ABSTRACT

Purpose

To compare the functional use of verbs and nouns by Brazilian Portuguese-speaking children with language impairment (LI) and to verify whether their use of these word classes is different from that of children with typical language development (TLD). This study also aimed to compare the use of each verb type between groups.

Methods

Participants were 80 preschool children, 20 of them diagnosed with LI and 60 with TLD. The age ranges of participants were 3 to 6 years for children with LI and 2 to 4 years for children with TLD. Individuals were paired based on their expressive language age. Ludic interaction was used to elicit the speech sample from which nouns and verbs were selected from spontaneous speech. All nouns and verbs were tabulated and verbs were classified.

Results

Preschoolers with LI use verbs more often than nouns in their production of spontaneous speech. The use of nouns presented no difference between the groups, but verb use frequency was higher in children with LI for the 3-year-old subgroup. The verbs most frequently used by children with LI were copula, intransitive, and transitive direct. Comparison between the groups revealed few differences regarding the use of transitive direct, bitransitive, and copular verbs. Only transitive circumstantial verbs were more often used by children with TLD at all ages.

Conclusion

The use of nouns and verbs by children with LI complies with the typical development standard, but it occurs more slowly. The use of verbs with fewer complements is predominant in these children.

Keywords:

Child Language; Language Disorders; Vocabulary; Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences; Language Development

RESUMO

Objetivos

Comparar o uso funcional de verbos e substantivos por crianças com alterações específicas de linguagem (AEL) falantes do Português Brasileiro e investigar se o uso destes tipos de palavras difere das crianças em desenvolvimento típico de linguagem (DTL). Além disso, comparar a utilização de cada tipo de verbo entre os grupos.

Método

Participaram do estudo 80 pré-escolares, 20 com AEL e 60 com DTL. A faixa etária dos sujeitos com AEL variou entre 3 e 6 anos, e do grupo com DTL variou entre 2 e 4 anos. O pareamento dos sujeitos foi baseado na idade linguística expressiva. A amostra de fala foi eliciada por meio de interação lúdica, e dessa amostra foram selecionados os substantivos e verbos produzidos.

Resultados

Os pré-escolares com AEL utilizaram mais verbos do que substantivos em fala espontânea. O uso de substantivos não diferiu entre os grupos, mas nos verbos o subgrupo de 3 anos com AEL os utilizou com mais frequência que seus pares. Os tipos de verbos mais utilizados por sujeitos com AEL foram de ligação, intransitivo e transitivo direto. A comparação entre os grupos neste aspecto diferiu pontualmente para os verbos transitivo direto, bitransitivo e de ligação; apenas o verbo transitivo circunstancial foi mais utilizado pelos sujeitos em DTL para todas as idades.

Conclusão

O uso de substantivos e verbos em crianças com AEL respeita o padrão do desenvolvimento típico, mas ocorre de forma mais lenta. O uso de verbos com menos complementos é predominante nesta população.

Descritores:

Linguagem Infantil; Transtornos da Linguagem; Vocabulário; Fonoaudiologia; Desenvolvimento da Linguagem

INTRODUCTION

Language acquisition occurs from the interaction between the child and the surrounding environment. Children use their cognitive and social skills to categorize, organize, and combine everything they learn separately through the stimuli they receive in the family environment. Children produce their first words when they are approximately one year old(11 Gândara JP. Aquisição lexical no desenvolvimento normal e alterado de linguagem: um estudo experimental. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2008.).

Learning a word is a multifactorial process which begins with the association between a phonetic input and a corresponding action or object in the environment. This first association is named fast mapping, and it involves an incomplete representation of the word. The continuous exposition to this word creates a robust association, which occurs in the slow mapping phase(22 Alt M, Suddarth R. Learning novel words: detail and vulnerability of initial representations for children with specific language impairment and typically developing peers. J Commun Disord. 2012;45(2):84-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.12.003. PMid:22225571.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011...

).

Open-class words (adjectives, adverbs, nouns, verbs, interjections) bear more robust references than closed-class words (articles, conjunctions, numerals, prepositions, pronouns) and, therefore, are the first to be acquired during language development. This occurs especially with nouns, which are relatively easy to be learned by children and open the way for the learning of words with less obvious relationships, or with more complex morphological structures. Verbs, in turn, are acquired later due to the initial difficulty children have to detect their conceptual and semantic components, or to understand how they are combined(33 Gentner D. Why verbs are hard to learn. In: Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff R, editores. Action meets word: how children learn verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 544-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195170009.003.0022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/978...

).

Verbs function as organizing elements of the syntactic structure and of the correct use of other word classes(44 Araujo K. Desempenho gramatical de criança em desenvolvimento normal e com distúrbio específico de linguagem. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2007.). There are several clues (morphological and syntactic) involving language that may help identify a word as a verb. Morphological clues help define the part of speech that is unknown to the child (for example, verb termination). Syntactic clues show that a sentence is structured around a verb by predetermined rules(55 Johnson VE, Villiers JG. Syntactic frames in fast mapping verbs: effect of age, dialect, and clinical status. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(3):610-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135). PMid:19474395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008...

