Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating socioeconomic impact and reignited the debate on vaccination and the hesitancy to vaccinate children and young people. This study sought to understand the reasons related to the behaviour of parents in vaccinating their children aged 5 to 17 years against COVID-19 with currently available vaccines; this study was conducted from June 2022 to July 2022. This work was a cross-sectional, descriptive, and observational study with a qualitative‒quantitative approach. The individuals in the sample had a mean age of 12 years, were mostly public school students, did not have COVID-19, and had a complete vaccination card. Parents who had vaccinated their children reported understanding that vaccination supports immunity, whereas those who had not vaccinated their children did not trust the COVID-19 vaccine. The ability to recognize fake vaccinerelated information was greater among parents who vaccinated their children (72.4%) than among those who did not (38.0%; p<0.05). The behaviours involved in vaccinating against COVID-19 are multifactorial, and factors such as children’s age, lack of confidence in the efficiency and safety of vaccines, parents’ age, ability to use information appropriately for health decision-making and low ability to recognize fake vaccine-related information are involved in these behaviours.

Keywords:

Vaccination Hesitancy Vaccine; COVID-19.

INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was subsequently termed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was first detected in Wuhan, China, and the spread of this virus was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020 (Li et al., 2020; WHO, 2022).

The socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic have been devastating and uncountable, and in some areas of the world, they have not yet been satisfactorily ascertained or have been underestimated (Moscadelli et al., 2020). By June 9, 2022, the pandemic had affected more than 530 million individuals, leading to the deaths of approximately 6 million three hundred thousand people worldwide (WHO, 2022).

Governments and institutions worldwide have faced challenging and difficult situations because of the risks of managing and communicating information on infection rates and the necessary restriction measures that have been imposed to reduce the spread of the virus (Moscadelli et al., 2020). At the same time, the scientific community began an unprecedented, intense effort to obtain sufficient information to begin understanding SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, which paved the way for the development of vaccines with technologies and speed never before seen in the academic-corporate environment (Moscadelli et al., 2020).

The development of vaccines has been considered key for reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease, reducing the need for new quarantine measures (OPAS, 2021). However, large-scale acceptance by the population is necessary (Francis et al., 2022) for at least 80% of the eligible population to be vaccinated and herd immunity to be achieved (Randolph, Barreiro, 2020). To this end, the population under 18 years of age also needs to be reached by vaccination campaigns because vaccines have been available and approved by regulatory agencies and the WHO since 2021 (OPAS, 2022).

Surprisingly, many studies from countries where vaccines have been widely available have indicated that the intention to become vaccinated against COVID-19 has steadily declined, with increasing levels of vaccine hesitancy since the first wave of the pandemic (Lavoie et al., 2022).

Considering the development of vaccines for people under 18 years of age, many studies have evaluated vaccine hesitancy among parents of children and young people to predict the causes of hesitancy and, consequently, to take public health measures that could mitigate this problem (Bagateli et al., 2021; Alí et al., 2022; Di Giuseppe et al., 2022; Galanis et al., 2022).

Lavoie and collaborators (2022) assessed vaccination resistance among adults in a Canadian national study of more than 15,000 respondents between April 2020 and May 2021 and reported that parents of individuals under the age of eighteen had greater vaccine hesitancy than others did.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis covering a total population of 317,055 parents from 44 studies on the vaccine hesitancy of children and youth between March 2020 and September 2021, Galanis and collaborators (2022) reported that approximately 23% of parents intended to not vaccinate their children, and another 25.8% still did not know if they would vaccinate, which suggests difficulty in achieving herd immunity in this age group.

We can highlight several factors related to this tendency to not vaccinate children: concerns about the effectiveness and safety of vaccines and lack of recommendation by primary care physicians/ paediatricians (Di Giuseppe et al., 2022), the belief that children are not at risk of contracting COVID-19 (Alí et al., 2022), the number of children, low education levels, and low family income (Bagateli et al., 2021; Alí et al., 2022), among others.

Another aspect related to vaccine hesitancy seems to be the inability of some people to recognize so-called fake news, which seems to be related to the lack of health literacy and highlights the motivation and competence of individuals to access, understand, evaluate and use information to make decisions about their health (Montagni et al., 2021, Cubizolles et al., 2023).

