Abstract

The present article reflects upon the concepts of work and womens’ work in the light of classic Marxist feminist analyses. It seeks to problematize these categories, beginning with a conversation that took place during ethnographic fieldwork, thinking about what sex work means within the historical a current context of the market for women’s labor. We situate sex work as a variant of reproductive work which still provokes great controversy among significant portions of “progressive” social movements and also among conservative religious sectors, complicating its recognition as a legitimate occupation. We explore some of the possible reasons why sex work, almost alone among the traditional reproductive labor “done out of love”, still generates so much discomfort among such heterogeneous political and social groups.

Work; Woman's Work; Feminist Marxist Theory; Sex Work

Resumo

Este artigo tem como objetivo refletir sobre os conceitos de trabalho e trabalho de mulher à luz das análises marxistas feministas clássicas. A intenção é problematizar essas categorias a partir de uma conversa ocorrida durante a pesquisa de campo etnográfica, pensando o que significa o trabalho sexual dentro do contexto histórico e atual do mercado de trabalho feminino. Situamos essa ocupação como uma variante do trabalho reprodutivo que ainda provoca grandes polêmicas entre parcelas significativas dos movimentos sociais “progressistas” e dos setores religiosos conservadores, dificultando seu reconhecimento como uma ocupação legítima. Exploramos algumas das possibilidades pelas quais o trabalho sexual – quase sozinho entre os tradicionais trabalhos reprodutivos “feitos por amor” – ainda gera tanto desconforto em grupos políticos/sociais tão heterogêneos.

Trabalho; Trabalho de Mulher; Teoria Marxista Feminista; Trabalho Sexual

For some of us, politics is more than just an intellectual exercise – it is lived experience. When the topic is sex work, I don’t think: I feel (Melissa Petro, 2017Petro, Melissa. Kamala Harris’ Whorephobia is Sadly No Surprise. The Establishment, 26.7.2017 [https://theestablishment.co/kamala-harris-whorephobia-is-sadly-no-surprise-250e52ceb3bd. – accessed on 26.7.2017].

https://theestablishment.co/kamala-harri... ).

1- Introduction

The trigger for the present article was an informal conversation that occurred during field work in the interior of the State of Rio de Janeiro, which made me1 1 Although this article is written by two people, the protagonist of the fieldwork that led to the present article, and the article’s primary author, is researcher Ana Paula da Silva. Any use of the first person singular in the present article thus refers to her while uses of “we” refer to both authors. reflect on the women’s work2 2 In general, emic terms appear in this article in quotation marks while key etic terms appear in italics, at least the first time they are used. and particularly on sex work3 3 By sex work, we do not only means prostitution in and of itself, but also all forms of work where people are remunerated for providing sexual services. This includes erotic dancing and massage, phone sex, and the production of pornography. In the context of the present article, this also takes in the traditional duties of women providing their partners (and particularly their husbands) with sexual/affective/erotic attention. For further theoretical considerations regarding this term, see Leigh (1997) and Sutherland (2004). It’s also worth pointing out that, although we do not agree with McKinnon’s theory (1998) that prostitution is necessarily rape, not even this author – whose works are one of the foundation stones of today’s radical feminism – would disagree with the notion that women work when they produce sexual acts/affects. After all, even the labor undertaken in conditions of slavery is work. and how it fits into this category.

The sale of sex is at the center of many controversies, particularly within certain sectors of various social movements that regard the activity as a basic violation of human rights and which therefore feel that the persons exercising it should not be protected by labor laws. These political groups understand people who sell sex as victimized women with no agency at all, who are often described as “enslave” or “raped”, understood to subject to the exploitation of a sex industry portrayed as extremely powerful and profitable. These groups also understand members of the world’s prostitutes movement’s to be traitors or exploiters who are paid to defend this industry and who deserve to be legally punished for encouraging the commercial sexual market4 4 This sentiment has been perhaps Best expressed by English journalist Julie Burchill, who has said that “When we win the sex wars, prostitutes should be shot as collaborators for their betrayal of all women” (apudMcNeill, 2010). Within this perspective, which seems to be gaining more popularity within Brazilian politics, talking about sex work is seen as defending patriarchal violence, the objectification of women’s bodies, and the commoditization of women.

