Abstract

Under the background of climate change, the increase of atmospheric CO2 and drought frequency have been considered as significant influencers on the soil microbial communities and the yield and quality of crop. In this study, impacts of increased ambient CO2 and drought on soil microbial structure and functional diversity of a Stagnic Anthrosol were investigated in phytotron growth chambers, by testing two representative CO2 levels, three soil moisture levels, and two soil cover types (with or without Glycine max). The 16S rDNA and 18S rDNA fragments were amplified to analyze the functional diversity of fungi and bacteria. Results showed that rhizosphere microbial biomass and community structure were significantly affected by drought, but effects differed between fungi and bacteria. Drought adaptation of fungi was found to be easier than that of bacteria. The diversity of fungi was less affected by drought than that of bacteria, evidenced by their higher diversity. Severe drought reduced soil microbial functional diversity and restrained the metabolic activity. Elevated CO2 alone, in the absence of crops (bare soil), did not enhance the metabolic activity of soil microorganisms. Generally, due to the co-functioning of plant and soil microorganisms in water and nutrient use, plants have major impacts on the soil microbial community, leading to atmospheric CO2 enrichment, but cannot significantly reduce the impacts of drought on soil microorganisms.

enzyme activities; microbial functional diversity; fungi and bacteria; relative abundance

INTRODUCTION

Low soil water contents decrease the microbial abundance (Bloem et al., 1992Bloem J, Ruiter PC, Koopman GJ, Lebbink G, Brussaard L. Microbial numbers and activity in dried and rewetted arable soil under integrated and conventional management. Soil Biol Biochem. 1992;24:655-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(92)90044-x

https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(92)900...

), an effect known to be induced by changes in soil nutrient and water use efficiency (Djekoun and Planchon, 1991Djekoun A, Planchon C. Water status effect on dinitrogen fixation and photosynthesis in soybean. Agron J. 1991;83:316-22. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1991.00021962008300020011x

https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1991.00021...

; Yi et al., 2007Yi Z, Fu S, Yi W, Zhou G, Mo J, Zhang D, Ding M, Wang X, Zhou L. Partitioning soil respiration of subtropical forests with different successional stages in south China. Forest Ecol Manag. 2007;243:178-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.02.022

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.02...

). On the other hand, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has been increasing due to emissions from human activities during the last century (IPCC, 2007Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - IPCC. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.). It was supposed that increased ambient CO2 could raise the C/N ratio, altering the soil nutrient components (Hu et al., 1999Hu S, Firestone MK, Chapin III FS. Soil microbial feedbacks to atmospheric CO2 enrichment. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14:433-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01682-1

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01...

; Kassem et al., 2008Kassem II, Joshi P, Sigler V, Heckathorn S, Wang Q. Effect of elevated CO2 and drought on soil microbial communities associated with Andropogon gerardii. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:1406-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00752.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008...

; Wang et al., 2008Wang D, Heckathorn SA, Barua D, Joshi P, Hamilton EW, LaCroix JJ. Effects of elevated CO2 on the tolerance of photosynthesis to acute heat stress in C3, C4, and CAM species. Am J Bot. 2008;95:165-76. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.95.2.165

https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.95.2.165...

), consequently affecting the abundance and diversity of the microbial community and influencing soil microbial functions.

However, there is a controversy about the impacts of elevated CO2 concentration on the soil microbial system (Bazzaz, 1990Bazzaz FA. The response of natural ecosystems to the rising global CO2 levels. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1990;21:167-96. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.001123

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.21.11...

). The high heterogeneity of soil physical and chemical properties, high variability of soil microbial community, and the highly complex plant-microbial interaction are the reason for different results of studies assessing the influence of elevated CO2 (Rees et al., 2005Rees RM, Bingham IJ, Baddeley JA, Watson CA. The role of plants and land management in sequestering soil carbon in temperate arable and grassland ecosystems. Geoderma. 2005;128:130-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.12.020

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004....

). A two-year open-air experiment of carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE) indicated that elevated CO2 concentrations had insignificant effects on the increase of soil microbial biomass carbon and microbial diversity (Schortemeyer et al., 1996Schortemeyer M, Hartwig UA, Hendrey GR, Sadowsky MJ. Microbial community changes in the rhizospheres of white clover and perennial ryegrass exposed to free air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE). Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:1717-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(96)00243-x

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(96)00...

; Rønn et al., 2002Rønn R, Gavito M, Larsen J, Jakobsen I, Frederiksen H, Christensen S. Response of free-living soil protozoa and microorganisms to elevated atmospheric CO2 and presence of mycorrhiza. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:923-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(02)00024-x

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(02)00...

; Dam et al., 2017Dam M, Bergmark L, Vestergård M. Elevated CO2 increases fungal-based micro-foodwebs in soils of contrasting plant species. Plant Soil. 2017;415:549-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3191-3

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3191-...

