Abstract:

The competitive agribusiness environment has been pressing organizational actors of dairy cooperatives to implement new structures. In this sense, many scholars advocate the existence of isomorphic practices that are not suitable for cooperative enterprises. This theoretical paper assumes that there are strategic actions related to the institutional demands, implemented by cooperative decision makers in relation to environmental pressures. Thus, we aimed to analyze how can be structured such strategic actions in relation to the institutional pressures of two organizational subfields related to cooperative business, in order to maintain the legitimacy of the business. For this, we drafted the projection of five analytical frameworks. As conclusions, it is inferred that a cooperative business restructuring not always tends to express an atomism of decision makers in relation to institutional demands of the organizational field, given that the demands are ambivalent and need to be met in order to obtain minimum level of legitimacy necessary for the organization survival.

Key-words:

cooperativism; institutional ambivalence; strategy action

Resumo:

O ambiente competitivo do agronegócio tem pressionado os atores organizacionais das cooperativas lácteas para implementar novas estruturações. Nesse sentido, diversos pesquisadores têm percebido a existência de práticas isomórficas que não são adequadas para empreendimentos cooperativos. Este artigo teórico assume que existem ações estratégicas relacionadas as demandas institucionais implementadas pelos tomadores de decisão em relação às pressões ambientais. Assim, almejou-se analisar como podem ser estruturadas tais ações estratégicas em relação às pressões institucionais de dois subcampos organizacionais relacionados ao cooperativo de forma a manutenção da legitimidade do negócio. Foram traçadas a projeção de cinco quadros analíticos. Como conclusão, é inferido que nem sempre a reestruturação do negócio cooperativo tenderá a expressar um atomismo dos tomadores de decisão em relação às demandas institucionais do campo organizacional. Isso ocorreria uma vez que tais demandas são ambivalentes e precisam ser coordenadas conjuntamente na ordem para obterem um nível mínimo de legitimidade, que é necessária para a sobrevivência organizacional.

Palavras-chaves:

ação estratégica; ambivalência institucional; cooperativismo

1. Introduction

Dairy cooperative enterprises, characterized as complex organizations6 6 . Cooperatives are considered complex organizations because this type of enterprise presents a non-personified structure or, in others words, a diffuse property rights. Therefore, conflicts of interests are frequent. , have been incorporated more and more new competitive trends. However, it is known that by its nature, cooperatives are characterized as organizations of people with strong doctrinal aspects related to social characteristics.

It would be a project of which economic outcomes also result from the consolidation of the capacity of social relations among its members. Yet, there are institutional pressures related to social characteristics, but also technical competitive demands (economic). Managing these ambivalent institutional perspectives must be an inherent condition in the organizational structure of the cooperative business.

In the dairy sector, especially in development countries, milk production originates from small units (farms), fact that creates a potential for the emergence of cooperative organizations, not only as a way of increasing the power of forward negotiation to other actors in the production chain, but also to create its own chain. Despite this apparently favorable context for the consolidation of agricultural cooperatives in the framework of dairy production, recent indicators, according to Borgatti (2012)BORGATTI, M. T. O cooperativismo na cadeia do leite em Minas Gerais. Revista Indústria de Laticínios, v. 99, p. 30-31, 2010., show that such enterprises have seem difficulties in maintaining their activities and, consequently, its participation in the context of agribusiness. From this perspective, Chaddad (2007CHADDAD, F. R. Cooperativas no agronegócio do leite: mudanças organizacionais e estratégicas em resposta à globalização. Organizações Rurais & Agroindustriais, v. 9, n. 1, p. 69-78, 2007.) and others have noticed that the low competitiveness of dairy cooperatives is the result, among others, of an operational inefficiency in the social and economic context.

This inefficiency generates a direct impact on productivity, and consequently on the viability of the cooperative business. In this sense, it is possible to conclude that there is a notable multidimensional institutional pressure to those enterprises (cooperatives) at the dairy agribusiness. In this way, those uncorrelated requirements, imposed by the organizational environment, including intra-organizational context, can bring operational difficulties that will compromise the competitiveness of the collective enterprise in case of an unsatisfactorily managed (MEYER and ROWAN, 1977MEYER, J. W; e ROWAN, B. Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, v. 83, n. 2, p. 340-363, 1977.; GLOVER et al., 2014GLOVER, J. L. et al. An Institutional Theory perspective on sustainable practices across the dairy supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, v. 152, p. 102-111, 2014.).

If there is a difficulty in dairy cooperatives management, we should not arbitrate for generalizations. This occurs in view of the fact that there is also the evidence that some cooperative business can assimilate the environmental contingencies in order to ensure results to provide favorable conditions for the maintenance of economic and financial conditions, and in relation to the social embeddedness (SCHUMBERT and NIEDERLE, 2011SCHUMBERT, M. N; e NIEDERLE, P. A. A competitividade do cooperativismo de pequeno porte no sistema agroindustrial do leite no oeste catarinence. Revista Interfaces em Desenvolvimento, Agricultura e Sociedade, v. 5, n. 1, p. 188-216, 2011.).

This paper, appropriates of neo-institutionalism theoretical lens, assuming that the dairy cooperatives are required to legitimize. This happens by action of institutions existing in the organizational field. By organizational field we understood the perspective used by DiMaggio (1986)DIMAGGIO, P. J. Structural analysis of organizational fields: a blockmodel approach. Research in Organizational Behavior, v. 8, p. 335-370, 1986.. Thus, a field can be defined as the basic structure of correlations between organizations and societies, relations that are defining the actions taken by this group of actors who are situated in an interconnected relational environment.

In this sense, understanding the organizational field is a condition to comprehend how similar and differentiating functions arrange themselves within organizations with some interdependence (DIMAGGIO and POWELL, 1983DIMAGGIO, P. J; e POWELL, W. W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, v. 48, p. 147-160, 1983.). Accordingly, the issue of this research was formulated in the following question: How cooperative actors will respond to institutional complexity (multiple institutional constituents) in a dairy cooperative?

To answer this question, we considered the fact that ambivalent institutional demands emerge, in case of the dairy cooperatives, by influence of two mains subfields, and the strategic actions played by organizational actors related to this context (institutional ambivalence) are limited (RAAIJMAKERS et al., 2015).

This paper was divided into three main topics, besides this introduction. Firstly, a theoretical review context will take place regarding the governance of institutional management by hybrid organizations, such as cooperatives. The second will discuss the analytical theoretical model with the different possibilities to see how dairy cooperatives manage the ambivalent institutional perspectives. Finally, we will draw some conclusive points and directions for future researches.

2. The Governance in the Institutional Management of Hybrid Organizations

2.1 Literature review

The management of enterprises localized in different organizational fields or, in other words, that stayed in boundary positions (NILSSON, 2015NILSSON, W. Positive Institutional Work: Exploring Institutional Work Through the Lens of Positive Organizational Scholarship. The Academy of Management Review, v. 40, n. 3, p. 370-398, 2015.) and, therefore, in ambivalent institutional settings, is complex in many aspects. D’Aunno, Sutton and Price (1991)D’AUNNO, T; SUTTON, R. I; e PRICE, R. H. Isomorphism and external support in conflicting institutional environments: a study of drug abuse treatment units. Academy of Management Journal, v. 34, n. 3, p. 636-661, 1991.affirm that there is a great difficulty for hybrid organizations to respond values and different beliefs of each organizational environment (fields) to which it relates. On the other hand, according to Crubellate, Grave and Azevedo (2004CRUBELLATE, J. M; GRAVE, P. S; e AZEVEDO, A. M. A questão institucional e suas implicações para o pensamento estratégico. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, v. 8, n. 3, p. 37-60, 2004.), the organizations are able to strategically manage act in relation to these institutional demands.

Based on this context, the focus on governance is relevant, how it is managed in the context under discussion. The concept of governance permeates the definition used in Kraatz and Block (2008KRAATZ, M. S; e BLOCK, E. S. Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In: GREENWOOD, R. et al. (Eds.). The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. London: Sage, 2008, p. 243-275.). In the mentioned work, the term references the way that is designed the proposed project, and how this is implemented (control).

