Brazilian Society of Cardiology Guidelines on Unstable Angina and Acute Myocardial Infarction without ST-Segment Elevation – 2021

Brazilian Society of Cardiology Guidelines on Unstable Angina and Acute Myocardial Infarction without ST-Segment Elevation – 2021

Definitions of Recommendations and Evidence

Recommendations

-

Class I: Conclusive evidence, or, failing that, general consensus that the procedure is safe and useful/effective.

-

Class II: Conflicting evidence and/or divergence of opinion about the procedure's safety and usefulness/effectiveness.

-

Class IIa: Evidence/opinion is in favor of the procedure. Most approve of it.

-

Class IIb: The procedure's safety and utility/effectiveness is less well established, opinion is not predominantly in favor of it.

-

Class III: Evidence and/or consensus that the procedure is not useful/effective and, in some cases, is harmful.

Evidence

-

Level A: Data obtained from multiple large randomized studies, concordant and/or robust meta-analysis of randomized clinical studies.

-

Level B: Data obtained from less robust meta-analysis, from a single randomized study or from non-randomized (observational) studies.

-

Level C: Data obtained from expert consensus.

Changes in recommendations

New recommendations

Part 1 – Emergency Assessment and Management

1. Introduction

Acute chest pain is responsible for more than 5% of all emergency department visits and up to 10% of non-trauma related visits. The incidence of chest pain varies between 9 and 19 per 1,000 people/year seen in emergency departments and is involved in up to 40% of hospitalizations. Although most of these patients are discharged with a diagnosis of unspecified or non-cardiac chest pain, about 25% are diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).11. Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, Angelini K, Capewell S, Nicholl J. The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart. 2005;91(2):229-30.,22. Barstow C, Rice M, McDivitt JD. Acute Coronary Syndrome: Diagnostic Evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(3):170-7.

The subgroup of patients whose electrocardiography (ECG) results show no ST-segment elevation but whose symptoms or complementary exam results are compatible with a coronary etiology are classified as having non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS), the subject of the present guideline. NSTE-ACS can cause significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly and appropriately treated. Since delaying appropriate treatment can result in serious adverse events, it is important to verify the presence of NSTE-ACS by assessing clinical data and complementary exams.33. Gibler WB, Racadio JM, Hirsch AL, Roat TW. Continuum of Care for Acute Coronary Syndrome: Optimizing Treatment for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Non-St-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2018;17(3):114-38.

2. Definitions

Chest pain is the main symptom in patients with ACS. ECG must be performed and interpreted within the first 10 minutes of medical contact in patients suspected of ACS, and the results may differentiate patients into two groups:

-

ST-elevation ACS: Patients with acute chest pain and persistent ST-segment elevation or new or presumably new left bundle branch block, which is a condition generally related to coronary occlusion and the need for immediate reperfusion.

-

NSTE-ACS: Patients with acute chest pain without persistent ST-segment elevation, whether associated or not with other ECG changes suggestive of some type of myocardial ischemia, including a broad spectrum of severity: transient ST-segment elevation, transient or persistent ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion, other nonspecific T-wave changes (flat or pseudonormalization), and even normal ECG results. This group includes patients with unstable angina (UA), ie, with no changes in myocardial necrosis markers and those with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) when there is an increase in myocardial necrosis markers.

A NSTEMI diagnosis is confirmed when there is an acute myocardial injury, which is confirmed by an increase in troponin levels, and the injury is suspected to be caused by ischemia. Based on its pathophysiology and clinical context, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is classified into several subtypes (Tables 1.1 and 1.2). Increased troponin levels can be secondary to myocardial ischemia, but they can also occur in other clinical situations (Table 1.3).

Myocardial injury and infarction11. Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, Angelini K, Capewell S, Nicholl J. The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart. 2005;91(2):229-30.

Situations in which there is an increase in myocardial necrosis markers but ischemia is not detected in the clinical picture, ECG or imaging tests should be defined as acute myocardial injury, not AMI. They can be secondary to cardiac causes (such as cardiovascular procedures, myocarditis, arrhythmias, or decompensated HF) or extracardiac causes (such as shock, severe anemia, sepsis and hypoxia).44. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J. 2019;40(3):237-69.

Myocardial injury is often related to a worse prognosis. It is necessary to differentiate between ischemic and nonischemic causes to avoid unnecessary invasive interventions and direct treatment toward other possible etiologies (Table 1.3).

Figure 1.1 summarizes the interpretation of elevated troponin in coronary injury and ischemia scenarios.

Algorithm for interpreting elevated troponin levels. The troponin “curve” indicates elevation greater than 20%

2.1. Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA)

Cases of AMI without obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) are classified as myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). Approximately two-thirds of patients with MINOCA have a clinical presentation of NSTEMI.55. Pasupathy S, Air T, Dreyer RP, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Systematic review of patients presenting with suspected myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circulation. 2015;131(10):861-70. Erratum in: Circulation. 2015;131(19):e475.

According to a document prepared by a European Society of Cardiology working group66. Scalone G, Niccoli G, Crea F. Editor's Choice-Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of MINOCA: an update. Eur Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8(1):54-62. and the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction,44. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J. 2019;40(3):237-69. the diagnostic criteria for MINOCA are: AMI, angiographic documentation without obstructive CAD (atheromatosis with <50% stenosis or normal coronary arteries) or a clinically evident non-coronary cause for acute presentation.

Different pathophysiological mechanisms can cause MINOCA:

-

Dysfunction of epicardial coronary arteries (eg, atherosclerotic plaque rupture, ulceration, cracking, erosion or coronary dissection).

-

Imbalance between oxygen supply and consumption (eg, coronary spasm and coronary embolism).

-

Coronary endothelial dysfunction (eg, microvascular disease).

MINOCA prognosis varies greatly, depending on the underlying mechanisms and associated risk factors, such as age and female gender. Some studies indicate that MINOCA has lower hospital mortality than AMI with obstructive coronary artery disease and similar 1-year mortality to AMI with univascular obstruction. However, when analyzing patients with NSTEMI in the ACUITY study, the MINOCA subgroup had the highest 1-year mortality (4.7% vs. 3.6%), which was linked to an increase in non-cardiac deaths.77. Niccoli G, Camici PG. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries: what is the prognosis?. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2020;22(Suppl E):E40-5.

8. Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, Agewall S, Brilakis ES, Brown TM, et al. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Myocardial Infarction in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(18):e891-e908.-99. Planer D, Mehran R, Ohman EM, White HD, Newman JD, Xu K, et al. Prognosis of patients with non-ST- segment-elevation myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary artery disease: propensity-matched analysis from the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(3):285-93.

The large group of patients presenting with elevated troponin but no coronary obstruction or clinical signs of infarction is classified as TINOCA (troponin-positive nonobstructive coronary arteries), which includes those with ischemic injury (MINOCA) and the other described etiologies of nonischemic myocardial injury (eg, myocarditis or Takotsubo syndrome; see Figure 1.2).

Myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) and troponin-positive nonobstructive coronary arteries (TINOCA): conceptual paradigm. Adapted from Pasupathy et al., 2017.1010. Pasupathy S, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): The Past, Present, and Future Management. Circulation. 2017 Apr 18;135(16):1490-3.

2.2. Unstable Angina

UA is defined as myocardial ischemia without myocardial necrosis, ie, with negative biomarkers. During the initial management of ACS, it is often difficult to differentiate UA from NSTEMI on clinical criteria alone (i.e., before levels of myocardial necrosis biomarkers are available), and both conditions should be treated similarly at this stage. Increased troponin sensitivity decreases the percentage of patients diagnosed with UA and increases the percentage of patients with NSTEMI. The prognosis of patients with UA ranges from relatively low risk to high risk. UA classifications based on clinical presentation and prognostic information facilitate therapeutic management, which will be discussed throughout this document.1111. Effects of tissue plasminogen activator and a comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Results of the TIMI IIIB Trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia. Circulation. 1994 Apr;89(4):1545-56.

