ABSTRACT

Sugarcane field renewal is usually carried out using conventional soil tillage, followed by sugarcane planting or by soybean cultivation or cover cropping. However, efforts have often been made to reduce the intensive operations involved in conventional soil preparation. The objective of this study was to evaluate the physical quality of the soil under conventional tillage (CT) and no-tillage (NT) systems after a sugarcane harvest cycle, before soil preparation and after four months of cultivation of Crotalaria juncea intercropped with Urochloa ruzizienses cv. Xaraés. This study was conducted in the municipality of Juti, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, on a dystrophic psammitic Red Latosol. A randomized block design was used in a split-plot scheme with thirty replications. The main plots consisted of two soil management systems, and the subplots corresponded to evaluation periods (before and after soil preparation and cover crop cultivation). The assessed attributes were soil bulk density (BD), macroporosity (Ma), microporosity (Mi), and total porosity (TP), as well as soil penetration resistance (PR) and soil moisture (SM). The CT promoted greater reductions in soil bulk density and penetration resistance, as well as increases in total porosity and macroporosity in deeper soil layers, compared to NT, which showed improvements particularly in the surface layer. In areas with no chemical or biological limitations in the soil profile, the adoption of NT combined with the cultivation of Crotalaria juncea intercropped with Urochloa ruzizienses cv. Xaraés, is recommended to improve the physical quality of the soil for sugarcane cultivation.

sandy soils; soil degradation; soil tillage; soil use

INTRODUCTION

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) is one of the largest crops produced in the world, cultivated in over 100 countries. Approximately 83% of sugarcane production is concentrated in ten countries (FAO, 2021), where Brazil is the leading producer, with an area of around 10 million hectares, producing 654 million megagrams, which represents 40% of global production. In addition, it is the second largest producer of bioethanol, accounting for 29.7 billion liters of ethanol from sugarcane (Conab, 2021). Ethanol derived from sugarcane can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 85% compared to emissions generated by the burning of fossil fuels (Barbosa et al., 2019).

Although sugarcane is acknowledged as one of the most sustainable crops for biofuel production, the expansion of its cultivated area, combined with the current soil and crop management practices, has generated controversial issues regarding its sustainability (Baquero et al., 2012; Arcoverde et al., 2019a; Cherubin et al., 2021). This is particularly because of critical changes in the structural quality of the soil, which puts at risk its physical functions and, consequently, affects the growth, development, and productivity of sugarcane (Baquero et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2019; Arcoverde et al., 2023).

Sugarcane cultivation in Brazil has expanded its planting area to degraded pastures and sandy soils. Sugarcane field renewal is typically carried out after five or more harvest cycles, with conventional soil tillage, followed by sugarcane planting, soybean cultivation, or a cover crop (Moraes et al., 2022). Regarding sugarcane planting, conventional tillage is carried out through successive plowing and harrowing, which causes disturbances and changes in its structure (Arcoverde et al., 2019b; Farhate et al., 2022). This system involves soil preparation through plowing, harrowing, and subsoiling operations, with the aim of reducing soil compaction, incorporating limestone and fertilizers, controlling pests, and leveling the terrain (Barbosa, 2013). However, recent works indicate that soil management can negatively affect physical properties related to soil structure, such as apparent density, penetration resistance, and porosity (Silva Junior et al., 2013; Marasca et al., 2015; Arcoverde et al., 2019b). These changes caused by soil management can influence organic matter content (Bordonal et al., 2018), thermal fluctuations in the surface layers (Santos et al., 2022), water infiltration, water content conservation (Santos et al., 2022), erosion control (Valim et al., 2016), and susceptibility to soil compaction (Castioni et al., 2019). These changes directly impact soil conditions, root growth and development, productivity, quality, and longevity of sugarcane (Melo et al., 2020).

Experiments for proposing conservation practices for soil management in different soil and climate environments for sugarcane production are essential for sustainability, especially in environments under physical and/or chemical restrictions and under water deficit at certain times of the year (Arcoverde et al., 2023). In this context, the no-tillage system can be a viable alternative and its use has shown promising results regarding sugarcane productivity and also because it is a more economical form of cultivation when compared to the conventional preparation system (Arcoverde et al., 2019b; Arcoverde et al., 2023).