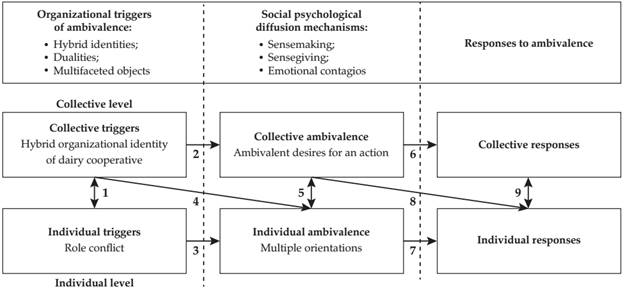

In relation to ambivalence of institutional demands, and in view of this, how is the formative interference between the proposal and control in organizations, therefore its governance. Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies (2014ASHFORTH, B. E; e REINGEN, P. H. Functions of dysfunction managing the dynamics of an organizational duality in a natural food cooperative. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 59, n. 3, p. 474-516, 2014.) trace levels by which this characteristic may intervene in the project scope, as well as the stage in which it appears the answers. Such levels can be seen in Figure 1.

Looking at Figure 1 it is possible to note that the ambivalence of the interposed levels of analysis may affect other level situated in the same perspective (individual or collective level). In this sense, having dualities in individual or organizational level, there will be an influence of one level in another.

Thus, by the prospect of Ashford et al. (2014)AMODEO, N. B. P. As cooperativas e o desafio da competitividade. Estudos, Sociedade e Agricultura, n. 17, p. 119-144, 2001., the existence of opposite configurations in a given level tends to trigger experiences in the practice sphere level in the same level (lines 2 and 3). If a dairy cooperative (collective level) is interposed in two subfields, on a practical level, such ambivalence is likely to manifest equally present also in individual perspective. No less important is the fact that the core collective essence of ambivalence may also trigger ambivalence in the individual field (line 4).

Finally, line 9 of Figure 1 reports that individual and collective responses cannot be seen separated, but traced as a complement to each other. Given this fact, an individual reactive action to an ambivalent context may also assist in collective action, and vice versa.

It implies, as noted by Scherer, Palazzo and Seidl (2013SCHERER, A. G; PALAZZO, G; e SEIDL, D. Managing Legitimacy in Complex and Heterogeneous Environments: Sustainable Development in a Globalized World. Journal of Management Studies, v. 50, n. 2, p. 259-284, 2013.), that social actors interpret such demands (collective and individual) and manage it in order to obtain the necessary legitimacy to the business survive. Moreover, as highlighted by Greenwood et al. (2011GREENWOOD, R. et al. Institutional Complexity and Organizational Responses. The Academy of Management Annals, v. 5, n. 1, p. 317-371, 2011.), there is an existence of a filter in the organizations, thus the pressures do not affect in the same way all enterprises. Therefore, it is incorrect to affirm that institutional pressures always entail in the same form of structuralization (atomic actors). Each organizational actor will do a self-awareness or critical understanding (NILSSON, 2015NILSSON, W. Positive Institutional Work: Exploring Institutional Work Through the Lens of Positive Organizational Scholarship. The Academy of Management Review, v. 40, n. 3, p. 370-398, 2015.) about this complexity.

Responses related to this critical understanding will be consubstantiated in the practical context. The framework designed by Oliver (1991OLIVER, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, v. 16, n. 1, p. 145-179, 1991.) tries to evidence which options organizational members can respond to a singular institutional demand (Table 1).

Walter, Augusto and Fonseca (2011WALTER, S. A; AUGUSTO, P. O. M; and FONSECA, V. S. O campo organizacional e a adoção de práticas estratégicas: revisitando o modelo de Whittington. Cadernos EBABE.BR, v. 9, n. 2, p. 282-298, 2011.) argued that these strategic actions do not refute the fact that organizations are guided by institutional pressures of the field. Thus, the strategic actions related to the ambivalent institutional demands are not an approximation of the instrumental rationality paradigm. Under different demands, originated in subfield with ambiguity demands, organizational actors invariably will have to act with a (strategic) view to help the enterprise to adapt to this context. Accordingly, such strategic adaptation can be implemented in different actions.

In this way, the responses drawn by Oliver (1991OLIVER, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, v. 16, n. 1, p. 145-179, 1991.), may, in accordance to Kraatz and Block (2008KRAATZ, M. S; e BLOCK, E. S. Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In: GREENWOOD, R. et al. (Eds.). The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. London: Sage, 2008, p. 243-275.), be “properly” used as an opportunity for organizational governance across the matted of responses expected by organizational environment (field) too in case of hybrid organizations.7 7 . According to Raaijmakers et al. (2015), Oliver’s (1991) framework has a focus on organizations with a singular institutional pressure. In this paper, we tried to adapt his framework to organizations with ambivalent institutional pressures.

Based on this context, we must recognize the manner in which the cooperative actions are performed in response to its paradoxical environmental demands is an important condition to understand how such enterprises may operate competitively.8 8 . In this paper the competitiveness concept was perceived as institutional arrangements that ensure the conditions of the enterprise to realize exchanges with other enterprises in the field (POWELL, 1991). This scenario will only occur in case of a legitimation. It is not, therefore, competitiveness achieved by technical instruments (Total Quality Management, Just In Time etc.). This recognition can help us tp understand the reasons why agricultural cooperative has been seen as synonymous of failure in many countries, as pointed by Planas and Valls-Junyent (2011PLANAS, J; e VALLS-JUNYENT, F. ¿ Por qué fracasaban las cooperativas agrícolas? Uma respuesta a partir del análisis de um núcleo de la Catalunã rabassaire. Investigaciones de Historia Económica, v. 7, p. 310-321, 2011.), and on other hand has achieved competitive levels (equal and/or higher economic results than perceived in the Investors Owned Firms - IOF) as mentioned by Battilani and Zamagni (2012BATTILANI, P; e ZAMAGNI, V. The managerial transformation of Italian co-operative enterprises 1946-2010. Business History, v. 54, n. 6, p. 964-985, 2012.).

Asserting that the institutional pressures are strategically interpreted by organizations actors is not likely to be considered a myth because they have been minimally observed empirically. In this regard, it is quoted Gouldner (1954GOULDNER, A. W. Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy. Glencoe: Free Press, 1954.), who puts notes related to the creation of representative patterns linked to organizational bureaucracy, and Selznick (1948SELZNICK, P. Foundations of the theory of organizations. American Sociological Review, v. 13, n. 1, p. 25-35, 1948.), by considering the various dilemmas to be observed in the management were classified as an important researcher in the Organizational Theory.

Moreover, to the extent that they are not myth, nor can be said that the issue is already minimally clarified, specifically in relation to the context of the hybrid organizations, Pache and Santos (2010PACHE, A; e SANTOS, F. When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, v. 35, n. 3, p. 455- 478, 2010.), Battilana and Dorado (2010BATTILANA, J; e DORADO, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: the case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, v. 53, n. 6, p. 1419-1440, 2010.), Pache and Santos (2013)PACHE, A. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Academy of Management Journal, v. 56, n. 4, p. 972-1001, 2013., Jarzabkowski, Lê and Van de Ven (2013JARZABKOWSKI, P; LÊ, J. K; e VAN DE VEN, A. H. Responding to competing strategic demands: how organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strategic Organization, p. 1-36, 2013.), Skelcher and Smith (2014SKELCHER, C; e SMITH, S. R. Theorizing hybridity: Institutional logics, complex organizations, and actor identities: The case of nonprofits. Public Administration, v. 93, n. 2, p. 433-448, 2014.) and others. It remains to note that this approach, in way to consider the macro and micro-environmental demands in context of the agricultural cooperatives, is still unknown.

Like this, it is increasingly urgent to understand how the collective nature of agricultural cooperatives are structured in relation to its hybrid character, which, as previously mentioned, are both their internally and in its organizational field (macro level). Mazzarol (2011MAZZAROL, T; LIMNIOS, E. M; e REBOUD, S. Co-operative Enterprise: a unique Business Model? In: Proceedings…Annual ANZAM Conference, 2011. New Zealand: Wellington, v. 25, p. 1-22, 2011.) and Cechin, Pascucci, Zylbersztajn and Omta (2013CECHIN, A. et al. Drivers of pro-active member participation in agricultural cooperatives: evidence from Brazil. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, v. 84, n. 4, p. 443-468, 2013.), in relation to this context, claim that there is a link missing in relation to the understanding of the management of the structural duality of cooperative business.

