Abstracts

While observing the city of Sao Paulo, it is easy to perceive that it has come to a real collapse. A dramatic inequality dominates, what makes that, at least, the third part of its population live in shameful conditions. At the same time, its economic power leverages an uninterrupted growth that paradoxically deepens its problems: pollution, floods, insecurity, precarious public transportation, and traffic jams are some of the "wounds" that characterize this city. What are the causes of this urban tragedy? They rely on the logic of the Patrimonialistic State, on a society that has never managed to overcome its slavery heritage, and on a state order that permanently consolidates the conservative modernization. And what could be the path to its solution? It demands a radical change in the logic of the city functioning, in the dynamics of the Patrimonialistic State which, in its turn, depends on profound and necessary individual changes.

Unequal urbanization; Social apartheid; Space of conflicts

Ao observar a cidade de São Paulo, é fácil perceber que ela vive verdadeiro colapso. Impera uma dramática desigualdade, que faz que ao menos um terço de sua população viva em condições indignas. Ao mesmo tempo, sua pujança econômica alavanca um ininterrupto crescimento que, paradoxalmente, aprofunda seus problemas: poluição, enchentes, insegurança, transportes precários, congestionamentos são algumas das mazelas que hoje caracterizam a cidade. Quais as causas dessa tragédia urbana? Elas se encontram na lógica do Estado patrimonialista, de uma sociedade que nunca conseguiu vencer sua herança escravocrata, e de uma ordem estamental que consolida permanentemente a modernização conservadora. E qual é o caminho para sua solução? Ele está na necessidade de uma radical mudança na lógica de funcionamento da cidade, nas dinâmicas de funcionamento do Estado patrimonialista, que dependem, por sua vez, de profundas e necessárias mudanças individuais.

Urbanização desigual; Apartheid social; Espaço de conflitos

DOSSIER SÃO PAULO, TODAY

São Paulo: The city of intolerance or urbanism "Brazilian style"

João Sette Whitaker Ferreira

ABSTRACT

While observing the city of São Paulo, it is easy to perceive that it has come to a real collapse. A dramatic inequality prevails, causing at least one third of its population to live in shameful conditions. At the same time, its economic power leverages an uninterrupted growth that paradoxically deepens its problems: pollution, floods, insecurity, precarious public transportation, and traffic jams are some of the "wounds" that characterize this city. What are the causes of this urban tragedy? They rely on the logic of the Patrimonialist State, in a society that has never managed to overcome its slavery heritage, and on a state order that permanently consolidates conservative modernization. And what could be the path to its solution? It demands a radical change in the logic of the city's functioning, in the dynamics of the Patrimonialist State which, in turn, depends on profound and necessary individual changes.

Keywords: Unequal urbanization, Social apartheid, Space of conflicts.

" almost black or almost white, or almost black because so poor. And poor people are like rotten people and everyone knows how blacks are treated..." (Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, Haiti)

The city is a space of conflict. Human civilization, in its extraordinary capacity to generate unequal societies, has always produced equally unjust cities. Their configuration, their design, their effectiveness as a shelter and production space, their ability to promote quality of life for some or for all will depend on the social and economic dynamics and correlations of forces in each historical moment. São Paulo, one of the five largest metropolises in the world, expresses the disputes and conflicts of the capitalist city, with the aggravating factor of also displaying the peculiar contradictions of underdevelopment.

The production of urban space responds to a logic in which primarily the State, the market and civil society interrelate. The tension lies in the fact that the market seeks profit through land and property appreciation, while civil society is more interested in the use value of urban land. In the capitalist city this tension gets worse, since class differentiation and the possibility of each class appropriating unequally valued areas causes the scale to invariably tip to the side of the dominant class, which can buy land in the most privileged areas. It would be up to the State to regulate land use and occupation, so as to avoid this imbalance, restrict speculative overvaluation and ensure democratic access to the city by a larger portion of society.

It just happens that the appreciation of land and property in capitalist cities is paradoxically leveraged by the State itself. The value of urban land is determined by its location, which in turn is defined by the availability of infrastructure (Villaça, 2001): a plot of land is more expensive because there is "more city" around it, i.e., access avenues and public transportation and sewage, water, electricity and garbage collection services. However, infrastructure is produced by the State. Therein rests the fundamental contradiction of the capitalist city: a property only has value because of a complex network of infrastructure, which is built with public investment. Thus, the appreciation of land resulting from collective, public investment, is appropriated individually by those who can "pay for the location" (Deák, 1989). Therefore, the role of the State should be that of regulating and mediating this antagonism between the market and society: ensuring a homogeneous production of infrastructure, avoiding the exclusion of lower income layers of the population, building facilities accessible by all, and recovering, through taxes, part of the profit earned by the market as a result of public investments, the socalled "urban added value".

