ABSTRACT

The article analyses the visual series consisting of 65 photographs of coffee plantations in the Paraíba Valley taken by Marc Ferrez between 1882 and 1885. By studying his social circuits, it can be seen that the visual discourse composed by these photos valorized coffee complexes as modern spaces of production and remains silent about the marks of slavery on the individuals registered. As a result of technical, cultural, and social choices, a ‘pacified slave’ is constructed in the figuration space of the photo, protected from social conflicts, abolitionist ideas, and slave resistance. In this way, Marc Ferrez’s images strongly fulfill the political function of forming and shaping a given memory about slavery, which by pacifying that extremely violent world, directly interested the ruling class of the Empire.

Keywords:

slavery; photography; Paraíba Valley

RESUMO

O artigo analisa a série visual composta por 65 fotografias das fazendas de café do Vale do Paraíba produzidas por Marc Ferrez entre 1882 e 1885. Por meio do estudo de seus circuitos sociais percebe-se que o discurso visual composto por elas valorizava os complexos cafeeiros como espaços modernos de produção e silenciava as marcas da escravização dos indivíduos registrados. Mediante escolhas técnicas, culturais e sociais, construiu-se no espaço de figuração da foto uma “escravidão apaziguada”, protegida dos conflitos sociais, das ideias abolicionistas e das resistências escravas. Dessa forma, as imagens de Marc Ferrez cumpriram fortemente a função política de formar e conformar uma dada memória sobre a escravidão que, ao pacificar aquele mundo extremamente violento, interessava diretamente à classe senhorial do Império.

Palavras-chave:

escravidão; fotografia; Vale do Paraíba

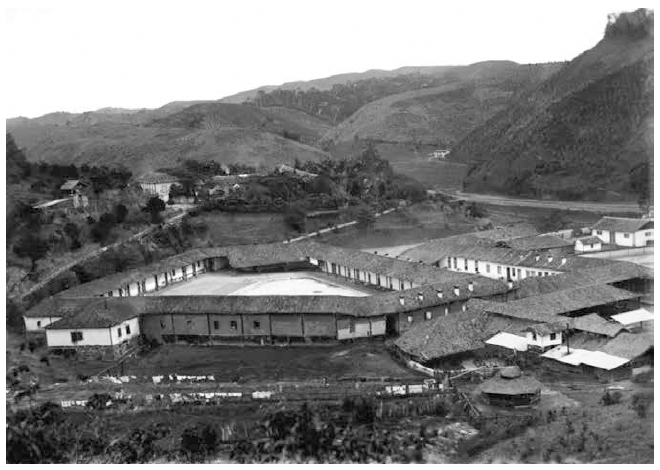

Cachoeira Grande Plantation, Rio das Flores. Marc Ferrez, 1880s. Gilberto Ferrez Collection, IMS.

Coffee planting reached the Fluminense Paraíba Valley region between 1800 and 1820. Its rapid flourishing can be explained by various aspects: an expanding external consumer market, the widespread availability of free and fertile land, the effective structure of the black slave trade, a private capital reserve for new investment, mule transport know-how developed during mining, and a network of roads and outlets (commercial and police roads) which linked the river ports of Iguaçu, Estrela, and Porto das Caixas, from where the coffee continued to the casas comissárias (commissionary houses) in the capital, and afterwards to their different destination in the United States and Europe (Marquese; Tomich, 2015_______.; TOMICH, Dale. O Vale do Paraíba escravista e a formação do mercado mundial do café no século XIX. In: MUAZE, Mariana; SALLES, Ricardo. O Vale do Paraíba e o Império do Brasil nos quadros da segunda escravidão. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras; Faperj, 2015., p. 22). This process of creating the coffee plantation and slave-holding structure occurred concomitantly with the construction of the Imperial state and ruling class itself in the 1840s (Mattos, 1986MATTOS, Ilmar. O Tempo Saquarema. Rio de Janeiro: Access, 1986., p. 50), during the so-called ‘second slavery’ (Tomich, 2011TOMICH, Dale. Sob o prisma da escravidão: trabalho, capitalismo e economia mundial. São Paulo: Edusp, 2011.). Later, with a wide-ranging and consolidated support base, it was possible for the Saquarema governors to maintain a pro-slavery policy which favored slaveholders until the 1871 Ventre Livre Law (free womb law) at least. After this the Imperial state underwent a crisis of hegemony, which worsened in the 1880s with the advance of the abolitionist campaign, republican movements, international anti-slavery pressures, and the flights and direct actions of slaves (Salles, 2008SALLES, Ricardo. E o Vale era escravo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2008.). In trying to respond to these demands through the Sexagenarian (1885) and Aurea (1888) laws, the imperial government definitely broke with those who guaranteed its political support, though without having won a new social base.

The photograph which opens the article was taken by the French-Brazilian Marc Ferrez (1843-1923) between 1882 and 1885, in other words during the slavery crisis. It is part of an extensive visual series which portrays the production of coffee in the Paraíba Valley. Including duplicates, the set has 65 glass negatives belonging to the Gilberto Ferrez Collection, safeguarded in the Moreira Salles Institute (IMS). Of these originals, it is known that at least ten were printed by Marc Ferrez & Cia. in a special edition containing authorship, stamped with the studio address, signature, and titles in French. Currently six of these examples are part of the Thereza Christina Maria collection in the National Library, and four belong to the Wiener Collection, of the Library of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Lago, 2001LAGO, Pedro Corrêa do. Marc Ferrez nas coleções do Quai d’Orsay. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 2001.). Moreover, other images from the series became post-cards and circulated from the first decade of the twentieth century onwards (Muaze, 2014MUAZE, Mariana. A escravidão no Vale do Paraíba pelas lentes do fotógrafo Marc Ferrez. In: CARVALHO, José Murilo de; BASTO, Lúcia. Dimensões e fronteiras do Estado Brasileiro no Oitocentos. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Uerj, 2014.). Therefore, the large quantity of photographs produced, as well as the diversity of support, archives and collections where they are found, demonstrates the widespread distribution, circulation, agency, and consumption which they had in different public and private spaces, both in Brazil and abroad.

In this article, I defend that the annunciation of Ferrez’s photographic message took place in the world of the large slaveholding landholders, who lived between nostalgia for a past in which slavery was an uncontested system from the economic and humanitarian point of view, and the perspective of the construction of a modern society following the example of European nations. In this aspect, there was a paradox between the longed-for world, based on industrial rationality, and the existing slaveholding reality. As a solution for this, the aesthetic found by Ferrez to record the plantations in the valley was associated both with the traditional photography of landscapes and of ‘human types,’ present in nineteenth century visual culture. Thus, at the same time that the images analyzed represented Marc Ferrez’s vision of the coffee plantations at the end of the nineteenth century, they also spoke about a determined and socially shared manner of seeing and allowing to be seen both slavery and the agrarian world in the Paraíba Valley. However, the telescopic, panoramic, and socially distant perspective chosen could not prevent all ‘returned looks’ on the part of the subjects photographed, in the case of the slaves, and it is up to the historian to look for the traces of humanity of those men and women at the moment the photograph instituted their self-representation (Mauad, 2000MAUAD, Ana Maria. As fronteiras da cor: imagem e representação fotográfica na sociedade escravista imperial. Locus, Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, v.6, n.2, p.83-98, 2000. Disponível em: https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus/article/view/2363.

https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus...

; Koutsoukos, 2010KOUTSOUKOS, Sandra Sofia Machado. Negros no estúdio do fotógrafo: Brasil, segunda metade do século XIX. Campinas: Ed. Unicamp, 2010.).

