Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Leptospirosis is a zoonosis that affects both humans and animals. Dogs may serve as sentinels and indicators of environmental contamination as well as potential carriers for Leptospira. This study aimed to evaluate the seroprevalence and seroincidence of leptospirosis infection in dogs in an urban low-income community in southern Brazil where human leptospirosis is endemic.

METHODS:

A prospective cohort study was designed that consisted of sampling at recruitment and four consecutive trimestral follow-up sampling trials. All households in the area were visited, and those that owned dogs were invited to participate in the study. The seroprevalence (MAT titers ≥100) of Leptospira infection in dogs was calculated for each visit, the seroincidence (seroconversion or four-fold increase in serogroup-specific MAT titer) density rate was calculated for each follow-up, and a global seroincidence density rate was calculated for the overall period.

RESULTS:

A total of 378 dogs and 902.7 dog-trimesters were recruited and followed, respectively. The seroprevalence of infection ranged from 9.3% (95% CI; 6.7 - 12.6) to 19% (14.1 - 25.2), the seroincidence density rate of infection ranged from 6% (3.3 - 10.6) to 15.3% (10.8 - 21.2), and the global seroincidence density rate of infection was 11% (9.1 - 13.2) per dog-trimester. Canicola and Icterohaemorraghiae were the most frequent incident serogroups observed in all follow-ups.

CONCLUSIONS:

Follow-ups with mean trimester intervals were incapable of detecting any increase in seroprevalence due to seroincident cases of canine leptospirosis, suggesting that antibody titers may fall within three months. Further studies on incident infections, disease burden or risk factors for incident Leptospira cases should take into account the detectable lifespan of the antibody.

Leptospirosis; Dogs; Seroincidence; Seroprevalence; Slum

INTRODUCTION

Leptospirosis is a reemerging worldwide zoonosis caused by bacteria of the genus Leptospira (1)1 Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001; 14:296-326.. Leptospirosis can lead to acute infectious disease in humans as well as in domestic and wild animals, leading to potential economic losses and public health issues(2)2 Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Second edition. Melbourne: MediSci; 1999.. Although rats (Rattus norvegicus) are considered a worldwide reservoir and the main source of human infections, dogs may also play a role as pathogen reservoirs(3)3 Monahan AM, Callanan JJ, Nally JE. Review paper: host-pathogen interactions in the kidney during chronic leptospirosis. Vet Pathol 2009; 46:792-799. (4)4 Rojas P, Monahan AM, Schuller S, Miller IS, Markey BK,. Nally JE Detection and quantification of leptospires in urine of dogs: a maintenance host for the zoonotic disease leptospirosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 29:1305-1309. in the disease cycle(5)5 Viegas S, Tavares CHT, Oliveira EMD, Dias AR, Mendonça FF, Santos MFP. Investigação sorológica para leptospirose em cães errantes na Cidade de Salvador, Bahia. Rev Bras Saude Prod An 2001; 2:21-30.. In developing countries, disease outbreaks are related to climatic conditions and are favored by high temperatures and rainfall during specific periods of the year(6)6 Tassinari WS, Pellegrini DCP, Sá CBP, Reis RB, Ko AI, Carvalho MS. Detection and modelling of case clusters for urban leptospirosis. Trop Med Intern Health 2008; 13:503-512.. Lack of basic sanitation, poor housing conditions and limited access to education and health increase the risk of human infection in urban areas(7)7 Riley LW, Ko AI, Unger A, Reis MG. Slum health: diseases of neglected populations. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2007; 7:2. (8)8 Picardeau M, Maciel EAP, Carvalho ALF, Nascimento SF, Matos RB, Gouveia EL, et al. Household Transmission of Leptospira Infection in Urban Slum Communities. PLoS Neg Trop Dis 2008; 2:e154..

