ABSTRACT

Meningococcal meningitis is a well established potential fatal infection characterized by fever, headache, petechial rash, and vomiting in the majority of cases. However, protean manifestations including abdominal pain, sore throat, diarrhea and cough, even though rare, should not be overlooked. Similarly, although disseminated infection could potentially involve various organ-targets, secondary immune related complications including joints or pericardium should be dealt with caution, since they remain unresponsive to appropriate antibiotic regimens. We hereby report the rare case of an otherwise healthy adult female, presenting with acute abdominal pain masking Neisseria meningitidis serotype B meningitis, later complicated with recurrent reactive pericarditis despite appropriate antibiotic treatment. There follows a review of current literature.

Keywords:

Reactive pericarditis; Neisseria meningitidis; Meningococcal meningitis

Introduction

Meningococcal meningitis represents a severe - potentially fatal - infection characterized by fever, headache, petechial rash, and vomiting. Increased clinical suspicion and prompt diagnosis is pivotal to ensure favorable outcomes. However, uncommon manifestations including abdominal pain, cough, arthritis, vasculitis, or pericarditis can mislead the attending physician, while requiring combined treatment with agents other than appropriate antibiotics. Acute abdominal pain as initial manifestation of meningococcal infection is extremely uncommon, typically located around the right abdomen - commonly around the right iliac fossa. It can be commonly mistaken for acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, or mesenteric adenitis. Therefore, patients tend to initially present to surgical emergency departments. Pericarditis is also an uncommon (3-19%) but well-recognized complication of meningococcal disease.11 Beggs S, Marks M. Meningococcal pericarditis in a 2-year-old child: reactive or infectious?. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:606-8. Presence of multiple factors differentiate between direct invasion by the organism (disseminated meningococcal disease with pericarditis or isolated meningococcal pericarditis), from an immune mediated reactive pericarditis (RMP).11 Beggs S, Marks M. Meningococcal pericarditis in a 2-year-old child: reactive or infectious?. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:606-8. We hereby report the case of a 28-year-old otherwise healthy female presenting in our surgical department with acute abdomen masking meningococcal meningitis, later complicated by recurrent episodes of reactive pericarditis, despite appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Case report

