ABSTRACT

Purpose:

The purpose of the research is to understand how the organization can assign meaning to the emotional labor performed by salespeople in the experience store. For this, it was analyzed the sources of the meaning of the work in the process of managing the emotions realized by the salespeople.

Originality/value:

There are few studies in the international literature that proposed to articulate the meaning of work (Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski, 2010Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

) and management of emotions (Grandey, 2000Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95...

) and there is no research about it on the national level. Based on this gap, the present research proposes that the meaning of work and management of emotions are intrinsically related in the management field, as a way of homogenizing behaviors and feelings related to work and organization. The originality of the research is to explain how organizations can establish mechanisms of meaning to work and contribute to processes of management of emotions with a more genuine character, and, consequently, how this subjective form of the work contributes to the construction of the brand experience in the sales environment.

Design/methodology/approach:

This is qualitative research that occurred in an experienced store located in the city of São Paulo. The methodological strategy was to enter the universe of work of the salespeople, through participant observation technique, with the purpose of understanding and explaining how the sources of the meaning of the work can contribute in the process of management of the emotions realized by the salespeople. The Hermeneutics was adopted for data analysis.

Findings:

The research presents that the sources of the meaning of work promoted by the organization, such as "authenticity", "self-efficacy", "belonging", "self-esteem", "sense of purpose" and "transcendence" mobilizes the salespeople's genuine emotions toward organizational goals.

KEYWORDS

Meaning of work; Emotional Labor; Management of Emotions; Salespeople; Experience Store

RESUMO

Objetivo:

O objetivo da pesquisa é compreender como a empresa pode atribuir sentido ao trabalho emocional realizado por vendedores de uma loja de experiência. Para isso, analisou-se o papel das fontes de sentido do trabalho no processo de gerenciamento das emoções realizado pelos vendedores.

Originalidade/valor:

Observaram-se poucos estudos que se propuseram a apresentar uma articulação entre sentido do trabalho (Rosso, Dekas, & Wrzesniewski, 2010Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

) e gestão das emoções (Grandey, 2000Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95...

) na literatura internacional, não havendo pesquisas sobre tal temática no âmbito nacional. Partindo dessa lacuna, a presente pesquisa propõe que o sentido do trabalho e a gestão das emoções estão intrinsecamente relacionados no campo da gestão, como forma de homogeneizar condutas e sentimentos relacionados ao trabalho e à organização. A originalidade da pesquisa reside em explicar como as organizações podem estabelecer mecanismos de sentido ao trabalho e contribuir com processos de gestão das emoções com caráter mais genuíno. E, consequentemente, como essa formatação subjetiva do trabalho contribui para a construção da experiência da marca no ambiente de venda.

Design/metodologia/abordagem:

Trata-se de uma pesquisa qualitativa que ocorreu em uma loja de experiência localizada na cidade de São Paulo. A estratégia metodológica consistiu em adentrar o universo de trabalho dos vendedores, via observação participante, com o objetivo de compreender e explicar de que forma as fontes de sentido do trabalho podem contribuir no processo de gestão das emoções realizada pelos vendedores. Para análise de dados adotou-se a hermenêutica.

Resultados:

A pesquisa apresenta que as fontes de sentido do trabalho promovidas pela empresa, como "autenticidade", "autoeficácia", "pertencimento", "autoestima", "senso de propósito" e "transcendência", permitem mobilizar as emoções genuínas dos vendedores em direção aos objetivos organizacionais.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Sentido do trabalho; Trabalho emocional; Gestão das emoções; Vendedores; Loja de experiências

1. INTRODUCTION

The purpose of the research is to understand how the organization can assign meaning for the emotional labor performed by salespeople in the experience store. For this, it was analyzed the role of the sources of the meaning of work in the process of management of the emotions realized by salespeople. The question presented is relevant to organizational studies, because it provides possibilities for understanding the control of the experience exercised by the brand and, mainly, the control of the emotional aspects of the workers that involve this process of giving experience to the consumer.

It is understood that "brand experience is the strategies that seek to arouse feelings, sensations and cognitive and behavioral responses, from stimuli developed by the brand, seeking to give to the consumer memorable experiences" (Brakus, Schmitt & Zarantonello, 2009Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of marketing, 73(3), 52-68. doi:10.1509/jmkg.73.3.52

https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.3.52...

; Pine & Gilmore, 1999Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: work is theatre & every business a stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.). In this perspective, consumption is considered not only the acquisition or use of goods, services or experiences but a phenomenon that is produced through the work of several areas of the organization, such as salespeople and consumers (Gabriel, 2018Gabriel, Y. (2018). Work, consumption and capitalism. Consumption Markets & Culture, 21(2), 190-192.). These new forms of work, organized around consumption, are studied by some researchers in Organizational Studies scholarships (Andrade, 2015Andrade, D. P. (2015). Vigilância e controle dos afetos no trabalho: a gestão do capital emocional. 3º Simpósio Internacional LAVITS: Vigilância, Tecnopolíticas, Territórios. Retrieved from http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivos/lavits2015-anais/10/5.Resumo91.pdf

http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivo...

; Fontenelle, 2015Fontenelle, I. A. (2015). Prosumption: New articulations between work and consumption in the reorganization of capital. Ciências Sociais Unisinos, 51(1), 83. doi:10.4013/csu.2015.51.1.09

https://doi.org/10.4013/csu.2015.51.1.09...

; Gabriel, Korczynski, & Rieder, 2015Gabriel, Y., Korczynski, M., & Rieder, K. (2015). Organizations and their consumers: Bridging work and consumption. Organization, 22(5), 629-643. doi:10.1177/1350508415586040

https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415586040...

; McCann, 2014McCann, L. (2014). Just what is it that makes today's employee branding so different, so appealing? Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization, 14(1), 143-150.; Pettinger, 2015Pettinger, L. (2015). Work, consumption and capitalism. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.; Van Marrewijk & Broos, 2012Van Marrewijk, A., & Broos, M. (2012). Retail stores as brands: Performances, theatre and space. Consumption Markets & Culture, 15(4), 374-391. doi:10.1080/10253866.2012.659438

https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2012.65...

) that present the changes caused in the processes of management and work with the rise of the consumer. Among these changes, organizations began to demand subjective aspects of workers, as well as their emotions, as a way to attribute quality and constantly satisfy the consumer (Hochschild, 2012Hochschild, A. R. (2012). The outsourced self: Intimate life in market times. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.). In addition, we have identified studies that seek to understand the construction of the meaning of work aimed at producing consumption of goods and services (Brannan, Parsons & Priola, 2011Brannan, M. J., Parsons, E., & Priola, V. (eds.). (2011). Branded lives: The production and consumption of meaning at work. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.; McCann, 2014McCann, L. (2014). Just what is it that makes today's employee branding so different, so appealing? Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization, 14(1), 143-150.), but none of them explain from the perspective of emotional labor and management of emotions.

