ABSTRACT:

Infection by Rhodococcus equi is considered one of the major health concerns for foals worldwide. In order to better understand the disease’s clinical and pathological features, we studied twenty cases of natural infection by R. equi in foals. These cases are characterized according to their clinical and pathological findings and immunohistochemical aspects. Necropsy, histologic examination, bacterial culture, R. equi and Pneumocystis spp. immunohistochemistry were performed. The foals had a mean age of 60 days and presented respiratory signs (11/20), hyperthermia (10/20), articular swelling (6/20), prostration (4/20), locomotor impairment (3/20) and diarrhea (3/20), among others. The main lesions were of pyogranulomatous pneumonia, seen in 19 foals, accompanied or not by pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis (10/20) and pyogranulomatous and ulcerative enterocolitis (5/20). Pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis was seen in 3 foals, one of which did not have pulmonary involvement. There was lymphoplasmacytic (4/20), lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic (1/20) or pyogranulomatous arthritis (1/20), affecting multiple or singular joints. Immunohistochemistry revealed to be a valuable tool for the detection of R. equi, confirming the diagnosis in all cases. Furthermore, pulmonary immunostaining for Pneumocystis spp. demonstrates that a coinfection with R. equi and this fungal agent is a common event in foals, seen in 13 cases.

INDEX TERMS:

Clinic; patology; Rhodococcus equi; infection; foals; equine infectious diseases; pneumonias of foals; rhodococcosis; horses; equine

RESUMO:

Infecção por Rhodococcus equi é considerado um dos maiores problemas sanitários para potros em todo o mundo. Para melhor compreender a apresentação clínica e patológica da enfermidade, foram avaliados vinte casos de infecção natural por R. equi em potros. Os casos são caracterizados de acordo com seus achados clínicos e patológicos e aspectos imuno-histoquímicos. Foram realizados exames de necropsia, histologia, bacteriologia e imuno-histoquímica para R. equi e Pneumocystis spp. Os potros tinham idade media de 60 dias e apresentaram sinais respiratórios (11/20), hipertermia (10/20), aumento de volume articular (6/20), prostração (4/20), distúrbios locomotores (3/20) e diarreia (3/20), entre outros. As lesões mais importantes eram pneumonia piogranulomatosa, vista em 19 potros, acompanhada ou não por linfadenite piogranulomatosa (10/20) e enterocolite ulcerativa (5/20). Osteomielite piogranulomatosa foi constatada em três potros, um dos quais não apresentava envolvimento pulmonar. Artrites afetando uma ou múltiplas articulações eram caracterizadas por infiltrado linfoplasmocítico (4/20), linfoplasmocítico e neutrofílico (1/20) e piogranulomatoso (1/20). A imuno-histoquímica demonstrou ser uma ferramenta valiosa na detecção de R. equi, permitindo confirmar o diagnóstico em todos os casos avaliados. Além disso, a imuno-histoquímica para Pneumocystis spp. demonstra que a coinfecção por R. equi e o agente fúngico é um evento frequente em potros, constatado em 13 casos.

TERMOS DE INDEXAÇÃO:

Clinica; patologia; infecção; Rhodococcus equi; potros; doenças infecciosas de equinos; pneumonias em potros; rodococose; equinos

Introduction

Rhodococcus equi infection is known worldwide as one of the major sanitary problems affecting foals up to six month old. In humans it is a concern, especially in immunosuppressed patients (Prescott 1987Prescott J.F. 1987. Epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi infection in horses. Vet. Microbiol. 14(3):211-214. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)90107-6> <PMid:3314106>

https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)901...

, 1991, Giguére & Prescott 1997Giguère S. & Prescott J.F. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):313-334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0> <PMid:9226845>

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00...

). Variable concentrations of the rod-to-coccus gram-positive nocardioform actinomycete can be found in horse farms, but infections occur depending on foal population density, temperature, dust, soil pH, as well as, a high proportion of virulent R. equi strains in the soil (Prescott 1991Prescott J.F. 1991. Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4(1):20-34. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.4.1.20> <PMid:2004346>

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.4.1.20...

, Takai 1997Takai S. 1997. Epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi infections: a review. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):167-176. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00085-0> <PMid:9226831>

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00...

, Meijer & Prescott 2004Meijer W.G. & Prescott J.F. 2004. Rhodococcus equi. Vet. Res. 35(4):383-396. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2004024> <PMid:15236672>

https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2004024...

).

The virulence of the strain is determined by a group of proteins called “Vap” (virulence-associated proteins), of which VapA is considered the most important for the development of the disease in foals (Takai et al. 1991Takai S., Koike K., Ohbushi S., Izumi C. & Tsubaki S. 1991. Identification of 15- to 17-kilodalton antigens associated with virulent Rhodococcus equi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29(3):439-443. <PMid:2037660>, Tan et al. 1995Tan C., Prescott J.F., Patterson M.C. & Nicholson V.M. 1995. Molecular characterization of a lipid-modified virulence-associated protein of Rhodococcus equi and its potential in protective immunity. Can. J. Vet. Res. 59(1):51-59. <PMid:7704843>, Monego et al. 2009Monego F., Maboni F., Krewer C., Vargas A., Costa M. & Loreto E. 2009. Molecular characterization of Rhodococcus equi from horse-breeding farms by means of multiplex PCR for the vap gene family. Curr. Microbiol. 58(4):399-403. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00284-009-9370-6> <PMid:19205798>

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-009-9370-...

