Abstract:

A comprehensive cohort study including an entomological surveillance component can contribute to our knowledge of clinical aspects and transmission patterns of arbovirosis. This article describes the implementation of a populational-based birth cohort study that included an entomological surveillance component, and its associated challenges in a low-income community of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The participants were recruited in two periods: from 2012 to 2014, and from 2015 to 2017. The children had scheduled pediatric consultations and in case of fever. Epidemiological, clinical data and biological samples were collected at pediatric visits. Active febrile surveillance was performed by telephone calls, social networking, message apps, and household visits. A total of 387 newborns and 332 new children were included during the first and second recruitment periods, respectively. By July 2017, there were 451 children on follow-up. During the study, 2,759 pediatric visits were performed: 1,783 asymptomatic and 976 febrile/rash consultations. The number of febrile or rash consultations increased 3.5-fold after the use of media tools for surveillance. No temporal pattern, seasonality or peak of febrile cases was observed during the study period. A total of 10,105 adult mosquitoes (including 3,523 Aedes spp. and 6,582 Culex quinquefasciatus) and 46,047 Aedes eggs were collected from households, schools, and key sites. Although challenging, this structured sentinel populational-based birth cohort is relevant to the knowledge of risks and awareness of emerging pathogens.

Keywords:

Arbovirus Infections; Cohort Studies; Maternal and Child Health; Vector Control

Resumo:

Estudos de coorte com um componente de vigilância epidemiológica podem contribuir para nosso conhecimento dos aspectos clínicos e dos padrões de transmissão de arboviroses. Este artigo descreve a implementação de um estudo de coorte de nascimento de base populacional que incluiu um componente de vigilância entomológica e desafios relacionados numa comunidade desfavorecida do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Os participantes foram recrutados em dois períodos: de 2012-2014 e de 2015-2017. As crianças tiveram consultas pediátricas agendadas e em caso de febre. Dados epidemiológicos, clínicos e amostras biológicas foram coletadas nas visitas pediátricas. A vigilância ativa febril foi realizada por meio de ligações telefônicas, redes sociais, aplicativos de mensagens e visitas domiciliares. Um total de 387 recém-nascidos e 332 novas crianças foram incluídas durante o primeiro e segundo períodos de recrutamento, respectivamente. Em Julho de 2017, havia 451 crianças em seguimento. Durante o estudo, foram realizadas 2.759 visitas pediátricas: 1.783 assintomáticas e 976 consultas por febre/exantema. O número de consultas por febre ou exantema aumentou 3,5 vezes após uso de ferramentas de mídia para vigilância. Nenhum padrão temporal, sazonalidade ou pico de casos de febre foi observado durante o período do estudo. Um total de 10.105 mosquitos adultos (incluindo 3.523 Aedes spp. e 6.582 Culex quinquefasciatus) e 46.047 ovos foram coletados de domicílios, escolas, e pontos estratégicos. Apesar dos desafios, esta coorte de nascimento sentinela de base populacional é relevante para o conhecimento dos riscos e de patógenos emergentes.

Palavras-chave:

Infecções por Arbovírus; Estudos de Coortes; Saúde Materno-Infantil; Controle de Vetores

Resumen:

Un estudio completro de cohorte que incluya una vigilancia entomológica puede contribuir a nuestro conocimiento de aspectos clínicos y patrones de transmisión de arbovirosis. Este artículo describe la implementación de un estudio poblacional de cohorte de nascimientos que incluyó el componente de vigilancia entomológica y los desafios asociados en una comunidad desfavorecida de Río de Janeiro, Brasil. Los participantes fueron captados en dos periodos: de 2012 a 2014 y de 2015 a 2017. Los niños tenían fijadas consultas pediátrica regulares y por fiebre. Durante las visitas pediátricas, se recogieron datos epidemiológicos y clínicos, así como muestras biológicas. Se realizó una vigilancia activa de la fiebre mediante llamadas telefónicas, redes sociales, aplicaciones de mensajes, y visitas a domicilio. Un total de 387 recién nacidos y 332 nuevos niños fueron incluidos durante el primer y segundo período de reclutamiento, respectivamente. En julio de 2017 se había realizado un seguimiento a 451 niños. Durante el estudio, se realizaron 2.759 visitas pediátricas: 1.783 asintomáticas y 976 por fiebre/urgencias. El número de consultas por fiebre o urgencias aumentó 3.5-veces tras el uso de herramientas de comunicación para la viglancia. No se observaron patrones temporales, estacionalidad o casos de picos de fiebre durante el periodo de estudio. Un total of 10.105 mosquitos adultos (incluyendo 3.523 Aedes spp. y 6.582 Culex quinquefasciatus) y 46.047 huevos fueron recogidos de viviendas, escuelas, y lugares estratégicos. A pesar de los retos, esta cohorte de nacimiento estructurada y supervisada, basada en población es relevante para el conocimiento de los riesgos y la concienciación sobre patógenos emergentes.

Palabras-clave:

Infecciones por Arbovirus; Estudios de Cohortes; Salud Materno-Infantil; Control de Vectores

Background

Arbovirosis are arthropod-borne viral diseases considered a global health problem due to their significant morbidity in humans. The invasive and urban mosquito species Aedes aegypti can transmit the main relevant arbovirosis, such as yellow fever, dengue, Zika, and chikungunya 11. Donalisio MR, Freitas ARR, Zuben APBV. Arboviruses emerging in Brazil: challenges for clinic and implications for public health. Rev Saúde Pública 2017; 51:30.. Comprehensive cohort studies are needed to better understand clinical aspects, and transmission patterns of these arboviruses, particularly in places where all viruses co-circulate and might influence both the vector capacity and human immune responses.

