ABSTRACT

Objectives:

To determine the role of immunohistochemistry in identifying the primary site of tumors, and in establishing which bones are most frequently involved, their relationship with the primary tumor site, and the rate of pathologic bone fracture as the first symptom of a malignant tumor.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis of all medical records on bone metastases the cases treated between January 2006 and December 2011 at the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology was performed.

Results:

Immunohistochemistry correctly determined the primary tumor site in 61.2% of cases analyzed. Regarding the metastatic site, the most affected bone was the femur, accounting for 49.6% of the sample. Bone metastasis was the first symptom of the tumor in only 20.2% of patients, and of these, 95% were admitted for pathologic bone fracture.

Conclusion:

The study showed that the primary sites and their incidence rate are consistent with the literature reviewed. It was noted that in this sample, most patients did not present with pathologic bone fracture as the first clinical symptom of neoplastic disease. However, analysis of those patients that had a metastasis as the first clinical symptom revealed that it manifested itself as a pathologic fracture in almost all cases. The immunohistochemical study was consistent with the primary tumor site in most cases, indicating the value of the method in the detection of the primary site.

Keywords:

Fractures, spontaneous; Immunohistochemistry; Neoplasm metastasis

RESUMO

Objetivos:

Determinar a contribuição do estudo imuno-histoquímico na identificação do sítio primário da neoplasia, além de estabelecer quais os ossos mais frequentemente comprometidos, sua relação com o sítio primário neoplásico e a frequência de fratura em osso patológico como primeira manifestação do tumor maligno.

Métodos:

Foram levantados, retrospectivamente, todos os prontuários de metástases ósseas de janeiro de 2006 a dezembro de 2011 do Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia.

Resultados:

O estudo imuno-histoquímico determinou corretamente o sítio primário neoplásico em 61,2% dos casos analisados. Com relação à localização metastática, o osso mais acometido foi o fêmur, correspondeu a 49,6% da amostra. A metástase óssea foi a primeira manifestação da neoplasia em apenas 20,2% dos pacientes; desses, 95% deram entrada com quadro de fratura do osso patológico.

Conclusão:

O estudo evidenciou que os sítios primários e sua frequência de incidência são compatíveis com a literatura avaliada. Observou-se que, na presente amostra, a maior parte dos pacientes não apresentou a fratura do osso patológico como primeira manifestação clínica da doença neoplásica. Entretanto, quando analisados os pacientes que apresentaram como primeiro sintoma clínico a metástase, essa se manifestou por meio de fratura patológica em quase todos os pacientes. O estudo imuno-histoquímico foi compatível com o sítio primário neoplásico na maioria dos casos, demonstrou a relevância de tal método no auxílio da identificação do sítio primário.

Palavras-chave:

Fratura, espontâneas; Imuno-histoquímica; Metástase neoplásica

Introduction

Carcinoma metastases are the most frequent neoplasm in bone tissue, affecting mainly the axial skeleton (skull, ribs, spine, and pelvis) and the proximal limbs (humerus and femur), rarely occurring beyond the elbow or knee.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.

2 Anract P, Biau D, Boudou-Rouquette P. Metastatic fractures of long limb bones. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(1S):S41-51.

3 Takagi T, Katagiri H, Kim Y, Suehara Y, Kubota D, Akaike K, et al. Skeletal metastasis of unknown primary origin at the initial visit: a retrospective analysis of 286 cases. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129428, 26.

4 Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.

5 Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-76.-66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6.

The main primary sites of bone metastases are the breasts, lungs, prostate, thyroid, and kidney.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,22 Anract P, Biau D, Boudou-Rouquette P. Metastatic fractures of long limb bones. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(1S):S41-51.,66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6. Bone involvement of these neoplasms usually suggests disseminated disease, and other organs are probably then involved.33 Takagi T, Katagiri H, Kim Y, Suehara Y, Kubota D, Akaike K, et al. Skeletal metastasis of unknown primary origin at the initial visit: a retrospective analysis of 286 cases. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129428, 26.