). Secondary and immunosuppressive conditions can interact in the pathogenesis of the disease in foals. Pulmonary infection by the fungus Pneumocystis is sometimes seen in association to R. equi infection in foals (Ainsworth et al. 1993Ainsworth D.M., Weldon A.D., Beck K.A. & Rowland P.H. 1993. Recognition of Pneumocystis carinii in foals with respiratory distress. Equine Vet. J. 25(2):103-108. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993.tb02917.x> <PMid:8467767>

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993...

, Perron Lepage et al. 1999Perron Lepage M.F., Gerber V. & Suter M.M. 1999. A case of interstitial pneumonia associated with Pneumocystis carinii in a foal. Vet. Pathol. 36(6):621-624. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1354/vp.36-6-621> <PMid:10568448>

https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.36-6-621...

).

The main clinical and pathological feature in foals with Rhodococcus equi infection is severe pyogranulomatous pneumonia, frequently accompanied by ulcerative enterocolitis and mesenteric lymphadenitis (Zink et al. 1986Zink M.C., Yager J.A. & Smart N.L. 1986. Corynebacterium equi infections in horses, 1958-1984: a review of 131 cases. Can. Vet. J. 27(5):213-217. <PMid:17422658>

https://doi.org/17422658...

, Caswell & Williams 2016Caswell J.L. & Williams K.J. 2016. Respiratory system, p.569-571. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00011-5>

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318...

). Furthermore, the infection can lead to arthritis, osteomyelitis, hepatic, splenic or skin abscesses, hypopyon, ulcerative lymphangitis, methritis, and abortion in horses (Zink et al. 1986Zink M.C., Yager J.A. & Smart N.L. 1986. Corynebacterium equi infections in horses, 1958-1984: a review of 131 cases. Can. Vet. J. 27(5):213-217. <PMid:17422658>

https://doi.org/17422658...

, Szeredi et al. 2006Szeredi L., Molnár T., Glávits R., Takai S., Makrai L., Dénes B. & Del Piero F. 2006. Two cases of equine abortion caused by Rhodococcus equi. Vet. Pathol. 43(2):208-211. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1354/vp.43-2-208> <PMid:16537942>

https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.43-2-208...

, Caswell & Williams 2016Caswell J.L. & Williams K.J. 2016. Respiratory system, p.569-571. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00011-5>

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318...

). Histologically, there are extensive areas of necrosis with abundant pyogranulomatous infiltrate and macrophages containing numerous intracytoplasmic cocobacillary bacteria (Johnson et al. 1983Johnson J.A., Prescott J.F. & Markham R.J. 1983. The pathology of experimental Corynebacterium equi infection in foals following intrabronchial challenge. Vet. Pathol. 20(4):440-449. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030098588302000407> <PMid:6623848>

https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985883020004...

, Caswell & Williams 2016Caswell J.L. & Williams K.J. 2016. Respiratory system, p.569-571. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00011-5>

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318...

). The aims of this study were (I) to describe the clinical and morphological findings of rhodococcosis in foals associated to the immunohistochemical detection of the organism; (II) determine the occurrence of pulmonary coinfection with Pneumocystis spp.

Materials and Methods

Twenty foals naturally infected by Rhodococcus equi were submitted to postmortem examination from 1997 to 2012. Referring veterinarians provided the clinical background. Samples of multiple organs were collected, fixed in 10% formalin, routinely processed for histology and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 3μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), Brown-Hopps method, and Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS). Fresh samples of the tissues containing lesions were submitted to bacteriological testing according to standard laboratory protocols (Quinn et al. 2011Quinn P.J., Markey B.K., Leonard F.C., FitzPatrick E.S., Fanning S. & Hartigan P.J. 2011. Rhodococcus equi, p.213-216. In: Ibid. (Eds), Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex.).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for R. equi was performed with a polyclonal antibody produced by inoculation of an ATCC strain of R. equi in rabbits, at a 1:50 dilution. The antigen retrieval was made by a citrate buffer solution at pH 6.0 for 3 cycles of 5 minutes in a microwave. For the Pneumocystis IHC the commercial antibody anti-Pneumocystis jirovecii (carinii) (3F6): sc-57980 (Santa Cruz Biotecnology®) at a 1:1,000 dilution was used. The antigen retrieval was made by a 0.1% dilution of trypsin for over 15 minutes at 37oC, followed by a citrate buffer solution at pH 6.0 for 40 minutes at 96oC. Afterward, for both techniques, staining was obtained by the streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique, using 3.3-diaminobenzidine for R. equi IHC and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole for P. jirovecii (carinii) (3F6).

Results

History and clinical features

The foals submitted to necropsy belonged to four different horse-breeding farms from Porto Alegre, Brazil. Seventeen out of 20 cases were from a single farm, with history of approximately eight deaths/year attributed to Rhodococcus equi infection. The affected foals were of different ages, varying from 30 to 95 days (average 60 days), belonging to different breeds, such as Brazilian Sport Horse (6/20), Holsteiner (6/20), American Quarter Horse (2/20), Brazilian Saddle Horse (1/20), unknown (5/20). No difference in sex was observed (10 females and 10 males). Clinical history was of respiratory signs, such as nasal discharge, cough and dyspnea (11/20); as well as hyperthermia (10/20); prostration (4/20); articular swelling (6/20); locomotor disorders, such as lameness, hindlimb paresis or paralysis (3/20), opacity of the anterior eye chamber (2/20); hyphema (2/20); diarrhea (3/20); and two foals had no clinical signs. The foal’s clinical picture is described in Table 1.

