Abstracts

OBJECTIVE: To identify risk factors for neonatal mortality, focusing on factors related to assistance care during the prenatal period, childbirth, and maternal reproductive history. METHODS: This was a case-control study conducted in Maceió, Northeastern Brazil. The sample consisted of 136 cases and 272 controls selected from official Brazilian databases. The cases consisted of all infants who died before 28 days of life, selected from the Mortality Information System, and the controls were survivors during this period, selected from the Information System on Live Births, by random drawing among children born on the same date of the case. Household interviews were conducted with mothers. RESULTS: The logistic regression analysis identified the following as determining factors for death in the neonatal period: mothers with a history of previous children who died in the first year of life (OR = 3.08), hospitalization during pregnancy (OR = 2.48), inadequate prenatal care (OR = 2.49), lack of ultrasound examination during prenatal care (OR = 3.89), transfer of the newborn to another unit after birth (OR = 5.06), admittance of the newborn at the ICU (OR = 5.00), and low birth weight (OR = 2.57). Among the socioeconomic conditions, there was a greater chance for neonatal mortality in homes with fewer residents (OR = 1.73) and with no children younger than five years (OR = 10.10). CONCLUSION: Several factors that were associated with neonatal mortality in this study may be due to inadequate care during the prenatal period and childbirth, and inadequate newborn care, all of which can be modified.

Maternal-child health; Neonatal mortality; Risk factors; Case-control studies

OBJETIVO: Identificar fatores de risco para mortalidade neonatal, com especial atenção aos fatores assistenciais relacionados com os cuidados durante o período pré-natal, parto e história reprodutiva materna. MÉTODOS: Trata-se de um estudo caso-controle realizado em Maceió, Nordeste do Brasil. A amostra consistiu de 136 casos e 272 controles selecionados em bancos de dados oficiais brasileiros. Os casos foram todos os recém-nascidos que morreram antes de completar 28 dias de vida, selecionados no Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade, e os controles foram os sobreviventes neste período, selecionados no Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos, por sorteio aleatório entre as crianças nascidas na mesma data do caso. Entrevistas domiciliares foram realizadas com as mães. RESULTADOS: A análise de regressão logística identificou como fatores determinantes para a morte no período neonatal mães com história de filhos anteriores que morreram no primeiro ano de vida (OR = 3,08), o internamento durante a gestação (OR = 2,48), o pré-natal inadequado (OR = 2,49), a não realização de ecografia durante o pré-natal (OR = 3,89), a transferência de recém-nascidos para outra unidade após o nascimento (OR = 5,06), os recém-nascidos internados em UTI (OR = 5,00) e o baixo peso ao nascer (OR = 2,57). Entre as condições socioeconômicas, observou-se uma maior chance para mortalidade neonatal em residências com menor número de moradores (OR = 1,73) e com ausência de filhos menores de cinco anos (OR = 10,10). CONCLUSÕES: Vários fatores que se mostraram associados à mortalidade neonatal neste estudo podem ser decorrentes de assistência inadequada ao pré-natal, ao parto e ao recém-nascido, sendo, portanto, passíveis de serem modificados.

Saúde materno-infantil; Mortalidade neonatal; Fatores de risco; Estudos caso-controle

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Determinants of neonatal death with emphasis on health care during pregnancy, childbirth and reproductive history

Samir B. KassarI,** Corresponding author. E-mail:samirbkr@uol.com.br (S.B. Kassar).; Ana M.C. MeloII; Sônia B. CoutinhoIII; Marilia C. LimaIV; Pedro I.C. LiraV

IPhD in Child and Adolecent Health. Adjunct Professor, Departamento de Pediatria, Universidade Estadual Ciências da Saúde de Alagoas (UNCISAL), Maceió, AL, Brazil

IIMSc in Child and Adolescent Health. Neonatologist, Unidade de Terapia Intensiva Neonatal, Hospital Universitário Prof. Alberto Antunes, Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL), Maceió, AL, Brazil

IIIPhD in Nutrition. Associate Professor, Departamento Materno Infantil, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, PE, Brazil

IVPhD. Adjunct Professor, Departamento Materno Infantil, UFPE, Recife, PE, Brazil

VPhD. Full Professor, Departamento de Nutric¸ão, UFPE, Recife, PE, Brazil

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To identify risk factors for neonatal mortality, focusing on factors related to assistance care during the prenatal period, childbirth, and maternal reproductive history.

