Abstracts

This study's objective was to evaluate the overall well-being and level of distress among caregivers of cancer patients and identify the difficulties faced by physicians who provide care to these patients in order to support the proposition of a new care protocol for a palliative care outpatient service. In the first phase, indicators of the overall well-being and distress levels of ten caregivers of patients undergoing palliative care were assessed using the General Comfort Questionnaire and the Impact of Event Scale Revised. In the second phase, physicians were interviewed to provide their opinions concerning palliative care and the difficulties they face to refer patients to a palliative care service. Spearman's negative correlation, performed to campare the results of both instruments applied to caregivers, suggests that higher levels of distress are associated with lower overall levels of well-being. There is, from the perspective of physicians, a need to integrate the care providade by both curative and palliative outpatient services to facilitate integrating the teams and enabling the maintenance of bonds among patients, families and professionals.

palliative care; cancer in children; suffering

Este estudo teve por objetivo avaliar o bem-estar global e o distress behavior de cuidadores de pacientes com câncer em cuidados paliativos e também avaliar as dificuldades de médicos que lidam com estes pacientes, a fim de subsidiar a proposição de um protocolo de atendimento a um ambulatório de cuidados paliativos. Na primeira fase, indicadores de bem-estar e de distress behavior de dez cuidadores de pacientes em cuidados paliativos foram avaliados pelos instrumentos General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) e Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R), respectivamente. Na segunda fase, médicos foram entrevistados sobre a percepção de cuidados paliativos e dificuldades de encaminhamento ao ambulatório. A correlação de Spearman negativa, entre os resultados dos dois instrumentos aplicados aos cuidadores, indica que maiores níveis de distress associam-se a menores escores de bem-estar global. Na perspectiva dos médicos, há demanda por maior integração entre os ambulatórios curativo e paliativo, o que aumentaria a fluidez entre as equipes e a manutenção de vínculos entre pacientes, famílias e profissionais.

cuidados paliativos; câncer em crianças; sofrimento

La finalidad de este estudio fue evaluar el bienestar global y el distress behavior de cuidadores de pacientes con cáncer en cuidados paliativos, así como las dificultades de médicos que tratan con estos pacientes, con vistas a la propuesta de un protocolo de atención a un ambulatorio de cuidados paliativos. En la primera fase, diversos indicadores de bienestar y de distress behavior de diez cuidadores de pacientes en cuidados paliativos fueron evaluados con los instrumentos General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) e Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R), respectivamente. En la segunda fase, los médicos fueron entrevistados sobre su percepción de los cuidados paliativos y sobre las dificultades para acudir al ambulatorio. La correlación de Spearman negativa entre los resultados de los dos instrumentos aplicados a los cuidadores indica que a mayores niveles de distress se asocian menores grados de bienestar global. Con los médicos se verificó la demanda por mayor integración entre los ambulatorios curativo y paliativo, lo que aumentaría la fluidez entre los equipos y el mantenimiento de los vínculos entre pacientes, familias y profesionales.

cuidados paliativos; cáncer en niños; sufrimiento

ARTICLE

Discussion of protocol for cancer patients' caregivers in palliative care1 Corresponding address: Lara Mundim Moreira EQN 412/413, Edifício Real Park, Bloco A, Sala 11 CEP 70.867-405. Brasília-DF, Brazil E-mail: larammoreira@gmail.com

Discusión de protocolo para los cuidadores de pacientes con cáncer en cuidados paliativos

Lara Mundim Moreira; Roberta Albuquerque Ferreira; Áderson Luiz Costa Junior

Universidade de Brasília, Brasília-DF, Brazil

Correspondence to Corresponding address: Lara Mundim Moreira EQN 412/413, Edifício Real Park, Bloco A, Sala 11 CEP 70.867-405. Brasília-DF, Brazil E-mail: larammoreira@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The present study evaluated global well-being and distress behavior among caregivers and the difficulties faced by physicians, as subsidy to the proposition of a new service protocol for an ambulatory of palliative care. In the first phase, the global well-being and distress behavior indicators of ten patients' caregivers were evaluated using the General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) and the Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R), respectively. In the second phase, physicians were interviewed about their opinions concerning palliative care and the difficulties of referring patients to the ambulatory. The negative Spearman correlation between the results of both instruments applied to caregivers, suggests that higher levels of distress are associated with lower global well-being scores. By physicians the demand for greater integration between curative and palliative ambulatories was verified, what would increase fluidity amongst the teams and the maintenance of bonds between patients, families and professionals.

Keywords: palliative care, cancer in children, suffering

RESUMEN

La finalidad de este estudio fue evaluar el bienestar global y el distress behavior de cuidadores de pacientes con cáncer en cuidados paliativos, así como las dificultades de médicos que tratan con estos pacientes, con vistas a la propuesta de un protocolo de atención a un ambulatorio de cuidados paliativos. En la primera fase, diversos indicadores de bienestar y de distress behavior de diez cuidadores de pacientes en cuidados paliativos fueron evaluados con los instrumentos General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) e Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R), respectivamente. En la segunda fase, los médicos fueron entrevistados sobre su percepción de los cuidados paliativos y sobre las dificultades para acudir al ambulatorio. La correlación de Spearman negativa entre los resultados de los dos instrumentos aplicados a los cuidadores indica que a mayores niveles de distress se asocian menores grados de bienestar global. Con los médicos se verificó la demanda por mayor integración entre los ambulatorios curativo y paliativo, lo que aumentaría la fluidez entre los equipos y el mantenimiento de los vínculos entre pacientes, familias y profesionales.

