ABSTRACT

During blueberry picking operations, changes in the blueberry harvester’s body posture (BHBP) caused by undulating farmland surfaces significantly affect the operational stability of the harvesting device. To mitigate these effects, an active suspension (AS) control system was developed. First, considering the coherence and time lag of the four-wheel tracks, the filtered white noise method was chosen to generate road excitations. Subsequently, the virtual prototype model of the blueberry harvester (BH) was built in ADAMS with the nonlinear properties of the passive suspension. A fuzzy proportion integral differential (PID) control algorithm and decoupled control strategy were employed to design the AS control system. Finally, ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulations and field tests were conducted. The results indicate that the measured farmland road profile conforms to standard D-level road excitations according to ISO8608, and the co-simulation model accurately predicts the BH’s dynamic response. Under AS control, the vertical acceleration, pitch acceleration, and roll acceleration of the BH decreased by 38.52%, 37.39%, and 34.29%, respectively, during simulations compared to the passive suspension. In field tests, these reductions were 36.51%, 33.84%, and 30.21%, respectively. The AS control system proposed in this study significantly improves the stability of the BH under farmland road excitation, effectively mitigating equipment impacts and wear caused by machine jolts while enhancing harvesting performance. This research addresses the gap in applying AS technology within the field of harvesting machinery, offering a novel technical approach for the development of vehicle control systems for harvesting machinery targeting blueberries and other shrub crops. It holds considerable theoretical value and practical significance.

blueberry harvester; farmland road profile; control system; co-simulation; field test

INTRODUCTION

Blueberries are known for their high nutritional and medicinal value and are called the “King of Berries.” In China, manual blueberry harvesting consumes a large amount of labor, materials, and money every year. This increases planting costs and reduces farmers’ income. It is urgent to replace manual harvesting with machines to improve efficiency and reduce costs. In recent years, modern agricultural machinery has helped improve production efficiency and work quality. Blueberries, as high-value crops, require efficient harvesting and high fruit quality. The stability of the harvester is crucial, especially under complex field conditions. Most traditional blueberry harvesters (BHs) use passive suspension systems. These systems cannot reduce vibrations on uneven farmland effectively. This affects harvesting performance and the long-term stability of the equipment. To improve harvesting performance, this study uses a white noise method to create a farmland road excitation. Further, a fuzzy proportion integral differential (PID) control method is used to design an active suspension (AS) control system. This system reduces the impact of jolts on the harvesting mechanism and improves the quality of picked fruit.

Many scholars have conducted extensive research on road excitation generation. Extensive experiments have revealed that common farmland road roughness conforms to ISO8608 standards and is categorized as levels C, D, and E (Xu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Among the various simulation algorithms, the filtered white noise method stands out for its high simulation accuracy and fast computational speed. Yin et al. (2017) and Zhao & Lu (1999) successfully utilized the filtered white noise method to establish road surface models of various levels for vehicle dynamics simulations. Bogsjö (2008) and Zhang & Zhang (2006) introduced coherence and lag theories for time-domain road surface models and applied these theories to the filtered white noise algorithm, resulting in the development of multi-wheel road surface excitations consistent with the ISO8608 standards.

In the field of vehicle body posture control, experts and scholars have conducted in-depth research on this subject. Some scholars have utilized linear quadratic regulator (LQR) control theory to design AS controllers and establish AS control systems for full vehicle models. Lu et al. (2023) proposed an adaptive roof-LQR coordinated control system to reduce vibration in commercial vehicle cabins and enhance ride comfort. Rodriguez-Guevara et al. (2022) developed an MPC-LQR controller to improve the comfort and road-holding of vehicles manipulated using electro-hydraulic actuators. Han et al. (2022) investigated vehicle performance and proposed a fuzzy PID control strategy to meet the different performance requirements of AS under different road conditions. Abut & Salkim (2023) designed a fuzzy-LQR controller for a 2-degrees-of-freedom (DOF) quarter-vehicle model, and they showed that this algorithm exhibited better stability compared to traditional LQR controllers. Additionally, other scholars have employed various control theories to enhance vehicle performance. Pan & Xu (2022) used the ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulation method to analyze the safety and control performance of a magnetic levitation control system. Ma et al. (2023) applied fuzzy control theory to a 7-DOF vehicle suspension model and conducted co-simulation tests under random road conditions. Meng et al. (2021) employed the homogeneous domination method to construct an active suspension homogeneous controller (ASHC), effectively ensuring the state stability of the AS system. Félix-Herrán et al. (2019) obtained the optimal feedback gain matrix by solving linear matrix inequalities (LMIs) and designed a robust H∞ controller for a half-vehicle model with AS. Konieczny et al. (2020) introduced nonlinear characteristics into a 4-DOF control object and demonstrated the control performance of sliding mode controllers through numerical simulation.

With the development of simulation software, it has become clear that the mathematical models of suspension systems with 2, 4, and 7 DOF are incapable of satisfying the requirements for accuracy. Therefore, scholars have focused on improving the modeling accuracy of research objects, providing a specific engineering background for the application of suspension control theory. Yang et al. (2022) proposed a road surface excitation preview control algorithm based on laser radar recognition technology for passenger vehicles, enhancing vehicle stability. However, its limitation is that it identifies targets as local obstacles on hard roads, which does not match the situation of agricultural field surfaces. Ni et al. (2022) designed a posture control system for wheel-legged robots on uneven terrain, but its modeling of the road profile is too simplified. Liu et al. (2022) established a semi-active suspension incremental PID control system for agricultural tractors with smooth operation as the optimization goal. Shao et al. (2019) developed a dual-hydraulic-cylinder rear suspension system based on fuzzy PID, achieving automatic lateral posture adjustment for mountain tractors.

Additionally, Najafi et al. (2022) proposed a multi-dimensional fuzzy sliding mode controller (MD-FSMC) for active variable geometry suspension systems. The primary advantages of this controller include effectively reducing the roll and pitch angle accelerations of the vehicle, enhancing lateral stability, preventing rollovers, and minimizing body bounce acceleration and tire deformation. Damavandi et al. (2022) investigated 180 possible hydraulic interconnected suspension configurations and optimized 24 potential configurations. They used a 14-DOF vehicle model to simulate and evaluate the handling and comfort performance under different configurations. After optimization, six hydraulic parameters were adjusted using a genetic algorithm to improve vehicle handling and comfort. Masih-Tehrani & Ebrahimi-Nejad (2018) introduced a hybrid optimization method that combines genetic algorithms (GAs) with integer linear programming (ILP) to manage fuel consumption and emission control in tracked bulldozers. By replacing the traditional five-speed transmission system with a continuously variable transmission (CVT), the method better utilized the engine’s high-efficiency zones, significantly improving fuel consumption and emission levels. Gheibollahi & Masih-Tehrani (2023) optimized the seat suspension system of trucks using fuzzy logic control (FLC) to enhance ride comfort while considering controller energy consumption. A 13-DOF truck model and the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) were used to solve a multi-objective optimization problem aiming to balance seat acceleration and controller torque. Gheibollahi et al. (2024) explored the application of GA-PID and fuzzy PID controllers in truck seat suspension systems and evaluated the impact of different controllers on ride comfort under various road conditions. The study demonstrated that optimizing seat suspension control effectively improves the comfort of truck drivers and passengers during prolonged driving sessions.

