Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has all features of a wicked problem. It is not only a crisis of intensive care but also a more complex health, social, economic, and humanitarian crisis. Moreover, its risks will continue until mass vaccination is undertaken, hence, the control of contagiousness relies on citizens’ responsible behavior. Strategies to fight COVID-19 in Lombardy, Veneto (Italy) and in Ticino (Switzerland) have shown that a more balanced approach focusing not exclusively on hospitals but also on a territorial basis, pays off. Therefore, a more integrated approach is beneficial from a clinical, social, and economic point of view providing procedures for future emergencies.

Keywords:

COVID-19; territorial medicine; health

Resumo

A pandemia da COVID-19 mostra todas as características de um problema prejudicial. Não se trata somente de uma crise de cuidados intensivos, mas também de uma crise sanitária, social, econômica e humanitária mais complexa. Ademais, seus riscos continuarão até que se leve a cabo uma vacinação massiva pois o controle do contagio depende dela e do comportamento responsável dos cidadãos. As estratégias de luta contra a COVID-19 na Lombardia, Vêneto (Italia) e Ticino (Suíça) têm apontado ser mais frutífero um enfoque mais equilibrado que não se centra exclusivamente nos hospitais senão também no território. Portanto, um enfoque mais integrado traz benefícios do ponto de vista clínico, social e econômico ao mesmo tempo que fornece também a preparação para as futuras emergências.

Palavras-chave:

COVID-19; medicina territorial; saúde

Resumen

La pandemia de COVID-19 muestra todas las características de un grave problema. No se trata sólo de una crisis de cuidados intensivos, sino también de una crisis sanitaria, social, económica y humanitaria más compleja. Además, sus riesgos continuarán hasta que se lleve a cabo una vacunación masiva, de esto depende el control del contagio, y también del comportamiento responsable de los ciudadanos. Las estrategias de lucha contra la COVID-19 en Lombardía, Véneto (Italia) y Tesino (Suiza) han demostrado que es más fructífero un enfoque más equilibrado que no se centre exclusivamente en los hospitales, sino también en el territorio. Por tanto, un enfoque más integrado será beneficioso desde el punto de vista clínico, social y económico, y brindará también preparación para futuras emergencias.

Palabras clave:

COVID-19; medicina territorial; salud

1. INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 is not only an intensive units crisis but also a complex social and humanitarian crisis, therefore, an approach only based on hospitals seems not to be sufficient to completely cope with this crisis. This short article, starting from an analysis on how the COVID-19 pandemic was managed in Italy and Switzerland, aims at finding an inclusive and alternative approach to dealing with COVID-19 by engaging scholars, policy makers and practitioners such as epidemiologists, social psychologists, hygienists, immunologists, health psychologists, crises and communication experts, social scientists, experts in logistics, and social workers beside virologists and to integrate hospital care with territorial medicine, and also activating citizens and their communities. The central thesis is that the hospital-approach employed so far ought to be complemented by the empowerment of communities and area-based systems as the hospital-centric approach has not been able to utterly manage the crisis.

In order to alternatively repond to the COVID-19 crisis, a more balanced approach has been used in some Italian and Switzerland areas (respectively, Veneto and Ticino) with satisfactory results. This approach seems to be not very different from that effectively used in low-income countries to deal with global health problems such as the Ebolavirus disease (EVD). Such a proposal has several clinical, social and economic benefits including capillarity, early detection and greater ownership. However, several conditions need to be present in order to make this approach feasible such as the existence of a well-functioning territorial medicine, trust and social capital. This inclusive approach is applicable to high-income countries characterized by healthcare systems operating beyond maximum capacity and struggling to control the circulation of the virus over a longer term. Finally, it could also improve society preparedness in order to tackle future health emergencies.

2. THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AS A WICKED PROBLEM

A pneumonia of unknown cause was detected in Wuhan, China on 31 December 2019. On 11 February 2020, the WHO announced a name for the new coronavirus disease: COVID-19.is a highly transmittable and potentially fatal coronavirus. It has been noticed that the more medicalized and centralized the society, the more widespread the virus (Nacoti et al., 2020Nacoti, M; Ciocca, A ; Giupponi, A; Brambillasca, P; Lussana, F; … Montaguti, C. (2020, March 21). At the Epicenter of the Covid-19. Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy: Changing Perspectives on Preparation and Mitigation. NEJM Catalyst. Retrieved from https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0080

https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.10...