). However, in a previous 8-year study, highly elevated CO2 significantly changed the soil microbial community structure (Williams et al., 2000Williams MA, Rice CW, Owensby CE. Carbon dynamics and microbial activity in tallgrass prairie exposed to elevated CO2 for 8 years. Plant Soil. 2000;227:127-37. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026590001307

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026590001307...

). It was concluded that elevated CO2 induces loop modifications in the plant-microbe system, although the significance of these effects can have different levels, according to the CO2 enhancement level and exposure time (Wong, 1990Wong S-C. Elevated atmospheric partial pressure of CO2 and plant growth: II. Non-structural carbohydrate content in cotton plants and its effect on growth parameters. Photosynth Res. 1990;23:171-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00035008

https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00035008...

).

Although the individual effects of elevated CO2 or drought on the soil microbe system have been documented in many articles, few studies have addressed the combined effects of elevated CO2 and drought on soil microbial community structure and functional diversity in cultivated soil (Yonemura et al., 1998Yonemura S, Yajima M, Sakai H, Morokuma M. Estimate of rice yield of Japan under the conditions with elevated CO2 and increased temperature by using third mesh climate data. Agric Meteorol. 1998;54:235-45. https://doi.org/10.2480/agrmet.54.235

https://doi.org/10.2480/agrmet.54.235...

). In particular, on the background of climate change, the occurrence frequency of drought tends to increase, significantly affecting the microbial functions of agroecosystem. Thus, a further discussion is necessary to determine their influences and mutual effects.

We hypothesized that: 1) elevated CO2 concentration insignificantly enhance the metabolic activity in the cultivated soil; 2) severe drought decreases microbial functional diversity and restrain the metabolic activity of soil microbes. In this sense, a greenhouse experiment was conducted to understand the short-term interactive effects of elevated CO2 and drought on the changes of soil microbial community structure and functional diversity, in soil under Glycine max (soybean).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design

Soil samples of a Stagnic Anthrosol were collected in March 2013 from the surface layer (0.00-0.15 m) in the Yangtze River Delta, Shanghai. After removing organic debris and rocks, soil samples were sieved (<10 mm), homogenized, and blended into a single composite sample. The samples were filled in pots (0.25 m height × 0.25 m diameter) and divided into 12 treatments, with three replications. A factorial design was used (Table 1), with two representative CO2 levels, three soil moisture levels, and two soil cover types [with or without Glycine max (Yu 19)]. Twelve beans per pot were inserted at 0.05 m depth in the soil. The pots were incubated in a chamber (PRX-2000C-CO2, China) in random positions. Before germination, the chamber temperature was maintained at 25 °C, light intensity at 600 μmol m-2 s-1, and relative air humidity at 60 %. Daily watering was performed at 8:00 a.m. No fertilizer was applied during incubation, and CO2 was monitored with a build-in infrared CO2 meter (TES 1370, Taiwan).

Functional and genetic diversity of the soil microbial community

After 60-day incubation, genomic DNA of the soil samples was extracted with the DNA isolation kit (PowerSoil, USA). The16S rDNA and 18S rDNA fragments were amplified to analyze the functional diversity of the soil microbial community. The F338-GC and R518 were used as bacterium-specific primers (Muyzer et al., 1993Muyzer G, Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microb. 1993;59:695-700.). For fungi, 18S rDNA fragments were amplified with the primer pair of FR1-GC and FF390, as described by Vainio and Hantula (2000)Vainio EJ, Hantula J. Direct analysis of wood-inhabiting fungi using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of amplified ribosomal DNA. Mycol Res. 2000;104:927-36. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0953756200002471

https://doi.org/10.1017/s095375620000247...

. The reaction mixture contained 4 μL dNTP, 3 μL MgCl2, 1 μL of each primer, 0.25 μL Taq polymerase, and 2 μL DNA template.

A touchdown PCR was programmed, according to the methodology described by Zhang et al. (2012)Zhang W, Zhang M, An S, Lin K, Li H, Cui C, Fu R, Zhu J. The combined effect of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) and copper (Cu) on soil enzyme activities and microbial community structure. Environ Toxicol Phar. 2012;34:358-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2012.05.009

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2012.05.0...

. Firstly, 25 μL PCR products were loaded on an 8 % polyacrylamide gel. The denaturing gradient ranged from 40 to 80 %. Electrophoresis was carried out with the Dcode system (Bio-Rad, USA), performed for 12 h at 80 V and 60 °C. Thereafter, the gel was stained with ethylene dibromide 0.5 μg mL-1 for 30 min and visualized under UV with BIO-RAD (BIO-Rad XR, USA).