In Brazil, approximately 10,000 cases of human leptospirosis are reported annually,

typically during periods of higher rainfall levels(9)9 McBride AJ, Athanazio DA, Reis MG,. Ko AI Leptospirosis. Curr Opin

Infect Dis 2005; 18:376-386.. Mortality rates average between 10% and 15%(10)10 Ko AI, Reis MG Dourado CMR, Johnson WD,. Riley LW Urban epidemic of

severe leptospirosis in Brazil. The Lancet 1999; 354:820-825.. Leptospirosis epidemics have been reported in several highly

populated areas of Brazil(10)10 Ko AI, Reis MG Dourado CMR, Johnson WD,. Riley LW Urban epidemic of

severe leptospirosis in Brazil. The Lancet 1999; 354:820-825. including Curitiba,

a city with one of the highest mortality rates of human leptospirosis nationwide(11)11 Ministério da Saúde. Leptospirose - Casos confirmados notificados no

Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação - SINAN Net.; Available from:

http://dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/tabnet/tabnet?sinannet/lepto/bases/leptobrnet.def.

http://dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/tab...

.

The role of dogs in human infection remains controversial. Although dog ownership has been previously identified as a risk factor for severe human leptospirosis(12)12 Douglin CP, Jordan C, Rock R, Hurley A,. Levett PN Risk factors for severe leptospirosis in the parish of St. Andrew, Barbados. Emerg Infect Dis 1997; 3:78-80., evidence of human infection in a low-income community in Brazil was not associated with dog ownership(6)6 Tassinari WS, Pellegrini DCP, Sá CBP, Reis RB, Ko AI, Carvalho MS. Detection and modelling of case clusters for urban leptospirosis. Trop Med Intern Health 2008; 13:503-512.. The serogroups associated with human infection(6)6 Tassinari WS, Pellegrini DCP, Sá CBP, Reis RB, Ko AI, Carvalho MS. Detection and modelling of case clusters for urban leptospirosis. Trop Med Intern Health 2008; 13:503-512. (13)13 Romero EC, Bernardo CC, Yasuda PH. Human leptospirosis: a twenty-nine-year serological study in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2003; 45:245-248. (14)14 Yersin C, Bovet P, Merien F, Wong T, Panowsky J,. Perolat P Human leptospirosis in the Seychelles (Indian Ocean): a population-based study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998; 59:933-940. also suggest that the role of dogs in human infection may be limited or non-existent(15)15 Martins G, Penna B, Lilenbaum W. The dog in the transmission of human leptospirosis under tropical conditions: victim or villain? Epidemiol Infec 2012; 140:207-208.. Regardless, there is general consensus that canine disease acts as an indicator for human exposure risk(16)16 Davis MA, Evermann JF, Petersen CR, VanderSchalie J, Besser TE, Huckabee J, et al. Serological survey for antibodies to Leptospira in dogs and raccoons in Washington State. Zoonoses and Public Health 2008; 55: 436-442.; dogs are more frequently exposed to known risk factors of disease and thus may act as sentinels of environmental contamination(15)15 Martins G, Penna B, Lilenbaum W. The dog in the transmission of human leptospirosis under tropical conditions: victim or villain? Epidemiol Infec 2012; 140:207-208. (17)17 Fonzar UJ, Langoni H. Geographic analysis on the occurrence of human and canine leptospirosis in the city of Maringa, state of Parana, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012; 45:100-105..