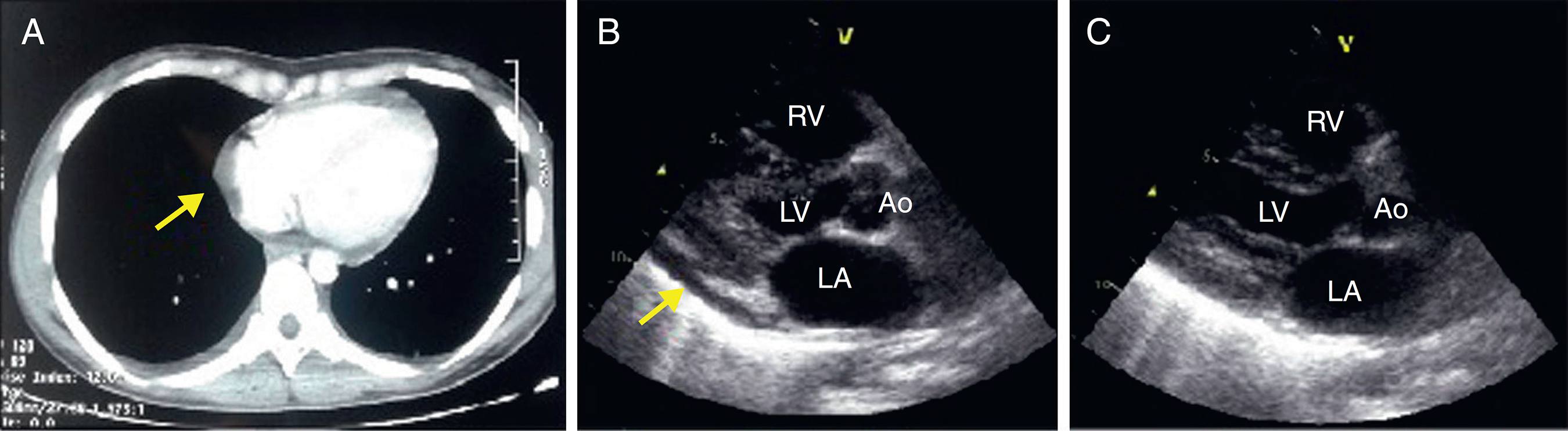

A 28-year-old Caucasian female presented at our hospital complaining of fever, rigors, and severe epigastric pain, not subsiding following non steroid anti-inflammatory drug administration, during the last 24 h. Upon admission the patient was in poor condition, BP:120/80 mmHg, T: 38.8 °C, GCS: 15/15, while physical examination revealed severe rebound tenderness along right upper quadrant and epigastrium. Blood tests came back to show WBC: 19.51 K/µL (92.5/2.7/4.7%), PLT: 117.00 K/µL, PT: 18.4 s, INR: 1.59, and CRP: 26 IU/L. Electrocardiogram (EKG) and chest-X-ray (CXR) were unremarkable. An emergency abdominal ultrasound and later CT scan did not reveal any cause of acute abdomen. Interestingly, the patient started complaining of headache during her stay in the emergency department. At the time, patient reassessment revealed increased nuchal rigidity and Kerning's sign suggestive of central nervous system involvement. Lumbar puncture revealed 15,200 cells of polymorphonuclear predominance, Glu < 5 mg/dl and protein 530 mg/dl in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF latex agglutination test and later CSF and blood cultures results showed Neisseria meningitidis group B sensitive to a range of antibiotics, hence the patient (following prior empiric therapy of vancomycin, ceftriaxone and dexamethasone) was put on ceftriaxone 4 gr qd. The patient presented dramatic clinical improvement a week following IV therapy with near normalization of inflammatory markers while serology for common viruses, including HIV and consecutive blood cultures came back negative. C3 and C4 complement concentrations were also normal. Ten days post-admission the patient started complaining of a sharp retrosternal pain radiating to the left scapula, associated with pericardial friction rub along the lower left sterna border. No alterations in hemodynamic, ABG, or other blood parameters including serum troponin I and creatine kinase MB were noted. However, EKG showed raised ST segments in leads V2-V6, indicative of pericarditis. Chest CT scan and cardiac ultrasound confirmed development of moderate pericardial effusion (Fig. 1A and B). In the context of previous clinical improvement, negative serology for infectious and autoimmune diseases, and presence of medication - sensitive meningococcus strain, we decided that pericarditis was immune- mediated and a combination of methylprednisolone and colchicine at 24 mg and 0.5 mg qd, respectively, was initiated. The patient showed clinical and radiologic improvement and was discharged 19 days post admission on a tapering scheme of corticosteroids (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, approximately one and a half months later - at the time on 4 mg of methylprednisolone - the patient started complaining again of retrosternal pain. She visited a tertiary hospital where recurrence of moderate pericardial fluid was confirmed, while reinstitution of methylprednisolone 8 mg/d and ibuprofen 600 mg/tid was followed by gradual improvement and discharge shortly after. Since then, the patient has again presented in our department twice with recurrent pericarditis while on methylprednisolone tapering. After eight months of follow up and slow tapering scheme of corticosteroids and NSAIDs the patient remains in excellent condition, without symptoms and out of treatment.

(A) Chest CT scan; (B) cardiac ultrasound (parasternal long axis view) revealed the presence of mild-to-moderate amount of pericardial effusion with no hemodynamic derangement (yellow arrows); and (C) no pericardial effusion was noted, following 9 days of corticosteroid therapy. Ao, aorta; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium.

Discussion

Acute abdominal pain as an initial manifestation of meningococcal infection is extremely uncommon, and can present both as an isolated entity, as well as in the context of meningococcal sepsis. Including ours, we have tracked no more than 19 cases of sharp abdominal pain as initial presentation of invasive meningococcal disease in global literature (Table 1). Despite equally involving adults and children, more than half (60%) of childhood cases are under six years of age.22 Sanz Álvarez D, Blázquez Gamero D, Ruiz Contreras J. Abdominal acute pain as initial symptom of invasive meningococcus serogroup A illness. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011;109:e39-e41.