Clinically, pain is the main symptom, which may be accompanied by local edema.44 Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.,55 Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-76. However, in several cases, the first manifestation is a pathological fracture44 Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.,77 Shibata H, Kato S, Sekine I, Abe K, Araki N, Iguchi H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bone metastasis: comprehensive guideline of the Japanese Society of Medical Oncology, Japanese Orthopedic Association, Japanese Urological Association, and Japanese Society for Radiation Oncology. ESMO Open. 2016;1(2):e000037.,88 Kandalaft PL, Grown AL. Practical applications in immunohistochemistry: carcinomas of unknown primary site. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(6):508-23.; the most affected sites are the ribs and vertebrae.55 Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-76. The evolution of the disease, with widespread involvement, is associated with vague symptoms, such as a decline in general health, malaise, anemia, and fever.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.

For diagnostic purposes, bone scan is an important tool.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,77 Shibata H, Kato S, Sekine I, Abe K, Araki N, Iguchi H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bone metastasis: comprehensive guideline of the Japanese Society of Medical Oncology, Japanese Orthopedic Association, Japanese Urological Association, and Japanese Society for Radiation Oncology. ESMO Open. 2016;1(2):e000037. This exam is easily carried out; it has high sensitivity, allowing not only to locate the lesion but also to assess multiple lesions.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,77 Shibata H, Kato S, Sekine I, Abe K, Araki N, Iguchi H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bone metastasis: comprehensive guideline of the Japanese Society of Medical Oncology, Japanese Orthopedic Association, Japanese Urological Association, and Japanese Society for Radiation Oncology. ESMO Open. 2016;1(2):e000037. Considering the fact that the variations in bone metabolism are established early, bone scan changes may precede radiographic changes by up to four months.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016. In this context, plain radiography is a valid exam in lesions with structure alterations above 25-30%, but it precludes an adequate evaluation of soft tissues. In turn, computed tomography and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging present higher sensitivity, allow the assessment in several planes, with high resolution and better soft tissue contrast.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6.

Pathological anatomy plays a key role in diagnosis. However, the use of routine methods is usually limited to a histological classification of the neoplasia, as they are unable to determine the primary site of the lesion. Immunohistochemical study is an important instrument in this sense. Two main classes of antibodies are used: cytokeratins and tissue-specific markers of some organs. Cytokeratins are divided into high and low molecular weight, according to their expression in different tissues. Low molecular weight cytokeratins (CK8, CK18) are expressed in simple epithelium, such as the glandular intestine and hepatocytes, while high molecular weight cytokeratins are expressed in complex epithelium, such as stratified squamous and transitional epithelium. However, the primary site immunohistochemistry begins with the use of two cytokeratins: CK7 and CK20, which allow a very useful discrimination of carcinomas (Table 1).

Modal distribution of cytokeratins CK7 and CK20 in some of the types of carcinomas most frequently associated with bone metastases.

The study is then complemented with the use of organ-specific markers, such as estrogen receptors, GCDFP-15, and mammaglobin A for the breasts; TTF-1 and Napsin A for the lungs; CDX2 and villin for gastrointestinal organs; PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase for the prostate; TTF-1 and thyroglobulin for the thyroid; and CD10 and RCC for the kidney.66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6.,88 Kandalaft PL, Grown AL. Practical applications in immunohistochemistry: carcinomas of unknown primary site. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(6):508-23.

The definition of the primary site allows appropriate treatment and prognostic evaluation.99 Papagelopoulos PJ, Savvidou OD, Galanis EC, Mavrogenis AF, Jacofsky DJ, Frassica FJ, et al. Advances and challenges in diagnosis and management of skeletal metastases. Orthopedics. 2006;29(7):609-20. This study is aimed at determining, in Brazil, which sites are most affected, the frequency of pathological fracture as the first manifestation of neoplasia, and the contribution of immunohistochemistry in the determination of the primary site of the neoplasm.