In view of the researches presented, this study is committed to understanding the relationship between the sources of the meaning of work and the process of management of the emotions to build the brand experience, proposing advances in understanding the transformations in the field of work and consumption. To reach the objectives, it is adopted qualitative research with participant observation, informal interviews, and hermeneutical analysis.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1 Meaning and meaningful of work in the context of work

The origin of the concept of the meaning of work has been attributed to the team of international researchers known as Meaning of Work (MOW), which in 1987 began to carry out quantitative research to identify the variables inherent in the concept and to compare the attributions of meanings in different countries and cultures. The researchers of MOW (1987)MOW International Research Team (1987). The Meaning of working. London, UK: Academic Press. understand that work, besides being a wage-earning occupation, creates and defines human existence because it is capable of assigning particular meanings to individuals and economic and social meanings to society. Thus, MOW researchers consider that the meaning of work is determined by individual choices and experiences, as well as by the organizational and environmental context in which the work occurs.

In the literature, it has been identified that the words "meaning" and "meaningful" have been adopted by the researchers as synonyms. For Tolfo (2015)Tolfo, S. R. (2015). Significados e sentidos do trabalho. In Bendassoli, P. F., & Borges-Andrade, J. E. (orgs.). Dicionário de psicologia do trabalho e das organizações. São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo., "meaning" and "meaningful" are the productions of individuals from their experiences with culture and society; therefore, they are interdependent concepts. The "meaning" refers to constructions collectively elaborated, amenable to generalizations according to the concrete historical, economic and social context. But "meaningful" consists of an individual concept related to social and historical constitution, as well as, the understanding of the meanings of collective experiences of everyday life (Tolfo, Coutinho, Baasch, & Cugnier, 2011Tolfo, S. R., Coutinho, M. C., Baasch, D., & Cugnier, J. C. (2011). Sentidos y significados del trabajo: Un análisis con base en diferentes perspectivas teóricas y epistemológicas en Psicología. Universitas Psychología, 10(1), 175-188.). According to Pratt and Ashforth (2003)Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline, 309-327., significance refers to the amount of meaning that something holds for an individual.

There is a wide variety of sources that potentially influences perceptions of meaning and significance of work, ranging from individual attitudes, organizational contexts to spiritual connections. According to Rosso, Dekas, and Wrzesniewski (2010)Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

, the context in which the work is carried out is considered one of the important sources of meaning, which can be analyzed through the design of tasks or characteristics of work, organizational mission, financial circumstances, and national culture. However, to understand how work becomes meaningful, it is necessary to identify the mechanisms that produce meanings. The authors understand that mechanisms are underlying factors that lead to a relationship between two variables, capturing the processes by which one variable influences the other, allowing understanding of the ways and the way of the relationships observed. To explain how the meaning of work is constructed, Rosso, Dekas, and Wrzesniewski (2010)Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

identified seven categories of mechanisms which work can be perceived as meaning or meaningful.

-

Authenticity: It can be understood as a sense of coherence or alignment between the behavior and perceptions about the "true" self and it can be identified through self-confidence, affirmation of personal identity, and personal involvement in work.

-

Self-efficacy: It can be understood as the beliefs of individuals regarding power and the ability to produce the desired effect or make a difference in the organization, this being related to the sense of control at work. It can occur through: autonomy and dominance of work, experience, and competence resulting from overcoming the challenges of their work, the perception of uniqueness and the ability to generate a positive impact on their organization, work groups, and others.

-

Self-esteem: It can be understood as the self-assessment of an individual, being a lasting feature and a malleable state that can be shaped by personal and collective experiences and achievements

-

Purpose: It can be understood as a sense of direction and intentionality in life. It is employed through 1. Meaning of work and 2. Value systems that provide a sense of purpose and allows guiding the behavior of the individual, it makes him discern about what is allowed or not.

-

Belonging: It can be understood as the experience of an individual's personal involvement, with feelings of connection to social groups through work that can provide meanings, helping them experience a positive sense of shared common identity, destiny or humanity with the others.

-

Transcendence: It's associated with the subordination of the individual to the groups. It is experiences or entities that transcend the self through the connection or contribution to something outside or greater than the self (for example, when the individual realizes that his work positively impacts the wider society or the world) and the experience of deliberate subordination of the individual to something external / and or greater than the self (e. g. the vision of an organization, the family, a collective society, a spiritual entity).

-

Cultural and interpersonal sensemaking: it focuses the understanding of how different types of meanings of work are constructed. Therefore, the cultural and interpersonal sensation encompasses the sociocultural forces that shape the meaning that people make of different aspects of their work.

Rosso, Dekas, and Wrzesniewski's study (2010)Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

presents a panorama of research on the meaning of work, identifying aspects related to concepts that are currently little explored in the international literature. In Brazil, recent research on the meaning of work in the field of business administration is largely centered on the understanding of the concept in different working groups (Bispo, Dourado, & Amorim, 2013Bispo, D. D. A., Dourado, D. C. P., & Amorim, M. F. D. C. L. (2013). Possibilidades de dar sentido ao trabalho além do difundido pela lógica do Mainstream: um estudo com indivíduos que atuam no âmbito do movimento Hip Hop. Organizações & Sociedade, 20(67), 717-731.doi:10.1590/S1984-92302013000400007

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-9230201300...

; Boas & Morin, 2016Boas, A. A. V., & Morin, E. M. (2016). Sentido do trabalho e fatores de qualidade de vida no trabalho: a percepção de professores brasileiros e canadenses. Revista Alcance, 23(3), 272-292. doi:10.14210/alcance.v23n3(Jul-Set). p. 272-292

https://doi.org/10.14210/alcance.v23n3...

; Kern, Costa, Bianchim, & dos Santos, 2018Kern, J., Costa, V. M. F., Bianchim, B. V., & Dos Santos, R. D. C. T. (2018). Um olhar sobre o sentido do trabalho para docentes de uma instituição de ensino superior pública. Revista Global Manager, 17(2), 106-123.; Lemos, Cavazotte, & de Souza, 2017Lemos, A. H. C, Cavazotte, F. D. S. C. N., & de Souza, D. O. S. (2017). De empregado a empresário: mudanças no sentido do trabalho para empreendedores. Revista Pensamento Contemporâneo em Administração , 11(5), 103-115. doi:10.12712/rpca.v11i5.836

https://doi.org/10.12712/rpca.v11i5.836...

), critical studies (Pereira, Dolcid & da Costa, 2016Pereira, A. M., Dolci, L. N., & da Costa, L. S. (2016). O sentido do trabalho no contexto da crise estrutural do capital. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Latino-Americanos, 6(2).; Rohm & Lopes, 2015Rohm, R. H. D., & Lopes, N. F. (2015). The new meaning of labour for the post-modern subject: A critical approach. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 13(2), 332-345. doi:10.1590/1679-395117179

https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395117179...

; Schweitzer, Gonçalves, Tolfo, & Silva, Spinelli-de-Sá, & Lemos, 2018Spinelli-de-Sá, J. G., & Lemos, A. H. D. C. (2018). Sentido do trabalho: Análise da produção científica brasileira. Revista ADM.MADE, 21(3), 21-39. doi:10.21714/2237-51392017v21n3p021039

https://doi.org/10.21714/2237-51392017v2...

) and the dynamics of the meaning of work (Palassi & da Silva, 2014Palassi, M. P, & da Silva, A. R. L. (2014). A dinâmica do significado do trabalho na iminência da privatização. Revista de Ciências da Administração, 16(38). doi:10.5007/2175-8077.2014v16n38p47

https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-8077.2014v1...