The aforementioned studies have made significant progress in suspension control and vehicle dynamics optimization but still present certain technical gaps. First, many studies rely on simplified experimental conditions or specific platforms, lacking sufficient consideration of the application scenarios for BHs in complex farmland environments. Additionally, the suspension systems of BHs primarily adopt passive suspension designs, which depend on fixed stiffness and damping parameters. These systems are unable to adapt to changing road conditions, leading to severe vehicle vibrations when the vehicle is operating on rough terrain, thereby affecting the efficiency and stability of picking operations. Based on this, this study proposes an AS control system for a BH. First, a time-domain road excitation model for the four-wheel system is generated using the filtered white noise method, and its simulation accuracy is validated through field tests of farmland road profiles. Second, a simulation model of the BH is developed based on the prototype’s structural dimensions and the empirical parameters of the nonlinear suspension, with adjustments being made according to field test results. Third, an AS control system is designed using a fuzzy PID algorithm, integrated with a decoupling control strategy for force conversion. Finally, the road excitation model, the BH model, and the AS control system are coupled through ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulation. The control performance is analyzed based on the simulation and field test results.

The study of the dynamics of BHs plays a crucial role in the development of agricultural mechanization and modernization. Through theoretical research, precise dynamic models of machines can be established to deeply analyze their operational and harvesting performance, providing a solid theoretical foundation for machine design. Dynamic co-simulation is an efficient approach that employs interactive simulations to comprehensively evaluate harvesting performance. This process significantly reduces costs associated with experiments and practical development and shortens the machine development cycle. Compared with previous studies, this research conducted field tests of road excitations on uneven farmland surfaces, ensuring that the disturbance signals in the control system better reflect actual working conditions. To meet the stability requirements of the BH, the fuzzy PID algorithm was applied to the AS control system. The nonlinear characteristics of the machine were also considered to enhance operational reliability and stability, filling a gap in the application of AS technology in the field of BH machinery. In terms of control effect validation, instead of relying solely on simulation, this study combined ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulation with field tests to perform a comparative analysis of the machine’s performance under farmland conditions. The feasibility and applicability of the control system were confirmed, offering new insights and technological approaches for the intelligent and efficient development of the mechanical harvesting of blueberries and other berry crops.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Overview of the Research

The research process of this study is illustrated in Figure 1. The filtered white noise method was used to generate road signals and reconstruct the four-wheel road excitation model in the time domain. Field tests were conducted to verify whether the model aligns with the elevation characteristics of farmland roads from both time-domain and frequency-domain perspectives. A virtual prototype of the BH was developed for dynamic theoretical analysis based on the prototype’s structural dimensions and the empirical parameters of the nonlinear suspension. Simulation model parameters were adjusted according to the results of field tests. A fuzzy PID control system was established with the blueberry harvester’s body posture (BHBP) as the control objective. Meanwhile, ADAMS and MATLAB co-simulation was employed to analyze the accuracy of road excitation modeling, harvester modeling, and control performance.

This study establishes a connection among theoretical research, simulation, and field tests. The accuracy of the simulation model for the AS control system of the BH was validated through field tests of the farmland road profile and the BHBP. This enhances the practical applicability of the research findings. Not only does it confirm the effectiveness of the technology, but also it provides theoretical support for future control system designs of BHs. The AS control system proposed in this study can adapt to complex field road conditions, improving the stability of the BHBP and demonstrating potential for practical application. As agricultural mechanization progresses, the increasing complexity of field operation environments has raised the requirements for harvester stability and adaptability. The AS control system proposed in this study can adapt to complex field road conditions, improving the stability of the BHBP. It demonstrates practical application potential and offers significant advantages in enhancing harvesting efficiency and reducing equipment wear, meeting the demands of agricultural mechanization. However, this technology still faces certain limitations. The filtered white noise method was used to obtain farmland road excitations in this study. In actual farmland environments, road excitations may exhibit more complex non-Gaussian characteristics or localized variations (e.g., potholes, weeds, slippery surfaces), which the filtered white noise method cannot fully capture. Furthermore, the control system in the simulation assumes ideal conditions. In field testing, control signals may have time delays, and actuators may be affected by interference or environmental changes, which could result in suboptimal control performance.

Modeling of the Farmland Road Surface Excitations

Based on the international standard ISO8608, the road surface power spectral density Gq(n) can be expressed as follows:

Where:

Gq(no) is the road surface unevenness coefficient (m3);

n is the spatial frequency (m-1);

n0 is the reference spatial frequency (m-1), taken as 0.1 m-1;

U is the frequency exponent, which reflects the average vibration characteristics under various typical road conditions, such as urban, rural, and agricultural road conditions, allowing the road model to capture the impact of common road irregularities on vehicle vibrations. To provide more representative and realistic road conditions, this study sets U to 2 (Zhao & Lu, 1999; Zhang & Zhang, 2006).

Considering that the farmland roads in blueberry plantations are naturally distributed with random undulations and no human interference, the working principle of the BH, and the planting distribution of blueberry plants, it is known that the harvester operates in a straight line while riding on the ridges during blueberry mechanical harvesting. To study the BH’s driving performance during blueberry harvesting operations, this study does not consider the tire side slip characteristics during the BH’s steering process and uses the filtered white noise method to generate the single-wheel road excitation in the time domain. According to the basic principles of the algorithm, the road surface elevation is defined as a white noise random signal that satisfies specific relationships, expressed as

Where:

zg(t) is the time-domain road excitation (m);

is the derivative of the time-domain road excitation with respect to time (m/s);

n1 is the spatial cut-off frequency, taken as 0.01 m-1 (Zhao et al., 1999; Yin et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2018);

ν is the vehicle speed (m/s);

ν(t) is the white noise signal.

According to ISO8608, the white noise signal Ω(t) is set to have a mean of 0 and a power spectral density of 0.5. The simulation step size is set to (10ν)-1, consistent with the reference spatial frequency n0 = 0.1 m-1.

During the actual operation of the BH on farmland, there are time lag and coherence relationships between the excitations of the front-rear wheels and those of the left-right wheels.

