Abstract

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is less frequent in young individuals (≤ 45 years) than in older ones (> 45 years). Young AMI patients differ from older AMI patients in different ways. This article aims to assess the differences between young and older AMI patients. A search was made in the database of Cochrane Library, PubMed, BioMed Central and Embase, sence their establishment to December 2016, using the key words: risk factors, clinical characteristics, acute myocardial infarction and young. Meta-analysis was performed by using the Review Manager 5.3 software, pooled odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to assess the strength of differences. Eight studies with fairly quality, enrolling 13,358 patients in the analysis. Compared with older AMI patients, young AMI patients had a higher rate of smoking and obesity (OR = 2.71,95%CI:1.87 to 3.92; OR = 1.76,95%CI:1.13 to 2.74), higher rate of family history of coronary artery disease and alcohol consumption (OR = 2.36,95%CI:1.22 to 4.59; OR = 1.76,95%CI:1.04 to 2.97). Moreover, Young AMI patients had a lower rate of hypertension and diabetes mellitus (OR = 0.52,95%CI:0.37 to 0.73; OR = 0.58,95%CI:0.50 to 0.67). No significant differences were observed in hyperlipidemia, a subgroup data-analysis showed a higher total cholesterol, triglyceride lipase, and low-density lipoprotein levels (p < 0.05), and lower levels of high-density lipoprotein (p < 0.01) in young AMI patients. Smoking, family history of coronary artery disease, obesity and alcohol consumption are the most main risk factors of AMI among young individuals, and young AMI patients have better prognosis than older ones.

Keywords

Myocardial Infarction; Risk Factors; Aged; Review; Meta-Analysis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a global health problem that has reached epidemic proportions in both developed and developing countries.11 Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):448-57. Even though the rates of death caused by CVD have declined, yet the burden of disease remains high. Mortality data have showed that CVD accounted for almost 32.8% of all deaths, i.e., 1 of every 3 deaths was caused by CVD in the United States. CVD has become the leading cause of death in both developed and developing countries.22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002.,33 Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2746-53.

Acute myocardial infarction(AMI) is less frequent in young adults (≤ 45 years) than in older individuals (> 45 years) as it occurs in only 2% to 6% in the younger population.44 Garoufalis S, Kouvaras G, Vitsias G, Perdikouris K, Markatou P, Hatzisavas J, et al. Comparison of angiographic findings, risk factors, and long term follow-up between young and old patients with a history of myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998;6(1):75-80. In recent years, the rate of AMI in young adults has begun to rise. Studies showed that young AMI patients differed from older AMI patients in several ways, including risk factors, clinical characteristics, coronary angiographic characteristics and prognosis.55 Rubin JB, Borden WB. Coronary heart disease in young adults. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14(2):140-9. AMI in young individuals can cause death and disability in the prime of life, in addition to being an increasing economic burden for both the patients’ family and the government. Because of the potential of premature death and long-term disability in young AMI patients, clinical interest in young adults is increasing.66 Weinberger I, Rotenberg Z, Fuchs J, Sagy A, Friedmann J, Agmon J, et al. Myocardial infarction in young adults under 30 years: risk factors and clinical course. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10(1):9-15. Identifying the major risk factors for AMI in this group of young individuals is of vital significance to develop effective prevention strategies.

Young AMI patients have different clinical characteristics and pathophysiology when compared to older patients.77 Shiraishi J, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi S, Arihara M, Hadase M, Hyogo M, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in young Japanese adults. Circ J. 2005;69(12):1454-8. Previous studies reported that smoking, diabetes mellitus, family history of CAD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and obesity contribute to the set of main risk factors for AMI in young patients.77 Shiraishi J, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi S, Arihara M, Hadase M, Hyogo M, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in young Japanese adults. Circ J. 2005;69(12):1454-8.,88 Al-Khadra AH. Clinical profile of young patients with acute myocardial infarction in Saudi Arabia. Int J Cardiol. 2003;91(1):9-13. This article aimed to assess the differences in risk factors and clinical characteristics between young and older AMI patients.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

A search was made in the database of Cochrane Library, Pubmed, BioMed Central and Embase, since their establishment to December 2016. An experienced searcher used the key words: risk factors, clinical characteristics, young people and acute myocardial infarction, with the Boolean operators AND and OR. We searched for comparative studies of risk factors and clinical characteristics in myocardial infarction between young and older patients. The search was limited to observational studies on humans of the randomized controlled trial (RCT) type. For the meta-analysis, we only used articles published in English.

Study selection and extraction criterion

Most studies used an age cutoff of 40 to 45 years to define young patients diagnosed with AMI, thus we chose patients aged 45 or less as the limit for young AMI patients, while patients aged older than 45 years were defined as older AMI patients. We reviewed the list of identified articles and extracted data from the selected ones; subsequently we selected studies with abstracts suggesting they were relevant. Studies were eligible if: (1) the study design was a cohort or case-control study and all the studies were RCTs; (2) the study compared young AMI patients with older AMI patients; (3) the study reported risk factors or clinical characteristics of young AMI patients, including any ethnicities and nationalities. Initial abstract screening excluded non-relevant and non-original studies, then full-text review excluded ineligible studies as follows: (1) studies without comparison between young and older AMI patients; (2) age-definition for the young AMI patients was older than 45 years or less than 44 years; (3) studies with abstract only or studies without full-text available; (4) studies lacking complete important information or those with no reply from the contact author; (5) smoking patients were defined as current smokers, and former smokers were excluded.

For each study, we recorded the following information: first author, year of publication, number of cases of young and older AMI patients, risk factors and clinical characteristics. Risk factors of AMI were: smoking, Hypertension, family history of CAD, obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, alcohol consumption. We defined Hyperlipidemia as a condition with elevated serum lipid levels, including high levels of total cholesterol (TC) or elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), or high triglycerides (TG). To better assess the effect of serum lipids on myocardial infarction in young people, we also compared high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels in young and older AMI patients. Clinical characteristics were: chest pain, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) value (%), all-cause mortality and outcome of coronary angiography (CA).

