ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Proton pump inhibitors and histamine H2 receptor antagonists are two of the most commonly prescribed drug classes for pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease, but their efficacy is controversial. Many patients are treated with these drugs for atypical manifestations attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, even that causal relation is not proven.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the use of proton pump inhibitors and histamine H2 receptor antagonists in pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease through a systematic review.

METHODS:

A systematic review was performed, using MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases. The search was limited to studies published in English, Portuguese or Spanish. There was no limitation regarding date of publication. Studies were considered eligible if they were randomized-controlled trials, evaluating proton pump inhibitors and/or histamine H2 receptor antagonists for the treatment of pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease. Studies published only as abstracts, studies evaluating only non-clinical outcomes and studies exclusively comparing different doses of the same drug were excluded. Data extraction was performed by independent investigators. The study protocol was registered at PROSPERO platform (CRD42016040156).

RESULTS:

After analyzing 735 retrieved references, 23 studies (1598 randomized patients) were included in the systematic review. Eight studies demonstrated that both proton pump inhibitors and histamine H2 receptor antagonists were effective against typical manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease, and that there was no evidence of benefit in combining the latter to the former or in routinely prescribing long-term maintenance treatments. Three studies evaluated the effect of treatments on children with asthma, and neither proton pump inhibitors nor histamine H2 receptor antagonists proved to be significantly better than placebo. One study compared different combinations of omeprazole, bethanechol and placebo for the treatment of children with cough, and there is no clear definition on the best strategy. Another study demonstrated that omeprazole performed better than ranitidine for the treatment of extraesophageal reflux manifestations. Ten studies failed to demonstrate significant benefits of proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2 receptor antagonists for the treatment of unspecific manifestations attributed to gastroesophageal reflux in infants.

CONCLUSION:

Proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2 receptor antagonists may be used to treat children with gastroesophageal reflux disease, but not to treat asthma or unspecific symptoms.

HEADINGS:

Gastroesophageal reflux; Child; Proton pump inhibitors; Histamine H2 antagonists

RESUMO

CONTEXTO:

Inibidores de bomba de prótons e antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina são duas das mais comumente prescritas classes de medicações para a doença do refluxo gastroesofágico pediátrica, mas sua eficácia é controversa. Muitos pacientes são tratados com essas drogas por manifestações atípicas atribuídas ao refluxo gastroesofágico, mesmo que uma relação causal não esteja comprovada.

OBJETIVO:

Avaliar os inibidores da bomba de prótons e os antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina na doença do refluxo gastroesofágico pediátrica através de uma revisão sistemática.

MÉTODOS:

Realizou-se uma revisão sistemática, utilizando as bases de dados MEDLINE, EMBASE e Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A pesquisa foi limitada a estudos publicados em inglês, português e espanhol. Não houve limitação quanto à data de publicação. Os estudos foram considerados elegíveis se fossem ensaios controlados randomizados que avaliassem inibidores da bomba de prótons e/ou antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina para o tratamento da doença do refluxo gastroesofágico pediátrica. Estudos publicados apenas como resumos, estudos que não avaliassem desfechos clinicamente relevantes e estudos que comparassem exclusivamente diferentes doses do mesmo fármaco foram excluídos. A extração de dados foi realizada por pesquisadores independentes. O protocolo do estudo foi registrado na plataforma PROSPERO (CRD42016040156).

RESULTADOS:

Após a análise das 735 referências identificadas, 23 estudos (1598 pacientes randomizados) foram incluídos na revisão sistemática. Oito estudos demonstraram que tanto os inibidores da bomba de prótons como os antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina eram eficazes contra as manifestações típicas da doença de refluxo gastroesofágico e que não havia evidências de benefício na combinação dessas classes de drogas ou na prescrição rotineira de tratamentos de manutenção de longo prazo. Três estudos avaliaram o efeito dos tratamentos em crianças com asma e, nem os inibidores da bomba de prótons, nem os antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina se mostraram significativamente melhores do que o placebo. Um estudo comparou diferentes combinações de omeprazol, betanecol e placebo para o tratamento de crianças com tosse, e não há uma definição clara sobre a melhor estratégia terapêutica. Outro estudo demonstrou que o omeprazol apresentou melhor desempenho do que a ranitidina para o tratamento de manifestações extraesofágicas da doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. Dez estudos não tiveram sucesso em demonstrar benefícios significativos dos inibidores da bomba de prótons ou dos antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina para o tratamento de manifestações inespecíficas atribuídas ao refluxo gastroesofágico em crianças menores de 1 ano de idade.

CONCLUSÃO:

Inibidores da bomba de prótons ou antagonistas dos receptores H2 da histamina podem ser utilizados para tratar crianças com doença de refluxo gastroesofágico, mas não para tratar asma ou sintomas inespecíficos.

DESCRITORES:

Refluxo gastroesofágico; Criança; Inibidores da bomba de prótons; Antagonistas dos receptores histamínicos H2

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the retrograde passage of gastric contents into the esophagus or extraesophageal regions, while gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) consists of troublesome symptoms and/or complications associated to GER3232. Winter H, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, Gottrand F, Barker PN, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the Treatment of GERD in Infants Ages 1-11 Months. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:14-20.. GER is a physiological process, which is extremely common in infants, but it resolves by 12-15 months of age in more than 98% of cases. On the other hand, GERD is much less frequent22. Argüelles-Martín F, González-Fernández F, Gentles MG, Navarro-Merino M. Sucralfate in the treatment of reflux esophagitis in children - preliminary results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;156 Suppl:S43-7..

Even though the most typical symptoms of GERD are heartburn and regurgitation, many other manifestations are attributed to it, such as excessive crying and irritability among infants or asthma exacerbations. Nevertheless, many authors believe that there is no prove of causal relation between acid reflux and these manifestations1212. Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8.,1414. Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NI, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur J Respir. 1992;5:201-6..