). Thus, the study on the meaning of work needs research with new perspectives and theoretical aspects, both in the international and national literature, such as the analysis of categories of work that involve the context of the "economy of experiences" and emotional labor.

2.2 Emotional labor and the management of emotion in a sales environment

Hochschild (1979Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551-575. doi:10.1086/227049

https://doi.org/10.1086/227049...

, 1983)Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. coined the concept of "emotional labor", or its synonym "management of emotion" to define the process in which workers take as reference an ideal pattern of feeling constructed in social interaction and, in this sense, it seeks to manage their emotions to fit them into an expectation, even when they do not feel them internally. Hochschild's analysis of the service-oriented economy says that the emotional labor is sold for a salary and therefore has an exchange value in the world of work. Today, academics have understood "emotional labor" as a comprehensive term that is related to an integrated process that includes emotional demands of work (external stimulus), emotional regulation (intrapsychic response), and emotional performance (interpersonal behavior) (Grandey & Gabriel, 2015Grandey, A. A., Rupp, D., & Brice, W. N. (2015). Emotional labor threatens decent work: A proposal to eradicate emotional display rules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 770-785. doi:10.1002/job.2020

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2020...

).

The emotional labor has found a fertile field in the service sector, especially in the sales arena, where organizations and clients expect employees to perform the "service with a smile," expressing positive emotions (such as warmth) and inhibiting others (such as, hassles) to meet the expectations of exhibition (Grandey, 2000Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95...

). For this, it is necessary to establish some emotional rules and standards to homogenize the conduct and attribute a quality to the services provided. Hochschild (1983)Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. points out the existence of two types of rules of emotional manifestation: the rules of expression and the emotional rules. The rules of expression are related to the emotions that must be publicly expressed through behavior, that is, they are conventions that guide the expressions that must be manifested on certain occasions. Emotional rules, however, are related to the affective states that are truly experienced internally by the individual, that is, it defines not only what to express, but what to feel at a given moment.

In addition, emotional labor has some emotional management strategies aimed at meeting the rules of expression determined by the organization: superficial action and deep action (Hochschild, 1983Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.). A considerable part of the literature on emotional labor in the service sector has focused on these two strategies as a way of analyzing changes in emotion management processes. The superficial action consists of a simulation or effort to manage the expressions and gestures that have emotional meanings in front of clients and other collaborators. In this sense, the emotions expressed do not match those genuinely felt and it's intended to comply with the emotional rules determined by the organization. On the other hand, deep action consists of a cognitive and expressions effort, which implies in truly changing the emotions felt to express the emotions determined by the organization. The third strategy involves the spontaneous and genuine emotion, in which the worker would truly feel the emotion required by the organization (Humphrey, Ashforth, & Diefendorff, 2015Humphrey, R. H., Ashforth, B. E., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). The bright side of emotional labor. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 749-769. doi:10.1002/job.2019

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2019...

); this third form has been empirically little studied.

Grandey and Gabriel (2015)Grandey, A. A., Rupp, D., & Brice, W. N. (2015). Emotional labor threatens decent work: A proposal to eradicate emotional display rules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 770-785. doi:10.1002/job.2020

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2020...

, some of the researchers on the subject, identified the existence of two theoretical perspectives that are decisive for the understanding of emotional labor. The first perspective refers to the congruence between the person and the work, that is, a person who has characteristics that fit the emotional requirements of the work, such as extroversion, positive affectivity, and emotional management skills. This perspective considers that people who fit the job better need to do less emotional labor. For Lam, Huo, and Chen (2017)Lam, W., Huo, Y., & Chen, Z. (2017). Who is fit to serve? Person-job/organization fit, emotional labor, and customer service performance. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 483-497. doi:10.1002/hrm.21871

https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21871...

, this type of congruence between person-work and person-organization is important for functions that require a direct relationship with clients, especially because employee perceptions fit their jobs and organizational values, commonly, it serves as the definers of their selling behavior. Therefore, it has been considered important to analyze and select the employees who have greater congruence between the work and the organization, so that deep action can occur with little effort (Dahiya, 2017Dahiya, A. (2017). Extroversion and emotional labour: A study on organized retail sector. International Journal of Research in Commerce & Management, 8(4).; Wang, Wang, & Hou 2016Wang, X., Wang, G., & Hou, W. C. (2016). Effects of emotional labor and adaptive selling behavior on job performance. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 44(5), 801-814. doi:10.2224/sbp.2016.44.5.801

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.5.80...

). The second perspective is related to the objective of emotion, that is, the worker uses emotional management as a strategy to align his / her emotions with the emotional requirements determined by the organization when it identifies discrepancies between them (Bhave & Glomb, 2014Bhave, D. P., & Glomb, T. M. (2016). The role of occupational emotional labor requirements on the surface acting-job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Management, 42(3), 722-741. doi:10.1177/0149206313498900

https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313498900...

).

Recent research has increasingly focused on demonstrating the role of emotional labor in attributing quality to service performance and client experience (Bhave & Glomb, 2016Bhave, D. P., & Glomb, T. M. (2016). The role of occupational emotional labor requirements on the surface acting-job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Management, 42(3), 722-741. doi:10.1177/0149206313498900

https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313498900...

; Gabriel, Acosta, & Grandey, 2015Grandey, A. A., Rupp, D., & Brice, W. N. (2015). Emotional labor threatens decent work: A proposal to eradicate emotional display rules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 770-785. doi:10.1002/job.2020

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2020...

; Hur, Han, Yoo, & Moon, 2015Hur, W. M., Han, S. J., Yoo, J. J., & Moon, T. W. (2015). The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Management Decision, 53(3), 605-624. doi:10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379

https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379...

; Lam, Huo, & Chen, 2017Lam, W., Huo, Y., & Chen, Z. (2017). Who is fit to serve? Person-job/organization fit, emotional labor, and customer service performance. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 483-497. doi:10.1002/hrm.21871

https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21871...

), showing that the choices of emotional labor strategies are directly related to the construction of the service experience. The deep action has been considered one of the most appropriate strategies for the management of emotion because it contributes to the salespeople, so they can receive positive responses from the consumer and increase their level of satisfaction (Delpechitre & Beeler, 2017Delpechitre, D., & Beeler, L. (2017). Faking it: Salesperson emotional intelligence's influence on emotional labor strategies and customer outcomes. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(1), 53-71. doi:10.1108/JBIM-08-2016-0170

https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-08-2016-017...

; Hur, Han, Yoo, & Moon, 2015Hur, W. M., Han, S. J., Yoo, J. J., & Moon, T. W. (2015). The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Management Decision, 53(3), 605-624. doi:10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379

https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379...

; Zhan, Wang, & Shi, 2016Zhan, Y., Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2016). Interpersonal process of emotional labor: The role of negative and positive customer treatment. Personnel Psychology, 69(3), 525-557. doi:10.1111/peps.12114

https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12114...

). The surface action, in turn, when used alone, has been considered ineffective in terms of quality of work performance and consumer satisfaction (Bhave & Glomb, 2016Bhave, D. P., & Glomb, T. M. (2016). The role of occupational emotional labor requirements on the surface acting-job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Management, 42(3), 722-741. doi:10.1177/0149206313498900

https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313498900...

