Abstracts

After the First World War, foreign cultural policy became one of the few fields in which Germany could act with relative freedom from the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. In this context the Hamburg doctors Ludolph Brauer, Bernhard Nocht and Peter Mühlens created the Revista Médica de Hamburgo (as of 1928 Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana), a monthly medical journal in Spanish (and occasionally in Portuguese), to increase German influence especially in Latin American countries. The focus of this article is on the protagonists of this project, the Hamburg doctors, the Foreign Office in Berlin, the German pharmaceutical industry, and the publishing houses involved.

Revista Médica de Hamburgo; Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana; German foreign cultural policy; foreign cultural propaganda; Latin America

Depois da Primeira Guerra Mundial, a política cultural externa tornou-se um dos poucos campos em que a Alemanha podia atuar com relativa liberdade das restrições impostas pelo Tratado de Versalhes. Nesse contexto, os médicos Ludolph Brauer, Bernhard Nocht e Peter Mühlens, de Hamburgo, criaram a Revista Médica de Hamburgo (a partir de 1928 Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana), um periódico mensal em espanhol (e ocasionalmente em português), para aumentar a influência alemã principalmente nos países da América Latina. O foco desse artigo são os protagonistas desse projeto: os médicos de Hamburgo, o Ministério das Relações Exteriores, a indústria farmacêutica alemã e as editoras.

Revista Médica de Hamburgo; Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana; política cultura externa alemã; propaganda cultural no estrangeiro; América Latina

BRAZIL-GERMANY: MEDICAL AND SCIENTIFIC RELATIONS DOSSIER

The Revista Médica project: medical journals as instruments of German foreign cultural policy towards Latin America, 1920-1938

O projeto Revista Médica: periódicos médicos como instrumentos da política cultural externa alemã para a América Latina, 1920-1938

Stefan Wulf

Research Associate, Department of History and Ethics of Medicine/ University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Martinistraße 52 20246 Hamburg - Germany. s.wulf@uke.de

ABSTRACT

After the First World War, foreign cultural policy became one of the few fields in which Germany could act with relative freedom from the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. In this context the Hamburg doctors Ludolph Brauer, Bernhard Nocht and Peter Mühlens created the Revista Médica de Hamburgo (as of 1928 Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana), a monthly medical journal in Spanish (and occasionally in Portuguese), to increase German influence especially in Latin American countries. The focus of this article is on the protagonists of this project, the Hamburg doctors, the Foreign Office in Berlin, the German pharmaceutical industry, and the publishing houses involved.

Keywords:Revista Médica de Hamburgo; Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana; German foreign cultural policy; foreign cultural propaganda; Latin America.

RESUMO

Depois da Primeira Guerra Mundial, a política cultural externa tornou-se um dos poucos campos em que a Alemanha podia atuar com relativa liberdade das restrições impostas pelo Tratado de Versalhes. Nesse contexto, os médicos Ludolph Brauer, Bernhard Nocht e Peter Mühlens, de Hamburgo, criaram a Revista Médica de Hamburgo (a partir de 1928 Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana), um periódico mensal em espanhol (e ocasionalmente em português), para aumentar a influência alemã principalmente nos países da América Latina. O foco desse artigo são os protagonistas desse projeto: os médicos de Hamburgo, o Ministério das Relações Exteriores, a indústria farmacêutica alemã e as editoras.

Palavras-chave: Revista Médica de Hamburgo; Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana; política cultura externa alemã; propaganda cultural no estrangeiro; América Latina.

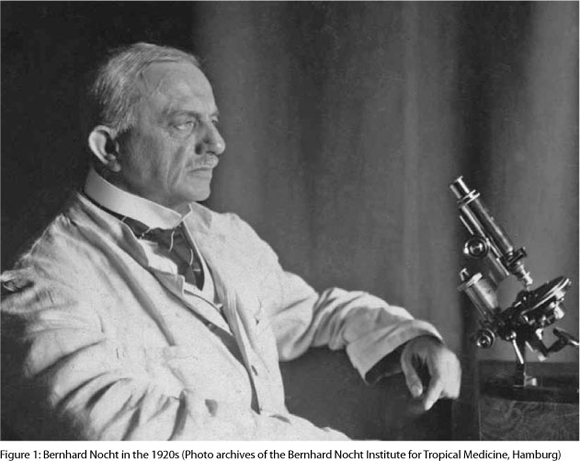

On May 17, 1914, the Hamburg doctor and hygienist Peter Mühlens1 1 Peter Mühlens (1874-1943): German physician, professor; tropical disease specialist, hygienist and malaria specialist; 1899-1911 naval doctor, as of 1910 staff of the Hamburg Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases; 1933-1943 director of the Hamburg Tropical Institute (Wulf, 2010b; Wulf, 1997; see also Mannweiler, 1998, p.227f.). , a staff member of the Institut für Schiffs- und Tropenkrankheiten (Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases) in Hamburg, sat in his hotel room at the Grand Hotel Kroecker in Constantinople, the capital city of the Ottoman Empire, and wrote a detailed letter to his superior Bernhard Nocht2 2 Bernhard Nocht (1857-1945): German physician, professor; tropical disease specialist and hygienist; 1883-1893 naval doctor; 1893-1906 Hamburg's first port doctor; 1900-1930 founder and director of the Hamburg Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases; 1906-1919 director of the Public Health Service in Hamburg; 1926-1927 president of Hamburg University; 1927 appointed vice president of the Hygiene Commission of the League of Nations (Wulf, 2010a; Wulf, 1999; see also Mannweiler, 1998, p.230f.). , the Hamburg institut's founder and director (Mühlens, 17 May 1914).

Mühlens was in a rage. Since 1912 he had been studying and treating malaria in Palestine, particularly in Jerusalem (Wulf, 2005, p.3-75). Now, in the spring of 1914, he had finished this project and turned to a new mission: sanitation along the railway line to Bagdad, with a special eye to cultural propaganda opportunities in this strategically important part of the Ottoman Empire (Wulf, 2005, p.76-99). The Bagdad railway was Germany's most important project abroad. Mühlens was, however, not the only German doctor interested in this field of work: Ludolph Brauer3 3 Ludolph Brauer (1865-1951): German physician, professor; specialist in heart and lung diseases and tuberculosis; surgeon; 1905-1910 director of the University Medical Clinic in Marburg; 1910-1934 director of the General (later University) Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf; 1930-1931 president of Hamburg University (Weisser, 1989, p.55f., p.568; Weisser, 1992; Knipping, Venrath, 1955). , director of the General Hospital in Hamburg-Eppendorf, and his staff member Hans Much, were serious competitors.

Mühlens had found out that Much was expected in Turkey to inspect the Bagdad railway area and was extremely upset by this rivalry. Mühlens claimed both the medical and intellectual leadership of the sanitation and cultural penetration of this region for the Hamburg institute; but actually, he claimed it for himself. People like Brauer and Much, Mühlens wrote to Nocht, should be fought without regard or respect. They should be made 'dead' (müssen totgemacht werden or "put out of commission"), so Mühlens put it in the strongest possible terms in his letter.

Mühlens was very annoyed with Brauer's intense activities in foreign countries. Some weeks before, Brauer had founded a medical journal, the Hamburgische medizinische Überseehefte4 4 The journal Hamburgische medizinische Überseehefte was published between 1914 and 1916. A total of 19 issues were released. Before World War I the journal appeared fortnightly; after the beginning of the war, irregularly. The Überseehefte was published by Fischer's medicinische Buchhandlung H. Kornfeld, Berlin. (Hamburg Medical Journals for the Overseas). From Mühlens's point of view, Brauer's journal was a challenge, a declaration of war against Nocht and his institution, and particularly against Mühlens himself and his own international ambitions.

