Epidemiological context and importance of hypertension in pediatrics

Arterial hypertension was identified as the major source of combined mortality and morbidity, representing 7% of global disability-adjusted life years.11 Sanz J, Moreno PR, Fuster V. The year in atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(13):1131-43. The adoption of the BP definitions and normalization of the "National High Blood Pressure Education Program" (NHBPEP) 200422 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. has standardized the BP classification in the pediatric population. The percentage of children and adolescents diagnosed with AH is estimated to have doubled in the past two decades. The current prevalence of AH in the pediatric population is around 3% to 5%,33 Sinaiko AR, Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ. Prevalence of "significant" hypertension in junior high school-aged children: the Children and Adolescent Blood Pressure Program. J Pediatr. 1989;114(4 Pt 1):664-9

4 Fixler DE, Laird WP, Fitzgerald V, Stead S, Adams R. Hypertension screening in schools: results of the Dallas study. Pediatrics. 1979;63(1):32-6.-55 Sorof JM, Lai D, Turner J, Poffenbarger T, Portman RJ. Overweight, ethnicity, and the prevalence of hypertension in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):475-82. while that of PH reaches 10% to 15%,33 Sinaiko AR, Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ. Prevalence of "significant" hypertension in junior high school-aged children: the Children and Adolescent Blood Pressure Program. J Pediatr. 1989;114(4 Pt 1):664-9,44 Fixler DE, Laird WP, Fitzgerald V, Stead S, Adams R. Hypertension screening in schools: results of the Dallas study. Pediatrics. 1979;63(1):32-6.,66 McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, Franco KD, Sorof JM, Portman RJ. Prevalence of hypertension and prehypertension among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150(6):640-4.,77 Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F. High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1488-96. and such values are mainly attributed to the large increase in childhood obesity.88 Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2107-13. The etiology of pediatric AH can be either secondary, most often associated with nephropathies, or primary, attributed to genetic causes with environmental influence, predominating in adolescents.

Pediatric AH is usually asymptomatic, but as many as 40% of hypertensive children have LVH at the initial diagnosis of AH. Although oligosymptomatic in childhood, LVH is a precursor of arrhythmias and HF in adults.99 Brady TM, Redwine KM, Flynn JT; American Society of Pediatric Nephrology. Screening blood pressure measurement in children: are we saving lives? Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):947-50. In addition, pediatric AH is associated with the development of other changes in target organs, such as increased carotid IMT, arterial compliance reduction, and retinal arteriolar narrowing. Early diagnosis and treatment of childhood AH are associated with a lower risk for AH and for increased carotid atheromatosis in adult life.1010 Laitinen TT, Pahkala K, Magnussen CG, Viikari JS, Oikonen M, Taittonen L, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health in childhood and cardiometabolic outcomes in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2012;125(16):1971-8. Therefore, periodical BP measurements in children and adolescents are recommended, even contradicting the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's suggestion, which considers the evidence of benefits of primary AH screening in asymptomatic children and adolescents insufficient to prevent CVD in childhood or adulthood.1111 Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for primary hypertension in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):613-9.

Definitions and diagnosis

Definition and etiology

Children and adolescents are considered hypertensive when SBP and/or DBP are greater than or equal to the 95th percentile for age, sex and height percentile, on at least three different occasions.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. Prehypertension in children is defined as SBP/DBP ≥ the 90th percentile < the 95th percentile, and in adolescents as BP levels ≥ 120/80 mm Hg and < the 95th percentile. Stage 1 AH is considered for readings between the 95th percentile and the 99th percentile plus 5 mm Hg, while stage 2 AH, for readings > stage 1. The height percentiles can be obtained by using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) growth charts.1212 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Washington (DC): National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. (Vital and Health Statistics, 11(246). [Internet]. [Cited in 2015 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000growthchart-us.pdf

http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000grow...

In addition, normal and high BP levels for children and adolescents are available in mobile apps, such as PA Kids and Ped(z).

In the pediatric population, WCH and MH can be diagnosed based on established normality criteria for ABPM.1313 Flynn JT, Daniels SR, Hayman LL, Maahs DM, McCrindle BW, Mitsnefes M, et al; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension and Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2014;63(5):1116-35.

