Abstracts

The Amazon rainforest stretches across more than six million square kilometers and nine countries. Of the original forest area it is thought that 18 per cent has been cleared, mainly for farming purposes. In Brazil, the main drivers of deforestation are beef ranching and soya production that together occupy more than 75 per cent of newly deforested land. The situation in the Amazon illustrates a fundamental dilemma facing environmentalists around the world: how to reconcile economic development with biodiversity conservation. In this paper the representation of this dilemma in the British and Brazilian news media is assessed. The results indicate that there were far more articles referring to deforestation in the Brazilian press (816 Brazilian to 29 UK) but that many of these make no mention of what factors are responsible for deforestation. The patterns of representation of the proximate (direct) causes of Amazonian deforestation were very similar in the two countries, with soya and beef cattle ranching commanding the most press attention. The ultimate (indirect) causes of deforestation, however, are treated very differently, with the Brazilian media seemingly far more aware of the role of economic development needs than the UK press. Interestingly, the role of international demand for soya, beef, and forest products in driving deforestation was highlighted primarily in the UK press. These findings are critically discussed in the context of media influence on public understandings of Amazonian deforestation.

development; globalization; Amazon rainforest; newspapers

A floresta Amazônica abrange mais de 6 milhões de km² e engloba 9 países. Acredita-se que 18% da superficie florestal já tenha sido desmatada principalmente para usos agropecuários. No Brasil, a pecuária e a produção de soja encabeçam as causas do desmatamento, sendo estes responsáveis por 75% das terras desmatadas. A situação da Amazônia ilustra o principal dilema que enfrentam os ambientalistas em todo o mundo: como permitir um desenvolvimento econômico que mantenha a biodiversidade. Este estudo examina a representação deste dilema na mídia britânica e brasileira. Foram encontrados 816 artigos nos jornais brasileiros e apenas 29 nos jornais britânicos. No entanto, a grande maioria dos artigos não discutem as causas do desmatamento. A representação das causas diretas do desmatamento é extremamente similar nos dois países sendo soja e pecuária os principais fatores apontados pela mídia. Entretanto, os fatores secundários são tratados diferentemente, sendo que a mídia brasileira mostra como principal fator a necessidade de desenvolvimento econômico. Por outro lado, o papel da demanda internacional da soja, carne e produtos florestais como causas do desmatamento foi bastante discutida na mídia inglesa. Os resultados destas representações em relação a influência que a mídia exerce no entendimento do desmatamento da Amazônia são discutidos.

desmatamento; globalização; Amazônia; mídia

CIÊNCIAS FLORESTAIS

Perceptions of Amazonian deforestation in the British and Brazilian media

Percepções do desmatamento da Amazônia na mídia Britânica e Brasileira

Richard J. LADLEI, Ana Claudia Mendes MALHADOII, Peter A. TODDIII, Acacia C. M. MALHADOIV

IUniversity of Oxford, E-mail: richard.ladle@ouce.ox.ac.uk

IIUniversidade Federal de Viçosa, E-mail: anaclaudiamalhado@gmail.com

IIINational University of Singapore, E-mail: dbspat@nus.edu.sg

IVUniversity of Munich, E-mail: lackinha@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

The Amazon rainforest stretches across more than six million square kilometers and nine countries. Of the original forest area it is thought that 18 per cent has been cleared, mainly for farming purposes. In Brazil, the main drivers of deforestation are beef ranching and soya production that together occupy more than 75 per cent of newly deforested land. The situation in the Amazon illustrates a fundamental dilemma facing environmentalists around the world: how to reconcile economic development with biodiversity conservation. In this paper the representation of this dilemma in the British and Brazilian news media is assessed. The results indicate that there were far more articles referring to deforestation in the Brazilian press (816 Brazilian to 29 UK) but that many of these make no mention of what factors are responsible for deforestation. The patterns of representation of the proximate (direct) causes of Amazonian deforestation were very similar in the two countries, with soya and beef cattle ranching commanding the most press attention. The ultimate (indirect) causes of deforestation, however, are treated very differently, with the Brazilian media seemingly far more aware of the role of economic development needs than the UK press. Interestingly, the role of international demand for soya, beef, and forest products in driving deforestation was highlighted primarily in the UK press. These findings are critically discussed in the context of media influence on public understandings of Amazonian deforestation.

