ABSTRACT:

Numerous plant species worldwide including some Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) and Sida (Malvaceae) species in Brazil cause lysosomal storage disease in herbivores and are known to contain swainsonine and calystegines as the main toxic compounds. The aim of this work was to determine swainsonine and calystegines concentrations in species of Convolvulaceae from the semiarid region of Pernambuco. Seven municipalities in the Moxotó region were visited and nine species were collected and screened for the presence of swainsonine and calystegines using an HPLC-APCI-MS method. The presence and concentration of these alkaloids within the same and in different species were very variable. Seven species are newly reported here containing swainsonine and/or calystegines. Ipomoea subincana contained just swainsonine. Ipomoea megapotamica, I. rosea and Jacquemontia corymbulosa contained swainsonine and calystegines. Ipomoea sericosepala, I. brasiliana, I. nil, I. bahiensis and I. incarnata contained just calystegines. The discovery of six Ipomoea species and one Jacquemontia species containing toxic polyhydroxy alkaloids reinforces the importance of this group of poisonous plants to ruminants and horses in the semiarid region of Pernambuco. Epidemiological surveys should be conducted to investigate the occurrence of lysosomal storage disease associated to these new species.

INDEX TERMS:

Poisonous plant; swainsonine; calystegines; Convolvulaceae species; Pernambuco; alkaloids; lysosomal storage disease; plant poisoning; herbivores; toxicoses

RESUMO:

Numerosas espécies de plantas em todo o mundo, incluindo algumas espécies de Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) e Sida (Malvaceae) no Brasil, causam doença de armazenamento lisossomal em herbívoros e são conhecidas por conterem swainsonina e calisteginas como princípios tóxicos. O objetivo deste trabalho foi determinar a concentração de swainsonina e calisteginas em espécies de Convolvulaceae da região semiárida de Pernambuco. Sete municípios na região do Sertão do Moxotó foram visitados, onde foram coletadas amostras das folhas de nove espécies de Convolvulaceae para avaliação da presença de swainsonina e calisteginas utilizando-se cromatografia líquida com espectrometria de massa. A presença e concentração destes alcaloides nas folhas de plantas da mesma espécie e dentre as espécies foram muito variáveis. Seis novas espécies de Ipomoea e uma espécie de Jacquemontia contendo swainsonina e/ou calisteginas são relatadas neste estudo. Ipomoea subincana continha apenas swainsonina. Ipomoea megapotamica, I. rosea e Jacquemontia corymbulosa continham swainsonina e calisteginas. Ipomoea sericosepala, I. brasiliana, I. nil, I. bahiensis e I. incarnata continham apenas calisteginas. A descoberta de novas espécies de Ipomoea e Jacquemontia contendo alcaloides polihidroxílicos tóxicos reforçam a importância deste grupo de plantas tóxicas para ruminantes e equinos na região semiárida de Pernambuco. Pesquisas epidemiológicas devem ser realizadas para investigar a ocorrência de doença de depósito lisossomal associada a essas novas espécies.

TERMOS DE INDEXAÇÃO:

Plantas tóxicas; swainsonina; calisteginas; Convolvulaceae; Pernambuco; alcaloides; doença de depósito lisossomal; intoxicação por plantas; herbívoros; toxicoses

Introduction

Swainsonine-containing plants comprises a group of several toxic weeds that impair the development of pasture and livestock worldwide. These plants belong to three genera of the Fabaceae family (Astragalus, Oxytropis e Swainsona) (Burrows & Tyrl 2012Burrows G.E. & Tyrl R.J. 2012. Toxic Plants of North America. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, Iowa. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118413425>.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118413425...

, Cook et al. 2009Cook D., Ralphs M.H., Welch K.D. & Stegelmeier B.L. 2009. Locoweed poisoning in livestock. Rangelands J. 31(1):16-21. <http://dx.doi.org/10.2111/1551-501X-31.1.16>

https://doi.org/10.2111/1551-501X-31.1.1...

, 2014Cook D., Gardner D.R. & Pfister J.A. 2014. Swainsonine-containing plants and their relationship to endophytic fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7326-7334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r> <PMid:24758700>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r...

), one genus of the Convolvulaceae family (Ipomoea) and one genus of the Malvaceae family (Sida) (Oliveira Júnior et al. 2013Oliveira Júnior C.A., Riet-Correa G. & Riet-Correa F. 2013. Intoxicação por plantas que contêm swainsonina no Brasil. Ciência Rural 43(4):653-661. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013000400014>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-8478201300...

) and are distributed mainly in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Russia, Spain, Ireland, Morocco, Egypt, Australia and China (Jung et al. 2011Jung J.-K., Lee S.-U., Kozukue N., Levin C.E. & Friedman M. 2011. Distribution of phenolic compounds and antioxidative activies in parts of sweet potato (Ipomoea batata L.) plants and in home processed roots. J. Food Comp. Analysis 24(1):29-37. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.025>

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.0...

, Cook et al. 2014Cook D., Gardner D.R. & Pfister J.A. 2014. Swainsonine-containing plants and their relationship to endophytic fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7326-7334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r> <PMid:24758700>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r...

, Oliveira Júnior et al. 2013Oliveira Júnior C.A., Riet-Correa G. & Riet-Correa F. 2013. Intoxicação por plantas que contêm swainsonina no Brasil. Ciência Rural 43(4):653-661. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013000400014>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-8478201300...

).

Swainsonine is a polyhydroxy alkaloid, a potent inhibitor of lysosomal α-mannosidase and α-mannosidase II of Golgi apparatus of neurons and epithelial cells. Some calystegines are potent glycosidases inhibitors and is suggested to disrupt intestinal glycosidases, lysosomal function and glycoprotein processing causing enzymatic dysfunction and accumulation of complex oligosaccharides in lysosomes (Colegate et al. 1979Colegate S.M., Dorling P.R. & Huxtable C.R. 1979. A spectroscopic investigation of swainsonine: an alpha-mannosidase inhibitor isolated from Swainsona canescens. Aust. J. Chem. 32(10):2257-2264. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/CH9792257>

https://doi.org/10.1071/CH9792257...