Considering the Brazilian context, a study conducted with health care professionals from four cities in four Brazilian states and the Federal District highlighted their perceptions regarding childhood vaccination hesitancy against COVID-19. Fear emerged as one of the cited reasons, linked to key determinants of hesitancy: complacency, trust, and misinformation. Additionally, vaccine misinformation was identified as a critical factor associated with, among other issues, fake news about the vaccine and the phenomenon of infodemia and disinformation. The crucial role of primary health care professionals was emphasized as significant in increasing vaccination coverage, given their credibility with the population and their close connection to local communities (Souto et al., 2024).

Additionally, the political situation in Brazil during the pandemic should be taken into account, with the politicization of vaccines emerging as a novel challenge to vaccination programs. The results from Seara-Morais, Avelino-Silva, Couto & Avelino-Silva (2023) indicate that political ideologies have shaped COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy across Brazilian municipalities, affecting communities inequitably.

However, the authors are not aware of a study that has evaluated the reasons that lead parents to not vaccinate their children with the vaccines already available and the vaccination campaign in progress and with a qualitative and quantitative approach.

Therefore, through a qualitative‒quantitative approach, the present study aimed to understand the reasons related to the choice of parents to vaccinate their children aged 5 to 17 years against COVID-19 when vaccines are already available.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The population of this study was obtained from the database of a population-based cross-sectional study conducted among school-aged individuals, called the School Survey, which took place in 2020 and aimed to assess the frequency of COVID-19 infection in this population in Espírito Santo state (Maciel et al., 2021). The data of children and young people between 5 and 17 years of age in this database were cross-referenced with the data of vaccinated children in the official government database “Vaccine and Trust” (https://www.vacinaeconfia.es.gov.br/cidadaos/), which gathers all the information about vaccination against COVID-19. The data were collected in June 2022.

Thus, two groups were obtained: parents of children who were vaccinated (VACCINATED group) and parents of children who were not vaccinated (UNVACCINATED group).

Study design

This work was a cross-sectional, descriptive and observational study conducted from June to July 2022 with a qualitative‒quantitative approach to analyse the choice of parents to vaccinate their children.

Parents whose children were identified as vaccinated were considered to belong to the group of parents with positive behaviour in relation to vaccination. Those parents whose children were not identified as vaccinated were considered to be in the group of parents with negative behaviour in relation to vaccination.

At least one of the parents or legal guardians of these children and young people was interviewed by telephone to collect socioeconomic and cultural data, and the tendency to be influenced by fake news and health literacy was assessed.

A smaller group of parents from both groups was also invited to participate in the qualitative part of this study for the elaboration of the collective subject discourse (CSD).

Before the parents were interviewed, a free and informed consent form in Google Forms format was sent by a text message (SMS). Parents were instructed to read and “sign” the Google form, click on “agree” and print a version for themselves. Upon receiving the form, the researchers printed it out and then deleted it.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria and sampling

All parents or guardians of children and young people aged between 5 and 17 years who were in the database of the School Survey were included and excluded if they did not answer the calls after four attempts on different days, if they did not agree to participate in this study or if they did not sign the informed consent form.

Among the 2,149 (two thousand one hundred forty-nine) children and adolescents aged 5 (five) to 17 (seventeen) years who participated in the School Survey, 1,800 (one thousand eight hundred) had a record of vaccination against COVID-19 in the official government database, 324 (three hundred twentyfour) had a record of only 1 (one) dose, and 349 (three hundred forty-nine) were not identified in the database.

All parents or guardians were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in this study; 1,640 did not answer the telephone calls, and 99 did not agree to participate in this study or did not electronically sign the informed consent form and were therefore excluded. Thus, a sample of 410 (four hundred and ten) children and adolescents aged between 5 (five) and 17 (seventeen) years was selected for this study.

Socioeconomic and cultural data

The following socioeconomic and cultural data were obtained through telephone interviews: age, sex, family income, place of residence, education level, education level of the spouse or partner, whether the individual had already been vaccinated against COVID-19 (complete schedule), whether the individual had been vaccinated against influenza, whether the child had a complete vaccination card, and whether the parent believed in the effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines for children and youth.

Fake news detection

The ability to detect fake news related to COVID-19 was assessed according to Montagni et al. (2021), with adaptations. For each of the statements below (Table I), parents or guardians were asked to indicate whether the statement was true, false or if they could not tell.

For each correct answer, one point was assigned. For incorrect answers and “I do not know” answers, no score was assigned. Based on the total score, a score of 0 to 10 points was assigned, with higher scores corresponding to a better ability to detect fake news. After the scores were obtained, the 50th percentile (P50) was plotted, and two categories were generated: low ability to detect fake news (scores below P50) and high ability to detect fake news (scores equal to or greater than P50).

