Abstract

The aim of this survey was to determine the seropositivity and risk factors forLeishmania spp. and Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs in the State of Paraíba, Northeastern Brazil. A total of 1,043 dogs were tested, and the serological diagnoses of Chagas disease (CD) and canine visceral leishmaniasis (CVL) was performed by the indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT). Animals that tested seropositive for both diseases (by IFAT) were further subjected to ELISA. Of the 1,043 dogs 81 (7.8%; 95% CI = 6.1-9.4%) tested seropositive for Leishmania spp., while 83 were seropositive for T. cruzi (7.9%; 95% CI = 6.3-9.6%). Simultaneous serological reactions were detected in 49 animals (4.6%; 95% CI= 3.6-6.2%). Semi-domiciled housing (OR = 2.044), free housing (OR = 4.151), and soil (OR = 3.425) and soil/cement (OR = 3.065) environmental conditions were identified as risk factors for CVL seropositivity. The risk factors identified for CD seropositivity were semi-domiciled (OR = 2.353) or free housing (OR = 3.454), and contact with bovine (OR = 2.015). This study revealed the presence of dogs in the Paraíba State seropositive for CVL and CD, suggesting the need for revisiting and intensification of disease control measures through constant monitoring of the canine population.

Keywords:

Dogs; Leishmania infantum; Trypanosoma cruzi; risk factors; Northeastern region of Brazil

Resumo

O objetivo do presente trabalho foi determinar a soropositividade paraLeishmania spp. e Trypanosoma cruzi em cães do Estado da Paraíba, Nordeste do Brasil, bem como identificar fatores de risco. Foram utilizados 1.043 cães e, para o diagnóstico sorológico de doença de Chagas (DC) e leishmaniose visceral canina (LVC), foi utilizada a reação de imunofluorescência indireta (RIFI). Animais positivos para ambas as doenças (pela RIFI) foram submetidos ao ELISA. Dos 1.043 cães investigados, 81 foram soropositivos para Leishmania spp., resultando em prevalência de 7,8% (IC 95% = 6,1-9,4%) e, para T. cruzi, 83 (7,9%; IC 95% = 6,3-9,6%) animais foram soropositivos. Quarenta e nove animais (4,6%; IC 95% = 3,6-6,2%) apresentaram sororeatividade mista. Criação semidomiciliar (OR = 2,044), criação solta (OR = 4,151), ambiente de terra (OR = 3,425) e ambiente de terra/cimento (OR = 3,065) foram apontados como fatores de risco para LVC, e criação semidomiciliar (OR = 2,353), criação solta (OR = 3,454) e contato com bovinos (OR = 2,015) para DC. Conclui-se que LVC e DC estão presentes em cães do Estado da Paraíba, o que sugere revisão e intensificação das medidas de controle através do constante monitoramento da população canina.

Palavras-chave:

Cães; Leishmania infantum; Trypanosoma cruzi; fatores de risco; Nordeste do Brasil

Introduction

The zoonoses visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and Chagas disease (CD) have been known to significantly affect human health in Brazil, prompting the need for repeated medical assistance. These diseases are caused by the protozoans Leishmania infantum and Trypanosoma cruzi, respectively; both are known to be carried by hematophagous insect (Lutzomyia spp. andTriatoma spp.) vectors. Wild and domesticated canids have been identified as the reservoirs of these parasites (SIMÕES-MATTOS et al., 2005Simões-Mattos L, Mattos MRF, Teixeira MJ, Oliveira-Lima JW, Bevilaqua CML, Prata-Júnior RC, et al. The susceptibility of domestic cats (Felis catus) to experimental infection with Leishmania braziliensis.Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4): 199-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.10.008. PMid:15710520.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004....

; LUCIANO et al., 2009Luciano RM, Lucheis SB, Troncarelli MZ, Luciano DM, Langoni H. Avaliação da reatividade cruzada entre antígenos de spp e . LeishmaniaTrypanosoma cruzi na resposta sorológica de cães pela técnica de imunofluorescência indireta (RIFI)Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2009; 46(3): 181-187.).

Canine visceral leishmaniasis (CVL) is an important zoonosis, which is associated with rapid geographical expansion. This disease has been observed in 47 countries, and is caused by specie Leishmania (L.) infantum (KUHLS et al., 2011Kuhls K, Alam MZ, Cupolillo E, Ferreira GEM, Mauricio IL, Oddone R, et al. Comparative microsatellite typing of new world Leishmania infantum reveals low heterogeneity among populations and its recent old world origin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011; 5(6): e1155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001155. PMid:21666787.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0...

). The disease is widely distributed throughout Brazil, and presents specific geographical, climatic, and social characteristics. CVL, which was mostly diagnosed in rural areas in the past, has recently migrated to medium and large urban areas, which has led to changes in its epidemiological profile. In Brazil, CVL occurs in the central-western, southeastern, northern, and northeastern regions, however, the majority of cases have been reported in northeastern region (BRASIL, 2006Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Manual de vigilância e controle da Leishmaniose Visceral [online]. Brasília; 2006. Série A: Normas e manuais Técnicos [cited 2006 Oct 30]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_vigilancia_controle_leishmaniose_visceral.pdf

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoe...

).

Dogs are the major domestic reservoirs of VL, and play a major role in maintaining the disease cycle (MELO, 2004Melo MN. Leishmaniose Visceral no Brasil: desafios e perspectivas. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2004; 13(S1): 41-45.). Their relevance is attributed to the greater prevalence of VL in the canine than in the human population, since infections in humans are often preceded by infections in dogs. Furthermore, dogs carry a greater number of parasites on their skin than humans, which favors the infection of the vectors (CASTRO, 1996Castro AG. Controle, diagnóstico e tratamento da leishmaniose visceral (calazar): normas técnicas. Brasília: Fundação Nacional de Saúde; 1996.; SANTA ROSA & OLIVEIRA, 1997Santa Rosa ICA, Oliveira ICS. Leishmaniose Visceral: zoonose reemergente. Clin Vet 1997; 2(11): 24-28.; BANETH, 2006Baneth G. Leishmaniases. In: Greene CE. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 3th ed. Saint Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. p. 685-698.).