, Dorling et al. 1980Dorling P.R., Huxtable C.R. & Colegate S.M. 1980. Inhibition of lysosomal alpha-mannosidase by swainsonine, an indolizidine alkaloid isolated from Swainsona canescens. Biochem. J. 191(2):649-651. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/bj1910649> <PMid:6786280>

https://doi.org/10.1042/bj1910649...

, Stegelmeier et al. 2008Stegelmeier B.L., Molyneux R.J., Asano N., Watson A.A. & Nash R.J. 2008. The comparative pathology of the glycosidase inhibitors swainsonine, castanospermine, and calystegines A3, B2, and C1 in mice. Toxicol. Pathol. 36(5):651-659. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192623308317420> <PMid:18497426>

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623308317420...

). Recent research has shown that swainsonine is a secondary metabolite resulting from endophytic fungi and is not therefore produced by the host plant. The presence of endophytic fungi was demonstrated in Astragalus, Oxytropis, Swainsona and Ipomoea species (Braun et al. 2003Braun K., Romero J., Liddell C. & Creamer R. 2003. Production of swainsonine by fungal endophytes of locoweed. Mycol. Res. 107(Pt 8):980-988. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S095375620300813X> <PMid:14531620>

https://doi.org/10.1017/S095375620300813...

, Pryor et al. 2009Pryor B.M., Creamer R., Shoemaker R.A., McLain-Romero J. & Hambleton S. 2009. Undifilum, a new genus for endophytic Embellisia oxytropis and parasitic Helminthosporium bornmuelleri on legumes. Botany 87(2):178-194. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/B08-130>

https://doi.org/10.1139/B08-130...

, Hao et al. 2012Hao L., Chen J.P., Lu W., Ma Y., Zhao B.Y. & Wang J.Y. 2012. Isolation and identification of swainsonine-producing fungi found in locoweeds and their rhizosphere soil. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6(23):4959-4969., Cook et al. 2014Cook D., Gardner D.R. & Pfister J.A. 2014. Swainsonine-containing plants and their relationship to endophytic fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7326-7334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r> <PMid:24758700>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r...

). However, it is suggested that calystegines are secondary metabolites resulting from plants as it has been demonstrated in a previous study when these toxins remained present even in plants derived from seeds treated with fungicides (Cook et al. 2013Cook D., Beaulieu W.T., Mott I.W., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Grum D., Pfister J.A., Clay K. & Marcolongo-Pereira C. 2013. Production of the alkaloid swainsonine by a fungal endosymbiont of the ascomycete order chaetothyriales in the host Ipomoea carnea. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 61(16):3797-3803. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423> <PMid:23547913>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423...

).

Clinical signs presented by ruminants and horses grazing swainsonine-containing plants consists mainly in neurological disorders, although endocrine and reproductive alterations may also occur (Oliveira et al. 2011Oliveira C.A., Riet-Correa F., Dutra M.D., Cerqueira D.V., Araújo C.V. & Riet-Correa G. 2011. Sinais clínicos, lesões e alterações produtivas e reprodutivas em caprinos intoxicados por Ipomoea carnea subsp. fistulosa (Convolvulaceae) que deixaram de ingerir a planta. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 31(11):953-960. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2011001100003>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X201100...

, Tokarnia et al. 2012Tokarnia C.H., Brito M.F., Barbosa J.D., Peixoto P.V. & Döbereiner J. 2012. Plantas Tóxicas do Brasil para Animais de Produção. 2ª ed. Helianthus, Rio de Janeiro.). Neurological changes observed are mainly of cerebellar origin, evidenced by loss of balance, followed by falls when the animals are stressed, ataxia, hypermetria, dysmetria, nystagmus, lateral gait and head and neck tremors. After the falls, the animals have difficulty into raising up and may present spasticity of the hindlimbs. Other alterations, such as somnolence, progressive emaciation and bristly, brittle and opaque hair may be observed (Tokarnia et al. 2012Tokarnia C.H., Brito M.F., Barbosa J.D., Peixoto P.V. & Döbereiner J. 2012. Plantas Tóxicas do Brasil para Animais de Produção. 2ª ed. Helianthus, Rio de Janeiro., Mendonça et al. 2011Mendonça F.S., Evêncio-Neto J., de Albuquerque R.F., Driemeir D., Camargo L.M., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Caldeira F.H.B. & Colodel E.M. 2011. Spontaneous poisoning by Ipomoea sericophylla (Convolvulaceae) in goats at semi-arid region of Pernambuco, Brazil: a case report. Acta Vet. Brno 80(2):235-239. <http://dx.doi.org/10.2754/avb201180020235>

https://doi.org/10.2754/avb201180020235...

, 2012Mendonça F.S., Albuquerque R.F., Evêncio-Neto J., Freitas S.H., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Driemeier D., Gardner D.R., Riet-Correa F. & Colodel E.M. 2012. Alpha-mannosidosis in goats caused by the swainsonine-containing plant Ipomoea verbascoidea. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24(1):90-95. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948> <PMid:22362938>

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948...

, Lima et al. 2013Lima D.D.C.C., Albuquerque R.F., Rocha B.P., Barros M.E.G., Gardner D.R., Medeiros R.M.T., Riet-Correa F. & Mendonça F.S. 2013. Doença de depósito lisossomal induzida pelo consume de Ipomoea verbascoidea (Convolvulaceae) em caprinos no semiárido de Pernambuco. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 33(7):867-872. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013000700007>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X201300...

, Oliveira Júnior et al. 2013Oliveira Júnior C.A., Riet-Correa G. & Riet-Correa F. 2013. Intoxicação por plantas que contêm swainsonina no Brasil. Ciência Rural 43(4):653-661. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013000400014>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-8478201300...

, Rocha et al. 2016Rocha B.P., Reis M.O., Diemeier D., Cook D., Camargo L.M., Riet-Correa F., Evêncio-Neto J. & Mendonça F.S. 2016. Biópsia hepatica como método diagnóstico para intoxicação por plantas que contém swainsonina. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 36(5):373-377. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2016000500003>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X201600...

).

Convolvulaceae family has a wide distribution worldwide, comprises 60 genera and at least 1.900 species. Ipomoea and Jacquemontia are being the most representative genera of this family with most of their species endemic in Brazil (Staples 2012Staples G. 2012. Convolvulaceae: the morning glories and bindweeds. Available at <Available at http://convolvulaceae.myspecies.info/node/9

> Accessed on Feb. 17, 2018.

http://convolvulaceae.myspecies.info/nod...