METHODS: This was a case-control study conducted in Maceió, Northeastern Brazil. The sample consisted of 136 cases and 272 controls selected from official Brazilian databases. The cases consisted of all infants who died before 28 days of life, selected from the Mortality Information System, and the controls were survivors during this period, selected from the Information System on Live Births, by random drawing among children born on the same date of the case. Household interviews were conducted with mothers.

RESULTS: The logistic regression analysis identified the following as determining factors for death in the neonatal period: mothers with a history of previous children who died in the first year of life (OR = 3.08), hospitalization during pregnancy (OR = 2.48), inadequate prenatal care (OR = 2.49), lack of ultrasound examination during prenatal care (OR = 3.89), transfer of the newborn to another unit after birth (OR = 5.06), admittance of the newborn at the ICU (OR = 5.00), and low birth weight (OR = 2.57). Among the socioeconomic conditions, there was a greater chance for neonatal mortality in homes with fewer residents (OR = 1.73) and with no children younger than five years (OR = 10.10).

CONCLUSION: Several factors that were associated with neonatal mortality in this study may be due to inadequate care during the prenatal period and childbirth, and inadequate newborn care, all of which can be modified.

Keywords: Maternal-child health; Neonatal mortality; Risk factors; Case-control studies

Introduction

Mortality in the neonatal period is an important indicator of maternal and child health, reflecting the socioeconomic and reproductive status, especially those related to prenatal care, childbirth, and newborn care.1-4 In recent years, deaths in the neonatal period ha rely preventable,5,6 but they still present high rates, with a slow decline.1,5,7,8

The state of Alagoas, in Northeastern Brazil, has the second worst Child Development Index (CDI), and is the state with the highest rate of infant mortality in the country; over 60% of these deaths occur in the neonatal period.9 When reviewing death certificates during the neonatal period in Maceió, capital of the state of Alagoas, it was observed that over 75% of these deaths could be prevented by proper care during pregnancy and childbirth.6 Nevertheless, more detailed studies have not been carried out on the risk factors for neonatal death in this capital, where over 90% of the state's high-technology neonatal services are located.

The identification of risk factors associated with neonatal mortality may assist planning for the restructuring and improvement of care for pregnant women and newborns, in order to reduce infant mortality. The reduction of these deaths does not depend on new knowledge, as is the case with other health problems, but on the availability and more effective use of existing scientific and technological knowledge.4

A series of failures in the perinatal care structure has been identified in Brazil.4,10,11 In 2011, the Brazilian Ministry of Health created a care network that guarantees access and effectiveness during the prenatal, childbirth, and the neonatal periods (Rede Cegonha -Stork Network). Such an initiative would be more effective in each region if supported by recent epidemiological research on risk factors of neonatal mortality.

This study aimed to identify these factors, with special attention to assistance care during the prenatal and childbirth period, as well as to the maternal reproductive history in the city of Maceió.

Methods

The study was carried out in Maceió, capital of Alagoas, a poor urban region of Northeast Brazil. This city has an area of 511 km2 and a population of 903,463 inhabitants; 17% of those older than 15 years are illiterate. There are 22,000 births per year. Alagoas is a state with large differences regarding distribution of wealth and has a low Human Development Index (HDI). Among the health indicators, in 2010 infant mortality among residents in Maceió, was 16.1/1,000 live births; 66.4% of these deaths occurred during the neonatal period.12,13

This was a case-control study in which the cases consisted of children born to mothers living in Maceió who died before 28 days of life, whereas the controls were those who survived the neonatal period.

The sample size was calculated by adopting a power of study (1-β) of 80%, an alpha error of 5%, with a ratio of 1:2 (case-control). Minimum rates of 10% exposure to the risk factor among the controls and of 22% among cases were adopted. These values were considered since this was a study in which several exposure factors would be analyzed, and the frequencies of some of them in the population of origin were unknown. The minimum sample size was estimated to be 121 cases and 242 controls.

The cases were selected from the database of the Mortality Information System (MIS) of the Secretariat of Health of Maceió from April of 2007 to March of 2008. During this period, 160 neonatal deaths were recorded. Of this total, 24 cases (15%) did not participate in the research, due to the refusal to be interviewed by two mothers of deceased children, two unidentified charts, and 20 households that were not located during the active search, thus constituting a sample of 136 deaths. The controls consisted of 272 children selected by random drawing from those born on the same date of as case to mothers living in Maceió.