GER does not require medical treatment in most cases. Differently, GERD may need to be medically treated, especially with drugs that inhibit acid secretion, such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine H2 receptor antagonists (HRAs). However, the efficacy of these treatments for many manifestations attributed to pediatric GERD is controversial1212. Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8.. Considering such a controversy, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of two of the most frequently prescribed drug classes for pediatric GERD, i.e., PPIs and HRAs, through a systematic review of literature.

METHODS

In order to evaluate the efficacy of PPIs and HRAs for the treatment of pediatric GERD, we performed a systematic review of randomized-controlled trials. MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials - CENTRAL databases were searched by independent researchers (AZM, GMM, BBF). Databases were last searched in June 2016. The search was limited to studies published as full-texts in English, Portuguese or Spanish. There was no limitation regarding date of publication. The search strategy used for MEDLINE was the following: (((((child OR infant))) AND ((((Histamine H2 Antagonists OR ranitidine OR ranitidine OR cimetidine))) OR ((Proton Pump Inhibitors OR omeprazole OR pantoprazole OR lansoprazole OR esomeprazole OR rabeprazole)))) AND Gastroesophageal Reflux) AND (((randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt] OR randomized controlled trials[mh] OR random allocation[mh] OR double-blind method[mh] OR single-blind method[mh] OR clinical trial[pt] OR clinical trials[mh] OR (“clinical trial”[tw]) OR ((singl*[tw] OR doubl*[tw] OR trebl*[tw] OR tripl*[tw]) AND (mask*[tw] OR blind*[tw])) OR (“latin square”[tw]) OR placebos[mh] OR placebo*[tw] OR random*[tw] OR research design[mh:noexp] OR follow-up studies[mh] OR prospective studies[mh] OR cross-over studies[mh] OR control*[tw] OR prospective*[tw] OR volunteer*[tw]) NOT (animal[mh] NOT human[mh]))). Similar search strategies were used for the other databases. Reference lists of the retrieved studies were searched manually.

Retrieved studies were evaluated on the basis of their titles and abstracts, and those identified as relevant for the systematic review were analyzed on the basis of the full text. Studies were considered eligible if they were randomized-controlled trials, evaluating PPIs and/or HRAs for the treatment of pediatric GERD. Studies were excluded otherwise. Studies published only as abstracts, studies evaluating only non-clinical outcomes and studies exclusively comparing different doses of the same drug were also excluded.

Data extraction was performed by independent investigators (AZM, GMM, BBF). A predefined data collection sheet was used. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Authors were contacted for clarification of their studies whenever necessary. Quality of the evidence was evaluated according to the suggestions of the GRADE Working Group44. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004; 328:1490.. Review Manager 5.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used. The PRISMA statement suggestions were followed1919. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700., and the study protocol was registered at PROSPERO platform (CRD42016040156).

A meta-analysis was planned to be performed if clinical heterogeneity were not excessive among included studies. Nevertheless, considering the widely different treatment strategies, children age groups and outcomes evaluated by the included studies, we felt that a meta-analysis would be improper.