Material and methods

This study was conducted by the Department of Pathological Anatomy of a university together with the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of a hospital. All cases of bone metastases from January 2006 to December 2011 were collected from the records of the pathological anatomy department. Patients who received the diagnosis of bone metastasis were included in the study. Subsequently, patients’ charts were reviewed and epidemiological data were collected, as well as data about the affected bone and the primary site, once determined. It was also assessed whether bone metastasis was the first neoplastic manifestation and whether or not it was associated with a pathological fracture. Patients whose files were not located were excluded from the study. All data were compiled into an Excel spreadsheet and submitted to statistical analysis using the Epi Info program.

Results

The study included 131 patients, aged 28-87 years (mean: 58.5, median: 60); 72 patients were female (55%) and 59 male (45%). Almost all the records indicated patients who originated from the state of São Paulo (97.7%); only two patients were from Minas Gerais, and one from Goiás. A total of 79.4% declared themselves white, 16% declared to be of mixed race, and 4.6% declared to be black. Regarding marital status, 46.6% of the patients were married. When assessing the presence of comorbidities, 25.19% of the medical records did not contain the necessary information. Considering the valid data, 39.8% of the patients had systemic arterial hypertension and 11.2%, diabetes mellitus; 12.2% had a history of alcoholism and 31.6% were smokers.