12. Theroux P, Fuster V. Acute coronary syndromes: unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998 Mar 31;97(12):1195-206.

13. Zaacks SM, Liebson PR, Calvin JE, Parrillo JE, Klein LW. Unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction: does the clinical diagnosis have therapeutic implications? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 Jan;33(1):107-18.

14. Calvin JE, Klein LW, VandenBerg BJ, Meyer P, Ramirez-Morgen LM, Parrillo JE. Clinical predictors easily obtained at presentation predict resource utilization in unstable angina. Am Heart J. 1998 Sep;136(3):373-81.

15. Kong DF, Blazing MA, O’Connor CM. The health care burden of unstable angina. Cardiol Clin. 1999 May;17(2):247-61.-1616. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267-315.

3. Epidemiology

AMI is the leading cause of death in Brazil and worldwide.1717. Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M, et al; GBD 2013Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117-71. In 2017, according to DATASUS, 7.06% (92,657 patients) of all deaths were caused by AMI. AMI, which accounted for 10.2% of hospitalizations in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), was more prevalent in patients over 50 years of age, accounting for 25% of all hospitalizations).1818. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Informação em saúde: Estatísticas vitais. [Citado em 2020 fev 26]. Disponível em: http://datasus.saude.gov.br/).

http://datasus.saude.gov.br/...

In the Brazilian Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (BRACE), which evaluated ACS hospitalizations in 72 hospitals, NSTE-ACS was responsible for 45.7%, of which about 2/3 involved AMI and 1/3 UA. The study found generally low use of therapies that impact the prognosis of patients with ACS, including important regional differences. It also developed a performance score, which showed that the greater the adherence to proven treatments, the lower the mortality.1919. Franken M, Giugliano RP, Goodman SG, Baracioloi L, Godoy LC, Furtado RHM, et al. Performance of acute coronary syndrome approaches in Brazil. A report from the BRACE (Brazilian Registry in Acute Coronary syndromEs) [published online ahead of print, 2019 Aug 10]. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2019;qcz045.

4. Pathophysiology

The main pathophysiological characteristic of ACS is the instability of atherosclerotic plaque, involving erosion or rupture and subsequent formation of an occlusive or subocclusive thrombus. Such flow limitations, however, can be due to other mechanisms, such as vasospasm, embolism, or coronary dissection. Other factors may be involved in the pathophysiology of ACS by altering the supply and/or consumption of myocardial oxygen, such as anemia, hypertension, tachycardia, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis, etc..2020. Libby P. Mechanisms of Acute Coronary Syndromes and Their Implications for Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):2004-13.

In animals, ischemia has been observed to progress from the subendocardium to the subepicardium. This progression can be delayed when there is efficient collateral irrigation, reduced oxygen consumption in the myocardium, and intermittent flow (generating ischemic preconditioning). Changes in ventricular function due to the progression of myocardial ischemia initially involve diastolic dysfunction, which may be followed or not by systolic dysfunction. A shorter duration of ischemic injury is associated with a smaller area of myocardial necrosis. Several studies have also suggested that restoring perfusion results in some degree of myocardial injury (reperfusion injury), especially in situations of total coronary occlusion.2121. Ibáñez B, Heusch G, Ovize M, Van de Werf F. Evolving therapies for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Coll Cardiol.2015; 65(14):1454-71.

5. Initial Assessment

5.1. Initial Approach

Patients with suspected ACS and signs of severity (persistent pain, dyspnea, and palpitations due to potentially severe arrhythmias and syncope) should be referred to emergency departments, ideally monitored while in the ambulance. Patients without signs of severity (listed above) should be instructed to seek out an emergency department that can perform ECG and cardiac biomarker measurement, preferably troponin.

Several tools (scores) have been devised for this purpose and, in conjunction with clinical judgment, can help define which patients could benefit from hospitalization, complementary exams, and specific treatment.

5.2. Diagnosis and Prognostic Assessment

5.2.1. History and Clinical Data

5.2.1.1. Characterization of Chest Pain and Angina

The clinical picture of angina can be defined by four main pain characteristics: location, type, duration, and intensification or relief factors.

-

Location: usually in the chest, close to the sternum. However, it can affect or radiate from the epigastrium to the mandible, the interscapular region and the arms (more commonly to the left, less commonly to both arms or the right arm).

-

Type: the discomfort is usually described as pressure, tightness or weight. Sometimes it involves a feeling of strangulation, compression or burning. It may be accompanied by dyspnea, sweating, nausea, or syncope.

-

Duration: the duration of stable anginal pain is generally short (<10 min); episodes of ≥10 min suggest ACS. However, prolonged continuous pain (hours or days) or ephemeral pain (few seconds) is less likely to indicate ACS.

-

Intensification or relief factors: one important feature of angina is its relationship with physical exertion. Symptoms classically appear or intensify on exertion. In patients with no history of angina, a reduction in the effort threshold required to trigger angina suggests ACS. ACS discomfort does not usually vary with changes in breathing or position.

The clinical history of patients with NSTE-ACS plays an important role in risk stratification. In the presence of angina, patients with NSTE-ACS can present in four ways:

-

Prolonged resting angina (> 20 min).

-

Recent onset angina (class II or III according to Canadian Cardiovascular Society classification): in general, these patients manifest typical symptoms of angina in less than 2 months that begin appearing after minimal exertion.

-

Recent worsening of previously stable angina (crescendo angina). Minimal exertion triggers angina, increased pain intensity and/or duration, changes in pain radiation patterns, changes in response to the use of nitrates.

-

Post-infarction angina.

Some characteristics, antecedents and comorbidities are related to a higher probability of ACS:

-

Advanced age and male sex.

-

Risk factors for atherosclerosis: smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension and chronic renal failure.

-

Family history of CAD.

-

Previous symptomatic atherosclerosis, such as peripheral arterial obstructive disease, carotid disease, previous coronary disease.

-

Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis.

ACS patients may present with atypical symptoms, such as isolated epigastric pain, feelings of gastric fullness, lancinating pain, pleuritic pain or dyspnea. Although ACS typically presents in women and older adults (> 75 years) as angina, atypical presentations are also higher in these groups, as well as in patients with DM, renal failure and dementia.

The Coronary Artery Surgery Study proposed a chest pain classification system,2222. The Principal Investigators of CASS and Their Associates. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Coronary Artery Surgery Study: historical background, design, methods, the registry, the randomized trial, clinical database. Circulation. 1981;63(suppl I):I-1-I-81. which is shown in Table 1.4.

5.2.1.2. NSTE-ACS in Older Adults

Older adults with ACS generally have a different risk profile from younger adults: they have a higher prevalence of hypertension, DM, previous AMI, angina, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, multivessel disease, and HF. Older adults generally wait longer to seek medical care after symptom onset. In NSTE-ACS, instead of pain, patients often have so-called “ischemic-equivalent” symptoms, such as dyspnea, malaise, mental confusion, syncope or pulmonary edema. Older adults have a higher incidence of complications in NSTE-ACS, which implies the need for more intensive treatment. However, especially in adults over 75 years of age, the most appropriate therapy, ie, beta-blockers, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), anticoagulants and lipid-lowering agents, is not used. Of the 3,318 patients with NSTE-ACS included in the TIMI III study,2323. Stone PH, Thompson B, Anderson HV, Kronenberg MW, Gibson RS, Rogers WJ, et al. Influence of race, sex, and age on management of unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: The TIMI III registry. JAMA. 1996 Apr 10;275(14):1104-12. 828 were over 75 years old. These individuals received anti-ischemic therapy and underwent cardiac catheterization at a lower percentage than younger patients. Although they had more severe and extensive CAD, they less frequently underwent myocardial revascularization procedures and had more adverse events within 6 weeks of onset. According to a national database study, the use of proven efficacious therapies after ACS has increased in the last 15 years, both among the oldest old (age > 80 years) and in younger adults (< 50 years), and this increase has been associated with improved survival in both groups.2424. Nicolau JC, Franci A, Barbosa CJ, Baracioli LM, Franken M, Furtado RH, et al. Influence of proven oral therapies in the very old with acute coronary syndromes: A 15 year experience. Int J Cardiol. 2015 Nov 1;198:213-5.