Literature quality assessment

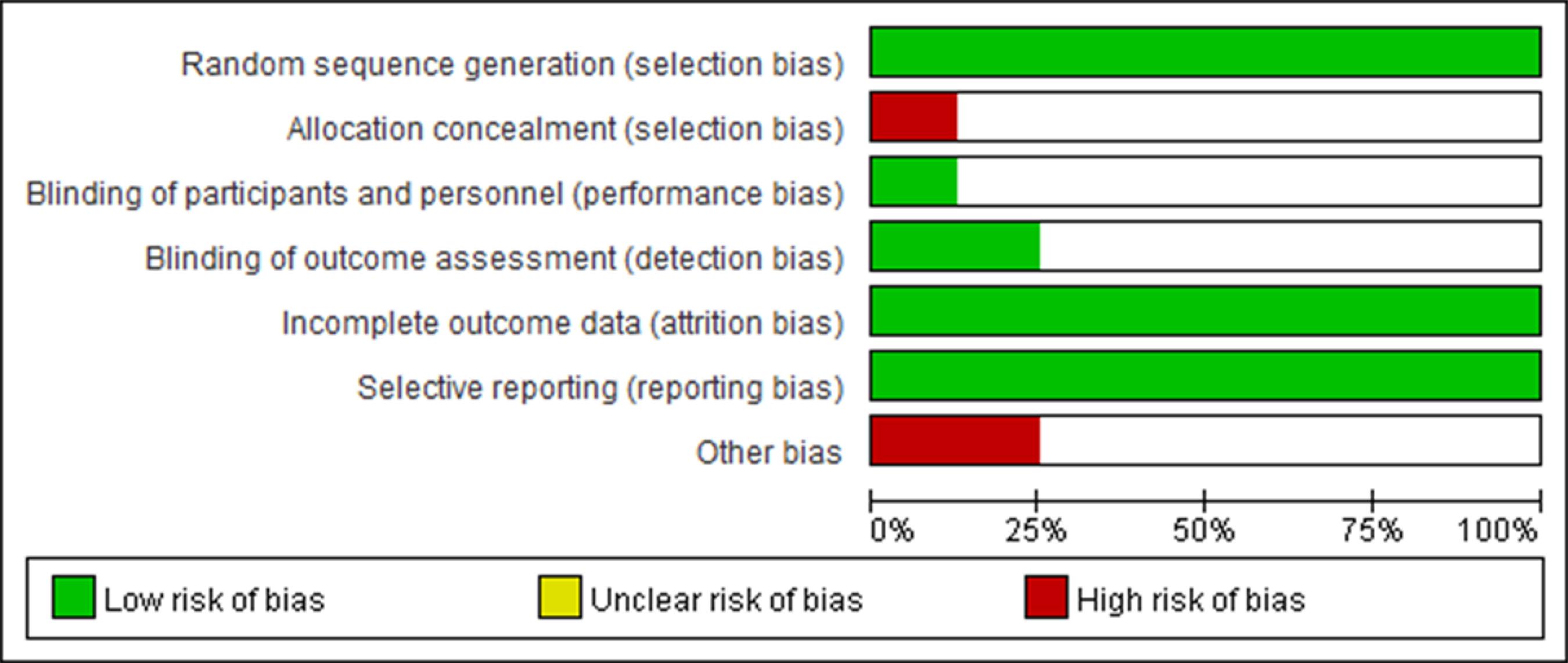

We assessed the literature quality using the standard bias risk assessment of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0,9 of which scale consists of: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, complement of outcome data, incomplete outcome data, other bias resource. The risk bias of each study uses “High risk”, “Low risk” and “Unclear risk” for each scale.

Statistical analysis

We used the Review Manager 5.3.0 software for comprehensive meta-analysis. We used the X22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. test and I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. statistics (ranging from 0% to 100%) to estimate the percentage of total variation across studies. When p ≥ 0.1 and I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. valued 50% or less, the data showed low heterogeneity and we used the fixed-effect model to pool results across studies. When p < 0.1 and I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. values were higher than 50%, the data showed high heterogeneity and the random-effect model was used to pool the results from studies, and a subgroup data analysis was also performed. When an extremely high heterogeneity influenced the determination of its resource, the description analysis was used as presentation. For each risk factor compared between young and older AMI patients, we calculated the adjusted odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) in each study. Funnel plots were used to estimate publication bias. All P values were two-tailed, and a p value < 0.5 was considered significant.

