Abstracts

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the liver, occurring in all age groups, and more frequently in adults. The vast majority of hemangiomas are small, asymptomatic, and are incidentally discovered. Larger lesions may eventually produce symptoms. The sonographic aspect of these tumors varies, the lesions being typically small, well defined and hyperechoic. In this study the authors review clinical and sonographic features of hemangiomas, highlighting the clinical significance of such features to be taken into consideration in the treatment of affected patients.

Hemangioma; Liver; Ultrasound

Os hemangiomas são os tumores hepáticos benignos mais comuns, ocorrem em todos os grupos etários, sendo mais comuns nos adultos. Na grande maioria dos casos os hemangiomas são pequenos, assintomáticos e descobertos incidentalmente. Lesões maiores eventualmente podem produzir sintomas. O aspecto ultra-sonográfico desses tumores varia, sendo que o aspecto usual é o de lesão pequena hiperecogênica bem definida. Neste artigo, os autores fazem uma revisão sobre aspectos clínicos e ultra-sonográficos dos hemangiomas, ressaltando a importância desses aspectos na condução clínica dos pacientes acometidos.

Hemangioma; Fígado; Ultra-sonografia

REVIEW ARTICLE

Liver hemangiomas: ultrasound and clinical features* * Study developed in the Department of Radiology of Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina Universidade de São Paulo, SP, in the Diagnosis Center of Hospital Sírio Libanês, São Paulo, SP, and in the Department of Digestive Tract Diseases of Hospital Araújo Jorge Associação de Combate ao Câncer in Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil.

Márcio Martins MachadoI; Ana Cláudia Ferreira RosaII; Marcella Stival LemesIII; Orlando Milhomem da MotaIV; Osterno Queiroz da SilvaV; Paulo Moacir de Oliveira CampoliV; Jales Benevides Santana FilhoV; Paulo Adriano BarretoV; Rodrigo Alvarenga NunesVI; Mariana Caetano BarretoIII; Patrícia Medeiros MilhomemVII; Leonardo Medeiros MilhomemVII; Gustavo Barboza de OliveiraIII; Fernanda Barboza de OliveiraIII; Félix Cristiano Ferreira de CastroVIII; Alexandre Menezes de BritoVIII; Nestor de BarrosIX; Giovanni Guido CerriX

IInvited Professor at Faculty of Medicine Department of Radiology da Universidade Federal de Goiás

IIMD, Radiologist at Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina Universidade Federal de Goiás

IIIAcademics in Medicine at Faculty of Medicine Universidade Federal de Goiás

IVChief at Hospital Araújo Jorge Department of Digestive Tract Diseases Associação de Combate ao Câncer em Goiás

VSurgeons at Hospital Araújo Jorge Department of Digestive Tract Diseases Associação de Combate ao Câncer em Goiás

VIAcademic in Medicine at Faculty of Medical Sciences Universidade do Vale do Sapucaí

VIIAcademics in Medicine at Faculty of Medicine Universidade de Ribeirão Preto

VIIIResidents in Oncologic Surgery at Hospital Araújo Jorge Associação de Combate ao Câncer em Goiás

IXProfessor Doctor at Faculty of Medicine Department of Radiology Universidade de São Paulo

XTitular Professor at Faculty of Medicine Department of Radiology Universidade de São Paulo

Mailing address Mailing address: Dr. Márcio Martins Machado Rua Rui Brasil Cavalcante, 496, Ed. Art-1 Siron Franco, ap. 1101, Setor Oeste Goiânia, GO, Brazil 74140-140 E-mail: marciommachado@ ibest.com.br

ABSTRACT

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the liver, occurring in all age groups, and more frequently in adults. The vast majority of hemangiomas are small, asymptomatic, and are incidentally discovered. Larger lesions may eventually produce symptoms. The sonographic aspect of these tumors varies, the lesions being typically small, well defined and hyperechoic. In this study the authors review clinical and sonographic features of hemangiomas, highlighting the clinical significance of such features to be taken into consideration in the treatment of affected patients.

Keywords: Hemangioma; Liver; Ultrasound.

INTRODUCTION

Hemangiomas are the most frequent benign hepatic tumors, being found in about 7% of cases in necropsy studies(1). In the literature, a study reports an even higher occurrence 25% of the cases analyzed(2).

In the present paper, the authors evaluate clinical and ultrasonographic aspects of these tumors, highlighting the significance of combining such aspects to achieve a correct diagnosis and an adequate treatment of patients.