A bacterial identification system (BIOLOG MicroPlate, USA) assessed the functional diversity of microorganisms based on the patterns of 31 single carbon sources. At the end of incubation, 10 g of soil sample was added to a 50 mL sterilized Erlenmeyer flask with 0.5 mol L-1 phosphate buffer (pH =7.0). The mixture was sealed and shaken for 10 min in the dark. A microplate was preheated to 25 °C. Then, 150 μL of diluted supernatant (1:1,000) was added to each well of the plate and incubated at 25 °C. The UV absorption (590 nm) of each well was determined after 12, 24, 48, 72, 129, and 144 h of incubation. The data were corrected based on the initial readings of the control well containing only water.

Statistics

The data are expressed as the mean values of three replicates per treatment. Two-way ANOVA measurement was used to identify significant differences among the treatments at α = 0.05. Statistical procedures were carried out with Software IBM SPSS Statistics (version 11.0). Shannon-Wiener (H’) and Simpson (D) indices were calculated to estimate the microbial diversity. Pielou (E) and McIntosh (DMc) indices were used to determine the microbial evenness. Cluster analysis (CA) was conducted to detect similarities of PCR-DGGE banding patterns among treatments with Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad). Microbial carbon source utilization was analyzed with Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to identify latent relationships among the different treatments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Response of microbial relative abundance and diversity

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis patterns showed significant differences among treatments (p<0.05) in the number of bands and density of soil bacteria (Figure 1a). In general, drought significantly affected relative abundance and diversity of soil bacteria. In the crop treatments (PAW, PAM, PAS, PCW, PCM, and PCS), the number of bands and signal density were higher than in the uncultivated treatments, indicating higher bacterial diversity and relative abundance. For instance, bands (1 to 4) in treatment 7 and 12 were much denser than in the other treatments. The main reason for the increase in bacterial diversity in the crop treatments is that dissolved organic carbon (DOC) released by soybean can be used as carbon source for the growth and metabolism of these microorganisms (Wang et al., 2017)Wang J, Song X, Wang Y, Bai J, Li M, Dong G, Lin F, Lv Y, Yan D. Bioenergy generation and rhizodegradation as affected by microbial community distribution in a coupled constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell system associated with three macrophytes. Sci Total Environ. 2017;607-608:53-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.243

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017...

. It has been reported that the below-ground biomass of Canna indica was 4.30 ± 0.83 g per plant, for roots with a diameter of less than 1 mm (Lai et al., 2011)Lai W-L, Wang S-Q, Peng C-L, Chen Z-H. Root features related to plant growth and nutrient removal of 35 wetland plants. Water Res. 2011;45:3941-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.05.002

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.05...

. Moreover, the oxygen release and transfer rates of plants can also contribute to the growth of aerobic microbes around the roots of macrophytes. In the literature, similar findings also indicated that the biodiversity was increased by rhizosphere bacteria over that of uncultivated areas (Wang et al., 2017)Wang J, Song X, Wang Y, Bai J, Li M, Dong G, Lin F, Lv Y, Yan D. Bioenergy generation and rhizodegradation as affected by microbial community distribution in a coupled constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell system associated with three macrophytes. Sci Total Environ. 2017;607-608:53-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.243

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017...

. In crop treatments, bacterial abundance and diversity were increased at elevated CO2 (p>0.05). However, in uncultivated treatments, drought inhibited soil bacteria significantly (p<0.05). Although the soil bacteria community structure did not change with drought, the relative abundance declined. The effect of elevated CO2 concentration on relative abundance or density was not significant in any treatment (p>0.05).

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analyses of 16S rDNA fragments for bacteria (a) and 18S rDNA fragments for fungi (b) in different treatments. 1: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; 2: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; 3: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; 4: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; 5: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; 6: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; 7: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; 8: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; 9: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; 10: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; 11: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; and 12: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition.

The fungi DGGE pattern was presented in figure 1b. The fungal community structure differed significantly among treatments (p<0.05). The number and density of fungi bands were lower than those of bacteria in the same treatment (p<0.05). This indicated a lower fungal than bacterial abundance and diversity, although drought had limited impacts on fungal abundance and diversity. The highest similarity was found in drought treatments. The relative abundance and diversity of fungi in bare soil were higher than in the crop treatments. This difference might be caused by root exudates that inhibited fugal development. In the crop treatments, denser bands (b and c) showed that an elevated CO2 concentration increased the fungal abundance and diversity (p>0.05).

Diversity and evenness indices of soil bacteria and fungi calculated from DGGE results indicated that drought reduced bacterial abundance (Table 2). Relative abundance and diversity of bacteria decreased with soil moisture, indicating that drought significantly inhibited bacterial growth. However, fungal abundance and diversity increased when soil moisture dropped. The potential of autochthonous Arbuscular Mycorrhizal fungal species and particularly their mixture with Bacillus thuringiensis of protecting plants against drought and helping plants to thrive in semiarid ecosystems was described by Armada et al. (2016)Armada E, Probanza A, Roldán A, Azcón R. Native plant growth promoting bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis and mixed or individual mycorrhizal species improved drought tolerance and oxidative metabolism in Lavandula dentata plants. J Plant Physiol. 2016;192:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.11.007

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.11....