3 Bannatyne RM, Lakdawalla N, Ein S. Primary meningococcal peritonitis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;117:436.

4 Kunkel MJ, Brown LG, Bauta H, Iannini PB. Meningococcal mesenteric adenitis and peritonitis in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3:327-8.

5 Tomezzoli S, Juárez Mdel V, Rossi SI, Lema DA, Barbaro CR, Fiorini S. Acute abdomen as initial manifestation of meningococcemia. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2008;106:260-3.

6 Winrow AP. Abdominal pain as an atypical presentation of meningococcaemia. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:227-9.-77 de Souza AL, Seguro AC. Meningococcal pericarditis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:651. Based on available data, Neisseria meningitidis serotype C was the most frequently isolated pathogen (∼48% of cases).33 Bannatyne RM, Lakdawalla N, Ein S. Primary meningococcal peritonitis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;117:436.,44 Kunkel MJ, Brown LG, Bauta H, Iannini PB. Meningococcal mesenteric adenitis and peritonitis in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3:327-8.,77 de Souza AL, Seguro AC. Meningococcal pericarditis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:651.

8 Herault T, Stoller J, Liard-Zmuda A, Mallet E. Peritonitis as a first manifestation of Neisseria type C meningitis. Arch Pediatr. 2006;13:456-8.

9 Hsia RY, Wang E, Thanassi WT. Fever abdominal pain, and leukopenia in a 13-year-old: a case-based review of meningococcemia. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:21-8.

10 Grewal RP. Atypical presentation of a patient with meningococcaemia. J Infect. 1993;27:344-5.

11 Kelly SJ, Robertson RW. Neisseria meningitidis peritonitis. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:182-3.

12 Schmid ML. Acute abdomen as an atypical presentation of meningococcal septicaemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:629-30.-1313 Weintraub MI, Gordon B. Letter acute abdomen with meningococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:808. Two cases of serotype B, similar to our case, have also been identified, even though the former involving children.55 Tomezzoli S, Juárez Mdel V, Rossi SI, Lema DA, Barbaro CR, Fiorini S. Acute abdomen as initial manifestation of meningococcemia. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2008;106:260-3.,66 Winrow AP. Abdominal pain as an atypical presentation of meningococcaemia. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:227-9. Fever was the most frequent accompanying symptom while a surgical procedure following suspicion of acute abdomen was conducted in 42% of these patients.33 Bannatyne RM, Lakdawalla N, Ein S. Primary meningococcal peritonitis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;117:436.

4 Kunkel MJ, Brown LG, Bauta H, Iannini PB. Meningococcal mesenteric adenitis and peritonitis in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3:327-8.-55 Tomezzoli S, Juárez Mdel V, Rossi SI, Lema DA, Barbaro CR, Fiorini S. Acute abdomen as initial manifestation of meningococcemia. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2008;106:260-3.,77 de Souza AL, Seguro AC. Meningococcal pericarditis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:651.,88 Herault T, Stoller J, Liard-Zmuda A, Mallet E. Peritonitis as a first manifestation of Neisseria type C meningitis. Arch Pediatr. 2006;13:456-8.,1111 Kelly SJ, Robertson RW. Neisseria meningitidis peritonitis. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:182-3.,1414 Bar-Meir S, Chojkier M, Groszmann RJ, Atterbury CE, Conn HO. Spontaneous meningococcal peritonitis: a report of two cases. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23:119-22. The etiology of abdominal pain remains obscure. Several theories attempt to explain the underlying pathophysiology associated with this clinical entity including, mesenteric hypoperfusion, septic epiploic micro infarctions, splanchnic invasion via hematogenous spread or ascending infection from the urogenital tract, or immune complex deposition.22 Sanz Álvarez D, Blázquez Gamero D, Ruiz Contreras J. Abdominal acute pain as initial symptom of invasive meningococcus serogroup A illness. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011;109:e39-e41.

Contrary to purulent pericarditis, RMP represents a late complication and very few cases have been reported in literature.11 Beggs S, Marks M. Meningococcal pericarditis in a 2-year-old child: reactive or infectious?. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:606-8.,1515 Chiappini E, Galli L, de Martino M, De Simone L. Recurrent pericarditis after meningococcal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:692-3.