).

In Brazilian Portuguese, children with typical development begin their language acquisition with nouns, but from the second year of life they present a slightly greater amount of verbs compared to nouns, which can be observed throughout preschool life. Verbs are predominantly acquired in the following order: intransitive, copula, transitive direct, transitive circumstantial, and transitive indirect(66 Befi-Lopes DM, Cáceres AM, Araújo K. Aquisição de verbos em pré-escolares falantes do português brasileiro. Revista CEFAC. 2007;9(4):444-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007000400003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007...

).

However, some children may present difficulty in language development which results in differences in the way they acquire and use word classes. That is the case of children with language impairment (LI), characterized by specific difficulties in language aspects, with absence of factors such as hearing loss, neurological and cognitive development disorders, emotional problems, and environment deprivation(77 Bishop DV. What causes specific language impairment in children? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(5):217-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00439.x. PMid:19009045.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.20...

,88 Bishop DV. Ten questions about terminology for children with unexplained language problems. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(4):381-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12101. PMid:25142090.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.1210...

).

LI comprises two major language frameworks: language delay and specific language impairment. The first refers to a generalized delay in receptive and expressive language, but follows the same sequence of typical language development. The latter refers to atypical development of language skills due to specific problems in two or more language aspects(99 Befi-Lopes D. Avaliação diagnóstica e aspectos terapêuticos nos distúrbios específicos de linguagem. In: Fernandes F, Mendes B, Navas A, editores. Tratado de Fonoaudiologia. 2. ed. São Paulo: Roca; 2011. p. 314-22.).

Due to the age range studied, we have chosen to use the general term language impairment (LI), considering that differentiation between the frameworks of delay and specific impairment by maintenance of language deficits after therapeutic intervention could only be used when all individuals were over five years old.

Children with LI present limited language processing ability, which interferes with the acquisition and processing of language in real time. Thus complex linguistic operations can overload their capacity, resulting in competition for resources between the different language processing stages, so that their early stages are benefited(1010 Pizzioli F, Schelstraete MA. The argument-structure complexity effect in children with specific language impairment: evidence from the use of grammatical morphemes in French. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51(3):706-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/050). PMid:18506045.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008...

).

Among the many linguistic difficulties that may be manifested in this group, impairment in the use of verbs is commonly identified as a characteristic aspect(1111 Windfuhr KL, Faragher B, Conti-Ramsden G. Lexical learning skills in young children with specific language impairment (SLI). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(4):415-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1368282021000007758. PMid:12396842.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820210000...

). The development of grammar morphology in this population tends to fall short compared with that observed in children with typical development. This difficulty is evidenced by late acquisition of grammatical morphemes and maintenance of primitive grammar structures(1212 Verhoeven L, Steenge J, van Balkom H. Verb morphology as clinical marker of specific language impairment: evidence from first and second language learners. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(3):1186-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.001. PMid:21333487.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01...

), which may occur because of possible deficits in word processing owing to phonological or working memory impairment(1313 Conti-Ramsden G, Windfuhr K. Productivity with word order and morphology: a comparative look at children with SLI and children with normal language abilities. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(1):17-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089380. PMid:11852456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089...

).

Children with LI are more dependent on the frequency of stimulation and lexical-semantic information(1414 Pizzioli F, Schelstraete MA. Lexico-semantic processing in children with specific language impairment: the overactivation hypothesis. J Commun Disord. 2011;44(1):75-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.07.004. PMid:20739027.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010...

) and less able to retain new verbs than younger children with typical language development(1515 Riches NG, Tomasello M, Conti-Ramsden G. Verb learning in children with SLI: frequency and spacing effects. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48(6):1397-411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005/097). PMid:16478379.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005...

). Therefore, they need a greater variety of verbs stored in their lexicon to abstract the morphological rules of their language and thus develop a more widespread knowledge of verbs(1111 Windfuhr KL, Faragher B, Conti-Ramsden G. Lexical learning skills in young children with specific language impairment (SLI). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(4):415-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1368282021000007758. PMid:12396842.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820210000...

), in addition to being less likely to vary the choices of their verbs, matching younger children paired by vocabulary(1616 Owen Van Horne AJ, Lin S. Cognitive state verbs and complement clauses in children with SLI and their typically developing peers. Clin Linguist Phon. 2011;25(10):881-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.582226. PMid:21728829.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011....

).

Nevertheless, language interferes with the nature of the difficulties that the speaker with LI will face when using verbs. In English, it is observed that this difficulty occurs with respect to its diversity and the correct use of morphology, which remains throughout schooling(1717 Ebbels SH, van der Lely HK, Dockrell JE. Intervention for verb argument structure in children with persistent SLI: a randomized control trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50(5):1330-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/093). PMid:17905915.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007...

