Abstracts

This study has been carried out at the central region of the Araguaia river on the border between the states of Goiás and Mato Grosso in the Brazilian Amazon Basin from September to December 2000. We recorded temperature fluctuation, clutch-size, incubation period and hatching success rate and hatchlings' sex ratio of five nests of Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812). Despite the relatively small sample size we infer that: a) nests of P. expansa in the central Araguaia river have a lower incubation temperature than nests located further south; however, incubation period is shorter, hatching success rate is lower and clutch-size is larger; b) Podocnemis expansa may present a female-male-female (FMF) pattern of temperature sex-determination (TSD); c) thermosensitive period of sex determination apparently occur at the last third of the incubation period; and, d) future studies should prioritize the relationship between temperature variation (i.e., range and cycle) and embryos development, survivorship and sex determination.

TSD; thermosensitive period; sex determination; reproductive biology; turtles

Este estudo foi realizado na região central do rio Araguaia, na fronteira entre os estados de Goiás e Mato Grosso, na Amazônia brasileira, durante os meses de setembro a dezembro de 2000. Além da variação da temperatura, foram avaliados o tamanho da ninhada, período de incubação, o sucesso de eclosão e a razão sexual dos filhotes recém eclodidos de cinco ninhos de Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812). Apesar do esforço amostral relativamente restrito, nós inferimos que: a) os ninhos estudados de P. expansa na região central do Rio Araguaia exibem temperaturas mais baixas do que ninhos mais ao sul, porém o período de incubação é menor, a taxa de eclosão é mais baixa e o tamanho de ninhada é maior; b) Podocnemis expansa pode mostrar um padrão fêmea-macho-fêmea (FMF) de determinação do sexo pela temperatura (TSD); c) o período termo-sensível para a determinação sexual aparentemente ocorre no último terço do período de incubação; e, d) futuros estudos devem priorizar a relação entre a variação da temperatura (i.e., amplitude e frequência) e o desenvolvimento embrionário, sobrevivência e a determinação sexual dos filhotes.

TSD; período termo-sensível; determinação sexual; biologia reprodutiva; tartarugas

Temperature-sex determination in Podocnemis expansa (Testudines, Podocnemididae)

Determinação do sexo pela temperatura em Podocnemis expansa (Testudines, Podocnemididae)

Kelly BonachI; Adriana MalvasioII; Eliana R. MatushimaIII; Luciano M. VerdadeIV

IInstituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio), Rua 229, 95, Setor Universitário, 74605-090, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. (kbonach@yahoo.com.br)

IIUniversidade Federal de Tocantins, UFT, ALCNO 14, Av. NS 15, s /n, Bloco II, Colegiado de Engenharia Ambiental, 77010-970, Palmas, TO, Brazil. (malvasio@uft.edu.br)

IIIDepartamento de Patologia, FMVZ, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. Prof. Dr. Orlando Marques de Paiva, 87, Butantã, 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. (ermatush@usp.br)

IVLaboratório de Ecologia Isotópica, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 96, 13416-000, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil. (lmverdade@usp.br)

ABSTRACT

This study has been carried out at the central region of the Araguaia river on the border between the states of Goiás and Mato Grosso in the Brazilian Amazon Basin from September to December 2000. We recorded temperature fluctuation, clutch-size, incubation period and hatching success rate and hatchlings' sex ratio of five nests of Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812). Despite the relatively small sample size we infer that: a) nests of P. expansa in the central Araguaia river have a lower incubation temperature than nests located further south; however, incubation period is shorter, hatching success rate is lower and clutch-size is larger; b) Podocnemis expansa may present a female-male-female (FMF) pattern of temperature sex-determination (TSD); c) thermosensitive period of sex determination apparently occur at the last third of the incubation period; and, d) future studies should prioritize the relationship between temperature variation (i.e., range and cycle) and embryos development, survivorship and sex determination.

Keywords: TSD, thermosensitive period, sex determination, reproductive biology, turtles.

