ABSTRACT

Objective:

to describe and evaluate the acceptance of a porcine experimental model in venous cutdown on a medical education project in Southwest of Brazil.

Method:

a porcine experimental model was developed for training in venous cutdown as a teaching project. Medical students and resident physicians received theoretical training in this surgical technique and then practiced it on the model. After performing the procedure, participants completed a questionnaire on the proposed model. This study presents the model and analyzes the questionnaire responses.

Results:

the study included 69 participants who used and evaluated the model. The overall quality of the porcine model was estimated at 9.16 while the anatomical correlation between this and human anatomy received a mean score of 8.07. The model was approved and considered useful in the teaching of venous cutdown.

Conclusions:

venous dissection training in porcine model showed good acceptance among medical students and residents of this institution. This simple and easy to assemble model has potential as an educational tool for its resemblance to the human anatomy and low cost.

Keywords:

Simulation; Dissection; Educational models; Models, Animal; Swine; Education; Medical

RESUMO

Objetivo:

descrever e avaliar a aceitação de um modelo experimental porcino no aprendizado de dissecção venosa em projeto de educação médica no sudoeste do Brasil.

Método:

um modelo experimental porcino foi desenvolvido para treinamento em dissecção venosa como projeto de ensino. Estudantes de medicina e médicos residentes receberam treinamento teórico sobre esta técnica cirúrgica e em seguida a praticaram no modelo. Após realizar o procedimento, os participantes preencheram um questionário sobre o modelo proposto. Este estudo apresenta o modelo e analisa as respostas ao questionário.

Resultados:

o estudo contou com 69 participantes que utilizaram e avaliaram o modelo. A qualidade geral do modelo porcino foi estimada em 9,16 enquanto a correlação anatômica entre este e a anatomia humana recebeu o escore médio de 8,07. O modelo foi aprovado e considerado útil no ensino da dissecção venosa.

Conclusão:

o treinamento de dissecção venosa em modelo porcino apresentou boa aceitação entre estudantes e residentes de medicina desta Instituição. Este modelo simples e de fácil confecção, tem potencial como instrumento de aprendizado por sua semelhança com a anatomia humana, e baixo custo.

Descritores:

Simulação; Dissecação; Modelos Educacionais; Modelos Animais; Suínos; Educação Médica

INTRODUCTION

Simulation based teaching has become popular in training of professional skills in several areas and a powerful learning tool in the medical area11 Huang GC, Sacks H, Devita M, Reynolds R, Gammon W, Saleh M, et al. Characteristics of simulation activities at North American medical schools and teaching hospitals: an AAMC-SSH-ASPE-AACN collaboration. Simul Healthc. 2012;7(6):329-33.

2 Beaubien J, Baker D. The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in health care: how low can you go? Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i51-6.-33 Heitz C, Eyck RT, Smith M, Fitch M. Simulation in medical student education: survey of clerkship directors in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(4):455-60.. Simulation allows the practice of procedures in a controlled environment, where the error is seen as an opportunity to improve learning, giving autonomy to the student, reducing the risk to patients, as well as being attractive to students22 Beaubien J, Baker D. The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in health care: how low can you go? Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i51-6.

3 Heitz C, Eyck RT, Smith M, Fitch M. Simulation in medical student education: survey of clerkship directors in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(4):455-60.

4 Gomez MV, Vieira JE, Scalabrini Neto A. Análise do perfil de professores da área da saúde que usam a simulação como estratégia didática. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2011;35(2):157-62.-55 Dourado A, Giannella T. Ensino baseado em simulação na formação continuada de médicos: análise das percepções de alunos e professores de um Hospital do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2014;38(4):460-9..

Venous cutdown is a relatively simple medical procedure that may be required in a trauma victim as a venous access option. According to the Advanced Trauma Life Support - ATLS®66 American College of Surgeons. Suporte avançado de vida no trauma para médicos: ATLS: manual do curso de alunos. 9th ed. Chicago (IL): American College of Surgeons; 2012., along with central venous access and intraosseous access, venous cutdown appears as second option of venous access if peripheral venous access is not possible. The choice of the method should be related to the performer’s experience and patient characteristics.

This article reports a low-cost and low-technology experimental porcine model used for venous cutdown training and analyzes its acceptance among medical students and residents of the institution.

METHODS

The study was conducted at Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná - Unioeste, from June 2013 to June 2014, as part of a registered education project (Prograd CR 40119/2013)77 Spencer-Netto FAC, Zacharias P, Cipriani RFF, Constantino MM, Cardoso M, Pereira RA. Modelo porcino no ensino da cricotiroidotomia cirúrgica. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2015:42(3):193-6.,88 Spencer-Netto FAC, Sommers CG, Constantino MM, Cardoso M, Cipriani RFF, Pereira RA. Projeto de ensino: modelo suíno para treinamento de drenagem torácica. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2016;43(1):60-3.. It attended 61 Medicine students (last year) and eight resident physicians of Internal Medicine Program. Participants used porcine models for resuscitation procedures training and evaluated them through a questionnaire.