Several works emphasize the importance of monitoring physical quality throughout the sugarcane growing cycle, either through a general soil physical quality index (Cherubin et al., 2016; Farhate et al., 2022) or by assessing individual changes in physical properties (Castioni et al., 2019; Barbosa et al., 2019; Awe et al., 2020). Bulk density, porosity, and soil penetration resistance are physical properties that are sensitive to changes induced by management practices and are frequently used to characterize soil compaction in agricultural areas (Arcoverde et al., 2019b; Arcoverde et al., 2019b). Furthermore, bulk density can indirectly reflect aeration, strength, and water storage and transmission capacity in the soil (Reynolds et al., 2009). Regarding pore size distributions, macroporosity is related, albeit indirectly, to the soil's ability to rapidly drain excess water and facilitate root proliferation (Reynolds et al., 2009). In addition to being used as a measure of compaction, soil penetration resistance also serves as an indicator of root penetration and growth capacity (Valadão et al., 2015; Sá et al., 2016; Barbosa et al., 2019). Soil structure regulates water retention and infiltration, gas exchange, organic matter and nutrient dynamics, root penetration, and susceptibility to erosion, making it an important indicator of soil physical quality (Rabot et al., 2018).

To meet the global demand for biofuels and support national public policies and international agreements aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions through the use of biofuels, sugarcane production areas are likely to increase significantly in the coming years. This expansion should not have negative impacts on economic and environmental sustainability; therefore, it is essential to use conservation strategies that allow soil management practices without jeopardizing soil physical quality. Thus, quantifying and monitoring the agronomic and environmental impacts of different management systems on sugarcane crops in the long term is essential to identify the system that contributes most to the sustainability of sugarcane production (Martíni et al., 2023).

The objective of this work was to evaluate the physical quality of the soil, under conventional tillage (CT) and no-tillage (NT) systems, after a sugarcane harvest cycle, before soil preparation, and after four months of cultivation of Crotalaria juncea intercropped with Urochloa ruzizienses cv. Xaraés.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Location, climate, and soil

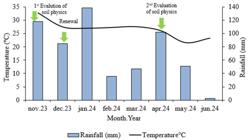

The experiment was conducted on Soebe Farm, located in the municipality of Juti, state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil (22°41′11.6″S, 54°32′30.0″W), at 375 m above sea level (Figure 1). The climate of the region, according to the Köppen-Geiger classification, is Cwa, humid mesothermal, with hot summers and dry winters (Fietz et al., 2017). Monthly rainfall data were collected using a rain gauge located in the experimental area, and air temperature data were obtained from the database of the Mato Grosso do Sul Weather and Climate Monitoring Center (CEMTEC), available at https://www.cemtec.ms.gov.br/ (Figure 2). The soil in the area is classified as psammitic dystrophic Red Latosol (Santos et al., 2018), with 856 g kg-1 of sand, 57 g kg-1 of silt and 87 g kg-1 of clay in the 0.00 to 0.10 m layer; 857 g kg-1 of sand, 51 g kg-1 of silt and 92 g kg-1 of clay in the 0.10 to 0.20 m layer; and 842 g kg-1 of sand, 50 g kg-1 of silt and 108 g kg-1 of clay in the 0.20 to 0.40 m layer.

Experimental Design

The experimental design was randomized blocks, in a split-plot scheme with thirty replications. The plots were composed of management systems (conventional tillage and non-tillage system), and the subplots by evaluation periods: before and after sugarcane renewal. The experimental plots were composed of eight sugarcane rows spaced 1.5 m apart and 10 meters long (120 m2).

Records of the area and experimental setting and conduction

The experiment was set in January 2018, after the application of limestone, gypsum, and thermophosphate, and incorporation with an intermediate harrow in part of the area and a moldboard plow in another part, followed by subsoiling and leveling harrowing. Subsequently, in February 2018, sugarcane, variety SP 832847, was manually planted. Five sugarcane cuts were then made, with crop residues remaining on the soil surface.

The sugarcane field was renewed in December 2023, with the application of 6 Mg ha-1 of dolomitic limestone, 3 Mg ha-1 of agricultural gypsum, and 450 kg ha-1 of reactive natural phosphate (27% total P2O5 and 10% citric acid-soluble P2O5) after the harvest. In part of the area (tillage system), the ratoon crop was desiccated with glyphosate and 2,4-D; and in another part (conventional preparation), following soil preparation operations were performed: Disc-harrow to chop the straw and rhizomes of the previous sugarcane crop at a depth of approximately 25 cm; Moldboard-plowing for incorporation of soil amendments and crop residues, at an approximate depth of 45 cm; Leveling-disc harrow to prepare the soil for the planting of cover crops (Figure 3).

