Abstracts

Calanoid copepods are abundant in South American inland waters and include widespread species, such as Boeckella gracilipes (Daday, 1902), which occurs from the Ecuador to Tierra del Fuego Island. This species occurs under various environmental conditions, and is found in oligotrophic lakes in Patagonia (39-54°S) and in shallow mountain lakes north of 39°S. The aim of the present study is to conduct a morphometric comparison of male specimens of B. titicacae collected in Titicaca and B. gracilipes collected in Riñihue lakes, with a third population of B. gracilipes collected in shallow ponds in Salar de Surire. Titicaca and Riñihue lakes are stable environments, whereas Salar de Surire is an extreme environment. These ponds present an extreme environment due to high exposure to solar radiation and high salinity levels. The results of the study revealed differences among the three populations. These results agree well with systematic descriptions in the literature on differences between the populations of Titicaca and Riñihue lakes, and population of Salar de Surire differs slightly from the other two populations. It is probable that the differences between the population of Salar de Surire and the other two populations result from the extreme environment in Salar de Surire. High exposure to solar radiation, high salinity and extreme variations in temperature enhance genetic variations that are consequently expressed in morphology.

Boeckella; fifth thoracopods; morphology; populations

Los copépodos calanoideos son abundantes en aguas continentales sudamericanas e incluyen especies de amplia distribución geográfica como Boeckella gracilipes (Daday, 1902) que se encuentra desde Ecuador hasta la isla de Tierra del Fuego. Esta especie vive bajo varias condiciones ambientales, y se encuentra en lagos oligotróficos en la Patagonia (39-54°S) y en lagunas superficiales de montaña al norte de los 39°S. El objetivo del presente trabajo es realizar un estudio comparativo morfométrico de machos de B. titicacae colectado en el lago Titicaca y B. gracilipes colectado en el lago Riñihue, ambos son ambientes estables, con una tercera población colectada en lagunas superficiales en el Salar de Surire. Estas lagunas tienen condiciones ambientales extremas debido a alta exposición a la radiación solar y altos niveles de salinidad. Los resultados del presente estudio encontraron diferencias entre las tres poblaciones. Estos resultados concordarían con las descripciones sistemáticas en la literatura sobre las diferencias de las poblaciones de los lagos Titicaca y Riñihue, y la población del salar de Surire tuvo leves diferencias respecto a las dos poblaciones anteriores. Es probable que las diferencias entre la población del Salar de Surire y las otras dos se deban a alta exposición a la radiación solar, salinidad y condiciones extremas de temperatura que acelera las diferencias genéticas las que se expresan en diferencias morfológicas.

Boeckella; quinto toracópodo; morfología; poblaciones

Morphometric differences in two calanoid sibling species, Boeckella gracilipes and B. titicacae (Crustacea, Copepoda)

Diferencias morfométricas en dos especies hermanas Boeckella gracilipes y Boeckella titicacae (Crustacea, Copepoda)

Patricio De los Ríos EscalanteI, II

IUniversidad Católica de Temuco, Facultad de Recursos Naturales, Escuela de Ciencias Ambientales, Laboratorio de Ecología Aplicada y Biodiversidad, Casilla 15-D, Temuco, Chile. (patorios@msn.com)

IINucleo de Estudios Ambientales, Universidad Católica de Temuco

ABSTRACT

Calanoid copepods are abundant in South American inland waters and include widespread species, such as Boeckella gracilipes (Daday, 1902), which occurs from the Ecuador to Tierra del Fuego Island. This species occurs under various environmental conditions, and is found in oligotrophic lakes in Patagonia (39-54°S) and in shallow mountain lakes north of 39°S. The aim of the present study is to conduct a morphometric comparison of male specimens of B. titicacae collected in Titicaca and B. gracilipes collected in Riñihue lakes, with a third population of B. gracilipes collected in shallow ponds in Salar de Surire. Titicaca and Riñihue lakes are stable environments, whereas Salar de Surire is an extreme environment. These ponds present an extreme environment due to high exposure to solar radiation and high salinity levels. The results of the study revealed differences among the three populations. These results agree well with systematic descriptions in the literature on differences between the populations of Titicaca and Riñihue lakes, and population of Salar de Surire differs slightly from the other two populations. It is probable that the differences between the population of Salar de Surire and the other two populations result from the extreme environment in Salar de Surire. High exposure to solar radiation, high salinity and extreme variations in temperature enhance genetic variations that are consequently expressed in morphology.

