Abstract

Background:

The cardiovascular risk burden among diverse indigenous populations is not totally known and may be influenced by lifestyle changes related to the urbanization process.

Objectives:

To investigate the cardiovascular (CV) mortality profile of indigenous populations during a rapid urbanization process largely influenced by governmental infrastructure interventions in Northeast Brazil.

Methods:

We assessed the mortality of indigenous populations (≥ 30 y/o) from 2007 to 2011 in Northeast Brazil (Bahia and Pernambuco states). Cardiovascular mortality was considered if the cause of death was in the ICD-10 CV disease group or if registered as sudden death. The indigenous populations were then divided into two groups according to the degree of urbanization based on anthropological criteria:99 Marques J. Cultura material e etnicidade dos povos indígenas do são francisco afetados por barragens: um estudo de caso dos Tuxá de Rodelas, Bahia, Brasil. [Tese]. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2008.,1010 Tomáz A, Chaves CE, Teixeira E, Barros J, Marques J, Schillaci M, et al. (orgs). Relatório de denúncia: povos indígenas do nordeste impactados com a transposição do Rio São Francisco. Salvador: APOINME - Articulação dos Povos e Organizações Indígenas do Nordeste. Minas Gerais e Espírito Santo; AATR - Associação de Advogados dos Trabalhadores Rurais no Estado da Bahia; NECTAS/UNEB - Núcleo de Estudos em Comunidades e Povos Tradicionais e Ações Socioambientais; CPP - Conselho Pastoral l dos Pescadores/NE; CIMI - Conselho Indigenista Missionário; 2012. Group 1 - less urbanized tribes (Funi-ô, Pankararu, Kiriri, and Pankararé); and Group 2 - more urbanized tribes (Tuxá, Truká, and Tumbalalá). Mortality rates of highly urbanized cities (Petrolina and Juazeiro) in the proximity of indigenous areas were also evaluated. The analysis explored trends in the percentage of CV mortality for each studied population. Statistical significance was established for p value < 0.05.

Results:

There were 1,333 indigenous deaths in tribes of Bahia and Pernambuco (2007-2011): 281 in Group 1 (1.8% of the 2012 group population) and 73 in Group 2 (3.7% of the 2012 group population), CV mortality of 24% and 37%, respectively (p = 0.02). In 2007-2009, there were 133 deaths in Group 1 and 44 in Group 2, CV mortality of 23% and 34%, respectively. In 2009-2010, there were 148 deaths in Group 1 and 29 in Group 2, CV mortality of 25% and 41%, respectively.

Conclusions:

Urbanization appears to influence increases in CV mortality of indigenous peoples living in traditional tribes. Lifestyle and environmental changes due to urbanization added to suboptimal health care may increase CV risk in this population.

Keywords:

Indigenous Population; Cardiovascular Diseases / mortality; Urbanization / trends; Social Change

Resumo

Fundamento:

O risco cardiovascular das diversas comunidades indígenas não está bem estabelecido e pode ser influenciado pelo processo de urbanização a que se submetem esses povos.

Objetivos:

Investigar o perfil da mortalidade cardiovascular (CV) das populações indígenas durante o rápido processo de urbanização altamente influenciado por intervenções governamentais de infraestrutura no Nordeste do Brasil.

Métodos:

Avaliamos a mortalidade de populações indígenas (≥ 30 anos) do Vale do São Francisco (Bahia e Pernambuco) no período de 2007-2011. Considerou-se mortalidade CV se a causa de morte constasse no grupo de doenças CV do CID-10 ou se tivesse sido registrada como morte súbita. As populações indígenas foram divididas em dois grupos conforme o grau de urbanização baseado em critérios antropológicos: Grupo 1 - menos urbanizadas (Funi-ô, Pankararu, Kiriri e Pankararé); e Grupo 2 - mais urbanizadas (Tuxá, Truká e Tumbalalá). Taxas de mortalidade de cidades altamente urbanizadas (Petrolina e Juazeiro) nas proximidades das áreas indígenas foram também avaliadas. A análise explorou tendências na porcentagem de mortalidade CV para cada população estudada. Adotou-se o valor de p < 0,05 como significância estatística.