RESULTS

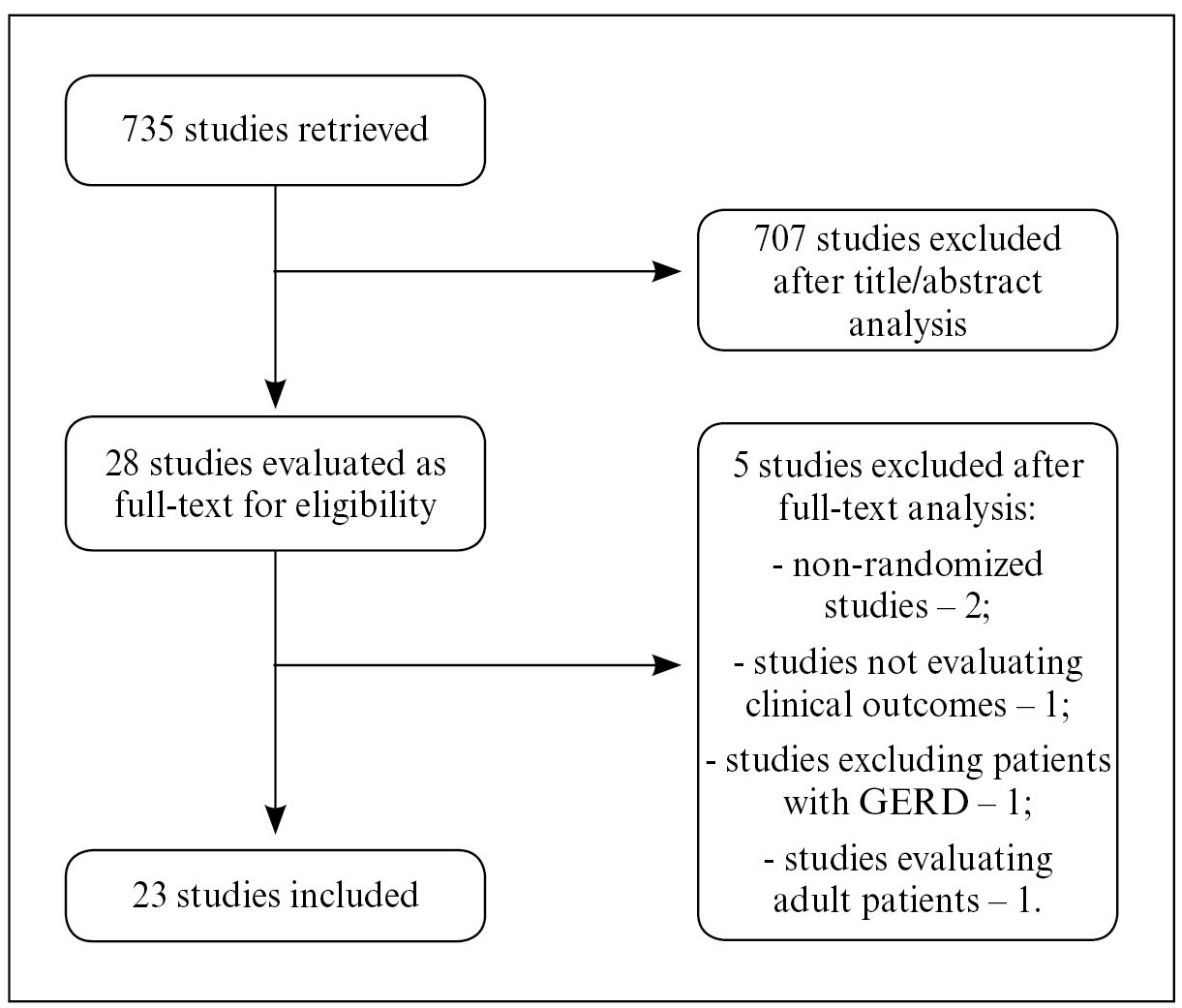

The search strategy retrieved 735 references. After analyzing titles and abstracts, 707 were excluded for being duplicates or for not attending to the eligibility criteria. Twenty-eight references were considered for full-text evaluation, after which five studies were also excluded, two for not being randomized-controlled trials22. Argüelles-Martín F, González-Fernández F, Gentles MG, Navarro-Merino M. Sucralfate in the treatment of reflux esophagitis in children - preliminary results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;156 Suppl:S43-7.,88. Canani RB, Cirillo P, Roggero P, Romano C, Malamisura B, Terrin G, et al. Therapy With Gastric Acidity Inhibitors Increases the Risk of Acute Gastroenteritis and Community - Acquired Pneumonia in Children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e817-20., one for not evaluating clinical outcomes and analyzing a single-dose of the studied treatment2323. Orenstein SR, Blumer JL, Faessel HM, McGuire JA, Fung K, Li BU, et al. Ranitidine, 75 mg, over-the-counter dose: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects in children with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:899-907., one for excluding patients with GERD1818. Jordan B, Heine RG, Meehan M, Catto-Smith AG, Lubitz L. Effect of antireflux medication, placebo and infant mental health intervention on persistent crying: A randomized clinical trial. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:49-58. and one for enrolling adult patients instead of children1515. Hallerbäck B, Glise H, Johansson B, Rosseland AR, Hultén S, Carling L, et al. Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Symptoms-Clinical Findings and Effect of Ranitidine Treatment. Eur J Surg. 1998;583:S6-13.. Finally, 23 studies (1598 randomized patients) were included in this systematic review(1,2,5-7,9-12, 14-17,20-22,24-28,30-33). The flowchart for the search strategy is shown in Figure 1.

Flowchart for the search strategy. The number of retrieved studies is shown, as well as the number of included and excluded studies, with the reason for exclusion.

Included studies were divided in those evaluating children over 1 year of age, those evaluating children under 1 year of age and those evaluating children of all age groups, and their characteristics are shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Regarding risk of bias assessment, despite all studies being randomized-controlled trials, most of them were considered to be of high or unclear risk of bias. There was only one included study which was considered to bear low risk of bias2424. Orenstein SR, Hassall E, Furmaga-Jablonska W, Atkinson S, Raanan M. Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Assessing the Efficacy and Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitor Lansoprazole in Infants with Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J Pediatr. 2009;154:514-20.. Figure 2 shows the risk of bias assessment.

Risk of bias summary. “+”: low risk of bias; “-”: high risk of bias; blank: unclear risk of bias.

Studies evaluating children over 1 year of age

Six studies evaluated exclusively children over one year of age. Gustafsson et al.1414. Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NI, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur J Respir. 1992;5:201-6. compared ranitidine to placebo regarding asthma control. A per protocol analysis failed to verify a significant difference between the study arms concerning asthma symptoms, both in patients with GERD diagnosed by pH monitoring or acid perfusion test and in patients without GERD according to these tests. Spirometric parameters were also similar between groups, both in patients with GERD and in those without pathological GER.

Borreli et al.77. Borrelli O, Rea P, Mesquita MB, Ambrosini A, Mancini V, Di Nardo G, et al. Efficacy of combined administration of an alginate formulation ("gaviscon") and lansoprazole for children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ital J Pediatr. 2002;28:304-309. evaluated children with moderate reflux esophagitis randomized to receive alginate (group A), lansoprazole (group B) or both (group C). In a per protocol analysis, all study groups improved symptoms of GERD related to baseline (P<0.01), and group C reached a lower symptomatic score (3.0, P<0.05) than groups A (4.2) and B (4.3). Similarly, all groups decreased the percentage of esophageal acid exposure related to baseline (P<0.01), and group C also performed better (3.8, P<0.05) than groups A (6.1) and B (5.5).

Stordal et al.2828. Stordal K, Johannesdottir GB, Bentsen BS, Knudsen PK, Carlsen KC, Closs O, et al. Acid suppression does not change respiratory symptoms in children with asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:956-60. compared omeprazole and placebo for children with asthma and GERD in a per protocol analysis. Changes in asthma symptom score were similar between omeprazole and placebo-groups (-1.28 vs -1.28, P=1.00). Changes in forced expiratory volume in the first second were also similar between study arms (-1.38 vs -2.01 for omeprazole and placebo respectively, P=0.77). Regarding changes in use of rescue medication, omeprazole and placebo also performed similarly (-1.9 vs -1.9, P=0.89).

