| Declaration of potential conflict of interests of authors/collaborators of the Brazilian Guidelines of Hypertension – 2020 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| If, within the last 3 years, the author/collaborator of the guideline: | |||||||

| Names of guideline collaborators | Participated in clinical and/or experimental studies sponsored by pharmaceutical or equipment companies related to this statement | Spoke at events or activities sponsored by industry related to this statement | Was (is) a member of a board of advisors or a board of directors of a pharmaceutical or equipment industry | Participated in normative committees of scientific research sponsored by industry | Received personal or institutional funding from industry | Wrote scientific papers in journals sponsored by industry | Owns stocks in industry |

| Alexandre Alessi | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Alexandre Jorge Gomes de Lucena | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Alvaro Avezum | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ana Luiza Lima Sousa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Andréa Araujo Brandão | No | Abbott, Daiichi Sankyo, EMS, Libbs, Novartis, Medley, Merck, Servier | No | No | Servier | Abbott, Daiichi Sankyo, EMS, Libbs, Novartis, Medley, Merck, Servier | No |

| Andrea Pio-Abreu | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Andrei Carvalho Sposito | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Angela Maria Geraldo Pierin | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Annelise Machado Gomes de Paiva | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Antonio Carlos de Souza Spinelli | No | Merck, Torrent, Boerhinger, Sandoz | No | No | EMS, Aché, Torrent | No | No |

| Armando da Rocha Nogueira | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Audes Diógenes de Magalhães Feitosa | No | EMS, Servier, Sandoz, Merck, Medtronic e Omron | Omron | No | No | EMS, Servier e Omron | No |

| Bruna Eibel | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Carlos Alberto Machado | No | No | Biolab, Omron | No | No | No | No |

| Carlos Eduardo Poli-de-Figueiredo | No | No | No | Fresenius | Centro de Pesquisa Clínico da PUCRS, Baxter, Fresenius, Alexion, AstraZeneca. | No | No |

| Celso Amodeo | No | Novartis, NovoNordisk, EMS, ACHE | Montecorp Farmasa | No | No | ACHE, Montecorp Farmasa | No |

| Cibele Isaac Saad Rodrigues | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cláudia Lúcia de Moraes Forjaz | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Claudia Regina de Oliveira Zanini | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cristiane Bueno de Souza | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Decio Mion Junior | No | Zodiac | No | No | No | Zodiac | No |

| Dilma do Socorro Moraes de Souza | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Eduardo Augusto Fernandes Nilson | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Eduardo Costa Duarte Barbosa | No | Servier, EMS | No | No | No | No | No |

| Elisa Franco de Assis Costa | No | No | No | No | Abbot Nutrition, Nestlé Health Sciences, Aché, Sandoz, Nutricia | Abboot Nutrition | No |

| Elizabete Viana de Freitas | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Elizabeth da Rosa Duarte | No | No | No | No | Sim, Ache, Bayer, Novartis, Torrent, Servier. | No | No |

| Elizabeth Silaid Muxfeldt | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Emilton Lima Júnior | No | Servier, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Biolab, Amgem | No | Servier | No | No | No |

| Erika Maria Gonçalves Campana | No | No | No | No | Servier | Servier | No |

| Evandro José Cesarino | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Fábio Argenta | No | No | No | No | Novartis, Bayer, Torrent, Lilly, Boehringer | No | No |

| Fernanda Marciano Consolim-Colombo | No | Merck, Ache, Daiichi | No | No | Não | No | No |

| Fernanda Spadotto Baptista | No | No | No | No | Não | No | No |

| Fernando Antonio de Almeida | No | No | No | No | Não | No | No |

| Fernando Nobre | No | Libbs, Cristália | No | No | Libbs, Novartis, Servier, Baldacci | Daichi Sankio, Libbs, Novartis, Biolab, Servier, Baldacci | No |

| Flávio Antonio de Oliveira Borelli | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Flávio Danni Fuchs | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Frida Liane Plavnik | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gil Fernando Salles | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gilson Soares Feitosa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Giovanio Vieira da Silva | No | Ache | No | No | No | Ache | No |

| Grazia Guerra | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Heitor Moreno Júnior | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Helius Carlos Finimundi | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Isabel Cristina Britto Guimarães | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Isabela de Carlos Back | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| João Bosco de Oliveira Filho | No | No | No | No | Novartis, Bristol, AztraZeneca | No | No |

| João Roberto Gemelli | No | No | No | No | Boeringher, Libbs | No | Boeringher, Libbs |

| José Fernando Vilela-Martin | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Jose Geraldo Mill | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| José Marcio Ribeiro | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Juan Carlos Yugar-Toledo | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Leda A. Daud Lotaif | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lilian Soares da Costa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lucélia Batista Neves Cunha Magalhães | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Luciano Ferreira Drager | No | Aché, Biolab, Boehringer, Merck | ResMed | No | No | Aché, Biolab, Merck | No |

| Luis Cuadrado Martin | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Luiz Aparecido Bortolotto | No | Servier, Novonordisk | No | No | No | No | No |

| Luiz César Nazário Scala | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Madson Q. Almeida | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Marcia Maria Godoy Gowdak | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Marcia Regina Simas Torres Klein | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Marco Antônio Mota-Gomes | Omron, Beliva | No | Omron, Libbs | No | No | Omron, Libbs | No |

| Marcus Vinícius Bolívar Malachias | No | Libbs, Biolab | No | No | No | Libbs. Biolab | No |

| Maria Cristina Caetano Kuschnir | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Maria Eliane Campos Magalhães | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Maria Eliete Pinheiro | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Mario Fritsch Toros Neves | No | Servier | No | No | No | No | No |

| Mario Henrique Elesbão de Borba | No | EMS | No | No | No | No | No |

| Nelson Dinamarco Ludovico | No | Não | No | No | No | No | No |

| Osni Moreira Filho | No | Biolab, Servier | No | No | No | No | No |

| Oswaldo Passarelli Júnior | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Otávio Rizzi Coelho | No | Daichi-Sankyo, Boehringer | No | Daichi-Sankyo, BAYER, Novo-Nordisk | No | Sanofi, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Daichi-Sankyo, Bayer | No |

| Paulo César Brandão Veiga Jardim | No | Servier, Libbs, EMS | No | No | No | Servier, Libbs | No |

| Priscila Valverde Vitorino | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Renault Mattos Ribeiro Júnior | No | Daiichi Sankyo | No | No | No | No | No |

| Roberto Dischinger Miranda | No | EMS, Boehringher | No | No | No | EMS, Sanofi, Servier | No |

| Roberto Esporcatte | No | EMS | No | No | No | No | No |

| Roberto Franco | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rodrigo Pedrosa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rogerio Andrade Mulinari | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rogério Baumgratz de Paula | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rogerio Toshiro Passos Okawa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ronaldo Fernandes Rosa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rui Manuel dos Santos Póvoa | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Sandra Fuchs | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Sandra Lia do Amaral | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Sebastião R. Ferreira-Filho | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Sergio Emanuel Kaiser | Engage, Alecardio, RED-HF, Odissey-Outcomes, SELECT | Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, astrazeneca, Momenta Farma, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Baldacci | No | No | No | Novartis, Momenta Farma, Farmasa, EMS | No |

| Thiago de Souza Veiga Jardim | No | AstraZeneca, Torrent, Meck, Bayer | No | No | No | No | No |

| Vanildo Guimarães | No | Boehringer, Novartis, Sandoz | No | No | No | No | No |

| Vera H. Koch | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Weimar Kunz Sebba Barroso de Souza | Ministério da Saúde, Sociedade Europeia de Hipertensão Arterial, Artery Society, EMS | EMS, Libbs, Sandoz, Servier, Cardios, Omron | Omron | No | EMS, Servier | EMS, Servier, Omron | No |

| Wille Oigman | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wilson Nadruz | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