Necropsy findings

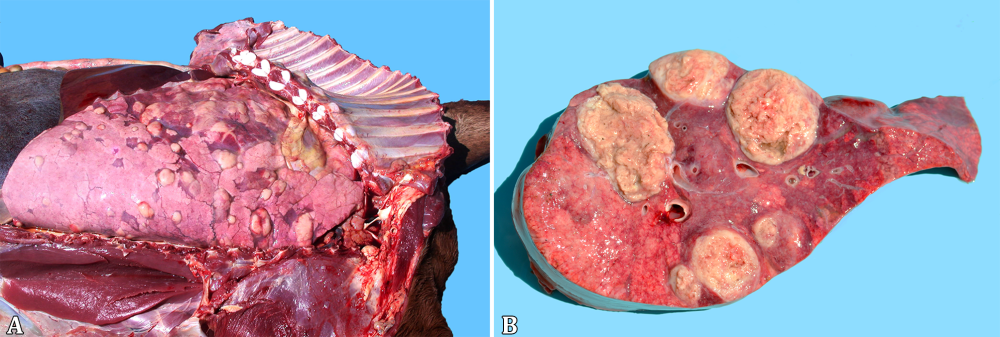

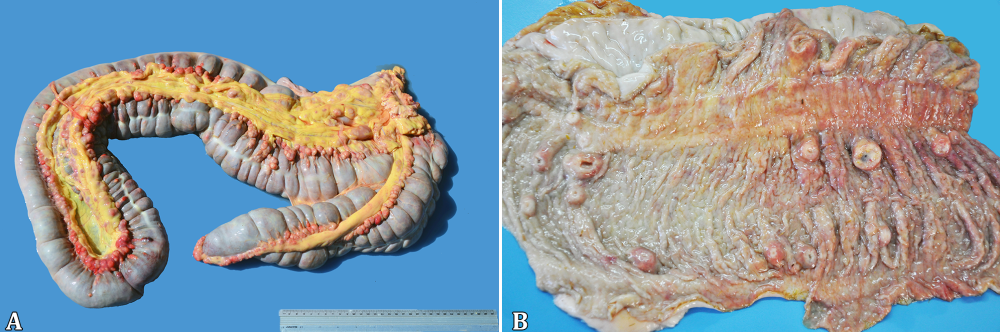

At necropsy, the foals’ body condition ranged from good or fair (17/20) to poor (3/20) (Table 2). Pulmonary lesions were seen in the majority of the cases (19/20) and consisted of multifocal to coalescing nodules ranging from a few millimeters up to 10cm in diameter (Fig.1A), containing a yellowish white creamy material (Fig.1B), accompanied by cranioventral consolidation in some foals. The lungs were also diffusely non-collapsed with rib impressions and elastic consistency in one foal (1/20). Other respiratory lesions included guttural pouch empyema (1/20), guttural pouch tympany (1/20), fibrinosuppurative pleuritis (1/20), pneumothorax associated with pleural bullous emphysema (1/20) and ulcerative tracheitis (1/20). One-half of the foals presented lymphadenitis (10/20), eight of them involving the mesenteric, colonic (Fig.2A) and/or gastric lymph nodes and five implicating the tracheobronchial ones. Ulcerative typhlocolitis (Fig.2B) was observed in five cases. One case presented ulcerative enteritis of the distal segment of the jejunum and ileum and one had acute fibrinonecrotic enterocolitis. Two foals had thickened lymphatic vessels on the colonic serosa; one case had jejunoileal intussusception and one additional case had an inguinal hernia containing a 15cm long segment of the jejunum. Fibrinous peritonitis and ascites have been seen in one case each. Swollen joints containing abundant aqueous synovial fluid or hemorrhagic content were seen in the tibiotarsal, femorotibiopatellar or carpal joints (5/20). Alternatively, a fibrous thickening of the tarsal joint capsule, with a caseous exudate draining through a fistula was seen in one case (1/20, Fig.3A). Three foals (3/20) had bone lesions; one foal presented a purulent nodule with a complete destruction of the body of the second lumbar vertebra (Fig.3B), resulting in the compression of the spinal cord; one case consisted of an encapsulated nodule filled with a purulent exudate measuring 20cm on the left wing of the atlas; and the last one had a purulent mass on the costochondral junction of the third left rib. One foal presented a retromandibular fluctuating mass, measuring approximately 20cm in diameter, corresponding to an abscess involving the first cervical vertebra. The eyes were affected in four foals, with hypopyon (2/20) or hyphema (2/20). Additionally, there was one case with disseminated hemorrhages, involving different organs, including the subcutaneous tissue, skeletal muscles, lungs, urinary bladder and the already mentioned anterior chamber of the eye and a tarsal joint. There was also concurrent fibrinonecrotic esophagitis (2/20) with similar lesions in the nonglandular portion of the stomach in one of the foals, affecting the tongue and trachea in the other.

Lungs of Rhodococcus equi naturally infected foals. (A) Multifocal to coalescing lung nodules, and (B) containing a yellowish white creamy material, seen at the cut surface.

Rhodococcus equi naturally infected foals. (A) Lymphadenitis involving the colonic lymph nodes. (B) Ulcerative typhlocolitis with umbilicated nodules on the mucosa.

Rhodococcus equi naturally infected foals. (A) Swollen tibiotarsal joint with an inspissated exudate draining through a fistula. (B) Destruction of the body of the second lumbar vertebra.

