Abstract

Maldanids are tube-building polychaetes, known as bamboo-worms; inhabit diverse marine regions throughout the world. The subfamily Euclymeninae was proposed to include forms with anal and cephalic plates, a funnel-shaped pygidium, and a terminal anus. Euclymene, the type genus of Euclymeninae, has about 18 valid species. Euclymene vidali sp. nov. is defined and members of the species described from Northeastern Brazil. Members of this species have 23 chaetigers, and one pre-pygidial achaetous segment; nuchal grooves extend through three quarters of the cephalic plate, and there is one acicular spine with a denticulate tip. Euclymene africana, and E. watsoni, are here recognized, respectively, as Isocirrus africana comb. nov., and I. watsoni comb. nov. Three monotypic genera are invalid: Macroclymenella, Eupraxillella, and Pseudoclyemene; their species should be recognized as Clymenella stewartensis com. nov., Praxillella antarctica com. nov., and Praxillela quadrilobata com. nov., respectively. An identification key and a comparative table for all species of Euclymene are provided. A comparative table for all genera of Euclymeninae is also furnished. The paraphyletic status of Euclymene and Euclymeninae is discussed. The taxon Maldanoplaca is not code compliant and should only be regarded as an informal name.

Key words

Euclymeninae; Maldanidae; new species; polychaeta; systematics

INTRODUCTION

Maldanids are sedentary, tube-building polychaetes, commonly known as bamboo worms (Fauchald 1977Fauchald K. 1977. The polychaete worms. Definitions and keys to the orders, families and genera. Nat Hist Mus Los Angeles Coun Sci Ser 28: 1-188., Imajima & Shiraki 1982Imajima M & Shiraki Y. 1982. Maldanidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from Japan. Part 1. Bul Nat Scie Mus Tokyo, Ser. A Zool 8: 7-40., Lee & Paik 1986Lee JH & Paik EI. 1986. Polychaetous annelids from the Yellow Sea: III. Family Maldanidae (Part 1). Oce Res 8: 13-25., Fauchald & Rouse 1997Fauchald K & Rouse GW. 1997. Polychaete systematics: past and present. Zool Scr 26: 71-138. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.1997.tb00411.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.1997...

, Rouse 2001Rouse GW. 2001. Maldanidae Malmgren, 1867. In: Rouse GW & Pleijel F (Eds). Polychaetes. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, p. 49-52., De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

). Their tubes are constructed either horizontally, with sand and shell fragments under rocks, or vertically in sandy bottoms with fine sand in marine regions, or with mud in estuaries (Day 1967DAY JH. 1967. A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part2. Sedentaria. London, United Kingdom: British Museum National History Publications, p. 459-842., Jiménez-Cueto & Salazar-Vallejo 1997Jiménez-Cueto MS & Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1997. Maldánidos (Polychaeta) del Caribe Mexicano con una clave para las especies del Gran Caribe. Rev Biol Trop 45: 1459-1480., De Assis et al. 2007De Assis JE, Alonso-Samiguel C & Christoffersen ML. 2007. Two new species of Nicomache (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) from the Southwest Atlantic. Zootaxa 1454: 27-37.). Tubes are mucus-lined or have an inner organic sheath secreted by the worm. The internal fibers of this sheath may become hardened by the incorporation of fine sediment (e.g., mud), and these may become agglutinated into several layers (Pilgrim 1977Pilgrim M. 1977. The functional morphology and possible taxonomic significance of the parapodia of the maldanid polychaetes Clymenella torquata and Euclymene oerstedi. J Morph 152: 281-302., Shcherbakova et al. 2017Shcherbakova TD, Tzetlin AB, Mardashova MV & Sokolova OS. 2017. Fine structure of the tubes of Maldanidae (Annelida). J Mar Biol Assoc UK 97: 1177-1187. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531541700114X.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531541700114...

). Individual species are found in estuaries, or from other intertidal habitats to the deep sea (Arwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308., Chamberlin 1919, De Assis et al. 2007De Assis JE, Alonso-Samiguel C & Christoffersen ML. 2007. Two new species of Nicomache (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) from the Southwest Atlantic. Zootaxa 1454: 27-37.).

Arwidsson (1906)Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308. presented a revision of maldanids based on the Scandinavian and Arctic fauna. He proposed the subfamily Euclymeninae to include forms with cephalic and anal plates, and a funnel-shaped pygidium bordered by cirri or crenulated. All euclymenins present a terminal anus, and members of some species have a ventral valve. In this revision, Arwidsson proposed Isocirrus to include species with members that have anal cirri of the same length. On the other hand, comparisons among members of species have shown that members of Euclymene have at least one midventral cirrus longer than remaining cirri (Salazar-Vallejo 1991Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1991. Revisión de algunos eucliméninos (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) del Golfo de California, Florida, Panamá y Estrecho de Magallanes. Rev Biol Trop 39: 269-278.).

Members of Euclymene present the following features: 18‒24 chaetigers, and one or more achaetous preanal segments; longitudinal glandular stripes can be present among members of some species. The presence of a midventral cirrus that is longer than remining cirri has been the main feature used to distinguish this genus (Quatrefages 1865Quatrefages AD. 1865. Note sur la classification des annélides. Ann Scie Nat 5: 253-296., 1866, Arwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308., Day 1955Day JH. 1955. The Polychaeta of South Africa. Part 3. Sedentary species from Cape shores and estuaries. J Linn Soc London, Zool 42: 407-452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1955.tb02216.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1955...

, 1967, De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

, De Assis et al. 2012De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.). However, Euclymene is paraphyletic (De Assis, pers. obs.) and this character is not unique to members of the genus (see below).

Members of Euclymene occur from estuarine and intertidal regions to the deep sea, in sandy bottoms or on coral reefs (Jiménez-Cueto & Salazar-Vallejo 1997Jiménez-Cueto MS & Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1997. Maldánidos (Polychaeta) del Caribe Mexicano con una clave para las especies del Gran Caribe. Rev Biol Trop 45: 1459-1480.). They have been reported from all oceans, especially in shallow coastal regions. However, most reports are from European waters, the North Atlantic and Mediterranean (Fauvel 1927FAUVEL P. 1927. Polychètes sédentaires. Addenda aux errantes, Archiannélides, Myzostomaires. Faune de France vol. 16. Paris, France: Librairie de la Facult des Sciences Paul: Lechevalier, 494 p., Read & Fauchald 2020Read G & Fauchald K. 2020. World Polychaeta database. Euclymene Verrill, 1900. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetailsandid=129347 on 2020-08-06.

http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p...

). Members of the following species have been recorded from Brazil: E. droebachiensis (M. Sars, 1872), described originally from Faroe Island, North Atlantic, and E. coronata Verrill, 1900, described originally from Castle Island, Boston, USA, were subsequently reported from the north coast of the State of São Paulo; E. oerstedii (Claparède, 1863), described originally from Normandy, Atlantic Ocean, and reported from the northern coast of São Paulo and Guanabara Bay, State of Rio de Janeiro; E. lombricoides (Quatrefages, 1865), described originally from Boulogne-Sur-Mer and Calais Beach, France, have been collected in Bacia de Campos, Rio de Janeiro (Amaral et al. 2013Amaral ACZ, Nallin SAH, Steiner TM, Forroni TO & Gomes DF. 2013. Catálogo das espécies de Annelida Polychaeta do Brasil. http://www.ib.unicamp.br/museu_zoologia/files/lab_museu_zoologia/Catalogo_Polychaeta_Amaral_et_al_2012.pdf (accessed in Jan. 2019).

http://www.ib.unicamp.br/museu_zoologia/...

), and E. coronata are reported from northeastern Brazil (De Assis et al. 2012De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.).

The aim of this study is to present a new Euclymene species, with members from northeastern Brazil, and to transfer E. africana (Gravier, 1905) and E. watsoni (Gravier, 1905) to Isocirrus Arwidsson, 1906. In addition, we discuss the status of Euclymeninae as a phylogenetic hypothesis.

The ZooBank Life Science Identifier (LSID) of this publication is: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:37A4F888-E91C-4017-9F3A-906CDE8F186C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens of the new species were collected in the estuary of Diogo Lopes Macau, Rio Grande do Norte, and the estuary from Barra de Mamanguape River, Rio Tinto, Paraíba, both in northeastern Brazil (Fig. 1). Specimens were fixed in 10% seawater-formalin, and later rinsed with fresh water, then preserved in 70% ethanol. Specimens were observed with a Zeiss stereo microscope. Rostrate and acicular hooks were observed with an Olympus BX41 compound microscope. For scanning electron microscopy, worms were washed twice in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 h at room temperature. They were then fixed again in 1% osmium tetroxide with a phosphate buffer for 1 h at room temperature. All worms were dehydrated into 100% ethanol, critical-point-dried in CO2, mounted on stubs, coated with gold, and examined using a JEOL 25SII scanning electron microscope. The type material is deposited in Universidade Federal da Paraíba, CIPY-POLY-UFPB. All line drawings were made using a camera lucida. Illustrations were prepared using CorelDraw. Measurements are in millimeters and microns.