Health literacy assessment

The health literacy assessment was conducted according to a questionnaire (Table II) developed by the French Public Health Agency (Santé Publique France, 2020). For each of the statements below, respondents were asked to assign a score from 0 to 3 (4-point Likert scale), with 0 indicating that the respondent completely disagreed with the statement and 3 indicating that the respondent completely agreed. A score from 0 to 15 was created based on the score obtained, and higher scores indicated better levels of health literacy. Two categories were generated: poor health literacy (scores from 0 to 9) and good health literacy (scores from 10 to 15).

Collective subject discourse (CSD)

The data (testimonials) from this stage were collected before the interviews to obtain socioeconomic and cultural data; fake news detection capacity and health literacy were assessed for a subsample of 30 parents in the positive group in relation to vaccination and 30 parents in the negative group in relation to vaccination through open-ended semistructured interviews. The first 30 interviewees from each group were invited.

We used a script consisting of questions that addressed the perceptions of the subjects about the vaccination behaviour and the reasons associated with it:

-

1. Why did you vaccinate (not vaccinate) your child?

-

2. Where did you obtain information about or where did your considerations/beliefs about the vaccine come from, and what prompted you to vaccinate (not vaccinate) your child? Explain this, please.

With the permission of the interviewee, the testimony was recorded on a digital recorder for later literal transcription.

Elaboration of the CSD

For the transcription and first editing of the interviews, some care was taken regarding the fidelity of what was stated and the respondents’ anonymity, such as the maintenance of repeated words and language vice and the omission of the participants’ proper names.

Whenever possible, we chose to generate orthographically correct records of the speeches, except for situations that escaped the lexicon of the standard language or suppressed syllables and/or initial and final phonemes of words, as recommended by Araújo (2001) for the transcription and editing of interviews in qualitative research.

The oral testimonies resulting from the interviews, after transcription, involved floating reading, one of the preliminary stages of the process of analysing the empirical material in qualitative research. Floating reading allowed us to delimit the answers to each of the questions formulated, regardless of the exact moment in which the thoughts and perceptions of the subjects were expressed during the interview (Bardin, 1977).

The statements were then tabulated and organized according to the CSD analysis technique, which consists of a sequence of methodologically defined operations: 1) selection of key expressions of each statement or answer given to a question; 2) identification of the central ideas of each of the key expressions; and 3) meeting of the key expressions, referring to similar or complementary central ideas, resulting in a core set of discourse or discourse synthesis, written in the first person of the discourse, which is the CSD itself (Sales, Souza, John, 2007; Lefèvre, Lefèvre, 2003).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used, including the numbers and frequencies of qualitative variables and the means ± standard deviations of quantitative variables, stratified into vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. One-way ANOVA (Tukey’s post hoc test) for quantitative variables and the chi-square test for qualitative variables were used to compare groups and subgroups, with a significance level of 5% (P<0.05). GraphPad Prism 8.2.1 was used for statistical analysis.

In relation to qualitative research, the statements were analysed according to the CSD technique to develop discourses in the first person who represented the “collective subject” related to the central ideas identified in the statements.

In view of the adoption of multiple methodologies and phenomena, given the different evaluations aimed at obtaining a broad view of the results and that these were not restricted to a single perspective on the same problem for information analysis, the concept of data triangulation was used.

Ethical aspects

All the work was carried out within the ethical norms for research involving human beings and was previously approved by the Ethics and Research in Human Beings Committee (Research Ethics Committee/ UVV #5.513.826/2022).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Percentage of vaccinated individuals

Among the interviewed sample, the majority (N=283; 69.3%) of the children and adolescents who participated in this research were vaccinated. The unvaccinated subjects comprised 30.7% (N=126) of the sample.

However, our response rate was 19.1% of the total number of individuals in the database used. This rate is similar to that reported in other studies (Ansolabehere, Schaffner, 2014; Dal Grande et al., 2016), and because the pandemic is known to have reduced survey response rates (Krieger et al., 2023), this rate can be considered adequate. However, when the response rate was analysed separately between the groups of parents who vaccinated and those who did not vaccinate their children, a greater response rate was observed among the latter group (36.1%) than among the former (15.8%). This discrepancy may have led to the overestimation of the number of unvaccinated children.