5.2.1.3. History

5.2.1.3.1. Patients Undergoing Myocardial Revascularization Procedures: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and/or Myocardial Revascularization Surgery

The recurrence of angina after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can indicate acute complications, new injuries, stent thrombosis, or restenosis. Chest pain up to 48 hours after percutaneous intervention suggests acute obstruction, transient coronary spasm, non-occlusive thrombus, branch occlusion or distal embolization. Recurrent chest pain approximately 6 months after conventional stenting or later, after drug-eluting stenting, is most likely related to restenosis. On the other hand, angina onset 1 year after stenting is usually related to a new coronary lesion or stent restenosis due to neoaterosclerosis. After a CABG, the early appearance of pain is usually associated with thrombotic obstruction of the graft. In the first 12 months after CABG, the mechanism is usually fibrous intima hyperplasia; after this period, pain is indicative of a new atherosclerotic lesion and/or non-thrombic graft degeneration. The TIMI III registry compared the incidence of death or nonfatal infarction among NSTE-ACS patients with or without previous CABG. Those with previous CABG had higher rates of complications up to 10 days after admission (4.5% vs. 2.8% with or without CABG, respectively) and after 42 days (7.7% vs. 5.1%, respectively), which suggests that this is a higher risk group, mainly due to more extensive atherosclerosis.2525. Kleiman NS, Anderson HV, Rogers WJ, Theroux P, Thompson B, Stone PH. Comparison of outcome of patients with unstable angina and non-Q-wave acute myocardial infarction with and without prior coronary artery bypass grafting (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia III Registry). Am J Cardiol. 1996 Feb 1;77(4):227-31.

5.2.1.3.2. Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease

Some studies have suggested that smokers have a better prognosis, probably due to the fact that they suffer ACS at an earlier age and have less atherosclerotic burden than non-smokers.2626. Barbash GI, Reiner J, White HD, Wilcox RG, Armstrong PW, Sadowski Z, et al. Evaluation of paradoxic beneficial effects of smoking in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: mechanism of the “smoker's paradox” from the GUSTO-I trial, with angiographic insights. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue-Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Nov 1;26(5):1222-9.,2727. Barbash GI, White HD, Modan M, Diaz R, Hampton JR, Heikkila J, et al. Significance of smoking in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Experience gleaned from the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase Mortality Trial. Circulation. 1993 Jan;87(1):53-8. On the other hand, Antman et al. showed that having three or more risk factors for CAD (systemic arterial hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, family history and smoking) is an independent marker of a worse prognosis.2828. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000 Aug 16;284(7):835-42.

5.2.2. Physical examination

During assessment of individuals with NSTE-ACS, a physical examination can help identify individuals at higher risk (those with signs of severe ventricular dysfunction or mechanical complications) and help in the differential diagnosis of chest pain unrelated to ACS.

As a rule, a normal or slightly modified physical examination is insufficient to stratify patient risk, since even patients with multivessel or left main coronary lesions can appear normal upon physical examination.2929. Braunwald E, Jones RH, Mark DB, Brown J, Brown L, Cheitlin MD, et al. Diagnosing and managing unstable angina. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Circulation. 1994 Jul;90(1):613-22.

30. Yeghiazarians Y, Braunstein JB, Askari A, Stone PH. Unstable angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 13;342(2):101-14.-3131. Braunwald E, Califf RM, Cannon CP, Fox KA, Fuster V, Gibler WB, et al. Redefining medical treatment in the management of unstable angina. Am J Med. 2000 Jan;108(1):41-53. However, when changes are found in a physical examination, they can be important for categorizing patients as high risk.

Some findings that indicate a poor prognosis include systolic murmur in the mitral focus tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, sweating, weak pulse, third heart sound, and pulmonary rales.

Changes in physical examination results allow differential diagnosis between ACS and other causes of chest pain:

-

• Cardiac: pericarditis (pericardial friction), cardiac tamponade (paradoxical pulse), aortic stenosis (aortic systolic murmur), and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (ejection systolic murmur in the parasternal area that increases with the Valsalva maneuver).

-

• Non-cardiac: aortic dissection (pulse and pressure divergence between the arms and a diastolic murmur of aortic insufficiency), pulmonary embolism/pulmonary infarction (pleural friction), pneumothorax (decreased breath sounds and hyperresonance to percussion), and musculoskeletal symptoms (pain on palpation).

5.2.3. Electrocardiogram

Twelve-lead ECG is the initial diagnostic tool for patients with suspected ACS. Ideally, it should be performed and interpreted during pre-hospital care or within 10 minutes of hospital admission.

About 1% to 6% of patients with NSTE-ACS have normal (non-diagnostic) ECG results at admission. The ECG should be repeated after 15 to 30 minutes, especially in individuals who are still symptomatic. Normal or non-diagnostic ECG results can occur even with left circumflex or right coronary artery occlusion. Thus, additional V3R, V4R, V7, V8, and V9 derivations are recommended to increase the method's sensitivity.

More than 1/3 of patients will have typical ACS changes, such as ST-segment depression, transient ST-segment elevation, and T-wave inversion. Dynamic changes in the ST-segment (depression or elevation) or T-wave inversions during a painful episode that resolve at least partially when the symptoms are relieved are important markers of adverse prognosis, ie, subsequent AMI or death.3232. Bosch X, Theroux P, Pelletier GB, Sanz G, Roy D, Waters D. Clinical and angiographic features and prognostic significance of early postinfarction angina with and without electrocardiographic signs of transient ischemia. Am J Med. 1991 Nov;91(5):493-501. Patients with ST changes in anterior leads often have significant stenosis of the anterior descending coronary artery and are a high-risk group.

ST-segment and T-wave changes are not specific to NSTE-ACS and can occur in several conditions, including: ventricular hypertrophy, pericarditis, myocarditis, early repolarization, electrolyte alteration, shock, metabolic dysfunction, and digitalis effect.

The diagnostic accuracy of an abnormal ECG is increased when previous ECG results are available for comparison.

Transient ST-segment elevation is consistent with Prinzmetal or vasospastic angina. Concomitant ST elevation in the anterior and inferior leads (reflecting extensive ischemia) is associated with an increased risk of sudden death.3333. Gottlieb SO, Weisfeldt ML, Ouyang P, Mellits ED, Gerstenblith G. Silent ischemia predicts infarction and death during 2 year follow-up of unstable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987 Oct;10(4):756-60.

5.2.3.1. Electrocardiogram Findings and Prognosis

Patients with NSTE-ACS are at high risk of ischemic ECG changes (elevated or depressed ST-segment), atrial fibrillation, and ventricular arrhythmias. These changes imply a worse prognosis.3131. Braunwald E, Califf RM, Cannon CP, Fox KA, Fuster V, Gibler WB, et al. Redefining medical treatment in the management of unstable angina. Am J Med. 2000 Jan;108(1):41-53. In the GUSTO II trial, certain baseline ECG factors in patients with ACS were prognostic of early mortality:3434. Armstrong PW, Fu Y, Chang WC, Topol EJ, Granger CB, Betriu A, et al. Acute coronary syndromes in the GUSTO-IIb trial: prognostic insights and impact of recurrent ischemia. The GUSTO-IIb Investigators. Circulation. 1998 Nov 3;98(18):1860-8. left bundle branch block, left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy or pacemaker rhythm (11.6%); ST-segment depression (8%); ST-segment elevation (7.4%); and normal T-wave inversion or normal ECG (1.2%).