. Thus, we concluded that the increase in fungal species under drought might be beneficial for the growth of soybean plants. Apart from extreme drought conditions, elevated CO2 concentration would increase fungal abundance and diversity during water stress. Drought was also observed to stimulate fungal development in bare soil. It is known that the adaption of fungi to drought and low matric potential is easier than that of bacteria (Kohler et al., 2010Kohler J, Knapp BA, Waldhuber S, Caravaca F, Roldán A, Insam H. Effects of elevated CO2, water stress, and inoculation with Glomus intraradices or Psedomonas mendocina on lettuce dry mater and rhizosphere microbial and functional diversity under growth chamber conditions. J Soils Sediments. 2010;10:1585-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-010-0259-6

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-010-0259-...

). A reason could be that partial microbial death provided nutrients for fungi during drought adaption. However, fungal abundance did not increase in response to the different CO2 concentrations, due to the nitrogen restriction (Guenet et al., 2012Guenet B, Lenhart K, Leloup J, Giusti-Miller S, Pouteau V, Mora P, Nunan N, Abbadie L. The impact of long-term CO2 enrichment and moisture levels on soil microbial community structure and enzyme activities. Geoderma. 2012;170:331-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.12.002

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2011....

).

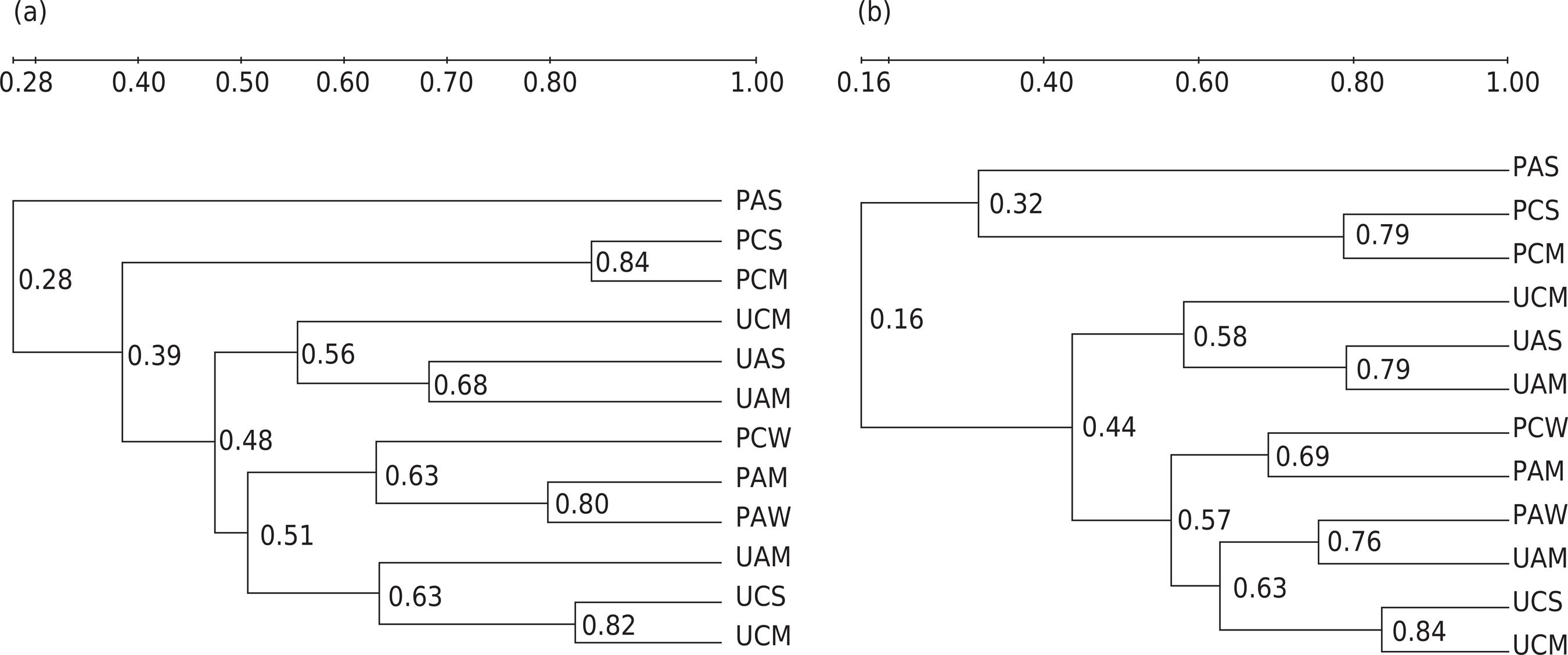

According to the dendrogram of microbial clustering analysis (Figure 2), apart from soil moisture, soil cover was a main factor affecting the microbial community structure. Previous studies indicated that higher CO2 concentrations (20 %) could benefit the development of fungal abundance when soil water moisture met the demand for plant growth (Xue et al., 2017Xue S, Yang X, Liu G, Gai L, Zhang C, Ritsema CJ, Geissen V. Effects of elevated CO2 and drought on the microbial biomass and enzymatic activities in the rhizospheres of two grass species in Chinese loess soil. Geoderma. 2017;286:25-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.10.025

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016....