Dengue is endemic in about 100 countries, with 3.2 million reported cases in 2015 22. World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/ (accessed on 10/Nov/2017).

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheet...

. In Brazil, dengue is an important cause of epidemics since the 1980s, chikungunya virus (CHIKV) emerged in 2014 33. Nunes MRT, Faria NR, de Vasconcelos JM, Golding N, Kraemer MU, de Oliveira LF, et al. Emergence and potential for spread of chikungunya virus in Brazil. BMC Med 2015; 13:102., and Zika virus (ZIKV) in 2015. Zika virus emergence and spread in Brazil - the congenital Zika syndrome and its consequences in neonate 44. Brasil P, Pereira JP, Moreira ME, Nogueira RMR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2321-34.,55. Campos GS, Bandeira AC, Sardi SI. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1885-6.,66. Lowe R, Barcellos C, Brasil P, Cruz OG, Honório NA, Kuper H, et al. The Zika virus epidemic in Brazil: from discovery to future implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15. pii:E96.,77. França GVA, Pedi VD, Garcia MHO, Carmo GMI, Leal MB, Garcia LP. Síndrome congênita associada à infecção pelo vírus Zika em nascidos vivos no Brasil: descrição da distribuição dos casos notificados e confirmados em 2015-2016. Epidemiol Serv Saúde 2018; 27:e2017473.,88. Alves LV, Paredes CE, Silva GC, Mello JG, Alves JG. Neurodevelopment of 24 children born in Brazil with congenital Zika syndrome in 2015: a case series study. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e021304. - have raised major concerns.

There are few clinical and epidemiological studies about arbovirosis in infants. Most published prospective dengue studies in neonates have been conducted in Southeast Asian countries 99. Pengsaa K, Luxemburger C, Sabchareon A, Limkittikul K, Yoksan S, Chambonneau L, et al. Dengue virus infections in the first 2 years of life and the kinetics of transplacentally transferred dengue neutralizing antibodies in thai children. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:1570-6.,1010. Chau TNB, Hieu NT, Anders KL, Wolbers M, Le Bich L, Lu Thi Minh H, et al. Dengue virus infections and maternal antibody decay in a prospective birth cohort study of Vietnamese infants. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:1893-900.,1111. Libraty DH, Acosta LP, Tallo V, Segubre-Mercado E, Bautista A, Potts JA, et al. A prospective nested case-control study of dengue in infants: rethinking and refining the antibody-dependent enhancement dengue hemorrhagic fever model. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000171.,1212. Anders KL, Nguyen NM, Van Thuy NT, Hieu NT, Nguyen HL, Hong Tham NT, et al. A birth cohort study of viral infections in Vietnamese infants and children: study design, methods and characteristics of the cohort. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:937.. In Vietnam, prevalent infectious diseases as dengue, influenza, and rotavirus were studied in a cohort of neonates 1212. Anders KL, Nguyen NM, Van Thuy NT, Hieu NT, Nguyen HL, Hong Tham NT, et al. A birth cohort study of viral infections in Vietnamese infants and children: study design, methods and characteristics of the cohort. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:937.. In a pediatric cohort of Nicaragua, children were followed up until they were 14-years-old for an overall incidence of 16.1 cases of dengue/1,000 person-years. Most of the primary dengue cases occurred in children under 6-years-old 1313. Gordon A, Kuan G, Mercado JC, Gresh L, Avilés W, Balmaseda A, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: incidence of inapparent and symptomatic dengue virus infections, 2004-2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7:e2462.,1414. Kuan G, Gordon A, Avilés W, Ortega O, Hammond SN, Elizondo D, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: study design, methods, use of information technology, and extension to other infectious diseases. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 170:120-9.. In Brazil, a birth cohort study was carried out in Recife showing a cumulative incidence of dengue of 10% in infants in their first year of life 1515. Braga C, Albuquerque MFPM, Cordeiro MT, Castanha PMS, Ramesh A, Alexander N, et al. Prospective birth cohort in a hyperendemic dengue area in Northeast Brazil: methods and preliminary results. Cad Saúde Pública 2016; 32:e00095815.. Prospective studies including both passive and active serological surveillance are important to estimate the incidence of arbovirosis and to guide control measures.

Focused efforts worldwide on mosquito vector control have not been very successful 1616. Haug CJ, Kieny MP, Murgue B. The Zika challenge. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1801-3.,1717. Maciel-de-Freitas R, Aguiar R, Bruno RV, Guimarães MC, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Sorgine MH, et al. Why do we need alternative tools to control mosquito-borne diseases in Latin America? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2012; 107:828-9.. Although most studies consider the household as the main default location of arboviruses, daycare spaces for young children and neighborhood key-sites (such as junkyards, thrift stores, factories, tire repair shops and garages) should also be included in epidemiological studies. Although these sites may contribute to a significant proportion of the overall mosquito population, they are not usually priority targets for vector surveillance and control 1818. Honório NA, Nogueira RMR, Codeço CT, Carvalho MS, Cruz OG, Magalhães MAFM, et al. Spatial evaluation and modeling of dengue seroprevalence and vector density in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009; 3:e545.,1919. dos Reis IC, Honório NA, Codeço CT, Magalhães MAFM, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Barcellos C. Relevance of differentiating between residential and non-residential premises for surveillance and control of Aedes aegypti in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Acta Trop 2010; 114:37-43..

In 2012, considering the epidemiological scenario in Brazil, the main objective of the study was to increase the knowledge about the prevalence of maternal antibodies and the kinetics of the maternal anti-DENV antibodies transplacental transference, essential to understand the dynamics of the disease incidence and to establish the optimal age for vaccination. Furthermore, we expected to contribute to the identification of asymptomatic cases and their role in disease transmission, which became even more challenging after the ZIKV emergence due to its serological cross-reactions with DENV.