The time lag relationship of the road excitations experienced by the front and rear wheels of the BH can be expressed as follows:

Where:

are the road excitations of the rear wheels (m);

are the road excitations of the front wheels (m);

td is the lag time (s), taken as ;

L is the wheelbase (m).

The statistical properties of the power spectral density for the four-wheel excitations of the harvester are the same (Zhao et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2018). Based on the theory of random vibration, the spatial coherence function of the left and right wheels of the harvester is obtained as follows:

Where:

s12(w) is the spectral density function of the left and right wheels of the harvester;

s1(w) is the auto-spectral density function;

H12(w) is the system frequency response function;

w is the angular frequency.

The transfer function for left and right wheel road excitation is obtained using the second-order Pade algorithm:

Where:

are the road surface excitations of the right wheels (m);

are the road surface excitations of the left wheels (m);

c is the distance between the left and right wheels (m).

The inverse Laplace transform of [eq. (5)] is performed, and the result is combined with [eq. (2)]; the relationship between the road excitations of the left and right wheels can be expressed as follows:

By defining the state variables x(t), [eq. (6)] is expressed in the state-space form as follows:

The road excitation of the left-front wheel zglf is obtained using [eq. (2)]. It is then transformed into the road excitation of the left-rear wheel zglr using [eq. (3)]. Finally, it is further transformed into the road excitation of the right-front wheel zgrf using [eq. (7)].

Modeling and Analysis of the BH

Modeling of the Passive Suspension for the BH

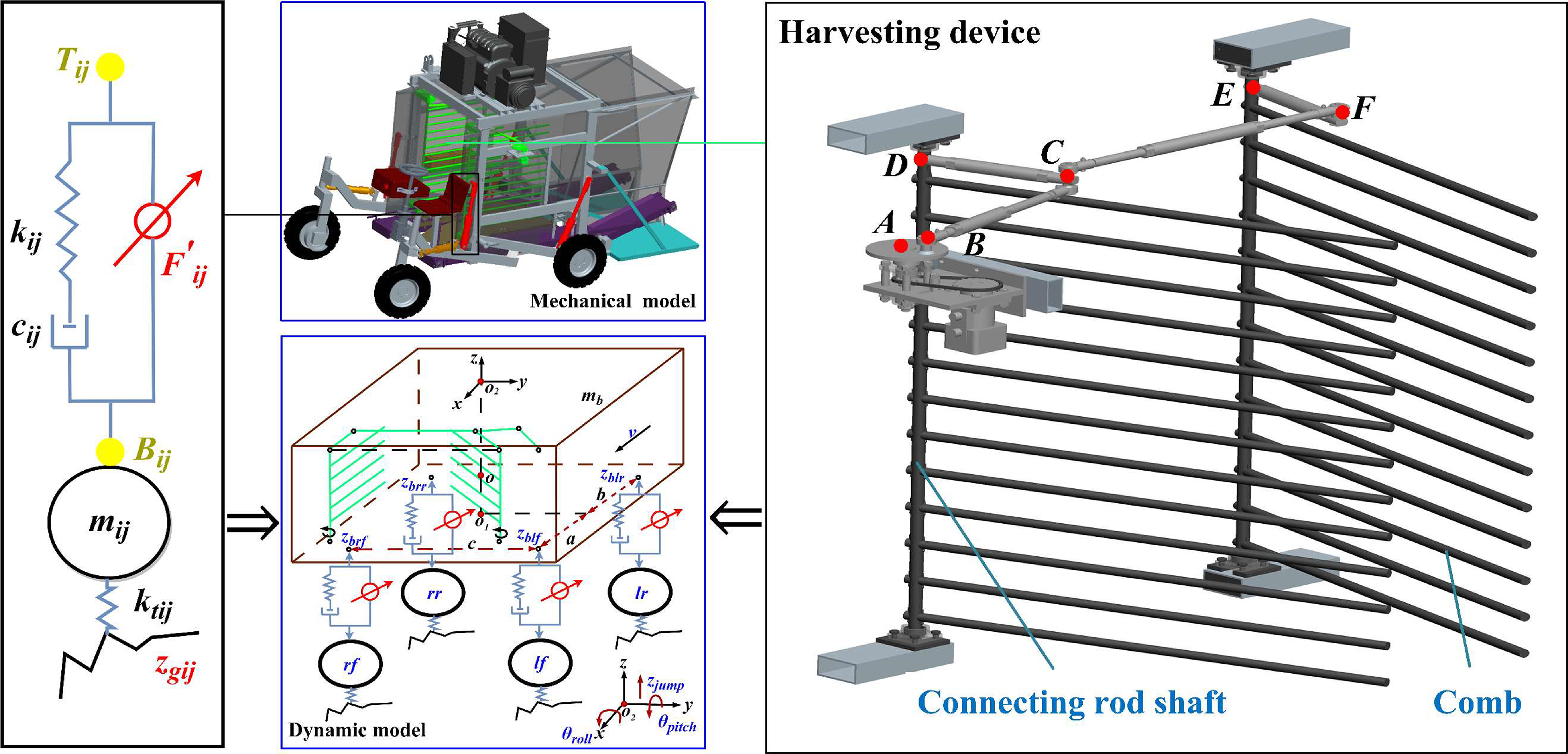

The structure and work principle of the BH is shown in Figure 2; it comprises an end plate, four hydraulic suspensions, a fruit gathering device, two steering devices, four running devices, a harvesting device, a motor, a hydraulic control system, a gantry frame, a shield, and two conveyors.

The working principle and structure diagram of the BH. 1) End plate, 2) hydraulic suspension, 3) fruit gathering device, 4) steering device, 5) running device, 6) blueberry plants, 7) harvesting device, 8) motor, 9) hydraulic control system, 10) gantry frame, 11) shield, 12) conveyor

The harvesting device of the BH includes a drive-end motor, a crank double-rocker transmission mechanism, and combs (left and right) as the end components. During field operations, the BH moves at a constant speed towards the blueberry bushes, with the motor providing power to the harvesting device. After the blueberry plants enter the machine, the combs of the harvesting device perform a reciprocating lateral rotational motion, impacting the plants to induce excitation forces that dislodge the blueberries. The blueberries are then gathered by the fruit catching plate and transported via the conveyor, thereby completing the picking process.

Figure 2 depicts the hydraulic suspensions connected to the BH’s body via bushings, which are modeled using four sets of spring-damping mechanical models. Specifically, the nonlinear spring-damping mechanical model is formulated as follows:

Where:

kij(i = l, r; j-f,r) represents the suspension stiffness (N/m);

ε is the stiffness nonlinear factor;

Δxij represents the relative displacement between the upper and lower hinge points of the suspension (m);

represents the relative velocity between the upper and lower hinge points of the suspension (m/s);

Fij represents the nonlinear passive suspension force (N);

csd and csu are the suspension damping coefficients during extension (Δχ > 0) and compression (Δχ ≤ 0), respectively (N‧s/m);

nds and nsu are the suspension damping exponents during extension (Δχ > 0) and compression (Δχ ≤ 0), and they are given by empirical parameters, with nsd = 0.8140 and nsu = 0.6879 (Shao et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022).