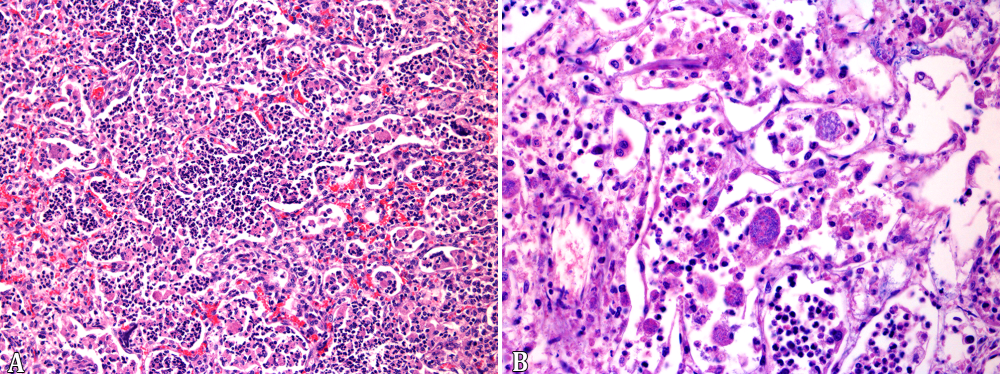

Histopathological findings

In the 19 foals with pulmonary gross lesions, there was multifocal inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils, macrophages and multinucleated giant cells filling the alveolar spaces and bronchioles (Fig.4A), associated with extensive necrosis of the pulmonary parenchyma. The macrophages occasionally contained myriads of cocobacillary basophilic bacteria (Fig.4B), which stained gram-positive with Brown-Hopps technique. The inflammatory infiltrate was sometimes delimitated by a fibrous capsule and also interspersed between the nodules. The alveolar capillaries had large amounts of neutrophils and multifocal thrombosis. There was also interstitial and alveolar edema, sometimes with abundant fibrin deposition. In five cases there was simultaneous interstitial pneumonia, characterized by alveolar walls thickening, due to either proliferation of type 2 pneumocytes as well as mononuclear cells infiltration. In one case, associated with the interstitial lesion, mineralization of the alveolar walls, arterial tunica media, as well as the endocardium was observed. In ten cases, marked pyogranulomatous infiltrate, sometimes containing bacterial laden macrophages was observed in the lymph nodes. Pyogranulomatous infiltrate in the lymphatic aggregates of the large intestine with superficial mucosal ulceration was seen in five cases, eventually accompanied by pyogranulomatous lymphangitis. Fibrinonecrotic enterocolitis with coccobacillary bacteria on the mucosal surface was seen in one case. Three foals had pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis with severe destruction of the bone matrix, involving a cervical and a lumbar vertebra, and a rib of each foal. One case presented pyogranulomatous and fibrosing arthritis of the tarsal joint, one had lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic articular infiltrate, and four other cases had lymphoplasmacytic arthritis, with severe hemarthrosis in one of them. There were two cases of hypopyon, with marked fibrinous exudate in the anterior eye chamber and two cases of hyphema. In the trachea of one foal, there was a multifocal submucosal pyogranulomatous infiltrate with ulceration of the mucosa. The cases with ulcerative esophagitis, gastritis or tracheitis had multifocal extensive areas of superficial necrosis with neutrophilic infiltrate, interspersed with numerous Grocott positive yeasts and pseudohyphae, compatible with Candida spp.

Rhodococcus equi naturally infected foals. (A) Neutrophils, macrophages, and eventual multinucleated giant cells filling the alveolar spaces and bronchioles. HE, obj.20x. (B) Macrophages expanded by myriads of cocobacillary basophilic bacteria. HE, obj.40x.

Microbiological tests

Out of the 20 cases, 15 resulted in the isolation of pure cultures of R. equi of the lesions. In two foals there was also isolation of Salmonella sp. from the intestines. The two cases of ulcerative esophagitis resulted in Candida albicans isolation from the esophageal samples.