KEYWORDS: development, globalization, Amazon rainforest, newspapers

RESUMO

A floresta Amazônica abrange mais de 6 milhões de km2 e engloba 9 países. Acredita-se que 18% da superficie florestal já tenha sido desmatada principalmente para usos agropecuários. No Brasil, a pecuária e a produção de soja encabeçam as causas do desmatamento, sendo estes responsáveis por 75% das terras desmatadas. A situação da Amazônia ilustra o principal dilema que enfrentam os ambientalistas em todo o mundo: como permitir um desenvolvimento econômico que mantenha a biodiversidade. Este estudo examina a representação deste dilema na mídia britânica e brasileira. Foram encontrados 816 artigos nos jornais brasileiros e apenas 29 nos jornais britânicos. No entanto, a grande maioria dos artigos não discutem as causas do desmatamento. A representação das causas diretas do desmatamento é extremamente similar nos dois países sendo soja e pecuária os principais fatores apontados pela mídia. Entretanto, os fatores secundários são tratados diferentemente, sendo que a mídia brasileira mostra como principal fator a necessidade de desenvolvimento econômico. Por outro lado, o papel da demanda internacional da soja, carne e produtos florestais como causas do desmatamento foi bastante discutida na mídia inglesa. Os resultados destas representações em relação a influência que a mídia exerce no entendimento do desmatamento da Amazônia são discutidos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: desmatamento, globalização, Amazônia, mídia

INTRODUCTION

The Amazon region contains the largest remaining area of continuous rainforest in the world and is considered a vital component in maintaining global ecosystem services (sensu Constanza et al. 1998) such as hydrological and chemical cycles that have potential impacts on the World’s climate system (Chahine 1992; Cox et al. 2001; Werth and Avissar 2002). The Amazon rainforest is also the region with most biodiversity on the planet and may contain vast reserves of yet undiscovered species, especially among poorly known taxa such as arthropods (Erwin 1982). The enormous size of Amazonia and its role as a receptacle for much of the Earth’s terrestrial biodiversity makes the forest a legitimate source of global concern, a fact that has led to a widespread but unsubstantiated belief among many Brazilians that the rest of world is plotting the internationalization of the Amazon region for the benefit of humanity and future generations (Fearnside 2003). Brazilian politicians are also sensitive to these issues, which is not surprising when social surveys report findings such as: three out of four adults in Brazilian Amazonia believe that "foreigners are trying to take over the Amazon" (Barbosa 1996). These views, however emotive, are in direct opposition to one of the guiding principles of the Convention on Biological Diversity that explicitly identifies nation states as the rightful stewards and beneficiaries of the biodiversity and associated natural resources within their state borders (UN Convention on Biological Diversity, Rio de Janeiro 1992). Both imagined and apparent arguments about internationalization have recently been highlighted with the realization that large tropical forests may have a key role in controlling mega scale climate regimes (Phillips et al. 1998), and avoiding deforestation may therefore be an important countermeasure against global climate change (Fearnside 2001a).

In the last decade the most expedient way to convert (through deforestation) rainforest in the Brazilian Amazon into tangible economic assets has been through the development of agribusinesses such as cattle ranching and, more recently, soya production (Fearnside 2001b). The transport infrastructure associated with these businesses further promotes the development of legal and illegal logging and the expansion of the agricultural frontier into largely pristine rainforest (Margulis 2004). More roads facilitate the movement of people into previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited regions of the forest (Fearnside 2005), which in turn results in more fires (Nepstad et al. 1999). Underlying these proximate reasons for deforestation is the political necessity for development and economic growth, plus a variety of external drivers such as increasing international demand, especially from the EU and China, for non-genetically modified soya products (Fearnside 2001b) and cheap beef (Margulis 2004). The net result is the continuing deforestation of the Amazon region, especially in the States of Pará and Mato Grosso where soya production has undergone the most rapid expansion. Since the 1980s the rate of deforestation of the Amazon rainforest has been between 18,000 and 30,000 km2 per year with recorded highs in 1994/5 and 2003/4 (Margulis 2004).