Modeling of the AS for the BH

Based on the mechanical structure and working principle of the BH, the dynamic model that accommodates the suspension’s nonlinear characteristics is shown in Figure 3.

Dynamic analysis of the BH (dynamics model of the nonlinear suspension, dynamics model of the whole machine and harvesting device)

As shown in Figure 3, 0 represents the harvester’s center of mass, 01 represents the projection point of 0 on the bottom of the BH’s body, and the suspension and BH body hinge positions are denoted as .

The crank double-rocker mechanism () is a transmission chain. It features a crank rotating around point A, inducing the simultaneous movement of the rockers. Consequently, the left and right connecting shafts rotate correspondingly, driving the lateral oscillations of the combs.

Due to the small pitch and roll angles for the BHBP during the blueberry picking process, the linearization assumption is made: sin θ ≈ θ. The vertical displacements at the four contact points Tij between the BH’s body and the suspension can be expressed as follows:

Where:

represents the vertical displacements at the contact points between the vehicle body and suspensions (m);

zjump is the vertical displacement of the vehicle’s center of mass (m);

θpitch and θroll are the pitch and roll angles of the vehicle body (°);

a,b are the front wheelbase and the rear wheelbase (m), respectively;

c is the wheelbase (m), where .

The mechanical movements of the BH’s body include vertical motion, pitch motion, and roll motion, as well as the vertical motion of the four wheels. The motion of the BH’s body can be expressed as follows:

Where:

is the vertical acceleration of the BH’s center of mass (m/s2);

are the pitch angular acceleration and roll angular acceleration of the BH’s center of mass (°/s2);

represents the AS control force (N), solved by the AS control system;

Ip, Ir are the pitch inertia and roll inertia of the vehicle body (kg‧m2), respectively.

By introducing road excitation zgij(t) into the model, the wheel motion can be expressed as

Where:

represents the vertical acceleration of the four wheels (m/s2);

mij represents the mass of the four wheels (kg);

ktij represents the stiffness of the four wheels (N/m);

zij represents the vertical displacements of the four wheels (m).

Modeling of AS Control System for the BH

Currently, the suspension system of BHs mainly uses a passive suspension design, which relies on fixed stiffness and damping parameters. This system cannot adapt to changes in road conditions, resulting in changes in the BHBP when operating on complex roads, which affects the efficiency and stability of the harvesting operation.

The control block diagram of the AS control system for the BH is illustrated in Figure 4. The four-wheel road excitations zgij are generated by the filtered white noise method: . The vertical acceleration , pitch angular acceleration , and roll angular acceleration are selected as evaluation indicators of the BHBP and the control objectives. Therefore, Sd(t) represents the input signal of the AS control system: . Sr(t) represent the feedback output signal of the BH: . The derivatives of the deviation e'(t) are the input signals for the fuzzy PID controllers; it can be expressed as . The output signals of the BHBP control system are the AS control force , solved by decoupling the posture control force . The actual output force of the hydraulic suspension device is .

The working principle of the AS control system is as follows: Road excitations zgij are transmitted through the BH’s tires to the body, causing vertical movement , pitch movement , and roll movement . The difference e'(t) between the preset ideal signals Sd(t) and the actual signals Sr(t) are used as the control signal input to the fuzzy PID controller. The output signals Fposture of the fuzzy PID controller are converted into the AS control force F'ij by decoupled analysis. The results are transmitted to the BH by the hydraulic suspensions. The closed-loop feedback control loop is established to suppress BHBP changes, thereby enhancing the stability of blueberry picking operations.

The BHBP control subsystem consists of three sets of fuzzy PID controllers (Fuzzy PID-Ⅰ, Fuzzy PID-Ⅱ, Fuzzy PID-Ⅲ), which control the jump motion, pitch motion, and roll motion of the BH’s body, respectively. Therefore, the PID controller parameters can be expressed as follows:

Where:

ΔK{p,i,d} represents the correction parameters of PID controllers determined through fuzzy inference, where ;

K'{p,i,d} represents the initial parameters of PID controllers, where , which is detailed later;

K{p,i,d} represents the dynamic adaptive parameters of PID controllers, where .

The decoupled conversion relationship between the posture control force Fposture and the AS control force F'ij is modeled by S-Function in MATLAB/Simulink, and it can be expressed in the following matrix form:

Where:

Fjump, Fpitch, and Froll are the jump, pitch, and roll motion control forces of the BH (N), respectively.

Configuration of the MATLAB-ADAMS Co-simulation Model

The MATLAB-ADAMS coupled simulation model of the AS control system for the BH is shown in Figure 5. This model consists of a road excitation subsystem, the ADAMS model of the BH, and a fuzzy PID and decoupled conversion control subsystem. In the road excitation subsystem, the road roughness coefficient Gq(n0) and driving speed ν are adjusted. In the fuzzy PID and decoupled conversion control subsystem, the operation mode of the BH’s passive/active suspension is configured. The simulation process utilizes the fixed-step solver (ode8) for mathematical computation. The road excitation subsystem generates the farmland road surface excitation Zgij, and the dynamic response of the BH under road disturbances is transferred to the control subsystem. After calculation, the suspension control force F is obtained.

MATLAB-ADAMS co-simulation model (dynamic model of the BH, ADAMS model of the BH, motion constraint relationships for each component (topology diagram), co-simulation model in MATLAB/Simulink)

The simulation parameters of the model are derived: 1. structural dimensions of the BH, and 2. empirical parameters given in Liu et al. (2013) and Zhao et al. (2001) with field test corrections, which are detailed later.

The input domains for the deviation e(t) are , and , and the input domains for the derivative of the deviation e'(t) are , , and . The output domain for the control force is . The same fuzzy subsets are used: {NB, NM, NS, O, PS, PM, PB}.

When the root-mean-square (RMS) values of the vertical acceleration , the pitch angular acceleration , and the roll angular acceleration reach their minimum values during the simulation, the initial parameters 𝐾'{p,i,d} of the fuzzy PID controllers are determined; they are given in Table 1.

By combining the fuzzy rules (Li et al., 2014; Bharali et al., 2016; Shao et al., 2019) with the system responses during the simulation, it is determined that the same fuzzy rule table is employed for the three fuzzy PID controllers. The fuzzy set correspondence between fuzzy controller inputs [e(t), e'(t)] and outputs [ΔKp, ΔKi, ΔKd] is listed in Table 2. The fuzzy and defuzzification processes are conducted using triangular membership functions and the centroid method, respectively.