This article aims to describe the implementation and characteristics of a populational-based birth cohort for the study of arbovirosis integrating entomological data in a low-income urban area in Rio de Janeiro. The laboratory investigation is not within the scope of this publication.

Methods

A prospective cohort study of 0-5-year-old children resident in Manguinhos - a low-income community in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil - began in May of 2012 and is ongoing. Manguinhos, with approximately 36,000 inhabitants, had, at the beginning of the study, one of the lowest Human Development Indices of the municipality (12nd in the ranking of 126 neighborhoods) 2020. Índice de Desenvolvimento Humano Municipal (IDH), por ordem de IDH, segundo os bairros ou grupo de bairros - 2000. http://portalgeo.rio.rj.gov.br/amdados800.asp?gtema=15 (accessed on 10/Nov/2017).

http://portalgeo.rio.rj.gov.br/amdados80...

. Primary care is delivered by two primary health-care facilities that coordinate the work of 13 family health teams 2121. Engstrom E, Fonseca Z, Leimann B. A experiência do território escola Manguinhos na atenção primária de saúde. http://andromeda.ensp.fiocruz.br/teias/sites/default/files/arquivo_nossa_producao/A%20Experiencia%20do%20Territorio%20Escola%20Manguinhos%20na%20Atencao%20Primaria%20de%20Saude.pdf (accessed on 13/Oct/20217).

http://andromeda.ensp.fiocruz.br/teias/s...

: the health center at Sergio Arouca National School of Public Health (ENSP)/Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) and Victor Valla Family Clinic.

The initial design of this prospective populational-based birth cohort for dengue ended at the age of 2 years. In 2014, the follow-up was extended to 5-years-old, in order to study the natural history of dengue in the children in this area. In 2015, we reopened the enrollment to compensate the dropout rate and to include in the study two other arboviruses, Zika, and chikungunya, already spreading in the city (study design is summarized in Figure 1).

Sample size

As there is no available data about incidence, and it varies substantially between epidemic and non-epidemic years, we estimated an incidence of 50%, conservatively, leading to a sample size higher than necessary (fixing the other variables). For the sample size calculation, a level of significance of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.8 was set, resulting in a sample of 383 newborns 2222. Lwanga S, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies - a practical manual. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/40062/1/9241544058_(p1-p22).pdf (accessed on 20/Oct/2016).

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665...

. Considering 25% of loss, we aimed to recruit 500 pregnant women. The sample size to reopen the enrollment has considered the lower incidence risk of dengue (0.08) in the two years (2013-2015) and an absolute error of 0.035. Losses of 32.5% over the same period were considered, resulting in approximately 700 children.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

The main eligibility criterion was to be assisted by the primary health care facilities. Newborns whose parents withdrew consent for infant participation at any time during the follow-up were excluded. Participants who moved from the study area were also excluded because they were no longer assisted by the primary health care facilities and would not represent the local incidence of arbovirosis.

1st recruitment: 2012-2014

From 2012 to 2014 the eligibility criteria were women in the third trimester of pregnancy enrolled in low-risk prenatal care at the primary health care facilities. Their offspring were automatically included in the study.

A standardized form to collect epidemiological and clinical data of pregnant women’s recruitment was applied. Blood samples from mothers collected at recruitment and at delivery were stored at -80ºC.

2nd recruitment: 2015-2017

From 2015 to 2017, the eligibility criteria were pregnant women at any gestational week. Newborns were included in the study after parental informed consent and had the same follow-up of any other children in the cohort.

Epidemiological and clinical data were registered in a similar form of the previous group (Supplementary Material 1: http://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/site/public_site/arquivo/suppl-e000239-18-1_2773.pdf). Blood and urine samples collected at every trimester and at delivery were stored at -80°C.

Since early 2016, children aged 0-5 years have been recruited to replace losses to follow-up.

Follow-up

At the primary health care facilities, questionnaires were applied by nurses, the material collection was performed by specialized technicians, while physical examinations and febrile consultations were performed by pediatricians.

Newborns that were included between 2012 to 2014 had a quarterly contact in the first year, biannual in the second year, and annual in the third, fourth and fifth years of follow-up. Newborns and children included between 2015 and 2017 had annual scheduled pediatric visits or febrile/rash visits.

Clinical history, physical examination, anthropometry, and demographic data (i.e., address and phone number) of infants were collected at each contact in a standardized form (Supplementary Material 2: http://cadernos.ensp.fiocruz.br/site/public_site/arquivo/suppl-e000239-18-2_2175.pdf). Blood samples were stored at -80°C.

We only considered a loss to follow-up if the child had no contact for one year. Children missing any scheduled contact were re-invited by phone, social networks, message apps or by household visits by the staff.

Febrile/rash surveillance

Passive and active febrile/rash cases surveillance was also included in the study protocol. Mothers could contact the study staff anytime in case of an infant’s fever or rash. Active surveillance of children was fortnightly by phone calls and household visits. Since 2014, the use of the most popular social network and message app (Facebook and WhatsApp) was implemented.

In case of fever or rash, a pediatric visit was scheduled within seven days of symptoms onset. The protocol included a clinical evaluation by a pediatrician and blood sample collection for complete blood count (CBC), dengue and chikungunya serological tests, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for dengue and Zika. Families were told to return for a consultation with the infant within 48 hours after the first febrile/rash visit for a clinical review and 14 days after the onset of symptoms for pairing serological tests. Children missing those return visits were invited to schedule it again by phone, social networks, and message apps or by home visits by the staff.