Resultados:

Houve 1.333 mortes indígenas nas tribos da Bahia e de Pernambuco (2007-2011): 281 no Grupo 1 (1,8% da população de 2012) e 73 no Grupo 2 (3,7% da população de 2012), mortalidade CV de 24% e 37%, respectivamente (p = 0,02). Entre 2007 e 2009, houve 133 mortes no Grupo 1 e 44 no Grupo 2, mortalidade CV de 23% e 34%, respectivamente. Entre 2009 e 2010, houve 148 mortes no Grupo 1 e 29 no Grupo 2, mortalidade CV de 25% e 41%, respectivamente.

Conclusões:

A urbanização parece influenciar os aumentos de mortalidade CV dos povos indígenas vivendo de modo tradicional. Mudanças no estilo de vida e ambientais devidas à urbanização somadas à subótima atenção à saúde podem estar implicadas no aumento do risco CV nos povos indígenas.

Palavras-chave:

População Indígena; Doenças Cardiovasculares / mortalidade; Urbanização / tendências; Mudança Social

Introduction

The urbanization process is a concern in developing countries, as it influences the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and coronary disease.11 Alsheikh-Ali AA, Omar MI, Raal FJ, Rashed W, Hamoui O, Kane A, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor burden in Africa and the Middle East: the Africa Middle East Cardiovascular Epidemiological (ACE) study. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e102830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102830.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.010...

In fact, an early process of lifestyle changes appears to lead to increases in CV risk when rural migrants settle in metropolitan areas.22 Zhao J, Seubsman SA, Sleigh A, Thai Cohort Study Team T. Timing of urbanisation and cardiovascular risks in Thailand: evidence from 51 936 members of the thai cohort study, 2005-2009. J Epidemiol. 2014;24(6):484-93. PMID: 25048513. Moreover, traditional indigenous populations are recognized as in greater risk of CV complications.33 Beard JR, Earnest A, Morgan G, Chan H, Summerhayes R, Dunn TM, et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage and acute coronary events: a spatiotemporal analysis. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):485-92. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181656d7f.

https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e318165...

Diverse infectious diseases caused major health concerns when Europeans initially contacted Native American indigenous populations. Along the years, a shift in indigenous mortality rates has been shown toward chronic diseases affected by lifestyle changes, which varies highly across diverse native populations.44 Arbour L, Asuri S, Whittome B, Polanco F, Hegele RA. The Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease in Canadian and International Aboriginal Populations. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(9):1094-115. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.07.005.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2015.07.0...

5 Tobias M, Blakely T, Matheson D, Rasanathan K, Atkinson J. Changing trends in indigenous inequalities in mortality: lessons from New Zealand. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1711-22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp156.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp156...

-66 Dillon MP, Fortington LV, Akram M, Erbas B, Kohler F. Geographic variation of the incidence rate of lower limb amputation in Australia from 2007-12. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170705.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.017...

In recent years, isolated indigenous people in Brazil still showed low blood pressure that appears to be related to their traditional lifestyle.77 Mancilha-Carvalho JJ, Sousa e Silva NA, Carvalho JV, Lima JA. [Blood pressure in 6 Yanomami villages]. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1991;56(6):477-82. PMID: 1823749.,88 Mancilha-Carvalho Jde J, Souza e Silva NA. The Yanomami Indians in the INTERSALT Study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;80(3):289-300. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003000300005.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003...

