Abstract

Within the context of the creation of birthing houses around the world and different models of care for childbirth, the author proposes an analysis that contributes to the discussion about the place for birth, especially in urban Brazil.

birthing center; birth; medicalization

Resumo

No contexto de criação de casas de parto em várias partes do mundo e diferentes modelos de cuidado do parto, a autora propõe uma análise que contribui para a discussão sobre o local de nascimento, especialmente no Brasil urbano.

centro de assistência ao parto; parto; medicalização

Birthing houses: one concept, multiple interpretations

“Birthing houses” or “birthing centers” were initially developed in reaction to perceived excesses of the medicalization of childbirth. Medical technologies such as antiseptics, blood transfusions, and antibiotics played a key role in the significant decline in childbirth-related maternal and child mortality in the twentieth century. These technologies were, however, a mixed blessing, since not infrequently their incompetent use put women and children at risk. For example, in early twentieth century America, women assisted by a physician were at a higher risk of dying in childbirth than women assisted by a trained midwife (Loudun, 1992LOUDON, Irvine. Death in childbirth: an international study of maternal care and maternal mortality, 1800-1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1992.). One should remember, nevertheless, that the medicalization and “hospitalization” of childbirth were not just the result of the machinations of greedy and manipulative male physicians, but, to a significant extent, an answer to the demands of pregnant women, who wished to accelerate childbirth, escape pain, and even be able to rest after birth in the protected environment of a hospital (Leavitt, 1986LEAVITT, Judith. Brought to bed: childbearing in America, 1750 to 1950. New York: Oxford University Press. 1986.). The vast majority of health professionals promoted the medicalization of childbirth, but from the 1930s on, some specialists criticized the transformation of childbirth into a physician-controlled procedure, and advocated the return to “natural” birth. These specialists also argued that women who understood the physiology of the birthing process and did not fear it experienced little or no pain during labor (Michaels, 2014MICHAELS, Paula. Lamaze, an international history . New York: Oxford University Press. 2014.). The push to reduce medical intervention in childbirth was accelerated with the rise of the women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s and 1970s. Collective works, such as Our bodies, ourselves , voiced women’s aspiration to free themselves from the oppressive attitudes of paternalistic and misogynistic doctors and take back control of their bodies (Davis, 2007DAVIS, Kathy. The making of our bodies, ourselves: how feminism travels across borders. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2007.). The opening of the first birthing houses was part of this general trend.

The birthing house movement started in the 1970s in California, then spread to other cities and countries. Birthing houses aspire to reproduce, as much as possible, the ideal of home birth through the creation of a home-like environment, with a minimum of medical surveillance and interventions during childbirth, and the encouragement of the presence of family members and friends during delivery. Birthing women are allowed to move freely during labor, and in some birthing houses are able to give birth in water, and can receive alternative treatments to alleviate pain, such as massage and aromatherapy. By contrast, they have no access to epidural anesthesia and normally no access to other pain relief drugs, either. Birthing houses are directed by midwives or obstetric nurses who strongly favor a physiological approach to childbirth. They often believe that a physiological/natural birth is a very important experience for a woman that favors her transformation into a good mother. Midwives involved in the physiological birth movement attempt to develop and consolidate their “ownership” of the supervision of childbirth. They promote the diffusion of their unique professional skills, and reject the techniques controlled by physicians, like epidural anesthesia, episiotomy, medical induction of labor, use of forceps, and C-sections outside emergency situations. Unsurprisingly, birthing houses frequently become sites of power struggles between doctors and midwives.

While all birthing houses are committed to the promotion of natural or physiological birth, this promotion can take very different forms. In the US and Quebec, birthing houses are destined above all for highly motivated, educated, middle-class women who believe they will be empowered by the experience of natural childbirth (Sibbald, Ping, 2010SIBBALD, Kathryn; PING, Elizabeth. Historical development of nurse midwifery and birthing centers in America? Available at: < https://www.academia.edu/365880/Historical_Development_of_Nurse_Midwives_and_Birth_Centers_in_America> . Access on: 24 Oct. 2018. 6 Nov. 2010.

https://www.academia.edu/365880/Historic...

