Abstract

This article aims to discuss the foundation of the State Museum of Goiás and its relationship with the dissemination of the idea of the frontier of Central Brazil as a region of economic potential with natural resources to be exploited. The research is based on a diverse set of archival and bibliographic sources that describe and contextualize the museological exhibitions and objects in the context of the March to the West, and the relationship of cultural events with other institutions and the discourses of the occupation of the frontier. The archival sources highlight the role played by the first director of the Museum, Zoroastro Artiaga, and his political maneuverings to have the Institution selected as a vehicle for the dissemination of Geosciences and, especially, as a place to promote the natural resources of Goiás. The research also demonstrates that the museological intentions of constructing a collection of objects about the natural history of the Cerrado was more to advance the idea of the frontier of Central Brazil than to collect elements for the exhibition or for scientific research about Goiás’ natural resources.

Keywords:

Natural Museum of Goiás; Frontier; Natural History; Natural Resources

Resumo

Este artigo tem por objetivo apresentar a criação do Museu Estadual de Goiás e a sua relação com a divulgação da fronteira do Brasil Central como a região de potencialidades econômicas e de exploração dos seus recursos naturais. A pesquisa se baseou em coleta de fontes documentais e outras referências que contextualizam as exposições e objetos museológicos no contexto da Marcha para o Oeste, e a relação dos eventos culturais com outras instituições e os discursos de ocupação da fronteira. As pesquisas documentais evidenciam o papel exercido pelo primeiro diretor do Museu, Zoroastro Artiaga, e suas articulações políticas para eleger a instituição como veículo de divulgação das Geociências e, principalmente, como local de divulgação das riquezas naturais de Goiás. Também reforça que as intenções museológicas de construir uma coleção de objetos de história natural do Cerrado tinham interesses mais em divulgar a fronteira do Brasil Central do que compor elementos de exposição e pesquisa científica sobre os bens naturais de Goiás.

Palavras-chaves:

Museu Estadual de Goiás; fronteira; história natural; recursos naturais

Introduction

Studies of the Goiás sertão, or more precisely papers related to the category of frontier present the economic and demographic expansion of the territory based on a relationship between the colonizer and the environment in which availability of natural resources is the primary element for movements of recognition, exploration, and settlements (Evans; Dutra and Silva, 2017EVANS, Sterling; DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. Crossing the Green Line: frontier, environment and the role of bandeirantes in the conquering of Brazilian territory. Fronteiras: Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science, vol. 6, n. 1, p.120-142, 2017.). Following Hennessy (1978)HENNESSY, Alistair. The Frontier in Latin American History. Londres: Edward Arnold, 1978., the Latin American frontier in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries can be seen as having been marked by processes of occupation through the mining frontier and cattle frontier, in which even when integrated in the Brazilian economic system, during this period archaic structures, sociability remained in the distant Planalto Central (Central Plateau) of Brazil (Palacin, 1994PALACÍN, Luis. O século do ouro em Goiás: 1722-1822, estrutura e conjuntura numa capitania de Minas. Goiânia: Ed. da UCG, 1994.; McCreery, 2006McCREERY, David. Frontier Goiás, 1822-1889. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.; Karasch, 2016KARASCH, Mary C. Before Brasília: Frontier Life in Central Brazil. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2016.).

During the twentieth century a new process of frontier occupation in Central Brazil sought to breach its isolation through the integration and expansion of the road and rail network, which led to new migratory waves, characterized by agrarian development and urban expansion projects. The modernization process was more striking from the 1930s onwards, with the creation of a new state capital (1933) and the conclusion of the Goiás Railway, which reached Anápolis station in 1935 (Borges, 1980BORGES, Barsanufo G. O despertar dos dormentes. Goiânia: Ed. UFG, 1980.; Campos, 2012CAMPOS, Francisco Itami. Questões agrárias: bases sociais da política goiana. Goiânia: Kelps, 2012.; Dutra e Silva, 2017DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017.).

At the end of the 1930s and in the first half of the 1940s, new modernization and integration processes involving Goiás and the principal economic centers of the country were favored by what was known as the Marcha para o Oeste (March to the West) (Lenharo, 1986LENHARO, Alcir. Sacralização da política. Campinas: Papirus, 1986.). In the process of agricultural modernization, the creation of the National Agricultural Colony of Goiás in 1941 distributed lots of rural land, propelling a migratory wave for agricultural colonization. In addition, the development of rural areas rather than the opening of roads and the railway propelled commerce and cultural development in Goiás, principally in Anápolis and Goiânia (Carmin, 1953CARMIN, Robert Leighton. Anápolis, Brazil: regional capital of an agricultural frontier. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago, Departament of Geography, Research Paper, n. 35, Dec. 1953.; Dutra e Silva; Bell, 2018DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro; BELL, Stephen. Colonização agrária no Brasil Central: fontes inéditas sobre as pesquisas de campo de Henry Bruman em Goiás, na década de 1950. Topoi (Rio Janeiro), vol. 19, n. 37, p.198-225, 2018.; Dutra e Silva, 2017DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017.).

The Marcha para o Oeste played a significant role in the economic integration process in Goiás. It was also an important symbolic element which sought to redefine the cultural profile of the state, breaking away from the idea of the isolated and hostile sertão and replacing this with a new Eldorado in the Planalto Central of Brazil. This modernization project was accompanied by cultural elements based on the redefinition of the image of the state’s territory. The term Oeste (West), widely used to describe the new agricultural frontier,1 1 In relation to the expansion process of the agricultural frontier in Goiás, other forms of frontier can be considered, following Hennessy’s model (1978) of the occupation process of these spaces in Latin America. In Goiás, the agricultural expansion process followed a distinct path due to a number of variables. As shown by Teresa Cribelli (2016), the agricultural modernization process in Brazil originated in the nineteenth century, considered by her as a ‘conservative modernization’ process, based on the technological advance and the maintenance of the social order. In the case of Goiás, the expansion of the agricultural frontier occurred even later, as a distinct form of adaptation to the conservative modernization model, CAMPOS (2012). Agriculture was dependent on logistical integration with the rest of the country, which commenced in Goiás in the first half of the twentieth century, BORGES, (1980). McCreery (2006) reinforces this model with research on the role of livestock in the Goiás economy in the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. For him, cattle were the principal form of integration between Goiás and the rest of the country, since cattle were a type of good that transported itself. He also states that until the arrival of the railway, Goiás was the ‘frontier of the frontier,’ due to its geographic position in the central chapadões of Brazil — as it was difficult to access and its isolation was more than geographic, being also political, territorial, and economic. At the same time the classic work of Warren Dean (1996) shows that the expansion practices of the agricultural frontier in Brazil were associated with the availability of tropical forests, in adherence to the archaic model of slash and burn agriculture. In the case of Goiás, the process of the expansion of the agricultural frontier (which as previously stated only occurred in the first half of the twentieth century) was strongly associated with the dynamic of railway expansion, which connected the region with the productive centers. In this sense, the work of Dutra e Silva (2017) adds to Dean’s work (1995), by considering the forested region of Mato Grosso de Goiás as the privileged locus of agricultural expansion policies in the 1930s and 1940s which preceded the agricultural occupation of the Cerrado. In relation to this, see also: WAIBEL (1947; 1948); JAMES (1953); GIUSTINA; DUTRA E SILVA; MARTINS (2018). was the symbolic element which sought to demystify the misrepresentations of the sertão with the space being inverse to the civilized one. The civilizing process brought new symbols and the replacement of the term sertão by Oeste was much more than a conceptual change.2 2 Dutra e Silva (2017) shows how the documentation used in the 1930s, above all during the Estado Novo (1937-1945), came to use expressions such as frontier, hinterland and above all Oeste (West). The category Oeste was much more than a symbolic element demarcating a geographic region. It came to represent a symbolic category which presented the agrarian as a social space of prosperity, the land of promise. He bases his work on different documentary sources, such as reports, essays, and political speeches, amongst others, which use this rhetoric. At the same time there exists a weakening of the category sertão, practically abandoned and replaced during the Estado Novo by new symbolic elements of the territory, which divulged a colonization and migration project not for the sertão, but in a march towards the West, that was both geographic and symbolic. It was an ideological transformation, much more profound than just delineating the new process of demographic expansion and territorial occupation of the Brazilian hinterland (Dutra e Silva, 2017DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017.). It was not a Marcha para o Sertão, rather a Marcha para o Oeste, part of a new modernizing project, in which the discourse and other propaganda resources about the frontier of Goiás indicate this territory as being a new space of Brazilianness, since it was a symbolic return to the Bandeirante pioneers (Dutra e Silva et. al, 2014DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro; TAVARES, Giovana Galvão; SÁ, Dominichi Miranda de, FRANCO, José Luiz de Andrade. Fronteira, História e Natureza: a construção simbólica do Oeste Brasileiro (1930-1940). HIb. Revista de Historia Iberoamericana, vol. 7, n. 2, p.1-23, 2014.; Evans; Dutra e Silva, 2017EVANS, Sterling; DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. Crossing the Green Line: frontier, environment and the role of bandeirantes in the conquering of Brazilian territory. Fronteiras: Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science, vol. 6, n. 1, p.120-142, 2017.).