Moreover, in 1,416 patients with ACS, the TIMI III Registry ECG Ancillary Study3535. Cannon CP, McCabe CH, Stone PH, Rogers WJ, Schactman M, Thompson BW, et al. The electrocardiogram predicts one-year outcome of patients with unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI III Registry ECG Ancillary Study. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Jul;30(1):133-40. found the following ECG presentations: ST-segment deviation > 1 mm (14.3%), left bundle branch block (19%), isolated T-wave inversion (21.9%), or none of these changes (54.9%).

5.2.4. Biomarkers

In patients with ACS, biomarkers are useful for both diagnosis and prognosis. When myocardial cells are injured, their cell membranes lose integrity, intracellular proteins diffuse across the interstitium and into the lymphatic system and capillaries. After a myocardial injury, marker kinetics depend on several factors: intracellular protein degradation, molecule size, regional lymphatic and blood flow, as well as marker clearance rate. Such factors, together with the characteristics of each marker, differentiate each patient's diagnostic AMI performance.3636. Lee TH, Goldman L. Serum enzyme assays in the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Recommendations based on a quantitative analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1986 Aug;105(2):221-33.

In patients with symptoms suggestive of ACS but without diagnosed AMI, cardiac biomarkers are useful to confirm the diagnosis. They also provide important prognostic information, since there is a direct association between elevated serum markers and the risk of cardiac events in the short and medium- term.3737. Newby LK, Christenson RH, Ohman EM, Armstrong PW, Thompson TD, Lee KL, et al. Value of serial troponin T measures for early and late risk stratification in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The GUSTO-IIa Investigators. Circulation. 1998 Nov 3;98(18):1853-9. The necrosis marker results must be available within 60 minutes of collection. If the clinical analysis laboratory cannot provide this, point-of-care technologies should be considered.3838. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, Diercks DE, Farkouh ME, Garvey JE, et al. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(17):1756-776.

5.2.4.1. Troponins

Troponins are a complex of myofibrillar regulatory proteins in striated cardiac muscle that include troponin T, troponin I, and troponin C. Troponin C is coexpressed in slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers and is not considered as a specific cardiac marker. In recent decades, immunoassay techniques with specific monoclonal antibodies for cardiac troponin T and cardiac troponin I have been developed. Meta-analyses have shown that the sensitivity and specificity of cardiac troponin I for diagnosing AMI was approximately 90% and 97%, respectively. Cardiac troponins remain elevated for a longer time, up to 7 days after AMI. Troponins are the biomarkers of choice for diagnostic evaluation in patients with suspected AMI since their diagnostic accuracy is higher than that of creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) mass and other biomarkers of myocardial injury. Patients with elevated troponins are at increased risk of cardiac events during the first days of hospitalization and are the NSTE-ACS subgroup that can most benefit from an invasive strategy.3939. Ohman EM, Armstrong PW, Christenson RH, Granger CB, Katus HA, Hamm CW, et al. Cardiac troponin T levels for risk stratification in acute myocardial ischemia. GUSTO IIA Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996 Oct 31;335(18):1333-41. Although troponins can accurately identify myocardial injury, they cannot identify the mechanism of injury(ies). The mechanisms can include non-coronary etiologies, such as tachyarrhythmias and myocarditis, or non-cardiac conditions, such as sepsis, pulmonary embolism, and renal failure.4040. Jaffe AS, Ravkilde J, Roberts R, Naslund U, Apple FS, Galvani M, et al. It's time for a change to a troponin standard. Circulation. 2000 Sep 12;102(11):1216-20. Thus, in cases where the clinical presentation is not typical of ACS, other causes of cardiac injury related to increased troponins should be considered.

Troponins have recognized value when evaluating patients with ischemic ECG changes or with clinical symptoms suggestive of anginal pain. The major limitation of conventional troponins is their low sensitivity in patients whose time to onset is less than 6 hours. With the introduction of highly sensitive troponin assays, it became possible to detect lower troponin levels in a shorter time after ischemic myocardial injury.4141. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, Steuer S, Stelzig C, Hartwiger S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):858-67.,4242. Giannitsis E, Kurz K, Hallermayer K, Jarausch J, Jaffe AS, Katus HA. Analytical validation of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clin Chem. 2010;56(2):254-61. The unit used to express the values of conventional troponin is ng/mL, and in highly sensitive troponins, the values can be expressed in ng/L, since their detection power is 10 to 100 times greater than conventional troponins.

Highly sensitive troponins are significantly more sensitive than conventional troponins in ACS diagnosis, improving the diagnostic power for AMI by 61% if collected less than 3 hours after onset and 100% if collected 6 hours after onset.4343. Mueller C. Biomarkers and acute coronary syndromes: an update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(9):552–6. Due to the highly sensitive troponin assay's increased sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy for AMI, accelerated diagnosis algorithms have been proposed. Thus, the time to diagnosis can be shortened, which means less time in the emergency department and lower costs.4444. Westermann D, Neumann J, Sörensen N,Blankenberg S. High-sensitivity assays for troponin in patients with cardiac disease. Nat Rev Cardiol.2017;14(8):472-83.

45. Stoyanov KM, Hund H, Biener M,Gandowitz J, Riedle C, Lohr J, et al. RAPID-CPU: a prospective study on implementation of the ESC 0/1-hour algorithm and safety of discharge after rule-out of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9(1):39-51.-4646. Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Twerenbold R, Wildi K, Badertscher P, Cupa J, et al. Direct Comparison of 4 Very Early Rule-Out Strategies for Acute Myocardial Infarction Using High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):1597-11. It is recommended that the investigation algorithm be used within 3 hours (see routine diagnostic flowchart and hospitalization criteria).

5.2.4.2. Creatine Kinase: Isozymes and Isoforms

Before troponins emerged as more accurate biomarkers in AMI diagnosis, CK-MB was the most common biomarker in chest pain protocols. Ideally, CK-MB should be measured by immunoassay for plasma concentration (CK-MB mass) rather than activity. This change in measurement patterns is due, in part, to studies that demonstrated that CK-MB mass has greater sensitivity and specificity for AMI.4747. Mair J, Morandell D, Genser N, Lechleitner P, Dienstl F, Puschendorf B. Equivalent early sensitivities of myoglobin, creatine kinase MB mass, creatine kinase isoform ratios, and cardiac troponins I and T for acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 1995 Sep;41(9):1266-72. CK-MB subforms have emerged as early markers (< 6 hours) of myocardial injury and early inference of AMI severity, according to data from a necropsy study that demonstrated a better correlation between CK-MB mass and AMI size.4848. Costa TN, Strunz CM, Nicolau JC, Gutierrez PS. Comparison of MB fraction of creatine kinase mass and troponin I serum levels with necropsy findings in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008 Feb 1;101(3):311-4. However, the main limitation of CK-MB mass is damage to other non-cardiac tissues (false positives), especially after injuries to smooth or skeletal muscle. In about 4% of patients, false-positive results can occur, with positive CK-MB and negative troponin.4949. Lin JC, Apple FS, Murakami M,Luepker RV. Rates of positive cardiac troponin I and creatine kinase MB mass among Patients Hospitalized for Suspected Acute Coronary Syndromes. Clin Chem. 2004;50(2):333–8. In cases where CK-MB is elevated and troponin is normal, both within their kinetic windows, clinical decisions should be based on the troponin results.

5.2.5. Non-Invasive Imaging in the Emergency Department

5.2.5.1. Functional Assessment

Non-invasive exams play an essential role in the diagnosis (especially in patients with normal ECG and biomarker results) and risk stratification of patients with suspected ACS. The choice for each patient – whether ET, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, cardiac resonance, or coronary computed tomography angiography – will depend on the objectives and clinical questions to be answered.5050. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Diercks DB, Lewis WR, Turnipseed SD. Immediate exercise testing to evaluate low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(2):251-6. 165.