Shortly afterwards the First World War broke out, pushing all such small-minded matters, like quarrels between the Hamburg doctors Mühlens and Brauer, into the background. The war was a catastrophe; and Germany was the loser. As a consequence of the Treaty of Versailles in the summer of 1919, Germany lost all its colonies, located primarily in Africa, and the larger portion of its fleet (Kolb, 2005; Krüger, 1993). The country was almost completely isolated. An international boycott was declared on German science. Founded as an institution specialized in colonial medicine (and maritime diseases), the future of the Hamburg institute was put in serious jeopardy, a state of affairs that lasted for many years.

Nocht and his staff, first and foremost Peter Mühlens, made the Hamburg institute an agency for foreign cultural propaganda, and this turned out to be a successful way to keep it alive. Tropical medicine had all the key requisites to re-establish German science and culture internationally, to overcome Germany's isolation and to regain a foothold for Germany in foreign trade and commerce. In Hamburg all efforts were concentrated on reclaiming Germany's former importance.

In this context the erstwhile opponents Mühlens and Brauer along with Nocht worked together closely to create a monthly medical journal for use as an instrument of cultural propaganda in foreign countries: the Revista Médica de Hamburgo. It was published in Spanish (and to a lesser extent in Portuguese) and its intent was to increase German influence in Spain and the countries of Latin America. The new periodical was edited by Ludolph Brauer and Bernhard Nocht, and mainly organized by Peter Mühlens as redactor jefe (editor-in-chief). The first edition of Revista Médica was released in April 1920.

A few remarks on the state and questions of research

The subject of my article is the medical journal Revista Médica de Hamburgo and its successor, Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana. These journals were intended to be and in fact served as instruments of German cultural policy in all Spanish-speaking countries, especially in Latin America (including Brazil). They contain articles by German medical scientists, reports on German conferences, and reviews of new German books. They also contain advertisements for German pharmaceutical products and medical equipment and for German health resorts and clinics. To bind foreign scientists to Germany and German medical science, foreign doctors were invited to cooperate as members of the editorial board or to publish articles in Revista Médica.

With his important book about Deutschlands auswärtige Kulturpolitik (Germany's foreign culture policy) in the Weimar Republic Kurt Düwell (1976) provides a key to understanding this subject and its field of research. He distinguishes between cultural influence, cultural expansion, cultural propaganda and cultural imperialism (p.28-38). Two criteria are mainly responsible for his definitions: (1) the degree of autonomy of culture and the extent of its use for political or economical purposes; and (2) the degree of acceptance of the other nation as an equal partner in cultural exchange. According to Düwell (p.36), cultural propaganda is a systematic international promotion of one's own culture for the purposes of national power expansion with a limited willingness to accept other nations as equal partners of cul-tural cooperation. It could be said that foreign cultural propaganda is certainly foreign cultural policy, but foreign cultural policy is not necessarily propaganda.

At this point it should be emphasized that the term Propaganda in Germany, often used by Mühlens and his colleagues after the First World War, has undergone a special historical change of meaning. Its militant use by Hitler and Goebbels and its boom in the 'Third Reich' have led to a very negative perception of this term, which is now seen in a very pejorative light. Yet just after World War I the term already meant much more than just Werbung (advertisement or promotion): between 1914 and 1918 propaganda was an important instrument of warfare (Albes, 1996). Foreign cultural propaganda after the War was, to a great extent, nothing less than a continuation of the battle, especially against France, using other weapons. Significantly, the so-called Bücherreferat (books department), responsible for the Revista Médica project at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin, had its origins in a former war propaganda news division and after the war was used by the press department for special propaganda purposes (Düwell, 1976, p.92,188; cf. also Rinke, 1996, p.420-422). On the other hand, officially, in the Berlin ministry, there were strong reservations about the use of the term propaganda after 1919 (Düwell, 1976, p.32f., 86). The structures were very complex. In general, the use of 'propaganda' was less aggressive after Germany became a member of the League of Nations in 1926 (Pfeiffer, 1927). However, there is no doubt that doctors like Mühlens considered themselves propagandists for the German cause which meant fighting the enemy, not just representing German culture.

In his extensive work Friedliche Imperialisten (Peaceful imperialists) Jürgen Kloosterhuis (1994) compiles and discusses the large number of so-called Auslandsvereine prior to World War I. These were mostly private societies which ostensibly served to promote cultural exchange and international cooperation but in fact pursued German interests in foreign countries all over the world. These societies were mainly created and funded by private persons and business people but were often supported, influenced and controlled by public authorities. Kloosterhuis underlines the essential meaning of private initiatives and semi-official activities in other countries as a successful strategy of the German foreign cultural policy. Semi-official activities provoked less international irritation than an official policy would have done. This principle was also effective as well after World War I. Revista Médica de Hamburgo is a significant example of this specific kind of cultural policy abroad. Against the background of their special Hamburg interests, Brauer, Nocht and Mühlens took the initiative of founding this medical journal immediately after the war. In the context of German foreign policy they could be regarded as semi-official political protagonists. Thus, we have especially to look at the relationship and co-operation between the Hamburg doctors on the one hand and public authorities (the Foreign Office) on the other.

A large part of the historical documents from the 1920s and 1930s belonging to the Hamburg Tropical Institute are dominated by the intentions, attitudes and ideas of foreign cultural propaganda. Reports and letters written by Hamburg tropical doctors like Mühlens and also Fülleborn, for example, were often labeled confidential and thus not destined for publication; they contained extensive reflections and strategies on how to influence and manipulate foreign doctors and authorities successfully. In my book on the Hamburg institute's history (Wulf, 1994), I demonstrate this, especially with regard to the Weimar Republic. During this period, a wide variety of propaganda instruments were in use to exert influence over the countries of South and Central America first and foremost, but also over countries like Russia, Japan and China. Revista Médica played a very important role in this context. The most active person at the institute was Peter Mühlens, who made three extensive journeys to Latin America between 1924 and 1931 not only to study and to combat malaria and other tropical diseases but primarily to promote his Hamburg and German propaganda.

Using the example of the Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases in Hamburg I attempted to show in detail the modus operandi and the diversity of methods employed in the field of foreign cultural propaganda activities. In contrast to my work, Stefan Rinke (1996, p.413-488) has discussed the German cultural policy in South and Central America at large, briefly investigating Mühlens and his Hamburg colleagues' propaganda activities in the broader cultural political context. Both perspectives - the detailed case study on the one hand and the general overview on the other - are equally important and complement each other in a meaningful manner.

Looking at Revista Médica in particular, it must be pointed out that the Brazilian researchers Magali Romero Sá and André Felipe Cândido da Silva were the first to make the history of this journal the subject of a specific scientific publication (Sá, Silva, 2010). Their article on Revista Médica is the result of current research activity at Casa de Oswaldo Cruz in Rio de Janeiro to investigate the political implications of the medical and scientific relations between Brazil on the one hand and Germany and France on the other, between 1919 and 1942 (Sá et al., 2009). A number of works on the cultural relationship between Hamburg and Latin America have been produced in the Department of History at Hamburg University (e.g. Urban, 2000; Brahm, 2002). Thematically, the Brazilian article mentioned above corresponds to Rüdiger Buchholtz's (1999) study of El Heraldo de Hamburgo, a journal which was published between the years 1914 and 1923.

For many years, I have been collecting historical documents and information on Revista Médica. I perceive the present article, based on my lecture at Casa de Oswaldo Cruz (Rio de Janeiro) in March 2011, as a very welcome opportunity for a first approach to this issue by using largely unknown historical sources from different German archives. My focus will be on the protagonists: their conceptions, actions, correspondence, negotiations, agreements and controversies. I am particularly interested in the specific cooperation between medical science in Hamburg, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin, the German pharmaceutical industry, and the participating publishing houses in Leipzig and Berlin. The main question is: How did this mode of propaganda work?

