Abstracts

Childhood overweight and obesity are growing public health concerns, leading to metabolic consequences such as increased body mass index, larger waist circumference, and excess body fat. Multi-component school interventions that address both the obesogenic environment and individual behaviors have been recommended, but their effectiveness remains uncertain. This review and meta-analysis, conducted following PRISMA guidelines, examined the impact of multi-component interventions - including modifications to the school food environment - on adiposity and food consumption among children and adolescents. A search on MEDLINE, SciELO, CENTRAL, Clinical Trials, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science identified 51 eligible studies. The meta-analysis showed a small but significant reduction in waist circumference (MD: -0.70cm; 95%CI: -1.22, -0.19; I2 = 40%). Interventions were also linked to lower intake of unhealthy foods, total energy, total fat, saturated fat, and increased vegetable consumption. However, no consistent effects were observed for body mass index or body fat percentage. Study quality varied, and intervention designs and implementation strategies were heterogeneous; thus, results should be interpreted cautiously. These findings suggest that while school food environment interventions can improve some dietary behaviors and adiposity indicators, their effectiveness in preventing obesity remains inconclusive. Strengthening policies and ensuring long-term, structured interventions are crucial for meaningful and sustained health improvements in school settings.

Keywords:

School Feeding; School Health Services; Nutrition Policy; Nutrition Programs; Noncommunicable Diseases

Sobrepeso e obesidade infantis representam desafios crescentes para a Saúde Pública, levando a consequências metabólicas, como aumento do índice de massa corporal, maior circunferência da cintura e excesso de gordura corporal. Recomendam-se intervenções escolares multicomponentes que integram fatores relacionados ao ambiente obesogênico e aos comportamentos individuais, mas sua eficácia permanece incerta. Esta revisão e metanálise, conduzida seguindo as diretrizes PRISMA, focou no impacto de intervenções multicomponentes - que incluíram mudanças no ambiente alimentar escolar - na adiposidade e no consumo alimentar de crianças e adolescentes. A busca nas bases de dados MEDLINE, SciELO, CENTRAL, Clinical Trials, Scopus, Embase e Web of Science identificou 51 estudos elegíveis. A metanálise mostrou uma redução pequena, mas significativa, na circunferência da cintura (DM: -0,70cm; IC95%: -1,22, -0,19; I2 = 40%). As intervenções também se associaram à menor ingestão de alimentos não saudáveis, energia total, gordura total e gordura saturada, bem como um aumento do consumo de hortaliças. No entanto, não foram observados efeitos consistentes no índice de massa corporal ou no percentual de gordura corporal. A qualidade dos estudos variou, com heterogeneidade no desenho e na implementação das intervenções. Portanto, os resultados devem ser interpretados com cautela. Os achados deste estudo sugerem que, embora intervenções no ambiente alimentar escolar possam levar à melhora de alguns comportamentos alimentares e medidas de adiposidade, seu impacto na prevenção da obesidade permanece inconclusivo. O fortalecimento de políticas e a garantia de intervenções estruturadas de longo prazo são cruciais para alcançar melhoras significativas e sustentadas na saúde em ambientes escolares.

Palavras-chave:

Alimentação Escolar; Serviços de Saúde Escolar; Política Nutricional; Programas de Nutrição; Doenças não Transmissíveis

El sobrepeso y la obesidad infantil representan un creciente desafío para la Salud Pública, con consecuencias metabólicas como el aumento del índice de masa corporal, una mayor circunferencia de cintura y un exceso de grasa corporal. Se han recomendado intervenciones escolares multicomponentes que integren factores relacionados con el entorno obesogénico y los comportamientos individuales, pero su efectividad sigue siendo incierta. Esta revisión y metaanálisis, realizado siguiendo las directrices PRISMA, se centró en el impacto de intervenciones multicomponentes que incluyeron cambios en el entorno alimentario escolar, sobre la adiposidad y el consumo de alimentos en niños y adolescentes. Una búsqueda en MEDLINE, SciELO, CENTRAL, Clinical Trials, Scopus, Embase y Web of Science identificó 51 estudios elegibles. El metaanálisis mostró una reducción pequeña pero significativa en la circunferencia de cintura (DM: -0,70cm; IC95%: -1,22, -0,19; I2 = 40%). Las intervenciones también se asociaron con un menor consumo de alimentos no saludables, energía total, grasa total, grasa saturada y un aumento en el consumo de verduras. Sin embargo, no se observaron efectos consistentes en el índice de masa corporal ni en el porcentaje de grasa corporal. La calidad de los estudios varió, con heterogeneidad en el diseño y la implementación de las intervenciones, por lo que estos resultados deben interpretarse con cautela. Los hallazgos sugieren que, aunque las intervenciones en el entorno alimentario escolar pueden mejorar algunos comportamientos dietéticos y medidas de adiposidad, su impacto en la prevención de la obesidad sigue siendo inconcluso. Fortalecer las políticas y garantizar intervenciones estructuradas a largo plazo son aspectos cruciales para lograr mejoras de salud significativas y sostenibles en el ámbito escolar.

Palabras-clave:

Alimentación Escolar; Servicios de Salud Escolar; Política Nutricional; Programas de Nutrición; Enfermedades no Transmisibles

Introduction

Childhood overweight and obesity are growing public health issues linked to metabolic issues such as increased body mass index (BMI), larger waist circumference (WC), and excess body fat 1,2. These factors predict lifelong cardiometabolic risks and are strongly associated with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) 3. Globally, adolescents are experiencing increasing disability and mortality rates due to NCDs 4.

In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) and international governments recommend school interventions to modify dietary patterns and reduce exposure to weight-promoting factors 5,6,7. Notably, school food and nutrition strategies have shifted from knowledge-based to behavior-oriented approaches, emphasizing the food environment rather than solely the individual 8. Studies worldwide have shown that obesogenic school environments are widespread, underscoring the need for interventions to change these settings 9,10,11,12,13,14 as they encourage unhealthy food choices that contribute to obesity 15.

Thus, multi-component interventions that promote physical activity, reduce sedentary behavior, and improve food environments and eating habits are more effective in integrating environmental factors with individual actions 16,17,18,19,20,21. This approach shows promise in improving adiposity indicators 18,21, enhancing dietary habits 17,20, and preventing unhealthy weight gain or obesity 17,19. Successful strategies also require involving family members 19, the school community, and nutrition and health experts 21.

Previous systematic reviews have evaluated the impact of school food environment interventions on adiposity 22,23,24, metabolic parameters 23, or food consumption 23,24,25 in children and adolescents. However, evidence on their effectiveness remains inconclusive, as most reviews focus on anthropometric outcomes 22,23,24 or food consumption 24,25. Therefore, this review aims to evaluate the impact of multi-component interventions - including changes in the school food environment - on adiposity and food consumption in children and adolescents, hypothesizing that such interventions can influence both outcomes.