List of Abbreviations

| ABI | ankle-brachial index | GBD | global burden diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABPM | ambulatory blood pressure monitoring | GH | growth hormone |

| AC | arm circumference | GRS | global risk score |

| ACEI | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | GST | gait speed test |

| ADL | activity of daily living | HBP | high blood pressure |

| AE | adverse event | HBPM | home blood pressure monitoring |

| AF | atrial fibrillation | HC | hypertensive crisis |

| Aix | augmentation index | HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction | HE | hypertensive emergency |

| APA | aldosterone-producing adenomas | HELPP | hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets |

| APE | acute pulmonary edema | HF | heart failure |

| ARB | angiotensin II AT1 receptor blocker | HFpEF | heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| ASA | acetylsalicylic acid | HFrEF | heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| BB | beta-blockers | HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| BE | blinding effect | HR | heart rate |

| BMI | body mass index | hs-TnT | high-sensitivity troponin T |

| BP | blood pressure | HT | hypertension |

| CAD | coronary artery disease | HTPC | hypertensive pseudocrisis |

| CCB | calcium channel blocker | HU | hypertensive urgency |

| cfPWV | carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity | ICU | intensive care unit |

| CGA | comprehensive geriatric assessment | IGF-1 | insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| CHW | community health worker | IV | intravenous |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease | LE | level of evidence |

| CO | cardiac output | LLs | lower limbs |

| CRP | C-reactive protein | LR | level of recommendation |

| CT | computed tomography | LSC | lifestyle change |

| CV | cardiovascular | MH | masked hypertension |

| CVD | cerebrovascular disease | MNR | magnetic nuclear resonance |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease | MOD | multi-organ damage |

| CVRF | cardiovascular risk factor | MS | metabolic syndrome |

| DALYs | disability-adjusted life years | NB | newborn |

| DBP | diastolic blood pressure | NCD | noncommunicable disease |

| DIU | diuretics | NE | norepinephrine |

| DM | diabetes mellitus | NIHSS | National Institute of Health Stroke Scale |

| EF | ejection fraction | NO | nitric oxide |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate | NOO- | peroxynitrite |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase | NPT | nonpharmacological treatment |

| EOD | end-organ damage | NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide |

| FMD | fibromuscular dysplasia | NTG | nitroglycerin |

| FMD | flow-mediated dilation | OH | orthostatic hypotension |

| OSA | obstructive sleep apnea | RHT | resistant hypertension |

| PE | pre-eclampsia | RVH | renovascular hypertension |

| PEF | preserved ejection fraction | SBP | systolic blood pressure |

| PHEO | pheochromocytoma | SHT | sustained hypertension |

| PNS | Brazilian National Health Survey | SMBP | self-measured blood pressure |

| PNS | parasympathetic nervous system | SNP | sodium nitroprusside |

| POAD | peripheral occlusive atherosclerotic disease | SNS | sympathetic nervous system |

| PPH | postprandial hypotension | SUS | Brazilian Unified Health System |

| PRA | plasma renin activity | T4 | thyroxine |

| PVR | peripheral vascular resistance | TG | triglycerides |

| PWV | pulse wave velocity | TNT | true normotension |

| R/S | religiosity and spirituality | TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| RAAS | renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system | UAOBPM | unobserved automated office blood pressure measurement |

| RAS | renal artery stenosis | UN | United Nations |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial | WCE | white-coat effect |

| REF | reduced ejection fraction | WCH | white coat hypertension |

| RF | risk factors | WHO | World Health Organization |

| RfHT | refractory hypertension | YLL | years of life lost |

Content

1. Definition, Epidemiology, and Primary Prevention 528

1.1 Definition of Hypertension 528

1.2. Impact of Hypertension on Cardiovascular Diseases 528

1.3. Risk Factors for Hypertension 528

1.3.1. Genetics 528

1.3.2. Age 528

1.3.3. Sex 528

1.3.4. Race/Ethnicity 528

1.3.5. Overweight/Obesity 528

1.3.6. Sodium and Potassium Intake 528

1.3.7. Sedentary lifestyle 529

1.3.8. Alcohol 529

1.3.9. Socioeconomic Factors 529

1.3.10. Other Risk Factors for High BP 529

1.3.11. Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) 529

1.3.12. Global Epidemiological Data 529

1.4. Prevalence of Hypertension in Brazil 529

1.5. Primary Prevention 530

1.5.1. Introduction 530

1.5.2. Weight Control (LR: I; LEE: A) 530

1.5.3. Healthy Diet (LR: I; LE: A) 530

1.5.4. Sodium (LR: I; LE: A) 530

1.5.5. Potassium (LR: I; LE: A) 530

1.5.6. Physical Activity (LR: I; LE: A) 530

1.5.7. Alcohol (LR: IIA; LE: B) 531

1.5.8. Psychosocial Factors (LR: IIb; LE: B) 531

1.5.9. Dietary Supplements (LR: I to III; LE: A and B) 531

1.5.10. Smoking (LR: I; LE: A) 531

1.5.11. Spirituality (LR: I; LE: B) 531

1.6. Strategies for the Implementation of Preventive Measures 531

2. Blood Pressure and Vascular Damage 535

2.1. Introduction 535

2.2. Blood Pressure, Clinical Outcomes, and Cardiovascular Damage 535

2.3. Blood Pressure, Inflammation, and Endothelial Dysfunction 536

2.4. Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness 536

2.4.1. Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) 536

2.4.2. Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV) 537

2.4.3. Central Blood Pressure 537

3. Diagnosis and Classification 540

3.1. Introduction 540

3.2. Blood pressure measurement at the physician's office 540

3.3. Classification 540

3.4. Out-of-Office Blood Pressure Measurement 541

3.5. White-Coat Effect (WCE) and Masking Effect (ME) 541

3.6. White Coat Hypertension (WCH) and Masked Hypertension (MH) 541

3.7. Uncontrolled Masked and White Coat Hypertension 541

3.8. Diagnosis and Follow-Up Recommendations 541

3.9. Central Aortic Pressure 542

3.10. Genetics and Hypertension 542

4. Clinical and Complementary Assessment 548

4.1. Clinical History 548

4.2. Clinical Assessment 548

4.2.1. History-Taking 548

4.3. Physical Examination 548

4.3.1. Basic Laboratory Investigation, Assessment of Subclinical and Clinical End-Organ Damage 548

5. Cardiovascular Risk Stratification 552

5.1. Introduction 552

5.2. Additional Risk Stratification (Associated Conditions) 552

5.2.1. End-Organ Damage 553

5.2.2. Presence of Cardiovascular and Renal Disease 553

5.3. Assessment of Global Cardiovascular Risk 553

5.4. Challenges of Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Hypertension 553

6. Therapeutic Decision and Targets 556

6.1. Introduction 556

6.2. Low- or Moderate-Risk Hypertensive Patients 556

6.3. High-Risk Hypertensive Patients 556

6.4. Hypertensive Patients with Coronary Disease 556

6.5. Hypertensive Patients with History of Stroke 556

6.6. Hypertensive Heart Failure Patients 557

6.7. Hypertensive Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) 557

6.8. Diabetic Hypertensive Patients 557

6.9. Older Hypertensive Patients 557

7. Multidisciplinary Team 559

7.1. The Importance of a Multidisciplinary Approach to Hypertension Control 7.2. Team Composition and Work 559

7.2.1. Medical Professional: Specific Actions 559

7.2.2. Nursing Professional: Specific Actions 559

7.2.2.1. Nursing-Specific Actions in Primary Care 559

7.2.3. Nutrition Professional: Specific Actions 560

7.2.3.1. Dietetic Consultation 560

7.2.3.2. Collective Actions by Nutritionists 560

7.2.4. Physical Education Professional: Specific Actions 560

7.2.4.1. Collective Actions by Physical Education and Physical Therapy Professionals 560

7.3. Multidisciplinary Team Actions 561

8. Nonpharmacological Treatment 562

8.1. Introduction 562

8.2. Smoking 562

8.3. Dietary Patterns 562

8.4. Sodium Intake 563

8.5. Potassium 563

8.6. Dairy Products 563

8.7. Chocolate and Cocoa Products 563

8.8. Coffee and Caffeinated Products 563

8.9. Vitamin D 563

8.10. Supplements and Substitutes 564

8.11. Weight Loss 564

8.12. Alcohol Consumption 564

8.13. Physical Activity and Physical Exercise 564

8.14. Slow Breathing 565

8.15. Stress Control 565

8.16. Religiosity and Spirituality 565

9. Pharmacological Treatment 568

9.1. Treatment Objectives 568

9.2. General Principles of Pharmacological Treatment 568

9.3. Therapy Regimens 568

9.3.1. Monotherapy 568

9.3.2. Drug Combinations 568

9.4. General Characteristics of Different Classes of Antihypertensive Medications 569

9.4.1. Diuretics (DIUs) 569

9.4.1.1. Adverse Effects of Diuretics 569

9.4.2. Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs) 569

9.4.2.1. Adverse Effects of Calcium Channel Blockers 570

9.4.3. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs) 570

9.4.3.1. Adverse Effects of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors 9.4.4. Angiotensin II AT1 Receptor Blockers (ARBs) 570