Palabras clave: cuidados paliativos, cáncer en niños, sufrimiento

Every year, statistics indicate that more than 160 hundred children are diagnosed with cancer around the world and 80% of these patients live in developing countries (O câncer infantil, 2009). Despite the increased success of cancer treatments continually observed in recent years, childhood cancer, as noted by Camargo and Kurashima (2007), has the greatest impact among causes of death among children and adolescents. Therefore, the structuring of efficient health services based on the principles of integral and palliative care is a priority in care provided to 20% to 25% of cancer patients who no longer have a possibility of recovery.

Palliative care directed to children and adolescents is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2010), as a modality of care that involves the supply of multiple forms of support to the physical body, spirit, and mind of patients and families. Ideally, palliative care is provided from the time the diagnosis of a life-threating disease is disclosed and adapted to the biopsychosocial needs of patients and families throughout the treatment. The WHO states that palliative care should necessarily involve a multidisciplinary support system, in which death is conceived as a natural point in the course of life, to assist the family experiencing anticipatory mourning.

Caregivers of Patients with Cancer with no Therapeutic Possibilities of Cure

Currently, due to the increased efficiency of medical treatment, individuals and groups of people with chronic pathologies, such as neoplasia, survive for increasingly longer periods of time. For this reason, the role of a caregiver becomes a functional element increasingly more relevant in the continuity of integral care to patients (Araújo, Araújo, Souto, & Oliveira, 2009). Nonetheless, the attention of health workers is often focused on the patient, the individual undergoing treatment, while few Brazilian studies seek to identify the psychosocial problems and needs of caregivers of patients with cancer (Rezende, Derchain, Botega, & Vial, 2005). Studies using standardized instruments to assess psychosocial measures among the caregivers of children and adolescents with cancer are even more rare.

The act of caring for a cancer patient with no possibility of recovery is a complex and distressing task. Studies indicate that caregivers often experience physical, emotional and social changes, which tend to worsen the closer the patient comes to death, justifying the need to continually measure such changes (Rezende et al., 2005; Slovacek, Slovackova, Slanska, Hrstka, & Priester, 2010).

Considering that one of the objectives of palliative care is to improve the quality of life of both patients and family members, the early identification and assessment of distressing behavior among patients and caregivers-behavior indicating physical and psychosocial suffering-should be a priority in this context. Nonetheless, few studies assess this subject (Costa Junior, 2005; Kohlsdorf & Costa Junior, 2008).

The term "distress" may include a broad range of emotions, from sorrow to more complex psychological syndromes such as depression and anxiety, involving events with a strong psychological load, which should be addressed by health workers in the same way the patient's disease is (Thekkumpurath, Venkateswaran, Kumar, & Bennett, 2008). High levels of emotional distress were observed by Yennurajalingam et al. (2008), not only among cancer patients but also among family members, caregivers and health workers.

Wulff, Thygesen, Søndengaard and Vedsted (2008) also report the suffering of cancer patients and their caregivers due to the poor physical, psychological and social conditions to which they are exposed. Beck and Lopes (2007) also note that the quality of life of the caregivers of pediatric cancer patients is strongly compromised and emphasize the need to provide psychosocial care to improve their ability to provide care. The relationship between the caregiver and patient is highlighted by Alonso Babarro (2006), who argues that this relationship reaches proportions that exceed the act of caring for the cancer patient, while the emotional and well-being levels of both are deeply related to each other.

Palliative Care: The Perception of Physicians and the Structuring of Services

The education of medical professionals tends to privilege a view that a cure is the final objective to be achieved. Such a view may generate a difficulty among physicians in dealing with cases in which a cure is no longer possible. The occurrence of death can lead professionals to perceive their work as frustrating, demotivating and deprived of meaning (Kovács, 2003).

The perception of physicians that death is something that has to be counteracted at any cost may impede them from referring patients to the staff responsible for providing palliative care at the appropriate time. The professional may continue implementing therapeutic strategies aiming to achieve a cure and refer patients to palliative care only when they are too close to death. This type of posture is detrimental to the quality of life of patients and family members, who do not receive the required integral care in a timely manner (Johnston et al., 2008).

In relation to the position of the health staff during care provided to the patient and family under palliative care, Brueckner, Schumacher and Schneider (2009) stress that a long duration of treatment and relationship with a patient, from the time the diagnosis is disclosed, can positively affect care because it enables knowledge to be acquired by the health staff concerning the life of the patient and allows the dynamics of the family to be well explored, facilitating the patient-professional relationship and the transmission of information. Costa Filho, Costa, Gutierrez and Mesquita (2008) also note the need to integrate services provided by ICUs, hospitalization, outpatient and emergency services in order to establish efficient communication to facilitate the exchange of information, referrals, diagnoses and, consequently, the efficiency of care delivery.