). Soil microbes were indirectly stimulated by the accumulation of root exudation and potential allelochemicals at elevated CO2 concentration (Lin et al., 1999Lin G, Ehleringer JR, Rygiewicz PT, Johnson MG, Tingey DT. Elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on different components of soil CO2 efflux in Douglas-fir terracosms. Glob Change Biol. 1999;5:157-68. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00211.x

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999...

). In addition, plant growth can contribute to the decrease of soil nitrogen by root uptake. A reduction in soil nitrogen use may benefit the growth and metabolism of microorganisms (Rakshit et al., 2012Rakshit R, Patra AK, Pal D, Kumar M, Singh R. Effect of elevated CO2 and temperature on nitrogen dynamics and microbial activity during wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) growth on a subtropical Inceptisol in India. J Agron Crop Sci. 2012;198:452-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037x.2012.00516.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037x.2012...

). This stimulation was not significant when the soil CO2 concentration was much higher than in the atmosphere. In bare soil, elevated CO2 concentration affected soil microbes by changing the oxygen and nutrient supply by enlarging the particle size of soil aggregates (Niklaus et al., 2003Niklaus PA, Alphei J, Ebersberger D, Kampichler C, Kandeler E, Tscherko D. Six years of in situ CO2 enrichment evoke changes in soil structure and soil biota of nutrient-poor grassland. Glob Change Biol. 2003;9:585-600. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00614.x

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003...

), but such influence depended on the sufficiency of nitrogen restriction or soil type (Bruce et al., 2000Bruce KD, Jones TH, Bezemer TM, Thompson LJ, Ritchie DA. The effect of elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide levels on soil bacteria communities. Glob Change Biol. 2000;6:427-34. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00320.x

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000...

). Thus, we assumed that plants minimized the bacteria-inhibiting drought impacts.

Dendrogram constructed with the complete similarity linkage between bacteria-specific (a) and fungi-specific (b) PCR-DGGE patterns for different treatments. UAW: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; UAM: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; UAS: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; PAW: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; PAM: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; PAS: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; UCW: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; UCM: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; UCS: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; PCW: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; PCM: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; PCS: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition.

Response of microbial functional diversity

Based on the utilization patterns of 31 single carbon sources, microbial functional diversity was assessed by testing the capability of the microbial community to adapt their metabolism to various abiotic conditions. The variation in average well color development (AWCD) over time (Figure 3) followed an asymptotic sigmoidal curve, but differed significantly among treatments. Soil microbial carbon source utilization was insignificant in 24 h. However, the increase was rapidly intensified in the following 12 h. After 108 h, the upward trend was slowed down. Compared to those in bare soil, microorganisms showed higher metabolic activity in cultivated soil and developed quickly for environmental adaption (p<0.05). Drought affected the microbial metabolism greatly (p<0.01), regardless of the plant cover. Under drought, the final AWCD ranged from 0.4 to 2.3. Elevated CO2 concentration affected the metabolic activity positively. Similar reports also demonstrated that the microbial communities collected from the rhizosphere of Danthonia richardsonii grown for four years at twice-ambient CO2 had a significantly higher carbon source utilization than the communities collected from plants grown at ambient CO2 (Grayston et al., 1998)Grayston SJ, Campbell CD, Lutze JL, Gifford RM. Impact of elevated CO2 on the metabolic diversity of microbial communities in N-limited grass swards. Plant Soil. 1998;203:289-300. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004315012337

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004315012337...

.

Average well color development (AWCD) of the BIOLOG EcoPlate for different treatments. UAW: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; UAM: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; UAS: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; PAW: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; PAM: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; PAS: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; UCW: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; UCM: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; UCS: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; PCW: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; PCM: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; PCS: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition.