RESUMO

Este estudo foi realizado na região central do rio Araguaia, na fronteira entre os estados de Goiás e Mato Grosso, na Amazônia brasileira, durante os meses de setembro a dezembro de 2000. Além da variação da temperatura, foram avaliados o tamanho da ninhada, período de incubação, o sucesso de eclosão e a razão sexual dos filhotes recém eclodidos de cinco ninhos de Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812). Apesar do esforço amostral relativamente restrito, nós inferimos que: a) os ninhos estudados de P. expansa na região central do Rio Araguaia exibem temperaturas mais baixas do que ninhos mais ao sul, porém o período de incubação é menor, a taxa de eclosão é mais baixa e o tamanho de ninhada é maior; b) Podocnemis expansa pode mostrar um padrão fêmea-macho-fêmea (FMF) de determinação do sexo pela temperatura (TSD); c) o período termo-sensível para a determinação sexual aparentemente ocorre no último terço do período de incubação; e, d) futuros estudos devem priorizar a relação entre a variação da temperatura (i.e., amplitude e frequência) e o desenvolvimento embrionário, sobrevivência e a determinação sexual dos filhotes.

Palavras-chave: TSD, período termo-sensível, determinação sexual, biologia reprodutiva, tartarugas.

The giant South American river turtle - Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812) - is one of the largest freshwater turtles of the world. It occurs in rivers and lakes of the Amazon and Orinoco river basins (SMITH, 1979). The females reach 80 cm of carapace length and 60 kg of body-mass, whereas the males are smaller (PRITCHARD & TREBBAU, 1984).

Decades of overexploitation resulted in dramatic population declines in many rivers of the Amazon basin (SMITH, 1979). For this reason, the Brazilian government established a "ranching" program (sensu HUTTON & WEBB, 1992) based on the protection of nesting habitats, translocation of eggs, commercial use of captive-reared turtles, and release of hatchlings in the wild near their nesting areas of origin (FAO, 1988; IBAMA, 1989).

The manipulation of nests and eggs can affect the sex of embryos, since the species presents temperature-sex determination (TSD) (ALHO et al., 1985). For conservation purposes, in theory, a 1:1 sex ratio would be more convenient (DAVENPORT, 1997). However, for commercial purposes ranchers could desire a female-biased population because females are larger than males, produce eggs, and a few males can inseminate a great number of females (VOGT, 1994).

Changes on the sex ratio of a population could in theory affect its dynamics within a few generations (CAUGHLEY, 1977). In addition, temperature of incubation can also affect other embryonic aspects in reptiles such as incubation period, integument pigmentation and post-hatching growth rate (JOANEN & MCNEASE, 1987; DEEMING & FERGUSON, 1989; WEBB & COOPER-PRESTON, 1989). For these reasons, this study aims to determine the temperature of incubation in natural nests of the species and its pattern for the sex determination of embryos.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted this study in the central region of the Araguaia river basin on the border between the states of Goiás and Mato Grosso in the Brazilian Amazon Basin from September to December 2000. We sampled five nests distributed in four sand beaches at both margins of the Araguaia river (13°21'57.6"S, 50°39'05.7"W; 13°30'12.4"S, 50°44'12.4"W; 13°23'32.3"S, 50°40'12.8"W; 13°25'11.5"S, 50°39'55.6"W). The following nest characteristics were taken: egg-chamber depth and width, distance from the water and sediment type (according to BONACH et al., 2003, 2006, 2007). Fieldwork was undertaken 7:00 to 9:30 AM or 4:00 to 6:30 PM in order to avoid egg desiccation. We implanted a data-logger Hobo TBI32-20+50 Onset (precision ± 0.1 C) in the middle of the top layer of the egg-chamber of each nest, approximately 25 to 49 cm beneath the surface (according to BONACH et al., 2006), at day 1 of the incubation period. The data-loggers were programmed to store temperature every other hour during the whole incubation period. This interval was considered short enough to prevent undetected peaks in temperature. They were tied by a thin rope to a numbered stick fixed in the ground above the nest. All nests were fenced for protection against predators and checked at day 45 of incubation in order to evaluate the development of embryos.