The inclusion criteria defined for the groups cases and controls were mothers of children born alive, living in Maceió, single pregnancies, and weighing over 500 g and/or with gestational age > 22 weeks.

The addresses of the cases were obtained from the MIS, the declarations of live birth from the Municipal Health Secretariat of Maceió, and the hospital records. The names of the mothers for the random draw of controls were obtained from the Live Birth Database. The interviews conducted with mothers of children who died (cases) occurred after a mean time of four months six days after the death; for controls, the mean was four months and seven days of life.

Information on demographic and socioeconomic family characteristics, maternal reproductive history, health status during pregnancy, prenatal and childbirth care, and health of the newborn were obtained for the entire sample through interviews with the mothers during home visits through a form containing closed and pre-coded questions.

Four interviewers who had experience working with research on infant death under one year of age were trained to collect data. Before the study was started, a pilot study was performed to test the understanding of the questions in the questionnaire and to allow the interviewers to become acquainted with it. Weekly meetings to discuss questions that occurred during the interviews were conducted during data collection. Systematic reviews of collected data were also conducted in order to correct consistency errors.

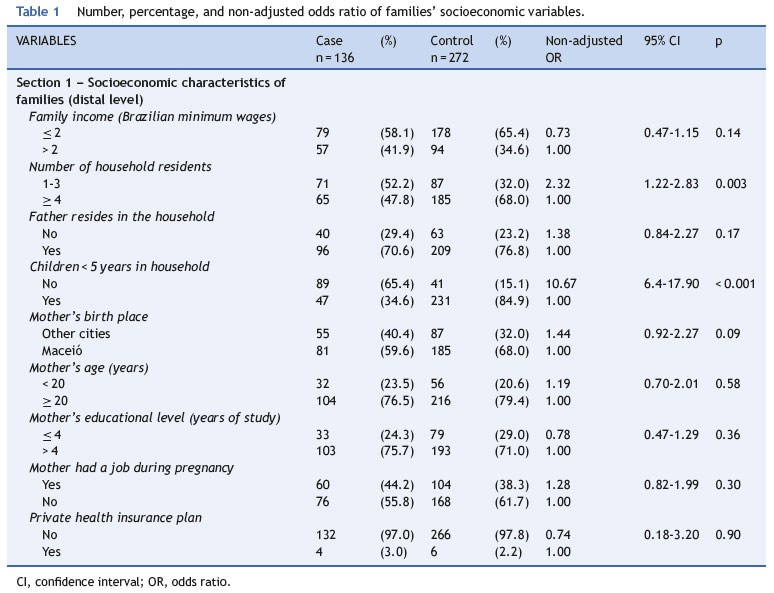

The variables were grouped into five blocks of hierarchical levels, according to their origin in time and relevance to determine the outcome.14 The distal level (Section 1) included the socioeconomic characteristics of families: income in minimum wages, number of household members, whether the father lived in the household, whether there were children under 5 years living in the household, maternal age and birth place, maternal level of education in years of schooling, mother's work outside the home during pregnancy, and whether the family had a private health plan.

The intermediate level I (Section 2) included variables related to the reproductive history of mothers in relation to previous children: occurrence of preterm birth, birth weight < 2,500 g in a previous child, newborn with any health problems, and death of a child during the first year of life.

The intermediate level II (Section 3) included variables related to health status of the mothers during the current pregnancy: risk of miscarriage, hospitalization during the current pregnancy, and bed rest prescribed by a physician.

The intermediate level III (Section 4) included variables related to prenatal care and childbirth. Regarding prenatal care, the following were investigated: adequacy of prenatal care (adequate and inadequate), whether the mother had the option to choose the physician, prenatal care consultations with the same professional, and ultrasound examination. Regarding birth care, the following were included: difficulty in finding available hospital bed on the delivery day, time elapsed between admission and delivery in hours, whether the delivery was performed by the physician who performed the prenatal care, and whether the newborn had to be transferred to another unit after birth.

Prenatal care was considered adequate when the pregnant woman had her first appointment during the first trimester of pregnancy, had at least four consultations during the pregnancy, and had measurements of weight, blood pressure, uterine height, and auscultation of fetal heart rate in all consultations.3,15 The absence of any of the above criteria was characterized as inadequate prenatal care.

The proximal level (Section 5) included factors related to the care and health of newborns: need for hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and birth weight. The variable gestational age was not included due to greater reliability for quality of the variable birth weight and the strong correlation between them.