Brueckner et al. (2009) note that the greatest difficulties impeding the improvement of palliative care are related to a lack of resources, time, and efficient communication among patients, staff and family members; all the pillars of this triad are functionally interrelated. Communication with patients would be better established if there was more time and opportunity to enable it. This aspect of care is hindered due to the excessive workload born by workers, the numbers of which are insufficient. Behmann, Lückmann and Schneider (2009) stress that palliative care should have a greater investment in the training of staff and giving opportunities within their work routine to perform such care.

The Palliative Care Outpatient Service of the Pediatric Oncology and Hematology Center

The Palliative Care Outpatient Service at the Pediatric Oncology and Hematology Center from the State Health Department in the Federal District, Brazil was created out of a partnership with a project of a philanthropic institution in the Federal District. This service's objective is to provide, until the time of death, psychological and social care to the family and patient who no longer have any possibility of recovery.

The service's staff is composed of professionals from the fields of Medicine, Nursing, Social Work, Psychology, Nutrition and Physical Therapy. Care is provided according to the following protocol:

After the diagnosis with no possibility of recovery is disclosed, the oncologist is in charge of clarifying the situation to the patient's family and referring the patient to palliative care. Before the first consultation with the service, a summary of the case is presented to the staff to identify potential clinical and/or social needs, and technical difficulties faced by the patient and family.

The staff members are introduced to the patient at the time of the first consultation and the patient receives information regarding how the service works and the objectives of providing such care to families and patients. At this time, each professional makes an assessment, within his/her specialty, concerning the needs of patients and family members. Procedures are then established to alleviate the patient's symptoms and suffering, as well as to determine the regularity of visits based on the intensity and frequency of the patient's complaints. After each consultation, a date is scheduled for the staff from the philanthropic institution to visit the family. During this visit, the social worker identifies potential material needs that may be met with the resources provided by the institution and the psychologist outlines the family's psychological profile, taking into account social and behavioral aspects. The staff also verifies whether the scheduled consultations are being attended to or whether there is some difficulty on the part of patients attending consultations. Before subsequent consultations take place, the philanthropic staff makes a report of the home visit to inform the entire team about the needs identified. In the case of death, an oncologist from the Pediatric Oncology and Hematology Center assists the family; the team from the philanthropic institution provides support for the burial, bearing the costs when necessary. Two weeks after death, the staff makes a condolence visit to the family to monitor and assess the family's psychosocial conditions.

Based on direct observation and the description of the functioning of the Palliative Care Outpatient Service, as well as the application of instruments to measure the overall well being of caregivers and their levels of distress, this study aimed to evaluate the overall well being and distress of caregivers of patients with cancer undergoing palliative care and also evaluate the difficulties faced by physicians when dealing with these patients in order to support the proposition of a new service protocol.

Method

Participants

A total of 10 caregivers participated in the first phase of the study (seven mothers, one father, one grandmother, and one sister) of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer and without the possibility of a cure, cared for by the Palliative Care Outpatient Service at the Pediatric Oncology and Hematology Center, State Health Department, Federal District, Brazil.

Seven physicians participated in the study's second phase (five women and two men). These participants were members of the Pediatric Oncology Hematology Center and all had background and graduate studies in pediatric oncology and/or hematology and at least four consecutive years of experience in the field.

Instruments

The following instruments were used in this study:

General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ): the instrument's Portuguese version by Rezende et al. (2005) was used. This is a multidimensional questionnaire composed of 49 statements in the first person classified on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from "totally disagree" to "totally agree" (Cronbach's alpha = 0.83). The instrument was especially developed to evaluate the overall state of caregivers of patients with cancer in the final phase of the disease, comprising dimensions such as social support, conflict resolution, spiritual beliefs and expectations, as well as subjective, negative, and positive aspects concerning the care process. Factors related to the caregiver such as encouragement, the need to rest, socialization and nutrition are also evaluated. The total score is computed based on the sum of points obtained for each item, which ranges from 49 to 294. Half of the items have their values inverted because they negatively contribute to the caregiver's well being. Hence, the greater the score, the greater the well being.