5.2.5.2. Exercise Testing in the Emergency Department

In the emergency department, patients whose chest pain is identified as low or intermediate risk can undergo ET. Normal results indicate a low risk of cardiovascular events, allowing for earlier and safer hospital discharge.5050. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Diercks DB, Lewis WR, Turnipseed SD. Immediate exercise testing to evaluate low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(2):251-6. 165. National and international guidelines recommend ET as the first choice for risk stratification in patients who can exercise since it is a low-cost procedure, is widely available, and has a low frequency of complications.5151. Meneghelo RS, Araújo CG, Stein R, Mastrocolla LE, Albuquerque PF, Serra SM, et al; Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. III Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia sobre teste ergométrico. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95(5 Suppl 1):1-26. However, patients with moderate- to high-risk ACS, acute aortic diseases, pulmonary thromboembolism, myocarditis, or pericarditis must be ruled out since these conditions are absolute contraindications. The testing protocol should be determined according to the patient's clinical condition, with the most recommended being a modified Naughton or Bruce ramp test.

ET indications in ACS (to characterize low risk after initial clinical stratification) include:

-

Baseline ECG and necrosis biomarkers without changes.

-

Absence of symptoms (chest pain or dyspnea).

-

Hemodynamic stability and adequate conditions for physical exertion.

If the ET results are normal and the patient has shown adequate functional capacity, other procedures may not be necessary due to the test's high negative predictive value.5151. Meneghelo RS, Araújo CG, Stein R, Mastrocolla LE, Albuquerque PF, Serra SM, et al; Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. III Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia sobre teste ergométrico. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95(5 Suppl 1):1-26.

5.2.5.3. Echocardiography

Echocardiography is a useful complementary method for evaluating chest pain in emergencies.5252. Peels CH, Visser CA, Kupper AJ, Visser FC, Roos JP. Usefulness of two-dimensional echocardiography for immediate detection of myocardial ischemia in the emergency room. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Mar 15;65(11):687-91.

53. Sabia P, Abbott RD, Afrookteh A, Keller MW, Touchstone DA, Kaul S. Importance of two-dimensional echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular systolic function in patients presenting to the emergency room with cardiac-related symptoms. Circulation. 1991 Oct;84(4):1615-24.-5454. Feigenbaum H. Role of echocardiography in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Nov 20;66(18):17H-22H. This non-invasive exam provides quick diagnostic information.5555. Parisi AF. The case for echocardiography in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1988 May;1(3):173-8.

56. Reeder GS, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. The role of two-dimensional echocardiography in coronary artery disease: a critical appraisal. Mayo Clin Proc. 1982 Apr;57(4):247-58.

57. Gibson RS, Bishop HL, Stamm RB, Crampton RS, Beller GA, Martin RP. Value of early two dimensional echocardiography in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1982 Apr 1;49(5):1110-9.

58. Visser CA, Lie KI, Kan G, Meltzer R, Durrer D. Detection and quantification of acute, isolated myocardial infarction by two dimensional echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1981 May;47(5):1020-5.-5959. Heger JJ, Weyman AE, Wann LS, Rogers EW, Dillon JC, Feigenbaum H. Cross-sectional echocardiographic analysis of the extent of left ventricular asynergy in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1980 Jun;61(6):1113-8. When performed during an episode of chest pain, a lack of abnormal ventricular segmental contraction indicates a nonischemic cause. Although echocardiography cannot determine whether the segmental change is recent or pre-existing, the presence of segmental contraction abnormalities reinforces the probability of CAD being indicative of infarction, ischemia, or both. However, it can also appear in cases of myocarditis.6060. Ryan T, Vasey CG, Presti CF, O’Donnell JA, Feigenbaum H, Armstrong WF. Exercise echocardiography: detection of coronary artery disease in patients with normal left ventricular wall motion at rest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 May;11(5):993-9.

61. Sawada SG, Ryan T, Conley MJ, Corya BC, Feigenbaum H, Armstrong WF. Prognostic value of a normal exercise echocardiogram. Am Heart J. 1990 Jul;120(1):49-55.-6262. Cheitlin MD, Alpert JS, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, Beller GA, Bierman FZ, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography. Circulation. 1997 Mar 18;95(6):1686-744.

Other no less important etiologies of chest pain (e.g., aortic dissection, aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and pericardial disease) can also be assessed with echocardiography. Significant coronary heart disease is commonly found in patients with UA. These patients are generally identified by clinical history, and reversible ECG changes can be detected with pain episodes. When the patient's history and ECG are atypical, documenting a segmental contraction abnormality with echocardiography during or immediately after a pain episode strongly suggests the diagnosis.6363. Ersbøll M, Valeur N, Mogensen UM, Andersen MJ, Møller JE, Velazquez EJ, Hassager C,et al. Prediction of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions from global left ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with acute myocardial infarction and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jun 11;61(23):2365-73. Echocardiography also determines the presence and extent of ventricular dysfunction and the presence and severity of valve abnormalities.

Other parameters are also important in determining prognosis in addition to the LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and segmental motility. Ersbǿll et al. prospectively studied patients with infarction and LVEF > 40% within 48 hours of admission. All patients underwent ECG with semi-automated global longitudinal strain (GLS) assessment. Of the 849 patients, 57 (6.7%) had severe cardiac events, and GLS > −14% was associated with a 3-fold increase in the risk of severe events.6363. Ersbøll M, Valeur N, Mogensen UM, Andersen MJ, Møller JE, Velazquez EJ, Hassager C,et al. Prediction of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions from global left ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with acute myocardial infarction and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jun 11;61(23):2365-73.

5.2.5.4. Stress Echocardiography

Stress echocardiography is being increasingly used in emergency departments and soon after hospitalization.6464. Lin SS, Lauer MS, Marwick TH. Risk stratification of patients with medically treated unstable angina using exercise echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1998 Sep 15;82(6):720-4. One study analyzed 108 patients who were observed for 4 hours with serial biomarkers and ECG and underwent stress ET or dobutamine stress ECG. Ten patients had positive stress ET results, and 8 had positive stress ECG results. The exams were consistent in 4 patients. All patients whose stress ECG results showed no evidence of ischemia were cardiac event-free at the end of 12 months of follow-up, as were 97% of the patients with negative stress ET results.6565. Colon PJ, III, Guarisco JS, Murgo J, Cheirif J. Utility of stress echocardiography in the triage of patients with atypical chest pain from the emergency department. Am J Cardiol. 1998 Nov 15;82(10):1282-4, A10.

A Brazilian study evaluated 95 patients with low- and moderate-risk UA with echocardiography under dobutamine stress, most of whom were assessed in the first 72 hours of hospitalization. For the clinical outcomes (death, AMI, new hospitalization due to UA and myocardial revascularization procedures), the exam proved to be safe and had an excellent negative predictive value (96%), allowing early discharge without the need for other tests.6666. Markman Filho B, Almeida MC, Markman M, Chaves A, Moretti M,Ramires JA, Cesar LA. Stratifying the risk in unstable angina with dobutamine stress echocardiography. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006; 87(3):294-9. Using perfusion techniques to perform stress echocardiography can increase diagnostic sensitivity; their applications are discussed in Part 2 of this Guideline.

Because it is an accessible, fast, low-cost, and non-invasive test, echocardiography can provide additional prognostic information about the previously mentioned parameters by assessing global and regional ventricular function and identifying associated valvulopathy. It can be routinely used in the investigation of these patients. Its disadvantages are its limited acoustic window in some patients and reduced sensitivity to dobutamine stress in patients on beta-blockers.

5.2.5.5. Nuclear Cardiology

Several studies have suggested that low-risk results for resting myocardial scintigraphy performed in the emergency department indicate a very low risk of subsequent cardiac events. On the other hand, there is a much greater probability that patients with high-risk myocardial perfusion scintigraphy results will develop AMI, be revascularized (surgery or angioplasty), or have coronary lesions a coronary angiogram.6767. Jain D, Thompson B, Wackers FJ, Zaret BL. Relevance of increased lung thallium uptake on stress imaging in patients with unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction: results of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)-IIIB Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Aug;30(2):421-9.