DISCUSSION

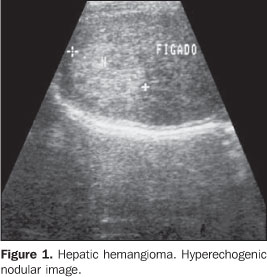

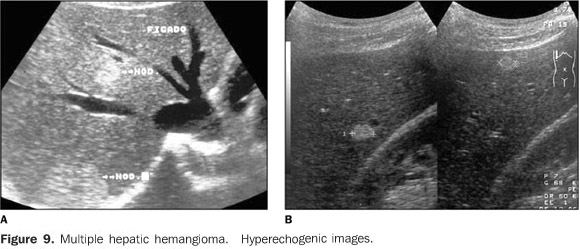

Typically, hemangiomas are single, with less than 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1), but two or more lesions (Figure 2) may be found in 10% to 30% of patients(1,3). They occur in all age ranges, more frequently in adults in the third, fourth and fifth decades of live(4). Women would be more frequently affected than men. In the Mayo Clinic series, 66% of the cases were women(4). Hemangiomas should be more appropriately studied since, usually, they do not require specific treatment. Although some authors report an even distribution in both hepatic lobes(5), others consider that hemangiomas would tend to localize more superficially and in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe(6).

These lesions, also, may be called "giant" (Figure 3), although there is not a consensus regarding the minimum diameter of a giant hemangioma (Figure 4). Several authors consider as giant the lesions measuring more than 4 cm, 6 cm and 8 cm(7), yet others say that giant hemangiomas would be those > 10 cm(3).

In some cases, hemangiomas present with peculiar characteristics. Some lesions may present cystic degeneration (Figure 5), many times centrally located, varying in extent, and, in some situations present like a lesion containing a significant cystic component (cystic hemangioma)(8). Areas of necrosis also may be observed, as well as central fibrotic areas. These aspects cystic alterations, necrosis and fibrotic alterations are more frequently found in larger lesions (usually those > 4 cm)(9). Another unusual occurrence is the fast growth of these lesions, which usually does not suggest neoplastic transformation, but rather ectasia of the preexistent vessels(10), associated with necrotic and hemorrhagic phenomena. Also, a rare possibility of infection in hemangiomas has been reported(11). Some lesions may present themselves pedunculated(6).

Usually, hemangiomas are asymptomatic, with less than 50% of patients presenting clinical manifestations(12), frequently associated with non-specific abdominal symptoms, like pain in the epigastrium and right hypochondrium, besides sensation of weight in the upper abdomen. Didactically, one can say that < 4 cm hemangiomas are rarely symptomatic. It is in cases of larger lesions and on physical examination that we can observe clinical manifestations. In larger lesions, different degrees of hepatomegaly may be found. Generally, when there are specific symptoms, chronic or acute abdominal pain is observed. Although the origin of such pain has not completely cleared up yet, it is suggested that it is caused by the growth of the lesion, resulting in distention of the Glisson's capsule. More rarely, these lesions may associate with obstructive jaundice and alterations of hepatic enzymes(13), besides gastric obstruction, torsion (in cases of pedunculated lesions) and spontaneous rupture(14).

According some authors, the incidence of hemangiomas would be higher in multiparous women(15); also, the lesions could increase in size during the gestation(15,16). Other sporadic reports mention the possibility of an increase in these lesions in women receiving exogenous estrogen(17). These relations should be understood as occasional occurrences; however they give the opportunity of discussing a possible relation between female hormones and these tumors(7).

Other manifestation reported in the literature is the association of cavernous hemangiomas with thrombocytopenia and hypofibrinogenemia, due to probable consumption coagulopathy and platelets trapping the called Kasabach-Merrit syndrome. This syndrome has been originally described as an association between thrombocytopenia, afibrinogenemia (hypofibrinogenemia) and skin and spleen hemangiomas in children. However, the term has currently been utilized to designate cases of consumption coagulopathy and platelets trapping associated with hepatic hemangiomas. Usually, this syndrome is found in children, and is rare in adults(1). Also, in children, congestive heart failure may occur as a result of arteriovenous fistulas in the hemangiomas, especially in the large ones(18).

Regarding the hepatic hemangiomas evolution, Trastek et al.(19) have analyzed 36 patients with hepatic hemangiomas during a period of up to 15 years (mean = five years and a half). These authors have not observed any case with bleeding, increase in clinical discomfort or death of patients. In four patients, the lesions increased, and in three, decreased. In the remaining patients, the lesions did not present any alteration in size.