), and it can be considered one of its clinical signs(33 Gentner D. Why verbs are hard to learn. In: Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff R, editores. Action meets word: how children learn verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 544-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195170009.003.0022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/978...

).

In Spanish, there are reports of difference in the pattern of eye movements for verbs with different number of arguments, with greater difficulty in recognizing those with three arguments(1818 Andreu L, Sanz-Torrent M, Guàrdia-Olmos J. Auditory word recognition of nouns and verbs in children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). J Commun Disord. 2012;45(1):20-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.09.003. PMid:22055614.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011...

). Frequent use of infinitive verb forms is reported for speakers of Catalan and Spanish(1919 Sanz-Torrent M, Serrat E, Andreu L, Serra M. Verb morphology in Catalan and Spanish in children with specific language impairment: a developmental study. Clin Linguist Phon. 2008;22(6):459-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892959. PMid:18484285.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892...

), as well as of English(2020 Arndt KB, Schuele CM. Production of infinitival complements by children with specific language impairment. Clin Linguist Phon. 2012;26(1):1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.584137. PMid:21728831.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011....

). Such a fact is justified because this verb mode shows no variation in grammatical agreement, which reduces its linguistic processing demand(1919 Sanz-Torrent M, Serrat E, Andreu L, Serra M. Verb morphology in Catalan and Spanish in children with specific language impairment: a developmental study. Clin Linguist Phon. 2008;22(6):459-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892959. PMid:18484285.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892...

).

In Brazilian Portuguese, there are findings that indicate some difficulty associated with the identification of how many and which complements are required by a verb so that its meaning is complete and understood(44 Araujo K. Desempenho gramatical de criança em desenvolvimento normal e com distúrbio específico de linguagem. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2007.).

Considering the lack of information regarding the acquisition and use of verbs, the present study aimed to compare the functional use of verbs and nouns by Brazilian Portuguese-speaking children with language impairment (LI) and to verify whether their use of these word classes is different from that of children with typical language development (TLD). This study also aimed to compare the use of each verb type between groups.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the aforementioned institution under number 1159/09. All individuals had their Informed Consent Forms signed by their parents or guardians.

Participants

The LI group was composed of 20 preschoolers who were undergoing speech therapy weekly at the Laboratory of Speech-language Pathology Investigation on Language Development at the Department of Physiotherapy, Speech-language Pathology and Occupational Therapy of the School of Medicine at the Universidade de Sao Paulo - USP. The individuals' age ranged between 3 years and 2 months and 6 years and 10 months (Table 1).

Exclusion criteria established in the literature(77 Bishop DV. What causes specific language impairment in children? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(5):217-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00439.x. PMid:19009045.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.20...

) were used in this study. Inclusion criteria comprised performance in expressive language below expectations in at least two standardized tests: vocabulary(2121 Befi-Lopes DM. Vocabulário. In: Andrade CRF, Befi-Lopes DM, Fernandes FDM, Wertzner HF, editores. ABFW: teste de linguagem infantil nas areas de fonologia, vocabulário, fluência e pragmática. 2. ed. Barueri: Pró-Fono; 2004. p. 33-50.), speech-language pathology(2222 Wertzner HF. Fonologia. In: Andrade CRF, Befi-Lopes DM, Fernandes FDM, Wertzner HF, editores. ABFW: teste de linguagem infantil nas áreas de fonologia, vocabulário, fluência e pragmática. 2. ed. Barueri: Pró-Fono; 2004. p. 5-32.), or mean length of utterance (MLU)(44 Araujo K. Desempenho gramatical de criança em desenvolvimento normal e com distúrbio específico de linguagem. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2007.), as well as receptive and/or expressive language age below chronological age based on the third edition of the Test of Early Language Development (TELD-3)(2323 Hresko W, Reid D, Hammill D. Test of Early Language Developmental (TELD). 3. ed. Austin: PRO-ED; 1999.) adapted to Brazilian Portuguese(2424 Giusti E, Befi-Lopes DM. Performance of Brazilian Portuguese and English speaking subjects on the test of early language development. Pro Fono. 2008;20(1):13-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872008000100003. PMid:18408858.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872008...

).

It should be noted that, due to age range, it was not possible to conduct the Non-verbal Intelligence Test (Non-verbal IQ), thus children with altered neuropsychomotor development history (delay greater than six months in relation to the expected in typical development to sit, walk, and control the head and sphincters) were not included. However, it is worth mentioning that, as these children were under speech therapy when they reached the age to be included in the study, all of them underwent evaluation to verify intellectual performance, and no impairment was found in any of the cases.

The TLD group consisted of 60 preschoolers aged 2 to 4 years (Table 1). Data collection occurred in a public elementary education institution in the city of Sao Paulo. Individuals were paired according to expressive language age, for example, a child with LI with expressive language age equivalent to four years was matched to the control group of 4-year-olds. In total, two individuals had expressive language age equivalent to 2 years, seven individuals presented expressive language age equivalent to 3 years, and 11 individuals had expressive language age equivalent to 4 years.

