Abstracts

The United States has been a nation of immigrants, which is reflected by its multicultural society. Different immigrant groups helped shape the American society through their cultures and traditions. One group was the Germans; they represented a unique and forceful current in the stream of immigration to the United States. In their cultural luggage the German immigrant brought their physical culture to North America, Turnen which was organised in clubs or so-called Turnvereine. The American turner movement has its origin in the mid 19th century, and it is still organised on a national level, since the 1930s under the name American Turners. This article summarises the history of the German-American turner movement until the 1990s, and will also relate to various stages of Americanization within this movement.

Turnen; Turner society; Germans; German-Americans

Os Estados Unidos se constituíram como uma nação de imigrantes, portanto, uma sociedade multicultural. Diferentes grupos de imigrantes ajudaram a moldar a sociedade americana através de suas culturas e tradições. Um destes grupos foi o dos alemães, que representou uma corrente singular e muito forte no fluxo imigratório para os Estados Unidos. Em sua bagagem cultural os imigrantes alemães levaram sua cultura física para a América do Norte: o Turnen, que era organizado em clubes ou nas denominadas Turnvereine. O movimento dos Turner americanos tem suas origens em meados do século XIX e ainda apresenta uma organização em nível nacional sob o nome American Turners, adotado desde a década de 1930. Este artigo resume a história do movimento do Turnen teuto-americano até os anos de 1990 e relata as diferentes etapas de sua americanização.

Turnen ; Sociedade Turner; Alemães; Alemães-americanos

Los Estados Unidos se constituyeron como una nación de inmigrantes, lo que serefleja actualmente en su sociedad multicultural. Diferentes grupos de inmigrantes ayudarona dar forma a una sociedad americana a través de sus culturas y tradiciones. Uno de estosgrupos fueron los alemanes, que representaron una corriente singular y muy fuerte en el flujoinmigratorio para los Estados Unidos. En su bagaje cultural los inmigrantes alemanes llevaronsu cultura física para Amércia del Norte: el Turnen, que era organizado en clubes o en las deno-minadas Turnvereine. El movimiento de los Turner americanos tiene sus orígenes a mediados delsiglo XIX y todavía presenta una organización a nivel nacional bajo el nombre American Turners,adoptado desde la década de 1930. Este artículo resume la histórica del movimiento del Turnenteuto-americano hasta los a˜nos de 1990 y relata las diferentes etapas de su americanización.

Turnen; Sociedad Turner; Alemanes; Alemanes-americanos

Introduction

Until recently the United States has been a nation of immigrants, which is reflected today by a multicultural society. Different immigrant groups from all over the world helped shape American society through their cultures and traditions. One of the biggest immigrant groups is the German-Americans, who, according to the 1990 census, are, with over 20%, the largest ethnic group in the United States (Adams, 1993Adams WP. The German Americans: an ethnic experience. Indianapolis: Max Kade German American Center, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis; 1993., p. 3). The culture and traditions which the German immigrants brought to the American continent took on new forms of expression in the new environment: German-American ones. Some have become part of the American mainstream culture and are not recognisable as German in origin.

German customs, rituals and cultural practices were perpetuated in the many societies or "Vereine" which the Germans organised in the United States. The contents often were altered to adapt to the new needs of the host society. The Vereine not only transmitted a kind of security to the immigrants, but also created group solidarity.1 1 See Hobsbawm (1985, p. 12). Historian Kathleen Neils Conzen describes them as "nurseries of ethnicities" in which German culture could spread and thus help form an ethnic culture and identity.2 2 See Luebke (1974, p. 43); Conzen (1989, p. 50; 58). The German-American directory of addresses listed 6586 German secular societies in the United States in 1916/17. At the end of the 1990s, in Chicago alone, there were still 80 German clubs in existence.3 3 Frankfurter Allgemeine, March 12th, 1998. Through such groups, German culture is preserved in the United States to a certain degree, as can be seen in the celebration of German festivities, such as the annual Oktoberfest, a Carnival or the German Day. These events mostly take place in cities with formerly huge German immigrant populations. They are organised by the German clubs of these towns.

Among the numerous community institutions and societies founded by the Germans are the Turner societies (Turnvereine), which were organisations for the development of physical education, and outlets for German immigrants to continue their cultural traditions. Their Turner Halls provided a social centre with lectures and libraries.

To this day over 700 Turner societies have once existed in the United States. Hardly anyone knows that some Turnvereine are still in existence. This paper shall provide an insight on how and why the Turners first came to the United States and into the history of the German-American Turner movement. It will also show how the German-American Turner movement is presently structured. A special focus will be put on the Americanization of the Turners into American Turners.

The beginnings of Turnen in Germany

The Turner movement has its origins in 18th- and 19th-century Germany and was closely connected with intellectual streams and the political, social and economic changes of the period such as the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, the new political order in Europe and technical advancement. In this context ideas about the education of the people, in which national unity, patriotism and the readiness to fight for one's "fatherland" played a special role, rose. German Turnen, largely developed by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778–1852), was such an idea.4 4 On Turnen see for example the contributions Stump and Ueberhorst (1980, p. 215-229); Pfister, (1996, p. 14-36) and the special edition of Sportwissenschaft 2 (2000). A good overview ofthe history of Turnen and sport is also given in Krüger (1993). The goals of the Turners were the liberation from French occupation, which followed the defeat of the Prussian army in the Napoleonic Wars, the overthrow of the feudal order and an end to the division of Germany into many small states in favour of a one-nation state. Thus, the Turners played an important role in the German nationalist movement and in the wars of liberation; many participated actively in the fight against the French occupying forces.