Materials and methods

This systematic review of interventional studies investigates food consumption and adiposity in children and adolescents after interventions in their school food environment. The review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 26 (Supplementary Material - Table S1; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf) and conducted based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions27. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD 42020186070).

Search strategy

The MEDLINE (via PubMed), SciELO, CENTRAL, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Clinical Trials databases were searched. Reference lists of selected articles and previous systematic reviews were also screened, and relevant cited references were included. No restrictions were applied regarding language or year of publication. The search words used were: “schools”, “child”, “adolescent”, “school canteen”, “food environment”, “environment intervention”, “nutrition intervention”, and “nutrition policy”. The search strategy was developed and performed in each database in November 2023 (Supplementary Material - Table S2; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf).

Eligibility criteria and outcomes of interest

Articles were evaluated using the Population, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Type (PICOS) framework (Supplementary Material - Table S3; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf). Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) Students - children (> 2 years old) and adolescents (< 19 years old); (2) School food environment (internal environment and surroundings) - economic factors, nutritional aspects, school ambiance, legislation, and regulations for food sales in school facilities; (3) Adiposity - BMI, body fat percentage (%BF), WC as well as changes in food consumption (dietary intake); (4) Cluster randomized controlled trials (cRCTs), quasi-experimental (QE) studies, and field trials (FTs).

Exclusion criteria included observational studies, studies with mixed populations (including adults or older adults), studies based solely on educational interventions rather than the food environment, studies reporting only food consumption outcomes, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, letters, editorials, and articles repeating information from previously included populations.

Study selection, data collection process, and data items

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, three reviewers (L.A.V., B.C.C. and T.P.R.S.) screened duplicate titles and abstracts using the reference management software Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/). Full-text articles were assessed separately by two investigators (L.A.V. and B.C.C.) for eligibility; disagreements were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by consulting a third reviewer (L.L.R.). For abstracts from scientific meetings and symposia that met the criteria, authors were contacted for detailed information about recent publications or presented data. Data were extracted independently by two reviewers, duplicated, and organized in an Excel spreadsheet (https://products.office.com/), which included general study characteristics (title, authors, publication year, location), methods (design, measures of effect), participant characteristics (school grade, intervention components), outcomes, and main results. A pilot test of the data collection form was conducted, and all reviewers were trained before and during the survey.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were conducted using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model. This approach was chosen because it yields more conservative estimates and accounts for potential unobserved heterogeneity across studies, providing a more robust synthesis of the evidence.

Meta-analyses were presented and interpreted separately based on the study design, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (section 23.2.6) 27. Treatment effects for continuous outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). When available, the difference between final and baseline values was used for analysis. Forest plots were generated to present the meta-analysis results.

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test, with p-values < 0.10 considered statistically significant. The I2 test was used to evaluate the magnitude of heterogeneity, classified as moderate when I2 > 25% and high when I2 > 75%. Analyses were performed in R Statistical Software, version 4.4.0 (http://www.r-project.org), using the Meta (version 6.2.1) 28 and Metafor (version 4.3.0) 29 packages. No dichotomous outcomes were reported in primary studies; only continuous outcomes were analyzed. Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies with high or serious risk of bias, and results are presented in the supplementary material. Publication bias was assessed via visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s test when a meta-analysis included ten or more studies. If publication bias was detected, it was corrected using the Trim-and-Fill method, and the impact of the correction on result interpretation was evaluated 27.

Risk of bias within and across studies

The methodological quality of the primary studies was evaluated using the revised risk of bias (ROB 2.0) for randomized controlled trials. For QE studies, risk of bias was assessed using the non-randomized intervention studies tool (ROBINS-I), following Cochrane Collaboration recommendations 27. Each study assessed with ROB 2.0 was evaluated across five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process; (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (3) bias due to missing outcome data; (4) bias in the outcome measurement; and (5) bias in the selection of the reported result. Risk of bias judgments were classified as (a) low risk, (b) some concerns, or (c) a high risk. If any specific domain was rated as higher risk, the overall risk of bias assigned to the study was assigned at least at the same level of severity.

The ROBINS-I tool is based on seven domains, namely: (1) bias due to confounding; (2) bias due to participant selection; (3) bias in classification of interventions; (4) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (5) bias due to missing data; (6) bias in outcome measurement; and (7) bias in selection of the reported result. Risk of bias was classified as (a) low risk, (b) moderate risk, (c) serious risk, (d) critical risk, or (e) no information. We considered age and sex as the minimum set of confounding variables. Studies that did not adjust for these variables were rated as at least moderate risk of bias due to confounding.

The overall certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system 30.

Results

The search strategy identified 4,141 records (1,306 in PubMed, 1,267 in Scopus, 799 in Web of Science, 318 in Embase, 154 in CENTRAL, 45 in SciELO, and 198 in other sources). After removing duplicates (n = 1,947) and screening titles and abstracts (n = 2,194), 95 full-text records were assessed for eligibility. A total of 51 publications were included in this review, and 24 were included in the quantitative synthesis. A flowchart showing the study selection process is presented in Figure 1, and reasons for excluding studies in the second screening phase are detailed in Supplementary Material (Table S4; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf).

Study characteristics

Study characteristics and outcomes are presented in Table 1 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81. The earliest publication dates from 1996, and 76.5% (n = 39) of the selected articles were published between 2009 and 2023. The most frequent study designs were cRCT (n = 39; 76.5%) 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,50,57,58,59,60,61,63,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,76,77,78,79,80,81, followed by QE (n = 12; 23.5%) 43,48,50,51,52,53,54,56,62,64,74,75. Trials were conducted in North America (n = 21; 41.2%) 55,56,57,58,59,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81, Asia (n = 15; 29.4%) 36,37,38,39,40,46,47,48,49,51,52,53,54,64,65, Europe (n = 8; 15.7%) 34,42,44,45,50,60,61,63, Oceania (n = 3; 5.9%) 32,33,43, and Latin America (n = 4; 7.8%) 31,35,41,62. Most populations consisted of primary school students (n = 35; 68.6%) 31,32,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,44,45,48,49,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,62,63,64,66,67,68,70,71,73,74,75,79,80,81, secondary school students (n = 12; 23.5%) 33,34,41,43,46,47,50,54,60,61,69,76, or both (n = 4; 7.8%) 65,72,77,78. The median intervention duration was 10 months (range 1-48). Most studies (n = 41; 80.4%) 31,32,33,34,35,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,53,54,55,57,58,59,62,63,64,65,66,67,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,80,81 assessed outcomes immediately after the intervention, with no follow-up. Among studies that conducted follow-up, the median duration was six months (range 1-36).