Field Test

Field Test of the Farmland Road Profile

The elevation of the farmland road surface was measured to validate the simulation accuracy of the four-wheel road excitation based on the filtered white noise method in this paper.

The measuring device mainly consists of an HG-C1400-P laser displacement sensor and a YB-A604 data acquisition card. The laser displacement sensor is securely mounted on the test vehicle using a clamp with a magnetic base and is zeroed by adjusting the clamp’s joint angle to ensure that the road elevation changes remain within the

sensor’s detection range. The raw test data are transmitted to the host computer via the data acquisition card (sampling frequency: 800 Hz). During data collection, the test vehicle maintained a constant speed. The test was conducted in September 2023 at the following location: 47°1′38″N, 126°59′3″E.

Field Test of the BHBP

To correct the simulation parameters of the BH model in ADAMS and analyze the control effect of the active suspension, the BHBP measurement system was designed and field tests were conducted, as shown in Figure 6.

The same field used for the road profile field test was selected to eliminate the influence of road conditions on the test results. A YK-YD5000T posture sensor was installed on the BH cabin to measure BHBP signals during driving. The SA1600 data acquisition device (sampling frequency: 600 Hz) was used to transmit the real-time signals () measured by the sensor to the host computer for data processing and control.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Comparative Analysis of Passive Suspension Simulation/Test Results

The original road elevation data were obtained from the road profile field test. Due to vehicle vibrations during travel and installation deviations (horizontal and angular positions) of the sensor, MATLAB was utilized to eliminate outliers, noise, mean values, and trend terms and to resample the original data to match the volume of simulation data at the specified simulation step size (10ν)-1.

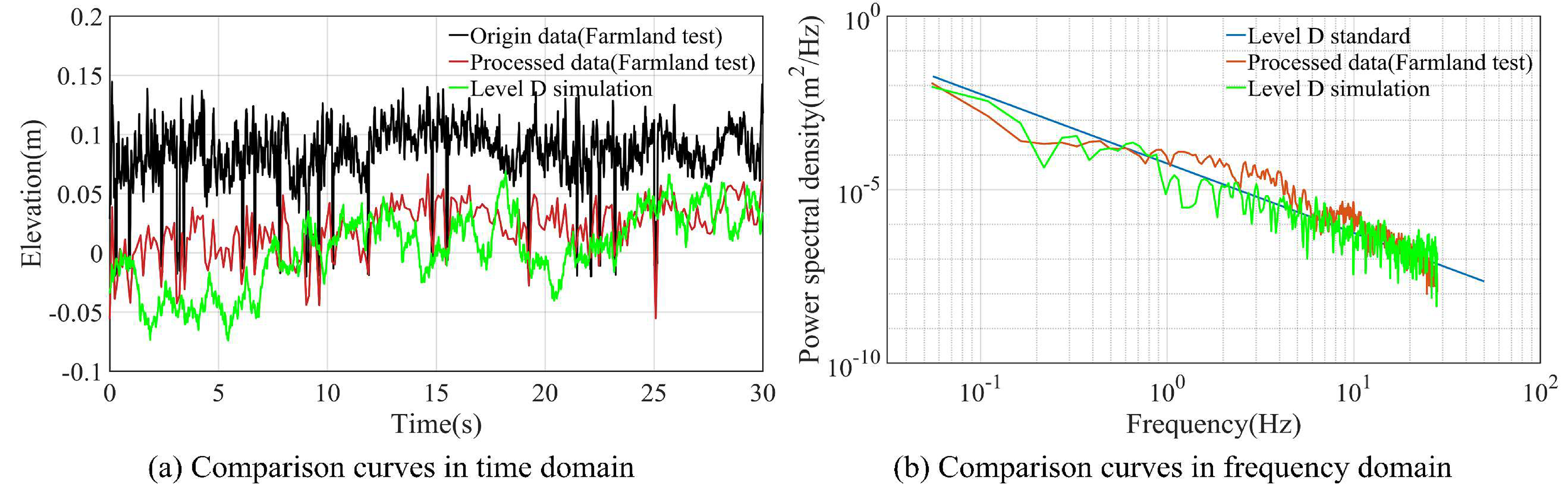

Both the simulation speed and the test speed ν were 1.5 m/s. The original data, the processed data, and the D-level road excitation are shown in Figure 7(a). The displacement power spectral density of the standard D-level road, simulated D-level road, and processed data from the farmland test is shown in Figure 7(b).

Figure 7(a) indicates that the fluctuation intervals in the time domain of the D-level road in the simulation and test data are basically the same. Figure 7(b) shows the consistency in the power spectral density among the standard, simulation, and test in the frequency domain. Therefore, the D-level road excitations can be used to model farmland road conditions for the dynamic simulation of the BH.

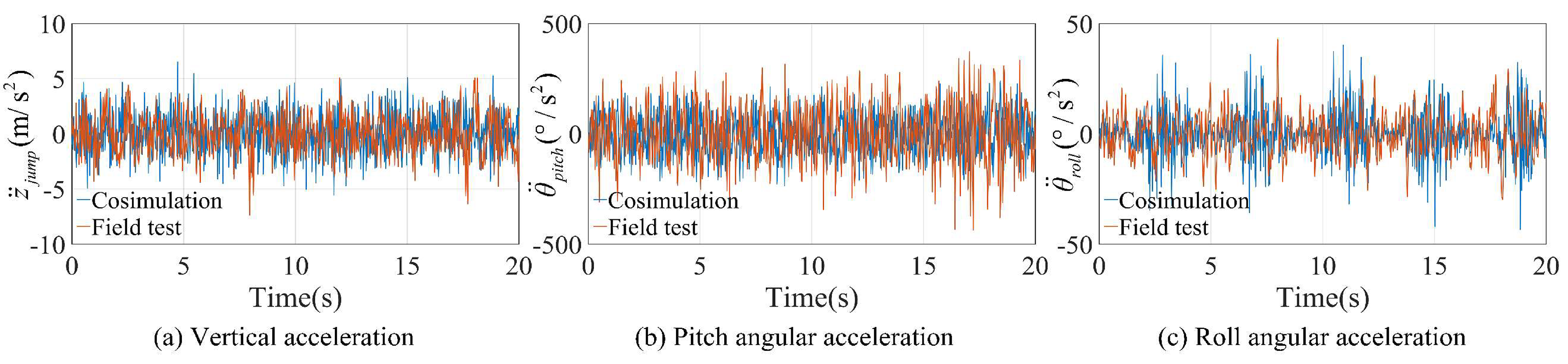

The posture data of the harvester during farmland road travel were obtained through the field test. The empirical parameters (Zhao et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2013) were used as preset values for the ADAMS model of the BH, and the simulated road surface was set to level D. Parameter adjustments were made to achieve optimal comparison results between the test and simulation, as shown in Figure 8.