Having said this, it should be asked: why produce such an extensive photographic set of slaveholding plantations in the 1880s, when this world was starting to decline? What did these images intend to communicate about rural slavery at the end of the Empire? To which public and social spaces where they addressed? What do they say about the society which produced them? To answer these questions within the limit of this article, I propose a reflection which describes the visual set in relation to its production, circulation, consumption, and action. For this investigative prism, the image stops being a mere repository of the message in itself, to become the support for the social relations established. Photography thus educates the ‘look’ and institutes its own time, not only as a (random and/or faithful) registration referring to the moment when the photo was taken, but also as a representation which operates with the constitutive elements of the visual culture in question (Mauad, 2004_______.; MUAZE, Mariana. A escrita da intimidade: história e memória no diário da viscondessa do Arcozelo. In: GOMES, Ângela de Castro (Org.) Escrita de si, escrita da história. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. FGV, 2004.; Meneses, n.d.MENESES, Ulpiano T. Bezerra de. A fotografia como documento: Robert Capa e o miliciano abatido na Espanha: sugestões para um estudo histórico. Tempo, Rio de Janeiro, n.14, p.131-151, s.d.).

MARC FERREZ AND THE SOCIAL CIRCUIT

OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

The invention of photography in France at the end of the 1830s, was directly related to the expansion of modern capitalism, to the growing social demand for images and for the need to give expression to individuality in a world in transformation. This artifact was thus born with an image concerned with consumption and involved in a commercial circuit dictated by the logic of the market (Fabris, 1998FABRIS, Annateresa. A invenção da fotografia: repercussões sociais. In: _______. Fotografia: usos e funções no século XIX. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998.; Sontag, 2004SONTAG, Susan. Sobre fotografia. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2004.). When it reached Brazil photography essentially spread in two forms: portraits, used as a means of social distinction by members of the dominant class, and views or landscapes which helped in the preparation of an image of the Brazilian nation to be projected in the Western culture. Portraits were prepared in the visiting card (6 x 9.5 cm photos, stuck on cardboard measuring 6.5 x 10.5 cm) and cabinet size (10 x 14 cm photo, stuck on 16.5 cm cardboard) formats and circulated among the wealthy who exchanged them, sent them by letter, put them in family albums or collections, and insisted on using the most prestigious ateliers for reasons of social differentiation (Vasquez, 2003VASQUEZ, Pedro Karp. O Brasil na fotografia oitocentista. São Paulo: Metalivros, 2003.; Fabris, 1998FABRIS, Annateresa. A invenção da fotografia: repercussões sociais. In: _______. Fotografia: usos e funções no século XIX. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998.; Turazzi, 1995_______. Poses e trejeitos: a fotografia e as exposições na era do espetáculo. Rio de Janeiro: Funarte; Rocco, 1995.).

Views or landscapes were generally developed in the 18 x 24 cm size, their visualization involved a widespread public, and they circulated both as souvenir photos, offered in specialized shops, and in national and international exhibitions where they competed for awards or appeared in the pavilions of participating countries. In the former case, the photograph was an object to be collected, a souvenir of a journey, or touristic artifact, which could be sent to different locations. In the latter case, it fulfilled the function of divulging the attributes of modernity or the exoticism of the places and people registered. In aesthetic terms, despite the similarities of the canons of landscapism and romantic painting (bi-dimensional and rectangular space, the search for symmetry and beauty, proportionality), landscapes had their own language developed in harmony with the visual culture practices in vogue.

The majority of the photographic representations of slaves and freedmen in the nineteenth century were presented in the two specified modalities. In the case of portraits, a fundamental difference could be seen in relation to those photographed. First, there were those who appeared in the studio as customers. They were freedmen, descendants of slaves or domestic slaves who paid directly for the photography or had it paid for by the ruling class families they worked for. The circulation of these images was restricted to the family and private sphere (Koutsoukos, 2010KOUTSOUKOS, Sandra Sofia Machado. Negros no estúdio do fotógrafo: Brasil, segunda metade do século XIX. Campinas: Ed. Unicamp, 2010.). Access of these social groups to photography was allowed after the invention and popularization of the visiting card which, by producing six images in one click, cheapened production and stimulated the opening of studios with more accessible prices. In these cases, the artifice of the pose and the mise-en-scène were not very different from those of the ruling class (Fabris, 1998FABRIS, Annateresa. A invenção da fotografia: repercussões sociais. In: _______. Fotografia: usos e funções no século XIX. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998.).

Second, there were photographs of slaves and freedmen as ‘human types’ (linked to work: sellers, carpenters, milkmen, basketmakers, etc.) or exotics (emphasizing African costumes and accessories, naked bodies, tribal scars, etc.), which were the more common. These images focused on human otherness, social types, and the exoticism of slaveholding societies (Cunha, 2000CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da.Olhar escravo, ser escravo. In: NEGRO de corpo e alma. (Catálogo, “Mostra do Redescobrimento”, org. Emanoel Araujo).São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo; Associação Brasil 500 Anos Artes Visuais, 2000.). Their reproductions were sold in large quantities in photographic ateliers and bookshops, as well as announcements in newspapers and weekly publications, as there appears published in the Almanack Laemmert in 1867 by the photographer Christiano Jr: “a varied collection of black costumes and types, something very suited for those going to Europe” (Mauad, 2000MAUAD, Ana Maria. As fronteiras da cor: imagem e representação fotográfica na sociedade escravista imperial. Locus, Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, v.6, n.2, p.83-98, 2000. Disponível em: https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus/article/view/2363.

https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus...

, p. 89). Alberto Henschel, Rodolpho Lindemann, Felipe Augusto Findanza, João Goston, João Ferreira Villela, Auguste Stahl, Christiano Jr., and Marc Ferrez himself produced images of ‘black types’ and exotics which strongly met the needs of the foreign consumer market and had a guaranteed large-scale circulation and consumption. In these cases, what was of interest was the representation of blacks as slaves and of the traditions of distant lands. Those appearing the photographs were not customers, consumers of images with a family and private circulation, as previously discussed. Rather, it was a “portrait of the black for the white,” as Ana Maria Mauad defined (2000MAUAD, Ana Maria. As fronteiras da cor: imagem e representação fotográfica na sociedade escravista imperial. Locus, Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, v.6, n.2, p.83-98, 2000. Disponível em: https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus/article/view/2363.

https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus...

, p. 97). In the images of ‘human types,’ the registers of black bodies had a sale value, they were merchandise for public consumption due to their peculiarity, particularity, and exoticism. The differences between the images which portrayed blacks as exotic types and those where they appeared as customers, the consumer of photographs, seeking to adapt them to a given social habitus, can be noted in Figures 2 and 3.

In this sense, although they adopt a focus, angle, direction, distance, and lighting differentiated between themselves, the portraits of ‘human types’ and the landscapes and view are similar in that they seek to meet the new morality of consumption inherent to modern society: tourism (Brizuela, 2012BRIZUELA, Natalia.Fotografia e Império: paisagens de um Brasil moderno. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras; IMS, 2012.). Considered as an analogon of nineteenth century reality, photography permitted visual knowledge of distant places, people, and cultures, previously inaccessible to the majority of the population, giving a feel of ‘approximating the world’ (Süssekind, 1990SÜSSEKIND, Flora. O Brasil não é longe daqui: o narrador, a viagem. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1990.). With the advance of the tourism industry in the second half of the nineteenth century, many professionals sought to contemplate the new market niche of the so-called souvenir photos, and Marc Ferrez was not left behind. The themes he covered were various. However, without a doubt the city of Rio de Janeiro was his most photographed object (Ferrez, 1985FERREZ, Gilberto. O Rio de Janeiro do fotógrafo Marc Ferrez. 2.ed. São Paulo: Libris, 1985.). To represent it, Ferrez chose symbolic landmarks of the Carioca landscape and constructed, nationally and internationally, an image of the place where urbes and nature were integrated, transpiring harmony and with few social contrasts (Turazzi, 2000TURAZZI, Maria Inês. Marc Ferrez. São Paulo: CosacNaify, 2000., p. 43).