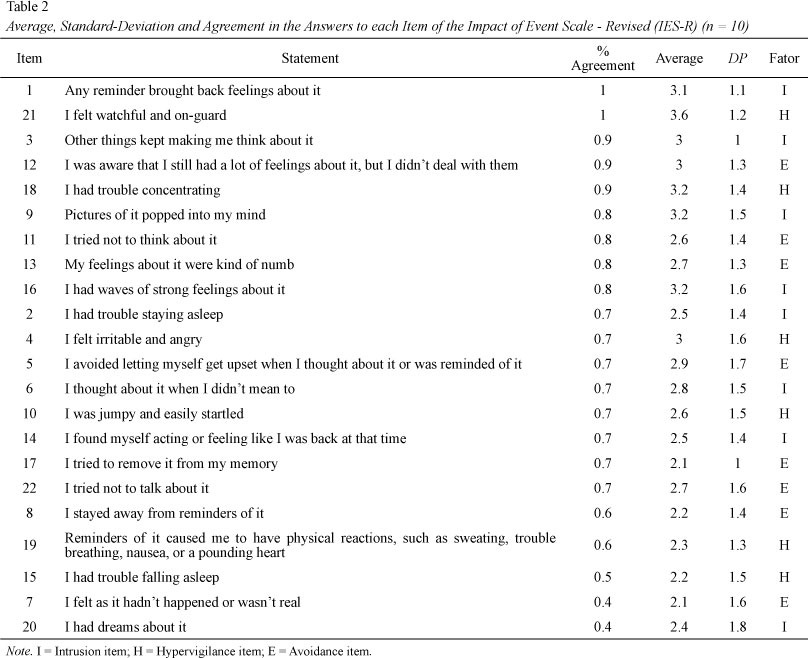

Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R): the instrument's Portuguese version by Pereira and Figueiredo (2005) was used. This scale is composed of 22 statements addressing the subjective impact of specific events on individuals, enabling the comparison of different levels of distress after a specific event in life. Each statement presents five answer options ("never", "a little", "moderately", "very", and "very much") with points, from 1 to 5. The IES-R is divided into three sub-scales: Avoidance (items 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 17 and 22), Intrusion (items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 14, 16 and 20), Hypervigilance (items 4, 10, 15, 18, 19 and 21). The score of each subscale is computed by the average values attributed to their respective items and the total score represents the sum of the averages obtained on each subscale. The greater the scores obtained on the subscale or total score, the greater the severity of symptomatology related to distress. The lower the score, the less is the distress experienced by the individual. The instrument was applied to measure the level of distress in relation to communication concerning the referral of a patient for palliative care.

Script of Semi-structured interview: was developed to assess the perception of physicians concerning palliative care and difficulties in referring patients for palliative care. It addressed the respondent's academic education and professional background, difficulties in reporting adverse outcomes, concept of palliative care and technical knowledge in the field, how communication with the patient concerning the transition from curative treatment to palliative treatment occurs, and availability of time to discuss the case with the staff. The interview had a sequence of questions related to how they face situations specific to the pediatric oncological context, such as (a) pain control, (b) control of other unpleasant physical or somatic symptoms, (c) physical and psychosocial suffering of patient and family members, (d) patients or companions who manifest fear of death, and (e) their own emotions related to death and the process of dying. The questions were answered on a scale of frequency that indicated the extent problems with these situations were perceived: "never", "occasionally", "frequently" or "always".

Procedure

Data collection. In the first phase, the overall well being and distress of ten caregivers of children and adolescents with cancer were assessed using the General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) and Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R). The design provided for the application of the instruments at three different points in time: up to one week after the patient was referred to the outpatient service and after two and four months post-treatment. However, reapplication of the instruments was not possible due to the late referral of patients to the service, thus, only the first assessment was performed. This kind of difficulty led to the development of the second phase to identify, through interviews, the perceptions physicians held of palliative care and the difficulties they face referring patients to these services. The first phase was performed with the caregivers after their first consultation in the outpatient service (A = 14 days; SD = 18.88). To avoid potential problems due to illiteracy or low educational level, the instruments were read out loud to the respondents for all the applications. In the second phase, the interviews were transcribed verbatim and their contents were analyzed, searching for relevant information that could be related to difficulties in referring patients, as observed in the study's first phase. We also identified complaints and potential changes in the operational system of referral and follow-up for children and adolescents by the service's staff.

Data analysis. Descriptive analysis (average and standard deviation) of the results obtained in the first phase was performed. Additionally, raw scores obtained by the participants for the instruments were transformed into z scores and Spearman's non-parametric correlation tests were performed due to the reduced number of participants. The interviews held in the second stage were audio recorded and submitted to content analysis.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Research Committee at the State Health Department, Federal District, Brazil (Protocol No. 128/2009).

In the study's first phase, after the team was formally introduced during the first consultation and patients received clarification of the study's objectives, the participants were asked to sign free and informed consent forms. Only after receiving their consent were the instruments (GCQ and IES-R) applied.

In the second stage, the physicians received clarification concerning the study's objectives and were asked to sign informed consent forms, along with an authorization for the audio recording.

Results

Data obtained on the Impact of Event Scale - Revised indicated a significant dispersion of total scores, which ranged from 4.04 to 12.42 (A = 8.19 and SD = 2.50). This finding indicates that the way caregivers deal with referral to outpatient service (distress behavior) is not uniform. Such a variation is confirmed by the fact that the highest score (12.42) is three times greater than the lowest score (4.04). Additionally, six participants (2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 10) present scores below half (9.0) the maximum score (15.0) attributed to the test, as shown in Table 1.

Items 1 and 21 ("Any reminder brought back feelings about it" and "I felt watchful and on-guard") presented 100% agreement. Agreement was obtained when respondents chose options other than "never". On the other hand, items 4 and 20 (I felt irritable and angry" and "I had dreams about it", respectively) presented only 40% agreement. There is no explicit relation among the data, since neither of the items with the highest percentage of agreement and the ones with lowest percentage of agreement do not belong to the same factor of the scale.

The highest averages were found for items 21, 18 and 19 (3.6; 3.2 and 3.2, respectively). The lowest averages, in turn, were observed for items 7 and 17 (2.1). Also in this case, we do not observe a relationship between the items' percentage of agreement and average, since even when absolute agreement was obtained on the item, the variation in the scale from one to five caused the average to vary independently of the level of agreement. Table 2 presents the frequency, average, standard deviation and agreement for each item of the IES-R.