Limestone broadcast application (A); moldboard ploughing (B); Leveling-disc harrow (C); cover crop sowing (D); cover crop management (E); cover crop cultivation (F).

Soil sampling

A few days after the mechanized harvest of the last ratoon crop, in December 2023, and four months after the planting of crotalaria intercropped with brachiaria, in April 2024, soil samples were collected in trenches measuring 0.60 m long, 0.40 m wide, and 0.60 m deep. Samples with preserved structure were collected in metal cylinders (0.0557 m in diameter and 0.0441 m high) for analysis of soil density and porosity (total, macroporosity, and microporosity) in the 0.00-0.10 m, 0.10-0.20 m, and 0.20-0.30 m layers. Simultaneously, disturbed soil samples were collected in each experimental unit and transported in thermal boxes to the laboratory for the determination of soil moisture by the gravimetric method (Teixeira et al., 2017).

Soil physical analysis

Apparent density and porosity (total, macroporosity, and microporosity) were determined in samples with preserved structure, according to the methodologies described in Teixeira et al. (2017).

The evaluation of soil penetration resistance was carried out in each experimental unit, using the PenetroLOG-PLG 1020 field penetrometer, with electronic capacity for data acquisition (ASABE, 2006). The objective was to determine the average penetration resistance (PR) stratified in the layers of 0.00-0.10 m, 0.10-0.20 m, and 0.20-0.30 m, and at each depth, five sampling points were selected.

Statistical analysis

The results of the soil physical attributes were subjected to analysis of variance and the means were compared using the test of Tukey (p<0.05), with the aid of the AgroEstat statistical program (Barbosa & Maldonado Júnior, 2015).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed the effects of soil management systems (SMS) and evaluation periods on physical attributes across three distinct layers. A significant interaction effect of the factors (SMS × periods) was observed for the variables density and total porosity in the 0.00 to 0.30 m layer; and for macroporosity and RP in the 0.00 to 0.20 m layer. Furthermore, both the management system and the evaluation period had a greater influence on the variables in the 0.00 to 0.10 m layer (Table 1).

The analyses of soil samples collected 70 months after the experiment setting up (before the renewal of the sugarcane field) showed that the soil management system did not influence density and macroporosity in the 0.00 to 0.10; 0.10 to 0.20 and 0.20 to 0.30 m layers (Table 2).

Mean values for soil density and macroporosity in soil management systems effects evaluated in two periods (before and after four months of crotalaria intercropped with brachiaria cultivation).

This similarity in the results of density and macroporosity between the different management systems in a sugarcane cycle indicates a comparable soil physical quality between the no-tillage and conventional tillage systems. This may be associated with the inherent complexity of these systems and the time elapsed since their implementation (Blanco-Canqui & Ruis, 2018).

On the other hand, four months after the cultivation of crotalaria intercropped with brachiaria, an influence of the management was observed, with a reduction in density (in the 0.00 to 0.10; 0.10 to 0.20 and 0.20 to 0.30 m layers) and an increase in macroporosity (in the 0.00 to 0.10 and 0.10 to 0.20 m layers) in the conventional tillage area, concerning the no-tillage area.

Barbosa et al. (2019) reported that in areas of sugarcane cultivated in a conventional tillage system, the tillage operations promote a temporary reduction in soil density by increasing macroporosity. However, this macroporosity tends to decrease over time, increasing soil density. Nevertheless, Martíni et al. (2023), in evaluating the physical quality of soils cultivated with sugarcane in different long-term soil management systems, during the sugarcane renewal period, after the soybean harvest, did not identify this expected reduction in soil density, nor the increase in macroporosity.