A total of 44 interventions were found across 51 studies, each including two or more components with at least one environmental component. A description of the multi-component interventions (environmental and individual) is shown in Supplementary Material (Figure S1; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf). Most interventions had environmental components targeting changes to the school canteen (n = 40; 90.9%) 31,32,33,34,35,38,39,40,41,42,43,46,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,80 and school policies (n = 33; 75%) 32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,48,50,51,54,56,57,58,60,63,64,66,69,70,72,73,74,77,78,79,80,81. Details of school interventions and the main study results are provided in Table 1. Among individual-level components, the most common were nutrition and health education sessions (n = 38; 86.4%) 31,33,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,64,65,66,70,71,73,74,76,77,78,79,80,81, parent involvement (n = 36; 81.8%) 31,33,35,36,38,39,40,41,43,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,57,58,59,62,63,64,66,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,80,81, and teacher programs (n = 30; 68.2%) 34,35,36,38,39,42,43,44,46,48,51,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,63,66,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78 (Table 1). Intervention coverage was analyzed across studies, but given their heterogeneity, it was impossible to establish any association between intervention effectiveness and duration.

The selected articles presented outcomes in two main categories: adiposity (BMI, %BF, WC) and food consumption. Figure S2 (Supplementary Material; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf) summarizes the conclusions from the studies included in this review.

Adiposity

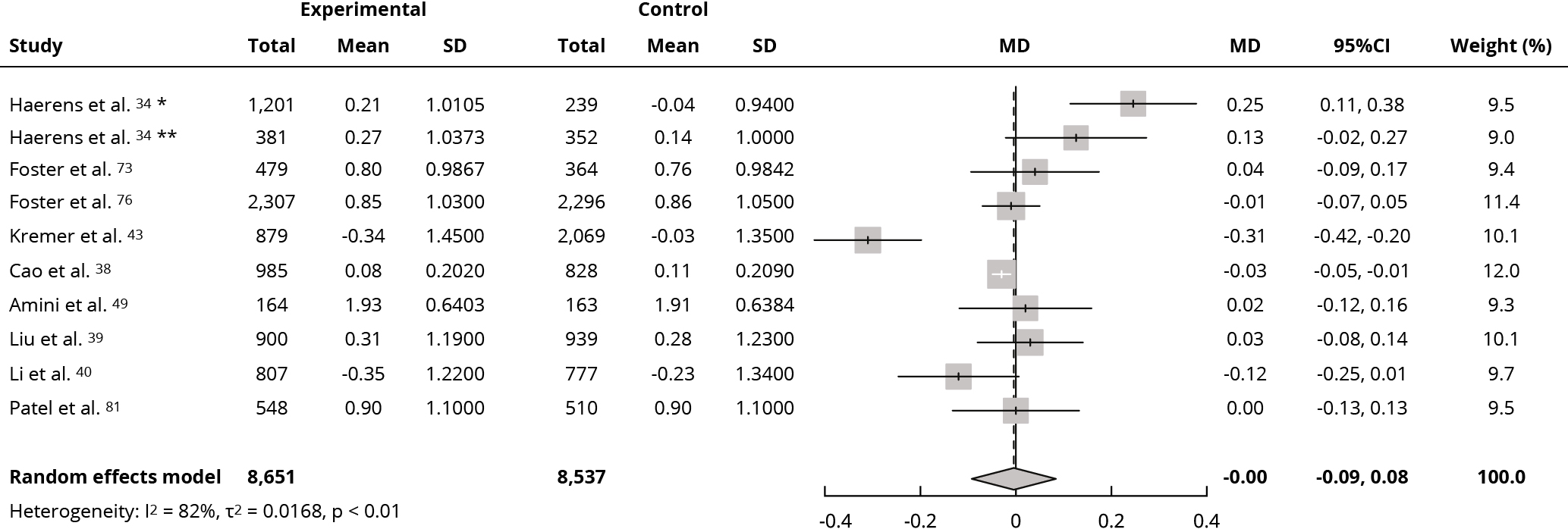

Meta-analyses were performed using BMI data from 19 assessed studies. Interventions did not affect mean BMI (kg/m2) compared with the control group (MD: -0.01; 95%CI: -0.26, 0.23; I2 = 78%; low certainty of evidence) (Figure 2), nor mean BMI z-score (MD: -0.00; 95%CI: -0.09, 0.08; I2 = 82%; very low certainty of evidence) (Figure 3). Sensitivity analysis for both outcomes showed a change in effect direction after removing studies with high risk of bias, but results remained insignificant (Supplementary Material - Figures S3 and S4; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf). Twenty-two studies were included in the qualitative synthesis due to incomplete data for the meta-analysis. Among these, seven 35,50,52,53,69,74,75 reported significant BMI reductions; in two 35,69, the reduction was observed only in boys, and in one 75 only in girls. Three studies 56,58,77 reported increased BMI in both groups, while the remaining studies recorded no significant changes 31,33,42,46,51,57,59,62,72,78,79,80. One study 64 provided only BMI classifications and was included solely for food consumption data. Thus, interventions had no significant effect on mean BMI (kg/m2) or BMI z-score in the meta-analysis. Although some studies included only in the qualitative synthesis showed reductions, findings were heterogeneous and inconsistent.

Forest plot of the effect of intervention in food environment school on body mass index (kg/m2).

Forest plot of the effect of intervention in food environment school on body mass index (z-score).

Meta-analyses were performed using the WC and body fat data from the selected studies. Mean WC (cm) was significantly reduced by interventions compared to the control group (MD: -0.70; 95%CI: -1.22, -0.19; I2 = 40%; low certainty of evidence) (Figure 4). Sensitivity analysis for mean WC showed no change in effect direction after removing studies with high risk of bias, and the result remained significant (Supplementary Material - Figure S5; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf). Among the eight trials 35,46,51,52,54,55,56,80 included in the qualitative synthesis, four 35,46,52,54 found significant WC reductions, including one study 35 in which the effect was observed only in boys. Two studies 55,56 observed increases - one in the control group 55 and the other 56 in the intervention group - while the remaining studies found no significant changes 51,80. Overall, despite inconsistencies across individual trials, the meta-analyses suggest that multi-component interventions may be effective in reducing WC in children and adolescents.

Forest plot of the effect of intervention in food environment school on waist circumference (cm).

Interventions did not affect the mean %BF compared to the control group (MD: 0.21; 95%CI: -1.15, 1.58; I2 = 88%; very low certainty of evidence) (Figure 5). Sensitivity analysis did not alter the change in effect direction or significance (Supplementary Material - Figure S6; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf). In the qualitative analysis, seven studies 46,52,54,70,72,78,80 reported this outcome, and two 52,78 found a significant reduction. However, in one study 78, this reduction was only observed in boys. Consequently, the intervention does not appear to be effective in reducing %BF in children and adolescents.

Food consumption

Food consumption (fruits, vegetables, unhealthy foods), sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), and macronutrient or energy intake were assessed as outcomes in 40 studies 31,32,33,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,69,70,71,72,73,77,78,80,81 at the end of the interventions. Assessment methods were heterogeneous, using food frequency questionnaires (n = 21) 31,32,33,36,37,39,40,43,46,48,50,51,53,57,60,61,62,63,64,73,80, 24-hour recalls (n = 6) 41,44,45,49,55,71, food diaries (n = 3) 54,56,58, direct observation (n = 2) 59,77, digital photography (n = 2) 72,78, and six studies 42,66,68,69,70,81 used more than one measurement method.