For us, as anthropologists, this position is problematic. We do not deny that prostitution was historically constituted, to a large extent, under patriarchal conditions. The same thing, however, can be said of the institution of marriage and a series of jobs – women's jobs – that do not attract such controversy and are not understood as criminalizable, not even by the more separatist and/or androphobic wings of the feminist movements. In addition, as Lévi-Strauss (1982)Lévi-Strauss, Claude. As estruturas elementares do parentesco. Petrópolis, Vozes, 1982., Sherry Ortner (1940, 1978Ortner, Sherry. The virgin and the state. Feminist Studies, vol.4 #3, 1978, pp.19-35.) and Gayle Rubin (1993)Rubin, Gayle. O trafico de mulheres: notas sobre a “economia política” do sexo, 1993. [Tradução: Sonia Correa] [https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/1919 – 5.5.2017].

https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle...

have pointed out, the sexual/reproductive capacity of women seems to have been among the first “goods” exchanged between human groups. According to David Graeber, pre-capitalist systems of exchange of women most likely served as a basis for human commoditization through slavery (Graeber, 2010). And, if recent research with monkeys can serve as a guide, exchanging sex for sustenance is behavior that may even be pre-human (Chen, 2006)Chen, M. K. How Basic Are Behavioral Biases? Evidence from Capuchin Monkey Trading Behavior. Journal of Political Economy, vol.114, n.3, 2006, pp.517-537.. We do not want to naturalize prostitution, but it seems obvious to us that exchanging sex for money (or for other means of support) is a social behavior that predates capitalism, and even patriarchalism. In the same way, it seems obvious to us that marriage was and still is, in many cases, a patriarchal institution, an opinion that we share with various wings of the feminist movement. However, we do not know of any groups in the world that seek to criminalize marriage: in fact, the trend in the West seems to be to expand the institution to include homoaffective couples. Apparently, then, marriage is a patriarchal institution that is generally seen as reformable while prostitution is not.

When the issue is the sale of sex within the universe of feminized work, our research on the structures of prostitution in Rio de Janeiro and in the world (Blanchette & Silva, 2009; Blanchette & Schettini, pressBlanchette, T. G.; Schettini, C. Sex Work in Rio de Janeiro: Police Management without Regulation. In: Garcia, M. et al. Sex Sold in World Cities: 1600s-2000s. Leiden, Holanda, Brill (prelo).) has indicated two things. First, far from being the ultimate point of degradation in a woman's life, sex work often compares favorably with other feminized jobs, particularly domestic and service labor. Secondly, sex work is hardly a vocation for most of the people who practice it. It is best understood as a temporarily occupied position in a tripartite economy of makeshifts (Hutton, 1974), structured around prostitution, marriage, and jobs of low social status and income, typically feminized.

In other words, sex work is not the worst job in the world, according to the vast majority of our sex working interlocutors. Often, it even appears as that which allows women to exit from other forms of labor, which are understood as more oppressive, more violent, and more objectifying. As Monique Prada, former president of the Central Única dos Trabalhadores do Sexo (CUTS), states:

Basically, prostitution is a place where common sense says no woman should want to be – and yet millions of women have exercised it through the centuries. Perhaps this is far from the worst place in the world for a woman, but there is a whole society striving to make it lousy... And there is a class of people – and I belong to that class of people – for which working with sex, cleaning toilets, or changing diapers of old people are the possible jobs, worthy work, and we do this work. Unfortunately, in the society we live in, we need to keep in mind that not all people have such a wide range of choices which permit them to stay away from precariousness or abusive bosses. Nevertheless, we continue to live and continue to make the choices that are within our reach (apudDrummond, 2017Drummond, Maria Clara. Voz do feminismo no Brasil, a prostituta Monique Prada fala para a Revista J.P. Glamurama, 16.1.2017 [http://glamurama.uol.com.br/voz-do-feminismo-no-brasil-a-prostituta-monique-prada-fala-para-a-revista-j-p/ – acessed on 12.4.20170.

http://glamurama.uol.com.br/voz-do-femin... ).

It is within the context of these disputes that we have produced the present article, which seeks to problematize what is considered as work and – in particular – women’s work, of which we consider prostitution to be a traditional component. We believe that the conflicts between the various sectors of society and people who sell sex are directly related to the type of activity performed (particularly when it is carried out by women), within what Gayle Rubin calls the sex/gender system (Rubin, 1993). What seems to offend, in short, is that something that should be given out of love (or – more historically – out of obligation) becomes commoditized, supposedly making the seller a victim of the capitalist exploitation of her body (McKinnon, 1998). Our intention is to problematize this view through an analysis of the Marxist category of work and how it has been articulated with what is popularly understood as “women's work” in the West.