Results

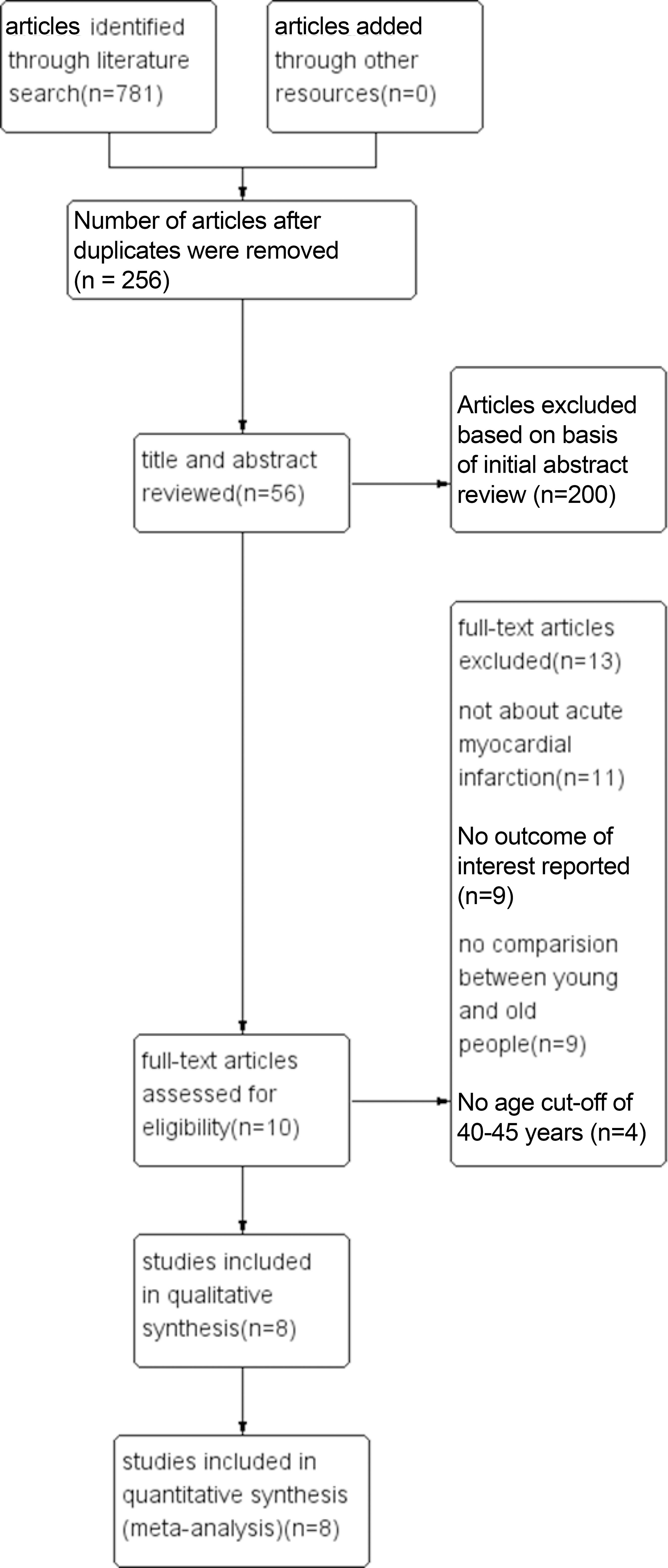

We retrieved 781 citations from the initial search and excluded 525 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria; subsequently, we excluded 200 articles based on the initial abstract review. Afterwards, we excluded 46 articles through full-text review, and finally 8 eligible studies1010 Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.

11 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.

12 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.

13 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.

14 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.

15 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8.

16 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8.-1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. were selected for the meta-analysis (figure 1). The assessed 13,358 patients included 1,122 young AMI patients and 4,766 older AMI patients. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of these selected studies.

Bias risk assessment

According to the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Controlled Trials, 8 selected studies had different bias risks. All eight studies referred to “randomized controlled trial”, but no detailed description was mentioned in these studies. All 8 studies reported the outcome completely without selective reporting. None of the studies reported blinding and allocation concealment. One study1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11. had a selection bias, and two studies1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.,1515 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8. might have other bias. According to bias risk graph (figure 2) and bias risk summary (figure 3), Yunyun et al.1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179., Chua et al.1515 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8. and Anderson et al.1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11. had high risk, while the other studies1010 Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.,1111 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.,1414 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.,1616 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8.,1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. had a relatively low risk.

Meta-analysis outcome

Risk factors

Eight studies10-17 compared smoking (figure 4) in young and older AMI patients. The studies showed high heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002.=85%), thus the random-effect model was used to perform the statistical analysis. Significant differences were observed in the outcome (OR = 2.71, 95%CI: 1.87 to 3.92). The rate of smoking in young AMI patients was much higher than that in older AMI patients (71.51% vs 40.43%). Six studies1010 Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.

11 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.-1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.,1414 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.,1616 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8.,1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. compared a family history of CAD in young and older AMI patients (figure 4), and the studies showed high heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 89%), and thus the random-effect model was used to perform the analysis. Significant differences were observed between the two groups (OR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.22 to 4.59) and young AMI patients had a higher rate of family history of CAD than older AMI patients (43.48% vs 28.27%).

Forest plot showing results of the comparison between young and older AMI patients for (A) risk factor of smoking; (B) risk factor of family history of CAD; (C) risk factor of obesity; (D) risk factor of alcohol consumption; (E) risk factor of hypertension; (F) risk factor of diabetes mellitus; (G) risk factor of hyperlipidemia.

Five studies1010 Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.,1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.

14 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.-1515 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8.,1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. compared obesity (figure 4) between young and older AMI patients. The studies showed heterogeneity (p = 0.0002, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 82%), and so the random-effect model was used to perform the analysis. There were significant differences in the outcome (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.13 to 2.74), and the rate of obesity in young AMI patients was higher than that in older AMI patients (36.21%vs 31.95%). Only three studies1111 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.,1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.,1616 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8. compared alcohol consumption in young and older AMI patients (figure 4). The studies showed heterogeneity (p = 0.10, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 56%), and thus random-effect model was used to perform the analysis. Significant differences were observed in the outcome (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.97); young AMI patients showed a much higher rate of alcohol consumption than older AMI patients (34.16% vs 24.97%).

Eight studies10-17 compared hypertension in the two groups (figure 4). The studies showed heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 83%), and thus random-effect model we was used to perform the analysis. Significant differences were observed in the outcome (OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.37 to 0.73), the rate of hypertension in young AMI patients was lower than that in older AMI patients (34.48% vs 51.2%). Eight studies1010 Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.

11 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.

12 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.

13 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.

14 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.

15 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8.

16 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8.-1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. compared diabetes mellitus between the two groups; low heterogeneity was observed in the studies (p = 0.52, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 0%), and thus the fixed-effect model was used to perform the statistical analysis. Significant differences were observed between the two groups (OR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.67), and young AMI patients had a lower diabetes mellitus incidence than older AMI patients (17.02% vs. 24.9%).

Four studies1111 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.,1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.