Scholars of nineteenth century photography are unanimous in stating that Marc Ferrez was the professional who most dedicated himself to the landscapes of Brazil in the nineteenth century. In 1859, he started working in the renowned Casa Leuzinger (belonging to the photographer George Leuzinger); six years later he would open Casa Marc Ferrez e Cia., his own atelier and soon would asvertise: “Brazilian Photography - specialty of views of Rio and surrounding of all dimensions. Views taken of chacras [sic], ships, monuments, etc. etc. of all sizes at resoable [sic] rates” (Jornal do Commercio, 6 Jun. 1869). With this English language advertising, he had the dual intention of attracting foreign buyers, those most interested in the photography of Rio de Janeiro’s landscapes, but also the ruling class in the capital and the provinces who wanted to register their houses, palaces, plantations, and other places of memory.

To conquer clientele and compete with other professionals from the area, Ferrez developed his own technique. During his career, he invested in the improvement of chemicals and equipment, such as photographic machinery to get the panoramas he idealized, ordered from the Frenchman M. Brandom, and the first dry photosensitive plates manufactured by the Lumière brothers, which he introduced to the Brazilian market. In the 1870s Ferrez achieved international recognition as a professional and researcher of photographic materials in tropical environments. His expertise earned him various commissions and important titles: photographer of the Imperial Navy (1877), photographer of the Imperial Geological Commission, headed by Charles Frederick Hartt (1880), photographer of the Pedro II Railway and the Corcovado Railway (1882), photographer of the Paranaguá-Curitiba Railway (1886, whose album was incorporated in the collection of the Société de Géographie de Paris) and photographer of the Rio de Janeiro water supply works (1889). The accumulated experience guaranteed him seasonal contracts and consequently greater remuneration and prestige in comparison with photographers who mostly took portraits (Turazzi, 2000TURAZZI, Maria Inês. Marc Ferrez. São Paulo: CosacNaify, 2000.; Kossoy, 2002KOSSOY, Boris. Dicionário histórico-fotográfico brasileiro: fotógrafos e ofício da fotografia no Brasil (1833-1910). São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Sales, 2002.).

In the 1880s, when he produced the series analyzed in this article, Ferrez was also acknowledged as the best photographer of views and landscapes in the country. The invitation for the work came from the Center of Agriculture and Commerce (Centro da Lavoura e do Comércio - CLC), founded in 1881 by important coffee producers and factors from the Southeast2 2 The Center of Agriculture and Commerce was founded to “resist this anarchy which has been created, to determine exactly the most useful course for the national economy, establish on solid foundations its industry, widen the circle of commercial relations, entice the esteem of other countries, affirming it in the conveniences of exchange, and thereby constitute a rich, prosperous, and respected state, this is primordial aim of our association” (CLC, 1882). Among its principal members were coffee planters and factors, such as: Honório Ribeiro; Hermano Jopert; the Baron of Quartim; the Baron of Araújo Ferraz; Eduardo Rodrigues Cardoso Lemos; Carlos Augusto Miranda Jordão; Joaquim de Mello Franco; Honório de Araújo Maia; Bruno Ribeiro; João Valverde de Miranda; the Baron of São Clemente, and Joaquim da Costa Ramalho Ortigão. Its principal base of political and economic support were the municipal Agricultural Clubs (Clubes da Lavoura) which, through an organizational network structured in different locations, acted to maintain the constituted slave-holding order. However, with the growth of the abolitionist movement in the 1880s, there was a radicalization of the local Agricultural Clubs and many began to operate with armed militias to protect plantations, destroy quilombos, and intimidate abolitionists (FERREIRA, 1977; SWEIGART, 1980; MACHADO, 2010). linked to the slaveholding ruling class and willing to defend their political and economic interests. One of the objectives of the institution was to provide those visiting international exhibitions with a visualization of the productive process of Brazilian coffee to advertise the product and expand business. For Ferrez the project was of great interest, since it guaranteed him remuneration, professional recognition, and opportunities to compete for photographic awards, as well as the selling as souvenirs the views and landscape which had the greatest national and foreign appeal.

The so-called universal exhibition had great projection during the second half of the nineteenth century, and acted as a “shop window for progress” (Neves, 1986NEVES, Margarida de Souza. As vitrines do progresso. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. PUC, 1986.). Its principal tonic was to diffuse the wonders of modernity developed by the principal western capitalist nations (Hardman, 2005HARDMAN, Francisco Foot. Trem-fantasma: a ferrovia Madeira-Mamoré e a modernidade na selva. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2005.; Pesavento, 1997PESAVENTO, Sandra J. Exposições universais, espetáculo da modernidade do século XIX. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1997.). The first was held in Crystal Palace in London on 1 May 1851 with the presence of Queen Victoria and counted on an estimated total public of six million people. Definitely a mass event for the epoch. Brazil’s debut in these events was in 1862, during the second London exhibition. However, in 1878, in the Paris exhibition the imperial government cancelled new participations alleging budget cuts due to the Paraguay War. After that, the organization of the Brazilian pavilion was led by the Center of Agriculture and Commerce (CLC) whose organization of the Brazilian pavilion debuted in 1882.

By assuming the costs of Brazilian stands in the universal exhibitions, the CLC prioritized coffee over other Brazilian agricultural products with the clear intention of disseminating the quality of Brazilian beans, increasing demand for the product, and winning new markets. Preparation for the international shows started beforehand with annual events in the capital. Participating in these preliminaries were the largest coffee producers from Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and São Paulo, who had their beans assessed in relation to quality and variety, as well as sellers of agriculture apparatus and some invited speakers to talk about the importance of Brazilian coffee. These events were an excellent opportunity for the cream of slaveholding planters and merchants involved in the exporting of coffee to meet. In terms of ornamentation, the sample included in natura branches of coffee plants, exhibition showcases, and numerous photographs pinned to the walls. Such investments sophisticated the advertising mechanisms used. In 1884, during the St. Petersburg exhibition, for example, images of the production of coffee beans, catalogues, and informative leaflets were all provided, while a winter garden was even put together for the free tasting of the best types of Brazilian coffee. These efforts were rewarded with the visit of Tsar Alexander III and the imperial family to the Brazilian stand (Muaze, 2014MUAZE, Mariana. A escravidão no Vale do Paraíba pelas lentes do fotógrafo Marc Ferrez. In: CARVALHO, José Murilo de; BASTO, Lúcia. Dimensões e fronteiras do Estado Brasileiro no Oitocentos. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Uerj, 2014.).

The choice of Marc Ferrez to register coffee production in the Paraíba Valley should be understood as yet another of CLC’s propagandistic efforts to increase exports and show that Brazil was part of the Western ‘civilizing march’ through the growing of rubiaceae. The international recognition and projection of the photographer, as well as the images exposed in large formats, were intended attract the attention of the visiting public and to add value to the Brazilian production it was intended to highlight in relation to the competition. As a result, the manner in which the coffee plantations and their workers were represented in the images was fundamental for those who contracted Ferrez to achieve the positive results expected from the public.

While the CLC administered the organization of the Brazilian pavilion, Ferrez won various awards representing the young nation: the Continental Exhibition of Buenos Aires (1882, silver medal and merit prize); International Exhibition of Amsterdam (1883, bronze medal with the “photography album of the principal bridges and construction works on the Pedro II Railway”); International Exhibition of St. Petersburg (1884, received a prize for 24 photographs of bridges in Rio de Janeiro, Santos, Petrópolis, and other places from the interior of Brazil); the Universal Exhibition of Antwerp (1885, bronze medal for 31 views of Rio de Janeiro) and the International Exhibition of Beauvais (1885). All these conquests increased Ferrez’s prestige, who also revived the title of Knight of the Order of the Rose, granted by the Emperor on 7 March 1885, and honors from José Maria da Silva Paranhos, the Baron of Rio Branco, during the 1889 Universal Exhibition of Paris, when he was decorated with the gold medal and published Album de Vues de Brésil.