The total average of all the participants in the subscale Avoidance was 2.54 (SD = 0.83), Intrusion was 2.84 (SD = 0.98), and Hypervigilance was 2.82 (SD = 1.06), while no significant correlation was found among them. Table 3 presents the averages of each participant for the IES-R subscales.

The scores obtained on the General Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) also presented great dispersion, ranging from 144 to 252 (A = 189.3 and SD = 36.17). The total scores were not very low, that is, they were too close to the minimum (49); only three participants were located on the scale's lower half, the most distant from the maximum value (249). This finding indicates a low prevalence of very low scores of overall well being, as seen in Table 1.

Item 23 - "I like his/her room to be calm" (A = 5.8 and SD = 0.4) and item 49 - "God is helping me" (A = 6.0 and SD = 0) from the GCQ presented the highest averages among the items that did not have their values inverted in the scale analysis, that is, among the items that positively contribute to the caregiver's overall wellbeing. In turn, items 4 - "I am concerned about my family" (A = 6 and SD = 0); 34 - "I'm constantly thinking about his/her discomfort"; and 46 - "I think a lot about the future" (A = 5.8 and SD = 0.4), presented the highest averages among the items that presented inverted values (those that negatively contribute to the caregiver's overall wellbeing).

The highest standard scores (z) obtained on the IES-R were 1.70, 0.82 and 0.74 by participants 8, 3 and 1, respectively. The lowest were 0.80 (participant 9), -0.22 (participant 2) and -0.24 (participant 6). The highest standard scores (z) obtained on the GCQ were 1.73, 1.26 and 0.96 by participants 5, 2 and 9, respectively, and the lowest were -1.25 (participant 1), -1.05 (participant 8) and -0.70 (participant 3), as shown in Table 4.

Data concerning participant 9 were not considered in Spearman's correlation analysis because the IES-R was not properly applied in this case: the instrument measured the level of distress related to the diagnosis of the disease and not the referral of patient to palliative care. The analysis presented a Spearman's correlation of -0.433 (p = N.S.) among the total scores obtained for each of the participants in the two instruments. Even though this correlation was not statistically significant, it is important, because such a result may be related to the low number of participants.

Interviews with the Physicians

The analysis of the interviews revealed there is great discomfort on the part of the medical staff in referring patients for palliative care. The reason for such discomfort is that the follow-up of patients is then transferred to another physician and another staff, different from the one monitoring the treatment from the time the diagnosis was first disclosed. Such discomfort is illustrated by the following excerpt "the patient cannot be deprived of the presence of the physicians who have always taken care of him/her" (Physician 7), because it concerns an affective and emotional bond, as well as a bond of trust established with the patient.

This same physician continues "...you change the staff, but what about the past 10 years? What about that patient? I see, see, see, but when the time comes: 'I'll refer you to another clinician to follow-up with you....' Is it fair? I guess we have to reconsider... in my opinion, not for me, for me it is more of a practical issue, but for the patient who will have to reacquire trust at a very difficult time..." (Physician 7).

Such a view was related to the fact that the patient may feel abandoned, which may be detrimental to the treatment. The patient may also find it somewhat strange that there is a need to go to a special consultation on Friday mornings with an exclusive team, different from the team caring for the remaining patients: "why do only I come here, only this, only that...?" (Physician 7).

The respondents also reported a concern over the possibility of the remaining team members becoming distant from the most complicated cases due to the centralization of palliative care in a single outpatient service. This estrangement was described as a very serious aspect in the new dynamics of care: "... we may lose the ability to deal with more severe patients" (Physician 3).

The professionals also reported that communicating bad news is a difficult task associated with the fact that they often establish a bond with patients and families. But even when they take a strictly professional role, there is hope that "the child will get well" (Physician 5), which characterizes a painful process in the face of a patient's worsening condition. Such difficulties were also associated with the simple fact that giving someone "bad news" is, by itself, an unpleasant experience and in that context it is difficult to establish a realistic dialogue and at the same time not take away the hopes of the patient and family.

In regard to omission of information concerning exams' adverse results, the participants showed a significant concern in gradually informing the patients and families, always being honest and sincere, but respecting the time of each family. "Never omit, but perhaps postpone the news. But since we deal with children, we always have to break the news, in one way or another. You can postpone not directly talking right away, telling little by little and then delivering the news we have to, but never omit, we have no right" (Physician 6).

All the professionals reported they talk with the patient about the transition from a curative treatment to a palliative treatment but that it happens gradually. The conversation and referral occur only after the case is discussed with the health staff and "timing varies because most of the time it depends more on the family and its relationship with the patient than on the disease itself." (Physician 2). The feelings reported about this conversation and referral include failure, sorrow, impotence, and frustration. These feelings are justified by the academic education these professionals receive, which is mainly focused on cure. When they acknowledge that there is no possibility to suppress the disease, a feeling of "medical failure emerges, even among those who recognize that palliative care is good" (Physician 2).

All the physicians stated they would not inform the family of the occurrence of some error on the part of the professional staff during the treatment, arguing that "it would not be worth it, I do not want to make the family suffer even more" (Physician 7). For that, they stated that the choice of one treatment to the detriment of another is discussed within the team and verifying whether a given treatment "works or not" is only possible after you try it. "At the time, the team's intention was the best. So there is no point blaming anyone" (Physician 4). Furthermore, they alleged that such information would shake the team's confidence, compromising care provided to other patients.