It seems understandable that in the core countries of capitalism this regulation has occurred, to a greater or lesser degree, within the scope of the Social Welfare State. It is obvious that public policy intervention in land use through laws and administrative procedures termed "urban instruments" occurred gradually, while the European industrial bourgeoisie consolidated its economic power from the nineteenth century, with the objective and by no means philanthropic role of streamlining the cities in order to turn them into an effective instrument of accumulation. In the postwar decades, the Keynesian economic interventionism was reflected in spatial terms, with the State guaranteeing certain equality in land appropriation and use by providing facilities, services and housing (the large housing complexes) required for the "social wellbeing" of the population, which in fact would leverage a mass consumption market.

If the Welfare State fulfilled this role in core countries at its time by consolidating the desired consumer market, that does not mean, it is worth noting, that the model has been maintained to date. After the productive restructuring of the 1970s and the consolidation of the globalized financial capitalism of a neoliberal character, even in those countries the "wellbeing" and universal rights provided by the State succumbed to the hegemony of the market economy that favors corporations and exacerbates income concentration, promotes the exclusion of the poorest (mainly immigrants) from social benefits, strengthens increasingly authoritarian and chauvinist governments, and where cases of misuse of the public apparatus and corruption are becoming increasingly frequent. If we haven't, to this day, imported the idea of a "public" State such as theirs, it is acceptable to say, today, that it is the core countries that are now being inspired by our model of conservative modernization. With regard to the cities, there is no doubt that the situation is unique: as put by Mike Davis, the world today is a slum planet.

But if at least until the 1980s the Welfare State gave some meaning to the "public" and leveraged some regulation of the urban, this never happened in the periphery of the capitalist system. Several interpreters of the Brazilian formation have shown that in our country the concept of "public" is not exactly faithful to its original meaning. The Brazilian State, in its patrimonialist bias (Faoro, 2001) confuses the public with the private in the defense of the interests of the elites, and this equation has dramatically affected the our urbanization model.

So, when during the nineteenth century our cities gained importance, not as a locus of production itself, but rather of command of the agroexporting economy (Oliveira, 1977), in the absence of a regulatory Welfare State, public investments in infrastructure were clearly concentrated in the areas occupied by highincome sectors, spearheaded by the interests of the real estate market (Villaça, 2001). Its absence in the rest of the city was not due to some "inability" of the rulers as repeatedly mooted but rather to an effective sociospatial segregation policy. In the peculiar logic of underdevelopment, the government, without the meaning of public in developed democracies, disguises itself in the logic of "misplaced ideas" (Schwarz, 2000) and becomes a "nonState" of patrimonialist character, marked by the interference of the interests of the dominant, which perfected the state apparatus as an instrument at their service, and fed on backwardness as leverage to their hegemony.

This peculiar State within the urban scope does not plan actions to overcome backwardness but rather confuses them; it does not organize but rather disorganizes; it does not facilitate but rather scrambles bureaucratic and administrative procedures; it is not ethical but tolerates favor and clientelism, not because it is incompetent but because it is extremely effective in its goal of obstructing a more equitable, inclusive and redistributive urban development that could tip the balance of political forces. The accelerated industrialization and urbanization "with lowwages" of the 1950s to the 1970s (Maricato, 1996) generated the socalled "exclusionary modernization" (Maricato, 1997), i.e., significant economic growth but conditional on the maintenance of poverty. At the urban level it resulted in a pattern of absolute sociospatial segregation, with investments only in the hegemonic city, which we term "unequal urbanization" model.