Material and methods

For data collection, a room was previously prepared with a camcorder on a tripod and some toys on a carpet. During collection, the child was encouraged to interact with the speech therapist for a period of 30 minutes. The evaluator asked open questions aiming to propitiate the child’s best communicative initiative situation.

Considering the age groups studied and the need to obtain spontaneous speech, speech samples were collected from both groups through ludic interaction using the following toys: animal farm, transportation, food, kitchen utensils, and two dolls. The interactions were video recorded using a digital camcorder.

It is worth mentioning that, in the case of children with LI, the interactions occurred with the speech therapist who was attending the child in order to guarantee a familiar situation. In the control group, the same researcher interacted with all the children in the educational environment; however, this researcher had interacted with all individuals before data collection, and was, therefore, familiarized with them(66 Befi-Lopes DM, Cáceres AM, Araújo K. Aquisição de verbos em pré-escolares falantes do português brasileiro. Revista CEFAC. 2007;9(4):444-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007000400003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007...

). All speech therapists received the same training and were supervised by one of the study authors during the collection of speech samples.

From the data collected, 100 segments were transcribed from the most intense communicative interaction period established with the individuals within the 30 minutes recorded, as proposed by Brown(2525 Brown R. A first language: the Early Stages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1973. http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674732469.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.978067...

). After transcription, all nouns and verbs present in the selected speech sample were tabulated. All verbs were classified according to Lima(2626 Lima R. Gramática normativa da Língua Portuguesa. 22. ed: José Olympio; 1982.) in intransitive, transitive direct, transitive indirect, transitive relative, transitive circumstantial, and bitransitive.

Importantly, the classification of verbs occurred in accordance with the use determined by each speaker. Therefore, a transitive direct verb used without a complement was classified as intransitive. Similarly, a transitive indirect verb used with a complement without a preposition was classified as transitive direct.

Data analysis

Duly tabulated data were submitted to statistical treatment using the software SPSS 18 (distribution type; descriptive and inferential analysis). Normality of data distribution was observed only for the LI group; therefore, the Paired t-test was used for intragroup comparisons between the number of nouns and verbs and the Mann-Whitney test was applied for analysis between the groups. A statistical significance level of 5% was adopted and significant results were marked with an asterisk.