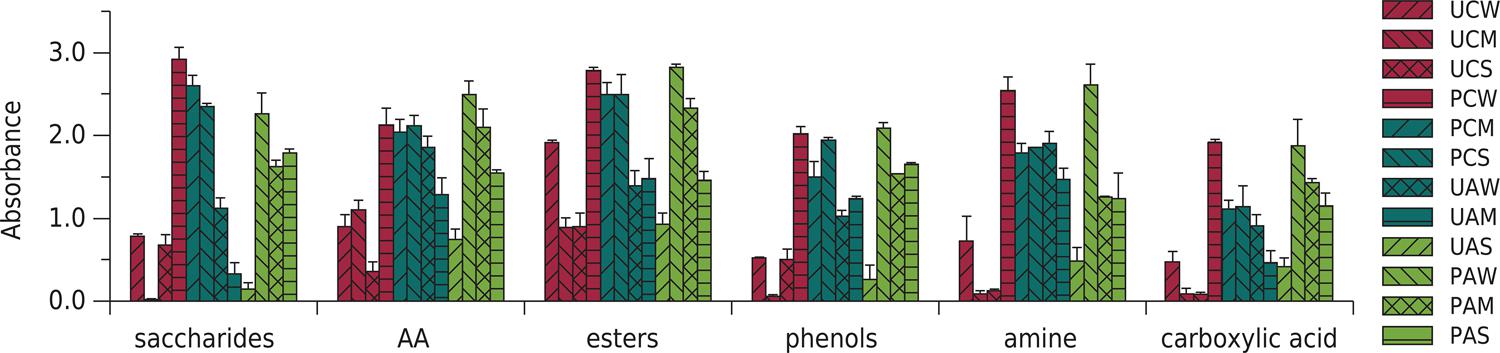

To investigate the characteristics of carbon source utilization, 31 single carbon sources were categorized in six classes: saccharides, amino acids (AA), esters, phenols, amines, and carboxylic acids (CA). The final carbon source utilization (after 96 h) differed clearly among treatments (Figure 4). Major available carbon sources included sacchrides, AA, amines, and esters. The results corresponded to the utilization of saccharides, esters, and amines in crop and elevated CO2 treatments. In bare soil, bioavailable carbon sources were changed from AA and amines to esters. The CO2 and drought had interactive effects on the higher saccharide and phenol utilization in bare soil (p<0.05). However, the interactive effects were insignificant in cultivated soil treatments (p>0.05).

Carbon utilization profile of soil microbes on BIOLOG EcoPlate for different treatments. The bars above the columns indicate standard deviation. UCW: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; UCM: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; UCS: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; PCW: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; PCM: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; PCS: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; UAW: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; UAM: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; UAS: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; PAW: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; PAM: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; PAS: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition.

Table 3 showed the diversity index based on the BIOLOG patterns of the different treatments. In the cultivated soil treatments, the functional microbial diversity was larger than in bare soil (p<0.05). Root microbes had the highest metabolic activity and all carbon sources were used. This could be explained by DGGE analysis, which showed the highest bio-diversity and abundance for root microbes. In bare soil, elevated CO2 concentration decreased microbial functional diversity (p>0.05). Soil moisture affected microbial functional diversity significantly (p<0.05). The highest functional diversity was observed in wet soil. The effect of elevated CO2 concentration on microbial functional diversity was insignificant in the cultivated soil treatments. In the literature, protein, amino acids, and water-soluble sugar were described as the predominant constituents of the dissolved organic carbon produced by crops (Zhai et al., 2013)Zhai X, Piwpuan N, Arias CA, Headley T, Brix H. Can root exudates from emergent wetland plants fuel denitrification in subsurface flow constructed wetland systems? Ecol Eng. 2013;61P:555-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.02.014

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.0...

. The dissolved organic carbon release rate of Iris pseudacorus species was in the mean 12.2 ± 0.7 μg g-1 root dry mass per h (Zhai et al., 2013)Zhai X, Piwpuan N, Arias CA, Headley T, Brix H. Can root exudates from emergent wetland plants fuel denitrification in subsurface flow constructed wetland systems? Ecol Eng. 2013;61P:555-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.02.014

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.0...

. In addition, these compounds can be easily used as carbon resource for the growth and metabolism of microorganisms. Therefore, no significant microbial functional diversity was found among the cultivated soil treatments.

There was variance contribution of microbial carbon source utilization (Figure 5). Amine, carboxylic acid, and phenol had a significant positive correlation with PC1, whereas esters and saccharides were positively related to PC2. The PC1 could be explained by soil water content and PC2 indicated the differences in CO2 concentration. Drought inhibited the utilization of carbon sources, but the functional diversity was not changed. Due to the overlapping microbial function, microbes of similar function were probably exchanged especially in the crop treatments (Kohler et al., 2010Kohler J, Knapp BA, Waldhuber S, Caravaca F, Roldán A, Insam H. Effects of elevated CO2, water stress, and inoculation with Glomus intraradices or Psedomonas mendocina on lettuce dry mater and rhizosphere microbial and functional diversity under growth chamber conditions. J Soils Sediments. 2010;10:1585-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-010-0259-6

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-010-0259-...

). The enzyme activities of microorganisms were found to be significantly affected by elevated CO2 (Kandeler et al., 2006Kandeler E, Mosier AR, Morgan JA, Milchunas DG, King JY, Rudolph S, Tscherko D. Response of soil microbial biomass and enzyme activities to the transient elevation of carbon dioxide in a semi-arid grassland. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38:2448-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.02.021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.0...