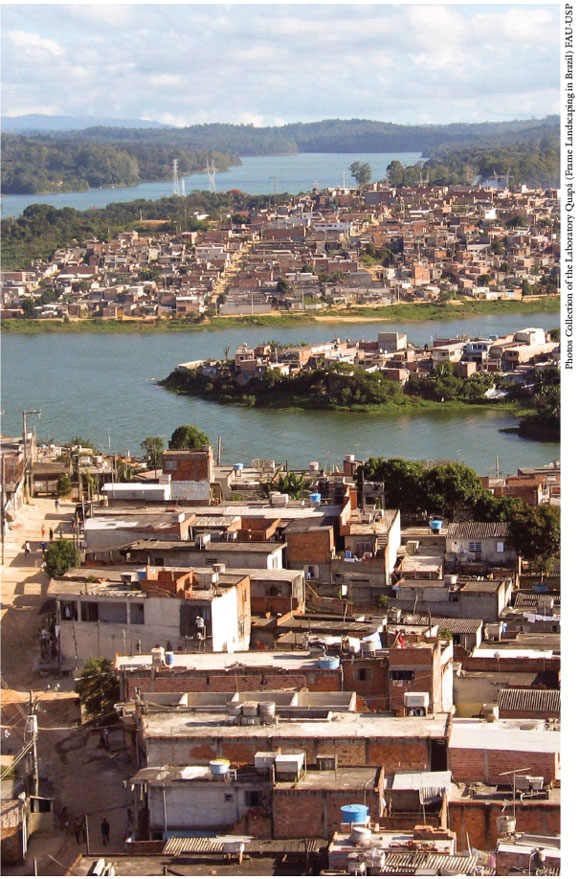

The metropolis of São Paulo is the result of this process. If it is not the only one because this pattern is repeated in all our cities it is perhaps the most exacerbated case and an unfortunate model for the rest of the country. The effects of exclusionary modernization are seen in the strong antagonism between areas of the city that are well regulated, benefit from public investments and the object of intense formal housing initiatives, and others subject to abandonment and marked by precariousness. It is not true that this dichotomy is expressed within the territory by a geographical division between the rich center and the poor periphery. Informal settlements also multiply in the interstices of the hegemonic city, in abandoned land, under the bridges, on the borders of streams. But in fact they extend mainly over regions that are more distant from the center. Throughout the twentieth century, the poorest population, with no housing options, settled in a distant "exile in the periphery" (Maricato, 2001), where the cost of location is lower.

This endless jumble of houses and shacks reflects what, in the patrimonialist State, was the "best" housing policy, i.e., the "nonpolicy", leaving to the poorest population the solution of selfconstruction as a result of the lack of housing options, the impossibility of access to urbanized land, and the action of squatters that disseminate informal occupation. As already mentioned by Francisco de Oliveira (2003, p.9), a very functional solution from the standpoint of the needs of accumulation: the reservoir of labor made up of the mass of immigrants in search of work was "part also of the means to lower the reproduction cost of the urban labor force", with slums and clandestine settlements as a housing "solution" for the poor that reduced "the monetary cost of their own reproduction" (ibid, p.130).

So, while the wealthy neighborhoods of São Paulo benefited from permanent modernization, the urbanization pattern for the poorest starting from the industrial boost associated with the "economic miracle" was the occupation of outlying urban areas by immigrant workers, whose low wages did not allow them access to formal housing through home ownership. Masons and carpenters full of wisdom (for theirs is the labor that to this date still raises the formal city), who alone built the periphery with more skill than one might imagine, since the precarious conditions of these settlements could otherwise generate even more tragedies than those we have seen year after year with the arrival of the summer rains. But where there is no government to prohibit, regulate, inspect, or even prepare the soil for the construction of houses, it is impossible to prevent the occupation of unsafe slopes, borders of streams subject to flooding, leaving this population very vulnerable to natural disasters. In recent decades, with the depletion of urbanizable areas, the most environmentally frail regions, in principle protected by law, have become even more distant settlement alternatives.

By sprawling the city this way, unequal urbanization is increasingly pushing the working population away from the centers of employment. Due to the precarious conditions of the transport available, it is not unusual for workers to spend five to six hours a day commuting back and forth between the periphery and the center.1 1 . Simulation through the website < http://www.sptrans.com.br/itinerarios> of SPTrans shows, for example, that it would take 2h51min in nonrush hours and by bus, but also by subway, to go from João Felipe Street in Jd. São Luiz, next to Rio de Janeiro slum, to Itambé Street in Moema. From Porto do Bezerra Street (Lajeado, East Zone) to Faria Lima Avenue (West Zone), the bus trip would take 2h23 min, according to SPTrans. A real test between Pinheiros (West Zone) and Jd. Angela (South Zone) during the rush hour (6.p.m) and on a rainy day took 3h20 min by bus only. A diseconomy that is incomprehensible in the case of the most important city of such a rich country, i.e., allowing its active labor force to waste more than half a workday each day in stressful journeys on overcrowded buses and trains. Incomprehensible in terms of economic rationality, yet perfectly explained by the incongruous logic of underdevelopment.