9.4.4.1. Adverse Effects of Angiotensin II AT1 Receptor Blockers 570

9.4.5. Beta-Blockers (BBs) 570

9.4.5.1. Adverse Effects of Beta-Blockers 571

9.4.6. Centrally Acting Sympatholytics 571

9.4.6.1. Adverse Effects of Centrally Acting Sympatholytics 571

9.4.7. Alpha-blockers 571

9.4.7.1. Adverse Effects of Alpha-Blockers 571

9.4.8. Direct-Acting Vasodilators 571

9.4.8.1. Adverse Effects of Direct-Acting Vasodilators 571

9.4.9. Direct Renin Inhibitors 571

9.4.9.1. Adverse Effects of Direct Renin Inhibitors 572

9.5. Antihypertensive Drug Combinations 572

10. Hypertension and Associated Clinical Conditions 578

10.1. Diabetes Mellitus (DM) 578

10.1.1. Treatment Objectives 578

10.2. Metabolic Syndrome (MS) 578

10.3. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) 578

10.4. Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) 578

10.4.1. Patient in Conservative Treatment: Goals and Treatment 578

10.4.2. Patients in Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT): Goals and Treatment 579

10.5. Heart Failure (HF) 579

10.6. Hemorrhagic Stroke and Ischemic Stroke 580

10.6.1. Hemorrhagic Stroke 580

10.6.2. Ischemic Stroke 580

11. Hypertension in Pregnancy 581

11.1. Epidemiology 581

11.2. Classification of Hypertension in Pregnancy 581

11.3. Concept and Diagnostic Criteria 581

11.4. Prediction and prevention of pre-eclampsia 581

11.5. Nonpharmacological treatment 582

11.6. Expectant management 582

11.7. Pharmacological treatment 582

11.8 Future Cardiovascular Risk 583

12. Hypertension in Children and Adolescents 586

12.1. Epidemiological Context and Importance of Hypertension in Pediatrics 586 12.2. Definition and Etiology 586

12.3. Diagnostic 586

12.3.1. BP Measurement Methods 586

12.4. History-Taking 587

12.5. Physical Examination 587

12.7. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM) 587

12.8. Therapeutic Aspects 587

12.9. Nonpharmacological Therapy 587

12.10. Pharmacological Therapy 587

12.11. Follow-up of Children and Adolescents with HT 588

12.12. Hypertensive Crisis 588

13. Hypertensive Crisis 596

13.1. Definition 596

13.2. Classification 596

13.3. Major Epidemiological, Pathophysiological, and Prognostic Aspects 596

13.3.1. Epidemiology 596

13.3.2. Pathophysiology 596

13.3.3. Prognosis 596

13.4. Complementary Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 597

13.5. General Treatment of Hypertensive Crisis 597

13.6. Hypertensive Emergencies in Special Situations 597

13.6.1. Hypertensive Encephalopathy 597

13.7. Stroke 597

13.7.1. Ischemic Stroke 597

13.7.2. Hemorrhagic Stroke 598

13.7.3. Acute Coronary Syndromes 598

13.7.4. Acute Pulmonary Edema (APE) 598

13.7.4.1. Acute Aortic Dissection 598

13.7.5. Pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia 598

13.7.6. HE from Illicit Drug Use 598

13.7.7. Accelerated/Malignant Hypertension 598

13.7.8. Hypertension with Multi-Organ Damage 599

14. Hypertension in Older Adults 602

14.1. Introduction 602

14.2. Physiopathological Mechanisms 602

14.3. Diagnosis and Therapeutic Decision 603

14.4. Treatment 603

14.4.1. Nonpharmacological Treatment 603

14.4.2. Pharmacological Treatment 603

14.5. Special Situations 604

14.5.1. Functional Status and Frailty: Assessment and Implications 604

14.5.2. Cognitive Decline and Dementia 604

14.5.3. Polypharmacy and Adherence 604

14.5.4. Deintensification and Deprescription 605

14.5.5. Orthostatic and Postprandial Hypotension 605

15. Secondary Hypertension 606

15.1. Introduction 606

15.2. Nonendocrine Causes 606

15.2.1. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) 606

15.2.2. Renovascular Hypertension (RVH) 606

15.3. Fibromuscular Dysplasia 607

15.3.1. Coarctation of the Aorta 607

15.3.2. Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) 607

15.3.2.1. Concept and Epidemiology 607

15.3.2.2. Clinical Presentation and Screening of OSA in Hypertension 608

15.3.2.3. Impact of Treatment of OSA on BP 608

15.3.2.4. Antihypertensive Treatment in Hypertensive Patients with OSA 608

15.4. Endocrine Causes 608

15.4.1. Primary Hyperaldosteronism (PH) 608

15.4.2. Pheochromocytoma 609

15.4.3. Hypothyroidism 609

15.4.4. Hyperthyroidism 609

15.4.5. Primary Hyperparathyroidism 609

15.4.6. Cushing's Syndrome 610

15.4.7. Obesity 610 15.4.8. Acromegaly 610 15.5. Pharmacological Causes, Hormones, and Exogenous Substances 610

16. Resistant and Refractory Hypertension 618 16.1. Definition and Classification 618 16.2. Epidemiology of Resistant Hypertension 618 16.3. Pathophysiology 618 16.4. Diagnostic Investigation 618 16.5. Treatment 618 16.5.1. Nonpharmacological Treatment 618 16.5.2. Pharmacological Treatment 619 16.5.3. New Treatments 619

17. Adherence to Antihypertensive Treatment 622

17.1. Introduction 622

17.2. Concept and Adherence 622

17.3. Treatment Adherence Assessment Methods 622

17.4. Factors Interfering in Adherence to Treatment 623

17.5. Strategies to promote adherence to antihypertensive treatment 623

17.6. Conclusion 623

18. Perspectives 625

18.1. Introduction 625

18.2. Definition, Epidemiology, and Primary Prevention 625

18.3. Blood Pressure and Vascular Damage 625

18.4. Cardiac Biomarkers 625

18.5. Diagnosis and Classification 625

18.6. Complementary Assessment and Cardiovascular Risk Stratification 626

18.7. Goals and Treatment 626

Reference 628

1. Definition, Epidemiology, and Primary Prevention

1.1. Definition of Hypertension

Hypertension (HT) is a chronic noncommunicable disease (NCD) defined by blood pressure levels for which the benefits of treatment (nonpharmacological and/or pharmacological) outweigh the risks. HT is a multifactorial condition, depending on genetic/epigenetic, environmental, and social factors ( Figure 1.1 ), characterized by persistent high blood pressure (BP), ie, systolic blood pressure (SBP) equal to or greater than 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) equal to or greater than 90 mm Hg, measured using the appropriate technique, on at least two different occasions, in the absence of antihypertensive medication. When possible, it is advised that these measurements be validated by assessing BP outside the physician's office using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM), or self-measured blood pressure (SMBP) (see Chapter 3).

– Schematic description of major determinants of blood pressure and hypertension and their interactions n adults. Genetic/epigenetic, environmental, and social determinants interact to increase the BP of hypertensive patients and in the general population. ↑increased; ↓decreased.