). In the treatments with elevated CO2, microbes tended to utilize saccharides and esters when the metabolic activity was intensified. Moreover, elevated CO2 concentrations inhibited the utilization of organic nitrogen compounds (Nie et al., 2013Nie M, Pendall E, Bell C, Gasch CK, Raut S, Tamang S, Wallenstein MD. Positive climate feedbacks of soil microbial communities in a semi-arid grassland. Ecol Lett. 2013;16:234-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12034

https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12034...

). These findings suggest that elevated CO2 can promote the enzyme activities using saccharides and esters as carbon sources, but inhibit the enzyme activities by using organic nitrogen compounds as nutrients.

The PCA analysis of average well color development (AWCD) over the soil microbial carbon utilization for soybean (a) and bare (b) soil treatments. UCW: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; UCM: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; UCS: unplanted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; PCW: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and well-watered condition; PCM: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and mild drought condition; PCS: planted treatment with elevated CO2 and severe drought condition; UAW: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; UAM: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; UAS: unplanted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition; PAW: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and well-watered condition; PAM: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and mild drought condition; PAS: planted treatment with ambient CO2 and severe drought condition.

CONCLUSIONS

Soil microbial biomass and community structure were significantly affected by drought. The relative abundance and diversity of bacteria were decreased by drought, while fungi were more tolerant to mild drought. Severe drought decreased microbial functional diversity and restrained the metabolic activity of soil microbes. Elevated CO2 concentration insignificantly enhanced the metabolic activity in the cultivated soil. In bare soil, the interactive effect between CO2 and drought was insignificant. Plants have major impacts on the soil microbial community. Although the influence of elevated CO2 concentration was not significant, it could minimize the impacts of drought on soil microbes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Open Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Simulation and Regulation of Water Cycle in River Basin (China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Grant No. IWHR-SKL-201313), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities-DHU Distinguished Young Professor Program (Grant No. 15D211302), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. CUSF-DH-D-2017092 and CUSF-DH-D-2017101).

REFERENCES

- Armada E, Probanza A, Roldán A, Azcón R. Native plant growth promoting bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis and mixed or individual mycorrhizal species improved drought tolerance and oxidative metabolism in Lavandula dentata plants. J Plant Physiol. 2016;192:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.11.007

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.11.007 - Bazzaz FA. The response of natural ecosystems to the rising global CO2 levels. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1990;21:167-96. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.001123

» https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.001123 - Bloem J, Ruiter PC, Koopman GJ, Lebbink G, Brussaard L. Microbial numbers and activity in dried and rewetted arable soil under integrated and conventional management. Soil Biol Biochem. 1992;24:655-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(92)90044-x

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(92)90044-x - Bruce KD, Jones TH, Bezemer TM, Thompson LJ, Ritchie DA. The effect of elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide levels on soil bacteria communities. Glob Change Biol. 2000;6:427-34. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00320.x

» https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00320.x - Dam M, Bergmark L, Vestergård M. Elevated CO2 increases fungal-based micro-foodwebs in soils of contrasting plant species. Plant Soil. 2017;415:549-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3191-3

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3191-3 - Djekoun A, Planchon C. Water status effect on dinitrogen fixation and photosynthesis in soybean. Agron J. 1991;83:316-22. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1991.00021962008300020011x

» https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1991.00021962008300020011x - Fischer SG, Lerman LS. Separation of random fragments of DNA according to properties of their sequences. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4420-4.

- Grayston SJ, Campbell CD, Lutze JL, Gifford RM. Impact of elevated CO2 on the metabolic diversity of microbial communities in N-limited grass swards. Plant Soil. 1998;203:289-300. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004315012337

» https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004315012337 - Guenet B, Lenhart K, Leloup J, Giusti-Miller S, Pouteau V, Mora P, Nunan N, Abbadie L. The impact of long-term CO2 enrichment and moisture levels on soil microbial community structure and enzyme activities. Geoderma. 2012;170:331-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.12.002

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.12.002 - Hu S, Firestone MK, Chapin III FS. Soil microbial feedbacks to atmospheric CO2 enrichment. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14:433-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01682-1

» https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01682-1 - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - IPCC. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

- Kandeler E, Mosier AR, Morgan JA, Milchunas DG, King JY, Rudolph S, Tscherko D. Response of soil microbial biomass and enzyme activities to the transient elevation of carbon dioxide in a semi-arid grassland. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38:2448-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.02.021

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.02.021 - Kassem II, Joshi P, Sigler V, Heckathorn S, Wang Q. Effect of elevated CO2 and drought on soil microbial communities associated with Andropogon gerardii J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:1406-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00752.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00752.x - Kohler J, Knapp BA, Waldhuber S, Caravaca F, Roldán A, Insam H. Effects of elevated CO2, water stress, and inoculation with Glomus intraradices or Psedomonas mendocina on lettuce dry mater and rhizosphere microbial and functional diversity under growth chamber conditions. J Soils Sediments. 2010;10:1585-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-010-0259-6

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-010-0259-6 - Lai W-L, Wang S-Q, Peng C-L, Chen Z-H. Root features related to plant growth and nutrient removal of 35 wetland plants. Water Res. 2011;45:3941-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.05.002

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.05.002 - Lin G, Ehleringer JR, Rygiewicz PT, Johnson MG, Tingey DT. Elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on different components of soil CO2 efflux in Douglas-fir terracosms. Glob Change Biol. 1999;5:157-68. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00211.x

» https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00211.x - Muyzer G, Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microb. 1993;59:695-700.