Although “women’s work” is first and foremost an emic category, the use of which has been registered by ethnologists in various cultures and times5 5 Among numerous examples see Margaret Mead’s notes on “women’s work and men’s,” (March 25, 1932. Typescript. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (136c)), or – more notoriously, Bronislaw Malinowski classic Argonauts do Western Pacific (1976 [1922]). , it has been poorly developed in etic terms. This does not imply, however, that various theorists of social life do not use the term, casually, as if it were something self-explanatory.6 6 See, for example Zelizer (2005:83, 295); Boris (2014:104). It has been widely used within the scope of discussions about housework and reproductive work (Dalla Costa, 1974Dalla Costa, Maria. The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. Bristol, England, Falling Wall Press, 1974.; Federici, 1975Federici, Silvia. Wages Against Housework. Malos Ed., 1975, pp.187–194., 2004Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn, NY, Autonomedia, 2004.) or, more recently, care work (Hirata; Guimarães, 2014Hirata, H.; Guimarães, N. (org.). Cuidado e Cuidadoras. As várias faces do trabalho de care. São Paulo, Atlas, 2012.). For purposes of this article, we take women’s work7 7 When we use this term in its etic sense, as delineated above, it Will generally appear in italics. When it is used in a more emic sense, according to the popular beliefs of a given time or place, it will generally appear in quotation marks. as those forms of toil that, in the West, have historically been understood as the exclusive (or almost exclusive) domain of women, linking certain tasks with the feminine gender. This includes jobs as teachers (particularly of very young children), nurses, cooks, nannies, and all kinds of “care work” (see England, 2005 for a theoretical discussion of this concept), but also, as Barber (1994)Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years - Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. 1994. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. points out, to certain activities that were rapidly proletarianized in the early capitalism of the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly work associated with the production of fabrics (It is no coincidence that the international symbol for “woman” is a spindle). Finally, it includes sexual/reproductive activities and emotional work.

At first glance, then, looking at the historical-cultural context of the West in the last two centuries, “woman’s work” seems broadly similar to the classic Marxist-feminist concept of reproductive work, although we are aware that not all reproductive work is done within domestic spaces (Boris, 2014Boris, E. Produção e reprodução, casa e trabalho. Tempo Social, vol. 26, nº1, São Paulo, Depto. Sociologia-FFLCH/USP, 2014, pp.101-122.:103). As the philosopher and economist Jason Read has pointed out, however, women's work has a specificity in this context: traditionally it has been unpaid labor (Read, 2003Read, Jason. The Micropolitics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the Present. New York: SUNY Press. 2003.:139) and, within the ideological conditions of capitalism, it has been understood as “not work" or, in the words of my interlocutors, work “done out of love”. Over the last hundred years, however, this type of work has been increasingly commoditized, formalized, and even proletarianized. The major exception remains sexual/affective work, particularly under the rubric of prostitution.

Why?

The following article is intended to be an initial theoretical flight in search of an answer to this question. Why, in a world where reproductive and productive work are increasingly confused, where women are increasingly professionalized and/or proletarianized, the "oldest profession" is increasingly criminalized, stigmatized, and unable to be treated as work?

2- Work done for love and men’s work

It was a rainy morning in Canário, in Fazenda Duas Traças, located in the Northwest Fluminense region of the State of Rio de Janeiro, near Santo Antônio de Pádua. Sitting in a chair on a porch, I8 8 Ana Paula da Silva. listened to the stories of D. Genuina, a midwife, landowner, and 81-year-old lady. A descendant of Italian immigrants, D. Genuína is part of the history of a wave of immigrant colonization that spread throughout the interior of the State of Rio de Janeiro from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. The region of Canário has traditionally dedicated itself to family agriculture and has had, according to D. Genuina, significant production of rice and coffee in the past. Currently, these crops have disappeared due to the mechanization of cultivation. Today, the inhabitants of the district survive by planting crops such as okra, tomatoes and pumpkins, as well as working in one or another regional industry such as dairy farming or the mining of decorative stone.

The subject that most caught my attention in conversation with D. Genuina was when she started talking about her trajectory as a woman, remembering the feminine occupations of her youth. These stories were complemented by Nazaré, a much younger woman (in her 40s) and a friend of the family. D. Genuina told me what it was like to be the daughter of the most sought-after midwife in the region. From that, she came to give an opinion on women's work and work done for love. She spoke in a tone of protest, remembering that her mother had been forced to leave home for more than 15 days at a time while waiting for a baby’s birth. In addition, her mother had to take care of the newborn and help with household chores (cooking, washing and ironing) while the child’s mother “recovered”. I asked the two women if this work was remunerated. “No”, they replied. “Everything was done out of love”. The midwife, at most, gained recognition and enjoyed a certain status among the people she attended.