68. Geleijnse ML, Elhendy A, van Domburg RT, Cornel JH, Rambaldi R, Salustri A, et al. Cardiac imaging for risk stratification with dobutamine-atropine stress testing in patients with chest pain. Echocardiography, perfusion scintigraphy, or both? Circulation. 1997 Jul 1;96(1):137-47.-6969. Kontos MC, Jesse RL, Schmidt KL, Ornato JP, Tatum JL. Value of acute rest sestamibi perfusion imaging for evaluation of patients admitted to the emergency department with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Oct;30(4):976-82. The ERASE trial evaluated care strategies for ACS patients with normal or non-diagnostic ECG, finding admission rates of 54% for patients who underwent MPS and 63% for all others, which suggests that an initial strategy involving resting scintigraphy is an acceptable risk stratifier.7070. Kapetanopoulos A, Heller GV, Selker HP, Ruthazer R, Beshansky JR, Feldman JA, et al. Acute resting myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with diabetes mellitus: results from the Emergency Room Assessment of Sestamibi for Evaluation of Chest Pain (ERASE Chest Pain) trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004 Sep;11(5):570-7.

International guidelines recommend rest myocardial perfusion imaging during acute chest pain to stratify risk in patients with suspected ACS who have non-diagnostic ECG results.7171. Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, Heidenreich PA, Henkin RE, Pellikka PA, Pohost GM,et al. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging. Circulation. 2009 Jun 9;119(22):e561-87;

72. Klocke FJ, Baird MG, Lorell BH, Bateman TM, Messer JV, Berman DS, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society for Nuclear Cardiology. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Society for Nuclear Cardiology. ACC/AHA/ASNC guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASNC Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(7):1318-33.-7373. Notghi A, Low CS. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy: past, present and future. Br J Radiol.2011;84(Spec 3):S229-36.

Radiotracer injection:

The main applications of MPS in the first hours after the patient's hospital admission include:

-

Injection of the radiotracer (sestamibi/MIBI or technetium-99m-labeled tetrofosmin, or 99mTc-sestamibi, and 99mTc-tetrofosmin) at rest during a chest pain episode in patients with normal or nonspecific ECG, aiming at a rapid, definitive diagnosis.

-

Injection of the radiotracer at rest in patients without chest pain, normal or nonspecific ECG, and symptom cessation less than 6 hours, but preferably within the previous 2 hours. Wackers et al. found that when the injection was performed in the first 6 hours of pain in ACS patients, the incidence of perfusion abnormalities was 84%, which decreased to 19% when the radiotracer was intravenously administered between 12 and 18 hours after the last pain episode.7474. Wackers FJ, Brown KA, Heller GV, Kontos MC, Tatum JL, Udelson JE, et al. American Society of Nuclear Cardiology position statement on radionuclide imaging in patients with suspected acute ischemic syndromes in the emergency department or chest pain center. J Nucl Cardiol. 2002;9(2):246-50.

Overall, radiotracers can be used to obtain resting perfusion images for acute chest pain assessment without formal contraindications, and most patients well tolerate them. MPS with physical or pharmacological stress in low- or intermediate-risk ACS patients is recommended after stabilizing the acute condition and is usually performed during hospitalization. Stable clinical and hemodynamic conditions are paramount in both situations. The limitations of this method are its availability and cost.

5.2.5.6. Anatomical Assessment: Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography

In recent years, coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) has been increasingly used to assess patients with suspected obstructive coronary disease. It has been demonstrated that the method is more accurate in diagnosing luminal stenosis than invasive coronary angiography, especially its high negative predictive value.7575. Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG,Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, et al. iagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(21):1724-32.

76. Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M, Arbab-Zadeh A, Gottlieb NH, Clouse ME, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med 2008;359(22):2324-36.-7777. Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD, Cramer MJ, Mollet NR, van Mieghem CA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2135-44. Several studies in different clinical situations have also shown the prognostic value of CCTA regarding the presence and extent of obstructive and non-obstructive CAD, which can help with decision-making.7878. Hoffmann U, Ferencik M, Udelson JE, Picard MH, Truong QA, Patel MR, et al.; PROMISE Investigators. Prognostic Value of Noninvasive Cardiovascular Testing in Patients With Stable Chest Pain: Insights From the PROMISE Trial (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain). Circulation. 2017;135(24):2320-32.,7979. Collet C, Onuma Y, Andreini D, Sonck J, Pompilio G, Mushtaq S,et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography for heart team decision-making in multivessel coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2018 Nov 1;39(41):3689-98.

Three large multicenter randomized controlled trials have evaluated CCTA for chest pain in emergency departments, including a total of more than 3,000 patients. The multicenter CT-STAT study randomized 699 patients with low-risk chest pain to stratification with CCTA or rest-stress myocardial scintigraphy.8080. Goldstein JA, Chinnaiyan KM, Abidov A, Achenbach S, Berman DS, Hayes SW,et al. The CT-STAT (Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(14):1414-22. The CCTA strategy reduced diagnosis time by 54% and hospitalization costs by 38%, with no difference in the rate of adverse events between the two methods. The ACRIN-PA study primarily aimed at assessing the safety of CCTA for evaluating patients with low- and intermediate-risk chest pain compared to the traditional approach.8181. Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B, et al. CT angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1393-403. None of the patients with negative CCTA had the primary outcome (cardiac death or infarction) in the first 30 days after admission. Also, patients in the CCTA group had a higher rate of discharge from emergency departments (49.6% vs. 22.7%) and fewer days of hospitalization (18 hours vs. 24.8 hours, p < 0.001), with no significant differences in the incidence of coronary angiography or revascularization in the first 30 days after admission. Finally, the ROMICAT II study evaluated the emergency department length of stay and hospital costs in similar groups of patients.8282. Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, Chou ET, Woodard PK, Nagurney JT, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2012;367(4):299-308. It included 1000 patients with an average age of 54 years (46% female). The length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in patients stratified by CCTA than the traditionally-assessed group (23.2 ± 37 hours vs. 30.8 ± 28 hours; p = 0.0002). The time until an ACS diagnosis was also shorter in the CCTA group (17.2 ± 24.6 hours vs. 27.2 ± 19.5 hours; p < 0.0001). There were no significant safety differences between the groups. In the CCTA group, there was a substantial increase in patients discharged directly from the emergency department (46.7% vs. 12.4%; p = 0.001), but significantly more diagnostic tests were used in this group (97% vs. 82%, p < 0.001). Despite the higher cost associated with CCTA and a tendency toward more catheterizations and revascularizations, the overall costs were similar between the two groups (p = 0.65).

A subsequently published meta-analysis confirmed that using CCTA to assess patients with acute chest pain is associated with reduced cost and length of hospital stay, with an apparent increase in invasive angiographies and myocardial revascularizations compared to traditional approaches.8383. Hulten E, Pickett C, Bittencourt MS,Villines Tc, Petrillo S, Di Carlo MF, et al. Outcomes After Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(8):880-92.

5.2.5.6.1. Triple Rule-out

CCTA can be used in the emergency department to visualize the coronary arteries and obtain information about the aorta and pulmonary arteries, allowing assessment for acute aortic syndromes, pulmonary thromboembolism, or other thoracic changes that may be differential diagnoses of ACS (pneumonia and trauma).8484. Schertler T, Frauenfelder T, Stolzmann P, Scheffel H, Desbiolles L, Marincek B, Kaplan V, Kucher N, Alkadhi H. Triple rule-out CT in patients with suspicion of acute pulmonary embolism: findings and accuracy. Acad Radiol. 2009 Jun;16(6):708-17.,8585. Takakuwa KM, Halpern EJ, Shofer FS. A time and imaging cost analysis of low-risk ED observation patients: a conservative 64-section computed tomography coronary angiography “triple rule-out” compared to nuclear stress test strategy. Am J Emerg Med. 2011 Feb;29(2):187-95. Through specific acquisition protocols, all of this information can be obtained in a single exam. This approach is called the triple rule-out, but it should only be used in specific situations where clinical evaluation cannot direct the diagnosis.8686. Sara L, Szarf G, Tachibana A, Shiozaki AA, Villa AV, de Oliveira AC, de Albuquerque AS, et al. II Guidelines on Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Computed Tomography of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology and the Brazilian College of Radiology. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014 Dec;103(6 Suppl 3):1-86.