Keywords:Boeckella; fifth thoracopods; morphology; populations.

RESUMEN

Los copépodos calanoideos son abundantes en aguas continentales sudamericanas e incluyen especies de amplia distribución geográfica como Boeckella gracilipes (Daday, 1902) que se encuentra desde Ecuador hasta la isla de Tierra del Fuego. Esta especie vive bajo varias condiciones ambientales, y se encuentra en lagos oligotróficos en la Patagonia (39-54°S) y en lagunas superficiales de montaña al norte de los 39°S. El objetivo del presente trabajo es realizar un estudio comparativo morfométrico de machos de B. titicacae colectado en el lago Titicaca y B. gracilipes colectado en el lago Riñihue, ambos son ambientes estables, con una tercera población colectada en lagunas superficiales en el Salar de Surire. Estas lagunas tienen condiciones ambientales extremas debido a alta exposición a la radiación solar y altos niveles de salinidad. Los resultados del presente estudio encontraron diferencias entre las tres poblaciones. Estos resultados concordarían con las descripciones sistemáticas en la literatura sobre las diferencias de las poblaciones de los lagos Titicaca y Riñihue, y la población del salar de Surire tuvo leves diferencias respecto a las dos poblaciones anteriores. Es probable que las diferencias entre la población del Salar de Surire y las otras dos se deban a alta exposición a la radiación solar, salinidad y condiciones extremas de temperatura que acelera las diferencias genéticas las que se expresan en diferencias morfológicas.

Palabras-clave;Boeckella; quinto toracópodo; morfología; poblaciones.

Calanoid copepods are widespread in South American inland waters and are represented by two families, Centropagidae and Diaptomidae (SOTO & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000). Calanoids are abundant in South American inland waters because this group is tolerant to the oligotrophy of these ecosystems (DE LOS RÍOS & SOTO, 2006), whereas in Andean lakes this group tolerates high-to-moderate salinity (< 90 g/l; DE LOS RÍOS & CRESPO, 2004; DE LOS RÍOS & CONTRERAS, 2005). This group includes widespread species that are found from tropical to temperate and subpolar latitudes, such as B. gracilipes (Daday, 1902), B. gracilis (Daday, 1902) and B. poopoensis (Marsh, 1906) (MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000). Certain species inhabit different environmental gradients. For example, B. poopensis can tolerate salinities between 5-90 g/l (DE LOS RÍOS & CONTRERAS, 2005), and B. gracilipes and B. gracilis inhabit shallow ponds and large lakes (MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000). If we consider the environmental variation of these habitats and the exposure to extreme conditions that may include temperature variation, high salinity or natural ultraviolet radiation exposure, it is probable that substantial interpopulational variation occurs for each species as a consequence of the distinct geographical characteristics of different populations (SCHEIHING et al., 2010). The species cited above include B. gracilipes, which is found from Ecuador to Tierra del Fuego Island (BAYLY, 1992a; MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000). It inhabits large, deep Patagonian lakes as well as shallow Andean and Patagonian lakes and ponds. These lakes and ponds are located primarily in the northern Andes mountains or Patagonian plains. Many of these habitats are oligotrophic, with low conductivity (3.1 mS/cm) and with high exposure to natural ultraviolet radiation (DE LOS RÍOS-ESCALANTE, 2010). Boeckella titicacae Harding, 1955 was described as a species that inhabits Titicaca Lake and surrounding bodies of water (BAYLY, 1992a; SCHEIHING et al., 2010). BAYLY (1992a,b) suggested that this species differs from others in the dimensions of the fifth thoracopod. Nevertheless, BAYLY (1992a,b) does not characterise B. gracilipes and B. titicacae as different species or as morphotypes. This structure has a role in reproductive isolation because it allows the transfer of the spermatophore to the female during mating (OTHSUKA & HUYS, 1991; FERRARI & UEDA, 2005). In contrast, MENU-MARQUE et al. (2000) stated that B. titicacae is a synonym of B. gracilipes. SCHEIHING et al. (2010) rejected this argument and proposed that the populations of Titicaca Lake represent a distinct to the species B. titicacae. This proposal is based on molecular evidence and on features of body morphology described by VILLALOBOS & ZÚÑIGA (1991).