As Marcel Mauss (2013)Mauss, Marcel. Ensaio Sobre a Dádiva. São Paulo, Cosac & Naify, 2013. Coleção Portátil 25. demonstrated in his Essay on the Gift, exchanges that generate prestige (or perhaps what Bourdieu would call social capital [1986]) are in fact closely interwoven with economic structures and not can be ignored in terms of their capacity for reproducing communities. However, it is necessary to remember that the mother of D. Genuina was not a member of a pre-capitalist society, even though she lived in the interior of the state of Rio de Janeiro more than a century ago. As D. Genuina confirmed, money, capital, and the ability to accumulate these reigned supreme in Canário in those days. But the maximum that D. Genuina’s mother, the most sought-after midwife in the region, gained for her toil was maybe a cut of cloth and the “blessing” of baptizing the newborn.

According to Nazaré and D. Genuina, the midwife’s work could be extended for a month. “And there those who took advantage of this”, D. Genuina complained. When I asked who, she replied: “those who had the most possessions”. Nazaré also told her own story of women’s work. It started with her “looking after a little boy” when she was eleven years old. In exchange, she received money to pay for her schooling. Soon after, Nazaré began to wash, iron, cook, and clean for the boy’s parents, although she continued to receive only what had been agreed to beforehand by her parents to “look after the boy”. Nazaré worked under this regime for more than a decade until she was twenty-three years old, when she was able to finish her studies and passed a state examination to work in a public school. Well spoken and using extremely correct Portuguese, Nazaré said that even when she worked hard, she still studied. Her particular pride is that she has read the entire opus of author Clarice Lispector.

Both the trajectory of Nazaré and that of D. Genuina illustrates economist Lourdes Benéria’s observation, made in a report to the International Labor Organization, that, far from being marginal participants in the economy,

rural women are the most forgotten participants in the economy, ‘working’ for long hours in agricultural and domestic tasks, being essential for the economic system, especially in those tasks related to food production and services, in the fields and at home, as well as those related to the reproduction of the labor force (Benéria, apudBoris, 2014Boris, E. Produção e reprodução, casa e trabalho. Tempo Social, vol. 26, nº1, São Paulo, Depto. Sociologia-FFLCH/USP, 2014, pp.101-122.:101).

In fact, the rural economy of Rio de Janeiro in the 20th century (and the 21st century) would be unthinkable without the work done by women – often reified in popular terms as “woman's work” – which, like D. Genuina reminds us, is usually “done out of love” and not for money.

As they told me their trajectories, however, both Nazaré and D. Genuina remembered another woman: a black woman named Mariazinha (according to the two white women, “dark but good”). Mariazinha was repeatedly classified by the women as a “poor girl”. Without a husband and with several children, she was obliged to exercise what the other two women qualified as “men’s work”: farming, since this activity was regularly remunerated in cash. The exact words of D. Genuina, however, give another, moralizing, aspect to Mariazinha’s activities: “the poor thing had to work as a man; she was very poorly spoken of in the region”. It is not known whether Mariazinha had a bad reputation for being black, for having many children out of wedlock, or for exercising the work of men, with men. Most likely, all these factors combined to situate her as “less respectable” than the other women in the village, who performed roles that were typically female and largely “out of love”. I asked D. Genuina (who also worked on a farm, before serving as a lunch lady in a school for 30 years, after part of her 10 children grew up), why Mariazinha was so badly spoken of and not herself, D. Genuina, who had also worked for money and not simply “out of love”. The answer came short, stiff, and with a closed face: “In my case, it was different”. The difference, apparently, was in the fact that Mariazinha never formed a traditional family, having no husband. No one could say, exactly, who the fathers of her children were. Mariazinha went to work on the farm “as a man” and to support her family without a man. Meanwhile, D. Genuina (and Nazaré) only entered the world of “work for money” after long careers dedicating themselves to the reproduction of domestic spaces, already with husbands and children. “Work for money” enters into their trajectories as a complement to their roles as wives and women “working for love” (or, in the case of Nazaré, obligation to parents). Even after entering the world of salaried workers, both women practiced professions traditionally feminized in contemporary Brazil: lunch lady and a primary school teacher. They never needed to “work as a man”, much less to support their families alone. Genuina and Nazaré affirmed that all the children of Mariazinha had graduated from school and left the region. Only one came back to visit his mother. Mariazinha bought a house with her “work as a man”, a small farm that prospered, besides seeing all her children graduated. As far as I could see, her life was not bad. Even so, D. Genuina and Nazaré continued to refer to her as “poor Mariazinha”. You could see that the subtext was moral: working as a man, Mariazinha worked with men; working with men and being single, it was presumed that Mariazinha would perform other functions in the field besides the strictly agricultural. It was presumed, in other words, that Mariazinha was a whore.9 9 We use the word “whore” to express the community’s moral doubts about Mariazinha, which go beyond the question of sex work. Whore is a term used to indicate any woman whose behaviors challenges the expectations of the monogamic family and masculine domination. The word “coitada” (“poor thing”) used by the women to describe Mariazinha should be understood here as a polite way of indicating the Idea that she had done something “unspeakable”: she did not dedicate her sexual and affective attentions to one man alone and was thus a woman of questionable morals – a whore, in other words. Whether or not Mariazinha did, in fact, accept money for sexual services is something that was of secondary interest to my interlocutors.