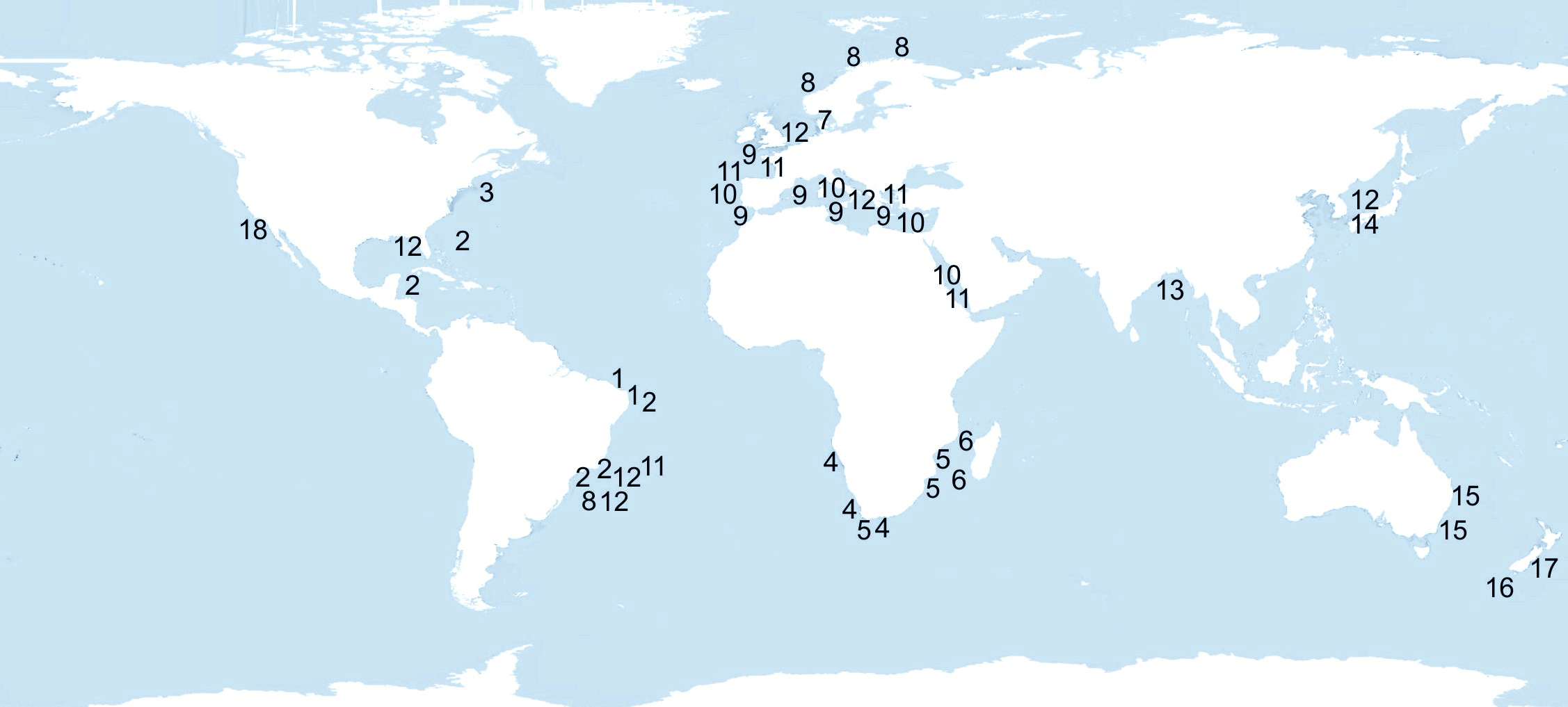

Map of distribution of Euclymene species, including the new species described in this paper. (1) E. vidali sp. nov., (2) E. coronata, (3) E. dispar, (4) E. luderitziana, (5) E. natalensis, (6) E. mossambica, (7) E. lindrothi, (8) E. droebachiensis, (9) E. palermitana, (10) E. collaris, (11) E. lombricoides, (12) E. oerstedii, (13) E. annandalei, (14) E. uncinata, (15) E. trinalis, (16) E. aucklandica, (17) E. insecta, (18) E. delineata.

The treatment of taxa in this paper follows from the view that they are explanatory hypotheses, as opposed to being ontological entities, individuals, things, or just groupings of individuals (Fitzhugh 2005Fitzhugh K. 2005. The inferential basis of species hypotheses: the solution to defining the term ‘species’. Mar Ecol 26: 155-165.Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.2005.00058.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.2005...

, 2008, 2009, 2010a-b, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016a-b, Fitzhugh et al. 2015Fitzhugh K, Nogueira JMM, Carrerette O & Hutchings P. 2015. An assessment of the status of Polycirridae genera (Annelida: Terebelliformia) and evolutionary transformation series of characters within the family. Zool J Linn Soc 174: 666-701. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12259.

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12259...

, Nogueira et al. 2010Nogueira JMM, Fitzhugh K & Rossi MCS. 2010. A new genus and new species of fan worms (Polychaeta: Sabellidae) from Atlantic and Pacific Oceans – the formal treatment of taxon names as explanatory hypotheses. Zootaxa 2603: 1-52., 2013Nogueira JMM, Carrerette O, Hutchings P & Fitzhugh K. 2018. Systematic review of the species of the family Telothelepodidae Nogueira, Fitzhugh and Hutchings, 2013 (Annelida: Polychaeta), with descriptions of three new species. Mar Biol Res 14: 217-257., 2017Nogueira JMM, Fitzhugh K & Hutchings P. 2013. The continuing challenge of phylogenetic relationships in Terebelliformia (Annelida: Polychaeta). Invert Syst 27: 186-238., 2018Nogueira JMM, Fitzhugh K, Hutchings P & Carrerette O. 2017. Phylogenetic analysis of the family Telothelepodidae Nogueira, Fitzhugh and Hutchings, 2013 (Annelida: Polychaeta). Mar Biol Res 13: 671-692.). If possible, formal definitions of relevant taxa will be presented, per the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1999)INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE. 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. London: The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. Article 13.1.1, as referring to either phylogenetic or specific hypotheses.

RESULTS

Systematics

Family Maldanidae Malmgren, 1867

Subfamily Euclymeninae Arwidsson, 1906

Genus Euclymene Verrill, 1900

Euclymene Verrill, 1900, p. 654–655; Arwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308., pp. 220–221, Day 1967DAY JH. 1967. A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part2. Sedentaria. London, United Kingdom: British Museum National History Publications, p. 459-842., p. 134, Fauchald 1977Fauchald K. 1977. The polychaete worms. Definitions and keys to the orders, families and genera. Nat Hist Mus Los Angeles Coun Sci Ser 28: 1-188., p. 40, Salazar-Vallejo 1991Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1991. Revisión de algunos eucliméninos (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) del Golfo de California, Florida, Panamá y Estrecho de Magallanes. Rev Biol Trop 39: 269-278., pp. 275–276, De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

, p. 242.

Type-species: Clymene amphistoma Lamarck, 1818: p. 341.

Definition: There is no phylogenetic hypothesis to which Euclymene refers (cf. Fitzhugh 2008Fitzhugh K. 2008. Abductive inference: implications for ‘Linnean’ and ‘phylogenetic’ approaches for representing biological systematization. Evol Biol 35: 52-82. Doi: 10.1007/s11692-008-9015-x.) since this taxon denotes a paraphyletic group. Thus, a formal definition of the name cannot be provided at this time.

The following characters differentiate individuals to which the name Euclymene refers from individuals to which other Maldanidae genera refer: body with 18–24 chaetigers; 1–2 acicular spines on first three chaetigers, with smooth or dentate tips; cephalic plate with deep or slight lateral notches; posterior edge of cephalic plate smooth or crenulated; notochaetae include limbate capillaries and slender forms; uncini with 3–7 teeth above rostrum; 1–4 pre-pygidial achaetous segments; midventral cirrus longer than other cirri; anus close to anal plate.

Remarks: The inability to define the name Euclymene as representing a phylogenetic hypothesis is due the fact that the taxon is currently presumed paraphyletic; there are no synapomorphies currently recognized (cf. Table I). A future phylogenetic analysis involving members of Euclymene species will be required to resolve this issue.

Comparative table to all genera of Euclymeninae. Note that some genera are not present exclusive characters. N/A = Not applicable. * Heteroclymene is the unique taxon of Euclymeninae that species present acicular spine on chaetiger 4.

Euclymene vidali sp. nov.

ZooBank Life Science Identifier (LSID) - urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:71ADFA40-55F8-42E8-B5D7-43015573A054.

(Figures 2a-f, 3a-f, 4a-b, 5a-d, 6a-d)

Johnstonia sp. De Assis & Christoffersen, 2011, p. 234, Figures 2, 3, 5, 6.

Material examined: Holotype: Brazil: Diogo Lopes, Macau -Rio Grande do Norte, northeastern Brazil, in tidal creek and mud (1.8–5.2 m). CIPY-POLY-UFPB 1745: José Eriberto De Assis and André Vidal col., September 2007, (5°05´02.95” S; 36°27´13.50” W).

Paratypes: CIPY-POLY-UFPB 1746 (1 complete specimen), (2) 1747, (5°04´27.23” S; 36°27´32.02” W); CIPY-POLY-UFPB 1748, (3 complete specimens) (4 anterior and posterior fragments) CIPY-POLY-UFPB 1749: (5°04´55.01” S; 36°26´31.85” W); Barra do Rio Mamanguape, Rio Tinto, Paraíba, tidal creek and mud: CIPY–POLY–UFPB 1749 (5: 2 complete specimens, 3 broken specimens): José Eriberto De Assis, André Vidal, and Carmen Alonso Col. January 2018 (6°46’04.07” S; 34°56’05.0” W).

Definition: A specific hypothesis, accounting for the following characters: presence of 23 chaetigers, cephalic plate with smooth posterior margin, and serrate capillary chaetae on chaetiger 9 arranged as dense bundle. Hypothetically, each of these characters arose among members of an ancestral population, eventually becoming fixed, resulting in individuals observed in the present.