Socioeconomic and cultural data

Children’s profile

Table III shows that the distribution by sex was similar in the sample studied. The mean age was 12 years, with a predominant age range between 12 and 17 years; additionally, the participants were mostly public school students who did not have COVID-19 and had a complete vaccination card.

Additionally, in the group of parents who did not vaccinate their children, both the average age and the frequency of children in the younger age group were lower than those in the total sample and the group of parents who vaccinated their children (in this group, age and frequency increased in the older age group).

Female sex and age between 36 (thirty-six) and 50 (fifty) years predominated among the interviewees, with an average age of 42 (forty-two) years (Table IV).

Socioeconomic and demographic data of parents of children and adolescents who had or had not been vaccinated against COVID-19

Parents’ profile

The parents who did not vaccinate their children were more likely to be younger and have younger children than parents in the general sample and parents who vaccinated their children.

Most parents were married, with balanced schooling between those who had completed higher education (49.4%) and those who had completed primary or secondary school (47.7%).

The most common family income was up to three times the minimum wage, with the metropolitan region as the main place of residence, and most had two or more children. These variables did not differ between groups.

The data in Table IV may explain, at least in part, the greater frequency of vaccinated children in the study population. A higher level of education, reflected in a level of education equal to or higher than completed high school (with approximately 50% of parents having completed higher education), may help explain the overall percentage of almost 70% of children and adolescents who were vaccinated because the level of vaccination has been correlated with the socioeconomic conditions of the family (Allan, Adetifa, Abbas, 2021; García-Toledano et al., 2021). However, the multifactorial characteristics of vaccination hesitancy cannot be ignored. Currently, the literature presents conflicting data concerning the relationship between education and vaccination behaviour, with studies also showing no influence of the level of education (Matos, Tavares, Couto, 2024).

Another relevant factor seems to be the age of the parents. Parents who did not vaccinate their children were more likely to be younger than 35 years old and also had a lower average age. Skitarelić and collaborators (2022) also reported greater positivity regarding the vaccination of children among older guardians. This population tends to be less gullible about antivaccination media because older people tend to have opinions based on their life experiences, whereas younger people are still formulating their convictions.

Parents’ profile - vaccination behaviour

Regarding the vaccination behaviour of parents, Table V shows that among the total population and parents who vaccinated their children, most were fully vaccinated or were vaccinated against influenza and trusted the vaccine against COVID-19. Furthermore, the frequency of responses in these categories in the group of parents who vaccinated their children was greater than that in the general sample. These data seemed to be related to the following statements: “Why did you vaccinate your child? “:

“... To not catch the disease, [...] to try to at least alleviate the disease a little, if she contracts it.” (DSC)

“... I try to keep all the vaccines up to date [...]. For as long as I can remember, there has always been a vaccine, and we have not been afraid. [...] It has worked thus far, right, why not vaccinate them? [...] Because it is something that is meant to be done well [...].” (DSC)

“Ah, the studies were well conducted [...] and I [...] feel safe, right?” (DSC)

Therefore, the vaccination behaviour of parents revealed that the motivation for those who vaccinated their children was the understanding that vaccination supports immunity, which reduces the chances of developing the disease.

Another motivating factor of vaccination was attitudes towards vaccination schedules and confidence regarding the vaccine against COVID-19; these factors were endorsed by the following statements:

“[...] It was to protect her, [...] to be [...] immune, [...] to prevent COVID, [...]; I try to keep all the vaccines up to date [...]. We believe in science [...].” (DSC).

Among parents who did not vaccinate their children, the predominant behaviour was inverted in relation to the other groups; the frequencies of those who received only the 1st dose of vaccine against COVID-19, those who were not vaccinated against influenza and those who did not trust the vaccine against COVID-19 were increased, whereas the frequency of the booster dose was decreased (Table V). These findings are corroborated by the statements of the parents regarding the reasons for the nonvaccination of their children:

“My oldest daughter caught (COVID), but it was not that severe, [...] it was like a mild flu [...]. Therefore, we did not think it was necessary, and then I chose not to vaccinate my daughter.” (DSC)

“... Lack of clarity [...]. I think it is not the time yet [...] because I do not believe much in a vaccine made in such a short time. [...] I did not think it was safe; [...] I was afraid of giving something bad. [...] Therefore, I took the risk of not giving the vaccine.” (DSC)

“... Why [...] I lost their documents [...].” (DSC)

In addition, from the statements made, the choice not to vaccinate was related to the lack of clarity of the parents about the studies related to the vaccine:

“... I am going to wait a little longer because thus far, this vaccine has not been proven to actually work. [...] There is a lack of [...] final studies. [...] I have a lot of doubts [...].” (DSC)

According to Brotas et al. (2021), the number of people with antivaccination attitudes is growing in Brazil, which is associated with a lack of information and unfounded assumptions. These assumptions include doubts about the origin of vaccines, resulting in distrust of the vaccine (Recuero, Soares, 2021, Recuero, Stumpf, 2021, Recuero, Volcan, Jorge, 2022).