The multiple and complex proximate and ultimate factors responsible for driving Amazonian deforestation have made it especially difficult for the global news media to create a clear and simple narrative for their readers. This complexity of causality also provides considerable scope for politically and culturally motivated editorial interpretation that reflects the underlying values of the readership or proprietors (Ladle et al. 2005). For example, is the role of globalization as a driver of Amazonian deforestation more apparent in the media discourse of the producer or the consumer countries? Here, the proposition is tested that the coverage of deforestation of the Amazon will be different in the Brazilian print media from that of an economically developed country (the UK) in a way that reflects the differences in perceived costs and benefits of Amazonian conservation and development to the citizens within these countries. In the UK, it is predicted that stories highlighting the global issues such as the cost of future climate change and biodiversity loss (stemming from the poor local governance of natural resources in the Amazon) should predominate over articles stressing the need for economic development in this region of Brazil. Conversely, the Brazilian news media is predicted to emphasize the necessity of balancing development with conservation, and highlight the pernicious influence of globalization in driving deforestation.

METHODS

The global news-media search engine Lexis-Nexis™ (http://web.lexis-nexis.com) was used to search major national newspapers in the UK and Brazil for articles on deforestation published between January 2000 and December 2005. For both searches the following keywords were used: "Deforestation" (Portuguese - "desmatamento") and Amazon (Portuguese - "Amazônia") connected by the Boolean operator "AND". All relevant articles (primary news articles, editorials, and letters) were included in the subsequent analysis. An identical additional search was also conducted using the online archives for two of Brazil’s most popular newspapers, O Globo and Folha de São Paulo. This latter search was made because Lexis-Nexis™ subscribes to a limited number of Brazilian newspapers and it was considered important to ensure that a representative sample of Brazilian news articles on deforestation was sampled.

The presence/absence of the following thematic information about each article was collected: 1) the proximate causes of deforestation grouped into the following sub-categories: logging (selective and clear-felling), mining and associated extractive industries, soya production, beef cattle ranching, and fire. 2) The ultimate causes of deforestation grouped into the following sub-categories: infrastructural development (e.g. new roads), international demand for agricultural products, necessity for economic development, poor governance (corruption and weak environmental policy), perverse subsidies (sensu Myers 1998) to developed world agribusinesses, population pressure, and international debt.

The above categories are by no means comprehensive but were chosen to reflect the major areas of concern as highlighted in the academic literature (e.g. Margulis 2004; Fearnside 2005). A qualitative textual analysis on all of the articles was also performed to identify the main themes and narratives running through the media discourse that might not be apparent in the quantitative analysis outlined above.

RESULTS

There is considerably more coverage of deforestation issues in the Brazilian news media than in UK newspapers. The Lexis-Nexis™ search resulted in the recovery of 81 newspaper articles in total. 52 of these articles were from Brazilian newspapers and 29 were from the UK press. In addition, a total of 764 articles were found with a deforestation theme published in the two major Brazilian newspapers O Globo (304) and Folha de São Paulo (460). It should be noted that, even though a huge number of articles from Brazilian newspapers were collected, this result still underestimates the relative amounts of coverage of deforestation in the two countries because the sample of Brazilian newspapers is incomplete (in contrast to the UK sample). It is hoped, however, that by combining the information from Lexis-Nexis™ with that gained from O Globo and Folha de São Paulo, the analysis provides an accurate and balanced representation of the ongoing media discourse within the two countries on Amazonian deforestation.

Thematic analysis

Both the Brazilian and the UK news media identified soya production as the main proximate cause of deforestation, followed by logging (selective and clear-felling) and beef cattle ranching (Figure 1). This is unsurprising given the rapid recent growth of the soya industry in Brazil and the interest that this has engendered from both economic institutions and environmental groups. Almost identical patterns of representation of proximate factors were found in the UK and Brazilian press (Figure 1), and suggest that the coverage of these issues may reflect their relative importance in driving deforestation. What is perhaps more interesting is that a much greater frequency of articles from the UK press identified these proximate causes of deforestation, implying a greater interest in apportioning blame (or at least causation). This is neatly illustrated in the following typical headline from The Herald on May 20th 2005: "Amazon forest loses area the size of Wales: loggers and soybean farmers blamed".