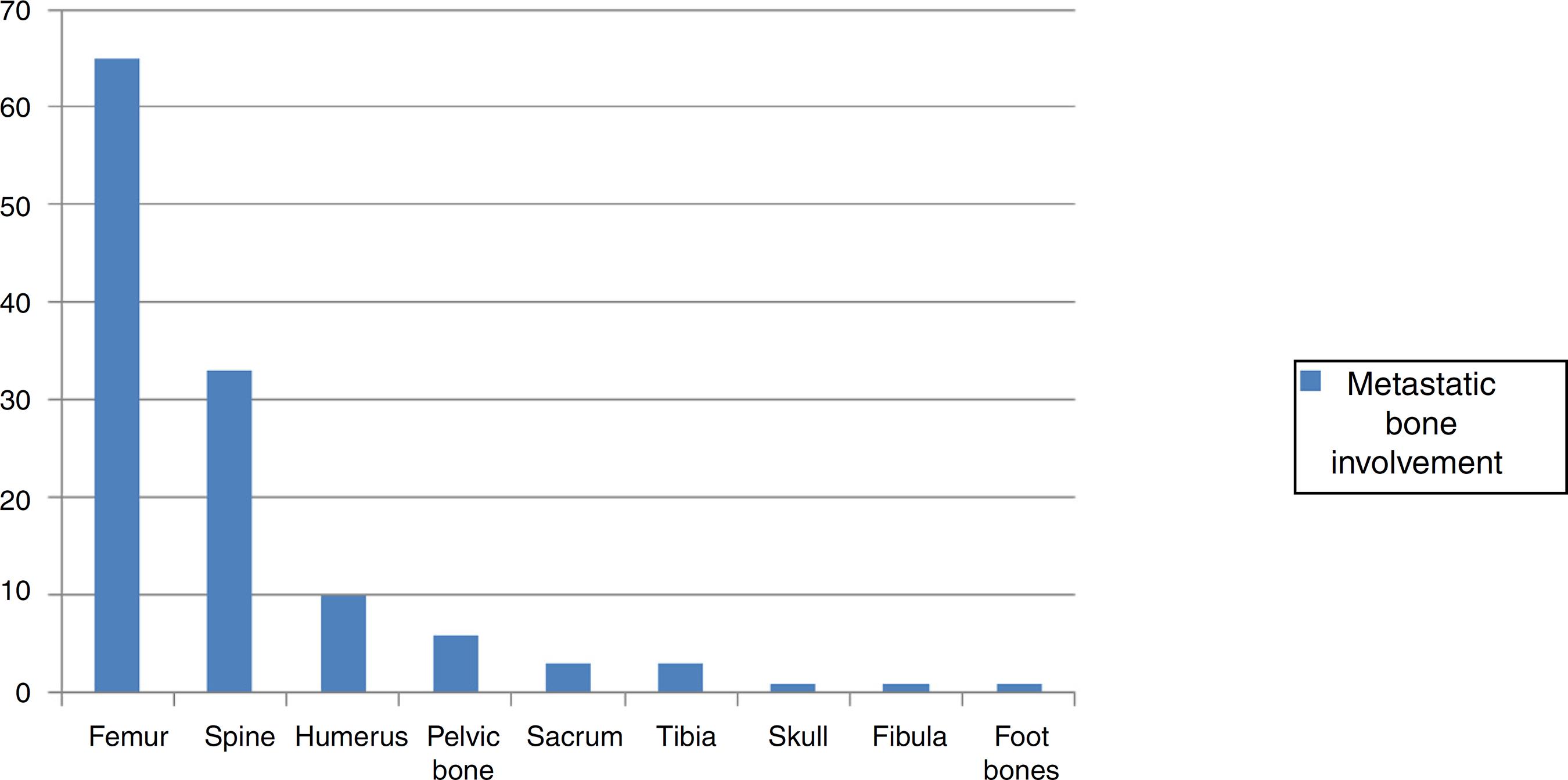

As to the location of the lesion, the most affected bone was the femur, in 65 cases (49.6%), followed by the spine (25.2%), humerus (7.6%), pelvic bones (4.6%), sacrum (2.3%), tibia (2.3%), skull (0.8%), fibula (0.8%), and foot bones (0.8%); 6.1% of the records did not indicate the location of the lesion (Fig. 1).

A total of 79 patients had a pathological fracture (Fig. 2), accounting for 60.3% of the cases (Confidence Interval: 51.4-68.7%). In 25% of these patients, the fracture was the first manifestation of the metastasis.

Surgical specimen showing a bone metastasis located in the proximal femur, with pathological fracture, and its respective radiographic image (pictures provided by the archives of the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of the hospital where the research was conducted).

When assessing whether bone metastasis was the first manifestation of neoplasia, 25.19% of the medical records did not contain this information. Considering the valid data, bone metastasis was the first neoplastic manifestation in only 20.2% of the patients, and of these, 95% had a pathological fracture when admitted to hospital.

At the time of medical chart assessment, the primary site of the neoplasia had not yet been established in 36 patients (27.5%). Among patients who already had the definitive diagnosis, 30 presented primary sites in the breasts (22.9%); 19 in the lungs (14.5%); 16 in the kidneys

(12.2%); 14 in the prostate (10.7%); three in the esophagus (2.3%); two in the thyroid (1.5%); and the remaining eight cases were related to each of the following primary sites: colon, endometrium, stomach, submandibular gland, ovary, pancreas, skin, and uterus (0.8% each).

An immunohistochemical study was performed in only 49 patients (37.4%). It was not possible to determine the primary site of the neoplasm in ten anatomopathological reports (20.4%). In the remaining 39, immunohistochemistry indicated a primary site: lung and prostate were the most frequent (20.4% each), followed by breast (16.3%), kidney (10.2%), digestive tract (6.1%), and colon, endometrium, and thyroid (2.0% each). In 61.22% of these cases, the indication of the possible primary site was confirmed during the follow-up period (nine cases in the prostate; seven, breast; seven, lung; five, kidney; one, colon; and one, thyroid).

Discussion

Bone metastasis is the most frequent neoplasm of bone tissue, occurring predominantly in the axial skeleton and proximal limbs.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,22 Anract P, Biau D, Boudou-Rouquette P. Metastatic fractures of long limb bones. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(1S):S41-51. It affects individuals of different age groups; in the present sample, age ranged from 28 to 87 years, with no predilection for gender (55% of women and 45% of men).