; Arnal, in pressARNAL, Maud. The transformations of medicalization of pain relief in the organization of perinatal care system in Quebec. Social Theory and Health . In press.). In the UK and France, they are part of the national health system and are centrally promoted, among other things, because birth without medical interventions is perceived as less expensive, enabling significant savings for the national health system (Walsh, 2007WALSH, Denis J. A birth centre’s encounters with discourses of childbirth: how resistance led to innovation. Sociology of Health & Illness , v.29, n.2, p.216-232. 2007.; Charrier, 2015CHARRIER, Philippe. Diversification des lieux de naissance en France: le cas des Maisons de Naissance. Recherches familiales , v.12, p.71-83. 2015.).

The implementation of birthing houses directed exclusively by midwives was and is often resisted by gynecologists, who, following a centuries-long tradition of physicians’ effort to subordinate midwives, affirm that the only right place for a demedicalized birthing house/center is inside a maternity clinic; i.e., under doctors’ control. Birthing houses are enthusiastically promoted by a sub-group of midwifes who aspire to full professional autonomy. Other midwives argue, in contrast, that all maternity clinics, not just birthing houses, should be user-friendly, eliminate unnecessary medical interventions, and propose alternative pain relief techniques, which could be combined with medical ones: there is no need to create special structures dedicated to the promotion of demedicalized birth. At the same time, many professionals recognize that small units directed by midwives are less affected by pressures to be cost-efficient and to rationalize the division of labor than big hospitals, and can therefore more easily provide individualized attention to birthing women and ban useless or harmful medical interventions. Women in industrialized countries are also divided on the question of the demedicalization of childbirth. Some enthusiastically support specific structures dedicated to natural birth, while others are critical of a (perceived) reification and glorification of “female nature,” and a (presumed) attempt to cut the costs of childbirth by limiting birthing women’s access to efficient pain relief.

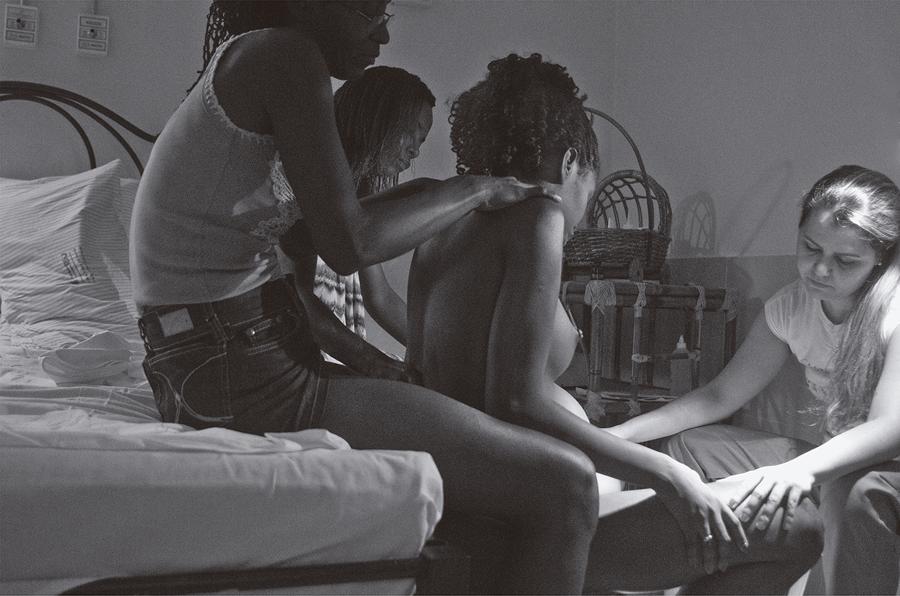

: Birthing scene at Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho (Photo by Adriana Medeiros, 2014).

Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho: natural birth and professional struggles

Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho (CPDCF) shares with other birthing houses the promotion of exclusively natural/physiological/demedicalized childbirth and an aspiration for full control by non-medical staff (nurses, midwives) of the birth process. CPDCF’s staff reject medical interventions, such as the acceleration of labor by oxytocin infusion and episiotomy, which is extremely rare there. Since CPDCF is staffed by obstetric nurses and has no surgical facilities, it cannot administer epidural anesthesia and has no means of dealing with severe complications during childbirth. 1 1 In industrialized countries, debates on medicalized versus natural childbirth are often focused on the availability of peridural anesthesia, while in Brazil the main debate is about the high frequency of C-sections. As a consequence, only women expected to have a complication-free birth are admitted to CPDCF, and those who develop complications during childbirth in spite of the absence of risk factors (approximately 7% of the women admitted to CPDCF) are transferred to hospital, often for a C-section (Pereira et al., 2012PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo et al. Assistência materna e neonatal na casa de parto David Capistrano Filho, Rio de Janeiro Brasil. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental Online , v.4, n.2, p.2905-2913. 2012.).

CPDCF’s staff strongly adhere to the view that childbirth is a normal physiological process. They also explain that with the good preparation of pregnant women, the encouragement of medical personnel and other people (the father of the child, other family members or friends who assist the birthing woman), and respect for all the ways a woman wishes to behave and express herself during childbirth, obstetrical anesthesia is not necessary (Prata, Progianti, 2013PRATA, Juliana Amaral; PROGIANTI, Jane Márcia. A influência da prática das enfermeiras obstétricas na construção de nova demanda social. Revista Enfermagem UERJ , v.21, n.1, p.23-28. 2013.). The alternative ways of dealing with childbirth pain offered at CPDCF are presented as sufficient: “Women don’t need to be afraid – today there are several techniques that are used to relieve pain: dedicated, skilled professionals, the presence of a companion of her choice, the use of the most comfortable positions to give birth, massages, aromas, and dimmed lighting, which make the moment more comfortable, amongst other things” (Rio..., 7 Sep. 2013RIO... Rio é referência em parto humanizado. O Dia , Mundo & Ciência, 7 Sep. 2013. Available at: < https://odia.ig.com.br/_conteudo/noticia/mundoeciencia/2013-09-07/rio-e-referencia-em-parto-humanizado.html> . Access on: 25 Jan. 2018. 7 Sep. 2013.

https://odia.ig.com.br/_conteudo/noticia...

).

: Family assisted by Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho (Photo by Adriana Medeiros, 2014).

Adherence to the ideology of demedicalized physiological birth, the absence of doctors on the premises, and support for birthing women is shared by all birthing houses. What makes CPDCF unique is that it is run by the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS). Its services are free of charge and its users are mainly women from lower social classes. CPDCF’s personnel are very careful to present the clinic as a “community service.” They draw on elements of Brazilian popular culture, from warm colors on the walls and decorations to the sharing of food among patients and the presentation of CPDCF as a quasi-family enterprise that is well integrated into the larger community. Another important trait is the center’s modest size (Romar, 26 Mar. 2014ROMAR, Juliana. Casa de parto da prefeitura completa dez anos com mais de 2300 nascimentos. Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro. Available at: < http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/guest/exibeconteudo?id=4660027> . Access on: 25 Jan. 2018. 26 Mar. 2014.

http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/guest/exibe...

). When the women go for their prenatal tests (which must be done at CPDCF if they wish to give birth there), they meet the staff members who will be present during childbirth (Caixeiro-Brandao, Projianti, 2011CAIXEIRO-BRANDAO, Sandra Maria Oliveira; PROJIANTI, Jane Márcia. Acolhimento como prática, ética, estética e política: estudo de projeto Casa de Parto. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE , v.5, n.10, p.2426-2433. 2011.; Pereria et al., 2012).

Moreover, with a limited volume of deliveries (2,300 babies in ten years, or less than one birth per day) and a low ratio of birthing women to staff members, birthing women are almost certain to receive individualized attention.

: Family assisted by Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho (Photo by Adriana Medeiros, 2014).

