Abstract

Blood infection by the simian parasite, Plasmodium simium, was identified in captive (n = 45, 4.4%) and in wild Alouatta clamitans monkeys (n = 20, 35%) from the Atlantic Forest of southern Brazil. A single malaria infection was symptomatic and the monkey presented clinical and haematological alterations. A high frequency of Plasmodium vivax-specific antibodies was detected among these monkeys, with 87% of the monkeys testing positive against P. vivax antigens. These findings highlight the possibility of malaria as a zoonosis in the remaining Atlantic Forest and its impact on the epidemiology of the disease.

simian malaria; Plasmodium simium; New World monkey

Plasmodium infections caused by Plasmodium brasili- anum or Plasmodium simium have been identified in New World monkeys. P. brasilianum naturally infects several species of monkeys from a large area in Latin America and seems to be identical to Plasmodium malariae, a human malaria parasite (Coatney 1971Coatney GR 1971. The simian malarias: zoonoses, anthroponoses or both? Am J Trop Med Hyg 20: 795-803., Cochrane et al. 1985Cochrane AH, Barnwell JW, Collins WE, Nussenzweig RS 1985. Monoclonal antibodies produced against sporozoites of the human parasite Plasmodium malariae abolish infectivity of sporozoites of the simian parasite Plasmodium brasilianum. Infect Immun 50: 58-61., Leclerc et al. 2004Leclerc MC, Hugot JP, Durand P, Renaud F 2004. Evolutionary relationships between 15 Plasmodium species from new and old world primates (including humans): an 18S rDNA cladistic analysis. Parasitology 129: 677-684.). Likewise, P. simium, restricted to the Atlantic Forest regions, is indistinguishable from the human parasite Plasmodium vivax (Collins et al. 1969Collins WE, Contacos PG, Guinn EG 1969. Observations on the sporogonic cycle and transmission of Plasmodium simium Da Fonseca. J Parasitol 55: 814-816., Deane 1988Deane LM 1988. Malaria studies and control in Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 38: 223-230.). P. simium was first identified by da Fonseca (1951)da Fonseca F 1951. Plasmódio de primata do Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 49: 543-551. in a monkey from the state of São Paulo (SP), Brazil and was described to naturally infect only three species: Alouatta caraya (black howler monkey), Alouatta clamitans (southern brown howler monkey) and Brachytelles arachnoides (woolly spider monkey) (Deane et al. 1966Deane LM, Deane MP, Ferreira Neto J 1966. Studies on transmission of simian malaria and on the natural infection of man with Plasmodium simium in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 35: 805-808., 1968Deane M, Neto JF, Sitônio JG 1968. New host of natural Plasmodium simium and Plasmodium brasilianum: mono, Brachyteles arachnoides. J Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 10: 287-288.). Malaria in monkeys has been reported in the remaining Atlantic Forest in southern and southeastern Brazil, where autochthonous human malaria cases were described (Deane 1992Deane LM 1992. Simian malaria in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 87 (Suppl. III): 1-20., Wanderley et al. 1994Wanderley DM, da Silva RA, de Andrade JC 1994. Epidemiological aspects of malaria in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, 1983 to 1992. Rev Saude Publica 28: 192-197., Curado et al. 1997Curado I, Duarte AMRC, Lal AA, Oliveira SG, Kloetzel JK 1997. Antibodies anti bloodstream and circumsporozoite antigens (Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae/P. brasilianum) in areas of very low malaria endemicity in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 92: 235-243., 2006Curado I, Malafronte RS, Duarte AMC, Kirchgatter K, Branquinho MS, Galati EAB 2006. Malaria epidemiology in low-endemicity areas of the Atlantic Forest in the Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo, Brazil. Acta Trop 100: 54-62., Cerutti Jr et al. 2007Cerutti Jr C, Boulos M, Coutinho AF, Hatab MC, Falqueto A, Rezende HR, Duarte AM, Collins W, Malafronte RS 2007. Epidemiologic aspects of the malaria transmission cycle in an area of very low incidence in Brazil. Malar J 6: 33., Yamasaki et al. 2011Yamasaki T, Duarte AMRC, Curado I, Summa MEL, Neves DV, Wunderlich G, Malafronte RS 2011. Detection of etiological agents of malaria in howler monkeys from Atlantic Forests, rescued in regions of São Paulo city, Brazil. J Med Primatol 40: 392-400.). In these regions, Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzii and Anophe - les (Kerteszia) bellator are the local vectors (Deane et al. 1966Deane LM, Deane MP, Ferreira Neto J 1966. Studies on transmission of simian malaria and on the natural infection of man with Plasmodium simium in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 35: 805-808., Marrelli et al. 2007Marrelli MT, Malafronte RS, Sallum MA, Natal D 2007. Kerteszia subgenus of Anopheles associated with the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest: current knowledge and future challenges. Malar J 6: 127.). In this paper, we describe the prevalence of Plasmodium infection and levels of antibodies against P. vivax antigens among wild and captive monkeys from Atlantic Forest in the South Region of Brazil [municipality of Indaial, state of Santa Catarina (SC)].