The prevalence of Leptospira spp. antibodies in dogs varies widely in Brazil, ranging from 7.1% to 32.2%(18)18 Oliveira Lavinsky M, Said RA, Strenzel GMR,Langoni H Seroprevalence of anti-Leptospira spp. antibodies in dogs in Bahia, Brazil. Prev Vet Med. 2012; 106:79-84. (19)19 Magalhães DF, Silva JA, Moreira EC, Wilke VML, Nunes ABV, Haddad JPA, et al. Perfil dos cães sororreagentes para aglutininas anti-Leptospira interrogans em Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2001/2002. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 2007; 59:1326-1329. (20)20 Batista CSA, Alves CJ, Azevedo SS, Vasconcellos SA, Morais ZM, Clementino IJ, et al. Soroprevalência e fatores de risco para a leptospirose em cães de Campina Grande, Paraíba. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec2005; 57:179-185. (21)21 Blazius RD, Romao PR, Blazius EM, Silva OS. Occurrence of Leptospira spp. soropositive stray dogs in Itapema, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2005; 21:1952-1956. (22)22 Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Marvulo MFV, Silva JCR, Pinter A, Vasconcellos SA, et al. Fatores de risco associados à ocorrência de anticorpos anti-Leptospira spp. em cães do município de Monte Negro, Rondônia, Amazônia Ocidental Brasileira. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec2007; 59:70-76. (23)23 Tesserolli GL, Alberti JVA, Bergamaschi C, Fayzano L, Agottani JVB. Principais sorovares de leptopirose canina em Curitiba, Paraná. PUBVET. 2008; 2: n. 21.. Even within State of Parana, antibody prevalence varies: 12.2% in stray dogs(17)17 Fonzar UJ, Langoni H. Geographic analysis on the occurrence of human and canine leptospirosis in the city of Maringa, state of Parana, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012; 45:100-105., 30.5% in dogs treated in a Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Northern State(24)24 Querino AMVD, Delbem ACB, Oliveira RC, Silva FG, Müller EE, Freire RL, et al. Fatores de risco associados à leptospirose em cães do município de Londrina-PR. Semina: Ciênc Agrárias 2003; 24:27-34., and 32.2% (n = 598) in diagnostic serum samples taken from dogs in Curitiba(23)23 Tesserolli GL, Alberti JVA, Bergamaschi C, Fayzano L, Agottani JVB. Principais sorovares de leptopirose canina em Curitiba, Paraná. PUBVET. 2008; 2: n. 21.. Only one study of incidence rates in dogs has been conducted, which reported an annual incidence of 28.9% in a slum community of Curitiba City(25)25 Martins CM, Barros CC, Galindo CM, Kikuti M, Ullmann LS, Pampuch RS, et al. Incidence of canine leptospirosis in the metropolitan area of Curitiba, State of Parana, Southern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop2013;46:772-775.. As such, the present study aimed to evaluate the seroprevalence and seroincidence of canine leptospirosis in an endemic slum community via four follow-up samplings throughout a single year.

METHODS

Study design and area

A closed, prospective, descriptive cohort study was designed to identify the serological prevalence and incidence of Leptospira infection in dogs. The study was conducted in 2009 and 2010 in the Vila Pantanal neighborhood (25°32'17"S 49°13'55"W), a riverside slum community located in the City of Curitiba, southern Brazil, where human leptospirosis is considered endemic. Material recycling is the main source of income for the 2,653 people living in approximately 850 households in this neighborhood, 40% of which earned less than the Brazilian monthly minimum wage of approximately US$290 during the study period(26)26 Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2010. Característica da população e dos domicílios. Resultados do universo. Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. 2010.. This study site was selected because of reports of human cases of Leptospira (thus the possibility of environmental exposure of dogs to Leptospira). In addition, the study site's socioeconomic characteristics are similar to those of other resource-deprived communities in both Brazil and other countries, sites where Leptospira infections are known to be more prevalent(27)27 Reis RB Ribeiro GS, Felzemburgh RDM, Santana FS, Mohr S, Melendez AXTO, et al. Impact of Environmental and Social Gradient on Leptospira Infection in Urban Slums. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008; 2:e228..

Participants

All residential households were visited, but only those that owned at least one dog were invited to voluntarily participate in the study. Additional eligibility criteria for inclusion were the ownership of dogs older than 3 months of age, and both the owner and dog being present at the household at the time of visit. Exclusion criteria included dog aggressiveness and poor animal health conditions not related to leptospirosis. All dogs were recruited on October 3rd and 4th, 2009 and revisited for re-sampling during four follow-up periods (January 30th and 31st, 2010; April 24th and 25th, 2010; July 31st, 2010; and November 20th, 2010). Blood samples (10mL) were collected at each household by venipuncture of the jugular vein using tubes without anticoagulant by groups of veterinary students who were supervised by veterinary doctors. Blood samples were packed in Styrofoam boxes with -20ºC icepacks for a maximum of three hours prior to centrifugation, which was conducted at 1,200G for 15 min. Serum was separated and stored at -20°C until testing. Basic descriptive characteristics of the dogs (sex, age and breed) were collected at recruitment to allow re-identification of animals during each follow-up visit.