Among 15 studies 32,39,40,41,42,46,48,50,51,56,62,63,64,73,80 that evaluated fruit consumption, five reported significant changes. Two studies 40,48 found a higher fruit intake in the intervention group compared to the control group at follow-up, while one study 32 reported a reduction in fruit consumption in the intervention group. In two studies 41,42, changes were observed only within the intervention group when comparing baseline to follow-up, without statistically significant differences between groups. The remaining studies 39,46,50,51,56,62,63,64,73,80 did not report significant differences between groups.

Regarding vegetable consumption, among 14 studies 32,37,39,40,41,42,48,50,56,62,63,64,73,80, five 37,40,48,64,80 found higher vegetable intake in the intervention group compared to the control group, while one study 32 reported a reduction the intervention group. In two studies 42,56, the increase was observed only within the intervention group, and in one study 41 a decrease was observed within the intervention group, with no statistically significant differences between groups. The remaining studies found no significant differences between groups.

As for unhealthy food consumption, among the nine studies that assessed this outcome 31,41,42,46,50,56,59,64,77, five 31,46,50,59,64 reported a reduction in the intervention group compared to the control group at follow-up. In three studies 41,56,77, this effect was observed only within the intervention group when comparing baseline to follow-up, rather than between groups. Only one study 42 reported an increase in unhealthy food consumption among students with overweight in the intervention group compared to baseline.

Regarding SSB consumption, four studies 39,46,50,61 observed a reduction in the intervention group, while six studies 33,43,63,64,80,81 found no differences between groups. However, one study 56 reported a higher SSB intake among children in the intervention group at follow-up compared to baseline.

According to five studies 54,55,58,70,72, school-based interventions reduced total energy intake. However, Majid et al. 54 reported similar decreases in energy intake between intervention and control groups compared to baseline, while three studies 49,66,68 found an increase. Four studies 57,73,78,81 found no differences between groups. Twelve studies 41,49,54,55,57,58,66,68,70,72,73,78 evaluated energy derived from total fat or total fat in grams per day, five studies 58,66,68,70,72 observed a reduction in the intervention group, two studies 49,54 showed increased values throughout the intervention, and five studies 41,47,55,73,78 observed no differences between groups. Four studies 55,66,68,72 also found lower saturated fat intake in schools that implemented changes in the food environment compared to controls or baseline, while two studies 71,78 did not observe this effect.

Thus, most multi-component interventions did significantly increase fruit consumption or reduce SSB intake. While some studies reported reductions in unhealthy food consumption, total fat, saturated fat, and energy intake, as well as increases in vegetable consumption, others found no significant differences or even reported increases in these outcomes.

Risk of bias among studies and certainty of evidence

Overall, the risk of bias in cRCTs ranged from low to high. Only seven trials 33,40,59,68,76,78,81 were rated as low risk. Most trials 31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,44,45,46,55,57,58,60,61,65,66,67,70,71,80 presented concerns regarding reported-result selection, deviations from intended interventions, randomization process, and high risk of bias 42,47,49,63,69,72,73,77,79. QE studies were classified as moderate 48,50,51,52,53,54,62,74,75, serious 43,64, or critical 56 risk of bias, with the most frequent domains being outcome measurement, selective outcome reporting, and uncontrolled confounding. Risk of bias assessments are summarized in Figures S7 and S8 (Supplementary Material; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf), while the overall certainty of evidence reported for each outcome is reported in Table S5 (Supplementary Material; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf).

Regarding certainty of evidence, consumption of fruits, vegetables, unhealthy foods, SSB, energy, total fat, and saturated fat was rated as moderate. BMI (z-score) and %BF were rated as very low, while BMI (kg/m2) and WC were rated as low.

Publication bias was assessed for the meta-analyses of BMI (kg/m2) and BMI z-score. Visual inspection of the funnel plot for the BMI z-score (Supplementary Material - Figure S9a; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf) suggested marked asymmetry, indicating a high potential for publication bias; however, this was not confirmed by Egger’s test (t = 0.50, df = 8, p = 0.6328). The Trim-and-Fill method (Supplementary Material - Figure S9b; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf) imputed missing studies, yielding a corrected MD of -0.043 (95%CI: -0.1347, 0.0487), which reduced the magnitude of the intervention effect while maintaining its direction (p = 0.3581). In contrast, the funnel plot for BMI (kg/m2) showed no asymmetry (Supplementary Material - Figure S10; https://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/static//arquivo/suppl-e00152824_7623.pdf), which was consistent with Egger’s test (t = 0.48, df = 15, p = 0.6366). These findings were considered in the GRADE assessment and contributed to downgrading the certainty of evidence for the BMI z-score outcome, which was rated as “strongly suspected” for publication bias.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the impact of school food-environment interventions on adiposity and food consumption outcomes in children and adolescents, including 51 studies. Multi-component interventions that modified the school food environment reduced WC and potentially improved students’ eating habits. However, caution is warranted, since the overall study quality ranged from very low to high. Risk of bias assessments revealed several methodological concerns, such as lack of blinding of outcome assessors, selection bias, and inconsistent reporting, which may have influenced the estimated effects - particularly for anthropometric measures that were often inconsistent or null. Although higher-quality studies tended to demonstrate more robust effects on dietary intake, the observed reduction in WC, despite being statistically significant, was affected by study heterogeneity and potential publication bias.

WC is a recognized indicator of abdominal obesity, specifically reflecting visceral fat accumulation, and is considered an early predictor of cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents 82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89. Although moderate correlations exist among BMI, WC, and body fat measures, these anthropometric indicators assess different aspects of body composition and should not be considered equivalent. BMI, despite its widespread use, does not distinguish fat mass from lean mass, nor does it differentiate subcutaneous from visceral fat 90. Conversely, WC is a more specific proxy for central adiposity and may be more responsive to early lifestyle modifications, making it a valuable tool for detecting metabolic syndrome in both childhood and adolescence 83,88. The lack of statistically significant effects observed for BMI and body fat in our meta-analyses may reflect the limited sensitivity of these measures to detect subtle changes over short intervention periods, particularly in samples composed mainly of healthy individuals 90,91. As highlighted by Grydeland et al. 91, more pronounced effects on adiposity-related outcomes may only become evident after longer follow-up periods.

These findings are aligned with previous systematic reviews, which have also reported inconsistent intervention effects on BMI 22,23,92,93, while small but favorable changes in WC have been more consistently observed 90. Reductions in WC may not only indicate improved adiposity outcomes but also help mitigate the physical, emotional, and economic burdens associated with NCDs. The limited effects observed may partly result from the inclusion of predominantly healthy children in these studies, emphasizing that more substantial benefits may require longer-term interventions and follow-up periods 90,91.