According to the literature, the most predominant locations are the axial skeleton (skull, ribs, spine, and pelvis) and the proximal limbs (humerus and femur), rarely occurring beyond the elbow or knee.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.

2 Anract P, Biau D, Boudou-Rouquette P. Metastatic fractures of long limb bones. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(1S):S41-51.

3 Takagi T, Katagiri H, Kim Y, Suehara Y, Kubota D, Akaike K, et al. Skeletal metastasis of unknown primary origin at the initial visit: a retrospective analysis of 286 cases. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129428, 26.

4 Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.

5 Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-76.-66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6. The present findings were consistent with the literature: the femur was the most affected bone (49.6%), followed by the spine (25.2%). Extremities were affected in only 0.8% of cases.

Clinically, pain is the main symptom, and it may be accompanied by local edema.44 Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.,55 Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-76. However, in several cases the first manifestation is a pathological fracture.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,44 Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.,66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6. In the present study, 60.3% of patients presented pathological fracture; however, in most (75%) of these patients, the fracture was not the first manifestation of the neoplastic disease. In turn, when assessing patients who presented metastasis as the first manifestation (20.2%), most of them had suffered a pathological fracture (95%).

The most frequent primary sites of bone metastases in the present study were the breast, lung, kidney, and prostate, in line with the literature retrieved.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.,22 Anract P, Biau D, Boudou-Rouquette P. Metastatic fractures of long limb bones. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(1S):S41-51.,66 Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6.

The immunohistochemical study contributes to the diagnosis of the primary site of neoplasia.11 Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016. Although it was performed only in part of the patients in this study (37.4%), it was observed to correctly indicate the primary neoplastic site in 61.2% of the cases; these were related to breast, lung, colon, prostate, kidney, and thyroid pathologies.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that the primary sites and their frequency of incidence are compatible with those found in the literature. In the present sample, it was also observed that most patients did not present a pathological fracture as the first clinical manifestation of the neoplastic disease. However, when assessing patients whose first clinical symptom was metastasis, it was observed that this symptom manifested itself as a pathological fracture in almost all patients. The immunohistochemical study was compatible with the primary neoplastic site in most (61.2%) of the valid cases analyzed, which indicates the relevance of such a method in the identification of the primary site; nonetheless, further studies should be conducted to more precisely determine its contribution.

-

☆

Study conducted at Departamento de Anatomia Patológica, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo (FCMSCSP), together with Serviço de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

REFERENCES

-

1Canale ST, Beaty J. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2016.

-

2Anract P, Biau D, Boudou-Rouquette P. Metastatic fractures of long limb bones. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(1S):S41-51.

-

3Takagi T, Katagiri H, Kim Y, Suehara Y, Kubota D, Akaike K, et al. Skeletal metastasis of unknown primary origin at the initial visit: a retrospective analysis of 286 cases. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129428, 26.

-

4Meohas W, Probstner D, Vasconcellos RAT, Lopes ACS, Rezende JFN, Fiod NJ. Metástase óssea: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(1):43-7.

-

5Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-76.

-

6Próspero J. Metástases de carcinoma. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. p. 211–6.

-

7Shibata H, Kato S, Sekine I, Abe K, Araki N, Iguchi H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bone metastasis: comprehensive guideline of the Japanese Society of Medical Oncology, Japanese Orthopedic Association, Japanese Urological Association, and Japanese Society for Radiation Oncology. ESMO Open. 2016;1(2):e000037.

-

8Kandalaft PL, Grown AL. Practical applications in immunohistochemistry: carcinomas of unknown primary site. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(6):508-23.

-

9Papagelopoulos PJ, Savvidou OD, Galanis EC, Mavrogenis AF, Jacofsky DJ, Frassica FJ, et al. Advances and challenges in diagnosis and management of skeletal metastases. Orthopedics. 2006;29(7):609-20.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Jul-Aug 2018

History

-

Received

8 Mar 2017 -

Accepted

20 June 2017 -

Published

11 June 2018