Turnen was introduced by Jahn as a comprehensive term for physical exercises. It not only included exercises on apparatus, as developed by philanthropists such as Guts Muths but also games and so-called "exercises for the people" (volkstümliche Übungen) (like running, jumping, lifting and climbing as well as fencing, swimming and wrestling). Although some of the apparatus is still used in modern gymnastics and the "exercises for the people" show similarities with today's track-and-field disciplines, the norms and values, the intentions, principles and the contexts of Jahn's Turnen differ fundamentally from modern gymnastics and sport.

The cradle of Turnen was Berlin, where Jahn and his followers set up the first grounds for Turnen (Turnplatz) on the so-called Hasenheide in 1811, an area outside the city during those days. Today it is a park within Berlin. From there the Turner movement rapidly spread throughout the states of the German Confederation. These gymnastics grounds that soon spread became meeting points for young men, who wanted to participate in physical activities and games, celebrate festivities (Turnfeste) and go together on trips (Turnfahrten). And it was a place to discuss politics.

Initially, the Prussian authorities supported the Turner movement, in part because they hoped its gymnastics, which seemed to strengthen both body and mind of the young men, would be of great use in the wars of liberation. However, in 1819 during the era of restoration after Napoleon's defeat, Turnen was banned in Prussia since it was part of the nationalist movement, which was now considered a threat. Under the "Carlsbad Decrees" the German rulers were required to suppress any opposition movement whatsoever.5 5 The "Carlsbad Decrees" were measures agreed by the states ofthe German Confederation to suppress the liberal and democraticconstitutional movement as well as all strivings towards nationalunity. The Turners, too, along with nationalistic fraternities (Burschenschaften), were classed as forces of opposition since they were against German particularism and thus against the new political order of the German Confederation. In some German states, Turnplätze were closed and a period ensued in which Turnen was completely banned (Turnsperre). Jahn, accused of having links with persons suspected of disloyalty of the authorities and subversion, was arrested in July 1819 and incarcerated for five years (Hofmann and Pfister, 2004Hofmann A, Pfister G. Turnen - a forgotten movement culture. Its beginnings in Germany and diffusion in the United States. In: Hofmann A, editor. Turnen and sport. Transatlantic transfers. Münster: Waxmann; 2004. p. 11-24., p. 11–14).

During the ‘Ban of Turnen’ boys and young men could still participate in "gymnastics" at some schools and private institutions but it was only twenty years later that Turnen as a national movement experienced a revival. In 1842 its ban was officially lifted by a cabinet order and Turnen was accepted as "necessary and indispensable part of male education" in the curriculum of boys’ secondary schools in Prussia (Krüger, 1993Krüger M. Einführung in die Geschichte der Leibeserziehung und des Sports, vol. 2. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 1993., p. 73).

In Europe the 1840s was a decade in which liberal ideas and political agitation spread. In the German states, too, demands for political rights and national unity became louder, and it was in this period of awakening that the goals and ideas of the Turner experienced their revival – a period in which clubs and societies were founded with democratic structures, and in which Turner societies became centres of political discussions and activities. Also the various Turnfeste which were held in the 1840s offered a splendid opportunity to come together, exchange ideas and make plans. At the centre of these festivities were not only gymnastic competitions but also political discussions and declamations, which mostly ended with the demand for "freedom and equality".6 6 On the role of the Turners in the 1948/49 Revolution see, for example Neumann (1968) and Krüger (1996).

After the success of the liberal movement in the March Revolution of 1848, the Turners thought they could fulfil their dreams and goals. The concessions of the authorities and the call for a national assembly in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt seemed to have removed the barriers to form a liberal nation state. Because of this the political activities of the Turner clubs increased in the spring of 1848 and the Turner movement played an important role in the revolution of 1848/49, partly because the Turner societies had physically fit, disciplined and politically committed members. Jahn had already recommended replacing the mercenary army by a people's army. Now the attempts at arming the people were supported not only by a great majority of the Turner but also by a large part of the population. In many clubs Turner militia were established which stood partly for the maintenance of law and order and partly for the republican ideals and the constitution of the Reich (Neumann, 1968, p. 30–45Neumann H. Die deutsche Turnbewegung in der Revolution 1848/49 und in der amerikanischen Emigration. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 1968.).

However, in the summer of 1848, various crises, upheavals and armed conflicts weakened the revolutionary movement. The constitution of the Reich (Reichsverfassung), which was not proclaimed until March 1849, could not be put into effect without military force. Many Turners, defending the constitution with weapons, were involved in the fighting.

The attitudes of the Turners towards the revolution differed profoundly. Some were "mere Turners"; others were political activists. Karl Blind, a Turner from Mannheim, for example, emphasised in January of 1848: "Our purpose is revolution (…) Each Turner is a revolutionary", adding: "Even dagger, blood and poison should not be spared in the decisive moment" (Wieser, 1996Wieser L. 150 Jahre Turnen und Sport in Mannheim; 1996., p. 37). Especially the Turners in Baden and Wuerttemberg defended the ideals of the revolution: "Freedom, education and prosperity for the people" (Reppmann, 2003Reppmann J. Theodor Gülich aus Schleswig-Holstein in Amerika-Weltbürger, Turner und Revolutionar. In: Hofmann A, Krüger M, editors. Südwestdeutsche Turner in der Emigration. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 2003. p. 123-32.).

After the failure of the revolution, many Turners had to leave their home country because imprisonment or the death penalty awaited them. Thus, some emigrated to Switzerland, and some left from there to settle in England or the United States (Krüger, 1993Krüger M. Einführung in die Geschichte der Leibeserziehung und des Sports, vol. 2. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 1993., p. 36–97).