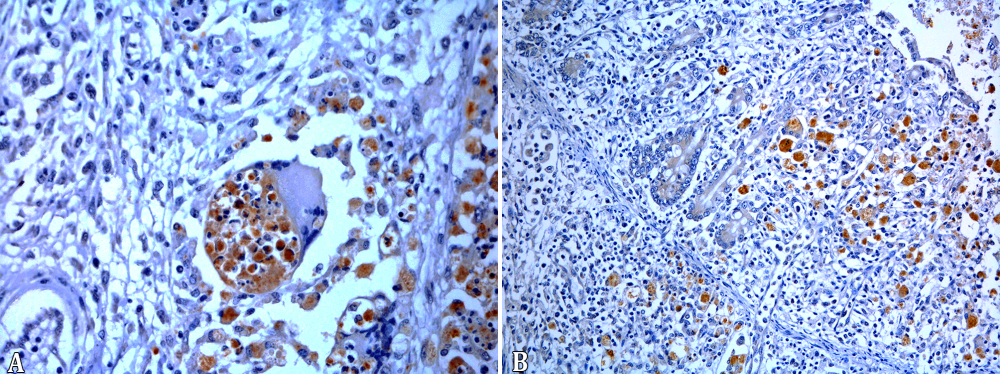

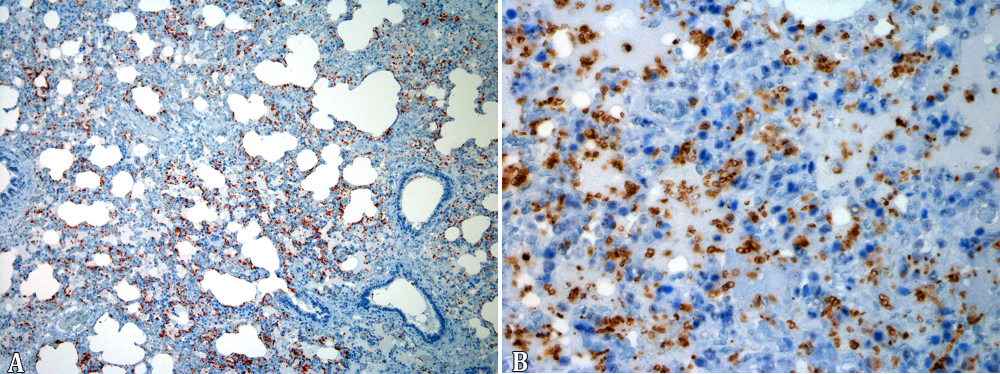

Immunohistochemistry

The 19 cases of pyogranulomatous pneumonia the intracytoplasmic bacteria seen in the intralesional macrophages were positive for R. equi in the IHC test. In addition, the bones of the 3 foals with osteomyelitis as well as the tarsal joint, tracheal and intestinal lesions of all horses with extra-pulmonary pyogranulomatous lesions were positive for R. equi (Fig.5A,B). The synovial membranes of four foals with lymphoplasmacytic arthritis and the foal with lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic arthritis were all negative. The IHC for Pneumocystis revealed 13 positive cases for the fungus, two with large amounts of the microorganism, either free in alveolar spaces or in the cytoplasm of alveolar macrophages (Table 3, Fig.6A,B).

(A) Immunolabeled Rhodococcus equi in the cytoplasm of intralesional macrophages in pyogranulomatous pneumonia. Streptavidin-peroxidase, chromogen 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB), obj.40x. (B) Immunolabeled Rhodococcus equi in intestinal lesions of naturally infected foals. Streptavidin-peroxidase, chromogen 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB), obj.20x.

(A-B) Large amounts of the Pneumocystis sp., are seen free in alveolar spaces and in the cytoplasm of alveolar macrophages of foals naturally infected by Rhodococcus equi. Primary antibody Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii) (3F6). Streptavidin-peroxidase, chromogen 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC), obj.10x and obj.40x.

Discussion

The clinical and pathological findings described herein reinforce Rhodococcus equi as an important horse pathogen, supporting studies of other countries (Zink et al. 1986Zink M.C., Yager J.A. & Smart N.L. 1986. Corynebacterium equi infections in horses, 1958-1984: a review of 131 cases. Can. Vet. J. 27(5):213-217. <PMid:17422658>

https://doi.org/17422658...

, Giguère & Prescott 1997Giguère S. & Prescott J.F. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):313-334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0> <PMid:9226845>

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00...

, Sönmez & Gürel 2013Sönmez K. & Gürel A. 2013. Histopathological alterations and immunohistochemistry in tissue samples from horses suspected of Rhodococcus equi infection. Revue Méd. Vét. 164(2):80-84.). In our cases, all foals came from horse-breeding farms; even though extensively raised workhorses are abundant in the State of Rio Grande do Sul (Costa et al. 2014Costa E., Diehl G.N., Santos D.V. & Silva A.P.S.P. 2014. Panorama da equinocultura no Rio Grande do Sul. Informativo Técnico nº 5. Departamento de Defesa Animal do Rio Grande do Sul, Secretaria Estadual de Agricultura, Pecuária e Agronegócio, Governo do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS. 9p.), indicating that a high populational density can be, indeed, a determinant factor for the occurrence of the disease. An epidemiological study was however not performed to determine the disease prevalence in different types of production.

Pyogranulomatous pneumonia was the most common, single or combined finding, seen in 95% of the examined foals, highlighting the importance of the airborne way of infection. The only case with no respiratory lesions presented osteoarticular infection affecting the first cervical vertebra and the right tarsal joint. This singular case points to alternative routes of dissemination, such as hematogenic spreading (Giguère & Prescott 1997Giguère S. & Prescott J.F. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):313-334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0> <PMid:9226845>

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00...

). The most common lesions, in addition to the pulmonary presentation, consist of pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis and pyogranulomatous and ulcerative enterocolitis, seen respectively in 50% and 25% of the cases, similar to other reports described in the literature (Zink et al. 1986Zink M.C., Yager J.A. & Smart N.L. 1986. Corynebacterium equi infections in horses, 1958-1984: a review of 131 cases. Can. Vet. J. 27(5):213-217. <PMid:17422658>

https://doi.org/17422658...

, Caswell & Williams 2016Caswell J.L. & Williams K.J. 2016. Respiratory system, p.569-571. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00011-5>

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318...

). The articular infiltrate was lymphoplasmacytic (20%), lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic (5%) or pyogranulomatous (5%). Just in the case with pyogranulomatous infiltrate, microbiology and immunohistochemistry tests allowed the detection of R. equi. Lymphoplasmacytic arthritis is thought to be an immune-mediated reaction (Sweeney et al. 1987Sweeney C.R., Sweeney R.W. & Divers T.J. 1987. Rhodococcus equi pneumonia in 48 foals: response to antimicrobial therapy. Vet. Microbiol. 14(3):329-336. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)90120-9> <PMid:3672875>

https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)901...

, Giguère & Prescott 1997Giguère S. & Prescott J.F. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):313-334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0> <PMid:9226845>

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00...