First, I will reflect on continuities and discontinuities relating to Revista Médica and German and Hamburg foreign cultural policy before and after World War I. Next, I will provide an analysis of the Revista Médica de Hamburgo project between 1920 and 1928 based on the files of the Political Archives of the German Foreign Office in Berlin. Then, I will look at Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana between 1928 and 1938, drawing on relevant files from I.G. Farben in the Bayer archives at Leverkusen. Finally, a short conclusion will reflect on the challenges to future research.

Continuities and discontinuities

On September 11, 1920, Ludolph Brauer wrote a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin. The subject of this letter was the newly founded Revista Médica de Hamburgo. He wrote that Revista Médica had been established by Nocht and himself purely for national and idealistic reasons. Brauer underlined that he had actually created this journal already prior to the war, but that its publication had been interrupted by the outbreak of the hostilities (Brauer, 11 Sep. 1920).

In the archives of the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce I found an extremely interesting document which is very important in this context (Schädel, Brauer, 15 Dec. 1913). It is an elaborate propaganda concept written by Ludolph Brauer and a Hamburg-based Romance language specialist, Bernhard Schädel, who later founded and directed the Hamburg Ibero-American Institute (Settekorn, 1990). The manuscript is dated December 15, 1913, and contains suggestions for future activities of Hamburg science in relation to South America. Brauer intended to establish a South American medical archive at his Hamburg hospital, meaning a collection and information service point for observing the development of medicine in South American countries. Attached to this paper is a proposed budget including the costs for the projected office and the two medical journals which were intended for future publication: Hamburgische medizinische Überseehefte and Revista Médica de Hamburgo.

Originally, the two journals - the Überseehefte in German and the Revista Médica de Hamburgo in Spanish - were planned as coexisting publications. According to Brauer and Schädel, the journals should serve as a special propaganda tool for Hamburg medical science in South America and support the influence of the Hamburg economy there. From Brauer's point of view, the Revista Médica was the most important project in this context. The more one could 'chain' (ketten) the leading intellectuals and property-owners from South America to Hamburg science, the better it would serve the interests of Hamburg trade and commerce. According to this conception, the South American psyche should be continuously worked upon. South American people should be 'educated' consistently in favour of Hamburg and Germany. Thus, before the First World War, Brauer and like-minded Hamburg scientists were more interested in the cultural penetration of South American countries than in cooperation with them as equal partners. But only a single issue of the Revista Médica was published before the war began, in July 1914. Many years later, Brauer remembered that five thousand copies of the first issue of Revista Médica had been produced (Brauer, s.d.).

The archives of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, as the institute is now called, contain a confidential memorandum from the so-called Vereinigung der Freunde des Hamburger Tropeninstituts (Association of the Friends of the Hamburg Tropical Institute) dated August 1921 and signed by Hamburg doctors and influential Hamburg businessmen (Vereinigung..., Aug. 1921).5 5 Published in Mannweiler (1998, p.72f.).

A program to support Nocht's institution was adopted. Mühlens can be regarded as the initiator of and driving force behind this collaboration. The Hamburg Tropical Institute was expected to serve economical and political purposes. Medical science was intended to open the way to new markets abroad. The idea was overseas, there could be no better propaganda instrument for one's own nation than tropical medicine. Medical science was designed as a sort of door-opener in foreign countries favorable to industry and commerce. Accordingly, Revista Médica de Hamburgo was regarded as an effective instrument, providing information on the achievements of German (tropical) medicine, of the German pharmaceutical industry, and German medical technology. By presenting Germany's excellence in these fields, the journal was intended to support a strategy of door-opening in all Spanish-speaking countries.

Considered in the light of scientific relations between Germany and foreign nations, Peter Mühlens was one of the most interesting German doctors around, especially in Latin America. A comparison of his post-war reports and correspondence (Wulf, 1994, p.13-26, 49-63, 77-86) with the pre-war report written about his trip in 1914 from Palestine to Constantinople, crossing the area of the Bagdad railway (Wulf, 2005, p.76-99), leaves no doubt that the political strategy he pursued during the Weimar Republic era had already been developed prior to the First World War. Before and after the war, though under completely different international circumstances, Mühlens fought first and foremost against the same enemy: France, French medical science and culture, and its influence in other countries. Mühlens's very clearly-defined ideas for using his professional field and his reputation as a well-known malaria specialist to further his country's cultural influence abroad as a method of propaganda after the war had their conceptual roots in the years of the late Wilhelminian era.

Before 1914, wide circles of the educated classes and official authorities in Germany, being convinced of the superiority of their own culture, had identified cultural policy abroad as a necessary extension of the traditional instruments of foreign policy, an essential part of Germany's 'informal imperialism'. After the war, foreign cultural policy became one of the few fields in which Germany could act relatively freely from the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles. Ludolph Brauer and Peter Mühlens, together with Bernhard Nocht, reactivated their pre-war propaganda strategies towards other nations and imposed them on a quite different political situation. Founding a new Revista Médica as a combined effort in 1920 was a response to the completely new political circumstances after Versailles. But the intellectual and conceptual origins of the project harked back to a different world from which the Hamburg doctors had never really detached themselves. Mühlens and Brauer, like many other Germans, were still convinced of their own and their nation's superiority, but were forced to realize that their country and their scientific disciplines were completely and almost hopelessly isolated internationally. Bridging this gap emotionally was a great and almost insurmountable challenge. Thus, many relevant historical documents contain a peculiar assortment of quite different, sometimes contradictory attitudes.

The Revista Médica de Hamburgo, 1920-1928

During the so-called Schülersche Reform 1919-1920 - reforms led by Edmund Schüler, a senior official at the Berlin Ministry of Foreign Affairs - a Cultural Department was founded at the German Foreign Office (Düwell, 1976, p.78-102; cf. Doß, 1977). Beginning in 1921, Friedrich Heilbron6 6 Friedrich Heilbron (1872-1954): senior official of the German Foreign Office and the Reichskanzlei in Berlin (1920 Ministerialdirektor); 1895-1902 journalist ( Hamburgischer Correspondent); as of 1902 Foreign Service (Berlin); 1921-1926 director of the Cultural Department of the German Foreign Office; 1920 and 1923 press chief of the German government; 1926-1931 consul general in Zürich (Switzerland) (Keipert, Grupp, 2005, p.232f.). headed this department, which had been created due to the increasing importance and changed role of cultural activities abroad. In context of the ministry's reform, the Cultural Department was basically the only one divided according to an issue-related principle and not for territorial reasons. In the beginning, the Cultural Department (dept. IX, after 1922 dept. VI) had four divisions (A through D). Division D (Bücherreferat) was responsible for the distribution of German literature in foreign countries, the exchange of scientific books and journals, German scientific institutions abroad, and the exchange of scientists with other countries (Düwell, 1976, p.91f.).