Sixty-five southern brown howler monkeys were studied, 20 wild and 45 captive monkeys from the Centre for Biological Research (Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources, registration 1/42/98/000708-90, Indaial, SC). The wild animals were captured in the Geisler Mountain in Indaial or attended to in a veterinary hospital in the municipality of Blumenau as victims of electrical shock or running over. This study was approved by the Ethical Use of Animals in Research Committee at the Regional University of Blumenau (protocol 28953-1 2011). A preliminary survey identified four out of 13 monkeys with forms suggestive of Plasmodium (Table TABLE Haematological and biochemical values from the blood sample of a captive Alouatta clamitans BL10 naturally infected by Plasmodium simium/Plasmodium vivax CBC Blood sample Reference values (95% CI)a Leukocytes (103/µL) 7.9b 8.75-11.03 Lymphocytes (103/µL) 4 3.58-4.49 Neutrophils (103/µL) 3.9b 4.93-6.88 Erythrocytes (106/µL) 3.36b 4.26-4.63 Haemoglobin (g/dL) 9.2b 10.82-11.65 Haematocrit (%) 26.9b 35.06-38.41 MCV (fL) 80b 80.73-84.45 MCH (pg/cel) 27.4c 24.77-25.68 MCHC (g/dL) 34.2c 30.02-31.28 PLT count (103/µL) 18/125b,d 198.62-267.58 Biochemical analyses Serum Reference values (95% CI)a Urea (mg/dL) 300/48.39c,d 35.03-43.70 Creatinine (UI/L) 4.6c 1.16-1.33 AST (UI/L) 197.7c 53.99-70.63 SGPT (UI/L) 248.3c 28.26-42.27 Albumin (g/dL) 2.0b 3.17-3.72 Total protein (g/dL) 7.4b 9.05-10.37 Amylase (UI/L) 243.41 - a: reference values according to de Souza Jr (2007); b: values below the reference; c: values above the reference; d: test using monkey blood collected 72 h later of the first analysis; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CBC: complete blood count; CI: confidence interval; MCHC: mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) concentration; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; PLT: platelets; SGPT: serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase. and Supplementary data, Figure Diagnosis of malaria infection in Alouatta clamitans (BL10). A: blood smear panoptic-stained showing suggestive forms of Plasmodium gametocyte; B: nested-polymerase chain reaction results showing 18SSU RNA amplification according to Snounou et al. (1993); BL10: infected monkey; C-: negative control (without DNA); M: marker; Pv: positive control of patient infected with Plasmodium vivax. ). Molecular diagnosis using nested-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Snounou et al. 1993Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jar W, Thaithong S, Brown KN 1993. Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of the high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol 58: 283-292.) and real-time PCR (Mangold et al. 2005Mangold KA, Manson RU, Koay ES, Stephens L, Regner M, Thomson Jr RB, Peterson LR, Kaul KL 2005. Real-time PCR for detection and identification of Plasmodium spp. J Clin Microbiol 43: 2435-2440.) for the identification of the human species of plasmodia confirmed P. vivax/P. simium infection (Fig. 1) in two (4.4%) captive and seven (35%) wild monkeys (average 13.8%) (Table). The prevalence of Plasmodium in wild A. clamitans monkeys is much higher than previously reported for SP (5.6%) (Duarte et al. 2008Duarte AM, Malafronte RS, Cerutti Jr C, Curado I, de Paiva BR, Maeda AY, Yamasaki T, Summa ME, Neves DV, de Oliveira SG, Gomes AC 2008. Natural Plasmodium infections in Brazilian wild monkeys: reservoirs for human infections? Acta Trop 107: 179-185.). In SC, infection of A. clamitans caused by P. brasilianum and P. simium was reported nearly the same rates, approximately 10% (Deane et al. 1992Deane LM, Deane MP, Ferreira Neto J 1966. Studies on transmission of simian malaria and on the natural infection of man with Plasmodium simium in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 35: 805-808.). Here, we identified a greater prevalence rate of P. simium infection; however, no infection by P. brasilianum was identified among the surveyed monkeys. The identification of P. malariae infection by PCR might be hampered by polymorphisms in the SSU rRNA gene, leading to an underestimation of its prevalence (Liu et al. 1998Liu Q, Zhu S, Mizuno S, Kimura M, Liu P, Isomura S, Wang X, Kawamoto F 1998. Sequence variation in the small-subunit rRNA gene of Plasmodium malariae and prevalence of isolates with the variant sequence in Sichuan, China. J Clin Microbiol 36: 3378-3381.).