Major infrastructural projects may rapidly influence populations in the surrounding areas, often affecting indigenous communities. More recently, the Sao Francisco Valley in Northeast Brazil has been experiencing major changes in infrastructure - particularly regarding construction of large dams and canals - that appear to affect traditional indigenous lifestyle in the area.99 Marques J. Cultura material e etnicidade dos povos indígenas do são francisco afetados por barragens: um estudo de caso dos Tuxá de Rodelas, Bahia, Brasil. [Tese]. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2008.,1010 Tomáz A, Chaves CE, Teixeira E, Barros J, Marques J, Schillaci M, et al. (orgs). Relatório de denúncia: povos indígenas do nordeste impactados com a transposição do Rio São Francisco. Salvador: APOINME - Articulação dos Povos e Organizações Indígenas do Nordeste. Minas Gerais e Espírito Santo; AATR - Associação de Advogados dos Trabalhadores Rurais no Estado da Bahia; NECTAS/UNEB - Núcleo de Estudos em Comunidades e Povos Tradicionais e Ações Socioambientais; CPP - Conselho Pastoral l dos Pescadores/NE; CIMI - Conselho Indigenista Missionário; 2012. It is unclear, however, how the urbanization process has been affecting CV mortality in native indigenous communities over the years.

The Project of Atherosclerosis Among Indigenous populations (PAI) was created to investigate the impact of urbanization on CV diseases among indigenous communities in the Sao Francisco Valley (Northeast Brazil). In this study, we investigate the CV mortality profile of indigenous populations during a rapid urbanization process that was largely influenced by governmental infrastructure interventions in the Sao Francisco Valley. For this purpose, we assessed longitudinal data on mortality rates of indigenous and non-indigenous populations in different degrees of urbanization.

Methods

Study population

We assessed data for indigenous mortality in the Sao Francisco Valley, Northeast Brazil (states of Bahia and Pernambuco) between 2007 and 2011, excluding deaths under the age of 30 years. We also assessed the total population in the Sao Francisco Valley according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

The indigenous populations were then divided into two groups according to the degree of urbanization based on previous anthropological evaluations:99 Marques J. Cultura material e etnicidade dos povos indígenas do são francisco afetados por barragens: um estudo de caso dos Tuxá de Rodelas, Bahia, Brasil. [Tese]. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2008.,1010 Tomáz A, Chaves CE, Teixeira E, Barros J, Marques J, Schillaci M, et al. (orgs). Relatório de denúncia: povos indígenas do nordeste impactados com a transposição do Rio São Francisco. Salvador: APOINME - Articulação dos Povos e Organizações Indígenas do Nordeste. Minas Gerais e Espírito Santo; AATR - Associação de Advogados dos Trabalhadores Rurais no Estado da Bahia; NECTAS/UNEB - Núcleo de Estudos em Comunidades e Povos Tradicionais e Ações Socioambientais; CPP - Conselho Pastoral l dos Pescadores/NE; CIMI - Conselho Indigenista Missionário; 2012. Group 1 - less urbanized tribes (Funi-ô, Pankararu, Kiriri, and Pankararé); and Group 2 - more urbanized tribes (Tuxá, Truká, and Tumbalalá).

We also assessed the mortality for the total population in two important and highly urbanized cities in the Sao Francisco Valley: Juazeiro and Petrolina. The Sao Francisco Valley University Ethics Committee approved this study.

Mortality data

The Brazilian Indigenous Healthcare Subsystem is currently the responsibility of the Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health, a section of the Ministry of Health, which, since 2007, has implemented a surveillance program regarding mortality.1111 Athias R, Machado M. [Indigenous peoples' health and the implementation of Health Districts in Brazil: critical issues and proposals for a transdisciplinary dialogue]. Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17(2):425-31. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2001000200017.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2001...

,1212 Sousa Mda C, Scatena JH, Santos RV. [The Health Information System for Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (SIASI): design, structure, and functioning]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(4):853-61. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2007000400013.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2007...

Indigenous mortality was assessed from the official records of the Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health. Mortality in the largest cities of the Sao Francisco Valley used the Brazilian Health Ministry registry (DATASUS/TABNET: http://datasus.saude.gov.br/). Mortality was classified according to the ICD-10 groups. Cardiovascular mortality was considered if the cause of death was in the ICD-10 CV disease group or if registered as sudden death.

Statistical analysis

An exploratory analysis was performed to show trends of CV mortality in diverse indigenous populations over time. Trends over the years in CV mortality in adults (≥ 30 y/o) were shown as the percentage of the total deaths at the same age range for total indigenous communities in the Sao Francisco Valley and according to the urbanization group (less urbanized tribes in Group 1, more urbanized tribes in Group 2, and highly urbanized cities). Two Sample Test for Proportions assessed differences in CV mortality rates among indigenous populations. Statistical significance was established if p value < 0.05. STATA 10 was used for computing statistics.

