ABSTRACT

Cabossous tatouay Desmarest, 1804 is considered a rare species in southern South America, and Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, records of the species are scarce and inaccurate. This study reports 40 localities for C. tatouay, and provides a map of the species' potential distribution using ecological niche modeling (ENM). The ENM indicated that in this region C. tatouay is associated with open grasslands, including the areas of "Pampas" and the open fields in the highlands of the Atlantic Forest. This study contributes to the information about the greater naked-tailed armadillo in southern Brazil, and provides data key to its future conservation.

KEYWORDS

Xenarthra; ecological niche; greater naked-tailed armadillo

RESUMO

Cabassous tatouay Desmarest, 1804 é considerada espécie rara no sul da América do Sul, apresentando registros escassos e imprecisos para o Rio Grande do Sul. O presente estudo descreve 40 localidades de ocorrência de C. tatouay e apresenta de um mapa de distribuição geográfica potencial, gerado por Modelagem Ecológica de Nicho. A modelagem de nicho sugere uma associação da espécie com áreas de matriz campestre, incluindo o Pampa e os Campos de Cima da Serra, associados à Mata Atlântica. Este estudo contribui para o melhor conhecimento do tatu-de-rabo-mole no Sul do Brasil e fornece dados-chave para sua conservação.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Xenarthra; nicho ecológico; tatu-do-rabo-mole

Cingulata belonging to the genus Cabassous Mc Mutrie, 1831, are represented by four formally described species (Gardner, 2005Gardner, A. L. 2005. Order Cingulata. In: Wilsonand, D. E. & Reeder, D. M. eds. Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference 3ed. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 94-99.) of which two occur in Brazil (Paglia et al., 2012 Paglia, A. P.; Fonseca, G. A. B.; Rylands, A. B.; Herrmann, G.; Aguiar, L. M. S.; Chiarello, A. G.; Leite, Y. L. R.; Costa, L. P.; Siciliano, S.; Kierulff, M. C. M.; Mendes, S. L.; Tavares, V. C.; Mittermeier, R. A. & Patton, J. L.. 2012. Lista Anotada dos Mamíferos do Brasil/Annotated Checklist of Brazilian Mammals. Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology6:1-76. ; Hayssen, 2014Hayssen, V. 2014. Cabassous chacoensis (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 46:24-27.): Cabassous tatouay Desmarest, 1804, and C. unicinctus (Linnaeus, 1758). The lack of physical records of these two armadillos in national scientific collections, and their infrequent appearance on local inventories, limit detailed studies on their taxonomy, phylogeny, geographical distribution, and conservation status (Fonseca et al., 1996Fonseca, G. A. B.; Hermann, G.; Leite, Y. L. R.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Rylands, A. B.& Patton, J. L. 1996. Lista anotada dos mamíferos do Brasil. Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology 4:1-38.; Nowak, 1999Nowak, R. M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World 6ed. V.1. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press 836p.; Anacleto et al., 2006Anacleto, T. C. S.; Diniz Filho, J. A. F. & Vital, M. V. C. 2006. Estimating potential geographic ranges of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in Brazil under niche-based models. Mammalia 70(3-4):202-213.).