In summary, CCTA is a safe and efficient strategy for evaluating patients with acute low- and intermediate-risk chest pain in emergency departments, reducing the time until correct diagnosis and length of hospital stay.8787. Goehler A, Mayrhofer T, Pursnani A, Ferencik M, Lumish HS, Barth C, et al. Long-term health outcomes and cost-effectiveness of coronary CT angiography in patients with suspicion for acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020 Jan-Feb;14(1):44-54. The method's disadvantages include the use of ionizing radiation, its high cost, the need for iodinated contrast media, its limited availability in Brazil, and the fact that it cannot be used in patients with heart rates above 80 beats per minute or who cannot use beta-blockers.

5.3. Risk Stratification

5.3.1. Risk Stratification of Ischemic Cardiovascular Events

Using the TIMI IIB database, Antman et al. found the following independent markers of worse prognosis in patients with NSTE-ACS (“TIMI group risk score”): age ≥65 years, elevated biochemical markers, ST-segment depression ≥0.5 mm, ASA use in the 7 days prior to symptom onset, three or more traditional risk factors for CAD (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, DM, smoking, or family history), known CAD, and recent severe angina (< 24 hours).2828. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000 Aug 16;284(7):835-42. With one point for each item, a score of 0 to 2 is classified as low risk, 3 to 4 as intermediate risk, and 5 to 7 as high risk. This risk score has been validated in other NSTE-ACS studies. An association has been found between each marker and a higher incidence of events (death, reinfarction, and recurrent ischemia requiring revascularization) and higher risk scores. (Figure 1.3).

Due to its good discriminatory power, the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score allows more accurate stratification at both hospital admission and discharge (Figure 1.4). However, it is complex, requiring a personal computer or digital device to calculate the risk.8888. Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Van der Wef F, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ. 2006;333(7578):1091. The original GRACE score provides an estimate of in-hospital death or AMI and death 6 months after discharge. The score was later validated for risk estimation at 1 and 3 years. Eight prognostic variables of hospital mortality have been identified for this score, and the total score for a given patient is the sum of each variable:

-

Age in years - ranging from 0 (< 30) to 100 points (> 90).

-

Heart rate (bpm) - ranging from 0 (< 50) to 46 points (> 200).

-

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) - ranging from 0 (> 200) to 58 points (< 80).

-

Creatinine levels (mg/dL) - ranging from 1 (< 0.40) to 28 points (> 4.0).

-

Heart failure (Killip class) - ranging from 0 (class I) to 59 points (class IV).

-

Cardiac arrest at admission - ranging from 0 (no) to 39 points (yes).

-

ST-segment deviation - ranging from 0 (no) to 28 points (yes).

-

Increased levels of cardiac injury biomarkers - ranging from 0 points (no) to 14 points (yes).

The incidence of hospital death is ≤ 1% for low-risk patients (total scores ≤ 108), between 1% and 3% for intermediate-risk scores (between 109 and 140), and over 3% for high-risk patients (> 140).8989. Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the Global Registryof Acute Coronary Events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2345-53. A new version of the GRACE score (GRACE 2.0), developed using the same predictor variables for treatment outcome, has expanded the risk estimates for in-hospital death to 6 months, 1 year, and 3 years risk of death or AMI to 1 year.9090. Fox KAA, FitzGerald G, Puymirat E,Huang W, Carruthers K, Simon T, et al. Should patients with acute coronary disease be stratified for management according to their risk? Derivation, external validation and outcomes using the updated GRACE risk score. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004425. Table 1.5 shows the risk stratification based on clinical, ECG, and laboratory variables.

Risk stratification for death or infarction in patients with acute ischemic syndrome without ST-segment elevation9191. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, Califf RM, Cheitlin MD, Hochman JS, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Sep;36(3):970-1062.

The HEART score (discussed in item 5.4) assesses the risk of a major cardiac event (infarction, revascularization, or death) 6 weeks after initial presentation in patients with chest pain.

5.3.2. Bleeding Risk Stratification

Bleeding is associated with an adverse prognosis in NSTE-ACS, and every effort should be made to reduce it. Certain variables may help classify patients at different risk levels for major bleeding during hospitalization. Bleeding risk scores have been developed based on cohort studiesand ACS clinical studies. The CRUSADE score (www.crusadebleedingscocre.org) was developed from a cohort of 71,277 patients and subsequently validated in a cohort of 17,857 patients9292. Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, Gage BF, Rao SV, Newby LK,et al. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) Bleeding Score. Circulation. 2009;119(14):1873–82. (Table 1.6). In a Brazilian population, it predicted not only bleeding but in-hospital mortality (area under the ROC curve = 0.753, p < 0.001).9393. Nicolau JC, Moreira HG, Baracioli LM, Serrano CV Jr, Lima FG, Franken M, et al. The bleeding risk score as a mortality predictor in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013 Dec;101(6):511-8. The rate of major bleeding gradually increased as the bleeding risk score increased. By incorporating admission and treatment variables, this score's accuracy for estimating bleeding risk is relatively high. Although age is not listed among the prognostic factors in this score, it is included in the creatinine clearance calculations.

CRUSADE bleeding risk score (reference b) | Algorithm used to determine the CRUSADE risk score for major in-hospital bleeding

Another score was derived from the ACUITY and HORIZONS studies. Six independent variables (female sex, advanced age, elevated serum creatinine, elevated white blood cell count, anemia, ACS with or without ST elevation) and one treatment-related variable (heparin and GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use instead of bivalirudin alone) were identified (Table 1.7). This score identified patients at increased risk of bleeding (unrelated to CABG) and mortality after 1 year.9494. Mehran R, Pocock SJ, Nikolsky E, Clayton T, Dangas GD, Kirtane AJ,et al. A risk score to predict bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(23):2556–66.

Bleeding risk score proposed by Mehran et al.9494. Mehran R, Pocock SJ, Nikolsky E, Clayton T, Dangas GD, Kirtane AJ,et al. A risk score to predict bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(23):2556–66. Algorithm used to determine the risk of major in-hospital bleeding

Both scores were derived from cohorts in which femoral access was predominantly or exclusively used. Their prognostic value may be reduced regarding radial access.9595. Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2020 Aug 29:ehaa575.

Finally, the authors point out that no score (either for ischemic events or for hemorrhagic events) should replace clinical evaluation. Rather, they are merely tools to help doctors in their decision-making process.

5.4. Emergency Diagnostic Flowchart and Hospitalization Criteria

It is essential to develop a diagnosis flowchart for patients with chest pain, determining the criteria for early discharge and hospitalization. This can identify low-risk patients to be investigated in an outpatient setting, as well as more serious cardiac conditions that require hospitalization.

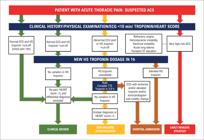

Emergency department chest pain screening is based on a brief clinical history, physical examination, 12-lead ECG within 10 minutes of arrival, and biomarker measurement. This assessment protocol is mainly aimed at early identification of high-risk patients who require hospitalization or urgent transfer for hemodynamic monitoring.

To avoid premature discharge, these patients should remain monitored in an environment where an accelerated diagnostic protocol can be used. This protocol involves serial ECG and highly sensitive troponin measurement upon arrival at the emergency department and 3 hours later. In addition to this protocol, risk scores that include demographic data, symptoms, ECG findings and biomarkers are important tools for assessing chest pain patients in the emergency department. The most commonly-used scores (HEART, ADAPT, and EDACS)9696. Six AJ, Backaus BE, Kelder SC, Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the Heart score. Neth Heart J.2008;16(6):191-6.