After a detailed clinical history and physical examination, children and adolescents considered hypertensive should undergo investigation. The younger the child, the greater the chance of secondary AH. Parenchymal, renovascular and obstructive nephropathies account for approximately 60-90% of the cases, and can affect all age groups (infants, children and adolescents), being more prevalent in younger children with higher BP elevations. Endocrine disorders, such as excessive mineralocorticoid, corticoid or catecholamine secretion, thyroid diseases and hypercalcemia associated with hyperparathyroidism, account for approximately 5% of secondary AH cases. Coarctation of the aorta is diagnosed in 2% of the cases, and 5% of secondary AH cases are attributed to other etiologies, such as adverse effects of vasoactive and immunosuppressive drugs, steroid abuse, central nervous system changes, and increased intracranial pressure.

Primary AH is more prevalent in overweight or obese children and adolescents with family history of AH. Currently, primary AH seems to be the most common form of AH in adolescence, being, however, a diagnosis of exclusion, and, in that population, secondary causes should be investigated whenever possible.

Diagnosis

Method for BP measurement

Measuring BP in children is recommended at every clinical assessment after the age of 3 years, abiding by the standards for BP measurement.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. Children under the age of 3 years should have their BP assessed on specific situations.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76.,1414 Lurbe E, Cifkova R, Cruickshank JK, Dillon MJ, Ferreira I, Invitti C, et al; European Society of Hypertension. Management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents: recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1719-42. For BP measurement, children should be calm and sitting for at least 5 minutes, with back supported and feet on the floor, having refrained from consuming stimulant foods and beverages. The BP should be taken at heart level on the right arm, because of the possibility of coarctation of the aorta. Table 1 shows the specific recommendations for auscultatory BP measurement in children and adolescents. Whenever BP is high on the upper limbs, SBP should be assessed on the lower limbs. Such assessment can be performed with the patient lying down, with the cuff placed on the calf, covering at least two-thirds of the knee-ankle distance. The SBP reading on the leg can be higher than that on the arm because of the distal pulse amplification phenomenon. A lower SBP reading on the leg as compared to that on the arm suggests coarctation of the aorta.