The result of this situation is discouraging. According to a survey conducted by the municipality in 2004,2 2 . "Balanço qualitativo de gestão: 20012004", Sehab / PMSP. It was estimated in 2004 that 1.2 million people lived in slums and about 1.8 million in settlements. Although not precise, the number of people living in tenements and in the streets could reach half a million. about 3.5 million people were living in informality, i.e., in lots in the periphery, slums, tenements, or even in the street. If we also consider the large number of people living in precarious, although regularized houses, the number of São Paulo residents deprived of a decent life will probably be much higher.

The discussion of the problems of São Paulo, however, is not limited to just observing the plight of precarious settlements as if, by contrast, the richest regions of the city were well urbanized. This reasoning hides a dichotomy, as if each side rich and poor existed by itself, independent of the other, when in fact they both interact and feed themselves in a dynamic of codependency. Far from perfect, affluent neighborhoods, even with all the investments they receive, promote an occupation of the territory that is as or more harmful than that of the periphery. Extreme luxury, electrified walls, soil sealing in their garages, all express the taste of the elites for a lifestyle that rejects the city and is selfdestructive.

The walls segment the urban, eliminate the vitality of the streets and kill them as conviviality spaces; public green areas are neglected, since those internal to gated communities already meet the needs of those who can afford them; the preferred use of the private car one of the largest sources of emission of pollutants that man has ever produced is so abusive that on bridges, tunnels and viaducts built with public money, buses are prohibited from operating! But in the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo (MRSP), daily trips by private car or taxi represent only 31 percent of the total, and 69 percent are made by public transport or on foot!3 3 . Origin and Destination Survey OD SPMetro, 2007. Still, almost R$2 billion were spent in 2010 to expand the marginal roads along the Tietê River, when this money would have enabled building about 10 kilometers of subway tracks. Favoring road works for private cars over public transportation would be incomprehensible if it were not consistent with the logic of unequal urbanization. Brazilian urban engineering has specialized in building valley bottom avenues, channeling and plugging rivers and streams to the point that nobody knows where they are anymore. The freedom afforded to the real estate market leads to the mangling of old neighborhoods, which are victims of uncontrolled vertical growth, to soil sealing, and to the collapse of water drainage and runoff systems, as shown each year by endless flooding during the rainy season.

This urbanism that destroys the possibility of a more humane and just city was neither the result of chance nor is it natural to large cities, as common sense might lead one to believe. Our peculiar State has been transformed, over the years, into a welloiled machine to promote unequal urbanization. It is not for lack of laws that the city destroys itself; quite the contrary. But in Brazil what is too much for some is condescending for others, and if the violation of the property of others is strongly curbed when it comes to the occupation by housing movements of a property that has been vacant for years (without fulfilling its social function), such energy is not seen in the case of the much less legitimate occupation perpetrated by highincome sectors. It is known that a large stretch of public area in the Ibirapuera Park, along República do Líbano Avenue has been taken by mansions that are still there. If 30 percent of the area of one of the most important horizontal gated communities in the Metropolitan Region was built on indigenous lands of the Union, this is not really a problem. There is a tax that legitimizes the situation and authorizes the use of the land. When an exhibition center of the city is built on a vacant municipal area, without the slightest embarrassment, there are no police forces there enforcing repossession.

São Paulo is the city of different checks and balances, whether in the priority of public investments, in the variable strictness of law enforcement, in the huge difference between housing for the wealthier and poorer classes, or in the lack of action in the face of the predatory dynamics of urbanization. It is also the city of indifference: the exclusion of the poorest produces a perverse logic in which the dominant classes nourish the idea that the city operates by itself, ignoring the fact that it is an important and poor population that puts it into motion, but has to disappear once the service is completed. But São Paulo is, above all, the city of intolerance: contempt, disregard for the living conditions of the poorest and their demands are also motivated by well determined although concealed policies and actions. And this brings up the feeling of a kind of apartheid, not exactly that of South Africa, but a spatial version of a state, institutionalized structure that segregates the poor and is intolerant of poverty.