Cunz (1966, p. 11)Cunz D. They came from Germany. New York; 1966. refers to these individuals from the 1848 Revolution as a "new type" of German immigrant. As Barney stated in his description of the Forty-Eighters, they were different from earlier German immigrants because they possessed not only a classical education and had a strong interest in politics, but also because of their youthfulness7 7 Zucker points out in his description of 242 Forty-Eighters who left for the US that more than 60% were born in 1820 or later (1950, p. 270). and physical fitness gained from Turnen: "(…) in general being male, in his twenties, unmarried, in excellent physical condition through training in gymnastics, classically educated, politically enlightened and motivated, not without some economic means, and quite likely, disposed towards returning to Germany at a later time to support again the forces of revolution against the hated German princes and the influence of their corrupt power" (Barney, 1982Barney RK. Knights and exercise: German Forty Eighters and Turnvereine in the United States during the antebellum period. Can J Hist Sports 1982;2:62-79., p. 63f).

Transfer of German Turnen to the United States

The political refugees of the 1848 revolution in Germany were not the first persons who brought Turnen to the United States as part of their cultural luggage. Turnen had already been introduced to educational institutions in New England in the early 1820s by the German political exiles Karl Beck, Karl Follen and Franz Lieber, who had all been followers of Jahn (Geldbach, 1975Geldbach E. Die Verpflanzung des deutschen Turnens nach Amerika: Beck, Follen, Lieber. In: Stadion; 1975. p. 360-70., p. 341–342; p. 360–370). However, its success lasted only a few years. It was only a quarter of a century later – in 1848 – that the first Turner clubs or societies were founded in the United States by those Turners who had left Germany in the wake of the 1848 revolution which had brought a few thousand political refugees to the United States from Germany.8 8 It is almost impossible to arrive at an exact number of allthe ‘48ers’ who emigrated to the United States. Sources estimate that no more than 3000-4000 persons emigrated for purely politically reasons between 1847 and 1856 (see Rehe, 1996, p. 13-15; Reppmann, 1994, 12-13).

The political and social structures of the United States were completely different from those existing in Germany. It was a young nation, founded in 1776 with a democratic constitution. It was also a country of immigrants, even if with an Anglo-Saxon predominance. From the very beginning Turnen in the United States had a different fate than in Germany. On the one hand, it must be considered that Turnen was a physical culture of the Germans, transported to a country to which other immigrant groups had brought their systems of exercises and sport. On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that it was democratically and socialistically oriented Turners that had to emigrate, which is reflected in the political goals of the first American Turner societies and their umbrella organisation, the "Socialistische Turnerbund", founded officially in 1851. The Turner movement saw itself as a "nursery for all revolutionary ideas" which has their origins in a rational world view.9 9 See the Convention Protokoll of the Socialistische Turnerbundfrom 1859/60. The Turners promoted a socialism that concentrated on the rights and freedoms of the individual,10 10 The Turn-Zeitung (December 1st, 1851) printed an article with the title "Sozialismus und die Turnerei". and opposed monarchy and the religious indoctrination of the people. In terms of the socio-political circumstances prevailing in the United States, this meant that they fought American nativism, the system of slavery as well as the temperance and Sabbath-day laws.11 11 Socialist Turnerbund of North America, Constitutions adopted at their convention at Buffalo Sept. 24-2.7 Buffalo, 1855. Until the outbreak of the Civil War (1861–1865) the Turner societies had a strong political orientation. Their political attitudes reflected the opinions of the freethinkers, an anti-religious movement that advocated rationalism, science and history. Although the Turners had German roots, they considered themselves within the tradition of the American intellectuals Thomas Paine and Walt Whitman, who embodied political and religious freedom in an enlightened America. A close connection between the "Turners" and the freethinkers can be observed until the twentieth century.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries the Turner societies were "nurseries of ethnicities". According to Conzen they were places where German or rather German-American culture and traditions were fostered, as can be seen in their social and cultural activities. During their first decade the Turnvereine offered physical education classes – German Turnen. Their Turner Halls, places in which not only the German language but also German customs and celebrations were preserved, provided a social centre with political debates, lectures, Sunday schools and libraries for the further education of the German emigrants, and the attached restaurants or bars were popular places for German Gemütlichkeit.12 12 For further details see also Spears and Swanson (1988, p. 128-129) and Rader (1990, 56-60). Besides fostering German culture and nationalism, the Turners also tried to establish a bridge between the old culture and the new by offering English language classes and strongly supported American citizenship among their members to accelerate their integration into the everyday life of American mainstream society.13 13 Even today American Turners demand American or Canadian citizenship of their members. See Metzner (1989, p. 51). In 1851 the first National Gymnastic Festival (Turnfest) was organised, which was a competitive as well as a social event.

Just like other ethnic groups, the Germans had to fight the hostility of native-born Americans who did not approve of the high rate of immigration in their country. Especially in the Midwest, Turners were physically attacked on several occasions. To defend themselves they were urged by the Turnerbund to take up shooting and other military exercises in their physical programme. Later on, during the American Civil War, they could profit from these exercises in their military service (Hofmann, 2001Hofmann A. Aufstieg und Niedergang des deutschen Turnen in den USA. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 2001., p. 140). Up to the beginning of the twentieth century self-defence (Wehrturnen) in the form of fencing was part of the Turners’ physical culture and could also be found at the Turnfeste.14 14 See, for instance, Amerikanischer Turnerbund (1898, p. 22-23).

Despite the attacks by the nativist movement, the Turners expressed their political opinions in the American public sphere. Most of the Turners supported the political goals of the Republicans during the 1850s and 60s. This support resulted in the establishment of Lincoln's bodyguard during his first inauguration as well as the forming of the Turner regiments at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. Before the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 there were over 130 Turner societies in the United States (Hofmann, 2001Hofmann A. Aufstieg und Niedergang des deutschen Turnen in den USA. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 2001., p. 148–161).