Results

A total of 75,635 people was registered as indigenous in the Special Indigenous Health Districts of Bahia and Pernambuco. Of these, 25,560 were living in the assessed tribes of the Sao Francisco Valley, mostly in the less urbanized Group 1 tribes (Table 1).

Description of indigenous populations in the Sao Francisco River Basin, according to the study groups.

There was a tendency for mortality at a younger age between 2010 and 2011 when compared to 2007-2009 (Figure 1).

Mortality distribution for indigenous communities in the Sao Francisco Valley (Northeast Brazil) according to age groups.

The total of 1,333 deaths was registered for adult indigenous people in the Sao Francisco Valley, 281 deaths (1.8% of the population in 2012) in Group 1 (less urbanized) and 73 deaths (3.7% of the population in 2012) in Group 2 (more urbanized). Between 2007 and 2009, there were 133 deaths in Group 1 and 44 total deaths in Group 2. Between 2009 and 2010, there were 148 total deaths in Group 1 and 29 deaths in Group 2. Table 1 shows the absolute number of deaths in the indigenous people of the Sao Francisco Valley according to the study groups.

The proportion of CV mortality has shown consistent increases along time in the assessed populations. Conversely, CV mortality has shown consistent decreases for the largest cities in the Sao Francisco Valley (Figure 2).

Cardiovascular mortality (≥ 30 y/o) in indigenous and urban populations in the Sao Francisco Valley (Northeast Brazil). Total indigenous refers to total deaths among indigenous populations in the Sao Francisco Valley, Northeast Brazil.

When the degree of urbanization was considered for the entire period of observation, CV mortality rates were 24% and 37% in Group 1 and Group 2, respectively (p = 0.02). We also found a trend toward a steeper increase in Group 2 CV mortality along time, while Group 1 had nearly stable proportions of CV deaths (Figure 3).