In Catálogo das Obras Expostas no Palácio da Academia Imperial de Bellas Artes it is stated that Marc Ferrez exhibited the following photos - “views of a coffee plantation, colonists’ house, plantation, ranch, coffee drying patio, selection of coffees, transport of coffee” - in the 1885 exhibition in Beauvais, France. As well as the exhibits, these images were projected for the public using Alfred Molteni’s system, known as the magic lantern. This type of entertainment was popular in Europe, brought together a large concentration of people and allowed the visualization of images on a large flat screen in a dark place. The acceptance and circulation of Ferrez’s work indicates, however, that he not only fulfilled the prerogatives of the visual culture then in force, but also produced it, constructing and shaping interpretations of Brazil and its peoples with a wide spectrum of action.

Of the series being discussed here, both the images sent to represent Brazil in the great exhibitions (exhibited on the Brazilian stand, in the photography competition, or in sessions of the magic lantern), and those circulated as souvenir photos for collectors and the curious, expressed Ferrez’s vision constructed through the ‘white world.’ In the images divulged, the exacerbation of the role of the Paraíba Valley as an agricultural producer, supplier of foodstuffs, as well as possessing a privileged, vast, exuberant, and exotic nature was in harmony with the discourse of the slave-owners and of Imperial state about themselves. As its own visual language, Ferrez valorized harmony between nature (coffee plants, hills, and geography) and civilization (constructions, machinery, coffee yards), and presented an environment without social conflicts. In a dialectic relationship, the photos of Ferrez help to forge internally and externally a representation of Brazil as an agricultural country, proud of the role it played in the list of forces established with European civilization, thereby placing itself as a rising member of the industrialized capitalist world by way of title of the greatest producer of coffee in the world. This interpretation of Brazil was not restricted to the series dealt with in this paper and is present in other rural environments recorded by Ferrez in the 1880s, such as the example of the photos entitled “washing diamonds in Minas Gerais,” “gold diggers in search of gold in Minas Gerais,” “washing and extracting diamonds in Minas Gerais” (1880), “sugarcane plantations,” “locomotive removing the production of sugarcane,” “working inside the mine,” “gold digger in Minas Gerais,” “mine shaft in Mariana,” and “water wheel” (1885) (Ermakoff, 2004ERMAKOFF, George.O negro da Fotografia Brasileira do século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: Casa Editorial G. Ermakoff, 2004.). Once more, the theme is the production of primary foodstuffs and slave labor in the middle of ‘nature which provides everything,’ corroborating the agricultural and extractivist specificity of Brazil, as well as reinforcing the definition in force of the triad of economic wealth in the country: sugarcane, gold, and coffee. In the urban images, the way Ferrez portrayed Rio de Janeiro, tracing an intense dialogue between constructions and the exuberant tropical nature, helped to weave a striking visual representation for the seat of the monarchy (Turazzi, 2000TURAZZI, Maria Inês. Marc Ferrez. São Paulo: CosacNaify, 2000.). It is thus possible to state that Ferrez valorized the nature and geography of the place as symbols of the young nation due to their specificities.

The photography of coffee plantation aimed to compose an image for Brazil which could be displayed in the national and international spheres. In the first case, he spoke to the dominant class, to the slave owners of the Paraíba Valley, the region with the highest concentration of captives in the Empire in 1880. For them, the record made the slave system into a monument through a nostalgic and romantic reading in relation to a time which would not return. A time threatened by the abolitionist movement, the Caifazes movement from São Paulo, mass flights of slaves, and the abolition already achieved in Ceará, in Amazonas, and in parts of Rio Grande do Sul (Machado, 2010MACHADO, Maria H. O Plano e o Pânico: os movimentos sociais na década da Abolição. São Paulo: Edusp, 2010.). In the latter case, it was aimed at a wider and more diverse public which covered middle class urban sectors which strongly condemned slavery. After the American Civil War, with the increase of abolitionist movements and slave pressures, the economic, political, and humanitarian contestation of slavery grew nationally and internationally. The binomial of slavery and civilization could no longer be supported. In the movement of this meaning, it was necessary to exercise a visual language which pointed to a future perspective of modernity.

As can be seen, the images in question were produced within a slave world with essential limits in relation to its reproduction. These presented a strong tension between the slave holding experience, interpreted as successful by the slave owners, but destined to end in the middle of the 1880s, and a horizon of expectations in which slave labor would disappear due to a series of internal and external factors (Koselleck, 2006KOSELLECK, Reinhart. Futuro passado: contribuição à semântica dos tempos históricos. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto; Ed. PUC-RJ, 2006.). However, it was believed that the rural economic order could be maintained. For this, the images produced pointed to the monumentality of the constructions, new technologies, as well as the importance of Brazil as an agricultural exporting country, this being the perspective of insertion in the modern world. This tension between the past and the future appears in the desire to register slavery, the world of slaves, and their masters. Ferrez immortalized slavery through photography and eternalized the memory of a past seen as glorious. However, the visual discourse produced camouflaged the marks of violence, the subjection of man by man, conditions of existence of the very system of slavery.

As a conciliatory representation, Ferrez constructed images of a slavery ‘without coercion,’ ‘pacified,’ or even mimicked with other types of free relations of labor, such as parceria and colonato (types of sharecropping), experienced by European immigrants in various rural areas in the country. In the latter case, there is an image described as a ‘house of colonists’ in a projection made in 1885 and another four photos related to the theme of ‘coffee harvesting,’ when male and female immigrants appear working in the fields. In none of these images do there appear slaves. Rather, Ferrez’s option was to valorize the few free coffee workers in the Fluminense Paraíba Valley and to remain silent about the extensive use of slave labor as a hegemonic alternative by the large landholders in the majority of properties in this region. Ultimately, his images projected a future, a horizon of expectations, in which the tensions of slaveholding society were absent from the photos.

WHAT SLAVERY IS THIS?

The serial analysis of the 65 images allows a verification of how Marc Ferrez composed his visual narrative of slavery and coffee production in the Paraíba Valley. There is no prior organization of the images imposed by the photographer or anything inscribed on their backs which indicate their arrangements. What is known is that these images were archived containing the dates 1882, 1884, and 1885, as well as there being little information identifying the plantations, people, and places recorded. However, Ferrez’s choice of the agrarian space for his reference is striking. Also impacting is his preference of four guiding themes: (1) the functional quadrilateral: 37% of the images, with an emphasis on constructions linked to coffee production; (2) coffee harvest / coffee plantation: 32% of images, prioritization of planting and work spaces; (3) leaving for work: 13% of images, registering the departure of slaves to work in the fields; (4) oxcart / transport: 18% of images, highlighting the principal cargo transport used in the plantations.

Balancing the numbers presented here in relation to the guiding themes, it can be perceived that 69% of the photographs (themes 1 + 2) show the coffee plantation as a large complex composed not only of constructions which are part of the so-called functional quadrilateral, but also by virgin forests, coffee plants, and other plots of land worn out by intense planting. The juxtaposition of these images composes a picture of the difference spaces on the plantation (main house, senzala (slaves’ quarters), warehouses, mill, yards, coffee plants, virgin forests, internal roads) and describes them as complementary, integrated, and fundamental for the functioning of modern coffee and agricultural companies, valorizing their large economic potential in the present and in the future (Muaze, 2015_______. Novas considerações sobre o Vale do Paraíba e a dinâmica Imperial. In: MUAZE, Mariana; SALLES, Ricardo (Org.) O Vale do Paraíba e o Império do Brasil nos quadros da segunda escravidão. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras, 2015.). For this, Marc Ferrez privileged long distance shots, horizontal and centralized framing, lower and middle planes which highlighted the ample limits and the topography of the landscape, as van be seen in the example in Figures 4 and 6. The solution found was suited to the landscape views, using a representation resource that appears in other works and which permitted an overall vision highlighting the central object: the coffee plantation and its surrounds (Carvalho, 1998CARVALHO, Vânia Carneiro de.A representação da Natureza na pintura e na Fotografia Brasileiras do Século XIX. In: FABRIS, Annateresa (Org.)Fotografia: usos e funções no século XIX. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998. p.199-231.). As a result, the plantation as a constructed landscape became an object of aesthetic appreciation.