), reinforced by the fact that none of the samples yielded bacterial growth nor immunohistochemical expression for R. equi at the lesion site. Vertebral bodies are other important sites of infection, resulting in compression of the spinal cord due to a compressive myelopathy, which led to locomotor impairment in one foal. The lack of evident clinical signs in spite of the severity of the lesions in many cases could be explained by the slow progression of the pulmonary lesions, combined to the remarkable capacity of the foal to compensate the progressive loss of viable lung (Giguère & Prescott 1997Giguère S. & Prescott J.F. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):313-334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0> <PMid:9226845>

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00...

). The organism was detected in 100% of the cases by immunohistochemistry. This method is known to be a valuable tool in the routine detection of R. equi infection (Madarame et al. 1996Madarame H., Takai S., Morisawa N., Fujii M., Hidaka D., Tsubaki S. & Hasegawa Y. 1996. Immunohistochemical detection of virulence-associated antigens of Rhodococcus equi in pulmonary lesions of foal. Vet. Pathol. 33(3):341-343. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030098589603300312> <PMid:8740709>

https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985896033003...

, Mariotti et al. 2000Mariotti F., Cuteri V., Takai S., Renzoni G., Pascucci L. & Vitellozzi G. 2000. Imunohistochemical detection of virulence-associated Rhodococcus equi antigens in pulmonary and intestinal lesions in horses. J. Comp. Pathol. 123(2/3):186-189. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jcpa.2000.0392> <PMid:11032673>

https://doi.org/10.1053/jcpa.2000.0392...

, Sönmez & Gürel 2013Sönmez K. & Gürel A. 2013. Histopathological alterations and immunohistochemistry in tissue samples from horses suspected of Rhodococcus equi infection. Revue Méd. Vét. 164(2):80-84.).

Pulmonary infection with Pneumocystis revealed to be frequently associated with Rhodococcus equi infection in foals, with 65% of the lungs being positive in the immunohistochemical test, even in a case with no pulmonary pyogranulomatous lesion. Lung infection with Pneumocystis is thought to be an opportunistic condition in horses, similarly to what is observed in humans with Immunodeficiency Virus infection and in pigs with Porcine Circovirus type 2 infection (Cavallini Sanches et al. 2006Cavallini Sanches E.M., Borba M.R., Spanamberg A., Pescador C., Corbellini L.G., Ravazzolo A.P., Driemeier D. & Ferreiro L 2006. Co-infection of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis and porcine circovirus-2 (PCV2) in pig lungs obtained from slaughterhouses in Southern and Midwestern regions of Brazil. J. Eukaryot Microbiol. 53(Suppl.1):S92-S94. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00185.x> <PMid:17169081>

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006...

, Ueno et al. 2014Ueno T., Niwa H., Kinoshita Y., Katayama Y. & Hobo S. 2014. Pneumocystis pneumonia in a Thoroughbred Racehorse. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 34(2):333-336. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.07.004>

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.07.0...

). However, it is important to emphasize that only four of the 13 foals with Pneumocystis infection had histologic evidence of interstitial pneumonia. Similarly, in pigs slaughtered in Brazil, pulmonary infection by Pneumocystis spp. is not associated with interstitial pneumonia in a large proportion of the cases (Cavallini Sanches et al. 2007Cavallini Sanches E.M., Pescador C., Rozza D., Spanamberg A., Borba M.R., Ravazzolo A.P., Driemeier D., Guillot J. & Ferreiro L. 2007. Detection of Pneumocystis spp. in lung samples from pigs in Brazil. Med. Mycol. 45(5):395-399. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13693780701385876> <PMid:17654265>

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369378070138587...

). In our study immunohistochemistry was performed with a monoclonal antibody against Pneumocystis jirovecii from human lung; however a molecular investigation was not accomplished to determine the specific identity of the organism. In one case of Pneumocystis infection in a foal, the organism found revealed to be distantly related to the organism that infects humans, but close to the Pneumocystis spp. found in other hosts (Ueno et al. 2014Ueno T., Niwa H., Kinoshita Y., Katayama Y. & Hobo S. 2014. Pneumocystis pneumonia in a Thoroughbred Racehorse. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 34(2):333-336. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.07.004>

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.07.0...

).

Other concurrent infections observed in this study were, for example, candidiasis of the superior digestive tract (2/20) and enteric infection with Salmonella sp. (2/20). One of the cases with Salmonella sp. infection had a fibrinonecrotic enterocolitis, typical of salmonellosis in horses (Traub-Dargatz & Besser 2007Traub-Dargatz J.L. & Besser T.E. 2007. Salmonellosis, p.331-345. In: Sellon D.C. & Long M.T. (Eds), Equine Infectious Diseases. Saunders Elsevier, Saint Louis . <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406-4.50043-0>.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406...

, Juffo et al. 2016Juffo G.D., Bassuino D.M., Gomes D.C., Wurster F., Pissetti C., Pavarini S.P. & Driemeier D. 2016. Equine salmonellosis in southern Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49(3):475-482. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-1> <PMid:28013440>

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-...

) and the other case had a pyogranulomatous and ulcerative colitis, similar to the enteric lesions due to R. equi infection (Traub-Dargatz & Besser 2007Traub-Dargatz J.L. & Besser T.E. 2007. Salmonellosis, p.331-345. In: Sellon D.C. & Long M.T. (Eds), Equine Infectious Diseases. Saunders Elsevier, Saint Louis . <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406-4.50043-0>.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406...