In the postbellum years an era of reconstruction started not only for the American South but also for the Turner movement. The Socialistic Turnerbund, which had ceased to exist during the war years, was reorganised under a new name in 1865, namely, Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund. In these years the United States experienced a big German influx, coming to a peak in 1882 with over 250,000 newcomers (Doerries, 1986Doerries RP. Iren und Deutsche in der neuen Welt. Akkultura-tionsprozesse in der amerikanischen Gesellschaft im spaten neunzehnten Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag; 1986., p. 300). The German-American Vereinswesen took advantage of this influx, and so did the Turners. In many American cities new Turner societies were founded; others enlarged their membership. In these years a change in the Turner movement from political towards more cultural and educational values can be noted (Pumroy and Rampelmann, 1996Pumroy EL, Rampelmann K. Research guide to the turner movement in the United States. Westport, Connecticut/London: Green-wood Press; 1996., introduction). One of the main educational goals of the Turnerbund was the introduction of their physical training programmes in public schools. Another important task the union had to face after the war was the opening of their societies to women. Turnen for girls had already been introduced in the 1850s; exercise classes for women were set up three decades later and became very popular. Starting in the 1860s many societies also established Women's Auxiliaries over the next decades.

With the growing popularity of Turnen the need for physical educators or "Turnlehrer" rose, too, and a Turnlehrerseminar, which later became the Normal School of the American Gymnastic Union, was established in 1866 by the Turner union to educate professionally-trained instructors.15 15 In 1880 Dr. H.M. Starkloff of St. Louis, chairman of the executive committee of the Turner union, expressed the desire of the Turnersto find a new field of involvement: "How would it be if we should work with all our might to introduce physical training into the public schools of this country? We could not conceive of a more beautiful gift than this to bestow upon the American people." Thus, cities with a large German population introduced turnen in public schools(see Hartwell, 1886). He also states that this was the second institution in the United States in which one could become a physical education teacher. The first one was Dio Lewis’ Normal Institute for Physical Education, founded in 1861 in Boston. Today this institution is integrated in the physical education department of the Indiana University Purdue University at Indiana (IUPUI) in Indianapolis.

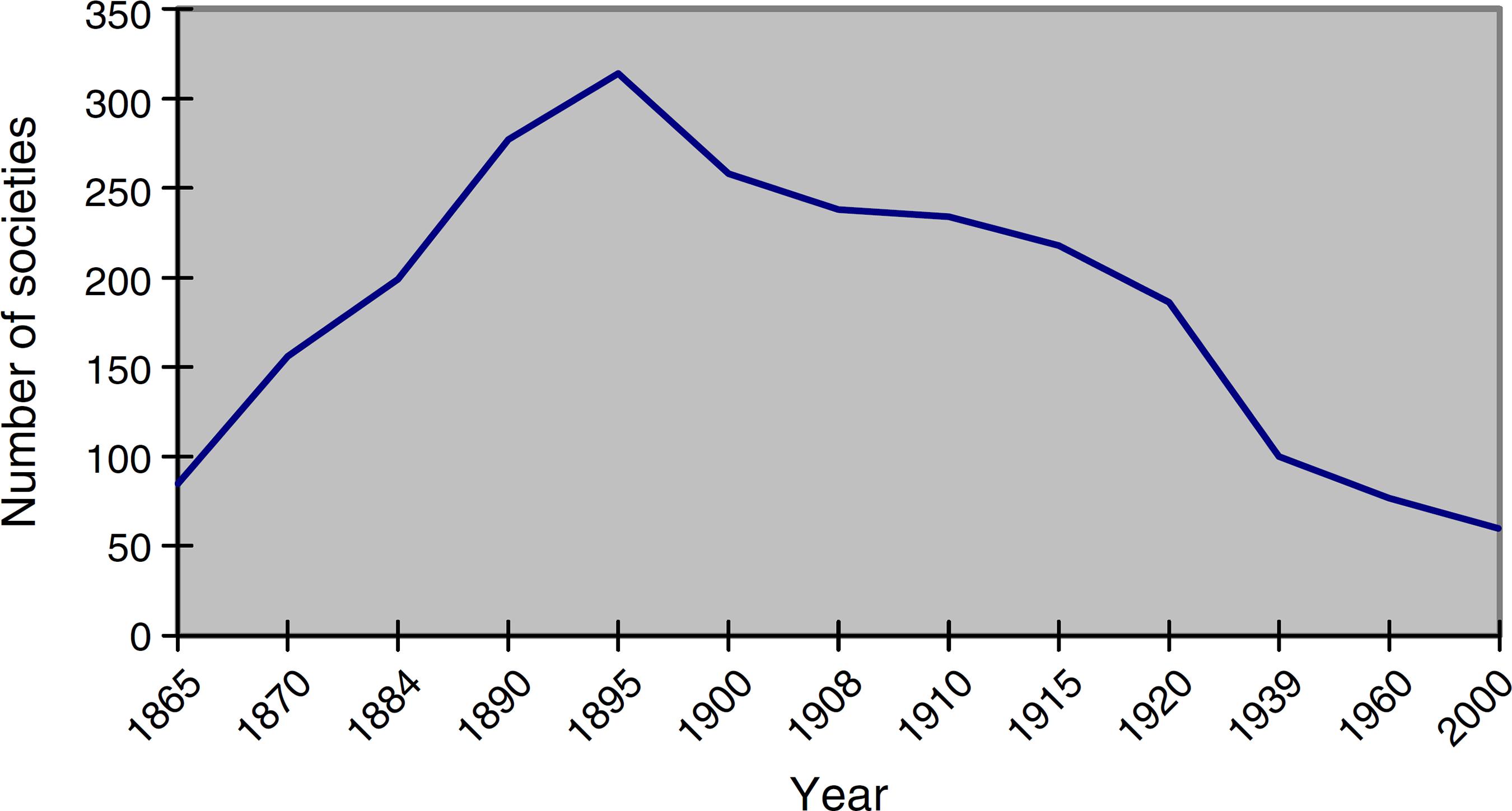

The peak of the American Turner movement was reached in 1894. At that time 317 societies existed with approximately 40,000 members, more than 25,000 children and around 3000 women participating in the activity classes.16 16 See, Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund (1896) or Barney, (1991, p.3) and Pumroy and Rampelmann (1996, p. 289). This boom had ceased by World War I, a time when the radical and socialistic tendencies in the Turner movement had also declined. One reason for this decline was probably the generation shift, since most of the "forty-eighters" and pioneers of social reforms were no longer alive.