Pfefferkorn et al.2626. Pfefferkorn MD, Croffie JM, Gupta SK, Molleston JP, Eckert GJ, Corkins MR, et al. Nocturnal Acid Breakthrough in Children with Reflux Esophagitis Taking Proton Pump Inhibitors. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:106-5. evaluated children with nocturnal acid breakthrough while using omeprazole. The authors compared associating ranitidine or placebo to omeprazole in a per protocol analysis. There was no significant difference between study arms regarding symptoms (P=0.11), endoscopic findings (P=0.71) and histological findings (P=0.32). On pH monitoring test, 75% of patients of each group remained with nocturnal acid breakthrough despite any of the interventions (P>0.05), which was attributed by the authors to tachyphylaxis.

Boccia et al.66. Boccia G, Manguso F, Miele E, Buonavolontà R, Staiano A. Maintenance Therapy for Erosive Esophagitis in Children After Healing by Omeprazole: Is It Advisable? Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1291-7. studied children with GERD, under endoscopic remission with omeprazole, and evaluated maintenance treatment with omeprazole, ranitidine or no maintenance treatment at all (the study did not use placebo). In an intention-to-treat analysis, there was no significant difference among the three groups regarding endoscopic remission (only one patient, belonging to the control group, did not maintain remission). Similarly, there was no significant difference among groups regarding symptomatic control.

Holbrook et al.1616. Holbrook JT, Wise RA, Gold BD, Blake K, Brown ED, Castro M, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Lansoprazole for Poorly Controlled Asthma in Children: The American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. JAMA. 2012;307:373-81. evaluated children with poorly controlled asthma without clear symptoms of GERD. Lansoprazole was compared to placebo in a per protocol analysis. Regarding changes in Asthma Control Questionnaire, lansoprazole performed similarly to placebo (1.1 vs 1.0, P>0.05). Concerning spirometric parameters, such as forced expiratory volume in the first second, lansoprazole and placebo also performed similarly (2.2L vs 2.3L, P>0.05). On the other hand, patients using lansoprazole had significantly more adverse effects than placebo: upper respiratory infections (63% vs 49%, P=0.02), sore throat (52% vs 39%, P=0.02), bronchitis (7% vs 2%, P=0.04). In this study, 42.6% of patients with interpretable esophageal pH monitoring test had pathologic GER, and study results did not significantly change in this subgroup of patients.

Studies evaluating children under 1 year of age

Ten studies evaluated exclusively children under 1 year of age. Orenstein et al.2525. Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Devandry SN, Liacouras CA, Czinn SJ, Dice JE, et al. Famotidine for infant gastro-oesophageal reflux: a multi-centre, randomized, placebo-controlled, withdrawal trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1097-107. evaluated children with clinical diagnosis of GERD and compared famotidine to placebo in a per protocol analysis. This withdrawal-study had two phases. In the first phase, all patients were randomized to receive two different doses of famotidine. In the second phase, four weeks later, patients were randomized to maintain the active drug, in the same dose used during the first phase of the study, or to change it to placebo. At the end of the study, there was no significant difference among the three groups of patients regarding crying, regurgitation frequency or volume, global assessment and growth. Three patients randomized to receive famotidine 0.5 mg/Kg, two patients randomized to famotidine 1 mg/Kg and three patients randomized to placebo discontinued their treatment due to ineffectiveness. An important limitation of the study was that some patients received a marketed formulation of famotidine irrespective of the randomization because of an interaction between famotidine and the vehicle used to dilute it for the study.

Moore et al.2121. Moore DJ, Tao BS, Lines DR, Hirte C, Heddle ML, Davidson GP. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2003;143:219-23. evaluated children who presented with irritability or excessive crying and who had GERD diagnosed by pH monitoring or by endoscopy with biopsies. The authors of this crossover trial performed a per protocol analysis, comparing omeprazole and placebo. The reflux index improved more among omeprazole users than among placebo users (-8.9% vs -1.9%, P<0.001). Nevertheless, this improvement did not reflect on clinical outcomes, which were similar between omeprazole and placebo users: crying time (191 minutes/day vs 201 minutes/day, P=0.400), visual analogue scale of infant irritability (5.0 vs 5.9, P=0.214).

Omari et al.2222. Omari TI, Haslam RR, Lundborg P, Davidson GP. Effect of Omeprazole on Acid Gastroesophageal Reflux and Gastric Acidity in Preterm Infants With Pathological Acid Reflux. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:41-4. evaluated premature infants with GERD who were not responsive to conservative treatment. They were randomized to receive omeprazole or sterile water as placebo in a crossover study. While using omeprazole, reflux index was greater than 5% in 30% of patients. On the other hand, when receiving sterile water, reflux index was greater than 5% in 80% of cases. The percentage of time with esophageal pH inferior to 4 was 4.9% while using omeprazole and 19.0% while using placebo (P<0.01). On the other hand, there were no statistical differences between omeprazole and placebo regarding symptoms (P>0.05 for all comparisons): number of events of vomiting (6.5 vs 8.5), number of events of apnea (1.0 vs 0.4), number of events of bradycardia (6.5 vs 7.5), number of events of behavioral changes (16.5 vs 17.0). A limitation of the study was that both omeprazole and placebo were diluted in an antacid, which might be considered a confounding factor.