, Bianchinni & Ferreira 2013Bianchinni R.S. & Ferreira P.P.A. 2013. Convolvulaceae. Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil. Available at <Available at http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/listaBrasil/ConsultaPublicaUC/BemVindoConsultaPublicaConsultar.do

> Accessed on Jun. 10, 2013.

http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/listaBr...

, Buril et al. 2015Buril M.T., Simões A.R., Carine M. & Alves M. 2015. Daustinia, a replacement name for Austinia (Convolvulaceae). Phytotaxa J. 197(1):60-60. <http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.197.1.8>

https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.197.1...

). During epidemiological investigations of neurological diseases in ruminants, especially goats in the semiarid region of Pernambuco, our research team has observed outbreaks of lysosomal storage disease in which several species of Ipomoea could be associated to the disease, some of them being known to be toxic but in another hand, most species remains unknown about their alkaloid contents and toxicity. For this reason, the aim of this study was to determine swainsonine and calystegines concentrations in species of Convolvulaceae from the semiarid region of the State of Pernambuco.

Materials and Methods

This study was performed in the microregion of the Sertão do Moxotó, Pernambuco, in the municipalities of Arcoverde, Sertânia, Betânia, Ibimirim, Custódia, Inajá and Manari. The weather in these municipalities is semiarid, with high temperatures and scarce and badly distributed raining. The characteristic vegetation is the Brazilian Caatinga Savannah. This study was performed during the rainy season in 2017, which comprehends the months from March to June. The main highways of those municipalities and bordering roads throughout rock outcrops and livestock farms and were car-driven with an average speed of 18 mph making a minimum distance of 62 miles and a maximum of 124 miles in each municipality, to collect and determine the occurrence of Convolvulaceae species. Those species observed during the rout were collected for botanical identification and vouchers were deposited in Vasconcelos Sobrinho Herbarium of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco. Samples containing 500g of leaves from each species (five individuals by species) were collected, dry shaded, crushed, mixed to create a pool of samples and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-APCI-MS) method, according to the procedures described by Gardner et al. (2001)Gardner D.R., Molyneux R.J. & Ralphs M.H. 2001. Analysis of swainsonine: extraction methods, detection and measurement in populations of locoweeds (Oxytropis spp.). J. Agricult. Food Chem. 49(10):4573-4580. <PMID: 11599990>.

Samples (100g) of the dry vegetal material were used to obtain extract and posterior analysis for presence of swainsonine by ion exchange resin insulation. The aqueous extract was then analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry using a HP 1100 binary solvent pump, an automatic sampler, a HPLC column of Betasil C18 reverse phase (100x2mm) and a Finnigan LCQ mass spectrometer. Swainsonine was eluted using an isocratic mixture of 5% methanol in 20 mM ammonium acetate at a flow rate of 0.5mL/min. The size of the sample injection was 20 μL. Ionization was achieved using an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source with a vaporization temperature of 450°C and a corona discharge current of 5 μA. The mass spectrometer was conducted in a MS/MS mode, examining the ions of the products in a mass range of 70-300 amu after the fragmentation of the protonated swainsonine molecule using a relative collision energy setting of 25%.

The area of the swainsonine peak was measured from the reconstructed-ion chromatogram (m/z 156) and the quantification was based in an external standard calibration. The presence of swainsonine was verified through gas chromatography - mass spectrometry (GC/MS) after a portion from the aqueous extract was dried and the residue derived by the addition of N,O-bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) and pyridine to convert swainsonine into its timesilil ether derivative. GC/MS analysis was performed using an electronic therm GC/MS system installed with an Agilent DB-5MS capillary column (30m×0.25mm). Helium was used as a carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The samples (2.0μL) were injected using a split/splitless injector with a temperature of 250 °C. The column temperature was programmed at 120°C for 1 min, increased from 120 to 200°C at 5°C/min and from 200 to 300°C at 20°C/min and then maintained at 300°C for 8 min. The presence of calystegines was determined using the same GC/MS data to verify the existence of swainsonine.

The plants were photographed and the data on their occurrence were compared with the pluviometric indexes of each municipality, according to data from the Instituto Agronômico de Pernambuco (IPA).