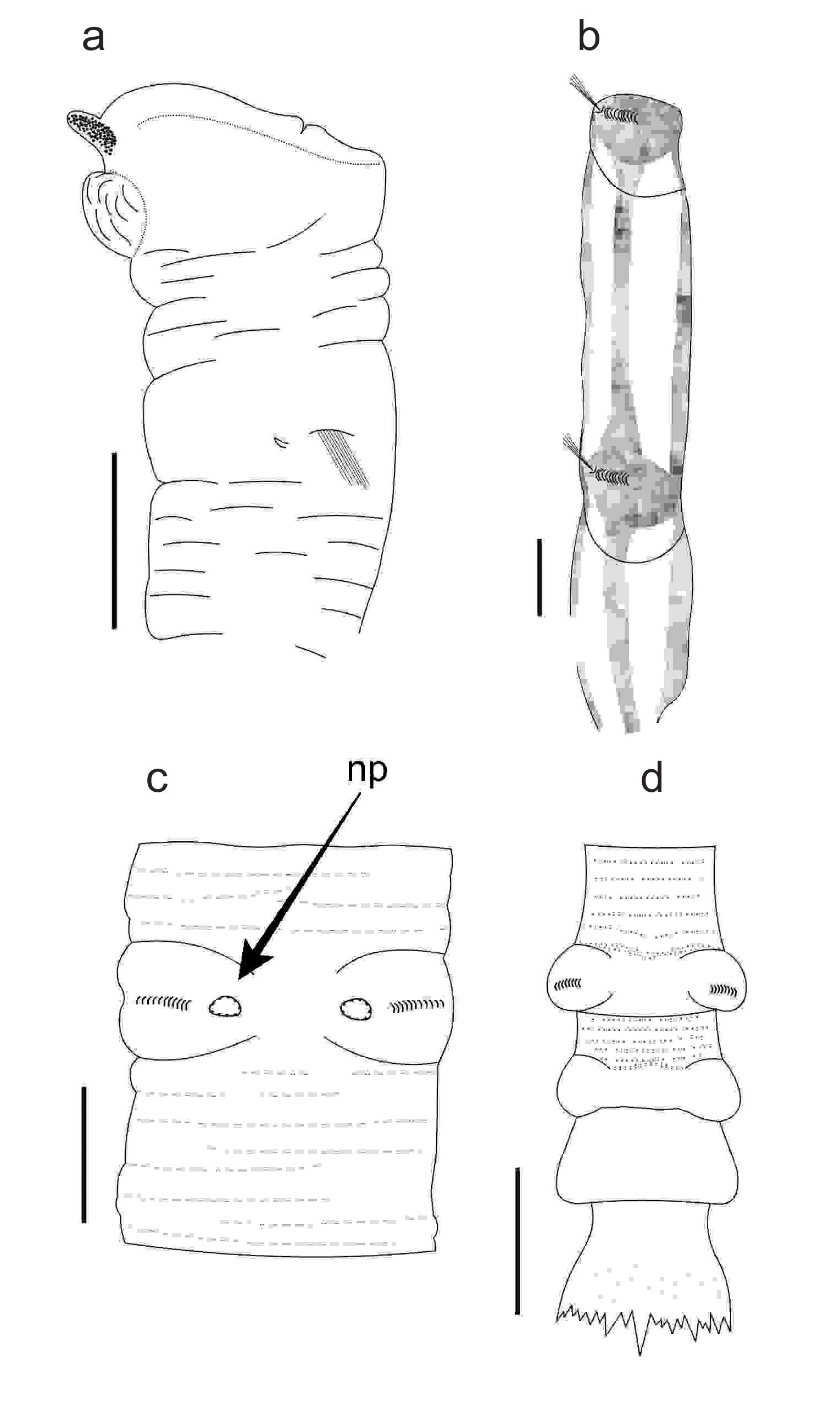

Description of adult semaphoronts: The holotype is a complete specimen, length 50 mm, 1.5 mm wide. Paratypes 48‒62 mm long, 1.7‒2.0 mm wide. Body cylindrical; 23 chaetigers, one pre-pygidial achaetous segment, one thinner callus ring, pygidial funnel. Anterior end with oval cephalic plate bordered by well-developed cephalic rim. Cephalic rim smooth, with two deep lateral notches and one posterior notch. Prostomium broadly rounded, forming slightly arched keel; about 10 red-brown ventrolateral ocelli. Nuchal grooves parallel, extending through three-quarters of cephalic plate length. Mouth below prostomium, with wrinkled lower lip. Proboscis a smooth eversible sac (Figs. 2a-c, 5a). Chaetigers 1–7 varying from 1.5‒2.0 mm long, 1.5 mm wide. Chaetigers 8–9 two times longer than anterior chaetigers; chaetigers 10–16 three times longer than first chaetiger; posterior chaetigers decreasing in length. Notochaetae emerge from depressions; neurochaetae project directly from body wall on anterior half of each segment (Fig. 2d-f). Remaining chaetigers with small raised notopodia and conspicuous neuropodial tori. Notopodia of chaetigers 1–23 with fascicles of long, fine capillary chaetae, each with attached microalgal filaments. Notochaetae of all chaetigers with posterior row of long, sheathed capillaries, and anterior row of shorter modified capillaries (Figs. 2e-f). These chaetae have a short base and are of three types: limbate; spinose; modified serrate (Figs. 3a-c, 6b-c). Chaetae on chaetiger 9 arranged in dense bundle (Fig. 2e). Neuropodia of chaetigers 1–3 each with one acicular hook, with small denticles above main fang (Figs. 3d, 6a). Posterior to chaetiger 3, neuropodia with row of rostrate hooks, present to chaetiger 23 (Figs. 3e-f); each hook with rostrum surmounted by 4 smaller denticles; single thick barbule, bent upwards, present below rostrum. Hook rows arranged perpendicular to body wall, with long, curved posterior shaft, and prominent manubrium on posterior half. Neuropodial tori with variable number of rostrate hooks (4: 11, 5: 15, 6: 22) (Figs. 3e-f; 6d). Pre-pygidial segment about one half length of last chaetiger, with reduced torus at posterior end. Distinct callus ring in posterior region of segment (Fig. 4a-b). Pygidial funnel extended posteriorly, bearing 22 subconical anal cirri of slightly variable length (paratypes with 19‒27); midventral cirrus two times longer than other cirri. Anus terminal, central, surrounded by divergent folds (Figs. 4a-b, 5d).

Euclymene vidali sp. nov. (a), Anterior end showing the first four chaetigers and mouth; (b) anterior end showing first achaetigerous segment, and peristomium; (c) Cephalic plate showing nuchal grooves and length of prostomium (Modified from De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60... ); (d) Parapodium showing acicular spine and capillary chaetae (Modified from De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60... ); (e) Parapodium from chaetiger 9, showing modified serrate capillary chaetae, and limbate capillary chaetae; (f) Parapodium from chaetiger 15 showing spinose, and limbate capillaries chaetae. Abbreviations: acha, achaetiger head; as, acicular spine; cha, chaetigers; cp, cephalic plate; sec, serrate capillary chaetae; lic, limbate capillary chaetae; spc, spinose capillary chaetae chaetae; m, mouth; nc, notochaetae; ng, nuchal groove; pe, peristomium; pr, prostomium; sc, spinose capillary. Scales bars: (a) = 1 mm; (b) = 300 µm, (c, d, e, f) = 100 µm.

a) Tufts of modified serrate capillary chaetae from chaetiger 9; (b-c) spinose and limbate capillaries chaetae from chaetiger of segment 15; (d) acicular spine of first chaetigerous segment, with denticulate tip; (e) Row of rostrate uncini from chaetigerous segment 15; (f) Rostrate uncini from chaetigerous segment 15 showing capitium, rostrum and barbules. Abbreviations: as, acicular spine; b, barbules; c, capitium, d, denticules; sec, serrate capillary chaetae; lic, limbate capillary chaetae; r, rostrum, ru, rostrate uncini; sc, spinose capillary chaetae. Scales bars: (a-f) = 10 μm.

(a) Posterior end of Euclymene vidali sp. nov. Showing the pre-pygidial achaetous segment and pygidium (Modified from De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60... ); (b) Anal funnel with sub-triangular cirri showing a long midventral cirrus (Modified from De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60... ). Abbreviations: ac, anal cirri; ppa, pre-pygidial achaetiger; ch, chaetigers; cr, callus ring; mvc, medioventral cirrus; ne, neuropodium; nt, notopodium; p, pygidium. Scales bars: (a) = 1 mm, (b) = 200 µm.

Live specimens dark red in anterior region, light yellow in median and posterior regions. Preserved specimens (in alcohol) uniformly yellow. Tubes composed of sand, shells, fine wood fragments, small stones, all adhered to mucous matrix. Chaetigers 8–13 with strongly marked stripes, neuropodial regions glandular, arranged into four equidistant, longitudinal glandular bands (one dorsal, one ventral, two lateral). Dorsal glandular stripes extend to chaetiger 13; ventral strips to chaetiger 14 (Fig. 5b). Low, rounded nephridial papillae below posterior regions of neuropodial tori on chaetigers 7–9 (Fig. 5c).

(a) anterior end of Euclymene vidali sp. nov. showing the first chaetigerous segment and prostomium with ocelli; (b) Median segments of Euclymene vidali sp. nov. showing longitudinal glandular strips; (c) Nephridial papillae from chaetigerous segment 6; (d) Posterior end of Euclymene vidali sp. nov. with one preanal achaetigerous segment and pygidium. Abbreviation: Np, nephridial papillae. Scales bars: (a and d) = 1 mm, (b and c) = 300 µm.