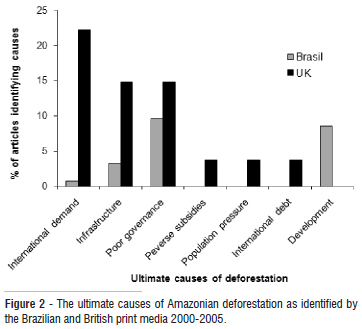

The ultimate causes of Amazonian deforestation as represented in the Brazilian and British print media did not conform to expectations (Figure 2). The argument that international (mainly EU and China) demand for Brazilian soya and beef is an important driver of increasing economic development, and therefore encroachment of agribusiness into pristine rainforest, was found predominantly in the UK press (Figure 2). The same was true of the representation of the related arguments that perverse subsidies and international debt create an economic environment where environmentally unsustainable practices are encouraged. Once again these arguments mainly appeared in a very small minority of UK articles, and were virtually absent in the Brazilian press. Brazilian newspapers had a much greater emphasis on the necessity for economic development, lack of good governance, and the development of the economic infrastructure (particularly roads) that accompanies wide-scale growth of agribusinesses such as soya farming.

DISCUSSION

The plight of the Amazon rainforest illustrates the prime dilemma facing environmentalists around the world - how to develop economically while sustaining biodiversity at levels that maintain ecological integrity and ecosystem services (Constanza et al. 1998). Unfortunately, this is not a simple message for politicians or the news media to communicate, however well informed they may be. Of course, since it is not the media’s role to educate, but to inform (and entertain), there is no reason why balanced (or even accurate) press coverage should be expected (Ladle 2004).

The survey revealed that there were distinct differences between the representations of Amazonian deforestation in the British and the Brazilian print news media. Contrary to the initial predictions, however, it was the UK news media that highlighted the role of globalization in creating a demand for Brazilian agricultural products as the main proximate causes of forest clearance. The Brazilian news media generally showed far less interest in the external drivers of deforestation (Figure 3) and instead was much more tightly focused on internal drivers such as economic development and the effectiveness or otherwise of national or local environmental policies. For example, population pressure, international debt and perverse subsidies were not identified as causal factors underlying Amazonian deforestation in the Brazilian media. In the case of population pressure this is particularly interesting since several administrations have made repeated and well publicized attempts to encourage migration to this part of Brazil (Fearnside 1984) and there is a clear and well publicized relationship between higher populations, more roads, and the increasing profitability of converting forest to agriculture (Cropper et al. 1999)

It could be argued that the above trends are reflective of the Brazilian press being far less "crisis" driven (Bendix and Liebler 1991) than their UK counterparts. Generally, Amazonian deforestation was only covered in the UK media when there had been a new scientific report published that outlined the latest rates of forest loss. Furthermore, British media reporting of deforestation in the Amazon was dominated with quotes from the employees of Environmental NGO’s and advocacy groups whereas there was much greater representation of the views of public officials in the Brazilian media. It is also possible that the Brazilian media may be reluctant to critically comment on issues such as uncontrolled population growth in a country that is predominantly catholic.

Another interesting aspect of the UK press coverage was the difficulty many journalists had with expressing the sheer size of the Amazon. Yearly rates of deforestation were compared to the size of Wales, Germany, Poland, Denmark, Austria, Holland, Portugal, Switzerland, Albania and Belgium or some combination of these. There was virtually no mention of the absolute size of the Amazon in these articles or the relatively low proportion that has so far been deforested (Fearnside 2005). The Brazilian media was far less focused on size, possibly because its people are accustomed to the scale of living in South America’s largest nation.

Apart from a few examples in British newspapers (e.g. ‘Death Sentence for the Amazon’ - The Independent January 19th 2001) there were very few obvious cases of the sensationalism that is often associated with other areas of environmental science reporting (Ladle 2004; Ladle et al. 2004). Indeed, the Brazilian news media often reported deforestation statistics with almost no additional commentary or journalistic interpretation.

One of the most striking findings of the survey is the use of ‘development’ as the prevailing discourse within the Brazilian news media. The need for economic development was frequently identified as an ultimate, and implicitly justifiable, cause of Amazonian deforestation in the Brazilian media. However, with this emphasis there is a danger that the Brazilian media, through frequently framing deforestation as a ‘need’ or a ‘necessity’, is influencing public opinion and legitimizing environmental destruction. Such conformity of representation may also be stifling public debate on important questions such as: are ‘more roads, pasture, and soybean an economic necessity for Brazil?’ The use of terms such as ‘need’ and ‘necessity’ might be more appropriate to describe the objective of feeding a growing population. Take, for example, the ‘need’ for pasture. Brazil may not require more pasture to feed its population, although a few stakeholders would certainly benefit economically from increasing it. In the same way, the expansion of soya has principally been for exportation and the actual production is much greater than that required for consumption (Fearnside 2001b). In this context, ‘development needs’ are arguably being inappropriately emphasized and associated with deforestation by the Brazilian media and this discourse should be replaced by a more balanced representation of the multiple and complex causes of deforestation.