Entomological surveillance

Mosquitoes capture was performed weekly and started in February 2014 in the households and in May 2015 in schools and key-sites in the vicinity of the fever/rash cases within seven days after the symptomatic pediatric visit. Adult mosquitoes were collected using backpack aspirators 2323. Nasci R. A lightweight battery-powered aspirator for collecting resting mosquitões in the field. Mosq News 1981; 41:808-11. following febrile/rash notifications. Collections by aspiration took 15-20 minutes per site 2020. Índice de Desenvolvimento Humano Municipal (IDH), por ordem de IDH, segundo os bairros ou grupo de bairros - 2000. http://portalgeo.rio.rj.gov.br/amdados800.asp?gtema=15 (accessed on 10/Nov/2017).

http://portalgeo.rio.rj.gov.br/amdados80...

,2121. Engstrom E, Fonseca Z, Leimann B. A experiência do território escola Manguinhos na atenção primária de saúde. http://andromeda.ensp.fiocruz.br/teias/sites/default/files/arquivo_nossa_producao/A%20Experiencia%20do%20Territorio%20Escola%20Manguinhos%20na%20Atencao%20Primaria%20de%20Saude.pdf (accessed on 13/Oct/20217).

http://andromeda.ensp.fiocruz.br/teias/s...

,2222. Lwanga S, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies - a practical manual. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/40062/1/9241544058_(p1-p22).pdf (accessed on 20/Oct/2016).

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665...

,2323. Nasci R. A lightweight battery-powered aspirator for collecting resting mosquitões in the field. Mosq News 1981; 41:808-11.,2424. Honório NA, Silva WC, Leite PJ, Gonçalves JM, Lounibos LP, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Dispersal of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in an urban endemic dengue area in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003; 98:191-8.,2525. Consoli R, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Principais mosquitos de importância sanitária no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz; 1994.. A total of 45 ovitramps - consisting of a black plastic container filled with hay infusion and a wooden paddle - were placed weekly in schools from October 2015 to May 2016 to routinely collect mosquito eggs 2424. Honório NA, Silva WC, Leite PJ, Gonçalves JM, Lounibos LP, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Dispersal of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in an urban endemic dengue area in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003; 98:191-8.. Adults were carried on dry ice to the Sentinel Operational Unit for Mosquito Vectors (Nosmove/Fiocruz), where they were counted, sexed and identified according to the standard taxonomic key 2525. Consoli R, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Principais mosquitos de importância sanitária no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz; 1994.. Wooden paddles were collected weekly and inspected for the presence of eggs, which were counted and hatched at 25-28ºC and 80% humidity. Engorged and nonengorged females were stored in the freezer (-80°C) until tested 2626. Ayllón T, Campos RM, Brasil P, Morone FC, Câmara DCP, Meira GLS, et al. Early evidence for Zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1411-2.. All collection sites were geocoded using GPS. A structured questionnaire was developed to collect socioeconomic data of participants and environmental data of households.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was signed by each pregnant woman and by the children’s parents at the moment of recruitment and cohort extension. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the ENSP/Fiocruz (protocol number: 1.721.793, CAAE: 13202113.1.0000.5240).

Data analysis and statistical procedures

The descriptive analysis presented included the data available for the period between May 2012 and July 2017. Differences in mothers characteristics between groups of infants included and not included in the cohort follow-up were determined by Chi-square test. Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical package, version 3 (http://www.r-project.org) 2323. Nasci R. A lightweight battery-powered aspirator for collecting resting mosquitões in the field. Mosq News 1981; 41:808-11..

Results

The results presented here are the adherence of participants, children’s follow-up by the number of consultations, entomological surveillance, and characteristics of the household.

Cohort enrollment and a number of participants in the follow-up is shown in Figure 2. At the beginning of the study (first recruitment), 78.4% of the eligible infants were included in the cohort follow-up. There were no statistically significant differences in the mother's age, marital status, ethnicity or years of study between groups of infants included and not included in the cohort follow-up.

Flowchart of participants of the arbovirosis birth cohort study in Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012-2017.

Almost 17% of infants recruited were lost to follow-up in the first year of life and 17% in the second year. Most of them could not be located (unsuccessful contact or address not found) (n = 57; 47%) or had moved (n = 35; 29%) in two years.

From the second recruitment, 332 new children were included in the study. To date, 719 children were enrolled in the study with at least one blood sample collected: 451 children are on follow-up, 75 5-years-old children concluded the study, and the others were lost during the period (Figure 2). One child died because of non-infectious disease.

Cohort participants reside in different areas covered by primary health care facilities in Manguinhos (Figure 3).

Geographic distribution of participants of the arbovirosis birth cohort study in Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Most of the mothers enrolled in the study were young, married or living with a partner and with a median level of schooling (Table 1).

There was a similar proportion of male (48%) and female followed-up in 2,759 pediatric consultations during the study period. Among 2,181 scheduled consultations in the follow-up routine, 81.8% of children were asymptomatic. In total, there were 976 symptomatic consultations between scheduled and febrile/rash surveillance visits.

Phone calls, WhatsApp or Facebook messages were effective methods for active febrile/rash surveillance in 36.7% of cases, while household visits were successful in 48.7% of cases. Passive contacts were not registered.