Regarding food consumption, the results suggest that school-based multi-component interventions positively influenced dietary behaviors by increasing vegetable intake and reducing the consumption of unhealthy foods, total fat, saturated fat, and energy. Previous studies, such as Adom et al. 92 and Van Cauwenberghe et al. 20, have provided strong evidence of improved fruit and vegetable consumption, while Verstraeten et al. 17 reported reductions in fast food intake. Additionally, Gonçalves et al. 94 noted that greater availability of healthy foods in schools was associated with a lower risk of obesity, reinforcing the importance of enhancing the school food environment. However, as Micha et al. 23 highlight, while multi-component interventions enhance dietary quality, their impact on weight outcomes may not be immediate, emphasizing the need for sustained, long-term strategies.

School-based interventions should adopt a holistic, multifaceted approach that integrates family, school, and community components 94,95,96,97,98. These interventions should target behavioral modifications by means of lifestyle changes and improvements in the school food environment, such as increasing the availability of healthy foods, restricting unhealthy foods, implementing school policies to regulate food sales, and promoting water consumption 21,22,23,92,93,99. By fostering an environment that supports healthy food choices and regular physical activity, schools can equip young individuals with knowledge and skills needed for a healthier life trajectory 100.

Nevertheless, the multi-component approach presents challenges. It is difficult to identify which specific elements drive outcomes, how these components interact, and how to implement multiple actions simultaneously 97. Given the complexity and upstream nature of food environment interventions, an inherent dilution bias may occur 22. Additionally, factors outside school - such as the home food environment, consumer behavior, attitudes, and personal preferences - can influence results 22. A single public policy has limited impact, highlighting the need for comprehensive, long-term strategies to effectively address childhood obesity 101.

The duration of interventions is crucial for its success. O’Connor et al. 102 suggest that interventions lasting 26 hours or longer can effectively reduce overweight prevalence in children and adolescents. However, establishing a precise recommendation for intervention duration remains challenging due to study heterogeneity and limited comprehensive data.

Several logistical challenges further complicate the assessment and implementation of school food environment interventions. Difficulties with randomization and blinding processes 103, barriers related to financial resources, time constraints, school staff 103,104, and competing school priorities 105 can limit implementation. Significant heterogeneity among schools in terms of size, infrastructure, economic and human resources, and sociodemographic characteristics 106, along with variations in intervention intensity, duration, frequency, and activity types 107,108,109,110,111,112, has contributed to inconsistent outcomes observed across studies.

The robustness of this systematic review is supported by extensive bibliographic research, protocol registration, no language and date restrictions, rigorous risk-of-bias assessment, evaluation of certainty of evidence, and adherence to PRISMA guidelines throughout screening and data extraction. Most interventions were randomized, which increases the reliability and validity of the findings.

Despite these strengths, some limitations should be acknowledged. The variable quality of the included studies and the heterogeneity in intervention characteristics (intensity, duration, sample size, population) precluded subgroup analyses by students’ age and sex - essential factors given the distinct physiological, cognitive, and socio-emotional developmental stages of children and adolescents. Nevertheless, a key strength is that all interventions were multi-component and specifically targeted the school food environment, which supports their combined analysis. Moreover, the low sensitivity of the search strategy, partly due to the lack of indexed descriptors related to the food environment, may have resulted in the omission of relevant studies.

Additionally, most studies were conducted in high-income countries, and some were excluded from the meta-analysis due to heterogeneity and incomplete data. Finally, most included cRCTs or QE studies did not provide sufficient information to adjust analyses for the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). Consequently, pooled estimates may not fully account for within-cluster correlation, potentially underestimating standard errors and overestimating the precision of effect sizes. To enhance the reliability of future evidence syntheses, primary studies should report ICCs and provide cluster-adjusted effect estimates.

Conclusion

Interventions targeting the school food environment offer limited evidence on their effects on adiposity and food consumption in children and adolescents. Multi-component interventions have reduced WC and may have improved dietary behaviors, although BMI results were inconsistent. The wide variability in study quality, intervention design, and implementation prevents definitive conclusions on their long-term effectiveness. Methodological limitations - such as heterogeneity in intervention components, duration, and adherence - may obscure their true impact. Improving study designs, standardizing approaches, and securing policy support are crucial to better assess and enhance these strategies for lasting health improvements.

Moreover, multi-component interventions must actively engage the entire school community to promote healthy food choices, nutrition education, and a wellness-focused lifestyle. Integrating nutrition education into the school curriculum and implementing regulatory policies that restrict unhealthy food sales and advertising while promoting healthier alternatives are fundamental for sustained impact.

Effective, policy-supported interventions foster healthier school environments and establish the foundation for lifelong healthy habits. A coordinated effort among schools, communities, policymakers, and public health stakeholders is essential for meaningful change and a healthier future for younger generations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dean of Research of Federal University of Minas Gerais (PRPq/UFMG).

References

-

1 World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on Mar/2024).

» https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1 - 2 Afshin A, Reitsma MB, Murray CJL. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1496-7.

-

3 World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and disease burden attributable to selected major risks. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44203 (accessed on Mar/2024).

» https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44203 - 4 Akseer N, Mehta S, Wigle J, Chera R, Brickman ZJ, Al-Gashm S, et al. Non-communicable diseases among adolescents: current status, determinants, interventions and policies. BMC Public Health 2020; 20:1908-20.

-

5 World Health Organization. Population based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/80149 (accessed on Mar/2024).

» https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/80149 - 6 Wolfenden L, Nathan NK, Sutherland R, Yoong SL, Hodder RK, Wyse RJ, et al. Strategies for enhancing the implementation of school-based policies or practices targeting risk factors for chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; (11):CD011677.

-

7 World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: implementation plan: executive summary. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/259349 (accessed on Mar/2024).

» https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/259349 - 8 Glanz K. Measuring food environments: a historical perspective. Am J Prev Med 2009; 36(4 Suppl):S93-8.

- 9 Hoyt LT, Kushi LH, Leung CW, Nickleach DC, Adler N, Laraia BA, et al. Neighborhood influences on girls' obesity risk across the transition to adolescence. Pediatrics 2014; 134:942-9.

- 10 Callaghan M, Molcho M, Gabhainn SN, Kelly C. Food for thought: analysing the internal and external school food environment. Health Educ 2015; 115:152-70.

- 11 Hsieh S, Klassen AC, Curriero FC, Caulfield LE, Cheskin LJ, Davis JN, et al. Built environment associations with adiposity parameters among overweight and obese Hispanic youth. Prev Med Rep 2015; 2:406-12.

- 12 Browne S, Staines A, Barron C, Lambert V, Susta D, Sweeney MR. School lunches in the Republic of Ireland: a comparison of the nutritional quality of adolescents' lunches sourced from home or purchased at school or 'out' at local food outlets. Public Health Nutr 2017; 20:504-54.