Results

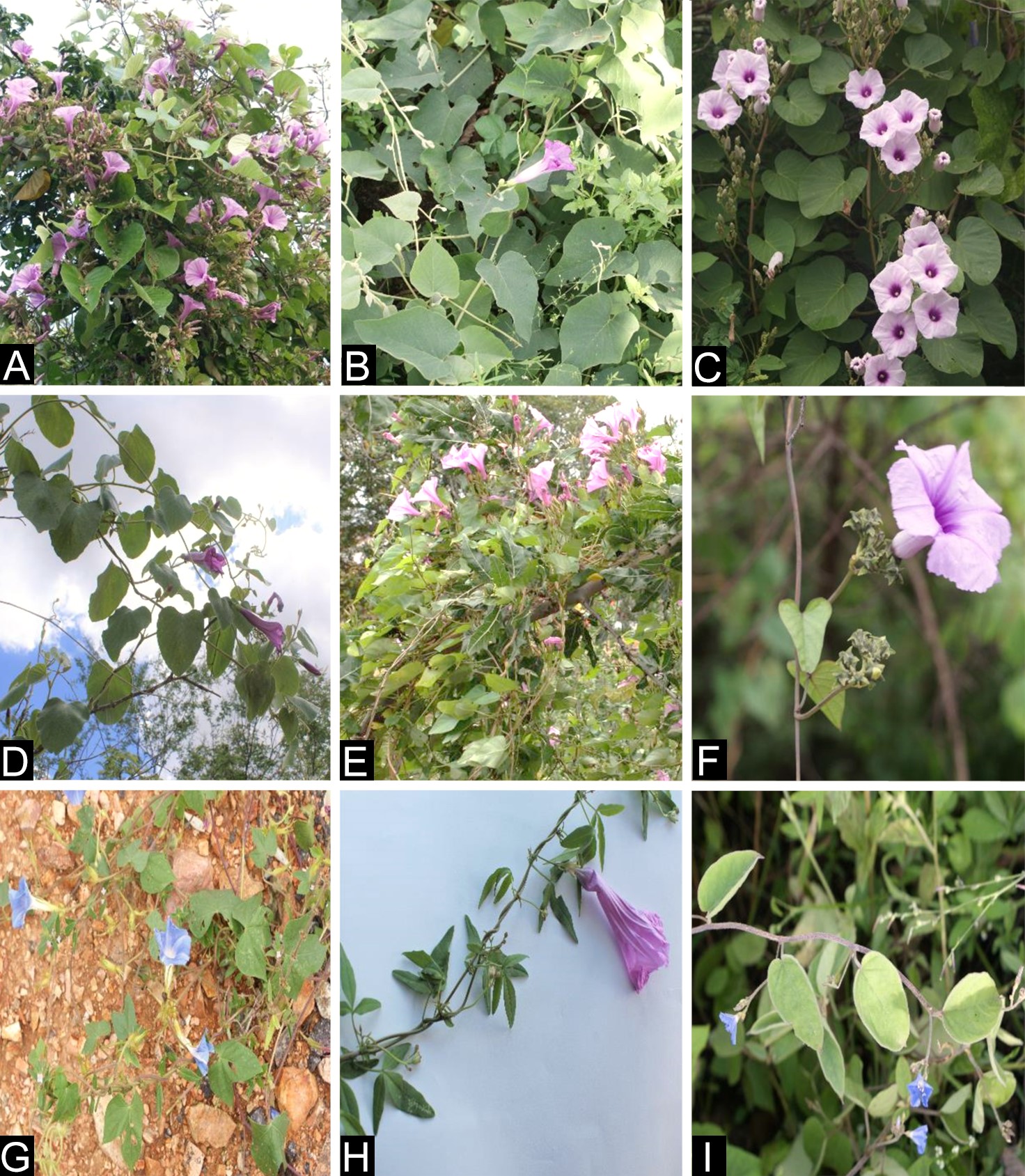

In the municipalities that comprise the Sertão do Moxotó region, eight species of Ipomoea and one species of Jacquemonthia (Fig.1) were identified containing variable concentrations of swainsonine and calystegines (Table 1). Most species were found in Sertânia (seven in total). In this municipality the average rainfall in the last three months that preceded the collection of plants was 36.6mm and the annual average rainfall was 34mm, with more significant rains occurring from March to July. The species most observed and in higher amounts was Ipomoea sericosepala, which contained only calystegines (B1 0.013%, B2<0.001% and C1 0.002%) and I. brasiliana, which also contained only calystegines (B1 0.019%, B2 0.005% and C1 0.031%). Two other species were also observed frequently, however one contained both swainsonine and calystegines in its composition, identified as I. megapotamica (swainsonine 0.016%, calystegines B1 0.024%, B2 0.001%, B3 0.002% and C1 0.003%) and the other one, identified as I. subincana contained only swainsonine, in the concentration of 0.011%. Ipomoea sericosepala and I. brasiliana were observed both on the main highways and bordering roads, covering fences of the farms and shrubs in most of rock outcrops. At the collection sites, numerous sprouts were observed, as well as well-developed adult individuals up to 2.5m in height and abundant leaf mass. In the rock outcrops, where usually goats and sheep gather for pasture it was common to observe these animals ingesting three or four species of Ipomoea that vegetated simultaneously, some covering the others (Fig.2). In this situation it was possible to observe specially I. sericosepala, I. brasiliana, I. megapotamica and I. subincana. The other species of Ipomoea were not so abundant and were only seen occasionally; however, they contained concentrations of both swainsonine and calystegines.

Species of Ipomoea in flowering phase during the rainy season of 2017, Sertão do Moxotó/PE, Brazil. (A) Ipomoea sericosepala, (B)Ipomoea brasiliana, (C) Ipomoea megapotamica, (D) Ipomoea subincana and (E) Ipomoea incarnata in April, municipality of Sertânia. (F) Ipomoea bahiensis in May, municipality of Manari. (G) Ipomoea nil in May, municipality of Betânia. (H) Ipomoea rosea in June, municipality of Manari. (I) Jacquemontia corymbulosa in May, municipality of Manari.

Pasture areas of goats in Sertão do Moxotó/PE, Brazil. (A) Pasture mainly formed by Froelichia humboldtiana and shrubs of Ipomoea brasiliana in sprouting phase (arrows), Inajá, July of 2017. (B) Caatinga area in the rainy season, with available forage and despite this, goats present predilection for Ipomoea sericosepala and (C) goat showing preference for Ipomoea megapotamica instead of other forages during the rainy season.

In Manari, three species of Ipomoea and one of Jacquemontia were observed. In this municipality the average rainfall of the last three months previous the collection of plants was 81.3mm and the annual rainfall was 67.5mm, with significant rains occurring from April to August (Fig.3). The main species observed was I. sericosepala. The mean concentration of swainsonine in this species was 0.011% and the concentration of calystegines B1, B2, B3 and C1 was 0.012%, 0.001%, 0.002% and 0.003% respectively. Ipomoea bahiensis was the second more frequent species observed; the analyses identified only calystegines B2 (0.061%) and C1 (0.002%) in this plant composition. Jacquemontia corymbulosa was the third more common species found both on the roads and near the fences of the farms, forming an abundant leaf mass, sometimes covering extensive areas of soil and pasture. The mean concentration of both swainsonine and calystegine B2 in these species was 0.01%. No concentrations of indolizidine alkaloids were detected in Ipomoea rosea collected from this region.

Pluviometric index in the municipalities that comprehend the Sertão do Moxotó region, Brazil. Notice March, April, May, June and July months had higher levels of rainfall, these periods could be associated with presence of Convolvulaceae in the studied region and when cases of lysosomal storage disease may occur.