Assimilation and Americanization of the Turners

Americanization is a special kind of transformation. It expresses a process of social and cultural change and thereby results in an assimilation and adaptation to American culture as well as an acceptance by the host society.17 17 See Häderle (1997, p. 20) and Gleason (1980, p. 39) and Kazal(1995, 440). Thus American culture, values and habits are adapted by a person or a group.

Over the years an assimilation process became visible among the German population, especially with the growth of the American-born generations. These newer generations were no longer fluent in German and to a certain extent had lost their cultural affinity to and interest in the land of their ancestors. This development towards assimilation and Americanization was also intensified by the anti-German politics of the American government in the years between 1914 and 1918. Many Americans with a German background were accused of lacking loyalty to the American nation. This anti-German hysteria fought everything that was German, especially the German language and German culture: "Kultur of the Kaiser's kind not to be promoted (…)" or "The German tongue has no place in America (…)" were slogans that could be read in a Cincinnati newspaper (Ott and Tolzmann, 1994Ott F, Tolzmann DH. The anti-German hysteria. German-American life on the home front. An exhibit on the commemoration of the 1994 Prager Memorial Day, April 5. University of Cinncinati Blegan Library; 1994.). This resulted in vandalism, a prohibition of the German language in schools and universities, the elimination of German journals and newspapers, the ban of German composers from concert halls, the closing of German theatres and the Americanization of German names, whether of persons, streets, towns, organisations or societies (Luebke, 1974Luebke CF. Bounds of loyalty. German-Americans and World War I. De Kalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press; 1974., p. 248–250).

The anti-German feelings during the years of World War I had a decisive influence on the change of identity of the German-Americans and with it, on the Turners. The German-American ethnic community collapsed; the group identity became more private in its expressions.18 18 Conzen (1984, p. 32). However, the number of Turner societies and membership remained constant during the years of World War I. The decline started after that war, and ended in 1943 when less than 100 societies with only 16,000 Turners belonged to the union.19 19 See Statistical Reports of the Nordamerikanischer Turnerbundand American Turners between 1914 and 1943.

In these decades between the wars the Turner movement also underwent an Americanization process, which is illustrated by the loss of German as the official language in protocols and the "Amerikanische Turnzeitung". By and by the societies also Americanized their names by dropping the German parts. The Nordamerikanische Turnerbund changed its name in 1938 into "American Turners" (AT). Three years earlier, Turner president George Seibel officially declared that the American Turner movement "has been the most American of all American associations"; the new slogan of the Turners became "Turnerism is Americanism".20 20 Annual Report of the Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund (1925,p. 11; 1935, p. 3) and Annual Report of the American Turners, (1938,p. 6). Thus, during World War II a completely Americanized Turner movement showed its loyalty to the American government.

After World War II the number of societies did not rise, but in the 1950s the membership numbers climbed to 25,000 again, organised in approximately 80 societies. One cause for this rise certainly was the new wave of immigration, which brought more than 500,000 German immigrants to the United States between 1950 and 1959 (Adams, 1993Adams WP. The German Americans: an ethnic experience. Indianapolis: Max Kade German American Center, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis; 1993., p. 6).

The American Turners at the end of the 20th century

At the beginning of the new21 21 Parts of this empirical study have already been published inHofmann (1999, p. 79-108). millennium, in 2002, there were still 58 societies22 22 In 2011 there were only 54 Turner Societies. The membership number seems to be stable. with approximately 12,000 members23 23 American Turners: Geographical Directory of Societies. 2002. Unpublished information and numbers of the AT. that were affiliated to the umbrella organisation American Turners, but not all of them showed any remnants of German-American culture. The typical Turnverein does not exist anymore. Besides the athletic programme social get-togethers dominate association life. Political discussions and the spread of German culture have lost their significance. The former German-American societies have grown into multi-ethnical societies, mostly with members from different European immigrant groups.

For over 150 years the Turnvereine have been part of the American world of sport. In 1998 the first American Turner societies celebrated their 150th anniversary, and in 2011 the 53th national Turnfest was organised by the AT, in St. Louis. The Turners were among the first to introduce physical education to American schools, and they founded the second institution in the United States in which physical education teachers or Turnlehrer were trained. Today the American Turners are members in American sport federations, USA Gymnastics and USA Volleyball (Figs. 1 and 2).

Ethnic-oriented societies,

Non-ethnic, social-oriented societies,

Recreational sports, social-oriented societies,

Competitive sports-oriented societies.

The ethnic category includes societies which primarily recognise German traditions and culture in their Vereinsleben (11%). For the members of these Turner societies, their Turnverein represents a kind of Heimatverein in the group of non-ethnic, social societies (5%). For these societies, a recreational sports program is of no importance. The members are ethnically mixed; however, members with a German heritage are in the majority. This is the same for the other categories. The majority of societies surveyed, (78%), belong to the third category which means they have a recreational and social program.26 26 Among these societies, only those that offer more than two sports were included. Here, gymnastics for children, golf, bowling and ball games dominate the athletic offerings. Other kinds of recreation such as track-and-field, tennis, dancing or fitness and health-oriented exercise programs exist only in a few societies. Thus, it can be concluded that for the majority of members, social aspects and networking elements play a role in their decision to offer certain sports or activities. "Lifetime" sports such as golf and bowling can be pursued at very advanced ages and thus meet the needs of older members, who, in many societies, constitute the majority of members.27 27 In the 1940 May issue of the ATT, volleyball for seniors and women was recommended and was popular. However, the article stated that it should not replace gymnastics. Five percent of the societies that participated in this survey belong to the competitive sports-oriented category. These Turnvereine offer gymnastics for children and adolescents and they participate in competitions organised by USA Gymnastics. The question begs to be asked whether it makes sense for them to be AT members.