Previous descriptions proposed that the morphology of the fifth thoracopod is sensitive to extreme environments (PANDOURSKI & EVTIMOVA, 2006, 2009). It is possible to find marked differences in the morphology of the fifth thoracopod in populations of the same species, as observed for B. poppei (ADAMOWICZ et al., 2007). The aim of the present study is to perform a morphometric comparison of males of B. gracilipes collected in a Patagonian Lake (Riñihe Lake) with males of B. titicacae from Titicaca Lake and with males of a third population of B. gracilipes collected in shallow ponds of Salar de Surire. This comparison will allow evaluation of the two different viewpoints existing in the literature (VILLALOBOS & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; BAYLY, 1992a,b). Special consideration will be given to the morphometry of the fifth thoracopod, a structure that may be important for speciation because it can serve as an isolating mechanism in copepods. This structure can be used as a single trait to discriminate B. gracilipes and B. titicacae populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

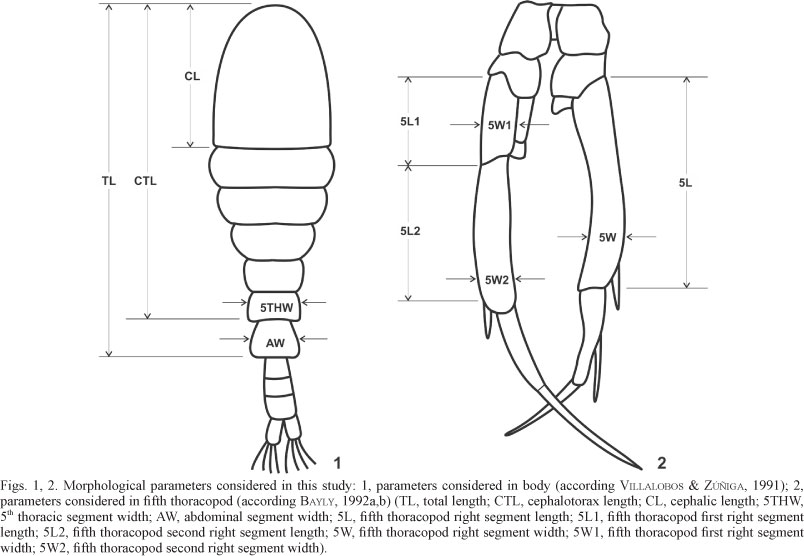

Adult males were collected at two different sites. The first site was Copacabana Bay, Titicaca Lake, Bolivia (16°09ʼS; 69°04ʼW). The specimens from this site would correspond to B. titicacae (BAYLY, 1992a,b). The annual temperature variation at the site is 3-25°C (RIECKERMAN et al., 2006; CANALES-GUTIÉRREZ, 2010). The second population of Boeckella gracilipes was sampled at the Salar de Surire (18°51ʼS; 69°07ʼW), Chile, a saline deposit with pools at 3800 m a.s.l (ZÚÑIGA et al., 1999). The pools show a wide salinity gradient and are exposed to a daily temperature variation of 15°C. The minimum temperatures varied between 0-13°C from June through September, and the maximum temperatures vary between 18-20°C in December and January (GARCÉS, 2011). The third population of Boeckella gracilipes was sampled at the oligo-mesotrophic Riñihue Lake (DADAY, 1902; VILLALOBOS & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; SOTO & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; DE LOS RÍOS & SOTO, 2007), Chile (39°49ʼS; 72°19ʼW, 107 m a.s.l) a North Patagonian Lake with a surface area of 77.5 km2 and an annual temperature variation of 9-20°C (WOELFL et al., 2003). The specimens were fixed in absolute ethanol and identified according to the descriptions in BAYLY (1992a,b). Thirty male specimens were selected for each population. A morphometric analysis of the body and fifth thoracopod was conducted (VILLALOBOS & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; Figs 1, 2). The characteristics measured were the total length (TL), cephalotorax length (CTL), cephalic length (CL), 5th thoracic segment width (5THW), abdominal segment width (AW), fifth thoracopod right segment length (5L), fifth thoracopod first right segment length (5L1), fifth thoracopod second right segment length (5L2), fifth thoracopod right segment width (5W), fifth thoracopod first right segment width (5W1), and fifth thoracopod second right segment width (5W2). The second viewpoint for morphometric comparison was included by measuring the following characteristics (BAYLY, 1992a,b): the right segment length-to-width ratio (5L/5W); the second right segment length-to-width ratio (5L2/5W2); the first right segment length-to-width ratio (5L1/5W1); and the ratio between the sum of the total lengths of the first and second segments to the total length (5L1+5L2)/5L)). The ratios between the different values of length and width and the total length were also considered. A discriminant analysis was applied to the data. SPSS v.12.0 software was used for the analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