It is still unclear, and therefore a theoretical gap, the issues concerning to the process by which the agricultural cooperative is structured in response to the demands and external institutional prescriptions related to distinct demands. But not limited to external prescriptions, analyzes consider, jointly, such structuring in relation to intra-organizational context is also a matter to be clarified.

Thus, the institutional demand regarding the maintenance of the hybrid character of contemporary cooperative business is mainly caused by external interference, a need for credibility related to the organizational (sub)field, and by the need to manage such issues forward the claims of the various intraorganizational actors. It must be emphasized, specifically in relation to the internal context, which certainly ambivalent positions related to ideological perspectives of membership are present.

2.2 Importance of the Internal Environment (intra-organizational) in the Institutional Governance Process

Trying to elucidate feasible conditions to avoid internal legitimacy misconduct, and therefore undermine the strategic implementation focused on efficient management of ambivalent institutional provisions of subfields to which the organization is dependent, Pache and Santos (2010PACHE, A; e SANTOS, F. When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, v. 35, n. 3, p. 455- 478, 2010.) suggest some important points to considerer. In this sense, they advocate the necessity, as also highlighted by Ashford et al. (2014)AMODEO, N. B. P. As cooperativas e o desafio da competitividade. Estudos, Sociedade e Agricultura, n. 17, p. 119-144, 2001., to consider the existence of internal divergent ambitions, that is, not only as foreign institutional ambivalence can be represented internally, but also related to other ideological perspectives that can relate inside the organization.

The consideration of the internal formatting, with respect to membership, in the case of dairy cooperatives, may be the greater intervening variable to the consideration of strategies. If dairy farmers are not feeling represented in the organization, they will soon no longer send inputs to commercialization and it can probably lead to the enterprise’s bankruptcy. It is not possible, on these words, without a robust analysis, to infer an atomism related to the cooperative business, especially in relation to assume the institutions demanded by the organizational field passively. Therefore, given that the internal legitimacy is composed by considerable fraction in maintaining external legitimacy, it is not possible to affirm that the assimilation of new trend (new institutional demand) for the agricultural cooperatives is a passive isomorphic action.

However, the internal perspective will be intervening to the extent of its configuration, within the framework of existing psychosocial perspectives and the activism of the membership. Such representation may be established in three perspectives, as showed in Table 2.

Pache and Santos (2010PACHE, A; e SANTOS, F. When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, v. 35, n. 3, p. 455- 478, 2010.) believe that when there is presence of at least two ambivalent tendencies, attending only one of these perspectives is less usual. This would occur because each party would be able to monitor any symbolic fake action in relation to their expectations. In a dairy cooperative, composed by memberships with different ideological perspectives, a symbolic (fake) practice taken by decision makers tend to be less efficient.

If unusual, none can be said that it is not honored. Shojakahani (1994)SHOJAKHANI, M. Problems and prospects of co-operative movement in rural India. In: MADAN, G. R. (Ed.). Co-operative movement in India. New Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1994, p. 335-368. point out that the presence of membership in cooperative’s decisions, in some cases, are below the desired expectations, which would certainly favor symbolic practices by the enterprise management without adequate defense. Low participation, despite the influence of multiple sides, is therefore sufficient condition for internal decoupling actions.

By deduction, when the internal business perspective presents just defending a unique perspective, the most common action is serving only this demand. In this case, there is no discordant question given that managers tend to act with respect to this requirement, which in this case is only one.

In the existence of two or more active internal perspectives, as part of the dairy cooperative, it is expected that the strategy used to seek the attention of those prospects, even, aiming to avoid desertions from the deprecated part, is getting an understanding to meet the parties, an agreement. According to Smith and Lewis (2011SMITH, W. K;. and Lewis, M. W. Toward a Theory of Paradox: a dynamic equilibrium Model of Organizing. Academy of Management Review, v. 36, n. 2, p. 381-403, 2011.), the success of a particular enterprise will depend on the alignment between the internal and external environments. It concluded, therefore, that any strategic movement at the organizational level of dairy cooperatives, for the management of its hybrid nature, should invariably consider these two contexts.

2.3 What are the institutional pressures intervening in dairy cooperatives?

Considering the fact that the process of legitimacy may be by regulative, normative and/or cognitive formed (NILSSON, 2015NILSSON, W. Positive Institutional Work: Exploring Institutional Work Through the Lens of Positive Organizational Scholarship. The Academy of Management Review, v. 40, n. 3, p. 370-398, 2015.), we may draft two different main request source to legitimizing, in case of dairy cooperatives. We will call these contexts of subfields. It appears that would be two different main request sources related to dairy cooperatives: the first one is the agribusiness subfield (IOF demands), and the second is the cooperativism subfield. In the face of the impossibility to combine all possible sources of these institutional demands, we will draw a projection of the most symbolic in each context, in attendance to principles defended by Scott, 2001SCOTT, W. R. Institutions and organizations. Thousand: SAGE, 2001..

The cooperativism subfield was considered due to of the fact that, as can be seen in Hogeland (2015HOGELAND, J. A. Managing uncertainty and expectations: The strategic response of US agricultural cooperatives to agricultural industrialization. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, p. 1-12, 2015.), the interposed guidelines by the nature of cooperation, understood as the prospects aimed at mutual help for solving a common economic problem, present certain institutional inertia. Such inertia is denoted in the face of strong contextual changes with a view to a hegemonic mercantilist ideology. By deduction of such statements, it can be seen that the subfield of agribusiness was understood here as that organizational environment in which to introduce the capitalism oriented demands in the quest for profit, competitive advantage and selectivity those organizations more prepared to confront disputes in a market.

Based on the literature review was possible to summarize the main institutional demands (ceremonial rules) for dairy cooperatives enterprises (Table 3).

OLIVEIRA and SILVA, 2012OLIVEIRA, L. F. T; e SILVA, S. P. Mudanças institucionais e produção familiar na cadeia produtiva do leite no Oeste Catarinense. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 50, n. 4, p. 705-720, 2012.; GOMES, 2000GOMES, S. T. Economia da Produção do Leite. Belo Horizonte: Itambé, 2000., LEITE and GOMES, 2001LEITE, J. L. B; e GOMES, A. T. Perspectivas futuras dos sistemas de produção de leite no Brasil. In: GOMES, A. T; LEITE, J. L. B; e CARNEIRO, A. V. (Eds.). O agronegócio do leite no Brasil. Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA/CNPGL, 2001, p. 207-240.; GOMES, 2000JONES, D. C; e KALMI, P. Economies of Scale Versus Participation: a Co-operative Dilemma? Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, v. 1, n. 1, p. 37-64, 2012., OLIVEIRA and SILVA, 2012OLIVEIRA, L. F. T; e SILVA, S. P. Mudanças institucionais e produção familiar na cadeia produtiva do leite no Oeste Catarinense. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 50, n. 4, p. 705-720, 2012., GOMES, 2000GOMES, S. T. Economia da Produção do Leite. Belo Horizonte: Itambé, 2000., Somerville, 2007SOMERVILLE, P. Co-operative identity. Journal of Co-operative Studies, v. 40, n. 1, p. 5-17, 2007., NECK et al., 2009NECK, H. et al. The landscape of social entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, v. 52, p. 13-19, 2009., LEITE and GOMES, 2001LEITE, J. L. B; e GOMES, A. T. Perspectivas futuras dos sistemas de produção de leite no Brasil. In: GOMES, A. T; LEITE, J. L. B; e CARNEIRO, A. V. (Eds.). O agronegócio do leite no Brasil. Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA/CNPGL, 2001, p. 207-240., (LEITE and GOMES, 2000LEITE, J. L. B; e GOMES, A. T. Perspectivas futuras dos sistemas de produção de leite no Brasil. In: GOMES, A. T; LEITE, J. L. B; e CARNEIRO, A. V. (Eds.). O agronegócio do leite no Brasil. Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA/CNPGL, 2001, p. 207-240., VIEIRA FILHO and SILVEIRA, 2012VIEIRA FILHO, J. E. R; and SILVEIRA, J. M. F. J. Mudança tecnológica na agricultura: uma revisão crítica da literatura e o papel das economias de aprendizado. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 50, n. 4, p. 721-742, 2012., Verhofstadt and Maertens, 2014VERHOFSTADT, E; and MAERTENS, M. Smallholder cooperatives and agricultural performance in Rwanda: do organizational differences matter? Agricultural Economics, v. 45, n. S1, p. 39-52, 2014., PIRES, 2011PIRES, M. L. L. Cooperativismo e dinâmicas produtivas em zonas desfavorecidas. O caso das pequenas cooperativas agrícolas do Sul da França. Sociologias, n. 26, p. 228-261, 2011., ICA, 2017ICA - International Co-operative Alliance. Co-operative Principles. Available in: <Available in: https://ica.coop/en/what-co-operative

>. Accessed: 23 May. 2017 2017.

https://ica.coop/en/what-co-operative...