: real-time results (Mangold et al. 2005Mangold KA, Manson RU, Koay ES, Stephens L, Regner M, Thomson Jr RB, Peterson LR, Kaul KL 2005. Real-time PCR for detection and identification of Plasmodium spp. J Clin Microbiol 43: 2435-2440.) showing dissociation curve of human Plasmodium species positive controls and samples of four P. simium infected monkeys: wild (BL4 and BL5) and captive (BL10) (symptomatic) and BL28.

Prevalence of Plasmodium vivax/Plasmodium simium infection in captive and wild Alouatta clamitans from the municipality of Indaial, state of Santa Catarina

One out of 45 captive monkeys (named BL10) with positive microscopy showed symptoms suggestive of malaria, including inappetence, weakness, apathy, intermittent muscle tremors, dry and pale mucous membranes, mild dehydration and loss of muscle mass and body weight. This animal showed several haematological and biochemical alterations, mainly severe thrombocytopenia, anaemia and serum uraemia (Table TABLE Haematological and biochemical values from the blood sample of a captive Alouatta clamitans BL10 naturally infected by Plasmodium simium/Plasmodium vivax CBC Blood sample Reference values (95% CI)a Leukocytes (103/µL) 7.9b 8.75-11.03 Lymphocytes (103/µL) 4 3.58-4.49 Neutrophils (103/µL) 3.9b 4.93-6.88 Erythrocytes (106/µL) 3.36b 4.26-4.63 Haemoglobin (g/dL) 9.2b 10.82-11.65 Haematocrit (%) 26.9b 35.06-38.41 MCV (fL) 80b 80.73-84.45 MCH (pg/cel) 27.4c 24.77-25.68 MCHC (g/dL) 34.2c 30.02-31.28 PLT count (103/µL) 18/125b,d 198.62-267.58 Biochemical analyses Serum Reference values (95% CI)a Urea (mg/dL) 300/48.39c,d 35.03-43.70 Creatinine (UI/L) 4.6c 1.16-1.33 AST (UI/L) 197.7c 53.99-70.63 SGPT (UI/L) 248.3c 28.26-42.27 Albumin (g/dL) 2.0b 3.17-3.72 Total protein (g/dL) 7.4b 9.05-10.37 Amylase (UI/L) 243.41 - a: reference values according to de Souza Jr (2007); b: values below the reference; c: values above the reference; d: test using monkey blood collected 72 h later of the first analysis; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CBC: complete blood count; CI: confidence interval; MCHC: mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) concentration; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; PLT: platelets; SGPT: serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase. , Supplementary data). P. vivax/P. simium infection was confirmed by PCR-based techniques (Figure Diagnosis of malaria infection in Alouatta clamitans (BL10). A: blood smear panoptic-stained showing suggestive forms of Plasmodium gametocyte; B: nested-polymerase chain reaction results showing 18SSU RNA amplification according to Snounou et al. (1993); BL10: infected monkey; C-: negative control (without DNA); M: marker; Pv: positive control of patient infected with Plasmodium vivax. , Supplementary data). This animal was treated with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (23 mg/kg).