The differences in the data shown in Figure 8 are due to the fact that road roughness levels are classified by ISO8608 based on the power spectral density in the frequency domain, leading to differences in the elevation distribution in the time domain for road surfaces of the same level. Therefore, using D-level road surface excitation to simulate farmland surface conditions ensures simulation accuracy to a limited extent.

Table 3 lists the simulation parameters of the BH corresponding to the results shown in Figure 8. Under the parameters in Table 3, the test data and simulated results of the BHBP show a similar range of variation, indicating that the ADAMS model of the BH is able to predict the dynamic response of the machine during blueberry picking and provide support for the design of the AS control system.

Comparative Analysis of Active/Passive Suspension Simulation Results

The traveling speed ν of the BH was set to 1.5 m/s for the MATLAB-ADAMS joint simulation of different road roughness levels. Since the farmland road profile is in class D, in order to analyze the control effect of the AS system in a wider range, the road roughness level is set to C, D, and E. The simulation results of each control object under passive, active, and ideal states (without road excitation) are shown in Figure 9.

Comparison of simulation results among passive, active and ideal states. (a) Vertical acceleration of the BH’s mass center, (b) pitch angular acceleration of the BH’s mass center, (c) roll angular acceleration of the BH’s mass center

Figure 9 indicates that as the road roughness level increases, the effect of road excitations on the dynamic response of the BH becomes more significant. Specifically, the variations in the vertical acceleration , and roll angular acceleration of the BH’s body are more pronounced. Under the influence of the AS control system, the BHBP is suppressed to varying degrees, making it closer to the ideal state (without road excitations). Consequently, the AS control system significantly improved the machine’s performance, meeting the design requirements.

Based on the simulation results in Figure 9, the RMS values of the BHBP and control effectiveness (%) under the three operating conditions for both passive and active suspensions are presented in Table 4.

Using the RMS of the passive suspension system as a baseline, the results in Table 4 show that the control effectiveness in the simulations varies across different road conditions. The highest control effectiveness values for the BHBP are 38.52%, 37.39%, and 34.29%, respectively, with the optimal performance observed under D-level road excitations. Across all road conditions, the AS control system consistently outperforms the passive suspension system.

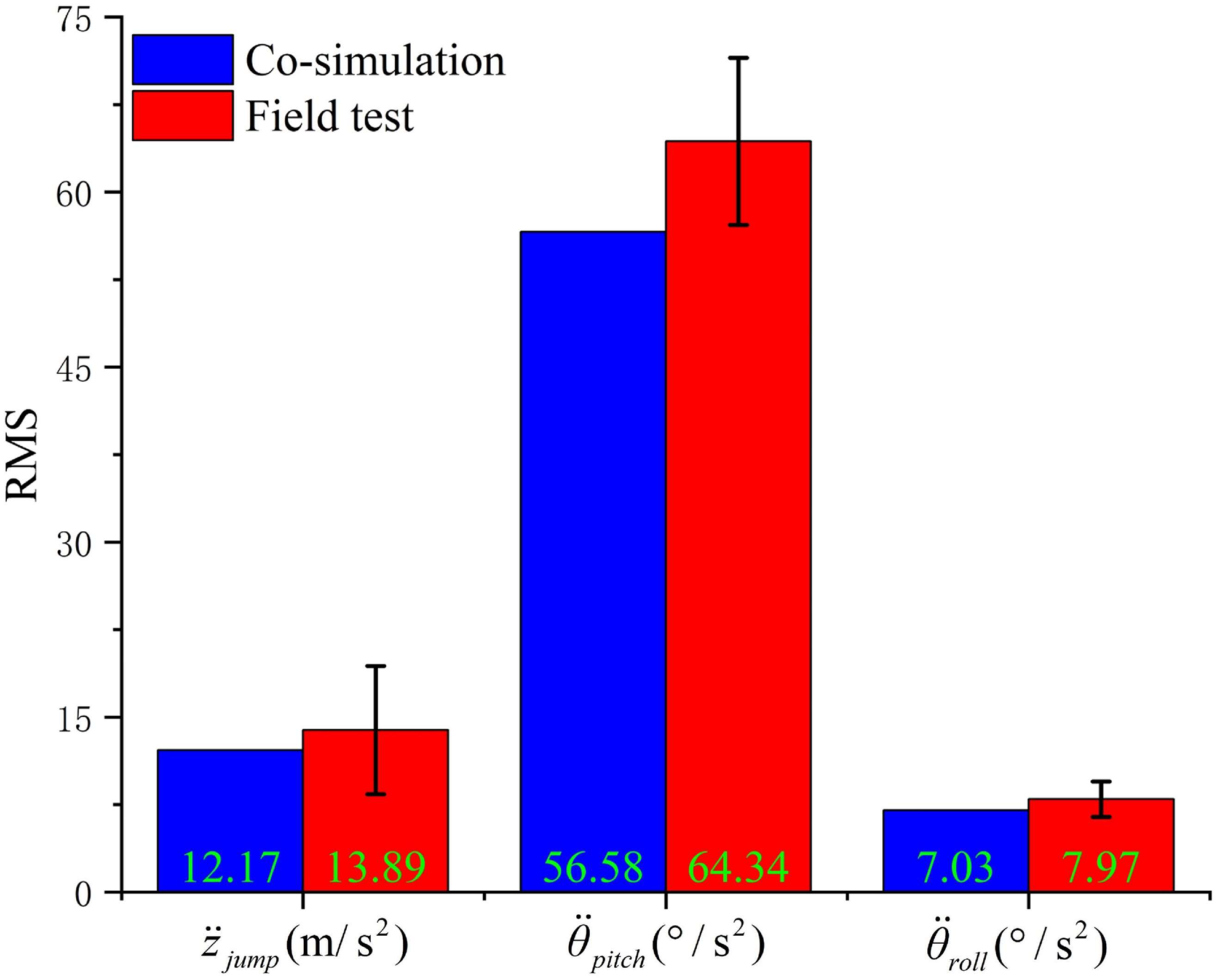

Comparative Analysis of Active/Passive Suspension Test Results

Based on the field test of the BHBP, the BH traveled over the farmland surface using both active and passive suspensions. The test was conducted five times, with the RMS values of the BHBP time-domain data recorded after each trial. The mean RMS (MRMS) values were then calculated from the five trials. The control effectiveness (%) is presented in Table 5.

