Abstract

In the 1950s, Mário Pedro claimed Alfredo Volpi to be the greatest national painter and a master to be followed by younger artists. This was a conflict-ridden process, which put at stake the old canons of Brazilian modernism and also the way in which the history of national art was written. Following this process, we also come face-to-face with the mechanism responsible for mobilizing the presence of people, the persistence of national values and the importance of cities in the Brazilian artistic field.

Keywords:

Concrete art; Alfredo Volpi; Mário Pedrosa; modernism; artistic field

Resumo

Mário Pedrosa, na década de 1950, reivindicou Alfredo Volpi como o maior pintor nacional e como o mestre que deveria ser seguido pelos artistas mais novos. Esse foi um processo conflituoso, que colocou em xeque os antigos cânones do modernismo brasileiro e a forma como se narrava a história da arte nacional. Acompanhar esse processo é deparar-se com o mecanismo que agenciava a presença de pessoas, a persistência de valores nacionalistas e a relevância de cidades no campo artístico brasileiro.

Palavras-chave:

Concretismo; Alfredo Volpi; modernismo; campo artístico; Mário Pedrosa

The 1950s is treated by historiography as a turning point in Brazilian art: the transition from a provincial to a cosmopolitan ethos (Mammì, 2006Mammì, Lorenzo. (2006). Volpi. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.: 8), the hegemony of abstraction and the first signs of a contemporary art (Brito, 2007Brito, Ronaldo. (2007). Neoconcretismo: vértice e ruputra do Projeto Construtivo Brasileiro. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.; Villas Bôas, 2014Villas Bôas, Glaucia Kruse. (2014). Estética da ruptura: o concretismo brasileiro. VIS: Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arte da UnB, 13.). Mário Pedrosa is considered one of the leading figures in this transformation (Reinheimer, 2013Reinheimer, Patrícia. (2013). Candido Portinari e Mário Pedrosa: uma leitura antropológica do embate entre figuração e abstração no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Gramond.; Arantes, 2004), so too Alfredo Volpi, who was acclaimed by the former critic as Brazil’s greatest painter. If, though, we carefully follow Volpi’s reception by Pedrosa, it becomes clear that this shift was less a rupture than a negotiation between previously sedimented values and more recent ones, especially those of figurative art, the legacy of the inaugural generation of modernism, and those of abstract art.2 2 Another perspective is developed by Patrícia Reinheimer (2013: 16-17) who, comparing Portinari and Pedrosa, identifies a ‘non-linearity’ of a “process of axiological and epistemological transformation” in the Brazilian art world after the Second World War. Changes that, according to this author, were “as radical as those instituted by romanticism in Europe through the reformulation of ideas of the artist and modern art.”

Pedrosa wrote in Rio de Janeiro, also home to the artists to whom he was closest and to whom he recommended concretist, geometric and abstract art (Moura, 2011Moura, Flávio Rosa de. (2011). Obra em construção: a recepção do neocentrismo e a invenção da arte contemporânea no Brasil. Doctorate Thesis. PPGS/Universidade de São Paulo.). Consequently, he clashed with the accepted idea of São Paulo and Semana de 1922 (Modern Art Week, an arts festival held in 1922) as the epicentre of Brazilian modern art, having first revealed to artists the need to figuratively express the national. Volpi provided raw material and the possibility of a transaction between the already established imaginary and the imaginary demanded by the new generation. This process was the actualization, by the critic, of a mythology that located the painter (and his work) in the suburbs, describing him as a proletarian psychically marked by craft trades. While the earlier modernist ideology had mobilized a nationalist expectation around artistic valuation, Pedrosa, rather than breaking with this pattern, identified the justification for concretism in this socially determined psychology: while the abstract work might not represent Brazil, it could nonetheless be seen as an elaboration of the mind of a Brazilian. As an art critic, this involved reinventing a personality already known and celebrated in the universe and values of the art world and who had already been described, for example, by Mário de Andrade. What Pedrosa realized was a displacement and amplification of this mythology surrounding Volpi. He transformed the myth into a historical narrative on national art and into a path for visual innovation. Accompanying this process shows us how the metabolization of a figure by art criticism invented a person specific to the social and symbolic universe of art: the artist, who emerged accompanied by a restructuring of the macrohistorical narrative of this same universe.

Volpi was born in Lucca, Italy. He grew up in São Paulo, where he also trained as a painter (in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s). The São Paulo state capital lacked a public institution offering artistic training like the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro. Painters therefore taught themselves through a network of friends, full of immigrants who had trained as artists in Italy. Consequently, the presence of outsiders or the children of outsiders was the norm in the neighbourhoods and institutions frequented by Volpi, and the visual questions of the Italian peninsula arrived with them when they disembarked in São Paulo.3 3 The São Paulo world of literate culture proved hostile to the enormous contingent of first and second generation immigrants in the city, as Pontes & Miceli (2014) demonstrate. The visual arts, by contrast, presented themselves as a space strongly marked by their presence, a fact perceptible in the works of Freitas (2011), Brill (1984) and Belluzzo (1988), in which we can also note morphological characteristics of the São Paulo intellectual world in contrast to that of Rio, as Carvalho (2003) shows.

At the turn of the 1940s, Volpi began to paint suburban scenes in his studio without recourse to observation. He swapped his oil paints for tempera and abandoned the representation of human or atmospheric turbulence for architectonic structure instead. The movement of bodies, passage of clouds and composition of luminous forms in the beach waves were all relinquished: in their place, he intensified his study of masses of colour shaped into rigid and durable structures, usually walls, sky, ocean, ground and roofs that, through contrast and shading, constructed the spatialities of the canvases. In these works, Volpi seems to be responding to the Italian landscape painting of the period, which had been brought to São Paulo in 1937, in an exhibition subsidized by Benito Mussolini’s government to commemorate the centenary of Italian immigration.4 4 The relationship between Volpi and Italian modernist art is explored in Rosa (2015). I highlight, however, the similarity that this author identifies between some of Volpi’s canvases and others by the Italian modernist painter Carlo Carrà (whose work was included in the exhibition of Italian art held in 1937). I also emphasize the similarity between some of Volpi’s paintings and certain frescos by Giotto, Piero della Francesca and Margaritone d’Arezzo, who were celebrated by Carrà and other painters of the period as examples of a supposed ‘Mediterranean genius’: the pre-Renaissance painters were thus reference points for the generation of Italian artists committed to the return to order. In the exhibition catalogue we read:

From this arises the tendency to even further accentuate the constructive quality of the landscape, its essential lines and masses, no longer taking as a pretext the difference between the seasons, or the hours, or even what was called the ‘state of the soul,’ but instead the profundity of nature revealed in its intimate meanings of collaborating with man (Mariani, 1937Mariani, Valerio. (1937). Introdução. In: Mostra D’Arte del Padiglione d’Italia. São Paulo: Commissariato italiano per L’espozicione di San Paolo del Brasile.: n.p.).

It was also at this moment that critics started to take an interest in Volpi and that Mário de Andrade crystallized a particular form of apprehending the figure and work of the painter. This form functioned as a mythology, a set of descriptions repeatedly invoked over the history of national art whenever critics and admirers focused their attention on the artist. Mário de Andrade took as the topic of his reflection a generation of São Paulo painters of which Volpi formed part. This generation was precisely the one that had learned its métier among the networks of immigrant artists. The São Paulo poet described this generation’s style as the outcome of a proletarian psychology with an artisanal propensity: as a social condition that led to pictorial timidity and the choice of subject matter like suburban landscapes. According to the poet, these artists, due to the fact of being labourers, dreamt of a small property in the suburbs and approached these landscapes both as a place of leisure where they would spend weekends and enjoy moments of rest and as a theme for their paintings (Andrade, 1941aAndrade, Mário de. (1941a). Um salão de feira 1. Diário de São Paulo, São Paulo., 1941bAndrade, Mário de (1941b). Um salão de feira 2. Diário de São Paulo, São Paulo. and 1971Andrade, Mário de. (1971) [1944]. Ensaio sobre Clovis Graciano. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, 10, p 156-175.). This mechanism enabled the artists to be situated in Brazil, turning them into prime examples of a São Paulo type and, by extension, as a national type - which concealed, on its reverse side, the Italian affiliation of these works, making them relevant to the “larger modernist cause of making Brazil more familiar to Brazilians” (Botelho & Hoelz, 2016Botelho, André & Hoelz, Maurício. (2016). O mundo é um moinho: sacrifício e cotidiano em Mário de Andrade. Lua Nova, 97, São Paulo, p. 251-284.: 252). In the words of Heloísa Pontes (1998: 46-47)Pontes, Heloísa. (1998). Destinos mistos. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras., Mário de Andrade’s critical writing represented “a significant intervention in the field of the visual arts,” bringing artists on the periphery to the centre of debate, a position reserved until then to the first generation modernists.