In division D, Ernst Bischoff7 7 Ernst Bischoff (1880-1958): official of the German Foreign Office (1923 Gesandtschaftsrat II. Kl.), Dr. phil.; 1906-1915 journalist (Italy, Japan, China); as of 1915 Foreign Service (Berlin); 1920-1924 department head of the so-called "Bücherreferat" (Cultural Department, division D) of the Foreign Office; 1925-1926 German embassy in Tokyo (Japan); 1926-1934 consulate general in Kobe (Japan); since 1934 consul, 1939 consul general in Dairen (Japan, today China); 1945-1953 in custody (USSR) (Keipert, Grupp, 2000, p.162f.). was the specialist in questions of so-called 'literature propaganda'; that is, he was also responsible for Revista Médica de Hamburgo. Bischoff supported the journal and closely cooperated with the editors and the publisher between 1920 and 1924. Negotiations with the Cultural Department in Berlin were mainly conducted through Ludolph Brauer, but Kurt Kornfeld8 8 Kurt Kornfeld (1887-1967): German publisher; as of 1914 owner of Fischer's medicinische Buchhandlung H. Kornfeld, Berlin; after 1933 emigrated to New York: 1935-1936 co-founder of the famous US photo agency Black Star (Life) (Neubauer, 1997, p.6-27; Chapnick, Jan.-Feb. 2000). , owner of Fischer's medicinische Buchhandlung H. Kornfeld publishing house in Berlin and publisher of Revista Médica, also played an active part. Peter Mühlens was the man behind the scenes, primarily responsible for editorial tasks and the journal's content, as well as building networks abroad. Bernhard Nocht was a rather passive editor. He lent his internationally well-respected name to the project but did not play a significant role, neither in corresponding with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs nor in the later liaison with the pharmaceutical industry. However, his visit to Rio de Janeiro in 1929 was an important cultural and political event (Wulf, 1994, p.72f.).

From the very beginning the Cultural Department of the Berlin Ministry of Foreign Affairs promoted and coordinated the global distribution of Revista Médica. To give just one example, in November 1920, the department sent a hundred copies of the journal to the German embassy in Madrid at its own expense (Deutsche Botschaft..., 29 Sep. 1920; Bischoff, 2 Nov. 1920, 12 Nov. 1920). In another step, the German embassies in certain capital cities, including Madrid, sent copies of the journal to strategically important persons and institutions and to German doctors who worked abroad. These German contacts then reported to Berlin how the new journal was perceived in 'their' country and which strategies might be successful in promoting the project. In Buenos Aires, for example, in 1920, two established German physicians wrote very critical opinions on the first issues of Revista. They criticized the 'de Hamburgo' element of the journal's name, saying that it was too specific. They also criticized the intrusive advertising and primitive design (Deutsche Gesandtschaft..., 14 Aug. 1920; Gutachten Kraus, Aug. 1920; Gutachten Merzbacher, Aug. 1920). These statements were sent from Berlin to the Revista's editors in Hamburg who could then improve the journal if necessary. Interestingly, when in September 1920 Brauer first wrote to the Berlin ministry to introduce his journal (see above), Bischoff had already been working in support of Revista Médica.

Short excursus: in July 1920, Peter Mühlens (together with the Hamburg-based psychiatrists Wilhelm Weygandt and Walter Kirschbaum) published a remarkable article in Revista Médica presenting the first Hamburg results of general paralysis treatment by means of so-called malaria fever therapy (Mühlens, Weygandt, Kirschbaum, 1920b). The article was highly topical. It was released in Spanish at the same time as the original text was published in Germany (Mühlens, Weygandt, Kirschbaum,1920a). In 1917, the Viennese psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg had discovered that the symptoms of general paralysis clearly decreased or even disappeared entirely after patients suffered from malaria. Until that point, general paralysis, with its severe symptoms - a long-term consequence of syphilis - had been deadly in nearly all cases. In June 1919, Mühlens and Weygandt had contaminated the first Hamburg patients artificially with malaria parasites. At the same time, the Allied powers were debating and deciding on the end of the German colonial empire in Versailles (Wulf, Schmiedebach, 2012).

With the help of the article mentioned above, Mühlens was able and surely intended to show that German tropical medicine was still alive, despite the Treaty of Versailles. Moreover, internationally isolated German medical science was able to offer the international community important results and possible solutions for one of its most serious diseases. In the following decades, the new method was internationally accepted and considered the only promising therapy available. It would only be replaced in the second half of the twentieth century by penicillin. However, during the first years after World War I, the Hamburg asylum for the mentally ill in Friedrichsberg became the tropical doctor's new place of work, instead of Togo, Cameroon or Jerusalem.

Ludolph Brauer was very interested in applying the basic principle of Revista Médica de Hamburgo to other cultural and linguistic areas. He was supported by Bischoff and the Cultural Department in Berlin in this regard. In September 1920, Brauer had already considered a Revista Médica for Yugoslavia in favour of German cultural propaganda in the Eastern European Balkans (Brauer, 15 Sep. 1920). From 1921 to 1923 an Italian version of Revista Médica was considered. Brauer and Kornfeld were supported not only by Bischoff, but also by the Consulate General in Milan. In 1922, they travelled on the authority and at the expense of the Foreign Office to Italy to prepare the Italian Revista Médica (Deutsches Generalkonsulat..., 2 Jan. 1922; Bischoff, 18 Feb. 1922; Brauer, 21 March 1922; Deutsche Botschaft..., 25 Jan. 1923). Between 1922 and 1924 Brauer was also fully committed to creating a Russian version of Revista Médica; the Cultural Department coordinated the preliminaries and the relevant German diplomatic missions to Russia and Eastern Europe were involved (Brauer, 5 Dec. 1922, 20 Mar. 1924; Kornfeld, 15 Sep. 1923). This project can only be understood against the background of Mühlens' intense activities in Russia in 1921-1922 (Wulf, 1994, p.13-26; Mühlens, s.d.-b). Finally, in 1923, Brauer suggested creating a Hebrew version of the journal, foreseeing the future importance of the Zionist movement (Brauer, 15 Jan. 1923).

As far as could be ascertained, none of these projects was carried through as planned and prepared by Brauer, Kornfeld and Bischoff. Instead of "Folia Medica" (Brauer's idea for the Russian version of Revista Médica de Hamburgo), a different journal was published from October 1925 to December 1928, under the title of Deutsch-russische medizinische Zeitschrift (German-Russian Medical Journal). Friedrich Kraus (Charité Berlin) and Nikolai Semashko, the Soviet People's Commissar of Public Health, were the editors-in-chief. Brauer, however, was only included as a member of the editorial staff. Also in October 1925, the first issue of another new medical journal was published in China: Tung-Chi. Medizinische Monatsschrift.9 9 Tung-Chi, Medizinische Monatsschrift was published between 1925 and 1941. This monthly journal was edited in German and Chinese by Ludolph Brauer, and as of January 1926 by Brauer and Nocht. It was closely connected to the Medical Faculty of Tung-Chi University in Shanghai and was based on the scripts and texts of Revista Médica de Hamburgo. All these examples demonstrate that Revista Médica was mainly a political instrument applicable anywhere in the world and in any language, but admittedly well-adapted to Germany's propaganda purposes in Latin America and Spain.

On February 2, 1922, Brauer asked Bischoff to send him the most important German propaganda writings. He planned to build up a stock of political books and brochures for discrete distribution to foreign visitors. Not a day went by, according to Brauer, without a doctor from abroad visiting his hospital in Eppendorf (Brauer, 2 Feb. 1922). Four weeks later Bischoff sent him more than fifty propaganda writings, in fact several copies of almost every book or brochure (Bischoff, 14 Feb. 1922, 1 Mar. 1922). These often extreme and self-righteous writings were intended to convey to other countries the German point of view on war, peace treaties and the post-war period. Their topical focus was the question of the mistreatment of German prisoners-of-war by the Allies.

Brauer's desire to have propaganda documentation was especially intended for Spanish-speaking visitors to Hamburg, primarily from Latin America. Foreign (cultural) propaganda also took place in Germany and Hamburg itself. In later years, Peter Mühlens described this aspect more precisely. According to him, every Latin American doctor educated at the Hamburg Tropical Institute and every Latin American patient successfully treated in a Hamburg hospital could be considered a "cultural propaganda center" (Kultur-Propagandazentrum) after returning in his own country; in other words, these persons were considered as a potential instrument for the pursuit of German, especially Hamburg, interests abroad (Mühlens, 16 Nov. 1928; s.d.-a).