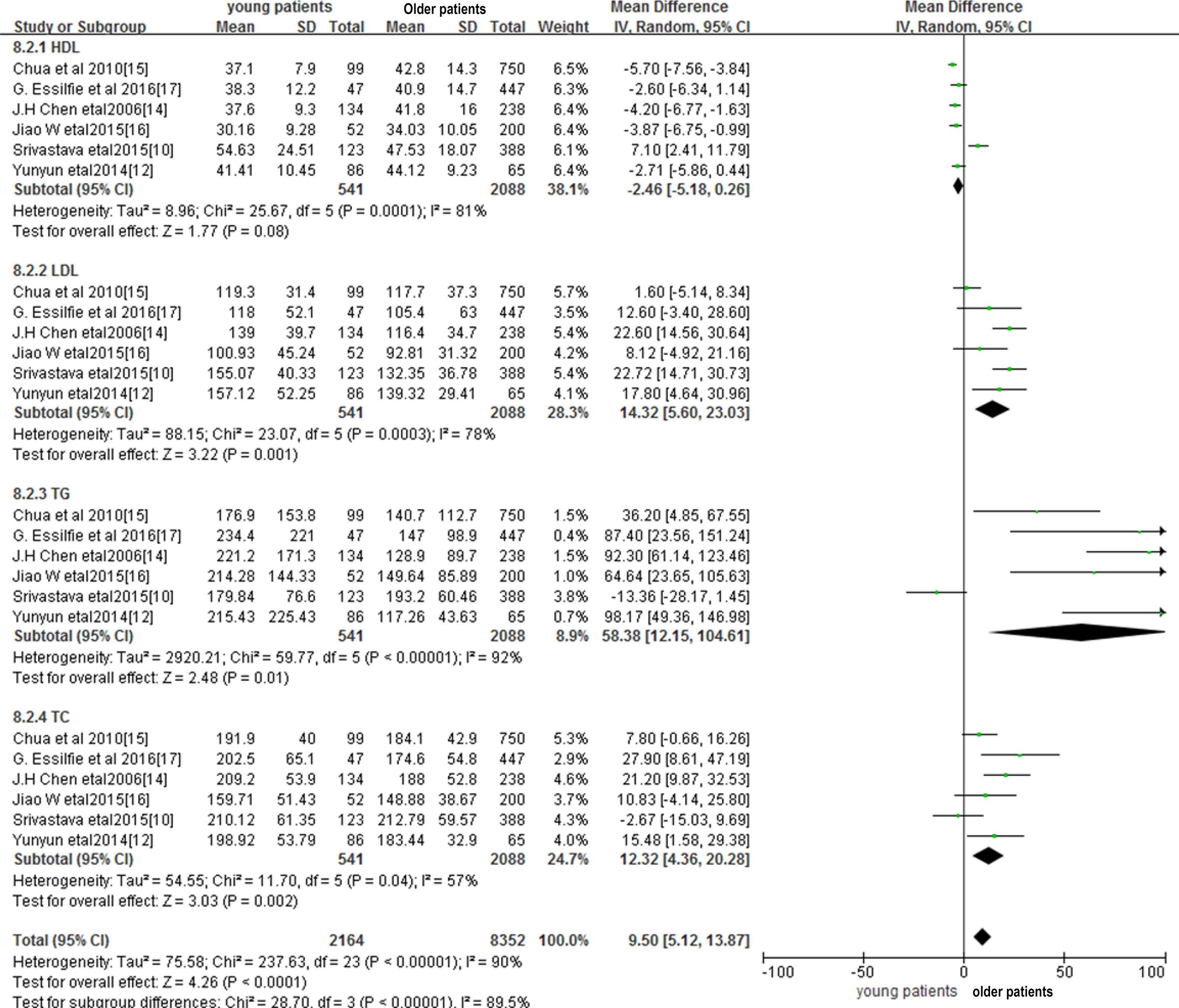

14 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.-1515 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8. compared hyperlipidemia (figure 4) between young and older AMI patients. The studies showed high heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 94%) and, therefore, the random-effect model was used to perform the analysis. The outcome showed no significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.45). Then, we performed a subgroup data analysis (figure 5), comparing serum levels of TC, LDL, TG and HDL between the two groups. The random-effect model was used to perform the analysis. We found that young AMI patients had comparatively higher levels of serum TG (p = 0.01), LDL (p = 0.001), TC (p = 0.002) and lower levels of serum HDL (p = 0.008) than older AMI patients.

Subgroup of hyperlipidemia showing results of comparison between young and older AMI patients regarding serum levels of HDL, LDL, TG, TC.

Clinical characteristics

Three studies1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.,1414 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.,1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. compared LVEF values in young and older AMI patients (figure 6) and low heterogeneity was observed regarding the outcome (p = 0.43, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 0%) and thus, the fixed-effect model was used to perform the analysis. No significant differences were observed in the analysis (p = 0.07), as there were no obvious differences between young and older AMI patients regarding LVEF values. Three studies1010 Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.,1414 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.,1515 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8. reported chest pain in AMI patients (figure 6), and heterogeneity was observed regarding the outcome (p = 0.01, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 77%). Thus, the random-effect model was used to perform the analysis. No significant differences were found between the two groups (p = 0.13). There were no obvious differences regarding the incidence of chest pain between young and older AMI patients.

Forest plot showing results of comparison between young and older AMI patients for (a) LVEF values; (b) chest pain; (c) all-cause mortality.

Three studies1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.,1515 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8.,1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. reported all-cause mortality in AMI patients (figure 6), with low heterogeneity being observed in the studies (p = 0.65, I22 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002. = 0%); thus, the fixed-effect model was used to perform this analysis. Significant differences were observed in the analysis (OR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.12). When compared with older AMI patients, young AMI patients had obviously a lower rate of all-cause mortality (6.43% vs 41.57%).