). However, if emotional management strategies often have potential benefits in terms of organizational outcomes, such as customer satisfaction and contribution in building friendlier sales environments, on the other hand, from the employee's perspective it is presented as a form of pressure (Mishra & Choudhury, 2014Mishra, S., & Choudhury, D. (2014). Differential experiences of emotional labour and burnout among Indian professionals. ASBM Journal of Management, 7(2).; Singh & Glavin, 2017Singh, D., & Glavin, P. (2017). An occupational portrait of emotional labor requirements and their health consequences for workers. Work and Occupations, 44(4), 424-466. doi:10.1177/0730888417726835

https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888417726835...

).

In the last years many researchers have been bothering to better understand the dynamics of emotional labor (Brook, 2013Brook, P. (2013). Emotional labour and the living personality at work: Labour power, materialist subjectivity and the dialogical self. Culture and Organization, 19(4), 332-352. doi:10.1080/14759551.2013.827423

https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2013.82...

, Gabriel, Daniels, Diefendorff, & Greguras, 2015Gabriel, A. S., Acosta, J. D., & Grandey, A. A. (2015). The value of a smile: Does emotional performance matter more in familiar or unfamiliar exchanges? Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 37-50. doi:10.1007/s10869-013-9329-2

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9329-...

), the advantages and disadvantages of this form of work (Grandey, Wessel, & Steiner, 2015Wessel, J. L., & Steiner, D. D. (2015). Surface acting in service: A two-context examination of customer power and politeness. Human Relations, 68(5), 709-730. doi:10.1177/0018726714540731

https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714540731...

) and critical analyzes (Du Plessis & Sørensen, 2017Du Plessis, E. M., & Sørensen, P. K. (2017). An interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild: Critique and the sociology of emotions: Fear, neoliberalism and the acid rainproof fish. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(7/8), 181-187.doi:10.1177/0263276417739113

https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417739113...

; Hochschild, 2013Hochschild, A. (2013). The back and forth of market culture. Culture and Organization, 19(4), 368-370. doi:10.1080/14759551.2013.827425

https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2013.82...

; Linehan & O'Brien, 2017Linehan, C., & O'Brien, E. (2017). From tell-tale signs to irreconcilable struggles: The value of emotion in exploring the ethical dilemmas of human resource professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(4), 763-777. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3040-y

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3040-...

; Willig, 2017Willig, R. (2017). An interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild: Critique as emotion. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(7/8), 189-196. doi:10.1177/0263276417739787

https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417739787...

) of work in service organizations. In Brazil, there are still few studies about emotional labor. Recent research has been worrying about how emotional labor is appropriate for several areas of the service sector (Bolzano, Moreno, Sauerbronn, Oliveira, & Pestana, 2015), the role of emotions in the economy of experiences (Andrade, 2015Andrade, D. P. (2015). Vigilância e controle dos afetos no trabalho: a gestão do capital emocional. 3º Simpósio Internacional LAVITS: Vigilância, Tecnopolíticas, Territórios. Retrieved from http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivos/lavits2015-anais/10/5.Resumo91.pdf

http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivo...

) and point out the differences in the management process (Rodrigues & Gondim, 2014Rodrigues, A. P.G, & Gondim, S. G. (2014). Expressão e regulação emocional no contexto de trabalho: Um estudo com servidores públicos. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 15(2), 38-65. doi:10.1590/S1678-69712014000200003.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-6971201400...

). Finally, we do not identify in the international and national literature research that addresses the relationship between emotional labor and the meaning of work, specifically on how the sources of work sense can contribute to the process of management of the emotions by salespeople.

3. METHODOLOGY

The studies about the concept of emotional labor or management of emotions involve the sociological analyzes by Hochschild (1979Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551-575. doi:10.1086/227049

https://doi.org/10.1086/227049...

, 1983)Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. that treats the issue of emotions in the workplace from the subjective experience of the individual. Therefore, researchers often adopt qualitative research and take an interpretative approach to understand how emotions management in the workplace occurs. The present research follows this methodological trend and adopts as a data collection strategy the technique of participant observation with informal interviews and hermeneutic analysis.

3.1 Data collection and data analysis

The field research was carried out in the experience store of a Brazilian brand of eyeglasses, located in the city of São Paulo, by the first author of this article. The brand chosen is known in the market, mainly for the business strategy focused on middle-class consumers, from sales kiosks and stores with salespeople of various styles. However, the brand experience store is aimed at reaching consumers in the wealthier classes by offering a different kind of brand experience consumption, which involves leisure, entertainment, and emotional stimulation during interactions with consumers.

The access to the field occurred through direct contact with the brand's office, presenting the scope and research interest to the company's public relations department. The first author of this article was given permission to access the brand experience store and began the participant research in October 2014, ending in December of the same year. In the end, it counted the total of 385 hours and 20 minutes of observation-participant. The participant-observation technique consisted of the real participation in the work routine of the studied group, allowing understanding of what it means to be a participant in a particular social situation-understanding how the context influences the behavior of the individual and how the behavior of the individual influences the social context (Shah & Corley, 2006Shah, S. K., & Corley, K. G. (2006). Building better theory by bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1821-1835. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00662.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006...

).

At the beginning of the research, the first author presented herself to the group of salespeople as a researcher and it was informed about the general objective of the research, the research tools (notebook and, eventually, the use of a recorder with consent of the group/individual) and confidentiality of the inquired participants. In addition to the organization's prior agreement, the salespeople were receptive throughout the inquiry period.

The researcher followed the same work routine as the salespeople, visited the same restaurant and snack bars frequented by the salespeople and she remained accessible to talk about the role of the researcher and the general objectives of the research. All these strategies had the objective of generating confidence in the communication process and to facilitate the exchange of information. The researcher-participant joined the team of salespeople, wore the uniform and changed her glasses by one of the brands, the latter by encouragement from the salespeople. She participated as a listener to eight interviews for the salesperson function, five brand-promoted pieces of training for new and veteran salespeople, the effective sales work in the store environment, as a listener for feedback meetings promoted by store management, events promoted by the brand-an exclusive for salespeople and franchisee, and two others, open to the public.

The researcher adopted to record the observations: notebook, images, recordings, and transcriptions of speeches. In addition to visual observation, the researcher positioned herself as a listener of every day speeches and conducted informal interviews to obtain more precise information about the phenomenon. The observation protocol was established based on the mechanisms of the meaning of work (Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski 2010Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

) and emotion management strategies (Grandey, 2000Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95...

), presented in the theoretical framework of the present research.

Regarding "work sense mechanisms", the observation was oriented in the identification of experiences of authenticity, self-efficacy, self-esteem, purpose, belonging, transcendence and cultural and interpersonal sensemaking (Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski 2010Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

). In relation to the management of emotions, it sought to identify the emotional rules of the organization and to highlight the use of deep action, superficial action and genuine expressions (Grandey, 2000Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95...