The above conversations refer to a micro-universe and are particular but emblematic cases. The testimonies of D. Genuína and Nazaré are interesting to think about some of the complex issues embedded in the studies of inequalities in Brazil, however, particularly those of gender, and the combinations and intersections of identity markers in the creation and maintenance of these inequalities through the worlds of work. In the case discussed above, one must look at the historical context within which gender and color/race inequalities intersect with the labor market. This context is absolutely important for our attempts to analyze those occupations categorized as “degrading” and undervalued, but which in many cases end up being the economic havens of women who cannot sustain themselves “out of love”. To better understand this question, it is necessary to analyze the nature of the work and how this has been coupled with the qualifier "woman" within the Marxist-feminist tradition.

3- Women’s work: from the (im)productive to the reproductive and the sex/gender system

As Gayle Rubin comments,

No theory accounts for the oppression of women – in its endless variety and monotonous similarity, cross-culturally and throughout history – with anything like the explanatory power of the Marxist theory of class oppression (Rubin, 1993Rubin, Gayle. O trafico de mulheres: notas sobre a “economia política” do sexo, 1993. [Tradução: Sonia Correa] [https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/1919 – 5.5.2017].

https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle... ).

Initially, however, Marxism hardly touched on the issue of women's work in the domestic space (Read, 2003Read, Jason. The Micropolitics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the Present. New York: SUNY Press. 2003.).

Karl Marx inherited the question of the value and meaning of the work of the liberal theorists of the previous generation, and particularly of Adam Smith, who first theorized the distinction between productive and unproductive work, situating the first category as that work that produces value or wealth, while the second category produces nothing - only shifts wealth from one place to another (Smith, 2003Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. New York, Bantam Classics 2003 [1776]. [1976]). In this second category, Smith placed the works of “clergymen, lawyers, doctors, learned men of all kinds, players, buffoons, musicians, opera singers and dancers, etc.”. These people could work, but they did not produce value or wealth. The main characteristic of unproductive work, according to Smith, is that it “produces nothing that could later buy ... an equal amount of labor” and that it “is eliminated at the time of its production” (Smith, 2003Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. New York, Bantam Classics 2003 [1776]. [1976], Book II, Chapter III, second paragraph). Smith (2013)Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. New York, Bantam Classics 2003 [1776]. does not say anything about what we might understand as “women’s work”, but the first paragraph of Book II, cp. III of The Wealth of Nations indicates that he would not consider “domestic” work as necessarily unproductive, since within the category of productive labor he placed that which adds to the maintenance of the worker.

Marx, on the other hand, devoted much effort to theoretically distinguishing between productive and unproductive labor. To give full account of this discussion is a quasi-theosophical task, which goes far beyond the scope of this article. We can say that Marx initially followed Smith by defining productive labor as "that which is directly exchanged for capital," while unproductive labor would be "absolutely established" as that which is not exchanged for capital, but for some form of income (Marx, 2013Marx, Karl. Theories of Surplus Value. New York, Pine Flag Books, 2013 [1863]. Organizado por Karl Kautsky. [1863]:303). Within this initial formulation, Marx seems to reject the idea that work that produces only services, not goods, can be productive in some way or another. However, his thoughts on this subject were not fulfilled when Marx died, necessitating a reconstruction of his ideas. For the purposes of our discussion, the question is whether labor that produces immaterial services (such as the vast majority of domestic work) can be considered productive or just necessary and reproductive jobs of the social economy.10 10 Those readers who are interested in following this debate can Begin by reading Tarbuck’s analysis (1983) and Miller’s reply (1984).

