Abstract

Purpose:

To investigated the inflammatory, angiogenic and fibrogenic activities of the Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi leaves oil (STRO) on wound healing.

Methods:

The excisional wound healing model was used to evaluate the effects of STRO. The mice were divided into two groups: Control, subjected to vehicle solution (ointment lanolin/vaseline base), or STRO- treated group, administered topically once a day for 3, 7 and 14 days post-excision. We evaluated the macroscopic wound closure rate; the inflammation was evaluated by leukocytes accumulation and cytokine levels in the wounds. The accumulation of neutrophil and macrophages in the wounds were determined by assaying myeloperoxidase and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase activities. The levels of TNF-α, CXCL-1 and CCL-2 in wound were evaluated by ELISA assay. Angiogenesis and collagen fibers deposition were evaluated histologically.

Results:

We observed that macroscopic wound closure rate was improved in wounds from STRO-group than Control-group. The wounds treated with STRO promoted a reduction in leucocyte accumulation and in pro-inflammatory cytokine. Moreover, STRO treatment increased significantly the number of blood vessels and collagen fibers deposition, as compared to control group.

Conclusion:

Topical application of STRO display anti-inflammatory and angiogenic effects, as well as improvement in collagen replacement, suggesting a putative use of this herb for the development of phytomedicines to treat inflammatory diseases, including wound healing.

Key words:

Wound Healing; Angiogenesis Modulating Agents; Anti-Inflammatory Agents; Phytotherapy; Skin; Mice

Introduction

The Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi) is native to the Northeast, Central-West, Southeast and South regions of Brazil known as aroeira. It has been used in folk medicine as teas, infusions or tinctures as an anti-inflammatory, febrifuge, analgesic, and depurative agent; also, it has been used to treat skin wounds, repair injury in respiratory, digestive and genitourinary systems11 Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201300...

2 Estevão LRM, Medeiros JP, Simões, RS, Arantes RM, Rachid MA, Silva RM, Mendonça FS, Evêncio-Neto J. Mast cell concentration and skin wound contraction in rats treated with Brazilian pepper essential oil (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi). Acta Cir Bras. 2105;30(4):289-95. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020150040000008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201500...

3 Santos OJ, Ribas Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Castelo Branco Neto ML, Naufel Jr C, Ferreira LM, Campos RP, Moreira H, Porcides RD, Dobrowolski S. Avaliação do extrato de Aroeira (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi) no processo de cicatrização de gastrorrafias em ratos. Acta Cir Bras. 2006:21:39-45. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502006000800007.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650200600...

4 Santos OJ, Malafaia O, Ribas-Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Santos RHP, Santos RAP,. Efeito de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (aroeira) e Carapa guianensis Aublet (andiroba) na cicatrização de gastrorrafias. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig (São Paulo). 2013;26:84-91. doi: 10.1590/S0102-67202013000200003.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-6720201300...

5 Rosas EC, Correa LB, Pádua TA, Costa TE, Mazzei JL, Heringer AP, Bizarro CA, Kaplan MA, Figueiredo MR, Henriques MG. Anti-inflammatory effect of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi hydroalcoholic extract on neutrophil migration in zymosan-induced arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:490-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.014.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.01...

-66 Scheib CL, Ribas-Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Malafaia O, Barboza LE, Ribas FM, Wendler E, Torres O, Lovato FC, Scapini JG. Schinus terebinthifolius raddi (Aroeira) and Orbignya phalerata mart. (Babassu) effect in cecorrahphy healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2016;31(6):402-10. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020160060000007.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201600...

. Previous reports have demonstrated that S. terebinthifolius extracts or fractions is rich in polyphenols, which display antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal and anti-allergic activities in different experimental models77 de Lima MR, de Souza Luna J, dos Santos AF, de Andrade MC, Sant'Ana AE, Genet JP, Marquez B, Neuville L, Moreau N. Anti-bacterial activity of some Brazilian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105(1-2):137-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.026.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.02...