RESULTS

Use of nouns and verbs

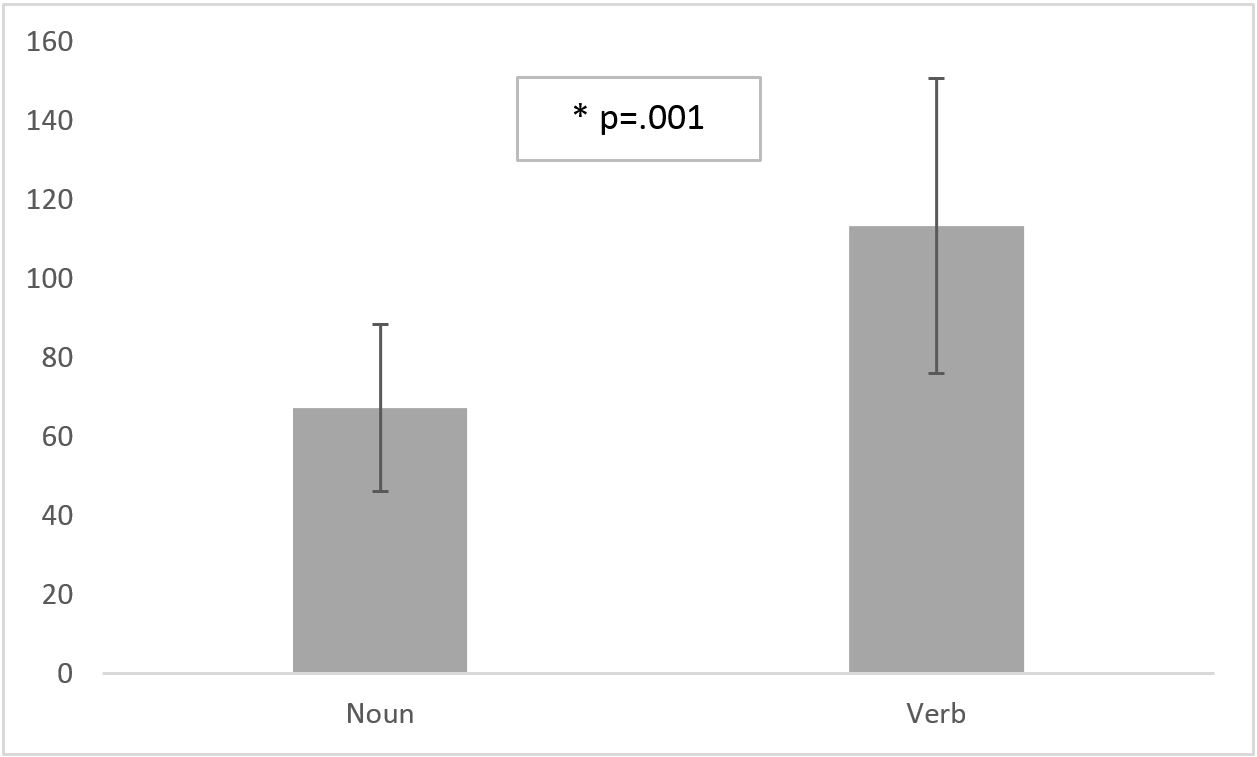

Preschoolers with LI use verbs more frequently than nouns in their production of spontaneous speech. Comparison between the performance of individuals with LI and TLD showed that the use of nouns cannot be distinguished between these groups regardless of expressive language age. Regarding the use of verbs, no distinction was observed in the 2 and 4-year-old subgroups, but 3-year-old individuals with LI produced more verbs than their peers (Table 2).

Types of verbs used

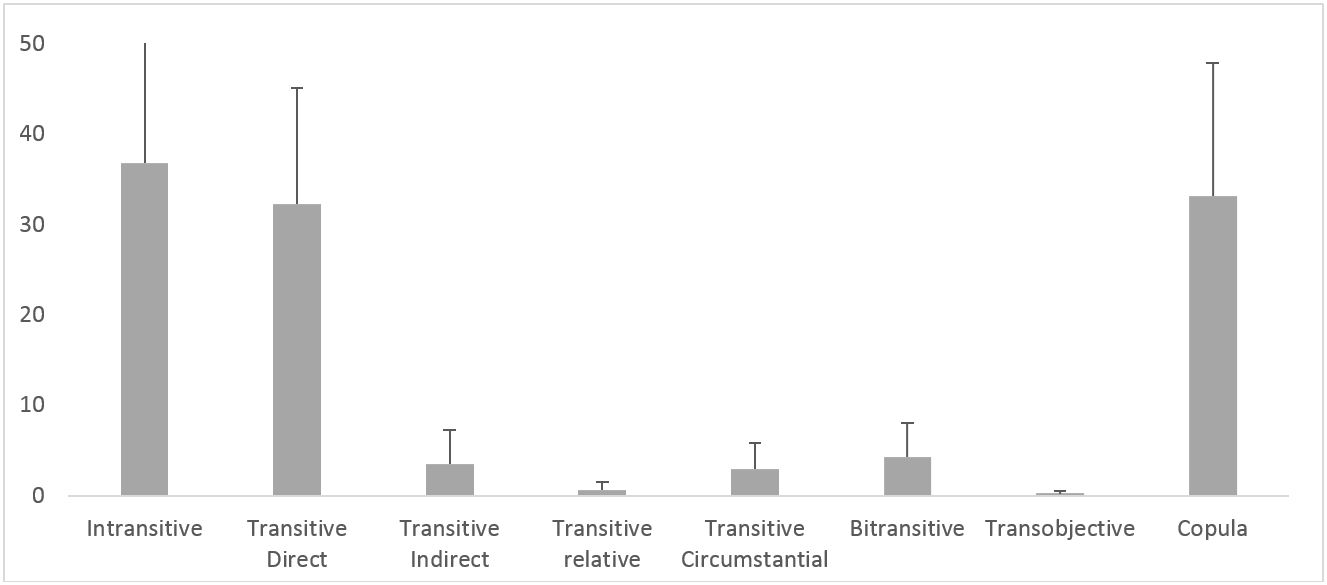

The verbs most commonly used by children with LI were copula, intransitive, and transitive direct.

Comparison between individuals with LI and TLD with respect to the use of verbs did not show difference between intransitive, transitive indirect, transitive relative, and transobjective verbs produced at all ages. Nevertheless, individuals with LI used transitive direct verbs more often than their peers in the 2 and 3-year-old subgroups; bitransitive verbs in the 3 and 4-year-old subgroups; and copular verbs in 4-year-old subgroup. Finally, individuals with TLD used transitive circumstantial verbs more frequently than their peers in all age groups (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the use of nouns and verbs by preschool children with language impairment (LI) and to compare their performance with that of their peers with typical language development (TLD).

Regarding the quantitative comparison between nouns and verbs used by individuals with LI, the results show that these preschoolers used verbs more often than nouns in their production (Graph 1). This finding differs from the results obtained in international studies which report that English-speaking individuals with LI showed better performance in the use of nouns compared with verbs(55 Johnson VE, Villiers JG. Syntactic frames in fast mapping verbs: effect of age, dialect, and clinical status. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(3):610-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135). PMid:19474395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008...

,1313 Conti-Ramsden G, Windfuhr K. Productivity with word order and morphology: a comparative look at children with SLI and children with normal language abilities. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(1):17-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089380. PMid:11852456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089...

,1818 Andreu L, Sanz-Torrent M, Guàrdia-Olmos J. Auditory word recognition of nouns and verbs in children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). J Commun Disord. 2012;45(1):20-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.09.003. PMid:22055614.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011...