There is actually racism in Brazil, different also from the racism practiced in South Africa during the apartheid regime ... because our racism is, to use a wellknown word, subtle. It is covert. Because it is subtle and covert it does not mean that it makes less victims than the one that is overt. (Munanga, 2008)

If there is, as indicated by professor Kabenguele Munanga, a kind of existing, yet not confessed "racism Brazilian style", it is easy to assume that it is expressed also in the spatial configuration. Researchers Eduardo Rios and Juliana Riani (2007), from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) have shown that in São Paulo, in 2000, the areas that concentrate the richest layers and where the percentage of poor varies (according to the weighted areas) from 1.6 percent to 9.6 percent of the population are also those where the percentage of blacks is always less than 13.7 percent of the population, reaching 3.8 percent in some areas. The outlying neighborhoods, where most precarious settlements are located, with a population of poor ranging from 19.8 percent to 58.6 percent, are also the neighborhoods of blacks, who represent between 26 percent and 58 percent of the population.4 4 . "Proporção de pessoas negras, pobres e indigentes por área de ponderação São Paulo, 2000" (see Rios & Riani, 2007). Considering the ethnic and geographic origin and the segregation of and prejudice towards migrants from the Northeast who have built the city since the midtwentieth century, the correlation between racialethnic and social segregation becomes even more evident.

There is not much difference between overt racism and the forces that move the city based on the logic of intolerance of poverty. Clubs frequented by the high society of São Paulo do not accept blacks as members, even if covertly. But they also require nannies, either black or from the Northeast, but all poor, to wear white uniforms and prohibit them from entering their restaurantes.5 5 . See article in the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, 27 February 2011: " Clube obriga babá a usar branco e barra ida a restaurante", by Cristina Moreno Castro. As explains Antonio Sergio Guimarães (1999, p.15),

Brazilian racism is inextricably linked to a state structure that naturalizes it, and not to the class structure, as previously thought. In fact, also class inequalities are legitimized by the state order. Combating racism, therefore, begins by combating the institutionalization of the inequalities of individual rights.

This estate of the realm, to which the mechanisms of domination of the patrimonialist State contribute, seeks its roots in conservative modernization, whose characteristic is not having broken, at any time in history, the balance of forces that ensures the hegemony of the elites, as observed by Guimarães (1999, p.14): "the hierarchical order, whether of classes or race, on which the slave society in Brazil was founded, has not been entirely broken." Its ideological force is measured by how it is accepted as natural by the dominated.

Given the subtleness of the "Racism Brazilian style", the intolerance of poverty in the construction of the urban opens widely, to whoever wants to see it, in countless examples that, however, go unnoticed. It seems natural, or it is not even known, that municipal authorities generally approve real estate developments in which apartments have 2 x 2 meters or smaller rooms, with no windows or ventilation, termed "deposit" in the official blueprint, though everyone knows that they will serve as bedroom for "domestic servants".6 6 . "Já faz parte da família", by Luaura Calvi Anic, Trip, 158. Available at: < http://revistatrip.uol.com.br/158/empregadas/home.htm>. It seems natural, or it is not even questioned, that these domestic servants are often asked to "sleep in", separated from their babies to take care of the babies of rich families. Would this be a current expression of "domestic slaves", a symbol of the social rise of the middle class in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in the nineteenth century?

In 2001,7 7 . Veja magazine, São Paulo, issue 1684, year 34, No. 3, 24 Jan. 2001. the cover of the country's largest weekly magazine read: "The siege of the periphery", a suggestive interpretation of the city of São Paulo by the bias of institutionalization of the inequalities of individual rights. In it, a photomontage showed in the center icons such as the Copan and Italy buildings, mansions amid trees and a park in a colorful island surrounded by a mass of gray and ugly periphery shacks. The legend was emphatic: "Middle class neighborhoods are being squeezed by a belt of poverty and crime that grows six times more than the central region of the Brazilian metropolises." The threat to the "city", meaning the city of the elites, is clear. It comes from the poor who, according to the logic of the text, overgrow and are also criminals. The elites consolidate intolerance, deepen the ideology of segregation and reverse the diagnosis: it is not the wealthy minority that is out of place in a scenario of widespread poverty. It is poverty that disfigures and threatens the modern city.