Distribution: Specimens live in sandy mud, intertidal (type locality) to 1.8‒5.2 m depth. Known only from Brazilian northeastern littoral, for the Rio Grande do Norte and Paraíba States.

Etymology: The species name is after the companion of the first author, André Vidal, who assisted in the collection of material.

Remarks: Members of Euclymene vidali sp. nov. differ from members of E. aucklandica Augener, 1923, in that the latter has 21 chaetigers, cephalic plate with crenulated posterior edge, uncini with 4–5 teeth on the rostrum, and midventral cirrus two times longer than other anal cirri. Members of E. vidali sp. nov. differs from members of E. coronata as the latter has 22 chaetigers, deep lateral notches, cephalic plate with a strongly crenulated posterior edge, and uncini with 3 teeth on the rostrum. Members of other species of Euclymene differ from E. vidali sp. nov. in having 2–4 pre-pygidial achaetigerous segments, and the number of chaetigers (Table II).

Comparative table of Euclymene species that have midventral cirrus longer than other anal cirri. The sequence of species is according to the number of pre-pygidial achaetigerous segments.

Key to species of Euclymene Verrill, 1900

1. One pre-pygidial achaetous segment........................2

– More than one pre-pygidial achaetous segment.......................................4

2. Midventral cirrus two times longer than other anal cirri.................................3

– Midventral cirrus four times longer than other anal cirri; 21 chaetigers; posterior edge of cephalic plate slightly crenulated; uncini with 4–5 teeth above rostrum......................................E. aucklandica Augener, 1923

3. Twenty-two chaetigers; deep lateral notches; cephalic plate strongly crenulated edge; uncini with three teeth above rostrum.................. E. coronata Verrill, 1900

– Twenty-three chaetigers; slight lateral notches; cephalic plate with smooth edge; uncini with four teeth above rostrum; midventral cirrus two times longer than other anal cirri.........................................................................................E. vidali sp. nov.

4. Two pre-pygidial achaetous segments...............................................................................5

– Three or more pre-pygidial achaetous segments.............................................................................14

5. Posterior edge of cephalic plate smooth...............................................................................................6

– Posterior edge of cephalic plate crenulated............................................................................11

6. Less than 20 chaetigerous segments................................................................................7

– Twenty-four chaetigers; uncini with 6–7 teeth above rostrum; midventral anal cirrus three times longer than other cirri......E. luderitziana Augener, 1918

7. Nineteen chaetigers.............................................8

– Eighteen chaetigers; midventral anal cirrus four times longer than other cirri.......................................................................................E. dispar (Verril, 1873)

8. Midventral cirrus three times longer than other anal cirri.....................................................................9

– Midventral cirrus two times longer than other anal cirri...................................................................10

9. Cephalic plate with slightly lateral and posterior notches; uncini with four teeth above rostrum...............................E. trinalis Hutchings, 1974

– Cephalic plate with deep lateral and posterior notches; uncini with five teeth above rostrum........................E. droebachiensis (Sars, 1872)

10. Cephalic plate with well-developed edge; anal cirri all of similar length; uncini with five teeth above rostrum.............E. natalensis Day, 1957

– Cephalic plate with low edge; anal cirri alternating in length; uncini with 5–6 teeth above rostrum..........................E. oerstedii (Claparède 1863)

11. Less than 20 chaetigers..................................12

– Twenty-one chaetigers .................................................................................E. annandalei Southern, 1921

12. Nineteen chaetigers........................................13

– Ten chaetigers; cephalic plate with slight lateral notches; posterior edge slightly crenulated ..........................E. delineata* Moore, 1923

13. Posterior edge of cephalic plate slightly crenulated; with very small midventral anal cirrus; other cirri short, subconical and of similar length..............E. uncinata Imajima & Shiraki, 1982

– Posterior edge of cephalic plate strongly crenulated; first three chaetigers with 1–2 rostrate hooks; midventral anal cirrus two times longer than other anal cirri, conical, of similar length.....................................E. mossambica Day, 1957

14. Three pre-pygidial achaetous segments..............................................................................15

– Four pre-pygidial achaetous segments; cephalic plate slightly crenulated; midventral anal cirrus two times longer than other anal cirri, remaining cirri of similar length.......E. lindrothi Eliason, 1962

15. Posterior edge of cephalic plate smooth..............................................................................................16

– Posterior edge of cephalic plate crenulated; midventral anal cirrus two times longer than others similar lengths.....E. lombricoides (Quatrefages, 1865)

16. Nineteen chaetigers........................................17

– Twenty chaetigers; cephalic plate with deep lateral notches; midventral anal cirrus three times longer than other cirri...........E. palermitana (Grube, 1840)

17. Cephalic plate with shallow notches; uncini with five teeth above rostrum; mid-ventral anal cirrus two times longer than other cirri ...................................E. insecta (Ehlers, 1905)

– Cephalic plate with strong lateral notches; uncini with four teeth above rostrum; midventral anal cirrus two times longer than other cirri ............................................E. collaris (Claparède, 1869)

* Members of E. delineata were described on the basis of anterior and posterior body fragments, which indicates that the numbers furnished do not represent the actual number of chaetigers. The species is included in this group since individuals have two achaetous pre-pygidial segments and a crenulated posterior edge of the cephalic plate.

DISCUSSION

Genera of Euclymeninae can be distinguished by several characters, summarized in Table I. Three monotypic genera are synonymized here: Macroclymenella Augener, 1926, Eupraxillella Hartmann-Schröder & Rosenlfelft, 1989Hartmann-Schröder G & Rosenfeldt P. 1989. Die Polychaeten der Polarstern-Reise ANT III/2 in die Antarktis 1984. Teil 2: Cirratulidae bis Serpulidae. Mitt Hamb Zoolog Mus Instit 86: 65-106., and Pseudoclymene Arwidsson, 1906.

Members of Macroclymenella were described as having 31‒34 chaetigers, one pre-pygidial achaetiger, and a circular collar on chaetiger 4. The last character is unique for members of Clymenella. Yet, the number of chaetigers among members of Clymenella varies between 18 and 39, and there are 0 to 5 pre-pygidial achaetigers (Table II). In fact, the presence of a circular collar on chaetiger 4 indicates that Macroclymenella is a junior synonym of Clymenella, and thus, M. stewartensis Augener, 1926, must thus be recognized as Clymenella stewartensis comb. nov.

Members of Eupraxillella Hartmann-Schröder & Rosenlfelft, 1989, were described with 30 chaetigers, four pre-pygidial achaetigers, a pygidium with a short edge, and with a ring of cirri; anus on the cone, with anal ventral valve. The form of the pygidium (with an anal pore located over the cone), and anal valve are typical for members of Praxillella. The number of chaetigers among members of Praxillella varies from 18 to 19, and there are 3‒4 pre-pygidial achaetigers. Based especially on the pygidium, position of the anus and anal valve, Eupraxillella is a junior synonym of Praxillella, and Eupraxillella antarctica Hartmann-Schröder & Rosenlfelft, 1989, must be recognized as Praxillella antarctica com. nov.

PseudoclyemeneArwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308. was erected on the basis of the length of the nuchal grooves. This is a unique character for the genus. However, members of this species have a pygidium with a short edge, and a ring of cirri of different lengths; the anus is located on the cone. Although Arwidsson (1906)Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308. does not describe the presence of an anal valve, the original figures resemble typical specimens of Praxillella. In this case, we recognize Pseudoclyemene as a junior synonym of Praxillella, and P. quadrilobata Arwidsson, 1906, must be recognized as Praxillella quadrilobata com. nov.

Members of Euclymene africana (Gravier 1905Gravier C. 1905. Sur les Annélides Polychètes de la Mer Rouge (Cirratuliens (suite), Maldaniens, Amphicténiens, Térébelliens). Bul Mus Hist Nat Paris Ser. 1 11: 319-326., p. 198–201, Figs. 214–216), and E. watsoni (Gravier 1905Gravier C. 1905. Sur les Annélides Polychètes de la Mer Rouge (Cirratuliens (suite), Maldaniens, Amphicténiens, Térébelliens). Bul Mus Hist Nat Paris Ser. 1 11: 319-326., p. 201–203, Figs. 2017–2219) were originally described from Djibouti, Gulf of Aden, East Africa. In the original descriptions and illustrations, the specimens presented a pygidium with an anal funnel bordered by several anal cirri of equal length. This condition is part of what characterizes members of Isocirrus (Arwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308., Salazar-Vallejo 1991Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1991. Revisión de algunos eucliméninos (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) del Golfo de California, Florida, Panamá y Estrecho de Magallanes. Rev Biol Trop 39: 269-278., De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

, De Assis et al. 2012De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.). From both the text and figures, it is clear that members of the species do not present a midventral cirrus that is longer than the remaining cirri, a condition that is part of the definition of Euclymene. Therefore, these species are herein transferred to Isocirrus: I. africana (Gravier, 1905) comb. nov., and I. watsoni (Gravier, 1905) comb. nov.

Comments on monophyly of Euclymeninae: In their inferences of phylogenetic hypotheses explaining morphological characters among members of Maldanidae, De Assis & Christoffersen (2011)De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

found Euclymeninae to be monophyletic. Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

subsequently inferred phylogenetic hypotheses for only sequence data and obtained a paraphyletic Euclymeninae due to members of Nicomachinae within the former clade. Based on their results, Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

concluded that the morphological characters used by De Assis & Christoffersen (2011)De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

are not synapomorphies for Euclymeninae. We will first comment on inherent limitations to inferring phylogenetic hypotheses for sequence data, the error of relying on phylogenetic hypotheses for sequence data as the means of determine explanatory hypotheses for other classes of characters, then address those characters that establish monophyly of Euclymeninae.