-88 Cavalher-Machado SC, Rosas EC, Brito FA, Heringe AP, de Oliveira RR, Kaplan MA, Figueiredo MR, Henriques MD. The anti-allergic activity of the acetate fraction of Schinus terebinthifolius leaves in IgE induced mice paw edema and pleurisy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;(11):1552-60. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.06.012.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2008.06...

.

Skin wound healing is a dynamic process that involves cellular, molecular and humoral components to tissue restore after injury99 Greaves NS, Ashcroft KJ, Baguneid M, Bayat A. Current understanding of molecular and cellular mechanisms in fibroplasia and angiogenesis during acute wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;72:206-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.07.008.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013....

. In adult mammals, it involves an early inflammatory stage characterized by the infiltration of neutrophil and macrophages, with the subsequent formation of granulation tissue. In addition, keratinocytes from the borders of the legion proliferate and migrate to restore the epidermis of the injured skin1010 Reinke JM, Sorg H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49(1):35-43. doi: 10.1159/000339613.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000339613...

.

However, an impaired inflammatory response in the early stage of skin wound healing may compromise the quality of repair1111 Qian LW, Fourcaudot AB, Yamane K, You T, Chan RK, Leung KP. Exacerbated and prolonged inflammation impairs wound healing and increases scarring. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(1):26-34. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12381.

https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12381...

. Thus, the development of therapies based on the attenuation of inflammation response during wound healing will lead to the development of efficient therapeutic approaches to improve the quality of repair1212 Koh TJ, DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001943.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S146239941100194...

-1313 Rennert RC, Rodrigues M, Wong VW, Duscher D, Hu M, Maan Z, Sorkin M, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Biological therapies for the treatment of cutaneous wounds: phase III and launched therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:1523-41. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.842972.

https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2013.84...

.

Many new therapies that target various aspects of wound repair are emerging in recent years using natural components derived from plants1414 Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014;116:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.016.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.01...

-1515 Morgan C, Nigam Y. Naturally derived factors and their role in the promotion of angiogenesis for the healing of chronic wounds. Angiogenesis 2013;16:493-502. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9341-1.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-013-9341-...

. However, the healing effects from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi are not completely understood.

Therefore, we hypothesized that the leaves oil of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (STR) would improve wound healing by modulating inflammation, angiogenesis and collagen deposition in wound site. A better understanding of the effects of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi in wound healing may provide futures insights to develop new strategies therapeutic approaches for the management fibroproliferative disorders.

Methods

Collection, identification, processing, and extraction of plant material

Leaves of the pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi, Anacardiaceae) were collected in the morning of September 2010 on the campus of Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE). The plant was identified by comparison with a previously identified specimen and deposited in the Herbarium Vasconcelos Sobrinho UFRPE under the number 49259.

To obtain the essential oil, fresh leaves (200g) were crushed and subjected to hydrodistillation technique in a modified Clevenger apparatus. After two hours of hydrodistillation the oil obtained was separated from water by density difference and excess moisture was removed with anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4). The total oil amount was calculated based on the weight of fresh leaves. The oil was stored in amber glass container, tightly closed kept in freezer, until the experiment, at a temperature of -20°C. The study of the leaves oil had its chemical profile reported by Silva et al.1616 Silva AB, Silva T, Franco ES, Rabelo SA, Lima ER, Mota RA, Câmara CA, Pontes-Filho NT, Lima-Filho JV. Antibacterial activity, chemical composition, and cytotoxicity of leaf's essential oil from brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius, Raddi). Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41:158-63. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220100001000023.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-8382201000...

, which identified thirty-three components, representing 95.5% of the oil. Among the majority of this oil compounds are p-Cymen-7-ol (22.5%), 9-epi-(E)-cariophyllene (10.1%), carvone (7.5%) and Verbenone (7.4%).

With the oil, an ointment was manipulated with a lanolin-vaselina formulation: lanolin anhydrous - 30%; essential oil of aroeira leaf - 10% and solid vaseline qsp 100g, (anhydrous lanolin purchased from Pharma Special, solid vaseline and BHT acquired from DEG)1616 Silva AB, Silva T, Franco ES, Rabelo SA, Lima ER, Mota RA, Câmara CA, Pontes-Filho NT, Lima-Filho JV. Antibacterial activity, chemical composition, and cytotoxicity of leaf's essential oil from brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius, Raddi). Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41:158-63. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220100001000023.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-8382201000...