In another study by Orenstein et al.2424. Orenstein SR, Hassall E, Furmaga-Jablonska W, Atkinson S, Raanan M. Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Assessing the Efficacy and Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitor Lansoprazole in Infants with Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J Pediatr. 2009;154:514-20., children with GERD symptoms resistant to conservative treatment were randomized to receive lansoprazole or placebo in an intention-to-treat analysis. The response rate was 54% for both of the groups (P>0.05). Discontinuation of treatment due to inefficacy occurred in 35% of lansoprazole users and in 36% of placebo users (P>0.05). There were also no statistical differences between lansoprazole and placebo regarding symptomatic reduction (P>0.05 for all comparisons): percentage of feedings followed by crying (-20% vs -20%), percentage of feedings followed by regurgitation (-14% vs -11%), percentage of feedings interrupted prematurely (-7% vs -8%), percentage of weekly days with feed refusal (-14% vs -10%), percentage of weekly days with arching back (-20% vs -18%), percentage of weekly days with coughing (0% vs -9%), percentage of weekly days with wheezing (-5% vs -6%), percentage of weekly days with hoarseness (2% vs -5%), improvement of global assessment according to parents (56% vs 51%), improvement of global assessment according to physicians (55% vs 49%). On the other hand, severe adverse effects were more common with lansoprazole (12%) than with placebo (2%, P=0.032).

Winter et al.3333. Winter H, Kum-Nji P, Mahomedy SH, Kierkus J, Hinz M, Li H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pantoprazole Delayed-release Granules for Oral Suspension in a Placebo-controlled Treatment-withdrawal Study in Infants 1-11 Months Old With Symptomatic GERD. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:609-18. studied children with symptomatic GERD in an intention-to-treat analysis, comparing pantoprazole to placebo. In this withdrawal trial, all patients used pantoprazol during four weeks before the double-blind phase, when children were randomized to continue receiving the active drug or to receive placebo during four more weeks. Patients who were non-adherent to treatment during the open phase of the study were excluded. During the double-blind phase, six patients from each group discontinued therapy due to inefficacy (P>0.05). Antacid use was necessary in 39.1% of patients using pantoprazole and in 32.6% of those receiving placebo (P>0.05).

In another withdrawal study by Winter et al.3232. Winter H, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, Gottrand F, Barker PN, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the Treatment of GERD in Infants Ages 1-11 Months. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:14-20., children with symptomatic GERD with good clinical response to esomeprazole in the open-phase of the study were randomized to maintain the active drug or to change it to placebo in an intention-to-treat analysis. Discontinuation of the randomized treatment due to symptom worsening occurred in 38.5% of patients using esomeprazole and in 48.8% of those receiving placebo (hazard ratio of 0.69, P=0.28). Regarding parent-reported symptom severity score, there were no significant differences between esomeprazole and placebo (P>0.05 for all comparisons): vomiting/regurgitation (0.04 vs 0.09), irritability (0.06 vs 0.19), feeding difficulties (0.09 vs 0.10), supraesophageal/respiratory disturbances (0.12 vs 0.03). Concerning physician global symptomatic assessment, symptoms of patients using esomeprazole and placebo were considered, respectively, absent in 10.3% and 4.9%, mild in 51.3% and 48.8%, moderate in 25.6% and 31.7% and severe in 12.8% and 14.6% (P>0.05). In this trial, the use of antacids was allowed, which might have been a confounding factor.

Davidson et al.1212. Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8. evaluated infants who were admitted to neonatal intensive care units or equivalent hospital units and who presented with clinical manifestations of GERD. Esomeprazole and placebo were compared. Authors reported to have performed an intention-to-treat analysis, but one patient was excluded after randomization due to absence of valid efficacy measurements. Regarding changes in total number of signs and symptoms of GERD, there was no significant difference between esomeprazole (-14.7%) and placebo (-14.1%, P=0.92). Concerning only changes in number of gastroenterological signs and symptoms, esomeprazole and placebo also performed similarly (-8.39% vs -10.16%, P=0.4227). On the other hand, esomeprazole performed better than placebo regarding changes in reflux index (-10.70% vs 2.20%, P=0.0017), which led the authors to conclude that symptoms were not related to acid reflux.

Hussain et al.1717. Hussain S, Kierkus J, Hu P, Hoffman D, Lekich R, Sloan S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Delayed Release Rabeprazole in 1- to 11-Month-Old Infants With Symptomatic GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:226-36. evaluated children with symptomatic GERD, resistant to conservative treatment. In an intention-to-treat analysis, authors compared rabeprazole 5 mg/day, rabeprazole 10 mg/day and placebo in a withdrawal study. In the open phase, all patients used rabeprazole and, in the double-blind phase, patients adherent to treatment were randomized to maintain the used dose of the PPI or to change it to placebo. There were no significant differences among groups regarding changes in frequency of regurgitation and regarding gastroesophageal reflux scores.

Loots et al.2020. Loots C, Kritas S, van Wijk M, McCall L, Peeters L, Lewindon P, et al. Body Positioning and Medical Therapy for Infantile Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:237-43. studied children with symptoms associated to GER, diagnosed by pH-impedance test. In a per protocol analysis, authors compared the association of left-side positioning (LSP) to esomeprazole or antacid or that of head of cot elevation (HCE) to one of these drugs. Regarding changes in reflux index, there was no significant difference among groups: LSP and esomeprazole (-4.0%), HCE and esomeprazole (-5.1%), LSP and antacid (-0.9%), HCE and antacid (-2.2%, P>0.05). Concerning changes in total crying time (in minutes), groups also performed similarly: LSP and esomeprazole (-1.0), HCE and esomeprazole (9.0), LSP and antacid (-17.0), HCE and antacid (-8.0, P>0.05). Changes in total number of cough events were also similar among groups: LSP and esomeprazole (4.0), HCE and esomeprazole (2.0), LSP and antacid (2.0), HCE and antacid (11.0, P>0.05). Moreover, changes in total number of vomiting events did not significantly differ among groups: LSP and esomeprazole (-1.0), HCE and esomeprazole (-2.0), LSP and antacid (-3.0), HCE and antacid (0, P>0.05). Among all patients, improvement of symptoms did not relate to improvement of GER (P>0.05). When comparing only esomeprazole to antacid, the former performed better than the latter in decreasing the reflux index (-6.8% vs -0.9, P<0.05), which did not result in significant differences regarding changes in total crying time (4.0 minutes vs -12.0 minutes, P>0.05), in the number of cough events (3.0 vs 6.0, P>0.05) and in the number of vomiting events (-2.0 vs -2.0, P>0.05). A limitation of the study was the small number of patients in each group, which might have led to a type II error.