As a result, the paintings of the generation concerned were depicted (and celebrated) as products of a psychology derived from São Paulo’s social stratification, effectively silencing the international traffic in favour of a localist discourse.5 5 The process of ‘Brazilianization’ of the generation of Paulista painters to which Volpi belonged is described by Rosa (2015: 49-77). It was precisely this identification of the style with a certain classicist psychology that would form the core of this mythology. This in turn would be taken up later by Mário Pedrosa to justify a new way of seeing Brazilian art and art history, which reappears in our own time, structuring how critics have approached the artist (Mammì, 2006Mammì, Lorenzo. (2006). Volpi. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.; Naves, 2008Naves, Rodrigo. (2008). A complexidade de Volpi: notas sobre o diálogo do artista com concretistas e neoconcretistas. Novos Estduos Cebrap, 8, São Paulo, p. 139-155. and 2011Naves, Rodrigo. (2011). A forma difícil: ensaios sobre arte brasileira. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.; Salzstein, 2000Salzstein, Sônia. (2000). Volpi. Rio de Janeiro: Campos Gerais.).

After 1945, the year Mário de Andrade died, Volpi’s paintings began to reject the illusion of perspective and reflect the strengthening of concretism in the country. In 1948 abstract art began to gain steam in Brazil (maral, 1984): the American artist Alexander Calder (1898-1976) exhibited in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, while museums of modern art were founded in São Paulo city and the federal capital, Rio, along the lines of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

In 1949, Waldemar Cordeiro (1925-1973) returned to live definitively in São Paulo. The young artist had spent time in Italy where he had converted to non-figurative painting. In São Paulo, he became a champion of concretism, an art that he valorised as an action in response to the city and industry, producing active objects rather than mere representations - art capable of being functional and aesthetic simultaneously. The concretists believed that their art was more suited to the contemporary world and that the existing methods of representation no longer made sense. They sought a form of painting that was “knowledge deducible from concepts,” something more than opinion that was communicated through logical and universal principles. This struck earlier generations, shaped by the modernist idea of revealing national reality in visual (and in some cases didactic) form, as anti-nationalist and cold.

The reception of this new art generated a tension between new and old artists, the latter having sometimes been trained alongside the inaugural generation of modernists and under the mythology of Semana de 22. Emiliano Di Cavalcanti (1897-1976), Anita Malfatti (1899-1964), Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) and Lasar Segall (1891-1957) occupied a prominent position in the narratives of the period on Brazilian art. They were consecrated as those responsible for the biggest artistic development to have ever unfolded in the country, with Candido Portinari (1903-1962) figuring as the great heir of this generation. Di Cavalcanti, who in the 1920s had been the creative force behind the Modern Art Week, militantly opposed abstract art, describing it as ‘hermetic,’ ‘individualist,’ ‘distant from reality’ and practiced by artists of an ‘irreparable solitude.’ Defending it, Di Cavancanti suggested, would be to “define the indefinable” (Amaral, 1984: 232-234).

Portinari had been the favourite artist of Mário de Andrade, the most influential critic to emerge from Semana de 22 and an intellectual sceptical of abstraction (Chiarelli, 2007Chiarelli, Tadeu. (2007). Pintura não é só beleza: a crítica de arte de Mário de Andrade. Florianópolis: Letras Contemporâneas.). As a painter acclaimed in cosmopolitan centres like Paris and New York, Portinari also offered the prospect of international recognition for Brazilian art, meaning that his presence was unavoidable in this context. His paintings and murals endeavoured to represent the nation and were founded on the ethics proclaimed by the Communist Party to which the painter was affiliated and for which he had stood as a candidate for senator. Portinari’s images inspired various artists and induced the rush of the Vargas government, and even the Roosevelt government in the United States, to find an iconography praising the work and celebrating Pan-American miscegenation.6 6 Portinari had been chosen to paint the murals of the Ministry of Education in Rio de Janeiro and those of the Library of Congress in Washington - a federal capital presided over by Getúlio Vargas, the other by Roosevelt. On Portinari’s position vis-à-vis the governments of the period, an interesting debate is developed by Aracy Amaral (2003: 242) in which describes Portinari as “the official painter” of the Vargas government. Anna Teresa Fabris (1990), for her part, situates him in his historical context, demonstrating, for example, the dissonance between the idea of the people in Portinari’s work and in the Vargas campaigns. Subsequently, Marcelo Mari (2006) returns to this debate, recognizing Fabris’s protest against Amaral’s claims, but nonetheless recalling the political uses that the Vargas government made of Portinari’s works.

At the start of the 1950s, Portinari, Di Cavalcanti and other artists from the 1920s generation were thus historical heroes and living interlocutors. They mobilized a discourse on the moral need to give expression to the country and remain true to figuration. Abstraction, on the other hand, was interpreted by these influential veteran artists as both anti-national and anti-ethical. Amid this clash of ideas, Volpi offered a consistent image able to cool some of these dilemmas and create a path for the inclusion of new tendencies in relation to the previous set of ideas. At the beginning of the 1950s, the houses painted by Volpi were reduced to their facades and thus to the two-dimensional. They are organized, for example, in the painting shown below, like a patchwork quilt: each element retains a certain autonomy and figures almost like a picture in itself. There is a juxtaposition of diverse facets, each with its own details and decorations. Together they compose the overall texture of the canvas.

Mário Pedrosa attributed the emphasis on the plane in Volpi’s paintings (already under way in the artist’s trajectory) to the voyage made by the painter to Italy in 1950, where he obsessively visited the work of Giotto di Bondoni (1266-1337), saw Piero della Francesca (1415-1492) and fell in love with Margaritone d’Arezzo (c.1240-1290) (Pedrosa, 2004: 269). Whether or not we agree with Pedrosa’s view that the voyage was a turning point in the artist’s career, the fusions made by Volpi in these paintings are undeniable. In these pictures, he decomposes the urban landscapes into planes and, through the juxtaposition of the latter, creates complex spatial relations in the concretist style: sometimes an object appears behind, sometimes in front; sometimes a facet of the picture is the street, at other times a wall; at one moment sky, at another moment sea. However, he does not abandon his preferred subject matter: the architecture of the Brazilian suburbs that was the theme of so many of his canvases. Even if we concur with Pedrosa and hold the pre-Renaissance artists responsible for the accentuation of the plane in Volpi’s work, it needs to be observed that Giotto, Margaritone d’Arezzo and Piero della Francesca were exalted in Italy and São Paulo alike (Fagone, 1978Fagone, Vittorio. (1978). Carlo Carrà: tutti gli scritti a cura di Massimo Carrà. Milano: Feltrinelli.; Chiarelli, 2003Chiarelli, Tadeu (2003). L’Italia è qui: uma prezentazione. In: Chiarelli, Tadeu & Weschsler, Diana B. Novecento sudamericano: relacione artistiche tra Italia, Argentina, Brasile e Uruguai. Milano: Milano Skira.) and, therefore, everything suggests that Volpi was already familiar with the work of these artists before travelling to Italy, probably from photographs. The suburban neighbourhoods, on the other hand, were central to Mário de Andrade’s descriptions of Volpi and other painters of his generation, as well as being a feature that situated them firmly in Brazil, enhancing their significance for critics advocating a nationalist art style.

Waldemar Cordeiro (1952: n.p.)Cordeiro, Waldermar. (1952). Volpi, o pintor de paredes que traduziu a visualidade popular: o rapazola que comprou uma caixa de aquarelas usadas - Nas mansões servia ao cosmopolitismo, mas amava os coloridos do subúrbio. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo., leader of the Ruptura group of concrete artists, became enchanted by these paintings at the start of the 1950s which, he wrote, “elevat[ed] the visual feeling of the Brazilian people to a universal language. From the retreat of his small house on Rua Gama Cerqueira, 154, [Volpi] works on paintings representing the nation in Venice, Tokyo, Chile and around the world.”