Such media misrepresentation could be attributable to a range of factors: First, newspaper science editors and journalists may lack a grasp of the complex assumptions and extrapolations that support a more complete understanding of Amazonian deforestation. Furthermore, the widespread practice of journalists presenting stories as ‘sound-bites’ may also cause for oversimplification and hyperbole. Moreover, journalists are often working under knowledge and assumptions that lag behind contemporary scientific understandings (Ladle and Gillson 2009). Second, science reporters may be relying too much on secondhand press reports and press releases rather than presenting a more original and nuanced analysis of this complex situation. Equally, researchers, scientific institutions and journals that do research on Amazonian deforestation could take more care in the preparation of press releases, which often act as a source of much hype and simplification in the news media (Rose 2003). Third, it might serve the interests of particular actors in the chain to ‘sex up’ a story, for instance by linking climate change to the imminent threat of mass extinctions (Ladle et al. 2004, 2005). In the current study the Brazilian news media’s emphasis on development appears to closely align with the vested interests of a wealthy and powerful minority of citizens who stand to gain disproportionately from continuing exploitation of the environment.

Ultimately, the different emphases placed on the reporting of Amazonian deforestation may also reflect the ability of the respective readerships to influence events and their personal stake in what happens to the Amazon. For a British citizen it is the potential international consequences of Amazonian deforestation such as climate change and biodiversity loss that personally connects her/him to the statistics reported in the press. In contrast, Brazilian citizens may perceive themselves as having an (indirect) economic stake in the exploitation of Amazonian resources and can influence national environmental policy through voting preference. In reality, this perception of an economic stake, if it exists, may itself have been largely created by the media representations of deforestation. In summary, the respective news media reporting of Amazonian deforestation in these two nations reflects the political and economic spheres of influence within which their readerships operate.

LITERATURE CITED

Barbosa, L.C. 1996. The people of the forest against international capitalism. Sociological Perspectives 39 (2), 317-332.

Bendix, J.; Liebler, C.M. 1991. Environmental degradation in Brazilian Amazonia: Perspectives in US News media. Professional Geographer 43 (4), 474-485.

Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; Raskin, R.G.; Sutton, P.; van den Belt, M. 1998. The value of the World’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Ecological Economics 25 (1), 3-15.

Chahine, M.T. 1992. The hydrological cycle and its influence on climate. Nature 359, 373-380.

Cox, P.M.; Betts, R.A.; Jones, C.D.; Spall, S.A.; Totterdell, I.J. 2001. Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature 408, 184-7.

Cropper, M.; Griffiths, C.; Mani, M. 1999. Roads, Population Pressures, and Deforestation in Thailand, 1976-1989. Land Economics 75 (1), 58-73.

Erwin, T.L. 1982. Tropical forests: Their richness in Coleoptera and other arthropod species. Coleopterists Bulletin 36 (1), 74-75.

Fearnside, P.M. 1984. Brazil’s Amazon settlement schemes. Habitat International 8, 45-61

Fearnside, P.M. 2001a. Saving tropical forests as a global warming countermeasure: an issue that divides the environmental movement. Ecological Economics 39, 167-184.

Fearnside, P.M. 2001b. Soybean cultivation as a threat to the environment in Brazil. Environmental Conservation 28 (1), 23-38.

Fearnside, P.M. 2003. Conservation policy in the Brazilian Amazonia: Understanding the Dilemmas. World Development 31 (5), 757-759.

Fearnside, P.M. 2005. Deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: History, Rates, and Consequences. Conservation Biology 19 (3), 680-688.

Ladle, R.J. 2004. Ecological Science Reporting: Another victim of global warming? British Ecological Society Bulletin 35 (4), 12-13.

Ladle, R.J.; Gillson, L. 2009. The (Im)balance of Nature: A public understanding time-lag? Public Understanding of Science 18 (2), 229-242.

Ladle, R.J.; Jepson, P.; Araujo, M.; Whittaker, R.J. 2004. Dangers of crying wolf over risk of extinctions. Nature 428, 799.