In Betânia, the most species observed was I. sericosepala and I. nil was seen occasionally, occurring only at borders of highways. The average rainfall in the period before the collection was 73.7mm with intense raining indexes from March to April. Swainsonine concentration in I. sericosepala was 0.012% and calystegines B1, B2 and C1 were 0.013%, 0.001% and <0.002%, respectively. Only calystegines B1, B2 and C1 were detected in I. nil, the average concentrations were 0.003%, 0.007% and 0.001%, respectively. In Custódia and Ibimirim only two species of Ipomoea were observed, one in each municipality. The mean rainfall in Custódia in the period before the collection was 73.8mm with intense raining indexes from May to July; In Ibimirim the mean rainfall was 61.4mm with intense raining period from March to May. In Custódia only the occurrence of I. nil was observed and the presence of indolizidine alkaloids was not detected. The mean rainfall in the period before the collection of I. nill in Custódia was 117.4mm with rains from April to May. In I. rosea collected from Ibimirim, swainsonine concentration was 0.07% and calystegines B1, B2 and C1 were 0.001%, 0.003% and <0.001% respectively. In both municipalities amounts of these plants were not expressive and the observation was occasional.

In Arcoverde only I. nil was observed; swainsonine was not detected in this plant and concentrations of calystegines B1, B2 and C1 were 0.002%, 0.008% and 0.001%. In Inajá only I. brasiliana was observed, in which contained calystegines B2 (<0.001) and C1 (0.001). In Arcoverde, the average rainfall was 73.8mm with more intense rains from May to July. In Inajá the average was 35mm, with pluviometric indexes with below-average rainfall, compared to other municipalities. The distribution of Ipomoea species in the studied municipalities are displaced in Figure 4.

Distribution of the Ipomoea species found during the study in Sertão do Moxotó/PE, Brazil. It is observed that some regions have larger variability and predominance of species.

Discussion

In this study six new species of Ipomoea (I. subincana, I. megapotamica, I. rosea, I. bahiensis, I. incarnata and I. nil) and one species of Jacquemontia (J. corymbulosa) are presented, containing toxic concentrations of swainsonine and/or calystegines. All these species are endemic from the Brazilian caatinga biome (Oliveira et al. 2013Oliveira D.G., Prata A.P. & Ferreira R.A. 2013. Herbáceas da Caatinga: composição florística, fitossociologia e estratégias de sobrevivência em uma comunidade vegetal. Agraria. 8(4):623-633. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v8i4a2682>

https://doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v8i4a268...

) and their importance as toxic plants for livestock must be investigated in all the Brazilian semiarid region. Two species most founded were I. sericosepala (previously Turbina cordata) (Wood et al. 2015Wood J.R.I., Carine M.A., Harris D., Wilkin P., Williams B. & Scotland R.W. 2015. Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in Bolivia. Kew Bulletin 70(3):30-154. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12225-015-9592-7>

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-015-9592-...

) and I. brasiliana (previously reported as I. marcellia and I.aff. verbascoidea) (Mendonça et al. 2012Mendonça F.S., Albuquerque R.F., Evêncio-Neto J., Freitas S.H., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Driemeier D., Gardner D.R., Riet-Correa F. & Colodel E.M. 2012. Alpha-mannosidosis in goats caused by the swainsonine-containing plant Ipomoea verbascoidea. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24(1):90-95. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948> <PMid:22362938>

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948...

, Rocha et al. 2016Rocha B.P., Reis M.O., Diemeier D., Cook D., Camargo L.M., Riet-Correa F., Evêncio-Neto J. & Mendonça F.S. 2016. Biópsia hepatica como método diagnóstico para intoxicação por plantas que contém swainsonina. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 36(5):373-377. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2016000500003>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X201600...

, Simão-Bianchini & Ferreira 2015Simão-Bianchini R. & Ferreira P.P.A. 2015. Ipomoea in Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Available at <Available at http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB17002

> Accessed on Jan. 10, 2018.

http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/f...

). Ipomoea sericosepala has been reported as toxic to goats, cattle and horses (Dantas et al. 2007Dantas A.F.M., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Medeiros R.M.T., Barros S.S., Anjos B.L. & Lucena R.B. 2007. Swainsonine-induced lysosomal storage disease in goats caused by the ingestion of Turbinata cordata in North-eastern Brazil. Toxicon 49(1):111-116. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.08.012> <PMid:17030054>

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.0...

, Assis et al. 2010Assis T.S., Medeiros R.M.T., Riet-Correa F., Galiza G.J.N., Dantas A.F.M. & Oliveira D.M. 2010. Intoxicações por plantas diagnosticadas em ruminantes e equinos e estimativa das perdas econômicas na Paraíba. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 30(1):13-20. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2010000100003>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X201000...

, Oliveira Júnior et al. 2013Oliveira Júnior C.A., Riet-Correa G. & Riet-Correa F. 2013. Intoxicação por plantas que contêm swainsonina no Brasil. Ciência Rural 43(4):653-661. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013000400014>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-8478201300...

) and I. brasiliana so far has only been reported as important to goats (Mendonça et al. 2012Mendonça F.S., Albuquerque R.F., Evêncio-Neto J., Freitas S.H., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Driemeier D., Gardner D.R., Riet-Correa F. & Colodel E.M. 2012. Alpha-mannosidosis in goats caused by the swainsonine-containing plant Ipomoea verbascoidea. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24(1):90-95. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948> <PMid:22362938>

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948...

, Lima et al. 2013Lima D.D.C.C., Albuquerque R.F., Rocha B.P., Barros M.E.G., Gardner D.R., Medeiros R.M.T., Riet-Correa F. & Mendonça F.S. 2013. Doença de depósito lisossomal induzida pelo consume de Ipomoea verbascoidea (Convolvulaceae) em caprinos no semiárido de Pernambuco. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 33(7):867-872. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013000700007>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X201300...

). In previous studies, in both I. sericosepala and I. brasiliana significant amounts of swainsonine and calystegines were detected. Nonetheless, several samples of both plants were negative for swainsonine. This occurs because the swainsonine concentration varies considerably among species, since the production of this toxin is dependent on the presence of endophytic fungi. Calystegines, on the other hand, are secondary metabolites produced by plants (Cook et al. 2013Cook D., Beaulieu W.T., Mott I.W., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Grum D., Pfister J.A., Clay K. & Marcolongo-Pereira C. 2013. Production of the alkaloid swainsonine by a fungal endosymbiont of the ascomycete order chaetothyriales in the host Ipomoea carnea. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 61(16):3797-3803. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423> <PMid:23547913>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423...

).