When evaluating the evaluation periods (before and after four months of cultivation of crotalaria intercropped with brachiaria), a reduction in density values (in all evaluated layers) and an increase in macroporosity (up to 0.20 m deep) were observed in the conventional soil preparation system. However, this result was not observed in the no-tillage area, which is possibly due to the lower expected development of Xaraés grass resulting from the low amount of rainfall recorded during the period (Figure 2); therefore contradicting the results found by Tavares Filho et al. (2010) who verified the influence of the root system of brachiaria in the reduction of macroporosity in sandy soil, up to 0.20 m deep, which according to the authors, improves the effective diffusion of oxygen and drainage of rainwater in the soil profile, and corresponds to a lower risk of erosion.

It was observed that the mean macroporosity values ranged from 0.10 to 0.22 m3 m-3 in conventional tillage, in the 0.00 to 0.10 m layer, while in the no-tillage, this amplitude was smaller, from 0.12 to 0.15 m3 m-3. It is noteworthy that surface soil consolidation is expected in the no-tillage system, considering that, in this management, there is no soil disturbance (Ale et al., 2023). It should be observed that the macroporosity values are greater than 0.10 m3 m-3, which is a value indicated as related to the lack of aeration and reduced productivity (Arcoverde et al., 2019b), due to insufficient root aeration and a reduction in the water content in the optimum soil water range. However, the macro (Table 2) and micropore (Table 3) values are slightly similar in the conventional tillage area, four months after planting cover crops; according to Tavares Filho et al. (2010), this indicates that, in terms of soil porosity, the conditions for plant development may be unfavorable in conventional tillage.

Regarding the soil density values at the topsoil (0.00 to 0.10 m), a variation of 1.47 to 1.75 Mg m-3 was observed in the tillage system, and the no-tillage system, they ranged from 1.66 to 1.73 Mg m-3. Souza et al. (2015) found an average soil density of 1.62 Mg m-3, which is a value close to the mean obtained in the conventional tillage area. Tavares Filho et al. (2010), in evaluating changes in particular indicators of the physical quality of a sandy, psammitic dystrophic Red Latosol under sugarcane cultivation, found maximum density values of 1.61 Mg m-3 in the 0.0 to 0.20 m layer, indicating that these values did not indicate high compaction that could restrict the growth and development of plant root systems or cause problems in terms of water infiltration, soil aeration, or restriction of biological activity. However, according to Viana et al. (2023), soil density values ranging from 1.60 to 1.70 Mg m-3 are at the threshold that can restrict crop root growth. According to Barbosa et al. (2018), the sugarcane root system is severely restricted in sandy soils when density exceeds 1.70 Mg m-3. Bonelli et al. (2011), working with a Red Yellow Latosol, with 696 g kg-1 of sand; 66 g kg-1 of silt, and 238 g kg-1 of clay, evaluated the effects of compaction on Piatã and Mombasa grasses, observing a reduction in Mombasa grass production with increasing soil density, ranging from 1.0 to 1.6 Mg m-3. Similarly, Pacheco et al. (2015) investigated the effects of different density levels (1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 Mg m-3) in a dystrophic Red Latosol, with 549 g kg-1 of sand; 84 g kg-1 of silt and 367 g kg-1 of clay, evaluating the growth of aerial parts and roots of Crotalaria species. The results showed that densities higher than 1.4 Mg m⁻3 jeopardized the growth of both aerial parts and roots of the species studied. Thus, it is clear that management practices with cover crops in no-tillage were not efficient in reducing soil compaction; on the other hand, in the conventional tillage area, soil turning was efficient in reducing compaction in the surface layer of the soil in the area of this experiment.

Samples of the sandy soil analyses before planting cover crops did not demonstrate the influence of the soil management system on microporosity and total porosity (Table 3) in any of the assessed layers; however, four months later, a significant effect of the management system was observed when analyzing total porosity in all layers evaluated, with an increase in the mean values in the conventional tillage area, possibly attributed to the higher macroporosity values (Table 2).

When evaluating the evaluation periods, it was observed that the cultivation of cover crops provided a significant increase in total porosity in all layers evaluated, but only when conventional tillage was carried out.

The mean values for microporosity varied slightly between 0.19 and 0.21 m3 m-3, which are less than those found by Moraes et al. (2022), who investigated the effect of different management systems (conventional tillage + sugarcane; conventional tillage + soybean; conventional tillage + cover crop) in a renovation area, evaluating the physical quality of the soil, 36 months after the renovation period, where the microporosity values between 0.30 and 0.35 m3 m-3 up to 0.40 m were found. However, they found critical macroporosity values of less than 0.06 m3 m-3, which would relatively explain the high microporosity values. This fact indicates a likely trend of physical degradation of the soil, due to its compaction, possibly in a process of physical degradation of the structure at a more advanced stage, concerning the soil in this work. However, the results obtained for the physical attributes of the soil in this experiment still indicate the need to adopt management practices to minimize soil compaction, as emphasized by Viana et al. (2023).