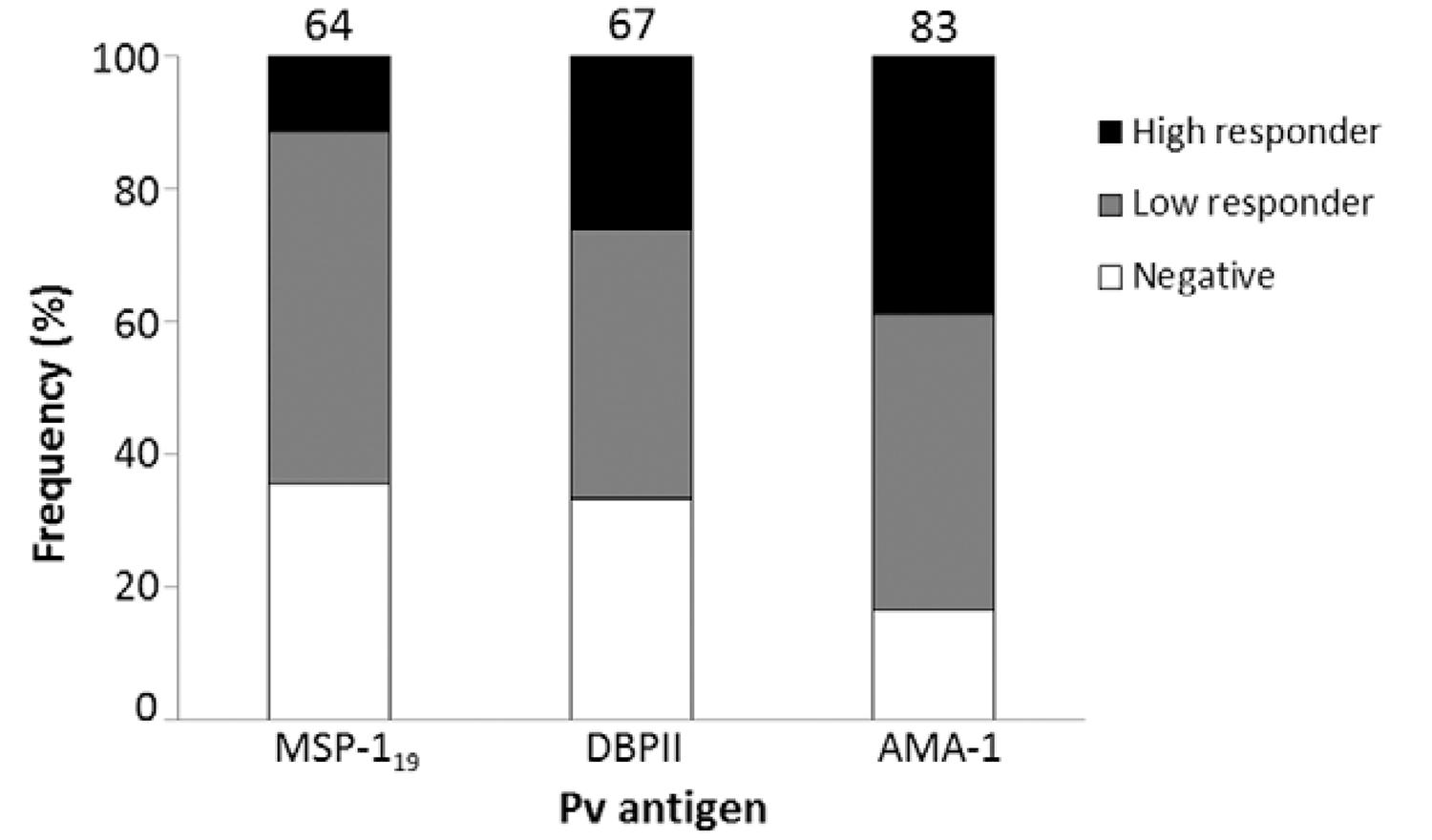

Because chronic asymptomatic infections, with very low levels of parasitaemia, could be present in that area, we evaluated the prevalence of ELISA-detected antibodies against P. vivax antigens (PvDBPII, PvMSP-119 and PvAMA-1; the last two antigens were kindly provided by Dr Irene Soares from São Paulo University), according to Kano et al. (2010)Kano FS, Sanchez BA, Sousa TN, Tang ML, Saliba J, Oliveira FM, Nogueira PA, Gonçalves AQ, Fontes CJ, Soares IS, Brito CF, Rocha RS, Carvalho LH 2012. Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein: baseline antibody responses and parasite polymorphisms in a well-consolidated settlement of the Amazon Region. Trop Med Int Health 17: 989-1000., using anti-IgG of Macaca mulatta as secondary antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). The results confirmed high frequencies (ranging from 64-83% for each antigen and 87% for any antigen) of P. vivax-specific antibodies (Fig. 2), albeit at low levels, which confirmed chronic simian malaria infection in this area. Similar serological results were previously described in monkeys from SP by using an ELISA with P. vivax circumsporozoite peptides (Duarte et al. 2006Duarte AM, Porto MA, Curado I, Malafronte RS, Hoffmann EH, de Oliveira SG, da Silva AM, Kloetzel JK, Gomes AC 2006. Widespread occurrence of antibodies against circumsporozoite protein and against blood forms of Plasmodium vivax, P. falciparum and P. malariae in Brazilian wild monkeys. J Med Primatol 35: 87-96.).