It is important to emphasize these species presented here grows during rainy season and its leaves dry and fall at the beginning of the drought, after the fructification, resprouting again at the beginning of the the rains (Barbosa et al. 2006Barbosa R.C., Riet-Correa F., Medeiros R.M.T., Lima E.F., Barros S.S., Gimeno E.J., Molyneux R.J. & Gardner D.R. 2006. Intoxication by Ipomoea sericophylla and Ipomoea riedelii in goats in the state of Paraíba, northestern Brazil. Toxicon 47(4):371-379. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.11.010> <PMid:16488457>

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.1...

, Mendonça et al. 2011Mendonça F.S., Evêncio-Neto J., de Albuquerque R.F., Driemeir D., Camargo L.M., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Caldeira F.H.B. & Colodel E.M. 2011. Spontaneous poisoning by Ipomoea sericophylla (Convolvulaceae) in goats at semi-arid region of Pernambuco, Brazil: a case report. Acta Vet. Brno 80(2):235-239. <http://dx.doi.org/10.2754/avb201180020235>

https://doi.org/10.2754/avb201180020235...

, 2012Mendonça F.S., Albuquerque R.F., Evêncio-Neto J., Freitas S.H., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Driemeier D., Gardner D.R., Riet-Correa F. & Colodel E.M. 2012. Alpha-mannosidosis in goats caused by the swainsonine-containing plant Ipomoea verbascoidea. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24(1):90-95. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948> <PMid:22362938>

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948...

). For this reason, it is necessary the study of pluviometric indexes, because high raining’s could indicate the most favorable months for poisoning by these plants in ruminants and horses. Thus, considering the average rainfall of 2017 in the Sertão do Moxotó region, the most favorable months to occur outbreaks of lysosomal storage disease in herbivores are from March to July (Fig.3).

Several species of the Convolvulaceae family are non-toxic and are important fodder that should be used as animal feed (Cook et al. 2013Cook D., Beaulieu W.T., Mott I.W., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Grum D., Pfister J.A., Clay K. & Marcolongo-Pereira C. 2013. Production of the alkaloid swainsonine by a fungal endosymbiont of the ascomycete order chaetothyriales in the host Ipomoea carnea. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 61(16):3797-3803. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423> <PMid:23547913>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423...

), especially in northeastern semiarid region due to the animal food scarcity that frequently occurs in this region. However, several species are toxic to ruminants, horses and wildlife (Cook et al. 2013Cook D., Beaulieu W.T., Mott I.W., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Grum D., Pfister J.A., Clay K. & Marcolongo-Pereira C. 2013. Production of the alkaloid swainsonine by a fungal endosymbiont of the ascomycete order chaetothyriales in the host Ipomoea carnea. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 61(16):3797-3803. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423> <PMid:23547913>

https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423...

) and should therefore be studied. Thus, according to the results presented in this study, I. subincana, I. megapotamica, I. rosea and Jacquemontia corymbulosa presented a significative toxicity potential to herbivores, since they had swainsonine concentrations equal or higher than 0.001% (Molyneux et al. 1995Molyneux R.J., McKenzie R.A., O’Sullivan B.M. & Elbein A.D. 1995. Identification of the glycosidase inhibitors swainsonine and calystegine B2 in Weir vine (Ipomoea sp. Q6 [aff. calobra]) and correlation with toxicity. J. Nat. Prod. 58(6):878-886. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/np50120a009> <PMid:7673932>

https://doi.org/10.1021/np50120a009...

). So far, the toxicity determination of these species still must be proven experimentally. For species containing only calystegines, such as I. bahiensis, I. incarnata and I. nil, additional studies should be conducted to prove the toxicity of these compounds in ruminants (without simultaneous action of swainsonine). In vitro, calystegines are potent inhibitors of hydrolases, but studies in rats have shown negative results on the development of lysosomal storage disease in this species. Another aspect to be considered is that I. bahiensis, I. incarnata and I. nil may present swainsonine in their composition, similarly to what was observed with I. sericosepala and I. brasiliana which sometimes presented or not swainsonine concentrations.

Considering our field observations over the past 10 years in the Sertão do Moxotó region about plant poisoning in ruminants, it is important to be noted that, unlike what occurs with I. carnea subsp. fistulosa, most of the species presented in this study have good palatability and be one of the feeding choices for goats, even when other forages are present. Perhaps because of that, in addition to the wide variety of species that contain swainsonine and calystegines, poisoning by plants containing these alkaloids are so frequent in the northeastern semiarid region, if considered the reported case numbers. Another factor that contributes to the occurrence of poisonings is the social facilitation mechanism, in which animals that start the ingestion of these plants develop the habit of compulsively ingesting them and, by influence, induce other animals of the same species to ingest them (Tokarnia et al. 1960Tokarnia C.H., Döbereiner J. & Canella C.F.C. 1960. Estudo experimental sobre a toxidez do “canudo” (Ipomoea fistula Mart.) em ruminantes. Arqs Inst. Biol. Animal, Rio de Janeiro, 3:59-71., Driemeier et al. 2000Driemeier D., Colodel E.M., Gimeno E.J. & Barros S.S. 2000. Lysossomal storage disease caused by Sida carpinifolia poisoning in goats. Vet. Pathol. 37(2):153-159. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1354/vp.37-2-153> <PMid:10714644>

https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.37-2-153...

, Colodel et al. 2002Colodel E.M., Driemeier D., Loretti A.P., Gimeno E.J., Traverso S.D., Seitz A.L. & Zlotowski P. 2002. Aspectos clínicos e patológicos da intoxicação por Sida carpinifolia (Malvaceae) em caprinos no Rio de Grande do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 22(2):51-57. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2002000200004>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X200200...

, Dantas et al. 2007Dantas A.F.M., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Medeiros R.M.T., Barros S.S., Anjos B.L. & Lucena R.B. 2007. Swainsonine-induced lysosomal storage disease in goats caused by the ingestion of Turbinata cordata in North-eastern Brazil. Toxicon 49(1):111-116. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.08.012> <PMid:17030054>

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.0...