Teaching Project Steps

Each training session comprised groups of about ten students or residents and was divided into the following steps: 1) discussion of the indication and complications of venous dissection, as well as the description of the technique according to ATLS6; 2) practice of the procedure by the participant under tutor supervision with critical and corrective analysis technique; 3) assessment questionnaire completing the model by participant.

Porcine Model of Venous Cutdown

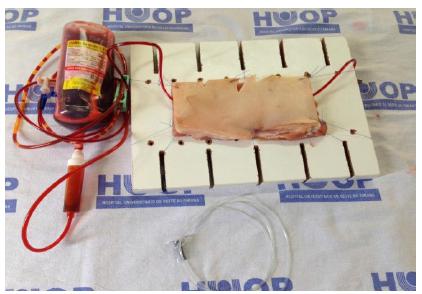

In each training session, two models containing a porcine piece composed of skin, subcutaneous tissue and muscle each were made. The porcine pieces were previously purchased in licensed local market and adequate for human consumption, according to the sanitary surveillance rules. For these models, leftovers from other skills laboratory models (chest drainage) were used, with no specific cost falling on them. Each piece was used to training five to nine students.

Each porcine piece was fixed by stitches, in a rigid wood surface (Figure 1). A nasogastric tube # 14 was passed between the muscle layer and subcutaneous tissue with the aid of a Kelly clamp, becoming palpable to perform the technique. The nasogastric tube was connected to an artificially colored IV solution system to simulate blood. The remaining materials were used in the Medical Skills Laboratory, obtained by donation at no cost. Details about the building of this model can be found in this site: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLAQ1e61Bdc.

Questionnaire

The evaluation questionnaire included epidemiological aspects of the trainees, previous training in managing hypovolemic shock with emphasis on fluid resuscitation (including peripheral venous puncture, deep venous and venous cutdown), and adequacy of the model for training medical students and residents. Some of the answers of the questionnaire were not object of this study, but used in order to improve the model and its application to graduation. Specifically, evaluations were requested of the overall quality of the model (robustness criteria, ease of handling and tissue similarity) and anatomical correlation (similarity to the expected anatomy in humans), both with scores ranging from 0 to 10. The questionnaire was prepared by the lead author and was not previously validated. All information obtained by the questionnaire were grouped into tables using Microsoft Excel® and analyzed with averages and percentages.

RESULTS

This project included 69 participants. Of these, 61 were graduate students of medicine (88.4%) and eight were medical residents (11.6%). Among the participants, the mean age was 25.8 (23 to 33). None of the study participants had performed a venous cutdown before.

As for quantifying the quality of the model, the average grade was 9.16 (7 to 10). The anatomical correlation between the model and the human anatomy was considered 8.07 (5 to 10). All participants judged the simulated training in experimental model useful before performing venous cutdown procedure in patients, as well as other procedures for obtaining venous access for fluid resuscitation.

This model was accepted by most of the participants (68/69 - 98,6%) as an adjunct in the training of venous dissection.

DISCUSSION

The use of simulators in several fields - medicine, nursing, engineering, aviation - have gained supporters, but it is still not universally used, since many factors are involved with its implementation as cost, teachers training, physical space, integration and critical evaluation of what is taught, in order to incorporate the simulation in curriculum repertoire of undergrads99 Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2007;2(2):115-25.

10 Wang EE, Beaumont J, Kharasch M, Vozenilek J. Resident response to integration of simulation-based education into emergency medicine conference. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1207-10.

11 Gaba D. The future vision of simulation in health care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i2-i10.-1212 Aggarwal R, Mytton O, Derbrew M, Hananel D, Heydenburg M, Issenberg B, et al. Training and simulation for patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19 Suppl 2:i34-i43..

This experimental model was considered by all participants of the study as useful in the teaching of venous cutdown at graduation level. They also considered important to conduct training on the model before performing this procedure in a real situation. Thus, the model was approved as an adjunct, in teaching venous cutdown by the participants. Venous cutdown is an alternative to venous access in situations where it is not possible to obtain intravenous percutaneous access. It is especially required in urgent care and emergency. Facing a multiple trauma patient with a hypovolemic shock, venous dissection is a procedure that may save lives by allowing quick access to infusion volume and drugs.