, TUNICK, 2009TUNICK, M. H. Dairy Innovations over the Past 100 Years. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, v. 57, n. 18, p.8093-8097, 2009., LEITE and GOMES, 2001LEITE, J. L. B; e GOMES, A. T. Perspectivas futuras dos sistemas de produção de leite no Brasil. In: GOMES, A. T; LEITE, J. L. B; e CARNEIRO, A. V. (Eds.). O agronegócio do leite no Brasil. Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA/CNPGL, 2001, p. 207-240., LEITE and GOMES, 2001LEITE, J. L. B; e GOMES, A. T. Perspectivas futuras dos sistemas de produção de leite no Brasil. In: GOMES, A. T; LEITE, J. L. B; e CARNEIRO, A. V. (Eds.). O agronegócio do leite no Brasil. Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA/CNPGL, 2001, p. 207-240.; TUNICK, 2009TUNICK, M. H. Dairy Innovations over the Past 100 Years. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, v. 57, n. 18, p.8093-8097, 2009., NAKHLA, 1995NAKHLA, M. Production control in the food processing industry: the need for flexibility in operations scheduling. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, v. 15, n. 8, p. 73-88, 1995., EBNETH and THEUNSEN, 2005EBNETH, O; e THEUNSEN, L. Internationalization and Corporate Success - Empirical Evidence from the European Dairy Sector. In: Proceedings… International Congress of the EAAE, XI, Denmark: Copenhagen, 2005.

It is important to highlight that the draft in the Table 3 not had the exhausting pretension to list institutional guidelines of these subfields, just constitute those more hegemonic in each institutional perspective. In this sense, it is necessary to inform that even some guidelines may belong to both subfields. In the distinction carried out here, it was considered only the most seminal notes linked to ontology of each chosen assumption.

If there are institutional isomorphic perspectives of both subfields highlighted, it is possible to see that some of the delimitations permeate contrasting or incompatible characteristics. The fact is that for the dairy cooperative enterprise to gain legitimation, and hence achieve the minimum levels of institutional competitive levels in the field (MEYER and ROWAN, 1977MEYER, J. W; e ROWAN, B. Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, v. 83, n. 2, p. 340-363, 1977.), it must conform itself in both subfields.

3. Discussion - the theoretical analytical model

In order to understand, assuming the condition that there is a strategic action (governance) related to the ambivalence of institutional demands filed to these enterprises, this paper takes some theoretical and analytical interpretations by summarizing the main susceptible action approaches to observe the context of dairy cooperatives.9 9 . When is pointed a strategic action in the governance of hybrid institutions by cooperatives, it is necessary to put out that these actions are not made by the business itself but by its intraorganizational actors. In fact, the business is an amorphous organization composed by its diverse actors (active actors). Oliver’s (1991OLIVER, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, v. 16, n. 1, p. 145-179, 1991.) theoretical framework was adopted as a guiding point of the discussions.

3.1 Institutional equilibrium

Ashforth and Reingen (2014ASHFORTH, B. E; e REINGEN, P. H. Functions of dysfunction managing the dynamics of an organizational duality in a natural food cooperative. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 59, n. 3, p. 474-516, 2014.) point out that it is better for any hybrid organization, if possible, to keep duality rather than try solving it. In the same sense, according to Pfeffer and Slančík (1978PFEFFER, J; e SLANCIK, G. R. The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. New York: Harper e Row, 1978.), to attend only a certain institutional demand violating other by which the organization has ties can create a loss of legitimacy, responsible for valuation of the organizational image in its operational environment.

Battilana and Dorado (2010BATTILANA, J; e DORADO, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: the case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, v. 53, n. 6, p. 1419-1440, 2010.), in relation to this context, profess that the best thing to be done, in relation to the sustainability of hybrid organizations, is to establish a balance among logics where the enterprise is located. Obtaining the institutional balance would be important, according to the researchers mentioned above, to prevent the formation of internal groups which may, by discontent or dominion preferences, create tensions related to the organization’s legitimacy in itself field (internal and external).

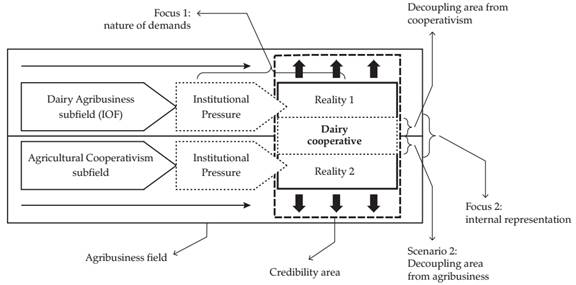

Figure 2 tries to demonstrate the strategic perspective of institutional equilibrium in a hypothetical case of a dairy cooperative situated at the agribusiness field. The main institutional pressures of both subfields considered will send its demands (institutional pressure) to the cooperative enterprise; furthermore, inside of the business probably will have the distinct ideological perspectives, related to the associate milk producers. In the institutional equilibrium strategy, the cooperative decision makers will try to attend these demands equally. As related by Bialoskorski Neto (2007BIALOSKORSKI NETO, S. Um ensaio sobre desempenho econômico e participação em cooperativas agropecuárias. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 45, n. 1, p. 119-138, 2007.), the social relations (cooperativism subfield) are important conditions to economic sustainability (dairy agribusiness subfield). The dotted rectangle, named credibility area, represents the result of this balance, the legitimacy obtained, responsible for the externalization of legitimizing standards expected by both subfields.

Schematic representation of the institutional equilibrium as a strategic action of a dairy cooperative

The institutional equilibrium action should be considered not only in relation to the external environment, in relation to the nature of institutional demands (Focus 1), but also to intraorganizational or internal representation (Focus 2). Specifically in relation to the internal context, Ashforth and Reingen (2014ASHFORTH, B. E; e REINGEN, P. H. Functions of dysfunction managing the dynamics of an organizational duality in a natural food cooperative. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 59, n. 3, p. 474-516, 2014.) showed that, likewise to the external environment, there may be ambivalent perspectives related to membership of agricultural cooperatives that must be considered when strategic definition is designed. Thus, Novkovic (2012NOVKOVIC, S. The balancing act: Reconciling the economic and social goals of co-operatives. In: Proceedings …International Summit of Cooperatives, 2012. Quebec: Quebec, 2012, p. 289-299 2012.) argues that whatever decision making in a cooperative must consider reaching of ambivalent perspectives.

3.2 Manipulation

The manipulation strategy occurs when the dairy cooperative enterprise practices becomes legitimized from its own influence in the field. In this perspective, the organization plays or implements practices not recognized by the organizational environment, but acts to change the current institutional order in its favor.

Moreover, a main effort to change or molding the institutional environment is developed from powerful organizations that through its network of relationships will act to change the current institutional arrangement which it deems convenient (MEYER and ROWAN, 1977MEYER, J. W; e ROWAN, B. Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, v. 83, n. 2, p. 340-363, 1977.). This would occur to the extent that, for example, large cooperatives act with the government to subsidize milk production and reduce the incidents taxes in milk production inputs. Include this approach to the form of pricing and payments, even if prevailing practices are others. By possessing strong symbolic power, the cooperative enterprise will not run the risk of suffering from a loss of legitimacy; instead, its influence can be highly representative to the point that all the institutional demands in the field are redesigned in relation to what is practiced by the organization.

Another aspect that can be observed within the scope of the manipulation strategy, already under an internal focus, could be realized when the majority of members decide to distribute financial results, and the direction of the enterprise works systematically, including by coercion, to allocate those resources in funds of the cooperative.