Table 5 indicates that the AS control system significantly decreased changes in the BHBP during operation on farmland roads. The reductions in the vertical acceleration, pitch acceleration, and roll acceleration are 36.51%, 33.84%, and 30.21%, respectively. The research results show that the AS control system is able to significantly improve the dynamic response characteristics of the BH, effectively reducing pitch and roll motion caused by wheel-soil coupling. Overall, the AS has a significant control effect on the BHBP during harvesting operation, reducing wear and extending its service life.

Comparative Analysis of Active Suspension Simulation/Test Results

To further analyze the simulation accuracy of the co-simulation model in Figure 5, the results of five repeated tests on the BHBP under the AS control system are compared with the simulation results for D-level road excitations, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 shows that the MRMS values of the BHBP obtained from the field test of the AS control system are , consistent with the ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulation results. The corresponding fluctuation ranges of the BHBP are [10.98, 16.47], [61.58, 70.85], and [7.11, 8.71], indicating that the control effect is stable. It can be concluded that the fuzzy PID algorithm, combined with the decoupled analysis proposed in this paper, effectively improves the traveling stability of the BH on farmland.

Furthermore, the change in the BHBP during field tests is greater than that observed in the co-simulation data. The reasons for this discrepancy are the following: 1. The sliding friction, rolling friction, and non-ideal contacts between moving components in the suspension system cause deviations between the actual control force applied by the suspension actuator and the theoretical calculated values. 2. In actual field conditions, the main actuator of the machine control system—the hydraulic cylinder—has time delays due to the BH’s operating speed, causing the control force to lag behind the actual road surface, resulting in discrepancies between the test and simulation data. The corresponding specific improvement measures are the following: 1. Use materials with a low friction coefficient (such as PTFE composite materials and ceramic-coated steel) to design the moving components of the suspension and vehicle body, improve the machining accuracy of key moving parts, and optimize the internal structural gaps of the device. 2. Apply predictive control algorithms with feedforward compensation mechanisms to reduce the impact of time delays on the control system by predicting future control demands.

CONCLUSIONS

The AS control system designed in this study can significantly improve the dynamic performance of the BH under complex field road conditions, reducing the jump, pitch, and roll motion caused by wheel-soil coupling. By mitigating the BHBP under farm road spectra, the AS system effectively enhances the operational stability of the BH and the working performance of the fruit harvesting device. This has significant practical implications for improving the machine’s service life and blueberry harvesting efficiency. First, by improving the stability of the harvester and reducing fruit damage, the harvesting efficiency can be increased, thereby improving farmers’ economic benefits and promoting the sustainable development of agricultural machinery. Additionally, reducing the changes in the BHBP under non-ideal conditions helps decrease equipment wear and extends the BH’s service life. The technology based on the AS control system could be widely applied to harvesting equipment for other small berry crops, with considerable market potential.

-

According to the ISO8608 technical standard, the farmland road excitation is assumed to be a stationary white noise signal without human interference. The filtered white noise method was used to generate different levels of four-wheel road time-domain models, providing external excitation for the dynamic simulation of the BH, and the feasibility and accuracy of the model were analyzed through the field test of the farmland road profile.

-

The suspension system, walking mechanism, and picking mechanism were modeled as key structures using ADAMS software, along with nonlinear suspension empirical parameters. Motion constraints were added based on the working principle of the BH, and simulation model parameters were corrected based on the field test of the BHBP.

-

The AS control system for the BH was designed based on a fuzzy PID control algorithm, and a decoupling control strategy was used to solve control forces, implementing closed-loop feedback BHBP control for responding to the undulating farm road environment. The system’s control performance was analyzed through ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulation and field tests.

-

The field test and simulation results show that the AS control system significantly improved the dynamic performance of the BH. Under test conditions, the vertical acceleration, pitch angular acceleration, and roll angular acceleration of the vehicle body were reduced by 36.51%, 33.84%, and 30.21%, respectively, compared to the passive suspension. Under simulation conditions, these reductions were 38.52%, 37.39%, and 34.29%. During field tests, discrepancies were observed between the simulation results and experimental data; they are attributed to mechanical friction between moving components of the BH and time-delay feedback from the control system actuators.

Although the AS control system proposed in this study has achieved significant results in improving the stability of the BH, there are still issues that require further research and analysis. First, the limitation of the filtered white noise algorithm lies in its inability to simulate non-natural features of the road, such as bumps and depressions. Therefore, future studies should analyze the system in more realistic farm environments, particularly under extreme conditions such as slippery, high-traction, or rugged roads, to ensure that the research results have broad applicability. Second, the control system signal feedback delay and actuator output disturbances may be the causes of discrepancies between experimental and simulation results. This phenomenon could be common in the field of agricultural machinery motion control research, affecting the commercial application of suspension control algorithms in the modernization of agricultural machinery. In addition to its application in BHs, this control method can also be extended to other types of berry-harvesting machinery, such as strawberry and grape harvesters. The harvesting machines for different crops operate in distinct environments and have different requirements. Therefore, future research can adjust the control strategy according to the agronomic characteristics of different crops, further expanding the application scope of this technology and broadening the research field.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2572022DP01) and Manufacturing Technology Innovation Talent Project of Harbin (CXRC20231115883).

REFERENCES

-

Abut, T., Salkim, E. (2023). Control of quarter-car active suspension system based on optimized fuzzy linear quadratic regulator control method. Applied Sciences, 13(15), 8802. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13158802

» https://doi.org/10.3390/app13158802 -

Bogsjö, K. (2008). Coherence of road roughness in left and right wheel-path. Vehicle System Dynamics, 46(S1), 599-609. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423110802018289

» https://doi.org/10.1080/00423110802018289 -

Damavandi, A. D., Masih-Tehrani, M., Mashadi, B. (2022). Configuration development and optimization of hydraulically interconnected suspension for handling and ride enhancement. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering, 236(2 - 3), 381 - 394. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544070211018040

» https://doi.org/10.1177/09544070211018040 -

Félix-Herrán, L. C., Mehdi, D., Rodríguez-Ortiz, J. D., Benitez, V. H., Ramirez-Mendoza, R. A., & Soto, R. (2019). Disturbance rejection in a one-half semiactive vehicle suspension by means of a fuzzy-H8 controller. Shock and Vibration, 4532635. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4532635

» https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4532635 -

Gheibollahi, H., Masih-Tehrani, M. (2023). A multi-objective optimization method based on NSGA-II algorithm and entropy weighted TOPSIS for fuzzy active seat suspension of articulated truck semi-trailer. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 237(17), 3809 - 3826. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062231151799

» https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062231151799 -

Gheibollahi, H., Masih-Tehrani, M., Najafi, A. (2024). Improving ride comfort approach by fuzzy and genetic-based PID controller in active seat suspension. International Journal of Automation and Control, 18(2), 184-213. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAAC.2024.137072