In the same article, published in the São Paulo newspaper Folha da Manhã, Waldemar Cordeiro (1952: n.p.)Cordeiro, Waldermar. (1952). Volpi, o pintor de paredes que traduziu a visualidade popular: o rapazola que comprou uma caixa de aquarelas usadas - Nas mansões servia ao cosmopolitismo, mas amava os coloridos do subúrbio. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo. situated Volpi as “a great artist... riff-raff in life,” untouched by the ‘public authorities’ who never looked to “create a social status for artists,” and forgotten too “by those who waste large amounts on purchasing fake and commercial paintings” without discovering “that art exists.” The intention was to claim Volpi for the concretist group, along with obtaining legitimacy and patronage for the new generation. Cordeiro saw Volpi’s paintings as simultaneously national and universal, both landscapes and logical concepts. They allowed the intersection of two discourses - the discourse of an art based on the reforming of human sensibility (concretism) and the discourse of the earlier nationalist and figurativist generations. Cordeiro’s argument is supported by two sources of evidence: the first are Volpi’s canvases themselves, which converged with the expectations of the concretists and the veterans. The second echoes an idea formulated by Mário de Andrade the previous decade. Cordeiro (1952: n.p.)Cordeiro, Waldermar. (1952). Volpi, o pintor de paredes que traduziu a visualidade popular: o rapazola que comprou uma caixa de aquarelas usadas - Nas mansões servia ao cosmopolitismo, mas amava os coloridos do subúrbio. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo. tells us that

about ten years ago, Volpi stopped painting buildings. When he turns to the wall, it is to paint his beautiful murals, as found in the Church of Christ the Worker or in the luxury homes that he decorated. However his art, even when working through an intellectual problem, always retains the flavour of those muddy hues of the wattle and daub cottage.

Even for the concretists, it was the artist’s proletarian and artisanal status that added ‘flavour’ to Volpi’s paintings. And the critical point for the legitimacy to which Cordeiro aspired was the “visual feeling of the Brazilian people,” a feeling that Volpi elevated. In other words, by transforming the popular into the universal, the painter of streamers became something special for Cordeiro. And what was popular was the vision and taste of the urban peripheries of the period.

The suburban neighbourhoods painted by Volpi - as well as Cambuci, the district in which he lived - emerged in São Paulo from the 1870s onward when the aristocracy began to sell their farms and, consequently, cleared the way for industrial and residential zones (Salmoni & Debenedetti, 1981Salmoni, Anita & Debenedetti, Emma. (1981). Arquitetura italiana em São Paulo. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva.: 36). In these localities, factories were built, along with workers villages or even proletarian housing developments: neighbourhoods constructed by masons and master builders of Italian origin. While in the city centre architects designed houses that mixed elements from diverse traditions, such as classical Italian or English Gothic, in the suburbs the masons constructed houses mixing these same elements according to their own interpretation and convenience, but without any systemization or method (Salmoni & Debenedetti, 1981Salmoni, Anita & Debenedetti, Emma. (1981). Arquitetura italiana em São Paulo. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva.: 45). The pioneers of Brazilian modernist architecture, Rino Levi (1901-1965) and Gregori Warchavchik (1896-1972), arrived in São Paulo in the 1920s and encountered a city with a strong taste for vivid colours, opposite to the standard white tone that they advocated (Salmoni & Debenedetti, 1981Salmoni, Anita & Debenedetti, Emma. (1981). Arquitetura italiana em São Paulo. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva.: 45). The suburbs had been recently built or were expanding at the hands of master builders with eclectic tastes (Homem, 1984Homem, Maria Cecília Naclércio. (1984). O prédio Martinelli, a ascensão do imigrante italiano e a verticalização de São Paulo. São Paulo: Editora Projeto.: 35).

In Cordeiro’s view, the paintings of Volpi, considered a labourer, thus formed part of this suburban and proletarian environment. They turned these places into a universal and sublime reflection. This transformation of popular visuality into concrete language similarly impressed the English art critic Herbert Read (1893-1968), a member of the II São Paulo Art Biennale jury in 1953. That year the judges had decided to award the prize for best national painting to Di Cavalcanti, but Herbert Read disagreed and the prize ended up being shared between Di Cavalcanti and Volpi (Hoffman, 2002Hoffmann, Ana Maria Pimenta. (2002). A arte brasileira na Segunda Bienal do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo: o Prêmio Melhor Pintor e o debate em torno da abstração. Master’s Dissertation. PPGH/Universidade Estadual de Campinas.: 105). According to Read (1953: n.p.), the Brazilian painting on display at the Biennale was:

‘very lively’ - but demonstrates that Brazilian artists are very highly aware of what is happening in the world. [...] on taking in the Brazilian works, I felt, as I have indeed felt in every country, that there is a danger that an international style may develop, imperceptibly erasing all local feelings and sensibilities. I wandered in search of something that had truly sprouted from this country.

Herbert Read (1953: n.p.)Read, Herbert. (1953). Sir Herbert Read fala da participação brasileira na Bienal e do abstracionismo em geral. (Entrevista concedida a Ivone Jean.) Folha da Manhã, São Paulo. found this local seed in Volpi’s pictures and described the painter as “an artist aware of the general movement, but who created something original. He made something contemporary with an indigenous theme: the forms and colours of modern Brazilian architecture.”