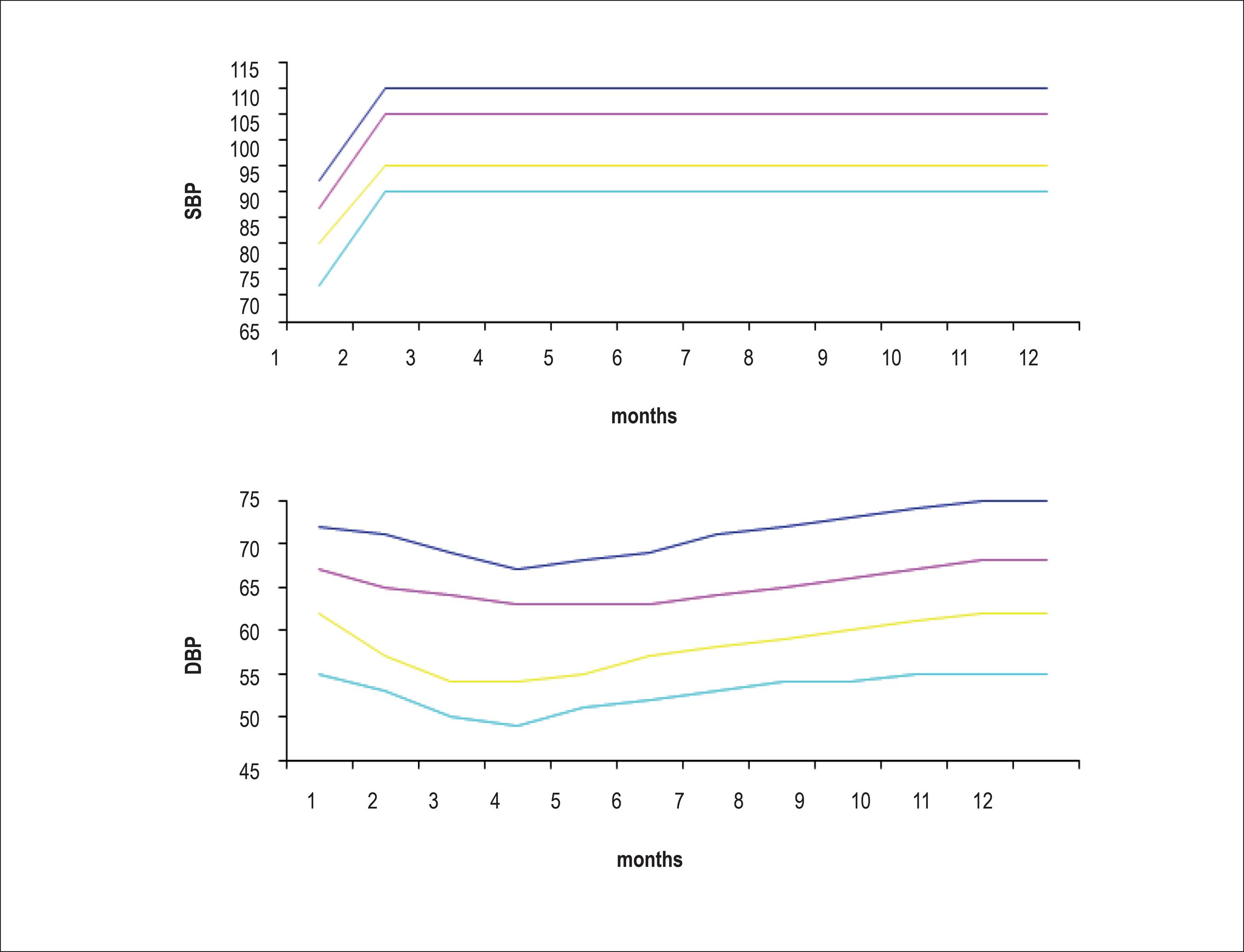

Tables 2 and 3 show the BP percentiles by sex, age and height percentile. Figures 1 and 2 show BP values for boys and girls, respectively, from birth to the age of 1 year based on data from the Report of the Second Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children - 1987.1515 Report of the Second Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children - 1987. Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland. Pediatrics. 1987;79(1):1-25.

Blood pressure levels for boys by age and height percentile22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76.

Note: Adolescents with BP ≥ 120/80 mm Hg should be considered prehypertensive, even if the 90th percentile value is greater than that. This can occur for SBP in patients older than 12 years, and for DBP in patients older than 16 years.

For children/adolescents, ABPM is indicated to investigate WCH and MH, and to follow prehypertensive or hypertensive patients up.1313 Flynn JT, Daniels SR, Hayman LL, Maahs DM, McCrindle BW, Mitsnefes M, et al; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension and Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2014;63(5):1116-35. The prevalence of WCH has been reported as between 22% and 32%. The use of ABPM should be restricted to patients with borderline or mild AH, because patients with high office BP readings are more likely to be hypertensive.1616 Sorof JM, Poffenbarger T, Franco K, Portman R. Evaluation of white coat hypertension in children: Importance of the definitions of normal ambulatory blood pressure and the severity of casual hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(9 Pt 1):855-60.

Anamnesis

A careful recollection of data on birth, growth and development, personal antecedents, and renal, urological, endocrine, cardiac and neurological diseases should be performed. The following patterns should be characterized: physical activity; dietary intake; smoking habit and alcohol consumption; use of steroids, amphetamines, sympathomimetic drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, contraceptives and illicit substances; and sleep history, because sleep disorders are associated with AH, overweight and obesity. In addition, family antecedents for AH, kidney diseases and other CVRF should be carefully assessed.

Physical examination

On physical examination, BMI should be calculated.1717 Guimarães IC, Almeida AM, Santos AS, Barbosa DB, Guimarães AC. Blood pressure: effect of body mass index and of waist circumference on adolescents. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2008;90(6):426-32. Growth delay might suggest chronic disease, and persistent tachycardia might suggest hyperthyroidism or pheochromocytoma. Pulse decrease on the lower limbs leads to the suspicion of coarctation of the aorta. Adenoid hypertrophy is associated with sleep disorders. Acantosis nigricans suggests insulin resistance and DM. Abdominal fremitus and murmurs can indicate renovascular disease.1818 Daniels Sr. Coronary risk factors in children. In: Moss & Adams. Heart disease in infants, children and adolescents. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 2013. p. 1514-48.