It is important to note here that productive and unproductive have no moral connotation in Marx’s understanding of the terms: they are only etic terms that denote a certain relationship between work and capital. So-called nonproductive jobs can be socially useful. There are a number of jobs where work is not exchanged directly for capital, but is needed for the circulation of capital (lawyers who create contracts, for example). And there is also work that produce use value but is not exchanged for capital. Marx notoriously offers the example of the tailor who works for a particular client in his home. The work of the tailor who toils under these conditions is not productive, for he has no connection with capital and his production is not transformed into a commodity that can be freely exchanged in the market (Marx, 2013:402).

More orthodox Marxists like Ken Tarbuck are reluctant to consider as productive any work that produces immaterial goods or services. However, there is ample evidence that Marx, at the end of his life, was moving away from this position. After all, in the first volume of Capital, which represents the more mature presentation of Marx’s ideas about the distinctions between productive and unproductive work11 11 As Tarbuck observes, Volume I of Capital was the only volume that had been written, rewritten, edited and re-edited according to Marx’s desires while he was still alive. Volumes 3 and 4 (the last contained in Marx 2013 [1863]) were actually written before Volume I (Tarbuck, 1983). , he stated that

a teacher is a productive worker when... he works as a horse to enrich the owner of a school. The fact that this used his capital in the construction of a teaching factory instead of a sausage factory does not change the relation at all (Marx, 2007Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy - The Process of Capitalist Production. New York, Cosimo, Inc. 2007 [1867].[1867]:558).

Obviously, for the mature Marx, the most distinguishing factor of work as productive was its articulation to capital:

Being a productive worker implies not only a relation between labor and usefulness between the worker and the product of his toil, but also a specific social relationship of production, a relationship that ... marks the worker as the direct means of producing surplus value (Marx, 2007Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy - The Process of Capitalist Production. New York, Cosimo, Inc. 2007 [1867].[1867]:558).

As Ian Gough reminds us, it is necessary to account for the changes that have taken place in capitalism in the last 150 years in our analysis of labor productivity. According to Gough, in Marx’s time,

the capitalist mode of production spread and grew gradually, conquering the field of material production, but hardly touching non-material production. Workers who thus produced material goods were often productive laborers employed by capitalists, while workers who provided services were usually paid with some form of income and were unproductive workers. [However] (…) the growth of services provided by capitalist enterprises qualifies this observation nowadays (Gough, 1972Gough, Ian. Productive and unproductive labour in Marx. New Left Review, no 76, 1972, pp.47-67.:53).

In other words, the works that produce services, the results of which are consumed in the act of production, may well be qualified as productive works, provided that they generate capital. This was perhaps not so clear in 1867, but it is a fact that is more than obvious nowadays.

All thinkers involved in this debate would agree, however, that work done for money (or other considerations) would only be productive work if it generated capital. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this meant that the bulk of what would have been called “women's work” was not, in fact, productive work: it could help in the circulation of value and in maintaining the social conditions of but was not directly exchanged for capital.

In this way, the classical Marxist thinkers of this period, such as Rosa Luxemburg and Alexandra Kollontai, widely understood women through two categories: bourgeois and proletarian. The first (in the words of Luxembourg) “play no role in social production, being the joint consumers of the surplus value their males derive from the proletariat: they are the parasites of the parasites of the people”. Luxembourg continues, clearly distinguishing housework from productive labor:

The women of the proletariat... are economically independent; are engaged in productive labor for society, just as men are. Not in the sense of helping their men through domestic work, and dragging themselves through daily survival while educating children for hardly any pay. This work is not productive within the meaning of the current economic system of capitalism... (Luxembourg, 1971 [1912]).

Kollontai would echo these sentiments even more relentlessly in 1921 after the Bolshevik Revolution, situating wives in general as parasites and equating them with prostitutes:

To us in the workers’ republic it is not important whether a woman sells herself to one man or to many, whether she is classed as a professional prostitute selling her favors to a succession of clients or as a wife selling herself to her husband. All women who avoid work and do not take part in production or in caring for children are liable, on the same basis as prostitutes, to be forced to work.12 12 Kollontai here suggests what should be done with stay-at-home wives and/or prostitutes: the State should transform them into slave laborers. We cannot make a difference between a prostitute and a lawful wife kept by her husband, whoever her husband is – even if he is a “commissar”. It is failure to take part in productive work that is the common thread connecting all labour deserters. The workers’ collective condemns the prostitute not because she gives her body to many men but because, like the legal wife who stays at home, she does no useful work for the society (Kollontai, 1977Kollontai, Alexandra. Prostitution and Ways of Fighting it. In: Holt, A. (ed.) Alexandra Kollontai: Selected Writings. London, Allison and Busby, 1977 [1921].[1921]).