If the intolerance of poverty can be measured in explicit statements like this, it also reveals itself in concrete actions. In the downtown area of the city, where hundreds of buildings are kept vacant by their owners waiting for some appreciation, 8 8 . In Brazil, there as many as six million vacant housing units, mostly in the downtown areas of our cities, a number comparable to the country's housing deficit, which is around 5.8 million homes. (IBGE, 2010; João Pinheiro Foundation, 2008). the conduct towards the poor, or towards movements struggling for housing, is worthy of the apartheid Brazilian style. If a building that has been vacant for years is occupied, repossession is almost immediate and often accompanied by violence.9 9 . See documentary "Dia de Festa" by Toni Venturi and Pablo Georgieff, Olhar Imaginário, Belgium / France, 2006. In this case, justice is not slow, even where a vacant building, under the Statute of the City, fails to fulfill its social function. But in Brazil the right to property overrules the right to housing, which makes sense in the patrimonialist state. Very few people were outraged, also, when nails were put on park benches to prevent the homeless from sleeping on them, or when "antibeggar ramps" were built under viaducts.10 10 . See, among others, Folha de S.Paulo newspaper, 23 Sept. 2005: "Serra põe rampa antimendigo na Paulista," by Afra Balazina. In its "denunciation report,"11 11 . Centro Vivo Forum. " Dossiêdenúncia violações dos direitos humanos no centro de São Paulo: propostas e reivindicações para políticas públicas." Available at: < http://www.dossie.centrovivo.org/Main/HomePage>. the Centro Vivo (Live Center) Forum, which brings together popular movements from the region, denounces all kinds of public authority abuses against the homeless, slum and settlement dwellers: criminalization of the poor, persecution of popular leaders, violent evictions, jets of cold water during the night, pepper sprays. Actions aimed at the systematic removal of all traces of poverty, which greatly resemble a state of exception.

This state of exception, in a full democratic state may, however, exist when it comes to the segregated city. In February 2009, the Military Police of São Paulo responded to a residents' protest by taking over the Paraisópolis slum, nestled in the "noble" neighborhood of Morumbi. The cause of the protest was poorly explained: a police chase of a stolen car in the alleys of the slum resulted in shooting and in the driver's death. That spearheaded a protest by the community. The police occupation that followed turned the slum into a zone of exception: search in shacks without a warrant, body searching of young people on the streets, accusations of violence and coercion in interrogations. According to the Estado de São Paulo newspaper, "in over a little less than three months of operation, between February 4 and April 26, 400 police officers in 100 police cars and a helicopter, with 20 horses and 4 dogs, searched 51,994 local residents".12 12 . O Estado de S. Paulo newspaper, 31 May 2009: "82 dias de medo em Paraisópolis", by Bruno Paes Manso. See also "Infernópolis", Caros Amigos, year XIII, No. 145, April 2009.

If the State fulfills its role by promoting the intolerance of poverty, it does so because there are those who legitimize it, something the dominant classes express whenever possible. At public hearings to review the Master Plan of São Paulo, in 2006, middleclass residents of the traditional Mooca neighborhood openly requested the removal of the Special Areas of Social Interest13 13 . The Special Zones of Social Interest (Zeis) is an instrument provided for in the Statute of the City and regulated in the Municipal Master Plan. With some variations and specificities, they provide for the mandatory allocation of Social Housing in new buildings located in previously delimited precarious settlements. from the area, fearing the "depreciation" they would entail by attracting "poor people". The developers of a giant gated community near the Cidade Jardim bridge, which combines luxury apartments with an exclusive shopping center, uncomfortable with the view to a slum decided to "encourage" the unwanted neighbors to move out by paying them R$40,000 per family. Immediately opposite the gated community, across the river, laid the city hall that was in charge of the "cleanup" action by offering the popular "eviction check": R$1,500 to move out, and R$5,000 if the families were "kind enough" to return to their sates of origem.14 14 . "Kassab quer remover 19 favelas da marginal ": Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, 8 Sep. 2007. In the Jurubatuba slum, in turn, the solution found by the developers of a luxury building was to post a "megabillboard" hiding the slum, and use the State to encourage the residents to move out in exchange for R$1.500.15 15 . "Gafisa usa subprefeitura para retirar favela da vizinhança", by Marcelo Soares, Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, 20 Dec. 2007.