It is important to take into account how processes and concepts as fundamental for US historiography, such as frontier, hinterland, wilderness, amongst others, became part of the intellectual and political language of Brazil, especially between the 1930s and 1950s. Taking as a reference the Western History produced in the United States (Turner, 2010TURNER, Frederick Jackson. The Frontier in American History. Mineola, Nova York: Dover Publications, 2010.; White, 1991WHITE, Richard. It’s your Misfortune and None of my Own: a new history of the American West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991., 1997WHITE, Richard. Western History. Washington: American Historical Association, 1997.; Worster, 1985WORSTER, Donald E. Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity and the Growth of the American West. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985., 1991WORSTER, Donald E. Beyond the Agrarian Myth. In: LIMERICK, Patricia Nelson; MILNER II, Clyde A. & RANKIN, Charles E. (org.). Trails: Toward a New Western History. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1991., 1992WORSTER, Donald E. Under Western Skies: Nature and History in the American West. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.; Cronon, 1991CRONON, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1991.), Brazilian intellectuals and ideologues from this period sought to construct an image of a Western frontier as a promised land (Evans; Dutra e Silva, 2017EVANS, Sterling; DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. Crossing the Green Line: frontier, environment and the role of bandeirantes in the conquering of Brazilian territory. Fronteiras: Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science, vol. 6, n. 1, p.120-142, 2017.; Dutra e Silva, 2017DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017.). In this way a set of characters, narratives, languages, and other cultural elements came to represent the frontier in Central Brazil, whose attributes were based on symbolic and mythical representations, following an interpretative model used in the United States, well presented by Smith (2009)SMITH, Henry Nash. Virgin Land: the American West as Symbol and Myth. Cambridge, Massachusetts/Londres: Harvard University Press, 2009. in his classic work.3 3 There exists a set of published works which use a comparative model in a conceptual manner and historical processes in themselves, related to the frontier in Brazil and the United States. I highlight here the works of Viana Moog (1964), Pierre Monbeig (1998), and Sergio Buarque de Holanda (1995) as representative works in the use of the category of frontier and wilderness in studies about the relationship between society and nature in Brazil. More recently, I would like to highlight the work of Janaina Amado, Walter Nugent, and Warren Dean, published in the 1990s, in which these authors presented a series of essays for a conference organized by the Latin American Program da Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (Amado, Nugent & Dean, 1990). This theme was also discussed in Oliveira (2000), in a book with a set of essays about the use of the concept of frontier and nature in a comparative form in Brazil and the United States. Similarly, the Brazilian Oeste needed to establish a new image which could deconstruct the negative image of backwardness and the sertão, creating symbols and myths in its characterization.

The frontier was thus a myth constructed on the basis of new symbols, such as the image of prosperity and the pioneering role of the frontiersmen. Cassiano Ricardo was the Brazilian intellectual who most used the language of myth in the symbolic construction of the Oeste and the historic march to the frontier.4 4 RICARDO, Cassiano. Marcha para oeste: a influência da bandeira na formação social e política do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio, 1959. The processes of the construction of this image were based on the effective occupation of the territory and the construction of institutions which materialized the dream of the frontier (Dutra e Silva; Dutra e Silva, 2019DUTRA E SILVA, Anderson; DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. "A natureza e a modernidade urbana de Goiânia nos discursos da cidade símbolo do Oeste brasileiro (1932-1942)". Historia Crítica, n. 74, p.65-93, 2019.).

This paper is part of this debate, seeking to show how natural resources were used as a symbolic element representing the economic potential of the frontier. Our focus is the role exercised by the Museu Estadual de Goiás (State Museum of Goiás - MEG) as an institution which sought to promote the natural potential of the frontier and its principal booster (Cronon, 1991CRONON, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1991.), the Goiano intellectual Zorastro Artiaga. This historical context is linked with this cultural institution, the role of its booster, and the creation of Goiânia, the new state capital of Goiás, seen at that time as the gateway to the Brazilian Oeste. Our argument is that the construction of Goiânia, which began in 1933, as well as the events related to the opening of the new capital, above all the 1942 Batismo Cultural, in which the city came to be described in many speeches as the capital of the Marcha para o Oeste reinforced these elements in the promotion of natural resources in search of property speculation, on the one hand, but above all the potential of its natural resources (Dutra e Silva; Dutra e Silva, 2019DUTRA E SILVA, Anderson; DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. "A natureza e a modernidade urbana de Goiânia nos discursos da cidade símbolo do Oeste brasileiro (1932-1942)". Historia Crítica, n. 74, p.65-93, 2019.). In this case the exhibitions held during the Batismo Cultural and their future installation in MEG, reinforced in the publicizing work carried out by its principal booster, sought to present the frontier as a place of potential.

Rather than a laboratory of history, MEG was aligned with the ideological elements which sought to highlight the region as a land rich in natural history and, at the same time, the new Eldorado of the Brazilian Oeste. Cronon’s (1991)CRONON, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1991. paper on the role of the booster in the divulgation of Chicago as the gateway to the Oeste, and its attributions in relation to the natural environment which surrounded it, are fundamental references to this analysis.

Alberti (2005)ALBERTI, Samuel J. M. M. Objects and the Museum. Isis, vol. 96, p.559-571, 2005., an exponent of studies of museological objects and collections, states that the objects exhibited in museums shows how human relations (social, cultural, economic, and political) were carried out and represented. It is thus believed that the first objects selected for exhibition in MEG were the result of interaction between donors, its curator, and the institution. As a result, drawing on Carlo Ginzburg (1989)GINZBURG, Carlo. Mitos, emblemas, sinais: morfologia e história. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989., material remnants and signs can be described which reconstruct a disappeared world, since during its trajectory objects have different uses and to reach the display cases of a museum probably pass through misuse and later a new use, but as constituents of a history.

It is important to bear in mind that the collection of fauna, above all large mammals, was part of natural history museums in the United States at a moment when the idea of the end of the frontier and the destruction of these natural resources was present (Lunde, 2016LUNDE, Darin. The Naturalist. Theodore Roosevelt, a lifetime of exploration, and the triumph of American Natural History. New York: Crown Publishers, 2016.). However, what calls our attention is how the objects and their use became part of MEG, much more concerned in exhibiting natural resources, notably mineral wealth, but also identifying exotic elements, such as objects and artifacts from the indigenous ethnicities of Central Brazil, or also bones and other artefacts from the natural history of Goiás. Thus, we consider it important not only to present the formation of the collection (objects, documents, and images) from the State Museum of Goiás, but also its relationship with the imagery of the frontier in Central Brazil. In this sense, the historical context related to the Batismo Cultural ceremony in Goiânia in 1942 gains relevance, by considering the museological exhibition in a specific political context. For this, we start from the understanding that exhibitions reveal intentions to document, collective (of a place, groups, etc.) and/or particularities. However, these are the result of choices and intentionalities, both in relation to the institutional creation projects which house collections and to what presided over their formation (Heizer, 2005HEIZER, Alda L. Observar o céu e medir a terra: instrumentos científicos e a participação do Império do Brasil na Exposição de Paris de 1889. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2005.).