.

Experimental animal

The project proposal was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal Rural University de Pernambuco (license no 123/2016).

Male C57BL/6 mice 7-8 weeks (25-30 g body weight) (n=30), were provided by the Centro de Bioterismo (CEBIO) of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG)-Brazil. The animals were housed individually and provided with chow pellets and water ad libitum. The light/dark cycle was 12:12 h with lights on at 7:00 am and lights off at 7:00 pm. The experiment was conducted in the animal colony at the Animal Morphology Department, UFRPE. The animals were acclimatized for 2 weeks in a well-ventilated room, and standard pellet feed and tap water were provided ad libitum throughout the experimentation period. At the end of the experiment the animals were euthanized, prepared and discarded complied with the guidelines established by our local Institutional Animal Welfare Committee.

Wounding, experimental groups and measurement of wound area

The mice were divided into two groups (control and treated) of fifteen animals each, and all animals were anesthetized with a combination of 2% xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/Kg) and 10% ketamine hydrochloride (60 mg/Kg), administered, intraperitoneally, prior to infliction of skin wounds. The animal’s furry thoracic region was shaved with an electrical clipper and antisepsis was performed with 0.5% topical alcoholic chlorhexidine. Four excisional wounds were made on the dorsum of mice with the aid of a sterile 5-mm circular punch, removing the entire thickness of the skin. Wound excision was made carefully to avoid muscle incision. Immediately after surgical excision the control group (n=15), received a daily topical application of the ointment lanolin and vaseline base (Vehicle group) - and treated group (n=15), received a daily topical application of the ointment containing 10% aroeira Leaf oil (STRO group). The mice were then divided into three groups of five animals each according to the time of application of the ointment, as described: G3 - three days application; G7 - seven days of application and G14 - 14 days of application. After surgery, mice were kept in individual cages.

The area of wounds was measured with a digital caliper, on days 0, 3, 7 e 14 after surgery and the results were expressed as percentage closure, relative to original size (wound contraction = original wound area - present wound area / total wound area x 100)11 Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201300...

. No signs of infection were detected in the wounds area.

Quantification of neutrophil and macrophage tissue accumulation

The extent of neutrophil accumulation in the wound tissue as measured by assaying myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, as described previously1717 Cassini-Vieira P, Araújo FA, da Costa Dias FL, Russo RC, Andrade SP, Teixeira MM, Barcelos LS. iNOS Activity modulates inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue fibrosis in polyether-polyurethane synthetic implants. Mediators Inflamm. 2015:215:138461. doi: 10.1155/2015/138461.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/138461...

. On days 3, 7 and 14 P.O, after euthanasia with an overdose of anesthetic (Pentobarbital sodium 100mg/kg, intraperitoneally), the wound and surrounding skin area were removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen. On thawing and processing, the tissue (100 mg tissue/1 ml buffer) was homogenized in 0.02 mol/l NaPO4 buffer (pH 4.7) containing 0.015 mol/l Na-EDTA, centrifuged at 10.000 g for 10 min, and the pellet was submitted to hypotonic lyses. After a further centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 0.05 mol/l NaPO4 buffer (pH 5.4) containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide and rehomogenized. Suspensions were then submitted to three freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen and centrifuged for 15 min at 10.000 3g; supernatants were used for MPO assay. The assay was performed by measuring the change in OD at 450 nm using 1.6 mM 3,39-5,59-tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in DMSO (Merck, Rahway, NJ) and 0.003% H2O2 (v/v) in phosphate buffer (0.05 M Na3PO4 and 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide [pH 5.4]). Results were expressed as the relative unit that denotes activity of MPO. The extent of macrophages accumulation in the wound tissue was measured by assaying N-acetyl-b-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) activity, as described previously. Briefly, the tissue (100 mg tissue/1 ml buffer) was homogenized in 0.9% saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (v/v) and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 3000 3g; supernatants were used for NAG assay. The assay was performed by measuring the change in OD at 405 nm using p-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (Sigma- Aldrich) and 0.2 M glycine buffer (pH 10.6). Results were expressed as the relative unit that denotes activity of NAG.