Complementary tests

Laboratory and imaging tests are aimed at defining the etiology of AH (primary or secondary) and detecting TOD and CVRF associated with AH (Tables 4 and 5).22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76.,1414 Lurbe E, Cifkova R, Cruickshank JK, Dillon MJ, Ferreira I, Invitti C, et al; European Society of Hypertension. Management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents: recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1719-42.

Target-organ assessment should be performed in all children and adolescents with stage 1 and 2 AH. Sleep study by use of polysomnography or home respiratory polygraphy is indicated for children and adolescents with sleep disorders detected on anamnesis.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. To investigate secondary AH, see Chapter 12.

Table 5 shows some tests for children and adolescents suspected of having secondary AH.

Therapeutic aspects

In children and adolescents with confirmed AH, therapeutic management is guided by the AH etiology definition, CV risk assessment, and TOD characterization.

Nonpharmacological management

Nonpharmacological management should be introduced to all pediatric patients with BP levels above the 90th percentile.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. (GR: IIa; LE: C). It includes body weight loss, a physical exercise program, and dietary intervention.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. Body weight reduction yields good results in the treatment of obese hypertensive children,1919 Hansen HS, Hyldebrandt N, Froberg K, Nielsen JR. Blood pressure and physical fitness in a population of children-the Odense Schoolchild Study. J Hum Hypertens. 1990;4(6):615-20. similarly to physical exercise, which has better effect on SBP levels.1919 Hansen HS, Hyldebrandt N, Froberg K, Nielsen JR. Blood pressure and physical fitness in a population of children-the Odense Schoolchild Study. J Hum Hypertens. 1990;4(6):615-20. Regular aerobic activity is recommended as follows: moderate-intensity physical exercise, 30-60 minutes/day, if possible, every day. Children with AH can practice resistance or localized training, except for weight lifting. Competitive sports are not recommended for patients with uncontrolled stage 2 AH.2020 McCambridge TM, Benjamin HJ, Brenner JS, Cappetta CT, Demorest RA, Gregory AJ, et al; Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Athletic participation by children and adolescents who have systemic hypertension Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1287-94. Dietary intervention can comprise sodium restriction,2121 Gillum RF, Elmer PJ, Prineas RJ. Changing sodium intake in children: the Minneapolis Children's Blood Pressure Study. Hypertension. 1981;3(6):698-703. and potassium and calcium supplementation; the efficacy in that population, however, is yet to be proven.2222 Miller JZ, Wienberger MH, Christian JC. Blood pressure response to potassium supplement in normotensive adults and children. Hypertension. 1987;10(4):437-42.

Pharmacological management

Pharmacological therapy should be initiated for children with symptomatic AH, secondary AH, presence of TOD, types 1 and 2 DM, CKD and persistent AH nonresponsive to nonpharmacological therapy.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. (GR: IIa; LE: B). The treatment is aimed at BP reduction below the 95th percentile in non-complicated AH, and BP reduction below the 90th percentile in both complicated AH, characterized by TOD and comorbidities (DM, CKD), and secondary AH.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. (GR: IIa; LE: C). The treatment should begin with a first-line antihypertensive agent, whose dose should be optimized, and, if target BP level is not attained, other pharmacological groups should be added in sequence. A recent systematic review2323 Chaturvedi S, Lipszyc DH, Licht C, Craig JC, Parekh P. Pharmacological interventions for hypertension in children. Evid Based Child Health. 2014;9(3):498-580. has identified neither a randomized study assessing the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs on TOD, nor any consistent dose-response relationship with any drug class assessed.

The adverse events associated with the use of antihypertensive agents for children and adolescents have been usually of mild intensity, such as headache, dizziness, and upper respiratory tract infections. All classes of antihypertensive drugs seem safe, at least in the short run.2323 Chaturvedi S, Lipszyc DH, Licht C, Craig JC, Parekh P. Pharmacological interventions for hypertension in children. Evid Based Child Health. 2014;9(3):498-580. The only randomized, double-blind, controlled study, by Schaefer et al., comparing the efficacy and safety of drugs of parallel groups and assessing hypertensive children on enalapril or valsartan, has shown comparable results regarding the efficacy and safety of both drugs.2424 Schaefer F, Litwin M, Zachwieja J, Zurowska A, Turi S, Grosso A, et al. Efficacy and safety of valsartan compared to enalapril in hypertensive children: a 12-week, randomized, double blind, parallel-group study. J Hypertens. 2011;29(12):2484-90.