It has become fashionable in polychaete systematics to focus on inferences of phylogenetic hypotheses based only on sequence data (e.g. Struck et al. 2011Struck TH, Paul C, Hill N, Hartmann S, Hösel C, Kube M, Lieb B, Meyer A, Tiedemann R, Purschke G & Bleidorn C. 2011. Phylogenomic analyses unravel annelid evolution. Nature 471: 95-98., 2015Struck TH, Golombek A, Weigert A, Franke FA, Westheide W, Purschke G, Bleidorn C & Halanych KM. 2015. The evolution of annelids reveals two adaptive routes to the interstitial realm. Curr Biol 25: 1993-1999. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.007.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.00...

, Borda et al. 2012Borda E, Kudenov JD, Bienhold C & Rouse GW. 2012. Towards a revised Amphinomidae (Annelida, Amphinomida): description and affinities of a new genus and species from the Nile Deep-sea Fan, Mediterranean Sea. Zool Scr 41:307-325. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00529.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012...

, Glasby et al. 2012Glasby CJ, Schroeder PC & Aguado MT. 2012. Branching out: a remarkable new branching syllid (Annelida) living in a Petrosia sponge (Porifera: Demospongiae). Zool J Linn Soc 164: 481-497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00800.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011...

, Goto et al. 2013Goto R, Okamoto T, Ishikawa H, Hamamura Y & Kato M. 2013. Molecular phylogeny of echiuran worms (Phylum: Annelida) reveals evolutionary pattern of feeding mode and sexual dimorphism. PLoS ONE 8: e56809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056809.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.005...

, Weigert et al. 2014Weigert A et al. 2014. Illuminating the base of the annelid tree using transcriptomics. Mol Biol Evol 31: 1391-1401. Doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu080., Aguado et al. 2015Aguado MT, Glasby CJ, Schroeder PC, Weigert A & Bleidorn C. 2015. The making of a branching annelid: an analysis of complete mitochondrial genome and ribosomal data of Ramisyllis multicaudata. Nat Sci Rep 5: 12072. doi: 10.1038/srep12072., Goto 2016Goto R. 2016. A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of spoon worms (Echiura, Annelida): Implications for morphological evolution, the origin of dwarf males, and habitat shifts. Mol Phylogen Evol. 99: 247-260. Doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.03.003., Weigert & Bleidorn 2016Weigert A & Bleidorn C. 2016. Current status of annelid phylogeny. Org Divers Evol 16: 345-362. Doi:10.1007/s13127-016-0265-7., Kobayashi et al. 2018Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

, Nygren et al. 2018Nygren A, Parapar J, Pons J, Meißner K, Bakken T, Kongsrud JA, Oug E, Gaeva D, Sikorski A, Johansen RA, Hutchings PA, Lavesque N & Capa M. 2018. A mega-cryptic species complex hidden among one of the most common annelids in the North East Atlantic. PLoS ONE 13(6): e0198356. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198356., Langeneck et al. 2019Langeneck J, Barbieri M, Maltagliati F & Castelli A. 2019. Molecular phylogeny of Paraonidae (Annelida). Mol Phylogen Evol 136: 1-13. Doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.03.023., Shimabukuro et al. 2019Shimabukuro M, Carrerette O, Alfaro-Lucas JM, Rizzo AE, Halanych KM & Sumida PYG. 2019. Diversity, distribution and phylogeny of Hesionidae (Annelida) colonizing whale falls: new species of Sirsoe and connections between ocean basins. Front Mar Scie 6(478): 1-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00478.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00478...

, Alves et al. 2020Alves PR, Halanych KM & Santos CSG. 2020. The phylogeny of Nereididae (Annelida) based on mitochondrial genomes. Zool Scr 49: 366-378. https://doi.org/10.1111/zsc.12413.

https://doi.org/10.1111/zsc.12413...

, San Martín et al. 2020San Martín G, Álvarez-Campos P, Kondo Y, Núñez J, Fernández-Álamo MA, Pleijel F, Goetz FE, Nygren A & Osborn K. 2020. New symbiotic association in marine annelids: ectoparasites of comb jellies. Zool J Linn Soc zlaa034. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa034.

https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa0...

, Stiller et al. 2020Stiller J, Tilic E, Rousset V, Pleijel F & Rouse GW. 2020. Spaghetti to a tree: a robust phylogeny for Terebelliformia (Annelida) based on transcriptomes, molecular and morphological data. Biology. 9: 73-100. doi.org/10.3390/biology9040073.

https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9040073....

, Tilic et al. 2020Tilic E, Sayyari E, Stiller J, Mirarab S & Rouse GW. 2020. More is needed‒Thousands of loci are required to elucidate the relationships of the ‘flowers of the sea’ (Sabellida, Annelida). Mol Phylogen Evol 151. doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106892.), and often to then comment on other classes of characters in relation to those hypotheses, typically through the process called ‘character mapping.’ Two significant, interrelated problematic questions arise with these approaches: can inferences of phylogenetic hypotheses causally account for sequence data, and can other classes of characters be explained through mapping on the basis of those inferred hypotheses? In-depth treatments of these topics can be found for instance in Fitzhugh (2014Fitzhugh K. 2009. Species as explanatory hypotheses: refinements and implications. Acta Biotheor 57:201-248. Doi: 10.1007/s10441-009-9071-3., 2016aFitzhugh K. 2010a. Evidence for evolution versus evidence for intelligent design: parallel confusions. Evol Biol 37: 68-92.), so only a brief overview will be presented here.

In accordance with the goal of scientific inquiry, which is to obtain causal understanding (e.g. Hanson 1958Hanson NR. 1958. Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 241 p., Hempel 1965Hempel CG. 1965. Aspects of Scientific Explanation and other Essays in the Philosophy of Science. New York, USA: The Free Press, 505 p., Rescher 1970Rescher N. 1970. Scientific Explanation. New York, USA: The Free Press, 242 p., Popper 1983Popper KR. 1983. Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 395 p., 1992Popper KR. 1992. Realism and the Aim of Science. New York, USA: Routledge, 420 p., Salmon 1984SAlmon WC. 1984. Scientific Explanation and the Causal Structure of the World. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press, 295 p., Van Fraassen 1990Van Fraassen BC. 1990. The Scientific Image. New York, USA: Clarendon Press, 231 p., Strahler 1992Strahler AN. 1992. Understanding Science: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues. Buffalo, USA: Prometheus Books, 409 p., Mahner & Bunge 1997Mahner M & Bunge M. 1997. Foundations of Biophilosophy. New York, USA: Springer, 423 p., Hausman 1998Hausman DM. 1998. Causal Asymmetries. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press, 300 p., Thagard 2004Thagard P. 2004. Rationality and science. In: Mele A & Rawlings P (Eds). Handbook of Rationality. Oxford, United Kindom: Oxford University Press, p. 363-379., Nola & Sankey 2007Nola R & Sankey H. 2007. Theories of Scientific Method: An Introduction. Ithaca, USA: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 392 p., de Regt et al. 2009de Regt HW, Leonelli S & Eigner K. 2009. Focusing on scientific understanding. In: de Regt H, Leonelli S & Eigner K (Eds). Scientific Understanding: Philosophical Perspectives. Pittsburgh, USA: University of Pittsburgh Press, p. 1-17., Hoyningen-Huene 2013Hoyningen-Huene P. 2013. Systematicity: The Nature of Science. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 287 p., Potochnik 2017Potochnik A. 2017. Idealization and the Aims of Science. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press, 288 p., Currie 2018Currie A. 2018. Rock, Bone, and Ruin: An Optimist’s Guide to the Historical Sciences. Cambridge, USA: The MIT Press, 376 p., Anjum & Mumford 2018Anjum RL & Mumford S. 2018. Causation in Science and the Methods of Scientific Discovery. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 295 p.), we regard this as the intent of inferring both specific and phylogenetic hypotheses. While it is common in systematics to claim that the purpose of inferring such hypotheses is to obtain ‘the phylogeny’ for a particular group of organisms, this is something of a misnomer, just as it is erroneous to say one has inferred a ‘molecular phylogeny.’ Inferring explanatory hypotheses that causally account for a set of differentially shared characters (cf. Fitzhugh 2006aFitzhugh K. 2006a. The abduction of phylogenetic hypotheses. Zootaxa. 1145: 1-110., 2008bFitzhugh K. 2010b. Revised systematics of Fabricia oregonica Banse, 1956 (Polychaeta: Sabellidae: Fabriciinae): an example of the need for a uninomial nomenclatural system. Zootaxa 2647: 35-50., 2009Fitzhugh K. 2013. Defining ‘species’, ‘biodiversity’, and ‘conservation’ by their transitive relations. In: Pavlinov IY (Ed). The species problem - Ongoing Problems. New York, USA: In Tech, p. 93-130., 2012Fitzhugh K. 2015. What are species? Or, on asking the wrong question. The Festivus 47: 229-239., 2013Fitzhugh K. 2016b. Dispelling five myths about hypothesis testing in biological systematics. Org Divers Evol 16: 443-465. Doi: 10.1007/s13127-016-0274-6., 2016a-cFitzhugh K. 2016c. Ernst Mayr, causal understanding, and systematics: An example using sabelliform polychaetes. Invert Biol 135: 302-313. https://doi.org/10.1111/ivb.12133.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ivb.12133...