97. Than M, Cullen L, Aldous S, Goodacre S, Frampton CM, Troughton R, et al. 2-Hour accelerated diagnostic protocol to assess patients with chest pain symptoms using contemporary troponins as the only biomarker: the ADAPT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(23):2091-8.-9898. Than M,Flaws D, Sanders S, Doust J, Glasziou P, Kline J, et al. Development and validation of the Emergency Department Assessment of Chest pain Score and 2 h accelerated diagnostic protocol. Emerg Med Australas.2014;26(1):34-44. are summarized in Figure 1.3.

Greenslade et al. compared the effectiveness of these scores in relation to premature discharge from the emergency department, finding that all scores were effective and had very high sensitivity.9999. Greenslade JH et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of a New High-Sensitivity Troponin I Assay and Five Accelerated Diagnostic Pathways for Ruling Out Acute Myocardial Infarction and Acute Coronary Syndrome. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(4):439-51.e3.

The HEART score was developed using conventional troponin as a biomarker. However, retrospective studies that used highly sensitive troponin found results similar to those of validation studies.100100. Santi L, Farina G, Gramenzi A, Trevisani F, Baccini M, Bernardi M, et al. The HEART score with high-sensitive troponin T at presentation: ruling out patients with chest pain in the emergency room. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(3):357-64.,101101. Carlton EW, Cullen L, Than M, Gamble J, Khattab A, Greaves K. A novel diagnostic protocol to identify patients suitable for discharge after a single high-sensitivity troponin. Heart. 2015;101(13):1041-6. No studies have validated this tool for care outside the hospital. However, an ongoing study (ARTICA) aims to validate this score for pre-hospital care.102102. Aarts GWA, Camaro C, van Geuns RJ, et al. Acute rule-out of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome in the (pre) hospital setting by HEART score assessment and a single point-of-care troponin: rationale and design of the ARTICA randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2): e034403.

A HEART score from 0 to 3 identifies 35% to 46% of patients at low risk, showing high sensitivity and negative predictive value, while patients with a score of 7 to 10 are at high risk, with an event rate > 50% in 6 weeks.103103. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, Mast TP, van den Akker F, Mast EG, Monnink SH, van Tooren RM, Doevendans PA. Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART Score. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010 Sep;9(3):164-9.

104. Backus BE, Six AL, Kelder SC,Bosschaert EG, Mast A, Mosterd RF, et al. A prospective validation of the Heart score for chest pain patients at the emergency departament. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168:2153-8.

105. Six Aj, Cullen L,Backus BE, Greenslade J, Parsonage W, Aldous S, et al. The HEART score for the assessment of patients with chest pain in the emergency department: a multinational validation study. Crit Pahtw Cardiol. 2013;12(3):121-6.-106106. Van Den Berg P, Body R. The HEART score for early rule out of acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018; 7(2): 111–9. The HEART score could better distinguish low-risk patients for major cardiac events than the GRACE and TIMI scores, with a lower loss rate and greater accuracy for initial risk stratification in the emergency department.107107. Poldervaart JM, Langedijk M, Backus BE, Dekker IMC, Six AJ, Doevendans PA, Hoes AW, Reitsma JB. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Jan 15;227:656-61.,108108. Sakamoto JT, Liu N, Koh ZX, Fung NX, Heldeweg ML, Ng JC. Comparing HEART, TIMI, and GRACE scores for prediction of 30-day major adverse cardiac events in high acuity chest pain patients in the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2016 Oct 15;221:759-64.

The growing joint use of clinical data, ECG, highly sensitive troponin, and the systematized use of scores has amplified the effectiveness of diagnostic assessment protocols and the risk stratification of chest pain in the emergency department, which promotes safe early discharge and reduction of additional exams within 30 days.109109. Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, Russell GB, Hoekstra JW, Lefebvre CW, et al. The HEART Pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2):195-203.

A randomized study that compared emergency care HEART scores with chest pain found a high negative predictive value for major cardiovascular events in the first year, with no differences observed regarding hospitalization or readmission to the emergency department.110110. Stopyra JP, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, Russell G, Holkstra JW, Lefebvre CW, et al. The HEART Pathway Randomized Controlled Trial One-year Outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(1):41-50.

Thus, the impact of additional routine imaging exams on low-risk patients has been reconsidered because, despite the reduced diagnosis time, current evidence has shown that these additional tests have no verified benefit regarding the occurrence of AMI or relevant clinical events.111111. Reinhardt SW, Lin CJ, Novak E, Brown DL. Noninvasive Cardiac Testing vs Clinical Evaluation Alone in Acute Chest Pain: A Secondary Analysis of the ROMICAT-II Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):212-9.

5.5. Nurses and the Chest Pain Protocol

When performed by qualified nurses, hospital screening improves the identification of high-risk patients and reduces door-to-ECG time.112112. O’Neill L, Smith K, Currie P,Elder Dhj, Wei J, Lang CC. et al. Nurse-led Early Triage (NET) study of chest pain patients: a long term evaluation study of a service development aimed at improving the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014; 13(3):253–60. It has been shown that, in rural hospitals, emergency nurses have a high level of accuracy, which reduces waiting time and length of stay without compromising patient safety.113113. Roche TE, Gardner G, Jack L. The effectiveness of emergency nurse practitioner service in the management of patients presenting to rural hospitals with chest pain: a multisite prospective longitudinal nested cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017; 17(1): 445. Thus, nurses should be actively encouraged to participate in the screening of patients with chest pain, and the multidisciplinary team should receive continuing training about patients with chest pain.

A flowchart for emergency department treatment of patients with chest pain is shown in Figure 1.5.

Flowchart of routine diagnosis of the patient with acute chest pain in the Emergency Department. HS: highly sensitive; TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram.

6. Emergency Procedures After Risk Stratification

6.1. Indications for Early Invasive Strategy

An invasive strategy is indicated for patients with a very high risk of death (Table 1.8). This patient profile is not widely represented in randomized studies. Coronary intervention within 2 hours is indicated for these patients. When interventional cardiology service is not available, these patients should ideally be transferred to other centers.

6.2. Initial Treatment (Emergency Department/Ambulance)

6.2.1. Supplemental Oxygen

Hypoxemia and myocardial ischemia can occur due to changes in the ventilation-perfusion ratio secondary to pulmonary arteriovenous shunting (due to an increase in LV end-diastolic pressure) and interstitial and/or pulmonary alveolar edema. Hypoxemia worsens myocardial ischemia, increasing myocardial injury. O2 saturation (SaO2) should be measured using digital oximetry in pre-hospital and/or ambulance care for early diagnosis of hypoxemia.

Supplemental oxygen therapy is indicated for patients with AMI who present hypoxia with SaO2 <90% or clinical signs of respiratory distress.114114. Stub D, Smith K, Bernard S, Nehme Z, Stephenson M, Bray JE, eet al. Air versus oxygen in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2015;131(24):2143—50. However, in a randomized study of more than 6000 patients, oxygen therapy in patients with suspected ACS and SaO2 ≥90% was not associated with reduced mortality or other cardiovascular outcomes in 1 year of follow-up. 115115. Hofmann R, James SK, Jernberg T, Lindahl B, Erlinge D, Witt N,et al. Oxygen Therapy in Suspected Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 28;377(13):1240-9.

Oxygen therapy should not eliminate hypoxic respiratory stimulation when there is a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other causes of hypercapnia. Patients with pulmonary congestion, cyanosis, arterial hypoxemia, or respiratory failure should receive oxygen supplementation and be carefully monitored with serial blood gas analysis. Non-invasive ventilatory support should be used in certain cases with signs of respiratory failure, persistent pulmonary congestion, and hypoxemia. Treatment should progress to invasive ventilation in the event of circulatory shock, non-invasive ventilatory support failure, and in unstable patients indicated for urgent myocardial revascularization (PCI or CABG). The unnecessary administration of oxygen for a prolonged period can cause systemic vasoconstriction and can even be harmful.

6.2.2. Analgesia and Sedation