), therefore, it has been labelled the Ebola of the rich. As the spread of the virus was increasing rapidly on March 30th, 2020, it was officially declared a global pandemic, and at the time of writing, there are 42.512.186 confirmed cases and 1.147.301 deaths1

1

Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/

.

The COVID-19 pandemic displays all the features of a wicked problem (Head, 2008Head, B. W. (2008). Wicked problems in public policy. Public policy, 3(2), 101-118.; Weber & Khademian, 2008Weber, E. P; & Khademian, A. M. (2008). Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public administration review, 68(2), 334-349.). More specifically, its evolution is unstructured as precise causes and effects are difficult to identify and continuously evolving, making unanticipated consequences of policy actions very likely (Agranoff, 2003Agranoff, R. (2003). Leveraging networks: A guide for public managers working across organizations. Washington, DC: IBM Endowment for the Business of Government., p. 9). In addition, it crosses multiple policy domains, levels of government and jurisdictions and, consequently, several, interdependent, stakeholders have brought in different views, priorities, values, cultural and political backgrounds and championing alternative solutions.

Among scientists, politicians and in the public opinion, there is a broad disagreement on what ‘the problem’ is which makes the search for solutions open-ended. Health, social and economic issues are intertwined creating several trade-offs.

The government at different levels, trade unions, and private firms’ associations champion alternative solutions and compete with one another to frame ‘the problem’ in a way that directly connects their preferred solution to their preferred definition of the problem. If not managed, this multiplicity will be easily translated in high degrees of conflict. Meanwhile, as our knowledge of COVID-19 increases, its understanding and, above all, the feasibility of solutions are subjected to constant changes. Constraints are generated by numerous interested parties who “come and go, change their minds, fail to communicate, or otherwise change the rules by which the problem must be solved” (Conklin & Weil, 1997Conklin, E. J; & Weil, W. (1997). Wicked problems: naming the pain in organizations. Austin, TX: Touchstone Consulting Group White Paper., p. 1; Roberts, 2000Roberts, N. (2000). Coping with Wicked Problems. In Proceedings of the Third Bi-Annual Research Conference of the International Public Management Network, Sydney, Australia.). Finally, an additional features of the COVID-19 that makes it as a wicked problem is the fact that this problem is relentless as it seems not be a finish line in view.

Several characteristics make the COVID-19 particularly apt for an integrated approach such as its widespread nature which is a first, logistical, driver. Among the high number of people affected, several of them are asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic which makes it a problem spread silently in all territory rather than being only concentrated in hospitals.This distinctive element goes hand in hand with the urgency to address it: scientists have highlighted that it is important to intervene in the first seven days for the cures to be effective. However, a delayed intervention is noted, with patients arriving at the hospital when they enter the final stage of the disease which is showed by the presence of evident serious respiratory problems.

The decreasing trust of citizens in government is another driver for adopting an integrated approach. For the aims of our article, it is interesting to notice that the decreasing confidence of people in their national governments is going hand in hand with a rising solidarity of local communities and businesses and the strong commitment of health workers to their communities. The growing understanding about the importance of the collective and community is the fertile ground on which our proposal is embedded (Bovaird, 2007Bovaird, T. (2007). Beyond engagement and participation: user and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 67(5), 846-860.; Bovaird, Flemig, Loeffler & Osborne, 2019Bovaird, T., Flemig, S., Loeffler, E., & Osborne, S. P. (2019). How far have we come with co-production - and what’s next?. Public Money and Management, 39(4), 229-232.; Cepiku, Marsilio, Sicilia & Vainieri, 2021Cepiku, D; Marsilio, M; Sicilia, M; & Vainieri, M. (2021). Co-production: activation, management and evaluation. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.; Loeffler, 2021Loeffler, E . (2021). Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan .).

3. RESEARCH AIMS AND METHODS

The article aims at starting a debate among policy makers, practitioners and academics on a potential inclusive approach to dealing with the COVID-19 which should be able to engage different professions and to integrate hospital care with territorial medicine and activating citizens and their communities. The information gathered to write this paper has been retrieved from official documents and public press statements as well as interviews of key informants from public and non-profit institutions at the forefront of the fight of COVID-19 in both Italy and Switzerland.

More specifically, in Italy, in March and April 2020 we interviewed 20 key respondents from the National Federation of Doctors and General Practitioners, the Italian FEMA (Protezione Civile), the Medical Professional Association of Rome, the Red Cross, the 118 emergency system, the health director of a prison located in Milan, Doctors without Borders, health director of INMI Lazzaro Spallanzani - National Institute of Infectious Diseases, health director of Cristo Re Hospital in Rome, doctors at the Tor Vergata University Hospital, the Head of a public health department in local health organization in Rome, the President and CEO of a non-profit organization providing social protection and social inclusion services in Milan.