), implied by cladograms, cannot be equated with being ‘a phylogeny’ much less ‘the phylogeny.’ The term phylogeny incorrectly connotes that one can attain comprehensive explanatory constructs regardless of the number of observations used to infer those constructs. This, along with not acknowledging the requirement of total evidence (Fitzhugh 2006bFitzhugh K. 2006b. The ‘requirement of total evidence’ and its role in phylogenetic systematics. Biol Phil 21: 309-351.), has led to the tendency to only infer phylogenetic hypotheses from sequence data and assume, incorrectly, that those hypotheses extend to other observed characters. This does not work because the reasoning involved in producing explanatory hypotheses only pertains to the characters involved in inferring those hypotheses. Other characters in need of explanation should not be excluded simply out of conformity with uncritical or popular methodological trends.

Computer algorithms for inferring phylogenetic hypotheses are entirely agnostic with regard to what causal mechanisms contribute to fixation of novel characters among individuals in ancestral populations or the nature of population splitting events (Fitzhugh 2016aFitzhugh K. 2016a. Sequence data, phylogenetic inference, and implications of downward causation. Acta Biotheor 64: 133−160. Doi: 10.1007/s10441-016-9277-0.). This does not present problems when explaining morphological characters since at a minimum either natural selection or genetic drifts are possible causes of fixation. When considering sequence data, however, drift can directly explain shared nucleotides or amino acids; but selection does not operate at the level of those molecules since they have no direct emergent properties that manifest fitness differences among individuals. Instead, selection occurs at higher organizational levels and indirectly affects intergenerational occurrences of associated nucleotides and amino acids; a phenomenon known as downward causation (Campbell 1974Campbell DT. 1974. Downward causation in hierarchically organized biological systems. In: Ayala FJ & Dobzhansky T (Eds). Studies in the Philosophy of Biology: Reduction and Related Problems. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press, p. 179-186., Vrba & Eldredge 1984Vrba E & Eldredge N. 1984. Individuals, hierarchies and processes: towards a more complete evolutionary theory. Paleobiology 10: 146-171., Salthe 1985Salthe SN. 1985. Evolving Hierarchical Systems: Their Structure and Representation. New York, USA: Columbia University Press, 331 p., Lloyd 1988Lloyd EA. 1988. The Structure and Confirmation of Evolutionary Theory. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press, 235 p., Ellis 2008Ellis GFR. 2008. On the nature of causation in complex systems. Trans Royal Soc South Afr 63: 69-84., 2012Ellis GFR. 2012. Top-down causation and emergence: some comments on mechanisms. Interface Focus 2: 126-140., 2013, Auletta et al. 2008Auletta G, Ellis GFR & Jaeger L. 2008. Top-down causation by information control: from a philosophical problem to a scientific research programme. J Royal Soc Interface 5: 1159-1172., Jaeger & Calkins 2011Jaeger L & Calkins ER. 2011. Downward causation by information control in micro-organisms. Int Foc 2: 26-41., Ellis et al. 2011Ellis GFR, Noble D & O’Connor T. 2011. Top-down causation: An integrating theme within and across the sciences? Interface Focus 2: 1-3., Laland et al. 2011Laland KN, Sterelny K, Odling-Smee J, Hoppitt W & Uller T. 2011. Cause and effect in biology revisited: is Mayr’s proximate-ultimate dichotomy still useful? Science 334: 1512-1516., Martínez & Moya 2011Martínez M & Moya A. 2011. Natural selection and multi-level causation. PhilosTheory Pract Biol 3: e202., Davies 2012Davies PCW. 2012. The epigenome and top-down causation. Interface Focus 2: 42-48., Okasha 2012Okasha S. 2012. Emergence, hierarchy and top-down causation in evolutionary biology. Interface Focus 2: 49-54., Walker et al. 2012Walker SI, Cisneros L, & Davies PCW. 2012. Evolutionary transitions and top-down causation. Proc Art Life 13: 283-290., Griffiths & Stotz 2013Griffiths P & Stotz K. 2013. Genetics and Philosophy: An Introduction. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 270 p., Martínez & Esposito 2014Martínez M & Esposito M. 2014. Multilevel causation and the extended synthesis. Biol Theory 9: 209-220., Walker 2014Walker SI. 2014. Top-down causation and the rise of information in the emergence of life. Information 5: 424-39. Doi:10.3390/info5030424., Fitzhugh 2016aFitzhugh K. 2016a. Sequence data, phylogenetic inference, and implications of downward causation. Acta Biotheor 64: 133−160. Doi: 10.1007/s10441-016-9277-0., Mundy 2016Mundy NI. 2016. Population genomics fits the bill: genetics of adaptive beak variation in Darwin’s finches. Mol Ecol 25: 5265-5266., Callier 2018Callier V. 2018. Theorists debate how ‘neutral’ evolution really is. Quanta Magazine https://www.quantamagazine.org/neutral-theory-of-evolution-challenged-by-evidence-for-dna-selection-20181108/.

https://www.quantamagazine.org/neutral-t...

, Pouyet et al. 2018Pouyet F, Aeschbacher S, Thiéry A & Excoffier L. 2018. Background selection and biased gene conversion affect more than 95% of the human genome and bias demographic inferences. eLife 7: e36317., Salas 2019Salas A. 2019. The natural selection that shapes our genomes. Forensic Science International: Genetics 39: 57-60., Yu et al. 2020YU L, Boström C, Franzenburg S, Bayer T, Dagan T & Reusch TBH. 2020. Somatic genetic drift and multilevel selection in a clonal seagrass. Nat Ecol Evol 4: 952-962. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1196-4.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1196-...

). While it would be unrealistic to explain all sequence data by way of drift, invoking selection first requires associating those sequence data to be explained, via downward causation, with morphological characters upon which selection has been hypothesized as operative. If such an association is available, then those relevant sequence data would be excluded from the data matrix used to infer phylogenetic hypotheses, since those characters already would be accounted for via downward causation by the morphological characters. In the absence of evidence for discriminating sequence data to be explained by drift or downward causation, the only viable option is to acknowledge that those data should be excluded from phylogenetic inferences. For these reasons, we do not regard the phylogenetic hypotheses presented by Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

to be plausible or provide a basis for concluding that Euclymeninae is paraphyletic.

The second problem related to inferences of phylogenetic hypotheses from sequence data is the popular tactic of considering additional phylogenetic hypotheses of morphological characters through what is called ‘character mapping’ (cf. Fitzhugh 2014Fitzhugh K. 2014. Character mapping and cladogram comparison versus the requirement of total evidence: does it matter for polychaete systematics? Mem Mus Vic 71: 67-78.). For instance, Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

mapped the absence and presence of cephalic and anal plates onto tree topologies they obtained for sequence data, and then proceeded to discuss phylogenetic hypotheses accounting for these characters. Mapping, however, does not lead to results that can be interpreted as legitimate explanatory hypotheses. The reason is because the act of ‘optimizing’ characters on a previously inferred tree topology, i.e. a set of explanatory hypotheses for a set of characters used to infer those hypotheses, is not an action that can be interpreted as an epistemically meaningful inference. Inferring phylogenetic hypotheses involves a form of non-deductive reasoning known as abduction (Peirce 1931Peirce CS. 1931. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volume 1, Principles of Philosophy. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P & Burks A. (Eds). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 393 p., 1932Peirce CS. 1932. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volume 2, Elements of Logic. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P & Burks A (Eds). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 535 p., 1933a-bPeirce CS. 1933a. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volume 3, Exact Logic. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P & Burks A (Eds). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 433 p., 1934Peirce CS. 1933b. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volume 4, The Simplest Mathematics. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P & Burks A (Eds). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 601 p., 1935Peirce CS. 1934. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volume 5, Pragmatism and Pragmaticism. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P & Burks A (Eds).Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 455 p., 1958a-bPeirce CS. 1935. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volume 6, Scientific Metaphysics. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P & Burks A (Eds). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 462 p., Hanson 1958Hanson NR. 1958. Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 241 p., Fann 1970FANN KT. 1970. Peirce’s Theory of Abduction. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 62 p., Reilly 1970Reilly FE. 1970. Charles Peirce’s Theory of Scientific Method. New York, USA: Fordham University Press, 200 p., Thagard 1988Thagard P. 1988. Computational Philosophy of Science. Cambridge, USA: MIT Press, 257 p., Josephson & Josephson 1994Josephson JR & Josephson SG. 1994. Abductive Inference: Computation, Philosophy, Technology. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 306 p., Magnani 2001Magnani L. 2001. Abduction, Reason, and Science: Processes of Discovery and Explanation. New York, USA: Kluwer Academic, 205 p., 2009Magnani L. 2009. Abductive Cognition: The Epistemological and Eco-cognitive Dimensions of Hypothetical Reasoning. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 549 p., 2017Magnani L. 2017. The Abductive Structure of Scientific Creativity: An Essay on the Ecology of Cognition. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 230 p., Psillos 2002Psillos S. 2002. Simply the best: a case for abduction. In: Kakas AC & Sadri F (Eds). Computational Logic: Logic Programming and Beyond. New York, USA: Springer, p. 605-625., 2011Psillos S. 2011. An explorer upon untrodden ground: Peirce on abduction. In: Gabbay D, Hartmann S & Woods J (Eds). The Handbook of the History of Logic, Volume 10, Inductive Logic. Oxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier Press, p. 117-151., Walton 2004Walton D. 2004. Abductive Reasoning. Tuscaloosa, USA: The University of Alabama Press, 304 p., Gabbay & Woods 2005Gabbay DM & Woods J. 2005. The Reach of Abduction: Insight and Trial. A Practical Logic of Cognitive Systems, Volume 2. Amsterdam, Netherland: Elsevier, 476 p., Aliseda 2006Aliseda A. 2006. Abductive Reasoning: Logical Investigations into Discovery and Explanation. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer, 225 p., Schurz 2008Schurz G. 2008. Patterns of abduction. Synthese 164: 201-234., Park 2017PARK W. 2017. Abduction in Context: The Conjectural Dynamics of Scientific Reasoning. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 268 p., for considerations of abduction in relation to systematics see Fitzhugh 2006aFitzhugh K. 2006a. The abduction of phylogenetic hypotheses. Zootaxa. 1145: 1-110.-2006b, 2008, 2009, 2010a, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016a-b). At a minimum, the premises of an abductive inference involve the conjunction of some causal theory(ies) and effect(s) to be explained. The conclusion is an explanatory hypothesis stating past causal conditions accounting for observed effects. Phylogenetics computer algorithms serve as surrogates for human abductive reasoning, albeit under incorrect monikers such as ‘parsimony,’ ‘maximum likelihood,’ and ‘Bayesian’ (Fitzhugh 2012Fitzhugh K. 2012. The limits of understanding in biological systematics. Zootaxa 3435: 40-67., 2016a). Character mapping is not a form of abductive reasoning since the premises of such an ‘inference’ would only include a previously inferred tree topology and subsequent characters to be explained. In the absence of any actual or implied evolutionary theory(ies) involved in the inference, or the inclusion of all observed characters as part of the premises, per the requirement of total evidence, the conclusion of mapped characters cannot be interpreted as indicating past causal conditions. As such, the evolutionary considerations of cephalic and anal plates by Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