- 13 Carmo AS, Assis MM, Cunha CF, Oliveira TRPR, Mendes LL. The food environment of Brazilian public and private schools. Cad Saúde Pública 2018; 34:e00014918.

- 14 Wognski ACP, Ponchek VL, Dibas EES, Do Rocio Orso M, Vieira LP, Ferreira BGCS, et al. Commercialization of food in school canteens. Braz J Food Technol 2019; 22:e2018198.

- 15 Institute of Medicine. Nutrition standards for foods in schools: leading the way toward healthier youth. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

- 16 Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Zatz LY, Frelier JM, Ebbeling CB, Peeters A. Interventions to prevent global childhood overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6:332-46.

- 17 Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Lachat C, Leroy JL, Holdsworth M, Maes L, et al. Effectiveness of preventive school-based obesity interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 96:415-38.

- 18 Brown EC, Buchan DS, Baker JS, Wyatt FB, Bocalini DS, Kilgore L. A systematised review of primary school whole class child obesity interventions: effectiveness, characteristics, and strategies. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016:4902714.

- 19 Chavez RC, Nam EW. School-based obesity prevention interventions in Latin America: a systematic review. Rev Saúde Pública 2020; 54:110.

- 20 Van Cauwenberghe E, Maes L, Spittaels H, Van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Oppert JM, et al. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: systematic review of published and 'grey' literature. Br J Nutr 2010; 103:781-97.

- 21 Bondyra-Wisniewska B, Myszkowska-Ryciak J, Harton A. Impact of lifestyle intervention programs for children and adolescents with overweight or obesity on body weight and selected cardiometabolic factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18:2061.

- 22 Carducci B, Oh C, Keats EC, Roth DE, Bhutta ZA. Effect of food environment interventions on anthropometric outcomes in school-aged children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Dev Nutr 2020; 4:nzaa098.

- 23 Micha R, Karageorgou D, Bakogianni I, Trichia E, Whitsel LP, Story M, et al. Effectiveness of school food environment policies on children's dietary behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0194555.

- 24 Driessen CE, Cameron AJ, Thornton LE, Lai SK, Barnett LM. Effect of changes to the school food environment on eating behaviours and/or body weight in children: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2014; 15:968-82.

- 25 Mandracchia F, Tarro L, Llauradó E, Valls RM, Solà R. Interventions to promote healthy meals in full-service restaurants and canteens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021; 13:1350.

- 26 Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n71.

-

27 Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (update August 2023). https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on Nov/2023).

» https://training.cochrane.org/handbook - 28 Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health 2019; 22:153-60.

- 29 Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 2010; 36:1-48.

-

30 Schünemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. GRADE handbook. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/grade-handbook (accessed on Feb/2024).

» https://training.cochrane.org/resource/grade-handbook - 31 Herscovici RC, Kovalskys I, De Gregorio MJ. Gender differences and a school-based obesity prevention program in Argentina: a randomized trial. Rev Panam Salud Pública 2013; 34:75-82.

- 32 Chellappah J, Tonkin A, Gregg MED, Reid C. A randomized controlled trial of effects of fruit intake on cardiovascular disease risk factors in children (FIST Study). Infant Child Adolesc Nutr 2014; 7:15-23.

- 33 Ooi JY, Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, Janssen LM, Reilly K, Nathan N, et al. A trial of a six-month sugar-sweetened beverage intervention in secondary schools from a socio-economically disadvantaged region in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2021; 45:599-607.

- 34 Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L, Stevens V, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Body mass effects of a physical activity and healthy food intervention in middle schools. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14:847-54.

- 35 Kain J, Uauy R, Albala, Vio F, Cerda R, Leyton B. School-based obesity prevention in Chilean primary school children: methodology and evaluation of a controlled study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28:483-93.

- 36 Xu F, Wang X, Ware RS, Tse LA, Wang Z, Hong X, et al. A school-based comprehensive lifestyle intervention among Chinese kids against obesity (CLICK-Obesity) in Nanjing City, China: the baseline data. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2014; 23:48-54.

- 37 Xu F, Ware RS, Leslie E, Tse LA, Wang Z, Li J, et al. Effectiveness of a randomized controlled lifestyle intervention to prevent obesity among Chinese primary school students: CLICK-Obesity Study. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0141421.

- 38 Cao ZJ, Wang SM, Chen Y. A randomized trial of multiple interventions for childhood obesity in China. Am J Prev Med 2015; 48:552-60.

- 39 Liu Z, Li Q, Maddison R, Ni Mhurchu C, Jiang Y, Wei DM, et al. A school-based comprehensive intervention for childhood obesity in China: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Child Obes 2019; 15:105-15.

- 40 Li B, Pallan M, Liu WJ, Hemming K, Frew E, Lin R, et al. The CHIRPY DRAGON intervention in preventing obesity in Chinese primary-school-aged children: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2019; 16:e1002971.

- 41 Ochoa-Avilés A, Verstraeten R, Huybregts L, Andrade S, Van Camp J, Donoso S, et al. A school-based intervention improved dietary intake outcomes and reduced waist circumference in adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Nutr J 2017; 16:79.

- 42 Sahota P, Rudolf MC, Dixey R, Hill AJ, Barth JH, Cade J. Randomised controlled trial of primary school based intervention to reduce risk factors for obesity. BMJ 2001; 323:1029-32.

- 43 Kremer P, Waqa G, Vanualailai N, Schultz JT, Roberts G, Moodie M, et al. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in Fijian adolescents: results of the Healthy Youth Healthy Communities study. Obes Rev 2011; 12:29-40.

- 44 Muckelbauer R, Libuda L, Clausen K, Toschke AM, Reinehr T, Kersting M. Promotion and provision of drinking water in schools for overweight prevention: randomized, controlled cluster trial. Pediatrics 2009; 123:e661-7.

- 45 Muckelbauer R, Libuda L, Clausen K, Reinehr T, Kersting M. A simple dietary intervention in the school setting decreased incidence of overweight in children. Obes Facts 2009; 2:282-5.

- 46 Singhal N, Misra A, Shah P, Gulati S. Effects of controlled school-based multi-component model of nutrition and lifestyle interventions on behavior modification, anthropometry and metabolic risk profile of urban Asian Indian adolescents in North India. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010; 64:364-73.

- 47 Singhal N, Misra A, Shah P, Gulati S, Bhatt S, Sharma S, et al. Impact of intensive school-based nutrition education and lifestyle interventions on insulin resistance, ß-cell function, disposition index, and subclinical inflammation among Asian Indian adolescents: a controlled intervention study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2011; 9:143-50.

- 48 Kurniawan F, Prabandari YS, Ismail D, Dewi FT. Effectiveness of school-based obesity prevention programme among elementary school children in Jakarta. Mal J Nutr 2022; 28:97-106.

- 49 Amini M, Djazayery A, Majdzadeh R, Taghdisi MH, Sadrzadeh-Yeganeh H, Abdollahi Z, et al. A school-based intervention to reduce excess weight in overweight and obese primary school students. Biol Res Nurs 2016; 18:531-40.