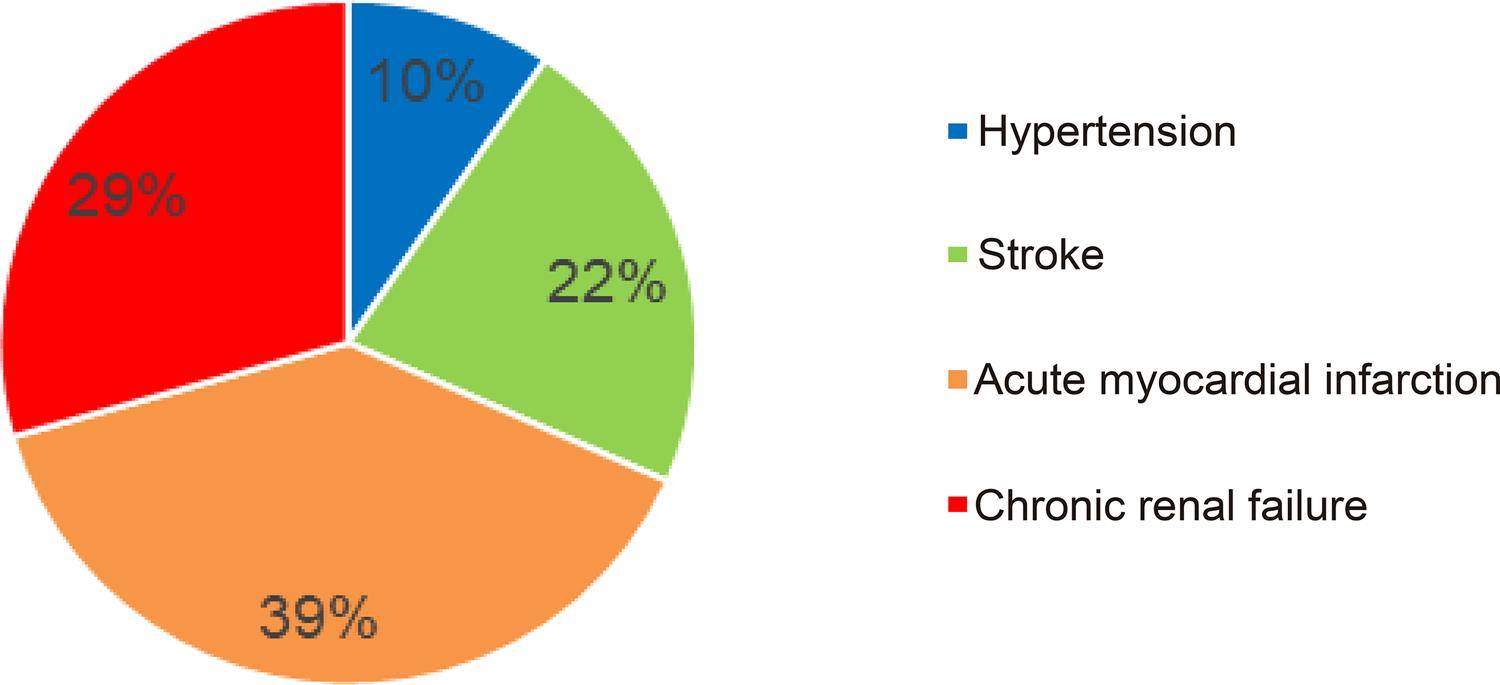

– Percentage of deaths from hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and chronic renal failure (Brazil, 2000).

1.2. Impact of Hypertension on Cardiovascular Diseases

As an often asymptomatic condition, BP usually progresses to structural and/or functional change to end organs, such as the heart, brain, kidneys, and blood vessels. It is the primary modifiable risk factor, independently, linearly, and continuously associated, for cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CVD), and early death. It is associated with metabolic risk factors for cardiocirculatory and renal diseases, such as dyslipidemia, abdominal obesity, glucose intolerance, and diabetes mellitus (DM). 11. Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990–2015. JAMA 2017; 317(2):165-82.

2. Anderson AH. Yang W, Townsend RR, Pan Q, Chertow GM, Kusek JW, et al. Time-updated systolic blood pressure and the progression of chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015; 162(4): 258-65.

3. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.

In addition, it has a significant impact on socioeconomic and medical costs due to fatal and nonfatal complications to end organs, such as: heart: coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation (AF), and sudden death; brain: stroke, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and dementia; kidneys; CKD that may require dialysis therapy; and arterial system: peripheral occlusive atherosclerotic disease (POAD). 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.

1.3. Risk Factors for Hypertension

1.3.1. Genetics

Genetic factors may influence BP levels from 30 to 50%. 77. Menni C, Mangino M, Zhang F, Clement G, Snieder H, Padmanabhan S, et al. Heritability analyses show visit-to-visit blood pressure variability reflects different pathological phenotypes in younger and older adults: evidence from UK twins. J Hypertens. 2013; 31(12):2356-61. However, due to wide genetic diversity, the gene variants we have studied thus far and Brazilian miscigenation, uniform data for this factor have yet to be identified. Further details about the genetic component of HT can be found in Chapter 3.

1.3.2. Age

SBP becomes a more significant problem with age, the result of the progressive hardening and decreased compliance of the great arteries. Approximately 65 percent of people age 60 or older have HT, and we should take into consideration Brazil's ongoing epidemiological transition, with an even greater number of older adults (age ≥ 60) in the coming decades leading to a substantial increase in the prevalence of HT and its complications. 77. Menni C, Mangino M, Zhang F, Clement G, Snieder H, Padmanabhan S, et al. Heritability analyses show visit-to-visit blood pressure variability reflects different pathological phenotypes in younger and older adults: evidence from UK twins. J Hypertens. 2013; 31(12):2356-61.,88. Singh GM, Danaei G, Pelizzari PM, Lin JK, Cowan MJ, Stevens GA, et al. The age associations of blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose: analysis of health examination surveys from international populations. Circulation. 2012;125(18): 2204-11.

1.3.3. Sex

Among younger cohorts, BP is higher in men, but rises faster by decade in women. Therefore, in their sixth decades, women's BP is usually higher than men's, as is the prevalence of HT. For both sexes, the frequency of HT rises with age, reaching 61.5% and 68.0% for men and women age 65 or older, respectively. 77. Menni C, Mangino M, Zhang F, Clement G, Snieder H, Padmanabhan S, et al. Heritability analyses show visit-to-visit blood pressure variability reflects different pathological phenotypes in younger and older adults: evidence from UK twins. J Hypertens. 2013; 31(12):2356-61.

1.3.4. Race/Ethnicity

Race and ethnicity are important risk factors for HT, but socioeconomic status and lifestyle seem to be more relevant for the differing prevalence of HT than race and ethnicity themselves. 77. Menni C, Mangino M, Zhang F, Clement G, Snieder H, Padmanabhan S, et al. Heritability analyses show visit-to-visit blood pressure variability reflects different pathological phenotypes in younger and older adults: evidence from UK twins. J Hypertens. 2013; 31(12):2356-61.,88. Singh GM, Danaei G, Pelizzari PM, Lin JK, Cowan MJ, Stevens GA, et al. The age associations of blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose: analysis of health examination surveys from international populations. Circulation. 2012;125(18): 2204-11. The Vigitel 2018 data show that, in Brazil, there was no significant differences between blacks and whites regarding the prevalence of HT (24.9% versus 24.2%). 99. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. Vigitel Brazil, 2016: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico. Brasília;2016.

1.3.5. Overweight/Obesity

There seems to be a direct, continuous, and almost linear relationship between overweight/obesity and BP levels. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269. Despite decades of unequivocal evidence that waist circumference (CC) provides both independent and additive information to body mass index (BMI) for predicting morbidity and risk of death, this parameter is not routinely measured in clinical practice. It is recommended that health professionals be trained to properly perform this simple measurement and consider it as an important “vital sign” in clinical practice. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.

1.3.6. Sodium and Potassium Intake

High sodium intake has been shown to be a risk factor for high BP and consequently for the greater prevalence of HT. The literature shows that sodium intake is associated with CVD and stroke when mean intake is greater than 2 g of sodium, equivalent to 5 g of table salt. 1010. Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, McQueen M, Dagenais G, Wielgosz A, et al. Urinary sodium excretion, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: a community-level prospective epidemiological cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392(10146):496–506. Sodium excretion studies show that, for those with high sodium intake, SBP was 4,5-6.0 mm Hg higher, and DBP 2.3-2.5 mm Hg higher, than for those at recommended sodium intake levels. 1111. Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, Dyer AR, Stamler R, Kesteloot H, et al. Intersalt revisited: further analyses of 24 hours sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1249-53.

It should also be stressed that excess sodium intake is one of the main modifiable risk factors for preventing and controlling HT and CVD, and that the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) spent USD 102 million in 2013 alone on hospitalizations attributable to excess sodium intake. 1212. Mill JG, Malta DC, Machado ÍE, Pate A, Pereira CA, Jaime PC, et al. Estimativa do consumo de sal pela população Brazileira: resultado da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019;22(suppl 2):E190009. [Citado em 2020 Mar 10]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v22s2/1980-5497-rbepid-22-s2-e190009-supl-2.pdf .

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v22s2/19...

Conversely, increased sodium intake reduces blood pressure levels. It is worth highlighting that the effects of potassium supplementation seems to be greater for those with high sodium intake and for black people. Mean salt intake in Brazil is 9.3 g/day (9.63 g/day for men and 9.08 g/day for women), while potassium intake is 2.7 g/day for men and 2.1 g/day for women. 1212. Mill JG, Malta DC, Machado ÍE, Pate A, Pereira CA, Jaime PC, et al. Estimativa do consumo de sal pela população Brazileira: resultado da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019;22(suppl 2):E190009. [Citado em 2020 Mar 10]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v22s2/1980-5497-rbepid-22-s2-e190009-supl-2.pdf .

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v22s2/19...

,1313. Araujo MC, Bezerra IN, Barbosa F dos S, Junger WL, Yokoo EM, Pereira RA, et al. Consumo de macronutrientes e ingestão inadequada de micronutrientes em adultos. Rev Saude Publica [Internet]. 2013;47(Supl.1):1775–895. [Acesso em 10 de mar 2020]. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102013000700004 .