As an example that could be the implementation of the manipulation strategy is the case of Fonterra Cooperative Group. According to Gray and Heron (2010GRAY, S; e HERON, R. L. Globalising New Zealand: Fonterra Co-operative Group, and shaping the future. New Zealand Geographer, v. 66, p. 1-13, 2010.), Fonterra is a large company in the context of New Zealand economy, responsible for 93% of dairy production in that country. In this context, it is reasonable to assert that the organization has enough power to enforce its claims in the framework of the institutional demands of its business environment (organizational field) (FERRIER, 2004FERRIER, A. Opportunities and challenges of co-operative model. Business Review, v. 6, n. 2, p. 20-27, 2004.). This situation can be perceived by the direction of the darker arrows in the Figure 3. The darker arrows will confront the institutional pressures of both cooperative subfields and, for this, there will be a reorganization of these pressures (change in credibility area).

Schematic representation of the institutional manipulation as a strategic action of a dairy cooperative

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning the fact that in most developing countries, as the case of Brazil, the manipulation strategic action is rarer, specifically in the context of the dairy chain. In these places, some researchers have been noticed, as Magalhães (2007MAGALHÃES, R. S. Habilidades Sociais no Mercado de Leite. Revista de Administração de Empresas, v. 47, n. 2, p. 15-25, 2007.), that the dairy sector is composed by a large value chain as well as observations that cooperatives, in general, have a low influence (SAKSA et al., 2007SAKSA, J; JUSSILA, I; e TUOMINEN, P. Producer and Marketing Co-operatives: Institutional Contexts and Strategies. Journal of Co-operatives Studies, v. 40, n. 3, p. 5-13, 2007.).

3.3 Defiance

According to Oliver (1988OLIVER, C. The collective strategy framework: An application to competing predictions of isomorphism. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 33, n. 4, p. 543-561, 1988.), within the institutional isomorphism, the greatest discretion environment can be deterministic to business structuring. The predominant force in that organizational field or subfield in business activities would tend to make their prescriptions favored in relation to strategies by which organizations are structured.

Meyer and Rowan (1977MEYER, J. W; e ROWAN, B. Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, v. 83, n. 2, p. 340-363, 1977.) state that organizations located in a given organizational field are driven to the incorporation of practices and process defined as rational standards or expected standards. When the organization is following these prescriptions, it becomes legitimized by that applicant subfield with institutional strength, favoring their survival, even if such structuration may not be the optimal setting for the business in relation to other aspects.

In case of dairy cooperative, for example, that decide to implement practices based on the profit maximization, become legitimate more in the agribusiness subfield side, because this is necessary to attend a pathway required by financial institutions in case of the granting of loans for the capitalization of the business. Thus, there is a greater force in the context subfield of agribusiness non-cooperative (IOF institutional demands) rather than the subfield of cooperativism.

In this sense, it is possible to infer that, because the dairy agribusiness subfield contains more organizations, the cooperatives to take it as reference point in relation to demands should be followed (main point of isomorphic structuration). This tendency was accentuated mainly by intensification of competition, but also the incipience of instrumental management and qualified workers to structural peculiarities of the cooperatives. In case of workers, Jones e Kalmi (2012JONES, D. C; e KALMI, P. Economies of Scale Versus Participation: a Co-operative Dilemma? Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, v. 1, n. 1, p. 37-64, 2012.) noticed that, in most cases, they are not prepared to perform their activities from the business cooperatives peculiarities.10 10 . There would be deficiencies in forming the managers, which later incorporated into the management of collective enterprise would use instruments and metrics of its formation, and therefore not suitable for collective business features (agricultural cooperatives).

Defiance strategy would be one that most has been observed. A significant number of studies related to the analysis of the context of the agricultural cooperatives in general and specifically the dairy cooperatives, affirm there is a shift from cooperative to non-cooperative business environment. Puusa, Monkkonen and Varis (2013PUUSA, A; MONKKONEN, K; e VARIS, A. Mission lost? Dilemmatic dual nature of cooperatives. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, v. 1, p. 6-14, 2013.) observed that the cooperatives have been invariably assimilated capitalist tendencies instead of their ideological orientations. This fact would tend to lead this type of enterprise to become closer to other forms of business.

On the other hand, in some cases, the normative isomorphism would be responsible for a restructuring that will result in dislocation of the strategic actions of the cooperative to the business side. In this regard, Liang, Hendrikse, Huang and Xu (2015LIANG, Q. et al. Governance Structure of Chinese Farmer Cooperatives: Evidence From Zhejiang Province. Agribusiness, v. 31, n. 2, p. 198-214, 2015.) externalize a concern in relation to legislators. The inference is that, in most cases, they do not understand the peculiarities of cooperative business and, worse than that, do not update the law taking this aspect in consideration. The problematization of the cooperative in the legal framework should be, from this perspective, adjusted to the extent of environmental change, but while considering the specific structure of the cooperative nature.

Figure 4 tries to represent such contextualization schematically, in relation to defiance strategy in a dairy cooperative structure. For this, we assume the condition that the environmental legitimation in relation to business subfield (non-cooperative) is the priority action. It is possible to notice a movement of the enterprise in the dairy agribusiness subfield. The cooperative decision maker judges that attending the institutional pressure of this subfield is more important for the business to survive, for this the credibility is in this side (dotted rectangle). However, it is possible to perceive that there is a part of the institutional requirements that are not attended by this strategy.

Schematic representation of the institutional defiance as a strategic action of a dairy cooperative

Zucker (1987) draws that the risks of agricultural cooperatives purposefully implement a corporative guidance. According to this researcher, when the cooperative enterprise “copies” the structures and institutional demands and defies the cooperativism institutional demands (cooperativism subfield), with only financial gains and technical economic efficiency, it may generate a reverse effect.

This transition can undermine the social aspect, which will cause difficulties in coordinating and increases the free riding risk and, for this, increases the financial costs (NILSSON, SVENDSEN and SVENDSEN, 2012NILSSON, J; SVENDSEN, G. L. H; e SVENDSEN, G. T. Are large and complex agricultural cooperatives losing their social capital? Agribusiness, v. 28, n. 2, p. 187-204, 2012.). Furthermore, this conception does not refer to dairy cooperatives enterprises only, but to all organizations that develop transactions in recent context of market (TEBINI et al., 2014TEBINI, H. et al. Revisiting the Impacto f Social Performance on Financial Performance from a Global Perspective. International Journal of Business Science and Apllied Management, v. 9, n. 2, p. 30-50, 2014.).

Likewise, if there are accusations related to risks of defiance strategy by agricultural cooperatives, including those in dairy sector, especially in relation to a structural change guided by the side of the IOF business aspect, there are also defenses about this idea. For this, the defiance institutional strategy draws on a still controversial context and requires a better empirically understanding.

Under such contradictions inherent to a strong isomorphic IOF practices by agricultural cooperatives, a special case has been seen in case of geographic, member and operational expansion of the cooperative business. Cechin et al. (2013CECHIN, A. et al. Drivers of pro-active member participation in agricultural cooperatives: evidence from Brazil. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, v. 84, n. 4, p. 443-468, 2013.) and Nilsson et al. (2012NILSSON, J; SVENDSEN, G. L. H; e SVENDSEN, G. T. Are large and complex agricultural cooperatives losing their social capital? Agribusiness, v. 28, n. 2, p. 187-204, 2012.) argue that, in this case, there would be negative effects that hinder the definition of performance goals of the benefits of collective action, and thus would be inadequate ambition. However, this explanation is strikingly refuted by Serigati and Azevedo (2013SERIGATI, F. C; e AZEVEDO, P. F. Comprometimento, características da cooperativa e desempenho financeiro: uma análise em painel com as cooperativas agrícolas paulistas. Revista de Administração, v. 48, n. 2, p. 222-238, 2013.) and Bijman, Hendrikse and Van Oijen (2013)BIJMAN, J; e HU, D. The Rise of New Farmer Cooperatives in China: Evidence from Hubei Province. Journal of Rural Cooperation, v. 39, n. 2, p. 99-113, 2011.. They infer that such actions would bring gains of scale and scope, and consequently better returns to members.