That Cabassous tatouay, greater naked-tailed armadillo, is a poorly known species has been reported by Wetzel (1982Wetzel, R. M. 1982. Systematics, distribution, ecology, and conservation of South American Edentates. In: Mares, M. A. & Genoways, H. H. eds. Mammalian Biology in South America. Pittsburgh, Special Publication Series of the Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology, p. 34-375.), Redford (1985Redford, K. H. 1985. Foods habits of armadillos (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). In: Montgomery, G. G. ed. The Evolution and Ecology of Sloths, Armadillos, and Vermilinguas. Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 429-437.), Ubaid et al. (2010Ubaid, F. K.; Mendonça, L. S. & Maffei, F. 2010. Contribuição ao conhecimento da distribuição geográfica do Tatu-de-Rabo-Mole-Grande Cabassous tatouay no Brasil: revisão, status e coméntarios sobre a espécie. Edentata 11:22-28. ), Gonzales & Lanfranco (2010Gonzales, E. M. & Lanfranco, J. A. M. 2010. Mamíferos de Uruguay. Guía de Campo e Introducción a su Estudio y Conservación. Montevideo, Banda Oriental/Vida Silvestre/MNHN. 464p.) and Hayssen (2014Hayssen, V. 2014. Cabassous chacoensis (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 46:24-27.). The southernmost records of the species are from the Uruguayan provinces of Maldonado and Lavalleja (Coitiño et al., 2013Coitiño, H. I.; Montenegro, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Gonzáles, E. M. . & Hernández, D. 2013. Distribuición actual y potencial de Cabassous tatouay y Tamandua tetradactyla en el limite sur de su distribución: implicâncias para su conservación em Uruguay. Edentata 14:23-34.). From here the range extends northwards to the state of Pará, in northern Brazil. In between the species has been recorded from the southern, southeastern, and central regions of Brazil (Hayssen, 2014Hayssen, V. 2014. Cabassous chacoensis (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 46:24-27.). It is also found in southern Paraguay (Hayssen, 2014Hayssen, V. 2014. Cabassous chacoensis (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 46:24-27.) and northeastern Argentina, where it appears restricted to Misiones province (Abba et al., 2012Abba, A. M.; Tognelli, M. F.; Seitz, V. P.; Bender, J. B. & Vizcaíno, S. F. 2012. Distribution of extant xenarthrans (Mammalia: Xenarthra) in Argentina using species distribution models. Mammalia 76:123-136.).

In southern Brazil, the species appears in the regional listings of both Ihering (1892Ihering, H. V. 1892. Os mamíferos do Rio Grande do Sul. Annuário do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul 1892:43-77.) and Silva (1994Silva, F. 1994. Mamíferos silvestres do Rio Grande do Sul Porto Alegre, Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. 255p.), but in both cases without any information on location or habitat. Oliveira & Vilella (2003Oliveira, E. V. & Vilella, F. S. 2003. Xenarthros. In: Fontana, C. S.; Bencke, G. A.& Reis, R. E.eds. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do SulPorto Alegre, EDIPUCRS, p. 487-492.) mentioned the occurrence of C. totouay in the west and southwest regions of the state, and Kasper et al. (2007Kasper, C. B.; Feldens, M. J.; Mazim, F. D.; Schneider, A.; Cademartori, C. V. & Grillo, H. C. Z. 2007. Mamíferos do Vale do Taquari, região central do Rio Grande do Sul. Biociências 15:53-62. ) indicated the occurrence of this species in the central region of RS, where it may be in population decline. The only accurate and confirmed record is from an archaeological site located at east of State, associated to pioneer formations under fluvial influence of the Rio Grande basin. An assessment of potential geographic ranges of armadillos in Brazil (Anacleto et al., 2006Anacleto, T. C. S.; Diniz Filho, J. A. F. & Vital, M. V. C. 2006. Estimating potential geographic ranges of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in Brazil under niche-based models. Mammalia 70(3-4):202-213.) highlighted the small number of C. tatouay records, and suggested that Brazilian Pampa was not a favored habitat. Indeed, C. tatouay does seem relatively uncommon in this habitat, except in Uruguay, the southern limit of its distribution, where some 10 records are available from the Pampas (Coitiño et al., 2013Coitiño, H. I.; Montenegro, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Gonzáles, E. M. . & Hernández, D. 2013. Distribuición actual y potencial de Cabassous tatouay y Tamandua tetradactyla en el limite sur de su distribución: implicâncias para su conservación em Uruguay. Edentata 14:23-34.).