- 50 Ermetici F, Zelaschi RF, Briganti S, Dozio E, Gaeta M, Ambrogi F, et al. Association between a school-based intervention and adiposity outcomes in adolescents: the Italian "EAT" project. Obesity 2016; 24:687-95.

- 51 Habib-Mourad C, Ghandour LA, Moore HJ, Nabhani-Zeidan M, Adetayo K, Hwalla N, et al. Promoting healthy eating and physical activity among school children: findings from Health-E-PALS, the first pilot intervention from Lebanon. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:940.

- 52 Koo HC, Poh BK, Abd Talib R. The GReat-Child(tm) Trial: a quasi-experimental intervention on whole grains with healthy balanced diet to manage childhood obesity in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Nutrients 2018; 10:156.

- 53 Teo CH, Chin YS, Lim PY, Masrom SAH, Shariff ZM. Impacts of a school-based intervention that incorporates nutrition education and a supportive healthy school canteen environment among primary school children in Malaysia. Nutrients 2021; 13:1712.

- 54 Majid HA, Ng AK, Dahlui M, Mohammadi S, Mohamed MNAB, Su TT, et al. Outcome evaluation on impact of the nutrition intervention among adolescents: a feasibility, randomised control study from Myheart Beat (Malaysian Health and Adolescents Longitudinal Research Team-Behavioural Epidemiology and Trial). Nutrients 2022; 14:2733.

- 55 Colín-Ramírez E, Castillo-Martínez L, Orea-Tejeda A, Vergara A, Villa AR. Efecto de una intervención escolar basada en actividad física y dieta para la prevención de factores de riesgo cardiovascular (RESCATE) en niños mexicanos de 8 a 10 años. Rev Esp Nutr Comunitaria 2009; 15:71-80.

- 56 Bacardí-Gascon M, Pérez-Morales ME, Jiménez-Cruz A. A six month randomized school intervention and an 18-month follow-up intervention to prevent childhood obesity in Mexican elementary schools. Nutr Hosp 2012; 27:755-62.

- 57 Levy TS, Ruán CM, Castellanos CA, Coronel AS, Aguilar AJ, Humarán IMG. Effectiveness of a diet and physical activity promotion strategy on the prevention of obesity in Mexican school children. BMC Public Health 2012; 12:152.

- 58 Alvirde-García U, Rodríguez-Guerrero AJ, Henao-Morán S, Gómez-Pérez FJ, Aguilar-Salinas CA. Results of a community-based life style intervention program for children. Salud Pública Méx 2013; 55:406-14.

- 59 Safdie M, Jennings-Aburto N, Lévesque L, Janssen I, Campirano-Núñez F, López-Olmedo N, et al. Impact of a school-based intervention program on obesity risk factors in Mexican children. Salud Pública Méx 2013; 55:374-87.

- 60 Singh AS, Chin A Paw MJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Short-term effects of school-based weight gain prevention among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161:565-71.

- 61 Singh AS, Chin A, Paw MJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Dutch obesity intervention in teenagers: effectiveness of a school-based program on body composition and behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163:309-17.

- 62 Aparco JP, Bautista-Olórtegui W, Pillaca J. Impact evaluation of educational-motivational intervention "Como Jugando" to prevent obesity in school children of Cercado de Lima: results in the first year. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública 2017; 34:386-94.

- 63 Marcus C, Nyberg G, Nordenfelt A, Karpmyr M, Kowalski J, Ekelund U. A 4-year, cluster-randomized, controlled childhood obesity prevention study: STOPP. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33:408-17.

- 64 Chawla N, Panza A, Sirikulchayanonta C, Kumar R, Taneepanichskul S. Effectiveness of a school-based multicomponent intervention on nutritional status among primary school children in Bangkok, Thailand. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2017; 29:13-20.

- 65 Sevinç Ö, Bozkurt AI, Gündogdu M, Aslan ÜB, Agbuga B, Aslan S, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of an intervention program on preventing childhood obesity in Denizli, Turkey. Turk J Med Sci 2011; 41:1097-105.

- 66 Luepker RV, Perry CL, McKinlay SM, Nader PR, Parcel GS, Stone EJ, et al. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children's dietary patterns and physical activity. The Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. CATCH collaborative group. JAMA 1996; 275:768-76.

- 67 Webber LS, Osganian SK, Feldman HA, Wu M, McKenzie TL, Nichaman M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors among children after a 2 1/2-year intervention: the CATCH Study. Prev Med 1996; 25:432-41.

- 68 Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, Perry CL, Osganian SK, Kelder S, et al. Three-year maintenance of improved diet and physical activity: the CATCH cohort. Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999; 153:695-704.

- 69 Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Conway TL, Elder JP, Prochaska JJ, Brown M, et al. Environmental interventions for eating and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial in middle schools. Am J Prev Med 2003; 24:209-17.

- 70 Caballero B, Clay T, Davis SM, Ethelbah B, Rock BH, Lohman T, et al. Pathways: a school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 78:1030-8.

- 71 Treviño RP, Yin Z, Hernandez A, Hale DE, Garcia OA, Mobley C. Impact of the Bienestar school-based diabetes mellitus prevention program on fasting capillary glucose levels: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158:911-7.

- 72 Williamson DA, Copeland AL, Anton SD, Champagne C, Han H, Lewis L, et al. Wise Mind project: a school-based environmental approach for preventing weight gain in children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15:906-17.

- 73 Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradaile KE, Grundy KM, Vander Veur SS, Nachmani J, et al. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics 2008; 121:e794-802.

- 74 Hollar D, Lombardo M, Lopez-Mitnik G, Hollar TL, Almon M, Agatston AS, et al. Effective multi-level, multi-sector, school-based obesity prevention programming improves weight, blood pressure, and academic performance, especially among low-income, minority children. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010; 21:93-108.

- 75 Hollar D, Messiah SE, Lopez-Mitnik G, Hollar TL, Almon M, Agatston AS. Healthier options for public schoolchildren program improves weight and blood pressure in 6- to 13-year-olds. J Am Diet Assoc 2010; 110:261-7.

- 76 Foster GD, Linder B, Baranowski T, Cooper DM, Goldberg L, Harrell JS, et al. A school-based intervention for diabetes risk reduction. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:443-53.

- 77 Coleman KJ, Shordon M, Caparosa SL, Pomichowski ME, Dzewaltowski DA. The healthy options for nutrition environments in schools (Healthy ONES) group randomized trial: using implementation models to change nutrition policy and environments in low income schools. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012; 27:80.

- 78 Williamson DA, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Han H, Martin CK, Newton Jr. RL, et al. Effect of an environmental school-based obesity prevention program on changes in body fat and body weight: a randomized trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012; 20:1653-61.

- 79 Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Cowgill BO, Klein DJ, Hawes-Dawson J, Uyeda K, et al. Two-year BMI outcomes from a school-based intervention for nutrition and exercise: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2016; 137:e20152493.