3.4 Decoupling

Decoupling is understood as the process by which organizations maintain institutional compliance with the organizational subfields related to it, but at the same time build differentiated practices (gaps). These gaps have the purpose of circumvent the uncertainties with the technical activities generated by institutional provisions not fully adaptable (MEYER and ROWAN, 1977MEYER, J. W; e ROWAN, B. Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, v. 83, n. 2, p. 340-363, 1977.). About this strategy, Bromley and Powell (2012BROMLEY, P; e POWELL, W. W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: decoupling in the contemporary world. The Academy of Management Annals, v. 6, n. 1, p. 483-530, 2012.) understand that the decoupling is commonly understood as the gap between what is proclaimed by political (institutional) and what occurs in the practice.

The most correct way to do it in Whittington’s (1992WHITTINGTON, R. Putting Giddens into action: social systems and managerial agency. Journal of Management Studies, v. 29, n. 6, p. 693-712, 1992.) word was called alteration the course of action, which would be caused mainly by the ranking of demands to be prioritized, considering more than one action course as appropriate (different subfields emanating prescriptions). Emphasis should be made to the fact that, in this case, is the appearance of conformity that must be considered, and not the exact representation. Antonialli’s work (2000ANTONIALLI, L. M. Influência da mudança de gestão nas estratégias de uma cooperativa agropecuária. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, v. 4, n. 1, p. 135-159, 2000.) put practical light in this strategy when showed that in a dairy cooperative in Minas Gerais state, in Brazil, candidates to an electoral process emphasized changes in cooperative structuration, to improve social and economic characteristics, but, in the reality, they wanted to put a more entrepreneurial perspective in the cooperative.

In this sense, D’aunno et al. (1991D’AUNNO, T; SUTTON, R. I; e PRICE, R. H. Isomorphism and external support in conflicting institutional environments: a study of drug abuse treatment units. Academy of Management Journal, v. 34, n. 3, p. 636-661, 1991.) point out that the practice of decoupling in organizations located in hybrid fields (different subfields) would be carried out from the hierarchy (ranking) of the institutional demands to be followed, and those to be adapted to organizational reality. Therefore, it can be concluded that the decision makers do an analysis about what is expected from the external environment (external legitimacy), and how such actions will be perceived and implemented by the internal environment (internal legitimacy). In a preliminary analysis is that decisions are made and actions are taken.

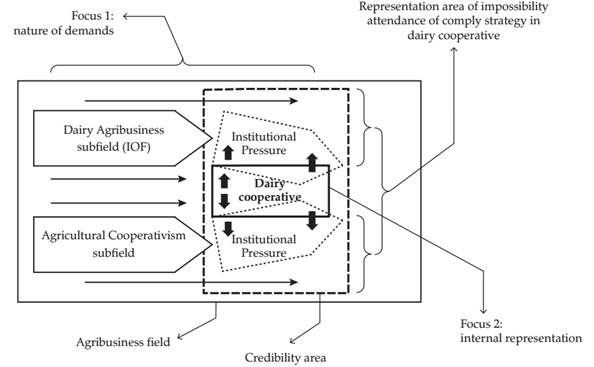

The obvious institutional paradox, in this perspective, can be solved by an institutional adaptation at the organizational level. Clearly, there is in this context a continuous need for integration and differentiation (LAWRENCE and LORSCH, 1967LAWRENCE, P. R; e LORSCH, J. W. Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 12, n. 1, p. 1- 47, 1967.). Organizational activities would apparently integrate with a view mainly to external and/or internal monitoring, but in reality, they would be different. In a practical decoupling case aiming at a possible externalization of meeting the institutional demands the organization tends to diffuse its structural and strategic setting at the intersection of the two subfields related to it. However, in the practical context, such actions would not be prevalent (Figure 5). It is emphasized that the decoupling in this case could be correlated to two realities (Reality I and II).

Schematic representation of the institutional decoupling as a strategic action of a dairy cooperative

The first one was named Reality 1: it is when the dairy cooperative is fully moved to the side of the agribusiness subfield (IOF). However, in a symbolic perspective it can maintain its legitimacy in relation to the organization of the cooperative subfield, making the decoupled area represented by Scenario 2.

The second context is when the cooperative moves completely to the subfield of cooperativism (Reality 2), but keeps an apparent presence, or a lesser extent than desired, within the subfield of corporate agribusiness. The symbolic party has legitimacy by means of the exposed area in Scenario 1.

In another extreme, the decoupling could also occur when the organization is apparently practicing the institutional isomorphism of the non-cooperative agribusiness field. In this sense, symbolically there would be a shift of strategic practices in regard to the requirements of organizational agribusiness subfield when in reality the organization could be closer to a balance (institutional equilibrium). The focus in this case would be a more legitimacy from IOF prescriptions. Thus, only an empirical analysis will be able to show which of the strategic perspectives are, in fact, proclaimed, and if there is a discrepancy of this in relation to what is adopted by the cooperative.

It remains to point out that the practice of the decoupling in the context of cooperative can still occur internally, especially analogous to its members. Organizational managers frequently use symbolic tools to acquire resources of its potential owners, in this case the associated (ZOTT and HUY, 2004ZOTT, C; and HUY, Q. How entrepreneurs use symbolic management to acquire resources. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 52, n. 1, p. 70-105, 2007.).

Suppose that the milk cooperative manager requires resources to invest on a new industrial plant to process goat milk. To achieve the financial resource to build a new plant, he would need an agreement of the members; this decision will must be democratically taken. For this he suggests that the business will be used by all members, when in fact the new plant can meet only members who provide certain type of milk. There is, in this case, a strategic action aiming at the internal decoupling for liberation of funds. To achieve these resources, some prerequisites with the managers of these cooperatives are necessary.

Such requirements were named by Zott and Huy (2007ZOTT, C; and HUY, Q. How entrepreneurs use symbolic management to acquire resources. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 52, n. 1, p. 70-105, 2007.) of interveners of the transfer symbolic action, and it can be broken down as follow: professional reputation manager or group of managers (credibility with the members), structuration of the business and its processes (professional organization), as the past performance could be used as justification to convince members, prestige or proximity to stakeholders (quality of relationships).

3.5 Comply

Comply strategy was defined by Oliver (1991OLIVER, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, v. 16, n. 1, p. 145-179, 1991.) as that action performed by decision makers to undertake all the institutional demands of the field simultaneously. In case of business located in organizational fields with ambivalent perspectives (hybrid subfields and hybrid enterprises), as the present case, it is believed that this perspective is unviable by the fact emphasized by Puusa et al. (2013PUUSA, A; MONKKONEN, K; e VARIS, A. Mission lost? Dilemmatic dual nature of cooperatives. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, v. 1, p. 6-14, 2013.). The mentioned authors affirm that is not possible to serve two lords with paradoxical desires at once.

As noticed above, there are institutional demands inconsistent with the two subfields of greater intervention (with symbolic power) in the actions of dairy cooperatives. Thus, there would be no conditions for organizational actors to meet all the institutional demands of these subfields given that some of them are mutually exclusive (Figure 6).

Schematic representation of the institutional comply as a strategic action of a dairy cooperative

Supposing that the decision makers of a dairy cooperative choose to prioritize larger farmer’s members, more milk supply capacity and, at the same time, defending the idea that the business will prioritize the equality principle to all members. In this case, the cooperative manager may try to meet both demands; however, because it is conflicting, this scenario will not be feasible in practice because conflicts will emerge and, as a consequence there would be loss of legitimacy between the subfields. Therefore, this strategy will not probably be practiced in organizations with hybrid institutional demands.

4. Conclusion

The central aim of this article was to develop an observation on how dairy cooperative members can manage the ambivalent institutional perspectives aimed at the formation of an organizational identity that guarantees them external and internal legitimacy necessary to maintain the minimum levels of organizational sustainability.

Furthermore, the theoretical lens in use started from the assumption that social relations are intervening variables on economic results, admitting, however, that such a process is not a passive action of the enterprise; in relation to its environment. Dairy cooperatives actors can act strategically, at least in four main forms11 11 . The institutional comply strategy not was considered. to manage their paradoxical institutional demands.