Azizollahi et al.55. Azizollahi HR, Rafeey M. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitors and H2 blocker in the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants. Korean J Pediatr. 2016;59:226-30. compared omeprazole and ranitidine for the treatment of children with symptomatic GERD, in a per protocol analysis. Both drugs performed similarly regarding GERD symptom score (2.43 vs 2.47, P=0.98).

Studies evaluating children of all age groups

Seven studies evaluated children irrespective of their ages. Cucchiara et al.1111. Cucchiara S, Staiano A, Romaniello G, Capobianco S, Auricchio S. Antacids and cimetidine treatment for gastrooesophageal reflux and peptic oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:842-7. studied children with reflux esophagitis, comparing cimetidine to an antacid in a per protocol analysis. Patients receiving cimetidine were considered cured in 50.00%, improved in 42.00% and stable or worse in 7.15%. Those treated with the antacid, on the other hand, were considered cured in 53.50%, improved in 33.30% and stable or worse in 13.30%. Authors considered that cimetidine did not perform better than the antacid, although they did not inform the p-value of the comparisons.

Arguelles-Martin et al.33. Argüelles-Martin F, Gonzalez-Fernandez F, Gentles MG. Sucralfate versus Cimetidine in the Treatment of Reflux Esophagitis in Children. Am J Med. 1989;86 Suppl:S73-6. evaluated children with reflux esophagitis randomized to receive sucralfate in tablets, sucralfate in suspension or cimetidine in an intention-to-treat analysis. Regarding endoscopic outcomes, patients treated with tablets of sucralfate were considered cured in 56.00%, improved in 28.00% and stable or worse in 16.00%. Those treated with sucralfate suspension were considered cured in 60.00%, improved in 28.00% and stable or worse in 12.00%. Finally, cimetidine users were considered cured in 56.00%, improved in 28.00% and stable or worse in 16.00%. Authors informed that there were no significant differences among groups.

In another study by Cucchiara et al.99. Cucchiara S, Gobio-Casali L, Balli F, Magazzú G, Staiano A, Astolfi R, et al. Cimetidine treatment of reflux esophagitis in children: an Italian multicentric study. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:150-6., children with moderate or severe reflux esophagitis were randomized to be treated with cimetidine or placebo in a per protocol analysis. The cimetidine-group performed better than the placebo-group: cimetidine users were considered cured in 70.60%, improved in 23.50% and stable or worse in 5.88%, while, in placebo users, these figures were 20.00% (P<0.01), 20.00% (P=0.85) and 60.00% (P<0.01) respectively.

In yet another study by Cucchiara et al.1010. Cucchiara S, Minella R, Iervolino C, Franco MT, Campanozzi A, Franceschi M, et al. Omeprazole and high dose ranitidine in the treatment of refractory reflux oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:655-9., children with GERD, diagnosed by pH monitoring or endoscopy, who were unresponsive to ranitidine 8 mg/Kg/day and cisapride were evaluated. Omeprazole 40 mg/day/1.73m2 surface area and ranitidine 20 mg/Kg/day were compared in a per protocol analysis. Symptomatic score was similar between omeprazole- and ranitidine-groups (9.0 vs 9.0, P>0.05). Histological score were also similar among patients using omeprazole or ranitidine (2.0 vs 2.0, P>0.05). Changes in reflux index were also similar among patients on omeprazole and those on ranitidine (61.90% vs 59.60%, P>0.05).

Simeone et al.2727. Simeone D, Caria MC, Miele E, Staiano A. Treatment of childhood peptic esophagitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of nizatidine. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:51-5. evaluated children with mild or moderate reflux esophagitis, comparing nizatidine to placebo in a per protocol analysis. Nizatidine led to endoscopic and histological improvement related to baseline both among children under one year of age and among those over 1 year of age (P<0.05). On the other hand, placebo did not improve significantly endoscopic or histological parameters. The clinical score also improved exclusively among nizatidine users (P<0.01). The only clinical parameter to improve also among placebo users was vomiting (P<0.01). Nizatidine users were considered histologically cured in 75.00%, improved in 16.70% and stable in 8.30%, while placebo users were considered cured in 16.70%, improved in 25.00%, stable in 50.00% and worse in 8.30% (authors did not provide the P-values).

Adamko et al.11. Adamko DJ, Majaesic CM, Skappak C, Jones AB. A pilot trial on the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux-related cough in infants. Transl Pediatr. 2012;1:23-34. studied children with cough and GERD (with abnormal pH monitoring or gastric emptying scan) in a per protocol analysis. Patients were randomized to receive omeprazole and bethanechol, omeprazole and placebo, bethanechol and placebo or double-placebo. The groups presented with reflux indices of 2.80%, 1.30%, 3.40% and 18.10% respectively. The average of daytime coughing episodes was 0.40, 2.40, 3.00 and 3.40 respectively. Respiratory scores were 1.50, 1.50, 1.00 and 3.00 respectively. Authors did not provide the P-values, which might be related to the small number of patients who were enrolled to each group of the study.