; Hochschild, 1983Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.). Secondly, after the data collected, the second category of reading and analysis orientation is included: the "emotional congruence between person-work and person-organization"' (Grandey & Gabriel, 2015Gabriel, A. S., Acosta, J. D., & Grandey, A. A. (2015). The value of a smile: Does emotional performance matter more in familiar or unfamiliar exchanges? Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 37-50. doi:10.1007/s10869-013-9329-2

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9329-...

; Lam, Huo, & Chen, 2017Lam, W., Huo, Y., & Chen, Z. (2017). Who is fit to serve? Person-job/organization fit, emotional labor, and customer service performance. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 483-497. doi:10.1002/hrm.21871

https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21871...

)

The hermeneutics proposed by Geertz (2001)Geertz, C. (2001). Interpretação das culturas. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: LTC., which privileges culture as an object of study, was adopted through the interpretation of the meanings of social practices that are presented by several individuals in a given reality and context. The interpretation followed a procedure organized in three stages. Firstly, the categories presented in the observer protocol mentioned in the previous paragraph were considered for reading and identification of related codes. Then, the researcher identified units of meanings (codes) that could be grouped and categorized (Gibbs, 2009Gibbs, G. (2009). Análise de dados qualitativos: Coleção pesquisa qualitativa. Rio Grande do Sul, RS: Bookman.). In the third and last step, the data treated are compared with the theoretical reference.

4. FINDINGS

4.1 Mechanism of the meaning of work and the construction of emotional labor

4.1.1 Emotional requirements for work

There is a concern of the organization during the process of hiring salespeople in identifying the emotional alignment between the person-organization and the person-work (Grandey & Gabriel, 2015Grandey, A. A., Rupp, D., & Brice, W. N. (2015). Emotional labor threatens decent work: A proposal to eradicate emotional display rules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 770-785. doi:10.1002/job.2020

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2020...

; Lam, Huo, & Chen, 2017Lam, W., Huo, Y., & Chen, Z. (2017). Who is fit to serve? Person-job/organization fit, emotional labor, and customer service performance. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 483-497. doi:10.1002/hrm.21871

https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21871...

). This process occurs at the moment of the interview with the manager of the store, which seeks to identify in the person-work perspective the "personality of the individual", that is, personal characteristics that can add to the brand. Does the interviewer ask the candidate "how can he contribute to the brand?" And "how does he deal difficult clients?" The questions are intended to identify the individual's belief in the power and ability to make a difference or produce the expected by the organization in the sales environment, evidencing a sense of control and dominance under the work. It is important for the organization to identify if the candidate is able to develop good personal interactions and if he/she has the skills to express positive emotions, such as "sympathy", "empathy", "being extroverted" and "excited", that favor compliance with the emotional rules of the company.

In addition, it seeks to identify the life goals of the candidates and how the work is mentioned as a means to reach their goals. Allied to this, the interviewer looks for emotions such as "enthusiasm", "attitude", "desire" and "ambition", that is, emotions that favor the achievement of results, to work in the sales function. Such emotional requirements may allow personal involvement of the individual with work and the development of abilities to overcome the challenges of function-such as compliance with emotional rules-in the name of their purposes and intentionality of life.

I want one day to open my own store, to have my own business. Be an entrepreneur, you know?! But before that, I want to go to university, I want to do everything right. I would like to study marketing, I think it's important. […] Nothing was easy for me, but you have to run and work hard to achieve it. (candidate 3, speech transcription, field notes).

[I look for] people who want to be here, to have something to offer to the brand, that has personality, enthusiasm, and desire to grow. You do not need to have experience in the role, but you must have an open mind in order to capture new ways of working and new concepts. (store manager, informal conversation after interviews with candidates for salespeople vacancies, field notes, speech transcription).

In the person-organization perspective, the "emotional relationship between the candidate and the brand" is observed, for example, from knowledge about "brand history", "admiration by the founder", "consumer relation" and "admiration for brand and its values", which reveal the effective link and the desire to be part of the group. For the organization, this previous connection with the brand can contribute with a sense of belonging and authenticity of the individual in relation to the work.

This stage presents the organization's efforts to identify, during the interviews, the emotional alignment between the person and the person-job-organization necessary for the individual to feel himself/herself authentic and involved with the function. Thus, meaning is derived from the feeling of immersion at work (Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski 2010Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

), through the experience of alignment between the genuine emotions of the individual, the emotional rules of function and the personal relationship with the brand.

4.1.2 The construction of emotional labor and its meanings

The role of emotions in the context of salespeople's work is greatly emphasized in training. The organization encourages salespeople to engage in work, which occurs through the commitment to express positive emotions during interactions with consumers.

We work in an organization that is really moved by emotion, [brand] if you don't have an emotion you cannot work. The salespeople's job is much more emotional, the faster the salesperson learns this the more financial return he'll have on sales. (Training Analyst, Speech Transcription).

The emotional rules of the organization are disseminated through shared discourses, strongly present in the group's daily life. The word "pepper" is adopted as a metaphor for representing positive emotions such as joy, good mood, and empathy that must be conveyed in interactions with consumers. Phrases such as "spice up people's lives", "express the pepper that is in you" and "have pepper in the vein", it is built with the verb in the infinitive and indicate the duty of action and the emotional rule determined by the organization. In addition, such discourses carry within themselves a sense of purpose and uniqueness to the group, the idea of a type of work that offers the opportunity to positively impact (or infect) people's lives through their emotions. Thus, the organization attributes to the work a greater sense of direction and intentionality for the group, that is, it is not just selling glasses, but using positive emotions to arouse consumers' senses, reaching not only the pockets but their hearts.

It's not what I say, it's the feeling I express for them. We must bring feelings to the customers. When I tell stories from a particular product, I am stimulating the senses and the imagination of the client. And that makes [the brand] different from any other organization in the business (Training Analyst, Speech Transcription)

In this way, it is possible to show that the "emotional rule", like the one that defines the emotions that must be manifested and truly experienced by the workers (Hochschild, 1983Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.), today requires sources of meaning and meaning that justifies their fulfillment. Thus, the company builds and offers a ready-for-seller purpose to assign meaning to their work, a life philosophy about how to be and relate positively to people.

This "sense of purpose," embedded in the organization's emotional rule through shared discourse, also leads salespeople to try to modify consumers' emotional state in sales interactions considered difficult-where consumers respond negatively to interaction. For example, when the salesperson sees the discomfort of the consumer over his ear adornment and constructs a narrative from his tool to establish a friendlier relationship, telling a story, teaching something new, and showing his personal feelings about adornment.

There are people who see and do not understand why we use them (ears reamers). It is preconception, but it does not know philosophy. Everything has an idea. This is fucking old. […] The story speaks of an Indian born without an umbilicus, who was not born from a woman. Therefore, the other Indians believed that he was a god and worshiped him. But the Sun God did not like this, he was nervous and wanted to kill the Indian. The Indian saw that the Sun God wanted to kill him but he fled. Then the Sun God threw an arrow toward the Indian. But the Indian was quick and the arrow struck only his ear. See, this has this idea for me, an homage to Kamukuca to help get out of trouble. (Salesman, speech transcription).