Variables

Evidence of previous leptospirosis infection was defined as serologic microscopic agglutination test (MAT) titers equal to or higher than 100 (initial dilution of 1:100; the serogroups and strains that were tested are reported in Table 1 and were selected based on important serogroups for dog infection(2)2 Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Second edition. Melbourne: MediSci; 1999.), a cut-off MAT value that has been recommended by other authors(28)28 Faine S. Leptospira and leptospirosis Melbourne: MediSci; 1999. for its sensitivity in detecting Leptospira while avoiding unspecific cross-reactions. IncidentLeptospira infection was defined as seroconversion (MAT titer equal to or higher than 100, given a non-reagent result for the serogroup in the immediately previous follow-up) or a four-fold increase in the serougroup's titer relative to the immediately previous follow-up. The serogroup with the highest titer was considered responsible for the infection. In the event of more than one serogroup with equally high titers, one event of infection was considered with an undetermined responsible serogroup (more than one serogroup potentially responsible for the infection; described as co-infections in Table 1.

Study size

Due to the small size of the study area, we attempted to recruit all owned dogs in Vila Pantanal by visiting all residential buildings. Therefore, this study may be considered population-based due to the recruitment of all dogs in Vila Pantanal that met both the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Statistical methods

Demographic and laboratory data were entered in an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed with STATA 12 software (Stata Corp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX, USA). The characteristics of each dog recorded during each immediate follow-up, as well as the total number of follow-ups, were described using absolute or relative frequencies. Age was categorized according to the baseline's median and interquartile range distribution. A Pearson's chi square test was calculated for each characteristic for each visit to compare included and excluded animals.

Descriptive analysis of infecting serogroup prevalence in each follow-up was performed based on the number of infections for each serogroup, including cases in which more than one serogroup may have been responsible for the infection. The seroprevalence of leptospirosis infection was calculated by dividing the number of seropositive dogs by the total number of dogs sampled for each visit. A seroincidence density rate was calculated for each follow-up, and a global seroincidence density rate was calculated for the overall period.

Dog-trimester was the chosen unit for calculating the seroincidence density rates

because of the three-month average time span between sampling. Because dogs could

have not been followed in one or more of the four follow-ups and thus exhibited

different contribution times to the cohort, calculation using dog-trimester units

generates a more accurate measure of frequency because it represents the

trimester-adjusted time of follow-up. The time of contribution for each dog was

obtained in each follow-up by calculating the number of days elapsed since the

previous survey. Because infection may have occurred at any time between visits, the

contribution time in terms of dog-trimesters of the dogs that were infected was

considered to be the mean point between visits. The global seroincidence density rate

was calculated by dividing the total number of infections detected during the overall

period by the total contribution time of dogs in dog-trimesters. The seroprevalence

and seroincidence density rates and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated

using Open Epi software(29)29 Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic

Statistics for Public Health, Version 3.03. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2014/09/22,

accessed 2014/11/22.

http://www.openepi.com...

.

Ethical considerations

The protocol for this study was approved by the Universidade Federal do Parana Ethics Committee on Animal Research, under protocol number 007/2009.

