

- MEDEIROS, M. H. F. et al. Compósitos de cimento Portland com adição de nanotubos de carbono (NTC): Propriedades no estado fresco e resistência à compressão. Revista Matéria, p. 127-144, 2015.

- MEDEIROS, M. H. F. et al. Improvement of repair mortars using multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Construction Materials, v. 172, n. 2, p. 71-84, 2019.

- MEDEIROS, M. H. F.; DASCHEVI, P. A.; ARAÚJO, E. C. Reparo localizado para estruturas de concreto armado: erros, acertos e reflexões. Concreto & Construções, v. 106, p. 28-33, 2022.

- MEDEIROS, M. H. F.; HELENE, P.; SELMO, S. Influence of EVA and acrylate polymers on some mechanical properties of cementitious repair mortars. Construction and Building Materials, v. 23, n. 7, p. 2527-2533, 2009.

- MEHTA, P. K.; MONTEIRO, P. J. M. Concreto: microestrutura, propriedades e materiais. 3. ed. São Paulo: Ibracon, 2008.

- MENDES, T. M.; MEDEIROS, M. H. F. Effect of carbon nanotubes on Portland cement matrices. IBRACON Structures and Materials Journal, v. 16, n. 5, e16508, 2023.

- 44with cellulose ether. Construction and Building Materials, v. 34, p. 218-225, 2012.

- PAGANI, R. N.; KOVALESKI, J. L.; RESENDE, L. M. Methodi Ordinatio: a proposed methodology to select and rank relevant scientific papers encompassing the impact factor, number of citation, and year of publication. Scientometrics, v. 105, p. 2109-2135, 2015.

- PARVEEN, S.; RANA, S.; FANGUEIRO, R. A review on nanomaterial dispersion, microstructure, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotube and nanofiber reinforced cementitious composites. Journal of Nanomaterials, v. 2013, 710175, 2013.

- QIAN, J. et al. A method for assessing bond performance of cement-based repair materials. Construction and Building Materials, v. 68, p. 307-313, 2014.

- QURESHI, T. S.; PANESAR, D. K. A comparison of graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide and pure graphene: early age properties of cement composites. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SUSTAINABLE MATERIALS, SYSTEMS AND STRUCTURES, Rovinj, 2019. Prooceedings […] Rovinj, 2019.

- REESE, J. et al. Influence of type of superplasticizer and cement composition on the adhesive bonding between aged and fresh concrete. Construction and Building Materials, v. 48, p. 717-724, 2013.

- REMENCHE, I. R. et al. Formation of incipient anodes in localized mortar repairs with the addition of rice husk silica. Revista ALCONPAT, v. 14, n. 3, 2024.

- RILEM. TC 116-PCD Permeability of Concrete as a Criterion of its Durability. Materials and Structures, v. 32, p. 174-179, 1999.

- ROMANO, R. C. O.; CINCOTTO, M. A.; PILEGGI, R. G. Incorporação de ar em materiais cimentícios: uma nova abordagem para o desenvolvimento de argamassas de revestimento. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 18, n. 2, p. 289-308, abr./jun. 2018.

- SALEEM, H.; ZAIDI, S. J.; ALNUAIMI, N. A. Recent advancements in the nanomaterial application in concrete and its ecological impact. Materials, v. 14, n. 21, 2021.

- SANCHÉZ, M. et al. External treatments for the preventive repair of existing constructions: a review. Construction and Building Materials, v. 193, p. 435-452, 2018.

- SILVA JUNIOR, J. Z. R.; HELENE, P. BT/PCC/92: argamassa de reparo. São Paulo: Escola Politécnica da Universidade de São Paulo, 2001.

- SINGH, N.; SHARMA, V.; KAPOOR, K. Graphene in construction: enhancing concrete and mortar properties for a sustainable future. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, v. 9, 428, 2024.

- SONG, X. et al Multi-walled carbon nanotube reinforced mortar-aggregate interfacial properties. Construction and Building Materials, v. 133, p. 57-64, 2017.

- SOUZA, D. J. et al. Repair mortars incorporating multiwalled carbon nanotubes: shrinkage and sodium sulfate attack. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, v. 29, 2017.

- SU, N. et al. Assessment of effective patching material for concrete bridge deck: a review. Construction and Building Materials, v. 293, 123520, 2021.

- TAFESSE, M.; KIM, H. The role of carbon nanotube on hydration kinetics and shrinkage of cement composite. Composites Part B, v. 169, p. 55-64, 2019.

- TOKLU, K.; ŞIMŞEK, O.; ARUNTAŞ, H. Y. Investigation of the usability of high-performance fiber-reinforced cement composites containing high-volume fly ash and nanomaterials as repair mortar. Journal of the Australian Ceramic Society, v. 55, p. 789-797, 2019.

- TRIGO, A. P. M.; CONCEIÇÃO, R. V.; LIBORIO, J. B. L. A técnica de dopagem no tratamento da zona de interface: ligações entre o concreto novo e velho. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 10, n. 1, p. 167-176, ja./mar. 2010.

- VAFAEVA, K. M.; ZEGAIT, R. Carbon nanotubes: revolutionizing construction materials for a sustainable future: a review. Research on Engineering Structures and Materials, v. 10, n. 2, p. 559-621, 2024.

- WANG, X. et al. Bond of nanoinclusions reinforced concrete with old concrete: Strength, reinforcing mechanisms and prediction model. Construction and Building Materials, v. 283, 122741, 2021.

- WEI, X-X. et al. Enhancement in durability and performance for cement-based materials through tailored water-based graphene nanofluid additives. Construction and Building Materials, v. 457, 139455, 2024.

- WON, M. Improvements of testing procedures for concrete coefficient of thermal expansion. Journal of the Transportation Research Board, v. 1919, n. 1, 2005.

- WOSNIACK, L. M. et al. Resistividade elétrica do concreto pelo ensaio de migração de cloretos: comparação com o método dos quatro eletrodos. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 21, n. 3, p. 321-340, jul./set. 2021.

- WU, L. et al. Autogenous shrinkage of high performance concrete: a review. Construction and Building Materials, v. 149, p. 62-75, 2017.

- YAZDI, M. A. et al. Bond strength between concrete and repair mortar and its relation with concrete removal techniques and substrate composition. Construction and Building Materials, v. 230, 116900, 2020.

- YUNPENG, L. et al. Compatibility of repair materials with substrate low-modulus cement and asphalt mortar (CA mortar). Construction and Building Materials, v. 126, p. 304-312, 2016.

- ZARBIN, A. J. G.; OLIVEIRA, M. M. Nanoestruturas de carbono (nanotubos, grafeno): Quo Vadis? Química Nova, v. 36, n. 10, 2013.

- ZHAO, Y. et al. Study of mechanical properties and early-stage deformation properties of graphene-modified cement-based materials. Construction and Building Materials, v. 257, 119498, 2020.

- ZHOU, C.; SHU, X.; HUANG, B. Predicting concrete coefficient of thermal expansion with an improved micromechanical model. Construction and Building Materials, v. 68, p. 10-16, 2014.

- ZHOU, J.; YE, G.; BREUGEL, K. V. Cement hydration and microstructure in concrete repairs with cementitious repair materials. Construction and Building Materials, v. 112, p. 765-772, 2016.

Edited by

-

Editor:

Enedir Ghisi

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

19 May 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

13 Jan 2025 -

Accepted

14 Mar 2025

Dimensional stability of repair mortars with carbon-based nanoparticles

Dimensional stability of repair mortars with carbon-based nanoparticles

Note: requirement according to NBR 7211 (

Note: requirement according to NBR 7211 (