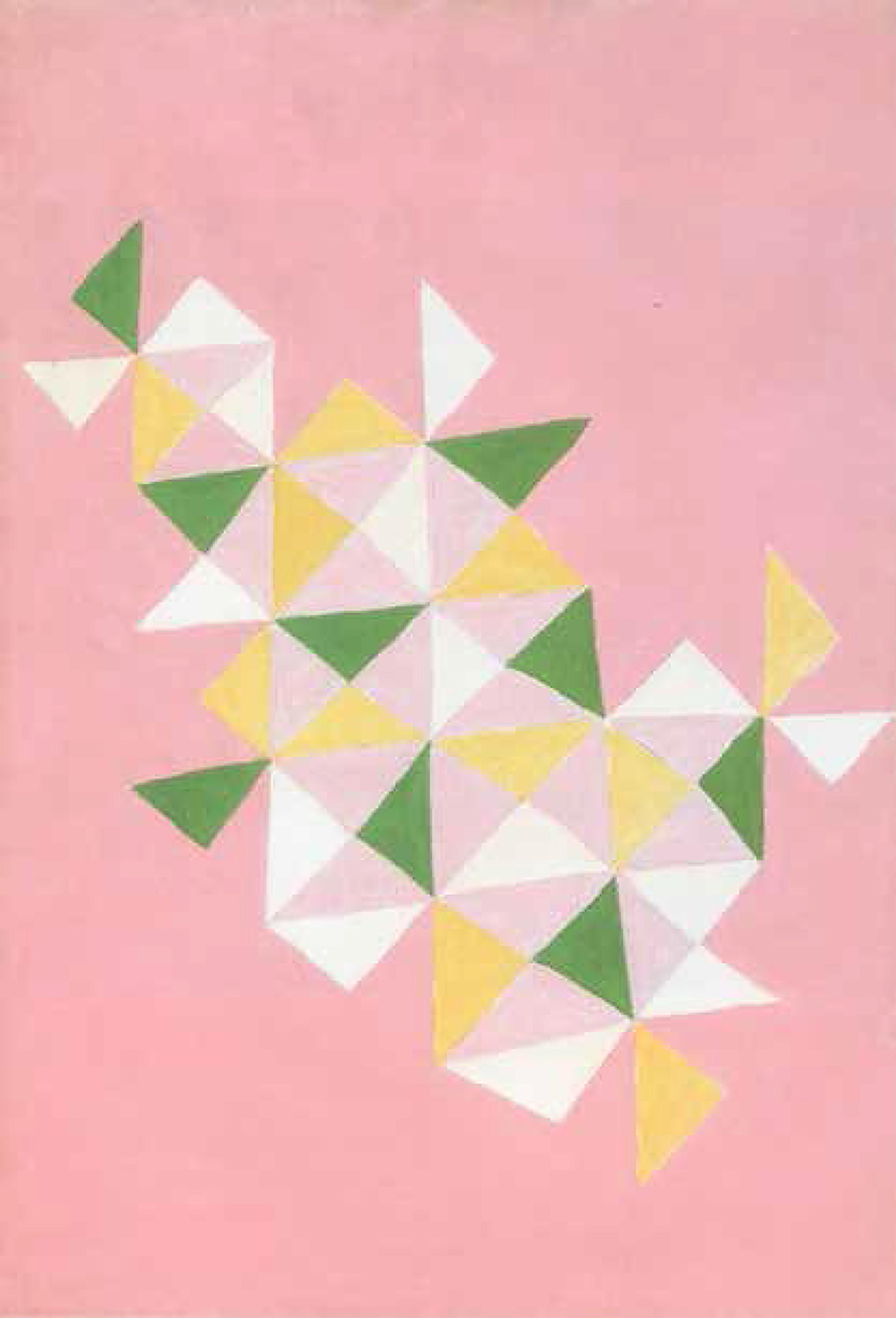

The sharing of this prize proved to be a historiographic landmark in the consolidation of abstract painting in the country and projected Volpi to the centre of contemporary discussions in art.7 7 Maria de Fátima Morethy Couto (2004: 70-71) sketches an interesting panorama of the Brazilian avant-garde. In her book, she reaffirms the first and second São Paulo biennales as landmarks in the consolidation of abstract art in the country and comments on the prize awarded to Volpi. While this demarcation is regularly found in historiography, her work is especially interesting since it shows how this historiography can be traced back to Mário Pedrosa himself. Recipient of the award at the São Paulo Biennale and claimed by the concretists, he boosted his influence in the Brazilian art world, his commercial power and his appeal for the critics. The concretists took a closer interest in Volpi, who began to focus exclusively on producing geometric works. While the concretists wanted to make pictures that set out from ideal and logical principles, Volpi made paintings of an empirical origin synthesized in geometry.8 8 “It should be said, in any case, that Volpi’s adherence to concrete poetics was never unconditional, nor did it represent a fracture in the evolution of his language. Like the concrete poems of Manuel Bandeira, which are almost always love poetry, the best concrete paintings of Alfredo Volpi express not so much the search for objectivity as the demureness of a subjectivity that, by way of purification, turns into geometric form. They are not ideas that became realities, but realities that became ideas” (Mammì, 2006: 33). For a discussion of the concretist period in Volpi, see too Naves (2008). An example of this process is the work Cata-vento (Toy windmill), (p. 855), exhibited at the 1955 Biennale. This canvas is simultaneously a composition of coloured triangles organized to suggest rotation and reminiscent of the toy that gives the painting its name. Alongside this work, Volpi presented canvases of facades and, according to the critic José Geraldo Vieira (1955: n.p.)Vieira, José Geraldo. (1955). O urbanismo lírico de Alfredo Volpi. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo., what the artist had achieved between the two biennales of 1953 and 1955 was “the diligence of a concretism at once solid and harmonious,” though one seeking to “impregnate all of this with the lyricism of a sensory atmosphere in which the urban phenomenon presupposes [...] the watchfulness of the humanity present.” For the critic, Volpi remained the “painter of the street, the sidewalk, the block, both of the centre and of the outskirts” (Vieira, 1955Vieira, José Geraldo. (1955). O urbanismo lírico de Alfredo Volpi. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo.: n.p.).

This diligence of concretism would attract the attention of the biggest champion of this type of art in Brazil: the critic Mário Pedrosa, who, as well as an intellectual, was also a political activist linked to Trotskyism and the Fourth International. Because of his activism, the critic had been exiled from the country in 1937, during the Vargas government, and his position on the arts can be traced to his experiences outside Brazil, especially in New York, along with other intellectuals and activists.

Squeezed between democratic realism and Soviet realism, some American intellectuals converted to abstract art. 1934 was the year of the foundation of the Partisan Review, in which Trotsky published, together with Breton and Rivera, the manifesto for an independent art and Clement Greenberg, the champion of Jackson Pollock, began his career. While realist art had been appropriated by state authorities, abstraction emerged as the alternative for ensuring the critical function of art, dispelling the possibility that a painting, for example, could be used to represent a political party or ideal (Mari, 2006Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo.). At that time, New York had also claimed the role previously occupied by Paris as guardian of the cultural values of the West. The global centre of the arts market had migrated to the US city. New institution were created like the Museum of Modern Art to show avant-garde art, and a critic, Clement Greenberg, confidently proclaimed the art of the United States as the most advanced in the world (Guilbaut 1985Guilbaut, Serge. (1985). How New York stole the idea of modern art. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.).

Pedrosa converted to abstractionism in 1944, during a visit to an Alexander Calder exhibition at MoMA in New York (Arantes, 2004: 53).9 9 On the gravitation of New York intellectuals around the Partisan Review, see Cooney (1986) and Pontes (2003). Calder sculpted abstract forms and arranged them in mobiles (p.856). The mechanics of these sculptures moved the pieces in unpredictable ways. What this artist offered Pedrosa was the possibility of combining a technical and typically modern rationality with a human and ironic dimension. The mechanical assemblage of the work made its behaviour unpredictable and thus imponderable, denaturalizing the technical itself (industrial and capitalist expression) and imbuing it with an inventive grace.

It was in Gestalt theory that Pedrosa found an intellectual allegiance for his ideas. Based on this current of thought, he wrote his thesis On the affective nature of form in the art work in which he argued that “what is specific to artistic knowledge is intuition. And the revitalization of this is posed precisely as the great educational mission of modern art” (Arantes, 2004: 69). For the critic, it was modern art’s task to undo the separation between intelligence and sensibility, and, consequently, the separation between subjectivity and objectivity, form and expression (Arantes, 2004: 72). These conjunctions were only possible, Pedrosa argued, because the laws governing the structure of the work also informed the artistic perception and realization. Hence, the art work was realized through its intrinsic or formal characteristics and it was through intuition itself (not an external narrative) that the work performed its reinvigorating role. “There exists, therefore, at the very least, a kinship or perfect homology that renders the traditional subject-object opposition innocuous and explains the non-discursive and intuitive character of art” (Arantes, 2004: 74). And while Gestalt theory was to be Pedrosa’s main source of inspiration, others would follow, counterbalancing an excessive formalism with the search for an affective element or, in some instances, an element unconscious to the artist. Pedrosa’s view of the works saw a convergence of the human bases (socially localized and intimate to each artist) and a structured and universal will (in which technical rigour was encouraged).

Returning to Brazil in 1945, he became the country’s first professional critic. Distancing himself from his predecessors, he did not write fiction or poetry, for example, his professional prerogative. Through theoretical rigour, he also sought to define a new way of thinking about art without, though, isolating himself in academic discourse, working mainly for newspapers and cultural institutions without abandoning his political activism (Arantes, 2004: 74). In 1945 and 1946, he simultaneously created the Popular Socialist Union (União Socialista Popular), the weekly publication Vanguarda Socialista and the arts section of the newspaper Correio da Manhã. Defence of free thought was heralded as one of the weekly’s central tenets and would prompt its critique of the Communist Party (Mari, 2006Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo.: 152). At the end of the Second World War, the Communist Party received support from diverse Brazilian intellectuals and artists. The organization had emerged as victorious against fascism and as an institution that had fought, most of the time, against the Vargas dictatorship. The recently installed Brazilian democracy allowed the party to exist again legally and to exert an enormous attraction on intellectuals and artists in Brazil. Jorge Amado was a member along with Caio Prado Junior. And Candido Portinari would join them. Critics from the weekly publication opposed the co-option of the Brazilian intelligentsia, especially Portinari, who would stand as a Communist Party candidate for deputy and senator in 1945 and 1947, respectively, and declared his work to be at the service of his political ideals. Portinari thus aligned himself with the modernist ideals of the 1920s generation and those of the Communist Party: the painter advocated an art capable of a didactic impact on the Brazilian people and thus a figurative aesthetic, easy to apprehend and based on the representation of the country’s problems (Mari, 2006Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo.).

It is no wonder, then, that Pedrosa collided with the consecrated modernism of 1920: political co-opted and aesthetically out-of-date, both were motives for the critic to oppose the legacy of Semana de 1922. And the figure of Portinari would comprise a key adversary.

With the worsening of the Cold War, the tension between critic and artist became evident. In 1947, under pressure from the United States, the Dutra government suppressed the Communist Party and, in 1948, Portinari painted the mural Tiradentes, in which he depicted the eighteenth-century revolutionary martyr Tiradentes, a leader of the Inconfidência Mineira (Minas Gerais Uprising) against the Portuguese, with the face of the contemporary communist revolutionary Luís Carlos Prestes (1898-1990), making his painting a national elegy for the fight against the colonizer. Echoes of this message could be heard both in the Brazilian situation vis-à-vis the United States and in the position adopted by the USSR in the Korean War.