Campo Alegre Plantation, Valença. Marc Ferrez, 1880s. Gilberto Ferrez Collection, IMS.

Antinhas Plantation, Bananal. José de Lima, oil on canvas, nineteenth century. Private collection of the Almeida/Vallim Family. Available at the site of Lahoi/UFF.

Santo Antônio do Paiol Plantation, Valença. Marc Ferrez, 1880s. Gilberto Ferrez Collection, IMS.

In relation to the theme of the ‘functional quadrilateral,’ the visual representation of plantations presented by Ferrez is in harmony with other artistic inscriptions of the period, such as the oil paintings of Georg Grimm, Nicolau Fachinetti, and José de Lima, and the writings of foreign travelers who left records about the region (Marquese, 2007_______. A paisagem da cafeicultura na crise da escravidão: as pinturas de Nicolau Facchinetti e Georg Grimm. Revista do IEB, São Paulo, n.44, p.55-76, fev. 2007. Disponível em: http://www.revistas.usp.br/rieb/article/viewFile/34562/37300.

http://www.revistas.usp.br/rieb/article/...

). The picture of the Antinhas plantation, located in Bananal, painted by José de Lima, and the narrative which the Portuguese writer Augusto Emílio Zaluar produces of the Ribeirão do Frio plantation, belonging to Commander José de Souza Breves, in Piraí, are excellent examples of how the visual composition prepared by Ferrez was in harmony with the visual production of the epoch and focused on plantations as places of production, order, and wealth:

Surrounded by a horizon of mountains whose shape is easily drawn, the spacious white house looms within an area of 311 spans of circumference! It is the biggest I have seen. This immense square is enclosed by the slave quarters, mill, and other workshops, which form a large citadel entered by two large lateral gateways. The slave quarters, all whitewashed and uniformly constructed, highlight, as well as the house, the various greens of the forest, and give this property a new and pleasant aspect... It is a small town, where many branches of industry are cultivated and all levels of labor are put into movement. (Zaluar, 1859, p. 29)

As can be noted, in Ferrez’s picture listed for the ‘functional quadrilateral’ theme, the coffee drying yard appears as an element aggregating the large coffee complex. Initially constructed on clay, the land was paved (stone or tarmac) in the second half of the nineteenth century. Around it was the buildings used for coffee machinery (wagons, pulpers, hulling machines and ventilators, amongst others), the storage bins, the large house, and the slave quarters. The latter were built in the Paraíba Valley in a line or in a square, with the square becoming ever more frequent from the 1840s onwards, for greater control over the slaves (Marquese, 2005MARQUESE, Rafael de Bivar. Moradia escrava na era do tráfico ilegal: senzalas rurais no Brasil e em Cuba, 1830-1860. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v.13, n.2, p.165-188, jul.-dez. 2005. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-47142005000200006.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

, p. 168). Facing the yard, the square shaped slave quarters were fundamental to give the connotation of the ‘large citadel’ cited by Zaluar, reinforced in the paintings and recurrent in Ferrez’s photographs.

In technical terms, the immensity with which the constructions were represented by Ferrez for theme 1 valorized productive capacity, technology, and the territorial expansion of the properties chosen, demonstrating all their economic potential in the present and in the future. To give the same effect, when possible Ferrez also included the available external machinery, for example wagons on rails for the internal transport of the product (Figure 1) or the system of suspended ducts for the removal and washing of beans. The Paraíba Valley was thus represented as a region with a solid and lasting agricultural structure, reinforcing its identity as a major global exporter of coffee, and demarcating its means of insertion in modern society.

For theme 2, ‘coffee harvest,’ the visual representation was constructed in two distinct forms. In the first, the intention was to take into account the vastness of the plantation and the quantity of workers, showing the coffee plantations as a space for production and abundant work (Figure 7). In the image, as well as in the others related to the ‘functional quadrilateral’ theme, the photographic language was one of views and panoramas, Ferrez’s specialty. For this he used long distance shots, presenting a telescopic register of its references. The effect extended human presence, and undermined the importance of individual experiences, and mimetized the slaves in the environment portrayed. The (natural or constructed) landscape was privileged instead of man, with the clear intention of showing the grandeur of the buildings and the landscapes, based on the smallness of the human scale.

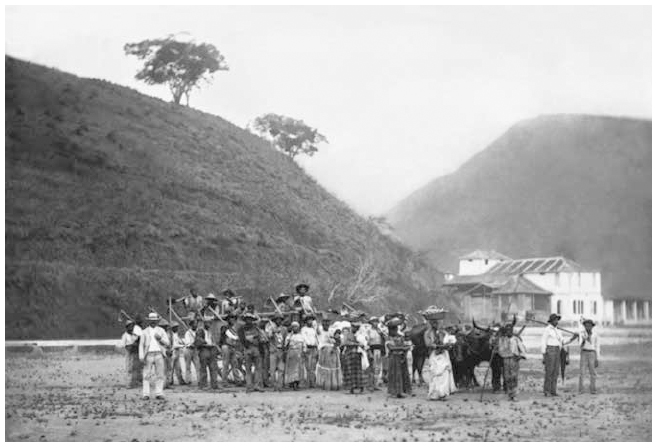

However, the theme ‘coffee harvest / coffee plantation’ was also portrayed in another form, quite different from the panoramic perspective already mentioned. In this, to the contrary, the focus of the image is on the historic subjects doing the harvesting. The medium shot was more valued and agents appeared, with the majority carrying work instruments, commonly baskets, sieves, and ladders. The visual language used was notably of the ‘black types,’ an old acquaintance of nineteenth century photographers, including Marc Ferrez, and which met the taste of a national and international clientele.

In Figures 8 and 9 Ferrez made similar technical choices in terms of shot, distance, framing, and lighting. The theme of the coffee harvest is also the same, as well as the desire to register a form of labor that in a short time would be gone: slave labor. The ‘human type’ constructed in both images is the slave working in the fields. What strongly differentiates the two portraits is that the historic subjects posed for the scene. They exhibited distinct postures, looks, and attitudes, which gives a specificity to each of the images and actors. In Figure 8, the two slaves do not look at the lens of the photographer and pretend that they have been caught in the act of their work, as if they had not noticed the presence of Ferrez, so strange to that environment of daily toil. In Figure 9, eight out of ten subjects portrayed look at the camera. Together they give the impression that they had stopped working for the photographic record. There are two women and eight men, some with Africanized turbans, who form a slave gang accompanied by their overseer, the only person of mixed blood in the photo to be located in the second rank, in a way that it is hard to notice. Whether intentionally or not, Ferrez immortalized in this and other images from the series, the form of labor called the gang system, in which slaves belonged to a small group supervised by an overseer who set the rhythms and cadence of daily work to achieve the productivity targets.3 3 The gang system, a system of organizing slave labor in shifts, mostly used in the Paraíba Valley, was different from the task system implemented in the South of the United States, in which workers had individual tasks to be fulfilled in a determined period.

From the tension between nostalgia for a slaveholding past to be immortalized and a future which pointed to the perspective of belonging to modern nations, Ferrez opted for ‘pacified slavery,’ in which the marks of coercion and violence carved on the bodies of the individuals enslaved were purposefully outside of or imperceptible in the figuration space of the photos (Figures 8 and 9). The evidence of violence - such as scars, burns, broken limbs, branding marks, and health problems -, so common in the descriptions of newspaper announcements and inventories, were not shown in the images. To the contrary, the visual representation constructed denoted a ‘pacified slave,’ running through all the images of the series and who was central in Ferrez’s narrative, announced in the perspective of the slaveholding world. One of the artifices in the factory of this representation of the real was the absence of all and any objects - such as slave collars, whips, trunks, cages, masks, irons - which could indicate the aggression and abuse experienced by captives in daily life. An extemporaneous reality, a world outside the world, was thus constructed, where slaves appeared stripped of the signs of their slavery and the forms of resistance to it.