We verified that the physician's first contact with palliative care occurred in different stages of their professional education, from the period of academic education up to the time they started working professionally in a hospital. Understanding concerning palliative care also varied considerably. Three physicians reported it is a form of multidisciplinary care and six addressed the patient's increased quality of life, reduced suffering, and control of unpleasant symptoms. All the professionals agreed it is a very important type of intervention, as long as qualified professionals implement it with the resources required by this type of care. It is also important to note that more than half of the professionals mentioned the need to introduce palliative care during curative treatment in order to deliver integral care to patients, addressing their biopsychosocial demands. Nonetheless, the respondents also pointed to difficulties concerning the availability of palliative care from the time the diagnosis is disclosed and to the early referral of patients to this type of care due to a lack of human, physical and financial resources.

In regard to the understanding of implications related to the diagnosis of "no therapeutic possibility of cure", references to emotional, psychological and social issues were recurrent, while "the implications depend a lot on each case, but the adverse impact is undeniable" (Physician 2). They reported many times that there is a change in the relationship between parents and children, as well as the fact that caregivers become exhausted. Additionally, there is at the same time, both acknowledgement and fear of the future. The participants also raised the fact that the death of a child involves an unexpected event that interrupts plans and dreams for the future, a situation very difficult to accept.

The difficulties related to care provided to patients included: lack of a physical area to provide consultations and hospitalization (medical offices and beds); the need for more workers within the team, which is already overloaded; the limited academic education of professionals concerning integral care and poor technical knowledge concerning palliative care; difficulty in communicating with the family due to families' low levels of education and poor understanding of information related to their respective diseases and treatments (stressing the need for psychologists and social workers to facilitate the communication process); the difficulty of patients and companions commuting with the hospital; a lack of basic material (probes, medication, equipment); and the outpatient service's operational difficulty in implementing palliative care (it is currently separated from the remaining healthcare staff.)

They also required more time to talk about the cases of patients who no longer had the possibility of attaining a cure; all the physicians reported that it would benefit the efficiency of care. The participants complained that the hospital does not allow the team to spend much time discussing these cases to define a follow-up protocol: "there are few people for a lot of work" (Physician 2).

Knowledge concerning the Palliative Care Outpatient Service, which works in the hospital itself, was extremely limited. The respondents only reported that "it is a multidisciplinary team and all provide consultation at the same time" (Physician 5). They also reported "all the patients receive more comprehensive care, including the needs they have at home" (Physician 6). No physician provided details about the dynamics of care provided at the palliative care outpatient service.

Among the critiques and suggestions provided to the service, the physicians suggested that perhaps the fact that various professionals provide the consultation at the same time in the same office, is aversive to the patient and the family and that it would be better if professionals provided individual care instead: "Does the patient feel comfortable, at this time, to face a team? Perhaps it would be more comfortable for him to expose his pain to a single person" (Physician 1).

There was also a demand for systematic methods to evaluate the service. The participants inquired "what are the quality criteria? What are the indicators showing it is working? So, we can monitor these indicators... In order to propose changes, you know?" (Physician 4).

Discomfort concerning the referral of patients to the outpatient service so that care is exclusively provided by the new staff was related to a proposal of change. The respondents stated that it would be ideal if, for "a greater integration, both standard and palliative consultation would occur together, so that the physicians would not need to stop providing care for the patient...so we would monitor this patient together" (Physician 6).

The answers to questions using a frequency scale were very diversified. Among the difficulties related to "pain control", they reported a lack of resources available to treat this symptom, such as a lack of specialists in pain treatment and non-medication techniques like acupuncture and nerve block (terminology used in the medical field), among others. Additionally, a difficulty measuring pain was reported as an element that hinders the work of physicians on this type of symptom due to the fact it refers to a subjective experience, in which it is difficult to intervene. They also reported that lack of experience and limited contact with these cases might reduce the ability of physicians to administer analgesics and opiates.

Difficulties concerning the control of unpleasant physical symptoms were also associated with the limitations of measurement. From this perspective, they indicated that a long-term relationship with the patient may facilitate the treatment of this type of symptomatology: "I guess it has more to do with you knowing the patient you're dealing with; it is linked to degree of proximity" (Physician 7).

A difficulty in dealing with the physical and psychosocial suffering of patients and family members was associated with the team's affective involvement, as the relationship is no longer strictly professional. They also mentioned family dynamics as a moderator of this type of situation- which can either complicate or facilitate this type of management- and the professional's personal experience itself: "you have children... and then compare that with what you have already seen" (Physician 7).

In regard to the situation of dealing with patients or family members who manifest fear of death, they report that it is not always a problem because the patients and family members themselves do not express it explicitly: "It is very rare for them to expose it. Nobody talks about it. In reality, nobody talks about death. It happens occasionally, not very frequently" (Physician 6).