- Nie M, Pendall E, Bell C, Gasch CK, Raut S, Tamang S, Wallenstein MD. Positive climate feedbacks of soil microbial communities in a semi-arid grassland. Ecol Lett. 2013;16:234-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12034

» https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12034 - Niklaus PA, Alphei J, Ebersberger D, Kampichler C, Kandeler E, Tscherko D. Six years of in situ CO2 enrichment evoke changes in soil structure and soil biota of nutrient-poor grassland. Glob Change Biol. 2003;9:585-600. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00614.x

» https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00614.x - Rakshit R, Patra AK, Pal D, Kumar M, Singh R. Effect of elevated CO2 and temperature on nitrogen dynamics and microbial activity during wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) growth on a subtropical Inceptisol in India. J Agron Crop Sci. 2012;198:452-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037x.2012.00516.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037x.2012.00516.x - Rees RM, Bingham IJ, Baddeley JA, Watson CA. The role of plants and land management in sequestering soil carbon in temperate arable and grassland ecosystems. Geoderma. 2005;128:130-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.12.020

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.12.020 - Rønn R, Gavito M, Larsen J, Jakobsen I, Frederiksen H, Christensen S. Response of free-living soil protozoa and microorganisms to elevated atmospheric CO2 and presence of mycorrhiza. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:923-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(02)00024-x

» https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(02)00024-x - Schortemeyer M, Hartwig UA, Hendrey GR, Sadowsky MJ. Microbial community changes in the rhizospheres of white clover and perennial ryegrass exposed to free air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE). Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:1717-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(96)00243-x

» https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(96)00243-x - Vainio EJ, Hantula J. Direct analysis of wood-inhabiting fungi using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of amplified ribosomal DNA. Mycol Res. 2000;104:927-36. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0953756200002471

» https://doi.org/10.1017/s0953756200002471 - Wang D, Heckathorn SA, Barua D, Joshi P, Hamilton EW, LaCroix JJ. Effects of elevated CO2 on the tolerance of photosynthesis to acute heat stress in C3, C4, and CAM species. Am J Bot. 2008;95:165-76. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.95.2.165

» https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.95.2.165 - Wang J, Song X, Wang Y, Bai J, Li M, Dong G, Lin F, Lv Y, Yan D. Bioenergy generation and rhizodegradation as affected by microbial community distribution in a coupled constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell system associated with three macrophytes. Sci Total Environ. 2017;607-608:53-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.243

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.243 - Williams MA, Rice CW, Owensby CE. Carbon dynamics and microbial activity in tallgrass prairie exposed to elevated CO2 for 8 years. Plant Soil. 2000;227:127-37. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026590001307

» https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026590001307 - Wong S-C. Elevated atmospheric partial pressure of CO2 and plant growth: II. Non-structural carbohydrate content in cotton plants and its effect on growth parameters. Photosynth Res. 1990;23:171-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00035008

» https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00035008 - Xue S, Yang X, Liu G, Gai L, Zhang C, Ritsema CJ, Geissen V. Effects of elevated CO2 and drought on the microbial biomass and enzymatic activities in the rhizospheres of two grass species in Chinese loess soil. Geoderma. 2017;286:25-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.10.025

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.10.025 - Yi Z, Fu S, Yi W, Zhou G, Mo J, Zhang D, Ding M, Wang X, Zhou L. Partitioning soil respiration of subtropical forests with different successional stages in south China. Forest Ecol Manag. 2007;243:178-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.02.022

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.02.022 - Yonemura S, Yajima M, Sakai H, Morokuma M. Estimate of rice yield of Japan under the conditions with elevated CO2 and increased temperature by using third mesh climate data. Agric Meteorol. 1998;54:235-45. https://doi.org/10.2480/agrmet.54.235

» https://doi.org/10.2480/agrmet.54.235 - Zhai X, Piwpuan N, Arias CA, Headley T, Brix H. Can root exudates from emergent wetland plants fuel denitrification in subsurface flow constructed wetland systems? Ecol Eng. 2013;61P:555-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.02.014

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.02.014 - Zhang W, Zhang M, An S, Lin K, Li H, Cui C, Fu R, Zhu J. The combined effect of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) and copper (Cu) on soil enzyme activities and microbial community structure. Environ Toxicol Phar. 2012;34:358-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2012.05.009

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2012.05.009

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

2017

History

-

Received

11 Nov 2016 -

Accepted

7 July 2017