cannot be regarded as epistemically sound.

With the foregoing overview, the synapomorphies for Euclymeninae called into question by Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

can be reviewed. Regarding nuchal grooves, members of species of Maldanella, including M. harai Izuka, 1902, have straight and parallel nuchal groves according to Detinova (1982, p. 66, Fig. 2a-d). Interestingly, one specimen of M. harai described and illustrated from Japanese waters by Imajima & Shiraki (1982, p. 55, Fig. 25b) had strongly curved nuchal grooves, in contrast to the description and illustration of Detinova (1982)DETINOVA NN. 1982. A new abyssal genus and species of polychaetes (Maldanidae). Zool Zhur 61(2): 295-297.. Members of species of Clymenella, including C. complanata Hartman, 1969, have straight, parallel nuchal grooves. A specimen of C. complanata reported from Japan presented short and curved nuchal grooves (Imajima & Shiraki 1982Imajima M & Shiraki Y. 1982. Maldanidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from Japan. Part 1. Bul Nat Scie Mus Tokyo, Ser. A Zool 8: 7-40., p. 48, Fig. 20b), contradicting the original description of Hartman (1969, p. 435, Fig. 2). For both cited species, we suggest they are new species, but only with examinations of material we can confirm this opinion.

Straight, parallel nuchal grooves have been illustrated with details for all Euclymeninae in several important systematics papers in the literature on Maldanidae (Pilgrim 1977Pilgrim M. 1977. The functional morphology and possible taxonomic significance of the parapodia of the maldanid polychaetes Clymenella torquata and Euclymene oerstedi. J Morph 152: 281-302., Arwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308., Fauvel 1927FAUVEL P. 1927. Polychètes sédentaires. Addenda aux errantes, Archiannélides, Myzostomaires. Faune de France vol. 16. Paris, France: Librairie de la Facult des Sciences Paul: Lechevalier, 494 p., Day 1967DAY JH. 1967. A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part2. Sedentaria. London, United Kingdom: British Museum National History Publications, p. 459-842., Fauchald 1977Fauchald K. 1977. The polychaete worms. Definitions and keys to the orders, families and genera. Nat Hist Mus Los Angeles Coun Sci Ser 28: 1-188., Imajima & Shiraki 1982Imajima M & Shiraki Y. 1982. Maldanidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from Japan. Part 1. Bul Nat Scie Mus Tokyo, Ser. A Zool 8: 7-40., Lee & Paik 1986Lee JH & Paik EI. 1986. Polychaetous annelids from the Yellow Sea: III. Family Maldanidae (Part 1). Oce Res 8: 13-25., Salazar-Vallejo 1991Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1991. Revisión de algunos eucliméninos (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) del Golfo de California, Florida, Panamá y Estrecho de Magallanes. Rev Biol Trop 39: 269-278., Jiménez-Cueto & Salazar-Vallejo 1997Jiménez-Cueto MS & Salazar-Vallejo SI. 1997. Maldánidos (Polychaeta) del Caribe Mexicano con una clave para las especies del Gran Caribe. Rev Biol Trop 45: 1459-1480., Mackie & Gobin 1993Mackie ASY & Gobin J. 1993. A review of the genus Johnstonia Quatrefages, 1866 (Polychaeta, Maldanidae), with a description of a new species from Trinidad, West Indies. Zool Scri 22(3): 229-241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.1993.tb00354.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.1993...

, De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

, De Assis et al. 2012De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.) (Table I). Curved or J-shaped nuchal grooves have been found in Rhodininae, Notoproctinae, Maldaninae and Nicomachinae (Arwidsson 1906Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308., Day 1967DAY JH. 1967. A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part2. Sedentaria. London, United Kingdom: British Museum National History Publications, p. 459-842., De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

, De Assis et al. 2012De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.). It is possible that the straight, parallel nuchal grooves had reverted in punctual species of Euclymeninae, but it does not seem very clear. The most important here is that straight nuchal grooves arise as a synapomorphy to Euclymeninae.

Subsequent authors (Pilgrim 1977Pilgrim M. 1977. The functional morphology and possible taxonomic significance of the parapodia of the maldanid polychaetes Clymenella torquata and Euclymene oerstedi. J Morph 152: 281-302., Hausen & Bleidorn 2006Hausen H & Bleidorn C. 2006. Significance of chaetal arrangement for maldanids systematics (Annelida: Maldanidae). Sci Mar 70: 75-79., Tilic et al. 2015Tilic E, von Döhren J, Quast B, Beckers P & Bartolomaeus T. 2015. Phylogenetic significance of chaetal arrangement and chaetogenesis in Maldanidae (Annelida). Zoomorphology 134: 383-401. doi:10.1007/s00435-015-0272-9.), dealing with ontogeny and morphology, presented more detailed characters for Euclymeninae: 1) a double row of notochaetae parallel to the antero-posterior body axis from chaetiger 13 onwards, and 2) a straight chaetal sac visible from chaetiger 13 in adults, in contrast to an involute chaetal sac. A transverse notopodial double row of chaetae represents the primary condition in Maldanidae (Tilic et al. 2015Tilic E, von Döhren J, Quast B, Beckers P & Bartolomaeus T. 2015. Phylogenetic significance of chaetal arrangement and chaetogenesis in Maldanidae (Annelida). Zoomorphology 134: 383-401. doi:10.1007/s00435-015-0272-9.). The stepwise transition between both conditions can always be seen in chaetigers 11 and 12 (Tilic et al. 2015Tilic E, von Döhren J, Quast B, Beckers P & Bartolomaeus T. 2015. Phylogenetic significance of chaetal arrangement and chaetogenesis in Maldanidae (Annelida). Zoomorphology 134: 383-401. doi:10.1007/s00435-015-0272-9., De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

).

The presence of a callus ring preceding the anal funnel is a unique character among members of Euclymeninae (Garwood 2007Garwood PR. 2007. Family Maldanidae - A guide to species in waters around the British Isles. NMBAQC 2006 taxonomic workshop, Dove Marine Laboratory. Available in http://www.nmbaqcs.org/scheme-components/invertebrates/literature-and-taxonomic-keys.aspx.

http://www.nmbaqcs.org/scheme-components...

). This character was not discussed by Kobayashi et al. (2018)Kobayashi G, Goto R, Takano T & Kojima S. 2018. Molecular phylogeny of Maldanidae (Annelida): multiple losses of tube-capping plates and evolutionary shifts in habitat depth. Mol Phylogen Evol 127: 332-344. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.036.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04....

.

The presence of a terminal anus, enclosed within an anal funnel, and covered by a plate, is a unique character for Euclymeninae and Nicomachinae (Fauvel 1927FAUVEL P. 1927. Polychètes sédentaires. Addenda aux errantes, Archiannélides, Myzostomaires. Faune de France vol. 16. Paris, France: Librairie de la Facult des Sciences Paul: Lechevalier, 494 p., Fachauld 1977 Day 1967DAY JH. 1967. A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part2. Sedentaria. London, United Kingdom: British Museum National History Publications, p. 459-842., Imajima & Shiraki 1982Imajima M & Shiraki Y. 1982. Maldanidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from Japan. Part 1. Bul Nat Scie Mus Tokyo, Ser. A Zool 8: 7-40., De Assis & Christoffersen 2011De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.60...

, De Assis et al. 2012De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.). Whether Nicomachinae may represent a taxon included within Euclymeninae, as suggested by Kobayshi et al. (2018), needs to be more thoroughly investigated. Although a cephalic plate has been lost among members of Nicomachinae and some Leiochone, the anal plate is a synapomorphy for the clade Notoproctinae + Maldaninae + Euclymeninae + Nicomachinae.

In summary, straight, parallel nuchal organs, double rows of notochaetae parallel to the antero-posterior body axis from chaetiger 13 onwards, chaetal sacs visible from chaetiger 13 in adults, a callus ring preceding the anal funnel, and the anus on an anal plate that is sunk into the anal funnel, are all characters that support the monophyly of Euclymeninae. A more extensive future phylogenetic analysis of Maldanidae will consider those characters establishing monophyly of the remaining subfamilies.