In fact, new perspectives are opened to complement or explain some empirical works, as visualized in Sander and Cunha (2013SANDER, J. A; e CUNHA, C. R. Atores sociais e campo organizacional: estratégias discursivas e de mobilização de recursos na construção do complexo avícola na Cooperativa Agroindustrial Copagril. RAM - Revista de Administração Mackenzie, v. 14, n. 4, p. 189-221, 2013.), related to the analysis of ambivalent institutions demands (intra and extra organizational) related to decision making in cooperatives, here, specifically dedicated, to dairy agribusiness context. Also in this sense, it is necessary to conduct empirical observations about how these strategic actions are perceived and managed by decision making actors.

Inferences drawn here complement the theory related to the understanding of the governance structure process of cooperative enterprises, but innovates, to infer that the search for attendance to conflicting demands (duality efficiency / social concern) can be designed from a multivariate (several strategic actions) and multidimensional focus. Multidimensional because it assumes that the figure of internal members and point the importance related to how they perceive and identify each one of the demands is also intervening variable under the governance of the business.

We also tried to update the focus of the central concepts of institutionalism recognizing the profusion of relationships among organizational fields, multidimensional analysis and organizational strategies. In the same way, we assume the inference that the inappropriate management of internal and external institutional conflicts are the main causes of bankrupt of a significant number of agricultural cooperatives in general, and specifically in the dairy sector. This occurs by loss of credibility and, consequently, the deformation of the organizational identity in their field.

On the other hand, there is also a contribution to the delimiters of cooperative theory on the recognition that not always a readjustment of structure and decisions, in response to environmental demands, is the result of a passive isomorphic assimilation of practices of IOF field or pre-stage of demutualization as pointed out by Amodeo (2013)AMODEO, N. B. P. As cooperativas e o desafio da competitividade. Estudos, Sociedade e Agricultura, n. 17, p. 119-144, 2001..

5. References

- AMODEO, N. B. P. As cooperativas e o desafio da competitividade. Estudos, Sociedade e Agricultura, n. 17, p. 119-144, 2001.

- ANTONIALLI, L. M. Influência da mudança de gestão nas estratégias de uma cooperativa agropecuária. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, v. 4, n. 1, p. 135-159, 2000.

- ASHFORTH, B. E. et al. Ambivalence in organizations: A multilevel approach. Organization Science, v. 25, n. 5, p. 1453-1478, 2014.

- ASHFORTH, B. E; e REINGEN, P. H. Functions of dysfunction managing the dynamics of an organizational duality in a natural food cooperative. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 59, n. 3, p. 474-516, 2014.

- BATTILANA, J; e DORADO, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: the case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, v. 53, n. 6, p. 1419-1440, 2010.

- BATTILANI, P; e ZAMAGNI, V. The managerial transformation of Italian co-operative enterprises 1946-2010. Business History, v. 54, n. 6, p. 964-985, 2012.

- BIALOSKORSKI NETO, S. et al Governança cooperativa e sistemas de controle gerencial: uma abordagem teórica de custos da agência. BBR - Brazilian Business Review, v. 9, n. 2, p. 72-92, 2012.

- BIALOSKORSKI NETO, S. Um ensaio sobre desempenho econômico e participação em cooperativas agropecuárias. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 45, n. 1, p. 119-138, 2007.

- BIJMAN, J. et al Agricultural cooperatives and value chain coordination. In: HELMSING, A. H. J; e VELLEMA, S. Value chains, inclusion and endogenous development Contrasting theories and realities. Oxford: Routledge, 2011, p. 82-101.

- BIJMAN, J; e HU, D. The Rise of New Farmer Cooperatives in China: Evidence from Hubei Province. Journal of Rural Cooperation, v. 39, n. 2, p. 99-113, 2011.

- BORGATTI, M. T. O cooperativismo na cadeia do leite em Minas Gerais. Revista Indústria de Laticínios, v. 99, p. 30-31, 2010.

- BROMLEY, P; e POWELL, W. W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: decoupling in the contemporary world. The Academy of Management Annals, v. 6, n. 1, p. 483-530, 2012.

- CAPPER, J. L. The environmental impact of dairy production: 1944 compared with 2007. Journal of Animal Science, v. 87, n. 6, p. 2160-2167, 2009.

- CECHIN, A. et al Drivers of pro-active member participation in agricultural cooperatives: evidence from Brazil. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, v. 84, n. 4, p. 443-468, 2013.

- CHADDAD, F. R. Cooperativas no agronegócio do leite: mudanças organizacionais e estratégicas em resposta à globalização. Organizações Rurais & Agroindustriais, v. 9, n. 1, p. 69-78, 2007.

- CRUBELLATE, J. M; GRAVE, P. S; e AZEVEDO, A. M. A questão institucional e suas implicações para o pensamento estratégico. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, v. 8, n. 3, p. 37-60, 2004.

- D’AUNNO, T; SUTTON, R. I; e PRICE, R. H. Isomorphism and external support in conflicting institutional environments: a study of drug abuse treatment units. Academy of Management Journal, v. 34, n. 3, p. 636-661, 1991.

- DIMAGGIO, P. J. Structural analysis of organizational fields: a blockmodel approach. Research in Organizational Behavior, v. 8, p. 335-370, 1986.

- DIMAGGIO, P. J; e POWELL, W. W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, v. 48, p. 147-160, 1983.

- EBNETH, O; e THEUNSEN, L. Internationalization and Corporate Success - Empirical Evidence from the European Dairy Sector. In: Proceedings… International Congress of the EAAE, XI, Denmark: Copenhagen, 2005.

- FERRIER, A. Opportunities and challenges of co-operative model. Business Review, v. 6, n. 2, p. 20-27, 2004.

- GHANBARI, M. et al Surveying on the Relationship between Organizational Factors and the Success of New Dairy Products Development in the Iran. European Journal of Business and Management, v. 6, n. 11, 2014.

- GLOVER, J. L. et al. An Institutional Theory perspective on sustainable practices across the dairy supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, v. 152, p. 102-111, 2014.

- GOMES, S. T. Economia da Produção do Leite Belo Horizonte: Itambé, 2000.

- GOULDNER, A. W. Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy Glencoe: Free Press, 1954.

- GRAY, S; e HERON, R. L. Globalising New Zealand: Fonterra Co-operative Group, and shaping the future. New Zealand Geographer, v. 66, p. 1-13, 2010.

- GREENWOOD, R. et al Institutional Complexity and Organizational Responses. The Academy of Management Annals, v. 5, n. 1, p. 317-371, 2011.

- HOGELAND, J. A. Managing uncertainty and expectations: The strategic response of US agricultural cooperatives to agricultural industrialization. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, p. 1-12, 2015.

- ICA - International Co-operative Alliance. Co-operative Principles Available in: <Available in: https://ica.coop/en/what-co-operative >. Accessed: 23 May. 2017 2017.

» https://ica.coop/en/what-co-operative - JARZABKOWSKI, P; LÊ, J. K; e VAN DE VEN, A. H. Responding to competing strategic demands: how organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strategic Organization, p. 1-36, 2013.

- JONES, D. C; e KALMI, P. Economies of Scale Versus Participation: a Co-operative Dilemma? Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, v. 1, n. 1, p. 37-64, 2012.

- KRAATZ, M. S; e BLOCK, E. S. Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In: GREENWOOD, R. et al. (Eds.). The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism London: Sage, 2008, p. 243-275.

- LAWRENCE, P. R; e LORSCH, J. W. Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 12, n. 1, p. 1- 47, 1967.

- LEITE, J. L. B; e GOMES, A. T. Perspectivas futuras dos sistemas de produção de leite no Brasil. In: GOMES, A. T; LEITE, J. L. B; e CARNEIRO, A. V. (Eds.). O agronegócio do leite no Brasil Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA/CNPGL, 2001, p. 207-240.

- LIANG, Q. et al. Governance Structure of Chinese Farmer Cooperatives: Evidence From Zhejiang Province. Agribusiness, v. 31, n. 2, p. 198-214, 2015.

- MAGALHÃES, R. S. Habilidades Sociais no Mercado de Leite. Revista de Administração de Empresas, v. 47, n. 2, p. 15-25, 2007.

- MAZZAROL, T; LIMNIOS, E. M; e REBOUD, S. Co-operative Enterprise: a unique Business Model? In: Proceedings…Annual ANZAM Conference, 2011. New Zealand: Wellington, v. 25, p. 1-22, 2011.

- MEYER, J. W; e ROWAN, B. Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, v. 83, n. 2, p. 340-363, 1977.