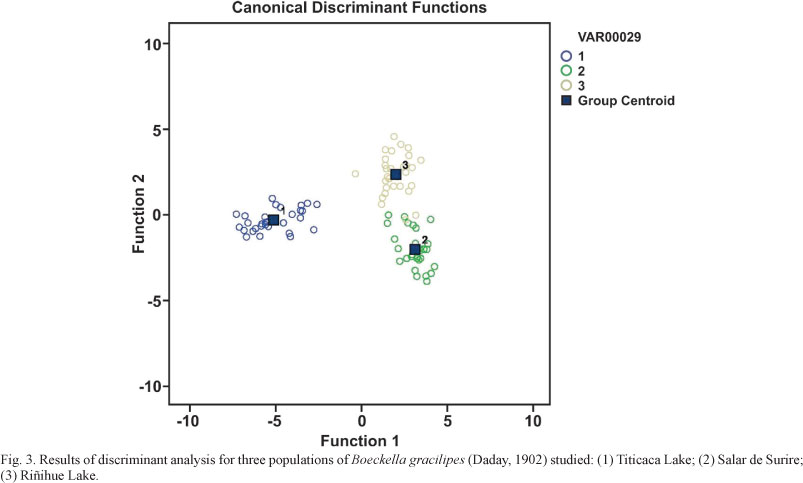

We hypothesised that the three populations can be distinguished morphologically. We therefore defined a priori three groups of specimens: Titicaca Lake, Salar de Surire and Riñihue Lake. We were particularly interested to determine the morphological distances between our populations and to compare these distances with the geographical distances. The results revealed the large morphological differences between Titicaca and Salar de Surire and between Titicaca and Riñihue Lakes. However, only a slight morphological distance was detected between the Salar de Surire and Riñihue Lake populations (Fig. 3). Almost all of the parameters studied differed significantly (Tab. I). In general, the population of Titicaca Lake is large-bodied relative to the other two populations. The measurements of the fifth thoracopod (length and width, Tab. I) showed a similar trend. In contrast, the ratios involving different measurements of the fifth thoracopod were significantly higher for the population of Riñihue Lake in comparison to the other two populations. The results indicates that the populations were distinct based on the morphometric parameters (Fig. 3). Our findings for the Titicaca Lake population agree with the description in BAYLY (1992a,b) of the differences between B. gracilipes and B. titicacae, and our findings for the population of Salar de Surire agree with the description of B. titicacae in BAYLY (1992a,b) (Tab. II). Our findings for the population collected in Riñihue Lake do not agree with this description of B. titicacae, but they agree partially with the description of B. gracilipes in BAYLY (1992a,b) (Tab. II).

According to the results of the discriminant analysis, the males of the three populations show marked morphological differences (Fig. 3). This finding may reflect the marked environmental characteristics of the different habitats. Riñihue and Titicaca Lakes are large and deep. Their environments are relatively stable. In contrast, the Salar de Surire is a habitat with extreme environmental conditions. Specifically, this habitat shows marked temperature variations and is exposed to high levels of natural ultraviolet radiation (SCHEIHING et al., 2010). The morphological variation described in the current study agrees with the descriptions in VILLALOBOS & ZÚÑIGA (1991). Those authors found variation in populations that were described in the literature as B. gracilipes, not as B. titicacae. These populations were represented by specimens from Chungará and Villarrica Lakes (Chile) and from Parinacota and Negra lagoons (Chile). The first studies of the problem do not indicate whether B. titicacae is a morphotype or subspecies of B. gracilipes or state whether the two taxa are actually different species (BAYLY, 1992a,b; MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000). Nevertheless, SCHEIHING et al. (2010) proposed that the population of Titicaca Lake belongs to the species B. titicacae. This proposal was based on morphological and molecular analysis.