For Kollontai, then, traditional “woman's work” carried out in the domestic sphere for the reproduction of a family was, in fact, social desertion. It was fully comparable to prostitution and remedied only through collectivized productive labor – forced, if necessary. For both Kollontai and Luxemburg, being a proletarian woman, then, meant working outside the domestic sphere, in factory production directly related to capital. In these quotations we see an extremely literal interpretation of Marx's initial thoughts about productive work, with the traditional “woman’s work” being disqualified as unproductive and even as “not work”, at least in its social sense. This is the style of Marxism that created the phenomenon of labor camps and rehabilitation for "suspicious" women after successful socialist revolutions.13 13 For an excellent – if fictional – portrayal of these attitudes and their results, we suggest the film Virgem Margarida (2013) by director Licinio Azevedo, which deals with the imprisonment and “re-education” of “parasitic” women after the Mozambique Revolution of 1975. For a brief description of the situation in Cuba following the revolution there, see Wolfe (2014).

Even here, though, we can see some gaps in classical Marxist orthodoxy. After all, there was a kind of “woman’s work” that Kollontai understood as necessary and therefore worthy of respect, even if it was not properly “productive”: caring for children. And Luxembourg, in turn, recognized that certain forms of sex work could be productive labor, given that these involved the exchange of services for capital:

Only the labor that produces surplus value and capitalist profits is productive... From this point of view, the dancer in a cafe, who generates profits for her employer with her legs, is a productive worker, while all the toil of the women and mothers of the proletariat within the four walls of the home is considered unproductive work (Luxembourg, 1971 [1912]).

Even Engels, writing in that seminal work on gender studies, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, slides away from orthodoxy by comparing prostitutes with working women (if not proletarians) in his famous statement that a woman in a traditional bourgeois marriage “only differs from the ordinary courtesan in that she does not let out her body on piece-work as a wage-worker, but sells it once and for all into slavery” (Engels, 1884Engels F. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State: In the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan. NY, International Publishers, 1972 [1884].). Although Engels’s use of the word “wage-worker” leaves doubt as to whether he would consider sex work to be productive or just another form of non-productive "piece work" (work for the production of use value and not capital), the prostitute here is situated as similar to Marx’s the teacher, needing only a direct link to capital to be understood as full proletarian.

The feminist appropriations of Marxism during the last third of the 20th century, however, were necessary for a full reassessment of what we call women's work. In her book Marxism and the Oppression of Women (2013 [1983]), considered to be fundamental Marxist-feminist text, historian Lisa Vogel situates Juliet Mitchell (1966), Margaret Benston (1970) and Peggy Morton (1971) as founders of this tradition. It was Italian author Mariarosa Dalla Costa (1972), however, who constructed the first theoretically sophisticated attempt to engage, in Marxist and feminist terms, with what we are calling women's work.

Breaking with classical Marxism, Dalla Costa argues that the work traditionally carried out by women in the domestic sphere is productive work in the strictest sense, since it produces the most essential commodity of capitalism: the worker himself. The added value of this labor is indirectly expropriated by the payment of wages to the woman's proletarian husband, thus transforming her into “the slave of the wage-laborer” (Dalla Costa, 1973:52). Dalla Costa’s claim, however, did resolve the central problem of the debate: it demonstrated that domestic labor had a social use upon which capitalism was dependent, yes, but it could not situate this as a social form of labor that produced capital. In other words, although Dalla Costa proved that domestic labor could not simply be understood as unproductive labor, she failed to demonstrate how it was directly exchanged for capital. The husband continued as an intermediary between woman and capital, complicating the strict proletarianization of women as domestic workers (Vogel, 2013 [1983]).

The most interesting solution to this theoretical impasse was the constitution of the concept of the mode of reproduction. This was understood as a sphere of social production of human beings – both in everyday life (washing clothes, cooked, etc.) and intergenerationally (creating and educating the next generation) – which, in the words of the theorist Renate Bridenthal, existed in a dialectical relationship with the mode of production (Vogel, 2013 [1983]:27). In her article “The Traffick in Women”, anthropologist Gayle Rubin famously labeled this “second sphere” of (re)production as the sex/gender system. Rubin distinguishes, however, between the concept of reproductive system and that of the sex/gender system, avoiding a strict division between production and reproduction and proposing a more holistic and interwoven view of these two spheres (Rubin, 1993).