There are few ecological data from the northern-most part of the range of C. tatouay. Medri et al. (2011Medri, I. M.; Mourão, G. & Rodrigues, F. H. G.2011. Ordem Xenarthra. In: Reis, N. R.; Peracchi, A. L.; Pedro, W. A. & LIMA, I. P. eds. Mamíferos do Brasil. Londrina, Midiograf, p. 71-99.) pointed to the occurrence of the species in forested areas, and its absence from areas of intensive agriculture or severely degraded localities. According to Carter & Encarnação (1983Carter, T. S. & Encarnação, C. D. 1983. Characteristics and Use of Burrows by Four Species of Armadillos in Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy 64:103-108. ), C. tatouay changes its burrow every day, and does not use the same shelter twice. Medri et al. (2011)Medri, I. M.; Mourão, G. & Rodrigues, F. H. G.2011. Ordem Xenarthra. In: Reis, N. R.; Peracchi, A. L.; Pedro, W. A. & LIMA, I. P. eds. Mamíferos do Brasil. Londrina, Midiograf, p. 71-99. reported that the species has a home range of some 409 hectares, feeds exclusively on ants, is predominantly crepuscular or nocturnal, and has only a single offspring at any one time.

The greater naked-tailed armadillo is considered of Least Concern at the global level, with only minor conservation action being proposed (Gonzales & Abba, 2014Gonzalez, E. & Abba, A. M. 2014. Cabassous tatouay. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.1. Avaliable at < Avaliable at http://www.iucnredlist.org

>. Accessed on 16 June 2015.

http://www.iucnredlist.org...

). However, all available information on the species in Brazil has been derived from a handful of wild-based observations, and these are insufficient to assess the status of the species in the country (Chiarello et al., 2008Chiarello, A. G.; Aguiar, L. M. S.; Cerqueira, R.; Melo, F. R.; Rodrigues, F. H. G. & Silva, V. M. 2008. Mamíferos ameaçados de extinção do Brasil. In: Machado, A. B. M.; Drummond, G. M. & Paglia, A. P. orgs. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. Belo Horizonte, Brasília, Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Fundação Biodiversitas, p. 681-702.). Cabassous tatouay is considered vulnerable to extinction in Uruguay, and is a national priority for conservation (Gonzales & Lanfranco, 2010Gonzales, E. M. & Lanfranco, J. A. M. 2010. Mamíferos de Uruguay. Guía de Campo e Introducción a su Estudio y Conservación. Montevideo, Banda Oriental/Vida Silvestre/MNHN. 464p.). With regard to Rio Grande do Sul, there is no precise information on the population status or even the basic inventories to enable analysis of the current distribution of the species (Oliveira & Vilella, 2003Oliveira, E. V. & Vilella, F. S. 2003. Xenarthros. In: Fontana, C. S.; Bencke, G. A.& Reis, R. E.eds. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do SulPorto Alegre, EDIPUCRS, p. 487-492.).

Thus, the present study aims to contribute to the knowledge of C. tatouay in RS by reporting new areas of occurrence, expanding the known distribution of the species, and providing a map of its potential distribution using ecological niche modeling.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cabassous tatouay distributional data. All records of C. tatouay were obtained between 2000 and 2012 through monitoring and inventories of mammals in different regions of the Rio Grande do Sul State, plus records of opportunity. The main methods employed were: camera trap records, searching for tracks and signs, nocturnal censuses, ad libitum observations, and monitoring mammalian roadkill on regional highways. The results were part of a general program of mammal surveys in the state and did not specifically target C. tatouay and covered a range of regional environments. Thus, any reported habitat selection is not the result of selectivity in survey design.