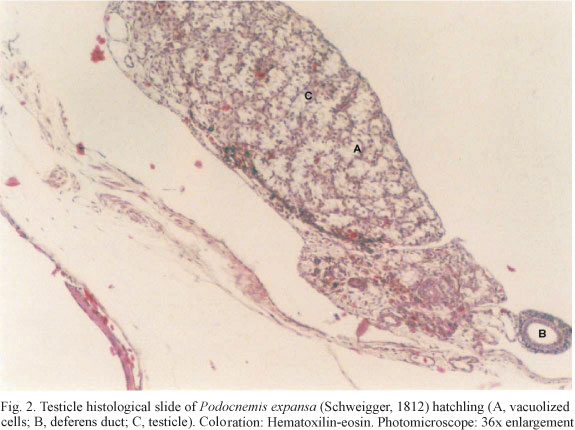

Besides temperature fluctuation we recorded clutch-size, incubation period and hatching success rate of all nests. Sex ratio of all hatchlings (n=386) was determined for the five clutches. Regression equations were established between the percentage of females per clutch and the average temperature for the three thirds of the incubation period (i.e., days 1 to 20, 21 to 40, 41 to hatching), both treated as continuous variables (SOKAL & RHOLF, 1995). In order to be sexed, hatchlings were sacrificed in sulphuric ether chambers at the age of 30 days after hatching. Gonads were extracted, fixed in formaldehyde 10%, included in paraffin and transversally cut in order to prepare histological slides. Sex identification followed the description of MALVASIO et al. (1999) (Figs 1, 2). At the time of the analyses, non-lethal sexing techniques such as hormone level (LANCE et al., 1992), geometric morphometrics (VALENZUELA et al., 2004) and laparoscopy (KUCHLING, 2006) were either considerably less accurate or not efficiently applicable to hatchlings this small (< 70g).

RESULTS

The mean incubation temperature of the nests was 30°C ± 1.1 (range: 17.8-46.3) n = 5, standard error of mean (sem) = 0.5° C. The mean clutch-size was 98.8 eggs ± 4.0 (94-104) n = 5, sem = 1.8. The mean hatching success rate was 78.2% ± 21.4 (42.6-99.0) n = 5, sem = 9.6%. The incubation results are presented in table I, and the histological slides of gonads of females and males are shown in figures 1 and 2, respectively.

The following regression equation has been successfully established between the average temperature of incubation between day 41 and hatching and the percentage of females in the clutch (Fig. 3): y = 9742 - 687.7x + 12.19x²; where: y = % of females; x = mean temperature of incubation (ºC) between day 41 of incubation and hatching); radj² = 97.7%; P = 0.011; df = 4. However, there was no correlation between the following variables: mean temperature of incubation between day 1 and day 20 and percentage of females (P = 0.536, df = 4); mean temperature of incubation between day 21 and day 40 and percentage of females (P = 0.268, df = 4); mean temperature of incubation (ºC) and incubation period (days) (P = 0.288, df = 4); mean temperature of incubation (ºC) and eclosion rate (P = 0.937, df = 4); minimum temperature of incubation (ºC) and eclosion rate (P = 0.649, df = 4); variance of incubation temperature and incubation rate (P = 0.097, df = 4); and variance of incubation temperature and eclosion rate (P = 0.716, df = 4) and incubation period (days) and eclosion rate (P = 0.716, df = 4).

DISCUSSION

Besides daily fluctuations, temperature variation is possibly also related with sand physical characteristics such as grain size distribution and thermal conductivity in P. expansa nests (SOUZA & VOGT, 1994). The optimum thermal range for the incubation of chelonian eggs is between 29ºC and 35ºC (EWERT, 1985). In this study, the average temperature of the nests is in this range. However, we found mean, minimum and maximum temperatures below those reported for the species at Araguaia National Park in the southern Araguaia river 33ºC to 35ºC, 25.8ºC and 39.1ºC, respectively (A. Malvasio, pers. observ.). VON HILDEBRAND et al. (1988) report an average temperature of 28ºC 15 cm deep for P. expansa nests in Colombia. However, SPOTILA et al. (1987) did not find significant thermal differences according to different depths in Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758) nests.

SPOTILA et al. (1987) reported a much smaller range of daily thermal fluctuation (1.5ºC) in C. mydas nests than we found for P. expansa in this study (28.5ºC). This adds some complexity to the study of the role of temperature of incubation on sex determination of freshwater turtles, in such a way that not only mean temperatures should be considered but also extreme temperatures eventually experienced by the embryos and - possibly even more important - the range and frequency of daily thermal variation as stated by GEORGES et al., (1994) for Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758). However, the relationship between incubation temperature daily fluctuation and embryos' sex determination in turtles is still unclear (VALENZUELA, 2001).

The analysis of variance of the coefficients generated by the Fourier Analysis (BLOOMFIELD, 1976) can be useful in future studies, helping detect for instance eventual intraspecific differences of the pivotal temperature, as observed by CHEVALIER et al. (1999) for Atlantic and Pacific nesting populations of Dermochelys coriacea (Linnaeus, 1766). However, this approach needs specific experimental design where both frequency and amplitude of temperature variation can be tested as distinct dependent variables.