Due to the relatively low incidence of the need for phlebotomy, performing this procedure by undergraduate students of medicine and residents is minimal. Therefore, the proper training of venous cutdown by simulators, combining theoretical knowledge (technique, indications, contraindications and complications) with the execution of the procedure in a controlled environment and supervised way, offering no risk to patients, was considered important by all trainees, providing opportunities for learning and preparing for the execution of this procedure. This study confirms the importance of the use of simulation as a methodology in medical education, to make the student an active part in learning, encouraging the commitment to learn what is proposed and making the experience pleasurable to the trainee1010 Wang EE, Beaumont J, Kharasch M, Vozenilek J. Resident response to integration of simulation-based education into emergency medicine conference. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1207-10.. As in other studies11 Huang GC, Sacks H, Devita M, Reynolds R, Gammon W, Saleh M, et al. Characteristics of simulation activities at North American medical schools and teaching hospitals: an AAMC-SSH-ASPE-AACN collaboration. Simul Healthc. 2012;7(6):329-33.,1010 Wang EE, Beaumont J, Kharasch M, Vozenilek J. Resident response to integration of simulation-based education into emergency medicine conference. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1207-10.,1313 Robertson B, Kaplan B, Atallah H, Higgins M, Lewitt M, Ander D. The use of simulation and a modified Team STEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(6):332-7.

14 Takayesu J, Farrell S, Evans A, Sullivan J, Pawlowski J, Gordon J. How do clinical clerkship students experience simulator-based teaching? A qualitative analysis. Simul Healthc. 2006;1(4):215-9.-1515 Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ. 2006;40(3):254-62., the participants recognized the need to practice the procedure on models, with this well accepted model for training in venous dissection in our institution.

In regard to the assessment of the model anatomical correlation with the human anatomy, the participants attributed average to high similarity. It is cited by participants, as options for model improvement over the use of malleable material to simulate the vessel than the nasogastric tube used, providing greater tactile similarity to the venous consistency. In spite of different consistency of the nasogastric tube, this model allowed the trainee to execute all steps of a venous cutdown.

Despite the importance of venous dissection training in simulators, we found no other work in the literature showing models for this purpose. Because of its simplicity and low cost, this model is attractive in the early stages of medical training, particularly in centers where resources are limited. This study was realized in a simple porcine model not recreating the anatomical issues present in real situations, like the difficulty to palpate the vessel, anatomical alterations, obesity, etc. Because the experiment was realized in a controlled environment, it did not generate the stress that the executor is submitted when does the procedure in urgency situation, which is a negative factor in teaching.

Regarding the cutdown technique, it was not required to do a counter incision. The reason for this is based on the fact that the dissection realized by the study is oriented to the trauma environment, being recommended by ATLS course, to fluid reposition at the first moment. This venous access should be substituted as soon as possible.

The study was composed by inexperienced participants in the procedure of venous cutdown, being necessary the evaluation by experienced professionals to improve the model.

REFERENCES

-

1Huang GC, Sacks H, Devita M, Reynolds R, Gammon W, Saleh M, et al. Characteristics of simulation activities at North American medical schools and teaching hospitals: an AAMC-SSH-ASPE-AACN collaboration. Simul Healthc. 2012;7(6):329-33.

-

2Beaubien J, Baker D. The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in health care: how low can you go? Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i51-6.

-

3Heitz C, Eyck RT, Smith M, Fitch M. Simulation in medical student education: survey of clerkship directors in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(4):455-60.

-

4Gomez MV, Vieira JE, Scalabrini Neto A. Análise do perfil de professores da área da saúde que usam a simulação como estratégia didática. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2011;35(2):157-62.

-

5Dourado A, Giannella T. Ensino baseado em simulação na formação continuada de médicos: análise das percepções de alunos e professores de um Hospital do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2014;38(4):460-9.

-

6American College of Surgeons. Suporte avançado de vida no trauma para médicos: ATLS: manual do curso de alunos. 9th ed. Chicago (IL): American College of Surgeons; 2012.

-

7Spencer-Netto FAC, Zacharias P, Cipriani RFF, Constantino MM, Cardoso M, Pereira RA. Modelo porcino no ensino da cricotiroidotomia cirúrgica. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2015:42(3):193-6.

-

8Spencer-Netto FAC, Sommers CG, Constantino MM, Cardoso M, Cipriani RFF, Pereira RA. Projeto de ensino: modelo suíno para treinamento de drenagem torácica. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2016;43(1):60-3.

-

9Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2007;2(2):115-25.

-

10Wang EE, Beaumont J, Kharasch M, Vozenilek J. Resident response to integration of simulation-based education into emergency medicine conference. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1207-10.

-

11Gaba D. The future vision of simulation in health care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i2-i10.

-

12Aggarwal R, Mytton O, Derbrew M, Hananel D, Heydenburg M, Issenberg B, et al. Training and simulation for patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19 Suppl 2:i34-i43.

-

13Robertson B, Kaplan B, Atallah H, Higgins M, Lewitt M, Ander D. The use of simulation and a modified Team STEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(6):332-7.

-

14Takayesu J, Farrell S, Evans A, Sullivan J, Pawlowski J, Gordon J. How do clinical clerkship students experience simulator-based teaching? A qualitative analysis. Simul Healthc. 2006;1(4):215-9.

-

15Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ. 2006;40(3):254-62.

-

Source of funding:

none.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Sep-Oct 2017

History

-

Received

16 Mar 2017 -

Accepted

20 May 2017