The Tiradentes mural earned Portinari accolades from intellectuals linked to the Communist Party in France and Warsaw - and a pretext for Pedrosa to launch his harshest attacks yet against him (Mari, 2006Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo.). According to Marcelo Mari, Pedrosa in 1948 had already expressed his conviction that Portinari should search for intrinsically visual values rather than naturalist representation: this had been the motive for the critic’s interest in the canvas Primeira Missa (First Mass), in which he recognized that the painter had begun to explore this path of the autonomy of form. Yet as the Cold War intensified, Portinari reversed direction and, in the 1949 work, declared the subservience of his art to the universe of politics where narrative loomed over everything.

When Pedrosa wrote about Portinari’s Tiradentes, his criticism focused primarily on the subservience of the painting’s composition to the narrative. Pedrosa demonstrated how this caused the mural to lose its dramaticity, its good taste and even its continuity. For Pedrosa, the narrative mural was also unsuited to the modern building that it occupied. The building was made of glass, concrete and other materials utilized - the critic argued - in a simultaneously structural and aesthetic form. The building was not, therefore, organically in tune with an art work that failed to fuse the decorative and the functional. Not even the choice of colours escaped Pedrosa’s critique, the painter’s palette accused by him of referring unthinkingly to the pleasure of certain painful passages of the narrative (Pedrosa, 2004).

Pedrosa’s stance, opposite to the directives of the Communist Party, did not stop there. He also developed close contacts with the Biennale, while the party banned the participation of affiliated artists in the 1951 show (Mari, 2006Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo.: 215). The critic’s involvement in the Biennale, which saw him shuttle between São Paulo and Rio, brought him closer to São Paulo’s young abstract painters (Hoffman, 2002Hoffmann, Ana Maria Pimenta. (2002). A arte brasileira na Segunda Bienal do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo: o Prêmio Melhor Pintor e o debate em torno da abstração. Master’s Dissertation. PPGH/Universidade Estadual de Campinas.: 259), but it was mainly among the Cariocas10 10 The terms Carioca and Paulista refer to the inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, respectively.[T.N.] that Pedrosa’s influence was strongest: the Rio de Janeiro artists gathered around the critic in various ways and became his protégés. Calling themselves the Frente (Front) group, Pedrosa instructed them ideologically and mobilized their network of relations, offering institutional support, whether from MAM-Rio, the Jornal do Brasil newspaper or other institutions (Moura, 2011Moura, Flávio Rosa de. (2011). Obra em construção: a recepção do neocentrismo e a invenção da arte contemporânea no Brasil. Doctorate Thesis. PPGS/Universidade de São Paulo.: 25).

Backed by Calder and the theory of form, Pedrosa perceived an ethical justification and social participation for concretism. The catalogue for the Frente group’s show in 1955, written by the critic himself, made this clear:

Art for them [the artists of the Frente group] is not an activity of parasites, nor is it at the service of the idle rich, political causes or paternalist State. An autonomous and vital activity, it aims to fulfil the highest social mission, namely to give style to the period and transform men, educating them to exercise the senses fully and to shape their own emotions (Pedrosa, 2004: 248).

But what could concretism say specifically about Brazil? This nationalist justification for art would be conceived by Pedrosa in 1957 and would take Alfredo Volpi as its mainstay. The foundation stone of this edifice had been the national exhibition of concrete art, held at the end of 1956 in São Paulo and at the beginning of 1957 in Rio de Janeiro. Volpi had been invited to exhibit in this show, an occasion that allowed Décio Pignatari (1927-2012, who also exhibited work) to hail him, in Rio de Janeiro, as the greatest Brazilian artist (Pignatari, 1957Pignatari, Décio. (1957). Ferreira Gullar entrevista Décio Pignatari. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.). Also during the show, Mário Pedrosa and his ally, Ferreira Gullar, launched three texts, two by Gullar and one by Pedrosa, the latter separating the exhibition artists into Paulistas and Cariocas and analysing them through the contrast between the characteristics of the artists from each city.

Pedrosa was aware that São Paulo had become the central hub of visual arts in the country, highlighted by the biennales, and his text looked to situate the city and its intellectual output in a precise and delimited place in Brazilian art. According to the critic in “Paulistas e cariocas,” a difference existed between ‘more theoretical’ peoples and others for whom theory mattered less. Pedrosa asks “why is it [...] that the Italian is always more theoretical than the French, the German than the English, the Russian than the American [...] and the Paulista than the Carioca?” His aim, therefore, was to define, through a series of contrasts, the Paulistas, the Brazilians and the Cariocas. The Brazilian was seen as less theoretical than other Latin Americans, and:

between the two most important intellectual metropolises, São Paulo and Rio, we can also note something of this difference in attitude. Since Modern Art Week [in 1922], São Paulo has presented itself to Rio as a centre driving forward aesthetic ideas and theories. Modernism was not born in Pauliceia Desvairada [Mário de Andrade’s collection of poems] alone, but its doctrine, its theory, was defined and codified in it (Pedrosa, 2004: 253).

A considerable contrast exists between this text and a lecture that Pedrosa gave in 1952 on Semana de 1922. In the lecture, there was no reason to differentiate between Rio and São Paulo, and modernism was seen to have arrived in the country via the São Paulo capital, when the visual arts, especially the works of Anita Malfatti and Brecheret, revealed to the literati (especially Mário de Andrade) a phenomenology of Brazil. In the 1952 lecture, Pedrosa (2004: 143) asserts that “the Brazil of Mário de Andrade enters through the senses. Hence its plastic and concretizing force”. His poetry was filled with an “extraordinary plastic and chromatic vigour from the evocation of Brazilian nature. His palette would recall the vivid tones of fauvism and the violence of pure colour of Van Gogh”. Mário de Andrade figured, then, as the poet of a “direct Brazil - natural, anti-ideological” (Pedrosa, 2004: 144). But by 1957, in the text “Paulistas e cariocas,” Mário de Andrade had become an ideologue of modernism who interspersed his books of poetry with books of ‘wisdom’ (sabença). And the Cariocas, in contrast to the Paulistas, were “more empirical, or maybe the sun and sea induced in them a certain doctrinal neglect” (Pedrosa, 2004: 256). In 1957, Pedrosa situated Rio de Janeiro in a metonymic position of the Brazil that had previously been revealed by Anita Malfatti and Brecheret. The history of Brazilian modernist art thus became detachable from São Paulo’s modernism. “Modernism was not born in Pauliceia Desvairada, but its doctrine, its theory, was defined and codified in it” (Pedrosa, 2004: 253). Volpi is described as exception among the Paulistas. And Pedrosa (2004: 254) calls him “the already glorious old master,” “who bestows the youths of concretism with the generous and protective gesture of his solidarity.” In the same stroke, therefore, São Paulo lost its central role, its position as a spearhead in the history of national art, and Volpi became associated with a Brazilianness in solidarity with the Carioca artists.

Pedrosa did not stop there. That same year he organized a Volpi retrospective at Rio’s Museum of Modern Art (MAM-Rio). This show was closely accompanied by the newspaper Jornal do Brasil in which Pedrosa wrote. In its pages, the show was announced as an event of supreme importance for the Rio art world. The exhibition opened on June 12th and the critic organized an intense program of talks, debates and interviews with all the events reproduced or commented on in the newspaper. Accompanying this process and the tensions that it generated with the other critics, we can witness a revision of the nation’s art history. Pedrosa ousts from the pinnacle of admiration the affiliates of the Paulista modernism of the 1920s - Segall, Di Cavalcanti and principally Portinari - and, in place of the modernists, proclaims Volpi. The catalogue of this retrospective, written by Pedrosa (2004: 261-270), starts by echoing the essay “Paulistas e cariocas” and describes the artist as “more than a Paulista”; according to Pedrosa, the painter of facades was “from Cambuci.” In this presentation, what is external to the painter’s local neighbourhood is not the city of São Paulo, but the “cosmopolitan centre of the city, for Rio and for Brazil, and even for the world beyond.” Moreover, Semana de 1922 was, according to the critic, an event of which Volpi had been unaware and which had taken place - the author is keen to emphasize - in the São Paulo Municipal Theatre. In other words, in São Paulo’s city centre. “Neither Volpi, the decorator, knew of the existence of those great cosmopolitan names of intellectuals and artists, nor did they know of the existence of the glorious plebeian of Cambuci” (Pedrosa, 2004: 264).