Parents’ profile - Health literacy

As shown in Table VI, health literacy, which measures individuals’ ability to understand and use information for decision-making about health, did not differ between the groups. Therefore, all the groups exhibited the same pattern, which can be partially explained by the similar profiles of family income, education and place of residence among the parents.

The testimonies of the participants reinforced their profile, which was linked to the evaluation of health information. This information was accessed and used as a form of contribution to decision-making about health:

“The conclusion was truly on television, [...] social networks [...]. They said that the vaccine was safe, that it reduces suffering, and that the patient does not need to be intubated. From then on, we believed that by vaccinating our children, we are doing our part, right?” (DSC)

“I had opinions from health professionals who assured me that the vaccine was safe for the child. [...] I talked to their paediatrician, who we trust, and he said the vaccine was safe.” (DSC)

“Look, I do a lot of research, […] We always stay informed about vaccines and everything that is best for our children’s health. [...] What led me to vaccinate was precisely the information [..”].” (DS“)

“By the health centre.”” (DS“)

“... There was a campaign inside the school [...] I [...] signed a form and told them to get vaccinated.” (DSC)

“With a neighbour, [...] who vaccinated the child and had no problem [...]. In addition, since in my family no one had a problem when they got the vaccine, I did not have any objections, so my son had to be vaccinated too.” (DSC)

Thus, health information is accessed via social networks, media, the opinions of health professionals and data made available by health services. In this sense, the influence of social media has increased (Recuero, Volcan, Jorge, 2022), which can be assumed to affect topics related to COVID-19 and vaccination (Ullah et al., 2021).

However, parents with poor health literacy were common, composing approximately 50% of the interviewees, which increased their vulnerability. Therefore, content is produced and shared freely on digital platforms, which may even disseminate untrue information (Recuero, Volcan, Jorge, 2022).

Parents’ profile - Ability to recognize fake news

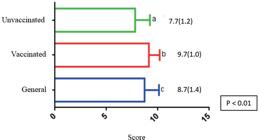

Figure 1 shows the mean scores in relation to the assessment of susceptibility to fake news. The group of parents who did not vaccinate their children presented a lower average score than the other groups did; however, for the parents who vaccinated their children, the average score was higher than the general average score.

Scores related to parents’ ability to recognize fake news. The data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Different letters indicate different values between the groups (p<0.01).

The 50th percentile value of the scores obtained from the parents’ answers was 9.0 points. Therefore, scores equal to or greater than this value were considered to indicate a high ability to recognize fake news, and lower scores indicated a low ability.

Figure 2 shows that individuals with a high ability to recognize fake news and those with a low ability to recognize fake news were less common among parents who did not vaccinate their children than among the overall cohort. Among parents who did not vaccinate their children, an inversion was noted in relation to the general groups and parents who vaccinated their children; that is, the frequency of low ability to recognize fake news was greater than that of high ability to recognize fake news.

Stratification of parents in the different groups according to their capacity to recognize fake news (general, N=410; vaccinated, N=284; unvaccinated, N=126).

Table VII presents the frequency of true or false answers for each statement of the assessment instrument. Those with the highest frequencies of “true” (incorrect) answers were Numbers 1, 4, 5, 7 and 10. For eight of the ten statements, the frequency of true responses was significantly greater for parents who did not vaccinate their children than for the other groups.

The greater frequency of truthful answers for some of these questions reinforced the lower confidence of parents who had not vaccinated their children, which can also be observed in some of the DSCs of parents who reaffirmed their distrust related to the COVID-19 vaccine due to fake news:

“Oh, girl, I see a lot of internet research, studies, television. You do not have to go very far, just look at the newspaper. [...].” (DSC)

“I see these better-informed doctors saying that it has not been proven to actually work. I watched an interview with a cardiologist, who said that the vaccine is not reliable, and I was very scared [...]. In addition, he said that the vaccine gives you COVID, [...], never take Pfizer or AstraZeneca, [...] they automatically change the DNA of the children and can cause very serious diseases [...] in the future.” (DSC)

“His paediatrician at the time did not indicate it.