Big SUS maternity wards are often unable to provide this kind of individualized care. The staff of larger facilities may be overwhelmed by the number of births at a given moment, women may fail to receive respectful treatment, and many face unnecessary and harmful interventions (Diniz, 2004DINIZ, Simone Grilo. “The cut above’’ and ‘‘the cut below’’: The abuse of caesareans and episiotomy in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters , v.12, n.23, p.100-110. 2004.; Diniz, 2009DINIZ, Simone Grilo. Saúde materna e o paradoxo perinatal. Revista Brasileira de Crescimento e Desenvolvimento Humano , v.19, n.2, p.313-326. 2009.; Leal et al., 2014LEAL, Maria do Carmo et al. Intervenções obstétricas durante o trabalho de parto e parto em mulheres brasileiras de risco habitual. Cadernos de Saúde Pública , v.30, Supl.S17-S47. 2014.). The choice to give birth at CPDCF therefore has obvious advantages. This is attested by several studies, which report a high level of satisfaction of women who have used its services (Seiber, 2008; Caixeiro-Brandao, 2011CAIXEIRO-BRANDAO, Sandra Maria Oliveira; PROJIANTI, Jane Márcia. Acolhimento como prática, ética, estética e política: estudo de projeto Casa de Parto. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE , v.5, n.10, p.2426-2433. 2011.; Pereira, Bento, 2011PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo; BENTO, Amanda Domingos. Autonomia no parto normal: perspectiva das mulheres atendidas na casa do parto. Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste , v.12, n.3, p.471-477. 2011.). The institution also has a good childbirth safety record and is considered to be cost-effective (Pereira et al., 2012PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo et al. Assistência materna e neonatal na casa de parto David Capistrano Filho, Rio de Janeiro Brasil. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental Online , v.4, n.2, p.2905-2913. 2012.; Oliveira 2013OLIVEIRA, Fabiane Azevedo de. Análise parcial dos custos do protocolo assistencial da Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho/Município do Rio de Janeiro . Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. 2013.). In spite of these important advantages, CPDCF has an uncertain future. In 2009, it was at risk of being closed down, and it continues to face institutional difficulties (Azevedo, 2008AZEVEDO, Leila Gomes Ferreira de. Estratégias de luta das enfermeiras obstétricas para manter o modelo desmedicalizado na Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho . Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. 2008.; Moura, 2009MOURA, Carla Fabíola Sampaio de. Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho: a participação das enfermeiras nas lutas do campo obstétrico. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. 2009.; Pereira et al., 2012PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo et al. Assistência materna e neonatal na casa de parto David Capistrano Filho, Rio de Janeiro Brasil. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental Online , v.4, n.2, p.2905-2913. 2012.). CPDCF’s problems are attributed to the persistence of gynecologists’ resistance to the exclusive control of birth by midwives, as well as the fact that CPDCF fails to recruit a sufficient number of users.

Why do so few women from Rio de Janeiro elect to give birth in a user-friendly facility that strives to recreate a warm, family environment? One obvious answer is class: CPDCF is a SUS facility and is not frequented by middle-class women. Affluent Brazilian women who wish to have a “natural birth” can choose one of the (few) upscale clinics that offer such a service. In these clinics, middle-class women can benefit, like CPDCF’s users, from individualized attention, respectful treatment, and avoidance of unnecessary medical interventions. In addition, they give birth in a more deluxe physical setting; if there are complications, they are spared a stressful transfer to hospital; and if they find labor too long or stressful, they can receive epidural anesthesia. Indeed, epidural anesthesia has evolved recently: there are “lighter” variants that do not result in motor block and women themselves can control their own pain relief through a pump. These less constraining forms of epidural anesthesia, often appreciated by women, do however need to be installed by a trained specialist. Their increased uptake may thus reinforce the “hospitalization” and “denaturalization” of childbirth, its dissociation from lay expertise transmitted by women, and, in countries where they are only accessible to affluent women, reinforce inequalities in health care. It is possible that women from lower social classes may be less inclined to adopt the ideology of a minority of middle-class women who view natural childbirth as an empowering event. Less affluent women may be reassured by the larger size of the SUS maternity wards, the presence of doctors and operating rooms, and the possibility to perform a C-section on the spot. It is also plausible that the peripheral location of CPDCF (situated on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro) is also an obstacle, the more so because women who give birth there have to have all their prenatal check-ups there.