Heizer (2005)HEIZER, Alda L. Observar o céu e medir a terra: instrumentos científicos e a participação do Império do Brasil na Exposição de Paris de 1889. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2005. highlights that exhibitions have to be considered as events with a regional, national and/or international nature. In nineteenth century Brazil, the National Museum organized the Industrial Exhibition with objects obtained by the Scientific Exploration Exhibition. Later, in 1862 the Brazilian Empire participated in the London World Expo, as well as those held in Paris (1867 and 1889), Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), Buenos Aires (1882) and St. Petersburg (1884) in the nineteenth century (Lopes, 1997LOPES, Maria Margaret. O Brasil descobre a pesquisa científica. Os museus e as ciências naturais no século XIX. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1997.; Heizer, 2005HEIZER, Alda L. Observar o céu e medir a terra: instrumentos científicos e a participação do Império do Brasil na Exposição de Paris de 1889. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2005.).

In the events mentioned, the Emperor was concerned with showing "products such as timber, machinery used on coffee plantations, paintings, china, ore, and Indian headdresses" (Heizer, 2005HEIZER, Alda L. Observar o céu e medir a terra: instrumentos científicos e a participação do Império do Brasil na Exposição de Paris de 1889. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2005.). In the 1889 Paris World Expo, Brazil presented, according to Heizer (2005)HEIZER, Alda L. Observar o céu e medir a terra: instrumentos científicos e a participação do Império do Brasil na Exposição de Paris de 1889. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2005., the Akt Azimuth scientific instrument, designed by Emmanuel Liais and constructed by José Hermida Passos in Rio de Janeiro. The purpose was to use the exhibition as a vehicle to spread a new image of the country in the global context, as a civilized and modern nation. However, the presence of the empire in the world exhibitions was generally seen as arrogant and precluding due to the social and racial conditions of Brazil.

According to Sanjad (2017)SANJAD, Nelson. Exposições internacionais: uma abordagem historiográfica a partir da América Latina.Históra, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 24, n. 3, p.785-826, 2017. various modalities of ‘exhibition’ emerged, from universal to thematic, associated with an area of knowledge like arts, science, medicine, public sanitation, such as economic activity (design, industry, mining, agriculture, floriculture, etc.,) and important events. He also shows that between the 1910s and 1930s the exhibitions were altered, especially in relation to their social objective. During this period they had the following foci: a) thematic or specialized; b) cultural or humanistic; c) ideological.

What is the similarity between the exhibition profile discussed by Sanjad (2017)SANJAD, Nelson. Exposições internacionais: uma abordagem historiográfica a partir da América Latina.Históra, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 24, n. 3, p.785-826, 2017. and the exhibition held in Goiás in the 1940s? In Goiás the exhibition had a national character since it involved various Brazilian states. It also had a commercial character, since samples and objects were exhibited showing the natural resources found in the Central Brazilian frontier, with the potential to add value for use in the national market. The exhibition also had an ideological profile since it was part of Vargas discourse of national integration (sertão/coast). Having said this, the exhibitions held in the Batismo Cultural Ceremony in Goiás did not differ from those held by other Brazilian states in the 1930s and 1940s.

In this sense, we start with the hypothesis that the museological collection has much to say about with which vision of the frontier and which symbolic elements this image sought to associate. This paper thus seeks to answer the following questions: which interests guided the creation of the State Museum of Goiás as an institution which divulged the natural history of Central Brazil? How did the museological exhibition, with its different objects, contribute to the establishment of the Western frontier of Brazil?

The Batismo Cultural of Goiânia and the Western Frontier Exhibition

In 1938, through Resolution no. 99, dated 19 July, the Board of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) established the festivities of the Batismo Cultural of Goiânia. However, the event was postponed to 1942, by resolution no. 169 from 15 July 1941, which stated:

The General Assembly of the National Council of Geography using its attributions and considering that, Resolution no. 99 of this Assembly assures the sponsorship and participation of the Institute in the holding of National Exhibitions of Education and Statistics, at the initiative of the Brazilian Association of Education; Whereas, in accordance with the understandings already existing between the two institutions, the Second Exhibition will be held in Goiânia, together with the 8th National Congress of Education, both of which are supported and sponsored by the state government of Goiaz, thereby constituting the batismo cultural of the new state capital.5 5 IBGE. Anais do Oitavo Congresso Brasileiro de Educação, 1942, p.04.

The IBGE resolution indicated that other cultural and academic events would be held as part of the opening of the new state capital. It highlighted that the Exhibition and the Congresses would be events ‘of the highest cultural expression,’ whose purpose was to reinforce the historical significance of the new state capital of the Central Brazilian frontier. The Batismo Cultural sought to promote the construction of Goiânia, built ‘in the heart of Brazil,’ and to "highlight the notable historical meaning of the creation of a new metropolis in the Brazilian hinterland, which, like a powerful center of culture, constituted as an admirable landmark in an effort to ‘internalize’ Brazilian civilizing forces in the continuity of its Marcha para o Oeste."6 6 IBGE. Anais do Oitavo Congresso Brasileiro de Educação, 1942, p.04. The use of the term metropolis is an overstatement at this moment, but is evident of the propagandistic language of the regime. At the same time, it sought to reinforce the insertion of the state’s territory in the political and economic integration policies of the Estado Novo (1937-1945)

IBGE’s Board, passed the above mentioned resolution, seeking to including in the Batismo Cultural a set of the Institute’s activities, such as an ordinary session of the National Council of Geography (Art. 1) and the Second National Exhibition of Education and Statistics, also under the coordination of the National Council of Geography (Art. 2), which had as a theme Education, Statistics, and Cartography (Paragraph 1). Article 3 contained the suggestion that the presidency of the Institute should encourage together with the state and federal governments the establishment of national legislation which could definitively establish the interstate boundaries, a target of IBGE in terms of finally resolving the boundaries of the states of the federation.7 7 IBGE. Anais do Oitavo Congresso Brasileiro de Educação, 1942.

Highlighted in these articles was the leading rule of geographic institutions in the administration of the Batismo Cultural as well as showing the relevance of this event considering the federal government’s proposal to incorporate the hinterland in the nation. The prospect of the existence of a new state capital in Goiás strengthened the policies implemented by the federal government. The new city could play also an important role as motivation for migration to the interior of the country, to assure regional (and obviously national) power, and also to strengthen the discourse of progress and modernity with the Estado Novo.8 8 According to Lenharo (1986), one of aspects least analyzed in Brazilian historiography about the Estado Novo was how it dealt with rural questions. He argues that the historiographic emphasis privileges political character, urban processes linked to industrialization, and labor questions in the Estado Nacional. However, he shows that agricultural development and land occupation policies received a lot of investment from the regime, above all in colonization processes for the West. In this sense, it is important to identify the role in which the Oeste (West) appeared in Vargas’s programs. With Ricardo Cassiano being one of the central articulators of this, the expression Oeste could signify not only Central Brazil, but also Amazônia, Acre, and Rondônia, amongst others. According to Dutra e Silva (2017), Oeste came to be a more symbolic category than geographic, in which sense he defends that studies of the expansion of the frontier between the 1930s and 1950s cannot ignore the uses of this representation (RICARDO, Cassiano. Marcha para oeste: a influência da bandeira na formação social e política do Brasil). The 1942 event in Goiânia sought to align the federal with the regional sphere, confirming what President Getúlio Vargas (1882-1954) stated on 31 December 1937, when he established the origins of the Marcha and the occupation of the Brazilian hinterland: "In the eighteenth century, from there came the flow of gold that poured into Europe and made America the continent of greed and adventurous attempts. There we shall to go to search for the vast and fertile valleys, the product of various abundant crops; and from the bowels of the earth, the metal with which to forge the instruments of our defense and our industrial progress."9 9 Getulio Vargas. No limiar do ano de 1938. Saudação aos brasileiros, pronunciada no Palácio Guanabara e irradiada para todo o país, à meia noite de 31 de dez. 1937. Presidência da República Casa Civil, Secretaria de Administração, Diretoria de Gestão de Pessoas, Coordenação - Geral de Documentação e Informação, Coordenação de Biblioteca.