Revista Médica de Hamburgo was not the only German medical journal published in Spanish and distributed in Spain and to the countries of Latin America; it had two keen competitors: Vox médica10 10 The journal Vox Médica, revista mensual de medicina, cirugia y farmacologia (farmacia) was published between 1920 and 1929. and La Medicina Germano-Hispano-Americana.11 11 The journal La Medicina Germano-Hispano-Americana, revista mensual de medicina, cirugia y especialidades was published between 1923 and 1927. Brauer claimed precedence for his Hamburg publication (Brauer, Nocht, Dec. 1922; Brauer, s.d.) and he was strongly supported in this point by Bischoff and the Cultural Department of the Foreign Office (Bischoff, 25 Oct. 1922). But the editors of the other periodicals saw no reason to compromise their positions (Stellungnahme..., Jan. 1923). In November 1924, Bischoff wrote to Julius Schwalbe12 12 Julius Schwalbe (1863-1930): German physician, medical publicist, professor; 1894-1930 editor of the Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (Staehr, 1986, p.48-50; Eckart, Gradmann, 1995, p.324). , the editor of La Medicina, and suggested it merge with Revista Médica. He underlined the fact that the Foreign Office would be exceedingly appreciative of this kind of solution (i.e. to avoid rivalry between German doctors), but Schwalbe refused (Bischoff, 6 Nov. 1924; Schwalbe, 12 Nov. 1924). The conflict continued for many years, until in 1928 Revista Médica and La Medicina were forced to pool their strengths and merge.

There was strong rivalry between different German doctors and various groups in Germany who pursued their own particular interests. This domestic conflict was sometimes carried out aggressively. In a letter to Bischoff from October 1923, Brauer (28 Oct. 1923) ranted against the Berlin Jews and imitated their dialect. This was a serious attack on Schwalbe; while the old rivalry between Mühlens and Brauer continued as Mühlens wove new webs of intrigue around Brauer in 1926. Meanwhile, the structure of the Foreign Office's Cultural Department had changed. Division D had been completely absorbed by other divisions (Düwell, 1976, p.94-98) and Bischoff was no longer responsible for the Revista Médica.

In March 1926, Mühlens took the initiative in the conflict between the different German medical journals in Spanish (Mühlens, 8 March 1926). He acted behind Brauer's back and supported a combination of Revista Médica and Schwalbe's La Medicina. He intended to break the opposition of Brauer and the Revista publisher, Kornfeld, by increasing the pressure on them. Mühlens suggested to Friedrich Heilbron, the head of the Cultural Department, that, if necessary, Revista Médica's financial support be revoked to achieve this. He also installed influential persons in Argentina who spoke out against the status quo of the journal. Mühlens also expressed a preference for the La Medicina publisher, Thieme Verlag, in Leipzig (Staehr, 1986) and referred to the future journal as Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana. Mühlens was certain of the need for such a merger because of Revista Médica's critical financial circumstances.

In February 1923, Brauer had been able to report to Bischoff that Revista Médica de Hamburgo had survived all the economic problems of its initial years of existence. According to Brauer (19-21 Feb. 1923), the Hamburg journal had a large and rising number of subscribers. However, in January 1926, Revista hit serious financial problems, in response to which the editors asked Heilbron for financial support on behalf of German cultural propaganda abroad. Five thousand Reichsmarks were granted for 1926 and again for 1927 (Brauer, Nocht, 6 Jan. 1926; Auswärtiges Amt, 18 Jan. 1926, 19 Nov. 1926; Brauer, 25 Oct. 1926). Revista could continue to be published, but only in reduced volume. In the autumn of 1928, the structure of its support changed. Henceforth, it was primarily the pharmaceutical industry which funded the new Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana. In March 1926, Mühlens informed the Foreign Office of the successful negotiations between Revista and I.G. Farben in Elberfeld (Mühlens, 24 Mar. 1926).

The Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana, 1928-1938

Mühlens's attack on Revista Médica de Hamburgo in 1926 was successful. In October 1928 the first issue of Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana was published by Thieme Verlag in Leipzig and Fischer's medicinische Buchhandlung H. Kornfeld in Berlin. After 1928, publisher Kurt Kornfeld remained in the background while Bruno Hauff13 13 Bruno Hauff (1884-1963): German publisher, Dr. med. h.c.; as of 1919 co-owner and after Thieme's death in 1925, sole owner of Georg Thieme publishing house in Leipzig; after 1945 rebuilt Thieme Verlag (in Stuttgart) as one of the most important German medical publishing houses, with international activities and reputation (Staehr, 1986, p.92f.; Köbcke, 1969). , from Thieme, took over the main responsibility.14 14 As of 1929 Hauff was the co-owner of Fischer's medicinische Buchhandlung, which merged completely with the Thieme Verlag in 1935. The new periodical was also called Geribam, an abbreviation of germano-ibero-americana. The economic interests of the German pharmaceutical industry abroad were a driving force for Germany's cultural propaganda in Latin America, but Geribam was also supported by the Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Foundation of the German Sciences).

The editors of the new Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana were Brauer, Mühlens, Nocht and Schwalbe, as well as the Argentine doctors Francisco C. Arrillaga15 15 Francisco C. Arrillaga (1886-1950): Argentine physician, professor; studied in Buenos Aires, Berlin, Heidelberg, Paris, London and USA; specialized in clinical medicine (cardiology); National University of Buenos Aires (Mediavilla, 1986-2005, p.85, 220; Hilton, 1947-1951, p.19). and Carlos P. Waldorp16 16 Carlos P. Waldorp (1895- not indicated): Argentine physician, professor, land owner; studied in Buenos Aires, Berlin and Paris; specialized in clinical medicine; National University of Buenos Aires (1944-1945 intermediate director) (Mediavilla, 1986-2005, p.70-72, 955). , who had already been co-editors of Schwalbe's La Medicina. No doubt, Revista Médica was particularly intended for medical circles in Argentina as it had an agency in Buenos Aires, but Brazil was also the editor's focus as an important target country even though its population spoke Portuguese. The prominent Brazilian doctors Carlos Chagas17 17 Carlos Chagas (1879-1934): Brazilian physician and hygienist, professor; 1909 first description of American trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease) and the then unknown parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi (named after Oswaldo Cruz); 1917-1934 director of Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro; 1919-1926 director of Brazil's federal public health services (Kropf, Lacerda, 2009). , Miguel Couto18 18 Miguel Couto (1864-1934): Brazilian physician, politician, professor; specialized in clinical medicine; 1913-1934 president of the Academia Nacional de Medicina, Rio de Janeiro; 1916 elected member of the Academia Brasileira de Letras; since 1927 Honorary President of the Associação Brasileira de Educação. and Henrique da Rocha Lima19 19 Henrique da Rocha Lima (1879-1956): Brazilian physician, professor; 1909-1927 staff member of the Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases in Hamburg (head of the department of anatomical pathology); as of 1933 director of the Instituto Biológico, in São Paulo (Silva, 2011). were permanent collaborators of Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana.

Rocha Lima, a leading staff member of Nocht's Tropical Institute between 1909 and 1927 and an early member of the editorial staff of Revista Médica de Hamburgo, was a highly important link between Hamburg and Brazil (Silva, 2011; Sá, Silva, 2010, p.20f.; Wulf, 1994, p.73f.). Thus, there are several articles by Brazilian physicians in Revista Médica de Hamburgo published in Portuguese (e.g. Couto, 1926). As early as the early 1920s, Brazil had been in the focus of the Revista's editors and its publisher, Kornfeld (Kornfeld, 11 Apr. 1921, 19 Apr. 1921; Deutsche Gesandtschaft..., 14 June 1921). In the preface to the first issue of Geribam in October 1928, it was explicitly underlined that the new journal was intended to extend its sphere to include the Iberian Peninsula as a whole and Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking Latin American countries (Revista Médica..., 1928). Until at least September 1936 plans were discussed to found a Portuguese version of Revista Médica for Brazil (Deutsch-Ibero-Amerikanische..., 28 Sep. 1936).