Occasionally, hemangiomas may change their echogenicity with a change in decubitus (Figure 6) or with a Valsalva maneuver. Another important aspect to be taken into consideration is that hemangiomas may present inflammatory alterations, fibrosis and thrombosis, resulting in higher rigidity of some lesions. Cases with long standing thromboses may suffer calcification(5).

Hemangiomas, also, may be associated with other hepatic lesions like cysts, hepatocellular adenomas (Figure 7) and focal nodular hyperplasia, as well as Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome(6). In some studies, hemangiomas have been found in up to 25% of cases of focal nodular hyperplasia(20,21). Another association reported, although rare, is that between hepatic hemangiomas and hemangiosarcomas(10,22).

At ultrasound, frequently these lesion present as hyperechogenic (Figure 8) and well defined, homogeneous images, especially those with < 34 cm (Figure 9)(2325). The presence of a small, central, hypoechogenic area also may be observed. The hyperechogenicity probably results from multiple interfaces between vascular spaces. Additionally, a posterior acoustic enhancement may be demonstrated in some lesions(26). It is important to note that, in steatotic livers, hemangiomas may frequently present hypoechogenic (Figure 10).

More heterogeneous aspects may be identified, especially in larger legions. Sometimes, now more, now less echogenic areas representing fibrosis or ectatic vascular spaces. Some authors have observed these more heterogeneous aspects, especially in lesions with > 8 cm(7).

There are reports on other findings like presence of central, hypoechogenic areas dominating the aspect of lesions in a variable extent (Figure 11); others present predominantly hypoechogenic with a possibly hyperechogenic peripheral margin (Figure 12). Such hyperechogenic peripheral margin found in these hemangiomas, is a quite useful sign for differentiating these lesions from other hypoechogenic masses in the liver(24). When hemangiomas have this more heterogeneous aspect, the differentiation from other focal hepatic lesions of the liver becomes difficult.

The lesion may present with lobulated margins(18). According to some authors, calcifications would be unusual(27), however other authors report their presence in up to 20% of cases(28,29). It is important to note that, usually, hemangiomas do not present any hypoechogenic halo around the lesion(30), which also helps to differentiate them from other focal hepatic lesions.

Ultrasound contrast enhancement (microbubbles) also may demonstrate the vascular behavior of these lesions. Prolonged and moderate periods of contrast agent (microbubbles) retention inside the lesions have been reported(31).

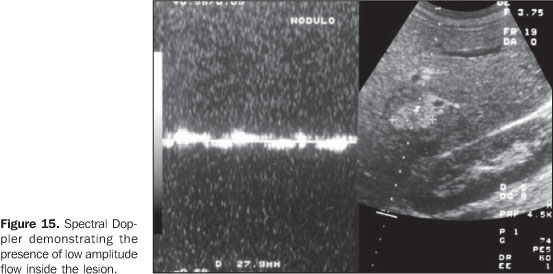

Doppler ultrasound present variable results in cases of hemangiomas. In many cases, no intralesional sign is detected (Figure 13), because of the low velocity of the blood flow in this lesions. In other cases, sparse venous signs are detected inside hemangiomas (Figure 14), presenting a hypointense and continuous spectral pattern (Figure 15)(32).

As previously mentioned, the greatest majority of these lesions do not demand specific treatment, with the possible exception of those patients with bulging lesions and chronic, debilitating symptoms. Cases of hemorrhage resulting from the rupture of these tumors, especially in neonates, are reported in the literature. However, such cases are extremely rare, particularly in adults(5).

Hemangiomas frequently do not cause compression of adjacent vessels (portal and hepatic venous branches and hepatic arterial branches), adapting themselves to these structures, without causing significant compression. However, it is important to note that larger lesions, as well as those presenting fibrohemorrhagic alterations, sometimes cause compressive disorders in the surrounding vascular structures.

Still, regarding vascular tumors in children, we must describe the infantile hemangioendothelioma and pediatric hemangiomas, since they represent the most frequent benign vascular tumors in this age range(33).

Some aspects of hemangiomas deserve special considerations. A higher tendency to rupture in neonates and infants than in adults has been reported(34). These tumors may produce high output heart failure because of arteriovenous fistulas, a phenomenon that has not been observed in adults. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and hypofibrinogenemia are rare manifestations, occurring more frequently in the pediatric group than in adults(5). The association of thrombocytopenia and hypofibrinogenemia is called Kasabach-Merrit syndrome. In the child, these lesions are associated with skin hemangiomas in up to 50% of patients(35). Many cases of death in children occur because of associated heart failure. When observed in infants and neonates, these hemangiomas are different from those found in adults and are rarely identified in children(33). Hemangiomas in neonates and infants are mesenchymal masses, presenting active endothelial growth. Some authors call them hemangioendotheliomas(33). These tumors may reach large dimensions(36).