A perspective from the viewpoint of reproduction would consider the important role of the fifth thoracopod pair as a mechanical isolating mechanism (MALY & MALY, 1991; OHTSUKA & HUYS, 1991; BAYLY, 1992a,b). This perspective would recognise the differences between B. titicacae and B. gracilipes, the morphometric discriminant parameters for B. gracilipes and B. titicacae described by BAYLY (1992a,b) agree with the results for the populations of Titicaca Lake and Salar de Surire (Tab. II), but these descriptions do not agree with the results for the population of Riñihue Lake (Tab. II). A possible explanation of this apparent discrepancy would be that the descriptions of B. gracilipes in BAYLY (1992b) are based on specimens collected in shallow Patagonian ponds. In that study, no descriptions are included for the populations of large, deep Patagonian lakes, such as Riñihue Lake or similar lakes, that are habitats of this species (BAYLY 1992b; MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000).

Suppose that one species, B. gracilipes (MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000; SCHEIHING et al., 2010), inhabits a wide geographical gradient and variety of habitats that includes lakes, ponds and pools between Ecuador and Tierra del Fuego island (MENU-MARQUE et al., 2000), including subsaline lakes of the South American Altiplano (BAYLY, 1993, 1995; DE LOS RÍOS & CONTRERAS, 2005). It is possible to find differences in the fifth thoracopod pair within the same species. Similarly, these descriptions are consistent with the results of comparative studies of the frontal knobs in males of the brine shrimp Artemia (Crustacea, Branchiopoda) exposed to extreme environments, primarily to variation in salinity and temperature (DE LOS RÍOS & ZÚÑIGA, 2000; DE LOS RÍOS & ASEM, 2008). The salinity tolerance of B. gracilipes is low, varying between 0.1-3.7 g/L (DE LOS RÍOS & CONTRERAS, 2005; BAYLY & BOXSHALL, 2008). This species is exposed to high levels of ultraviolet radiation in tropical and subtropical latitudes (CABRERA et al., 1997; HELBLING et al., 2002; SCHEIHING et al., 2010) and in Patagonian inland waters (MARINONE et al., 2006). Salinity variations and ultraviolet radiation exposure are accelerators of molecular changes in aquatic crustaceans (HEBERT et al., 2002). These stressors could have potential teratological effects. These effects would be expressed in morphology such morphological differences have been described for B. poppei (PANDOURSKI & CHIPIEV, 1999), a species that occurs at polar and subpolar latitudes in extreme environments with variations in temperature and levels of ultraviolet radiation similar to those cited for B. gracilipes. Similar results were described for Eurytemora velox Lilljeborg, 1853, Eucyclops serrulatus (Fisher, 1851), Paracyclops fimbriatus fimbriatus (Fisher, 1853) and Acanthocyclops vernalis (Fisher, 1853)(PANDOURSKI & EVTIMOVA, 2005).

In this scenario, the natural ultraviolet radiation exposure (ZAGARESE et al., 1998; HELBLING et al., 2002; TARTAROTTI et al., 2004) and salinity variations (DE LOS RÍOS & CONTRERAS, 2005; BAYLY & BOXSHALL, 2008) reported for the South American Altiplano and their potential effects as accelerators of molecular changes in aquatic crustacean species (HEBERT et al., 2002) would allow the occurrence of a speciation that would produce two different species, B. gracilipes and B. titicacae (SCHEIHING et al., 2010). The results of the present study reveal the differences between the populations from Riñihue Lake that was described as B. gracilipes (VILLALOBOS & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; SOTO & ZÚÑIGA, 1991; DE LOS RÍOS & SOTO, 2007) and the populations of Salar de Surire and Titicaca Lake (Fig. 3). The presence of two separate species would also be consistent with the descriptions in SCHEIHING et al. (2010). Although the morphological approach used in the present study differs from the approach used by SCHEIHING et al. (2010), the similar results of the two studies reveal the differences between B. gracilipes and B. titicacae. On this basis, it would be necessary to conduct further comparative studies of populations of both species and to include considerations of the marked environmental variation of the habitats of both species in these studies. The aim of this research would be to understand the potential genetic isolation of the populations (GAJARDO & BEARDMORE, 2002).

Acknowledgements. The present study was founded by project DGI-CDA-2007-07-01 and MECESUP UCT 0804, also it express the gratitude to Pedro Labarca for their assistance in the data collection, and the valuable assistance of Ivan Pandourski for his important comments on the manuscript.