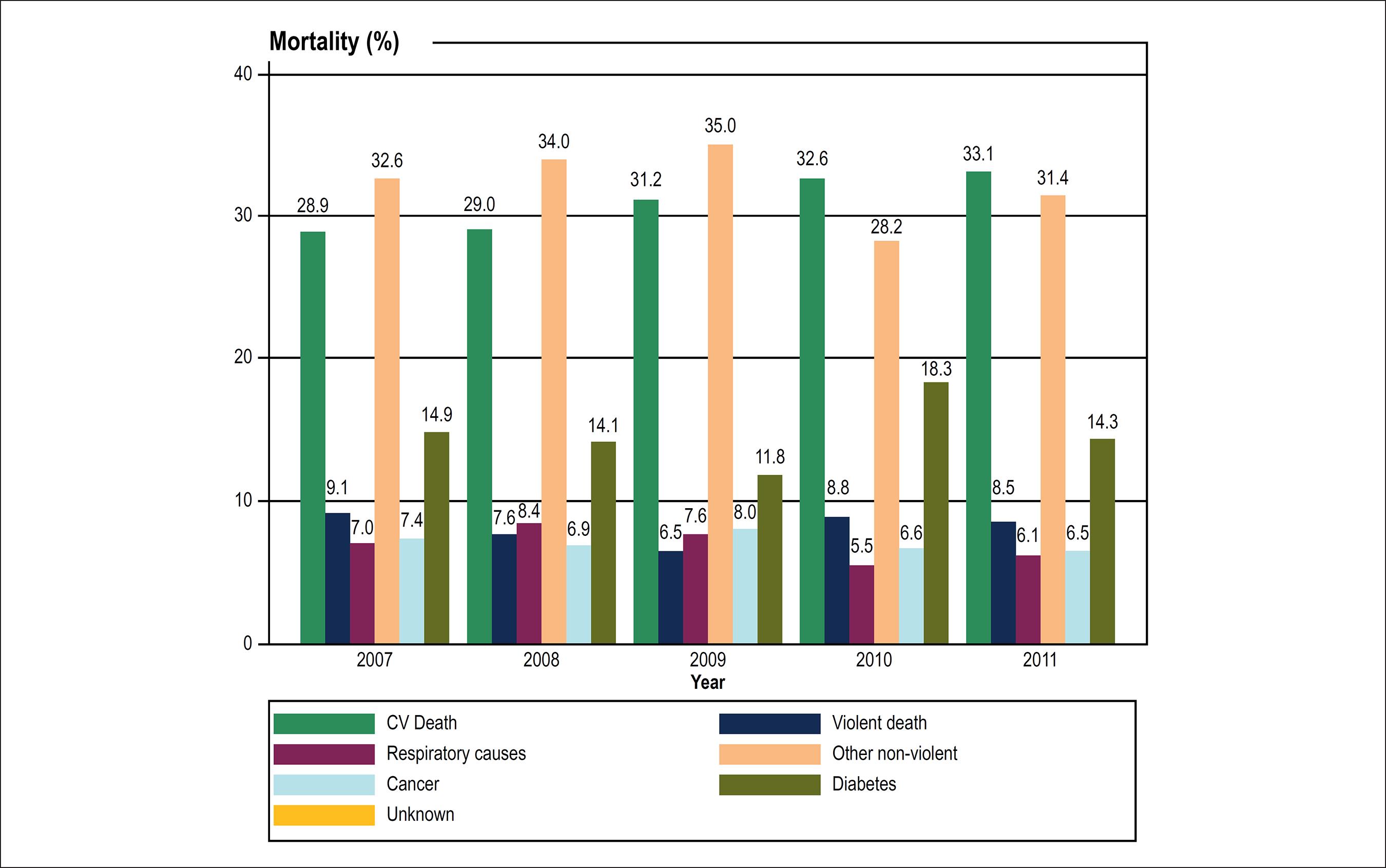

Mortality (≥ 30 y/o) in indigenous populations in the Sao Francisco Valley (Northeast Brazil), according to the degree of urbanization. Group 1 - less urbanized tribes; Group 2 - more urbanized tribes according to anthropological criteria.

Discussion

For the first time in the literature, we show indigenous mortality in the Sao Francisco Valley (Northeast Brazil) tending to a younger age over time, with increasing trends in the proportion of CV deaths. Increases in CV mortality rates in indigenous people living in an area of rapid infrastructural development may indicate that these populations are in harm's way due to changes related to the urbanization process. The knowledge of CV risk and mortality may aid in health policy planning for endangered traditional indigenous populations.

We assessed the available mortality rates - usually a reliable source of information - to explore the indigenous CV burden in Northeast Brazil's Sao Francisco Valley. This area has been through accelerated infrastructural development, such as construction of large canals and dams. Along recent year, hydroelectric power plants have been constructed along the Sao Francisco River, which now the highest concentration of power plants in Brazil.99 Marques J. Cultura material e etnicidade dos povos indígenas do são francisco afetados por barragens: um estudo de caso dos Tuxá de Rodelas, Bahia, Brasil. [Tese]. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2008. Our findings indicate that the traditional indigenous populations affected by a rapid urbanization process are at increased risk of CV mortality.

Urbanization may be related to CV risk beyond ethnicity. In this regard, African Americans have shown higher coronary heart disease mortality rates than Whites, but apparently there are additional disparities according to the urbanization level of the population. The coronary disease-related mortality rates in large metropolitan areas showed a decline over the years in a higher magnitude compared to rural areas.1313 Kulshreshtha A, Goyal A, Dabhadkar K, Veledar E, Vaccarino V. Urban-rural differences in coronary heart disease mortality in the United States: 1999-2009. Public health reports. 2014;129(1):19-29. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900105.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354914129001...

Similar findings have been reported in diverse countries.1414 Okayama A, Ueshima H, Marmot M, Elliott P, Choudhury SR, Kita Y. Generational and regional differences in trends of mortality from ischemic heart disease in Japan from 1969 to 1992. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(12):1191-8. PMID: 11415954.