Specimens found dead and with good conditions were deposited in the scientific collections of the Museu de Ciências Naturais, Universidade Luterana do Brasil, Canoas, RS. For specific determination of C. tatouay, we followed Eisenberg & Redford (1999Eisenberg, J. F. & Redford, K. H. 1999. Mammals of the Neotropics: the central Neotropics. Volume 3. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. 339p.), Achaval et al. (2007Achaval, F.; Clara, M. & Olmos, M. C. 2007. Mamíferos de la República Oriental del Uruguay, guia fotográfica. 2ed. Montevideo, Zonalibro Indústria Gráfica. 216p.), Medri et al. (2011Medri, I. M.; Mourão, G. & Rodrigues, F. H. G.2011. Ordem Xenarthra. In: Reis, N. R.; Peracchi, A. L.; Pedro, W. A. & LIMA, I. P. eds. Mamíferos do Brasil. Londrina, Midiograf, p. 71-99.), and Gonzales & Lanfranco (2010Gonzales, E. M. & Lanfranco, J. A. M. 2010. Mamíferos de Uruguay. Guía de Campo e Introducción a su Estudio y Conservación. Montevideo, Banda Oriental/Vida Silvestre/MNHN. 464p.) in using the following as diagnostic external characteristics: body large and robust (6-12 kg), shell with 10-13 flexible dorsal bands and tail lacking osteoderms; head large, cephalic shield with symmetrical plates; ears large, widely-separated, and with granular external surface; snout short and wide; front and back legs both with five digits, and large nails, especially on the third digit; dental formula varying between 7 to 10 upper, and 8 to 9 lower teeth. Sampling sites were widely dispersed throughout RS state, and a variety of habitat types including forests, open fields in the highlands of the Atlantic Forest, and formations of Brazilian Pampas. All records of C. tatouay were georeferenced.

Ecological niche modeling. A potential distribution map was produced using the Maxent algorithm version 3.2.1 (Phillips et al., 2006Phillips, S. J.; Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecology Model190:231-259.) by applying the basic parameters suggested by the program and deploying randomization of training points (random seed). Overlapping or very close points were removed, and C. tatouay records were divided into two sets, one for training (75% of points to run the model) and the other for testing (25% of points to evaluate the model). The model of potential geographical distribution generated by Maxent was then imported and edited by the ArcView 3.3 program.

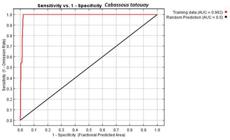

The quality of the model prediction was evaluated using ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristics) that relates the sensitivity and specificity parameters of the model (Phillips et al., 2006Phillips, S. J.; Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecology Model190:231-259.). The calculation of the area under the ROC curve, also known as Area Under the Curve (AUC), provides a single measure of the model performance. The AUC ranges from 0 to 1, where values close to 1 indicate high performance, while those less than 0.5 indicate poor performance (Peterson et al., 2008Peterson, A. T.; Papes, M. & Soberón, J. 2008. Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecology Model 21:63-72.). To evaluate the sensitivity, we tracked the number of test points present in the area predicted by the model (Elith et al., 2006Elith, J. C. C.; Graham, R.; Anderson, M.; Dudík, S.; Ferrier, A.; Guisan, R.; Hijmans, F.; Huettmann, J.; Leathwick, A.; Lehmann, J. L. I.; Lohmann, L.; Loisell, B.; Manion, G.; Moritz, C.; Nakamura, M.; Nakazawa, Y.; Overton, J.; Peterson, A. T.; Phillips, S.; Richardson, K.; Scachetti-Pereira, R.; Schapire, E.; Soberón, J.; Williams, S.; Wisz, M. & Zimmerman, N. 2006. Novel methods improve prediction of species distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29:129-151.). To identify the variables that most influenced the distribution of C. tatouay, we ran a Jackknife test using Maxent (Phillips et al., 2006Phillips, S. J.; Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecology Model190:231-259.). This test measures the predictive effects of each variable in the model when verifying the quality of the model only with the variable in test and the omitted variable in test.

Seven predictor variables were used (Tab. I). These variables were obtained from the Modeling Group for Biodiversity Studies, of the Brazilian Institute for Space Research, AMBDATA/INPE (http://www.dpi.inpe.br/Ambdata/referencias.php). All environmental information was organized in grids in the ASCII-raster format, using the geodetic coordinate projection system "Lat Long," Datum WGS-84, with a spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds or approximately 1 km2.

Predictor variables used in the ecological niche modeling of Cabassous tatouay Desmarest, 1804 for the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

RESULTS

Field observations registered 40 occurrences of C. tatouay from 30 municipalities within RS. Twenty-seven sites were located in the Pampa biome, eleven in the Atlantic Forest, and two in the areas of transition from Pampa biome to Atlantic Forest (IBGE, 2004IBGE. 2004. Mapa de Vegetação do Brasil, Esc. 1:5.000.000. Available at <Available at http://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Cartas_e_Mapas/Mapas_Murais/

>. Accessed on 20 October 2012.

http://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Cartas_e_Mapas/Ma...