, Barbosa et al. 2007Barbosa R.C., Riet-Correa F., Lima E.F., Medeiros R.M.T., Guedes K.M.R., Gardner D.R., Molyneux R.J. & Melo L.E.H. 2007. Experimental swainsonine poisoning in goats ingesting Ipomoea sericophylla and Ipomoea riedelii (Convolvulaceae). Pesq. Vet. Bras. 27(10):409-414. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2007001000004>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X200700...

, Oliveira et al. 2009Oliveira C.A., Barbosa J.D., Duarte M.D., Cerqueira V.D., Riet-Correa F., Tortelli F.P. & Riet-Correa G. 2009. Intoxicação por Ipomoea carnea subsp. fistulosa (Convolvulaceae) em caprinos na Ilha do Marajó, Pará. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 29(7):583-588. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000700014>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X200900...

, Mendonça et al. 2012Mendonça F.S., Albuquerque R.F., Evêncio-Neto J., Freitas S.H., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Driemeier D., Gardner D.R., Riet-Correa F. & Colodel E.M. 2012. Alpha-mannosidosis in goats caused by the swainsonine-containing plant Ipomoea verbascoidea. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24(1):90-95. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948> <PMid:22362938>

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948...

).

Conclusions

The discovery of new species of Ipomoea and Jacquemontia containing toxic polyhydroxy alkaloids reinforces the importance of this group of poisonous plants for ruminants and horses in the Pernambuco semiarid region.

Epidemiological research must be conducted to investigate the occurrence of lysosomal storage disease associated with these new species.

Acknowledgments

To the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for granting the necessary financial support for the development of this study (grant 471180/2013 and 309725/2015). To Dra. Rosangela Simão-Bianchini, researcher at the São Paulo Botanical Institute, for the collaboration in the identification of some species of Ipomoea.

References

- Assis T.S., Medeiros R.M.T., Riet-Correa F., Galiza G.J.N., Dantas A.F.M. & Oliveira D.M. 2010. Intoxicações por plantas diagnosticadas em ruminantes e equinos e estimativa das perdas econômicas na Paraíba. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 30(1):13-20. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2010000100003>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2010000100003 - Barbosa R.C., Riet-Correa F., Medeiros R.M.T., Lima E.F., Barros S.S., Gimeno E.J., Molyneux R.J. & Gardner D.R. 2006. Intoxication by Ipomoea sericophylla and Ipomoea riedelii in goats in the state of Paraíba, northestern Brazil. Toxicon 47(4):371-379. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.11.010> <PMid:16488457>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.11.010 - Barbosa R.C., Riet-Correa F., Lima E.F., Medeiros R.M.T., Guedes K.M.R., Gardner D.R., Molyneux R.J. & Melo L.E.H. 2007. Experimental swainsonine poisoning in goats ingesting Ipomoea sericophylla and Ipomoea riedelii (Convolvulaceae). Pesq. Vet. Bras. 27(10):409-414. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2007001000004>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2007001000004 - Bianchinni R.S. & Ferreira P.P.A. 2013. Convolvulaceae. Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil. Available at <Available at http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/listaBrasil/ConsultaPublicaUC/BemVindoConsultaPublicaConsultar.do > Accessed on Jun. 10, 2013.

» http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/listaBrasil/ConsultaPublicaUC/BemVindoConsultaPublicaConsultar.do - Braun K., Romero J., Liddell C. & Creamer R. 2003. Production of swainsonine by fungal endophytes of locoweed. Mycol. Res. 107(Pt 8):980-988. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S095375620300813X> <PMid:14531620>

» https://doi.org/10.1017/S095375620300813X - Buril M.T., Simões A.R., Carine M. & Alves M. 2015. Daustinia, a replacement name for Austinia (Convolvulaceae). Phytotaxa J. 197(1):60-60. <http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.197.1.8>

» https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.197.1.8 - Burrows G.E. & Tyrl R.J. 2012. Toxic Plants of North America. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, Iowa. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118413425>.

» https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118413425 - Colegate S.M., Dorling P.R. & Huxtable C.R. 1979. A spectroscopic investigation of swainsonine: an alpha-mannosidase inhibitor isolated from Swainsona canescens Aust. J. Chem. 32(10):2257-2264. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/CH9792257>

» https://doi.org/10.1071/CH9792257 - Colodel E.M., Driemeier D., Loretti A.P., Gimeno E.J., Traverso S.D., Seitz A.L. & Zlotowski P. 2002. Aspectos clínicos e patológicos da intoxicação por Sida carpinifolia (Malvaceae) em caprinos no Rio de Grande do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 22(2):51-57. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2002000200004>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2002000200004 - Cook D., Gardner D.R. & Pfister J.A. 2014. Swainsonine-containing plants and their relationship to endophytic fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7326-7334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r> <PMid:24758700>

» https://doi.org/10.1021/jf501674r - Cook D., Ralphs M.H., Welch K.D. & Stegelmeier B.L. 2009. Locoweed poisoning in livestock. Rangelands J. 31(1):16-21. <http://dx.doi.org/10.2111/1551-501X-31.1.16>

» https://doi.org/10.2111/1551-501X-31.1.16 - Cook D., Beaulieu W.T., Mott I.W., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Grum D., Pfister J.A., Clay K. & Marcolongo-Pereira C. 2013. Production of the alkaloid swainsonine by a fungal endosymbiont of the ascomycete order chaetothyriales in the host Ipomoea carnea J. Agricult. Food Chem. 61(16):3797-3803. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423> <PMid:23547913>

» https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4008423 - Dantas A.F.M., Riet-Correa F., Gardner D.R., Medeiros R.M.T., Barros S.S., Anjos B.L. & Lucena R.B. 2007. Swainsonine-induced lysosomal storage disease in goats caused by the ingestion of Turbinata cordata in North-eastern Brazil. Toxicon 49(1):111-116. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.08.012> <PMid:17030054>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.08.012 - Dorling P.R., Huxtable C.R. & Colegate S.M. 1980. Inhibition of lysosomal alpha-mannosidase by swainsonine, an indolizidine alkaloid isolated from Swainsona canescens Biochem. J. 191(2):649-651. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/bj1910649> <PMid:6786280>

» https://doi.org/10.1042/bj1910649 - Driemeier D., Colodel E.M., Gimeno E.J. & Barros S.S. 2000. Lysossomal storage disease caused by Sida carpinifolia poisoning in goats. Vet. Pathol. 37(2):153-159. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1354/vp.37-2-153> <PMid:10714644>

» https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.37-2-153 - Gardner D.R., Molyneux R.J. & Ralphs M.H. 2001. Analysis of swainsonine: extraction methods, detection and measurement in populations of locoweeds (Oxytropis spp.). J. Agricult. Food Chem. 49(10):4573-4580. <PMID: 11599990>

- Hao L., Chen J.P., Lu W., Ma Y., Zhao B.Y. & Wang J.Y. 2012. Isolation and identification of swainsonine-producing fungi found in locoweeds and their rhizosphere soil. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6(23):4959-4969.