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102013...

1.3.7. Sedentary lifestyle

There is a direct association between a sedentary lifestyle, high BP, and HT. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269. It should be noted that, globally in 2018, the rate of lack of physical activity (less than 150 minutes of physical activity per week or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity per week) was 27.5%, with greater prevalence among women (31.7%) than men (23.4%). 1414. Guthold R, Stevens, GA, Riley, LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health. 2018;6(10):e1077-e1086.

In Brazil, the 2019 Vigitel phone survey found that 44.8% of adults did not perform sufficient levels of physical activity, and rates were worse for women (52.2%) than for men (36,1%). 99. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. Vigitel Brazil, 2016: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico. Brasília;2016.

1.3.8. Alcohol

The impact of alcohol intake has been investigated in various epidemiological studies. There is greater prevalence of HT or high blood pressure levels for those taking six or more doses per day, equivalent to 30 g of alcohol/day = 1 bottle of beer (5% alcohol, 600 mL); = 2 glasses of wine (12% alcohol, 250 mL); = 1 dose (42% alcohol, 60 mL) of distilled beverages (whiskey, vodka, spirits). That threshold should be cut in half for low-weight men and for women. 1515. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Tobe SW, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Rehm J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(2):e108–e120.,1616. Fuchs FD, Chambless LE, Whelton PK, Nieto FJ, Heiss G. Alcohol consumption and the incidence of hypertension: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Hypertension. 2001;37(5):1242–50.

1.3.9. Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic factors include lower educational levels, inadequate living conditions, and low family income as significant risk factors for HT. 1717. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50.,1818. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):37-55.

1.3.10. Other Risk Factors for High BP

In addition to the classic factors listed above, it is important to stress that some medications, often acquired without prescription, have the potential to promote high BP or make it harder to control, as do illicit drugs. The subject will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 15. These include monoamine oxidase inhibitors and sympathomimetic, such as decongestants (phenylephrine), tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine and others), thyroid hormones, oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, carbenoxolone and liquorice, glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, erythropoietin, and illicit drugs (cocaine, cannabis, amphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)). 55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,1919. Plavnik FL. Hipertensão arterial induzida por drogas: como detectar e tratar. Rev Bras Hipertens. 2002; 9:185-91.

1.3.11. Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

There is clear evidence behind the relation between OSA and HT and increased risk of resistant HT (see also Chapter 15). Mild, moderate, and severe OSA has a dose-response relationship with HT. There is a stronger association for Caucasian and male patients with OSA. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,2020. Ahmad M, Makati D, Akbar S. Review of and Updates on Hypertension in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Int J Hypertens. 2017; 2017:1848375. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1848375 .

https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1848375...

1.3.12. Global Epidemiological Data

CVD are the main cause of death, hospitalization, and outpatient medical visits worldwide, including developing countries such as Brazil. 2121. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980- 2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study . Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151-210. In 2017, complete and revised data from Datasus showed a total of 1 312 663 deaths, 27.3% of which from CVD. 2222. 2017. Lancet. 2016;390:1151–210. Causes of Death 2008 [online database]. Geneva, World Health Organization. [Cited in 2020 Mar 10] Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/cod_2008_sources_methods.pdf

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_bur...

HT was associated with 45% of cardiac deaths (CAD and HF), 51.0% of deaths from cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and a small percentage of deaths directly related to HT (13.0%). It should be stressed that HT kills more by causing end-organ damage 2323. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS/MS/SVS/CGIAE - Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade SIM. [Acesso em 19 de abr 2020]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sim/cnv/obt10uf.def/2017-CID 10-Capitulos I00-I99; http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf.def .

http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi....

( Figure 1.2 ).

In 2017, data from Global Burden of Disease (GBD) indicated that CVD accounted for 28.8% of total deaths from noncommunicable diseases (NCD). The GBD study found that there were almost 18 million deaths from CV causes in 2017 (31.8% of total deaths), accounting for 20.6% of total years of life lost (YLL) and 14,7% total DALYs (disability-adjusted life years, ie, years of healthy life lost). 1818. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):37-55.,2121. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980- 2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study . Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151-210.

Also according to GBD, SBP increase was found to be the main risk factor, responsible for 10.4 million deaths and 218 million DALYs. 2121. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980- 2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study . Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151-210. It also accounts for approximately 40.0% of deaths of DM patients, 14.0% of maternal and fetal mortality during pregnancy, and 14.7% of total DALYs from CKD. 2424. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PFA. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet.2006;367(9516):1066-74.

25. Udani S, Lazich I, Bakris GL. Epidemiology of hypertensive kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(1):11-21.-2626. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS. Sistema de Informações Hospitalares do SUS(SIH/SUS). {Internet} Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sih/cnv/nruf.def/2008-2018/ CID 10-Capitulos I00 I99; http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf.def . Acessado em 19/03/2020.

http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi....

Globally, in 2010, HT prevalence (≥140/90 mm Hg and/or use of antihypertensive medication) was 31.0%, higher for men (31.9%) than for women (30.1%). 1717. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50.,1818. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):37-55.

A study on worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015 assessing 19.1 million adults found that, in 2015, there was an estimated 1.13 billion adults with HT (597 million men and 529 million women), suggesting a 90% increase in the number of people with HT, especially in low- and medium-income countries. 1717. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50.,1818. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):37-55. The study found that HT prevalence decreased in high-income countries and some medium-income ones, but increased or held steady in lower-income nations. The factors implicated in that increase are likely population aging and greater exposure to other risk factors, such as high sodium and low potassium intake, in addition to sedentary lifestyles. 1717. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50.,1818. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):37-55.

1.4. Prevalence of Hypertension in Brazil

Countrywide prevalence data tend to vary according to the methodology and sample chosen. According to the 2013 Brazilian National Health Survey, 21.4% (95% CI 20.8-22.0) of Brazilian adults self-report HT, while BP readings and the use of antihypertensive medications indicate that the share of adults with BP at or above 140/90 mm Hg is approximately 32.3% (95% CI 31.7-33.0). HT prevalence was found to be higher among men and, as expected, to increase with age regardless of other parameters, reaching 71.7% for individuals age 70 and older ( Table 1.1 and Figure 1.3 ). 2727. Malta DC, Gonçalves RPF, Machado IE, Freitas MIF, Azeredo C, Szwarcwald CL et al. Prevalência da hipertensão arterial segundo diferentes critérios diagnósticos. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2018; 21(sup 1): E180021.

In 2017, there was a total of 1 312 663 deaths, 27.3% of which from CVD, accounting for 22.6% of all early deaths in Brazil (ages 30 to 69). In one ten-year period (2008 through 2017), it is estimated that 667 184 could be attributed to HT in Brazil. 2121. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980- 2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study . Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151-210.

22. 2017. Lancet. 2016;390:1151–210. Causes of Death 2008 [online database]. Geneva, World Health Organization. [Cited in 2020 Mar 10] Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/cod_2008_sources_methods.pdf

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_bur...

-2323. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS/MS/SVS/CGIAE - Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade SIM. [Acesso em 19 de abr 2020]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sim/cnv/obt10uf.def/2017-CID 10-Capitulos I00-I99; http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf.def .

http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi....

In the death rate per 100 000 inhabitants from 2000 to 2018, we can see a slight uptick in AMI and a jump in direct HT, with 25% and 128% increases, respectively. 2323. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS/MS/SVS/CGIAE - Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade SIM. [Acesso em 19 de abr 2020]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sim/cnv/obt10uf.def/2017-CID 10-Capitulos I00-I99; http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf.def .

http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi....

As for morbidity, we can see the population-adjusted hospitalization trend has been stable over the last ten years (Datasus Hospitalization System) both for all causes and for CVD ( Figure 1.3 ). 55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,2323. Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS/MS/SVS/CGIAE - Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade SIM. [Acesso em 19 de abr 2020]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sim/cnv/obt10uf.def/2017-CID 10-Capitulos I00-I99; http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/poptuf.def .

http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi....

More of the Brazilian health system's costs can be attributed to HT than to obesity and DM. In 2018, it is estimated that SUS spent USD 523.7 million in hospitalizations, outpatient procedures, and medications. 2828. Nilson EAF, Andrade RCS, Brito DA, Oliveira ML. Custos atribuíveis à obesidade, hipertensão e diabetes no Sistema Único de Saúde em 2018. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e32.