This process requires salespeople to adopt "deep action" strategies, a cognitive and emotional effort to manage their emotions to meet the emotional rules of the organization and influence consumer behavior (Hochschild, 1983Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.). However, the brand attributes as justification to use this technique as the opportunity of salespeople to exercise "self-confidence" and "self-connection" with genuine feelings, ignoring external moods and constructing "thoughts of self-esteem." The hope is that these efforts-cognitive and emotional-help the salespeople withstand the negative emotional load received from the client and also to express the positive emotions required by the organization.

When you meet a boring, grumpy, nervous or coarse client, imagine that this person has passed a terrible death in their family and is acting this way because they have not yet recovered. Or simply think that the client acts like this because he is not loved by his or her loved ones. You should then not contaminate yourself with these energies and show that you are superior to all of this, and then give back to the client a kind and polite response and behavior. If you do, treat him very kindly, politely and sometimes play with him, you will see that they will be ashamed to talk to you rudely and then "lower their guard" and become better with you. If you can do this, then you transmitted our peppermint virus! (Training Analyst, field notes)

[…] sometimes very thick clients come here in the store, I compliment them, I'm nice and sometimes respond stupidly and sometimes even ignore their presence […] get angry? Imagine! Look at me, my love! I am a beautiful, wonderful and happy with life. If he only has this to convey to people, I convey love. Each transmits what is within himself. (Saleswoman, speech transcription)

Thus, for emotional management itself to occur, the brand invites salespeople to seek and recover the meaning of their work, the "sense of self-control" and "dominance over self". For the brand to be able to deliver memorable consumer experience through sales interactions (easy or difficult) it is fundamental that the worker must be able to constantly manage his or her emotions through "deep action" or the "expression of genuine positive emotions." For the process to be effective, it is necessary that the worker perceives the meaning of his work and can self-justify the process of managing his emotions for himself.

The construction and transmission of emotional stimuli to consumers have led salespeople to perceive their capabilities in arousing positive feelings and reactions to consumers, especially in building customer-friendly relationships.

[I know the customer is well taken care of] when he does not leave the store without saying anything, when he thanks very much that he was very well attended, and he smiles. Sometimes the customer feels so good about the service and the context of the store that he thanks, and we say "no, thank you". This is because he feels important and sees the time you have spent in serving him and the way you have met and by the posture (Store Manager, field notes).

However, if this "sense of self-efficacy" proves to be positive in consumer interactions and stimuli, it does not always reflect the attainment of sales goals and wage bonus. The great emotional effort on the part of the salespeople to sell a commoditized product can only be justified by a job where it is given meaning and that guarantees the personal involvement necessary for the management of the emotions and the construction of stimuli to the consumers.

The salesperson who is not sufficiently involved and cannot find the meaning to work will have difficulty fulfilling this mission, to comply with the emotional demand demanded by the company and adopt the "deep action", therefore, tends to get out of the group. For example, a salesperson who took medication for depression and had difficulty relating to other salespeople and, in interactions with consumers, adopted superficial action strategies-this can be evidenced by the times the store manager asked him to change his facial expression, asking him to smile. These salespeople resigned from work, justifying that he "could not accept the job". In order to act effectively and at the same time achieve sales goals, the organization offers salespeople salary bonus, awards, participation in major national music and fashion events, participation in events promoted by the organization and job opportunities within and outside the country.

I think there is no brand in the world that provides what [the brand] is made by many people. (…) If I go back and see Daniel back there has had a radical change. I am here, literally a refugee from the world and such, but certainly to become a better person. (…) the universe [the brand] is a unique thing, the people who work, who do it with love, who understand what I'm talking about. So I'm in this, I'm growing in the brand, you nuts. I'm focused here. You can come and talk. If any company comes and offers me 'x' salary I will not accept it. Because I'm pepper, bro. I am this [the brand]! Old man, do you know what I'm talking about?! I am pepper, there is nothing else. (Sales Manager A-Store in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia-Video speech transcription)

Awards through experiences can be seen as a way of maintaining the emotional link between the person-organization and the person-work (Lam, Huo & Chen, 2017Lam, W., Huo, Y., & Chen, Z. (2017). Who is fit to serve? Person-job/organization fit, emotional labor, and customer service performance. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 483-497. doi:10.1002/hrm.21871

https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21871...

), that is, a means that stimulates and develops emotional competencies expected by the brand/organization, at the same time as it can be a mobilizer and regulator of the moods, aiming to sustain the behaviors emotionally (Andrade, 2015Andrade, D. P. (2015). Vigilância e controle dos afetos no trabalho: a gestão do capital emocional. 3º Simpósio Internacional LAVITS: Vigilância, Tecnopolíticas, Territórios. Retrieved from http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivos/lavits2015-anais/10/5.Resumo91.pdf

http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivo...

). In doing so, the organization sustains the sense of:

Self-esteem: It seeks to develop by offering memorable experiences to salespeople (trips on cruises, parties, brand events, major national events), promotions and acknowledgments about individual and group professional accomplishments. Self-efficacy: It reinforces the salespeople's perception of the importance, uniqueness and positive impact of their work in the organization. Belonging: It stimulates the sense of family, of shared identity and connection with the group, through events promoted by the brand. Purpose: Reinforces periodically, in each event of the brand, the role of the emotions in the business of the brand. The brand offers experiences that mobilize and regulate the emotions of salespeople as a way to maintain emotional behavior in the selling environment. Transcendence: It generates workers who deliberately subordinate themselves to the brand and its purposes.

Finally, it is observed that the work context aimed at the transmission of brand experience presents different types of constructions of meanings for emotional labor. It involves sociocultural and psychological forces, present in the work environment, that directly or indirectly shape the meaning that the individual attributes to his work (Rosso, Dekas & Wrzesniewski 2010Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.0...

) and contribute to the process of managing emotions and building a kind of work aimed at transmitting experiences to consumers.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

It can be concluded that the perception of the meaning of work is an important condition for emotional labor to occur less forcefully by the worker and produces the sales experience. The study reveals that the analysis of the emotions in the hiring phase is fundamental for the organization to identify the existence of emotional alignment between person-work (the capacity to meet the emotional requirements of the function) and person-organization (identification and prior bonding with the brand/organization). Here, meaning is derived from the immersion experience of the individual at work through the alignment between their genuine emotions, the emotional rules of function, and the personal relationship with the brand/organization.

In the context of work, the emotional rules of the organization are disseminated through discourses shared by the group that determines not only the emotions that must be transmitted but carried within them a sense of purpose that assigns direction and intentionality to work. The individual who is receptive to this purpose produced by the organization, realizing and accepting the mission of their work, will be able to carry out the emotional labor in a less forced way and to justify for themselves the efforts necessary for the management of their emotions.