In this catalogue, Volpi is given the epithet “the insular artist of Cambuci” and Pedrosa concludes the text by placing him among the Cariocas: “Cariocas, my brothers, here is Volpi.” He adds: “Thank the Museum of Modern Art for presenting him. Posterity will remember his name. He is the master of our era.” In its own way, the show, a retrospective, was a reassembling and refounding of this history of national art. Volpi’s work gathered in the exhibition covered the period between 1924 and 1957 - that is, practically the entire history of Brazilian modern art. In the catalogue, Pedrosa (2004: 264) makes this explicit:

Volpi’s art retains all the marks of this evolution. Over the long years of honest and efficient work in the profession, he naturally passed, without knowing how, through all the phases of modern painting, from impressionism to expressionism, from fauvism to cubism, to abstractionism.

This new narrative of Brazilian art, recounted by Pedrosa, was only able to develop thanks to the liminality that Volpi had acquired. By isolating himself in Cambuci, he became independent of Semana de 1922. Moreover, it was his proletarian and artisanal status, described earlier by Mário de Andrade in São Paulo, that provided the driving force to this history:

while in its current phase, where the love of the old materials remains and perhaps the final preference for tempera (without mentioning the fondness for the wall itself), his art is no longer adapted to the artisanal styles of the civil construction of his youth, so it proves, though the true schools of a painter are not the academies of fine arts or the specialized schools (far removed from the world of work and production), but the industrial apprenticeship of his era. [...]

However, he managed to reach the apex of modern evolution, starting out from the trade of wall decorator. Perhaps this explains how he managed to keep the purity, the artistic ingenuity, the dramatically precarious and rich manual fabrication of his material, even in the most abstract or ‘concrete’ compositions of his last phase (Pedrosa, 2004: 265-267).

The person who first came out in opposition to Pedrosa was an old collaborator of Mário de Andrade, the Paraiban writer Antônio Bento (1902-1988), who in the past had conducted research on folkloric music for the poet of Pauliceia and who had already written on Portinari. Bento (1957a: n.p.)Bento, Antônio (1957a). A retrospectiva de Volpi. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro. praised “the excellent organization of this retrospective,” but declared himself unable to “include [himself] in the choir of those chanting a song of exalted and even excessive admiration for the painter.” And while the concretists presented Volpi “as the greatest Brazilian artist” and “the master of his era,” for Antônio Bento this claim did not have “the least critical value, since it is biased in the extreme.” Mário de Andrade’s collaborator believed that ahead of Volpi were “Portinari and Segall, Di Cavalcanti and Guignard.” Even in the field of concrete art, it was necessary to consider “the work of Milton Dacosta superior to that of Volpi, who has almost nothing to say in the abstract language.”

From what may be ascertained from the irreducible characteristics of his art, Volpi is a primitivist or popular painter. He cannot, therefore, aspire to a more advanced position in the hierarchy of the currents of avant-garde art in Brazil (Bento, 1957aBento, Antônio (1957a). A retrospectiva de Volpi. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro.: n.p.).

Antônio Bento’s argument was two-fold. On one hand, he reaffirmed the canons of the history of modernism and, on the other, situated Volpi far from the avant-garde. Mário Pedrosa was depicted by Bento as emotional, sentimental, possessing a problematic stance in terms of the role that a critic should perform. Antônio Bento, on the contrary, thought of himself as a shrewd critic, capable of discerning all the issues involved in an aesthetic judgment. Pedrosa replied to Bento two days later in the Jornal do Brasil. In the article “O mestre brasileiro de sua época” (The Brazilian master of his era) (Pedrosa, 2004: 271-276), he affirmed that admiration was not a critical attitude but a normative one. Equally normative was Bento’s attitude of placing other painters ahead of Volpi. Pedrosa (2004: 274) again insisted on Volpi’s exceptionality:

Only this symbiosis, perfectly realized (as Volpi’s harsh critic recognizes), combining a rigorous abstract composition with the lyricism of the lively singing colours of the popular houses of the interior, is for us an artistic event of the highest order; it is, in effect, a creation original in all contemporary painting. This is why, among other reasons, Volpi can be considered ‘the Brazilian master’ par excellence. His pictorial language is modern and universal, however, which is also why his show represents Brazilian painting’s cry of independence in the face of international painting and the Paris School.

The polemic rolled on. Antônio Bento (1957b: n.p.)Bento, Antônio (1957b). O mestre brasileiro de sua época. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro. on June 23rd published a homonymous text to Pedrosa in the Diário Carioca in which he denied rejecting Volpi passionately, “but sought merely to demonstrate that he was not ‘the master of his time’ nor ‘the Brazilian master.’” For Bento, the artists was merely a great painter in his own specific field, having achieved among it and it alone “a leading place in the panorama of national painting.” It was a question of putting Volpi in the “right place.” Antônio Bento stressed that had he denied this “position occupied by the artist, then yes, it would have been passionate or tendentious.” The focal point of this new text was to contest two claims made by Mário Pedrosa: “The first relates to the importance of the Volpi Retrospective,” which, according to Pedrosa (2004: 274), represented “Brazilian painting’s cry of independence in the face of international painting and the Paris School.” For Bento (1957b: n.p.)Bento, Antônio (1957b). O mestre brasileiro de sua época. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro. this claim did not match reality since

there is no one who can see Volpi as the Dom Pedro I of modern Brazilian painting. On the contrary, save for the phase of urban landscapes and the facades of colonial houses, there is nothing in Volpi’s painting that is representative of Brazil. [...] Subtract the paintings from this period and Volpi ceases to be one of our painters, and might appear to be a representative of any European country.

Thanks to his façade phase, Antônio Bento argues, Volpi had been elevated to the pantheon of national artists. In announcing this, the critic proclaims his own aptitude to assess Volpi’s position. For Bento, while the painter of facades was not the country’s greatest artist, he was still one of the greatest. The second claim that he attributes to Pedrosa is the imputation to Volpi of a leading role in bringing “contemporary Brazilian painting from ‘impressionism to the more recent visual concerns.’” This judgment was erroneous in Bento’s (1957b: n.p.)Bento, Antônio (1957b). O mestre brasileiro de sua época. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro. view:

This has been happening in Brazil since the Modern Art Week of 1922, with the role of pioneers belonging to Anita Malfati, Tarsila, Segall and Di Cavalcanti. After came Portinari who, to Brazil’s credit, is has entered the dictionaries and books of history and criticism on modern painting at international level.

In this text, Antônio Bento makes it clear that the question was where Volpi should be situated within Brazilian history. The artist could not be discredited, he already belonged to the pantheon. The interlocutor was Pedrosa (and, by extension, the concretists), the motive of discussion was the official narrative of Brazilian art, and the central elements to the plot were the landscapes of Volpi that merged popular imagery (of the suburban neighbourhoods) with the concretist ideology, and thus opened the way for critics to revise the nation’s art history.

This tension led Pedrosa and the concretists to assume, against their rivals, a stance located somewhere between playful banter and violence. On the same day that Antônio Bento published his second response to Pedrosa, the Sunday supplement of the Jornal do Brasil published a strange survey under the title “Volpi on the Spot,” in which the concretists discussed why they considered to be “fools those who don’t like Volpi.” Near the top of the page, in bold letters, the article reported: “Mário Pedrosa, in the course of a debate on Volpi’s work: if anyone here dislikes these paintings, they’ll be booted out.”

The person to rise up against Pedrosa and the concretists was a participant of Modern Art Week, the renowned poet and art critic Manuel Bandeira. On June 29th he published the text “Volpi” in the Jornal do Brasil:

In politics there are the golpistas [coup plotters]; in painting the volpistas. The Volpi retrospective was the November 11th of the visual arts: a junta headed by Mário Pedrosa, Ferrabrás the big supporter, then Portinari in the presidency and the investiture of good old Alfredo Volpi, the Italo-Brazilian from Cambuci (Bandeira, 1957Bandeira, Manuel. (1957). Volpi. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.: n.p.).

Bandeira claimed to have liked the Volpi exhibition and this fact was, he declared, something of a relief given the concretists’ diagnosis of those unenamoured of the painter. Stating that he did not consider Volpi ‘the master’ but rather ‘a master,’ Bandeira was not so bold as to attack the painter. On the contrary, he indirectly restated the traits of the artist’s personality already identified and praised them:

I trust that Volpi will understand me. He is such a nice little old guy!