The hatching success rate found in this study was lower than previous reports for the species in northern Amazon (88.9 %) (ZWINK & YOUNG, 1990) and southern Araguaia river (92.5%) (A. Malvasio, pers. observ.). However, the great variation of the species nesting habitats mentioned above and the small sample size of this study prevent us to take definite conclusions about this. Podocnemis expansa occurs on a broad geographic area with a considerable heterogeneity of nesting habitats in space and time. Therefore, we can expect a great variation of nesting success from year to year on a micro- as well as on a macrogeographic scale (VERDADE et al., 2002; VILLELA et al., 2008).

Although we had lower temperatures of incubation than those recorded by A. Malvasio (unpubl. data), the average period of incubation in both studies were quite similar (58.2 days in this study and 59 days, A. Malvasio, unpubl. data) and intermediate in relation to others (ALHO et al., 1979: 48 days; VON HILDEBRAND et al., 1988: 67.2 days).

The average clutch-size found in this study was slightly larger than those described for other areas within the species distribution: 91.5 eggs (Trombetas river, 1°20'S, 56°45'W, n=393) (ALHO & PÁDUA, 1982) and 95 eggs (Javaés river, 9°50' to 11°10'S, 49°56'W to 50°10'W, n=20) (A. Malvasio, pers. observ.). These differences can be related to the latitude (LITZGUS & MOUSSEAU, 2006). Oviparous reptiles usually present a positive correlation between female body-size and clutch-size (e.g. BONACH et al., 2003, 2006, 2007; LARRIERA et al., 2004; VERDADE, 2001). There can be both micro- and macrogeographic variation in females' body size (MOSKOVITS, 1988; BAUWENS & CASTILLA, 1998). Future studies on the allometry of reproduction might help us assess the female fecundity curve for a focused population and hence to establish simulation models of population fluctuation (ABERCROMBIE & VERDADE, 1995).

Hatchling turtles do not present an evident sexual dimorphism on their secondary sexual characteristics. Therefore, to sex hatchlings it is necessary to use more invasive techniques such as the determination of the testosterone seric level after FSH injection (VALENZUELA et al., 1997), gonads anatomy (MALVASIO et al., 1999, 2002), histological identification of the ovary and testis (DANNI & ALHO, 1985; MALVASIO et al., 2002) and laparoscopy (VOGT, 1994). In this study we used the histological identification of the gonads with more than 99% of secure classification, by far more accurate than the other methods.

TSD has been previously described for P. expansa with males produced at lower and females at higher temperatures (MF pattern) (ALHO et al., 1985; LANCE et al., 1992; SOUZA & VOGT, 1994). However, VALENZUELA (2001) suggests the species can also present a FMF pattern, with females produced at the extreme temperature, what is corroborated by the present study.

The thermosensitive period for sex determination in chelonians is considered to be the second third of the incubation period (BULL, 1983). However, in the present study the thermosensitive period apparently occurred after the day 40 of incubation. Considering the average incubation period of 58 days, the thermosensitive period for sex determination surprisingly seemed to occur at the last third. Some intraspecific variation can in theory occur, but its evolutionary implications are still undetermined and should be pursued in future studies. On the other hand, the implications of a late sex determination for ranching management programs are clear: sex ratio of hatchlings will be affected by early egg translocation. This should be a concern for managers, since in some conservation turtle projects, there are eggs transferences. At last, in this study we considered only mean temperatures, whereas extreme temperatures may eventually be biologically more relevant. For this reason, future studies should prioritize the relationship between temperature variation (i.e., range and cycle) and embryos development, survivorship and sex determination.

Acknowledgements. This study was supported by FAPESP (Process # 00/00215-7 and 00/00443-0), CENAQUA / IBAMA, and Agência Ambiental de Goiás. Vítor Hugo Cantarelli, Yeda L. Bataus, Paulo Souza Neto, José de Paula Moraes Filho, and Jairo A. da Silva (in memorian) provided logistical support for field studies. Paulo Bezerra e Silva Neto introduced us to the giant Amazon freshwater turtle ranching program in Goiás, Brasil.

Recebido em 7 de outubro de 2009.

Aceito em 25 de agosto de 2011.

- ABERCROMBIE, C. L. & VERDADE, L. M. 1995. Dinâmica populacional de crocodilianos: elaboração e uso de modelos. In: LARRIERA, A. & VERDADE, L. M. eds. Conservación y Manejo de los Crocodylia de America Latina Santo Tomé, Fundación Banco Bica. v. 1, p. 33-55.

- ALHO, C. J. R. & PÁDUA, L. F. M. 1982. Reproductive parameters and nesting behavior of the Amazon turtle Podocnemis expansa (Testudinata: Pelomedusidae) in Brazil. Canadian Journal of Zoology 60(1):97-103.