) (Tab. II). A total of twelve specimen records were obtained by identifying tracks, ten individuals were directly observed, nine carcasses were obtained from hunters, five carcasses were found as highway roadkill, and four individuals were recorded with camera traps.

For ecological niche modeling, 37 spatially unique records were used. Annual average temperature was the variable that most influenced the model distribution of C. tatouay, followed by precipitation in driest month (Tab. II).

Confirmed localities for Cabassous tatouay Desmarest, 1804 in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2000-2012, with record date, type of observation, municipality, biome, anthropogenic matrix, and human density (DO, Direct observation; PP, Pawprint; HU, Hunted; RK, Roadkill; CT, Camera trap; RE, Record; BI, Biome; AF, Atlantic Forest; PA, Pampa).

The operating characteristic (OC) curve evaluates the performance of the model. OC analysis gave a value of 0.99, which is regarded as excellent, and indicates that the results were not random. As evaluated by the test points, model sensitivity was 100%, and all the test points positioned in the potential distribution area (Fig. 1).

Area Under the Curve produced by the Maxent algorithm, plus sensitivity and specificity response of the ecological niche model for Cabassous tatouay Desmarest, 1804 for the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

DISCUSSION

Ecological niche modeling results (Fig. 2) showed the areas most ecological and geographic suitable for C. tatouay were associated with the two main mountainous areas of Rio Grande do Sul State, and the valley between them. In our model the areas with highest scores were Serra Geral in northeastern (with altitudes of 700 - 1400 m), "Serra do Sudeste" in southeast, and the "Planície Central", a relatively flat area, between these two montainous regions (Fig. 2). Gallery forests appear to be strongly linked with C. tatouay presence, especially when associated with areas o rock-rich natural grasslands. However, even disturbed areas with farming and the extensive cultivation of soya, rice, or exotic trees were used by the greater naked-tailed armadillo. In the generated ecological niche model, the most important variables for determining C. tatouay presence were average annual temperature (responsible for 52.3% of the variance), and precipitation in driest month (28.3%). These variables were similar to other models for the species, like presented by Abba et al. (2012Abba, A. M.; Tognelli, M. F.; Seitz, V. P.; Bender, J. B. & Vizcaíno, S. F. 2012. Distribution of extant xenarthrans (Mammalia: Xenarthra) in Argentina using species distribution models. Mammalia 76:123-136.) and Coitiño et al. (2013Coitiño, H. I.; Montenegro, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Gonzáles, E. M. . & Hernández, D. 2013. Distribuición actual y potencial de Cabassous tatouay y Tamandua tetradactyla en el limite sur de su distribución: implicâncias para su conservación em Uruguay. Edentata 14:23-34.).

Model ecological niche of Cabassous tatouay Desmarest, 1804 produced by Maxent algorithm, and a visualization of its potential distribution in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Stars indicate new locality records for the species, circles indicate historical records to the present study within South America.

Because of the heterogeneity of sampling methods, it is impossible to fully quantify the expended sampling effort. However, it is possible to we are confident that the absence of records in north-northwest portion of the state reflects, if not absence, low densities of this species. There were also no records of C. tatouay in pioneer formations under marine influence in the east. However, it is interesting to note that 67.5% of our records came from Pampas region, a biome that the species is not considered to prefer (Anacleto et al., 2006Anacleto, T. C. S.; Diniz Filho, J. A. F. & Vital, M. V. C. 2006. Estimating potential geographic ranges of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in Brazil under niche-based models. Mammalia 70(3-4):202-213.). We present here more records of C. tatouay for Pampas region than Anacleto et al. (2006)Anacleto, T. C. S.; Diniz Filho, J. A. F. & Vital, M. V. C. 2006. Estimating potential geographic ranges of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in Brazil under niche-based models. Mammalia 70(3-4):202-213. for all Brazil. Exactly why this is so requires further consideration, since the species seems genuinely uncommon in Pampas landscapes in neighboring Argentina and Uruguay (Abba et al., 2012Abba, A. M.; Tognelli, M. F.; Seitz, V. P.; Bender, J. B. & Vizcaíno, S. F. 2012. Distribution of extant xenarthrans (Mammalia: Xenarthra) in Argentina using species distribution models. Mammalia 76:123-136.; Coitiño et al., 2013Coitiño, H. I.; Montenegro, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Gonzáles, E. M. . & Hernández, D. 2013. Distribuición actual y potencial de Cabassous tatouay y Tamandua tetradactyla en el limite sur de su distribución: implicâncias para su conservación em Uruguay. Edentata 14:23-34.).