Comment on the status of the taxon ‘Maldanoplaca’

In their phylogenetic study of Maldanidae, De Assis & Christoffersen (2011De Assis JE, Bleidorn C & Christoffersen ML. 2012. Maldanidae Malmgren, 1867. In: Hrsg V, Beutel RG, Glaubrecht M, Kristensen NP, Prendini L, Purschke G, Richter S, Westheide W & Leschen R (Eds). Annelida. 1ed. Berlin, Germany: Osnabrück De Gruyter, p. 184-199.: Table 3, Fig. 7) introduced the unranked name Maldanoplaca for the clade, (Notoproctinae (Maldaninae (Nicomachinae, Euclymeninae))). Unfortunately, this name was not accompanied by a definition as required by Article 13.1.1 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature 1999INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE. 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. London: The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature.). As such, the name Maldanoplaca can only be regarded as an informal placeholder for the phylogenetic hypotheses accounting for characters associated with that clade. We therefore suggest that the name ‘Maldanoplaca’ should no longer be referred to as a formal taxon name. As such, the name can be ignored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We heartily thank Dr. Carmen Alonso for her dedication in preserving zoological specimens in the Laboratório de Invertebrados Paulo Young (LIPY), and for the sampling of material. We acknowledge Dr Martin Schwentner, from the Center of Natural History, Universität Hamburg - Zoologisches Museum, for sending us the photo of material from the Museum. We acknowledge Karen Green for valuable suggestions on the manuscript. We thank CNPq for a productivity grant to M.L. Christoffersen, and FACEPE Fundação de Amparo a Ciência e Tecnologia de Pernambuco for a post-doctoral scholarship to J.E. De Assis (DCR-0086–2.04/13).

REFERENCES

- Aguado MT, Glasby CJ, Schroeder PC, Weigert A & Bleidorn C. 2015. The making of a branching annelid: an analysis of complete mitochondrial genome and ribosomal data of Ramisyllis multicaudata. Nat Sci Rep 5: 12072. doi: 10.1038/srep12072.

- Aliseda A. 2006. Abductive Reasoning: Logical Investigations into Discovery and Explanation. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer, 225 p.

- Alves PR, Halanych KM & Santos CSG. 2020. The phylogeny of Nereididae (Annelida) based on mitochondrial genomes. Zool Scr 49: 366-378. https://doi.org/10.1111/zsc.12413.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/zsc.12413 - Amaral ACZ, Nallin SAH, Steiner TM, Forroni TO & Gomes DF. 2013. Catálogo das espécies de Annelida Polychaeta do Brasil. http://www.ib.unicamp.br/museu_zoologia/files/lab_museu_zoologia/Catalogo_Polychaeta_Amaral_et_al_2012.pdf (accessed in Jan 2019).

» http://www.ib.unicamp.br/museu_zoologia/files/lab_museu_zoologia/Catalogo_Polychaeta_Amaral_et_al_2012.pdf (accessed in Jan - ANNEKOVA NP. 1937. Polychaete fauna of the northern part of the Japan Sea (in Russian, with English translation of new species text only). Issl fauny morei, Zool Inst Aka Nauk USSR Exp Mers de l’URSS 23: 139-216.

- Anjum RL & Mumford S. 2018. Causation in Science and the Methods of Scientific Discovery. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 295 p.

- Arwidsson I. 1906. Studien über die Skandinavischen und Arktischen Maldaniden nebst zusammenstellung der brigen bisher bekannten Arten dieser Familie. Zool Jahr Supp 9: 1-308.

- Augener H. 1918. Polychaeta. Beit Kennt Meeresfauna Westaf 2(2): 67-625.

- Augener H. 1923. Papers from Dr. Th. Mortensen’s Pacific Expedition 1914-16. XIV. Polychaeta I. Polychaeten von den Auckland-und Campbell-Inseln. Vidensk Meddel Naturhist Foren Köbenhavn 75: 1-115.

- Augener H. 1926. Papers from Dr. Th. Mortensen’s Pacific Expedition 1914-16. XXXIV. Polychaeta III. Polychaeten von Neuseeland. II. Sedentaria. Vidensk Meddel Naturhist Foren Köbenhavn 81: 157-294.

- Auletta G, Ellis GFR & Jaeger L. 2008. Top-down causation by information control: from a philosophical problem to a scientific research programme. J Royal Soc Interface 5: 1159-1172.

- Bellan G. 2001. Polychaeta. In: Costello MJ, Emblow C & White RJ (Eds). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, Paris, p. 214-231.

- Borda E, Kudenov JD, Bienhold C & Rouse GW. 2012. Towards a revised Amphinomidae (Annelida, Amphinomida): description and affinities of a new genus and species from the Nile Deep-sea Fan, Mediterranean Sea. Zool Scr 41:307-325. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00529.x.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00529.x - Brunel P, Bosse L & Lamarche G. 1998. Catalogue of the marine invertebrates of the estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. Can Spec Publ Fish Aquat Sci 126: 1-405.

- Buzhinskaja GN. 1995. Aclymeme gesae, new genus and species of Euclymeninae (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) from the Sea of Japan. Mitt Hamb Zoolog Mus Instit 92: 145-148.

- Callier V. 2018. Theorists debate how ‘neutral’ evolution really is. Quanta Magazine https://www.quantamagazine.org/neutral-theory-of-evolution-challenged-by-evidence-for-dna-selection-20181108/

» https://www.quantamagazine.org/neutral-theory-of-evolution-challenged-by-evidence-for-dna-selection-20181108/ - Campbell DT. 1974. Downward causation in hierarchically organized biological systems. In: Ayala FJ & Dobzhansky T (Eds). Studies in the Philosophy of Biology: Reduction and Related Problems. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press, p. 179-186.

- Chamberlin RV 1919. Pacific coast Polychaeta collected by Alexander Agassiz. Bull Mus Comp Zool, Harvard 63: 251-270.

- Claparède É. 1869. Les Annélides Chétopodes du Golfe de Naples. Seconde partie. Ordre II-ème. Annélides Sédentaires (Aud. et Edw). Mém Soc Phys Hist Nat Genève 20(1): 1-225.

- Currie A. 2018. Rock, Bone, and Ruin: An Optimist’s Guide to the Historical Sciences. Cambridge, USA: The MIT Press, 376 p.

- Davies PCW. 2012. The epigenome and top-down causation. Interface Focus 2: 42-48.

- Day JH. 1955. The Polychaeta of South Africa. Part 3. Sedentary species from Cape shores and estuaries. J Linn Soc London, Zool 42: 407-452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1955.tb02216.x.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1955.tb02216.x - Day JH. 1957. The Polychaete Fauna of South Africa. Part 4. New species and records from Natal and Moçambique. Ann Natal Mus 14(1): 59-129.

- DAY JH. 1967. A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part2. Sedentaria. London, United Kingdom: British Museum National History Publications, p. 459-842.

- De Assis JE, Alonso C, Brito RJ, Santos AS & Christoffersen ML 2012. Polychaetous annelids from the coast of Paraìba State, Brazil. Rev Nord Biol 21(1): 3-44.

- De Assis JE, Alonso-Samiguel C & Christoffersen ML. 2007. Two new species of Nicomache (Polychaeta: Maldanidae) from the Southwest Atlantic. Zootaxa 1454: 27-37.

- De Assis JE, Bleidorn C & Christoffersen ML. 2012. Maldanidae Malmgren, 1867. In: Hrsg V, Beutel RG, Glaubrecht M, Kristensen NP, Prendini L, Purschke G, Richter S, Westheide W & Leschen R (Eds). Annelida. 1ed. Berlin, Germany: Osnabrück De Gruyter, p. 184-199.

- De Assis JE & Christoffersen ML. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships within Maldanidae (Capitellida: Annelida), based on morphological characters. Syst Biodiver 9: 41-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358.

» https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2011.604358 - de Regt HW, Leonelli S & Eigner K. 2009. Focusing on scientific understanding. In: de Regt H, Leonelli S & Eigner K (Eds). Scientific Understanding: Philosophical Perspectives. Pittsburgh, USA: University of Pittsburgh Press, p. 1-17.

- DETINOVA NN. 1982. A new abyssal genus and species of polychaetes (Maldanidae). Zool Zhur 61(2): 295-297.

- Ehlers E. 1905. Neuseelandischen Anneliden. Abh Kön Ges Wiss Gött, Math–Phys Kl. Neue Folge 3(1): 1-80.

- Eliason A. 1962. Die Polychaeten der Skagerak-Expedition 1933. Zool Bidrag Upps 33: 207-293.

- Ellis GFR. 2008. On the nature of causation in complex systems. Trans Royal Soc South Afr 63: 69-84.

- Ellis GFR. 2012. Top-down causation and emergence: some comments on mechanisms. Interface Focus 2: 126-140.

- Ellis G. 2013. Time to turn cause and effect on their heads. New Sci 2930: 28-29.

- Ellis GFR, Noble D & O’Connor T. 2011. Top-down causation: An integrating theme within and across the sciences? Interface Focus 2: 1-3.

- FANN KT. 1970. Peirce’s Theory of Abduction. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 62 p.

- Fauchald K. 1977. The polychaete worms. Definitions and keys to the orders, families and genera. Nat Hist Mus Los Angeles Coun Sci Ser 28: 1-188.

- Fauchald K & Rouse GW. 1997. Polychaete systematics: past and present. Zool Scr 26: 71-138. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.1997.tb00411.x.