For the events proposed in the above mentioned documents, activities were held from 20th to 28th June and 1st to 11th July 1942, with a total of 20 days of events involving local and national society to make it significant and call the attention of the country to the youngest daughter10 10 An expression used by Paulo Figueiredo, published in the first issue of the periodical Oeste (1942) to designate Goiânia. of Brazil. Among institutions involved were the Brazilian Association of Education; the National Council of Statistics; the National Council of Geography; the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics11 11 IBGE was created by decree-law no. 218 from 26 January 1938, in reality just a change of names of two federal agencies (the National Institute of Statistics and the Brazilian Geographic Council) which already existed. Art. 10 of this decree stated: "The National Institute of Statistics shall henceforth be called the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, with the collegiate bodies controlling both — Geography and Statistics — being called the National Council." (and their respective regional councils); and the Ministry of Agriculture. IBGE, through its the National Council of Geography, took as mentioned above, the leading role. For example, in Figure 1 the Interventor in Goiás, Pedro Ludovico Teixeira (1891-1979), can be seen greeting the geographer Fábio de Macedo Soares Guimarães (1906-1979), principal IBGE representative in Goiás (Tavares, 2010TAVARES, Giovana Galvão. Zoroastro Artiaga - o divulgador do sertão goiano (1930 - 1970). Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2010.).

Batismo Cultural ceremony, introduction of Fábio de Macedo Soares Guimarães to Pedro Ludovico Teixeira, Interventor of Goiás (with Mário Augusto Teixeira de Freitas beside him)

Central to the Batismo Cultural were the exhibitions held in the Technical School of Goiás. Inside the Technical School were municipal maps (the result of the Lei Geográfica); mineral resources and timber, amongst other information from Brazilian regions, as well as various other products which defined and characterize the economic potential of Brazilian regions.

Items exhibited included: graphics, maps, schoolwork, artistic pictures, rocks, ores, photographic albums, and other publications. Present were stands from federal agencies, such as IBGE, CNG, CNE, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Labor, Industry, and Commerce, the Ministry of the Marine, the Economic and Financial Statistical Service of the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Statistical Service of Education and Health, the Ministry of Aviation, the Department of Press and Propaganda, and the National Department of Coffee, as well as regional products presented at the stands of the states of Bahia, Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, Paraíba, Paraná, Pará, Santa Catarina, Mato Grosso, Ceará, Amazonas, Alagoas, Sergipe, Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, Maranhão, Rio Grande do Norte, and of course Goiás.

The objects that formed the collection of the Goiás Exhibition were donated to the state government, which displayed them in the Permanent Exhibition in Goiânia (EPG). Later they were sent to the State Department of Culture (DEC). Included among these were clothes, ornaments, maps, rocks, and ores - the last two with a potential for industrial commercialization. DEC’s visitor books contained in the 1940s the signatures of businessmen or representatives of other state governments who came to the Department to see the natural resources exhibited, especially rocks and ores (Tavares, 2010TAVARES, Giovana Galvão. Zoroastro Artiaga - o divulgador do sertão goiano (1930 - 1970). Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2010.).

DEC sought to culturally and politically promote the state of Goiás, above all within Brazil, indeed one of its functions was to send articles and texts to newspapers, magazines and radios (local and national) in order to publicize the natural riches and the economic progress of Goiânia. In addition, there were other themes which could attract capital, investors, and immigrants to the state.

It was through his role as the administrator of DEC that Zoroastro Artiaga received funding to publish books and articles about Goiás, notably works about geology, the history of Goiás, the indigenous population, and radium mining, amongst others (Artiaga, 1947; 1947a; 1943; 1943a; s/d).12 12 ARTIAGA, Zoroastro. Geologia Econômica de Goiaz. Uberaba, 1947; Dos Índios do Brasil Central. Uberaba, 1947a; Contribuição para a História de Goiaz: Goiânia: mimeo, undated; Monografia Corográfica do Estado de Goiaz. Goiânia: mimeo undated; Minérios de Radium em Goiaz (ao Instituto de Pesquisas Tecnológicas de S. Paulo). Revista Oeste, ano II, n. 11, p.452-435, 1943; Minas e Goiaz. Revista Oeste, ano II, n.13, p.520-521, 1943a. After 1946, the items became part of the collection of the State Museum of Goiás and Zoroastro Artiaga was appointed the first director of the State Museum of Goiás.

MEG: Zoroastro Artiaga and cultural promotion

The project to create the State Museum of Goiás (MEG), currently the Zoroastro Artiaga Goiano Museum (MUZA), was a peculiar initiative, whose purpose went beyond the scientific dissemination of the natural history of Goiás. In addition to the prerogatives to create an institution to promote science, it needs to be understood that it was part of the national project for the expansion of the frontier. It also must be seen in the regional context of the opening of the new state capital and political changes in Goiás. The idea to change the capital, conceived by the interventor Pedro Ludovico at the beginning of the 1930s, sought not only to break with the oligarchies of the old capital, but also to establish a new aesthetic sense for the urban traits and public buildings of Goiânia. It is thus important to consider the architectural component of the art déco style of architecture, which reinforced the cultural, political, and symbolic objectives of MEG and its exhibitions.

Art déco was the aesthetic model chosen for the architecture intended for the urban landscape of Goiânia. It sought to imprint on the landscape of the new capital the expression of modern (and not modernist) traits through aesthetic elements which adorned buildings in public spaces. Art déco was not only an architectural style concerned with guiding the aesthetic of the modernization of Goiás, but also a distinct and significant cultural expression, since in addition to the artistic components on the urban landscape. This architecture was a clear expression of the breaking away from the archaic roots of and the vernacular construction in the former state capital. In this way, the art déco architectural composition of Goiânia can be understood as a political project for a new frontier aesthetic, as it sought to integrate the distant and isolated territory of the state to the national project (Lenharo, 1986LENHARO, Alcir. Sacralização da política. Campinas: Papirus, 1986.; Reis, 2014REIS, Marcio Vinícius. O art déco na Obra Getuliana. Moderno antes do modernismo. 2014. Tese (Doutorado). Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2014.; Paiva, 2004PAIVA, Salma Saddi Waress de. Prefácio. In: MANSO, Celina Fernandes Almeida. Goiânia art déco: acervo arquitetônico e urbanístico - dossiê de tombamento. Volume I, Identificação. Goiânia: Seplan, 2004.; Unes, 2001UNES, Wolney.Identidade Art Déco de Goiânia. São Paulo: Ateliê Editorial; Goiânia: UFG, 2001.).

According to Daher (2003)DAHER, Tânia. Goiânia: uma utopia europeia no Brasil. Goiânia: Instituto Centro Brasileiro de Cultura, 2003. to a certain extent art déco emerged as an experimental choice, whose aim was to implement modernity on the frontier. However, the work of Lacerda (1994)LACERDA, Aline Lopes de. A "Obra Getuliana" ou como as imagens comemoram o regime. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 7, n. 14, 1994, p.241-263. and Reis (2014)REIS, Marcio Vinícius. O art déco na Obra Getuliana. Moderno antes do modernismo. 2014. Tese (Doutorado). Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2014. show that the style was part of a broader propaganda project by the Vargas regime. Their work was based on archival sources, collected by Gustavo Capanema (1900-1995) - a collector of photographs which portrayed the Vargas period -, in which art déco architecture highlighted the role of the ideological elements of the regime. The architectural ensemble demonstrated the art déco style came to be one of the principal representations of Estado Novo propaganda. Capanema’s project was named by him as Obra Getuliana, the archival sources of which became, in 1978, part of the special collection of the Center for Research and Documentation of the Contemporary History of Brazil in the Getúlio Vargas Foundation. This archive has more than 600 photographs which show the role of this architectural style in aesthetically characterizing the regime between the 1930s and 1940s.

Lacerda’s work (1994) had the aim of noting the particularity of the use of the photography in the Obra Getuliana for the ideological construction of the nation and the regime. The work of Reis (2014)REIS, Marcio Vinícius. O art déco na Obra Getuliana. Moderno antes do modernismo. 2014. Tese (Doutorado). Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2014. sought to investigate the role of the art déco style as a modern aesthetic expression present in the Obra Getuliana based on the analysis of numerous public buildings constructed between 1930 and 1945. At the same time, it sought to identify how the regime disseminated this style as a form of propaganda. Reis argues that an analysis of the architectural role during the Vargas Era (1930-1945) supplants merely stylistic questions, and it is also necessary to consider "constructive nationality and spatial functionality, the return and the economy of means, the standardization of typologies and finishing elements and materials, and a modern language which can make political ideology intelligible" (Reis, 2014REIS, Marcio Vinícius. O art déco na Obra Getuliana. Moderno antes do modernismo. 2014. Tese (Doutorado). Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2014., p.16).