Recebido em 26 de outubro de 2012.

Aceito em 21 de dezembro de 2012. ISSN 0073-4721

- ADAMOWICZ, S.; MENU-MARQUE, S.; HEBERT, P. & PURVIS, A. 2007. Molecular systematics and patterns of morphological evolution in the Centropagidae (Copepoda: Calanoida) of Argentina. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 90(2):279-292. BAYLY, I. A. E. 1992a. The Non-Marine Centropagidae (Copepoda, Calanoida) of the World Guides to the Identification of the Microinvertebrates of the Continental Waters of the World 2:1-30. Amsterdam, SPB Academic Publishers.

- _____. 1992b. Fusion of the genera Boeckella and Pseudoboeckella and a revision of their species from South America and subantarctic islands. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 65(1):17-63.

- _____. 1993. The fauna of athalassic saline waters in Australia and the Altiplano of South America: comparison and historical perspectives. Hydrobiologia 267(1/3):225-231.

- _____. 1995. Distinctive aspects of the zooplankton of large lakes in Australasia, Antarctica and South America. Marine and Freshwater Research 46(8):1109-1120.

- BAYLY, I. A. E. & BOXSHALL, G. A. 2008. An all-conquering ecological journey: from the sea, calanoid copepods mastered brackish, fresh and athalassic saline waters. Hydrobiologia 630(1):39-47.

- CABRERA, S.; LÓPEZ, M. & TARTAROTTI, B. 1997. Phytoplankton response to ultraviolet radiation in a high altitude Andean lake: short- versus long-term effects. Journal of Plankton Research 19(11):1565-1582.

- CANALES-GUTIÉRREZ, A. 2010. Evaluación de la biomasa y manejo de Lemna gibba (Lenteja de agua) en la bahía interior del lago Titicaca, Puno. Ecología Aplicada 9(1):91-99.

- DADAY, E. 1902. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Süsswasser-Mikrofauna von Chile. Természetrajzi Fütezek 25:436-447.

- DE LOS RÍOS, P. & ASEM, A. 2008. Comparison of the diameter of frontal knobs in Artemia urmiana Günther, 1899 (Anostraca). Crustaceana 81(11):1281-1288.

- DE LOS RÍOS, P. & CONTRERAS, P. 2005. Salinity level and occurrence of centropagid copepods (Crustacea, Copepoda, Calanoida) in shallow lakes in Andes mountains and Patagonian plains, Chile. Polish Journal of Ecology 53(3):445-450.

- DE LOS RÍOS, P. & CRESPO, J. 2004. Salinity effects on the abundance of Boeckella poopoensis (Copepoda, Calanoida) in saline ponds in the Atacama desert, northern Chile. Crustaceana 77(4):417-423.

- DE LOS RÍOS, P. & SOTO, D. 2006. Effects of the availability of energetic and protective resources on the abundance of daphniids (Cladocera, Daphniidae) in Chillean Patagonian lakes (39°-51°S). Crustaceana 79(1):23-32.

- _____. 2007. Crustacean (Copepoda and Cladocera) zooplankton richness in Chilean Patagonian lakes. Crustaceana 80(3):285-296.

- DE LOS RÍOS, P. & ZÚÑIGA, O. 2000. Comparación biométrica del lóbulo frontal en poblaciones americanas de Artemia (Anostraca, Artemiidae). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 73(1):31-38.

- DE LOS RÍOS-ESCALANTE, P. 2010. Crustacean zooplankton communities in Chilean inland waters. Crustaceana Monographs 12:1-109.

- FERRARI, F. D. & UEDA, H. 2005. Development of leg 5 of copepods belonging to the calanoid superfamily Centropagidae (Crustacea). Journal of Crustacean Biology 25(3):333-352.

- GAJARDO, G. & BEARDMORE, J. A. 2002. Coadaptation: lessons from the brine shrimp Artemia, "the aquatic Drosophila" (Crustacea, Anostraca). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 74(1):65-72.

- GARCÉS, I. 2011. Salar de Surire un ecosistema altoandino en peligro frente a escenario de cambio climático. Nexo 24:43-49.

- HELBLING, E. W.; ZARATTI, F.; ZALA, L. O.; PALENQUE, E. R.; MENCHI, C. F. & VILLAFAÑE, V. E. 2002. Mycosporine-like aminoacids protect the copepod Boeckella titicacae (Harding) against high levels of solar UVR. Journal of Plankton Research 24(3):225-234.