The assessments of soil resistance to penetration and soil moisture, before planting cover crops, do not demonstrate the influence of the management studied on these physical-hydric attributes (Table 4), in any of the assessed layers. Arcoverde et al. (2019b) state that conventional tillage, combined with machine traffic, results in an increase in soil resistance to penetration. Furthermore, Moraes et al. (2013) indicate that the increase in compaction at greater depths is directly related to the increase in the number of machine passages.

On the other hand, after four months of cover crop cultivation, a significant effect of the management system on soil penetration resistance was observed; a significant reduction was observed in the mean values obtained in the CT concerning the NT, in the 0.00 to 0.10 and 0.10 to 0.20 m layers, which is consistent with the lowest density (Table 2) and highest macroporosity (Table 2) and total porosity values (Table 3). These results corroborate those found by Tavares Filho et al. (2010) when evaluating a psammitic, sandy, dystrophic Red Latosol in northwestern Paraná, Brazil, in different agricultural uses. Thus, conventional tillage during renovation provided greater disturbance of the surface soil layer, causing changes in the structure, therefore significantly influencing the values of density, macroporosity, total porosity, and soil penetration resistance. Regarding this indicator, the result was likely to have been more influenced by the structure as soil moisture was not influenced by the management systems (Table 4).

This result can be attributed to the decrease in soil cohesion under conventional tillage systems (Machado et al., 2023). According to Arcoverde et al. (2020), the greater soil resistance to penetration observed in the no-tillage system is the result of the absence of soil disturbance, associated with the pressures generated by machine traffic and the rearrangement of soil particles.

It is highlighted, in general, that the results observed for penetration resistance, regarding the effect of treatments, were not similar to those observed for soil moisture; on the contrary, concerning the evaluation periods, it was found that, after renovation, despite the lower mean values of soil moisture, the penetration resistance values were either maintained or higher in the same treatments. This fact reinforces the effects of management practices, to the detriment of soil moisture, on soil resistance to penetration.

The mean values of soil resistance to penetration, before planting of the cover crops, in both management systems, ranged from 1.78 to 3.45 MPa, in the 0.00 to 0.30 m layer. However, four months later, the values ranged from 0.98 to 3.39 MPa, showing significant reductions, especially in the conventional tillage area, in the 0.00 to 0.10 and 0.10 to 0.20 m layers; and the no-tillage area, only in the 0.00 to 0.10 m layer. Except in the topsoil (0.00 to 0.10 m), in general, it is observed that the values of soil resistance to penetration are high for sandy soils cultivated with sugarcane, according to Barbosa et al. (2018), when pointing out that values greater than 1.5 MPa are considered critical as they represent severe restrictions on sugarcane root growth. A value of 2 MPa for soil penetration resistance is widely considered high for plant root growth. However, the critical resistance value can vary considerably according to soil texture, structural conditions, soil management system, and crop (Tavares Filho et al., 2010). It is noteworthy that the fact that the conventional tillage system alleviated soil compaction may have been an occasional effect, persisting only during the sugarcane-plant cycle, indicating that the intense machinery traffic carried out during sugarcane harvesting can cancel out the effects of soil preparation practices (Barbosa et al., 2019).

CONCLUSIONS

The physical quality of the soil was similar under both no-tillage and conventional tillage systems following the cultivation of Crotalaria juncea intercropped with Urochloa ruzizienses, prior to the establishment of the new sugarcane crop.

Conventional soil preparation during the renewal period led to significant improvements in soil physical properties compared to the pre-renewal condition, including reductions in soil bulk density (up to 0.30 m) and penetration resistance (up to 0.20 m), as well as increases in total porosity (up to 0.30 m) and macroporosity (up to 0.20 m).

The no-tillage system, after the renewal period, when compared to the evaluation conducted before renewal, resulted in significant reductions in soil bulk density and penetration resistance (up to 0.10 m), as well as a significant increase in macroporosity (up to 0.10 m).