- 80 Davis JN, Pérez A, Asigbee FM, Landry MJ, Vandyousefi S, Ghaddar R, et al. School-based gardening, cooking and nutrition intervention increased vegetable intake but did not reduce BMI: Texas sprouts - a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys 2021; 18:18.

- 81 Patel AI, Schmidt LA, McCulloch CE, Blacker LS, Cabana MD, Brindis CD, et al. Effectiveness of a School drinking water promotion and access program for overweight prevention. Pediatrics 2023; 152:e2022060021.

- 82 Freedman DS, Serdula MK, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relation of circumferences and skinfold thicknesses to lipid and insulin concentrations in children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69:308-17.

- 83 Taylor RW, Jones IE, Williams SM, Goulding A. Evaluation of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and the conicity index as screening tools for high trunk fat mass, as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, in children aged 3-19 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72:490-5.

- 84 McCarthy HD, Jarrett KV, Crawley HF. The development of waist circumference percentiles in British children aged 5.0-16.9 y. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001; 55:902-7.

- 85 Burgos MS, Burgos LT, Camargo MD, Franke SI, Prá D, Silva AM, et al. Relationship between anthropometric measures and cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents. Arq Bras Cardiol 2013; 101:288-96.

- 86 Quadros TMB, Gordia AP, Silva LR. Anthropometry and clustered cardiometabolic risk factors in young people: a systematic review. Rev Paul Pediatr 2017; 35:340-50.

- 87 Wicklow BA, Becker A, Chateau D, Palmer K, Kozyrskij A, Sellers EA. Comparison of anthropometric measurements in children to predict metabolic syndrome in adolescence: analysis of prospective cohort data. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015; 39:1070-8.

- 88 Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, Kourides Y, Panagi A, Silikiotou N, et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24:1453-8.

- 89 Bitsori M, Linardakis M, Tabakaki M, Kafatos A. Waist circumference as a screening tool for the identification of adolescents with the metabolic syndrome phenotype. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009; 4:325-31.

- 90 Kula A, Brender R, Bernartz KM, Walter U. Waist circumference as a parameter in school-based interventions to prevent overweight and obesity - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024; 24:2864.

- 91 Grydeland M, Bjelland M, Anderssen SA, Klepp K-I, Bergh IH, Andersen LF, et al. Effects of a 20-month cluster randomised controlled school-based intervention trial on BMI of school-aged boys and girls: the HEIA study. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48:768-73.

- 92 Adom T, De Villiers A, Puoane T, Kengne AP. School-based interventions targeting nutrition and physical activity, and body weight status of African children: a systematic review. Nutrients 2019; 12:95.

- 93 Downs S, Demmler KM. Food environment interventions targeting children and adolescents: a scoping review. Glob Food Sec 2020; 27:100403.

- 94 Gonçalves VSS, Figueiredo ACMG, Silva SA, Silva SU, Ronca DB, Dutra ES, et al. The food environment in schools and their immediate vicinities associated with excess weight in adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Place 2021; 71:102664.

- 95 Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- 96 Pérez-Rodrigo C, Aranceta J. School-based nutrition education: lessons learned and new perspectives. Public Health Nutr 2001; 4:131-9.

- 97 Brug J, Kremers SP, van Lenthe F, Ball K, Crawford D. Environmental determinants of healthy eating: in need of theory and evidence. Proc Nutr Soc 2008; 67:307-16.

- 98 Swerissen H, Crisp BR. The sustainability of health promotion interventions for different levels of social organization. Health Promot Int 2004; 19:123-30.

-

99 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/index.htm (accessed on Mar/2024).

» https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/index.htm - 100 Merten MJ. Weight status continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: examining disease and health risk conditions. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010; 187:1423-8.

- 101 Duran AC, Mialon M, Crosbie E, Jensen ML, Harris JL, Batis C, et al. Food environment solutions for childhood obesity in Latin America and among Latinos living in the United States. Obes Rev 2021; 22:e13361.

- 102 O'Connor EA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Walsh ES, Eder M, Lozano P. Screening for obesity and intervention for weight management in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2017; 317:2427-44.

-

103 Ladd HF. How School districts respond to fiscal constraint. SSRN 1997; 26 nov. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=31743

» https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=31743 -

104 Leachman M, Masterson K, Figueroa E. A punishing decade for school funding. https://www.cbpp.org/research/a-punishing-decade-for-school-funding (accessed on Mar/2024).

» https://www.cbpp.org/research/a-punishing-decade-for-school-funding - 105 Anderson PM, Butcher KF, Schanzenbach DW. Adequate (or adipose?) yearly progress: assessing the effect of 'no child left behind' on children's obesity. Educ Finance Policy 2011; 12:54-76.

- 106 Keshavarz N, Nutbeam D, Rowling L, Khavarpour F. Schools as social complex adaptive systems: a new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70:1467-74.

- 107 Evans A, Ranjit N, Rutledge R, Medina J, Jennings R, Smiley A, et al. Exposure to multiple components of a garden-based intervention for middle school students increases fruit and vegetable consumption. Health Promot Pract 2012; 13:608-16.

- 108 Fulkerson JA, French SA, Story M, Nelson H, Hannan PJ. Promotions to increase lower-fat food choices among students in secondary schools: description and outcomes of TACOS (Trying Alternative Cafeteria Options in Schools). Public Health Nutr 2004; 7:665-74.

- 109 Wang MC, Rauzon S, Studer N, Martin AC, Craig L, Merlo C, et al. Exposure to a comprehensive school intervention increases vegetable consumption. J Adolesc Health 2010; 47:74-82.

- 110 Wells NM, Myers BM, Todd LE, Barale K, Gaolach B, Ferenz G, et al. The effects of school gardens on children's science knowledge: a randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. Int J Sci Educ 2015; 37:2858-78.

- 111 Jones SJ, Childers C, Weaver AT, Ball J. SC farm-to-school programs encourages children to consume vegetables. J Hunger Environ Nutr 2015; 10:511-25.

- 112 Prescott MP, Cleary R, Bonanno A, Costanigro M, Jablonski BBR, Long AB. Farm to school activities and student outcomes: a systematic review. Adv Nutr 2020; 11:357-74.

Edited by

Data availability

The sources of information used in the study are indicated in the body of the article.

Supplementary Material

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

01 Dec 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

22 Oct 2024 -

Reviewed

25 July 2025 -

Accepted

30 July 2025

Impact of multi-component school food environment interventions on adiposity and food consumption in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis

Impact of multi-component school food environment interventions on adiposity and food consumption in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. * Boys’ values; ** Girls’ values.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. * Boys’ values; ** Girls’ values.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. * Boys’ values; ** Girls’ values.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. * Boys’ values; ** Girls’ values.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. * Boys’ values; ** Girls’ values.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. * Boys’ values; ** Girls’ values.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation.