ABSTRACT

Coral reefs are one of the most vulnerable ecosystems to ocean warming and acidification, and it is important to determine the role of reef building species in this environment in order to obtain insight into their susceptibility to expected impacts of global changes. Aspects of the life history of a coral population, such as reproduction, growth and size-frequency can contribute to the production of models that are used to estimate impacts and potential recovery of the population, acting as a powerful tool for the conservation and management of those ecosystems. Here, we present the first evidence of Siderastrea stellata planulation, its early growth, population size-frequency distribution and growth rate of adult colonies in Rocas Atoll. Our results, together with the environmental protection policies and the absence of anthropogenic pressures, suggest that S. stellata population may have a good potential in the maintenance and recovery in the atoll. However, our results also indicate an impact on corals' recruitment, probably as a consequence of the positive temperature anomaly that occurred in 2010. Thus, despite the pristine status of Rocas Atoll, the preservation of its coral community seems to be threatened by current global changes, such as more frequent thermal stress events.

Keywords:

Climate change; Coral reefs; Rocas Atoll; Siderastrea stellata; South Atlantic Ocean

INTRODUCTION

Increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in the atmosphere has been changing physical and chemical aspects of the planet, causing global warming, sea level rise, more frequent and intense storms, and ocean acidification (Sabine et al. 2004SABINE CL ET AL. 2004. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305: 367-371., Anthony et al. 2011ANTHONY KRN, KLEYPAS J and GATTUSO J-P. 2011. Coral reefs modify the carbon chemistry of their seawater - implications for the impacts of ocean acidification. Glob Change Biol 17: 3655-3666., Zeebe 2012ZEEBE RE. 2012. History of seawater carbonate chemistry, atmospheric CO2, and ocean acidification. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 40: 141-165.). Coral reefs are directly impacted by those changes; a rise in sea surface temperature causes severe bleaching (Hoegh-Guldberg 2011), ocean acidification suppresses growth and calcification (Albright et al. 2016ALBRIGHT R. ET AL. 2016. Reversal of ocean acidification enhances net coral reef calcification. Nature 531(7594): 362-365.) and sea level rise causes submergence of coral reefs and atoll islands (Kayanne 2016KAYANNE H. 2016. Response of Coral Reefs to Global Warming. In: Hayanne H (Ed), Coral Reef Science. Japan: Springer 5: 81-94.). Consequently, they are the one of the most threatened ecosystems (Kleypas et al. 1999aKLEYPAS JA, BUDDEMEIER RW, ARCHER D, GATTUSO JP, LANGDON C and OPDYKE BN. 1999a. Geochemical consequenses of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on coral reefs. Science 284: 118-120. , b, Kroeker et al. 2013KROEKER KJ, KORDAS RL, CRIM R, HENDRIKS IE, RAMAJO L, SINGH GS, DUARTE CM and GATTUSO J-P. 2013. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob Chang Biol 19: 1884-1896. ) and it is important to estimate their recovery potential from natural physiological disturbances and from anthropogenic perturbation. According to Edmunds (2007EDMUNDS PJ. 2007. Evidence for a decadal-scale decline in the growth rates of juvenile Scleractinian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 341: 1-13.) aspects of the life history of a coral population, such as reproduction, or growth and size- frequency are crucial to understand their role in the marine ecosystem and to obtain insight into their susceptibility to changes in the external physical and chemical environment. This information can be used in coral models and function as excellent tools to study demography, physiology/growth, and ecology, helping the conservation and management of this important ecosystem (Piniak et al. 2006).

In the South Atlantic Ocean there is only one atoll, Rocas Atoll, the first Brazilian marine protected area, created in 1979 and considered a pristine reef ecosystem (Longo et al. 2015LONGO GO ET AL. 2015. Between-Habitat Variation of Benthic Cover, Reef Fish Assemblage and Feeding Pressure on the Benthos at the Only Atoll in South Atlantic: Rocas Atoll, NE Brazil. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127176. ). Due to its isolation and conservational status, Rocas Atoll can act as an excellent opportunity to study the mechanism and impacts of global changes on reef systems. However, there is a gap of knowledge about corals population dynamics in this area. Its reef structure is constructed mainly by encrusting coralline red algae (70%) with the secondary framework builders composed by vermetid gastropods, encrusting foraminifera, polychaetes worm tubes, and corals (less than 10%) (Kikuchi and Leão 1997KIKUCHI RKP and LEÃO ZMAN. 1997. Rocas (Southwestern Equatorial Atlantic, Brazil): An Atoll Built Primarily By Coralline Algae. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa, p. 731-736., Gherardi and Bosence 2001GHERARDI DFM and BOSENCE D. 2001. Composition and community structure of the coralline algal reefs from Atol das Rocas, South Atlantic, Brazil. Coral Reefs 19: 205-219.). The dominant reef building coral species is Siderastrea stellata Verrill 1868 occurring in all tidal pools of the atoll (Echeverría et al. 1997ECHEVERRÍA CA, PIRES DO, MEDEIROS MS and CASTRO CB. 1997. Cnidarians of the Atol das Rocas, Brazil. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa 1: 443-446.). New information about its early growth, size frequency distribution and growth rate of adult colonies will contribute to model this population and predict effects of possible impacts such as ocean acidification or global warming.

S. stellata belongs to the genus Siderastrea de Blainville 1830 and to the family Siderastreidae Vaughan and Wells 1943. According to Wells (1956), this genus has existed since the Cretaceous and is represented by five extant species which has spread mainly in the Atlantic ocean, although two of them (Siderastrea savignyana and Siderastrea glynni) can be found in the Pacific and Indian Oceans (Budd and Guzman 1994BUDD AF and GUZMAN HM. 1994. Siderastrea glynni, A New Species of Scleractinian Coral (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) from the Eastern Pacific. Proc Biol Soc Washingt 107: 591-599.). S. stellata together with the species from the Caribbean Sea (Siderastrea siderea and Siderastrea radians) compose the "Atlantic Siderastrea complex" (Veron 1995VERON JEN. 1995. Corals in Space and Time: The Biogeography and Evolution of the Scleractinia, 321 p.). The taxonomy of this group has been debated and previously S. stellata was considered the only siderastreid in Brazil (Laborel 1974LABOREL J. 1974. West African reefs corals: An hypothesis on their origin. Proceedings of the 2nd International Coral Reef Symposium 1: 425-443., Maida and Ferreira 1997MAIDA M and FERREIRA BP. 1997. Coral reefs of Brazil, an overview. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa 1: 263-274.). Recently, the presence of S. radians and S. siderea was confirmed on the Brazilian coast (Neves et al. 2008NEVES EG ET AL. 2008. Genetic variation and population structuring in two brooding coral species (Siderastrea stellata and Siderastrea radians) from Brazil. Genetica 132(3): 243-254., 2010, Nunes et al. 2011NUNES FLD, NORRIS RD and KNOWLTON N. 2011. Long distance dispersal and connectivity in Amphi-Atlantic corals at regional and basin scales. PLoS ONE 6(7): e22298.) however, neither of those investigations included specimens collected at Rocas Atoll and up to now, only the occurrence of S. stellata is confirmed in this atoll.

S. stellata is a colonial, zooxanthellated and massive coral species with high resistance to environmental stress, such as sedimentation, wave action, temperature and salinity variations (Leão et al. 2003LEÃO ZMAN, KIKUCHI RKP and TESTA V. 2003. Corals and coral reefs of Brazil In: Cortez J (Ed), Latin American Coral Reefs, p. 9-52.). Until recently, it was accepted that its spatial distribution in the South Atlantic was from Parcel do Manuel Luiz, Maranhão (00°53'S, 044°16'W) to Cabo Frio, Rio de Janeiro - (23°S, 042°W, Lins-de-Barros and Pires 2007), but Cordeiro et al. (2015CORDEIRO RTS, NEVES BM, ROSA-FILHO JS and PÉREZ CD. 2015. Mesophotic coral ecosystems occur offshore and north of the Amazon River. Bull Mar Sci 91(4): 491-510.) shows that this species can also be found in reef communities adjacent to the Amazon River mouth in the coast of the Para state (00°21›14"S 46°53›56"W). According to Lins-de-Barros et al. (2003) S. stellata is a gonochoric brooder species, with a high female to male sex ratio and an annual reproductive cycle. Planulation occurs preferentially during the austral summer, concomitant with the seasonal sea surface temperature (SST) rise. S. stellata planula larvae were also observed in laboratory experiments to be released in January and April. The larvae contain zooxanthellae, with varied size from 500 µm to 1.4 mm in diameter and they start settlement between 72 hours to 15 days in close contact with parental polyps (Neves and Silveira 2003NEVES EG and SILVEIRA FL. 2003. Release of planula larvae, settlement and development of Siderastrea stellata Verrill, 1868 (Anthozoa, Scleractinia). Hydrobiologia 501: 139-147.).

Lins-de-Barros and Pires (2006a, b, 2007) studied some aspects of the life history of this species such as reproduction, growth and size frequency for other sites on the coast of Brazil. Nevertheless, at Rocas Atoll, despite the existence of information on S. stellata abundance (Echeverría et al. 1997ECHEVERRÍA CA, PIRES DO, MEDEIROS MS and CASTRO CB. 1997. Cnidarians of the Atol das Rocas, Brazil. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa 1: 443-446., Fonseca et al. 2012FONSECA AC, VILLACA R and KNOPPERS B. 2012. Reef Flat Community Structure of Atol das Rocas, Northeast Brazil and Southwest Atlantic. J Mar Biol 2012: 1-10. ), percent coverage (Longo et al. 2015LONGO GO ET AL. 2015. Between-Habitat Variation of Benthic Cover, Reef Fish Assemblage and Feeding Pressure on the Benthos at the Only Atoll in South Atlantic: Rocas Atoll, NE Brazil. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127176. ), and its importance as a natural archive for paleoclimate studies (Mayal et al. 2009MAYAL EM, SIAL AN, FERREIRA VP, FISNER M and PINHEIRO BR. 2009. Thermal stress assessment using carbon and oxygen isotopes from Scleractinia, Rocas Atoll, northeastern Brazil. Inter Geo Review 51: 166-188., Oliveira 2012OLIVEIRA RL. 2012. Esclerocronologia, geoquímica e registro climático em coral Siderastrea stellata do Atol das Rocas-RN, Brasil. Dissertação de mestrado. Programa de geoquímica, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niteroi, RJ, 105 p. (Unpublished)., Pereira et al. 2016PEREIRA NS, VOEGELIN AR, PAULUKAT C, SIAL NA, FERREIRA VP and FREI R. 2016. Chromium-isotope signatures in scleractinian corals from the Rocas Atoll, Tropical South Atlantic. Geobiology 14(1): 54-67. ), there is no record of other aspects of its population dynamics. Part of the reason of the absence of population models for Brazilian coral species are due to this lack of information to produce them. In this study we present the first evidence of S. stellata planulation, its early growth, size frequency distribution and growth rate of adult colonies. In addition, we discuss the implications of our results under a scenario of predicted impacts due to warming and acidification for the conservation of S. stellata population at Rocas Atoll.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY SITE

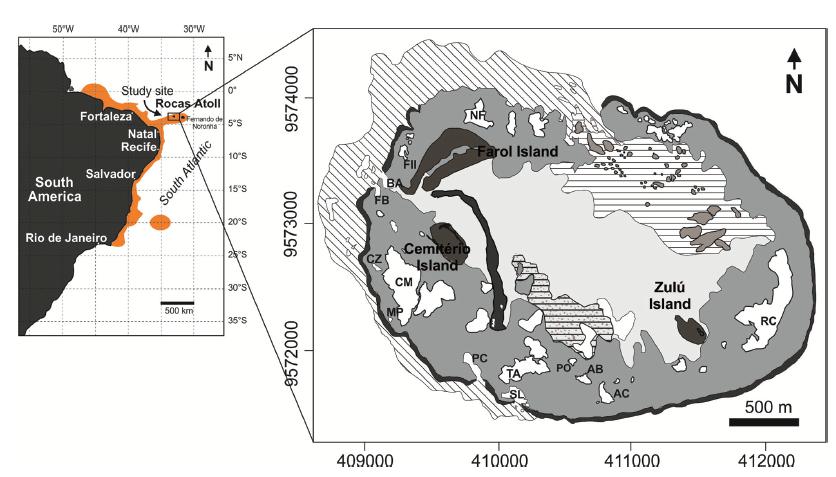

The Rocas Atoll is situated 266 km northeast of the coastal city of Natal, northeastern Brazil (Fig. 1). It is one of the smallest atolls in the world, with an axis of 3.35 km by 2.49 km, a reef area of 6.56 km2 and a perimeter of 11 km (Pereira et al. 2010PEREIRA NS, MANSO VAV, SILVA AMC and SILVA MB. 2010. Mapeamento Geomorfologico e Morfodinâmica do Atol das Rocas, Atlantico Sul. Rev Gest Cost Integ 10(3): 331-345.) and is the only atoll located in the western part of the South Atlantic (3°51´S, 33°49´W).

Location of the Rocas Atoll and the geographical distribution of the species S. stellata in the South America (orange area). The geomorphological map of the Rocas Atoll shows the intertidal reef- flat pools where colonies of S. stellata were collected and investigated - Abrolhos (AB), Âncoras (AC), Cemitério (CM), Cemitériozinho (CZ), Falsa Barreta (FB), Mapas (MP), Porites (PO), Podes Crer (PC), Tartarugas (TA) and Salão (SL).

Rocas is dominated by the South Equatorial Current (SEC), with consistent westerly flow (Goes 2005GOES CA. 2005. Correntes superficiais no Atlântico Tropical, obtidas por dados orbitais, e sua influência na dispersão de larvas de lagosta. Dissertação de Mestrado em Sensoriamento Remoto. São José dos Campos, São Paulo (INPE-1111-TDI/ 111). Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais - INPE, 35 p. (Unpublished).) and a mean velocity of 30 cm per second on the 4°S parallel (Richardson and Walsh 1986RICHARDSON PL and WALSH D. 1986. Mapping climatological seasonal variations of surface currents in the tropical Atlantic using ship drifts. J Geophys Res 91(C9): 10537-10550. ). The tidal regime is semi-diurnal and meso-tidal (Gherardi and Bosence 2001GHERARDI DFM and BOSENCE D. 2001. Composition and community structure of the coralline algal reefs from Atol das Rocas, South Atlantic, Brazil. Coral Reefs 19: 205-219.). No tidal range records exist in Rocas Atoll. In Fernando de Noronha's harbor (144 km east from Rocas) the maximum tidal range is 2.8 m (DHN 2014). The equatorial location of the Rocas Atoll leads to minimal seasonal SST variability, with an annual range of 3°C for monthly mean temperatures (Ferreira et al. 2012FERREIRA BP, COSTA MBSF, COXEY MS, GASPAR ALB, VELEDA D and ARAUJO M. 2012. The effects of sea surface temperature anomalies on oceanic coral reef systems in the southwestern tropical Atlantic. Coral Reefs 32: 441-454. ). Salinity in the surrounding seawaters varies from 36 to 37 parts per thousand (ppt) (Gherardi and Bosence 1999). There is a wet season from approximately March through July and a dry season from approximately August through February (APAC 2014).

DETERMINATION OF EARLY GROWTH OF S. stellata PRIMARY POLYPS

Five colonies of S. stellata (diameters between 10 and 20 cm) were collected during the last week of December 2012 at Cemitério pool and kept in 30 L seawater tanks with circulation and air pumps, covered with preconditioned ceramic tiles. The tanks were kept at the scientific base at Rocas Atoll in a shade dock that allows natural luminosity, but protects from direct solar incidence. Seawater in the tanks was renewed daily and temperature and salinity subsequently determined. During this process, the presence of planula larvae in the water column and the settlement of the primary polyps on the tiles was checked. From January until March 2013 the growth of the recruit was evaluated. The ceramic tiles were analyzed using a stereomicroscope and photographed. The size of the recruits was determined by measuring the maximum diameter at the base of the living tissue and the total area of the primary polyp using the Image J software. Polyp mortality was identified by the absence of living tissue on the skeleton, or when recruits were covered by epibenthic algae. At the end of the expedition in March 2013, the ceramic tiles and coral colonies were fixed back on the pool.

GROWTH RATE OF ADULT COLONIES

The growth rate pattern for S. stellata was analyzed in seven colonies of this species collected during June of 2012 from the following tidal pools: Abrolhos (1), Cemitério (1), Cemitériozinho (1), Falsa Barreta (1), Mapas (1), and Tartarugas (2). Colonies were cut into halves, and one half was cut into 5-mm thick slices parallel to the vertical growth axis of the whole colony. After cutting, these slices were air-dried and X-ray images were taken and digitalized for analysis of the extension rate by using the CoralXDS 3.0 Software (Helmle et al. 2002HELMLE KP, KOHLER KE and DODGE RE. 2002. Relative Optical Densitometry and The Coral X-radiograph Densitometry System: CoralXDS, In: Int. Soc. Reef Studies 2002 European Meeting. Cambridge.). Afterwards, several transects were analyzed in the digital image of the coral X-radiography in order to totally cover the lateral extension of the coral slab (Fig. 2).

a) Radiography of a 5 mm-slabs of one S. stellata colony collected at the Rocas atoll showing the transect locations along the growth axis and through the lateral extension of the colony slab where CoralXDS analysis were carried out; (b) image of the 5 mm-slab of the same colony.

S. stellata POPULATION SIZE STRUCTURE

During January and May 2014, the S. Stellata population data were collected by scuba divers along eight belt transects in each tidal pool. All S. stellata colonies within a 1 m belt transect, along 20-m transect, were counted and their size were categorized in four different classes according their maximum diameter size: < 2 cm, 2.1 - 4.0 cm, 4.1 - 10 cm and above 10 cm. Colonies in the transect edge were only considered in the count if they were more than 50% inside the delimited belt transect area.

RESULTS

EARLY GROWTH OF S. stellata PRIMARY POLYPS

During the period of the experiment (late December 2012 to early March 2013), the mean (± standard deviation) temperature and salinity in the tanks with the colonies and ceramic tiles were 29.01±2.03°C and 35.24±0.8 ppt, respectively. Five to seven days after the sampling period of the colonies, planula larvae was observed searching for suitable places in the ceramic tiles to settle (Fig. 3b, c). In total, 34 S. stellata recruits were observed. Five of them died during the study, corresponding to a mortality rate of 14.70%. Fusion of three primary polyps was observed (Fig. 3f), therefore those records were not used in the calculation of the growth rate due to the difficulty in identifying the base of the recruits. In addition, six other recruits were excluded from the evaluation due to the fact that their tentacles were always extended and the base of the polyps was partially covered by algae. From the 34 recruits observed, only 20 had their growth evaluated during the entire experimental period (Fig. 4). In January (about 17 days old), the mean diameter of the recruits (± SD) was 1.15±0.33 mm, ranging from 0.56 to 1.90 mm. In February (about one month), the recruits had a mean diameter of 1.25± 0.36, ranging from 0.71 to 2.12 mm. In March (aging around 45 to 50 days old), the recruits had mean values of diameters of 1.49±0.45 mm, ranging from 0.9 to 2.28 mm (Fig. 4a).

Parental colonies (a), planula larvae (b, c) and recruits nearly 50 days old (d, e, f) of S. stellata from Rocas Atoll.

Size of the S. stellata recruits according to a- diameter and b- area, measured between January and March 2013 at Rocas Atoll.

The mean area of the recruits (± SD) was 1.32±0.73 mm² in January, ranging from 0.32 to 3.28 mm². In February, the recruits presented a mean area of 1.61±0.94 mm², ranging from 0.51 to 4.38 mm². Average area of the recruits measured in March was 2.23±1.26 mm² ranging from 0.78 to 4.7 mm² (Fig. 4b).

GROWTH RATE OF ADULT COLONIES

Table I presents the annual extension rate of the seven colonies of S. stellata studied, obtained from the analysis of their radiographies using CoralXDS. Mean coral extension rates varied from 6.0 to 8.1 mm year-1 with an average of 6.8±0.7 mm year-1 (±SD, n=35).

Extension rate results for the seven analyzed colonies of S. stellata colleted at the Rocas atoll. Extension rates are expressed by millimeter per year (mm/year).

POPULATION SIZE STRUCTURE

The pools connected to the open ocean, Salão and Podes Crer, presented the highest S. stellata abundance, with 4.995 and 4.705 colonies m-2, followed by Ancoras and Tartarugas with 2.495 and 1.44 colonies m-2, respectively. The lowest abundance was recorded at Porites and Cemitério, with 0.645 and 0.465 colonies m-2, respectively (Fig. 5a). The frequency of the smallest size classes (recruits: diameters up to 2 cm and young colonies: 2.1 to 4 cm) were the lowest, representing less than 20% in all pools. Podes Crer was the pool were we observed more recruits: 26 in an eight belt transect (20 m² each) survey. The most frequent size class consisted of diameters between 4.01 and 10 cm. This was the dominant size frequency at Porites and Ancoras with 67.4 and 62.3%, respectively, at Cemitério and Podes Crer the size class 4.01-10cm was as frequent as the largest size class (>10cm). Half of the colonies observed at Tartarugas had a diameter higher than 10 cm. This class size was the dominant one at the Salão pool, with 68.9% of the colonies belonging to this size class (> 10 cm) (Fig. 5b).

S. stellata colony size- frequency distribution (a) and abundance (m2) (b) at the tidal pools of Rocas Atoll.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here begin to fill a gap in the knowledge about the dynamics of the dominant coral species at Rocas Atoll, and will contribute to the construction of models that would provide assistance for conservation and management of this population, and insight into their vulnerability to global change impacts. This study showed for the first time a Siderastrea stellata reproduction event at Rocas Atoll, with planula larvae being observed during the first week of January. According to Lins-de-Barros et al. (2003), it was observed latitudinal differences in the S. stellata period of planulation, e.g. December- early January in Buzios, and February to mid-March in Abrolhos-BA, and this difference was attributed to a punctual upwelling phenomenon that occurs in Buzios-RJ, which lowers the SST by many degrees. Planulation as consequence of the stress and handling during collection was detected by Neves and Silveira (2003NEVES EG and SILVEIRA FL. 2003. Release of planula larvae, settlement and development of Siderastrea stellata Verrill, 1868 (Anthozoa, Scleractinia). Hydrobiologia 501: 139-147.), where they inferred immaturity due to a high mortality rate of extruded larvae within 24-48 h of a free-swimming existence.

Our colonies were handled carefully and kept in tanks, within less than 1 km of distance from the sampling pool, with natural light and daily water change. During our experiment, larval swimming behavior or mortality was not observed. Out of all the recruits obtained in the experiment, only 14.70% died by the end of the third month. In the Lins-de-Barros and Pires (2007) study on the reproduction of S. stellata in Fernando de Noronha, they observed in colonies collected in late January that even though the planulation season had already started, oocytes were present in all of the examined polyps. They also observed that there was high polyp fecundity versus low number of larvae (37%), which suggested that most of the oocytes produced had not been fertilized. Therefore, although we have had observed larvae release, metamorphose and settlement of the S. stellata at Rocas Atoll, further studies are necessary to clarify the reproductive peak period of this species and fertilization rate of its population.

Juvenile life stages play critical roles in the population dynamics of virtually all organisms, and therefore precise estimates of juvenile growth and survival are important for accurate demographic analyses (Edmunds 2007EDMUNDS PJ. 2007. Evidence for a decadal-scale decline in the growth rates of juvenile Scleractinian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 341: 1-13.). In our study the mean diameter of the recruits as measured in March (aging around 45 to 50 days old) was 1.49±0.45 mm, ranging from 0.9 to 2.28 mm. According to Pinheiro (2006PINHEIRO BR. 2006. Recrutamento de corais no recife da Ilha da Barra Tamandaré -PE Dissertação de Mestrado. PPGO. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Recife, PE, 69 p. (Unpublished).), which monitored the growth of S. stellata recruits at the no take zone from the Coral's Coast Marine Protected Area (Tamandaré, PE) during one year, recruits with about the same age (50 days old) had an average diameter of 2.11±0.69 mm (n= 16), and by the end of the monitoring year they measured 7.19±4.5 mm, with a maximum observed diameter of 12.7 mm. Those recruits were kept on the natural reef, providing more stability and nutrients for the corals to grow. Although caution was taken to maintain good conditions in the tanks (water flow, oxygenation, and daily seawater change), it is likely that our results could reflect this experimental condition. Castro (2008CASTRO BRT. 2008. Identificação de Recrutas Vivos, Taxas de Crescimento e Sobrevivência de Corais Recifais Brasileiros (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). Dissertação de mestrado. Museu Nacional. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 137 p. (Unpublished).) observed S. stellata recruits with 1.5 years and diameters of 2.9 and 3.35 mm and juvenile corals with 7.29 mm (2.16 years) and 6.41mm (2.66 years) in a study in the south of Bahia state (Eastern Brazil), but it is not clear if those results represent recruits kept in an aquarium setup or on a natural reef. Either way, those diameter sizes and growth are very small compared to a rough estimation done with linear regression of the results observed during the three months of this study, which indicate a diameter range of 4.46 to 7.78 mm for one-year age recruits.

Some variations in growth rates of coral recruit have been attributed to different intensities of competition caused by the growth of algae and other organisms (Harrison and Wallace 1990HARRISON PL and WALLACE CC. 1990. Reproduction, dispersal and recruitment of Scleractinian corals. In: Dubinsky Z (Ed), Ecosystems of the world, vol 25, Coral reefs. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p. 133-207., Vermeij 2006VERMEIJ MJA. 2006. Early life-history dynamics of Caribbean coral species on artificial substratum: the importance of competition, growth and variation in life-history strategy. Coral Reefs 25: 59-71.), differences at the family taxonomic level, related to the spawning modes (Babcock 1985BABCOCK R. 1985. Growth and mortality in juvenile corals (Goniastrea, Platygyra and Acropora): The first year. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 5, Tahiti. Proceeding of the 5th International Coral Reef Symposium, Tahiti 4: 355-360.), and changes in the microhabitats conditions such as luminosity differences (Anthony and Hoegh-Guldberg 2003ANTHONY KRN and HOEGH-GULBERG O. 2003. Variation in coral photosynthesis, respiration and growth characteristics in contrasting light microhabitats: An analogue to plants in forest gaps and understories? Funct Ecol 17: 246-259.). Even though it is common to observe variations in the growth rates, it is important to have precise estimates. Discrepancies have important implications, because it suggests that the recruitment dynamics of coral populations may function over time scales longer than those usually considered (Edmunds 2007EDMUNDS PJ. 2007. Evidence for a decadal-scale decline in the growth rates of juvenile Scleractinian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 341: 1-13.). This study is the first to show the initial growth of S. stellata recruits in Rocas Atoll, although longer studies are needed to draw conclusions about the earlier growth rates of this species.

Concerning the annual extension rate for adult colonies, a growth rate of 6.8±0.7 mm.yr-1 (min. 5.1 and max.11.7 mm.y-1) was observed. This is in accordance with the study by Oliveira (2012OLIVEIRA RL. 2012. Esclerocronologia, geoquímica e registro climático em coral Siderastrea stellata do Atol das Rocas-RN, Brasil. Dissertação de mestrado. Programa de geoquímica, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niteroi, RJ, 105 p. (Unpublished).) who applyied a combined technic of radiometric U/Th dating and density banding counting to find a growth rate of 6.01±1.08 mm.yr-1, ranging from 3.76 to 8.53 mm.yr-1 for S. stellata from Rocas Atoll.

In reefs off the coast of Bahia state, linear extension rates of 2.73±035 mm yr-1 were found by Lins-de-Barros and Pires (2006b), which measured in colonies stained with alizarin red S, following the method of Lambert (1978LAMBERT AE. 1978. Coral growth: alizarin method. In: Coral Reefs: Research Methods, Stodart DR and Johanne RE (Eds), p. 523-527.). Additionally, Reis and Leão (2000REIS MAC and LEÃO ZMAN. 2000. Bioerosion rate of the sponge Cliona celata (Grant 1826) from reefs in turbid waters, north Bahia, Brazil. In: International Coral Reef Symposium, 9. Bali, Indonesia. Proceedings. Indonesia, Indonesian Institute of Sciences 2: 273-278.) reported a linear growth rate of 2.38±0.20 mm yr-1 by counting the density banding revealed in X-radiographies. Although the methodology used by Lins-de-Barros and Pires (2006b) could cause handling stress during coral staining, and thus lead to a lower growth rate, the results presented by Reis and Leão (2000) pointed to the same value, indicating that the observed growth rate might be site dependent.

Differences in the mean annual linear extension were also observed for Siderastrea siderea, in Panama. There, Guzman and Tudhope (1998GUZMAN HM and TUDHOPE AW. 1998. Seasonal variation in skeletal extension rate and stable isotopic (13C/ 12C and 18O/ 16O) composition in response to several environmental variables in the Caribbean reef coral Siderastrea sidereal: Mar Ecol Prog Series 166: 109-118.) observed a 7.6±0.7 mm mean annual linear extension during the period from April 1991 to March 1992. In a previous study, Guzman and Cortes (1989), reported a decadal mean annual linear extension of 5.2 mm (ranging from 2 to 6.3 mm; 1976 to 1986), about 2.4 mm lower than the rate recorded in the 90's. Variations of the annual extension rate were also observed for S. siderea in the Caribbean Sea, from 3.5 to 4.3 mm. yr-1 in Puerto Rico (Torres and Morelock 2002TORRES JL and MORELOCK J. 2002. Effect of terrigenous sediment influx on coral cover and linear extension rates of three Caribbean massive coral species: Caribbean Journal of Science 38(3-4): 222-229.).

The lower linear growth rates observed for S. stellata at the reefs from Bahia coast compared to Rocas Atoll (this study and Oliveira 2012OLIVEIRA RL. 2012. Esclerocronologia, geoquímica e registro climático em coral Siderastrea stellata do Atol das Rocas-RN, Brasil. Dissertação de mestrado. Programa de geoquímica, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niteroi, RJ, 105 p. (Unpublished).), may be due to the differences in the environmental conditions from the two localities. Although, there is an agreement in the scientific community that coral extension rates are species specific (Muslic et al. 2013MUSLIC A, FLANNERY JA, REICH CD, UMBERGER DK, SMOAK JM and POORE RZ. 2013. Linear extension rates of massive corals from the Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO), Florida: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2013-1121, 22 p. (http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1121/),

http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1121/...

), studies measuring linear extension rates within individual species indicated that a variety of factors such as season, rainfall, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, light levels and location within the reef, correlate with (and may influence) coral linear extension rates (Anthony and Hoegh-Guldberg 2003ANTHONY KRN and HOEGH-GULBERG O. 2003. Variation in coral photosynthesis, respiration and growth characteristics in contrasting light microhabitats: An analogue to plants in forest gaps and understories? Funct Ecol 17: 246-259., De'ath et al. 2009DE'ATH G ET AL. 2009. Declining coral calcification on the Great Barrier Reef: Science 323(5910): 116-119.). There are important differences between Rocas Atoll and reefs from the south of Bahia, especially regarding aspects such as sedimentation rates. Rocas is an oceanic island, isolated from the influence of river discharges and it is probably the most effective marine reserve and the closest to a pristine reef in the Tropical Southwestern Atlantic (Longo et al. 2015LONGO GO ET AL. 2015. Between-Habitat Variation of Benthic Cover, Reef Fish Assemblage and Feeding Pressure on the Benthos at the Only Atoll in South Atlantic: Rocas Atoll, NE Brazil. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127176. ). Reefs from the Coast of Bahia are experiencing increasing degradation due to a combination of large-scale natural threats (e.g. sea level oscillations and ENSO events). Local scale anthropogenic stressors, such as accelerated coastal development, reef eutrophication, marine pollution, tourism pressure, over-exploitation of reef resources, overfishing and destructive fisheries and, more recently, the introduction of non-indigenous invasive species are also related to this degradation (Leão and Kikuchi 2011LEÃO ZMAN and KIKUCHI RKP. 2011. Brazil: Coral Reefs In: David H (Ed), Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs, p. 168-172.). There is a record of the impact of ENSO events in the coral community at the atoll (Ferreira et al. 2012FERREIRA BP, COSTA MBSF, COXEY MS, GASPAR ALB, VELEDA D and ARAUJO M. 2012. The effects of sea surface temperature anomalies on oceanic coral reef systems in the southwestern tropical Atlantic. Coral Reefs 32: 441-454. ) but overall, the differences in the linear extension rates for S. stellata we observed in this study may reflect the higher environmental quality of the reef system in Rocas compared to those from Bahia.