RESULTS

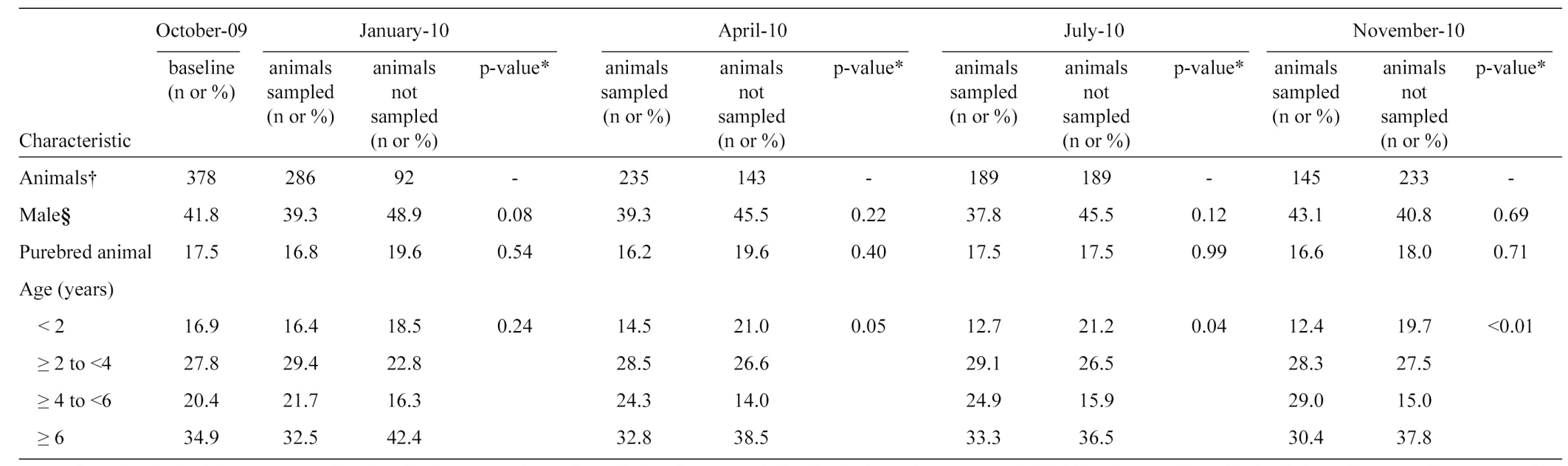

We recruited 378 dogs from 221 households at baseline. Males made up approximately 42% of the recruited population ( Table 2 ), 18% of the dogs were considered purebred by their owners, and the population was mostly composed of young adult animals (median age of 4 years, interquartile range: 2-6). Dogs sampled during subsequent surveys were similar to animals not sampled with respect to gender and breed in all follow-up surveys, but sampled animals were slightly older than non-sampled animals in July and November of 2010 (there were no differences when age was tested as a continuous variable). Dog characteristics according to the total number of follow-ups conducted is described in Table 3. Loss to follow-up ranged from 24.3% on the first follow-up visit to 61.8% on the last visit ( Table 4 ). Although quantitative data concerning reasons for follow-up losses were not available, the main reasons included an inability to locate the dogs on subsequent visits and animal death. The contribution of the dogs in each follow-up ranged from 346 to 168 dog-trimesters, and the global follow-up contribution of dogs was 902.7 dog-trimesters ( Table 4 ).

A total of 163 positive blood samples were detected out of the 1,233 collected samples. The seroprevalence of infection for each survey ranged from 9.3% (95% CI; 6.7 - 12.6) in October 2009 to 19.0% (95% CI; 14.1 - 25.2) in July 2010. We identified 99 events of infection in 79 animals (20 animals had two events of infection during the one-year period). The seroincidence density rate of infection ranged from 6.0% (95% CI; 3.3 - 10.6) in July-November 2010 to 15.3% (95% CI; 10.8 - 21.2) in April-July 2010. We were able to detect animals that transitioned from positive to negative between surveys. The global incidence density rate of infection was 11.0% (95% CI; 9.1 - 13.2) per dog-trimester. Canicola was the most frequent serogroup responsible for new infections in all four follow-ups, followed by Icterohaemorraghiae ( Table 1 ).