In Switzerland, interviewees included the General Director, the Medical Director, the Head of the Quality and Patient Safety Service, the Head of the Nursing Service, the Head of Technical and Logistic Service, the Head of the Psychological Service, all at the Ospedale Regionale di Locarno “La Carità”; the General Director of the Clinica Luganese Moncucco; the General Director, the Medical Director, the Head of the Nursing Service and the Head of Technical and Engineering Service at the Cardiocentro Ticino.

4. STRATEGIES AGAINST THE COVID-19 IN ITALY

Italy has been one of the most badly-hit countries after the outbreak of the COVID-19 in Wuhan. The national emergency status was declared by end of January, after two coronavirus positive Chinese tourists were found in Rome. Three local sites emerged afterwards: on February 22nd in Lombardy, followed by the adjacent regions of Emilia Romagna and Veneto, soon followed by the spread of the virus throughout the entire country. The closure of schools and universities was decided in early March, followed by a partial lockdown. A complete lockdown in all the country was adopted on March 22nd. At the time of writing, Italy accounts for 525,782 cases and 37,338 deaths, although these figures underestimate the reality2 2 Ministry of health. Retrieved from http://arcg.is/C1unv .

Italy has a national health service created in 1978 which is based on two main principles: uniformity and solidarity. It was reformed several times in 1992-1993 and 1999 and the aim of these reforms was that of promoting market-type mechanisms, managerialism and regionalism.Consequenlty, Italy’s national health system is composed of 21 regional healthcare systems that are the result of, and being subjected to, national and regional policies. It is also worthy to note that this pandemic has hit the country after a decade of strict spending reviews and severe cost containment measures.

The Italian national government responded to the outbreak of the COVID-19 through the implementation of the following lines:

-

Enhancement of hospital capacity by creating new COVID-19 facilities, increasing ICU beds of 50% and pneumology and infectious diseases beds by 100%; introduction of a fast-track hiring procedure for both medical and nursing students and allowing retired healthcare professionals to go back to practice; developing an inter-regional collaboration mechanism called CROSS and simplifying procurement regulations;

-

Lockdown of all non-essential activities imposed partially and gradually;

-

Financial aid and support to businesses and families;

-

Last, and unfortunately least, delegation to the 21 regions to organize the territorial assistance to citizens and to COVID-19 asymptomatic, mild or recovered patients.

The first anomal cases were reported by GPs in early January but were not able to reach regional decision makers in the communication system, consequently, highlighting the weakness of epidemiological surveillance.

The main feature of the national policies is their main focus on the hospital response to the emergency, while being slow in organizing an effective response at the primary/community level. In the first phase of the emergency, the response to the pandemic completely neglected territorial assistance even in terms of communication as everything was focused on emergency services and hospital care.

Unfortunately, this continued after the initial shock and despite the call of several medical associations. Italy did not make the most of its GPs as at the beginning of the crisis, they were only assigned a very limited role of stopping the overflow of suspect patients to hospitals without following a care protocol. Moreover, community health systems lacked PPE for dealing with both COVID-19 and other patients, therefore, 63 out of 176 GPs involved were, unfortunately, victims of COVID-193 3 Retrieved from https://portale.fnomceo.it/elenco-dei-medici-caduti-nel-corso-dellepidemia-di-covid-19/ .

When the negative effects of the negligence of territorial and home assistance started to become evident also to the public opinion, the government accepted a proposal from the National Federation of Doctors and General Practitioners. On March 9th, the regions were asked to create special units of care continuity (USCA) by March 20th which, according to the Marche regional secretary of the National Federation of Doctors and General Practitioners, “represent the possibility to reach patients at home in a time when GPs are unable to do so because of shortage of personal protection equipment (PPE)”.

So far some regions have adopted guidelines mainly recommending the use of telemedicine, providing few incentives for it (40€ per working hour) but insufficient personal protection. As emerged from the interviews, telemedicine mainly relies on newly graduated medicine students who many of them, however, have to wait for organizational and logistical indications from permament staff who is already working close to maximum capacity.