In January 2011, the residents of nine highstandard buildings, outraged by a municipal project for the construction of a social housing complex in the neighboring Parque Real slum, filed a lawsuit with the Prosecutor's Office16 16 . Portal G1, Globo.com 7 Feb. 2011. "Moradores contestam projeto de urbanização de favela em SP" Available at: < http://g1.globo.com/saopaulo/noticia/2011/02/moradorescontestamprojetodeurbanizacaodefavelaemsp.html>. asking for the interruption of the construction works. They complained about the lack of an environmental impact study and possible disturbances, besides the fact that in order to accommodate all the slum dwellers the city had purchased two vacant lots in the area for R$7.5 million. According to the spokesperson of the residents of the luxury buildings, they should have been informed of this purchase and of the destination of the land. They had gotten the information about the works from one of his household employees who lived in the slum.

When the state eventually abandons the logic of patrimonialism, it is reprimanded. Residents of gated communities argue with outrage and apparent wisdom about road and environmental impacts, which are issues under the responsibility of the government. The discourse conceals a certain bias: the concern about the impacts was not expressed when the nine towers in which they live were built. They resent the fact that the city purchased, without consulting them and under laws, a plot of land to expand the housing complex, since they seem to believe that free enterprise applies only to them. They ensure themselves the right to give their opinion about who can or cannot have the privilege of being their neighbor. It seems normal to them that their employees live in a slum right next to them. Certain of the good they are doing by offering them a job, it bothers them that, besides having a job, they could finally have a decent life.

* * *

Despite the glaring indications of a state order that fuels the intolerance of poverty one cannot, because of that, believe that there are ways to reverse this urban tragedy. Our social structure, while in many aspects imbibed with the legacies of the past, has experienced significant changes. It is not that dichotomized between dominant and dominated, and that which we term "dominant classes" is not such a monolithic group.

Since democratization and the new role assigned to the municipalities by the Constitution of 1988 in the conduct of urban policy and since the rise, including in São Paulo in 1989, of governments committed to meeting popular demands, the movement of the socalled "urban reform" has made considerable advances. Resulting from the mobilization of civil society sectors towards more just cities, it at least has succeeded in including this issue on the political agenda. Despite some setbacks on several occasions and its current stagnation, São Paulo was a pioneer at different times, in experimenting with participatory housing policies, or in trying to include in its Master Plan the socalled urban instruments of the Statute of the City.

These experiences were not isolated and occurred within the scope of changes at all levels of government. The creation of the Ministry of Cities in 2002 and the actions resulting thereof, such as the establishment of the Council of Cities (with the participation of popular movements), the creation of the National Fund for Social Housing and the structuring of a funding policy involving municipalities and States meant significant progress in the struggle for urban reform. Regarding the slums, the idea of total eradication and systematic eviction is gradually giving way to urbanization policies.

Efforts for broader land regularization have been made, and health and education facilities have been established in larger numbers, for example in São Paulo, in poor outlying areas. Thus, the Statute of the City approved in 2001, whose instruments should enable the municipalities to purchase underutilized urban land for social purposes, could be seen as a way to reverse urban injustice in Brazil.

It is true, however, that so far it has been virtually ineffective. The Brazilian urban imbalance remains unchanged, and São Paulo is an example of that. The disasters that plague the city during the rainy season and generally affect the poorest are concrete proof of the neglect of informal urbanization in the peripheries, which continue to grow well above the average. Much celebrated urban interventions such as the Urban Operations forecast a significant population growth, but focused exclusively on highstandard demands, to the detriment of the nearly four million people without adequate housing in São Paulo. The construction of new roads along the Tietê River meant the immediate removal of settlements that hindered civil works, such as the Sapo Slum. Although the Statute of the City has been in force for ten years, an instrument like the Progressive Property Tax, which would enable avoiding vacant lots in downtown areas, has not even been regulated. Therefore, there is no reason for celebration. Despite the struggles of popular movements and other organized groups of civil society, the achievements do not seem sufficient to generate the profound transformations needed to change the state order that generates urban inequality and the city of intolerance.