Finally, the difficulties in dealing with one's own emotions related to death and to the dying process were associated with individual conceptions and spiritual beliefs, which may or may not bring comfort in these situations. The need for the physicians themselves to reflect upon these issues was also mentioned, including the concept of finitude, and applying their personal experiences in their professional lives:

"If we are unable to accept it, as a person, we are unable to help others. We'll say only nonsense, you known? There is no point talking about spiritual experience, that mother may not have it... There is no use talking about spirituality. So, it is something very personal. Each one's experience. For this reason, there isn't a rule, a law. There is no rule, there is no protocol." (Physician 4).

Discussion

The negative correlation verified between the results obtained from the two instruments indicates that higher levels of distress tend to be associated with lower scores of overall well being. Such a finding is also seen in the comparison of z scores, since the highest scores identified obtained on the IES-R (z = 1.70, z = 0.82 and z = 0.74) are related to the lowest score identified on the GCQ for overall well being (z = - 1.05, z = - 0.70 and z = -1.25). Nonetheless, the participants with the lowest levels of distress did not necessarily present higher scores of well being. One explanation for this is that the referral is not a one-time event, when clear and objective information concerning what palliative care means and the new focus of the treatment is provided. For this reason, the referral does not characterize a traumatic or potentially traumatic event. Therefore, the level of stress at the time of the referral is not necessarily functionally related to well being, since the caregivers may not have, at this time, a sufficient understanding of the new approach of treatment provided by a new staff.

A rupture in the correlational pattern is observed due to participant 9, who presented the third highest score on the distress scale, but at the same obtained one of the three highest scores on the well being scale. This phenomenon may be related to the fact that this participant was the only one who completed the IES-R considering the feelings and emotions experienced at the time the diagnosis was disclosed, instead of feelings experienced with the referral to palliative care. (That is why the results concerning this participant were not considered at this point of the analysis.) Therefore, his high score is associated with the high level of distress experienced at the time diagnosis was disclosed, before the referral, which is a possible explanation for the high score obtained on the well being scale as opposed to the very high score obtained on the distress scale.

A concern on the part of the family with the patient's discomfort and uncertain future was identified by the GCQ scale as factors that most negatively affect wellbeing, while a belief in spiritual help and peacefulness observed in the patient's room, were factors that most positively affect wellbeing. Based on these findings, a change may be proposed in the protocol of the outpatient service, which is to focus on communication with the family by providing clear, objective and clarifying information, since uncertainty in relation to the disease prognosis was identified as a factor that negatively affects well being.

Concern with the family and with financial issues were also identified as recurrent factors that compromise well being, reinforcing the importance of the welfare role played by the philanthropic institution and by the hospital's Social Work team. Such information shows that family demands and problems- not necessarily directly related to the disease-also require continuous attention from the team.

Belief in spiritual help, identified as a relevant factor to increasing the well being of caregivers, suggests the need for the service to rethink its dynamics by adding a professional specialized in providing spiritual support to patients and families to the team. This kind of issue is widely indicated in the literature as an essential element in providing palliative care, as noted by Costa Filho et al. (2008).

There is also a great need for a quality and comfortable structure to assist the companions in the hospital, such as "a comfortable chair and bed", which is partially responsible for compromising the caregivers' well being. It is, therefore, extremely important to invest in physical infrastructure and furniture specific for this purpose, both for inpatients and outpatients, an aspect already noted by Behmann et al. (2009).

In regard to late referral, we noticed a strong demand for greater integration between the two outpatient services, the curative and palliative services. Such integration would facilitate the relationship between the two teams and avoid rupturing between patients and professionals. Early referrals, allied with an understanding that palliative care is specific care focused on severe patients, implemented together with curative treatment is, according to the physicians, coherent with WHO recommendations (WHO, 2010). Such an approach was not however, observed in practice due to a lack of human resources and physical structure, which does not allow the palliative care staff to care for a larger number of patients. Issues of this nature hinder the improvement of services (Brueckner et al., 2009). Therefore, few patients are referred to the outpatient service and only when their conditions are already very compromised, characteristic of a late referral, which limits the actions of the team and compromises the quality of care. This situation is the kind that is opposed by the view of Johnston et al. (2008), concerning the importance of referring patients to palliative care services early.

Keeping consultations in the regular service integrated into follow-up in the palliative care service, as proposed by the interviewed physicians, would be a way to deal with this difficulty. It would enable the team responsible for the curative treatment to maintain a relationship with the patient until the end of his/her life and also enable the palliative care staff to become close to the family and patient early on, participating in the treatment for a longer time and creating the possibility of establishing stronger bonds, instead of beginning the palliative care later at a time when the patient's condition is so adverse and time is short, already in the advanced stage of the disease. This measure is in accordance with the proposal put forward by Costa Filho et. al. (2008) to integrate the various sectors in the hospital to provide palliative care, and with the view of Brueckner et al. (2009) that the time a professional spends with the patient positively contributes to care provided at the end of life.

Final Considerations

A demand for more time to discuss cases and the difficulties in dealing with issues related to death and the dying process, the communication of adverse results, and the referral to palliative care itself, refers to the need for the staff to have more time both to dialogue and discuss technical aspects of interventions, as well as to exchange experiences, things that cause anguish and difficulties focusing on the caregiver's care and self-qualification, based on the sharing of experiences.