Taken with technical mastery, the images studied were in harmony with the discourse of the dominant class in the Empire to who they were addressed. Their great capacity for circulation, consumption, and agency was based on the dual effect they produced. On the one hand, they enchanted foreign observers, accustomed to the language of souvenir photos, avid to get to know a distant reality which, having expropriated the marks of violence, aimed to emphasize the exoticism of those people, the grandeur of the territory, and the exuberance of nature. On the other, it sought to maintain everything in its place, preserving the master-slave hierarchy and seeking to represent the reality of slavery in the Paraíba Valley in a harmonious and orderly manner, protected from the political and social conflicts about the slavery question which exploded throughout the Empire in the 1880s (Machado, 2010MACHADO, Maria H. O Plano e o Pânico: os movimentos sociais na década da Abolição. São Paulo: Edusp, 2010.). For this, Ferrez produced a representation of slavery without violence, “a portrait of the black for white consumption,” very comfortable for the owners of power.

However, the photographic act involves multiple actors and intentions. It “assumes consent, a tacit acceptance by the person photographed of the rules of the game of representation. At the same time that they are seen, the photographed person exhibits themselves, assuming a pose resulting from negotiation” (Mauad, 2000MAUAD, Ana Maria. As fronteiras da cor: imagem e representação fotográfica na sociedade escravista imperial. Locus, Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, v.6, n.2, p.83-98, 2000. Disponível em: https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus/article/view/2363.

https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus...

, p. 97). In this “returned look” of photographed slaves there appears the indications of their pain, labor, expropriation, and sadness - in short, their humanity. Their eyes and bodies speak about their enslavement and make us think about the personal and collective histories experienced within the second slavery which in a short time would collapse (Tomich, 2011TOMICH, Dale. Sob o prisma da escravidão: trabalho, capitalismo e economia mundial. São Paulo: Edusp, 2011.). While Ferrez’s solution for the tensions between past and future, between the space of experience and the horizon of expectation (Koselleck, 2006KOSELLECK, Reinhart. Futuro passado: contribuição à semântica dos tempos históricos. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto; Ed. PUC-RJ, 2006.), was the construction of the visual narrative of ‘pacified violence,’ it did not count on the connivance of those men and women who, when being represented, could not remove what had identified them since birth, the condition of captive.

The themes ‘departure for work’ and ‘oxcart / transport’ are quite significant in the analysis of the ‘returned look’ of enslaved subjects, since human presence composes 100% of these images.

The image in evidence is constructed through the overseer (first on the left counting from the right) and slave hierarchy. Slightly in front, the former was the only man to use shoes, a symbol of liberty in imperial society. In art, as in the life of the individuals represented there, the relations of slavery fulfilled the role of separating and maintaining hierarchy. The tarmacked yard for drying coffee and the slave quarters in a line covered with roof tiles directs the eye to the technological advances introduced in the Valley and the solidity of that rural complex. In turn, the conditions of the slave dwellings, arranged in cubicles, with only one doorway and facing the yard, were minimized by the large volume of people in front of the construction. In the upper part of the photograph worn out and eroded soil can be seen on the hills, highlighting the need for new fertile lands from time to time to maintain production high (Stein, 1961STEIN, Stanley. Grandeza e decadência do café no vale do Paraíba. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1961.).

Profiled in front of the slave quarters, men, women, and children of different ages marked their places in the representational space based on what was dearest to them: their families. The children position themselves alongside their mothers, fathers, and grandparents. In this case, the visual narrative and the positions chosen confirm the existence of multiple familial and affective relations in slave communities, as the historiography has widely shown (Florentino; Góes, 1997FLORENTINO, Manolo; GÓES, José Roberto. A paz das senzalas. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1997.; Slenes, 1999SLENES, Robert. Na senzala uma flor. Campinas: Ed. Unicamp, 1999.; Salles, 2008SALLES, Ricardo. E o Vale era escravo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2008.). In the scenes portrayed (Figures 10 and 11) it is possible to see babies in the arms of their slave mothers, in straw baskets, tied to bodies in the African fashion, or children holding on to the skirts of their parents, a gesture which perhaps indicates apprehension in relation to an act that was not at all common in the daily life of plantations: posing for a photo. Men were a majority of the workers portrayed. Many carried baskets, scythes, hoes, sieves, sticks, and other agricultural tools. The ages of the slaves was very varied, with a considerable number of children and old people appearing, legitimating what Ricardo Salles has called ‘mature slavery,’ since the Fluminense Paraíba Valley had achieved stability in the slave birth rate in the 1860s, which guaranteed it labor even after the end of the slave trade in 1850 (Salles, 2008SALLES, Ricardo. E o Vale era escravo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2008.).

Leaving for the coffee harvest. Marc Ferrez, 1880s. Col. Thereza Christina Maria, BN.

In Figures 10 and 11 the command seems to have been for the slaves to face the photographer’s lens, although it can be perceived that not all those portrayed opted to obey it. For the theme ‘leaving for work’ there is a preference for mid-range and short distance shots, as well as the emphasis on the representation of slaves in groups, the profusion of work tools in the possession of captives, and the highlighting of slave-owners or overseers when present in the representational space. In relation to the slave-owners and overseers, the series analysis demonstrated that they appeared in 12 of the 65 imagens (18% of the total), always in the themes ‘functional quadrilateral’ and ‘leaving for work.’ The pose assumed places them in an outstanding place, as also occurs with the artifacts carried. In the case of the slave-owners, these were riding boots, umbrellas, Panama hats, top hats, canes, and well-cut clothes, which acted as signs of power differentiating them from the mass of slaves and occasional poor free workers recorded. To the contrary of the slaves, for the slave-owners the act of being photographed was customary and was part of the habitus of the ruling class in the Empire, in other words, it was of a second nature, shared by the individuals who composed the ‘best families’ (Elias, 1993ELIAS, Norbert.Processo civilizador. São Paulo: JZE, 1993. v.I e II.; Muaze, 2008_______. As memórias da Viscondessa: família e poder no Brasil Império. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2008.). It can also be noted that women from this group do not appear in the photographs analyzed. This choice silenced the role of women in the functioning of plantations, reinforcing the generation of wealth as a male and patriarchal task, and affirmed this as a visual project which emphasized the productive universe rather than the domestic or family sphere in which women had greater autonomy (Mauad; Muaze, 2004_______.; MUAZE, Mariana. A escrita da intimidade: história e memória no diário da viscondessa do Arcozelo. In: GOMES, Ângela de Castro (Org.) Escrita de si, escrita da história. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. FGV, 2004.).

By choosing ‘leaving for work’ as one of the four themes of his series about the Paraíba Valley, Marc Ferrez immortalized a daily act also described by numerous foreign travelers, in which every morning, at the sound of a bell, male and female slaves were paraded in front of the slave quarters to be counted (Figure 10), receive food mostly consisting of coffee, manioc, and corn, get their work tools, and form the so-called ‘gangs’ which left accompanied by their respective overseers for their extenuating toil. As the lands closest to the functional quadrilateral were already mostly eroded and with diminished productivity in the 1880s, the slave gangs moved to the coffee plantations on foot or on oxcarts, as shown in Figure 11. Both records also had a nostalgic tone which sought to materialize in images a time which - as is known - would shortly collapse.