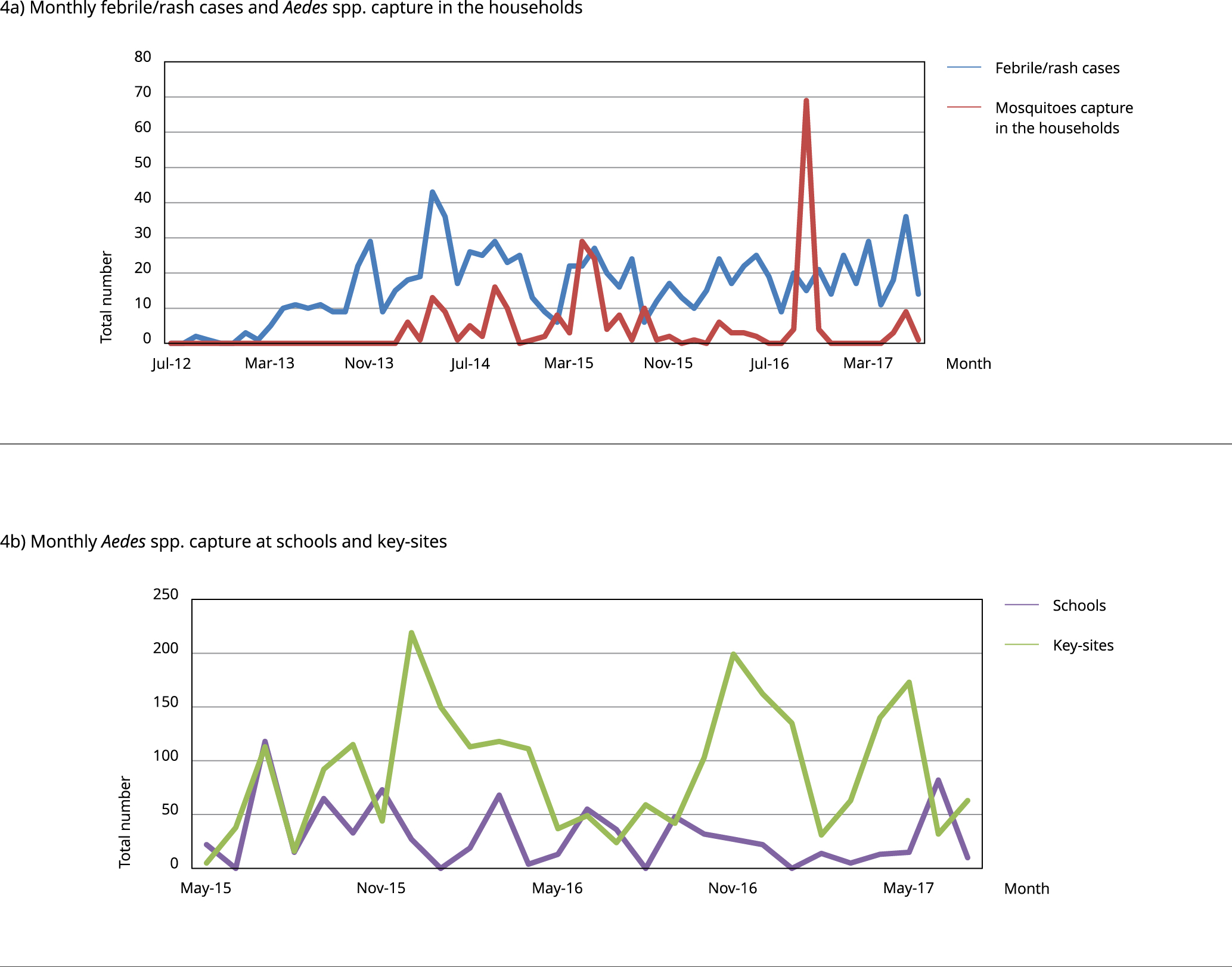

At the beginning of the study, 34.4% of infants have not even had one febrile or rash consultation. After implementation of the media apps for active surveillance, this proportion decreased to 29.6%, and the total number of febrile or rash consultations increased 3.5-fold. During the study period, no temporal pattern, seasonality or peak of febrile cases were observed in the graphics, depicting the small number and high fluctuation of cases (Figure 4a).

Total number of febrile/rash cases and Aedes spp. collected per month during the study period.

During the entomological surveillance, 277 households, 23 key-sites, and nine schools were visited for the collection of adult mosquitoes and eggs (Figures 4a and 4b). A total of 10,105 adult mosquitoes were collected, including 3,457 Ae. aegypti, 46 Ae. albopictus, 16 Ae. scapularis, 4 Ae. fluviatilis and 6,582 Culex quinquefasciatus. Moreover, 46,047 eggs were collected from the schools. The mean eggs/week collected per school varied between 13.2 and 233. From the total eggs collected, 12 Ae. albopictus and 183 Ae. aegypti larvae were identified (eclosion rate: 0.42%).

Several characteristics of the households presented potential breeding sites, as described in Table 2.

Discussion

This study is the first birth populational-based cohort in a low-income neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro, an important hub for all arbovirosis endemic in South America. We describe the methodological aspects and the complexity of implementing a comprehensive cohort study in such areas of a large urban settlement in a middle-income country, enlightening the main obstacles and facilitators.

Participants’ households were homogeneously distributed in the Manguinhos territory. The primary health care facilities was very important to improve adherence, and especially helpful in the recruitment process of pregnant women and children. The similarity of social and demographic characteristics in both phases of recruitment indicates that the criterion for eligibility was homogeneous and had not changed over time.

The pediatric care offered to the children included in the study was central to the adherence; a large number of consultations indicated the importance of this cohort. Most children had at least one scheduled pediatric visit in the first two years of life, and the annual loss of follow-up was almost the same in each year

Concerns about newborns blood collection were the most relevant reason for the refusal of pregnant women to participate in the study, as shown in previous studies 99. Pengsaa K, Luxemburger C, Sabchareon A, Limkittikul K, Yoksan S, Chambonneau L, et al. Dengue virus infections in the first 2 years of life and the kinetics of transplacentally transferred dengue neutralizing antibodies in thai children. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:1570-6.,1010. Chau TNB, Hieu NT, Anders KL, Wolbers M, Le Bich L, Lu Thi Minh H, et al. Dengue virus infections and maternal antibody decay in a prospective birth cohort study of Vietnamese infants. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:1893-900.,1111. Libraty DH, Acosta LP, Tallo V, Segubre-Mercado E, Bautista A, Potts JA, et al. A prospective nested case-control study of dengue in infants: rethinking and refining the antibody-dependent enhancement dengue hemorrhagic fever model. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000171.,1212. Anders KL, Nguyen NM, Van Thuy NT, Hieu NT, Nguyen HL, Hong Tham NT, et al. A birth cohort study of viral infections in Vietnamese infants and children: study design, methods and characteristics of the cohort. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:937.,1414. Kuan G, Gordon A, Avilés W, Ortega O, Hammond SN, Elizondo D, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: study design, methods, use of information technology, and extension to other infectious diseases. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 170:120-9.. In addition, the frequency of dropouts in this populational-based birth cohort was directly related to the social and housing conditions of the study’s territory.

