Abstract

Academic literature on US Foreign Policy to South America usually states its lack of attention to the region in the post 9/11 period. I aim to problematize this assertion through an analysis of US regional security policy. Therefore, I consider data referring to military and economic assistance, arms transfers, and the SOUTHCOM position towards its area of responsibility, as well as official documents and diplomatic cables. I conclude that, although the region was not a priority, a waning in US actions or a moment of neglect in its policy towards it was likewise not observed. From a historical perspective, the area was never the main focus of attention, but there is a specialized bureaucracy that works on the region to maintain US hegemony. Therefore, the investigation indicates that Latin American assertiveness during the 2000s was caused primarily by the conjunction of the ascension of leftist governments and quest for autonomy, as well as by Chinese and Russian involvement in Latin America, but not by US neglect. The article is divided into six sections, including the introduction and final remarks. Following the introduction, I analyse the academic literature regarding USA-Latin American relations in the second section, the US assistance in the third, the SOUTHCOM postures in the fourth, and the strategies deployed by the USA regarding great powers and arms transfers in the fifth. Finally, I present the final remarks.

Keywords

: USA-Latin America; military to military relations; foreign policy; international security; hegemony; militarisation

Resumo

A literatura acadêmica sobre a política externa dos EUA para a América do Sul geralmente afirma uma falta de atenção para esta região no período pós-11 de setembro. Pretendo problematizar essa afirmação por meio de uma análise da política de segurança regional dos Estados Unidos. Considero os dados referentes à assistência militar e econômica, transferência de armas e a posição do SOUTHCOM em relação à sua área de responsabilidade, bem como documentos oficiais e cabos diplomáticos. Concluo que, embora a região não tenha sido uma prioridade, não houve um enfraquecimento das ações dos Estados Unidos ou um momento de abandono. Do ponto de vista histórico, a área nunca foi o foco principal das atenções, mas há uma burocracia especializada que trabalha para manter a hegemonia dos EUA. Portanto, a investigação indica que a assertividade latino-americana durante os anos 2000 foi causada principalmente pela conjunção da ascensão dos governos de esquerda e centro-esquerda e pela busca por autonomia e envolvimento chinês e russo na América Latina, não por negligência dos EUA. O artigo está dividido em seis seções, incluindo a introdução e as considerações finais. Após a introdução, a segunda seção é dedicada à análise da literatura acadêmica, a terceira ao estudo da assistência dos Estados Unidos, a quarta examina as posturas do SOUTHCOM e a quinta seção investiga as estratégias dos Estados Unidos em relação a grandes potências e transferências de armas. Finalmente, as considerações finais são apresentadas.

Palavras-chave

: Estados Unidos-América Latina; relações militares-militares; política externa; segurança internacional; hegemonia; militarização

Introduction

A significant segment of the literature on Inter-American relations in the period after 9/11 has been concentrated on a perceived decline of US hegemony1 1 Hegemony, as discussed by a relevant segment of the literature, can be defined as the pre-eminence in economic and military fields, which underpin the leadership and control exercised by great powers. Notwithstanding, this conception has limits, since it precludes the analysis of the ideational dimension. It is also possible and productive to define hegemony on neo-Gramscian terms, as outlined by Cox (1981), as a fit between power, ideas, and institutions articulated by the hegemon to ensure control of the international order. The hegemon maintains its control over the periphery through material power and consensus, manufactured through ideas and institutions. In this article, I focus on the material aspect of hegemony, but the sphere of ideas should also be investigated in further analysis. in Latin America.2 2 In this article, I start with the premise that US influence in South America is distinct, in some respects, from its involvement in North and Central America (Teixeira 2012). South America is further away and has ampler autonomy, especially greater countries such as Brazil and Argentina. US involvement was also distinct among South American sub regions, since the Andes was perceived as more unstable and as the biggest source of threats. However, the literature tends to treat Latin America as a whole, the US planning is dedicated to the entire Hemisphere and the SOUTHCOM is responsible for all the American regions south of Mexico. Therefore, especially in the literature review, it will be necessary to make mentions to Latin America, even when the focus is South America. According to the bibliography, there are three main hypotheses to explain this situation: 1) the lack of attention from the United States to the region, 2) South American countries renewed quest for autonomy and 3) the challenge presented by extra-hemispheric actors. This situation generated the perception of a post-hegemonic hemisphere (Hakim 2006Hakim, P. 2006. ‘Is Washington Losing Latin America?’ Foreign Affairs 85 (1): 39-53.; Crandall 2011Crandall, R. 2011. ‘The Post-American Hemisphere. Power and Politics in an Autonomous Latin America.’ Foreign Affairs 9 (3): 83-95.; Paz 2012Paz, G S. 2012. ‘China, United States and Hegemonic Challenge in Latin America: An Overview and Some Lessons from Previous Instances of Hegemonic Challenge in the Region.’ The China Quarterly (209): 18-34.; Riggirozzi and Tussie 2012Riggirozzi, P and D Tussie. 2012. The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism. The Case of Latin America. New York: Springer.; Lima 2013Lima, M R S de. 2013. ‘Relações interamericanas: a nova agenda sul-americana e o Brasil.’ Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política (90): 167-201.; Sabatini 2013Sabatini, C. 2013. ‘Will Latin America Miss U.S. Hegemony?’ Journal of International Affairs 66 (2): 1-15.; Drezner 2015Drezner, S. 2015. ‘A Post-Hegemonic Paradise in Latin America?’ Americas Quartely [online], 3 February.; Long 2015Long, T. 2015. Latin America Confronts the US. Asymmetry and Influence. New York: Cambridge University Press.; Tulchin 2016Tulchin, J S. 2016. América Latina x Estados Unidos: uma relação turbulenta. São Paulo: Editora Contexto.).

The main argument presented by the literature regarding the first hypothesis is that, following the terrorist attacks, US Foreign Policy3 3 Foreign Policy is hereby understood as ‘the policies and actions of national governments oriented toward the external world outside their own political jurisdictions’ (Caporaso 1986: 9). In this sense, ‘[m]ilitary policies are framed and implemented in the context of a state’s foreign policy’ (Caporaso et al1986: 11). was directed to the Middle East and no comprehensive plan was made regarding the Hemisphere. As an example of this interpretation, Hakim (2006: 39) claimed that after 9/11, ‘Washington effectively lost interest in Latin America.’ Similarly, Riggirozzi and Tussie’s (2012: 20) affirm that ‘the regional scenario [was] marked by a loss of interest in the United States with building its backyard.’

Riggirozzi and Tussie (2012)Riggirozzi, P and D Tussie. 2012. The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism. The Case of Latin America. New York: Springer. argue that the US lack of interest – in combination with the quest for autonomy by South American countries – opened the path to a post-hegemonic hemisphere and a new awakening for regionalism. According to them, the regional institutions created in the 2000s, such as the Union Suramericanna de Naciones (UNASUR) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), benefited from the context to advance the goal of regional autonomy. Both institutions emphasized political cooperation and promoted the idea that Latin America could solve its problems without external interference. UNASUR’s structure included a Defence Council, an important step towards autonomy since, for the first time, those countries discussed defence cooperation without US participation (Saint-Pierre 2011Saint-Pierre, H L. 2011. ‘“Defesa” ou “segurança”?: reflexões em torno de conceitos e ideologias.’ Contexto Internacional 33 (2): 407-433.; Vitelli 2016Vitelli, M G. 2016. ‘Comunidad e identidad en la cooperación regional en defensa: entendimientos en conflicto sobre pensamiento estratégico en el Consejo de Defensa Sudamericano.’ Revista da Escola de Guerra Naval 2 (2): 233-260.).

Therefore, the creation of regional institutions was connected with the quest for autonomy in South America. According to Puig (1984: 44), autonomy is a process of broadening the margins for endogenous decision-making. When the concept of autonomy was formulated, in the 1980s, the Brazilian sociologist Hélio Jaguaribe, and the Argentinean jurist Juan Carlos Puig, related it to the search for new external partners and the questioning of US primacy.4 4 In the 1990s, a new conception of autonomy was formulated, especially by Escudé (1992) and Russell and Tokatlian (1990). Escudé understood the exercise of autonomy was compatible with alignment to the great power, especially on the political-strategic dimensions, and Russel and Tokatlian argued it was consonant with the accession into international regimes. For a literature review, see the article ‘Cooperación dependiente asociada’ written by Arlene Ticker and Mateo Morales (2015). The concept was mobilized by the left-leaning governments in the 2000s, in a different international context, marked by declining US hegemony. Those governments fomented Latin American countries’ assertiveness and sought new partners beyond the hemisphere. Jaguaribe’s (1979Jaguaribe, H. 1979. ‘Autonomía periférica y hegemonía céntrica.’ Estudios Internacionales 12 (46): 91-130.) analysis on the subject highlighted that the quest for autonomy corresponds to a combination of an internal process, composed of national viability, and an international one, permissibility. In the 2000s, Latin American left-leaning governments attempted to resume developmentalist policies and the quest for autonomy in foreign policy, seeking out to amplify national viability (Wylde 2016Wylde, C. 2016. ‘Post-neoliberal developmental regimes in Latin America: Argentina under Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner.’ New Political Economy 21 (3): 322-341.).

In addition, Chinese growth and Russian assertiveness created new opportunities for Latin America, reducing the United States’ relative power position (Crandall 2011Crandall, R. 2011. ‘The Post-American Hemisphere. Power and Politics in an Autonomous Latin America.’ Foreign Affairs 9 (3): 83-95.) and expanding international permissibility. As expected, this situation stirred suspicions in Washington DC, which since 2005 has been hosting congressional hearings aimed at assessing the regional presence of external actors in the Hemisphere (Subcommittee On Western Hemisphere and Peace Corps And Narcotics Affairs 2005).

This article aims to problematize the assumption of US neglect towards Latin America after 9/11. As Long (2016)Long, T. 2016. ‘The United States and Latin America: The Overstated Decline of a Superpower.’ The Latin Americanist (60): 497-524. claimed, the perception of neglect became common sense, being repeated by the media, policymakers, and experts, yet was hardly ever demonstrated. I focus on the US security policy to the region during Bush and Obama administrations, analysing three foreign policy dimensions, namely, US assistance to the region, the SOUTHCOM postures, and US strategies regarding big powers advances. I consider data referring to military and economic aid, arms transfers, speeches addressed by SOUTHCOM commanders, as well as official documents and diplomatic cables.

I conclude that, although the region was not a priority, there was not a waning in US actions. The investigation indicates that Latin American assertiveness during the 2000s was caused primarily by the conjunction of the ascension of leftist governments and by Chinese and Russian involvement in Latin America, not by US neglect. Therefore, rather than being internal to US Foreign Policy dynamics, the shift was a product of changes external to the United States. In the next section, I briefly expose the literature on United States-Latin America relations. The third section is dedicated to the study of US assistance, the fourth section examines the SOUTHCOM stances, and, finally, the fifth section investigates the US strategies regarding great powers and arms transfers. Due to spatial and scope limitations, the article will not discuss the theoretical aspect of US foreign policy, its inter-bureaucratic dynamics, nor the changes the country underwent in past years.

The United States and Latin America: neglect, militarisation and hegemony

The idea of US neglect towards its hemisphere is not a 21st century novelty. According to Pecequilo (2011)Pecequilo, C. 2011. A Política Externa dos Estados Unidos. Continuidade ou Mudança? Porto Alegre: Editora UFRGS., at least since the end of World War II, Latin America is not a priority for US foreign policy. In a 1973 Foreign Affairs article, Petersen (1973Petersen, G H. 1973. ‘Latin America: Benign Neglect Is Not Enough.’ Foreign Affairs 51 (3): 598-607.: 598) claimed that ‘the United States has no Latin American policy, save one of benign neglect.’ Even in the 1990s, when a US effort to create a hemispheric economic bloc was observed, its central foreign policy concerns were directed to Eurasia and the Middle East. The consolidation of Central Europe as a stable area, integrated with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), became a primary issue, alongside topics such as nuclear non-proliferation and the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians (Kjonnerod 1992Kjonnerod, E. 1992. Evolving U.S. Strategy for Latin America and the Caribbean: Mutual Hemispheric Concerns and Opportunities for the 1990s. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press.).

In spite of that, the Summits of the Americas, since 1994, and the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) negotiations, revealed the existence of an explicit US regional project and increased the perception that the USA sought to reconfigure its hemispheric hegemony. This process was not limited to the economic field and, when it comes to hemispheric security, it included a reformulation of the Organization of American States (OAS) and the launch of the Defence Ministerial of the Americas since 1995 (Saint-Pierre 2011Saint-Pierre, H L. 2011. ‘“Defesa” ou “segurança”?: reflexões em torno de conceitos e ideologias.’ Contexto Internacional 33 (2): 407-433.). However, this context would change in the following decade, during which the election of leftist leaders and the rejection of the FTAA in 2005 were responsible for creating a perception of US neglect and declining power.

The lack of priority indicates that the President and the Secretaries of State and Defence have their daily routine dominated by issues relating to other geographical areas, which they perceive as main concerns. It does not follow, however, that there is no foreign policy to Latin America. Bureaucracies and other actors, including the Congress and the intelligence community, continue to operate in the region (Buxton 2011Buxton, J. 2011. ‘Forward into History: Understanding Obama’s Latin American Policy.’ Latin American Perspectives 38 (4): 29-45.; Brenner and Hershberg 2013Brenner, P and E Hershberg. 2013. ‘Washington e a Ordem Hemisférica: Explicações para a Continuidade em meio à Mudança.’Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política (90): 37-63.). There are also strategies formulated within the National Security Council and operationalized by the multiple US agencies involved in foreign policy. Moreover, the USA’s global strategy is translated into the regional context – especially when it comes to the identification and containment of threats.

The ‘global war on terror’ did not exclude Latin America. It contributed to the framing of certain local issues within the paradigm of combatting terror – especially through the association between drug traffic and terrorism, which took place in the fight against insurgent groups in Peru and Colombia (Prevost 2007Prevost, G. 2007. ‘Introduction – The Bush Doctrine and Latin America.’ In G Prevost and C Campos (eds), The Bush Doctrine and Latin America. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-11.; Emerson 2010Emerson, R G. 2010. ‘Radical Neglect? The “War on Terror” and Latin America.’ Latin American Politics and Society 52 (1): 33-62.; Buxton 2011Buxton, J. 2011. ‘Forward into History: Understanding Obama’s Latin American Policy.’ Latin American Perspectives 38 (4): 29-45.; Battaglino 2012Battaglino, J. 2012. ‘Defence in a Post-Hegemonic Regional Agenda: The Case of The South American Defence Council.’ In P Riggirozzi and D Tussie (eds), The Rise of Posthegemonic Regionalism: The Case of Latin America. New York: Springer.; Isacson 2015Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108.; Tokatlian 2015Tokatlian, J G. 2015. ‘The War on Drugs and the Role of the SOUTHCOM.’ In B Bagley and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, pp. 437.).The war on terror contributed to the militarisation of US Foreign Policy to the region, denoting an increase in the military influence in foreign policy issues5 5 The militarisation of US foreign policy is not restricted to Latin America. For a discussion on the subject, see the book ‘Mission Creep: The Militarisation of U.S. Foreign Policy?’ by Gordon Adams and Shoon Murray. (Prevost 2007Prevost, G. 2007. ‘Introduction – The Bush Doctrine and Latin America.’ In G Prevost and C Campos (eds), The Bush Doctrine and Latin America. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-11.; Isacson 2015Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108.; Tokatlian 2015). According to Tokatlian:

The events that transpired on 9/11 further facilitated the relative influence of SOUTHCOM in Miami. While Washington’s attention and resources were focused on the war on terrorism and on Asia, SOUTHCOM increased its influence on U.S. foreign policy and defense concerning Latin America and guaranteed funding through a deadly image of the narco-terrorists […] (Tokatlian 2015: 79).

Militarisation meant that the US agencies perceived and dealt with social, economic and political problems as security issues, and that transnational organized crime and drug trafficking were encompassed to the war on terror logic (Saint-Pierre 2011Saint-Pierre, H L. 2011. ‘“Defesa” ou “segurança”?: reflexões em torno de conceitos e ideologias.’ Contexto Internacional 33 (2): 407-433.; Isacson 2015Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108.; Tokatlian 2015). Moreover, in 2008, the United States recreated the Fourth Fleet, that had been deactivated since the 1950s.

With regard to the physical presence of US military personnel in Latin America, the 1990s represented a moment of relative losses to the hegemon, yet it did not imply its absence or decline. The presence of US military personnel in Latin America decreased considerably during that decade, due to the closure of bases in Panama – as part of the agreements regarding the American withdrawal from the Canal. The headquarters of the Southern Command was transferred to Miami and the head office of the School of the Americas, relocated to Fort Benning in Georgia (Long 2016Long, T. 2016. ‘The United States and Latin America: The Overstated Decline of a Superpower.’ The Latin Americanist (60): 497-524.).

The subsequent decade was also marked by difficulties. In 2009, Ecuador did not renew the agreement that authorized the maintenance of a US military base in the city of Manta. Since then, negotiations to replace the base have failed. Currently, the United States has only two Cooperative Security Locations in Latin America, small military facilities governed by formal agreements, namely one in El Salvador and the other in Aruba-Curaçao. Thus, it has none in South America (Vaicius and Isacson 2003Vaicius, I and A Isacson. 2003. ‘The “War on Drugs” meets the “War on Terror”: The United States’ military involvement in Colombia climbs to the next level.’ Center for International Policy International Policy Report).

However, this does not mean the hegemon has a scarce military presence in Latin America. According to Bitar (2016: 2), ‘US military has had either permanent or temporary presence and has conducted operations in the last decade in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Peru’ besides from being granted informal access to airports in Panama and Ecuador. The US government worked on informal agreements with its counterparts in Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia to guarantee the country’s continued military access to the region.

According to Bitar (2016), the preference for informal arrangements is determined by the internal politics of Latin American countries, given that their national leaders perceive political costs with regard to the installation of military bases in their national territories. However, informal access is also in line with the external power projection policy of the USA – distinguished by the construction of smaller, more flexible and informal bases, not subject to the scrutiny of the American Congress (Bitar 2015).

Conversely, in the economic field, the United States succeeded to establish Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with Chile, Colombia, Peru, and the Dominican Republic-Central America. The hemispheric power managed to ‘lock’ those countries onto the neoliberal reforms and maintain an important partnership with them. Moreover, in 2009, the Pacific Arc Initiative was created, reuniting US regional allies into a multilateral sphere. The initiative was supported and inspired by the USA and emphasized commitments to free trade and to the adoption of market reforms (Biegon 2017Biegon, R. 2017. US Power in Latin America. Renewing Hegemony. New York: Routledge.). The negotiations regarding the multilateral Transpacific Partnership (TPP), also promoted by the USA, which included Chile, Peru and Mexico, aimed to contain China’s increasing trade and reach in the Pacific region and was a means to preserve US hegemony.

Long (2016)Long, T. 2016. ‘The United States and Latin America: The Overstated Decline of a Superpower.’ The Latin Americanist (60): 497-524. highlights that experts and academics usually overstress the US decline, while not adequately addressing its remaining structural power, remarkably exercised through the dollar hegemony and through its massive military strength. The author claims that the USA remains the leading source of military training for most countries in South America. In the financial sphere, the power of the dollar persists, Latin American countries are dependent on it and US monetary policy has a significant impact on the financial performance of its neighbours.

As for big powers advances in Latin America, starting in the 2000s, bilateral trade and Chinese investments in the region expanded exponentially, generating other sources of financing to South American countries (Kaplan 2016; CEPAL 2018CEPAL. 2018. Explorando nuevos espacios de cooperación entre América Latina y el Caribe y China. Santiago.). Russia also made regional economic incursions, particularly in the energy sector and arms transfers. In 2013, the Monroe Doctrine was declared extinct by the then Secretary of State John Kerry, revealing the USA’s intention to manifest an image of acceptance to the extra-hemispheric power incursions in its traditional area of influence.

Although Russian and Chinese advances represent a relevant challenge to US power, which I do not intend to minimize, these did not imply in a complete shift in US power and are particularly concentrated in, and limited to, specific countries. Despite its general trade growth, China’s investments are focused in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela (Gallagher and Myers 2019Gallagher, K P and M Myers. 2019. “China-Latin America Finance Database.” Washington: Inter-American Dialogue.). Russia’s participation, in turn, mainly consisted of the selling of weapons to Venezuela. Long (2016)Long, T. 2016. ‘The United States and Latin America: The Overstated Decline of a Superpower.’ The Latin Americanist (60): 497-524. concludes that this is nonetheless not a radical change: direct investment from other parts of the globe , especially from Europe, is a constant in Latin America. However, it is worth mentioning that the Japanese economic challenge, in terms of trade and investment, was a source of US concern in the 1990s when Japan started to operate in the hemisphere (Paz 2012Paz, G S. 2012. ‘China, United States and Hegemonic Challenge in Latin America: An Overview and Some Lessons from Previous Instances of Hegemonic Challenge in the Region.’ The China Quarterly (209): 18-34.).

These contradictory factors point to a shrinking but still important US hegemony and raise some questions. Was the United States indeed neglecting the region or was its loss of economic pre-eminence balanced by an increase in its military influence? Was 9/11 a turning point in US foreign policy to the region? In order to better understand US foreign policy to Latin America, in the following section, the three following dimensions will be analysed: US assistance to the region, the SOUTHCOM stances and US strategies regarding big powers advances.

US economic and security assistance to Latin America after 9/11

United States assistance directed to the region is a significant source of information to assess if the events in question, that took place in 2001, marked a turning point in US policy to Latin America and entailed the beginning of a period of neglect. Isacson (2015)Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108. highlights that the US foreign assistance policy changed after the 9/11 attacks and the Department of Defence became increasingly responsible for financing projects – usually, a prerogative held by the Department of State.6 6 Usually, the funding was directed through the Department of State, even in cases in which the Department of Defense was responsible for its implementation. Two lines of finance directed specifically to combat terrorism were created, namely the Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program and the Support of Special Operations to Combat Terrorism – Section 1208. Financial resources were assigned to South American countries through both of these programs.

Moreover, even before the 9/11 attacks, the Department of State started to publish annual reports regarding the measures taken by each particular country to combat terrorism. After 9/11, those reports also recommended the adoption of anti-terror bills and measures to strengthen institutions to tackle financing of terrorism and money laundering. The reports on terrorism were added to the long existent reports on drug trafficking, possibly leading to sanctions should US demands not be accomplished (Silva 2013Silva, L L da. 2013. A questão das drogas nas relações internacionais : uma perspectiva brasileira. Brasilia: FUNAG.).

Data from the Center for International Policy7 7 Although USAID has its own aid database, it does not count on the assistance delivered by the Department of Defense. That is the reason why data here comes from the Security Assistance Monitor database. confirms that the United States did not decrease assistance to Latin America in the years following the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Graph 1). However, relevant differences among sub-regions have been observed. A significant portion of the US aid was allocated to South America (Graph 2), particularly to the Andean countries (Graph 4), while the Southern Cone and Brazil received a minor portion of it (Graph 3). Therefore, US policymakers did not treat South America in a homogenous way, and it seems their main concerns were related to the Andean region.

The USA perceived relatively fewer threats in the Southern Cone, paying less attention to the area in terms of assistance, particularly regarding security issues. The coca producing countries are all located in the Andean region, corroborating with the assumption of that area as more unstable and as a source of threats. The Southern Cone countries, in turn, especially Brazil and Argentina, are relatively more resourceful and historically less dependent on US assistance (Rouquié 1984Rouquié, A. 1984. O Estado Militar na América Latina. Santos: Editora Alfa Omega.). The USA usually expects them to collaborate and share responsibilities, meaning that they also should assume tasks to assist their neighbours (Bandeira 2010Bandeira, L A M. 2010. Brasil, Argentina e Estados Unidos. Conflito e Integração na América do Sul. 3rd edition. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.).

Changes in discourse among the US foreign policy community have likewise been observed. After 2001, the phenomenon of drug and insurgencies were conceived as narco-terrorism. Military operations on Andean countries became the central US security concern in the Western Hemisphere, and Colombia became one of the main US aid destinations, ranked sixth among the top ten countries to receive assistance from 2000 to 2016 (Center for International Policy 2019Center for International Policy. 2019. Security Assistance Monitor. At https://securityassistance.org/ [Accessed on 13 April 2020].

https://securityassistance.org/...

; Milani 2019Milani, L. 2019. ‘A Argentina e o Brasil frente aos Estados Unidos: clientelismo e autonomia no campo da segurança internacional.’ PhD Thesis. Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Brazil.).

The relevant amount of aid destined to Colombia shows how significant that relationship was for the USA. The country became the major US ally in South America, critical to ensure its regional presence. Colombia was the single key exception to the rise of left-leaning governments in Latin America, and that bilateral relationship became a means to react to the regional phenomenon. Colombia geographic location was particularly attractive – it is a neighbour of Venezuela, the chief country concerning the ‘pink tide’ radical segment. Therefore, the United States’ alliance with Colombia was a way to counter the left and anti-American leading governments in South America.

The assistance to Colombia was higher during the Álvaro Uribe presidency, which coincided with the hard-line policies against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, in Spanish) (Security Assistance Monitor 2019). The repression deployed debilitated the rebel armed group and, during Juan Manuel Santos presidency, Colombia initiated a peace process. The USA supported the negotiations and started to perceive the Andean country as a success case and as an ally that could be responsible for exporting security. That consideration meant exporting the lessons learned in the Colombian training to other countries’ anti-insurgency and anti-drugs forces, not only in Latin America but also worldwide, including Afghanistan (Tickner and Morales 2015Tickner, A B and M Morales. 2015. ‘Cooperação dependente associada. Relações estratégicas Estratégicas asimétricas entre Colombia y Estados Unidos.’ Colombia Internacional 85: 171-206.; Kassab and Rosen 2016Kassab, H S and J D Rosen. 2016. The Obama Doctrine in the Americas: Security in the Americas in the Twenty-First Century. Lanham: Lexington Books.). In 2018, Colombia became a NATO global partner, consolidating its full alignment with Western powers.

Colombia, however, was not the only area where the United States government was acting at that moment. Immediately after 9/11, the US Western Hemisphere policy aimed to pressure the Latin American left-leaning governments. In 2002, the US government recognized the two-day government of Pedro Carmona in Venezuela, which resulted from a failed coup d’état designed to overthrow Hugo Chavez. It also expected to contain the pink wave through the meddling in the internal politics in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Bolivia (Leogrande 2007Leogrande, W M. 2007. ‘A Poverty of Imagination: George W. Bush’s Policy in Latin America.’ Journal of Latin American Studies 39 (2): 355-385.; Vanderbush 2009Vanderbush, W. 2009. ‘The Bush Administration Record in Latin America : Sins of Omission and Commission.’ New Political Science 31 (3): 337-359). Eventually, those actions could not avoid left-leaning governments from being elected in the region, and sometimes even backfired. In fact, in the case of Bolivia, actions taken by the State Department were counterproductive, and the Embassy’s explicit opposition to Evo Morales in 2002 – a time in which he was not widely known, helped the cocalero leader to gain publicity and popular support (Leogrande 2007Leogrande, W M. 2007. ‘A Poverty of Imagination: George W. Bush’s Policy in Latin America.’ Journal of Latin American Studies 39 (2): 355-385.; Vanderbush 2009Vanderbush, W. 2009. ‘The Bush Administration Record in Latin America : Sins of Omission and Commission.’ New Political Science 31 (3): 337-359).

As a result, the strategy had to change. At the time of George W. Bush’s second term, the United States strategy focused on creating a positive agenda by searching partners and areas of possible cooperation with the moderate left-leaning governments. Colombia was not the only US partner in South America. Chile, Peru and Paraguay were also relatively aligned to the USA. The relationship with Brazil was ambiguous, but the United States explored common areas for cooperation. The signing of the Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) and of the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), both in 2010, shows that there was scope for collaboration. In 2007, the Assistant Secretary of State to Western Hemispheric Affairs, Thomas Shannon, described the bilateral relationship with Brazil as a priority (Shannon 2007Shannon, T. 2007. ‘Vision and Foreign Assistance Priorities for the Western Hemisphere. Testimony Before the House of Representatives Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere Committee on Foreign Affairs.’ Washington, DC.). Therefore, besides Colombia, Brazil was a focal point of the US Latin America policy.

The assistance data also indicates differences between the administrations of George W. Bush (2001-2008) and Barack Obama (2009-2016). During the Obama years, the amount of economic assistance became greater than the security aid, except in the Andes (Graph 4), partially reversing the tendency of militarisation. This predisposition was connected to Obama’s foreign policy in general. Back then, the idea of smart power,8 8 Originally coined by Joseph Nye, the idea of smart power was highlighted by Hillary Clinton on her nomination speech before the Congress. According to her, ‘[…] we must use what has been called ‘smart power,’ the full range of tools at our disposal – diplomatic, economic, military, political, legal, and cultural – picking the right tool, or combination of tools, for each situation’ (Clinton 2009). meaning that all means of influence – economic, diplomatic, cultural and military – should be used to advance US interests, began to guide US grand strategy. It was a critique to the Bush administration, whose main focus was placed on the military aspect of hegemony (Biegon 2017Biegon, R. 2017. US Power in Latin America. Renewing Hegemony. New York: Routledge.).

There was also a rhetoric on partnership, highlighted especially by the president, and a new opening to Latin American demands. The normalization of relations with Cuba in 2014 was the most explicit event deemed to portray the USA as not being unresponsive to Latin American requests, and conceived as a way of improving the relations with the entire hemisphere and change its corroded image (The White House 2015aThe White House. 2015a. ‘National Security Strategy.’ Washington, DC.). In addition, another rhetoric emphasized multilateralism and the formation of horizontal partnerships in the region.

Kassab and Rossen (2016) point out that Obama aimed to rebuild US soft power in the Hemisphere, especially diminished during the first Bush administration. This change involved new tactics, but the same goal remained: the Bush and Obama administrations sought to maintain their relative position as a great power (Kassab and Rosen 2016Kassab, H S and J D Rosen. 2016. The Obama Doctrine in the Americas: Security in the Americas in the Twenty-First Century. Lanham: Lexington Books.). In general, the White House sought not to directly antagonize the countries of the Bolivarian axis, attributing a low profile to the issue.

However, the pressing on the left-leaning governments was not absent. In 2009, the United States adopted an ambiguous position after a coup d’état that removed Manuel Zelaya from power in Honduras. It refrained from naming it a military coup and accepted the status quo after elections were held. That event wore out the euphoria that had followed the Obama election. Moreover, in 2015, the United States administration declared Venezuela as an ‘unusual and extraordinary threat’ (The White House 2015bThe White House. 2015b. ‘Venezuela Executive Order.’ Washington, DC.). This was the first step to initiate a process of imposing sanctions to the country.

In summary, US security assistance and military presence remained constant in the region in the post 9/11 period, albeit concentrated in the Andes. Increasing challenges and obstacles were posed to US hegemony, but its influence remained relevant in terms of military training and security assistance. Therefore, US policymakers did not neglect the region. In the next section, the stance of the leading military agency dedicated to this region will be analysed, to clarify the US position in greater depth.

The SOUTHCOM perception of threats

The SOUTHCOM is the unified command responsible for the military operations in the Americas, south of Mexico. It is the leading and permanent institution dedicated to promoting military-to-military cooperation between the USA and Latin America. Its vision advances the position of being a ‘trustworthy partner enabling a networked defense approach, grounded in mutual respect and cooperative security to promote regional stability while advancing our shared interests’ (USA Southern Command n.d.USA Southern Command. 2008. ‘U.S. Southern Command 2008 Posture Statement.’ Washington, DC.). Its operations are usually low-profile, yet still relevant to the region, as the SOUTHCOM is a major source of international training for Latin American armed forces.

The SOUTHCOM commander makes annual speeches to the United States Congress Armed Services Committee on the brink of its budget definition. Through these discourses, it is possible to identify the perceived threats coming from the hemisphere in different periods (Table 1). During the Bush administration, drug trafficking and terrorism were constantly identified as security threats and, since 2002, the commanders began to describe their activities as a supporting role to the global war on terror. SOUTHCOM leaders saw their mission as promoting cooperation and developing the national capabilities of Latin American countries to counter these transnational threats (USA Southern Command 2002USA Southern Command. 2002. ‘Posture Statement of Major General Gary D. Speer, United States Army Acting Commander In Chief United States Southern Command Before.’ Washington, DC., 2005, 2007).

SOUTHCOM commanders perceived connections between organized crime and terrorism, maintaining that drug traffickers could promote logistical and financial support to terrorists (USA Southern Command 2004USA Southern Command. 2004. ‘Testimony of General James T. Hill, Commander, United States Southern Command.’ Washington, DC.). In South America, there were two focal points: the Andes – especially Colombia and Ecuador – and the Triple Frontier between Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. In the first case, the threat was perceived as coming from domestic organisations. Both the Colombian FARC and the Peruvian Sendero Luminoso insurgencies, and the Colombian AUC paramilitaries were included in the Department of State’s terrorist list.

In the Triple Frontier area, the SOUTHCOM identified sources of financing to Middle East-based terrorist organisations, mentioning the Hezbollah and the Hamas. The US military command also recognized connections between organised crime and terrorism financing and was concerned about the possibility of this area becoming a safe haven for international terrorism (USA Southern Command 2004USA Southern Command. 2004. ‘Testimony of General James T. Hill, Commander, United States Southern Command.’ Washington, DC., 2008). A multilateral mechanism named 3+1 composed by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and the USA was created to counter that threat.

US representatives also recommended measures to counter money laundering and promote bank safety. Moreover, crime and terrorist organisations were seen as complex threats that hence demanded interagency operations, with the military acting in a supporting role. The SOUTHCOM commanders’ speeches also highlighted that Latin America’s greatest concerns and problems were economic and social in nature, and that, as such, actions involving the whole government were needed (USA Southern Command 2006USA Southern Command. 2006. ‘Posture Statement Of General Bantz J. Craddock, United States Army Commander, United States Southern Command.’ Washington, DC.). SOUTHCOM commanders also stressed the need for cooperation between military officials and police officers to combat transnational threats.

The military was seen as a significant, in some cases necessary, but not as the leading agency incumbent of combatting organised crime. Nevertheless, the USA encouraged the presence of the military in the fight against drug trafficking and insurgencies, by identifying drug trafficking and violent groups as security issues and by the corresponding increase in assistance implemented by the Department of Defence (Isacson 2015Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108.; Tokatlian 2015). Isacson (2015)Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108. remarks that the fight against drug trafficking permitted the maintenance of close ties between the US military and its Latin American counterparts following the end of the Cold War. The author also highlights the differences in the roles assumed by US military personnel, whose involvement in internal affairs is restricted, despite the encouragement to engage the Latin American military in internal security. Drug criminalization and the repressive model to tackle traffic, which considers drugs as a security rather than a social or health problem, is a vision fostered by the United States that has historically promoted an international prohibitionist regime (Silva 2013Silva, L L da. 2013. A questão das drogas nas relações internacionais : uma perspectiva brasileira. Brasilia: FUNAG.).

This approach to combatting organized crime, accepting a role for the military and revealing a hard-line policy to combat drug trafficking generated divisions between the United States and Latin America. Scholars and human rights movements underscored the failure of the model, highlighting its negative consequences to the human rights fields and its inefficiency due to the low impact on the quantity or price of drugs arriving in the United States (Isacson 2005Isacson, A. 2005. ‘Closing the “Seams”: U.S. Security Policy in the Americas.’ NACLA Report on the Americas 38: 13–17.; Buxton 2011Buxton, J. 2011. ‘Forward into History: Understanding Obama’s Latin American Policy.’ Latin American Perspectives 38 (4): 29-45.; Rodrigues 2012Rodrigues, T. 2012. ‘Narcotráfico e militarização nas Américas: vício de guerra.’ Contexto Internacional 34 (1): 9-41.).

Notwithstanding, the repressive model is supported by police and military forces, in the USA and Latin America alike. In the assessment of Tokatlian (2015), although the pressure exercised by the United States is a necessary condition, it is not enough to explain the adoption and maintenance of the prohibitionist model throughout Latin America. According to him, the Latin American military and police indeed became ‘addicted to the drug war’ (Tokatlian 2015: 71).

The Obama administration recognized that the threats originating from Latin America did not demand military responses. According to the Defense Strategy for the Western Hemisphere released in 2012:

The use of the military to perform civil law enforcement cannot be a long-term solution. However, as other U.S. security cooperation efforts work to build the capacity of civil authorities and partner nation law enforcement, DoD will continue to support defense partners to give them the best opportunity to succeed in bridging these gaps (Department of Defense [USA] 2012Department of Defense [USA]. 2012. ‘Western Hemisphere Defense Policy Statement.’ Washington, DC: Department of Defense.).

The SOUTHCOM saw its mission as a support for measures to contain and detain transnational organised crime and violence in Latin America. The commanders defined their actions as integrally based on an interagency model, highlighting the need for cross-disciplinary solutions, including mechanisms and agencies at all levels of government (USA Southern Command 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013). The agency advocated for expanding the capacities of law enforcement agencies that were identified as more appropriate to deal with organized crime. As partner agencies in the fight against transnational threats, SOUTHCOM commanders cited the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the US Departments of State, the US Treasury, the US Justice and Homeland Security, the US Coast Guard, the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). SOUTHCOM commanders acknowledged that the threats identified in South America were not military in nature, but also argued that the US military had a role to play. Conversely, as stated by Isacson:

When elected civilian leaders in the region propose deploying the military into the streets to fight drug-funded gangs or organized crime, U.S. officials are, on balance, willing to make contributions from counterdrug aid accounts. U.S. military assistance programs in Latin America, then, still encourage militaries to take on internal security roles […] (Isacson 2015Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108.: 101).

Therefore, there has been no substantive change between the Bush and Obama administrations regarding the use of the armed forces to combat crime and terrorism. The identification of poverty and inequality as causes of violence did not necessarily lead to recommendations of social policies with the objective of resolving such issues in a structural way.

In addition to terrorism and drug trafficking, the existence of developmentalist governments, defined by the USA as populists, was increasingly perceived as a challenge, being identified as a threat in 2004 (USA Southern Command 2004USA Southern Command. 2004. ‘Testimony of General James T. Hill, Commander, United States Southern Command.’ Washington, DC.). The Commanders perceived ‘populism’ both as a risk to democracy and as a consequence of the economic and social challenges in Latin America. SOUTHCOM commanders perceived the presence of Latin American left-leaning governments as problematic, especially because they threatened US military-to-military relations. Since 2005, these governments became a challenging trend, when the Venezuelan government began to cut ties with US military and Evo Morales (2006) and Rafael Correa (2007) came to power in Bolivia and Ecuador, respectively (USA Southern Command 2006USA Southern Command. 2006. ‘Posture Statement Of General Bantz J. Craddock, United States Army Commander, United States Southern Command.’ Washington, DC., 2008). In light of this scenario, the SOUTHCOM leadership sought to maintain consistent relations among the military in an adverse political context, keeping the invitations to military exercises and training open.

The speeches of SOUTHCOM commander to the US Congress show changes in emphasis regarding perceived threats from the region. During the Bush years, terrorism encompassed other internal security issues and tended to be related to terrorism and crime. During the Obama administration, transnational organised crime was highlighted as the main threat and, in spite of terrorism still being present, was not usually the first issue to be mentioned by the commanders. In addition, the tendency to see the left-leaning governments through security lenses was partially reversed and the mention of radical populism as a threat did not occur under his administration. Nevertheless, the advances of foreign powers were perceived with increasing concern.

The incipient yet gradually crescent military cooperation between those extra-hemispheric countries and the Bolivarian governments was seen with greater concern, especially since 2010 (Table 1). Since that year, the advances made by foreign powers in the region was highlighted every year by SOUTHCOM commanders during their speeches on Capitol Hill. This trend shows that the United States military was frequently perceiving the Chinese and Russian regional advances with greater concerns.

US strategy in face of external powers advances in South America

Sino-Latin American trade increased by 22 times between 2000 and 2013. There was also an expansion of Chinese investments in Latin America, through foreign direct investment and loans made by its policy banks, the Chinese Development Bank and the China Export and Import Bank (CEPAL 2018CEPAL. 2018. Explorando nuevos espacios de cooperación entre América Latina y el Caribe y China. Santiago.). This process was accompanied by an increase in high-level visits by Chinese representatives to Latin America that expanded political and diplomatic ties. By 2007, China had designated four countries as strategic partners: Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, and Mexico (Li 2007Li, H. 2007. ‘China’s growing interest in Latin America and its implications China’s Growing Interest in Latin America and Its Implications.’ Journal of Strategic Studies 30 (4-5): 833-862.).

US policymakers closely monitored the expansion of China-Latin America ties. In 2005, the Senate held a hearing on the topic entitled ‘Challenge or Opportunity? China’s role in Latin America.’ Senator Norm Coleman (Republican; Minnesota) chaired the meeting and highlighted topics such as the increase in Chinese trade, investment, and high-ranking official visits, as well as the Latin American recognition of China as a market economy. The senator stressed the advance in military-to-military relations through the establishment of exchange programs, visits by high-ranking Chinese military personnel, and the sending of Chinese blue helmets to Haiti (Senate [USA] 2005).

At the occasion, Coleman also inquired about the opportunities that could arise from the Chinese involvement and whether the USA could influence its regional presence (Senate [USA] 2005: 3). The response from the Executive representatives who participated in the hearing was positive. Assistant Deputy Secretary of State Charles Shapiro stated that there were issues of complementarity with China, and that the United States would seek cooperation while continuing to monitor the arms sales and Chinese military contacts with Latin American countries.

Statements delivered by Assistant Deputy Defense Secretary Roger Pardo-Maurer were similar, pointing out that China responded to the US ‘sensitivities’ in the Western Hemisphere and highlighting the existence of areas in which cooperation was possible (Senate [USA] 2005: 13). Pardo-Maurer also stressed that China was not a direct threat and that it would not seek to establish a permanent military regional presence or compete geopolitically with the USA. Nonetheless, his discourse emphasized the possible risks and the need to monitor Chinese activities (Senate [USA] 2005: 37). Officials from the Departments of Defence and from the Department of State did not downplay the relevance of China-Latin America contacts, but instead argued for cooperation. There was a delicate balance between emphasizing that the government should monitor the Chinese presence even if it did not perceive it as a threat.

On 14 April 2006, the first meeting of a US-China dialogue sub-mechanism about the country’s presence in Latin America took place. The dialogue brought together representatives of the State Department and of the Republic of China’s People’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and aimed to setback competitive trends between the USA and the emerging power, covering various dimensions of their relationship.

The mechanism aimed at increasing transparency and avoiding miscalculations (Paz 2012Paz, G S. 2012. ‘China, United States and Hegemonic Challenge in Latin America: An Overview and Some Lessons from Previous Instances of Hegemonic Challenge in the Region.’ The China Quarterly (209): 18-34.). For the Chinese, it was important to uphold its peaceful intentions in Latin America and deny the existence of geopolitical ambitions (Department of State [USA] 2006Department of State [USA]. Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. 2006. ‘U.S.-China Latin America Subdialogue: A/S Shannon Discussions with DG Zeng Gang.’ Washington, DC: ). For the United States, it was functional to influence Chinese action in the Western Hemisphere (Department of State [USA] 2006, 2008Department of State [USA]. Bureau of Western Hemisphere . 2008. ‘A/S Shannon leads U.S.-China Latin America Subdialogue.’ Washington, DC: Wikileaks.).

Hence, US policymakers did not perceive the China-Latin America relationship as threatening during the two Bush administrations. The USA understood that China would seek regional stability because of its regional investments. Paz (2012: 32) affirmed that the USA ‘has attracted China to the dialogue with the intention not to stop or contain all Chinese initiatives in the region but to shape them.’ The Obama administration continued the US-China dialogues on Latin America in its early years, but discontinued them throughout the course of the administration9 9 Even though answering why the mechanism was discontinued would require more empirical research – and documents that are still unavailable, it is possible to speculate that the reason relates to the US growing perception of China as a challenge or a threat. (Shannon 2019).

In addition to China, the USA was also concerned about the presence of Russia and Iran in the hemisphere. There was no institutionalized mechanism concerning Russia, but in December 2008, the US government held consultations with Russian representatives on ways of pursuing a joint constructive engagement in Latin America. According to a State Department telegram, consultations could be useful for establishing common interests and as a way to encourage Russian responsible behaviour towards the region (Department of State [USA] 2009Department of State [USA]. Bureau of Western Hemisphere . 2009. ‘A/S Shannon and DMF Ryabkov discuss Russia-Latin American Relations’. Washington, D.C.: Wikileaks, p. 9.). State Department representatives understood that Latin America was not a priority for Russia and that the country would not do much to support anti-Western trends. The US concern was primarily motivated by the sale of weapons, especially after Venezuela announced the decision to buy Russian Sukhoi fighters to replace its American F-16 fleet (Ellis 2015Ellis, R E. 2015. The New Russian Engagement With Latin America: Strategic Position, Commerce, And Dreams of the Past. Carlisle Barracks: United States Army War College Press. At https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/2345.pdf [Accessed on 13 April 2020].

https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/...

; Ciccarillo 2016Ciccarillo, S. 2016. ‘The Russia-Latin America Nexus: Realism in the 21st Century.’ Review of International Studies (47): 25-45.).

Finally, Iran is a particular case, since the country’s more limited capabilities restricts its scope of activity in Latin America. The country does not export weapons systems nor offers military training to Latin America. Even so, its advances provoked extraordinary distrust since they were perceived to be related to the presence of cells or support for Hezbollah in the region (USA Southern Command 2008USA Southern Command. 2008. ‘U.S. Southern Command 2008 Posture Statement.’ Washington, DC.).

From a long-term perspective and considering the possibility of offering alternative models and partnerships to the region, Russia and China stand out as major challenges for the USA. The success of the Chinese development model and the loans provided to the countries of the region enables them to adopt economic policies that depart from neoliberalism (Kaplan 2016). Russia presented itself as an alternative in the areas of energy and defence, providing an alternative to the purchase of US weapons.

The annual speeches delivered by SOUTHCOM commanders to the Senate are an indication of the growing concern about these country’s expansion in Latin America. In every year since 2010, China has been highlighted as a variable in the regional strategic scenario and as a challenge to the US influence and position as a ‘partner of choice’ in defence. Usually, Iran and Russia also appeared as challenges (Table 1). SOUTHCOM commanders urged the US government to expand its engagement with the region, or risk losing its regional hegemony (USA Southern Command 2013USA Southern Command. 2013. ‘Posture statement of general John F. Kelly, united states southern command before the 113th Congress.’ Washington, DC., 2014). The commanders pointed out the following as points of concern: the increased cooperation on military issues between these countries, and the proximity between them and South American left-leaning governments, especially Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador. They perceived China and Russia as a source of support for such governments, in detriment of the US regional influence.

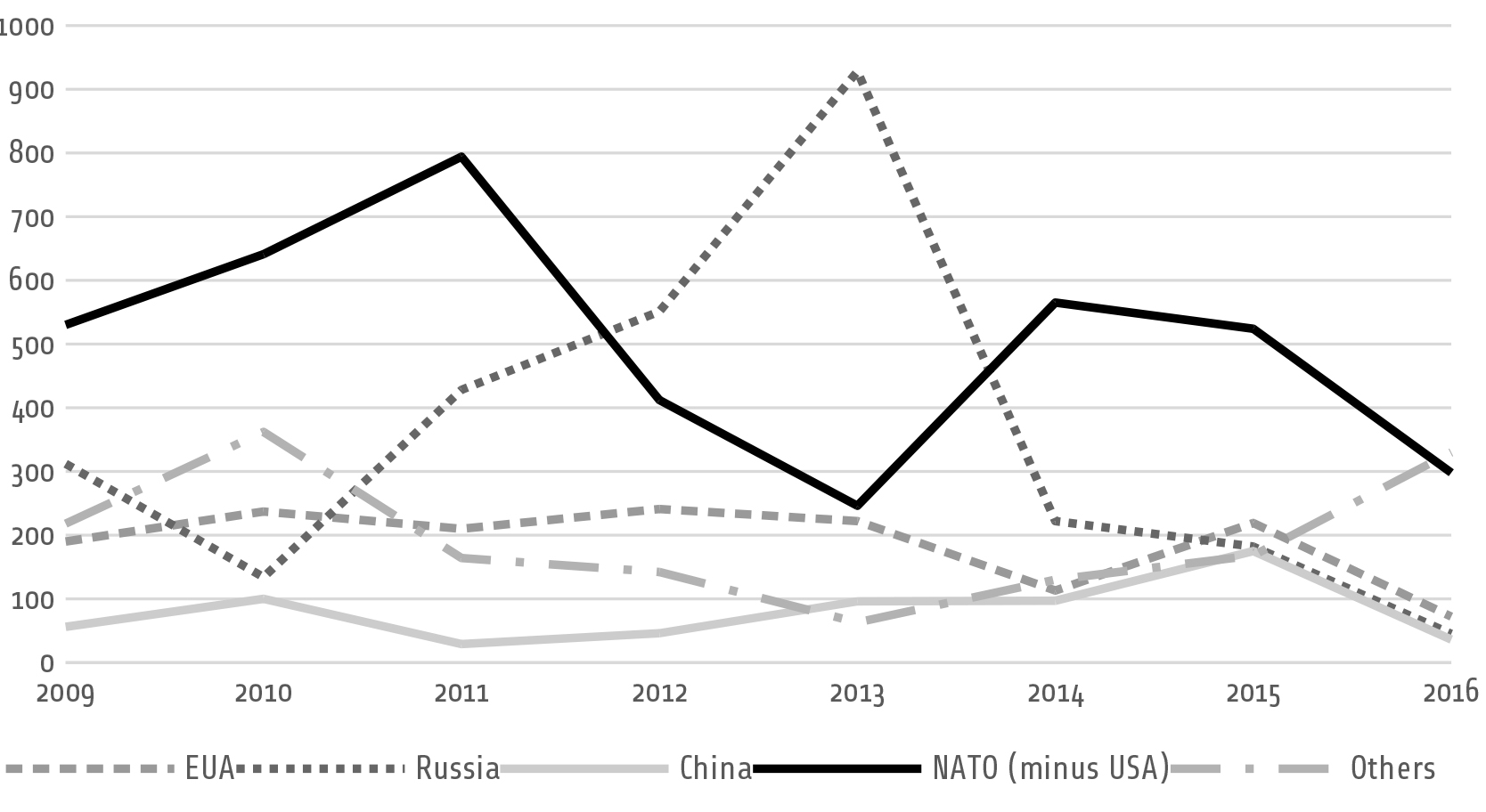

After the consideration of the perspective presented by SOUTHCOM commanders, it is worth asking what the real extent of Chinese and Russian military involvement in the region was. Military contacts between China and Latin America are limited and are not the main component in the relationship, since economic related issues are the predominant facet (Watson 2013Watson, C. 2013. ‘China’s use of the Military Instrument in Latin America : Not Yet the Biggest Stick.’ Journal of International Affairs 66 (2): 101-111.). Data on the transfer of weapons systems to South America in the period from 2001 to 2016 offers interesting information to investigate this issue. There was an increase in exports of Chinese weapons systems to South America that, albeit in a discreet way, did not approach the volume of arms exported by NATO countries. Conversely, Russia has become an important player in this area, especially since 2005 (Graph 5).

Considering South American countries in the period from 2001 to 2008, Russia exported weapons systems to Colombia, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Peru yet on a small scale. Data on Russian arms exports to the largest South American economies reveals a concentration of exports to Venezuela (SIPRI 2019). Colombia imported weapons especially from the United States and Argentina, whilst Brazil had a more diversified list of suppliers. During the Obama administrations, Russian arms sales to the region grew considerably. Russia overtook Europe as the largest supplier of weapons systems between 2012 and 2013 (Graph 6). Russian sales to Venezuela were more expressive, but Colombia, Brazil and Argentina also bought Russian weapon systems. Most of the weapons purchased by Brazil were European and, in the cases of Colombia and Argentina, they came primarily from the USA (Milani 2019Milani, L. 2019. ‘A Argentina e o Brasil frente aos Estados Unidos: clientelismo e autonomia no campo da segurança internacional.’ PhD Thesis. Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Brazil.; SIPRI 2019).

To sum up, the USA’s response to external challenges in Latin America was a low-profile one; however, there was growing concern about it. The Obama government sought not to attribute a high profile to the expansion of external actors in Latin America, avoiding an openly interventionist position. As previously mentioned, during a speech at the OAS in 2013, then-Secretary of State John Kerry (2013-2017) declared the Monroe Doctrine ended. This narrative attributed a benign expression to the US strategy in face of the connections between Latin American leaders and powers from other latitudes.

By contrast, the hearings of SOUTHCOM commanders suggest that there was indeed a rising concern, even if not stressed by the President and by the Departments of Defense and State. Moreover, how the USA perceives foreign presence in Latin America depends essentially on who are the extra-regional actors and what the characteristics of their relationship with the USA in a more general level are. During the Bush and Obama governments, the China-US relationship was institutionalized through formal diplomatic mechanisms and marked by interdependence, cooperation, and rivalry. US-China relations were critical to the international system and preserving stability was an objective pursued by both countries. China promoted substantive but low-profile incursions in Latin America, avoiding antagonizing the USA. China-Latin American relations were relevant to China’s global strategy, but they were not vital, remaining subordinated to the country’s objective of maintaining good relations with the Western power (Li 2007Li, H. 2007. ‘China’s growing interest in Latin America and its implications China’s Growing Interest in Latin America and Its Implications.’ Journal of Strategic Studies 30 (4-5): 833-862.; USA Southern Command 2011USA Southern Command. 2011. ‘Posture statement of General Gouglas M. Fraser, United States Air Force Commander, United States Southern Command.’ Washington, DC., 2014).

For Russia, approaching Latin America was part of the strategy of promoting a multipolar world and it resonated with the diplomatic discourse of several countries in the region (Ciccarillo 2016Ciccarillo, S. 2016. ‘The Russia-Latin America Nexus: Realism in the 21st Century.’ Review of International Studies (47): 25-45.). Not only Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia underlined their favourability to a multipolar world. Brazil and Argentina also did so. These South American countries shared a common vision and interests with Russia, given that the persistence of a world marked by US primacy did not appeal to them. Russian representatives saw their presence in Latin America as part of a vision of a changing world, increasingly marked by the decentralization of power.

Final remarks

US security policy to South America and the SOUTHCOM perception of threats show that the 9/11 terrorist attacks was not a turning point to the US Western Hemisphere strategy that marked the beginning of an allegedly neglect era. The USA identified the region as part of the war on terror, with a focus on the Colombia internal conflict and on the Triple Border between Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. Data shows that the unease was greater when it came to the Andes, region to which most funds were directed. The partnership with Colombia gained relevance and became a counterpoint to the Venezuelan anti-Americanism.

US assistance and foreign policy encouraged an increasing militarisation of the Latin American response to issues such as narco-trafficking and organised crime. The process was accompanied by a greater influence of the SOUTHCOM in the US regional policy. Moreover, the USA has reacted to the advances by external actors, mainly through the SOUTHCOM. Even though the Department of State and the President sought to express a benign position towards the issue, there was rising concern, expressed by the military at the congressional hearings.

Therefore, the idea of a ‘benign neglect’ that would have opened space for regionalism and for the quest for South American autonomy is not an appropriate assumption. On the one hand, the USA sought to strengthen relations with certain South American governments; on the other, it sought to neutralize the sources of resistance to its leadership. In continuity with the past, the US regional strategy did not detach itself from global issues, and the identified threats stemmed from issues that related to regional instability and the presence of external actors (Pecequilo 2011Pecequilo, C. 2011. A Política Externa dos Estados Unidos. Continuidade ou Mudança? Porto Alegre: Editora UFRGS.).

This dynamic suggests that the South American quest for autonomy was not fomented by the absence of a US strategy. The investigation confirm that US hegemony was increasingly challenged during the Bush and Obama administrations, but that the USA’s declining influence was not caused by its neglect. In other words, the changes in Inter-American relations were external, rather than internal, to the US decision-making process. These changes were connected to the Latin American countries’ quest for autonomy and to an international environment that became more permissive due to the Chinese and Russian growth.

Since 2015, relevant changes have encompassed the region and the left-leaning cycle has lost its impetus. As of 2020, the only country in South America which has not promoted a realignment with the USA is Venezuela – although the return of the Kirchnerism in Argentina may lead to a renewed quest for autonomy in the country, as well as the comeback of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) in Bolivia. The relations between Brazil and the USA have significantly strengthened, reversing Brazil’s previous quest for autonomy. The current scenario is also more a reflection of South American domestic politics than a result of the US foreign policy in and of itself. This does not mean that there is no US influence. The relations of the USA with the military and public security agencies are a source of influence, especially in promoting certain themes such as the fight against corruption and money laundering. Nevertheless, it would be difficult to sustain the argument that it was the US foreign policy that caused this regional political trend to exist in the first place.

With regard to the US foreign policy during the Donald Trump administration, differences also come to the forefront. Migration and drug trafficking from the region were seen with the greatest concern by the Trump administration, yet there is a more explicit concern over the advances of great powers in the region. Nowadays, the challenge is highlighted not only by the SOUTHCOM commanders but also by the Secretaries of Defense and of State. The United States’ attention to the region is more explicit; however, it is still concentrated and reactive to crisis. Its main preoccupation constitutes the attempt to produce regime change in Venezuela, be it through sanctions, humanitarian aid, or by providing support to the self-proclaimed presidency of Juan Guiadó. The issue has spilt over to the bilateral relations with other countries in the region, becoming imperative in all high-ranking bilateral official meetings. Nevertheless, the resilience of the Nicolas Maduro government is the main evidence that US actions – short of military interventions – are not omnipotent and do not determine the regional future.

Notes

-

1

Hegemony, as discussed by a relevant segment of the literature, can be defined as the pre-eminence in economic and military fields, which underpin the leadership and control exercised by great powers. Notwithstanding, this conception has limits, since it precludes the analysis of the ideational dimension. It is also possible and productive to define hegemony on neo-Gramscian terms, as outlined by Cox (1981), as a fit between power, ideas, and institutions articulated by the hegemon to ensure control of the international order. The hegemon maintains its control over the periphery through material power and consensus, manufactured through ideas and institutions. In this article, I focus on the material aspect of hegemony, but the sphere of ideas should also be investigated in further analysis.

-

2

In this article, I start with the premise that US influence in South America is distinct, in some respects, from its involvement in North and Central America (Teixeira 2012Teixeira, C G P. 2012. Brasil, The United States and the South American Subsystem. Regional Politics and the Absent Empire. Lanham: Lexingtin Books.). South America is further away and has ampler autonomy, especially greater countries such as Brazil and Argentina. US involvement was also distinct among South American sub regions, since the Andes was perceived as more unstable and as the biggest source of threats. However, the literature tends to treat Latin America as a whole, the US planning is dedicated to the entire Hemisphere and the SOUTHCOM is responsible for all the American regions south of Mexico. Therefore, especially in the literature review, it will be necessary to make mentions to Latin America, even when the focus is South America.

-

3

Foreign Policy is hereby understood as ‘the policies and actions of national governments oriented toward the external world outside their own political jurisdictions’ (Caporaso 1986: 9). In this sense, ‘[m]ilitary policies are framed and implemented in the context of a state’s foreign policy’ (Caporaso et al1986: 11).

-

4

In the 1990s, a new conception of autonomy was formulated, especially by Escudé (1992)Escudé, C. 1992. Realismo periférico: Bases teóricas para una nueva política exterior argentina. Buenos Aires: Planeta. and Russell and Tokatlian (1990)Russell, R and J G Tokatlian. 2001. ‘De la autonomia antagonica a la autonomia relacional una mirada teorica desde el Cono Sur.’ PostData (7): 71-92.. Escudé understood the exercise of autonomy was compatible with alignment to the great power, especially on the political-strategic dimensions, and Russel and Tokatlian argued it was consonant with the accession into international regimes. For a literature review, see the article ‘Cooperación dependiente asociada’ written by Arlene Ticker and Mateo Morales (2015).

-

5

The militarisation of US foreign policy is not restricted to Latin America. For a discussion on the subject, see the book ‘Mission Creep: The Militarisation of U.S. Foreign Policy?’ by Gordon Adams and Shoon Murray.

-

6

Usually, the funding was directed through the Department of State, even in cases in which the Department of Defense was responsible for its implementation.

-

7

Although USAID has its own aid database, it does not count on the assistance delivered by the Department of Defense. That is the reason why data here comes from the Security Assistance Monitor database.

-

8

Originally coined by Joseph Nye, the idea of smart power was highlighted by Hillary Clinton on her nomination speech before the Congress. According to her, ‘[…] we must use what has been called ‘smart power,’ the full range of tools at our disposal – diplomatic, economic, military, political, legal, and cultural – picking the right tool, or combination of tools, for each situation’ (Clinton 2009Clinton, H R. 2009. ‘Nomination of Hillary R. Clinton to be Secretary of State.’At https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg54615/html/CHRG-111shrg54615.htm [Accessed on 29 June 2020].

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG... ). -

9

Even though answering why the mechanism was discontinued would require more empirical research – and documents that are still unavailable, it is possible to speculate that the reason relates to the US growing perception of China as a challenge or a threat.

Acknowledgements

This article is a product of the author’s doctoral research, therefore, she would like to thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), for funding it through grants 2017/00661-8 and 2018/03231-7. She also wants to thank Prof. Sebatião Velasco e Cruz, who was her supervisor, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

- Adams, G and S Murray. 2014. Mission Creep: The Militarization of US Foreign Policy? Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Bandeira, L A M. 2010. Brasil, Argentina e Estados Unidos. Conflito e Integração na América do Sul. 3rd edition. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Battaglino, J. 2012. ‘Defence in a Post-Hegemonic Regional Agenda: The Case of The South American Defence Council.’ In P Riggirozzi and D Tussie (eds), The Rise of Posthegemonic Regionalism: The Case of Latin America. New York: Springer.

- Biegon, R. 2017. US Power in Latin America. Renewing Hegemony. New York: Routledge.

- Brenner, P and E Hershberg. 2013. ‘Washington e a Ordem Hemisférica: Explicações para a Continuidade em meio à Mudança.’Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política (90): 37-63.

- Briceño Ruiz, J. 2013. ‘Ejes y modelos en la etapa actual de la integración económica regional en América Latina.’ Estudios Internacionales (175): 9-39.

- Buxton, J. 2011. ‘Forward into History: Understanding Obama’s Latin American Policy.’ Latin American Perspectives 38 (4): 29-45.

- Caporaso, J, C Hermann, C Kegley, J Rosenau, D Zinnes. 1986. ‘The Comparative Study of Foreign Policy: Perspectives on the Future.’ Paper presented at the 27th Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association. Anaheim, USA, 25-29 March.

- CEPAL. 2018. Explorando nuevos espacios de cooperación entre América Latina y el Caribe y China. Santiago.

- Center for International Policy. 2019. Security Assistance Monitor. At https://securityassistance.org/ [Accessed on 13 April 2020].

» https://securityassistance.org/ - Ciccarillo, S. 2016. ‘The Russia-Latin America Nexus: Realism in the 21st Century.’ Review of International Studies (47): 25-45.

- Clinton, H R. 2009. ‘Nomination of Hillary R. Clinton to be Secretary of State.’At https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg54615/html/CHRG-111shrg54615.htm [Accessed on 29 June 2020].

» https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg54615/html/CHRG-111shrg54615.htm - Crandall, R. 2011. ‘The Post-American Hemisphere. Power and Politics in an Autonomous Latin America.’ Foreign Affairs 9 (3): 83-95.

- Department of Defense [USA]. 2012. ‘Western Hemisphere Defense Policy Statement.’ Washington, DC: Department of Defense.

- Department of State [USA]. Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. 2006. ‘U.S.-China Latin America Subdialogue: A/S Shannon Discussions with DG Zeng Gang.’ Washington, DC:

- Department of State [USA]. Bureau of Western Hemisphere . 2008. ‘A/S Shannon leads U.S.-China Latin America Subdialogue.’ Washington, DC: Wikileaks.

- Department of State [USA]. Bureau of Western Hemisphere . 2009. ‘A/S Shannon and DMF Ryabkov discuss Russia-Latin American Relations’. Washington, D.C.: Wikileaks, p. 9.

- Drezner, S. 2015. ‘A Post-Hegemonic Paradise in Latin America?’ Americas Quartely [online], 3 February.

- Ellis, R E. 2015. The New Russian Engagement With Latin America: Strategic Position, Commerce, And Dreams of the Past. Carlisle Barracks: United States Army War College Press. At https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/2345.pdf [Accessed on 13 April 2020].

» https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/2345.pdf - Emerson, R G. 2010. ‘Radical Neglect? The “War on Terror” and Latin America.’ Latin American Politics and Society 52 (1): 33-62.

- Escudé, C. 1992. Realismo periférico: Bases teóricas para una nueva política exterior argentina. Buenos Aires: Planeta.

- Gallagher, K P and M Myers. 2019. “China-Latin America Finance Database.” Washington: Inter-American Dialogue.

- Hakim, P. 2006. ‘Is Washington Losing Latin America?’ Foreign Affairs 85 (1): 39-53.

- Isacson, A. 2005. ‘Closing the “Seams”: U.S. Security Policy in the Americas.’ NACLA Report on the Americas 38: 13–17.

- Isacson, A. 2015. ‘Mission Creep: The US Military’s Counterdrug Role in the Americas.’ In B M B Rosen and J D Rosen (eds), Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime and Violence in the Americas Today. Miami: University Press of Florida, pp. 87-108.

- Kassab, H S and J D Rosen. 2016. The Obama Doctrine in the Americas: Security in the Americas in the Twenty-First Century. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Kjonnerod, E. 1992. Evolving U.S. Strategy for Latin America and the Caribbean: Mutual Hemispheric Concerns and Opportunities for the 1990s. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press.

- Jaguaribe, H. 1979. ‘Autonomía periférica y hegemonía céntrica.’ Estudios Internacionales 12 (46): 91-130.

- Leogrande, W M. 2007. ‘A Poverty of Imagination: George W. Bush’s Policy in Latin America.’ Journal of Latin American Studies 39 (2): 355-385.

- Li, H. 2007. ‘China’s growing interest in Latin America and its implications China’s Growing Interest in Latin America and Its Implications.’ Journal of Strategic Studies 30 (4-5): 833-862.

- Lima, M R S de. 2013. ‘Relações interamericanas: a nova agenda sul-americana e o Brasil.’ Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política (90): 167-201.

- Long, T. 2015. Latin America Confronts the US. Asymmetry and Influence. New York: Cambridge University Press.