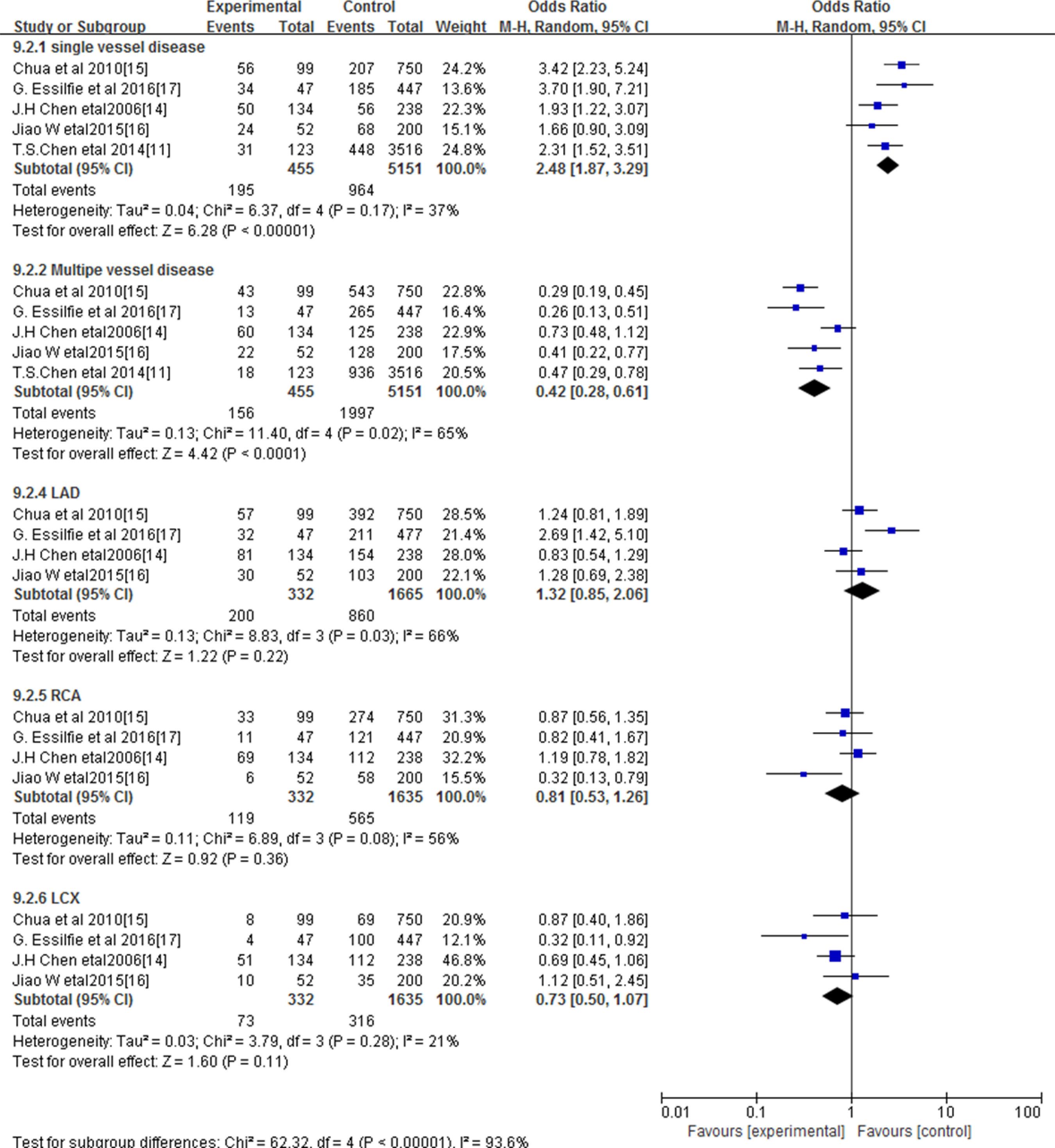

Five studies1111 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.,1414 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.

15 Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8.

16 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8.-1717 Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4. compared the outcome of coronary angiography (CA) between young and older AMI patients. Significant differences were observed between the two groups (figure 7). Compared with older AMI patients, single-vessel disease was more prevalent in young AMI patients (OR = 2.48, 95% CI: 1.87 to 3.29). A total of 42.86% of young AMI patients had single-vessel disease, which was more prevalent than that in older AMI patients (18.71%). While multiple-vessel disease was more common in older AMI patients (OR = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.61), with 38.77% of older AMI patients exhibiting multiple-vessel disease, which was a higher incidence than that in young AMI patients (34.28%). Moreover, we compared the coronary artery disease location in young and older AMI patients, which included left Anterior descending artery (LAD), right coronary artery (RCA) and left circumflex artery (CX). No significant differences were observed in the coronary artery disease location of LAD (p = 0.22), RCA (p = 0.36) and CX arteries (p = 0.11) between young and older AMI patients.

Discussion

The incidence of AMI in young individuals was once as low as 2-6%,44 Garoufalis S, Kouvaras G, Vitsias G, Perdikouris K, Markatou P, Hatzisavas J, et al. Comparison of angiographic findings, risk factors, and long term follow-up between young and old patients with a history of myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998;6(1):75-80. but it has been increasingly rising.1414 Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22. Young AMI patients differed from older AMI patients in several ways including risk factors, clinical, coronary angiographic characteristics and prognosis.88 Al-Khadra AH. Clinical profile of young patients with acute myocardial infarction in Saudi Arabia. Int J Cardiol. 2003;91(1):9-13. Yunyun et al.1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179. said that AMI tend to occur suddenly in young patients; most young people do not experience a warning before its onset, and the first occurrence often leads to a large infarction size.1818 Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DJ. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-60.,2020 Jennings RB, Wagner GS. Roles of collateral arterial flow and ischemic preconditioning in protection of acutely ischemic myocardium. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47(4):491-9.. Zimmerman et al.,2121 Zimmerman FH, Cameron A, Fisher LD, Ng G. Myocardial infarction in young adults: angiographic characterization, risk factors and prognosis (Coronary Artery Surgery Study Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(3):654-61. reported that males show an absolute predominance among young AMI patients; however, there is a tendency for the incidence of myocardial infarction to be equal in both sexes with increasing age. In our meta-analysis, male patients were predominant among young AMI patients, ranging from 64.7% to 94.8%, while the proportion of male patients seemed to decrease in older AMI patients.

Several studies reported that chest pain is the most frequent symptom in young AMI patients,2222 Barbash GI, White HD, Modan M, Diaz R, Hampton JR, Heikkila J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: the role of smoking. The Investigators of the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase mortality trial. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):313-6. while “silent” AMI tends to be more frequent in older patients.2323 Schoenenberger AW, Radovanovic D, Stauffer JC, Windecker S, Urban P, Niedermaier G, et al; AMIS Plus Investigators. Acute coronary syndromes in young patients: presentation, treatment and outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148(3):300-4. Our study revealed that there was no significant difference in the rate of chest pain between young and older patients with AMI. Data from the meta-analysis showed that the all-cause mortality rate of young individuals after AMI is significantly lower than that of older people, which is in line with previous studies.2424 Morillas P, Bertomeu V, Pabón P, Ancillo P, Bermejo J, Fernández C, et al. Characteristics and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in young patients: the PRIAMHO II study. Cardiology. 2007;107(4):217-25.

25 Doughty M, Mehta R, Bruckman D, Das S, Karavite D, Tsai T, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young--The University of Michigan experience. Am Heart J. 2002;143(1):56-62.-2626 Jing M, Gao F, Chen Q, de Carvalho LP, Sim LL, Koh TH, et al. Comparison of long-term mortality of patients aged = 40 versus > 40 years with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(3):319-25. Although young AMI patients had better long-term survival than older AMI patients, they fared worse than their age-matched contemporaries in the general population.2727 Poole-Wilson P. Preventing cardiovascular disease worldwide: whose task and WHO's task? Clin Med (Lond). 2005;5(4):379-84.

Our data analysis suggested that single-vessel coronary artery disease was more common in young AMI patients than in older ones, while multiple-vessel coronary artery disease was less prevalent in young AMI patients. That might also explain why young individuals have a better prognosis than older ones after AMI. Previous studies reported that among young AMI patients with general CA, single-vessel disease was the most prevalent, with the lesion most commonly located in the LAD.2828 Huang J, Qian HY, Li ZZ, Zhang JM. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction younger than 35 years with those older than 65 years. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346(1):52-5.,2929 Wong CP, Loh SY, Loh KK, Ong PJ, Foo D, Ho HH. Acute myocardial infarction:Clinical features and outcomes in young adults in Singapore. World J Cardiol. 2012;4(6):206-10. However, our data showed no obvious differences in the location of coronary artery lesion between the two groups when comparing the lesion location in the LAD, RCA or CX arteries.