: frequencies of IgG antibodies among Alouatta clamitans monkeys against Plasmodium vivax antigens: 19 kDa fragment of merozoite surface antigen 1 (MSP-119), domain II of Duffy binding protein (DBPII) and apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA-1). Negative: optical density (OD)492nm < cut off; low responders: cut off < OD492nm < 0.3; high responders: OD492nm > 0.3. Numbers above the plots indicated the percentage of positive monkeys (low and high responders). Cut-off: mean OD492nm of negative controls (monkeys non-exposed to infection) + 3 standard deviations.

Taken together, our results confirmed high prevalence of simian malaria in southern brown howler monkeys from the Atlantic Forest, suggesting that malaria has the potential to be a public health problem due to the close contact between humans and monkeys in these regions. These findings highlight the possibility of malaria as a zoonosis in specific geographic regions, which might impact the epidemiology of this disease.

REFERENCES

- Cerutti Jr C, Boulos M, Coutinho AF, Hatab MC, Falqueto A, Rezende HR, Duarte AM, Collins W, Malafronte RS 2007. Epidemiologic aspects of the malaria transmission cycle in an area of very low incidence in Brazil. Malar J 6: 33.

- Coatney GR 1971. The simian malarias: zoonoses, anthroponoses or both? Am J Trop Med Hyg 20: 795-803.

- Cochrane AH, Barnwell JW, Collins WE, Nussenzweig RS 1985. Monoclonal antibodies produced against sporozoites of the human parasite Plasmodium malariae abolish infectivity of sporozoites of the simian parasite Plasmodium brasilianum Infect Immun 50: 58-61.

- Collins WE, Contacos PG, Guinn EG 1969. Observations on the sporogonic cycle and transmission of Plasmodium simium Da Fonseca. J Parasitol 55: 814-816.

- Curado I, Duarte AMRC, Lal AA, Oliveira SG, Kloetzel JK 1997. Antibodies anti bloodstream and circumsporozoite antigens (Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae/P. brasilianum) in areas of very low malaria endemicity in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 92: 235-243.

- Curado I, Malafronte RS, Duarte AMC, Kirchgatter K, Branquinho MS, Galati EAB 2006. Malaria epidemiology in low-endemicity areas of the Atlantic Forest in the Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo, Brazil. Acta Trop 100: 54-62.

- da Fonseca F 1951. Plasmódio de primata do Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 49: 543-551.

- de Souza Jr JC 2007. Perfil sanitário de bugios ruivos, Alouatta guariba clamitans (Cabrera, 1940) (Primates: Atelidae): um estudo com animais recepcionados e mantidos em perímetro urbano no município de Indaial, Santa Catarina - Brasil, MsD Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 218 pp.

- Deane LM 1988. Malaria studies and control in Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 38: 223-230.

- Deane LM 1992. Simian malaria in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 87 (Suppl. III): 1-20.

- Deane LM, Deane MP, Ferreira Neto J 1966. Studies on transmission of simian malaria and on the natural infection of man with Plasmodium simium in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 35: 805-808.

- Deane M, Neto JF, Sitônio JG 1968. New host of natural Plasmodium simium and Plasmodium brasilianum: mono, Brachyteles arachnoides J Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 10: 287-288.

- Duarte AM, Malafronte RS, Cerutti Jr C, Curado I, de Paiva BR, Maeda AY, Yamasaki T, Summa ME, Neves DV, de Oliveira SG, Gomes AC 2008. Natural Plasmodium infections in Brazilian wild monkeys: reservoirs for human infections? Acta Trop 107: 179-185.