- HEBERT, P. D. N.; REMIGIO, E. A.; COLBOURNE, J. K.; TAYLOR, D. J. & WILSON, C. C. 2002. Accelerated molecular evolution in halophilic crustaceans. Evolution 56(5):909-926.

- MALY, E. J. & MALY, M. P. 1991. Body size and sexual size dimorphism in calanoid copepods. Hydrobiologia 391(1/3):171-177.

- MARINONE, M. C.; MENU-MARQUE, S.; AÑÓN SUÁREZ, D.; DIEGUEZ, M. C.; PÉREZ, A. P.; DE LOS RÍOS, P.; SOTO, D. & ZAGARESE, H. E. 2006. UV radiation as a potential driving force for zooplankton community structure in Patagonian lakes. Photochemistry and Photobiology 82(4):962-971.

- MENU-MARQUE, S.; MORRONE J. J. & LOCASCIO DE MITROVICH, C. 2000. Distributional patterns of the South American species of Boeckella (Copepoda, Centropagidae): a track analysis. Journal of Crustacean Biology 20(2):262-272.

- OHTSUKA, S. & HUYS, R. 1991. Sexual dimorphism in calanoid copepods: morphology and function. Hydrobiologia 453/454:441-466.

- PANDOURSKI, I. & CHIPIEV, N. 1999. Morphological variability in a Boeckella poppei Mrázek, 1901 (Crustacea: Copepoda) population from a glacial lake on the Livingston Island (the Antarctic). Bulgarian Antarctic Research Life Sciences 2:89-92.

- PANDOURSKI, I. S. & EVTIMOVA, V. V. 2005. Teratological morphology of copepods (Crustacea) from Iceland. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 57(3):305-312.

- _____. 2006. First record of Eutytemora velox (Lilljeborg, 1853) (Crustacea: Copepoda: Calanoida) in Iceland with morphological notes. Historia Naturalis Bulgarica 17(1):39-42.

- _____. 2009. Morphological variability and teratology of lower crustaceans (Copepoda and Branchiopoda) from circumpolar regions. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 61(1):55-67.

- RIECKERMANN, J.; DAEBEL, H.; RONTELTAP, M. & BERNAUER, T. 2006. Assessing the performance of international water management at lake Titicaca. CIS Working Paper 12:1-28.

- SCHEIHING, R.; CARDENAS, L.; NESPOLO, R. F.; KRALL, P.; WALZ, K.; KOHSHIMA, S. & LABARCA, P. 2010. Morphological and molecular analysis of centropagids from the high Andean plateau (Copepoda: Calanoidea). Hydrobiologia 637(1):45-52.

- SOTO, D. & ZÚÑIGA, L. R. 1991. Zooplankton assemblages of Chilean temperate lakes: a comparison with North American counterparts. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 64(3):569-581.

- TARTAROTTI, B.; BAFFICO, G.; TEMPORETTI, P. & ZAGARESE, H. 2004. Mycosporine-like amino acids in planktonic organisms living under different UV exposure conditions in Patagonian lakes. Journal of Plankton Research 26(7):753-762.

- VILLALOBOS L. & ZÚÑIGA, L. R. 1991. Latitudinal gradient and morphological variability of copepods in Chile: Boeckella gracilipes Daday. Verhandlungen International Vereinung fur Theoretische und Angewaldte Limnologie 24:2834-2838.

- WOELFL, S.; VILLALOBOS, L. & PARRA, O. 2003. Trophic parameters and method validation in a Lake Riñihue (North Patagonia, Chile) from 1978 to 1997. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 76(3):459-474.

- ZAGARESE, H. E.; TARTAROTTI, B.; CRAVERO, W. & GONZÁLEZ, P. 1998. UV damage in shallow lakes: the implications of water mixing. Journal of Plankton Research 20(8):1423-1433.

- ZÚÑIGA, O.; WILSON, R.; AMAT, F. & HONTORIA, F. 1999. Distribution of Chilean populations of the brine shrimp Artemia (Crustacea, Branchiopoda, Anostraca). International Journal of Salt Lake Research 8(1):23-40.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

22 Jan 2013 -

Date of issue

Dec 2012

History

-

Received

26 Oct 2012 -

Accepted

21 Dec 2012