). Concomitant infections with microorganisms are considered opportunistic and could be attributed to an imbalance in the digestive tract microbiota secondary to antibiotic or anti-inflammatory therapy as well as environmental stress factors (Traub-Dargatz & Besser 2007Traub-Dargatz J.L. & Besser T.E. 2007. Salmonellosis, p.331-345. In: Sellon D.C. & Long M.T. (Eds), Equine Infectious Diseases. Saunders Elsevier, Saint Louis . <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406-4.50043-0>.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406...

, Uzal et al. 2016Uzal F.A., Plattner B.L. & Hostetter J.N. 2016. Alimentary system, p.158-244. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00007-3>.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318...

, Juffo et al. 2016Juffo G.D., Bassuino D.M., Gomes D.C., Wurster F., Pissetti C., Pavarini S.P. & Driemeier D. 2016. Equine salmonellosis in southern Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49(3):475-482. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-1> <PMid:28013440>

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-...

).

Hemorrhagic diathesis (1/20) and soft tissue mineralization (1/20) were also present. The first condition presented as a systemic hemorrhage, involving the musculoskeletal system, eyes, as well as the lungs and urinary bladder. Although the macroscopic picture could suggest purpura, which is a possible complication of Rhodococcus equi infection in foals, the lack of microscopic evidence of vascular necrosis ruled out the diagnosis (Pusterla et al. 2003Pusterla N., Watson J.L., Affolter V.K., Magdesian K.G., Wilson W.D. & Carlson G.P. 2003. Purpura haemorrhagica in 53 horses. Vet. Rec. 153(4):118-121. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.153.4.118> <PMid:12918829>

https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.153.4.118...

). Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is another hypothesis since it has been seen in foals intratracheally inoculated with R. equi. Albeit the authors of this experiment considered unlikely that sepsis due to R. equi could lead to DIC (Johnson et al. 1983Johnson J.A., Prescott J.F. & Markham R.J. 1983. The pathology of experimental Corynebacterium equi infection in foals following intrabronchial challenge. Vet. Pathol. 20(4):440-449. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030098588302000407> <PMid:6623848>

https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985883020004...

). The pathogenesis involving the pulmonary, epicardial, and endocardial mineralization seen in one foal remains speculative, but this finding could be attributed to hypercalcemia, a consequence of an upregulated production of activated vitamin D3 by macrophages in granulomatous diseases, as demonstrated in bovine paratuberculosis (Driemeier et al. 1999Driemeier D., Cruz C.E.F., Gomes M.J.P., Corbellini L.G., Loretti A.P. & Colodel E.M. 1999. Aspectos clínicos e patológicos da paratuberculose em bovinos no Rio Grande do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 19(3/4):109-115. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X1999000300004>

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X199900...

). Diffuse pulmonary mineralization has also been seen in cases of salmonellosis in foals (Juffo et al. 2016Juffo G.D., Bassuino D.M., Gomes D.C., Wurster F., Pissetti C., Pavarini S.P. & Driemeier D. 2016. Equine salmonellosis in southern Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49(3):475-482. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-1> <PMid:28013440>

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-...

).

Conclusions

Rhodococcus equi infection is an important sanitary problem of foals in our region, due to the severity of the lesions involving the respiratory and alimentary systems, as well as the locomotor apparatus.

Immuno-histochemistry was an important tool to reach the detection of R. equi infection and helped to elucidate the pathogenesis of different lesions, such as septic or immune-mediated arthritis.

Furthermore, infection with Pneumocystis shows to be frequent in foals infected with R. equi in the laboratory’s range.

Acknowledgments

We thank CNPq and CAPES for financial support and our colleagues and professors for their technical support.

References

- Ainsworth D.M., Weldon A.D., Beck K.A. & Rowland P.H. 1993. Recognition of Pneumocystis carinii in foals with respiratory distress. Equine Vet. J. 25(2):103-108. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993.tb02917.x> <PMid:8467767>

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993.tb02917.x - Caswell J.L. & Williams K.J. 2016. Respiratory system, p.569-571. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00011-5>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00011-5 - Cavallini Sanches E.M., Borba M.R., Spanamberg A., Pescador C., Corbellini L.G., Ravazzolo A.P., Driemeier D. & Ferreiro L 2006. Co-infection of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis and porcine circovirus-2 (PCV2) in pig lungs obtained from slaughterhouses in Southern and Midwestern regions of Brazil. J. Eukaryot Microbiol. 53(Suppl.1):S92-S94. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00185.x> <PMid:17169081>

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00185.x - Cavallini Sanches E.M., Pescador C., Rozza D., Spanamberg A., Borba M.R., Ravazzolo A.P., Driemeier D., Guillot J. & Ferreiro L. 2007. Detection of Pneumocystis spp. in lung samples from pigs in Brazil. Med. Mycol. 45(5):395-399. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13693780701385876> <PMid:17654265>

» https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780701385876 - Costa E., Diehl G.N., Santos D.V. & Silva A.P.S.P. 2014. Panorama da equinocultura no Rio Grande do Sul. Informativo Técnico nº 5. Departamento de Defesa Animal do Rio Grande do Sul, Secretaria Estadual de Agricultura, Pecuária e Agronegócio, Governo do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS. 9p.