16 El Bashir H, Klaber R, Mukasa T, Booy R. Pericarditis after meningococcal infection: case report of a child with two distinct episodes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:279-81.

17 Dupont M, du Haut Cilly FB, Arvieux C, Tattevin P, Almange C, Michelet C. Recurrent pericarditis during meningococcal meningitis. 2 case reports. Presse Med. 2004;33:533-4.

18 Lachenmayer ML, Mummel P, Beiderlinden K, Maschke M. Auto-immune reactive polyserositis in meningococcal meningoencephalitis: a case report. J Neurol. 2006;253:806-8.-1919 Stange K, Damaschke HJ, Berwing K. Secondary immunologically-caused myocarditis, pericarditis and exudative pleuritis due to meningococcal meningitis. Z Kardiol. 2001;90:197-202. It develops most frequently 6-15 days after onset of illness and is characterized by a type 3 hypersensitivity reaction, either against the specific serotype of the N. meningitidis or newly antigenic, damaged pericardial tissue because of molecular mimicry with microbial antigens.2020 Goedvolk CA, von Rosenstiel IA, Bos AP. Immune complex associated complications in the subacute phase of meningococcal disease: incidence and literature review. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:927-30. Severe disease, age (adults and young teenagers), and serogroup C seems to predispose to post-infectious immune associated complications including arthritis, vasculitis, pleuritis, or pericarditis.1515 Chiappini E, Galli L, de Martino M, De Simone L. Recurrent pericarditis after meningococcal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:692-3.,1616 El Bashir H, Klaber R, Mukasa T, Booy R. Pericarditis after meningococcal infection: case report of a child with two distinct episodes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:279-81.,2020 Goedvolk CA, von Rosenstiel IA, Bos AP. Immune complex associated complications in the subacute phase of meningococcal disease: incidence and literature review. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:927-30. In line with these observations, our patient was a young adult, presenting in poor clinical condition, with highly elevated inflammatory markers suggestive of severe disease, even though interestingly serogroup B (and not C) was finally isolated. The pericardial fluid in RMP is serous and sterile, and is often associated with polyserositis not responsive to antibiotics but to NSAIDs.11 Beggs S, Marks M. Meningococcal pericarditis in a 2-year-old child: reactive or infectious?. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:606-8.,1818 Lachenmayer ML, Mummel P, Beiderlinden K, Maschke M. Auto-immune reactive polyserositis in meningococcal meningoencephalitis: a case report. J Neurol. 2006;253:806-8. RMP may be more severe than purulent pericarditis and cardiac tamponade can be relatively frequent requiring high dosages of steroids and/or pericardiocentesis.2020 Goedvolk CA, von Rosenstiel IA, Bos AP. Immune complex associated complications in the subacute phase of meningococcal disease: incidence and literature review. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:927-30. Recurrent pericarditis is exceptionally rare after the meningococcal infection (Table 2), while the reasons of its recurrence remain unknown, even though genetic factors have been proposed.1515 Chiappini E, Galli L, de Martino M, De Simone L. Recurrent pericarditis after meningococcal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:692-3.

16 El Bashir H, Klaber R, Mukasa T, Booy R. Pericarditis after meningococcal infection: case report of a child with two distinct episodes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:279-81.

17 Dupont M, du Haut Cilly FB, Arvieux C, Tattevin P, Almange C, Michelet C. Recurrent pericarditis during meningococcal meningitis. 2 case reports. Presse Med. 2004;33:533-4.-1818 Lachenmayer ML, Mummel P, Beiderlinden K, Maschke M. Auto-immune reactive polyserositis in meningococcal meningoencephalitis: a case report. J Neurol. 2006;253:806-8. In these cases, the course of the disease may be chronic and unpredictable, regardless of the therapy given or the triggering cause, while corticosteroid use can induce severe dependence.

Conclusion

It would be intriguing to hypothesize that severe disease - commonly associated with higher antigenic loads - could have triggered overt immune complex formation and later deposition to abdominal vascular bed and pericardium, responsible for initial presentation and secondary complication respectively. Careful initial examination, close observation and high clinical suspicion may be required so that an atypical presentation, as well as, manifestation during the course of the disease is not overlooked, even after appropriate antibiotic treatment of meningococcal meningitis has occurred.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

References

-

1Beggs S, Marks M. Meningococcal pericarditis in a 2-year-old child: reactive or infectious?. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:606-8.