In secondary AH, the antihypertensive drug choice should be in consonance with the pathophysiological principle involved, considering the comorbidities present. For example, non-cardioselective BBs should be avoided in individuals with upper airway reactivity, because of the risk for bronchospasm.2525 Prichard BN, Cruickshank JM, Graham BR. Beta-adrenergic blocking drugs in the treatment of hypertension. Blood Press. 2001;10(5-6):366-86. In pregnancy, ACEIs and ARBs are contraindicated, because of their potential for fetal malformation.2626 Bullo M, Tschumi S, Bucher BS, Bianchetti MG, Simonetti GD. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):444-50. The use of those drugs for childbearing-age girls should be always accompanied by contraceptive guidance.2626 Bullo M, Tschumi S, Bucher BS, Bianchetti MG, Simonetti GD. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):444-50.,2727 Ferguson MA, Flynn JT. Rational use of antihypertensive medications in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):979-88.

For renovascular AH, of ACEIs or ARBs are indicated in association with vasodilators and DIUs. In cases of coarctation of the aorta, in the preoperative period, the initial drug is usually a BB. If the AH persists postoperatively, the BB can be maintained, replaced or associated with an ACEI or ARB. For AH associated with DM and CKD, an ACEI or ARB is initially used. The use of ACEI and ARB relaxes the efferent arteriole, reducing the glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure, and posing a risk for AKI in situations of hypovolemia. Similarly, those drugs are contraindicated for patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis.2626 Bullo M, Tschumi S, Bucher BS, Bianchetti MG, Simonetti GD. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):444-50.

27 Ferguson MA, Flynn JT. Rational use of antihypertensive medications in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):979-88.

28 Blowey DL Update on the pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in pediatrics. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(6):383-7.-2929 Simonetti GD, Rizzi M, Donadini R, Bianchetti MG. Effect of antihypertensive drugs on blood pressure and proteinuria in childhood. J Hypertens. 2007;25(12):2370-6. For obese adults, ACEIs, ARBs, CCBs, BBs and DIUs are effective in reducing BP.3030 Allcock DM, Sowers JR. Best strategies for hypertension management in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10(2):139-44. In adults, ACEIs and ARBs seem to reduce the risk of developing DM and to increase insulin sensitivity.3131 Prabhakar SS Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system: implications for diabetes control and prevention. J Investig Med. 2013;61(3):551-7.

32 Sharma AM. Does it matter how blood pressure is lowered in patients with metabolic risk factors? J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2(4 Suppl):S23-9.-3333 Murakami K, Wada J, Ogawa D, Horiguchi CS, Miyoshi T, Sasaki M, et al. The effects of telmisartan treatment on the abdominal fat depot in patients with metabolic syndrome and essential hypertension: Abdominal fat Depot Intervention Program of Okayama (ADIPO). Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013;10(1):93-6. Erratum in: Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013;10(6):554.

Table 6 shows the updated pediatric doses of the most frequently prescribed hypotensive agents to treat CAH.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76.,2727 Ferguson MA, Flynn JT. Rational use of antihypertensive medications in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):979-88.,2828 Blowey DL Update on the pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in pediatrics. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(6):383-7.

Hypertensive crisis

Hypertensive emergency is characterized by acute BP elevation associated with TOD, which can comprise neurological, renal, ocular and hepatic impairment or myocardial failure, and manifests as encephalopathy, convulsions, visual changes, abnormal electrocardiographic or echocardiographic findings, and renal or hepatic failure.3434 Yang WC, Zhao LL, Chen CY, Wu YK, Chang YJ, Wu HP. First-attack pediatric hypertensive crisis presenting to the pediatric emergency department. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:200. Hypertensive urgency is described as BP elevation above the 99th percentile plus 5 mm Hg (stage 2), associated with less severe symptoms, in a patient at risk for progressive TOD, with no evidence of recent impairment. Oral drugs are suggested, under monitoring, with BP reduction in 24-48 hours.22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76. In HE, the BP reduction should occur slowly and progressively: 30% reduction in the programed amount in 6-12 hours, 30% in 24 hours, and final adjustment in 2-4 days.3535 Adelman RD, Coppo R, Dillon MJ. The emergency management of severe hypertension. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(5):422-7. Very rapid BP reduction is contraindicated, because it leads to hypotension, failure of self-regulating mechanisms, and likelihood of cerebral and visceral ischemia.3636 Deal JE, Barratt TM, Dillon MJ. Management of hypertensive emergencies. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:1089-92 The HE should be treated exclusively with parenteral drugs. In Brazil, the most frequently used drug for that purpose is SNP, which is metabolized into cyanide, which can cause metabolic acidosis, mental confusion, and clinical deterioration. Thus, SNP administration for more than 24 hours requires monitoring of serum cyanide levels, especially in patients with renal failure.3535 Adelman RD, Coppo R, Dillon MJ. The emergency management of severe hypertension. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(5):422-7.,3636 Deal JE, Barratt TM, Dillon MJ. Management of hypertensive emergencies. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:1089-92 After patient's stabilization with SNP, an oral antihypertensive agent should be initiated, so that the SNP dose can be reduced. The use of SNP should be avoided in pregnant adolescents and patients with central nervous system hypoperfusion.