Obviously, one of the reasons for this deadlock lies in the difficulty to transform the State itself and, on a larger scale, the public policy system and the practices that legitimize it. A machine honed over centuries to hinder any attempt to change the logic of production of the urban space does not make easier, of course, the lives of those who participate in negotiation processes with truly "public" intentions. They have to face a management apparatus marked by centralizing procedures, fragmented by internal disputes, shaken by personal political projects, corruption and clientelism, far from the population and its demands, and ineffective if not actively opposed to promote more effective social changes. Add to that the emergency demands, the alleged financial constraints (unjustifiable in the largest city of the tenth world economy), the constraints of "governance" and the reiterated reelection of administrations identified with the lagging clientelist sectors of our elites.

For these reasons, it seems a naive optimism to believe that today, in Brazil, urban instruments imported from the Welfare State will be able to change the state order that, although subtly, increasingly solidifies the dynamics of the intolerance of poverty, builds a city of walls and fuels urban apartheid. The question is, in essence, political. And the desired changes experience a profound individual transformation that can lead each resident of São Paulo to accept that saving the city requires a radical inversion of the logic of its functioning.

The most common feature of social mobilizations to improve a city that collapses before our eyes is each group proposing and advocating solutions concerning themselves: those who are lucky enough to live in a quiet street propose turning it into a deadend street; residents of upscale neighborhoods want to close down avenues on Sundays for leisure; young people in the periphery struggle to emancipate the hiphop culture, and so on. These are all just and necessary claims. However, they will not change the city because they do not understand it as a collective expression, i.e., an expression of all.

The possibility of change involves altering the balance of forces governing the priorities of structural public policies: confronting the land issue and those who retain it for speculative purposes; radically inverting investments to meet urgently and massively the needs of the peripheries; providing housing for all; building an integrated public transport system, even if that immediately affects the users of private cars; inspecting the uncontrolled occupation and transfiguration of neighborhoods through high standard civil construction.

All this would only be possible if there was a change in individual behavior that could contaminate, so to speak, society at large. This entails interrupting or combating (for those who do not adopt them) the attitudes that even covertly reproduce the deeply rooted culture of intolerance. It happens that the culture of building a society that would break with the structures of backwardness is still far from being the majority. And paradoxically, what is celebrated today as an ideal of progress and modernity the rise to "developed" mass consumption levels is precisely the least sustainable and most exclusionary urban pattern. The euphoria of our growth is also the inexorable path towards an even greater urban tragedy. We need to urgently question and rethink the model of city and society we want.

Notes

References

Received on 10 March 2011 and accepted on 16 March 2011.

João Sette Whitaker Ferreira is an architect, an economist and a professor at the School of Architecture and Urbanism, University of São Paulo and Mackenzie Presbyterian University @ whitaker@usp.br

- DEÁK, C. O mercado e o Estado na organização espacial da produção capitalista. Espaço & Debates, São Paulo, v.28, p.18-31, 1989.

- FAORO, R. Os donos do poder: formação do patronato político brasileiro. 3.ed. rev. São Paulo: Globo, 2001.

- FERREIRA, J. S. W. O mito da cidade-global: o papel da ideologia na construção do espaço urbano. São Paulo: Vozes, 2007.

- GUIMARÃES, A. S. A. Racismo e antirracismo no Brasil São Paulo: Fusp, Editora 34, 1999.

- MARICATO, E. Metrópole na periferia do capitalismo. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1996. (Série Estudos Urbanos).

- _______. Habitação e cidade. São Paulo: Atual, 1997.

- _______. Brasil, cidades: alternativas para a crise urbana. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2001.

- MUNANGA, K. Nosso racismo é um crime perfeito. Entrevista a Camila Souza Ramos e Glauco Faria. Revista Fórum, São Paulo, ano 8, n.77, ago. 2008.

- OLIVEIRA, F. de. Acumulação monopolista, estado e urbanização: a nova qualidade do conflito de classes. In: Contradições urbanas e movimentos sociais São Paulo: Cedec, Paz e Terra, 1977. p.65-76.

- _______. Crítica à razão dualista e O Ornitorrinco São Paulo: Boitempo, 2003.

- RIOS, E.; RIANI, J. Desigualdades raciais nas condições habitacionais da população urbana Texto para Discussão n.35, Escola de Governo da Fundação João Pinheiro, Belo Horizonte, 2007.

- SCHWARZ, R. Ao vencedor as batatas 5.ed. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2000.

- VILLAÇA, F. Espaço intra-urbano no Brasil São Paulo: Nobel, 2001.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

30 May 2011 -

Date of issue

Apr 2011