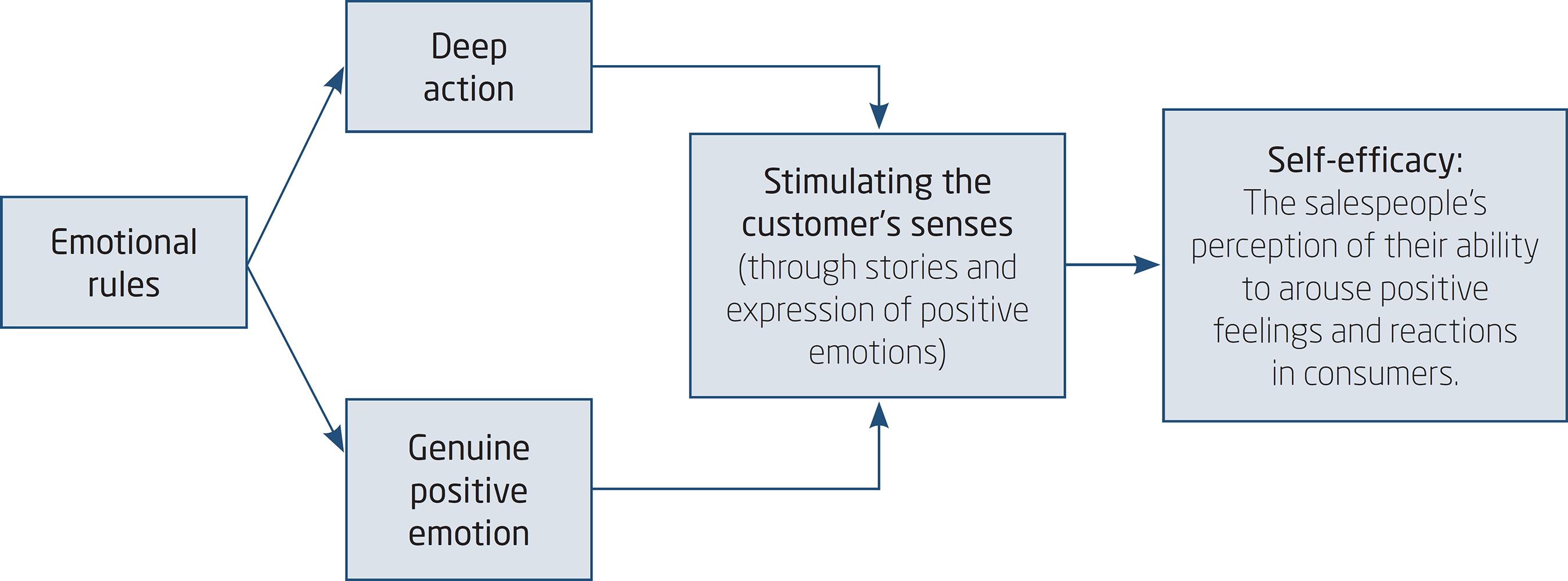

In addition to emotional rules, the organization uses awards and professional and festive experiences to stimulate and develop the emotional competencies expected by the brand, while mobilizing, regulating and sustaining the behavior of salespeople. These actions present innumerable sources that also seek to mobilize, regulate and sustain the perception of the salespeople of meaning of work are: self-esteem, self-efficacy, belonging and purpose. The Figure 5.1 below presents an overview of the construction of meaning for emotional labor.

Finally, the brand experience is built through an emotional labor that must be meaningful to those who carry it out, implying, on one hand, the obscuring of the real organizational objective, that it is selling its products and increasing sales revenue, and on the other hand to engage the consumer in a memorable experience. Research shows that, in the demand for self-management of emotions and the search for the meaning of work, organizations are increasingly appropriating the subjectivity of individuals, adopting, still, a lot of external control and discipline under the work. We do not know if this is due to the level of the function exercised, the characteristics of the organization itself, the cultural aspects of our country or other phenomena. This requires a deepening.

In relation to future studies, we suggest research that seeks a theoretical deepening of the relation between identification, affection, and enjoyment, since we have seen how these categories are intertwined in the analysis performed. Also, it is suggested understanding the meaningful and meaning of work for the prosumer individual, the one who performs the dual function in the context of work: worker and consumer. It is believed that the figure of the prosumer may reveal a new meaning of work in the consumer society.

REFERENCES

- Andrade, D. P. (2015). Vigilância e controle dos afetos no trabalho: a gestão do capital emocional. 3º Simpósio Internacional LAVITS: Vigilância, Tecnopolíticas, Territórios Retrieved from http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivos/lavits2015-anais/10/5.Resumo91.pdf

» http://medialabufrj.net/download/arquivos/lavits2015-anais/10/5.Resumo91.pdf - Bispo, D. D. A., Dourado, D. C. P., & Amorim, M. F. D. C. L. (2013). Possibilidades de dar sentido ao trabalho além do difundido pela lógica do Mainstream: um estudo com indivíduos que atuam no âmbito do movimento Hip Hop. Organizações & Sociedade, 20(67), 717-731.doi:10.1590/S1984-92302013000400007

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-92302013000400007 - Boas, A. A. V., & Morin, E. M. (2016). Sentido do trabalho e fatores de qualidade de vida no trabalho: a percepção de professores brasileiros e canadenses. Revista Alcance, 23(3), 272-292. doi:10.14210/alcance.v23n3(Jul-Set). p. 272-292

» https://doi.org/10.14210/alcance.v23n3 - Bolzan, P. D. (2016). Trabalho emocional e gênero: dimensões do trabalho no Serviço Social. Revista em Pauta, 13(36). doi:10.12957/rep.2015.21054

» https://doi.org/10.12957/rep.2015.21054 - Bhave, D. P., & Glomb, T. M. (2016). The role of occupational emotional labor requirements on the surface acting-job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Management, 42(3), 722-741. doi:10.1177/0149206313498900

» https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313498900 - Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of marketing, 73(3), 52-68. doi:10.1509/jmkg.73.3.52

» https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.3.52 - Brannan, M. J., Parsons, E., & Priola, V. (eds.). (2011). Branded lives: The production and consumption of meaning at work Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Brook, P. (2013). Emotional labour and the living personality at work: Labour power, materialist subjectivity and the dialogical self. Culture and Organization, 19(4), 332-352. doi:10.1080/14759551.2013.827423

» https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2013.827423 - Dahiya, A. (2017). Extroversion and emotional labour: A study on organized retail sector. International Journal of Research in Commerce & Management, 8(4).

- de Morais, F. J., Sauerbronn, J. F. R., Oliveira, J. S., & Pestana, F. N. (2015). Gestão das emoções em centrais de atendimento telefônico. Revista Pensamento Contemporâneo em Administração, 9(3). doi:10.12712/rpca.v9i3.507

» https://doi.org/10.12712/rpca.v9i3.507 - Delpechitre, D., & Beeler, L. (2017). Faking it: Salesperson emotional intelligence's influence on emotional labor strategies and customer outcomes. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(1), 53-71. doi:10.1108/JBIM-08-2016-0170

» https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-08-2016-0170 - Du Plessis, E. M., & Sørensen, P. K. (2017). An interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild: Critique and the sociology of emotions: Fear, neoliberalism and the acid rainproof fish. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(7/8), 181-187.doi:10.1177/0263276417739113

» https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417739113 - Fontenelle, I. A. (2015). Prosumption: New articulations between work and consumption in the reorganization of capital. Ciências Sociais Unisinos, 51(1), 83. doi:10.4013/csu.2015.51.1.09

» https://doi.org/10.4013/csu.2015.51.1.09 - Gabriel, Y., Korczynski, M., & Rieder, K. (2015). Organizations and their consumers: Bridging work and consumption. Organization, 22(5), 629-643. doi:10.1177/1350508415586040

» https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415586040 - Gabriel, A. S., Daniels, M. A., Diefendorff, J. M., & Greguras, G. J. (2015). Emotional labor actors: A latent profile analysis of emotional labor strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 863.doi:10.1037/a0037408

» https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037408 - Gabriel, Y. (2018). Work, consumption and capitalism. Consumption Markets & Culture, 21(2), 190-192.