Size-frequency distributions have been used to assess the ecological status of different populations in a variety of ecosystems. In coral reef systems, size reflects many life-history processes such as maturation, fecundity, survival and the response of corals to time-varying influences of the environment, including the intensity and frequency of disturbances and the degree of environmental degradation (Zvuloni et al. 2008ZVULONI A, ARTZY-RANDRUP Y, STONE L, VAN WOESIK R and LOYA Y. 2008. Ecological size frequency distributions: how to prevent and correct biases in spatial sampling. Limnol Oceanogr 6: 144-153.).

As a dominant coral species at Rocas, the abundance of S. stellata we found in this study (Fig. 5) is in accordance with the hard coral coverage evaluated by Ferreira et al. (2012FERREIRA BP, COSTA MBSF, COXEY MS, GASPAR ALB, VELEDA D and ARAUJO M. 2012. The effects of sea surface temperature anomalies on oceanic coral reef systems in the southwestern tropical Atlantic. Coral Reefs 32: 441-454. ). They reported a higher percentage in the open pools compared to the isolated ones: 50.6±6.0% at Salão; 34.0 ±14.2% at Podes Crer; followed by 22.5±7.8% in Tartarugas and the lowest coverage, 5.6 ±6.1% at Cemitério. Besides great abundance, the open pools have a high frequency of larger colonies. In the Salão pool, for instance, 68.87% of the colonies have diameters greater than 10 cm. Coral colony size might be considered important for maturation and fecundity. According to Lins-de-Barros and Pires (2006a), the number of oocytes produced per polyp in S. stellata populations is highly variable, although it was always greater in larger colonies, averaging eight oocytes per polyp, and nonetheless colonies larger than 5 cm in diameter had at least one oocyte. Thereby, the size frequency distribution of S. stellata population at Rocas Atoll presented here can be considered to be representative of a mature community, with overall high frequency of colonies with diameters higher than 10 cm (41.2±18.5%).

Another factor that may contribute to the potential of maintenance and recovery of S. stellata population in the atoll is the tidal dynamics that results in strong currents when the atoll is either filling or draining and during high tides (Longo et al. 2015LONGO GO ET AL. 2015. Between-Habitat Variation of Benthic Cover, Reef Fish Assemblage and Feeding Pressure on the Benthos at the Only Atoll in South Atlantic: Rocas Atoll, NE Brazil. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127176. ). S. stellata larvae started to settle between 72 hours and 15 days in close contact with parental polyps (Neves and Silveira 2003NEVES EG and SILVEIRA FL. 2003. Release of planula larvae, settlement and development of Siderastrea stellata Verrill, 1868 (Anthozoa, Scleractinia). Hydrobiologia 501: 139-147.), and even though it is still necessary to elucidate dispersion and larval recruitment in the atoll, it is likely that the larvae produced by the colonies in the open pools can be dispersed around the atoll. This would explain the higher frequency of juvenile colonies in the closed pools, where we observed frequencies of 67.4% at Porites and 62.3% at Âncoras in colonies with 4.1 to 10 cm diameters. Ferreira et al. (2012FERREIRA BP, COSTA MBSF, COXEY MS, GASPAR ALB, VELEDA D and ARAUJO M. 2012. The effects of sea surface temperature anomalies on oceanic coral reef systems in the southwestern tropical Atlantic. Coral Reefs 32: 441-454. ) indicate that the occurrence of two sequential positive SST anomalies (2009 and 2010), which triggered up to 50% coral bleaching in the Rocas Atoll and Fernando de Noronha reefs, reduced post-bleaching coral recovery and intensified the outbreak of diseases, specifically black-band, plague and dark-spot diseases affecting primarily Siderastrea spp. at the atoll. Thus, the low frequency of young colonies with diameters up to 2 cm (1.8±1.12%) and from 2.1 to 4 cm (8.9±3.87%) that we found in our study may be a consequence of a reduced recruitment event.

Several authors have investigated negative effects of increasing SST on coral reefs. Edmunds (2007EDMUNDS PJ. 2007. Evidence for a decadal-scale decline in the growth rates of juvenile Scleractinian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 341: 1-13.) highlights a gradual decline in the growth rates of juvenile corals in St. John, US Virgin Islands and links this decline with rising seawater temperature and depressed aragonite saturation state. The author further suggests that the effects of global climate change may have already reduced the growth of juvenile corals. De'ath et al. (2009DE'ATH G ET AL. 2009. Declining coral calcification on the Great Barrier Reef: Science 323(5910): 116-119.) show that linear extension rates in corals decrease as a result of SST increase. Anlauf et al. (2011ANLAUF H, D'CROZ L and O'DEA A. 2011. A corrosive concoction: The combined effects of ocean warming and acidification on the early growth of a stony coral are multiplicative. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 397: 13-20.) points out that in future scenarios of increased temperature and oceanic acidification, coral planulae will be able to disperse and settle successfully, but primary polyp growth may be hampered. According to Albright (2011ALBRIGHT R. 2011. Reviewing the effects of ocean acidification on sexual reproduction and early life history stages of reef-building corals. J Mar Biol 2011: 14.), available information indicates that ocean acidification (enhanced by warming) may negatively affect sperm motility and fertilization success, larval metabolism, larval settlement, and post settlement growth and calcification.

Our results suggest that the population of S. stellata at Rocas Atoll has a high potential of maintenance and recovery, especially because the atoll is one of the most effective marine protected areas in the South Atlantic, and an oceanic island. Rocas is practically free of anthropogenic impacts such as declining water quality, over-exploitation of key marine species, destructive fishing and pollution but still, its location and local police cannot protect it from global- scale risks making it highly vulnerable to warming and acidification of the oceans waters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio - SISBIO N. 32331) for the logistical support at Rocas Atoll, and to M. Brito Silva, F. Osório, J. Dantas, K. Lima and R. Correia for their support during fieldwork. We thank Dr. Lisa Murphy-Goes for the English review. This research was funded by the Fundação o Boticário de Proteção à Natureza (Grant N. 0956-2012-2). B. Pinheiro received a grant from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

REFERENCES

- ALBRIGHT R. 2011. Reviewing the effects of ocean acidification on sexual reproduction and early life history stages of reef-building corals. J Mar Biol 2011: 14.