Approximately 12.5% of the records came from roadkill. While this demonstrates that highways may be a threat to the conservation of C. tatouay. The extent of this impact cannot currently be measured, because of the lack of systematic sampling targeted at locations where roadkill was confirmed. Although the available studies on this subject are scarce and have not reported C. tatouay (Rosa & Mahus, 2004Rosa, A. O. & Mauhs, J. 2004. Atropelamento de animais silvestres na rodovia RS-040. Caderno de Pesquisa Série Biologia 16(1):35-42. ; Tumeleiro et al., 2006Tumeleiro, L. K.; Koenemann, J.; Ávila, M. C. N.; Pandolfo, F. R. & Oliveira, E. V. 2006. Notas sobre mamíferos da região de Uruguaiana: estudo de indivíduos atropelados com informações sobre a dieta e conservação Biodiversidade Pampeana4(1):38-41. ; Hengemühle & Cademartori, 2008Hengemühle, A. & Cademartori, C. V. 2008. Levantamento de mortes de vertebrados silvestres devido a atropelamento em um trecho da estrada do mar (RS-389). Biodiversidade Pampeana 6(2):4-10.), Fontana et al. (2003Fontana, C. S.; Vélez, E.; Bencke, G. A. & Reis, R. E. orgs. 2003. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do Sul Porto Alegre, EDIPUCRS/Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. 632p.) listed roadkill as the direct cause of population decline of 2.5% of the species of conservation interest in RS. Indeed the frequency of roadkill may be higher than estimated here, since many animals survive the initial impact only to die concealed in vegetation a few meters from the road. Moreover, unless surveys are frequent, roadkill frequencies may be underestimated because of scavengers: at least some of which are human (on one occasion, a local habitant asked for the carcass while we were examining it). In combination, this shows the need for urgent action by the licensing agencies in Rio Grande do Sul state to implement existing regulations on the construction of highways in manners that mitigate and minimize the potential for vehicle-related deaths in wildlife living in proximity to highways, and to do this for both existing highways and those under construction or undergoing widening or expansion.

About 22% of records were obtained from local hunters, confirming the data of Peters et al. (2011Peters, F. B.; Roth, P. R. O.; Piske, A. D.; Pereira, M. S. & Christoff, A. U. 2011. Aspectos da caça e perseguição aplicada a mastofauna na APA do Ibirapuitã, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Biodiversidade Pampeana9(1):16-19.), who reported Dasypodidae to be one of the mammalian groups most impacted by hunting in southwestern RS. Although illegal, this activity is driven by the consumption of meat, armadillo hunting is not the results of nutritional need, but instead is a recreational and cultural practice. As the naked-tailed armadillo is the largest species of armadillo, found in the RS, it is preferred over smaller species such as Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758, Dasypus hybridus Desmarest, 1804, and Euphractus sexcinctus Linnaeus, 1758.

The records collected in the current study, are insufficient to estimate population trends for C. tatouay. However, it is possible to say that C. tatouay can currently be considered one of the rarest species of mid-size mammal in RSOther species of armadillo are easily recorded as roadkill, and by direct observations and camera traps. When compared with the number of records obtained during the study of other Cingulata and of species from other groups of mid-sized mammals considered as endangered (such as carnivores), it is likely that C. tatouay is now under the threat of regional extinction in RS state. Therefore, it is suggested that conservation actions be directed at C. tatouay, especially in regions indicated as having high ecological and geographical suitability for the species. These actions could involve: the creation of local of field stations or nature parks that have armadillo protection as their prime focus; the implementation of wildlife-friendly construction for existing and new highways; active counter-hunting surveillance; enforcement of existing legislation; and encouraging future studies that monitor C. tatouay population trends in RS (as well other areas within its natural range).