Phone calls to invite children to scheduled visits were often unsuccessful due to the frequent phone number and address changes, both inside and outside the territory of Manguinhos. In 2008, the federal government implemented a housing, transportation and sanitation program (Growth Acceleration Program - PAC) in the area, resulting in a series of urban movements, partially explaining the loss of follow-up 2727. Rabello RS. Estratégia Saúde da Família: sistema de informações e fatores associados ao cadas-tramento em inquérito de saúde em uma comunidade do Rio de Janeiro [Tese de Doutorado]. Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2016.. Moreover, urban violence related to traffic dealers and police gun conflagrations limited the movement of families and restricted the presence of the research team in the area 2828. Barcellos C, Zaluar A. Homicídios e disputas territoriais nas favelas do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Saúde Pública 2014; 48:94-102.. In fact, the proportion of losses was similar in other cohort studies in the same region (30.7%-35%) 2929. Gama SR, Carvalho MS, Cardoso LO, Chaves CRMM, Engstrom EM. Cohort study for monitoring cardiovascular risk factors in children using a primary health care service: methods and initial results. Cad Saúde Pública 2011; 27:510-20.. However, losses were smaller (14.7%) in a hospital-based infant dengue cohort study carried out in Recife, Pernambuco State 1515. Braga C, Albuquerque MFPM, Cordeiro MT, Castanha PMS, Ramesh A, Alexander N, et al. Prospective birth cohort in a hyperendemic dengue area in Northeast Brazil: methods and preliminary results. Cad Saúde Pública 2016; 32:e00095815..

The implementation of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP-Manguinhos), a policy of local development, social inclusion and action against violence in the area, benefited the neighborhood and, consequently, the study between 2013 and 2015, when it was interrupted. The lack of regular investments in the study area impaired the maintenance of improvements in public health interventions and, hence, the ongoing projects.

During the study, we adopted some strategies to improve attendance at scheduled visits. The availability of a car ride to bring participants from their residences to the health unit for the pediatric consultations was a successful approach. The use of social networks, such as Facebook and WhatsApp in 2014, improved the communication between the family and the project team. Furthermore, we used visits by our local staff to remind participants of the scheduled visit when other strategies were not successful.

Most cohort studies have used mainly passive surveillance of suspected cases for disease monitoring 1111. Libraty DH, Acosta LP, Tallo V, Segubre-Mercado E, Bautista A, Potts JA, et al. A prospective nested case-control study of dengue in infants: rethinking and refining the antibody-dependent enhancement dengue hemorrhagic fever model. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000171.,1212. Anders KL, Nguyen NM, Van Thuy NT, Hieu NT, Nguyen HL, Hong Tham NT, et al. A birth cohort study of viral infections in Vietnamese infants and children: study design, methods and characteristics of the cohort. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:937.,1313. Gordon A, Kuan G, Mercado JC, Gresh L, Avilés W, Balmaseda A, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: incidence of inapparent and symptomatic dengue virus infections, 2004-2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7:e2462.,1414. Kuan G, Gordon A, Avilés W, Ortega O, Hammond SN, Elizondo D, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: study design, methods, use of information technology, and extension to other infectious diseases. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 170:120-9.. In this study, although young, mothers were concerned about their children, which helped increasing adherence to the project and contributed to the surveillance of febrile children. The most effective strategy to enhance the frequency of children consultation was the household visit performed by the local field assistants.

Integration of entomological surveillance with the epidemiological populational-based cohort study was successful, resulting in relevant data. Household conditions favored the presence of Ae. aegypti. The presence of water reservoirs inside the households results in potential breeding sites and contributes to stable mosquito infestation over time 3030. Gibson G, Souza-Santos R, Honório NA, Pacheco AG, Moraes MO, Kubelka C, et al. Conditions of the household and peridomicile and severe dengue: a case-control study in Brazil. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2014; 4:10.3402/iee.v4.22110.,3131. Maciel-de-Freitas R, Marques WA, Peres RC, Cunha SP, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Variation in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) container productivity in a slum and a suburban district of Rio de Janeiro during dry and wet seasons. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2007; 102:489-96.. As expected, mosquitoes collection in key-sites and daycare facilities were more effective than in the households 3030. Gibson G, Souza-Santos R, Honório NA, Pacheco AG, Moraes MO, Kubelka C, et al. Conditions of the household and peridomicile and severe dengue: a case-control study in Brazil. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2014; 4:10.3402/iee.v4.22110.. In almost all households in which a febrile case dwelt, the Aedes spp. was collected. Ae. albopictus, a competent vector for important arboviruses and more commonly found in areas with higher vegetation coverage, was present in this low-income urbanized area 3232. Ayllón T, Câmara DCP, Morone FC, Gonçalves LS, Saito Monteiro de Barros F, Brasil P, et al. Dispersion and oviposition of Aedes albopictus in a Brazilian slum: initial evidence of Asian tiger mosquito domiciliation in urban environments. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0195014.. Moreover, Zika virus was detected in April 2015 in engorged Ae. aegypti mosquitoes collected in this area 2626. Ayllón T, Campos RM, Brasil P, Morone FC, Câmara DCP, Meira GLS, et al. Early evidence for Zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1411-2..