DISCUSSION

We conducted our study in an area characterized by extreme poverty, lack of urban infrastructure and a regular occurrence of flooding. The observed seroprevalence ratios ranged from 9.3% to 19%, and the overall seroincidence density rate was 11.0 per 100 dog-trimesters, ranging from 6.0 to 15.3. Previous studies in Brazil reported a lower prevalence (7.1%)(18)18 Oliveira Lavinsky M, Said RA, Strenzel GMR,Langoni H Seroprevalence of anti-Leptospira spp. antibodies in dogs in Bahia, Brazil. Prev Vet Med. 2012; 106:79-84.; however, the dogs tested in that study were selected from different locations within a city, and the study was conducted in an area with a better overall social condition, which may result in a lower prevalence of Leptospira infection relative to our study site. Studies with similar (10.5% in stray dogs)(21)21 Blazius RD, Romao PR, Blazius EM, Silva OS. Occurrence of Leptospira spp. soropositive stray dogs in Itapema, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2005; 21:1952-1956. and higher (27.3% in dogs in both urban and rural areas in the Amazon region and 21.4% in dogs sampled from an anti-rabies vaccination campaign)(20)20 Batista CSA, Alves CJ, Azevedo SS, Vasconcellos SA, Morais ZM, Clementino IJ, et al. Soroprevalência e fatores de risco para a leptospirose em cães de Campina Grande, Paraíba. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec2005; 57:179-185. (22)22 Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Marvulo MFV, Silva JCR, Pinter A, Vasconcellos SA, et al. Fatores de risco associados à ocorrência de anticorpos anti-Leptospira spp. em cães do município de Monte Negro, Rondônia, Amazônia Ocidental Brasileira. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec2007; 59:70-76. prevalences were also found. Those studies demonstrated that Leptospira infection is not a rare event in dogs and that the point prevalence is context dependent. One study reported an incidence of 28.9% per year(25)25 Martins CM, Barros CC, Galindo CM, Kikuti M, Ullmann LS, Pampuch RS, et al. Incidence of canine leptospirosis in the metropolitan area of Curitiba, State of Parana, Southern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop2013;46:772-775. in a community with socioeconomic and environmental characteristics similar to those of Vila Pantanal, but because the follow-up interval period was one year, infections may have gone undetected. Interestingly, in our study, we were able to ascertain that 20 out of 79 (25%) dogs infected during the overall period were infected more than once throughout the year.

The MAT is known for its good sensitivity(30)30 Ahmad SN, Ahmad FMH. Laboratory Diagnosis of Leptospirosis. J Postgrad Med 2005; 51:195-200. and is recognized as the gold-standard in Leptospirosis diagnosis, especially when clinical symptoms are present and when sufficient time to seroconversion has elapsed. Due to the design of this study, animals were tested regardless of their clinical symptoms and at arbitrary points in time. The seroprevalence and seroincidence of infection might be higher in animals with clinical symptoms and given sufficient time for seroconversion once clinical symptoms begin. In our study, Canicola and Icterohaemorraghiae were the most frequent serogroups responsible for new infections, and both are traditionally identified in canine Leptospira infections(31)31 Rodríguez AL, Ferro BE, Varona MX, Santafpe M. Exposure to Leptospira in stray dogs in the city of Cali. Biomédica. 2004; 24:291-295. (32)32 Kikuti M Langoni H, Nóbrega DN, Corrêa APFL,. Ullmann LS Occurrence and risk factors associated with canine leptospirosis. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2012; 18:124-127. (33)33 Suepaul SM, Carrington CVF, Campbell M, Borde G, Adesiyun AA. Serovars of Leptospira isolated from dogs and rodents. Epidemiol Infec2009; 138:1059-1070. (34)34 Cruz-Romero A, Romero-Salas D, Aguirre CA, Aguilar-Domínguez M, Bautista-Piña C. Frequency of canine leptospirosis in dog shelters in Veracruz, Mexico. Afr J Microbiol Res 2013; 7:1518-1521..

We were unable to detect an increase in the seroprevalence of leptospirosis proportional to incident cases. We would expect that seroprevalence would increase in accordance with the seroincidence of the previous follow-up if antibodies remained detectable with three-month interval periods. This finding may suggest that serological evidence of infection (not necessarily clinical) in naturally infected dogs may remain undetected within three months, at least considering an initial MAT dilution of 1:100. If true, infection events may have gone undetected in our study, thus the seroincidence of Leptospira infection in dogs of this community may be underestimated. Studies reporting the duration of antibodies for leptospirosis in animals are scarce(2)2 Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Second edition. Melbourne: MediSci; 1999.. Differences among the studies may be the result of different infection phases, such as clinically ill dogs (e.g., detected in veterinary hospitals), asymptomatic dogs in serological surveys and vaccinated dogs. Although antibodies may be detected for up to 20 years following human infection(35)35 Blackmore DK, Schollum LM, Moriarty KM. The magnitude and duration of titres of leptospiral agglutinins in human sera. N Z Med J 1984; 97:83-86., how long naturally infected animals maintain detectable titers remains unclear, and further studies should be conducted to fully establish the lifespan of antibodies under such conditions.