As already mentioned, the Italian healthcare system is regionalized (i.e. regions retain some political, legislative and managerial autonomy even during an emergency status) and the regional responses varied accordingly to the different pre-COVID-regional healthcare models. For the purpose of our article, it is interesting to compare Lombardy and Veneto, two regions geographically close to each other that were both hardly hit by the sprrread of the virus but pursued very different strategies and achieved different outcomes (Bosa, 2020; Zanini, 2020bZanini, M. (2020b, March 27). Managing the Pandemic: Lessons From Italy’s Veneto Region. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@michelezanini/managing-the-pandemic-lessons-from-italys-veneto-region-4d1259091879

https://medium.com/@michelezanini/managi...

).

The Lombardy case study is effectively summarized in a letter written by the Regional Federation of Doctors and General Practitioners to the regional government highlighting. The letter highlights seven mistakes made in managing the COVID-19 crisis: no testing of people outside the hospitals, which also undermines data reliability; mismanagement of nursing homes for the elderly; no personal protection devices provided to doctors working in the territory (general practitioners, pediatricians, emergency doctors), which has brought the contagion and death of many of them as well as made them an involuntary vehicle of diffusion; the lack of public health actions such as isolating contacts and testing the community of potential patients and their contacts; failure to govern the territory which has determined a saturation of hospital beds, therefore, keeping people who could have been otherwise hospitalized at home. “The disaster that was created in our region (ed. Lombardy) is in large part to be attributed to the interpretation of the situation as an intensive care emergency, when in fact it is a public health emergency. Public health and territorial assistance have for a long time been neglected and depleted in our region”4 4 Retrieved from https://portale.fnomceo.it/fromceo-lombardia-nuova-lettera-indirizzata-ai-vertici-della-sanita-lombarda/?fbclid=IwAR3LJvtrSbHIploPbM9VN9vM1L2Ch7yAO8_eCOeA7pgnpwNbOFahTijX-V0 .

Another issue is related to defenceless people like the elderly who, due to the lockdown, have been abandoned by their usual in-home caregivers and family. Despite the greater reach of telemedicine, their GPs are unable to keep up with their health and social needs, which are unloaded on the emergency service.

On the other hand, Veneto implemented a different strategy from Lombardy. More specifically, the strategy implemented by the Venetian region is based on the extensive involvement of health professionals and academicians in the decions making in regard to COVID-19. More specifically, there are three key characteristics making Veneto’s response distinctive (Zanini, 2020bZanini, M. (2020b, March 27). Managing the Pandemic: Lessons From Italy’s Veneto Region. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@michelezanini/managing-the-pandemic-lessons-from-italys-veneto-region-4d1259091879

https://medium.com/@michelezanini/managi...

; Zingales, 2020Zingales, L. (2020, March 17). Why Mass Testing Is Crucial: the US Should Study the Veneto Model to Fight Covid-19. Promarket. Retrieved from https://promarket.org/2020/03/17/why-mass-testing-is-crucial-the-us-should-study-the-veneto-model-to-fight-covid-19/

https://promarket.org/2020/03/17/why-mas...

):

-

Focus on home diagnosis and care, handled by a dedicated group of over 720 disease prevention specialists, divided into fifteen teams across the region (performing regular check-ups to patients). This has reduced the burden on hospitals and minimized the risk of COVID-19 spread in medical facilities.

-

Extensive testing and active surveillance (tracing and isolation at home and in medical facilities). Such efforts relied on collaboration among hospitals, labs, and medical professionals deployed across the territory. The human and relational capital compensated the fact that testing and tracing were not as high tech as in Singapore and South Korea.

-

A hub and spoke network of dedicated hospitals for COVID-19 patients was established, which streamlined the process for intake and treatment, and reduced the risk of COVID-19 infections among medical staff and patients.

As well as avoiding the hospital-centric approach and making good use of its well-developed community health system, Veneto explicitly issued for third sector organizations operating in the reginal territory Guidelines to be followed in order to carry out volunteering activities in the framework of the epidemiological emergency of COVID-19 which was approved on April 10. The aim of these guidelines was that of strengthening the collaboration between voluntary organizations and public institutions, attracting new volunteers supporting public services and protecting volunteers from infection.

Local operational centres were created at local government level, where needs and priority intervention areas were identified, local volunteers recruited, trained and provided with PPE. Finally, the seven existing service centres for volunteering acted as a link between volunteers and local councils during the COVID-19 emergency - mainly through delivery of food and masks, accompanying elderly people on urgent medical visits, staffing mobile units to support homeless people and substance abusers, and provide psychological telephone support (also supporting the recruitment and training process of new volunteers to carry out lockdown activities).