Measurement of cytokine/chemokine concentrations in the wounds

On thawing and processing, the tissue was homogenized in extraction solution (100mg tissue/1ml), containing 0.4MNaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.5% BSA, 0.1mM PMSF, 0.1 mM benzethoniumchloride, 10 mM EDTA, and 20 KI aprotinin, using Ultra-Turrax. The suspension was then spin at 10.000 3g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants from wounds were used to examine the levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL-2) and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1) by ELISA assay, performed using kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) , according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were assayed in duplicate. The threshold of sensitivity for each cytokine/chemokine was 7.5 pg/ml.

Histological assessment

On days 3, 7 and 14 of the experiment, skin samples were collected and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Sections (5μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H.E) and picrosirius red and processed for light-microscopic studies. The images were digitized with Olympus BX43 microscope with an Olympus Q-Color 5 micro camera. Angiogenesis were determined by counting blood vessels in the entire area of wound tissue on H&E stained sections, cross sections images were obtained from 6 sequential fields from each wound and observed with an objective (x40) in light microscopy (final magnification = x400)11 Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201300...

.

For collagen analysis, images were obtained from 5 fields from each wound and observed with an objective x20 (final magnification = x200) under polarized light (Olympus). Morphometric and digital analysis were performed using ImageProPlus 7.0 Software. All histomorphometric analysis were performed as blind study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Results were presented as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were carried out using Student t test for unpaired data. Two-way ANOVA was used for graph lines to verify the interaction between the independent variables time and strain followed by Bonferroni post test (p < 0.05).

Results

Wound closure is improved in STRO-treated group

The STRO-treated group exhibited a significant increase in the percentage of wound closure after day 3 post-wounding, when compared with vehicle-treated group; approximately 37% in STRO-treated group versus 21% in vehicle-treated group (p<0.05) (Figure 1 A-B).

Wound closure is improved in STRO-treated group. (A) Time-course of wound closure in STRO-treated and vehicle groups. (B) Representative macroscopic pictures of wound from STRO-treated and vehicle-treated group. Results of wound closure rate were expressed as percentage closure relative to original size (1 − [wound area]/[original wound area] × 100). Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 5 mice for each time point and group. *p<0.05 versus Vehicle-treated group (Two-way ANOVA).

Leukocyte accumulation is reduced in STRO-treated group

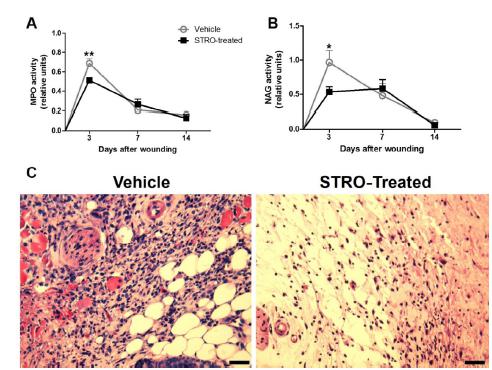

We observed a reduction in the leukocyte accumulation of wounds from STRO-treated group, when compared to Vehicle-treated group, as assayed by MPO (Figure 2A, p<0.05 at 3 day) and NAG activities (Figure 2B, p<0.05 at 3 day). Likewise, TNF-α (Figure 3A, p<0.001 at 7 day) CXCL-1 (Figure 3B, p<0.01 at 3 day and p<0.05 at 7 day) and CCL-2 (Figure 3C, p<0.01 at 7 day) were reduced in wounds from STRO-treated when compared with vehicle-treated group. The histology showed a reduced cellularization in wounds from STRO-treated than Vehicle-treated group.