Over the last decade, CVD associated with HT account for 77% of the Brazilian Unified Health System's (SUS) hospitalization costs from CAD, and they increased 32% from 2010 to 2019 in Brazilian reais, from R$ 1.6 billion to R$ 2.2 billion over the same period. 2828. Nilson EAF, Andrade RCS, Brito DA, Oliveira ML. Custos atribuíveis à obesidade, hipertensão e diabetes no Sistema Único de Saúde em 2018. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e32.,2929. EAF, Silva EN, Jaime PC. Developing and applying a costing tool for hypertension and related cardiovascular disease: attributable costs to salt/sodium consumption. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22(4):642-8.

1.5. Primary Prevention

1.5.1. Introduction

HT is highly prevalent and a major risk factor for CVD and kidney disease, combining genetic, environmental, and social determinants. It is easily diagnosable and effectively treatable by a diverse and highly efficiency therapeutic arsenal with few adverse effects. Even so, globally, the fact that it is an often asymptomatic disease means adherence to care is difficult and it remains mostly uncontrolled worldwide.

That equation makes treatment extremely challenging, and prevention remains the best option from a cost-benefit perspective. An adequate approach to risk factors for HT should be a major point of focus for SUS (the Brazilian Unified Health System). Several aspects of that issue deserve further consideration. Many are interwoven or ad to nonpharmacological treatment ( Chart 1.1 ), detailed in Chapter 8. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.,55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,3030. Dickey RA, Janick JJ. Lifestyle modifications in the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Endocr Pract. 2001; 7 (5):392-9.,3131. Perumareddi P. Prevention of hypertension related to cardiovascular disease. Prim Care. 2019;46(1):27-39.

1.5.2. Weight Control (LR: I; LEE: A)

Overall and central obesity are associated with increased risk of HT. On the other hand, weight loss promoted lower BP both for normotensive and for hypertensive individuals. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.,55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269. Being “as lean as possible” within the normal BMI range may be the best suggestion for primary prevention of HT. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.,55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,3232. Jiang SZ, Lu W, Zong XF, Ruan HY, Liu Y. Obesity and hypertension (Review) Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(4):2395-9.

33. Jayedi A, Rashidy-Pour A, Khorshidi M, Shab-Bidar S. Body mass index, abdominal adiposity, weight gain and risk of developing hypertension: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of more than 2.3 million participants. Obes Rev. 2018;19(5):654-67.

34. Zhao Y, Qin P, Sun H, Liu Y, Liu D, Zhou Q, et al. Metabolically healthy general and abdominal obesity are associated with increased risk of hypertension. Br J Nutr. 2020;123(5):583-91.

35. Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(3):177-87.-3636. Semlitsch T, Jeitler K, Berghold A, Horvath K, Posch N, Poggenburg S, et al. Long-term effects of weight-reducing diets in people with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;Mar 2;3:CD008274.

1.5.3. Healthy Diet (LR: I; LE: A)

Several diets have been proposed for HT prevention which also favor hypertension control and contribute to health as a whole. 55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,3737. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti RE, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953-2041. One major proposal to that end is the DASH diet and its variants (low fat, Mediterranean, vegetarian/vegan, Nordic, low carbohydrate content, etc.). The benefits are even greater when combined with lower sodium intake. 55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,3737. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti RE, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953-2041.

38. Schwingshackl L, Chaimani A, Schwedhelm C, Toledo E, Pünsch M, Hoffmann G, et al. Comparative effects of different dietary approaches on blood pressure in hypertensive and pre-hypertensive patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59 (16): 2674-87.

39. Pergola G, D’Alessandro A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Blood Pressure. Nutrients. 2018;10 (1700):1-6.-4040. Ozemek C, Laddu DR, Arena R, Lavie CJ. The role of diet for prevention and management of hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33(4):388-93.

Every report on the subject recommends eating healthy amounts of fruits, greens, vegetables, cereal, milk, and dairy products, as well as lowering salt and fat intake. 3737. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti RE, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953-2041.

38. Schwingshackl L, Chaimani A, Schwedhelm C, Toledo E, Pünsch M, Hoffmann G, et al. Comparative effects of different dietary approaches on blood pressure in hypertensive and pre-hypertensive patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59 (16): 2674-87.

39. Pergola G, D’Alessandro A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Blood Pressure. Nutrients. 2018;10 (1700):1-6.

40. Ozemek C, Laddu DR, Arena R, Lavie CJ. The role of diet for prevention and management of hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33(4):388-93.-4141. Grillo A, Salvi L, Coruzzi P, Salvi P, Parati G. Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):1970. A meta-analysis compared varieties of these diets with the standard diet and found a greater decrease in SBP (-9.73 to -2.32 mm Hg) and DBP (-4.85 to -1.27 mm Hg) in the proper diet group. 3939. Pergola G, D’Alessandro A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Blood Pressure. Nutrients. 2018;10 (1700):1-6. Socioeconomic and cultural aspects have to be taken into account to ensure adherence to a given kind of dietary recommendation. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.,55. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.,66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,3737. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti RE, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953-2041.

1.5.4. Sodium (LR: I; LE: A)

Excess sodium intake is one of the main modifiable risk factors for preventing and controlling HT and CVD. 2929. EAF, Silva EN, Jaime PC. Developing and applying a costing tool for hypertension and related cardiovascular disease: attributable costs to salt/sodium consumption. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22(4):642-8. Sodium restriction has been shown to lower BP in several studies. A meta-analysis found that a 1.75 g decrease in daily sodium intake (4.4 g of salt/day) is associated with a mean decrease of 4.2 and 2.1 mm Hg in SBP and DBP, respectively. The BP decrease from sodium restriction is greater in blacks, older adults, diabetic patients, and individuals suffering from metabolic syndrome (MS) and CKD. 3737. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti RE, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953-2041.

In the general population, individuals are recommended to restrict their sodium intake to approximately 2 g/day (equivalent to about 5 g of salt per day). 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269. Effectively lowering salt intake is not easy, and low-salt foods are often underappreciated. Patients should be advised to take care with how much salt they add to their food and not to eat high-salt items (industrialized and processed foods). 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.

Decreasing Brazilian salt intake remains a high public health priority, but requires combined efforts from the food industry, all levels of government, and the public in general, since 80% of salt comes from processed foods. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,1010. Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, McQueen M, Dagenais G, Wielgosz A, et al. Urinary sodium excretion, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: a community-level prospective epidemiological cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392(10146):496–506.,1212. Mill JG, Malta DC, Machado ÍE, Pate A, Pereira CA, Jaime PC, et al. Estimativa do consumo de sal pela população Brazileira: resultado da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019;22(suppl 2):E190009. [Citado em 2020 Mar 10]. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v22s2/1980-5497-rbepid-22-s2-e190009-supl-2.pdf .

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v22s2/19...

,4040. Ozemek C, Laddu DR, Arena R, Lavie CJ. The role of diet for prevention and management of hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33(4):388-93. Adequate intake of fruits and vegetables leverages the beneficial effects of a low-sodium diet on BP. Salt substitutes with potassium chloride and less sodium chloride (30 to 50%) are useful to help lower sodium intake and increase potassium intake, despite their restrictions. 4242. Jafarnejad S, Mirzaei H, Clark CCT, Taghizadeh M, Ebrahimzadeh. The hypotensive effect of salt substitutes in stage 2 hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(98):1-15.

1.5.5. Potassium (LR: I; LE: A)

The relationship between potassium supplementation and lowering HT is relatively well understood. 4343. Whelton PK, He J, Cutler JA, Brancati FL, Appel LJ, Follmann, et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood pressure. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277(20):1624–32. Potassium supplementation represents a safe alternative, with no major adverse effects and modest but significant impact on BP, and can be recommended to help prevent the onset of HT. 4343. Whelton PK, He J, Cutler JA, Brancati FL, Appel LJ, Follmann, et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood pressure. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277(20):1624–32.

44. Stone MS, Martyn L, Weaver CM. Potassium Intake, Bioavailability, Hypertension, and Glucose Control. Nutrients. 2016;8(444):1-13.

45. Filippini T, Violi F, D’Amico R, Vinceti M. The effect of potassium supplementation on blood pressure in hypertensive subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017. 230:127-35.

46. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, Sheikh V, Hooshmand E, Maleki A. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essencial hypertension: A meta–analysis of randomized controlled trials. Plos One. 2017;12(4):1- 6.-4747. Caligiuri SPB, Pierce GN. A review of the relative efficacy of dietary, nutritional supplements, lifestyle, and drug therapies in the management of hypertension. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(16):3508-27. Adequate potassium intake, on the order of 90 to 120 mEq/day, may lead to a 5.3 mm Hg decrease in SBP and a 3.1 mm Hg decrease in DBP. 4545. Filippini T, Violi F, D’Amico R, Vinceti M. The effect of potassium supplementation on blood pressure in hypertensive subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017. 230:127-35. Its intake can increase by opting for sodium-poor and potassium-rich foods, such as beans, peas, dark leafy greens, bananas, melons, carrots, beets, dried fruit, tomatoes, potatoes, and oranges. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

1.5.6. Physical Activity (LR: I; LE: A)

A sedentary lifestyle is one of the ten most important risk factors for global mortality, causing approximately 3.2 million deaths per year. 4848. World Health Organization. (WHO). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases.Geneva; 2014. ISBN 978 92 4 156485 4.,4949. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990– 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859): 2224−60.

A meta-analysis of 93 papers and 5223 individuals showed that aerobic, dynamic resistance and isometric resistance training lower SBP and DBP at rest by 3.5/2.5, 1.8/3.2 and 10.9/6.2 mm Hg, respectively, in the general population. 5050. Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1):e004473.

51. Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, Hess NC, Millar PJ, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(3):327-34.-5252. Inder JD, Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, McFarlane JR, Hess NC, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis to optimize benefit. Hypertens Res. 2016;39(2):88-94.

All adults should be advised to practice at least 150 min/week of moderate physical activity or 75 min/week of vigorous activity. Aerobic exercises (walking, running, bicycling, or swimming) may be practiced for 30 minutes 5 to 7 times per week. Resistance training two to three days per week is also recommended. 5050. Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1):e004473.,5252. Inder JD, Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, McFarlane JR, Hess NC, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for blood pressure management: a systematic review and meta-analysis to optimize benefit. Hypertens Res. 2016;39(2):88-94. For additional benefits, in healthy adults, a gradual increase in physical activity to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity or 150 minutes per week of vigorous physical activity, or an equivalent combination of the two, ideally with supervised daily physical exercise. 5555. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315-81.

1.5.7. Alcohol (LR: IIA; LE: B)

Alcohol consumption is estimated to account for approximately 10 to 30% of HT cases and approximately 6% of all-cause mortality worldwide. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,1515. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Tobe SW, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Rehm J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(2):e108–e120.,5656. MacMahon S. Alcohol consumption and hypertension. Hypertension. 1987;9(2):111-21.

57. Lang T, Cambien F, Richard JL, Bingham A. Mortality in cerebrovascular diseases and alcoholism in France. Presse Med. 1987;16(28):1351-4.

58. Fuchs FD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Eigenbrodt ML, Duncan BB, Gilbert A, et al. Association between alcoholic beverage consumption and incidence of coronary heart disease in whites and blacks: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(5):466-74.-5959. World Health Organization.(WHO). Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva; 2014. Among drinkers, intake should not exceed 30 g of alcohol/day, ie, 1 bottle of beer (5% alcohol, 600 mL), two glasses of wine (12% alcohol, 250 mL), or one 1 dose (42% alcohol, 60 mL) of distilled beverages (whiskey, vodka, spirits). That threshold should be cut in half for low-weight men, women, the overweight, and/or those with high triglycerides. Teetotalers should not be encouraged to drink. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,1515. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Tobe SW, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Rehm J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(2):e108–e120.

1.5.8. Psychosocial Factors (LR: IIb; LE: B)

There is a wide variety of techniques used to control emotional stress and contribute to HT prevention, but there is still a dearth of robust studies on the subject. 33. Précoma DB, Oliveira GMM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MCO, et al. Atualização da Diretriz de Prevenção Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brazileira de Cardiologia – 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019; 113(4):787-891.

4. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al 2019, ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC. 2019; 74(10):e177-232.

5. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey Jr. DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol.; 201; 23976.-66. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension. JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199-269.,6060. Johnson HM. Anxiety and Hypertension: Is There a Link? A Literature Review of the Comorbidity Relationship Between Anxiety and Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21(9):66. Practicing emotional stress control can help CV reactivity, BP itself, and BP variability. 6161. Dalmazo AL, Fetter C, Goldmeier S, Irigoyen MC, Pelanda LC, Barbosa ECD, et al. Stress and Food Consumption Relationship in Hypertensive Patients. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113(3):374-80.

62. Denollet J, Gidron Y, Vrints CJ, Conraads VM. Anger, suppressed anger, and risk of adverse events in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(11):1555-60.-6363. Bai Z, Chang J, Chen C, Li P, Yang K, Chi I. Investigating the effect of transcendental meditation on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29(11):653-62.

1.5.9. Dietary Supplements (LR: I to III; LE: A and B)

The effects of dietary supplements on lowering BP are usually small and heterogeneous. 5858. Fuchs FD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Eigenbrodt ML, Duncan BB, Gilbert A, et al. Association between alcoholic beverage consumption and incidence of coronary heart disease in whites and blacks: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(5):466-74.

59. World Health Organization.(WHO). Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva; 2014.

60. Johnson HM. Anxiety and Hypertension: Is There a Link? A Literature Review of the Comorbidity Relationship Between Anxiety and Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21(9):66.

61. Dalmazo AL, Fetter C, Goldmeier S, Irigoyen MC, Pelanda LC, Barbosa ECD, et al. Stress and Food Consumption Relationship in Hypertensive Patients. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113(3):374-80.

62. Denollet J, Gidron Y, Vrints CJ, Conraads VM. Anger, suppressed anger, and risk of adverse events in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(11):1555-60.

63. Bai Z, Chang J, Chen C, Li P, Yang K, Chi I. Investigating the effect of transcendental meditation on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29(11):653-62.

64. Tankeu AT, Agbor VN, Noubiap JJ. Calcium supplementation and cardiovascular risk: A rising concern. J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19(6):640-6.