» https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAAC.2024.137072 -

Han, S. Y., Dong, J. F., Zhou, J., Chen, Y. H. (2022). Adaptive fuzzy PID control strategy for vehicle active suspension based on road evaluation. Electronics, 11(6), 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11060921

» https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11060921 -

Konieczny, J., Sibielak, M., & Raczka, W. (2020). Active vehicle suspension with anti-roll system based on advanced sliding mode controller. Energies, 13(21), 5560. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13215560

» https://doi.org/10.3390/en13215560 -

Li, W. P., Liu, C., Zhang, L. X., Zhang, B. Z., Wang, Z. X. (2014). Application of fuzzy PID control in vehicle semi-active suspension system with magnetorhelogical damper. Mechanical Science and Technology for Aerospace Engineering, 33(12), 1902-1906. [In Chinese]. https://doi.org/10.13433/j.cnki.1003-8728.2014.1229

» https://doi.org/10.13433/j.cnki.1003-8728.2014.1229 -

Liu, G., Chen, S. Z., Wang, W. Z., Ma, T. (2013). Research on matching nonlinear damping to vehicle suspension. Machinery Design & Manufacture, (5), 113-116. [In Chinese]. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-3997.2013.05.034

» https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-3997.2013.05.034 -

Liu, G. H., Hao, C. Y., Li, M. Z., Sun, H. (2022). Attitude control simulation of mountain tractor based on semi-active suspension. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 53(S2), 338-348. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2022.S2.039

» https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2022.S2.039 -

Lu, Y., Khajepour, A., Soltani, A., Li, R., Zhen, R., Liu, Y., & Wang, M. (2023). Gain-adaptive Skyhook-LQR: A coordinated controller for improving truck cabin dynamics. Control Engineering Practice, 130, 105365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2022.105365

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2022.105365 -

Ma, S., Li, Y., Tong, S. (2023). Research on control strategy of seven-DOF vehicle active suspension system based on co-simulation. Measurement and Control, 56(7-8), 1251-1260. https://doi.org/10.1177/00202940231154954

» https://doi.org/10.1177/00202940231154954 -

Masih-Tehrani, M., Ebrahimi-Nejad, S. (2018). Hybrid genetic algorithm and linear programming for bulldozer emissions and fuel-consumption management using continuously variable transmission. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 144(7), 04018053. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001490

» https://doi.org/10.1061/ -

Meng, Q., Chen, C. C., Wang, P., Sun, Z. Y., Li. B. (2021). Study on vehicle active suspension system control method based on homogeneous domination approach. Asian Journal of Control, 23(1), 561-571. https://doi.org/10.1002/asjc.2242

» https://doi.org/10.1002/asjc.2242 -

Najafi, A., Masih-Tehrani, M., Emami, A., & Esfahanian, M. (2022). A modern multidimensional fuzzy sliding mode controller for a series active variable geometry suspension. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering, 44(9), 425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-022-03735-0

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-022-03735-0 -

Ni, L. W., Wu, L., Zhang, H. S. (2022). Parameters uncertainty analysis of posture control of a four-wheel-legged robot with series slow active suspension system. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 175, 104966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2022.104966

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2022.104966 -

Pan, B., & Xu, H. (2022). Magnetic levitation control system based on ADAMS-MATLAB co-simulation. In 2022 5th International Conference on Mechatronics, Robotics and Automation (ICMRA) (pp. 47-52). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMRA56206.2022.10145626

» https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMRA56206.2022.10145626 -

Rodriguez-Guevara, D., Favela-Contreras, A., Beltran-Carbajal, F., Sotelo, C., Sotelo, D. (2022). An MPC-LQR-LPV controller with quadratic stability conditions for a nonlinear half-car active suspension system with electro-hydraulic actuators. Machines, 10(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10020137

» https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10020137 -

Shao, M. X., Xin, Z., Jiang, Q. B., Zhang, Y. A., Du, Y. F., & Yang, H. F. (2019). Fuzzy PID control for lateral pose adjustment of tractor rear suspension. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 35(21), 34-42. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2019.21.005

» https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2019.21.005 -

Shi, X. H., Jiang, X., Zhao, J., Zhao, P. Y., Zeng, J. (2018). Seven degrees of freedom vehicle response characteristic under four wheel random pavement excitation. Science Technology and Engineering, 18(27), 71-78. [In Chinese]. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2018.27.012

» https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2018.27.012 -

Wang, L. J., Yan, J. G., Hou, Z. F., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Design and experiment on agricultural field profiling apparatus. Journal of Shenyang Agricultural University, 49(4), 425-432. [In Chinese]. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1700.2018.04.006

» https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1700.2018.04.006 -

Xu, Z. F., Xue, X. Y., Cui, L. F. (2017). Measurement and analysis of farmland surface roughness. Journal of Agricultural Mechanization Research, 39(1), 171-176. [In Chinese]. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-188X.2017.01.034

» https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-188X.2017.01.034 -

Yang, Z., Shi, C., Zheng, Y., Gu, S. (2022). A study on a vehicle semi-active suspension control system based on road elevation identification. PloS One, 17(6), e0269406. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269406

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269406 -

Yin, J., Chen, X. B., Wu, L. X., Liu, Y. L. (2017). Simulation method of road excitation in time domain using filtered white noise and dynamic analysis of suspension. Journal of Tongji University (Natural Science), 45(3), 398 - 407. https://doi.org/10.11908/j.issn.0253-374x.2017.03.014

» https://doi.org/10.11908/j.issn.0253-374x.2017.03.014 -

Zhang, Y. L., Zhang, J. F. (2006). Numerical simulation of stochastic road process using white noise filtration. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 20(2), 363-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2005.01.009

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2005.01.009 -

Zhao, H. P., Hang, H. C., Li, H. G., Zhang, J. W. (2001). Dynamic characteristics of vehicle suspension with non-linear springs. Journal of System Simulation, (5), 649-651. https://doi.org/10.16182/j.cnki.joss.2001.05.034

» https://doi.org/10.16182/j.cnki.joss.2001.05.034 -

Zhao, H., Lu, S. F. (1999). A vehicle’s time domain model with road input on four wheels. Automotive Engineering (2), 112 - 117. [In Chinese]. https://doi.org/10.19562/j.chinasae.qcgc.1999.02.009

» https://doi.org/10.19562/j.chinasae.qcgc.1999.02.009

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

João Paulo Arantes Rodrigues da Cunha

-

Edited by

SBEA

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

14 Mar 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

7 July 2024 -

Accepted

18 Jan 2025

DESIGN AND FIELD TEST OF FUZZY PID CONTROL SYSTEM OF ACTIVE SUSPENSION FOR BLUEBERRY HARVESTER

DESIGN AND FIELD TEST OF FUZZY PID CONTROL SYSTEM OF ACTIVE SUSPENSION FOR BLUEBERRY HARVESTER