It is in this sense that we consider it important to highlight that the architectural choice of art déco was not simply experimental, as stated by Daher (2003)DAHER, Tânia. Goiânia: uma utopia europeia no Brasil. Goiânia: Instituto Centro Brasileiro de Cultura, 2003., as this did not represent only the project for the urban development and modernization project for the Central Brazilian frontier. It is also evidence of a propagandistic project expressed through buildings and development which symbolize the presence of the nation in march and the nationalistic regime in force at that moment. For these reasons we identify the ensemble of these representations in the construction which came to house the State Museum of Goiás.

The building which houses the State Museum of Goiás was designed by the Polish architect Kazimierz Batoszewski (1914-1990) and was one of the buildings which composed the architectural ensemble of the Praça Cívica (Civic Square), the place chosen to house the public buildings of the new state capital.13 13 In 2002, the buildings constructed in the city of Goiânia in the 1930s and 1940s in an Art Déco style were considered by IPHAN as national architectural heritage, namely: 1) those in the praça cívica — the gazebo in the praça cívica, lights, the forum and courthouse, the residence of Pedro Ludovico Teixeira, the Goiano Zoroastro Artiaga Musuem, Obelisks with lights, Esmeraldas Palace, the Tax Office, Police Headquarters, the General Secretariat, the Clock Tower, and the Federal Regional Court; 2) isolated buildings: Goiânia Lyceum, the Grande Hotel, the Goiânia Theater, the Technical School, the Railway Station, the Trampoline and Wall of the Lago das Rosas; 3) the settlement of Campinas: Palace Hotel and Sub-Mayoral Office, and the Forum of Campinas, MANSO, 2004; DAHER, 2003. Originally the building had been used by the State Department of Information and later housed museological activities. The space had a floor plan with staggered volumes and the principal access in the form of an advance (Figure 2). The architectural details mixed the economy of adornments and traces geometrically marked by the sobriety of the grey, the sumptuousness of the concrete columns, and the details of the gate with railings and a metallic mesh, produced without the use of welding, but with rivets.

In 1946 this building came to house MEG and Zoroastro Artiaga was appointed as its first director. Following Law no. 5,770, from 16 June 1965, the museum came to be called Zoroastro Artiaga Goiano Museum, in honor of its first director. Initially, MEG became a repository of the historic documentation of Goiás and gained for itself unlimited activities involving education, fieldwork and natural sciences, the holding of events and tourism, and the rendering of services to companies. All these activities were coordinated by Zoroastro Artiaga, in accordance with the information found in the institution’s minute books. Between 1947 and 1957, MEG was transformed into an institution for the dissemination of earth sciences. Zoroastro remained director of the State Museum until 1959 and sought to expand its objectives in order to better publicize natural resources and the economic possibilities of the state. For this reason, it is considered the principal booster of the potentialities of the Central Brazilian frontier.

Zoroastro Artiaga was born in 1891 in the city of Curralinho, in the interior of Goiás, and spent his childhood and teenage years there. In his youth he assumed the position of clerk in the Repartição Geral dos Telégrafos. In the 1920s he started to publish in Goiano and Mineiro newspapers. During this decade he held the position of clerk in the Delegacia Regional do Estado in the city of Catalão (1924-1929). His first published articles were about the railway network and the economic development of the state, espousing the feeling of belonging to the region. In 1929, he began a Law Degree at the Goiás School of Law, from where he graduated in 1933, and entered the Order of Lawyers in 1935 (Tavares, 2010TAVARES, Giovana Galvão. Zoroastro Artiaga - o divulgador do sertão goiano (1930 - 1970). Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2010.).

In the 1930s, Artiaga became ideologically close to the group which assumed political power in Goiás during the Vargas period (1930-1945).14 14 The group consisted of regional politicians who were responsible for creating a number of institutions in Goiás, including the Historical and Geographic Institute of Goiás, the Institute of Lawyers of Goiás, and the Goiana Academy of Letters. They were part of the political group of the Interventor Pedro Ludovico Teixeira, especially the following: Colemar Natal e Silva, Dario Delio Cardoso, Agnelo Arlington Fleury Curado, Alcides Celso Ramos Jubé, Francisco Ferreira de Santos Azevedo, and Joaquim Carvalho Ferreira, amongst others. This group wanted to give a new historic meaning to the Brazilian Oeste, seeking to separate it from the idea of sertão. Sertão symbolized isolated and backwardness, as well as the predominance of archaic institutions. The rupture with this model involved institutional modernization and the construction of symbolic elements to highlight the new region. Oeste is the concept that best represent this epoch. The use of this symbolic resource drew on the rhetoric of national integration, especially the national project of territorial formation in which the occupation of empty spaces was a crucial element for the unity of the country. It is also important to take into account the role exercised by the Departamento Oficial de Propaganda (DOP - Official Propaganda Department), created in 1931 and replaced in 1934 by Departamento de Propaganda e Difusão Cultural (DPDC - Department of Propaganda and Cultural Diffusion), whose purpose was to analyze the use of images and other forms of cultural expression which could serve as instruments of aesthetic and ideological diffusion of the regime. In this sense, the use of expressions such as Oeste and hinterland, very present in the discourse and archival sources of the epoch approximated all the mechanisms of aesthetics and the rhetoric of the Estado Novo (Lenharo, 1986LENHARO, Alcir. Sacralização da política. Campinas: Papirus, 1986.; Lacerda, 1994LACERDA, Aline Lopes de. A "Obra Getuliana" ou como as imagens comemoram o regime. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 7, n. 14, 1994, p.241-263.; Reis, 2014REIS, Marcio Vinícius. O art déco na Obra Getuliana. Moderno antes do modernismo. 2014. Tese (Doutorado). Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2014.; Dutra e Silva et. al., 2014DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro; TAVARES, Giovana Galvão; SÁ, Dominichi Miranda de, FRANCO, José Luiz de Andrade. Fronteira, História e Natureza: a construção simbólica do Oeste Brasileiro (1930-1940). HIb. Revista de Historia Iberoamericana, vol. 7, n. 2, p.1-23, 2014.; Dutra e Silva, 2017DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017.).

According to Tavares (2010)TAVARES, Giovana Galvão. Zoroastro Artiaga - o divulgador do sertão goiano (1930 - 1970). Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, 2010., Artiaga was considered a polymath, since he proposed to write about and discuss a wide range of areas of knowledge (Geology, Economics, Statistics, History, Anthropology, Geography, etc.) He exercised a multiplicity of roles (administrator, radio presenter, journalist, teacher, lawyer) and at the same time maintained the identity of his practices associated with the defense of national integration as a path for the progress of Goiás. Often aiming his actions at the publicizing of the state’s natural wealth (ores, rocks, plants, etc.), with the purpose of favoring economic relations between Goiás and other states of the Brazilian federation or other countries.15 15 In a talk given in the Federal University of Minas Gerais the historian Peter Burke stated that polymaths observed unexpected connections between different fields of knowledge, with evaluations coming from a trained eye in another discipline or field of knowledge. To the contrary of the specialized visions, polymaths had an aggregated manner of thinking which sought to unify knowledge. For him, specialized knowledge can be summarized in the following statement: knowing more about increasingly less subjects (BRAGA, 2017).

It should be noted that the specialization of knowledge in Brazil advanced with the growth of universities in the country, especially following the creation in the 1930s of the University of São Paulo and the University of the Federal District (Fávero, 2006FÁVERO, Maria de Lourdes de Albuquerque. A Universidade no Brasil: das origens à Reforma Universitária de 1968. Educar, n. 28, p.17-36, 2006.). However, it is important to mention that before these universities were created other institutions in the country preserved the specialization of knowledge and carried out research in the field of Geosciences, such as the Mining School of Ouro Preto, the Institute of Technological Research, and the Geological and Mining Service of Brazil, expanded in 1933 to the National Department of Mineral Research. These institutions were often created in association with foreign specialists who were invited to train professionals in Brazil.

Artiaga graduated in Law, but also did short courses in Geology, Botany, and Statistics in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In 1936 he was in charge of the official press and in 1937 began his public activities in the field of geosciences, holding the position of Secretary of the Regional Directorate of Geography of IBGE, and becoming a member of the State Border Commission (Geographic Law of the Estado Novo - Decree-Law 311 dated 02 March 1938). He also participated in the Propaganda Commission that aimed to move the federal capital to the interior of Brazil and which consisted of Goianos who wanted in one form or another to call national attention to Goiás.