Our analysis showed that the rate of smoking in young AMI patients was much higher than that in older ones (71.51% vs 40.43%), which is consistent with previous studies.2020 Jennings RB, Wagner GS. Roles of collateral arterial flow and ischemic preconditioning in protection of acutely ischemic myocardium. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47(4):491-9.,3030 Barbash GI, White HD, Modan M, Diaz R, Hampton JR, Heikkila J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: the role of smoking. The Investigators of the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase mortality trial. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):313-6. Young individuals are more likely than older people to be smokers, and ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients are getting increasingly younger, which is accompanied by an increasing proportion of young smokers.3131 Qian G, Zhou Y, Liu HB, Chen YD. Clinical profile and long-term prognostic factors of a young Chinese Han population (p 40 years) having ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2015;31(5):390-7. Smoking is actually the most important risk factor for AMI in young individuals. Previous studies suggested that in young AMI patients, coronary artery spasm might lead to temporary occlusion of the vessel or thrombus, or a combination of them, as a result of smoking.3232 Williams MJ, Restieaux NJ, Low CJ. Myocardial infarction in young people with normal coronary arteries. Heart.1998;79(2):191-4. Smoke cessation could reduce the risk for AMI compared with current smoking, especially in young people.3333 Larsen GK, Seth M, Gurm HS. The ongoing importance of smoking as a powerful risk factor for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1261-2. Additionally, the benefit of quitting is associated with the number of smoked cigarettes,3434 Choudhury L, Marsh JD. Myocardial infarction in young patients. Am J Med. 1999;107(3):254-61. thus identifying cigarette smoking as a major risk factor for young people in AMI is of vital significance. Moreover, creating an awareness of the advantages of smoking cessation may be effective in this group of people to prevent AMI.

A positive family history of CAD has often been reported as being another major risk factor for AMI among young patients.3535 Doughty M, Mehta R, Bruckman D, Das S, Karavite D, Tsai T, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: The University of Michigan experience. Am Heart J. 2002;143(1):56-62. Our analysis showed that 43.48% of young AMI patients has a family history of CAD, which is higher than that in older AMI patients (28.27%). Family history of CAD is certainly a major risk factor for young AMI patients. Patients with a family history of CAD have more severe disease progression and more lipid metabolism disorders than those without such a history3636 Gaeta G, De Michele M, Cuomo S, Guarini P, Foglia MC, Bond MG, et al. Arterial abnormalities in the offspring of patients with premature myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):840-6. and are more likely to have insulin resistance and more likely to be obese, possibly resulting from hereditary factors.3737 Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(23):1650-6.

The analysis suggested that young patients had a higher rate of obesity compared with older patients with AMI (36.58% vs 31.93%). Obesity can double the prevalence of cardiovascular disease.3838 Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Casstelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation.1983;67(5):968-73. Kragelund et al.3939 Kragelund C, Hassager C, Hildebrandt P, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L; TRACE study group. Impact of obesity on long-term prognosis following acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98(1):123-31. said that abdominal obesity appears to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in AMI patients. The changes in life and eating habits, and adopting unhealthy habits such as eating fast food or high-fat food can lead to dyslipidemia and abdominal obesity in many young individuals. Previous studies reported that an unhealthy diet, rich in carbohydrates and low in fruits and vegetables are a major risk factor for CVD.4040 Chen Y, McClintock TR, Segers S, Parvez F, Islam T, Ahmed A, et al. Prospective investigation of major dietary patterns and risk of cardiovascular mortality in Bangladesh. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(4):1495-501. Several studies reported that young people tend to consume more red meat with a high fat content and a significantly lower amount of fruits and vegetables compared to the older group.4141 Karim MA, Majumder AA, Islam KQ, Alam MB, Paul ML, Islam MS, et al. Risk factors and in-hospital outcome of acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in young Bangladeshi adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:73.,4242 Malmberg K, Båvenholm P, Hamsten A. Clinical and biochemical factors associated with prognosis after myocardial infarction at a young age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24(3):592-9. Effective interventions, which include a healthy diet and life-style, as well as moderate exercise practice to control body weight may help prevent AMI in young individuals.

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension are important risk factors for CAD and are more likely to be associated with older myocardial infarction patients.4343 Soeiro Ade M, Fernandes FL, Soeiro MC, Serrano Jr CV, Oliveira Jr MT. Clinical characteristics and long-term progression of young patients with acute coronary syndrome in Brazil. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2015;13(3):370-5. Our analysis showed that compared with older AMI patients, young AMI patients had a lower rate of hypertension (34.48% vs. 51.2%) and diabetes mellitus (17.02% vs. 24.9%), which is consistent with other studies.4444 Klein LW, Agarwal JB, Herlich MB, Leary TM, Helfant RH. Prognosis of symptomatic coronary artery disease in young adults aged 40 years or less. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(16):1269-72.,4545 Vincent GM, Anderson JL, Marshall HW. Coronary spasm producing coronary thrombosis and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(4):220-3. Anderson et al.1313 Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11. said that even though hypertension is more prevalent in older AMI patients, the hazard associated with this risk factor is higher in the young patients. Thus, the early diagnosis of hypertension and effective medical intervention may reduce AMI in young people. Many studies reported that non-diabetic AMI patients have increased blood sugar, compromised glucose tolerance and insulin resistance.4646 Tandjung K, van Houwelingen KG, Jansen H, Basalus MW, Sen H, Löwik MM, et al. Comparison of frequency of periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus to those with previously unknown but elevated glycated hemoglobin levels (from the TWENTE trial). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(11):1561-7.,4747 Lazzeri C, Valente S, Chiostri M, Picariello C, Attanà P, Gensini GF. Glycated hemoglobin in ST-elevation myocardial infarction without previously known diabetes: Its short and long term prognostic role. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;95(1):e14-6. Yunyun et al.,1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179. found that many young patients had a higher baseline fasting blood sugar and HbA1c levels, suggesting that a higher proportion of young AMI patients had undetectable diabetes or pre-diabetes. Yunyun et al1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179. also found that the HbA1c level was an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction in young patients. So, the early identification of young people with diabetes or pre-diabetes and early effective medical intervention might help prevent AMI in young individuals.