The files in the Bayer archives on the topic of Geribam contain the draft of a contract from the summer of 1928, which intended to join Cepha (Verband der Chemisch-Pharmazeutischen Großindustrie, Frankfurt) and the Revista publishers, Hauff and Kornfeld (Vertragsentwurf..., 1928). Cepha was the most important pharmaceutical industry association in Germany until 1933, and included I.G. Farben, Schering, Boehringer (Mannheim), Boehringer (Hamburg), Merck, and other companies (Kobrak, 2002, p.249f.). The contract period was five years. Cepha guaranteed eight thousand Reichsmarks annually, to lower the price of the journal, and Cepha subscribed a specific number of pages of advertisements (totalling eighteen thousand Reichsmark). A Geribam circulation of 2,500 copies was the goal.

The documents on Revista Médica at the Leverkusen archives tell the story of a project which, to a large extent, ultimately failed. There was a large gap between ambitions and reality. At the beginning of 1932, several member companies of Cepha expressed their dissatisfaction with the development of the journal abroad. They wanted to end the cooperation agreement; that is, they wanted to withdraw their financial support as soon as possible (Zusammenfassung..., s.d.). However, the contract was valid until autumn 1933. In a letter from February 1932, Peter Mühlens categorically refused to interrupt publishing Geribam as had been suggested. According to Mühlens, French and US influence in Latin America had spread 'alarmingly', and Revista Médica was still one of the few cultural assets Germany had there. Thus, he concluded, Revista had to be continued at any cost (Mühlens, 15 Feb. 1932). After Schwalbe's death in 1930, Mühlens's position of authority was consolidated and he became the main editor of Revista Médica.

In November 1932, Bruno Hauff wrote to Fritz Peiser20 20 Friedrich [Fritz] Peiser (1888-1960): physician (Dr. med.) and pharmacist; as of 1921 Farbenfabriken vorm. Friedr. Bayer et comp., Leverkusen, pharmaceutical-scientific department (1929 director); 1935-1939 activities in England, China (Shanghai), South Africa; as of 1939 Geigy, Basel (Switzerland); 1952 retirement (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen, database). of IG Farben. He assumed that the financial support the pharmaceutical industry provided for the journal would be continued. To give proof of his activity to promote Geribam abroad, Hauff sent Peiser extracts of his correspondence with more than a hundred physicians, influential persons, companies, institutions, libraries and booksellers in a large number of countries (Hauff, 17 Nov. 1932). However, the copies of the numerous letters Hauff had received from abroad painted a quite dismal picture and provoked the opposite reaction to what he had intended. Of course there was general interest in the German journal in Latin American countries - specimen copies were requested - but it seemed impossible to increase the number of subscribers. Hauff, however, was still convinced of Geribam's efficiency as a propaganda instrument abroad.

To give some precise data: after January 1931, the circulation of Revista only averaged two thousand copies in approximately thirty countries; this, compared with up to five thousand copies between 1928 and 1930. The number of subscribers had declined from more than eight hundred at the end of 1930 to 580 two years later and 250 of these were procured by the Revista office in Buenos Aires. All in all, most of the Geribam copies were not sold abroad, but sent free of charge to other countries (Hauff, 22 Dec. 1932). This scenario did not improve in the following years.

The reasons for this failure are understandable: the economic and monetary problems in most of the South and Central American countries in the early 1930s, and the free or almost free distribution of other medical journals, like the Spanish edition of the French Presse Médicale. For example, in November 1931, Paulo Zander from Rio de Janeiro, an ethnic German physician and intermediary between Thieme Verlag and Brazil, reported to Hauff that the prospects for the successful circulation of Revista in Brazil were rather unfavorable at that time due to the importance of French literature, a large number of free journals and the crisis of the Brazilian currency (mil reis). According to Zander (2 Nov. 1931), the fact that Geribam was published in Spanish and not in Portuguese was rather a secondary problem.

The German pharmaceutical industry's main criticism of the Thieme Verlag was that the publisher, Hauff, had not invested his own financial resources in the Revista project. Hauff was considered as having taken none of the risk, and Revista was regarded as rather worthless. Peiser (4 Dec. 1933) criticized Hauff's laborious activities, i.e. he had written much but without success. In the end, after much argument, the contract between Cepha and the Revista publishers was not renewed. The chemical and pharmaceutical industry removed their financial support of Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana completely at the end of 1933 (Cepha-Rundschreiben, 5 Sep. 1933, 27 Sep. 1933, 30 Oct. 1933, 29 Nov. 1933).

On January 30 of the same year, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis took over power in Germany. After that, Revista Médica was increasingly seen as a symbol of the past, an obsolete model (Knoll, 1 Dec. 1933). Beginning in 1933, the Leverkusen files contain concepts for a new German medical journal in gigantic dimensions, partly developed with the participation of Goebbels's new Propaganda Ministry. This journal was intended to be published in English, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian and to represent the supposed dawning of a new era in Germany (Sitzungsprotokoll, 28 June 1934). But all these plans for a new powerful periodical abroad were castles in the air and were never realized as formulated (Fachgruppe..., 20 Jan. 1941).

In September 1933, Peter Mühlens took on the leadership at the Hamburg Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases. As its new director (officially beginning in May 1934), he made this institution a center of colonial revisionism. Mühlens and his staff focused on a return to the former German colonies in Africa (Wulf, 1994, p.87-101), which meant that Latin America lost some of its importance for the Hamburg doctors (Wulf, 1994, p.102-109; cf. Carreras, 2005). Despite this, Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana continued to be published bimonthly until the end of 1938. The specific circumstances of its continuation are difficult to reconstruct. The Geribam papers in Leverkusen only continue until February 1934. Between 1934 and 1936, Thieme Verlag was supported, at least to a very small extent, by the Foreign Office in Berlin due to the role of Revista Médica and other journals published by Thieme in the context of German cultural propaganda abroad (Verlag..., s.d.).

Final considerations

This article is based on historical documents found in German archives. Hence, the history of Revista médica has been told almost exclusively from a German point of view. Indeed, a set of letters from Latin American countries are part of the correspondence from the Berlin Ministry of Foreign Affairs and from the Leipzig publisher, Bruno Hauff. However, systematic research into the history of the journals' impact and reception, not only in Brazil, but also in the other Latin American countries, particularly in Argentina, is needed. Furthermore, investigations are necessary into any Spanish-language medical journals from France or the USA which might be comparable to the German Revista Médica. We cannot tell the whole story of Revista as a phenomenon of international knowledge exchange, political struggle and economic contest in the 1920s and 1930s until these various perspectives and aspects, as well as the appropriate comparisons, have been conducted.

NOTES

Recebido para publicação em janeiro de 2012.

Aprovado para publicação em fevereiro de 2013.

- ALBES, Jens. Worte wie Waffen: die deutsche Propaganda in Spanien während des Ersten Weltkrieges. Essen: Klartext. (Schriften der Bibliothek für Zeitgeschichte, n.4). 1996.

- AUSWÄRTIGES AMT. Auswärtiges Amt to Brauer. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 19 Nov. 1926.