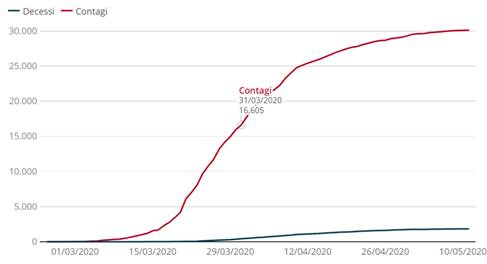

Veneto, which is the Italian reagion that experienced its first death on the same day as Lombardy did, seems to have a growth of infected people much slower than the other main Northern regions (Figure 1). Its approach has the merit of blocking contagion in the territory and not in hospitals (Sadun, Zanini & Pisano, 2020Sadun, R; Zanini, M; & Pisano G.P. (2020, March 27). Lessons from Italy’s Response to Coronavirus. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/03/lessons-from-italys-response-to-coronavirus

https://hbr.org/2020/03/lessons-from-ita...

).

The depicted experiences from Italy as well as those of other countries have shown that a more balanced and systemic approach covering the territory and home assistance is more effective than an approach exclusively focused on hospitals.

We are interested in making a step further by aiming for communities to be more actively engaged and aware that the current territorial medicine is unable to address the widespread nature of COVID-19 and that its risks will continue for at least a year, until a mass vaccination is carried out. Moreover, lockdown measures will inevitably loosen over time and control of contagiousness will rely on the socially responsible behavior and self-control measures adopted directly by citizens. Italy has one of the oldest populations in the World and has in time developed a high number of public and non-profit actors focusing on homecare. Therefore, we propose an approach focused on the territory and based on a strong collaboration between professionals of territorial medicine from different disciplines and local communities.This approach is also mentioned in a letter to national health authorities signed by 100.000 Italian doctors5 5 Retrieved from https://portale.fnomceo.it/fromceo-lombardia-nuova-lettera-indirizzata-ai-vertici-della-sanita-lombarda/?fbclid=IwAR3LJvtrSbHIploPbM9VN9vM1L2Ch7yAO8_eCOeA7pgnpwNbOFahTijX-V0 who declared that the main weakness of the national healthcare system in the fight of COVID-19 is the territory.

According to doctors operating in Bergamo, one of the hot zones in Lombardy, “in a pandemic, patient-centered care is inadequate and must be replaced by community-centered care where early oxygen therapy, pulse oximeters, and nutrition can be delivered to the homes of mildly ill and convalescent patients, setting up a broad surveillance system with adequate isolation and leveraging innovative telemedicine instruments.” (Grasselli, Pesenti & Cecconi, 2020Grasselli, G; Pesenti, A; & Cecconi, M. (2020, March 13). Critical case utilization for the Covid-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Online. Retrieved fromhttps://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763188

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fu...

; Heymann & Shindo 2020Heymann, D. L; & Shindo, N. (2020). COVID-19: what is next for public health?.The Lancet,395(10224), 542-545.; Nacoti et al., 2020Nacoti, M; Ciocca, A ; Giupponi, A; Brambillasca, P; Lussana, F; … Montaguti, C. (2020, March 21). At the Epicenter of the Covid-19. Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy: Changing Perspectives on Preparation and Mitigation. NEJM Catalyst. Retrieved from https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0080

https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.10...

, p. 1).

Alongside the loss of citizens’ confidence in their political leadership, images of solidarity have emerged. For instance, neighbors have organized themselves to support vulnerable people; businesses and national governments have stepped up to provide support for those who are in need and to strengthen social security and health services (Lancet, 2020Lancet, T. (2020). Covid-19: learning from experience. Lancet Editorial, 395(10229), 1011.). In addition, while it is clear that citizens are highly motivated to help each other in addressing their social and health needs, community contribution and engament are also feasible as they have the benefits of strengthening social control and promoting compliance in citizens’ behaviors. It is worth noting that a close collaboration between communities and medical personnel such as doctors and nurses would be the best way to make the most of it (Cepiku & Giordano, 2014Cepiku, D; & Giordano, F. (2014). Co-production in Developing Countries: Insights from the community health workers experience. Public Management Review, 16(3), 317-240.).

5. STRATEGIES AGAINST THE COVID-19 IN TICINO, SWITZERLAND

The Canton of Ticino, which is the canton bordering with the Region of Lombardy (Italy), represents an interesting case study to compare two experiences occurred in two different countries, but distant only 70 km from each other and with many social, linguistic, and traditional aspects of homogeneity. A strong hybridization is represented by about 60.000 cross-border workers who come every day from Lombardy (and partly also Piedmont) to Switzerland.