Ummarino et al.3030. Ummarino D, Miele E, Masi P, Tramontano A, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y. Impact of antisecretory treatment on respiratory symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Dis Esoph. 2012;25:671-7. evaluated children with GERD diagnosed by impedance and pH monitoring, who presented with extraesophageal symptoms. Omeprazole and ranitidine were compared in an intention-to-treat analysis. Complete symptom remission occurred in 57.90% of omeprazole-group and in 31.20% of ranitidine-group (odds ratio of 3.025, P=0.21). Symptomatic scores were compared between omeprazole- and ranitidine-groups: vomiting (0.21 vs 1.75, P=0.0003), chest pain (0.05 vs 0.56, P=0.01), irritability (0.16 vs 0.25, P=0.6), difficulty swallowing (0 vs 0.94, P=0.2), coughing (0.26 vs 1.69, P=0.0001) and respiratory symptoms (0.79 vs 2.50, P=0.000001).

DISCUSSION

GER is a physiological process, which is more pronounced during the first year of life. GERD, on the other hand, consists of GER with troublesome symptoms or complications and is much less frequent3232. Winter H, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, Gottrand F, Barker PN, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the Treatment of GERD in Infants Ages 1-11 Months. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:14-20.,3333. Winter H, Kum-Nji P, Mahomedy SH, Kierkus J, Hinz M, Li H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pantoprazole Delayed-release Granules for Oral Suspension in a Placebo-controlled Treatment-withdrawal Study in Infants 1-11 Months Old With Symptomatic GERD. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:609-18.. While GERD may require medical treatment, GER does not. However, many manifestations attributed to GERD and treated as such do not have proven causal relation with it, and patients may not experience benefits from the therapy1212. Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8..

This is the most comprehensive systematic review performed to date to evaluate the most important drug classes used for the treatment of pediatric GERD, i.e., PPIs and HRAs. Included studies demonstrated that PPIs seem to be effective for the treatment of pediatric GERD and that the use of HRAs, exclusively or in association to PPIs, does not improve results obtained by the use of PPIs alone. In children with GERD who cannot use PPIs, though, HRAs seem to be a suitable alternative. Long-term maintenance treatments with any of these drug classes are not beneficial for most of the children.

On the other hand, this systematic review showed that there is no evidence of benefits of treating children over one year of age for their asthma symptoms with PPIs or HRAs. Moreover, in children under one year of age, despite the fact that PPIs are effective in increasing esophageal pH, there is no evidence that PPIs or HRAs improve unspecific symptoms, such as irritability, crying, vomiting, regurgitation, apneas, bradycardia or choking. In these patients, treatment with PPIs could be considered in the presence of documented reflux esophagitis.

Regarding treatment of older children with GERD, the results of the present study are in accordance with those of the systematic review published by Tighe et al.2929. Tighe M, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Hayen A, Munro A, Beattie RM. Pharmacological treatment of children with gastrooesophageal reflux (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD008550.. On the other hand, the systematic review published by van der Pol et al.3131. Van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, Omari TI, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Efficacy of Proton-Pump Inhibitors in Children With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925-35. suggested that PPIs were as effective as what was used in the respective control groups. Concerning infants, we agree with van der Pol et al.3131. Van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, Omari TI, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Efficacy of Proton-Pump Inhibitors in Children With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925-35. that there is no evidence to support the use of PPIs or HRAs in the treatment of unspecific symptoms, commonly attributed to GER, especially in the absence of documented reflux esophagitis or its complications. On the matter of infants, Tighe et al.2929. Tighe M, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Hayen A, Munro A, Beattie RM. Pharmacological treatment of children with gastrooesophageal reflux (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD008550. considered that the evidence of efficacy of the antisecretory agents was weak. Another systematic review evaluated exclusively the effect of PPIs on crying and irritability in infants and also found no evidence of benefits1313. Gieruszczak-Bialek D, Konarska Z, Skórka A, Vandenplas Y, Szajewska H. No effect of proton pump inhibitors on crying and irritability in infants: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr. 2015;166:767-70..

The lack of evidence of benefits of antisecretory drugs in the treatment of respiratory symptoms of older children and in the treatment of unspecific symptoms of infants may reinforce the hypothesis of absence of causal relation between acid reflux and these manifestations1212. Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8.,1414. Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NI, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur J Respir. 1992;5:201-6.. Even if these manifestations are related to GER, they might be caused by the volume of reflux, rather than by its acidity1212. Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8..

An important clinical and methodological heterogeneity among included studies in this systematic review prevented a meta-analysis. Two previous systematic reviews had already considered inappropriate to quantitatively pool together data of the studies2929. Tighe M, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Hayen A, Munro A, Beattie RM. Pharmacological treatment of children with gastrooesophageal reflux (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD008550.,3131. Van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, Omari TI, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Efficacy of Proton-Pump Inhibitors in Children With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925-35.. Another important limitation of the present study relates to the poor quality of the existing evidence. Many studies did not clearly describe the random sequence generation and the allocation concealment. Moreover, most of the studies performed per protocol analyzes, instead of intention-to-treat analyzes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the available evidence suggests that PPIs are effective in the treatment of children with GERD, and there is no evidence of benefit of combining HRAs to PPIs. HRAs may be prescribed as an alternative to children with GERD who cannot be treated with PPIs. Moreover, there is not enough evidence to support the use of PPIs or HRAs to treat asthma in children over one year of age or to treat unspecific symptoms in infants in the absence of documented reflux esophagitis or its complications. We understand that further well-designed randomized controlled trials on pediatric GERD are in order, especially head-to-head studies comparing PPIs, HRAs and placebo in large samples of patients.

REFERENCES

-

1Adamko DJ, Majaesic CM, Skappak C, Jones AB. A pilot trial on the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux-related cough in infants. Transl Pediatr. 2012;1:23-34.

-

2Argüelles-Martín F, González-Fernández F, Gentles MG, Navarro-Merino M. Sucralfate in the treatment of reflux esophagitis in children - preliminary results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;156 Suppl:S43-7.

-

3Argüelles-Martin F, Gonzalez-Fernandez F, Gentles MG. Sucralfate versus Cimetidine in the Treatment of Reflux Esophagitis in Children. Am J Med. 1989;86 Suppl:S73-6.