- AUSWÄRTIGES AMT. Auswärtiges Amt to Brauer. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 18 Jan. 1926.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff to Schwalbe. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 6 Nov. 1924.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff, Aufzeichnung für Heilbron. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 25 Oct. 1922.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff to Brauer (Attached: list of the propaganda publications). Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 1 Mar. 1922.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff to Brauer. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 18 Feb. 1922.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff to Brauer. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 14 Feb. 1922.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff to Deutsche Botschaft Madrid. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 12 Nov. 1920.

- BISCHOFF, Ernst. Bischoff to Kornfeld. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 2 Nov. 1920.

- BRAHM, Felix. Die Lateinamerika-Beziehungen des Hamburger Tropeninstituts 1900-1945 Thesis (Magister Artium) - University of Hamburg, Hamburg. Manuscript. 2002.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 25 Oct. 1926.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer, Deutsch-Russische Zeitschrift "Folia Medica". File 1924-1925[B]. (Archiv des Bernhard-Nocht-Instituts für Tropenmedizin, Hamburg). 20 Mar. 1924.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 28 Oct. 1923.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 19-21 Feb. 1923.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 15 Jan. 1923.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 5 Dec. 1922.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 21 Mar. 1922.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 2 Feb. 1922.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 15 Sep. 1920.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 11 Sep. 1920.

- BRAUER, Ludolph. Brauer, Rundbrief Revista Médica Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). s.d.

- BRAUER, Ludolph; NOCHT, Bernhard. Brauer, Nocht to Heilbron. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 6 Jan. 1926.

- BRAUER, Ludolph; NOCHT, Bernhard. Brauer, Nocht. Rundbrief Revista Médica Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). Dec. 1922.

- BUCHHOLTZ, Rüdiger. "El Heraldo de Hamburgo", 1914-1923: eine Hamburger Zeitung für die spanischsprachigen Länder. Thesis (Magister Artium) - University of Hamburg, Hamburg. Manuscript. 1999.

- CARRERAS, Sandra (Ed.). Der Nationalsozialismus und Lateinamerika: Institutionen, Repräsentationen, Wissenskonstrukte. Ibero-Online, Berlin, v.3, n.1. 2005.

- CEPHA-RUNDSCHREIBEN. Korrespondenz betr. Cepha-Rundschreiben. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 29 Nov. 1933.

- CEPHA-RUNDSCHREIBEN. Korrespondenz betr. Cepha-Rundschreiben. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 30 Oct. 1933.

- CEPHA-RUNDSCHREIBEN. Korrespondenz betr. Cepha-Rundschreiben. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 27 Sep. 1933.

- CEPHA-RUNDSCHREIBEN. Korrespondenz betr. Cepha-Rundschreiben. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 5 Sep. 1933.

- CHAPNICK, Benjamin J. [Correspondence]. Benjamin J. Chapnick (Black Star president) to Stefan Wulf. Stefan Wulf's private archives. Jan.-Feb. 2000.

- COUTO, Miguel. O azul de methyleno no impaludismo. Revista Médica de Hamburgo, Berlin, v.7, n.4, p.85-87. 1926.

- DEUTSCH-IBERO-AMERIKANISCHE... Deutsch-Ibero-Amerikanische Ärzte-Akademie to Reichs-Propagandaministerium. 170 (Pharma), 5.6 (Fachgruppe "Pharmazeutische Erzeugnisse", Ausschuss III Werbung) [20]. (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 28 Sep. 1936.

- DEUTSCHE BOTSCHAFT... Deutsche Botschaft Rom to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 25 Jan. 1923.

- DEUTSCHE BOTSCHAFT... Deutsche Botschaft Madrid to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 29 Sep. 1920.

- DEUTSCHES GENERALKONSULAT... Deutsches Generalkonsulat Mailand to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 2 Jan. 1922.

- DEUTSCHE GESANDTSCHAFT... Deutsche Gesandtschaft Buenos Aires to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 14 June 1921.

- DEUTSCHE GESANDTSCHAFT... Deutsche Gesandtschaft Buenos Aires to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 14 Aug. 1920.

- DOß, Kurt. Das deutsche Auswärtige Amt im Übergang vom Kaiserreich zur Weimarer Republik: die Schülersche Reform. Düsseldorf: Droste. 1977.

- DÜWELL, Kurt. Deutschlands auswärtige Kulturpolitik: 1918-1932: Grundlinien und Dokumente. Köln; Wien: Böhlau. 1976.

- ECKART, Wolfgang U.; GRADMANN, Christoph (Ed.). Ärztelexikon: von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert. München: Beck. 1995.

- FACHGRUPPE... Fachgruppe Pharmazeutische Erzeugnisse betr. "Folia Therapeutica". 170 (Pharma); 5.2 (Fachgruppe Pharmazeutische Erzeugnisse, Allgemeines 1935-1942) [35]. (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 20 Jan. 1941.

- GUTACHTEN KRAUS. Gutachten Kraus. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). Aug. 1920.

- GUTACHTEN MERZBACHER. Gutachten Merzbacher. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). Aug. 1920.

- HAUFF, Bruno. Hauff to Peiser (Attached: "Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana"). 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 22 Dec. 1932.

- HAUFF, Bruno. Hauff to Fritz Peiser. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 17 Nov. 1932.

- HILTON, Ronald (Ed.). Who's who in Latin America: a biographical dictionary of notable living men and women of Latin America. Stanford: Stanford University Press. v.5. 1947-1951.

- KEIPERT, Maria; GRUPP, Peter (Ed.). Biographisches Handbuch des deutschen Auswärtigen Dienstes: 1871-1945. v.2. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. 2005.

- KEIPERT, Maria; GRUPP, Peter (Ed.). Biographisches Handbuch des deutschen Auswärtigen Dienstes: 1871-1945. v.1. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. 2000.

- KLOOSTERHUIS, Jürgen. "Friedliche Imperialisten": deutsche Auslandsvereine und auswärtige Kulturpolitik, 1906-1918. Frankfurt a.M.: Lang. 1994.

- KNIPPING, Hugo Wilhelm; VENRATH, Helmut. Ludolf Brauer (1865-1951). In: Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Ed.). Neue Deutsche Biographie v.2. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p.540f. 1955.

- KNOLL. Knoll to Strasser. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 1 Dec. 1933.

- KÖBCKE, Heinz. Bruno Hauff (1884-1963). In: Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Ed.). Neue Deutsche Biographie v.8. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p.86f. 1969.

- KOBRAK, Christopher. National cultures and international competition: the experience of Schering AG, 1851-1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002.

- KOLB, Eberhard. Der Frieden von Versailles München: Beck. 2005.

- KORNFELD, Kurt. Kornfeld to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 15 Sep. 1923.

- KORNFELD, Kurt. Kornfeld to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 19 Apr. 1921.

- KORNFELD, Kurt. Kornfeld to Bischoff. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 1. R 64.983. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 11 Apr. 1921.

- KROPF, Simone P.; LACERDA, Aline L. de. Carlos Chagas, um cientista do Brasil Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz. 2009.

- KRÜGER, Peter. Versailles: deutsche Außenpolitik zwischen Revisionismus und Friedenssicherung. München: dtv. 1993.

- MANNWEILER, Erich. Geschichte des Instituts für Schiffs- und Tropenkrankheiten in Hamburg, 1900-1945 Keltern-Weiler: Goecke & Evers. (Abhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg, n.32). 1998.

- MEDIAVILLA, Víctor Herrero (Ed.). Archivo biográfico de España, Portugal e Iberoamérica. 10v. München: Saur. 1986-2005.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens to Hauff. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 15 Feb. 1932.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens, betr. lateinamerikanisches Studentenheim. File 1928-1929[M]. (Archiv des Bernhard-Nocht-Instituts für Tropenmedizin, Hamburg). 16 Nov. 1928.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens to Heilbron. R 64.680 (Vorträge des Professor Mühlens im Auslande, 1923-1926). (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 24 Mar. 1926.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens to Heilbron. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 8 Mar. 1926.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens to Nocht. File 1900-1920, part 2: 1911-1920[M]. (Archiv des Bernhard-Nocht-Instituts für Tropenmedizin, Hamburg). 17 May 1914.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens, betr. Krankenabteilung des Tropeninstituts. 352-8/9 (Bernhard-Nocht-Institut), 5b (Mühlens). (Staatsarchiv Hamburg). s.d.-a.