The representational key of the ‘human types’ was also present in the image of the ‘oxcart / transport’ theme, in which its agents appear involved with the productive activity of driving the carts. The reference is both the slave who drives the animals and the means of transport. All the types portrayed are men, which evidences a given division of gender in in relation to the implementation of certain activities in plantations, corroborated by the analysis of the inventories of the mega-property holders from the region. In both cases, the pose chosen points to the importance of the slaves to the task being carried out. It is interesting to note that Figure 12 is the best of a micro-set of three images and for this was chosen for reproduction with the photographer’s signature, sale, and greater publicity by Marc Ferrez & Cia. In the other two photographs, someone always turns their head, slipping away from the ideal representation. Thus, as in the portraits from the urban studios or travelling professionals who circulated in the Paraíba Valley in the nineteenth century, the pose and the different positioning in the figuration space were essential for the construction of the representation desired both by the photographer and the person photographed, notwithstanding the hierarchy of power existing between them.

Figure 14 belongs to another micro-set of four glass negatives. In this, two of the photographs from the ‘functional quadrilateral’ theme have a very close angle, distance, lighting, and camera direction and, although they dialogue strongly with the aesthetic of nineteenth century landscapes and views, they allow the visualization of the human types referenced there. It is practically the same photographic intention. In it the immense coffee yard was highlighted against the background of the large house, the Imperial Palms, and the nature and topography of the plantation. Numerous slaves appear, distributed according to gender: women and children with straw baskets and men with shovels and hoes. Their various poses sought to convey an atmosphere of tranquility, with children beside their mothers and pairs talking, but also of work, with slaves carrying sacks and baskets with coffee. However, the artificiality of both is denounced by details: the good clothes worn by the slaves (the use of jackets and blazers used on festive days or when it was cold), the rigidity of the bodies, the embarrassed gestures of children and the bewilderment in the faces of some who, looking straight at the camera, let it appear how much the act of posing was strange to their daily life of extenuating labor.

The few alterations between the two images prove the strength of the pose in nineteenth century visual culture. One photograph is almost a repetition of the other, except the lower head of the slave-owner at the exact moment of the first register. Like the ‘spot the difference’ game, it is possible to perceive that it is not just this. There are other alterations between the constructed scenes. Various slaves change the direction of their heads, their faces, their bodies. Some turn their backs, others take small steps forwards or change places, such as the slave with the baby who appears in the foreground, on the edge of the yard, looking towards the camera in the first photo, and who turns her back, hiding her face, in the image reproduced here. These acts explain that it was not always possible for the photographer to exert control and the slaves approved these intrinsic limits on the photographic act by looking for their own expression.4 4 Unfortunately, it was not possible to reproduce the other image describe because it was being repaired. Some of the photos analyzed in this series were part of the exhibition Emancipation, inclusion, and exclusion. Challenges of the Past and Present –photographs from the collection of the Moreira Salles Institute, under the curatorship of Maria Helena Machado, Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, and Sergio Burgi.

By way of conclusion, it can be said that slavery by way of photographic representation appears in Ferrez’s images as a ‘world outside of the world,’ an artificial creation, extemporaneous to the reality of the violence and coercion necessary to its own existence. What defines this artificiality is the aesthetic use of ‘human types’ and views/landscapes for the visual construction of an ordered slavery, without violence, ‘pacified’ and alien to all the social pressures existing on the question of slavery in the Paraíba Valley and other parts of the Empire. Whether mimetizing the presence of slaves in the natural landscape or in the coffee complex, or portraying the ‘black types’ in daily conditions where they appear carrying out tasks - harvesting, planting, leaving for the fields, driving oxcarts -, valorizing the integration of nature and civilization, what was intended was to eternalize the world of slavery and a form of work which would shortly no longer exist. But it was not only this. This relationship with the past created tensions with the future to the extent that shortly beforehand slavery had been the mainspring which propelled the entrance of Brazilian into modern society. Once abolished other possibilities had to be shown. In the case of the imagens analyzed, the perspective returned to the productive space of the coffee complex, to these buildings and the natural landscape which, once monumentalized, justified the continuity of Brazil in the civilized world through its agro-exporting role of primary foodstuffs.

The artificiality of the visual discourse of a ‘pacified slavery’ for the 1880s is even more evident when contextualized with other printed sources and the research of historians of abolition who point to the fierce struggle of abolitionists and the radicalization of slave actions at that moment, including the insubordination of the rules of work, the abandonment of plantations, occupation of waste lands, and individual and mass flights (Machado, 2010MACHADO, Maria H. O Plano e o Pânico: os movimentos sociais na década da Abolição. São Paulo: Edusp, 2010.). Notwithstanding the context of the struggles for abolition in which the images are inserted, Ferrez’s photographs are silent about all and any imminent conflict. Rather, he dialogued strongly with the discourse of the slave-owners, ignoring the drastic changes in the constituted social organization, and not recognizing other social agents in dispute which aimed to construct a new reality through the end of slavery.

However, not everything can be controlled in the photographic act. By letting themselves be photographed, the slaves also left their mark in the figuration space of the photo by constituting their own self-image through gestures, objects carried, clothes, positioning, and subtle looks. It is them who speak about the slave family, the division of tasks according to gender, the influence of African culture, the experience with children in the work space, and maternity in the space of captivity, themes never touched by Ferrez, but which can be traced by historians. In this way, while Marc Ferrez’s images strongly complied with the political function of shaping and forming a given memory about slavery of interest to the ruling class in the Empire, they also provide information about important captive experiences when the ‘returned look’ of the photographed slaves is analyzed.

This article also demonstrated that the social circuit of the images produced by Marc Ferrez was that of the universal exhibitions and souvenir photos. However, many of them were distributed as postcards in the first decades of the Republic, and others are still exhibited in photography books or school books. Now understood in their context of production, circulation, and consumption, these registers gain the meaning of slave-owners’ visual discourse about slavery, which minimizes their power of describing as ordered and peaceful an extremely violent, authoritarian, unequal, and hierarchical world, which the slaves and other social agents fought so much to turn upside down. And they succeeded.

REFERÊNCIAS

- AZEVEDO, Paulo César; LISSOVSKY, Maurício.Escravos brasileiros do século XIX na fotografia de Christiano Jr. São Paulo: Libris, 1988.

- BRIZUELA, Natalia.Fotografia e Império: paisagens de um Brasil moderno. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras; IMS, 2012.

- CARVALHO, Vânia Carneiro de.A representação da Natureza na pintura e na Fotografia Brasileiras do Século XIX. In: FABRIS, Annateresa (Org.)Fotografia: usos e funções no século XIX. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998. p.199-231.

- CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da.Olhar escravo, ser escravo. In: NEGRO de corpo e alma. (Catálogo, “Mostra do Redescobrimento”, org. Emanoel Araujo).São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo; Associação Brasil 500 Anos Artes Visuais, 2000.

- ELIAS, Norbert.Processo civilizador. São Paulo: JZE, 1993. v.I e II.

- ERMAKOFF, George.O negro da Fotografia Brasileira do século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: Casa Editorial G. Ermakoff, 2004.

- FABRIS, Annateresa. A invenção da fotografia: repercussões sociais. In: _______. Fotografia: usos e funções no século XIX. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998.

- FERREIRA, Marieta de Moraes. A crise dos comissários de café do Rio de Janeiro. Niterói: ICHF/UFF, 1977.

- FERREZ, Gilberto. O Rio de Janeiro do fotógrafo Marc Ferrez. 2.ed. São Paulo: Libris, 1985.

- FLORENTINO, Manolo; GÓES, José Roberto. A paz das senzalas. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1997.

- HARDMAN, Francisco Foot. Trem-fantasma: a ferrovia Madeira-Mamoré e a modernidade na selva. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2005.

- KOSELLECK, Reinhart. Futuro passado: contribuição à semântica dos tempos históricos. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto; Ed. PUC-RJ, 2006.

- KOSSOY, Boris. Dicionário histórico-fotográfico brasileiro: fotógrafos e ofício da fotografia no Brasil (1833-1910). São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Sales, 2002.

- KOUTSOUKOS, Sandra Sofia Machado. Negros no estúdio do fotógrafo: Brasil, segunda metade do século XIX. Campinas: Ed. Unicamp, 2010.