Leukocyte accumulation is reduced in wounds from STRO-treated group. (A) MPO. (B) NAG. (C) Representative photomicrographs of H&E stained sections at 3 day post-wounding. Data represent the mean ± SEM; n=5 for each time point and group; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus Vehicle-treated group (Two-way ANOVA). Bar 50μm.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines is reduced in STRO-treated group. TNF-α (A), CXCL-1 (B) and CCL-2 (C) time-course production profile in wounds from STRO-treated and Vehicle-treated groups. Cytokines levels were measured by sandwich ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 5 for each time point and group. *p<0.05; and **p<0.01 versus Vehicle-treated group (Two-way ANOVA).

Wound angiogenesis is increased in STRO-treated group

At day 7 after wounding, the number of vessels in wounds from STRO-treated group increased significantly when compared with Vehicle-treated group (Figure 4 A-B, p<0.05).

Angiogenesis increased in STRO-treated group. (A) Kinetics of blood vessels counting. (B) Representative photomicrographs of H&E stained histological sections at 7 day after wounding. Black arrows indicate the blood vessels. Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 5 for each time point and group. *p<0.05; and **p<0.01 versus Vehicle-treated group (Two-way ANOVA). Bar 50μm.

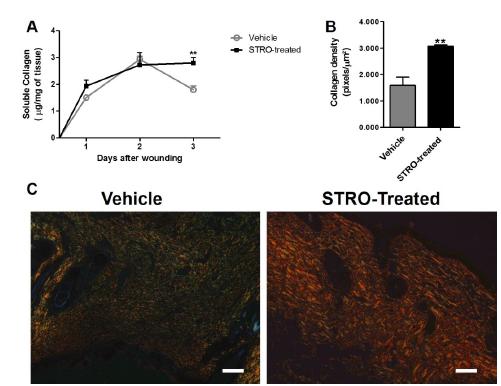

Collagen deposition is increased in STRO-treated group

Collagen deposition increased significantly in wounds from STRO-treated group when compared with Vehicle-treated group (Figure 5A, p<0.01 at 14 day and B, p<0.01).

Increased collagen deposition in wounds from STRO-treated group. (A) Kinetics of soluble collagen. (B) Collagen density. (C) Representative photomicrographs of picrosirius red stained sections at 14 day post-wounding visualized under polarized light microscopy. Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 5 for each time point and group. **p<0.01 versus Vehicle-treated group (Two-way ANOVA and Test-t student). Bar 50μm.

Discussion

Here, we investigated the effects of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi oil leaves (STRO) on wound closure, inflammation, angiogenesis and collagen deposition in skin wound healing after excision in mice. This experimental model has been used to study the biological mechanisms involved skin wound healing11 Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201300...

,22 Estevão LRM, Medeiros JP, Simões, RS, Arantes RM, Rachid MA, Silva RM, Mendonça FS, Evêncio-Neto J. Mast cell concentration and skin wound contraction in rats treated with Brazilian pepper essential oil (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi). Acta Cir Bras. 2105;30(4):289-95. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020150040000008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201500...

. STRO was applied topically as natural compounds with healing potential can be tested directly in wound bed1818 Park SA, Covert J, Teixeira L, Motta MJ, DeRemer SL, Abbott NL, Dubielzig R, Schurr M, Isseroff RR, McAnulty JF, Murphy CJ. Importance of defining experimental conditions in a mouse excisional wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(2):251-61. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12272.

https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12272...

.

It has been reported that topical application of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi extracts exerts angiogenic1 and pro-healing44 Santos OJ, Malafaia O, Ribas-Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Santos RHP, Santos RAP,. Efeito de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (aroeira) e Carapa guianensis Aublet (andiroba) na cicatrização de gastrorrafias. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig (São Paulo). 2013;26:84-91. doi: 10.1590/S0102-67202013000200003.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-6720201300...

effects in vivo. Accordingly, our study demonstrated that topical application of STRO improved wound closure and displayed angiogenic and fibrogenic effects. Interesting, we observed that STRO treatment also promoted anti-inflammatory responses in wounds mice.

The inflammatory response following tissue injury plays important roles both in normal and pathological healing processes1919 Demidova-Rice TN, Hamblin MR, Herman IM. Acute and impaired wound healing: pathophysiology and current methods for drug delivery, part 1: normal and chronic wounds: biology, causes, and approaches to care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25(7):304-14. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000416006.55218.d0.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.000041600...