Usually, children affected by hemangiomas or hemangioendotheliomas are less than six years old, and most of them are diagnosed before six months of age(37).

Clinically, infantile hemangiomas and hemangioendotheliomas are characterized by a set o three entities: hepatomegaly, congestive heart failure and skin hemangiomas(37). Kasabach-Merrit syndrome may occur both in cases of hemangioendotheliomas and hemangiomas affecting infants(37). Frequently, an abdominal mass is observed at physical examination. High output heart failure attributed to arteriovenous shunts" (anastomosis) in the liver(5), is an usual cause of death(5). There are studies demonstrating that the natural history of these tumors may course to spontaneous regression(5). As previously mentioned, according to some authors there is a possibility of rupture determining the patient death(37). Although usually hemangioendotheliomas are histologically benign lesions, malignant degeneration of these tumors has been described(38).

Ultrasound demonstrates the presence of a single or multiple lesion with variable echogenicity. Its aspect is solid, however, permeated cystic (anechoic) areas may be observed(33,36). Calcifications also may be present(33,36). The diagnosis of these benign vascular tumors of the liver in children may be corroborated by the evidence of alterations in hepatic arteries and veins, as well as in the celiac trunk. The celiac trunk and the common hepatic artery may be found dilated, while the caliber of the aorta is decreased below the origin of the celiac trunk. Additionally, the caliber of hepatic veins draining the lesion may be increasing. The above described changes in the vessels caliber are not identified as features of pediatric malignant hepatic tumors and are quite suggestive of benign vascular tumors (hemangiomas and infantile hemangioendotheliomas(39).

CONCLUSION

The authors conclude that hemangiomas are relatively frequent benign tumors whose usual aspect is that of well circumscribed, hyperechogenic lesions. However, there are variations in sonographic presentations, and one should be always alert to these possibilities which should be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis of hepatic masses, besides guiding supplementary evaluations for a conclusive diagnosis.

REFERENCES

Received October 28, 2004.

Accepted after revision February 12, 2005.

- 1. Ishak KG, Rabin L. Benign tumors of the liver. Med Clin North Am 1975;59:9951013.

- 2. Karhunen PJ. Benign hepatic tumors and tumor like conditions in men. J Clin Pathol 1996;39: 183188.

- 3. Powers C, Ros P. Lesões em massas hepáticas. In: Haaga JR, Lanzieri CF, Sartoris JD, Zerhouni EA, editores. Tomografia computadorizada e ressonância magnética do corpo humano. 3Ş ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 1994;803846.

- 4. Nichols FC, van Heerden JA, Wieland LH. Benign liver tumors. Surg Clin North Am 1989;69: 297314.

- 5. Foster JH. Benign liver tumors. In: Blumgart L H, editor. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. 1st ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1990;11151127.

- 6. Dähnert W. Radiology review manual. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins, 1996;456461.

- 7. Belghiti J, Vilgrain V. Management of hemangiomas. In: Lygidakis NJ, Makuuchi M, editors. Pitfalls and complications in the diagnosis and management of hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases. Surgical, medical and radiological aspects. 1st ed. New York: Thieme, 1993;7885.

- 8. Hihara T, Araki T, Katou K, Odashima H, Ohnishi H, Kachi K. Cystic cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Gastrointest Radiol 1990;15:112114.

- 9. Paley MR, Ros PR. Hepatic calcification. Radiol Clin North Am 1998;36:391398.

- 10. Takayasu K, Makuuchi M, Takayama T. Computed tomography of a rapidly growing hepatic hemangioma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1990;14: 143145.

- 11. Pol B, Disdier P, Treut PL, Campan P, Hardwigsen J, Weiller PJ. Inflammatory process complicating giant hemangioma of the liver: report of three cases. Liver Transplant Surg 1998;4:204207.

- 12. Jones RS. Benign diseases of the liver. In: Moody FG, editor. Surgical treatment of digestive disease. 2nd ed. Chicago: Year Book, 1990;381399.

- 13. Pateron D, Babany G, Belghiti J, et al Giant hemangioma of the liver with pain, fever, and abnormal liver tests: report of two cases. Dig Dis Sci 1991;36:524527.