Artiaga participated in the birth of the ideas of the Estado Novo (1937-1945), as well of cultural institutions in Goiás, joining a group of regional intellectuals and creating the Lawyers Institute of Goiás (IAG), the Academy of Letters of Goiás (AGL), the Historical and Geographic Institute of Goiás (IHGG), the State Museum of Goiás (MEG), and Lyceum of Goiânia. In addition to these institutions, he also helped publish articles in important Brazilian and regional periodicals, especially Informação Goyana (1917-1935) and Oeste (1942-1945), publications that promoted ideas and scientific and/or cultural knowledge of that time. He wrote about various topics, notably the mineral resources of Goiás.16 16 The generation which wrote in Revista Informação Goyana was composed of a group of young Goianos living in Rio de Janeiro including professionals from various areas: engineers, doctors, teachers, pharmacists, clergy, politicians, historians, and soldiers, amongst others, who published 230 issues without interruption. It was published in Rio de Janeiro and circulated in other Brazilian states (Tavares, 2010; Dutra e Silva et. al, 2014). To the contrary of Revista Informação Goyana, Revista Oeste circulated from inside to outside, in other words, from the state of Goiás to the other Brazilian states, with the purpose of presenting a modern place, which had as an icon the new state capital — Goiânia. It was launched on 5 March 1942, during the Batismo Cultural of Goiânia, with funding and the direct influence of Getúlio Vargas and his developmentalist and populist ideas. For this reason, it became an official government publication, which used it to divulge issues of political, administrative, and ideological interest. Revista Oeste operated the ideological service of the Estado Novo, working with Vargas’ ‘interiorization’ policy, both in the change of the capital to Goiânia and the Marcha para Oeste, praising the figures of Getúlio Vargas and Pedro Ludovico Teixeira (Dutra e Silva et. al, 2014).

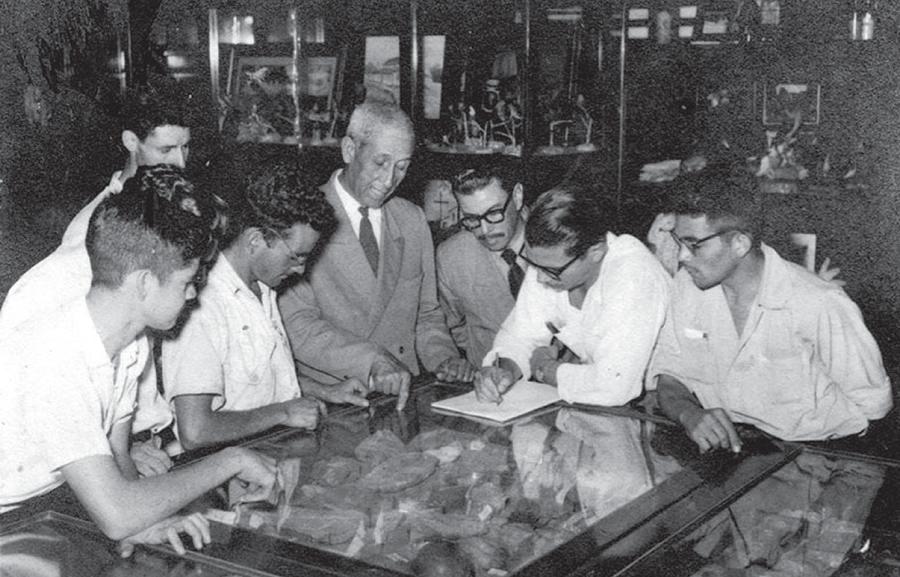

Also, in the 1940s, Artiaga took charge of the State Department of Culture (DEC). Among his duties was helping to organize the Permanent Exhibition of Goiânia, which was used to publicize regional culture, ongoing economic activities, and the future potential of Goiás due to its natural resources (Figure 3). As he stated, the "Permanent Exhibition will present samples from the industries of our state, our latent wealth, our labor and production capacity, whether in the rural sector or in urban activities."17 17 Arquivos do Museu Zoroastro Artiaga. Cf. correspondência de Zoroastro Artiaga, diretor geral da DEC, ao governador do Estado de Goiás Jerônimo Coimbra Bueno. Ofício n. 83 de 27 de mar. 1947. However, the collection of this exhibition sought to collect objects (rocks and ores, indigenous artifacts, and bones) which highlighted the cultural and natural history of Goiás.

Zoroastro Artiaga showing ore samples from Goiás to a group of visitors to the State Museum of Goiás

Exhibition items and the creation of the State Museum of Goiás

In addition to the objects which came from the Batismo Cultural, Zoroastro Artiaga asked politicians, members of traditional families in Goiás, and national institutions, amongst others, to donate pieces with the purpose of obtaining artifacts to expand MEG’s collection. On 17 April 1947, the booster wrote to the mayor of Cavalcante asking for samples of mineral resources to exhibit:

This Department has been subjected to continuous questions about the existence of citrine crystal [quartz with a yellow color] in the state’s territory, widely used in the manufacture of optical instruments. Repeatedly numerous visitors to the Permanent Exhibition have shown the desire to see samples of this type of crystal, which, according to what I have been informed, exists copiously in your prosperous commune. Therefore, wishing to satisfy the curiosity of these illustrious visitors and with the intention of publicizing widely known products from our inexhaustible mineral beds in the exhibition, immersed in the still spacious sea of ignorance related to national economic progress, I hereby appeal to your great spirit of cooperation and love for the progress of Cavalcante, to supply any amount (a minimum of 500 grams) of the kind of crystal in question to this Department with the aim of enriching the already existing collection. (...) If the mayor’s office cannot afford the cost of obtaining this sample, this Department is happy to do so, once an invoice is sent for all expenditure incurred."18 18 Arquivos do Museu Zoroastro Artiaga, Ofício n. 34 de 17 abr. 1947.

This quotation shows that Zoroastro did not only fulfill the function of booster of the mineral potential of Goiás, but also proposed that collections be created, taking as orientation for this the questions of possible interest in the natural resources of the region. He also worked on the creation of a geological map of Goiás, in which he presented the distribution of ores whose purpose was museological exhibition but also the attraction of external investment to Goiás. As the documentation presented in the above letter showed, the items meant for the museum are evidence of both interest in the presentation of registers of natural history (Figure 4) and satisfying those interested in the exploitation of mineral resources (Figures 5 and 6).

According to Official Letter no. 53 dated 27 February 1947, the Museum had no funding for its maintenance or the acquisition of exhibition materials. In Official Letter no. 220, dated 24 June 1947, DEC sought to expand the functions of MEG, "in relation to the exhibition of art and historic documents. To take into account this program it is necessary to broaden the period in question, otherwise it will be impractical due to the lack of funds reserved for the maintenance of the Museum."20 20 Arquivos do Museu Zoroastro Artiaga, Ofício nº 220 de 24 de jun. 1947.

During 1947 Zoroastro Artiaga contacted various families from the towns of Goiás whose principal economic activity during the nineteenth century had been mining or livestock. The reason for this was to obtain the donation of items and other private goods to be exhibited in the Museum, as shown in the letter sent to Luiz de Pina, who was asked to intervene with his mother-in-law, asking her for a skull with the horns of a cow: "that she might give or lend to us for some time a cow skull existing on the Babylonia Fazenda to appear in this museum, where the ranch appears in an amplified picture as a historical document of life in Goiaz."21 21 Arquivos do Museu Zoroastro Artiaga, Ofício 49, 1947 (documento encaminhado ao Sr. Luiz de Pina). Fazenda Babilônia was a house in the Bandeirante style in which a sugar mill had operated at the end of the eighteenth century and was cited in different reports of travelers who passed through the Province of Goiás at the beginning of the nineteenth century.22 22 POHL, Johann Emanuel. Viagem ao interior do Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Ed. Itatiaia; São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1976; SAINT-HILAIRE, Auguste de. Viagem à Província de Goiás. Belo Horizonte: Ed. Itatiaia; São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1975. On this fazenda, in addition to sugarcane, manioc and cotton were planted on an industrial scale for the production of flour and fabrics which were exported to Britain (McCreery, 2006McCREERY, David. Frontier Goiás, 1822-1889. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.).