- ALHO, C. J. R.; CARVALHO, A. G. & PÁDUA, L. F. M. 1979. Ecologia da tartaruga da Amazônia e avaliação de seu manejo na Reserva Biológica do Trombetas. Revista Brasil Florestal l:29-47.

- ALHO, C. J.; DANNI, T. M. S. & PÁDUA, L. F. M. 1985. Temperature-dependent Sex Determination in Podocnemis expansa (Testudinata: Pelomedusidae). Biotropica 17(1):75-78.

- BAUWENS, D. & CASTILLA, A. M. 1998. Ontogenetic, sexual, and microgeographic variation in color pattern within a population of the lizard Podarcis lilfordi Journal of Herpetology 32(4):581-586.

- BLOOMFIELD, P. 1976. Fourier Analysis of Time Series: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. New York. 258p.

- BONACH, K.; PIÑA, C. I. & VERDADE, L. M. 2006. Allometry of reproduction of Podocnemis expansa in Southern Amazon basin. Amphibia-Reptilia 27(1):55-61.

- BONACH, K., LEWINGER J. F.; DA SILVA, A.P. & VERDADE, L. M. 2007. Physical characteristics of giant Amazon turtle (Podocnemis expansa) nests. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6(2):252-255.

- BONACH, K.; MIRANDA-VILELA, M. P.; ALVES, M. C. & VERDADE, L. M. 2003. Effect of translocation on egg viability of the giant Amazon river turtle (Podocnemis expansa). Chelonian Conservation Biology 4(3):712-715.

- BULL, J. J. 1983. Evolution of Sex Determining Mechanisms Menlo Park, Benjamin Cummings. 316p.

- CAUGHLEY, G. 1977. Analysis of Vertebrate Populations John Wiley & Sons, New York. 232p.

- CHEVALIER, J.; GODFREY, M. H. & GIRONDOT, M. 1999. Significant differences of temperature dependent sex determination between French Guiana (Atlantic) and Playa Grande (Costa Rica, Pacific) leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea). Annales des Sciences Naturelles 20(4):147-152.

- DANNI, T. M. S. & ALHO, C. J. R. 1985. Estudo histológico da diferenciação sexual em tartarugas recém-eclodidas (Podocnemis expansa, Pelomedusidae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 45(3):365-368.

- DAVENPORT, J. 1997. Temperature and the life-history strategies of sea turtles. Journal of Thermal Biology 22(6):479-488.

- DEEMING, D. C. & FERGUSON, M. W. J. 1989. The mechanism of temperature-dependent sex determination in crocodilians: a hypothesis. American Zoologist 29(3):973-985.

- EWERT, M. A. 1985. Embryology of turtles. In: GANS, C.; BILLETT, F. & MADERSON, P. F. A. eds. Biology of the Reptilia John Wiley & Sons, New York. v.14, p. 75-267.

- FAO. 1988. Informe del taller sobre estrategias para el manejo y el aprovechamiento racional de capibara, caiman y tortugas de água dulce Oficina Regional de la FAO para America Latina y el Caribe, São Paulo, Brasil. 121p.

- GEORGES, A.; LIMPUS, C. & STOUTJESDIJK, R. 1994. Hatchling sex in the marine turtle Caretta caretta is determined by proportion of development at a temperatura, not daily duration of exposure. Journal of Experimental Zoology 270(5):432-444.

- HUTTON, J. M. & WEBB, G. J. W. 1992. An introduction to the farming of crocodilians. In: LUXMORE, R. A. ed. Directory of Crocodilian Farming Operations 2 ed. Gland, IUCN - The World Conservation Union. p. 1-39.

- IBAMA. 1989. Projeto Quelônios da Amazônia 10 Anos Brasília, Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. 119p.

- JOANEN, T. & MCNEASE, L. 1987. The management of alligators in Louisiana, USA. In: WEBB, G. J. W.; MANOLIS, S. C. & WHITEHEAD, P. J. eds. Wildlife Management: Crocodiles and Alligators Chipping Norton, Surrey Beatty & Sons. p.33-42.

- KUCHLING, G. 2006. Endoscopic sex determination in juvenile freshwater turtles, Erymnochelys madagascariensis: morphology of gonads and accessory ducts. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 5(1):67-73.

- LANCE, V.; VALENZUELA, N. & VON HILDEBRAND, P. A. 1992. Hormonal meted to determine the sex of hatchling giant river turtles, Podocnemis expansa: application to endangered species research. American Zoology 32:125-132.