CD, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is a major public health concern in several countries around the world (BORCHHARDT et al., 2010Borchhardt DM, Mascarello A, Chiaradia LD, Nunes RJ, Oliva G, Yunes RA, et al. Biochemical evaluation of a series of synthetic chalcone and hydrazide derivatives as novel inhibitors of cruzain from Trypanosoma cruzi.J Braz Chem Soc 2010; 21(1): 142-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532010000100021.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532010...

). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 6 million people from 21 countries are estimated to be infected with CD, with an annual incidence of 100,000 to 200,000 cases (WHO, 2015World Health Organization – WHO. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) [online], Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2015 Mar 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheet...

). With regard to Brazil, it is estimated that the number of infected individuals is around of three million, and this zoonotic disease is present in the list of neglected tropical diseases (DIAS, 2011Dias JCP. Os primórdios do controle da doença de Chagas (em homenagem a Emmanuel Dias, pioneiro do controle, no centenário de seu nascimento). Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2011; 44(Suppl 2): 12-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822011000800003. PMid:21584352.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822011...

). Despite the main reservoirs of CD being wild species, cats and dogs are known to get infected by the causative protozoan; this plays an important role in the ecology and epidemiology of this disease (GÜRTLER et al., 2007Gürtler RE, Cecere MC, Lauricella MA, Cardinal MV, Kitron U, Cohen JE. Domestic dogs and cats as sources of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in rural northwestern Argentina. Parasitology 2007; 134(1): 69-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006001259. PMid:17032467.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006001...

). The natural infection of dogs byT. cruzi occurs in a manner similar to human infections, occurring either through active transmission by the vector, or through contamination of the skin and/or conjunctiva by infected feces. However, Barr (2006)Barr SC. American trypanosomiasis. In: Greene CE. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 3th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2006. p. 676-680. stated that the transmission frequently occurs through the ingestion of infected vectors or infected tissues from rodents or other wild animals found in around shelters/residences.

The phylogenetic proximity between the parasites, and the fact that both diseases are endemic to some regions of South America, necessitate the analysis of the two infections in parallel. These zoonoses must be monitored and controlled through surveys that combine serological and epidemiological approaches for each geographical location, as these strategies can lead to the allocation of specific funds that will allow policy-makers to organize and direct new policies towards strengthening public health as a whole.

The aforementioned reasons, the effect of CVL and CD on public health, the role of dogs as parasite reservoirs, and the scarce evidence-based data available in the State of Paraíba, have motivated this study, which aims to determine the seropositive and associated risk factors for Leishmania spp. andT. cruzi in the canine population of this region.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Committee

This work was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUA/CESED), Faculty of Medical Sciences of Campina Grande-FCM, under the code 0041/280314.