We read a lot, and we confirmed with friends, family, and doctors, so they thought it would not be necessary for their age group. The mother of a colleague of my daughter who is a cardiologist said she was not going to vaccinate her daughter because she has a cardiac issue, so [...], I decided not to vaccinate mine either.” (DSC)

“... Based [...] on my practice. [...] I’m a principal in a school [...], seeing that I have around twenty students with COVID every week, even though they’re all vaccinated, the vaccine does not guarantee nontransmission, got it?” (DSC)

“... My daughter came crying saying, ‘Mother, I’m not going to get vaccinated because I’m going to die’, she said. I asked her ‘You saw that where?’, and she said she saw that on TV [...].” (DSC)

Several pieces of information disseminated on social media are known as “conspiracy theories”, which are associated with disinformation (Recuero, Stumpf, 2021) and aim to influence the public (Bertin, Nera, Delouvée, 2020), gaining space on digital platforms and contradicting scientific data (Oliveira, 2020). However, conspiracy theories lead to error induction (Wardle, Derakshan, 2017) and are related to vaccine resistance (Maci, 2019).

In Brazil, the National Immunization Program (PNI) is characterized by completeness and diversification, being recognized worldwide and presenting positive results due to its history of vaccination (Souto, Kabad, 2020).

However, over the years, vaccination coverage has decreased at the national level (Boccolini et al., 2023; Silveira, Conrad, Leivas Leite, 2021). Moreover, with the combination of the PNI with new vaccines, including one against COVID-19 associated with doubts in the population, vaccine resistance and refusal may increase (Souto, Kabad, 2020).

From the perspective of the history of success of the PNI, vaccines clearly represent the most appropriate strategy for the prevention of infectious diseases, with emphasis on their individual and collective benefits, especially during pandemics; therefore, the resistance of the population to vaccination needs to be understood continuously, as it is associated with the uninterrupted evaluation of vaccination coverage (Souto, Kabad, 2020).

CONCLUSION

We concluded that the decision to vaccinate children against COVID-19 was multifactorial and, according to the results of this research, factors such as child age, lack of confidence in the efficiency and safety of vaccines, parental age, and low ability to recognize fake news were involved in this behaviour. Health literacy did not influence behaviour in either experimental group, although parents with poor health literacy were common. Qualitative research that reinforces and strengthens the quantitative results is important.

LIMITATIONS

The instruments described in Table I and Table II are international and have not been validated for Brazilian Portuguese. Free translation was carried out but without validation of the questionnaires. However, these instruments were applied by trained interviewers, minimizing the effect of the lack of validation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work received funding from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Finance Code 001), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Espírito Santo (FAPES, grant number 220/2018), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq: grant number 314722/2021-1), and Instituto Capixaba de Ensino, Pesquisa e Inovação em Saúde (ICEPi).

REFERENCES

-

Alí M, Ahmed S, Bonna AS, Sarkar AS, Islam MA, Urmi TA, et al. Parental coronavirus disease vaccine hesitancy for children in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. F1000 Res. 2022;11:90. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.76181.2

» https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.76181.2 -

Allan S, Adetifa IMO, Abbas K. Inequities in childhood immunisation coverage associated with socioeconomic, geographic, maternal, child, and place of birth characteristics in Kenya. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21( 1):553. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-02106271-9

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-02106271-9 -

Ansolabehere S, Schaffner BF. Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Polit Anal. 2014;22(3):285-303. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24573071

» http://www.jstor.org/stable/24573071 - Araújo DRD. Como transcrever sua entrevista: técnica de editoração da transcrição de entrevista em pesquisa de abordagem compreensiva. Psico. 2001;32(1):147- 57.

-

Bagateli LE, Saeki EY, Fadda M, Agostoni C, Marchisio P, Milani GP. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children and adolescents living in Brazil. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101115

» https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101115 - Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 1977. 225 p.

-

Bertin P, Nera K, Delouvée S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: a conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front Psychol. 2020;11:565128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128 -

Boccolini PMM, Boccolini CS, Relvas-Brandt LA, Alves RFS. Dataset on child vaccination in Brazil from 1996 to 2021. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-01939-0

» https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-01939-0 - Brotas AMP, Costa MCR, Ortiz J, Santos CC, Massarani L. Discurso antivacina no YouTube: a mediação de influenciadores. Rev Eletr Comun Inf Inov Saúde. 2021;15(1):72-92.