Losses experienced during the follow-up samplings were the major limitation of the present study, highlighting the difficulty in performing a prospective cohort study on dog populations, particularly in slum areas. Under real disease scenarios, death and absence at the time of visit due to outdoor access may post major obstacles for successful re-samplings. However, given the basic demographic characteristics of the dogs, follow-up losses may not have introduced significant bias in light of the fact that the followed dogs appeared to be similar to the not-followed ones.

In conclusion, our study first established the trimester seroincidence of canine leptospirosis and additionally demonstrated that antibody lifespan may impair epidemiological serosurveys of such populations. Moreover, incidence density measure allows for a better estimation of frequency and should be used in studies aiming to prospectively identify risk factors for canine leptospirosis, as the time of contribution of each observation is taken into account when calculating incidence density. Finally, we suggest that prospective incidence studies of dogs should be conducted using re-sampling periods shorter than three-month intervals, especially if MAT is set at an initial dilution of 1:100 to detect infections.

-

1Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001; 14:296-326.

-

2Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Second edition. Melbourne: MediSci; 1999.

-

3Monahan AM, Callanan JJ, Nally JE. Review paper: host-pathogen interactions in the kidney during chronic leptospirosis. Vet Pathol 2009; 46:792-799.

-

4Rojas P, Monahan AM, Schuller S, Miller IS, Markey BK,. Nally JE Detection and quantification of leptospires in urine of dogs: a maintenance host for the zoonotic disease leptospirosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 29:1305-1309.

-

5Viegas S, Tavares CHT, Oliveira EMD, Dias AR, Mendonça FF, Santos MFP. Investigação sorológica para leptospirose em cães errantes na Cidade de Salvador, Bahia. Rev Bras Saude Prod An 2001; 2:21-30.

-

6Tassinari WS, Pellegrini DCP, Sá CBP, Reis RB, Ko AI, Carvalho MS. Detection and modelling of case clusters for urban leptospirosis. Trop Med Intern Health 2008; 13:503-512.

-

7Riley LW, Ko AI, Unger A, Reis MG. Slum health: diseases of neglected populations. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2007; 7:2.

-

8Picardeau M, Maciel EAP, Carvalho ALF, Nascimento SF, Matos RB, Gouveia EL, et al. Household Transmission of Leptospira Infection in Urban Slum Communities. PLoS Neg Trop Dis 2008; 2:e154.

-

9McBride AJ, Athanazio DA, Reis MG,. Ko AI Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2005; 18:376-386.

-

10Ko AI, Reis MG Dourado CMR, Johnson WD,. Riley LW Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. The Lancet 1999; 354:820-825.

-

11Ministério da Saúde. Leptospirose - Casos confirmados notificados no Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação - SINAN Net.; Available from: http://dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/tabnet/tabnet?sinannet/lepto/bases/leptobrnet.def.

» http://dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/tabnet/tabnet?sinannet/lepto/bases/leptobrnet.def. -

12Douglin CP, Jordan C, Rock R, Hurley A,. Levett PN Risk factors for severe leptospirosis in the parish of St. Andrew, Barbados. Emerg Infect Dis 1997; 3:78-80.

-

13Romero EC, Bernardo CC, Yasuda PH. Human leptospirosis: a twenty-nine-year serological study in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2003; 45:245-248.

-

14Yersin C, Bovet P, Merien F, Wong T, Panowsky J,. Perolat P Human leptospirosis in the Seychelles (Indian Ocean): a population-based study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998; 59:933-940.

-

15Martins G, Penna B, Lilenbaum W. The dog in the transmission of human leptospirosis under tropical conditions: victim or villain? Epidemiol Infec 2012; 140:207-208.