- ALBRIGHT R. ET AL. 2016. Reversal of ocean acidification enhances net coral reef calcification. Nature 531(7594): 362-365.

- ANLAUF H, D'CROZ L and O'DEA A. 2011. A corrosive concoction: The combined effects of ocean warming and acidification on the early growth of a stony coral are multiplicative. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 397: 13-20.

- ANTHONY KRN and HOEGH-GULBERG O. 2003. Variation in coral photosynthesis, respiration and growth characteristics in contrasting light microhabitats: An analogue to plants in forest gaps and understories? Funct Ecol 17: 246-259.

- ANTHONY KRN, KLEYPAS J and GATTUSO J-P. 2011. Coral reefs modify the carbon chemistry of their seawater - implications for the impacts of ocean acidification. Glob Change Biol 17: 3655-3666.

- APAC - AGENCIA PERNAMBUCANA DE ÁGUAS E CLIMA. 2014. Precipitação da Ilha de Fernando de Noronha (2013-2014) http://www.apac.pe.gov.br Acessado em 15 de agosto de 2014

» http://www.apac.pe.gov.br - BABCOCK R. 1985. Growth and mortality in juvenile corals (Goniastrea, Platygyra and Acropora): The first year. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 5, Tahiti. Proceeding of the 5th International Coral Reef Symposium, Tahiti 4: 355-360.

- BUDD AF and GUZMAN HM. 1994. Siderastrea glynni, A New Species of Scleractinian Coral (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) from the Eastern Pacific. Proc Biol Soc Washingt 107: 591-599.

- CASTRO BRT. 2008. Identificação de Recrutas Vivos, Taxas de Crescimento e Sobrevivência de Corais Recifais Brasileiros (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). Dissertação de mestrado. Museu Nacional. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 137 p. (Unpublished).

- CORDEIRO RTS, NEVES BM, ROSA-FILHO JS and PÉREZ CD. 2015. Mesophotic coral ecosystems occur offshore and north of the Amazon River. Bull Mar Sci 91(4): 491-510.

- DE'ATH G ET AL. 2009. Declining coral calcification on the Great Barrier Reef: Science 323(5910): 116-119.

- DHN - DIRETORIA DE HIDROGRAFIA E NAVEGAÇÃO. 2014. Previsão de maré. Disponível em: http://www.mar.mil.br/dhn/chm/box-previsao-mare/tabuas/index.htm Acesso em 15 de agosto de 2014

» http://www.mar.mil.br/dhn/chm/box-previsao-mare/tabuas/index.htm - ECHEVERRÍA CA, PIRES DO, MEDEIROS MS and CASTRO CB. 1997. Cnidarians of the Atol das Rocas, Brazil. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa 1: 443-446.

- EDMUNDS PJ. 2007. Evidence for a decadal-scale decline in the growth rates of juvenile Scleractinian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 341: 1-13.

- FERREIRA BP, COSTA MBSF, COXEY MS, GASPAR ALB, VELEDA D and ARAUJO M. 2012. The effects of sea surface temperature anomalies on oceanic coral reef systems in the southwestern tropical Atlantic. Coral Reefs 32: 441-454.

- FONSECA AC, VILLACA R and KNOPPERS B. 2012. Reef Flat Community Structure of Atol das Rocas, Northeast Brazil and Southwest Atlantic. J Mar Biol 2012: 1-10.

- GHERARDI DFM and BOSENCE D. 1999. Modeling of the Ecological Succession of Encrusting Organisms in Recent Coralline-Algal Frameworks from Atol Das Rocas, Brazil. Palaios 14: 145.

- GHERARDI DFM and BOSENCE D. 2001. Composition and community structure of the coralline algal reefs from Atol das Rocas, South Atlantic, Brazil. Coral Reefs 19: 205-219.

- GOES CA. 2005. Correntes superficiais no Atlântico Tropical, obtidas por dados orbitais, e sua influência na dispersão de larvas de lagosta. Dissertação de Mestrado em Sensoriamento Remoto. São José dos Campos, São Paulo (INPE-1111-TDI/ 111). Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais - INPE, 35 p. (Unpublished).

- GUZMAN HM and CORTES J. 1989. Growth rates of eight species of scleractinian corals in the eastern Pacific (Costa Rica): Bull Mar Sci 44: 1186-1194.

- GUZMAN HM and TUDHOPE AW. 1998. Seasonal variation in skeletal extension rate and stable isotopic (13C/ 12C and 18O/ 16O) composition in response to several environmental variables in the Caribbean reef coral Siderastrea sidereal: Mar Ecol Prog Series 166: 109-118.

- HARRISON PL and WALLACE CC. 1990. Reproduction, dispersal and recruitment of Scleractinian corals. In: Dubinsky Z (Ed), Ecosystems of the world, vol 25, Coral reefs. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p. 133-207.

- HELMLE KP, KOHLER KE and DODGE RE. 2002. Relative Optical Densitometry and The Coral X-radiograph Densitometry System: CoralXDS, In: Int. Soc. Reef Studies 2002 European Meeting. Cambridge.

- HOEGH-GULDBERG O. 2011. The impact of climate change on coral reef ecosystems. In: Dubinsky Z and Stambler N (Eds), Coral reefs: an ecosystem in transition. Berlin: Springer, p. 391-403.

- KAYANNE H. 2016. Response of Coral Reefs to Global Warming. In: Hayanne H (Ed), Coral Reef Science. Japan: Springer 5: 81-94.

- KIKUCHI RKP and LEÃO ZMAN. 1997. Rocas (Southwestern Equatorial Atlantic, Brazil): An Atoll Built Primarily By Coralline Algae. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa, p. 731-736.

- KLEYPAS JA, BUDDEMEIER RW, ARCHER D, GATTUSO JP, LANGDON C and OPDYKE BN. 1999a. Geochemical consequenses of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on coral reefs. Science 284: 118-120.

- KLEYPAS JA, MCMANUS JW and MENEZ LAB. 1999b. Environmetal limits to coral reef development: where do we draw the line? Amer Zool 39: 146-159.

- KROEKER KJ, KORDAS RL, CRIM R, HENDRIKS IE, RAMAJO L, SINGH GS, DUARTE CM and GATTUSO J-P. 2013. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob Chang Biol 19: 1884-1896.