Samples

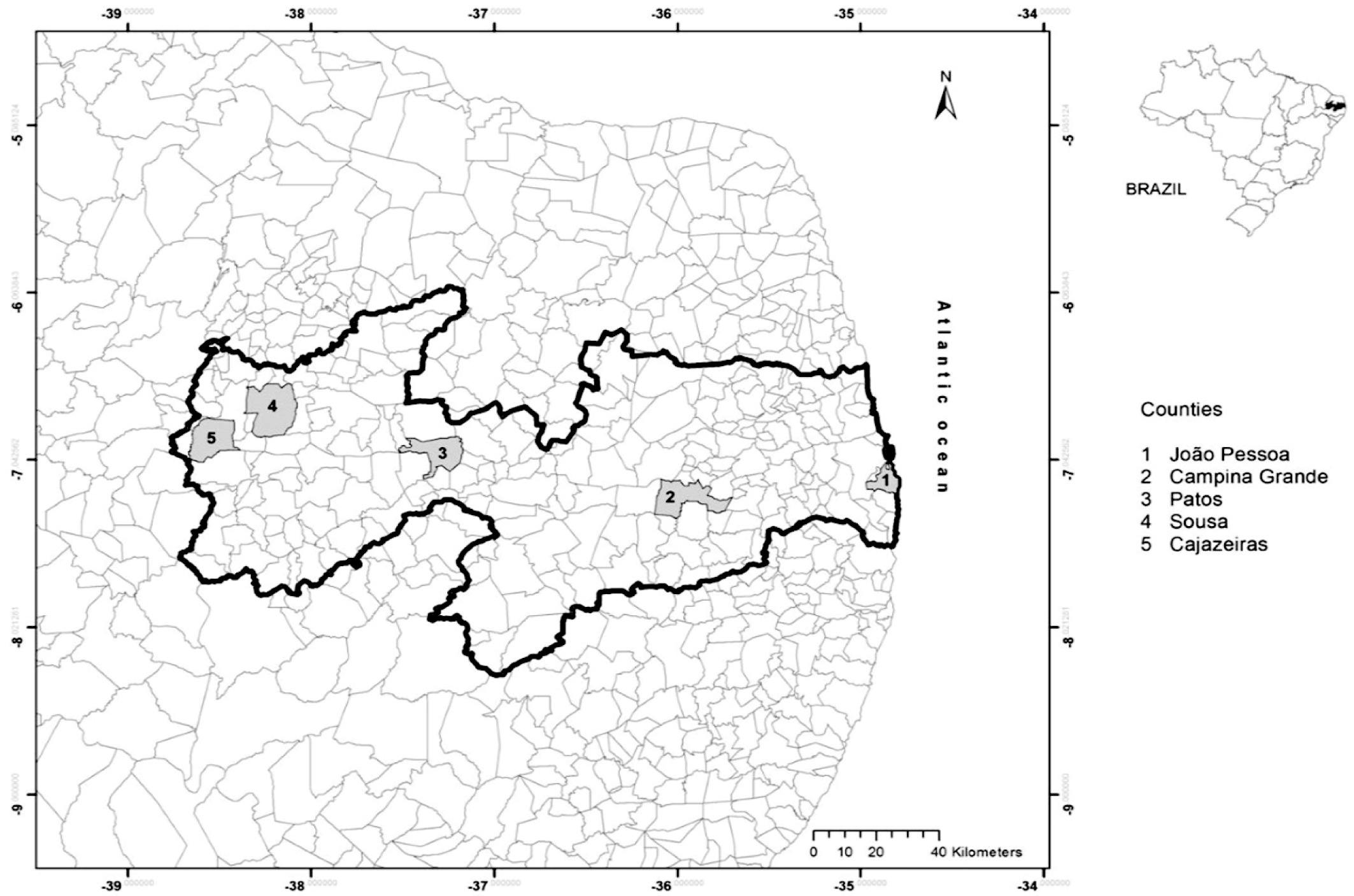

Dogs older than three months were included in this study; the test subjects were identified by visiting the residences of their owners, and from those admitted to veterinary clinics and analysis laboratories. Animals from the João Pessoa, Campina Grande, Patos, Sousa, and Cajazeiras counties (Figure 1), five regional urban centers in the State of Paraíba situated along one of the major highways (BR-230; also known as the Trans-Amazonian highway), were included in this study. The sample size was determined according to the total population of dogs (141,863 animals) in these counties (6,843 dogs in Sousa, 10,553 in Patos, 78,073 in João Pessoa, 6,103 in Cajazeiras, and 40,291 in Campina Grande). These numbers were estimated based on human population data for the year 2013, provided by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2013Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1º de julho de 2013 [online]. Brasília: IBGE; 2013 [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/nota_metodologica_2013.pdf

ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Pop...

). The dog/human distribution in urban areas was calculated at a ratio of 1:10 (WHO, 1990World Health Organization – WHO. Guidelines for dog population management. Geneva: WHO; 1990.; REICHMANN et al., 1999Reichmann MLAB, Pinto HBF, Nunes VP. Vacinação contra raiva de cães e gatos [online]. São Paulo; 1999 [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.saude.sp.gov.br/resources/instituto-pasteur/pdf/manuais/manual_03.pdf

http://www.saude.sp.gov.br/resources/ins...

). The sample size was determined for each county based on an estimated seropositivity of 50% (value adopted for sample maximization), a confidence level of 95%, and an error of 10% (THRUSFIELD, 2007Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2007.); this provided the required sample size of at least 96 animals per county. Ultimately, 1,043 animals were included in this study (125 dogs in Sousa, 206 in Patos, 338 in João Pessoa, 125 in Cajazeiras, and 249 in Campina Grande).

Geographical distribution of counties used. Detail shows the State of Paraíba within Brazil.

Probabilistic criteria were not established for animal selection, i.e., inclusion of the animals depended on previous contact with the owners and their agreement to taking part in the study. Blood samples were collected from the external jugular or cephalic veins using 5 mL disposable syringes, in the period from January 2013 to June 2014; the serum samples were stored at –20 °C until serological tests.

Serology

Serum antibodies for both diseases were searched by indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT), using the protocol by Camargo (1966)Camargo ME. Fluorescent antibody test for the sorodiagnosis of American trypanosomiasis: technical modification employing preserved culture forms of in a slide test. Trypanosome cruziRev Inst Med Trop 1966; 8(5): 227-235. PMid:4967348.; the samples were diluted as follows: 1:40, 1:80, 1:160, 1:320, and 1:640. The antigen used to coat the slides for CVL diagnosis was prepared from L. major-like promastigotes, whereas the antigen for CD was prepared from T. cruzi (strain Y) epimastigotes; both cultures were maintained in LIT (Liver Infusion Triptose) and NNN (Neal, Novy, Nicolle) culture media. Positive and negative control sera, for both parasites, were provided by the Núcleo de Pesquisa em Zoonoses (NUPEZO), Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP), Botucatu – SP. Based on the results obtained for the controls, the final antibody titer was determined to correspond to the highest dilution of the sera; under these conditions, the membranes of at least 50% of the promastigotes (CVL) and epimastigotes (CD) emitted readable fluorescence, with a cutoff of 40 or higher.

Animals that tested seropositive for both parasites (by IFAT) were further subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the ELISA S7® kit (Biogene Indústria & Comercio Ltda ME, Recife-PE, Brazil) for the sorological diagnosis of CVL. ELISA was performed as per the manufacturer protocols in order to minimize cross-reactivity and accurately detect possible co-infections.

Serum samples that showed positive results at the 1:40 or higher dilutions by IFAT, and which were also determined to be reactive by ELISA, were established to be positive for Leishmania spp. Dogs were determined to be positive for T. cruzi when results from the 1:40 or higher serum dilutions were detected by IFAT. Simultaneous serological reactions were diagnosed when the animal was seropositive for both parasites.

Epidemiological questionnaires

During the collection of blood samples from the dogs, their owners were also provided with an epidemiological questionnaire. This questionnaire requested information regarding a series of variables, in order to investigate certain behaviors and conditions that could act as risk factors for CVL and CD. The variables analyzed and respective categories were as follow:

-

-

Owner’s information: county of origin (Sousa, Patos, João Pessoa, Cajazeiras, Campina Grande), level of education (illiterate,1st degree, 2nd degree, 3th degree), and traveling with the dog (yes, no);

-

-

Animal’s information: gender (male, female), age (≤ 12 months, 13-48 months, 49-72 months, > 72 months), breed (undefined, defined), conditions of housing (domiciled environment [dogs without access to streets], semi-domiciled [dogs with restricted access to streets], free [dogs with unrestricted access to streets]), and dog food (commercial, homemade, homemade meals, a combination of commercial and homemade, a combination of commercial and homemade meals);

-

-

Environment’s information: contact with other dogs (yes, no), contact with bovine (yes, no), contact with horses (yes, no), contact with cats (yes, no), contact with goat/sheep (yes, no), contact with pigs (yes, no), contact with wild animals (yes, no), environmental conditions (soil, cement, soil and cement), environmental hygiene (yes, no), presence of rodents (yes, no), and access to water dams (yes, no).