- Driemeier D., Cruz C.E.F., Gomes M.J.P., Corbellini L.G., Loretti A.P. & Colodel E.M. 1999. Aspectos clínicos e patológicos da paratuberculose em bovinos no Rio Grande do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 19(3/4):109-115. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X1999000300004>

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X1999000300004 - Giguère S. & Prescott J.F. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):313-334. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0> <PMid:9226845>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00099-0 - Johnson J.A., Prescott J.F. & Markham R.J. 1983. The pathology of experimental Corynebacterium equi infection in foals following intrabronchial challenge. Vet. Pathol. 20(4):440-449. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030098588302000407> <PMid:6623848>

» https://doi.org/10.1177/030098588302000407 - Juffo G.D., Bassuino D.M., Gomes D.C., Wurster F., Pissetti C., Pavarini S.P. & Driemeier D. 2016. Equine salmonellosis in southern Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49(3):475-482. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-1> <PMid:28013440>

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1216-1 - Madarame H., Takai S., Morisawa N., Fujii M., Hidaka D., Tsubaki S. & Hasegawa Y. 1996. Immunohistochemical detection of virulence-associated antigens of Rhodococcus equi in pulmonary lesions of foal. Vet. Pathol. 33(3):341-343. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030098589603300312> <PMid:8740709>

» https://doi.org/10.1177/030098589603300312 - Mariotti F., Cuteri V., Takai S., Renzoni G., Pascucci L. & Vitellozzi G. 2000. Imunohistochemical detection of virulence-associated Rhodococcus equi antigens in pulmonary and intestinal lesions in horses. J. Comp. Pathol. 123(2/3):186-189. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jcpa.2000.0392> <PMid:11032673>

» https://doi.org/10.1053/jcpa.2000.0392 - Meijer W.G. & Prescott J.F. 2004. Rhodococcus equi. Vet. Res. 35(4):383-396. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2004024> <PMid:15236672>

» https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2004024 - Monego F., Maboni F., Krewer C., Vargas A., Costa M. & Loreto E. 2009. Molecular characterization of Rhodococcus equi from horse-breeding farms by means of multiplex PCR for the vap gene family. Curr. Microbiol. 58(4):399-403. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00284-009-9370-6> <PMid:19205798>

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-009-9370-6 - Perron Lepage M.F., Gerber V. & Suter M.M. 1999. A case of interstitial pneumonia associated with Pneumocystis carinii in a foal. Vet. Pathol. 36(6):621-624. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1354/vp.36-6-621> <PMid:10568448>

» https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.36-6-621 - Prescott J.F. 1987. Epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi infection in horses. Vet. Microbiol. 14(3):211-214. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)90107-6> <PMid:3314106>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)90107-6 - Prescott J.F. 1991. Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4(1):20-34. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.4.1.20> <PMid:2004346>

» https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.4.1.20 - Pusterla N., Watson J.L., Affolter V.K., Magdesian K.G., Wilson W.D. & Carlson G.P. 2003. Purpura haemorrhagica in 53 horses. Vet. Rec. 153(4):118-121. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.153.4.118> <PMid:12918829>

» https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.153.4.118 - Quinn P.J., Markey B.K., Leonard F.C., FitzPatrick E.S., Fanning S. & Hartigan P.J. 2011. Rhodococcus equi, p.213-216. In: Ibid. (Eds), Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex.

- Sönmez K. & Gürel A. 2013. Histopathological alterations and immunohistochemistry in tissue samples from horses suspected of Rhodococcus equi infection. Revue Méd. Vét. 164(2):80-84.

- Sweeney C.R., Sweeney R.W. & Divers T.J. 1987. Rhodococcus equi pneumonia in 48 foals: response to antimicrobial therapy. Vet. Microbiol. 14(3):329-336. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)90120-9> <PMid:3672875>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1135(87)90120-9 - Szeredi L., Molnár T., Glávits R., Takai S., Makrai L., Dénes B. & Del Piero F. 2006. Two cases of equine abortion caused by Rhodococcus equi Vet. Pathol. 43(2):208-211. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1354/vp.43-2-208> <PMid:16537942>

» https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.43-2-208 - Takai S. 1997. Epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi infections: a review. Vet. Microbiol. 56(3/4):167-176. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00085-0> <PMid:9226831>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00085-0 - Takai S., Koike K., Ohbushi S., Izumi C. & Tsubaki S. 1991. Identification of 15- to 17-kilodalton antigens associated with virulent Rhodococcus equi J. Clin. Microbiol. 29(3):439-443. <PMid:2037660>

- Tan C., Prescott J.F., Patterson M.C. & Nicholson V.M. 1995. Molecular characterization of a lipid-modified virulence-associated protein of Rhodococcus equi and its potential in protective immunity. Can. J. Vet. Res. 59(1):51-59. <PMid:7704843>

- Traub-Dargatz J.L. & Besser T.E. 2007. Salmonellosis, p.331-345. In: Sellon D.C. & Long M.T. (Eds), Equine Infectious Diseases. Saunders Elsevier, Saint Louis . <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406-4.50043-0>.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2406-4.50043-0 - Ueno T., Niwa H., Kinoshita Y., Katayama Y. & Hobo S. 2014. Pneumocystis pneumonia in a Thoroughbred Racehorse. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 34(2):333-336. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.07.004>

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.07.004 - Uzal F.A., Plattner B.L. & Hostetter J.N. 2016. Alimentary system, p.158-244. In: Maxie M.G. (Ed.), Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol.2. 6th ed. Elsevier, Saint Louis. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00007-3>.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-5318-4.00007-3 - Zink M.C., Yager J.A. & Smart N.L. 1986. Corynebacterium equi infections in horses, 1958-1984: a review of 131 cases. Can. Vet. J. 27(5):213-217. <PMid:17422658>

» https://doi.org/17422658

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

02 Dec 2019 -

Date of issue

Nov 2019

History

-

Received

05 Mar 2019 -

Accepted

12 Mar 2019