- LARRIERA, A.; PIÑA, C. I.; SIROSKI, P. & VERDADE, L. M. 2004. Allometry of reproduction in wild broad-snouted caiman (Caiman latirostris). Journal of Herpetology 38(2):141-144.

- LITZGUS, J. D. & MOUSSEAU, T. A. 2006. Geographic variation in reproduction in a freshwater turtle (Clemmys gutata). Herpetologica 62(2):132-140.

- MALVASIO, A.; GOMES, N. & FARIAS, E. C. 1999. Identificação sexual através do estudo anatômico do sistema urogenital em recém-eclodidos e jovens de Trachemys dorbignyi (Duméril & Bibron) (Reptilia, Testudines, Emydidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 16(1):91-102.

- MALVASIO, A.; SOUZA, A. M.; REIS, E. S. & FARIAS, E. C. 2002. Morfologia dos órgãos reprodutores de recém-eclodidos de Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812) e P. unifilis (Troschel, 1848) (Testudines, Pelomedusidae). Publicações Avulsas do Instituto Pau Brasil de História Natural 5:27-37.

- MOSKOVITS, D. K. 1988. Sexual dimorphism and population estimates of the two Amazonian tortoises (Geochelone carbonaria and G. denticulata) in Northwestern Brazil. Herpetologica 44(2):209-217.

- PRITCHARD, P. C. H. & TREBBAU, P. 1984. The Turtles of Venezuela Oxford, Society of the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 375p.

- SMITH, N. J. H. 1979. Quelônios aquáticos da Amazônia: um recurso ameaçado. Acta Amazonica 9(1):87-97.

- SOKAL, R. R. & ROHLF, F. J. 1995. Biometry - The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research 3 ed. New York, W.H. Freeman and Company. 887p.

- SOUZA, R. R. & VOGT, R. C. 1994. Incubation temperature influences sex and hatchling size in the Neotropical turtle Podocnemis unifilis Journal of Herpetology 28(4):453-464.

- SPOTILA, J. R.; STANDORA, E. A.; MORREALE, S. J. & RUIZ, G. J. 1987. Temperature dependent sex determination in the green turtle (Chelonia mydas): effects on the sex ratio on a natural nesting beach. Herpetologica 43(1):74-81.

- VALENZUELA, N. 2001. Constant, shift, and natural temperature effects on sex determination in Podocnemis expansa turtles. Ecology 82(11):3010-3024.

- VALENZUELA, N.; BOTERO, R. & MARTÍNEZ, E. 1997. Field study of sex determination in Podocnemis expansa from Colombian Amazonia. Herpetologica 53(3):390-398.

- VALENZUELA, N.; ADAMS, D. C.; BOWDEN, R. M. & GAUGER, A. C. 2004. Geometric morphometric sex estimation for hatchling turtles: a powerful alternative for detecting subtle sexual shape dimorphism. Copeia 4:735-742.

- VERDADE, L. M. 2001. Allometry of reproduction in broad-snouted caiman (Caiman latirostris). Brazilian Journal of Biology 61(3):171-175.

- VERDADE, L. M.; ZUCOLOTO, R. B. & COUTINHO, L. L. 2002. Microgeographic variation in Caiman latirostris Journal of Experimental Zoology 294(4):387-396.

- VILLELA, P. M. S.; COUTINHO, L. L.; PIÑA, C. I. & VERDADE, L. M. 2008. Macrogeographic genetic variation in broad-snouted caiman (Caiman latirostris). Journal of Experimental Zoology 309(10):628-636.

- VOGT, R.C. 1994. Temperature controlled sex determination as a tool for turtle conservation. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 1(2):159-162.

- VON HILDEBRAND P.; SÁENZ, C. M.; PEÑUELA, C. & CARO, C. 1988. Biologia reproductiva y manejo de la tortuga charapa (Podocnemis expansa) em el bajo Rio Caqueta. Colombia Amazonica 3:89-111.

- WEBB, G. J. W. & COOPER-PRESTON, H. 1989. Effects of incubation temperature on crocodiles and the evolution of reptilian oviparity. American Zoologist 29(3):953-971.

- ZWINK, W. & YOUNG, P. S. 1990. Desova e eclosão de Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812) (Chelonia: Pelomedusida) no Rio Trombetas, Pará, Brasil. Forest 90:34-35. 1

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

13 Dec 2011 -

Date of issue

Sept 2011

History

-

Received

07 Oct 2009 -

Accepted

25 Aug 2011