Risk factor analysis

The risk factors were analyzed from the data obtained by the epidemiological questionnaires, using univariable approaches. Two groups of animals, seropositive and seronegative dogs, were formed for univariable analysis; these were compared with the tested variables. Variables with p ≤ 0.2, determined by the chi-square or Fisher's exact tests (ZAR, 1999Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1999.), were selected for multivariable analysis, using multiple logistic regression (HOSMER & LEMESHOW, 2000Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000.. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471722146.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471722146...

). The significance level considered to discarding a determined variable was 5%. The collinearity among independent variables was assessed using correlation analysis, and when two variables were highly collinear (correlation coefficient > 0.90), only one variable was likely to enter into analysis. In such situations, selection of which collinear variable to put into the model was guided by biological plausibility (DOHOO et al., 1997Dohoo IR, Ducrot C, Fourichon C, Donald A, Hurnik D. An overview of techniques for dealing with large numbers of independent variables in epidemiologic studies. Prev Vet Med 1997; 29(3): 221-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-5877(96)01074-4. PMid:9234406.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-5877(96)...

). The tests were performed using the SPSS software package, version 13.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Of the 1,043 dogs included in the study, 81 tested seropositive forLeishmania spp. (7.8%; 95%CI = 6.1-9.4%). The following antibody titers were detected: 38 (46.9%), 15 (18.5%), 11 (13.5%), 8 (9.8%), and 9 (11.1%) dogs had titers of 40, 80, 160, 320, and 640, respectively. Eighty-three (7.9%; 95% CI = 6.3-9.6%) dogs tested seropositive for T. cruzi; forty-five (54.2%) animals displayed antibodies at a serum titer of 40, while 12 (14.4%), 9 (10.8%), 10 (12%), and 7 (8.4%) displayed antibodies at titers of 80, 160, 320 and 640, respectively. Simultaneous serological reactions were detected in 49 (4.6%; 95% CI = 3.6-6.2%) dogs. Table 1shows the distribution of seropositive animals according to the county of origin.

Seropositivity for visceral leishmaniasis, Chagas disease and both diseases in dogs in the period from January 2013 to June 2014, in the State of Paraíba, Brazil.

Univariable analysis (Table 2) of the risk factors for CVL seropositivity (p ≤ 0.2) focused on the following variables: county of origin (p < 0.001), level of education of the owner (p = 0.055), breed (p < 0.001), conditions of housing (p < 0.001), dog food (p < 0.001), contact with other dogs (p < 0.001), contact with bovine (p < 0.001), contact with cats (p < 0.001), contact with goat/sheep (p < 0.001), contact with wild animals (p < 0.001), environmental conditions (p < 0.001), environmental hygiene (p = 0.001), traveling with the dog (p = 0.047), presence of rodents (p = 0.138), and access to water dams (p < 0.001). Semi-domiciled housing (OR = 2.044), free housing (OR = 4.151), and soil (OR = 3.425) and soil/cement (OR = 3.065) environmental conditions were identified as risk factors for CVL seropositivity in the logistic regression analysis (Table 3).

Univariable analysis for risk factors associated with the seropositivity for visceral leishmaniasis and Chagas disease in dogs in the period from January 2013 to June 2014, in the State of Paraíba, Brazil.

Risk factors associated with the seropositivity for visceral leishmaniasis and Chagas disease in dogs in the period from January 2013 to June 2014, in the State of Paraíba, Brazil.

Univariable analysis (Table 2) of the risk factors for CD seropositivity (p ≤ 0.2) focused on the following variables: county of origin (p < 0.001), level of education of the owner (p = 0.043), age (p=0.194), breed (p < 0.004), housing conditions (p < 0.001), dog food (p = 0.056), contact with other dogs (p = 0.002), contact with bovine (p < 0.001), contact with cats (p = 0.001), contact with goat/sheep (p < 0.001), contact with wild animals (p < 0.006), environmental conditions (p = 0.009), environmental hygiene (p = 0.025), and access to water dams (p < 0.001). Logistic regression identified the following risk factors (Table 3): semi-domiciled (OR = 2.353) or free housing (OR = 3.454), and contact with bovine (OR = 2.015).

Discussion

Several surveys have been conducted in Brazil with the aim of establishing the prevalence of CVL; these studies have produced variable results depending on the characteristics of the study population and the methods used. Alves et al. (1998)Alves AL, Bevilaqua CML, Moraes NB, Franco SO. Levantamento epidemiológico da leishmaniose visceral em cães vadios da cidade de Fortaleza, Ceará. Ciênc Anim 1998; 8(2): 63-68., Martins (2008)Martins IV. Aspectos epidemiológicos e de hemostasia na leishmaniose visceral canina. [Dissertation]. Recife: Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco; 2008., and Barboza et al. (2009)Barboza DCPM, Leal DC, Souza BMPS, Carneiro AJB, Gomes Neto CMB, Alcântara AC, et al. Inquérito epidemiológico da leishmaniose visceral canina em três distritos sanitários do Município de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. Rev Bras Saúde Prod Anim 2009; 10(2): 434-447., who conducted studies in Fortaleza, CE, Maceió, AL, and Salvador, BA, observed disease frequencies of 1.59%, 1.9%, and 0.7%, respectively; these disease frequencies were lower than the ones reported in this study. In contrast, similar disease frequency was reported by Azevedo et al. (2008)Azevedo MA, Dias AKK, Paula HB, Perri SHV, Nunes CM. Avaliação da leishmaniose visceral canina em Poxoréo, Estado do Mato Grosso, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2008; 17(3): 123-127. PMid:19245756. in a survey conducted in Poxoréo, MT (7.8%). The highest disease frequencies were identified by Matos et al. (2006)Matos MM, Filgueira KD, Amora SSA, Suassuna ACD, Ahid SMM, Alves ND. Ocorrência da Leishmaniose Visceral em cães em Mossoró, Rio Grande do Norte. Ciênc Anim 2006; 16(1): 51-54. in animals admitted to the UFERSA veterinary hospital, Mossoró, RN (28%); in addition, Amora et al. (2006)Amóra SSA, Santos MJP, Alves ND, Costa SCG, Calabrese KS, Monteiro AJ, et al. Fatores relacionados com a positividade de cães para leishmaniose visceral em área endêmica do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Cienc Rural 2006; 36(6): 1854-1859. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006000600029.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006...