The results indicate that the no-tillage system, combined with the cultivation of Crotalaria juncea intercropped with Urochloa ruzizienses during the renewal period, can be effectively adopted to enhance soil physical quality.

Means followed by lower case letters in the row and upper case letters in the columns are not different from each other by the test of Tukey at 5% of probability. CT: conventional tillage; NT: no-tillage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Raízen/Polo MS and Embrapa are gratefully acknowledged for the financial support of this work through the project FAPED/CPAO/RAÍZEN 30.21.90.028.00.00

REFERENCES

-

Ale, L. P., Arcoverde, S. N. S., Souza, C. M. A., Crestani, A. F., Rafull, L. Z. L. (2023). Evaluation of tractor traffic on soil physical properties and their relationship with white oat yield in no-tillage. Revista de Ciências Agroveterinárias, 22(4), 674–683. https://doi.org/10.5965/223811712242023674

» https://doi.org/10.5965/223811712242023674 -

Arcoverde, S. N. S., Kurihara, C. H., Staut, L. A., Tomazi, M., Pires, A. M. M., & da Silva, C. J. (2023). Soil fertility, nutritional status, and sugarcane yield under two systems of soil management, levels of remaining straw and chiseling of ratoons. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 47, e0220138. https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20220138

» https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20220138 -

Arcoverde, S. N. S., Souza, C. M. A., Cortez, J. W., Maciak, P. A. G., Suárez, A. H. T. (2019a). Soil physical attributes and production components of sugarcane cultivars in conservationist tillage systems. Engenharia Agrícola, 39, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-eng.agric.v39n2p216-224/2019

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-eng.agric.v39n2p216-224/2019 -

Arcoverde, S. N. S., Souza, C. M. A., Rafull, L. Z. L., Cortez, J. W., Orlando, R. C. (2020). Soybean agronomic performance and soil physical attributes under tractor traffic intensities. Engenharia Agrícola, 40, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v40n1p113-120/2020

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v40n1p113-120/2020 -

Arcoverde, S. N. S., Souza, C. M. A., Suárez, A. H. T., Colman, B. A., Nagahama, H. J. (2019b). Atributos físicos do solo cultivado com cana-de-açúcar em função do preparo e época de amostragem. Revista de Agricultura Neotropical, 6(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.32404/rean.v6i1.2761

» https://doi.org/10.32404/rean.v6i1.2761 - American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. (2006). Soil cone penetrometer (ASAE Standard S313.3 FEB04, pp. 902-904). ASABE.

-

Awe, G. O., Reichert, J. M., & Fontanela, E. F. (2020). Sugarcane production in the subtropics: Seasonal changes in soil properties and crop yield in no-tillage, inverting and minimum tillage. Soil & Tillage Research, 196, 104447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104447

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104447 -

Baquero, J. E., Ralisch, R., Conti, M., Tavares Filho, C., Guimarães, M. F. (2012). Soil physical properties and sugarcane root growth in a red oxisol. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 36, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832012000100007

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832012000100007 - Barbosa, J. C., & Maldonado Junior, W. (2015). AgroEstat - Sistema para análises estatísticas de ensaios agronômicos (396 p.). FCAV/UNESP.

-

Barbosa, L. C., Magalhães, P. S. G., Bordonal, R. O., Cherubin, M. R., Castioni, G. A. F., Tenelli, S., Franco, H. C. J., & Carvalho, J. L. N. (2019). Soil physical quality associated with tillage practices during sugarcane planting in south-central Brazil. Soil & Tillage Research, 195, 104383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104383

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104383 -

Barbosa, L. C., Souza, Z. M. de, Franco, H. C. J., Otto, R., Rossi Neto, J., Garside, A. L., & Carvalho, J. L. N. (2018). Soil texture affects root penetration in Oxisols under sugarcane in Brazil. Geoderma Regional, 13, 15-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2018.03.002

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2018.03.002 - Barbosa, V. F. A. M. (2013). Sistemas de plantio. In F. Santos & A. Borém (Orgs.), Cana-de-açúcar: Do plantio à colheita (pp. 27-48). Editora UFV.