The majority of the American Turner societies still offer a sports or recreational program; however, they cannot be viewed as an organisation which offers a vast sports and exercise program. The social component ranks high in the remaining societies, which can be attributed to the historical origins of the Turners. In the early decades of their existence, they served as centre for physical activities and they also were a centre for social get-togethers or meetings for German immigrants. This social component was of great significance and has prevailed, though in a somewhat different form.

Reflections on the Americanization of the American Turners

Americanization in the case of the Turner movement means the acceptance of the American constitution, adaptation to American values, traditions, rituals and symbols with a simultaneous decline of expression of German culture. In close relation to the Americanization of the Turners is also the acceptance of members of non-German origin in their societies, and the requirement of having American citizenship. But there is another side to this process as well. It is not only expressed by a loss of German-American ethnic identity and culture. Americanization also means a holding on to traits of the Turners culture and their demonstration by spreading them into a multicultural American society (Hofmann, 2010Hofmann A. The American turner movement: a history from its beginnings to 2000. Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center; 2010., p. 24–26). Some examples have already been mentioned.

By continuing not only certain rituals and customs from the "old" country, but also by adapting to new ones, in this case, American ones, new traditions arise, which are adjustments to the new, unfamiliar circumstances of the American host society. According to Eric Hobsbawm's theory of "invented traditions", traditions are invented, constructed and institutionalised. They have certain practices and rules which either become a ritual or are of symbolic nature. By means of repetition, certain norms and values that are linked with these traditions arise and continuity in regard to the past develops (Hobsbawm, 1995Hofmann A, Pfister G. Turnen - a forgotten movement culture. Its beginnings in Germany and diffusion in the United States. In: Hofmann A, editor. Turnen and sport. Transatlantic transfers. Münster: Waxmann; 2004. p. 11-24., p. 1f). Through the development of new symbols and traditions the Turners took up a new identity. This can also be seen in the acceptance of new symbols, which are not related to the German tradition. One of these symbols is the discus thrower, which became the official symbol of the AT in the second half of the 1930s.

Other examples are the national conventions and other big events of the Turners which are held under the Star-Spangled Banner and sometimes opened by the American national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance.28 28 The sources mention this ritual at least since the 1950s. Lately itwas performed at the sesquicentennial celebrations of the Cincinnati Central Turners, which were connected with the 67th national convention of the AT in August. The Turners are also purposely trying to "invent" new traditions such as a National American Turner Day, which Turner president Ed Colton initiated in 1993, or the composition of the American Turner March.29 29 See American Turner Topics vol. 40 (1993), 2f. and vol. 41 (1994), 3, 10f.

When discussing the Americanization of the Turners, the "Lady Turners"30 30 This is how female Turner members or lady auxiliary members call themselves. should not be forgotten. Especially the appearance of the ladies auxiliaries during the late 19th century and their existence until today have to be considered in the light of the special circumstances of an immigration country, such as the United States. On the one hand, these ladieś clubs offered opportunities for female German immigrants to exchange problems, meet friends, foster German culture and also support the "male Turner societies" through their help in various ways. On the other hand, the rise of lady clubs in general is an answer to the social conditions in the United States. Here the social net is not very well supported by the government, and relies on volunteer organisations, many of them founded in the 19th century. The ladies auxiliaries of the Turners still support not only the Turners, but also donate their time for different kinds of volunteer work and engage in different local affairs.

Throughout the Turners’ history these women showed their loyalty to the world of their men, who respected the ladies and integrated them in the Vereinsleben – however, without a right to vote. Later, in the twentieth century, most societies accepted females as members. Certainly this was not only for reasons of gender equality; in many cases female membership was needed for financial reasons. But still, some American Turnvereine held on to their tradition of being exclusively male societies. Not until the 1990s did all societies accept women. The percentage of females in the AT is not known; according to the information the empirical study yielded, it is probably lower than the male percentage. Here it becomes obvious that the AT is a traditional organisation.

The fact that the majority of the Turner societies belonging to the AT are over 100 years (and some even over 150 years) old and the actual content of the Vereinsleben – physical turnen and especially the social component of turnen – did not change much in the course of its history are further reasons why the AT can be described as a Traditionsverband. Although the political tendencies of the Turner movement weakened after a few decades and later entirely disappeared, the societies still stick to their social, cultural and athletic offers. These have changed and adapted American contents and forms. The attractiveness of turnen (gymnastics), which was an expression of a specific German body and movement culture, was reduced after the turn of the century. Especially during the second Americanization period, "sport" – especially team sports – was taken up by the societies. This was an answer to the changed membership, which had a higher percentage of American-born members, their needs and the American environment. Although today many societies still offer gymnastics for children and youth, it is of no more significance for their adult members.

The social part of the associational life is still of great significance. But it changed as well. In the 19th century it especially offered the possibility for German immigrants to communicate, and thus helped strengthen their ethnic identification. Presently most societies are still places for communication – which takes place in their bar areas – but it is no longer exclusively for German-Americans. They have a "neighbourhood or community function" for European Americans and fulfil their social needs (Doerries, 1986Doerries RP. Iren und Deutsche in der neuen Welt. Akkultura-tionsprozesse in der amerikanischen Gesellschaft im spaten neunzehnten Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag; 1986., p. 190).