- LAGO, Pedro Corrêa do. Marc Ferrez nas coleções do Quai d’Orsay. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 2001.

- LOURENÇO, Thiago C. P. O Império dos Souza Breves nos Oitocentos: política e escravidão nas trajetórias dos Comendadores José e Joaquim de Souza Breves. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) - Universidade Federal Fluminense. Niterói, 2010.

- MACHADO, Maria H. O Plano e o Pânico: os movimentos sociais na década da Abolição. São Paulo: Edusp, 2010.

- MARQUESE, Rafael de Bivar. Moradia escrava na era do tráfico ilegal: senzalas rurais no Brasil e em Cuba, 1830-1860. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v.13, n.2, p.165-188, jul.-dez. 2005. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-47142005000200006

» http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-47142005000200006 - _______. A paisagem da cafeicultura na crise da escravidão: as pinturas de Nicolau Facchinetti e Georg Grimm. Revista do IEB, São Paulo, n.44, p.55-76, fev. 2007. Disponível em: http://www.revistas.usp.br/rieb/article/viewFile/34562/37300

» http://www.revistas.usp.br/rieb/article/viewFile/34562/37300 - _______.; TOMICH, Dale. O Vale do Paraíba escravista e a formação do mercado mundial do café no século XIX. In: MUAZE, Mariana; SALLES, Ricardo. O Vale do Paraíba e o Império do Brasil nos quadros da segunda escravidão. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras; Faperj, 2015.

- MATTOS, Ilmar. O Tempo Saquarema. Rio de Janeiro: Access, 1986.

- MAUAD, Ana Maria. As fronteiras da cor: imagem e representação fotográfica na sociedade escravista imperial. Locus, Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, v.6, n.2, p.83-98, 2000. Disponível em: https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus/article/view/2363

» https://locus.ufjf.emnuvens.com.br/locus/article/view/2363 - _______. Poses e flagrantes. Niterói: Eduff, 2008.

- _______. Ver e conhecer: o uso da fotografia nos Anais do MHN. Anais do Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, v.36, p.117-142, 2004.

- _______.; MUAZE, Mariana. A escrita da intimidade: história e memória no diário da viscondessa do Arcozelo. In: GOMES, Ângela de Castro (Org.) Escrita de si, escrita da história. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. FGV, 2004.

- MENESES, Ulpiano T. Bezerra de. A fotografia como documento: Robert Capa e o miliciano abatido na Espanha: sugestões para um estudo histórico. Tempo, Rio de Janeiro, n.14, p.131-151, s.d.

- MUAZE, Mariana. A escravidão no Vale do Paraíba pelas lentes do fotógrafo Marc Ferrez. In: CARVALHO, José Murilo de; BASTO, Lúcia. Dimensões e fronteiras do Estado Brasileiro no Oitocentos. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Uerj, 2014.

- _______. As memórias da Viscondessa: família e poder no Brasil Império. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2008.

- _______. Novas considerações sobre o Vale do Paraíba e a dinâmica Imperial. In: MUAZE, Mariana; SALLES, Ricardo (Org.) O Vale do Paraíba e o Império do Brasil nos quadros da segunda escravidão. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras, 2015.

- NEVES, Margarida de Souza. As vitrines do progresso. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. PUC, 1986.

- PESAVENTO, Sandra J. Exposições universais, espetáculo da modernidade do século XIX. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1997.

- SALLES, Ricardo. E o Vale era escravo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2008.

- SLENES, Robert. Na senzala uma flor. Campinas: Ed. Unicamp, 1999.

- SONTAG, Susan. Sobre fotografia. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2004.

- STEIN, Stanley. Grandeza e decadência do café no vale do Paraíba. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1961.

- SÜSSEKIND, Flora. O Brasil não é longe daqui: o narrador, a viagem. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1990.

- SWEIGART, Joseph Earl. Financing and making Brazilian exportation agriculture: the coffee factors of Rio de Janeiro, 1850-1888. Dissertation (Ph.D. in History) - University of Texas. Texas, USA, 1980.

- TOMICH, Dale. Sob o prisma da escravidão: trabalho, capitalismo e economia mundial. São Paulo: Edusp, 2011.

- TURAZZI, Maria Inês. Marc Ferrez. São Paulo: CosacNaify, 2000.

- _______. Poses e trejeitos: a fotografia e as exposições na era do espetáculo. Rio de Janeiro: Funarte; Rocco, 1995.

- VASQUEZ, Pedro Karp. O Brasil na fotografia oitocentista. São Paulo: Metalivros, 2003.

- ZALUAR, Augusto E. Peregrinações pela província de São Paulo (1860-1861). São Paulo: Edusp; Itatiaia, 1975.

Documents

-

Breve notícia sobre a primeira exposição do Café do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Clube da Lavoura e do Comércio, 1882 (document belonging to the IHGB Archive).

-

Le Brésil à l’Exposition Internacionale de St. Petersbourg. St. Petersbourg: Imprimerie Trenké et Fusnot, 1884 (document belonging to the IHGB Archive).

-

Folha Nova, 1 jun. 1884. Available at: http://www.hemerotecadigital.bn.br; Accessed on: 1 maio 2013.

NOTES

-

1

This research received support from the Faperj Young Scientist of our State and the CNPq Human Science Call for Research Proposals. I would like to thank the Moreira Salles Institute, the National Library, the Museu Paulista, and the National History Museum for the freely ceding the images used in this article.

-

2

The Center of Agriculture and Commerce was founded to “resist this anarchy which has been created, to determine exactly the most useful course for the national economy, establish on solid foundations its industry, widen the circle of commercial relations, entice the esteem of other countries, affirming it in the conveniences of exchange, and thereby constitute a rich, prosperous, and respected state, this is primordial aim of our association” (CLC, 1882). Among its principal members were coffee planters and factors, such as: Honório Ribeiro; Hermano Jopert; the Baron of Quartim; the Baron of Araújo Ferraz; Eduardo Rodrigues Cardoso Lemos; Carlos Augusto Miranda Jordão; Joaquim de Mello Franco; Honório de Araújo Maia; Bruno Ribeiro; João Valverde de Miranda; the Baron of São Clemente, and Joaquim da Costa Ramalho Ortigão. Its principal base of political and economic support were the municipal Agricultural Clubs (Clubes da Lavoura) which, through an organizational network structured in different locations, acted to maintain the constituted slave-holding order. However, with the growth of the abolitionist movement in the 1880s, there was a radicalization of the local Agricultural Clubs and many began to operate with armed militias to protect plantations, destroy quilombos, and intimidate abolitionists (FERREIRA, 1977FERREIRA, Marieta de Moraes. A crise dos comissários de café do Rio de Janeiro. Niterói: ICHF/UFF, 1977.; SWEIGART, 1980SWEIGART, Joseph Earl. Financing and making Brazilian exportation agriculture: the coffee factors of Rio de Janeiro, 1850-1888. Dissertation (Ph.D. in History) - University of Texas. Texas, USA, 1980. ; MACHADO, 2010MACHADO, Maria H. O Plano e o Pânico: os movimentos sociais na década da Abolição. São Paulo: Edusp, 2010.).

-

3

The gang system, a system of organizing slave labor in shifts, mostly used in the Paraíba Valley, was different from the task system implemented in the South of the United States, in which workers had individual tasks to be fulfilled in a determined period.

-

4

Unfortunately, it was not possible to reproduce the other image describe because it was being repaired. Some of the photos analyzed in this series were part of the exhibition Emancipation, inclusion, and exclusion. Challenges of the Past and Present –photographs from the collection of the Moreira Salles Institute, under the curatorship of Maria Helena Machado, Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, and Sergio Burgi.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

27 Apr 2017 -

Date of issue

Jan-Apr 2017

History

-

Received

07 May 2016 -

Accepted

14 Sept 2016