- Jung J.-K., Lee S.-U., Kozukue N., Levin C.E. & Friedman M. 2011. Distribution of phenolic compounds and antioxidative activies in parts of sweet potato (Ipomoea batata L.) plants and in home processed roots. J. Food Comp. Analysis 24(1):29-37. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.025>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.025 - Lima D.D.C.C., Albuquerque R.F., Rocha B.P., Barros M.E.G., Gardner D.R., Medeiros R.M.T., Riet-Correa F. & Mendonça F.S. 2013. Doença de depósito lisossomal induzida pelo consume de Ipomoea verbascoidea (Convolvulaceae) em caprinos no semiárido de Pernambuco. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 33(7):867-872. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013000700007>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2013000700007 - Mendonça F.S., Albuquerque R.F., Evêncio-Neto J., Freitas S.H., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Driemeier D., Gardner D.R., Riet-Correa F. & Colodel E.M. 2012. Alpha-mannosidosis in goats caused by the swainsonine-containing plant Ipomoea verbascoidea J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24(1):90-95. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948> <PMid:22362938>

» https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425948 - Mendonça F.S., Evêncio-Neto J., de Albuquerque R.F., Driemeir D., Camargo L.M., Dória R.G.S., Boabaid F.M., Caldeira F.H.B. & Colodel E.M. 2011. Spontaneous poisoning by Ipomoea sericophylla (Convolvulaceae) in goats at semi-arid region of Pernambuco, Brazil: a case report. Acta Vet. Brno 80(2):235-239. <http://dx.doi.org/10.2754/avb201180020235>

» https://doi.org/10.2754/avb201180020235 - Molyneux R.J., McKenzie R.A., O’Sullivan B.M. & Elbein A.D. 1995. Identification of the glycosidase inhibitors swainsonine and calystegine B2 in Weir vine (Ipomoea sp. Q6 [aff. calobra]) and correlation with toxicity. J. Nat. Prod. 58(6):878-886. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/np50120a009> <PMid:7673932>

» https://doi.org/10.1021/np50120a009 - Oliveira C.A., Riet-Correa F., Dutra M.D., Cerqueira D.V., Araújo C.V. & Riet-Correa G. 2011. Sinais clínicos, lesões e alterações produtivas e reprodutivas em caprinos intoxicados por Ipomoea carnea subsp. fistulosa (Convolvulaceae) que deixaram de ingerir a planta. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 31(11):953-960. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2011001100003>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2011001100003 - Oliveira C.A., Barbosa J.D., Duarte M.D., Cerqueira V.D., Riet-Correa F., Tortelli F.P. & Riet-Correa G. 2009. Intoxicação por Ipomoea carnea subsp. fistulosa (Convolvulaceae) em caprinos na Ilha do Marajó, Pará. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 29(7):583-588. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000700014>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2009000700014 - Oliveira D.G., Prata A.P. & Ferreira R.A. 2013. Herbáceas da Caatinga: composição florística, fitossociologia e estratégias de sobrevivência em uma comunidade vegetal. Agraria. 8(4):623-633. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v8i4a2682>

» https://doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v8i4a2682 - Oliveira Júnior C.A., Riet-Correa G. & Riet-Correa F. 2013. Intoxicação por plantas que contêm swainsonina no Brasil. Ciência Rural 43(4):653-661. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013000400014>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013000400014 - Pryor B.M., Creamer R., Shoemaker R.A., McLain-Romero J. & Hambleton S. 2009. Undifilum, a new genus for endophytic Embellisia oxytropis and parasitic Helminthosporium bornmuelleri on legumes. Botany 87(2):178-194. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/B08-130>

» https://doi.org/10.1139/B08-130 - Rocha B.P., Reis M.O., Diemeier D., Cook D., Camargo L.M., Riet-Correa F., Evêncio-Neto J. & Mendonça F.S. 2016. Biópsia hepatica como método diagnóstico para intoxicação por plantas que contém swainsonina. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 36(5):373-377. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2016000500003>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2016000500003 - Simão-Bianchini R. & Ferreira P.P.A. 2015. Ipomoea in Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Available at <Available at http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB17002 > Accessed on Jan. 10, 2018.

» http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB17002 - Staples G. 2012. Convolvulaceae: the morning glories and bindweeds. Available at <Available at http://convolvulaceae.myspecies.info/node/9 > Accessed on Feb. 17, 2018.

» http://convolvulaceae.myspecies.info/node/9 - Stegelmeier B.L., Molyneux R.J., Asano N., Watson A.A. & Nash R.J. 2008. The comparative pathology of the glycosidase inhibitors swainsonine, castanospermine, and calystegines A3, B2, and C1 in mice. Toxicol. Pathol. 36(5):651-659. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192623308317420> <PMid:18497426>

» https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623308317420 - Tokarnia C.H., Döbereiner J. & Canella C.F.C. 1960. Estudo experimental sobre a toxidez do “canudo” (Ipomoea fistula Mart.) em ruminantes. Arqs Inst. Biol. Animal, Rio de Janeiro, 3:59-71.

- Tokarnia C.H., Brito M.F., Barbosa J.D., Peixoto P.V. & Döbereiner J. 2012. Plantas Tóxicas do Brasil para Animais de Produção. 2ª ed. Helianthus, Rio de Janeiro.

- Wood J.R.I., Carine M.A., Harris D., Wilkin P., Williams B. & Scotland R.W. 2015. Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in Bolivia. Kew Bulletin 70(3):30-154. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12225-015-9592-7>

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-015-9592-7

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Nov 2018

History

-

Received

07 July 2018 -

Accepted

19 July 2018