Various other official letters were sent to mayors and traditional families in the state. In 1948 MEG expanded its collection of items which narrated the history of Goiás and presented the mineral resources and rocks with commercial potential. Here it is worth noting Lopes’ observation (2001) that collections do not originate in museums. For her, the museum should be seen as an end, in which pieces are chosen because they are considered to be collectable, and through this selection these "pieces of the most different types start a long and complex voyage through the field until their exhibition in the museum" (Lopes, 2001LOPES, Maria Margaret. Viajando pelo campo e pelas coleções: aspectos de uma controvérsia paleontológica. Históra, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, vol. 8, p.881-897, 2001., p.884).

It is also interesting to perceive not only the pieces in themselves, but the exercise of identifying, requesting, collecting, cataloging, and exhibiting certain materials. It is worth noting the perception of the museologist Darin Lunde (2016)LUNDE, Darin. The Naturalist. Theodore Roosevelt, a lifetime of exploration, and the triumph of American Natural History. New York: Crown Publishers, 2016. who worked, amongst other subjects, with the biography of Theodor Roosevelt and his role as a naturalist hunter, and who contributed to the constitution of important collections of natural history for the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. According to Lunde, museums should also be considered through the experience and determination of various collectors’ items: "This is the story of one man’s determination to experience nature without sentiment or judgment" (Lunde, 2016LUNDE, Darin. The Naturalist. Theodore Roosevelt, a lifetime of exploration, and the triumph of American Natural History. New York: Crown Publishers, 2016., p.6). Moreover, museums are also research institutions, with their spaces and rooms which are often strange to the visitor and reflect the obstinate work of collectors and curators. Also, of importance is the dedicated work of scientists, taxidermists, explorers, cartographers, geologists, and a large support team which scientific expeditions bring together and which collections of museums around the world preserve (Elias; Martins; Moreira, 2018ELIAS, Simone Santana Rodrigues; MARTINS, Décio Ruivo; MOREIRA, Ildeu de Castro. As Expedições Naturalistas e Cartográficas e as Práticas Científicas no Brasil do Século XVIII. Fronteiras: Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science, vol. 7, n. 1, p.15-36, 2018.).

In this research, we have questioned the motivations and abilities which accredited Zoroastro Artiaga to direct an institution with a profile of a natural history museum, but whose exhibition of such disparate and distinct pieces gave the perception of the absence of the necessary knowledge and expertise for this project. Our argument is that this activity cannot be disconnected from Artiaga’s other actions in the context of the promotion of the frontier as a potential zone of economic and demographic expansion. We did not find any dialogues with other museological institutions or in the development of fauna collection projects for the zoological composition of the biodiversity of the Cerrado. His interests characterized him much more as a booster for the opportunities of Central Brazil, while the museum with its collection and exhibition was much more a vehicle for publicizing the civilizing projects of the frontier.

Artiaga dedicated a large part of his life to promoting the frontier of Goiás and his action as a booster for Central Brazil was also associated with providing information about the natural wealth of the state through knowledge of the geosciences. He saw a context in which divulging the geological potentials of the frontier was a crucial point for regional development, taking advantage of federal projects for industrial development and the lack of raw material in the geo-economic rearrangement of Brazil.

In a report sent to the state governor on 19 July 1947, Artiaga highlighted the importance of publicizing the state of Goiás and the need for funds for this task. The report defended massive investment in propaganda about the natural resources of Central Brazil, stating that the pieces and historic documents exhibited in the State Museum of Goiás - described as a "practical means of archival propaganda" - could help in the promotion of regional potentials.23 23 Arquivos do Museu Zoroastro Artiaga, relatório encaminhado ao governador do Estado em 19 de jul. 1947.

Final considerations

Currently the Zoroastro Artiaga Goiano Museum is part of the historic heritage of the architectural ensemble of the Praça Cívica and carries out museological activities with permanent and temporary exhibitions. Entering the ground floor of the building in the entrance hall there is a kiosk selling books and other objects and souvenirs dealing with history, geography, and indigenous literature from Goiás. After the visitor reception space are two interlinked exhibition rooms. From the thematic involved and the form of pieces are displayed, we can perceive that it has a more educational function, arranged around a varied theme, ranging from the geological scale of the formation of Earth and the evolution of mankind to the exhibition of items and information about Brazilian indigenous tribes, giving greater space to those who lived in Goiás. In this area we also found items from the natural history of the Cerrado, with the exhibition of stuffed animals that represented the biodiversity of this ecosystem. Other pieces showed evidence of occupational processes, presenting equipment used for mining the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In the second exhibition room the items from the natural history of the Cerrado prioritize the collection of rocks and ores found in the state, equipment used by the local press to publish newspapers, and pieces of Barroque sacred art from eighteenth and nineteenth century Goiás. On the upper floor are permanent exhibitions about the rural culture and details of rural life in Central Brazil. Thematic diversity can be seen and even with a reduced archive, the museum fulfills the attributions of its institutional mission and its museological role as the guardian of memory.

However, when we seek to historically understand the cultural context of the 1942 Exhibition and the facts that involved the creation of the State Museum of Goiás, as well as the actions of its first director, we can perceive that much more than a concern with founding an institution to promote the natural history of Central Brazil, the interests involved went beyond the museological goal. Evident was the need to manufacture a positive image of the Central Brazilian frontier. In this case, we can perceive a set of intentions, ranging from the need for the demographic occupation of the state to the divulgation of natural resources among national and foreign investors. In this sense the role of Zoroastro Artiaga was fundamental, since he not only used the Museum as a means of promotion, but widely advertised the natural resources, above all the mineral potential of the state.

The mineralogical collection dominated the permanent exhibitions and the archives demonstrate that new ores and exhibition artifacts were searched for in various parts of the state. However, it is interesting to think about the reasons for the privileging of these pieces to the detriment of ethnographic and archeological exhibitions. Also visible is the contempt for the fauna and flora of the Cerrado in this collection. Indeed, also very evident is that the use of indigenous artifacts in the museum, much more than reinforcing the cultural inheritance, seems to present to visitors that the extermination of these populations was an imminent fact and that they now were only museological items. A concern which meant that ethnologists in the first half of the twentieth century would come in search of this material to form collections in European natural history museums. Of importance here is the work of the German ethnologists Paul Max, Alexander Ehrenreich, Karl von den Steinen, and Fritz Krause, who collected specimens of clothing, artifacts, weapons, and ceremonial objects, amongst others, considering the possibility of the inevitable disappearance of these records of frontier expansion (Stauffer, 1960STAUFFER, David Hall. Origem e fundação do Serviço de Proteção aos índios. A reação contra o extermínio dos índios. Publicidade danosa no estrangeiro. Revista de História, vol. 21, n. 43, p.165-183, 1960.).

What we must consider is that much more than a formal collection about the natural history of the Cerrado, the Museum was rather an institution which sought to promote the conquest and expansion of the frontier. Indeed, the museological exhibition with its different items on show, and in a certain form so distinct, sought to promote the Brazilian Western frontier as a place of modernization and prosperity for those who adventured to explore its natural resources.