Special clinical conditions can be managed with more specific hypotensive agents for the underlying disease. Patients with catecholamine-producing tumors can be initially alpha-blocked with phenoxybenzamine, or prazosin if the former is not available, followed by the careful addition of a BB. After BP control and in the absence of kidney or heart dysfunction, a sodium-rich diet is suggested to expand blood volume, usually reduced by the excess of catecholamines, favoring postoperative BP management and reducing the chance of hypotension. An IV short-acting antihypertensive drug should be used for intraoperative BP control. Furosemide is the first-choice drug for HC caused by fluid overload, for example, in patients with kidney disease, such as acute glomerulonephritis. In case of oliguria/anuria, other antihypertensive drugs can be used concomitantly, and dialysis might be necessary for blood volume control. Arterial hypertension associated with the use of cocaine or amphetamines can be treated with lorazepam or other benzodiazepine, which is usually effective to control restlessness and AH. In the presence of a HE, phentolamine, if available, is the drug of choice, and should be used in combination with lorazepam.3737 Webb T, Shatat I, Miyashita Y. Therapy of acute hypertension in hospitalized children and adolescents. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(4):425-33.

Table 7 shows the most frequently used drugs in pediatric HE.3838 Baracco R, Mattoo TK. Pediatric hypertensive emergencies. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(8):456.,3939 Constantine E, Merritt C. Hypertensive emergencies in children: identification and management of dangerously high blood pressure. Minerva Pediatr. 2009;61(2):175-84.

Major pediatric drugs and doses used to control hypertensive emergency22 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76.,95,96

References

-

1Sanz J, Moreno PR, Fuster V. The year in atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(13):1131-43.

-

2National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-76.

-

3Sinaiko AR, Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ. Prevalence of "significant" hypertension in junior high school-aged children: the Children and Adolescent Blood Pressure Program. J Pediatr. 1989;114(4 Pt 1):664-9

-

4Fixler DE, Laird WP, Fitzgerald V, Stead S, Adams R. Hypertension screening in schools: results of the Dallas study. Pediatrics. 1979;63(1):32-6.

-

5Sorof JM, Lai D, Turner J, Poffenbarger T, Portman RJ. Overweight, ethnicity, and the prevalence of hypertension in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):475-82.

-

6McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, Franco KD, Sorof JM, Portman RJ. Prevalence of hypertension and prehypertension among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150(6):640-4.

-

7Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F. High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1488-96.

-

8Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2107-13.

-

9Brady TM, Redwine KM, Flynn JT; American Society of Pediatric Nephrology. Screening blood pressure measurement in children: are we saving lives? Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):947-50.

-

10Laitinen TT, Pahkala K, Magnussen CG, Viikari JS, Oikonen M, Taittonen L, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health in childhood and cardiometabolic outcomes in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2012;125(16):1971-8.

-

11Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for primary hypertension in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):613-9.

-

122000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Washington (DC): National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. (Vital and Health Statistics, 11(246). [Internet]. [Cited in 2015 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000growthchart-us.pdf

» http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000growthchart-us.pdf -

13Flynn JT, Daniels SR, Hayman LL, Maahs DM, McCrindle BW, Mitsnefes M, et al; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension and Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2014;63(5):1116-35.

-

14Lurbe E, Cifkova R, Cruickshank JK, Dillon MJ, Ferreira I, Invitti C, et al; European Society of Hypertension. Management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents: recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1719-42.