What does this project demonstrate?

Women who give birth at CPDCF report they are satisfied with their experience. The main reason they give for their satisfaction is the individualized attention and care they receive (Seibert, Gomes, Vargens, 2008SEIBERT, Sabrina Lins; GOMES, Maysa Luduvice; VARGENS, Octavio Muniz da Costa. Assistência pré-natal da casa de parto de Rio de Janeiro: a visão de suas usuárias. Escola Anna Nery Revista de Enfermagem , v.12, n.4, p.758-764. 2008.; Caixeiro-Brandao, 2011CAIXEIRO-BRANDAO, Sandra Maria Oliveira; PROJIANTI, Jane Márcia. Acolhimento como prática, ética, estética e política: estudo de projeto Casa de Parto. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE , v.5, n.10, p.2426-2433. 2011.; Pereira, Bento, 2011PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo; BENTO, Amanda Domingos. Autonomia no parto normal: perspectiva das mulheres atendidas na casa do parto. Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste , v.12, n.3, p.471-477. 2011.). Many elements typical of the physiological care of birthing women, such as giving them the opportunity to move around during childbirth, take a bath, or receive a massage, are now incorporated, in theory at least, into the routine care of birthing women at other SUS maternity wards (Rio..., 7 Sep. 2013RIO... Rio é referência em parto humanizado. O Dia , Mundo & Ciência, 7 Sep. 2013. Available at: < https://odia.ig.com.br/_conteudo/noticia/mundoeciencia/2013-09-07/rio-e-referencia-em-parto-humanizado.html> . Access on: 25 Jan. 2018. 7 Sep. 2013.

https://odia.ig.com.br/_conteudo/noticia...

). The difference between women’s experiences at CPDCF and other public maternity wards in Rio may be affected not so much by the staff’s support of community values or adherence to the ethos of physiological birth as by other traits of this birthing house, such as its careful choice of users and their small number.

CPDCF serves a pre-selected population. Women eligible to use its services must have a complication-free pregnancy, have never had a C-section or uterine surgery, and be healthy. The birthing house does not accept women who have asthma, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart or liver disease, or any pathology that may negatively impact the birthing process, or women who are severely overweight. It is reasonable to assume that this careful preselection of users increases the probability of favorable outcomes. In addition, it could be hypothesized that the crucial element that promotes the good functioning of CPDCF is its high staff-to-user ratio, which enabled gynecological nurses and midwives to provide attention, support, and care to each pregnant and birthing woman. The most valuable asset of CPDCF’s staff may not be their adherence to the ideal of natural childbirth, but the amount of time they can devote to each birthing woman. The question is whether this demonstrative project could survive any significant scaling up and whether its core principles would be accepted by a significant percentage of women who use SUS maternity services.

Another vexing question may be the issue of pain control. Childbirth is unpredictable, and some women who plan a fully physiological birth may later wish they had access to pain relief. Ideally, all women should be able to choose how they wish to give birth and agree on a pre-established birth plan with their health providers, but also be able to change their mind if the birthing process does not progress as intended. They should also have the chance to give birth in an institution that is not under pressure to be cost-effective, and which offers competent and respectful individualized care to all birthing mothers. A tall order in times of economic crisis and systematic attempts to reduce the services provided by SUS.

REFERENCES

- ARNAL, Maud. The transformations of medicalization of pain relief in the organization of perinatal care system in Quebec. Social Theory and Health . In press.

- AZEVEDO, Leila Gomes Ferreira de. Estratégias de luta das enfermeiras obstétricas para manter o modelo desmedicalizado na Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho . Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. 2008.

- CAIXEIRO-BRANDAO, Sandra Maria Oliveira; PROJIANTI, Jane Márcia. Acolhimento como prática, ética, estética e política: estudo de projeto Casa de Parto. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE , v.5, n.10, p.2426-2433. 2011.

- CHARRIER, Philippe. Diversification des lieux de naissance en France: le cas des Maisons de Naissance. Recherches familiales , v.12, p.71-83. 2015.