-

Cubizolles C, Barjat T, Chauleur C, Bruel S, BotelhoNevers E, Gagneux-Brunon A. Evaluation of intentions to get vaccinated against influenza, COVID-19, pertussis and to get a future vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus in pregnant women. Vaccine. 2023;41(49):7342-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.10.067

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.10.067 -

Dal Grande E, Chittleborough CR, Campostrini S, Dollard M, Taylor AW. Pre-survey text messages (SMS) improve participation rate in an Australian mobile telephone survey: an experimental study. PLoS One. 2016;11( 2):e0150231. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.015023

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.015023 -

Di Giuseppe G, Pelullo CP, Volgare AS, Napolitano F, Pavia M. Parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children with COVID-19 vaccine: results of a survey in Italy. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(4):550-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.003 -

Francis AI, Ghany S, Gilkes T, Umakanthan S. Review of COVID-19 vaccine subtypes, efficacy and geographical distributions. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1159):389-94. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140654

» https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140654 -

Galanis P, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, Katsiroumpa A, Kaitelidou D. Willingness, refusal and influential factors of parents to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Prev Med. 2022;157:106994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.106994

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.106994 -

García-Toledano E, Palomares-Ruiz A, CebriánMartínez A, López-Parra E. Health education and vaccination for the construction of inclusive societies. Vaccines. 2021;9(8):1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080813

» https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080813 -

Krieger N, LeBlanc M, Waterman PD, Reisner SL, Testa C, Chen JT. Decreasing survey response rates in the time of COVID-19: implications for analyses of population health and health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(6):667-70. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307267

» https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307267 -

Lavoie K, Gosselin-Boucher V, Stojanovic J, Gupta S, Gagné M, Joyal-Desmarais K, et al. Understanding national trends in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Canada: results from five sequential cross-sectional representative surveys spanning April 2020-March 2021. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e059411. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059411

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059411 - Lefèvre F, Lefèvre AMC. O discurso do sujeito coletivo: um novo enfoque em pesquisa qualitativa; desdobramentos. Porto Alegre: EDUCS; 2003.

-

Li P, Fu JB, Li KF, Liu JN, Wang HL, Liu LJ, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 in the terminal stages of the incubation period: a familial cluster. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:452-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.027

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.027 -

Maci S. Discourse strategies of fake news in the antiVAX campaign. Lang Cult Mediat. 2019;6(1):15-43. https://doi.org/10.7358/LCM-2019-001-maci

» https://doi.org/10.7358/LCM-2019-001-maci -

Maciel ELN, Gomes CC, Almada GL, Medeiros Junior NF, Cardoso OA, Jabor PM, et al. COVID-19 in children, adolescents and young adults: a cross-sectional study in Espírito Santo, Brazil, 2020. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2021;30( 4):e20201029. https://doi.org/10.1590/S167949742021000400001

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S167949742021000400001 -

Montagni I, Ouazzani-Touhami K, Mebarki A, Texier N, Schück S, Tzourio C, CONFINS group. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine is associated with ability to detect fake news and health literacy. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43(4):695-702. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab028

» https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab028 -

Moscadelli A, Albora G, Biamonte MA, Giorgetti D, Innocenzio M, Paoli S, et al. Fake news and COVID-19 in Italy: results of a quantitative observational study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165850

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165850 -

Matos CCS, Tavares JSC, Couto MT. Interface (Botucatu, Online). 2024;28:e230492. https://doi.aorg/10.1590/interface.230492

» https://doi.aorg/10.1590/interface.230492 -

Oliveira T. Desinformação científica em tempos de crise epistêmica: circulação de teorias da conspiração nas plataformas de mídias sociais. Fronteiras Estud Midiáticos. 2020;22(1):21-35. https://doi.org/10.4013/fem.2020.221.03

» https://doi.org/10.4013/fem.2020.221.03 -

Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde (OPAS). Desinformação alimenta dúvidas sobre vacinas contra a COVID-19, afirma diretora da OPAS. 2021. Available from: https://www.paho.org/pt/noticias/21-4-2021desinformacao-alimenta-duvidas-sobre-vacinas-contracovid-19-afirma-diretora-da

» https://www.paho.org/pt/noticias/21-4-2021desinformacao-alimenta-duvidas-sobre-vacinas-contracovid-19-afirma-diretora-da -

Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde (OPAS). Perguntas frequentes: vacinas contra a COVID-19. 2022. Available from: https://www.paho.org/pt/vacinascontra-covid-19/perguntas-frequentes-vacinas-contracovid-19 [Accessed 26 Sep 2022].