-

Blanco-Canqui, H., Ruis, S. J. (2018). No-tillage and soil physical environment. Geoderma, 326, 164–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.03.011

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.03.011 - Bonelli, E. A., Bonfim-Silva, E. A., Cabral, C. E. A., Campos, J. J., Scaramuzza, W. M. L. P., & Polizel, A. C. (2011). Compactação do solo: Efeitos nas características produtivas e morfológicas dos capins Piatã e Mombaça. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 15 (3), 264-269.

-

Bordonal, R. O., Menandro, L. M. S., Barbosa, L. C., Lal, R., Milori, M. B. P., Kolln, O. T., Franco, H. C. J., & Carvalho, J. L. N. (2018). Sugarcane yield and soil carbon response to straw removal in south-central Brazil. Geoderma, 328, 79-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.05.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.05.003 -

Castioni, G. A. F., Cherubin, M. R., Bordonal, R. O., Barbosa, L. C., Menandro, L. M. S., & Carvalho, J. L. N. (2019). Straw removal affects soil physical quality and sugarcane yield in Brazil. BioEnergy Research, 12, 789-800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-019-10000-1

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-019-10000-1 -

Centro de Monitoramento do Tempo e do Clima de MS. (2024). Banco de dados. https://www.cemtec.ms.gov.br/boletins-meteorologicos/

» https://www.cemtec.ms.gov.br/boletins-meteorologicos/ -

Cherubin, M. R., Carvalho, J. L. N., Cerri, C. E. P., Nogueira, L. A. H., Souza, G. M., & Cantarella, H. (2021). Land use and management effects on sustainable sugarcane-derived bioenergy. Land, 10 (1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010072

» https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010072 -

Cherubin, M. R., Karlen, D. L., Franco, A. L., Tormena, C. A., Cerri, C. E., Davies, C. A., & Cerri, C. C. (2016). Soil physical quality response to sugarcane expansion in Brazil. Geoderma, 267, 156-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.01.004

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.01.004 - Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. (2021). Cana-de-açúcar: Acompanhamento da safra brasileira 2020/2021 (Vol. 7, p. 57).

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2021). FAOSTAT. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

» http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data -

Farhate, C. V. V., Souza, Z. M., Cherubin, M. R., Lovera, L. H., Oliveira, I. N., Guimarães Júnnyor, W. S., & Scala Junior, N. L. (2022). Soil physical change and sugarcane stalk yield induced by cover crop and soil tillage. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 46, e0210123. https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20210123

» https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20210123 - Fietz, C. R., Fisch, G. F., Comunello, E., & Flumignan, D. L. (2017). O clima da região de Dourados, MS (Série Documentos, 138). Embrapa Agropecuária Oeste.

-

Machado, T. M., Souza, C. M. A. de, Arcoverde, S. N. S., Chagas, A., Olszevski, N., & Cortez, J. W. (2023). Níveis de compactação e sistemas de preparo sobre atributos físicos do solo e componentes de produção da soja. Agrarian, 16 (56), e17037. https://doi.org/10.30612/agrarian.v16i56.17037

» https://doi.org/10.30612/agrarian.v16i56.17037 -

Marasca, I., Lemos, S. V., Silva, R. B., Guerra, S. P. S., Lanças, K. P. (2015). Soil compaction curve of an Oxisol under sugarcane planted after in-row deep tillage. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 39(5), 1490–1497. https://doi.org/10.1590/01000683rbcs20140559

» https://doi.org/10.1590/01000683rbcs20140559 -

Martíni, A., Valani, G., Silva, L. F. S., Paula, S. de, Bolonhezi, D., & Cooper, M. (2023). Soil physical quality response to management systems in a long-term sugarcane trial. Land Degradation & Development, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4988

» https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4988 -

Melo, P. L. A., Cherubin, M. R., Gomes, T. C. A., Lisboa, I. P., Satiro, L. S., Cerri, C. E. P., & Siqueira-Neto, M. (2020). Straw removal effects on sugarcane root system and stalk yield. Agronomy, 10, 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10071048

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10071048 -

Moraes, L. A. S. de, Tavares Filho, J., & Melo, T. R. de. (2022). Different managements in conventional sugarcane reform in sandy soils: Effects on physical properties and soil organic carbon. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 46, e0220017. https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20220017

» https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20220017 -

Moraes, M. T., Debiase, H., Franchini, J. C., Silva, V. R. (2013). Soil penetration resistance in a Rhodic Eutrudox affected by machinery traffic and soil water content. Engenharia Agrícola, 33, 748–757. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-69162013000400014