On 12 May 2020, the Canton of Ticino reported zero new infections and zero deaths despite a strong impact of the virus started with a sudden acceleration after February 25, Martedì Grasso (Shrove Tuesday) and the closing day of the Carnival. In the last 40 days, 3.268 cases were registered (out of a population of about 330.000 inhabitants) and, unfortunately, 340 deaths.

Ticino, together with the Canton of Geneva, has become an area requiring particular attention in the Swiss Confederation regarding strategies implemented in response to the pandemic (Figure 2).

There are four possible elements explaining the different response capacity and the results recorded in the fight against COVID-19. First, a sound model of governance and inter-institutional cooperation. Second, the development of public-private partnerships in the hospital system and, mainly, between the two COVID-19 hospitals (Hospital ‘La Carità’ in Locarno and Moncucco Clinic in Lugano).

Third, a system of emergency health services, acute care, long-term care, palliative care, and rehabilitation based on a multi-site model and on a networked system (Calciolari & Meneguzzo, 2018Calciolari, S., & Meneguzzo, M. (2018). Management ed innovazione in sanità. Lugano, Italy: Collana USI Editore Casagrande.). Fourth, the important role played by citizens’ and patients’ level of trust towards the hospitals and health system.

The center of governance and strategic coordination of the response to the pandemic was the ‘Stato Maggiore di Condotta’, activated by the Government of the Canton Ticino, coherently with the model adopted by the Federal Office for Population Protection. The Federal Civil Protection Crisis Management Board (FCPCM) is responsible for ensuring both the flow of information and the coordination with other federal and cantonal staffs and offices, and for coordinating expert knowledge and the deployment of national and international resources.

As the figure 3 shows, the Population Protection is an integrated system of management, protection an intervention that involves five main partner organizations: police, firefighters, public health, technical companies and civil protection, respectively.

Public-private collaboration has proven to be fundamental in two main areas: integrated offer of intensive care beds and procurement of drugs and medical supplies (Crivelli, 2020Crivelli, L. (2020, March 28). Il miracolo ticinese è riuscito grazie al pubblico e al privato. Corriere del Ticino. Retrieved from https://www.supsi.ch/home/dms/supsi/docs/comunica/stampa/2020/coronavirus-esperti/20200328_cdt_miracolo_ticinese.pdf

https://www.supsi.ch/home/dms/supsi/docs...

), confirming the strong and multi-annual experience of public private partnership characterizing the Swiss health system (Meneguzzo & Rossi, 2020Meneguzzo, M; & Rossi, G. (2020). Il partenariato pubblico privato nel sistema sanitario svizzero. In T. Gianella(Ed.), Il futuro del partenariato pubblico - privato; esperienze ed esempi in Svizzera ed all estero. Bellinzona, Switzerland: Casagrande Editore.).

The public health delivery system entrusted to the Cantonal Hospital (EOC) and based on a multi-site logic, reacted rapidly by designating a COVID-19 hospital (Hospital ‘La Carità’ in Locarno) where professional resources such as medical and nursing resources were concentrated. Consequently, the personnel involved in the fight against COVID-19 increased from about 900 FTE to 1400 FTE and, moreover, the internal logistics and space distribution were reorganized (Merlini, 2020Merlini, L. (2020, May 10). L’Ospedale La Carità di Locarno; la risposta al Covid-19. La Rivista del Locarnese e Valli.).

Most importantly, the initially six intensive care beds were increased to a total number of 45 beds, to which 25 beds were added to support patients after being disconnected from respirators (so-called “weaning” beds).

The response capacity was vigorously enhanced through the 32 intensive care beds activated within the Moncucco Clinic (which is a non-profit hospital that collaborated closely through a permanent discussion 24 hours 7 days) and the coordinated management of internal task forces (crisis cells).

In addition a strong collaboration was established with the local pharmaceutical industry, with the regulatory authority (SWISSMEDIC authorized the EOC to run drug trials) and with equipment manufacturers. Last but not least, due to the collaboration with the Army, 30 latest generation respirators were acquired to increase places in intensive care.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In order to effectively implement a collaborative approach among hospitals, territorial medicine and communities all aiming at preventing and fighting COVID-19, both sides - territorial medicine and communities - need to be well developed and equipped with the necessary resources. In addition, they need to trust each other and the collaboration needs to be managed (Cepiku et al., 2021Cepiku, D; Marsilio, M; Sicilia, M; & Vainieri, M. (2021). Co-production: activation, management and evaluation. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.).