- 14. Grieko MB, Miscall BG. Giants hemangiomas of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1978;147:783787.

- 15. Issa P. Cavernous hemangiomas of the liver. The role of radiotherapy. Br J Radiol 1968;41:2632.

- 16. Sewell JH, Weiss K. Spontaneous rupture of hemangioma of the liver. Arch Surg 1961;83:105109.

- 17. Morley JE, Myers JB, Sack FS, Kalk F, Epstein EE, Lannon J. Enlargement of cavernous hemangioma associated with exogenous administration of estrogens. South Afr Med J 1974;1:695697.

- 18. Dewbury KC. Benign focal liver lesions. In: Meire H, Cosgrove D, Dewbury K, Farrant P, editors. Abdominal and general ultrasound. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001;183207.

- 19. Trastek VF, van Heerden JA, Sheedy PF II, et al Cavernous hemangioma of the liver: resect or observe? Am J Surg 1983:145:4953.

- 20. Benz EJ, Bagenstoss AH. Focal cirrhosis of the liver: its relation to the so-called hamartoma (adenoma, benign hepatoma). Cancer 1953;6:743755.

- 21. Mathieu D, Zafrani ES, Anglade MC, Dhumeaux D. Association of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatic hemangioma. Gastroenterology 1989;97: 154157.

- 22. Tohme C, Drouot E, Piard F, et al Hemangiome caverneux du foie associé à un angiosarcome: transformation maligne? Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1991;15:8386.

- 23. Bree RL, Schwab RE, Neiman HL. Solitary echogenic spot in the liver: is it diagnostic of a hemangioma ? AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983;140:4145.

- 24. Kurosaki Y. Clinical aplication of ultrasound. In: Lygidakis NJ, Makuuchi M, editors. Pitfalls and complications in the diagnosis and management of hepatobiliary and pancretic diseases. Surgical, medical and radiological aspects. 1st ed. New York: Thieme, 1993;1216.

- 25. Machado MM, Rosa ACF, Cerri GG. Tumores e lesões focais hepáticas. In: Cerri GG, Oliveira IRS, editores. Ultra-sonografia abdominal. São Paulo: Revinter, 2002;125200.

- 26. Taboury J, Porcel A, Tubiana JP. Cavernous hemangioma of the liver studied by ultrasound. Radiology 1983;149:781785.

- 27. Marsh JI, Gibney RG, Li DKB. Hepatic hemangioma in the presence of fatty infiltration: an atypical sonography appearance. Gastrointest Radiol 1989;14:262264.

- 28. Ros PR. Computed tomography-pathologic correlations in hepatic tumors. In: Ferrucci JT, Mathieu DG, editors. Advances in hepatobiliary radiology. St. Louis: Mosby, 1990;75108.

- 29. Ros PR, Rasmussen JF, Li KCP. Radiology of malignant and benign liver tumors. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 1989;18:95155.

- 30. Nelson RC, Chezmar JL. Diagnostic approach to hepatic hemangiomas. Radiology 1990;176:1113.

- 31. Cosgrove DO. Ultrasound contrast agents. In: Meire H, Cosgrove D, Dewbury K, Farrant P, editors. Abdominal and general ultrasound. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001;6979.

- 32. Tanaka S, Kitamura T, Fujita M, Nakanishi M, Okuda S. Color Doppler flow imaging of liver tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;154:509514.

- 33. Patriquin HB. O fígado e o baço pediátricos. In: Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW, editores. Tratado de ultra-sonografia diagnóstica. 2Ş ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 1999; 14081438.

- 34. Clatworth HW, Boles ET, Newton WA. Primary tumors of the liver in infants and children. Arch Dis Child 1960;35:2228.

- 35. Larcher VF, Howard ER, Mowat AP. Hepatic hemangiomata: diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child 1981;56:714.

- 36. Swischuk LE. Imaging of the newborn, infant, and young child. 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997;352564.

- 37. Posner MC, Lilly RJ. Liver tumors in children. In: Blumgart LH, editor. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. 1st ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1990;11671177.

- 38. Kirchner SG, Heller RM, Kasselberg AG, et al Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma with subsequent malignant degeneration. Pediatr Radiol 1981;11:4245.

- 39. Meire BH, Mireaux-Dicks C. The paediatric liver and spleen. In: Meire H, Cosgrove D, Dewbury K, Farrant P, editors. Abdominal and general ultrasound. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001; 11971208.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

07 Feb 2007 -

Date of issue

Dec 2006

History

-

Accepted

12 Feb 2005 -

Received

28 Oct 2004