Acknowledgments

We thank Lissandro Moraes and Mauricio Pereira da Silveira for making the specimen record available. Adrian A. Barnett for English review and comments to manuscript. Permission for collecting specimens was granted by IBAMA and FEPAM (license number 158/2009, 185/2009, 239/2009, 06/2010, 611/2011-DL, among the others).

REFERENCES

- Abba, A. M.; Tognelli, M. F.; Seitz, V. P.; Bender, J. B. & Vizcaíno, S. F. 2012. Distribution of extant xenarthrans (Mammalia: Xenarthra) in Argentina using species distribution models. Mammalia 76:123-136.

- Achaval, F.; Clara, M. & Olmos, M. C. 2007. Mamíferos de la República Oriental del Uruguay, guia fotográfica. 2ed. Montevideo, Zonalibro Indústria Gráfica. 216p.

- Anacleto, T. C. S.; Diniz Filho, J. A. F. & Vital, M. V. C. 2006. Estimating potential geographic ranges of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in Brazil under niche-based models. Mammalia 70(3-4):202-213.

- Carter, T. S. & Encarnação, C. D. 1983. Characteristics and Use of Burrows by Four Species of Armadillos in Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy 64:103-108.

- Chiarello, A. G.; Aguiar, L. M. S.; Cerqueira, R.; Melo, F. R.; Rodrigues, F. H. G. & Silva, V. M. 2008. Mamíferos ameaçados de extinção do Brasil. In: Machado, A. B. M.; Drummond, G. M. & Paglia, A. P. orgs. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. Belo Horizonte, Brasília, Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Fundação Biodiversitas, p. 681-702.

- Coitiño, H. I.; Montenegro, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Gonzáles, E. M. . & Hernández, D. 2013. Distribuición actual y potencial de Cabassous tatouay y Tamandua tetradactyla en el limite sur de su distribución: implicâncias para su conservación em Uruguay. Edentata 14:23-34.

- Eisenberg, J. F. & Redford, K. H. 1999. Mammals of the Neotropics: the central Neotropics. Volume 3. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. 339p.

- Elith, J. C. C.; Graham, R.; Anderson, M.; Dudík, S.; Ferrier, A.; Guisan, R.; Hijmans, F.; Huettmann, J.; Leathwick, A.; Lehmann, J. L. I.; Lohmann, L.; Loisell, B.; Manion, G.; Moritz, C.; Nakamura, M.; Nakazawa, Y.; Overton, J.; Peterson, A. T.; Phillips, S.; Richardson, K.; Scachetti-Pereira, R.; Schapire, E.; Soberón, J.; Williams, S.; Wisz, M. & Zimmerman, N. 2006. Novel methods improve prediction of species distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29:129-151.

- Fonseca, G. A. B.; Hermann, G.; Leite, Y. L. R.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Rylands, A. B.& Patton, J. L. 1996. Lista anotada dos mamíferos do Brasil. Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology 4:1-38.

- Fontana, C. S.; Vélez, E.; Bencke, G. A. & Reis, R. E. orgs. 2003. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do Sul Porto Alegre, EDIPUCRS/Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. 632p.

- Gardner, A. L. 2005. Order Cingulata. In: Wilsonand, D. E. & Reeder, D. M. eds. Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference 3ed. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 94-99.

- Gonzalez, E. & Abba, A. M. 2014. Cabassous tatouay. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.1. Avaliable at < Avaliable at http://www.iucnredlist.org >. Accessed on 16 June 2015.

» http://www.iucnredlist.org - Gonzales, E. M. & Lanfranco, J. A. M. 2010. Mamíferos de Uruguay. Guía de Campo e Introducción a su Estudio y Conservación. Montevideo, Banda Oriental/Vida Silvestre/MNHN. 464p.