Mental turnen, which has entirely lost its significance in Germany's Turnvereine, is still emphasised in the constitution of the AT, but in reality it is hardly pursued, and it has taken on new forms. Political debates, discussions, lectures or educational programs have disappeared. The former mental turnen has been transferred into "cultural turnen", and the societieś art, handicraft, literary and musical offers are part of it. However, only a few societies have these offers, which are included in the competitions at the national turnfest every four years, as well.

Conclusion

Americanization can be interpreted as acculturation and assimilation into American society. It occurs at political, cultural and religious levels. Demographic developments also play a role. In the German-American Turner movement, this process is reflected in the Turners’ recognition of the American Constitution, adoption of American values and traditions, lifestyles and symbols. But Americanization does not mean merely the abandonment, assimilation or weakening of ethnic identity and culture, rather it is also seen in the preservation, integration, and demonstration of specific traits of German culture, e.g., elements of the Turnvereinskultur, its values and ideals and integrating them into the multicultural American society.

Most of the Turner societies have been transformed into leisure sport and social societies for European-Americans that could also exist under a different name. The members of the individual societies follow the same interests and goals which their society fulfils through its offers. These offers are adapted to the present members. Still the number of Turner societies and Turners has been diminishing since the 1960s.31 31 See the statistical reports of the AT from the 1960s until 1999.

Many of the former Germany-American Turner societies have developed into multi-ethnic societies, with mostly members from different European immigrant groups. The pressure of American society to Americanize the Turner movement was stronger than the influence the Turners had on American society. This can be seen, on the one hand, by their bondage to certain traditions and Turner symbols of German heritage and identity and on the other hand, in their adoption of American values and adaptation to American society. The Turnvereine adapted to the new circumstances; they were transformed. However, it should not be forgotten that the ancestors of the Americans with a Germans past, who in the 1990s were the biggest ethnic group in the United States, have contributed to the building of an American culture, and an American Nation, although the traces are hardly noticeable today. Since the beginning of the 20th century the Turners have lost their influence on American physical education, and since the late 1960s the Turners cannot be found on American Olympic gymnastics’ teams anymore. The Turners have become a minority group in the American world of sport. The transformation and Americanization of the Turner societies resulted in their invisibility, and their future is uncertain.

-

1

See Hobsbawm (1985, p. 12).

-

2

See Luebke (1974, p. 43); Conzen (1989, p. 50; 58).

-

3

Frankfurter Allgemeine, March 12th, 1998.

-

4

On Turnen see for example the contributions Stump and Ueberhorst (1980, p. 215-229); Pfister, (1996, p. 14-36) and the special edition of Sportwissenschaft 2 (2000). A good overview ofthe history of Turnen and sport is also given in Krüger (1993).

-

5

The "Carlsbad Decrees" were measures agreed by the states ofthe German Confederation to suppress the liberal and democraticconstitutional movement as well as all strivings towards nationalunity.

-

6

On the role of the Turners in the 1948/49 Revolution see, for example Neumann (1968) and Krüger (1996).

-

7

Zucker points out in his description of 242 Forty-Eighters who left for the US that more than 60% were born in 1820 or later (1950, p. 270).

-

8

It is almost impossible to arrive at an exact number of allthe ‘48ers’ who emigrated to the United States. Sources estimate that no more than 3000-4000 persons emigrated for purely politically reasons between 1847 and 1856 (see Rehe, 1996, p. 13-15; Reppmann, 1994, 12-13).

-

9

See the Convention Protokoll of the Socialistische Turnerbundfrom 1859/60.

-

10

The Turn-Zeitung (December 1st, 1851) printed an article with the title "Sozialismus und die Turnerei".

-

11

Socialist Turnerbund of North America, Constitutions adopted at their convention at Buffalo Sept. 24-2.7 Buffalo, 1855.

-

12

For further details see also Spears and Swanson (1988, p. 128-129) and Rader (1990, 56-60).

-

13

Even today American Turners demand American or Canadian citizenship of their members. See Metzner (1989, p. 51).

-

14

See, for instance, Amerikanischer Turnerbund (1898, p. 22-23).

-

15

In 1880 Dr. H.M. Starkloff of St. Louis, chairman of the executive committee of the Turner union, expressed the desire of the Turnersto find a new field of involvement: "How would it be if we should work with all our might to introduce physical training into the public schools of this country? We could not conceive of a more beautiful gift than this to bestow upon the American people." Thus, cities with a large German population introduced turnen in public schools(see Hartwell, 1886). He also states that this was the second institution in the United States in which one could become a physical education teacher. The first one was Dio Lewis’ Normal Institute for Physical Education, founded in 1861 in Boston.

-

16 See, Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund (1896) or Barney, (1991, p.3) and Pumroy and Rampelmann (1996, p. 289).

-

17

See Häderle (1997, p. 20) and Gleason (1980, p. 39) and Kazal(1995, 440).

-

18

Conzen (1984, p. 32).

-

19

See Statistical Reports of the Nordamerikanischer Turnerbundand American Turners between 1914 and 1943.

-

20

Annual Report of the Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund (1925,p. 11; 1935, p. 3) and Annual Report of the American Turners, (1938,p. 6).

-

21

Parts of this empirical study have already been published inHofmann (1999, p. 79-108).

-

22

In 2011 there were only 54 Turner Societies. The membership number seems to be stable.

-

23

American Turners: Geographical Directory of Societies. 2002. Unpublished information and numbers of the AT.

-

24

American Turners: Geographical Directory of Societies. (1999); Hofmann (2001, p. 269-300).

-

25

The following information is based on the 37 Turner societies who completed a questionnaire.

-

26

Among these societies, only those that offer more than two sports were included.

-

27

In the 1940 May issue of the ATT, volleyball for seniors and women was recommended and was popular. However, the article stated that it should not replace gymnastics.

-

28

The sources mention this ritual at least since the 1950s. Lately itwas performed at the sesquicentennial celebrations of the Cincinnati Central Turners, which were connected with the 67th national convention of the AT in August.