In the present study, no significant differences were observed regarding hyperlipidemia between young and older AMI patients. Hyperlipidemia, especially high serum LDL levels, have been regarded as a major risk factor in patients with AMI, and lowering LDL levels has been a main target in medical treatment. HDL is often accepted as a protective factor to prevent the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. However, low HDL levels have drawn more attention in AMI.4848 Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Targeting residual cardiovascular risk: raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Heart. 2008;94:706-14. A study reported that low HDL was associated with significantly higher risk of in-hospital mortality in STEMI.4949 Ji MS, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Hong TJ, et al; Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Investigators. Impact of low level of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol sampled in overnight fasting state on the clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction(difference between ST-segment and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction). J Cardiol. 2015;65(1):63-70. Our study revealed that young AMI patients had higher levels of serum TG, LDL, TC and lower levels of serum HDL, compared with older AMI patients. Moreover, the prevalence of undiagnosed dyslipidemia and borderline levels of cholesterol in young people were really high. Data have suggested that the prevalence of undiagnosed dyslipidemia in young people was 16.8%, which was higher than the diagnosed group.5050 Najafipour H, Shokoohi M, Yousefzadeh G, Azimzadeh BS, Kashanian GM, Bagheri MM, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and its association with other coronary artery disease risk factorsamong urban population in Southeast of Iran: results of the Kerman coronary artery disease risk factors study (KERCADRS). J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2016 Oct 21;15:49. Thus, these young people may have fewer coronary collaterals, which might cause severe acute myocardial infarction in this group of young individuals. Identifying hyperlipidemia at a younger age, while paying early attention to serum HDL levels, lipid profile control and distal protection in young individuals can prevent AMI in this population.

In our analysis, only three studies1111 Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.,1212 Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.,1616 Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8. compared the risk factor of alcohol consumption. Our data showed that young AMI patients had higher rates of alcohol consumption than older AMI patients. Previous studies showed that alcohol consumption is directly associated with hyperuricemia,5151 Nakamura K, Sakurai M, Miura K, Morikawa Y, Yoshita K, Ishizaki M, et al. Alcohol intake and the risk of hyperuricaemia: a 6-year prospective study in Japanese men. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22(11):989-96. which is associated with CAD severity5252 Ehsan Qureshi A, Hameed S, Noeman A. Relationship of serum uric acid level and angiographic severity of coronary artery disease in male patients with acute coronary syndrome. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(5):1137-41. and the amount of alcohol consumed is associated with AMI.5353 Marques-Vidal P, Montaye M, Arveiler D, Evans A, Bingham A, Ruidavets JB, et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease: differential effects in France and Northern Ireland. The PRIME study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11(4):336-43. Heavy alcohol consumption tended to be associated with an increasing risk of heart failure, cardiac arrest/sudden death and ischemic attack after CAD.5454 Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E. Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ. 2017;356:j909. Although moderate levels of alcohol consumption are associated with a lower risk of morbidity and mortality from CAD, young individuals tend to have an excessive alcohol intake. Thus, making young individuals aware of the risk of alcohol consumption and encourage moderate alcohol intake might help prevent acute coronary syndrome.

Conclusion

The meta-analysis showed that there were differences in risk factors between young and older AMI patients. Smoking, family history of CAD, obesity and alcohol consumption are the main risk factors in young AMI patients, with smoking being the most important one for young individuals with AMI. Young individuals tend to have a better prognosis than older ones with AMI and have more single-vessel coronary artery disease than older AMI patients. Even though there is no difference in hyperlipidemia between young and older AMI patients, young AMI patients had higher levels of serum TG, LDL, TC levels and lower serum HDL levels than older AMI patients. According to our analysis, there were no obvious differences regarding chest pain and LVEF values between young and older AMI patients. Thus, making young individuals aware of these risk factors and their early detection, as well as effective intervention may help prevent acute myocardial infarction in young people.

-

Sources of FundingThere were no external funding sources for this study.

-

Study AssociationsThis study is not associated with any thesis or dissertation work.

-

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

-

1Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):448-57.

-

2Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2012 update:a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012;125(22):e1002.

-

3Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2746-53.

-

4Garoufalis S, Kouvaras G, Vitsias G, Perdikouris K, Markatou P, Hatzisavas J, et al. Comparison of angiographic findings, risk factors, and long term follow-up between young and old patients with a history of myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998;6(1):75-80.

-

5Rubin JB, Borden WB. Coronary heart disease in young adults. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14(2):140-9.

-

6Weinberger I, Rotenberg Z, Fuchs J, Sagy A, Friedmann J, Agmon J, et al. Myocardial infarction in young adults under 30 years: risk factors and clinical course. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10(1):9-15.

-

7Shiraishi J, Kohno Y, Yamaguchi S, Arihara M, Hadase M, Hyogo M, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in young Japanese adults. Circ J. 2005;69(12):1454-8.

-

8Al-Khadra AH. Clinical profile of young patients with acute myocardial infarction in Saudi Arabia. Int J Cardiol. 2003;91(1):9-13.

-

9Higgins JPT, Green S. (Editors). Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. [Cited in 2017 Jan 10]. Avalilable from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook

» https://training.cochrane.org/handbook -

10Srivastava R, Singh P, Verma A, Tiwari S. Comparison of acute myocardial infarction risk factors in young and elderly patients- a clinico-epidemiology study. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2015;6(3):479-85.

-

11Chen TS, Incani A, Butler TC, Poon K, Fu J, Savage M, et al. The demographic profile of Young patients (< 45 years-old) with acute coronary syndromes in Queensland. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):49-55.

-

12Yunyun W, Tong L, Yingwu L, Bojiang L, Yu W, Xiaomin H, et al. Analysis of risk factors of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014 Dec 9;14:179.

-

13Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Velazquez EV, et al. High-risk myocardial infarction in the young: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):706-11.

-

14Chen JH, Huang HH, Yen DH, Wu YL, Wang LM, Lee CH, et al. Different clinical presentations in chinese people with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(11):517-22.

-

15Chua SK, Hung HF, Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Chiu CZ, Chang CM, et al. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young patients: 15 years of experience in a single center. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(3):140-8.

-

16Wang J, Liu ZQ, He PY, Yang YC, Zhang L, Muhuyati. Analysis of the risk factors and characteristics of coronary artery disease of Han, Uygur and Kazak patients with acute myocardial infarction in Xinjiang district. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2831-8.

-

17Essilfie G, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Platt K, Kobayashi R, Mehra A, et al. Association of elevated triglycerides and acute myocardial infarction in young Hispanics. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(8):510-4.

-

18Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DJ. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-60.

-

19D'Ascenzo F, Moretti C, Omedè P, Cerrato E, Cavallero E, Er F, et al. Cardiac remote ischaemic preconditioning reduces periprocedural myocardial infarction for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. EuroIntervention. 2014;9(12):1463-71.