-

1

In relation to the expansion process of the agricultural frontier in Goiás, other forms of frontier can be considered, following Hennessy’s model (1978) of the occupation process of these spaces in Latin America. In Goiás, the agricultural expansion process followed a distinct path due to a number of variables. As shown by Teresa Cribelli (2016)CRIBELLI, Teresa. Industrial Forests and Mechanical Marvels Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016., the agricultural modernization process in Brazil originated in the nineteenth century, considered by her as a ‘conservative modernization’ process, based on the technological advance and the maintenance of the social order. In the case of Goiás, the expansion of the agricultural frontier occurred even later, as a distinct form of adaptation to the conservative modernization model, CAMPOS (2012)CAMPOS, Francisco Itami. Questões agrárias: bases sociais da política goiana. Goiânia: Kelps, 2012.. Agriculture was dependent on logistical integration with the rest of the country, which commenced in Goiás in the first half of the twentieth century, BORGES, (1980)BORGES, Barsanufo G. O despertar dos dormentes. Goiânia: Ed. UFG, 1980.. McCreery (2006)McCREERY, David. Frontier Goiás, 1822-1889. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006. reinforces this model with research on the role of livestock in the Goiás economy in the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. For him, cattle were the principal form of integration between Goiás and the rest of the country, since cattle were a type of good that transported itself. He also states that until the arrival of the railway, Goiás was the ‘frontier of the frontier,’ due to its geographic position in the central chapadões of Brazil — as it was difficult to access and its isolation was more than geographic, being also political, territorial, and economic. At the same time the classic work of Warren Dean (1996)DEAN, Warren. A ferro e fogo: a história da devastação da Mata Atlântica brasileira. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996. shows that the expansion practices of the agricultural frontier in Brazil were associated with the availability of tropical forests, in adherence to the archaic model of slash and burn agriculture. In the case of Goiás, the process of the expansion of the agricultural frontier (which as previously stated only occurred in the first half of the twentieth century) was strongly associated with the dynamic of railway expansion, which connected the region with the productive centers. In this sense, the work of Dutra e Silva (2017)DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017. adds to Dean’s work (1995), by considering the forested region of Mato Grosso de Goiás as the privileged locus of agricultural expansion policies in the 1930s and 1940s which preceded the agricultural occupation of the Cerrado. In relation to this, see also: WAIBEL (1947WAIBEL, Leo. Uma viagem de reconhecimento ao sul de Goiás. Revista Brasileira de Geografia, ano IX (3), p.313-342, 1947.; 1948)WAIBEL, Leo. Vegetation and Land Use in the Planalto Central of Brazil. Geographical Review, v. XXXVIII, p.529-554, Oct. 1948.; JAMES (1953)JAMES, Preston E. Trends in Brazilian Agricultural Development. Geographical Review, 43 (3), p.301-328, 1953.; GIUSTINA; DUTRA E SILVA; MARTINS (2018)GIUSTINA, Carlos Christian Della; DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro; MARTINS, Eder. Geographic Reconstruction of a Central-West Brazilian Landscape Devastated During the First Half of the 20th Century: Mato Grosso de Goiás. Sustentabilidade em Debate, vol. 9, n. 3, p.44 - 63, 28 dez. 2018..

-

2

Dutra e Silva (2017)DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017. shows how the documentation used in the 1930s, above all during the Estado Novo (1937-1945), came to use expressions such as frontier, hinterland and above all Oeste (West). The category Oeste was much more than a symbolic element demarcating a geographic region. It came to represent a symbolic category which presented the agrarian as a social space of prosperity, the land of promise. He bases his work on different documentary sources, such as reports, essays, and political speeches, amongst others, which use this rhetoric. At the same time there exists a weakening of the category sertão, practically abandoned and replaced during the Estado Novo by new symbolic elements of the territory, which divulged a colonization and migration project not for the sertão, but in a march towards the West, that was both geographic and symbolic.

-

3

There exists a set of published works which use a comparative model in a conceptual manner and historical processes in themselves, related to the frontier in Brazil and the United States. I highlight here the works of Viana Moog (1964)MOOG, Viana. Bandeirantes and Pioneers. New York: George Braziller, 1964., Pierre Monbeig (1998)MONBEIG, Pierre. Pioneiros e fazendeiros de São Paulo. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1998., and Sergio Buarque de Holanda (1995)HOLANDA, Sérgio Buarque de. Caminhos e fronteiras. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1995. as representative works in the use of the category of frontier and wilderness in studies about the relationship between society and nature in Brazil. More recently, I would like to highlight the work of Janaina Amado, Walter Nugent, and Warren Dean, published in the 1990s, in which these authors presented a series of essays for a conference organized by the Latin American Program da Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (Amado, Nugent & Dean, 1990AMADO, Janaina; NUGENT, Walter; DEAN, Warren. Frontier in Comparative Perspectives: the United States and Brazil. Working Papers of the Latin American Program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Washington, D.C, 1990.). This theme was also discussed in Oliveira (2000)OLIVEIRA, Lucia Lippi. Americanos: representações da identidade nacional no Brasil e nos EUA. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2000., in a book with a set of essays about the use of the concept of frontier and nature in a comparative form in Brazil and the United States.

-

4

RICARDO, Cassiano. Marcha para oeste: a influência da bandeira na formação social e política do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio, 1959.

-

5

IBGE. Anais do Oitavo Congresso Brasileiro de Educação, 1942, p.04.

-

6

IBGE. Anais do Oitavo Congresso Brasileiro de Educação, 1942, p.04.

-

7

IBGE. Anais do Oitavo Congresso Brasileiro de Educação, 1942.

-

8

According to Lenharo (1986)LENHARO, Alcir. Sacralização da política. Campinas: Papirus, 1986., one of aspects least analyzed in Brazilian historiography about the Estado Novo was how it dealt with rural questions. He argues that the historiographic emphasis privileges political character, urban processes linked to industrialization, and labor questions in the Estado Nacional. However, he shows that agricultural development and land occupation policies received a lot of investment from the regime, above all in colonization processes for the West. In this sense, it is important to identify the role in which the Oeste (West) appeared in Vargas’s programs. With Ricardo Cassiano being one of the central articulators of this, the expression Oeste could signify not only Central Brazil, but also Amazônia, Acre, and Rondônia, amongst others. According to Dutra e Silva (2017)DUTRA E SILVA, Sandro. No Oeste a terra e o céu: a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Brasil Central. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2017., Oeste came to be a more symbolic category than geographic, in which sense he defends that studies of the expansion of the frontier between the 1930s and 1950s cannot ignore the uses of this representation (RICARDO, Cassiano. Marcha para oeste: a influência da bandeira na formação social e política do Brasil).

-

9

Getulio Vargas. No limiar do ano de 1938. Saudação aos brasileiros, pronunciada no Palácio Guanabara e irradiada para todo o país, à meia noite de 31 de dez. 1937. Presidência da República Casa Civil, Secretaria de Administração, Diretoria de Gestão de Pessoas, Coordenação - Geral de Documentação e Informação, Coordenação de Biblioteca.

-

10

An expression used by Paulo Figueiredo, published in the first issue of the periodical Oeste (1942) to designate Goiânia.

-

11

IBGE was created by decree-law no. 218 from 26 January 1938, in reality just a change of names of two federal agencies (the National Institute of Statistics and the Brazilian Geographic Council) which already existed. Art. 10 of this decree stated: "The National Institute of Statistics shall henceforth be called the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, with the collegiate bodies controlling both — Geography and Statistics — being called the National Council."

-

12

ARTIAGA, Zoroastro. Geologia Econômica de Goiaz. Uberaba, 1947; Dos Índios do Brasil Central. Uberaba, 1947a; Contribuição para a História de Goiaz: Goiânia: mimeo, undated; Monografia Corográfica do Estado de Goiaz. Goiânia: mimeo undated; Minérios de Radium em Goiaz (ao Instituto de Pesquisas Tecnológicas de S. Paulo). Revista Oeste, ano II, n. 11, p.452-435, 1943; Minas e Goiaz. Revista Oeste, ano II, n.13, p.520-521, 1943a.

-

13

In 2002, the buildings constructed in the city of Goiânia in the 1930s and 1940s in an Art Déco style were considered by IPHAN as national architectural heritage, namely: 1) those in the praça cívica — the gazebo in the praça cívica, lights, the forum and courthouse, the residence of Pedro Ludovico Teixeira, the Goiano Zoroastro Artiaga Musuem, Obelisks with lights, Esmeraldas Palace, the Tax Office, Police Headquarters, the General Secretariat, the Clock Tower, and the Federal Regional Court; 2) isolated buildings: Goiânia Lyceum, the Grande Hotel, the Goiânia Theater, the Technical School, the Railway Station, the Trampoline and Wall of the Lago das Rosas; 3) the settlement of Campinas: Palace Hotel and Sub-Mayoral Office, and the Forum of Campinas, MANSO, 2004MANSO, Celina Fernandes Almeida. Goiânia: uma concepção urbana, moderna e contemporânea. Goiânia: Edição do autor, 2004.; DAHER, 2003DAHER, Tânia. Goiânia: uma utopia europeia no Brasil. Goiânia: Instituto Centro Brasileiro de Cultura, 2003..

-

14

The group consisted of regional politicians who were responsible for creating a number of institutions in Goiás, including the Historical and Geographic Institute of Goiás, the Institute of Lawyers of Goiás, and the Goiana Academy of Letters. They were part of the political group of the Interventor Pedro Ludovico Teixeira, especially the following: Colemar Natal e Silva, Dario Delio Cardoso, Agnelo Arlington Fleury Curado, Alcides Celso Ramos Jubé, Francisco Ferreira de Santos Azevedo, and Joaquim Carvalho Ferreira, amongst others.

-

15