The data were processed in duplicate and validated using Epi-Info, release 6.04d, to minimize errors. Subsequently, a univariate analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), release 12, to estimate the odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals between the explanatory variables and the outcome. Then a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed, adopting the hierarchical model of variable input, according to a conceptual model previously adopted by the authors. Variables selected for inclusion in the models were those that had a p-value < 0.20 in the univariate analysis. the criterion established for retaining the variable in each hierarchical level was a p-value < 0.20; however, only variables with statistical significance remained in the final model (p < 0.05).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Alagoas on November 1, 2006 (case No.013193/2006-11). An informed consent was obtained from the hospitals and mothers for their participation in the study.

Results

Most neonatal deaths (64%) occurred before 7 days of life, and of those, 41% occurred in the first 24 hours after delivery. Of 408 families interviewed (136 cases and 272 controls), 63% earned up to two Brazilian minimum wages, 72% of mothers had more than four years of study, 22% were adolescents, 20% had difficulty finding an available bed on the day of delivery, and 83% used the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde SUS) and had the delivery performed by the physician on duty.

Tables 1-3 show all studied variables and those that were selected for the multivariate logistic regression analysis with a p-value < 0.20. in table 4, after adjusting for other socioeconomic variables, those that had a higher chance of neonatal death were households with no children under 5 years of age and with fewer than four residents. the variables of sections 2 and 3 that remained significant were mothers with a history of previous deaths of children in the first year of life and hospitalization during pregnancy, respectively. in section 4, the variables inadequate prenatal care, lack of echocardiography, newborn transferred to another health facility, and the longest time between hospitalization and childbirth were significant for the occurrence of death. in section 5, nicu admission and low birth weight remained statistically associated with increased odds of neonatal death.

Discussion

There was a higher concentration of deaths during the first 6 days of life, with more than one-third of deaths on the first day of life. Neonatal deaths in the first 6 days are mainly caused by maternal factors and pregnancy and childbirth complications.6 Studies have confirmed the association of these deaths with poor prenatal care and inadequate care to newborns in the delivery rooms of hospitals.3,16,17

Almost two thirds of the studied families had low income (less than two Brazilian minimum wages per month). The association of low individual socioeconomic status and risk of neonatal death has shown diverse results in analytical studies in Brazilian cities.3,18-24 Family income, maternal education, and age were not shown to be risk factors for neonatal mortality in this study. Similar results were found in studies that used the same method,2,3 possibly because most of the mothers interviewed in this study were SUS users with homogenous household income and level of education between cases and controls. Mortality during the neonatal period is more influenced by the care given to the mother and child during pregnancy and childbirth, whereas mortality in the post-neonatal period is more related to socioeconomic status and, more specifically, to quality of life.10

Families with the lowest number of household members and absence of children under five years of age were associated with a higher chance of neonatal death, a result similar to that found in São Luís (MA), Northeastern Brazil, a city with a similar socioeconomic status to the city of Maceió.25 Mothers who lived with more household members to help with child care and mothers with more experience were the arguments used by the authors to explain this finding.

Neonates whose mothers were hospitalized during pregnancy were more likely to die; previous maternal diseases and complications of pregnancy are specific situations that predispose to hypoxia and perinatal infections. In these circumstances, they require appropriate and effective care, one of the current proposals of the Stork Network.15

The odds of neonatal mortality were higher in the group of mothers with inadequate prenatal care, showing how health care during pregnancy plays an important role in the studied outcome, a result consistent with other studies.2,3,18

In Brazil, the coverage and the mean number of consultations during prenatal care show a growing trend. The assessment of prenatal care quality is not available in many studies in which the outcome is mortality, but there is evidence that poor-quality care is a more serious problem than simply fewer consultations.7,26

Adequate prenatal care has emerged as a key protective factor against low birth weight, prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, and neonatal death.2,15 Good-quality care during the prenatal period can result in a reduction of 10% to 20% of all deaths in the neonatal period.27

The lack of ultrasound examination was also a risk factor, which may serve as a warning, at the admission of pregnant women in labor, that there were limitations in the prenatal care; moreover, the early identification and diagnosis of morphological fetal and placental alterations observed in the ultrasound help to recognize risks and may reduce neonatal mortality.