, observed very high disease frequencies of 45% and 34% in rural and urban areas of Mossoró, RN, respectively, while Abreu-Silva et al. (2008)Abreu-Silva AL, Lima TB, Macedo AA, Moraes-Júnior FJ, Dias EL, Batista ZS, et al. Soroprevalência, aspectos clínicos e bioquímicos da infecção por Leishmania em cães naturalmente infectados e fauna de flebotomíneos em uma área endêmica na ilha de São Luís, Maranhão, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2008;17(Suppl 1): 197-203. PMid:20059848., Almeida et al. (2012)Almeida ABPF, Sousa VRF, Cruz FACS, Dahroug MAA, Figueiredo FB, Madeira MF. Canine visceral leishmaniasis: seroprevalence and risk factors in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2012; 21(4): 359-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612012005000005. PMid:23184322.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612012...

, and Morais et al. (2013)Morais AN, Sousa MG, Meireles LR, Kesper N Jr, Umezawa ES. Canine visceral leishmaniasis and Chagas disease among dogs in Araguaína, Tocantins. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2013; 22(2): 225-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612013005000024. PMid:23802237.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612013...

observed high disease frequencies in São Luiz, MA (51.6%), Cuiabá, MT (22.1%), and Araguaína, TO (51.35%), respectively. However, it should be emphasized that a majority of these studies were conducted in single locations, whereas the current study focused on five different urban hubs in the State of Paraíba, which could explain the differences in seropositivity. Rondon et al. (2008)Rondon FCM, Bevilaqua CML, Franke CR, Barros RS, Oliveira FR, Alcântara AC, et al. Cross-sectional serological study of canine infection in Fortaleza, Ceará state, Brazil. LeishmaniaVet Parasitol 2008; 155(1-2): 24-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.014. PMid:18565676.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008....

reported that the distribution of CVL frequency suggested a seasonal variation, which was caused by the high and low peaks of the vector population, which could justify the variability of data for CVL prevalence throughout Brazil.

Paraíba is an endemic region for CVL, and according to the SINAN Health Information System (Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação), 162 cases of human visceral leishmaniasis have been recorded between 2007 and 2013 (BRASIL, 2014Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Casos confirmados de Leishmaniose Visceral, Brasil, grandes regiões e unidades federadas 1990 a 2013 [online]. Brasília; 2014 [cited 2014 Mar 27]. Available from: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/o-ministerio/principal/leia-mais-o-ministerio/726-secretaria-svs/vigilancia-de-a-a-z/leishmaniose-visceral-lv/11334-situacao-epidemiologica-dados

http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.ph...

) in Paraíba. Therefore, the measures developed for the control of CVL and VL must be revisited by the responsible policy-makers to facilitate constant monitoring of the canine population for the presence of anti-L. chagasi antibodies, in order to prevent transmission to humans.

It should be highlighted that the criterion adopted for positive serological results in this study (IFAT associated with ELISA, instead of IFAT alone) may have influenced the results. Because of the controversy and the fact that many owners are reluctant to euthanize their animals, since the adoption of that measure has no sufficient effectiveness in reducing the prevalence of cases of the disease, there is the need to carry out more than one test for the confirmatory diagnosis of this disease as well as a standardization of diagnostic techniques to be used both in surveys and in individual cases. This question becomes even more delicate when many of the animals are asymptomatic.

The housing conditions of the dogs, particularly semi-domiciled and free environments, have previously been identified as risk factors for L. chagasi infection by Oliveira & Araújo (2003)Oliveira SS, Araújo TM. Avaliação das ações de controle da leishmaniose visceral (calazar) em uma área endêmica do estado da Bahia, Brasil (1995-2000). Cad Saude Publica 2003; 19(6): 1681-1690. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2003000600012. PMid:14999334.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2003...

, Amora et al. (2006)Amóra SSA, Santos MJP, Alves ND, Costa SCG, Calabrese KS, Monteiro AJ, et al. Fatores relacionados com a positividade de cães para leishmaniose visceral em área endêmica do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Cienc Rural 2006; 36(6): 1854-1859. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006000600029.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006...

, and Naveda et al. (2006)Naveda LAB, Moreira EC, Machado JG, Moraes JRC, Marcelino AP. Aspectos epidemiológicos da leishmaniose visceral canina no município de Pedro Leopoldo, Minas Gerais, 2003. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 2006; 58(6): 988-993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-09352006000600003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-09352006...

, in Feira de Santana, BA, Mossoró, RN, and Pedro Leopoldo, MG, respectively; these studies have strongly suggested the greater exposure of free animals to the vector. These results are also in agreement with the results obtained by Uchôa et al. (2001)Uchôa CMA, Serra CMB, Duarte R, Magalhães CM, Silva RM, Theophilo F, et al. Aspectos sorológicos e epidemiológicos da leishmaniose tegumentar americana canina em Maricá, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2001; 34(6): 563-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822001000600011. PMid:11813064.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822001...

, who reported that the lack of organized human occupation (proximity to hillsides and/or forest areas) caused an environmental imbalance that favored the occurrence of disease cycle outside the forests, and closer to the urban areas. The variables related to the environmental conditions (soil, soil/cement), also identified as risk factors for CVL, suggested that a strong presence of organic materials contributes to the proliferation of synanthropic species, in addition to creating a favorable habitat for the spread of the vector (as eggs are usually laid on organic materials).