. It provides protection against invading pathogens and remove damaged tissues2020 Landén NX, Li D, Stahle M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: a critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(20):3861-85. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2268-...

. However, prolonged inflammatory response lead to a delay in the progress through the physiological stages of wound healing1212 Koh TJ, DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001943.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S146239941100194...

.

Natural products with anti-inflammatory activity have long been used as a folk remedy for inflammatory conditions in wound, such as Curcuma longa2121 Sidhu GS, Singh AK, Thaloor D, Banaudha KK, Patnaik GK, Srimal RC, Maheshwari RK. Enhancement of wound healing by curcumin in animals. Wound Repair Regen. 1998;6:167-77. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1998.60211.x.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-475X.1998...

, Ranunculus pedatus2222 Akkol EK, Süntar I, Erdogan TF, Keles H, Gonenç TM, Kivçak B. Wound healing and anti-inflammatory properties of Ranunculus pedatus and Ranunculus constantinapolitanus: a comparative study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:478-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.037.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.03...

.

Here, we observed that STRO treatment was able to decrease the markers of inflammation in wounds. A significant reduction in TNF-α, CXCL-1 and CCL-2 levels as well as in neutrophil and macrophage accumulation, as measured by MPO and NAG activities, respectively, were found in the STRO treated group. Indeed, the reduction in these cytokines levels is usually associated with reduced inflammation2323 Barcelos LS, Talvani A, Teixeira AS, Vieira LQ, Cassali GD, Andrade SP, Teixeira MM. Impaired inflammatory angiogenesis, but not leukocyte influx in mice lacking TNFR1. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:352-58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104682.0741-5400/05/0078-352.

https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.1104682.0741...

,2424 Ashcroft GS, Jeong MJ, Ashworth JJ, Hardman M, Jin W, Moutsopoulos N, Wild T, McCartney-Francis N, Sim D, McGrady G, Song XY, Wahl SM. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) is a therapeutic target for impaired cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:38-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00748.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011...

. Our study is the first to demonstrate that STRO has anti-inflammatory effects on skin wound healing.

There is considerable evidence to suggest that angiogenesis and inflammation are codependent2525 Jackson JR, Seed MP, Kircher CH, Willoughby DA, Winkler JD. The codependence of angiogenesis and chronic inflammation. FASEB J. 1997;11:457-65. doi: 10.1096/fj.1530-6860.

https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.1530-6860...

. Angiogenesis is critical to wound repair. The process is important to provide nutrition and oxygen to growing tissues2626 Li J, Zhang YP, Kirsner RS. Angiogenesis in wound repair: Angiogenic growth factors and the extracellular matrix. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60:107-14. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10249.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.10249...

. A wide variety of plant-based compounds have been reported to act in angiogenesis process; these compounds include polyphenols, alkaloids, terpenoids and tannins2727 Lu K, Bhat M, Basu S. Plants and their active compounds: natural molecules to target angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2016;19:287-95. doi: 10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-016-9512-...

. We also observed an increased wound angiogenesis in STRO-treated mice when compared with Vehicle-treated group. In accordance, our group reported the angiogenic effects by Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi in wound repair11 Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201300...

,2828 Nunes JA Jr, Ribas-Filho JM, Malafaia O, Czeczko NG, Inácio CM, Negrão AW, Lucena PL, Moreira H, Wagenfuhr J Jr, Cruz Jde J. Evaluation of the hydro-alcoholic Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Aroeira) extract in the healing process of the alba linea in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2006;21(Suppl3):8-15. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502006000900003.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650200600...

. However, further studies are necessary to determine possible mechanisms.

In addition to its inflammatory and angiogenic activity, we observed that STRO was able to increase collagen deposition in the skin wound. Consistent with this finding, it has been reported that STRO induces collagen deposition in tissue repair in rats11 Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8650201300...

. The improved wound closure observed in STRO treated group may have been, at least in part, due to its fibrogenic effect.