15 Kruger O, Aase A, Westin S. Ischaemic heart disease mortality among men in Norway: reversal of urban-rural difference between 1966 and 1989. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(3):271-6. PMID: 7629462.-1616 Levin KA, Leyland AH. Urban-rural inequalities in ischemic heart disease in Scotland, 1981-1999. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):145-51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.051193.

https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.051193...

There are few reports on indigenous health in Brazil, but surveys suggest that indigenous people have a less favorable CV risk profile than the general population.1717 Ferreira ME, Matsuo T, Souza RK. [Demographic characteristics and mortality among indigenous peoples in Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(12):2327-39. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2011001200005.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2011...

,1818 Pithan OA, Confalonieri UE, Morgado AF. [The health status of Yanomami Indians: diagnosis from the Casa do Indio, Boa Vista, Roraima, 1987 - 1989]. Cad Saude Publica. 1991;7(4):563-80. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1991000400007

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1991...

Importantly, lifestyle differences related to CV risk are found in closely related traditional communities.1919 Feio CM, Fonseca FA, Rego SS, Feio MN, Elias MC, Costa EA, et al. Lipid profile and cardiovascular risk in two Amazonian populations. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;81(6):596-9, 592-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003001400006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003...

In fact, rapid changes in lifestyle affect indigenous populations differently from people in urban areas.2020 Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Butler MS, Grant CC, Stewart JM, Cave TL, et al. Dietary intake and eating behaviours of obese New Zealand children and adolescents enrolled in a community-based intervention programme. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166996.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.016...

Not only risk factors appear to be increasing among indigenous people; the complications related to health care quality are also alarming. In fact, there is evidence that urbanization directly affects the health care quality of a given area.2121 Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Ahn KO, et al. A trend in epidemiology and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by urbanization level: a nationwide observational study from 2006 to 2010 in South Korea. Resuscitation. 2013;84(5):547-57. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.12.020.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation....

Additionally, socioeconomic disadvantages do not seem to completely explain the increasing CV risk trends in indigenous populations. Regions majorly populated by indigenous people show increased CV risk beyond the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage.33 Beard JR, Earnest A, Morgan G, Chan H, Summerhayes R, Dunn TM, et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage and acute coronary events: a spatiotemporal analysis. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):485-92. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181656d7f.

https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e318165...

,2222 Castro F, Zuniga J, Higuera G, Carrion Donderis M, Gomez B, Motta J. Indigenous ethnicity and low maternal education are associated with delayed diagnosis and mortality in infants with congenital heart defects in Panama. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163168.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.016...

This may be related to difficulties for indigenous populations when interacting with other ethnicities regarding their traditional medicine.2323 Kujawska M, Hilgert NI, Keller HA, Gil G. Medicinal plant diversity and inter-cultural interactions between Indigenous Guarani, Criollos and Polish Migrants in the Subtropics of Argentina. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169373.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.016...

The classic expected dynamics of epidemiology for indigenous people in Brazil was based on two initial steps more closely related to infectious diseases, and a third step of epidemiologic transition and cultural losses. This third period would be characterized by an increase in chronic conditions such as CV disease and the emergence of an epidemiological profile similar to that of non-indigenous communities.2424 Confalonieri UE. O Sistema Único de Saúde e as Populações Indígenas: por uma integração diferenciada. Cad Saude Publica. 1989;5(4):441-50. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1989000400008.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1989...

Our findings suggest that an epidemiological fourth step may be underway, in which the occurrence of CV diseases among indigenous people is not similar to that of the general population, but higher. These findings may be explained by rapid lifestyle and environmental modifications, added to a lower health care quality.

Our study had several limitations and should be interpreted in the context of an exploratory investigation. Furthermore, we were limited to assessing the increases in the profile of CV risk factors as we assessed secondary data for mortality. Thus, concerns regarding potential misclassification bias certainly apply. Although large infrastructural changes have historically affected indigenous lifestyles, the magnitude of the deleterious impact of urbanization on the CV risk profile of these groups is not totally clear. Increases in blood pressure, obesity, and glycemic abnormalities are examples of known CV risk factors that may lead to subclinical cardiac abnormalities over time, before a CV event is established.2525 Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, Colangelo LA, Kishi S, Liu K, Sidney S, et al. Association of early adult modifiable cardiovascular risk factors with left atrial size over a 20-year follow-up period: the CARDIA study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e004001. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004001.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004...