For DC, 7.9% of the animals were seropositive for T. cruzi. This value differs from that (22.7%) described by Souza et al. (2009)Souza AI, Oliveira TMFS, Machado RZ, Camacho AA. Soroprevalência da infecção por em cães de uma área rural do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul. Trypanosoma cruziPesqui Vet Bras 2009; 29(2): 150-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000200011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009...

, which analyzed the seroprevalence of T. cruzi infection in dogs from Mato Grosso do Sul using IFAT and ELISA.Mendes et al. (2013)Mendes RS, Santana VL, Jansen AM, Xavier SCC, Vidal IF, Rotondano TEF, et al. Aspectos epidemiológicos da Doença de Chagas canina no semiárido paraibano. Pesq Vet Bras 2013; 33(12): 1459-1465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013001200011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013...

found a prevalence of 4.08% using IFAT, ELISA and indirect hemagglutination (IHA), in Patos, PB. The higher frequencies could probably be attributed to the predominantly rural survey areas, which are the usual ecotopes of disease vectors. Silva & Fernandes (2013)Silva PB, Fernandes JI. Aspectos clínicos epidemiológicos da infecção por Trypanosoma cruzi em cães naturalmente infectados no município de São Domingos Do Capim – Pará [online]. Pará: UFPA; 2013 [cited 2013 Sept 17]. Available from: http://www.pibic.ufpa.br/ANAISSEMINIC/XXIVSEMINIC/arquivos/resumos/Ciencias_Agrarias/ciencias_agrarias_014.pdf

http://www.pibic.ufpa.br/ANAISSEMINIC/XX...

utilized IFAT and ELISA and identified a prevalence for CD of 31% in domiciled dogs in São Domingos do Capim, PA. Silva et al. (2014)Silva MRM, Nascimento RCS, Negrão AMG, Valente VC, Valente SAS. Perfis sorológicos e hematológicos de cães em área de ocorrência de doença de chagas aguda no município de Bragança, estado do Pará [online]. Santa Catarina: Anclivepa; 2014 [cited 2014 May 04]. Available from: www.anclivepa2014.com.br/353/135.pdf

http://www.anclivepa2014.com.br/353/135....

used IFAT to detect a CD prevalence of 22.2% in a rural area of Bragança, PA. These values, which are higher than the ones reported in this study, could be attributed to the prior instances of human CD infections in both locations. Despite the low positivity reported in this study, the general population and the authorities must be alerted to the presence of infectious agents, in order to plan and establish epidemiological strategies for the effective control of CD.

The housing conditions of the dogs, particularly semi-domiciled and free environments, have also been identified as risk factors for T. cruzi. This is a reason for concern; despite the major vector for this disease (Triatoma infestans) being no longer responsible for CD infections in Brazil (ARGOLO et al., 2008Argolo AM, Felix M, Pacheco R, Costa J. Doença de Chagas e seus principais vetores no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Imperial Novo Milênio/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2008.), other species could contribute to its spread in the country.Triatoma sp. insects are currently migrating to urban areas, and have contributed to the strengthening of the disease cycle outside the forest (and closer to urban areas), thereby infecting dogs (especially the ones in free environments) and humans. Contact with bovine is another risk factor for CD. Many wild and domestic mammals are known reservoirs of CD; although dogs are the major domestic reservoir for human infection, other animals can also contribute to CD ecology (DIAS & COURA, 1997Dias JCP, Coura JR. Epidemiologia. In: Dias JCP, Coura JR. Clínica e terapêutica da Doença de Chagas: uma abordagem prática para o clínico geral. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 1997. p. 33-65.). Furthermore, it is usual the occurrence of bovine roaming free in many urban areas of the State of Paraíba. Dias et al. (2000)Dias JCP, Machado EMM, Fernandes AL, Vinhaes MC. Esboço geral e perspectivas da Doença de Chagas no Nordeste do Brasil. Cad Saude Publica 2000; 16(Suppl 2): 13-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2000000800003. PMid:11119317.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2000...

have reported the decades-old existence of peri-urban disease foci, and have suggested that the constant migration from rural to urban areas, and the poverty and semi-rural characteristics of the periphery neighborhoods determine disease distribution.

According to the criteria established in this study, 4.6% (49/1043) of the dogs tested positive (by IFAT assay) for Leishmania spp. and T. cruzi, possibly indicating the occurrence of mixed (simultaneous) infections (UMEZAWA & SILVEIRA, 1999Umezawa ES, Silveira JF. Serological diagnosis of Chagas disease with purified and defined Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1999;94(S1 Suppl Suppl 1): 285-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761999000700051. PMid:10677737.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761999...

). These results corroborate that ones obtained by Luciano et al. (2009)Luciano RM, Lucheis SB, Troncarelli MZ, Luciano DM, Langoni H. Avaliação da reatividade cruzada entre antígenos de spp e . LeishmaniaTrypanosoma cruzi na resposta sorológica de cães pela técnica de imunofluorescência indireta (RIFI)Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2009; 46(3): 181-187., who observed intense cross-reactions following higher differences in dog serum titers (tested by IFAT) forLeishmania spp. and T. cruzi antigens. It must be highlighted that the remaining T. cruzi titers varied between 40 and 640. In contrast, Souza et al. (2009)Souza AI, Oliveira TMFS, Machado RZ, Camacho AA. Soroprevalência da infecção por em cães de uma área rural do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul. Trypanosoma cruziPesqui Vet Bras 2009; 29(2): 150-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000200011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009...

mentioned the difficulties in discriminating between infections by T. cruzi and Leishmania spp. in asymptomatic dogs using conventional diagnostic techniques. Several South American locations are endemic to CVL and CD, with a high possibility of mixed infections. Morais et al. (2013)Morais AN, Sousa MG, Meireles LR, Kesper N Jr, Umezawa ES. Canine visceral leishmaniasis and Chagas disease among dogs in Araguaína, Tocantins. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2013; 22(2): 225-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612013005000024. PMid:23802237.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612013...