In the two case studies analysed - Italy, with its two regions Veneto and Lombardy, and Ticino in Switzerland - results show how the lack or the presence of an integrated approach can make a change.

It is worthy of note that Switzerland has the highest level of trust toward public services according to the ‘Government at a glance report’ issued by the OECD.

Results also show that Italian regions with a stronger territorial medicine established before the crisis were more effective in containing the spread of the virus. However, it seems that managerial reforms of healthcare systems have weakened the ability to prevent disease and, consequently, deteriorating public health to the detriment of hospital care.

Figure 4 shows our proposal of an integrated approach to wicked problems, among others, the fight of COVID-19.

The key aspects of the model include (Cepiku & Giordano, 2014Cepiku, D; & Giordano, F. (2014). Co-production in Developing Countries: Insights from the community health workers experience. Public Management Review, 16(3), 317-240.; Lehmann & Sanders, 2007Lehmann, U; & Sanders, D. (2007). Community health workers: what do we know about them.The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers (pp. 1-42). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.; Liu, Sullivan, Khan, Sachs & Singh, 2011Liu, A; Sullivan, S; Khan, M; Sachs, S; & Singh, P. (2011). Community health workers in global health: scale and scalability.Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine,78(3), 419-435.):

-

The selection of lay actors serving as a bridge between health professionals and the community; they also need to be responsive to both groups.

-

Good program management due to the fact that unrealistic expectations, poor planning, and an underestimation of the effort and input required to make integration work are the main reasons of failure.

-

Supervision by professionals and logistic/infrastructure support in order to prevent the reoccurring of past mistakes such as shortage of PPE for health workers (Remuzzi & Remuzzi, 2020Remuzzi A; & Remuzzi G. (2020). Covid-19 and Italy: what next? Health Policy, 395(10231), 1225-1228.). They are vital to provide logistical support to lay actors and to ensure that they can effectively refer patients to other parts of the health system.

-

Political stewardship and adequate resourcing mean as a consequence of lay actors being recognized by legislation and policies.

Other key levers include the effectiveness of communication that ought to generate common consensus about what the two parties can do with and for each other; management of lay actors and health professionals such as training, motivation-building (also aimed at enhancing self-efficacy), socialization and group identity building.

The usage of community informational and relational capital and other resources can yield expected advantages such as a widespread and prompt response including clinical, social and economic benefits.

REFERENCES

- Agranoff, R. (2003). Leveraging networks: A guide for public managers working across organizations Washington, DC: IBM Endowment for the Business of Government.

- Bovaird, T. (2007). Beyond engagement and participation: user and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 67(5), 846-860.

- Bovaird, T., Flemig, S., Loeffler, E., & Osborne, S. P. (2019). How far have we come with co-production - and what’s next?. Public Money and Management, 39(4), 229-232.

- Calciolari, S., & Meneguzzo, M. (2018). Management ed innovazione in sanità Lugano, Italy: Collana USI Editore Casagrande.

- Cepiku, D; & Giordano, F. (2014). Co-production in Developing Countries: Insights from the community health workers experience. Public Management Review, 16(3), 317-240.

- Cepiku, D; Marsilio, M; Sicilia, M; & Vainieri, M. (2021). Co-production: activation, management and evaluation London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Conklin, E. J; & Weil, W. (1997). Wicked problems: naming the pain in organizations Austin, TX: Touchstone Consulting Group White Paper.

- Corona Data. (2020). Covid-19 Info Suiça Retrieved from http://www.corona-data.ch

» http://www.corona-data.ch - Crivelli, L. (2020, March 28). Il miracolo ticinese è riuscito grazie al pubblico e al privato. Corriere del Ticino Retrieved from https://www.supsi.ch/home/dms/supsi/docs/comunica/stampa/2020/coronavirus-esperti/20200328_cdt_miracolo_ticinese.pdf

» https://www.supsi.ch/home/dms/supsi/docs/comunica/stampa/2020/coronavirus-esperti/20200328_cdt_miracolo_ticinese.pdf - Grasselli, G; Pesenti, A; & Cecconi, M. (2020, March 13). Critical case utilization for the Covid-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Online Retrieved fromhttps://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763188

» https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763188 - Head, B. W. (2008). Wicked problems in public policy. Public policy, 3(2), 101-118.