-

20Jennings RB, Wagner GS. Roles of collateral arterial flow and ischemic preconditioning in protection of acutely ischemic myocardium. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47(4):491-9.

-

21Zimmerman FH, Cameron A, Fisher LD, Ng G. Myocardial infarction in young adults: angiographic characterization, risk factors and prognosis (Coronary Artery Surgery Study Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(3):654-61.

-

22Barbash GI, White HD, Modan M, Diaz R, Hampton JR, Heikkila J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: the role of smoking. The Investigators of the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase mortality trial. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):313-6.

-

23Schoenenberger AW, Radovanovic D, Stauffer JC, Windecker S, Urban P, Niedermaier G, et al; AMIS Plus Investigators. Acute coronary syndromes in young patients: presentation, treatment and outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148(3):300-4.

-

24Morillas P, Bertomeu V, Pabón P, Ancillo P, Bermejo J, Fernández C, et al. Characteristics and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in young patients: the PRIAMHO II study. Cardiology. 2007;107(4):217-25.

-

25Doughty M, Mehta R, Bruckman D, Das S, Karavite D, Tsai T, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young--The University of Michigan experience. Am Heart J. 2002;143(1):56-62.

-

26Jing M, Gao F, Chen Q, de Carvalho LP, Sim LL, Koh TH, et al. Comparison of long-term mortality of patients aged = 40 versus > 40 years with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(3):319-25.

-

27Poole-Wilson P. Preventing cardiovascular disease worldwide: whose task and WHO's task? Clin Med (Lond). 2005;5(4):379-84.

-

28Huang J, Qian HY, Li ZZ, Zhang JM. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction younger than 35 years with those older than 65 years. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346(1):52-5.

-

29Wong CP, Loh SY, Loh KK, Ong PJ, Foo D, Ho HH. Acute myocardial infarction:Clinical features and outcomes in young adults in Singapore. World J Cardiol. 2012;4(6):206-10.

-

30Barbash GI, White HD, Modan M, Diaz R, Hampton JR, Heikkila J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: the role of smoking. The Investigators of the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase mortality trial. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):313-6.

-

31Qian G, Zhou Y, Liu HB, Chen YD. Clinical profile and long-term prognostic factors of a young Chinese Han population (p 40 years) having ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2015;31(5):390-7.

-

32Williams MJ, Restieaux NJ, Low CJ. Myocardial infarction in young people with normal coronary arteries. Heart.1998;79(2):191-4.

-

33Larsen GK, Seth M, Gurm HS. The ongoing importance of smoking as a powerful risk factor for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in young patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1261-2.

-

34Choudhury L, Marsh JD. Myocardial infarction in young patients. Am J Med. 1999;107(3):254-61.

-

35Doughty M, Mehta R, Bruckman D, Das S, Karavite D, Tsai T, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: The University of Michigan experience. Am Heart J. 2002;143(1):56-62.

-

36Gaeta G, De Michele M, Cuomo S, Guarini P, Foglia MC, Bond MG, et al. Arterial abnormalities in the offspring of patients with premature myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):840-6.

-

37Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(23):1650-6.

-

38Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Casstelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation.1983;67(5):968-73.

-

39Kragelund C, Hassager C, Hildebrandt P, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L; TRACE study group. Impact of obesity on long-term prognosis following acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98(1):123-31.

-

40Chen Y, McClintock TR, Segers S, Parvez F, Islam T, Ahmed A, et al. Prospective investigation of major dietary patterns and risk of cardiovascular mortality in Bangladesh. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(4):1495-501.

-

41Karim MA, Majumder AA, Islam KQ, Alam MB, Paul ML, Islam MS, et al. Risk factors and in-hospital outcome of acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in young Bangladeshi adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:73.

-

42Malmberg K, Båvenholm P, Hamsten A. Clinical and biochemical factors associated with prognosis after myocardial infarction at a young age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24(3):592-9.

-

43Soeiro Ade M, Fernandes FL, Soeiro MC, Serrano Jr CV, Oliveira Jr MT. Clinical characteristics and long-term progression of young patients with acute coronary syndrome in Brazil. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2015;13(3):370-5.

-

44Klein LW, Agarwal JB, Herlich MB, Leary TM, Helfant RH. Prognosis of symptomatic coronary artery disease in young adults aged 40 years or less. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(16):1269-72.

-

45Vincent GM, Anderson JL, Marshall HW. Coronary spasm producing coronary thrombosis and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(4):220-3.

-

46Tandjung K, van Houwelingen KG, Jansen H, Basalus MW, Sen H, Löwik MM, et al. Comparison of frequency of periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus to those with previously unknown but elevated glycated hemoglobin levels (from the TWENTE trial). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(11):1561-7.

-

47Lazzeri C, Valente S, Chiostri M, Picariello C, Attanà P, Gensini GF. Glycated hemoglobin in ST-elevation myocardial infarction without previously known diabetes: Its short and long term prognostic role. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;95(1):e14-6.

-

48Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Targeting residual cardiovascular risk: raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Heart. 2008;94:706-14.

-

49Ji MS, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Hong TJ, et al; Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Investigators. Impact of low level of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol sampled in overnight fasting state on the clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction(difference between ST-segment and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction). J Cardiol. 2015;65(1):63-70.

-

50Najafipour H, Shokoohi M, Yousefzadeh G, Azimzadeh BS, Kashanian GM, Bagheri MM, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and its association with other coronary artery disease risk factorsamong urban population in Southeast of Iran: results of the Kerman coronary artery disease risk factors study (KERCADRS). J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2016 Oct 21;15:49.

-

51Nakamura K, Sakurai M, Miura K, Morikawa Y, Yoshita K, Ishizaki M, et al. Alcohol intake and the risk of hyperuricaemia: a 6-year prospective study in Japanese men. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22(11):989-96.

-

52Ehsan Qureshi A, Hameed S, Noeman A. Relationship of serum uric acid level and angiographic severity of coronary artery disease in male patients with acute coronary syndrome. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(5):1137-41.

-

53Marques-Vidal P, Montaye M, Arveiler D, Evans A, Bingham A, Ruidavets JB, et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease: differential effects in France and Northern Ireland. The PRIME study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11(4):336-43.

-

54Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E. Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ. 2017;356:j909.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

18 Feb 2019 -

Date of issue

Mar-Apr 2019

History

-

Received

22 July 2017 -

Reviewed

23 Jan 2018 -

Accepted

3 Mar 2018