Even though many suggestions to implement improvements in the Palliative Care Outpatient Service were presented, most are not feasible due to a lack of human and physical resources, which also compromises the hospital's infrastructure. Changes require engaged professionals, which requires training and sensitization to the need to adapt to the identified demands, establishing a more integrated care system.

Further studies to identify more objectively and specifically levels of distress among caregivers of patients referred to palliative care should consider that such a process occurs gradually and in a heterogeneous manner. Different demands concerning information on the part of patients and caregivers, and different communication strategies on the part of health workers implies that a care protocol is required in order to achieve a higher level of standardization; so far, such procedures are not fully standardized.

References

O câncer infantil. (1999). Recuperado de http://br.guiainfantil.com/cancer-infantil.html

Pereira, M., & Figueiredo, A. (2005). Impact of Event Scale - IES: Versão de investigação. Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal.

World Health Organization. (2010). WHO definition of palliative care. Recuperado de http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

Received: Oct. 14th 2010

1st revision: Feb. 28th 2011

Approved: Mar. 17th 2011

Lara Mundim Moreira is an undergraduate student from the Psychology Institute, Universidade de Brasília.

Roberta Albuquerque Ferreira is MSc. Graduate Program in Health and Human Development Processes, Psychology Institute, Universidade de Brasília.

Áderson Luiz Costa Junior is an Associate Professor at the Psychology Institute, Universidade de Brasília.

1 Paper derived from the master's thesis of the second author under guidance of the third author, defended in 2011 at the Graduate Program in Health and Human Development Processes, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Support: National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

- Araújo, L. Z. S., Araújo, C. Z. S., Souto, A. K. B. A., & Oliveira, M. S. (2009). Cuidador principal de paciente oncológico fora de possibilidade de cura, repercussões deste encargo. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 62(1), 32-37. doi:10.1590/S0034-71672009000100005

- Alonso Babarro, A. (2006). Atención a la familia. Atención Primaria, 38(Supl. 2), 14-20.

- Beck, A. R. M., & Lopes, M. H. B. M. (2007). Cuidadores de crianças com câncer: Aspectos da vida afetados pela atividade de cuidador. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 60(6), 670-675. doi:0.1590/S0034-71672007000600010

- Behmann, M., Lückmann, S. L., & Schneider, N. (2009). Palliative care in Germany from a public health perspective: Qualitative expert interviews. BMC Research Notes, 2, 116. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-2-116

- Brueckner, T., Schumacher, M., & Schneider, N. (2009). Palliative care for older people - exploring the views of doctors and nurses from different fields in Germany. BMC Palliative Care, 8, 7. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-8-7

- Camargo, B., & Kurashima, A. Y. (2007). Cuidados paliativos em oncologia pediátrica: O cuidar além do curar. São Paulo: Lemar.

- Costa Filho, R. C., Costa, J. L. F., Gutierrez, F. L. B. R., & Mesquita, A. F. (2008). Como implementar cuidados paliativos de qualidade na unidade de terapia intensiva. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva, 20(1), 88-92. doi:10.1590/S0103-507X2008000100014

- Costa Junior, A. L. (2005). Psicologia da saúde e desenvolvimento humano: O estudo do enfrentamento em crianças com câncer e expostas a procedimentos médicos invasivos. In M. A. Dessen & A. L. Costa Junior (Orgs.), A ciência do desenvolvimento humano: Tendências atuais e perspectivas futuras (pp. 171-189). Porto Alegre: Artmed.

- Johnston, D. L., Nagel, K., Friedman, D. L., Meza, J. L., Hurwitz, C. A., & Friebert, S. (2008). Availability and use of palliative care and end-of-life services for pediatric oncology patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(28), 4646-4650. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1562

- Kohlsdorf, M., & Costa Junior, A. L. (2008). Estratégias de enfrentamento de pais de crianças em tratamento de câncer. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 25(3), 417-429. doi:10.1590/S0103-166X2008000300010

- Kovács, M. J. (2003). Educação para a morte: Desafio na formação de profissionais de saúde e educação São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo.

- Rezende, V. L., Derchain, S. M., Botega, N. J., & Vial, D. L. (2005). Revisão crítica dos instrumentos utilizados para avaliar aspectos emocionais, físicos e sociais do cuidador de pacientes com câncer na fase terminal da doença. Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia, 51(1), 79-87.

- Slovacek, L., Slovackova, B., Slanska, I., Hrstka, Z., & Priester, P. (2010). Incidence and relevance of depression among palliative care female inpatients. European Journal of Cancer Care, 19(5), e8-e9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01030.x

- Thekkumpurath, P., Venkateswaran, C., Kumar, M., & Bennett, M. I. (2008). Screening for psychological distress in palliative care: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 36(5), 520-528. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.010

- Wulff, C. N., Thygesen, M., Søndengaard, J., & Vedsted, P. (2008). Case management used to optimize cancer care pathways: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 227. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-227

- Yennurajalingam, S., Dev, R., Lockey, M., Pace, E., Zhang, T., Palmer, J. L., & Bruera, E. (2008). Characteristics of family conferences in a palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(9), 1208-1211. doi:10.1089/jpm.2008.0150

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

15 Mar 2013 -

Date of issue

Dec 2012

History

-

Received

14 Oct 2010 -

Accepted

17 Mar 2011 -

Reviewed

28 Feb 2011