-

16Davis MA, Evermann JF, Petersen CR, VanderSchalie J, Besser TE, Huckabee J, et al. Serological survey for antibodies to Leptospira in dogs and raccoons in Washington State. Zoonoses and Public Health 2008; 55: 436-442.

-

17Fonzar UJ, Langoni H. Geographic analysis on the occurrence of human and canine leptospirosis in the city of Maringa, state of Parana, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012; 45:100-105.

-

18Oliveira Lavinsky M, Said RA, Strenzel GMR,Langoni H Seroprevalence of anti-Leptospira spp. antibodies in dogs in Bahia, Brazil. Prev Vet Med. 2012; 106:79-84.

-

19Magalhães DF, Silva JA, Moreira EC, Wilke VML, Nunes ABV, Haddad JPA, et al. Perfil dos cães sororreagentes para aglutininas anti-Leptospira interrogans em Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2001/2002. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 2007; 59:1326-1329.

-

20Batista CSA, Alves CJ, Azevedo SS, Vasconcellos SA, Morais ZM, Clementino IJ, et al. Soroprevalência e fatores de risco para a leptospirose em cães de Campina Grande, Paraíba. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec2005; 57:179-185.

-

21Blazius RD, Romao PR, Blazius EM, Silva OS. Occurrence of Leptospira spp. soropositive stray dogs in Itapema, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2005; 21:1952-1956.

-

22Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Marvulo MFV, Silva JCR, Pinter A, Vasconcellos SA, et al. Fatores de risco associados à ocorrência de anticorpos anti-Leptospira spp. em cães do município de Monte Negro, Rondônia, Amazônia Ocidental Brasileira. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec2007; 59:70-76.

-

23Tesserolli GL, Alberti JVA, Bergamaschi C, Fayzano L, Agottani JVB. Principais sorovares de leptopirose canina em Curitiba, Paraná. PUBVET. 2008; 2: n. 21.

-

24Querino AMVD, Delbem ACB, Oliveira RC, Silva FG, Müller EE, Freire RL, et al. Fatores de risco associados à leptospirose em cães do município de Londrina-PR. Semina: Ciênc Agrárias 2003; 24:27-34.

-

25Martins CM, Barros CC, Galindo CM, Kikuti M, Ullmann LS, Pampuch RS, et al. Incidence of canine leptospirosis in the metropolitan area of Curitiba, State of Parana, Southern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop2013;46:772-775.

-

26Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2010. Característica da população e dos domicílios. Resultados do universo. Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. 2010.

-

27Reis RB Ribeiro GS, Felzemburgh RDM, Santana FS, Mohr S, Melendez AXTO, et al. Impact of Environmental and Social Gradient on Leptospira Infection in Urban Slums. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008; 2:e228.

-

28Faine S. Leptospira and leptospirosis Melbourne: MediSci; 1999.

-

29Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 3.03. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2014/09/22, accessed 2014/11/22.

» http://www.openepi.com -

30Ahmad SN, Ahmad FMH. Laboratory Diagnosis of Leptospirosis. J Postgrad Med 2005; 51:195-200.

-

31Rodríguez AL, Ferro BE, Varona MX, Santafpe M. Exposure to Leptospira in stray dogs in the city of Cali. Biomédica. 2004; 24:291-295.

-

32Kikuti M Langoni H, Nóbrega DN, Corrêa APFL,. Ullmann LS Occurrence and risk factors associated with canine leptospirosis. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2012; 18:124-127.

-

33Suepaul SM, Carrington CVF, Campbell M, Borde G, Adesiyun AA. Serovars of Leptospira isolated from dogs and rodents. Epidemiol Infec2009; 138:1059-1070.

-

34Cruz-Romero A, Romero-Salas D, Aguirre CA, Aguilar-Domínguez M, Bautista-Piña C. Frequency of canine leptospirosis in dog shelters in Veracruz, Mexico. Afr J Microbiol Res 2013; 7:1518-1521.

-

35Blackmore DK, Schollum LM, Moriarty KM. The magnitude and duration of titres of leptospiral agglutinins in human sera. N Z Med J 1984; 97:83-86.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

jan-feb 2015

History

-

Received

22 Sept 2014 -

Accepted

09 Feb 2015