have also observed the simultaneous infection of canines by L. chagasi and T. cruzi in Araguaína, TO; of the 111 samples tested 57 were observed to be positive (IFAT and ELISA) for CVL (51.35%).The same sera were also analyzed by TESA-blot, which suggested the possibility of CD infection in five animals (4.5%); among these, 3 tested ELISA-positive and IFAT-negative for leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, seropositive animals for Leishmania spp. andT. cruzi were detected in the canine population in the State of Paraíba, suggesting the need for revisiting and intensification of disease control measures through constant monitoring by the competent authorities. Based on the identified risk factors for CVL and CD, we propose the observation of certain measures when allowing dogs on the streets; in addition, the environmental and housing conditions that the dogs are subjected must be improved. Contact with bovine was identified as risk factor for CD, which emphasizes the need for future studies on the role of this species in the transmission cycle of the disease.

References

- Abreu-Silva AL, Lima TB, Macedo AA, Moraes-Júnior FJ, Dias EL, Batista ZS, et al. Soroprevalência, aspectos clínicos e bioquímicos da infecção por Leishmania em cães naturalmente infectados e fauna de flebotomíneos em uma área endêmica na ilha de São Luís, Maranhão, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2008;17(Suppl 1): 197-203. PMid:20059848.

- Almeida ABPF, Sousa VRF, Cruz FACS, Dahroug MAA, Figueiredo FB, Madeira MF. Canine visceral leishmaniasis: seroprevalence and risk factors in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2012; 21(4): 359-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612012005000005. PMid:23184322.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612012005000005 - Alves AL, Bevilaqua CML, Moraes NB, Franco SO. Levantamento epidemiológico da leishmaniose visceral em cães vadios da cidade de Fortaleza, Ceará. Ciênc Anim 1998; 8(2): 63-68.

- Amóra SSA, Santos MJP, Alves ND, Costa SCG, Calabrese KS, Monteiro AJ, et al. Fatores relacionados com a positividade de cães para leishmaniose visceral em área endêmica do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Cienc Rural 2006; 36(6): 1854-1859. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006000600029.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006000600029 - Argolo AM, Felix M, Pacheco R, Costa J. Doença de Chagas e seus principais vetores no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Imperial Novo Milênio/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2008.

- Azevedo MA, Dias AKK, Paula HB, Perri SHV, Nunes CM. Avaliação da leishmaniose visceral canina em Poxoréo, Estado do Mato Grosso, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2008; 17(3): 123-127. PMid:19245756.

- Baneth G. Leishmaniases. In: Greene CE. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 3th ed. Saint Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. p. 685-698.

- Barboza DCPM, Leal DC, Souza BMPS, Carneiro AJB, Gomes Neto CMB, Alcântara AC, et al. Inquérito epidemiológico da leishmaniose visceral canina em três distritos sanitários do Município de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. Rev Bras Saúde Prod Anim 2009; 10(2): 434-447.

- Barr SC. American trypanosomiasis. In: Greene CE. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 3th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2006. p. 676-680.

- Borchhardt DM, Mascarello A, Chiaradia LD, Nunes RJ, Oliva G, Yunes RA, et al. Biochemical evaluation of a series of synthetic chalcone and hydrazide derivatives as novel inhibitors of cruzain from Trypanosoma cruzi.J Braz Chem Soc 2010; 21(1): 142-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532010000100021.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532010000100021 - Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Manual de vigilância e controle da Leishmaniose Visceral [online]. Brasília; 2006. Série A: Normas e manuais Técnicos [cited 2006 Oct 30]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_vigilancia_controle_leishmaniose_visceral.pdf

» http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_vigilancia_controle_leishmaniose_visceral.pdf - Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Casos confirmados de Leishmaniose Visceral, Brasil, grandes regiões e unidades federadas 1990 a 2013 [online]. Brasília; 2014 [cited 2014 Mar 27]. Available from: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/o-ministerio/principal/leia-mais-o-ministerio/726-secretaria-svs/vigilancia-de-a-a-z/leishmaniose-visceral-lv/11334-situacao-epidemiologica-dados

» http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/o-ministerio/principal/leia-mais-o-ministerio/726-secretaria-svs/vigilancia-de-a-a-z/leishmaniose-visceral-lv/11334-situacao-epidemiologica-dados - Camargo ME. Fluorescent antibody test for the sorodiagnosis of American trypanosomiasis: technical modification employing preserved culture forms of in a slide test. Trypanosome cruziRev Inst Med Trop 1966; 8(5): 227-235. PMid:4967348.

- Castro AG. Controle, diagnóstico e tratamento da leishmaniose visceral (calazar): normas técnicas. Brasília: Fundação Nacional de Saúde; 1996.

- Dias JCP, Coura JR. Epidemiologia. In: Dias JCP, Coura JR. Clínica e terapêutica da Doença de Chagas: uma abordagem prática para o clínico geral. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 1997. p. 33-65.

- Dias JCP, Machado EMM, Fernandes AL, Vinhaes MC. Esboço geral e perspectivas da Doença de Chagas no Nordeste do Brasil. Cad Saude Publica 2000; 16(Suppl 2): 13-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2000000800003. PMid:11119317.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2000000800003 - Dias JCP. Os primórdios do controle da doença de Chagas (em homenagem a Emmanuel Dias, pioneiro do controle, no centenário de seu nascimento). Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2011; 44(Suppl 2): 12-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822011000800003. PMid:21584352.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822011000800003 - Dohoo IR, Ducrot C, Fourichon C, Donald A, Hurnik D. An overview of techniques for dealing with large numbers of independent variables in epidemiologic studies. Prev Vet Med 1997; 29(3): 221-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-5877(96)01074-4. PMid:9234406.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-5877(96)01074-4 - Gürtler RE, Cecere MC, Lauricella MA, Cardinal MV, Kitron U, Cohen JE. Domestic dogs and cats as sources of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in rural northwestern Argentina. Parasitology 2007; 134(1): 69-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006001259. PMid:17032467.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006001259 - Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000.. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471722146.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471722146 - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1º de julho de 2013 [online]. Brasília: IBGE; 2013 [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/nota_metodologica_2013.pdf

» ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/nota_metodologica_2013.pdf - Kuhls K, Alam MZ, Cupolillo E, Ferreira GEM, Mauricio IL, Oddone R, et al. Comparative microsatellite typing of new world Leishmania infantum reveals low heterogeneity among populations and its recent old world origin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011; 5(6): e1155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001155. PMid:21666787.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001155 - Luciano RM, Lucheis SB, Troncarelli MZ, Luciano DM, Langoni H. Avaliação da reatividade cruzada entre antígenos de spp e . LeishmaniaTrypanosoma cruzi na resposta sorológica de cães pela técnica de imunofluorescência indireta (RIFI)Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2009; 46(3): 181-187.

- Martins IV. Aspectos epidemiológicos e de hemostasia na leishmaniose visceral canina. [Dissertation]. Recife: Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco; 2008.

- Matos MM, Filgueira KD, Amora SSA, Suassuna ACD, Ahid SMM, Alves ND. Ocorrência da Leishmaniose Visceral em cães em Mossoró, Rio Grande do Norte. Ciênc Anim 2006; 16(1): 51-54.

- Melo MN. Leishmaniose Visceral no Brasil: desafios e perspectivas. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2004; 13(S1): 41-45.

- Mendes RS, Santana VL, Jansen AM, Xavier SCC, Vidal IF, Rotondano TEF, et al. Aspectos epidemiológicos da Doença de Chagas canina no semiárido paraibano. Pesq Vet Bras 2013; 33(12): 1459-1465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013001200011.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013001200011 - Morais AN, Sousa MG, Meireles LR, Kesper N Jr, Umezawa ES. Canine visceral leishmaniasis and Chagas disease among dogs in Araguaína, Tocantins. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2013; 22(2): 225-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612013005000024. PMid:23802237.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612013005000024 - Naveda LAB, Moreira EC, Machado JG, Moraes JRC, Marcelino AP. Aspectos epidemiológicos da leishmaniose visceral canina no município de Pedro Leopoldo, Minas Gerais, 2003. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 2006; 58(6): 988-993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-09352006000600003.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-09352006000600003 - Oliveira SS, Araújo TM. Avaliação das ações de controle da leishmaniose visceral (calazar) em uma área endêmica do estado da Bahia, Brasil (1995-2000). Cad Saude Publica 2003; 19(6): 1681-1690. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2003000600012. PMid:14999334.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2003000600012 - Reichmann MLAB, Pinto HBF, Nunes VP. Vacinação contra raiva de cães e gatos [online]. São Paulo; 1999 [cited 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.saude.sp.gov.br/resources/instituto-pasteur/pdf/manuais/manual_03.pdf

» http://www.saude.sp.gov.br/resources/instituto-pasteur/pdf/manuais/manual_03.pdf - Rondon FCM, Bevilaqua CML, Franke CR, Barros RS, Oliveira FR, Alcântara AC, et al. Cross-sectional serological study of canine infection in Fortaleza, Ceará state, Brazil. LeishmaniaVet Parasitol 2008; 155(1-2): 24-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.014. PMid:18565676.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.014 - Santa Rosa ICA, Oliveira ICS. Leishmaniose Visceral: zoonose reemergente. Clin Vet 1997; 2(11): 24-28.

- Silva MRM, Nascimento RCS, Negrão AMG, Valente VC, Valente SAS. Perfis sorológicos e hematológicos de cães em área de ocorrência de doença de chagas aguda no município de Bragança, estado do Pará [online]. Santa Catarina: Anclivepa; 2014 [cited 2014 May 04]. Available from: www.anclivepa2014.com.br/353/135.pdf

» http://www.anclivepa2014.com.br/353/135.pdf - Silva PB, Fernandes JI. Aspectos clínicos epidemiológicos da infecção por Trypanosoma cruzi em cães naturalmente infectados no município de São Domingos Do Capim – Pará [online]. Pará: UFPA; 2013 [cited 2013 Sept 17]. Available from: http://www.pibic.ufpa.br/ANAISSEMINIC/XXIVSEMINIC/arquivos/resumos/Ciencias_Agrarias/ciencias_agrarias_014.pdf

» http://www.pibic.ufpa.br/ANAISSEMINIC/XXIVSEMINIC/arquivos/resumos/Ciencias_Agrarias/ciencias_agrarias_014.pdf - Simões-Mattos L, Mattos MRF, Teixeira MJ, Oliveira-Lima JW, Bevilaqua CML, Prata-Júnior RC, et al. The susceptibility of domestic cats (Felis catus) to experimental infection with Leishmania braziliensis.Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4): 199-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.10.008. PMid:15710520.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.10.008 - Souza AI, Oliveira TMFS, Machado RZ, Camacho AA. Soroprevalência da infecção por em cães de uma área rural do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul. Trypanosoma cruziPesqui Vet Bras 2009; 29(2): 150-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000200011.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000200011 - Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2007.

- Uchôa CMA, Serra CMB, Duarte R, Magalhães CM, Silva RM, Theophilo F, et al. Aspectos sorológicos e epidemiológicos da leishmaniose tegumentar americana canina em Maricá, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2001; 34(6): 563-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822001000600011. PMid:11813064.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822001000600011 - Umezawa ES, Silveira JF. Serological diagnosis of Chagas disease with purified and defined Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1999;94(S1 Suppl Suppl 1): 285-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761999000700051. PMid:10677737.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761999000700051 - World Health Organization – WHO. Guidelines for dog population management. Geneva: WHO; 1990.

- World Health Organization – WHO. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) [online], Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2015 Mar 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/

» http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/ - Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1999.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

11 Mar 2016 -

Date of issue

Jan-Mar 2016

History

-

Received

19 Jan 2016 -

Accepted

16 Feb 2016