26 Kishi S, Gidding SS, Reis JP, Colangelo LA, Venkatesh BA, Armstrong AC, et al. Association of Insulin Resistance and Glycemic Metabolic Abnormalities With LV Structure and Function in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(2):105-114. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.02.033.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.02.0...

-2727 Kishi S, Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, Colangelo LA, Venkatesh BA, Jacobs DR, Jr., et al. Association of obesity in early adulthood and middle age with incipient left ventricular dysfunction and structural remodeling: the CARDIA study (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults). JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(5):500-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.03.001.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.03.0...

Further studies in the context of the PAI project are planned to address early subclinical abnormalities in these populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we show increasing trends in CV mortality over time among indigenous populations in the Sao Francisco Valley (Northeast Brazil), which appear to be negatively affected by a higher degree of urbanization. Lifestyle and environmental changes due to urbanization added to suboptimal health care may be implicated in the increase in CV risk among indigenous people.

-

Sources of FundingThis study was partially funded by CNPq.

-

Study AssociationThis study is not associated with any thesis or dissertation work.

-

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the UNIVASF and CONEP under the protocol number 48235615.9.0000.5196. All the procedures in this study were in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, updated in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

References

-

1Alsheikh-Ali AA, Omar MI, Raal FJ, Rashed W, Hamoui O, Kane A, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor burden in Africa and the Middle East: the Africa Middle East Cardiovascular Epidemiological (ACE) study. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e102830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102830.

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102830 -

2Zhao J, Seubsman SA, Sleigh A, Thai Cohort Study Team T. Timing of urbanisation and cardiovascular risks in Thailand: evidence from 51 936 members of the thai cohort study, 2005-2009. J Epidemiol. 2014;24(6):484-93. PMID: 25048513.

-

3Beard JR, Earnest A, Morgan G, Chan H, Summerhayes R, Dunn TM, et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage and acute coronary events: a spatiotemporal analysis. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):485-92. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181656d7f.

» https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181656d7f -

4Arbour L, Asuri S, Whittome B, Polanco F, Hegele RA. The Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease in Canadian and International Aboriginal Populations. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(9):1094-115. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.07.005.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2015.07.005 -

5Tobias M, Blakely T, Matheson D, Rasanathan K, Atkinson J. Changing trends in indigenous inequalities in mortality: lessons from New Zealand. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1711-22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp156.

» https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp156 -

6Dillon MP, Fortington LV, Akram M, Erbas B, Kohler F. Geographic variation of the incidence rate of lower limb amputation in Australia from 2007-12. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170705.

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170705 -

7Mancilha-Carvalho JJ, Sousa e Silva NA, Carvalho JV, Lima JA. [Blood pressure in 6 Yanomami villages]. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1991;56(6):477-82. PMID: 1823749.

-

8Mancilha-Carvalho Jde J, Souza e Silva NA. The Yanomami Indians in the INTERSALT Study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;80(3):289-300. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003000300005

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003000300005 -

9Marques J. Cultura material e etnicidade dos povos indígenas do são francisco afetados por barragens: um estudo de caso dos Tuxá de Rodelas, Bahia, Brasil. [Tese]. Salvador: Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2008.

-

10Tomáz A, Chaves CE, Teixeira E, Barros J, Marques J, Schillaci M, et al. (orgs). Relatório de denúncia: povos indígenas do nordeste impactados com a transposição do Rio São Francisco. Salvador: APOINME - Articulação dos Povos e Organizações Indígenas do Nordeste. Minas Gerais e Espírito Santo; AATR - Associação de Advogados dos Trabalhadores Rurais no Estado da Bahia; NECTAS/UNEB - Núcleo de Estudos em Comunidades e Povos Tradicionais e Ações Socioambientais; CPP - Conselho Pastoral l dos Pescadores/NE; CIMI - Conselho Indigenista Missionário; 2012.