During the dengue and Zika epidemics in 2013/2014 and 2015/2016, respectively, there was no increase in the referred incidence of fever or rash episodes among children. Whether previous dengue infection or maternal antibodies protected them against Zika or they had asymptomatic infections is unknown. Further serological studies are needed to answer this question.

Reopening the cohort was sufficient to replace the dropouts and contributed to the incorporation in the study of another arbovirosis such as Zika and chikungunya virus infection, since 2015 44. Brasil P, Pereira JP, Moreira ME, Nogueira RMR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2321-34.,2626. Ayllón T, Campos RM, Brasil P, Morone FC, Câmara DCP, Meira GLS, et al. Early evidence for Zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1411-2.,3232. Ayllón T, Câmara DCP, Morone FC, Gonçalves LS, Saito Monteiro de Barros F, Brasil P, et al. Dispersion and oviposition of Aedes albopictus in a Brazilian slum: initial evidence of Asian tiger mosquito domiciliation in urban environments. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0195014.. The opportunity for detecting emerging infectious diseases increases in an open cohort with time extension and constant enrollment of new participants and changing of clinical criteria inclusion, all within a flexible methodology, in contrast to regular clinical research protocols.

Our capacity to mount a rapid research response during emergency periods such as the detection and follow up of ZIKV positive pregnant women at the very beginning of the Zika epidemic was due to the existence of this ongoing cohort study 44. Brasil P, Pereira JP, Moreira ME, Nogueira RMR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2321-34.. Furthermore, although challenging, adding an entomological component to the study enabled detection of ZIKV in mosquitoes before the first case of autochthonous ZIKV virus disease was diagnosed in Rio de Janeiro 2626. Ayllón T, Campos RM, Brasil P, Morone FC, Câmara DCP, Meira GLS, et al. Early evidence for Zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1411-2..

Although the contests and facilitators discussed here are not statistically representative of the population as a whole, our results highlights the need of studies in endemicity places and, maybe, even contribute to the implementation of similar studies in these areas.

The ability to perform such a population-based cohort study relied on the willingness and enthusiasm of a multidisciplinary team, capable of keeping continuous surveillance over the years. Together, our indirect results 44. Brasil P, Pereira JP, Moreira ME, Nogueira RMR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2321-34.,2626. Ayllón T, Campos RM, Brasil P, Morone FC, Câmara DCP, Meira GLS, et al. Early evidence for Zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1411-2.,3232. Ayllón T, Câmara DCP, Morone FC, Gonçalves LS, Saito Monteiro de Barros F, Brasil P, et al. Dispersion and oviposition of Aedes albopictus in a Brazilian slum: initial evidence of Asian tiger mosquito domiciliation in urban environments. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0195014. underscore potential contributions of this structured sentinel populational-based birth cohort, both towards the knowledge of risks and awareness of emerging pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who participated in the study and the directors of the health center at Sergio Arouca National School of Public Health, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, and Victor Valla Family Clinic for the provided facilities. We are also grateful to our field team for the commitment throughout the study and Mônica A. F. M. Magalhães for the georeferencing support. R. S. Pedro is supported by a doctoral fellowship from Graduate Studies Coordinating Board (Capes) and T. Ayllón by a post-doctoral fellowship Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq). The study received financial support from the CNPq and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

References

-

1Donalisio MR, Freitas ARR, Zuben APBV. Arboviruses emerging in Brazil: challenges for clinic and implications for public health. Rev Saúde Pública 2017; 51:30.

-

2World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/ (accessed on 10/Nov/2017).

» http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/ -

3Nunes MRT, Faria NR, de Vasconcelos JM, Golding N, Kraemer MU, de Oliveira LF, et al. Emergence and potential for spread of chikungunya virus in Brazil. BMC Med 2015; 13:102.

-

4Brasil P, Pereira JP, Moreira ME, Nogueira RMR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2321-34.

-

5Campos GS, Bandeira AC, Sardi SI. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1885-6.

-

6Lowe R, Barcellos C, Brasil P, Cruz OG, Honório NA, Kuper H, et al. The Zika virus epidemic in Brazil: from discovery to future implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15. pii:E96.

-

7França GVA, Pedi VD, Garcia MHO, Carmo GMI, Leal MB, Garcia LP. Síndrome congênita associada à infecção pelo vírus Zika em nascidos vivos no Brasil: descrição da distribuição dos casos notificados e confirmados em 2015-2016. Epidemiol Serv Saúde 2018; 27:e2017473.

-

8Alves LV, Paredes CE, Silva GC, Mello JG, Alves JG. Neurodevelopment of 24 children born in Brazil with congenital Zika syndrome in 2015: a case series study. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e021304.

-

9Pengsaa K, Luxemburger C, Sabchareon A, Limkittikul K, Yoksan S, Chambonneau L, et al. Dengue virus infections in the first 2 years of life and the kinetics of transplacentally transferred dengue neutralizing antibodies in thai children. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:1570-6.

-

10Chau TNB, Hieu NT, Anders KL, Wolbers M, Le Bich L, Lu Thi Minh H, et al. Dengue virus infections and maternal antibody decay in a prospective birth cohort study of Vietnamese infants. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:1893-900.

-

11Libraty DH, Acosta LP, Tallo V, Segubre-Mercado E, Bautista A, Potts JA, et al. A prospective nested case-control study of dengue in infants: rethinking and refining the antibody-dependent enhancement dengue hemorrhagic fever model. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000171.

-

12Anders KL, Nguyen NM, Van Thuy NT, Hieu NT, Nguyen HL, Hong Tham NT, et al. A birth cohort study of viral infections in Vietnamese infants and children: study design, methods and characteristics of the cohort. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:937.