A large number of births occur in hospitals that are not capable of safely meeting mothers' and newborns' necessities,10,11 and thus the transfer to another unit(sometimes inappropriately performed) indicated a greater chance of death. In this study, over 70% of children who were transferred were born in private maternity hospitals that provide assistance to the SUS (data not shown). This result may indicate risk of stillbirth due to poor-quality care, as well as difficulty in accessing good quality health services. Public hospitals with intensive and intermediate neonatal care units, when compared with private hospitals that have contracts with SUS, present better results in relation to risk of death.4,10,11

A longer period of time between admission and delivery resources, overcrowded hospitals, deficiencies in basic (> 10 hours) influenced the occurrence of neonatal deaths, similar to other study carried out in Northeastern Brazil.3 Although obstetric complications and lack of NICU availability delayed the hospitalization of pregnant women in appropriate units, the factor that most influenced neonatal survival was timely care, showing an unsatisfactory monitoring of labor.

As expected, the studied infants admitted at NICUs were those who had a greater chance of death. However, studies have shown that Brazilian newborns, when admitted at NICU, are more likely to die when compared to those in developed countries with the same problems, suggesting deficiencies in care.4,16,17,28 Fewer resources, overcrowded hospitals, deficiencies in basic care, and lack of trained professionals are the maincauses of this dissimilarity.4,16,17,28 Most deaths of children admitted to the neonatal ICU are related to prenatal care and the delivery;28-30 the use of appropriate resources during this period can reduce deaths by up to Low birth weight is always perceived as a risk factor for 50%.27 neonatal mortality.2,3,6,8 However, 30% of deaths in this study during this period can reduce deaths by up to 50%.27

The high prevalence of controls admitted at the NICUs, but for a period of time < 48 hours is noteworthy. Perhaps the interviewed mothers provided this information despite the fact that their babies remained in the NICU for observation only, as private hospitals and supplemental health services in Maceió do not have beds for intermediate care. There is a shortage of such beds in public hospitals, and newborns who do not need intensive treatment usually occupy beds in the NICU.

Low birth weight is always perceived as a risk factor for neonatal mortality.2,3,6,8 However, 30% of deaths in this study occurred in newborns weighing more than 2,500 g. This finding is a "sentinel" event, suggesting there are problems related to the care provided to pregnant women and their newborns.

The type of study used in this research may be subject to recall bias. Mothers from the case group (deceased children) may be more likely than those from the control group to negatively assess the care received during pregnancy and childbirth, as well as focus more intensely on health problems that occurred during this period. Moreover, for some variables the power of the study may have been unsatisfactory and the results may not reflect the complexity among these variables, or others that were not assessed in relation to the studied out-come.

The factors analyzed in this study corroborate the importance of prevention of high-risk pregnancies, focused on the health care of women of reproductive age and on appropriate assistance during prenatal care, childbirth, and newborn care, all of which are modifiable.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Resolution MCT/CNPq 02/2006 Universal, No. 470477/2006-7.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

To the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), for the financial support of this study, and for the grants to Pedro Lira and Marilia Lima.

References

Received 13 August 2012; accepted 21 November 2012

Available online 28 April 2013

- 1. Rajaratnam JK, Marcus JR, Flaxman AD, Wang H, Levin-Rector A, Dwyer L, et al. Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970-2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4. Lancet. 2010;375:1988-2008.

- 2. Schoeps D, Furquim de Almeida M, Alencar GP, França Jr I, Novaes HM, Franco de Siqueira AA, et al. Risk factors for early neonatal mortality. Rev Saúde Pública. 2007;41:1013-22.

- 3. Nascimento RM, Leite AJ, Almeida NM, Almeida PC, Silva CF. Determinants of neonatal mortality: a case-control study in Fortaleza, Ceará State, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2012;28:559-72.

- 4. de Carvalho M, Gomes MA. A mortalidade do prematuro extremo em nosso meio: realidade e desafios. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2005;81:S111-8.

- 5. Ribeiro VS, Silva AA. Neonatal mortality trends in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil, from 1979 to 1996. Cad Saúde Pública. 2000;16:429-38.

- 6. Pedrosa LD, Sarinho SW, Ordonha MR. Quality of information analysis on basic causes of neonatal deaths recorded in the Mortality Information System: a study in Maceió, Alagoas State, Brazil, 2001-2002. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007;23:2385-95.

- 7. Barros FC, Victora CG. Maternal-child health in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil: major conclusions from comparisons of the 1982, 1993, and 2004 birth cohorts. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24:S461-7.

- 8. Barros FC, Victora CG, Barros AJ, Santos IS, Albernaz E, Matijasevich A, et al. The challenge of reducing neonatal mortality in middle-income countries: findings from three Brazilian birth cohorts in 1982, 1993, and 2004. Lancet. 2005;365:847-54.