-

11Athias R, Machado M. [Indigenous peoples' health and the implementation of Health Districts in Brazil: critical issues and proposals for a transdisciplinary dialogue]. Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17(2):425-31. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2001000200017

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2001000200017 -

12Sousa Mda C, Scatena JH, Santos RV. [The Health Information System for Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (SIASI): design, structure, and functioning]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(4):853-61. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2007000400013

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2007000400013 -

13Kulshreshtha A, Goyal A, Dabhadkar K, Veledar E, Vaccarino V. Urban-rural differences in coronary heart disease mortality in the United States: 1999-2009. Public health reports. 2014;129(1):19-29. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900105.

» https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491412900105 -

14Okayama A, Ueshima H, Marmot M, Elliott P, Choudhury SR, Kita Y. Generational and regional differences in trends of mortality from ischemic heart disease in Japan from 1969 to 1992. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(12):1191-8. PMID: 11415954.

-

15Kruger O, Aase A, Westin S. Ischaemic heart disease mortality among men in Norway: reversal of urban-rural difference between 1966 and 1989. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(3):271-6. PMID: 7629462.

-

16Levin KA, Leyland AH. Urban-rural inequalities in ischemic heart disease in Scotland, 1981-1999. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):145-51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.051193.

» https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.051193 -

17Ferreira ME, Matsuo T, Souza RK. [Demographic characteristics and mortality among indigenous peoples in Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(12):2327-39. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2011001200005

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2011001200005 -

18Pithan OA, Confalonieri UE, Morgado AF. [The health status of Yanomami Indians: diagnosis from the Casa do Indio, Boa Vista, Roraima, 1987 - 1989]. Cad Saude Publica. 1991;7(4):563-80. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1991000400007

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1991000400007 -

19Feio CM, Fonseca FA, Rego SS, Feio MN, Elias MC, Costa EA, et al. Lipid profile and cardiovascular risk in two Amazonian populations. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;81(6):596-9, 592-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003001400006

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2003001400006 -

20Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Butler MS, Grant CC, Stewart JM, Cave TL, et al. Dietary intake and eating behaviours of obese New Zealand children and adolescents enrolled in a community-based intervention programme. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166996.

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166996 -

21Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Ahn KO, et al. A trend in epidemiology and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by urbanization level: a nationwide observational study from 2006 to 2010 in South Korea. Resuscitation. 2013;84(5):547-57. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.12.020.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.12.020 -

22Castro F, Zuniga J, Higuera G, Carrion Donderis M, Gomez B, Motta J. Indigenous ethnicity and low maternal education are associated with delayed diagnosis and mortality in infants with congenital heart defects in Panama. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163168.

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163168 -

23Kujawska M, Hilgert NI, Keller HA, Gil G. Medicinal plant diversity and inter-cultural interactions between Indigenous Guarani, Criollos and Polish Migrants in the Subtropics of Argentina. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169373.

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169373 -

24Confalonieri UE. O Sistema Único de Saúde e as Populações Indígenas: por uma integração diferenciada. Cad Saude Publica. 1989;5(4):441-50. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1989000400008

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X1989000400008 -

25Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, Colangelo LA, Kishi S, Liu K, Sidney S, et al. Association of early adult modifiable cardiovascular risk factors with left atrial size over a 20-year follow-up period: the CARDIA study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e004001. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004001.

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004001 -

26Kishi S, Gidding SS, Reis JP, Colangelo LA, Venkatesh BA, Armstrong AC, et al. Association of Insulin Resistance and Glycemic Metabolic Abnormalities With LV Structure and Function in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(2):105-114. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.02.033.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.02.033 -

27Kishi S, Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, Colangelo LA, Venkatesh BA, Jacobs DR, Jr., et al. Association of obesity in early adulthood and middle age with incipient left ventricular dysfunction and structural remodeling: the CARDIA study (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults). JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(5):500-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.03.001.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.03.001

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

19 Feb 2018 -

Date of issue

Mar 2018

History

-

Received

11 May 2017 -

Reviewed

31 July 2017 -

Accepted

22 Sept 2017