Our present results have identified and confirmed the effects of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi, on some critical features of wound healing processes (angiogenesis, inflammation and collagen deposition). These results the range of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi actions and provides future insights in therapeutic of wound healing.

Conclusions

Topical application of STRO display anti-inflammatory and angiogenic effects, as well as improvement in collagen replacement, suggesting a putative use of this herb for the development of phytomedicines to treat inflammatory diseases, including wound healing.

References

-

1Estevão LRM, Mendonça FS, Baratella-Evêncio L, Simões RS, Barros MEG, Arantes RME, Rachid MA, Evêncio-Neto J. Effects of aroeira (Schinus terebinthifoliu Raddi) oil on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:202-9. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-86502013000300008 -

2Estevão LRM, Medeiros JP, Simões, RS, Arantes RM, Rachid MA, Silva RM, Mendonça FS, Evêncio-Neto J. Mast cell concentration and skin wound contraction in rats treated with Brazilian pepper essential oil (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi). Acta Cir Bras. 2105;30(4):289-95. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020150040000008.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-865020150040000008 -

3Santos OJ, Ribas Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Castelo Branco Neto ML, Naufel Jr C, Ferreira LM, Campos RP, Moreira H, Porcides RD, Dobrowolski S. Avaliação do extrato de Aroeira (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi) no processo de cicatrização de gastrorrafias em ratos. Acta Cir Bras. 2006:21:39-45. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502006000800007.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-86502006000800007 -

4Santos OJ, Malafaia O, Ribas-Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Santos RHP, Santos RAP,. Efeito de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (aroeira) e Carapa guianensis Aublet (andiroba) na cicatrização de gastrorrafias. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig (São Paulo). 2013;26:84-91. doi: 10.1590/S0102-67202013000200003.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-67202013000200003 -

5Rosas EC, Correa LB, Pádua TA, Costa TE, Mazzei JL, Heringer AP, Bizarro CA, Kaplan MA, Figueiredo MR, Henriques MG. Anti-inflammatory effect of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi hydroalcoholic extract on neutrophil migration in zymosan-induced arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:490-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.014.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.014 -

6Scheib CL, Ribas-Filho JM, Czeczko NG, Malafaia O, Barboza LE, Ribas FM, Wendler E, Torres O, Lovato FC, Scapini JG. Schinus terebinthifolius raddi (Aroeira) and Orbignya phalerata mart. (Babassu) effect in cecorrahphy healing in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2016;31(6):402-10. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020160060000007.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-865020160060000007 -

7de Lima MR, de Souza Luna J, dos Santos AF, de Andrade MC, Sant'Ana AE, Genet JP, Marquez B, Neuville L, Moreau N. Anti-bacterial activity of some Brazilian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105(1-2):137-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.026.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.026 -

8Cavalher-Machado SC, Rosas EC, Brito FA, Heringe AP, de Oliveira RR, Kaplan MA, Figueiredo MR, Henriques MD. The anti-allergic activity of the acetate fraction of Schinus terebinthifolius leaves in IgE induced mice paw edema and pleurisy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;(11):1552-60. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.06.012.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2008.06.012 -

9Greaves NS, Ashcroft KJ, Baguneid M, Bayat A. Current understanding of molecular and cellular mechanisms in fibroplasia and angiogenesis during acute wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;72:206-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.07.008.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.07.008 -

10Reinke JM, Sorg H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49(1):35-43. doi: 10.1159/000339613.

» https://doi.org/10.1159/000339613 -

11Qian LW, Fourcaudot AB, Yamane K, You T, Chan RK, Leung KP. Exacerbated and prolonged inflammation impairs wound healing and increases scarring. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(1):26-34. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12381.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12381 -

12Koh TJ, DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001943.

» https://doi.org/10.1017/S1462399411001943 -

13Rennert RC, Rodrigues M, Wong VW, Duscher D, Hu M, Maan Z, Sorkin M, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Biological therapies for the treatment of cutaneous wounds: phase III and launched therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:1523-41. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.842972.

» https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2013.842972 -

14Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014;116:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.016.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.016 -

15Morgan C, Nigam Y. Naturally derived factors and their role in the promotion of angiogenesis for the healing of chronic wounds. Angiogenesis 2013;16:493-502. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9341-1.