- Hayssen, V. 2014. Cabassous chacoensis (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammalian Species 46:24-27.

- Hengemühle, A. & Cademartori, C. V. 2008. Levantamento de mortes de vertebrados silvestres devido a atropelamento em um trecho da estrada do mar (RS-389). Biodiversidade Pampeana 6(2):4-10.

- IBGE. 2004. Mapa de Vegetação do Brasil, Esc. 1:5.000.000. Available at <Available at http://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Cartas_e_Mapas/Mapas_Murais/ >. Accessed on 20 October 2012.

» http://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Cartas_e_Mapas/Mapas_Murais/ - Ihering, H. V. 1892. Os mamíferos do Rio Grande do Sul. Annuário do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul 1892:43-77.

- Kasper, C. B.; Feldens, M. J.; Mazim, F. D.; Schneider, A.; Cademartori, C. V. & Grillo, H. C. Z. 2007. Mamíferos do Vale do Taquari, região central do Rio Grande do Sul. Biociências 15:53-62.

- Medri, I. M.; Mourão, G. & Rodrigues, F. H. G.2011. Ordem Xenarthra. In: Reis, N. R.; Peracchi, A. L.; Pedro, W. A. & LIMA, I. P. eds. Mamíferos do Brasil. Londrina, Midiograf, p. 71-99.

- Nowak, R. M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World 6ed. V.1. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press 836p.

- Oliveira, E. V. & Vilella, F. S. 2003. Xenarthros. In: Fontana, C. S.; Bencke, G. A.& Reis, R. E.eds. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do SulPorto Alegre, EDIPUCRS, p. 487-492.

- Paglia, A. P.; Fonseca, G. A. B.; Rylands, A. B.; Herrmann, G.; Aguiar, L. M. S.; Chiarello, A. G.; Leite, Y. L. R.; Costa, L. P.; Siciliano, S.; Kierulff, M. C. M.; Mendes, S. L.; Tavares, V. C.; Mittermeier, R. A. & Patton, J. L.. 2012. Lista Anotada dos Mamíferos do Brasil/Annotated Checklist of Brazilian Mammals. Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology6:1-76.

- Peters, F. B.; Roth, P. R. O.; Piske, A. D.; Pereira, M. S. & Christoff, A. U. 2011. Aspectos da caça e perseguição aplicada a mastofauna na APA do Ibirapuitã, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Biodiversidade Pampeana9(1):16-19.

- Peterson, A. T.; Papes, M. & Soberón, J. 2008. Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecology Model 21:63-72.

- Phillips, S. J.; Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecology Model190:231-259.

- Redford, K. H. 1985. Foods habits of armadillos (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). In: Montgomery, G. G. ed. The Evolution and Ecology of Sloths, Armadillos, and Vermilinguas. Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 429-437.

- Rosa, A. O. & Mauhs, J. 2004. Atropelamento de animais silvestres na rodovia RS-040. Caderno de Pesquisa Série Biologia 16(1):35-42.

- Silva, F. 1994. Mamíferos silvestres do Rio Grande do Sul Porto Alegre, Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. 255p.

- Tumeleiro, L. K.; Koenemann, J.; Ávila, M. C. N.; Pandolfo, F. R. & Oliveira, E. V. 2006. Notas sobre mamíferos da região de Uruguaiana: estudo de indivíduos atropelados com informações sobre a dieta e conservação Biodiversidade Pampeana4(1):38-41.

- Ubaid, F. K.; Mendonça, L. S. & Maffei, F. 2010. Contribuição ao conhecimento da distribuição geográfica do Tatu-de-Rabo-Mole-Grande Cabassous tatouay no Brasil: revisão, status e coméntarios sobre a espécie. Edentata 11:22-28.

- Wetzel, R. M. 1982. Systematics, distribution, ecology, and conservation of South American Edentates. In: Mares, M. A. & Genoways, H. H. eds. Mammalian Biology in South America. Pittsburgh, Special Publication Series of the Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology, p. 34-375.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

30 June 2015

History

-

Received

22 Nov 2014 -

Accepted

25 June 2015