- DAVIS, Kathy. The making of our bodies, ourselves: how feminism travels across borders. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2007.

- DINIZ, Simone Grilo. Saúde materna e o paradoxo perinatal. Revista Brasileira de Crescimento e Desenvolvimento Humano , v.19, n.2, p.313-326. 2009.

- DINIZ, Simone Grilo. “The cut above’’ and ‘‘the cut below’’: The abuse of caesareans and episiotomy in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters , v.12, n.23, p.100-110. 2004.

- LEAL, Maria do Carmo et al. Intervenções obstétricas durante o trabalho de parto e parto em mulheres brasileiras de risco habitual. Cadernos de Saúde Pública , v.30, Supl.S17-S47. 2014.

- LEAVITT, Judith. Brought to bed: childbearing in America, 1750 to 1950. New York: Oxford University Press. 1986.

- LOUDON, Irvine. Death in childbirth: an international study of maternal care and maternal mortality, 1800-1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1992.

- MICHAELS, Paula. Lamaze, an international history . New York: Oxford University Press. 2014.

- MOURA, Carla Fabíola Sampaio de. Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho: a participação das enfermeiras nas lutas do campo obstétrico. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. 2009.

- OLIVEIRA, Fabiane Azevedo de. Análise parcial dos custos do protocolo assistencial da Casa de Parto David Capistrano Filho/Município do Rio de Janeiro . Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. 2013.

- PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo; BENTO, Amanda Domingos. Autonomia no parto normal: perspectiva das mulheres atendidas na casa do parto. Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste , v.12, n.3, p.471-477. 2011.

- PEREIRA, Adriana Lenho de Figueiredo et al. Assistência materna e neonatal na casa de parto David Capistrano Filho, Rio de Janeiro Brasil. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental Online , v.4, n.2, p.2905-2913. 2012.

- PRATA, Juliana Amaral; PROGIANTI, Jane Márcia. A influência da prática das enfermeiras obstétricas na construção de nova demanda social. Revista Enfermagem UERJ , v.21, n.1, p.23-28. 2013.

- RIO... Rio é referência em parto humanizado. O Dia , Mundo & Ciência, 7 Sep. 2013. Available at: < https://odia.ig.com.br/_conteudo/noticia/mundoeciencia/2013-09-07/rio-e-referencia-em-parto-humanizado.html> . Access on: 25 Jan. 2018. 7 Sep. 2013.

» https://odia.ig.com.br/_conteudo/noticia/mundoeciencia/2013-09-07/rio-e-referencia-em-parto-humanizado.html> - ROMAR, Juliana. Casa de parto da prefeitura completa dez anos com mais de 2300 nascimentos. Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro. Available at: < http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/guest/exibeconteudo?id=4660027> . Access on: 25 Jan. 2018. 26 Mar. 2014.

» http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/guest/exibeconteudo?id=4660027> - SEIBERT, Sabrina Lins; GOMES, Maysa Luduvice; VARGENS, Octavio Muniz da Costa. Assistência pré-natal da casa de parto de Rio de Janeiro: a visão de suas usuárias. Escola Anna Nery Revista de Enfermagem , v.12, n.4, p.758-764. 2008.

- SIBBALD, Kathryn; PING, Elizabeth. Historical development of nurse midwifery and birthing centers in America? Available at: < https://www.academia.edu/365880/Historical_Development_of_Nurse_Midwives_and_Birth_Centers_in_America> . Access on: 24 Oct. 2018. 6 Nov. 2010.

» https://www.academia.edu/365880/Historical_Development_of_Nurse_Midwives_and_Birth_Centers_in_America> - WALSH, Denis J. A birth centre’s encounters with discourses of childbirth: how resistance led to innovation. Sociology of Health & Illness , v.29, n.2, p.216-232. 2007.

-

1

In industrialized countries, debates on medicalized versus natural childbirth are often focused on the availability of peridural anesthesia, while in Brazil the main debate is about the high frequency of C-sections.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Oct-Dec 2018

History

-

Received

27 Jan 2018 -

Accepted

25 June 2018