- LABOREL J. 1974. West African reefs corals: An hypothesis on their origin. Proceedings of the 2nd International Coral Reef Symposium 1: 425-443.

- LAMBERT AE. 1978. Coral growth: alizarin method. In: Coral Reefs: Research Methods, Stodart DR and Johanne RE (Eds), p. 523-527.

- LEÃO ZMAN and KIKUCHI RKP. 2011. Brazil: Coral Reefs In: David H (Ed), Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs, p. 168-172.

- LEÃO ZMAN, KIKUCHI RKP and TESTA V. 2003. Corals and coral reefs of Brazil In: Cortez J (Ed), Latin American Coral Reefs, p. 9-52.

- LINS-DE-BARROS MM and PIRES DO. 2006b. Aspects of the life history of Siderastrea stellata in the tropical Western Atlantic, Brazil. Invert Reproduc Develop 49(4): 237-244.

- LINS-DE-BARROS MM and PIRES DO. 2006a. Colony size-frequency distributions among different populations of the scleractinan coral Siderastrea stellata in Southwestern Atlantic: implications for life history patterns. Brazilian J Oceanogr 54(4): 213-223.

- LINS-DE-BARROS MM and PIRES DO. 2007. Comparison of the reproductive status of the scleractinian coral Siderastrea stellata throughout a gradient of 20o of latitude. Brazilian J Oceanogr 55(1): 67-69.

- LINS-DE-BARROS MM, PIRES DO and CASTRO CB. 2003. Sexual reproduction of the Brazilian reef coral Siderastrea stellata Verrill, 1868 (Anthozoa, Scleractinia). Bull Mar Sci 73: 713-724.

- LONGO GO ET AL. 2015. Between-Habitat Variation of Benthic Cover, Reef Fish Assemblage and Feeding Pressure on the Benthos at the Only Atoll in South Atlantic: Rocas Atoll, NE Brazil. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127176.

- MAIDA M and FERREIRA BP. 1997. Coral reefs of Brazil, an overview. In: Coral Reef Symposium, 8, Balboa. Proceeding of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Balboa 1: 263-274.

- MAYAL EM, SIAL AN, FERREIRA VP, FISNER M and PINHEIRO BR. 2009. Thermal stress assessment using carbon and oxygen isotopes from Scleractinia, Rocas Atoll, northeastern Brazil. Inter Geo Review 51: 166-188.

- MUSLIC A, FLANNERY JA, REICH CD, UMBERGER DK, SMOAK JM and POORE RZ. 2013. Linear extension rates of massive corals from the Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO), Florida: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2013-1121, 22 p. (http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1121/),

» http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1121/ - NEVES EG ET AL. 2008. Genetic variation and population structuring in two brooding coral species (Siderastrea stellata and Siderastrea radians) from Brazil. Genetica 132(3): 243-254.

- NEVES EG and SILVEIRA FL. 2003. Release of planula larvae, settlement and development of Siderastrea stellata Verrill, 1868 (Anthozoa, Scleractinia). Hydrobiologia 501: 139-147.

- NEVES EG, SILVEIRA FL, PICHON M and JOHNSSON R. 2010. Cnidaria, Scleractinia, Siderastreidae, Siderastrea siderea (Ellis and Solander, 1786): Hartt Expedition and the first record of a Caribbean siderastreid in tropical Southwestern Atlantic. Check List 6: 505-510.

- NUNES FLD, NORRIS RD and KNOWLTON N. 2011. Long distance dispersal and connectivity in Amphi-Atlantic corals at regional and basin scales. PLoS ONE 6(7): e22298.

- OLIVEIRA RL. 2012. Esclerocronologia, geoquímica e registro climático em coral Siderastrea stellata do Atol das Rocas-RN, Brasil. Dissertação de mestrado. Programa de geoquímica, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niteroi, RJ, 105 p. (Unpublished).

- PEREIRA NS, MANSO VAV, SILVA AMC and SILVA MB. 2010. Mapeamento Geomorfologico e Morfodinâmica do Atol das Rocas, Atlantico Sul. Rev Gest Cost Integ 10(3): 331-345.

- PEREIRA NS, VOEGELIN AR, PAULUKAT C, SIAL NA, FERREIRA VP and FREI R. 2016. Chromium-isotope signatures in scleractinian corals from the Rocas Atoll, Tropical South Atlantic. Geobiology 14(1): 54-67.

- PINHEIRO BR. 2006. Recrutamento de corais no recife da Ilha da Barra Tamandaré -PE Dissertação de Mestrado. PPGO. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Recife, PE, 69 p. (Unpublished).

- PINIAK ET AL. 2006. Applied modeling of Coral Reef Ecosystem function and Recovery. In: Prencht WF (Ed), Corall Reef Restoration Handbook, p 95-110.

- REIS MAC and LEÃO ZMAN. 2000. Bioerosion rate of the sponge Cliona celata (Grant 1826) from reefs in turbid waters, north Bahia, Brazil. In: International Coral Reef Symposium, 9. Bali, Indonesia. Proceedings. Indonesia, Indonesian Institute of Sciences 2: 273-278.

- RICHARDSON PL and WALSH D. 1986. Mapping climatological seasonal variations of surface currents in the tropical Atlantic using ship drifts. J Geophys Res 91(C9): 10537-10550.

- SABINE CL ET AL. 2004. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 Science 305: 367-371.

- TORRES JL and MORELOCK J. 2002. Effect of terrigenous sediment influx on coral cover and linear extension rates of three Caribbean massive coral species: Caribbean Journal of Science 38(3-4): 222-229.

- VERMEIJ MJA. 2006. Early life-history dynamics of Caribbean coral species on artificial substratum: the importance of competition, growth and variation in life-history strategy. Coral Reefs 25: 59-71.

- VERON JEN. 1995. Corals in Space and Time: The Biogeography and Evolution of the Scleractinia, 321 p.

- WELLS J. 1956. Scleractinia. In: Moore R (Ed), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press, New York, p. 328-444.

- ZEEBE RE. 2012. History of seawater carbonate chemistry, atmospheric CO2, and ocean acidification. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 40: 141-165.

- ZVULONI A, ARTZY-RANDRUP Y, STONE L, VAN WOESIK R and LOYA Y. 2008. Ecological size frequency distributions: how to prevent and correct biases in spatial sampling. Limnol Oceanogr 6: 144-153.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

15 May 2017 -

Date of issue

Apr-Jun 2017

History

-

Received

16 June 2016 -

Accepted

01 Jan 2017