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-013-9341-1 -

16Silva AB, Silva T, Franco ES, Rabelo SA, Lima ER, Mota RA, Câmara CA, Pontes-Filho NT, Lima-Filho JV. Antibacterial activity, chemical composition, and cytotoxicity of leaf's essential oil from brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius, Raddi). Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41:158-63. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220100001000023.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-838220100001000023 -

17Cassini-Vieira P, Araújo FA, da Costa Dias FL, Russo RC, Andrade SP, Teixeira MM, Barcelos LS. iNOS Activity modulates inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue fibrosis in polyether-polyurethane synthetic implants. Mediators Inflamm. 2015:215:138461. doi: 10.1155/2015/138461.

» https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/138461 -

18Park SA, Covert J, Teixeira L, Motta MJ, DeRemer SL, Abbott NL, Dubielzig R, Schurr M, Isseroff RR, McAnulty JF, Murphy CJ. Importance of defining experimental conditions in a mouse excisional wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(2):251-61. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12272.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12272 -

19Demidova-Rice TN, Hamblin MR, Herman IM. Acute and impaired wound healing: pathophysiology and current methods for drug delivery, part 1: normal and chronic wounds: biology, causes, and approaches to care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25(7):304-14. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000416006.55218.d0.

» https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.0000416006.55218.d0 -

20Landén NX, Li D, Stahle M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: a critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(20):3861-85. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0.

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0 -

21Sidhu GS, Singh AK, Thaloor D, Banaudha KK, Patnaik GK, Srimal RC, Maheshwari RK. Enhancement of wound healing by curcumin in animals. Wound Repair Regen. 1998;6:167-77. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1998.60211.x.

» https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-475X.1998.60211.x -

22Akkol EK, Süntar I, Erdogan TF, Keles H, Gonenç TM, Kivçak B. Wound healing and anti-inflammatory properties of Ranunculus pedatus and Ranunculus constantinapolitanus: a comparative study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:478-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.037.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.037 -

23Barcelos LS, Talvani A, Teixeira AS, Vieira LQ, Cassali GD, Andrade SP, Teixeira MM. Impaired inflammatory angiogenesis, but not leukocyte influx in mice lacking TNFR1. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:352-58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104682.0741-5400/05/0078-352.

» https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.1104682.0741-5400/05/0078-352 -

24Ashcroft GS, Jeong MJ, Ashworth JJ, Hardman M, Jin W, Moutsopoulos N, Wild T, McCartney-Francis N, Sim D, McGrady G, Song XY, Wahl SM. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) is a therapeutic target for impaired cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:38-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00748.x.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00748.x -

25Jackson JR, Seed MP, Kircher CH, Willoughby DA, Winkler JD. The codependence of angiogenesis and chronic inflammation. FASEB J. 1997;11:457-65. doi: 10.1096/fj.1530-6860.

» https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.1530-6860 -

26Li J, Zhang YP, Kirsner RS. Angiogenesis in wound repair: Angiogenic growth factors and the extracellular matrix. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60:107-14. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10249.

» https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.10249 -

27Lu K, Bhat M, Basu S. Plants and their active compounds: natural molecules to target angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2016;19:287-95. doi: 10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y.

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y -

28Nunes JA Jr, Ribas-Filho JM, Malafaia O, Czeczko NG, Inácio CM, Negrão AW, Lucena PL, Moreira H, Wagenfuhr J Jr, Cruz Jde J. Evaluation of the hydro-alcoholic Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Aroeira) extract in the healing process of the alba linea in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2006;21(Suppl3):8-15. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502006000900003.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-86502006000900003

-

Financial sources:

FACEPE, and CNPq

-

1

Research performed at Department of Morphology and Animal Physiology, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE), Recife-PE, Brazil. Part of Post Doc, Postgraduate Program in Animal Bioscience. Tutor: Joaquim Evêncio-Neto.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Sept 2017

History

-

Received

25 May 2017 -

Reviewed

21 July 2017 -

Accepted

22 Aug 2017