-

15Report of the Second Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children - 1987. Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland. Pediatrics. 1987;79(1):1-25.

-

16Sorof JM, Poffenbarger T, Franco K, Portman R. Evaluation of white coat hypertension in children: Importance of the definitions of normal ambulatory blood pressure and the severity of casual hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(9 Pt 1):855-60.

-

17Guimarães IC, Almeida AM, Santos AS, Barbosa DB, Guimarães AC. Blood pressure: effect of body mass index and of waist circumference on adolescents. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2008;90(6):426-32.

-

18Daniels Sr. Coronary risk factors in children. In: Moss & Adams. Heart disease in infants, children and adolescents. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 2013. p. 1514-48.

-

19Hansen HS, Hyldebrandt N, Froberg K, Nielsen JR. Blood pressure and physical fitness in a population of children-the Odense Schoolchild Study. J Hum Hypertens. 1990;4(6):615-20.

-

20McCambridge TM, Benjamin HJ, Brenner JS, Cappetta CT, Demorest RA, Gregory AJ, et al; Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Athletic participation by children and adolescents who have systemic hypertension Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1287-94.

-

21Gillum RF, Elmer PJ, Prineas RJ. Changing sodium intake in children: the Minneapolis Children's Blood Pressure Study. Hypertension. 1981;3(6):698-703.

-

22Miller JZ, Wienberger MH, Christian JC. Blood pressure response to potassium supplement in normotensive adults and children. Hypertension. 1987;10(4):437-42.

-

23Chaturvedi S, Lipszyc DH, Licht C, Craig JC, Parekh P. Pharmacological interventions for hypertension in children. Evid Based Child Health. 2014;9(3):498-580.

-

24Schaefer F, Litwin M, Zachwieja J, Zurowska A, Turi S, Grosso A, et al. Efficacy and safety of valsartan compared to enalapril in hypertensive children: a 12-week, randomized, double blind, parallel-group study. J Hypertens. 2011;29(12):2484-90.

-

25Prichard BN, Cruickshank JM, Graham BR. Beta-adrenergic blocking drugs in the treatment of hypertension. Blood Press. 2001;10(5-6):366-86.

-

26Bullo M, Tschumi S, Bucher BS, Bianchetti MG, Simonetti GD. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):444-50.

-

27Ferguson MA, Flynn JT. Rational use of antihypertensive medications in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):979-88.

-

28Blowey DL Update on the pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in pediatrics. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(6):383-7.

-

29Simonetti GD, Rizzi M, Donadini R, Bianchetti MG. Effect of antihypertensive drugs on blood pressure and proteinuria in childhood. J Hypertens. 2007;25(12):2370-6.

-

30Allcock DM, Sowers JR. Best strategies for hypertension management in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10(2):139-44.

-

31Prabhakar SS Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system: implications for diabetes control and prevention. J Investig Med. 2013;61(3):551-7.

-

32Sharma AM. Does it matter how blood pressure is lowered in patients with metabolic risk factors? J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2(4 Suppl):S23-9.

-

33Murakami K, Wada J, Ogawa D, Horiguchi CS, Miyoshi T, Sasaki M, et al. The effects of telmisartan treatment on the abdominal fat depot in patients with metabolic syndrome and essential hypertension: Abdominal fat Depot Intervention Program of Okayama (ADIPO). Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013;10(1):93-6. Erratum in: Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013;10(6):554.

-

34Yang WC, Zhao LL, Chen CY, Wu YK, Chang YJ, Wu HP. First-attack pediatric hypertensive crisis presenting to the pediatric emergency department. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:200.

-

35Adelman RD, Coppo R, Dillon MJ. The emergency management of severe hypertension. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(5):422-7.

-

36Deal JE, Barratt TM, Dillon MJ. Management of hypertensive emergencies. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:1089-92

-

37Webb T, Shatat I, Miyashita Y. Therapy of acute hypertension in hospitalized children and adolescents. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(4):425-33.

-

38Baracco R, Mattoo TK. Pediatric hypertensive emergencies. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(8):456.

-

39Constantine E, Merritt C. Hypertensive emergencies in children: identification and management of dangerously high blood pressure. Minerva Pediatr. 2009;61(2):175-84.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Sept 2016