,2727 Kambanaros M. Does verb type affect action naming in specific language impairment (SLI)? Evidence from instrumentality and name relation. J Neurolinguist. 2012;26(1):160-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2012.07.003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2...

).

English-speaking children with LI show slower verb learning(1313 Conti-Ramsden G, Windfuhr K. Productivity with word order and morphology: a comparative look at children with SLI and children with normal language abilities. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(1):17-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089380. PMid:11852456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089...

), as well as difficulties in rapid mapping(55 Johnson VE, Villiers JG. Syntactic frames in fast mapping verbs: effect of age, dialect, and clinical status. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(3):610-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135). PMid:19474395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008...

) and linguistic processing(1818 Andreu L, Sanz-Torrent M, Guàrdia-Olmos J. Auditory word recognition of nouns and verbs in children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). J Commun Disord. 2012;45(1):20-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.09.003. PMid:22055614.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011...

). However, these differences may result from the language spoken, as our findings reproduce what has been observed in Brazilian preschoolers with typical development(66 Befi-Lopes DM, Cáceres AM, Araújo K. Aquisição de verbos em pré-escolares falantes do português brasileiro. Revista CEFAC. 2007;9(4):444-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007000400003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007...

).

Interestingly, no differences were found between individuals with LI and their peers with respect to expressive language age for the use of nouns (Table 2). This shows that children in the LI group use nouns similarly to their peers, but in a slower way, which is a characteristic of this language impairment(44 Araujo K. Desempenho gramatical de criança em desenvolvimento normal e com distúrbio específico de linguagem. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2007.). Therefore, it is important to emphasize that the individuals in the LI group had higher chronological age than their peers, which evidences this delay.

When this comparison considered the verbs, there was no difference in the 2 and 4-year-old subgroups, but individuals with LI in the 3-year-old subgroup produced more verbs than their peers (Table 2). LI individuals show a gap between their chronological and language ages; therefore, although they were paired by expressive language age, they have been exposed to language longer, and thus may have used more verbs than their language peers. Moreover, considering their more advanced chronological age, it is possible that they have been less uniform in their language development, so that specific differences such as these would be understandable.

These findings may differ from the results obtained for English language, because English verbs are ‘tight’ and suffer few variations in person, tense, and mode. In contrast, verbs in Brazilian Portuguese and Roman languages in general, present many variations in person, number, tense, and mode(1919 Sanz-Torrent M, Serrat E, Andreu L, Serra M. Verb morphology in Catalan and Spanish in children with specific language impairment: a developmental study. Clin Linguist Phon. 2008;22(6):459-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892959. PMid:18484285.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892...

). Such variations allow the same verb to be exposed in different forms to speakers; therefore, the higher the frequency of a verb in a stimulus, the more often and flexibly it may occur in children's speech, facilitating its learning(66 Befi-Lopes DM, Cáceres AM, Araújo K. Aquisição de verbos em pré-escolares falantes do português brasileiro. Revista CEFAC. 2007;9(4):444-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007000400003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007...

).

Regarding the classification of type of verbs produced by the preschoolers with LI, the most commonly used verbs were intransitive, copula, and transitive direct (Graph 2). Our results corroborate international findings in English on the difficulties regarding the use of verb arguments by individuals with LI(1010 Pizzioli F, Schelstraete MA. The argument-structure complexity effect in children with specific language impairment: evidence from the use of grammatical morphemes in French. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51(3):706-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/050). PMid:18506045.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008...

,1919 Sanz-Torrent M, Serrat E, Andreu L, Serra M. Verb morphology in Catalan and Spanish in children with specific language impairment: a developmental study. Clin Linguist Phon. 2008;22(6):459-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892959. PMid:18484285.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892...

,2020 Arndt KB, Schuele CM. Production of infinitival complements by children with specific language impairment. Clin Linguist Phon. 2012;26(1):1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.584137. PMid:21728831.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011....

,2828 Skipp A, Windfuhr KL, Conti-Ramsden G. Children’s grammatical categories of verb and noun: a comparative look at children with specific language impairment (SLI) and normal language (NL). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(3):253-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110119214. PMid:12201977.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110119...

). Children with LI use verbs omitting their arguments because their learning process is difficult and is related to verb complexity(2828 Skipp A, Windfuhr KL, Conti-Ramsden G. Children’s grammatical categories of verb and noun: a comparative look at children with specific language impairment (SLI) and normal language (NL). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(3):253-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110119214. PMid:12201977.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110119...

,2929 Grela BG. The omission of subject arguments in children with specific language impairment. Clin Linguist Phon. 2003;17(2):153-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0269920031000061812. PMid:12762209.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200310000...

).

Comparison between individuals with LI and their peers according to expressive language age allowed the observation of specific differences: higher frequency of use of transitive direct verbs at 2 and 3 years old, bitransitive verbs at 3 and 4 years old, and copular verbs at 4 years old by individuals with LI (Table 3). Once again, the gap between chronological and language ages may have contributed to these differences, especially regarding copular verbs; individuals at the language age of 4 years may have already realized that this type of verb is of simple use and, therefore, use them more frequently.