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-69162013000400014 -

Pacheco, L. P., São Miguel, A. S. D. C., Bonfim-Silva, E. M., Souza, E. D., & Silva, F. D. (2015). Influência da densidade do solo em atributos da parte aérea e sistema radicular de crotalária. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, 45(4), 464 - 472. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632015v4538107

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632015v4538107 -

Rabot, E., Wiesmeier, M., Schlüter, S., & Vogel, H.-J. (2018). Soil structure as an indicator of soil functions: A review. Geoderma, 314, 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.11.009

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.11.009 -

Reynolds, W. D., Drury, C. F., Tan, C. S., Fox, C. A., & Yang, X. M. (2009). Use of indicators and pore volume-function characteristics to quantify soil physical quality. Geoderma, 152, 252-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.06.009

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.06.009 -

Sá, M. A. C., Santos Junior, J. D. G., Franz, C. A. B., Rein, T. A. (2016). Qualidade física do solo e produtividade da cana-de-açúcar com uso da escarificação entre linhas de plantio. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, 51(9), 1610–1622. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-204x2016000900061

» https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-204x2016000900061 -

Santos, A. K. B., Popin, G. V., Gmash, M. R., Cherubin, M. R., Siqueira Neto, M., Cerri, C. E. P. (2022). Changes in soil temperature and moisture due to sugarcane straw removal in central-southern Brazil. Scientia Agricola, 79(6), e20200309. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-992X-2020-0309

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-992X-2020-0309 - Santos, H. G. dos, Jacomine, P. K. T., Anjos, L. H. C. dos, Oliveira, V. A. de, Lumbreras, J. F., Coelho, M. R., Almeida, J. A. de, Araujo Filho, J. C. de, Oliveira, J. B. de, &Cunha, T. J. F. (2018). Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos (5ª ed., rev. e ampl.). Embrapa.

- Silva Junior, C. A., Carvalho, L. A., Centurion, J. F., Oliveira, E. C. A. (2013). Comportamento da cana-de-açúcar em duas safras e atributos físicos do solo, sob diferentes tipos de preparo. Bioscience Journal, 29(1), 1489–1500.

-

Souza, G. S., Souza, Z. M., Cooper, M., Tormena, C. A. (2015). Controlled traffic and soil physical quality of an Oxisol under sugarcane cultivation. Scientia Agricola, 72(3), 270 - 277. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0078

» https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0078 -

Tavares Filho, J., Barbosa, G. M. C., Ribon, A. A. (2010). Physical properties of dystrophic red Latosol (Oxisol) under different agricultural uses. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 34, 925–933. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832010000300034

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832010000300034 - Teixeira, P. C., Donagemma, G. K., Fontana, A., Teixeira, W. G. (2017). Manual de métodos de análise de solo (3ª ed.). Embrapa.

-

Valadão, F. C. A., Weber, O. L., Valadão Júnior, D. D., Scarpinelli, A., Deina, F. R., Bianchini, A. (2015). Adubação fosfatada e compactação do solo: Sistema radicular da soja e do milho e atributos físicos do solo. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 39(1), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1590/01000683rbcs20150144

» https://doi.org/10.1590/01000683rbcs20150144 -

Valim, W. C., Panachuki, E., Pavei, D. S., & Sobrinho, T. A., & Almeida, W. S. (2016). Effect of sugarcane waste in the control of interrill erosion. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, 37, 1155–1164. https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n3p1155

» https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n3p1155 -

Viana, J. L., Souza, J. L. M., Auler, A. C., Oliveira, R. A., Araújo, R. M., Hoshide, A. K., Abreu, D. C., Silva, W. M. (2023). Water dynamics and hydraulic functions in sandy soils: Limitations to sugarcane cultivation in Southern Brazil. Sustainability, 15, 7456. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097456

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097456

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

Edna Maria Bonfim-Silva

-

Edited by

SBEA

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

04 Aug 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

28 Oct 2024 -

Accepted

9 June 2025

PHYSICAL SOIL QUALITY UNDER MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS IN SUGARCANE FIELD RENEWAL

PHYSICAL SOIL QUALITY UNDER MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS IN SUGARCANE FIELD RENEWAL

Source: CEMTEC.

Source: CEMTEC.