- Gabriel, A. S., Acosta, J. D., & Grandey, A. A. (2015). The value of a smile: Does emotional performance matter more in familiar or unfamiliar exchanges? Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 37-50. doi:10.1007/s10869-013-9329-2

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9329-2 - Geertz, C. (2001). Interpretação das culturas Rio de Janeiro, RJ: LTC.

- Gibbs, G. (2009). Análise de dados qualitativos: Coleção pesquisa qualitativa Rio Grande do Sul, RS: Bookman.

- Gil, A. C. (2008). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social (6th ed.). São Paulo, SP: Atlas.

- Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

» https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95 - Grandey, A. A., & Gabriel, A. S. (2015). Emotional labor at a crossroads: Where do we go from here? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 323-349. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032 414-111400

» https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111400 - Grandey, A. A., Rupp, D., & Brice, W. N. (2015). Emotional labor threatens decent work: A proposal to eradicate emotional display rules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 770-785. doi:10.1002/job.2020

» https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2020 - Grant, A. M. (2013). Rocking the boat but keeping it steady: The role of emotion regulation in employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1703-1723. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0035

» https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0035 - Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551-575. doi:10.1086/227049

» https://doi.org/10.1086/227049 - Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Hochschild, A. R. (2012). The outsourced self: Intimate life in market times New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

- Hochschild, A. (2013). The back and forth of market culture. Culture and Organization, 19(4), 368-370. doi:10.1080/14759551.2013.827425

» https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2013.827425 - Humphrey, R. H., Ashforth, B. E., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). The bright side of emotional labor. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 749-769. doi:10.1002/job.2019

» https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2019 - Hur, W. M., Han, S. J., Yoo, J. J., & Moon, T. W. (2015). The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Management Decision, 53(3), 605-624. doi:10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379

» https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379 - Kern, J., Costa, V. M. F., Bianchim, B. V., & Dos Santos, R. D. C. T. (2018). Um olhar sobre o sentido do trabalho para docentes de uma instituição de ensino superior pública. Revista Global Manager, 17(2), 106-123.

- Lam, W., Huo, Y., & Chen, Z. (2017). Who is fit to serve? Person-job/organization fit, emotional labor, and customer service performance. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 483-497. doi:10.1002/hrm.21871

» https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21871 - Lemos, A. H. C, Cavazotte, F. D. S. C. N., & de Souza, D. O. S. (2017). De empregado a empresário: mudanças no sentido do trabalho para empreendedores. Revista Pensamento Contemporâneo em Administração , 11(5), 103-115. doi:10.12712/rpca.v11i5.836

» https://doi.org/10.12712/rpca.v11i5.836 - Linehan, C., & O'Brien, E. (2017). From tell-tale signs to irreconcilable struggles: The value of emotion in exploring the ethical dilemmas of human resource professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(4), 763-777. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3040-y

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3040-y - McCann, L. (2014). Just what is it that makes today's employee branding so different, so appealing? Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization, 14(1), 143-150.

- MOW International Research Team (1987). The Meaning of working London, UK: Academic Press.

- Mishra, S., & Choudhury, D. (2014). Differential experiences of emotional labour and burnout among Indian professionals. ASBM Journal of Management, 7(2).

- Palassi, M. P, & da Silva, A. R. L. (2014). A dinâmica do significado do trabalho na iminência da privatização. Revista de Ciências da Administração, 16(38). doi:10.5007/2175-8077.2014v16n38p47

» https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-8077.2014v16n38p47 - Pettinger, L. (2015). Work, consumption and capitalism London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pereira, A. M., Dolci, L. N., & da Costa, L. S. (2016). O sentido do trabalho no contexto da crise estrutural do capital. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Latino-Americanos, 6(2).

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: work is theatre & every business a stage Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

- Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline, 309-327.

- Rohm, R. H. D., & Lopes, N. F. (2015). The new meaning of labour for the post-modern subject: A critical approach. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 13(2), 332-345. doi:10.1590/1679-395117179

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395117179 - Rodrigues, A. P.G, & Gondim, S. G. (2014). Expressão e regulação emocional no contexto de trabalho: Um estudo com servidores públicos. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 15(2), 38-65. doi:10.1590/S1678-69712014000200003.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-69712014000200003 - Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001 - Schweitzer, L., Gonçalves, J., Tolfo, S. D. R., & Silva, N. (2016). Bases epistemológicas sobre sentido(s) e significado(s) do trabalho em estudos nacionais. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, 16(1), 103-116.

- Singh, D., & Glavin, P. (2017). An occupational portrait of emotional labor requirements and their health consequences for workers. Work and Occupations, 44(4), 424-466. doi:10.1177/0730888417726835

» https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888417726835 - Spinelli-de-Sá, J. G., & Lemos, A. H. D. C. (2018). Sentido do trabalho: Análise da produção científica brasileira. Revista ADM.MADE, 21(3), 21-39. doi:10.21714/2237-51392017v21n3p021039

» https://doi.org/10.21714/2237-51392017v21n3p021039 - Shah, S. K., & Corley, K. G. (2006). Building better theory by bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1821-1835. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00662.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00662.x - Tolfo, S. R. (2015). Significados e sentidos do trabalho. In Bendassoli, P. F., & Borges-Andrade, J. E. (orgs.). Dicionário de psicologia do trabalho e das organizações São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo.

- Tolfo, S. R., Coutinho, M. C., Baasch, D., & Cugnier, J. C. (2011). Sentidos y significados del trabajo: Un análisis con base en diferentes perspectivas teóricas y epistemológicas en Psicología. Universitas Psychología, 10(1), 175-188.

- Wang, X., Wang, G., & Hou, W. C. (2016). Effects of emotional labor and adaptive selling behavior on job performance. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 44(5), 801-814. doi:10.2224/sbp.2016.44.5.801

» https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.5.801 - Wessel, J. L., & Steiner, D. D. (2015). Surface acting in service: A two-context examination of customer power and politeness. Human Relations, 68(5), 709-730. doi:10.1177/0018726714540731

» https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714540731 - Willig, R. (2017). An interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild: Critique as emotion. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(7/8), 189-196. doi:10.1177/0263276417739787

» https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417739787 - Van Marrewijk, A., & Broos, M. (2012). Retail stores as brands: Performances, theatre and space. Consumption Markets & Culture, 15(4), 374-391. doi:10.1080/10253866.2012.659438

» https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2012.659438 - Zhan, Y., Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2016). Interpersonal process of emotional labor: The role of negative and positive customer treatment. Personnel Psychology, 69(3), 525-557. doi:10.1111/peps.12114

» https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12114

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

25 Mar 2019 -

Date of issue

2019

History

-

Received

30 Apr 2018 -

Accepted

13 July 2018

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.