However, as for transitive circumstantial verbs, the opposite standard was observed at all ages, that is, the group with TLD used this type of verb more often than children with LI (Table 3). As this type of verb demands a complement that may or may not be prepositional, its use requires that the speakers have more comprehensive language skills in grammar structure, which could explain its less frequent use by individuals with LI(2626 Lima R. Gramática normativa da Língua Portuguesa. 22. ed: José Olympio; 1982.).

In summary, frequent omission of verb complements is observed, which justifies the large number of intransitive verbs used per speaker. This demonstrates the difficulty in grammar structuring experienced by individuals with LI. As verbs belong to a word class of significant syntactic and semantic value, the individuals may have reduced their sentences to their use, because they already express meaning within them but require smaller linguistic refinement. Thus they may have opted for verbs of easier use, considering that intransitive verbs do not require arguments; and that transitive direct verbs, despite the need for arguments, do not require prepositions - a class of words that is difficult for individuals with LI due to its low robustness(3030 Puglisi ML, Befi-Lopes DM, Takiuchi N. Utilização e compreensão de preposições por crianças com distúrbio específico de linguagem. Pró-Fono. 2005;17(3):331-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872005000300007. PMid:16389790.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872005...

); and that copular verbs, in turn, have only the function to link the predicate to the subject.

It’s worth mentioning that some factors may have limited the results of our study. The task composed by spontaneous speech allowed the verification of the functional use of language and grammar classes of nouns and verbs by individuals with LI, demonstrating their real language and communicative skills. However, it also contributed to questioning involving the context, as a possible influence to the omission of verb arguments. Therefore, although spontaneous speech is an important sample on the effective use of language and valuable from the standpoint of evaluation and rehabilitation, it may be useful to conduct a study with a design more focused on verb complementation in order to clarify our objectives.

In addition, the current study included a small number of individuals with LI, which became even smaller samples when divided by expressive language ages. Aware of this factor, we highlight that, even though our statistical results are reliable, a larger sample could show more robust data for the study of language development and acquisition and use of verbs by children with LI.

However, we emphasize the validity of our findings to speech-language pathology clinical practice, because this analysis clearly and objectively provides important clues about the functional use of language and allows accurate measurements on these different word classes in the sequence of spontaneous speech. Similarly, it enables the tracing of therapeutic strategies directed to morphosyntax based on the expressive language age of each subject, following the standard expected for typical development at this stage.

Finally, in order to investigate the production and grammatical use of verbs, we suggest that further studies be conducted with analyses on the variability of verb production of individuals with LI. This way, we believe that it will be possible to infer more consistently about the effect of time exposure to language on the use of verbs, as well as whether the amount of verbs produced by a subject could be indicative of greater or lesser language maturity.

CONCLUSION

Brazilian Portuguese-speaking preschoolers with language impairment use verbs more frequently than nouns in spontaneous speech activity. The use of nouns did not differ between individuals in the LI group and their peers with typical language development, but the use of verbs at 3 years of age was higher in the LI group.

Regarding the types of verbs, individuals with LI use copular, intransitive, and transitive direct verbs more often. Comparison between the groups revealed few differences in the use of transitive direct, bitransitive, and copular verbs; only transitive circumstantial verbs were used more often by children with TLD at all ages.

-

Study carried out at the Laboratório de Investigação Fonoaudiológica em Desenvolvimento da Linguagem e suas Alterações of the Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo – USP - São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

-

Financial support: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) - process No. 2013/07032-5.

REFERÊNCIAS

-

1Gândara JP. Aquisição lexical no desenvolvimento normal e alterado de linguagem: um estudo experimental. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2008.

-

2Alt M, Suddarth R. Learning novel words: detail and vulnerability of initial representations for children with specific language impairment and typically developing peers. J Commun Disord. 2012;45(2):84-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.12.003 PMid:22225571.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.12.003 -

3Gentner D. Why verbs are hard to learn. In: Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff R, editores. Action meets word: how children learn verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 544-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195170009.003.0022

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195170009.003.0022 -

4Araujo K. Desempenho gramatical de criança em desenvolvimento normal e com distúrbio específico de linguagem. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2007.

-

5Johnson VE, Villiers JG. Syntactic frames in fast mapping verbs: effect of age, dialect, and clinical status. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(3):610-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135) PMid:19474395.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135) -

6Befi-Lopes DM, Cáceres AM, Araújo K. Aquisição de verbos em pré-escolares falantes do português brasileiro. Revista CEFAC. 2007;9(4):444-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007000400003

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462007000400003 -

7Bishop DV. What causes specific language impairment in children? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(5):217-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00439.x PMid:19009045.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00439.x -

8Bishop DV. Ten questions about terminology for children with unexplained language problems. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(4):381-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12101 PMid:25142090.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12101 -

9Befi-Lopes D. Avaliação diagnóstica e aspectos terapêuticos nos distúrbios específicos de linguagem. In: Fernandes F, Mendes B, Navas A, editores. Tratado de Fonoaudiologia. 2. ed. São Paulo: Roca; 2011. p. 314-22.