- Heymann, D. L; & Shindo, N. (2020). COVID-19: what is next for public health?.The Lancet,395(10224), 542-545.

- Lancet, T. (2020). Covid-19: learning from experience. Lancet Editorial, 395(10229), 1011.

- Lehmann, U; & Sanders, D. (2007). Community health workers: what do we know about them.The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers (pp. 1-42). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Liu, A; Sullivan, S; Khan, M; Sachs, S; & Singh, P. (2011). Community health workers in global health: scale and scalability.Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine,78(3), 419-435.

- Loeffler, E . (2021). Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Meneguzzo, M; & Rossi, G. (2020). Il partenariato pubblico privato nel sistema sanitario svizzero. In T. Gianella(Ed.), Il futuro del partenariato pubblico - privato; esperienze ed esempi in Svizzera ed all estero Bellinzona, Switzerland: Casagrande Editore.

- Merlini, L. (2020, May 10). L’Ospedale La Carità di Locarno; la risposta al Covid-19. La Rivista del Locarnese e Valli

- Nacoti, M; Ciocca, A ; Giupponi, A; Brambillasca, P; Lussana, F; … Montaguti, C. (2020, March 21). At the Epicenter of the Covid-19. Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy: Changing Perspectives on Preparation and Mitigation. NEJM Catalyst Retrieved from https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0080

» https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0080 - Remuzzi A; & Remuzzi G. (2020). Covid-19 and Italy: what next? Health Policy, 395(10231), 1225-1228.

- Roberts, N. (2000). Coping with Wicked Problems. In Proceedings of the Third Bi-Annual Research Conference of the International Public Management Network, Sydney, Australia.

- Sadun, R; Zanini, M; & Pisano G.P. (2020, March 27). Lessons from Italy’s Response to Coronavirus. Harvard Business Review Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/03/lessons-from-italys-response-to-coronavirus

» https://hbr.org/2020/03/lessons-from-italys-response-to-coronavirus - Weber, E. P; & Khademian, A. M. (2008). Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public administration review, 68(2), 334-349.

- Zanini, M. (2020a). Italy COVID-19 Trends by Region Retrieved fromhttps://public.tableau.com/profile/michele.zanini#!/vizhome/ITALYCovid-19TrendsbyRegion/Summary

» https://public.tableau.com/profile/michele.zanini#!/vizhome/ITALYCovid-19TrendsbyRegion/Summary - Zanini, M. (2020b, March 27). Managing the Pandemic: Lessons From Italy’s Veneto Region. Medium Retrieved from https://medium.com/@michelezanini/managing-the-pandemic-lessons-from-italys-veneto-region-4d1259091879

» https://medium.com/@michelezanini/managing-the-pandemic-lessons-from-italys-veneto-region-4d1259091879 - Zingales, L. (2020, March 17). Why Mass Testing Is Crucial: the US Should Study the Veneto Model to Fight Covid-19. Promarket Retrieved from https://promarket.org/2020/03/17/why-mass-testing-is-crucial-the-us-should-study-the-veneto-model-to-fight-covid-19/

» https://promarket.org/2020/03/17/why-mass-testing-is-crucial-the-us-should-study-the-veneto-model-to-fight-covid-19/

-

1

Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/

-

2

Ministry of health. Retrieved from http://arcg.is/C1unv

-

3

Retrieved from https://portale.fnomceo.it/elenco-dei-medici-caduti-nel-corso-dellepidemia-di-covid-19/

-

4

Retrieved from https://portale.fnomceo.it/fromceo-lombardia-nuova-lettera-indirizzata-ai-vertici-della-sanita-lombarda/?fbclid=IwAR3LJvtrSbHIploPbM9VN9vM1L2Ch7yAO8_eCOeA7pgnpwNbOFahTijX-V0

-

5

Retrieved from https://portale.fnomceo.it/fromceo-lombardia-nuova-lettera-indirizzata-ai-vertici-della-sanita-lombarda/?fbclid=IwAR3LJvtrSbHIploPbM9VN9vM1L2Ch7yAO8_eCOeA7pgnpwNbOFahTijX-V0

-

[Original version&@93;

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

05 Mar 2021 -

Date of issue

Jan-Feb 2021

History

-

Received

19 May 2020 -

Accepted

08 Oct 2020

Source:

Source:  Note: blue line: deaths and red line: confirmed cases. Source:

Note: blue line: deaths and red line: confirmed cases. Source:  Source: BABS (2020).

Source: BABS (2020).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.