-

9United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Situação Mundial da Infância 2009. Saúde Materna e Infantil. Brasília: UNICEF; 2008. 166p.

- 10. Lansky S, França E, Kawachi I. Social inequalities in perinatal mortality in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: the role of hospital care. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:867-73.

- 11. Lansky S, França E, César CC, Monteiro Neto LC, Leal M do C. Perinatal deaths and childbirth healthcare evaluation in maternity hospitals of the Brazilian Unified Health System in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 1999. Cad Saúde Pública. 2006;22:117-30.

- 12. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) [Internet]. Brasília: IBGE [acessado en 30 Mai 2012]. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios (PNAD) 2003 [acessado en 30 Mai 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades

- 13. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Vigilância em Saúde [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde [acessado em 30 Mai 2012]. Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade-SIM [acessado em 30 Mai 2012]. http://www.datasus.gov.br

- 14. Lima Sd, Carvalho ML, Vasconcelos AG. Proposal for a hierarchical framework applied to investigation of risk factors for neonatal mortality. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24:1910-6.

- 15. Serruya SJ, Cecatti JG, Lago Td. The Brazilian Ministry of Health's Program for Humanization of Prenatal and Childbirth Care: preliminary results. Cad Saúde Pública. 2004;20:1281-9.

- 16. Castro EC, Leite AJ. Hospital mortality rates of infants with birth weight less than or equal to 1,500 g in the northeast of Brazil.J Pediatr (Rio J). 2007;83:27-32.

- 17. Barros AJ, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Albernaz EP, Victora CG. Neonatal mortality: description and effect of hospital of birth after risk adjustment. Rev Saúde Pública. 2008;42:1-9.

- 18. Almeida SD, Barros MB. Health care and neonatal mortality. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2004;7:22-35.

- 19. Ribeiro VS, Silva AA, Barbieri MA, Bettiol H, Aragão VM, Coimbra LC, et al. Infant mortality: comparison between two birth cohorts from Southeast and Northeast, Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38:773-9.

- 20. Silva ZP, Almeida MF, Ortiz LP, Alencar GP, Alencar AP, Schoeps D, et al. Maternal and neonatal characteristics and early Determinants of neonatal death and healthcare 277 neonatal mortality in greater metropolitan São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25:1981-9.

- 21. Goldani MZ, Barbieri MA, Bettiol H, Barbieri MR, Tomkins A. Infant mortality rates according to socioeconomic status in a Brazilian city. Rev Saúde Pública. 2001;35:256-61.

- 22. Guimarçães MJ, Marques NM, Melo Filho DA, Szwarcwald Cl. Living conditions and infant mortality: intra-urban differentials in Recife, Pernambuco State, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2003;19:1413-24.

- 23. Hernandez AR, Silva CH, Agranonik M, Quadros FM, Goldani MZ. Analysis of infant mortality trends and risk factors in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, 1996-2008. Cad Saúde Pública. 2011;27:2188-96.

- 24. Ribeiro AM, Guimarães MJ, Lima Mde C, Sarinho SW, Coutinho SB. Risk factors for neonatal mortality among children with low birth weight. Rev Saúde Pública. 2009;43:246-55.

- 25. da Silva AA, Bettiol H, Barbieri MA, Ribeiro VS, Aragão VM, Brito LG, et al. Infant mortality and low birth weight in cities of Northeastern and Southeastern Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2003;37:693-8.

- 26. Neumann NA, Tanaka OY, Victora CG, Cesar JA. Quality and equity in antenatal care and during delivery in Criciúma, Santa Catarina, in Southern Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2003;6:307-18.

- 27. Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L, et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977-88.

- 28. Markestad T, Kaaresen PI, Rønnestad A, Reigstad H, Lossius K, Medbø S, et al. Early death, morbidity, and need of treatment among extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1289-98.

- 29. Ribeiro de Carvalho AB, Jamusse de Brito AS, Matsuo T. Health care and mortality of very-low-birth-weight neonates. Rev Saúde Pública. 2007;41:1003-12.

- 30. Almeida MF, Guinsburg R, Martinez FE, Procianoy RS, Leone CR, Marba ST, et al. Perinatal factors associated with early deaths of preterm infants born in Brazilian Network on Neonatal Research centers. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2008;84:300-7

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

03 July 2013 -

Date of issue

June 2013

History

-

Received

13 Aug 2012 -

Accepted

21 Nov 2012