-

10Pizzioli F, Schelstraete MA. The argument-structure complexity effect in children with specific language impairment: evidence from the use of grammatical morphemes in French. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51(3):706-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/050) PMid:18506045.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/050) -

11Windfuhr KL, Faragher B, Conti-Ramsden G. Lexical learning skills in young children with specific language impairment (SLI). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(4):415-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1368282021000007758 PMid:12396842.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1368282021000007758 -

12Verhoeven L, Steenge J, van Balkom H. Verb morphology as clinical marker of specific language impairment: evidence from first and second language learners. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(3):1186-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.001 PMid:21333487.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.001 -

13Conti-Ramsden G, Windfuhr K. Productivity with word order and morphology: a comparative look at children with SLI and children with normal language abilities. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(1):17-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089380 PMid:11852456.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110089380 -

14Pizzioli F, Schelstraete MA. Lexico-semantic processing in children with specific language impairment: the overactivation hypothesis. J Commun Disord. 2011;44(1):75-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.07.004 PMid:20739027.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.07.004 -

15Riches NG, Tomasello M, Conti-Ramsden G. Verb learning in children with SLI: frequency and spacing effects. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48(6):1397-411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005/097) PMid:16478379.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005/097) -

16Owen Van Horne AJ, Lin S. Cognitive state verbs and complement clauses in children with SLI and their typically developing peers. Clin Linguist Phon. 2011;25(10):881-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.582226 PMid:21728829.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.582226 -

17Ebbels SH, van der Lely HK, Dockrell JE. Intervention for verb argument structure in children with persistent SLI: a randomized control trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50(5):1330-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/093) PMid:17905915.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/093) -

18Andreu L, Sanz-Torrent M, Guàrdia-Olmos J. Auditory word recognition of nouns and verbs in children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). J Commun Disord. 2012;45(1):20-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.09.003 PMid:22055614.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.09.003 -

19Sanz-Torrent M, Serrat E, Andreu L, Serra M. Verb morphology in Catalan and Spanish in children with specific language impairment: a developmental study. Clin Linguist Phon. 2008;22(6):459-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892959 PMid:18484285.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699200801892959 -

20Arndt KB, Schuele CM. Production of infinitival complements by children with specific language impairment. Clin Linguist Phon. 2012;26(1):1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.584137 PMid:21728831.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2011.584137 -

21Befi-Lopes DM. Vocabulário. In: Andrade CRF, Befi-Lopes DM, Fernandes FDM, Wertzner HF, editores. ABFW: teste de linguagem infantil nas areas de fonologia, vocabulário, fluência e pragmática. 2. ed. Barueri: Pró-Fono; 2004. p. 33-50.

-

22Wertzner HF. Fonologia. In: Andrade CRF, Befi-Lopes DM, Fernandes FDM, Wertzner HF, editores. ABFW: teste de linguagem infantil nas áreas de fonologia, vocabulário, fluência e pragmática. 2. ed. Barueri: Pró-Fono; 2004. p. 5-32.

-

23Hresko W, Reid D, Hammill D. Test of Early Language Developmental (TELD). 3. ed. Austin: PRO-ED; 1999.

-

24Giusti E, Befi-Lopes DM. Performance of Brazilian Portuguese and English speaking subjects on the test of early language development. Pro Fono. 2008;20(1):13-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872008000100003 PMid:18408858.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872008000100003 -

25Brown R. A first language: the Early Stages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1973. http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674732469

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674732469 -

26Lima R. Gramática normativa da Língua Portuguesa. 22. ed: José Olympio; 1982.

-

27Kambanaros M. Does verb type affect action naming in specific language impairment (SLI)? Evidence from instrumentality and name relation. J Neurolinguist. 2012;26(1):160-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2012.07.003

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2012.07.003 -

28Skipp A, Windfuhr KL, Conti-Ramsden G. Children’s grammatical categories of verb and noun: a comparative look at children with specific language impairment (SLI) and normal language (NL). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2002;37(3):253-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110119214 PMid:12201977.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820110119214 -

29Grela BG. The omission of subject arguments in children with specific language impairment. Clin Linguist Phon. 2003;17(2):153-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0269920031000061812 PMid:12762209.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0269920031000061812 -

30Puglisi ML, Befi-Lopes DM, Takiuchi N. Utilização e compreensão de preposições por crianças com distúrbio específico de linguagem. Pró-Fono. 2005;17(3):331-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872005000300007 PMid:16389790.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872005000300007

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Aug 2016

History

-

Received

24 Mar 2015 -

Accepted

29 Oct 2015

Caption: * statistical difference p<0.05 – Paired t-test

Caption: * statistical difference p<0.05 – Paired t-test