Ladle, R.J.; Jepson, P.; Whittaker, R.J. 2005. Scientists and the Media: the struggle for legitimacy in climate change and conservation science. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 30 (3), 231-240.

Margulis, S. 2004. Causes of deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. World Bank Working Paper No. 22.

Myers, N. 1998. Lifting the veil of perverse subsidies. Nature 392, 327-328.

Nepstad, D.C.; Moreira, A.G.; Alencar, A.A. 1999. Flames in the rain forest: origins, impacts and alternatives to Amazonian fires. The World Bank, Brasilia.

Phillips, O.L.; Malhi, Y.; Higuchi, N.; Laurance, W. F.; Nunez, P.V.; Vasquez, R.M.; Laurance, S.G.; Ferreira, L.V.; Stern, M.; Brown, S.; 1998. Changes in the Carbon BaLance of Tropical Forests: Evidence from Long-Term Plots. Science 5388, 439-441.

Rose, S.P.R 2003. How to (or not to) communicate science. Biochemical Society Transactions 31, 307-312.

Werth, D.; Avissar, R. 2002. The local and global effects of Amazon deforestation. Journal of Geophysical Research 107, NO. D20, 8087.

Recebido em 23/04/2009

Aceito em 19/11/2009

- Barbosa, L.C. 1996. The people of the forest against international capitalism. Sociological Perspectives 39 (2), 317-332.

- Bendix, J.; Liebler, C.M. 1991. Environmental degradation in Brazilian Amazonia: Perspectives in US News media. Professional Geographer 43 (4), 474-485.

- Chahine, M.T. 1992. The hydrological cycle and its influence on climate. Nature 359, 373-380.

- Cox, P.M.; Betts, R.A.; Jones, C.D.; Spall, S.A.; Totterdell, I.J. 2001. Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature 408, 184-7.

- Cropper, M.; Griffiths, C.; Mani, M. 1999. Roads, Population Pressures, and Deforestation in Thailand, 1976-1989. Land Economics 75 (1), 58-73.

- Erwin, T.L. 1982. Tropical forests: Their richness in Coleoptera and other arthropod species. Coleopterists Bulletin 36 (1), 74-75.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2001a. Saving tropical forests as a global warming countermeasure: an issue that divides the environmental movement. Ecological Economics 39, 167-184.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2001b. Soybean cultivation as a threat to the environment in Brazil. Environmental Conservation 28 (1), 23-38.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2003. Conservation policy in the Brazilian Amazonia: Understanding the Dilemmas. World Development 31 (5), 757-759.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2005. Deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: History, Rates, and Consequences. Conservation Biology 19 (3), 680-688.

- Ladle, R.J. 2004. Ecological Science Reporting: Another victim of global warming? British Ecological Society Bulletin 35 (4), 12-13.

- Ladle, R.J.; Gillson, L. 2009. The (Im)balance of Nature: A public understanding time-lag? Public Understanding of Science 18 (2), 229-242.

- Ladle, R.J.; Jepson, P.; Araujo, M.; Whittaker, R.J. 2004. Dangers of crying wolf over risk of extinctions. Nature 428, 799.

- Ladle, R.J.; Jepson, P.; Whittaker, R.J. 2005. Scientists and the Media: the struggle for legitimacy in climate change and conservation science. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 30 (3), 231-240.

- Margulis, S. 2004. Causes of deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon World Bank Working Paper No. 22.

- Myers, N. 1998. Lifting the veil of perverse subsidies. Nature 392, 327-328.

- Nepstad, D.C.; Moreira, A.G.; Alencar, A.A. 1999. Flames in the rain forest: origins, impacts and alternatives to Amazonian fires The World Bank, Brasilia.

- Phillips, O.L.; Malhi, Y.; Higuchi, N.; Laurance, W. F.; Nunez, P.V.; Vasquez, R.M.; Laurance, S.G.; Ferreira, L.V.; Stern, M.; Brown, S.; 1998. Changes in the Carbon BaLance of Tropical Forests: Evidence from Long-Term Plots. Science 5388, 439-441.

- Rose, S.P.R 2003. How to (or not to) communicate science. Biochemical Society Transactions 31, 307-312.

- Werth, D.; Avissar, R. 2002. The local and global effects of Amazon deforestation. Journal of Geophysical Research 107, NO. D20, 8087.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

19 Aug 2010 -

Date of issue

2010

History

-

Received

23 Apr 2009 -

Accepted

19 Nov 2009