-

2Sanz Álvarez D, Blázquez Gamero D, Ruiz Contreras J. Abdominal acute pain as initial symptom of invasive meningococcus serogroup A illness. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011;109:e39-e41.

-

3Bannatyne RM, Lakdawalla N, Ein S. Primary meningococcal peritonitis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;117:436.

-

4Kunkel MJ, Brown LG, Bauta H, Iannini PB. Meningococcal mesenteric adenitis and peritonitis in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3:327-8.

-

5Tomezzoli S, Juárez Mdel V, Rossi SI, Lema DA, Barbaro CR, Fiorini S. Acute abdomen as initial manifestation of meningococcemia. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2008;106:260-3.

-

6Winrow AP. Abdominal pain as an atypical presentation of meningococcaemia. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:227-9.

-

7de Souza AL, Seguro AC. Meningococcal pericarditis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:651.

-

8Herault T, Stoller J, Liard-Zmuda A, Mallet E. Peritonitis as a first manifestation of Neisseria type C meningitis. Arch Pediatr. 2006;13:456-8.

-

9Hsia RY, Wang E, Thanassi WT. Fever abdominal pain, and leukopenia in a 13-year-old: a case-based review of meningococcemia. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:21-8.

-

10Grewal RP. Atypical presentation of a patient with meningococcaemia. J Infect. 1993;27:344-5.

-

11Kelly SJ, Robertson RW. Neisseria meningitidis peritonitis. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:182-3.

-

12Schmid ML. Acute abdomen as an atypical presentation of meningococcal septicaemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:629-30.

-

13Weintraub MI, Gordon B. Letter acute abdomen with meningococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:808.

-

14Bar-Meir S, Chojkier M, Groszmann RJ, Atterbury CE, Conn HO. Spontaneous meningococcal peritonitis: a report of two cases. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23:119-22.

-

15Chiappini E, Galli L, de Martino M, De Simone L. Recurrent pericarditis after meningococcal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:692-3.

-

16El Bashir H, Klaber R, Mukasa T, Booy R. Pericarditis after meningococcal infection: case report of a child with two distinct episodes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:279-81.

-

17Dupont M, du Haut Cilly FB, Arvieux C, Tattevin P, Almange C, Michelet C. Recurrent pericarditis during meningococcal meningitis. 2 case reports. Presse Med. 2004;33:533-4.

-

18Lachenmayer ML, Mummel P, Beiderlinden K, Maschke M. Auto-immune reactive polyserositis in meningococcal meningoencephalitis: a case report. J Neurol. 2006;253:806-8.

-

19Stange K, Damaschke HJ, Berwing K. Secondary immunologically-caused myocarditis, pericarditis and exudative pleuritis due to meningococcal meningitis. Z Kardiol. 2001;90:197-202.

-

20Goedvolk CA, von Rosenstiel IA, Bos AP. Immune complex associated complications in the subacute phase of meningococcal disease: incidence and literature review. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:927-30.

-

21Austin RP, Field AG, Beer WM. Right lower quadrant abdominal pain, fever, and hypotension: an atypical presentation of meningococcemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:1713.e3-1713.e4.

-

22de Souza AL, Marques Salgado M, Romano CC, et al. Cytokine activation in purulent pericarditis caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C. Int J Cardiol. 2006;113:419-21.

-

23Demeter A, Gelfand MS. Abdominal pain and fever - an unusual presentation of meningococcemia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1327.

-

24Stephani U, Bleckmann H. Rare complications in a case of generalized meningococcal disease: immunologic reaction versus bacterial metastasis. Infection. 1982;10:23-7.

-

25Fuglsang Hansen J, Johansen IS. Immune-mediated pericarditis in a patient with meningococcal meningitis. Ugeskr Laeger. 2013;175:967-8.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Nov-Dec 2016

History

-

Received

16 Apr 2016 -

Accepted

2 Aug 2016