» https://www.paho.org/pt/vacinascontra-covid-19/perguntas-frequentes-vacinas-contracovid-19 -

Randolph HE, Barreiro LB. Herd immunity: understanding COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;52(5):737-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.012

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.012 -

Recuero R, Soares F. O discurso desinformativo sobre a cura do COVID-19 no Twitter: estudo de caso. E-Compós. 2021;24. https://doi.org/10.30962/ec.2127

» https://doi.org/10.30962/ec.2127 - Recuero R, Stumpf EM. Características do discurso desinformativo no Twitter: estudo do discurso antivacinas da COVID-19. In: Caiado R, Leffa V, editors. Linguagem: tecnologia e ensino. Campinas: Pontes Editores; 2021. p. 111-37.

-

Recuero R, Volcan T, Jorge FC. Os efeitos da pandemia de COVID-19 no discurso antivacinação infantil no Facebook. Rev Eletr Comun Inf Inov Saúde. 2022;16(4):859-82. https://doi.org/10.29397/reciis.v16i4.3404

» https://doi.org/10.29397/reciis.v16i4.3404 - Sales F, Souza FC, John VM. O emprego da abordagem DSC (discurso do sujeito coletivo) na pesquisa em educação. Linhas. 2007;8(1):124-45.

-

Santé Publique France. Covid-19: une enquête pour suivre l’évolution des comportements et de la santé mentale pendant l’épidémie. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 7]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/coviprev-une-enquete-poursuivre-l-evolution-des-comportements-et-de-la-santementale-pendant-l-epidemie-de-covid-19 [Accessed 10 Jun 2022].

» https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/coviprev-une-enquete-poursuivre-l-evolution-des-comportements-et-de-la-santementale-pendant-l-epidemie-de-covid-19 -

Seara-Morais GJ, Avelino-Silva TJ, Couto M, AvelinoSilva VI. The pervasive association between political ideology and COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Brazil: an ecologic study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1606. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16409-w

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16409-w -

Silveira MM, Conrad NL, Leivas Leite FP. Effect of COVID-19 on vaccination coverage in Brazil. J Med Microbiol. 2021;70(11):10.1099/jmm.0.001466. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001466

» https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001466 -

Souto EP, Fernandez MV, Rosário CA, Petra PC, Matta GC. Hesitação vacinal infantil e COVID-19: uma análise a partir da percepção dos profissionais de saúde. Cad Saude Publica. 2024;40(3):e00061523. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311XPT061523

» https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311XPT061523 -

Souto EP, Kabad J. Hesitação vacinal e os desafios para enfrentamento da pandemia de COVID-19 em idosos no Brasil. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2020;23(5):e210032. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-22562020023.210032

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-22562020023.210032 -

Skitarelić N, Vidaić M, Skitarelić N. Parents’ versus grandparents’ attitudes about childhood vaccination. Children (Basel). 2022;9(3):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9030345

» https://doi.org/10.3390/children9030345 -

Ullah I, Khan KS, Tahir MJ, Ahmed A, Harapan H. Myths and conspiracy theories on vaccines and COVID-19: potential effect on global vaccine refusals. Vacunas. 2021;22(2):93-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacune.2021.01.009

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacune.2021.01.009 - Wardle C, Derakhshan H. Information disorder: toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe. 2017;1:1-209.

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2022. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=CjwKCAjwwqaGBhBKEiwAMk-FtCmI8Xh58rZB3V81q18SmmXT4ZX0tuQzABkTLLZY1B1eFdlpF1rNExoC9wsQAvD_BwE [Accessed 9 Jun 2022].

» https://covid19.who.int/?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=CjwKCAjwwqaGBhBKEiwAMk-FtCmI8Xh58rZB3V81q18SmmXT4ZX0tuQzABkTLLZY1B1eFdlpF1rNExoC9wsQAvD_BwE

Edited by

-

Associated Editor: Patrícia Melo Aguiar

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

05 Dec 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

12 June 2024 -

Accepted

09 Dec 2024

Reasons for vaccination hesitancy against covid-19 in children and young people: a qualitative‒quantitative study

Reasons for vaccination hesitancy against covid-19 in children and young people: a qualitative‒quantitative study