-

4Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004; 328:1490.

-

5Azizollahi HR, Rafeey M. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitors and H2 blocker in the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants. Korean J Pediatr. 2016;59:226-30.

-

6Boccia G, Manguso F, Miele E, Buonavolontà R, Staiano A. Maintenance Therapy for Erosive Esophagitis in Children After Healing by Omeprazole: Is It Advisable? Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1291-7.

-

7Borrelli O, Rea P, Mesquita MB, Ambrosini A, Mancini V, Di Nardo G, et al. Efficacy of combined administration of an alginate formulation ("gaviscon") and lansoprazole for children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ital J Pediatr. 2002;28:304-309.

-

8Canani RB, Cirillo P, Roggero P, Romano C, Malamisura B, Terrin G, et al. Therapy With Gastric Acidity Inhibitors Increases the Risk of Acute Gastroenteritis and Community - Acquired Pneumonia in Children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e817-20.

-

9Cucchiara S, Gobio-Casali L, Balli F, Magazzú G, Staiano A, Astolfi R, et al. Cimetidine treatment of reflux esophagitis in children: an Italian multicentric study. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:150-6.

-

10Cucchiara S, Minella R, Iervolino C, Franco MT, Campanozzi A, Franceschi M, et al. Omeprazole and high dose ranitidine in the treatment of refractory reflux oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:655-9.

-

11Cucchiara S, Staiano A, Romaniello G, Capobianco S, Auricchio S. Antacids and cimetidine treatment for gastrooesophageal reflux and peptic oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:842-7.

-

12Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Neonatal Patients. J Pediatr. 2013;163:692-8.

-

13Gieruszczak-Bialek D, Konarska Z, Skórka A, Vandenplas Y, Szajewska H. No effect of proton pump inhibitors on crying and irritability in infants: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr. 2015;166:767-70.

-

14Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NI, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur J Respir. 1992;5:201-6.

-

15Hallerbäck B, Glise H, Johansson B, Rosseland AR, Hultén S, Carling L, et al. Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Symptoms-Clinical Findings and Effect of Ranitidine Treatment. Eur J Surg. 1998;583:S6-13.

-

16Holbrook JT, Wise RA, Gold BD, Blake K, Brown ED, Castro M, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Lansoprazole for Poorly Controlled Asthma in Children: The American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. JAMA. 2012;307:373-81.

-

17Hussain S, Kierkus J, Hu P, Hoffman D, Lekich R, Sloan S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Delayed Release Rabeprazole in 1- to 11-Month-Old Infants With Symptomatic GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:226-36.

-

18Jordan B, Heine RG, Meehan M, Catto-Smith AG, Lubitz L. Effect of antireflux medication, placebo and infant mental health intervention on persistent crying: A randomized clinical trial. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:49-58.

-

19Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

-

20Loots C, Kritas S, van Wijk M, McCall L, Peeters L, Lewindon P, et al. Body Positioning and Medical Therapy for Infantile Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:237-43.

-

21Moore DJ, Tao BS, Lines DR, Hirte C, Heddle ML, Davidson GP. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2003;143:219-23.

-

22Omari TI, Haslam RR, Lundborg P, Davidson GP. Effect of Omeprazole on Acid Gastroesophageal Reflux and Gastric Acidity in Preterm Infants With Pathological Acid Reflux. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:41-4.

-

23Orenstein SR, Blumer JL, Faessel HM, McGuire JA, Fung K, Li BU, et al. Ranitidine, 75 mg, over-the-counter dose: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects in children with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:899-907.

-

24Orenstein SR, Hassall E, Furmaga-Jablonska W, Atkinson S, Raanan M. Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Assessing the Efficacy and Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitor Lansoprazole in Infants with Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J Pediatr. 2009;154:514-20.

-

25Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Devandry SN, Liacouras CA, Czinn SJ, Dice JE, et al. Famotidine for infant gastro-oesophageal reflux: a multi-centre, randomized, placebo-controlled, withdrawal trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1097-107.

-

26Pfefferkorn MD, Croffie JM, Gupta SK, Molleston JP, Eckert GJ, Corkins MR, et al. Nocturnal Acid Breakthrough in Children with Reflux Esophagitis Taking Proton Pump Inhibitors. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:106-5.

-

27Simeone D, Caria MC, Miele E, Staiano A. Treatment of childhood peptic esophagitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of nizatidine. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:51-5.

-

28Stordal K, Johannesdottir GB, Bentsen BS, Knudsen PK, Carlsen KC, Closs O, et al. Acid suppression does not change respiratory symptoms in children with asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:956-60.

-

29Tighe M, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Hayen A, Munro A, Beattie RM. Pharmacological treatment of children with gastrooesophageal reflux (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD008550.

-

30Ummarino D, Miele E, Masi P, Tramontano A, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y. Impact of antisecretory treatment on respiratory symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Dis Esoph. 2012;25:671-7.

-

31Van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, Omari TI, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Efficacy of Proton-Pump Inhibitors in Children With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925-35.

-

32Winter H, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, Gottrand F, Barker PN, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the Treatment of GERD in Infants Ages 1-11 Months. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:14-20.

-

33Winter H, Kum-Nji P, Mahomedy SH, Kierkus J, Hinz M, Li H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pantoprazole Delayed-release Granules for Oral Suspension in a Placebo-controlled Treatment-withdrawal Study in Infants 1-11 Months Old With Symptomatic GERD. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:609-18.

-

1

Study performed at: Municipal Health Department of Porto Alegre and at the Gastroenterology Unit of Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul.

-

3

Disclosure of funding: no funding received

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

21 Sept 2017 -

Date of issue

2017

History

-

Received

15 Apr 2017 -

Accepted

24 May 2017