- NAKHLA, M. Production control in the food processing industry: the need for flexibility in operations scheduling. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, v. 15, n. 8, p. 73-88, 1995.

- NASSAR, A. M; e ZYLBERSZTAJN, D. Associações de interesse no agronegócio brasileiro: análise de estratégias coletivas. Revista de Administração, v. 39, n2, p. 141-152, 2004.

- NECK, H. et al The landscape of social entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, v. 52, p. 13-19, 2009.

- NILSSON, J; SVENDSEN, G. L. H; e SVENDSEN, G. T. Are large and complex agricultural cooperatives losing their social capital? Agribusiness, v. 28, n. 2, p. 187-204, 2012.

- NILSSON, W. Positive Institutional Work: Exploring Institutional Work Through the Lens of Positive Organizational Scholarship. The Academy of Management Review, v. 40, n. 3, p. 370-398, 2015.

- NOVKOVIC, S. The balancing act: Reconciling the economic and social goals of co-operatives. In: Proceedings …International Summit of Cooperatives, 2012. Quebec: Quebec, 2012, p. 289-299 2012.

- OLIVEIRA, L. F. T; e SILVA, S. P. Mudanças institucionais e produção familiar na cadeia produtiva do leite no Oeste Catarinense. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 50, n. 4, p. 705-720, 2012.

- OLIVEIRA, M. M. As circunstâncias da criação da extensão rural no Brasil. Cadernos de Ciência & Tecnologia, v.16, n.2, p. 97-134, 1999.

- OLIVER, C. The collective strategy framework: An application to competing predictions of isomorphism. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 33, n. 4, p. 543-561, 1988.

- OLIVER, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, v. 16, n. 1, p. 145-179, 1991.

- ÖSTERBERG, P; e NILSSON, J. Members’ perception of their participation in the governance of cooperatives: the key to trust and commitment in agricultural cooperatives. Agribusiness, v. 25, n. 2, p. 181-197, 2009.

- PACHE, A; e SANTOS, F. When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, v. 35, n. 3, p. 455- 478, 2010.

- PACHE, A. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Academy of Management Journal, v. 56, n. 4, p. 972-1001, 2013.

- PFEFFER, J; e SLANCIK, G. R. The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. New York: Harper e Row, 1978.

- PIRES, M. L. L. Cooperativismo e dinâmicas produtivas em zonas desfavorecidas. O caso das pequenas cooperativas agrícolas do Sul da França. Sociologias, n. 26, p. 228-261, 2011.

- PLANAS, J; e VALLS-JUNYENT, F. ¿ Por qué fracasaban las cooperativas agrícolas? Uma respuesta a partir del análisis de um núcleo de la Catalunã rabassaire. Investigaciones de Historia Económica, v. 7, p. 310-321, 2011.

- POWELL, W. W. Expanding the scope of institutional analysis. In: POWELL, W. W; e DIMAGGIO, P. J. (Eds.). The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991, p. 183-203.

- PUUSA, A; MONKKONEN, K; e VARIS, A. Mission lost? Dilemmatic dual nature of cooperatives. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, v. 1, p. 6-14, 2013.

- SAKSA, J; JUSSILA, I; e TUOMINEN, P. Producer and Marketing Co-operatives: Institutional Contexts and Strategies. Journal of Co-operatives Studies, v. 40, n. 3, p. 5-13, 2007.

- SANDER, J. A; e CUNHA, C. R. Atores sociais e campo organizacional: estratégias discursivas e de mobilização de recursos na construção do complexo avícola na Cooperativa Agroindustrial Copagril. RAM - Revista de Administração Mackenzie, v. 14, n. 4, p. 189-221, 2013.

- SCHERER, A. G; PALAZZO, G; e SEIDL, D. Managing Legitimacy in Complex and Heterogeneous Environments: Sustainable Development in a Globalized World. Journal of Management Studies, v. 50, n. 2, p. 259-284, 2013.

- SCHUMBERT, M. N; e NIEDERLE, P. A. A competitividade do cooperativismo de pequeno porte no sistema agroindustrial do leite no oeste catarinence. Revista Interfaces em Desenvolvimento, Agricultura e Sociedade, v. 5, n. 1, p. 188-216, 2011.

- SCOTT, W. R. Institutions and organizations Thousand: SAGE, 2001.

- SELZNICK, P. Foundations of the theory of organizations. American Sociological Review, v. 13, n. 1, p. 25-35, 1948.

- SERIGATI, F. C; e AZEVEDO, P. F. Comprometimento, características da cooperativa e desempenho financeiro: uma análise em painel com as cooperativas agrícolas paulistas. Revista de Administração, v. 48, n. 2, p. 222-238, 2013.

- SHOJAKHANI, M. Problems and prospects of co-operative movement in rural India. In: MADAN, G. R. (Ed.). Co-operative movement in India New Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1994, p. 335-368.

- SKELCHER, C; e SMITH, S. R. Theorizing hybridity: Institutional logics, complex organizations, and actor identities: The case of nonprofits. Public Administration, v. 93, n. 2, p. 433-448, 2014.

- SMITH, W. K;. and Lewis, M. W. Toward a Theory of Paradox: a dynamic equilibrium Model of Organizing. Academy of Management Review, v. 36, n. 2, p. 381-403, 2011.

- SOMERVILLE, P. Co-operative identity. Journal of Co-operative Studies, v. 40, n. 1, p. 5-17, 2007.

- TEBINI, H. et al. Revisiting the Impacto f Social Performance on Financial Performance from a Global Perspective. International Journal of Business Science and Apllied Management, v. 9, n. 2, p. 30-50, 2014.

- TUNICK, M. H. Dairy Innovations over the Past 100 Years. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, v. 57, n. 18, p.8093-8097, 2009.

- VERHOFSTADT, E; and MAERTENS, M. Smallholder cooperatives and agricultural performance in Rwanda: do organizational differences matter? Agricultural Economics, v. 45, n. S1, p. 39-52, 2014.

- VIEIRA FILHO, J. E. R; and SILVEIRA, J. M. F. J. Mudança tecnológica na agricultura: uma revisão crítica da literatura e o papel das economias de aprendizado. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v. 50, n. 4, p. 721-742, 2012.

- WALTER, S. A; AUGUSTO, P. O. M; and FONSECA, V. S. O campo organizacional e a adoção de práticas estratégicas: revisitando o modelo de Whittington. Cadernos EBABE.BR, v. 9, n. 2, p. 282-298, 2011.

- WHITTINGTON, R. Putting Giddens into action: social systems and managerial agency. Journal of Management Studies, v. 29, n. 6, p. 693-712, 1992.

- ZOTT, C; and HUY, Q. How entrepreneurs use symbolic management to acquire resources. Administrative Science Quarterly, v. 52, n. 1, p. 70-105, 2007.

- ZUGKER, L. G. Institutional theories of organization. Annual Review of Sociology, v. 13, p. 443-464, 1987.

-

6

. Cooperatives are considered complex organizations because this type of enterprise presents a non-personified structure or, in others words, a diffuse property rights. Therefore, conflicts of interests are frequent.

-

7

. According to Raaijmakers et al. (2015), Oliver’s (1991) framework has a focus on organizations with a singular institutional pressure. In this paper, we tried to adapt his framework to organizations with ambivalent institutional pressures.

-

8

. In this paper the competitiveness concept was perceived as institutional arrangements that ensure the conditions of the enterprise to realize exchanges with other enterprises in the field (POWELL, 1991). This scenario will only occur in case of a legitimation. It is not, therefore, competitiveness achieved by technical instruments (Total Quality Management, Just In Time etc.).

-

9

. When is pointed a strategic action in the governance of hybrid institutions by cooperatives, it is necessary to put out that these actions are not made by the business itself but by its intraorganizational actors. In fact, the business is an amorphous organization composed by its diverse actors (active actors).

-

10

. There would be deficiencies in forming the managers, which later incorporated into the management of collective enterprise would use instruments and metrics of its formation, and therefore not suitable for collective business features (agricultural cooperatives).

-

11

. The institutional comply strategy not was considered.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Oct-Dec 2017

History

-

Received

16 Nov 2015 -

Accepted

20 July 2017

Source Adapted from

Source Adapted from  Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.

Source Authors’ elaboration.