- Duarte AM, Porto MA, Curado I, Malafronte RS, Hoffmann EH, de Oliveira SG, da Silva AM, Kloetzel JK, Gomes AC 2006. Widespread occurrence of antibodies against circumsporozoite protein and against blood forms of Plasmodium vivax, P. falciparum and P. malariae in Brazilian wild monkeys. J Med Primatol 35: 87-96.

- Kano FS, Sanchez BA, Sousa TN, Tang ML, Saliba J, Oliveira FM, Nogueira PA, Gonçalves AQ, Fontes CJ, Soares IS, Brito CF, Rocha RS, Carvalho LH 2012. Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein: baseline antibody responses and parasite polymorphisms in a well-consolidated settlement of the Amazon Region. Trop Med Int Health 17: 989-1000.

- Leclerc MC, Hugot JP, Durand P, Renaud F 2004. Evolutionary relationships between 15 Plasmodium species from new and old world primates (including humans): an 18S rDNA cladistic analysis. Parasitology 129: 677-684.

- Liu Q, Zhu S, Mizuno S, Kimura M, Liu P, Isomura S, Wang X, Kawamoto F 1998. Sequence variation in the small-subunit rRNA gene of Plasmodium malariae and prevalence of isolates with the variant sequence in Sichuan, China. J Clin Microbiol 36: 3378-3381.

- Mangold KA, Manson RU, Koay ES, Stephens L, Regner M, Thomson Jr RB, Peterson LR, Kaul KL 2005. Real-time PCR for detection and identification of Plasmodium spp. J Clin Microbiol 43: 2435-2440.

- Marrelli MT, Malafronte RS, Sallum MA, Natal D 2007. Kerteszia subgenus of Anopheles associated with the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest: current knowledge and future challenges. Malar J 6: 127.

- Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jar W, Thaithong S, Brown KN 1993. Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of the high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol 58: 283-292.

- Wanderley DM, da Silva RA, de Andrade JC 1994. Epidemiological aspects of malaria in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, 1983 to 1992. Rev Saude Publica 28: 192-197.

- Yamasaki T, Duarte AMRC, Curado I, Summa MEL, Neves DV, Wunderlich G, Malafronte RS 2011. Detection of etiological agents of malaria in howler monkeys from Atlantic Forests, rescued in regions of São Paulo city, Brazil. J Med Primatol 40: 392-400.

TABLE

Haematological and biochemical values from the blood sample of a captive Alouatta clamitans BL10 naturally infected by Plasmodium simium/Plasmodium vivax| CBC | Blood sample | Reference values (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes (103/µL) | 7.9b | 8.75-11.03 |

| Lymphocytes (103/µL) | 4 | 3.58-4.49 |

| Neutrophils (103/µL) | 3.9b | 4.93-6.88 |

| Erythrocytes (106/µL) | 3.36b | 4.26-4.63 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.2b | 10.82-11.65 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 26.9b | 35.06-38.41 |

| MCV (fL) | 80b | 80.73-84.45 |

| MCH (pg/cel) | 27.4c | 24.77-25.68 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 34.2c | 30.02-31.28 |

| PLT count (103/µL) | 18/125b,d | 198.62-267.58 |

| Biochemical analyses | Serum | Reference values (95% CI)a |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 300/48.39c,d | 35.03-43.70 |

| Creatinine (UI/L) | 4.6c | 1.16-1.33 |

| AST (UI/L) | 197.7c | 53.99-70.63 |

| SGPT (UI/L) | 248.3c | 28.26-42.27 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.0b | 3.17-3.72 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.4b | 9.05-10.37 |

| Amylase (UI/L) | 243.41 | - |

a: reference values according to de Souza Jr (2007); b: values below the reference; c: values above the reference; d: test using monkey blood collected 72 h later of the first analysis; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CBC: complete blood count; CI: confidence interval; MCHC: mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) concentration; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; PLT: platelets; SGPT: serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase.

Diagnosis of malaria infection in Alouatta clamitans (BL10). A: blood smear panoptic-stained showing suggestive forms of Plasmodium gametocyte; B: nested-polymerase chain reaction results showing 18SSU RNA amplification according to Snounou et al. (1993)Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jar W, Thaithong S, Brown KN 1993. Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of the high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol 58: 283-292.; BL10: infected monkey; C-: negative control (without DNA); M: marker; Pv: positive control of patient infected with Plasmodium vivax.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

05 Aug 2014 -

Date of issue

Aug 2014

History

-

Received

13 Dec 2013 -

Accepted

24 May 2014