I think Volpi himself must have smiled when one of his tremendous admirers decreed that he, Volpi, was “Brazil’s first great painter, the greatest painter of the Americas and one of the greatest in the world.” Other golpistas or volpistas even decreed that he was the first Brazilian painter and his painting ‘the first manifestation of an authentically Brazilian art.’ Now this transforms the excellent Volpi into a dead cat to slap in the face of Portinari, Di and other poor foreign daubers. It is a lack of respect, not of Portinari and Di, but of Volpi himself. Volpi, be wary of your jaguar friends: they never sleep (Bandeira, 1957Bandeira, Manuel. (1957). Volpi. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.: n.p.).

Pedrosa (1957b)Pedrosa, Mário. (1957b). “O mestre”, apesar dos amigos. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro. replied to Bandeira admitting that the jokes had been in bad taste and explained that the goal had been to lighten the atmosphere, both in the debate where he had threatened to boot people out and at the dinner in Lygia Clark’s house where the survey testimonies had been collected. As for the centre of the debate, ‘the coup,’ Pedrosa pondered:

if we consider Volpi ‘greater’ than Segall, this does not mean detracting from the worth of the latter, but, on the contrary, despite the great and authentic value that we recognize in him as a painter. [...] Who also can deny the importance of Portinari and above all his unparalleled historical significance in the development and triumph of modern art in Brazil? Nonetheless, we ‘volpistas’ are absolutely certain that Volpi, as a painter, is much greater than the glorious master of the murals of the Ministry of Education. As for Di, our old Di, he has the temperament of a painter even below water. He has a safe place - and an important place - in the history of Brazilian painting. His work, however, does not have the completeness of Volpi’s work, nor its development and depth. Despite his great talent, Di was led by his temperament to make a separation between life and painting and frequently sacrificed painting for life. With Volpi, though, life and painting are one and the same thing (Pedrosa, 1957bPedrosa, Mário. (1957b). “O mestre”, apesar dos amigos. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.: n.p.).

Mário Pedrosa, at the same time as dedicating himself to Volpi’s exhibition and critical review of the show, also insisted on defending the painter from all opponents. The commitment of this intellectual reveals the central importance of Volpi to his artistic and national project. Pedrosa was not just toppling the old canons, he was turning Volpi into the line of history: the painter described by Pedrosas had lived the entire history of modern art and, through his work, had merged sensibility to the suburb with his (artisanal) technique. This made him an artist who Pedrosa deemed exemplary, someone from whom the new generations should draw inspiration. The critic advised younger painters to learn from Volpi the lesson of humility, to be modest and learn from everyday folk and the anonymous (Pedrosa, 1957aPedrosa, Mário. (1957a). Volpi, uma lição de ética. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.). In 1958, in the article “Problemas da pintura brasileira” (Problems of Brazilian painting), Pedrosa (2004: 299-300) commented enthusiastically on a visit to the atelier of Djanira. The critic writes that the artist’s landscapes left him reflecting on the ‘genial development’ of this genre in Volpi. In his article, Pedrosa discerns a parallel between Djanira, Volpi and other Brazilian painters in relation to landscape painting. Then too it was a question of identifying a visual Brazilianness and positioning himself as the teller of a history that would continue to unfold in the future:

The visual transposition that may result from this contains the possibility of a general, phenomenological interpretation of our things and our nature. This cannot fail to have a deeper, more permanent and transcendental meaning for the formation of a collective sensibility and the definition of our spiritual and aesthetic physiognomy, or perhaps, in sum, despite being delayed in historical time, at global level, of a Brazilian school (Pedrosa, 2004: 300).

Volpi needed a critic to narrate the history created by himself in the form of pictures - something impossible from the position of artist. The master of Cambuci, in counterpart, offered the possibility of imagining a Brazilianness distinct from the one that typically shaped the official narratives. Volpi had been a balm for an exiled activist recently returned to the country, as he had been too for those artists clamouring for their own place in the sun. Isolated by his own mythology from the cosmopolitan centres, the painter forged images that drew from the national scenery and opened up an alternative to the official ideology. Describing Volpi, narrating his history and analysing his work meant, in the mid-twentieth century, bringing past and future into alignment. Isolated in the suburb, the master was the present. Artists should live in the shadow of his figure and, only in this space, could they then lay claim to tomorrow.

-

1

Volpi Institute Cultural Support 2017. My thanks for the cultural support received from the Alfredo Volpi Institute of Modern Art, a nonprofitmaking institution with legal responsibility for the preservation and divulgation of the painter’s memory and artistic work, especially for recognizing the importance of this initiative for making the artist more widely known and discussed in the academic sphere.

-

2

Another perspective is developed by Patrícia Reinheimer (2013: 16-17)Reinheimer, Patrícia. (2013). Candido Portinari e Mário Pedrosa: uma leitura antropológica do embate entre figuração e abstração no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Gramond. who, comparing Portinari and Pedrosa, identifies a ‘non-linearity’ of a “process of axiological and epistemological transformation” in the Brazilian art world after the Second World War. Changes that, according to this author, were “as radical as those instituted by romanticism in Europe through the reformulation of ideas of the artist and modern art.”

-

3

The São Paulo world of literate culture proved hostile to the enormous contingent of first and second generation immigrants in the city, as Pontes & Miceli (2014)Pontes, Heloísa & Miceli, Sérgio. (2014). Figuração em cena da história social. In: Cultura e sociedade: Brasil e Argentina. São Paulo: Edusp. demonstrate. The visual arts, by contrast, presented themselves as a space strongly marked by their presence, a fact perceptible in the works of Freitas (2011)Freitas, Patrícia Martins Santos. (2011). O Grupo Santa Helena e o universo industrial paulista (1930-1970). Master’s Dissertation. PPGH/Universidade Estadual de Campinas., Brill (1984)Brill, Alice. (1984). Mário Zanini e seu tempo. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. and Belluzzo (1988)Belluzzo, Ana Maria de Moraes. (1988). Artesanato, arte e indústria. Doctorate Thesis. Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo/Universidade de São Paulo., in which we can also note morphological characteristics of the São Paulo intellectual world in contrast to that of Rio, as Carvalho (2003)Carvalho, José Murilo de. (2003) [1988]. Aspectos históricos do pré-modernismo brasileiro. In: (Vários Autores). Sobre o pré-modernismo. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa. shows.

-

4

The relationship between Volpi and Italian modernist art is explored in Rosa (2015)Rosa, Marcos Pedro. (2015). O espelho de Volpi: o artista, a crítica e São Paulo nos anos 1940 e 1950. Master’s Dissertation. PPGAS/Universidade Estadual de Campinas.. I highlight, however, the similarity that this author identifies between some of Volpi’s canvases and others by the Italian modernist painter Carlo Carrà (whose work was included in the exhibition of Italian art held in 1937). I also emphasize the similarity between some of Volpi’s paintings and certain frescos by Giotto, Piero della Francesca and Margaritone d’Arezzo, who were celebrated by Carrà and other painters of the period as examples of a supposed ‘Mediterranean genius’: the pre-Renaissance painters were thus reference points for the generation of Italian artists committed to the return to order.

-

5

The process of ‘Brazilianization’ of the generation of Paulista painters to which Volpi belonged is described by Rosa (2015: 49-77)Rosa, Marcos Pedro. (2015). O espelho de Volpi: o artista, a crítica e São Paulo nos anos 1940 e 1950. Master’s Dissertation. PPGAS/Universidade Estadual de Campinas..

-

6

Portinari had been chosen to paint the murals of the Ministry of Education in Rio de Janeiro and those of the Library of Congress in Washington - a federal capital presided over by Getúlio Vargas, the other by Roosevelt. On Portinari’s position vis-à-vis the governments of the period, an interesting debate is developed by Aracy Amaral (2003: 242)Amaral, Aracy. (2003). Arte para quê? A preocupação social na arte brasileira 1930-1970. São Paulo: Editora Nobel. in which describes Portinari as “the official painter” of the Vargas government. Anna Teresa Fabris (1990)Fabris, Ana Teresa. (1990). Portinari: pintor social. São Paulo: Edusp., for her part, situates him in his historical context, demonstrating, for example, the dissonance between the idea of the people in Portinari’s work and in the Vargas campaigns. Subsequently, Marcelo Mari (2006)Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo. returns to this debate, recognizing Fabris’s protest against Amaral’s claims, but nonetheless recalling the political uses that the Vargas government made of Portinari’s works.