-

13Gordon A, Kuan G, Mercado JC, Gresh L, Avilés W, Balmaseda A, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: incidence of inapparent and symptomatic dengue virus infections, 2004-2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7:e2462.

-

14Kuan G, Gordon A, Avilés W, Ortega O, Hammond SN, Elizondo D, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric dengue cohort study: study design, methods, use of information technology, and extension to other infectious diseases. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 170:120-9.

-

15Braga C, Albuquerque MFPM, Cordeiro MT, Castanha PMS, Ramesh A, Alexander N, et al. Prospective birth cohort in a hyperendemic dengue area in Northeast Brazil: methods and preliminary results. Cad Saúde Pública 2016; 32:e00095815.

-

16Haug CJ, Kieny MP, Murgue B. The Zika challenge. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1801-3.

-

17Maciel-de-Freitas R, Aguiar R, Bruno RV, Guimarães MC, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Sorgine MH, et al. Why do we need alternative tools to control mosquito-borne diseases in Latin America? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2012; 107:828-9.

-

18Honório NA, Nogueira RMR, Codeço CT, Carvalho MS, Cruz OG, Magalhães MAFM, et al. Spatial evaluation and modeling of dengue seroprevalence and vector density in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009; 3:e545.

-

19dos Reis IC, Honório NA, Codeço CT, Magalhães MAFM, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Barcellos C. Relevance of differentiating between residential and non-residential premises for surveillance and control of Aedes aegypti in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Acta Trop 2010; 114:37-43.

-

20Índice de Desenvolvimento Humano Municipal (IDH), por ordem de IDH, segundo os bairros ou grupo de bairros - 2000. http://portalgeo.rio.rj.gov.br/amdados800.asp?gtema=15 (accessed on 10/Nov/2017).

» http://portalgeo.rio.rj.gov.br/amdados800.asp?gtema=15 -

21Engstrom E, Fonseca Z, Leimann B. A experiência do território escola Manguinhos na atenção primária de saúde. http://andromeda.ensp.fiocruz.br/teias/sites/default/files/arquivo_nossa_producao/A%20Experiencia%20do%20Territorio%20Escola%20Manguinhos%20na%20Atencao%20Primaria%20de%20Saude.pdf (accessed on 13/Oct/20217).

» http://andromeda.ensp.fiocruz.br/teias/sites/default/files/arquivo_nossa_producao/A%20Experiencia%20do%20Territorio%20Escola%20Manguinhos%20na%20Atencao%20Primaria%20de%20Saude.pdf -

22Lwanga S, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies - a practical manual. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/40062/1/9241544058_(p1-p22).pdf (accessed on 20/Oct/2016).

» http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/40062/1/9241544058_(p1-p22).pdf -

23Nasci R. A lightweight battery-powered aspirator for collecting resting mosquitões in the field. Mosq News 1981; 41:808-11.

-

24Honório NA, Silva WC, Leite PJ, Gonçalves JM, Lounibos LP, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Dispersal of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in an urban endemic dengue area in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003; 98:191-8.

-

25Consoli R, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Principais mosquitos de importância sanitária no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz; 1994.

-

26Ayllón T, Campos RM, Brasil P, Morone FC, Câmara DCP, Meira GLS, et al. Early evidence for Zika virus circulation among Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1411-2.

-

27Rabello RS. Estratégia Saúde da Família: sistema de informações e fatores associados ao cadas-tramento em inquérito de saúde em uma comunidade do Rio de Janeiro [Tese de Doutorado]. Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2016.

-

28Barcellos C, Zaluar A. Homicídios e disputas territoriais nas favelas do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Saúde Pública 2014; 48:94-102.

-

29Gama SR, Carvalho MS, Cardoso LO, Chaves CRMM, Engstrom EM. Cohort study for monitoring cardiovascular risk factors in children using a primary health care service: methods and initial results. Cad Saúde Pública 2011; 27:510-20.

-

30Gibson G, Souza-Santos R, Honório NA, Pacheco AG, Moraes MO, Kubelka C, et al. Conditions of the household and peridomicile and severe dengue: a case-control study in Brazil. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2014; 4:10.3402/iee.v4.22110.

-

31Maciel-de-Freitas R, Marques WA, Peres RC, Cunha SP, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Variation in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) container productivity in a slum and a suburban district of Rio de Janeiro during dry and wet seasons. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2007; 102:489-96.

-

32Ayllón T, Câmara DCP, Morone FC, Gonçalves LS, Saito Monteiro de Barros F, Brasil P, et al. Dispersion and oviposition of Aedes albopictus in a Brazilian slum: initial evidence of Asian tiger mosquito domiciliation in urban environments. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0195014.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

23 May 2019 -

Date of issue

2019

History

-

Received

20 Feb 2018 -

Reviewed

31 Oct 2018 -

Accepted

23 Nov 2018

Note: the distribution of participants in the areas covered by primary health-care facilities is shown. Fiocruz: Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

Note: the distribution of participants in the areas covered by primary health-care facilities is shown. Fiocruz: Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

Note: the number of febrile/rash cases (blue line) and mosquitoes (red line) numbers collected where febrile/rash cases were reported is shown (a). The number of adult traps and ovitraps at schools (purple line) and key-sites (green line) is shown (b). Aedes spp. included the species Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, Ae. scapularis, and Ae. fluviatilis.

Note: the number of febrile/rash cases (blue line) and mosquitoes (red line) numbers collected where febrile/rash cases were reported is shown (a). The number of adult traps and ovitraps at schools (purple line) and key-sites (green line) is shown (b). Aedes spp. included the species Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, Ae. scapularis, and Ae. fluviatilis.