- MÜHLENS, Peter. Mühlens, Denkschrift über deutsch-russische medizinische Zeitschriften. 352-8/9 (Bernhard-Nocht-Institut), 23 (DRK-Hungerhilfe Rußland 1921-1922, Mühlens), v.1 (Berichte). (Staatsarchiv Hamburg). s.d.-b.

- MÜHLENS, Peter; WEYGANDT, Wilhelm; KIRSCHBAUM, Walter. Die Behandlung der Paralyse mit Malaria- und Recurrensfieber. Münchener medizinische Wochenschrift, München, v.67, n.29, p.831-833. 1920a.

- MÜHLENS, Peter; WEYGANDT, Wilhelm; KIRSCHBAUM, Walter. Tratamiento de la parálisis general progresiva con inoculaciones de malaria y fiebre recurrente. Revista Médica de Hamburgo, Berlin, v.1, n.4, p.80-84. 1920b.

- NEUBAUER, Hendrik. Black Star: 60 years of photojournalism. Köln: Könemann. 1997.

- PEISER, Friedrich. Peiser to Mühlens. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 4 Dec. 1933.

- PFEIFFER, Heinrich (Ed.). Hamburg im Spiegel der Welt Hamburg: Deutsche Beratungsstelle für kulturelle und wirtschaftliche Werbung. (Prismen: Blätter für Kultur- und Wirtschaftspropaganda, n.2: Sondernummer Hamburg). 1927.

- REVISTA MÉDICA... Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana, Leipzig, Berlin, v.1, n.1, p.1f. 1928.

- RINKE, Stefan. "Der letzte freie Kontinent": deutsche Lateinamerikapolitik im Zeichen transnationaler Beziehungen, 1918-1933. Stuttgart: Heinz. (Histoamericana, n.1). 1996.

- SÁ, Magali Romero; SILVA, André Felipe Cândido da. La Revista Médica de Hamburgo y la Revista Médica Germano-Ibero-Americana: diseminación de la Medicina Germánica en España y América Latina (1920-1933). Asclepio, Madrid, v.62, n.1, p.7-34. 2010.

- SÁ, Magali Romero et al. Medicine, science, and power: relations between France, Germany, and Brazil during 1919-1942. História, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.16, n.1, p.247-261. 2009.

- SCHÄDEL, Bernhard; BRAUER, Ludolph. Schädel, Brauer. Denkschrift Südamerika-Unternehmungen. 30 (Bildungswesen, kulturelle Angelegenheiten), N. 1. Nr.1 (Ausbau hamburgischer wissenschaftlicher Südamerika Unternehmungen, 1913). (Archiv der Handelskammer Hamburg). 15 Dec. 1913.

- SCHWALBE, Julius. Schwalbe to Auswärtiges Amt. Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). 12 Nov. 1924.

- SETTEKORN, Wolfgang. Die frühe Hamburger Iberoromanistik und der Krieg: andere Aspekte romanistischer Fachgeschichte. Iberoamericana, Frankfurt a.M., v.14, n.1(39), p.33-94. 1990.

- SILVA, André Felipe Cândido da. A trajetória científica de Henrique da Rocha Lima e as relações Brasil-Alemanha (1901-1956) Tese (Doutorado) - Casa de Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. 2011.

- SITZUNGSPROTOKOLL. Sitzungsprotokoll. 170 (Pharma), 4.4 (Reichsfachschaft Pharmazeutische Industrie/ "Reipha"), 4b. (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 28 June 1934.

- STAEHR, Christian. Spurensuche: ein Wissenschaftsverlag im Spiegel seiner Zeitschriften, 1886-1986. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme. 1986.

- STELLUNGNAHME... Stellungnahme Vox Médica Zeitschrift "Revista Médica de Hamburgo", Band 2. R 64.984. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). Jan. 1923.

- URBAN, Jens. Die lateinamerikanischen Studierenden an der Universität Hamburg, 1919-1970 Hamburg: Institut für Iberoamerika-Kunde. (Beiträge zur Lateinamerika-Forschung, n.5). 2000.

- VEREINIGUNG... Vereinigung der Freunde des Hamburger Tropeninstituts. Denkschrift Hamburger Tropeninstitut. File 1921-1923[V]. (Archiv des Bernhard-Nocht-Instituts für Tropenmedizin, Hamburg). Aug. 1921.

- VERLAG... Verlag Georg Thieme. R 67.877 d. (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts, Berlin). s.d.

- VERTRAGSENTWURF... Vertragsentwurf Revista 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 1928.

- WEISSER, Ursula. Das Städtische Krankenhaus als Modell moderner Forschungsorganisation: Drittmittelforschung am Eppendorfer Krankenhaus in Hamburg 1911-1934. In: Verein der Freunde und Förderer des Allgemeinen Krankenhauses St. Georg in Hamburg e. V. (Ed.). Allgemeines Krankenhaus St. Georg: Betrachtungen zur Krankenhausgeschichte in den Partnerstädten Hamburg und Dresden. Hamburg. p.6-16. 1992.

- WEISSER, Ursula (Ed.). 100 Jahre: Universitäts-Krankenhaus Eppendorf, 1889-1989. Tübingen: Attempto-Verlag. 1989.

- WULF, Stefan. Bernhard Nocht (1857-1945). In: Kopitzsch, Franklin; Brietzke, Dirk (Ed.). Hamburgische Biografie: Personenlexikon. v.5. Göttingen: Wallstein. p.276-278. 2010a.

- WULF, Stefan. Peter Mühlens (1874-1943). In: Kopitzsch, Franklin; Brietzke, Dirk (Ed.). Hamburgische Biografie: Personenlexikon. v.5. Göttingen: Wallstein. p.268-270. 2010b.

- WULF, Stefan. Jerusalem, Aleppo, Konstantinopel: der Hamburger Tropenmediziner Peter Mühlens im Osmanischen Reich am Vorabend und zu Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs. Münster: LIT. (Hamburger Studien zur Geschichte der Medizin, n.5). 2005.

- WULF, Stefan. Bernhard Nocht (1857-1945). In: Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Ed.). Neue Deutsche Biographie v.19. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p.305-307. 1999.

- WULF, Stefan. Peter Mühlens (1874-1943). In: Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Ed.). Neue Deutsche Biographie v.18. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p.285-286. 1997.

- WULF, Stefan. Das Hamburger Tropeninstitut 1919 bis 1945: auswärtige Kulturpolitik und Kolonialrevisionismus nach Versailles. Berlin; Hamburg: Reimer. (Hamburger Beiträge zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, n.9). 1994.

- WULF, Stefan; SCHMIEDEBACH, Heinz-Peter. Wahn und Malaria: Schnittpunkte und Grenzverwischungen zwischen Psychiatrie und Tropenmedizin in Hamburg (1900-1925). Manuscript. 2012.

- ZANDER, Paulo. Zander to Thieme Verlag. 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). 2 Nov. 1931.

- ZUSAMMENFASSUNG... Zusammenfassung der Cepha-Befragung betr. Revista Médica 170 (Pharma), 15 (Revista Médica). (Bayer-Archiv, Leverkusen). s.d.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

02 Apr 2013 -

Date of issue

Mar 2013

History

-

Received

Jan 2012 -

Accepted

Feb 2013