-

29

See American Turner Topics vol. 40 (1993), 2f. and vol. 41 (1994), 3, 10f.

-

30

This is how female Turner members or lady auxiliary members call themselves.

-

31

See the statistical reports of the AT from the 1960s until 1999.

References

- Adams WP. The German Americans: an ethnic experience. Indianapolis: Max Kade German American Center, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis; 1993.

- Amerikanischer Turnerbund. Revidierte Festordnung. Milwaukee, WI: Freidenker Publishing Company; 1898.

- Barney RK. Knights and exercise: German Forty Eighters and Turnvereine in the United States during the antebellum period. Can J Hist Sports 1982;2:62-79.

- Barney RK. The German-American Turnverein movement: its histori-ography. In: Naul R, editor. Turnen und Sport. Münster/New York: Waxmann; 1991. p. 3-19.

- Conzen KN. Patterns of German-American history. In: Miller R, editor. Germans in America: retrospect and prospect. Tricentennial Lectures delivered at the German Society of Pennsylvania in 1983. Philadelphia: German Society of Pennsylvania; 1984. p. 14-36.

- Conzen KN. Ethnicity as festive culture: nineteenth-century Ger-man Americans on parade. In: Sollors W, editor. The invention of ethnicity. New York: Oxford Press; 1989. p. 44-76.

- Cunz D. They came from Germany. New York; 1966.

- Doerries RP. Iren und Deutsche in der neuen Welt. Akkultura-tionsprozesse in der amerikanischen Gesellschaft im spaten neunzehnten Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag; 1986.

- Geldbach E. Die Verpflanzung des deutschen Turnens nach Amerika: Beck, Follen, Lieber. In: Stadion; 1975. p. 360-70.

- Gleason P. American identity and Americanization. In: Thernstrom S, editor. Harvard encyclopedia of American ethnic groups. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press; 1980. p. 31-58.

- Haderle I. Deutsche kirchliche Frauenvereine in Ann Arbor. Eine Studie über die Bedingungen und Formen der Akkulturation deutscher Einwanderinnen und ihrer Tochter in den USA. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag; 1997.

- Hartwell EM. Physical Training in American Colleges and Univer-sities. Circulars of Information of the Bureau of Education. No-5-1885 ; 1886.

- Hobsbawm E. Introduction. Inventing traditions. In: Hobsbawm E, Ranger T, editors. The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1985.

- Hofmann A. Roots in the Past-Hope for the Future? The American Turners in the 1990s. Stadion XXV; 1999. p. 79-108.

- Hofmann A. Aufstieg und Niedergang des deutschen Turnen in den USA. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 2001.

- Hofmann A. The American turner movement: a history from its beginnings to 2000. Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center; 2010.

- Hofmann A, Pfister G. Turnen - a forgotten movement culture. Its beginnings in Germany and diffusion in the United States. In: Hofmann A, editor. Turnen and sport. Transatlantic transfers. Münster: Waxmann; 2004. p. 11-24.

- Kazal RA. Revisiting assimilation: the rise, fall and reappraisal of a concept in American ethnic history, vol. 100. The American Historical Review; 1995. p. 437-71.

- Krüger M. Einführung in die Geschichte der Leibeserziehung und des Sports, vol. 2. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 1993.

- Krüger M. Korperkultur und Nationsbildung. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 1996.

- Luebke CF. Bounds of loyalty. German-Americans and World War I. De Kalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press; 1974.

- Metzner H. History of the American Turners. Fourth revised ed. Louisville, KY; 1989.

- Neumann H. Die deutsche Turnbewegung in der Revolution 1848/49 und in der amerikanischen Emigration. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 1968.

- Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund. Jahresbericht des Vororts; 1896.

- Ott F, Tolzmann DH. The anti-German hysteria. German-American life on the home front. An exhibit on the commemoration of the 1994 Prager Memorial Day, April 5. University of Cinncinati Blegan Library; 1994.

- Pfister G. Physical activity in the name of the Fatherland: Turnen and the National Movement (1810-1820). Sport Herit 1996;1:14-36.

- Pumroy EL, Rampelmann K. Research guide to the turner movement in the United States. Westport, Connecticut/London: Green-wood Press; 1996.

- Rader B. American sports. From the age of folk games to the age of televised sports. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1990.

- Rehe C. Von den Fildern nach Amerika. In: Alltag von Auswan-derern im Spiegel ihrer Briefe. Eine mentalitatsgeschichtliche Annaherung. Filderstadter Schriftenreihe zur Heimat und Lan-deskunde. Filderstadt: aKlein Filderstadt; 1996. p. 13-5.

- Reppmann J. Freiheit, Bildung und Wohlstand für Alle! Schleswig-Holsteinsche "Achtundvierziger" in den USA 1847-1860. Wyk auf Fohr: Verlag für Amerikanistik; 1994.

- Reppmann J. Theodor Gülich aus Schleswig-Holstein in Amerika-Weltbürger, Turner und Revolutionar. In: Hofmann A, Krüger M, editors. Südwestdeutsche Turner in der Emigration. Schorndorf: Hofmann Verlag; 2003. p. 123-32.

- Spears B, Swanson R. History of sport and physical education in the United States. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers; 1988.

- Stump W, Ueberhorst H. Deutschland und Europa in der Epoche des Umbruchs: Vom Ancien Régime zur bürgerlichen Revolution und nationalen Demokratie - Friedrich Ludwig Jahn in seiner Zeit. In: Ueberhorst H, editor. Geschichte der Leibesübungen, vol. 3/1. Berlin/München/Frankfurt: Bartels & Wernitz; 1980. p. 215-29.

- Wieser L. 150 Jahre Turnen und Sport in Mannheim; 1996.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Apr-Jun 2015

History

-

Received

01 Aug 2011 -

Accepted

28 Nov 2014