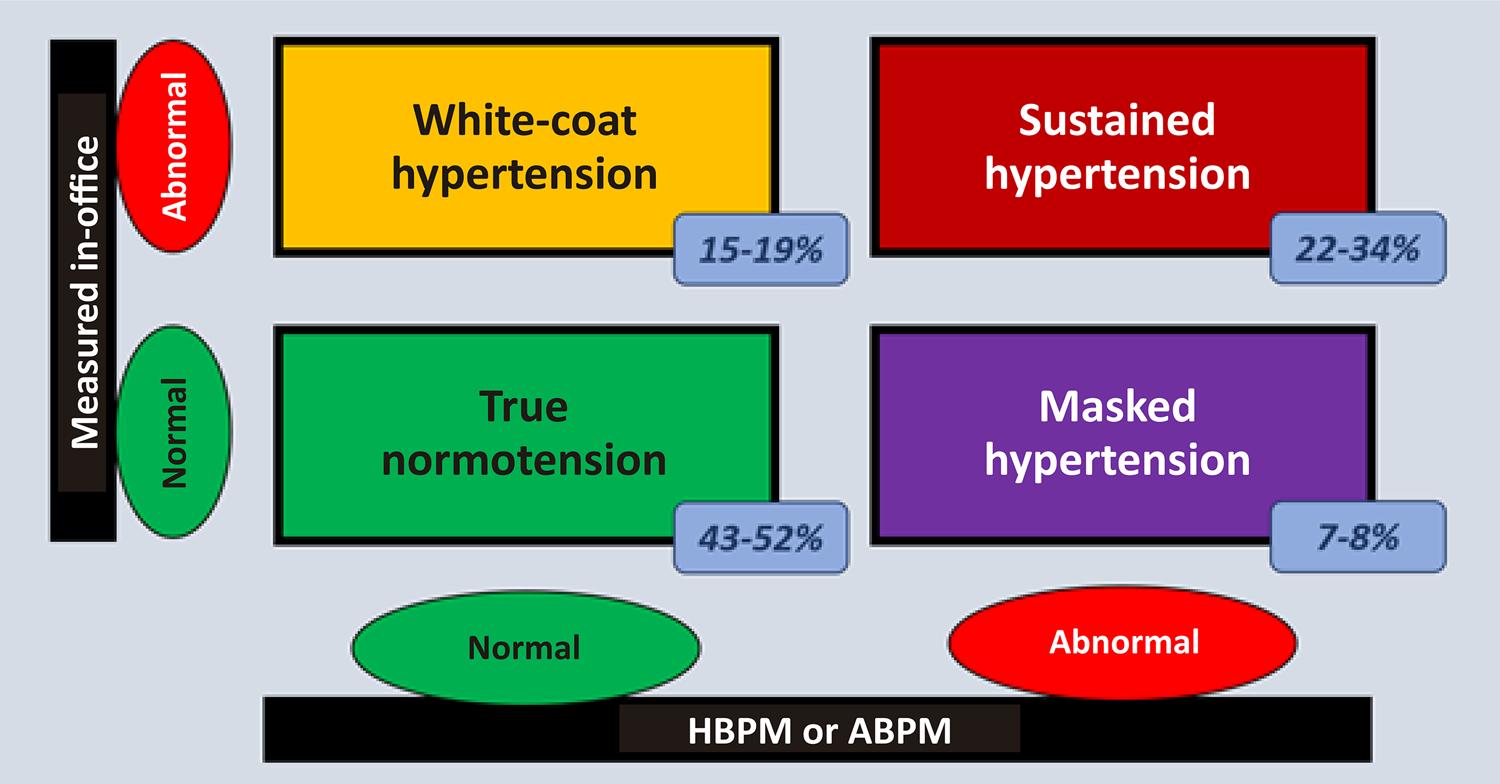

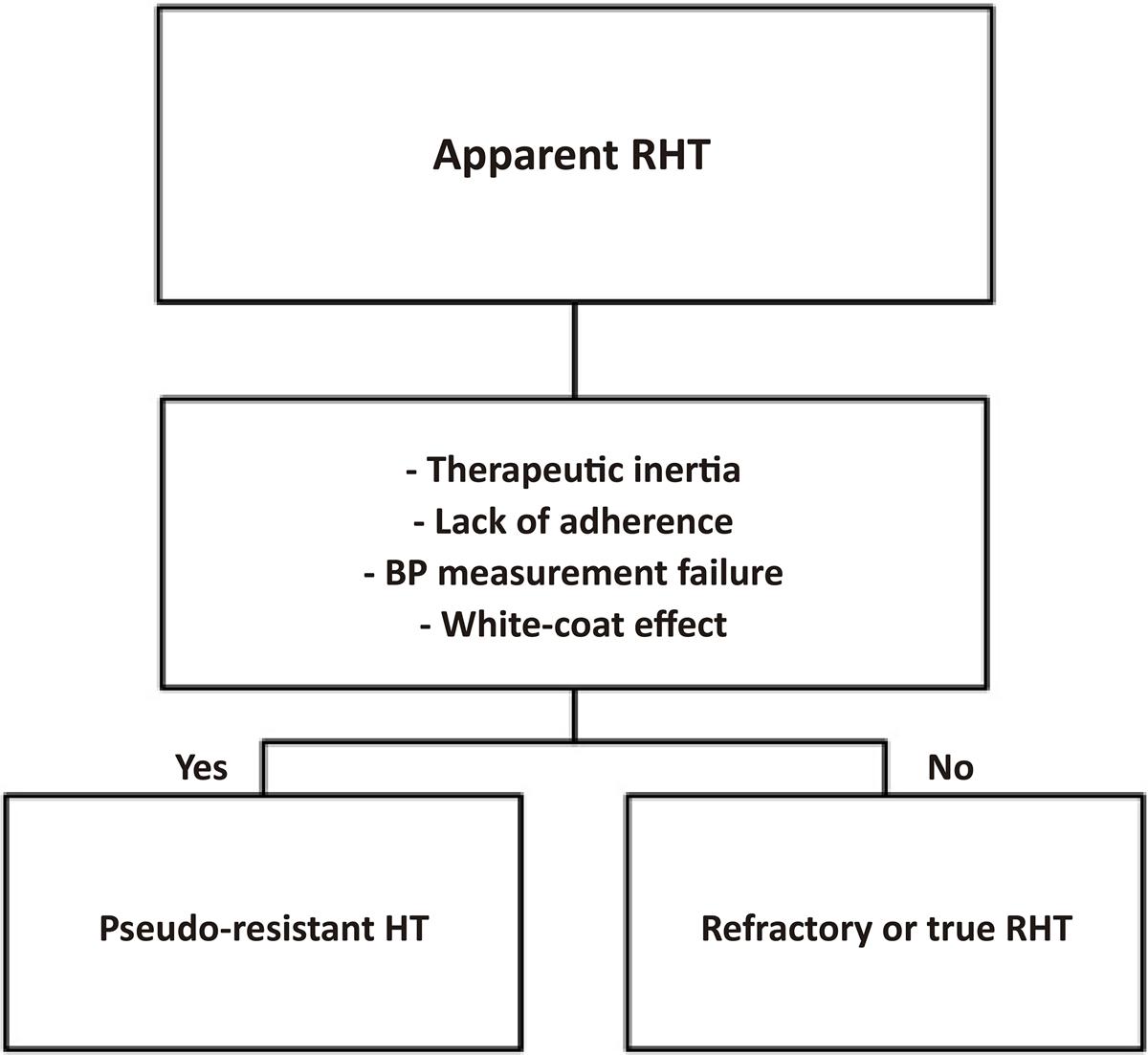

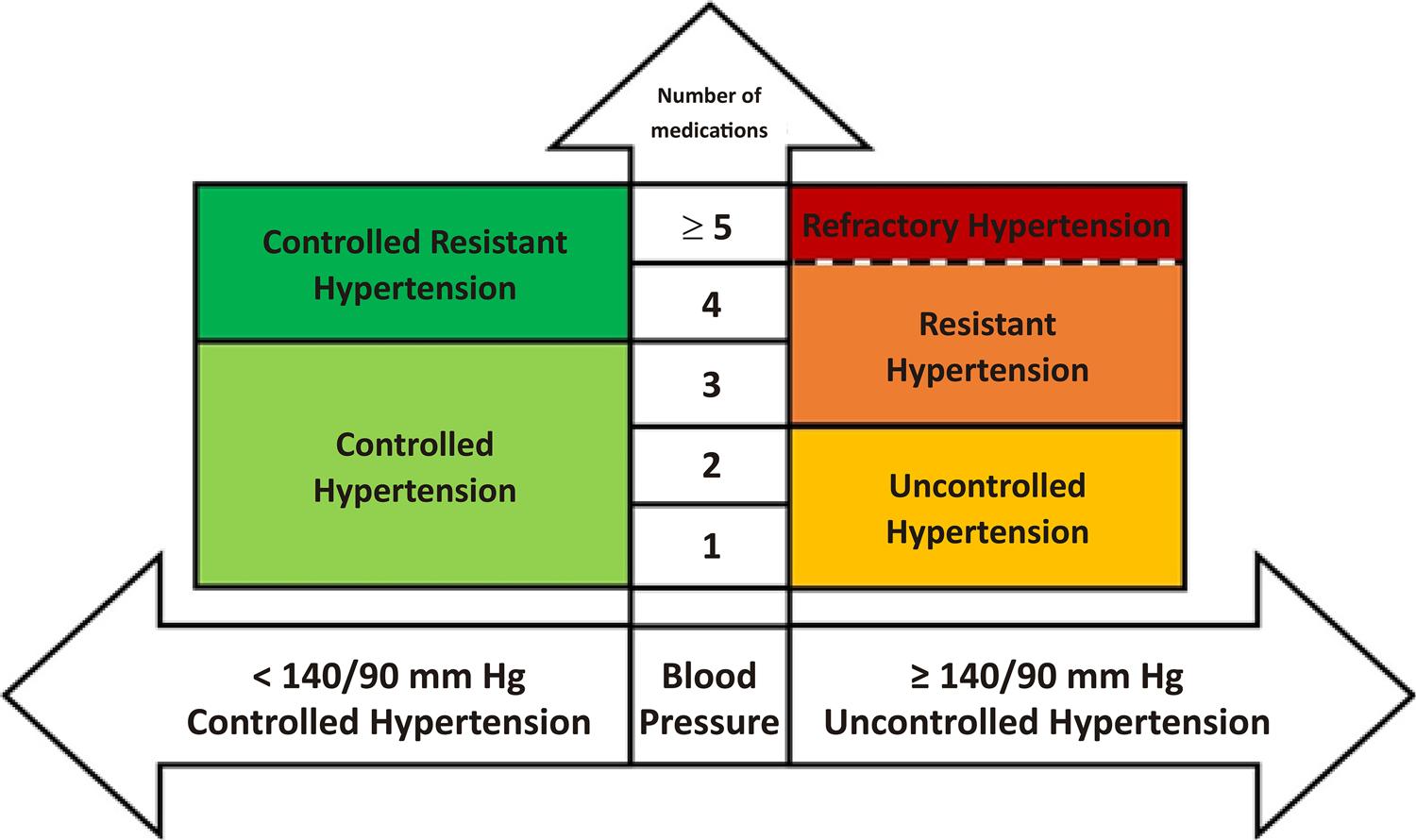

65. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, Christen W, Bassuk SS, Mora S, et al. Vitamin D Supplements and Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;380(1):33-44.