-

7

Maria de Fátima Morethy Couto (2004: 70-71)Morethy Couto, Maria de Fátima. (2004). Por uma vanguarda nacional. Campinas: Editora Unicamp. sketches an interesting panorama of the Brazilian avant-garde. In her book, she reaffirms the first and second São Paulo biennales as landmarks in the consolidation of abstract art in the country and comments on the prize awarded to Volpi. While this demarcation is regularly found in historiography, her work is especially interesting since it shows how this historiography can be traced back to Mário Pedrosa himself.

-

8

“It should be said, in any case, that Volpi’s adherence to concrete poetics was never unconditional, nor did it represent a fracture in the evolution of his language. Like the concrete poems of Manuel Bandeira, which are almost always love poetry, the best concrete paintings of Alfredo Volpi express not so much the search for objectivity as the demureness of a subjectivity that, by way of purification, turns into geometric form. They are not ideas that became realities, but realities that became ideas” (Mammì, 2006Mammì, Lorenzo. (2006). Volpi. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.: 33). For a discussion of the concretist period in Volpi, see too Naves (2008)Naves, Rodrigo. (2008). A complexidade de Volpi: notas sobre o diálogo do artista com concretistas e neoconcretistas. Novos Estduos Cebrap, 8, São Paulo, p. 139-155..

-

9

On the gravitation of New York intellectuals around the Partisan Review, see Cooney (1986)Cooney, Terry. (1986). The rise of the New York intelectuals: Partisan Review and its circle. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. and Pontes (2003)Pontes, Heloísa. (2003). Cidades e intelectuais: os ‘nova-iorquinos’ da Partisan Review e os ‘paulistas’ de Clima, entre 1930 e 1950. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 18/53, p. 33-52..

-

10

The terms Carioca and Paulista refer to the inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, respectively.[T.N.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Amaral, Aracy. (2006). Textos do Trópico de Capricórnio São Paulo: Editora 34.

- Amaral, Aracy. (2003). Arte para quê? A preocupação social na arte brasileira 1930-1970 São Paulo: Editora Nobel.

- Andrade, Mário de. (1971) [1944]. Ensaio sobre Clovis Graciano. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, 10, p 156-175.

- Andrade, Mário de. (1941a). Um salão de feira 1. Diário de São Paulo, São Paulo.

- Andrade, Mário de (1941b). Um salão de feira 2. Diário de São Paulo, São Paulo.

- Arantes, Otília. (2004a). Mário Pedrosa: Acadêmicos e modernos São Paulo: Edusp.

- Arantes, Otília. (2004b). Mário Pedrosa: itinerário crítico. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

- Bandeira, Manuel. (1957). Volpi. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.

- Belluzzo, Ana Maria de Moraes. (1988). Artesanato, arte e indústria Doctorate Thesis. Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo/Universidade de São Paulo.

- Bento, Antônio (1957a). A retrospectiva de Volpi. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro.

- Bento, Antônio (1957b). O mestre brasileiro de sua época. Diário Carioca, Rio de Janeiro.

- Botelho, André & Hoelz, Maurício. (2016). O mundo é um moinho: sacrifício e cotidiano em Mário de Andrade. Lua Nova, 97, São Paulo, p. 251-284.

- Brill, Alice. (1984). Mário Zanini e seu tempo São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva.

- Brito, Ronaldo. (2007). Neoconcretismo: vértice e ruputra do Projeto Construtivo Brasileiro. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

- Carvalho, José Murilo de. (2003) [1988]. Aspectos históricos do pré-modernismo brasileiro. In: (Vários Autores). Sobre o pré-modernismo Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa.

- Chiarelli, Tadeu. (2007). Pintura não é só beleza: a crítica de arte de Mário de Andrade Florianópolis: Letras Contemporâneas.

- Chiarelli, Tadeu (2003). L’Italia è qui: uma prezentazione. In: Chiarelli, Tadeu & Weschsler, Diana B. Novecento sudamericano: relacione artistiche tra Italia, Argentina, Brasile e Uruguai. Milano: Milano Skira.

- Cooney, Terry. (1986). The rise of the New York intelectuals: Partisan Review and its circle Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Cordeiro, Waldermar. (1952). Volpi, o pintor de paredes que traduziu a visualidade popular: o rapazola que comprou uma caixa de aquarelas usadas - Nas mansões servia ao cosmopolitismo, mas amava os coloridos do subúrbio. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo.

- Fabris, Ana Teresa. (1990). Portinari: pintor social. São Paulo: Edusp.

- Fagone, Vittorio. (1978). Carlo Carrà: tutti gli scritti a cura di Massimo Carrà Milano: Feltrinelli.

- Freitas, Patrícia Martins Santos. (2011). O Grupo Santa Helena e o universo industrial paulista (1930-1970) Master’s Dissertation. PPGH/Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

- Guilbaut, Serge. (1985). How New York stole the idea of modern art Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hoffmann, Ana Maria Pimenta. (2002). A arte brasileira na Segunda Bienal do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo: o Prêmio Melhor Pintor e o debate em torno da abstração Master’s Dissertation. PPGH/Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

- Homem, Maria Cecília Naclércio. (1984). O prédio Martinelli, a ascensão do imigrante italiano e a verticalização de São Paulo São Paulo: Editora Projeto.

- Mammì, Lorenzo. (2006). Volpi. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

- Mari, Marcelo. (2006). Estética e política em Mário Pedrosa (1930-1950). São Paulo: Doctorate Thesis. PPGF/Universidade de São Paulo.

- Mariani, Valerio. (1937). Introdução. In: Mostra D’Arte del Padiglione d’Italia São Paulo: Commissariato italiano per L’espozicione di San Paolo del Brasile.

- Morethy Couto, Maria de Fátima. (2004). Por uma vanguarda nacional Campinas: Editora Unicamp.

- Moura, Flávio Rosa de. (2011). Obra em construção: a recepção do neocentrismo e a invenção da arte contemporânea no Brasil Doctorate Thesis. PPGS/Universidade de São Paulo.

- Naves, Rodrigo. (2011). A forma difícil: ensaios sobre arte brasileira. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Naves, Rodrigo. (2008). A complexidade de Volpi: notas sobre o diálogo do artista com concretistas e neoconcretistas. Novos Estduos Cebrap, 8, São Paulo, p. 139-155.

- Pedrosa, Mário. (1957a). Volpi, uma lição de ética. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.

- Pedrosa, Mário. (1957b). “O mestre”, apesar dos amigos. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.

- Pierre, Arnaud. (2009). Calder: mouvement et realité Paris: Hazan.

- Pignatari, Décio. (1957). Ferreira Gullar entrevista Décio Pignatari. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.

- Pontes, Heloísa. (2003). Cidades e intelectuais: os ‘nova-iorquinos’ da Partisan Review e os ‘paulistas’ de Clima, entre 1930 e 1950. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 18/53, p. 33-52.

- Pontes, Heloísa. (1998). Destinos mistos São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Pontes, Heloísa & Miceli, Sérgio. (2014). Figuração em cena da história social. In: Cultura e sociedade: Brasil e Argentina São Paulo: Edusp.

- Read, Herbert. (1953). Sir Herbert Read fala da participação brasileira na Bienal e do abstracionismo em geral. (Entrevista concedida a Ivone Jean.) Folha da Manhã, São Paulo.

- Reinheimer, Patrícia. (2013). Candido Portinari e Mário Pedrosa: uma leitura antropológica do embate entre figuração e abstração no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Gramond.

- Rosa, Marcos Pedro. (2015). O espelho de Volpi: o artista, a crítica e São Paulo nos anos 1940 e 1950 Master’s Dissertation. PPGAS/Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

- Salmoni, Anita & Debenedetti, Emma. (1981). Arquitetura italiana em São Paulo São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva.

- Salzstein, Sônia. (2000). Volpi Rio de Janeiro: Campos Gerais.

- Vieira, José Geraldo. (1955). O urbanismo lírico de Alfredo Volpi. Folha da Manhã, São Paulo.

- Villas Bôas, Glaucia Kruse. (2014). Estética da ruptura: o concretismo brasileiro. VIS: Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arte da UnB, 13.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Sep-Dec 2018

History

-

Received

29 Nov 2016 -

Reviewed

05 May 2017 -

Accepted

09 Aug 2017

Ladi Biesus Collection: Salztein, 2000: 110

Ladi Biesus Collection: Salztein, 2000: 110

Tito Enrique da Silva Neto Collection:

Tito Enrique da Silva Neto Collection:  Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Centre Pompidou, Paris.