Rubin agrees with Dalla Costa’s synthesis, finding it crucial in order to understand the reproduction of the labor force as one of the necessary costs of capital generation (pointing out that even Marx and Engels recognized this sine qua non of capitalism) and situating this cost as socialized through institutions. However, Rubin also comments that nothing in capitalism necessarily implies the association of women with the sphere of reproduction, noting that female oppression, sexism, and traditional notions of gender predate capitalism. In other words, capitalism uses and benefits from the association of women with the reproductive sphere, but does not give create this confinement. Rubin understands that the origin of the “world historical defeat” of women predates the capitalist mode of production, emphasizing that it has essentially cultural and traditional roots, or – adopting Marxist language –“moral and historical origins”:

It is precisely this “historical and moral element” which determines that a “wife” is among the necessities of a worker, that women rather than men do housework, and that capitalism is heir to a long tradition in which women do not inherit, in which women do not lead, and in which women do not talk to God. It is this “historical and moral element” that presented capitalism with a cultural heritage of forms of masculinity and femininity. It is within this “historical and moral element” that the entire domain of sex, sexuality, and sex oppression is subsumed. And the briefness of Marx’s comment only serves to emphasize the vast area of social life that it covers and leaves unexamined. Only by subjecting this “historical and moral element” to analysis can the structures of sex oppression be delineate. (Rubin 1993Rubin, Gayle. O trafico de mulheres: notas sobre a “economia política” do sexo, 1993. [Tradução: Sonia Correa] [https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/1919 – 5.5.2017].

https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle... :5).

Rubin’s arguments, along with her concept of the sex/gender system, are particularly important for our purposes. However, they do present some small, but crucial, distinctions into the concept of the mode of reproduction. Rubin does not deny that there is a second sphere of (re)production in the dialectic that sustains any historical formation, but warns that we must avoid separating this sphere from the productive sphere in absolute terms, proposing a more intertwined and imbricated vision of the two spheres. Rubin describes as “cultural” the origin of the segregation of spheres by gender, and warns that changes in this system are possible without necessarily overcoming capitalism. Indeed, the author's observation is that women do not need to be confined to one of these spheres: women have a place in productive work, as well as the proletarianization of traditionally domesticated reproductive work, and the confusion of the (re)productive spheres has only intensified in modern capitalism.

In Brazil, the last seven decades has seen an explosion in the economically active female population (from 13.6% in 1950 to 48.9% in 201014 14 Os dados vêm de 2010, apudAlves et al., 2017. ), 57.9% of this made up of formalized female workers15 15 Os dados vêm de 2012, apudAlves et al., 2017. (Alves et al., 2017Alves, J.E.D.; Cavenaghi, S.M.; Carvalho, A. A.; Soares, M.C.S. Meio Século de Feminismo e o empoderamento das Mulheres no contexto das Transformações Sociodemográficas do Brasil. In: Blae, E; Avelar, L. (org.) 50 Anos de Feminismo: Argentina, Brasil e Chile. São Paulo, EdUSP, 2017. Pp. 15-55.:14-16). It is necessary to qualify this growing participation of women in the formal economy, however, because in Marxist terms, being “economically active” or having a signed labor contract does not necessarily mean one engages in productive work. A cleaning lady, for example, who is employed directly by a housewife does not swap her labor force to capital, even though her toil might be formalized by a labor contract. It is significant to note in this context that 15% of the Brazilian women registered by IBGE in 2012 as "economically active" worked in domestic employment – this percentage grows significantly when we add color/race to the analysis, since 19% percentage of economically active black women work in domestic labor as against only 11% of economically active white women. Women are also still massively concentrated in the service and commerce sectors: in 1999, 56.6% of economically active Brazilian women were located in these areas of the economy (IBGE, 1999)IBGE. Pesquisa nacional por amostra de domicílios: PNAD de 1999. Brasília, IBGE, 1999..

According to the above data, the only thing we can say with any degree of certainty is that, as workers, Brazilian women have increasingly left the domestic sphere over the last half century, receiving money to work in spaces that do not correspond to their domicile or the homes of others. Much of this female labor force still seems tied to activities that could be considered as traditional “women’s work”, however, being concentrated in the area of services, education, care work and housework. What percentage of this expanded extra-domestic sphere is composed of productive labor no one can say. However, a considerable part of the forms of reproductive work that were once confined to the domestic and private spheres are now being capitalized and transformed, moving to the more traditionally productive sphere. A clear example of this would be the shift of the cook’s job from the domestic space to fast food franchises, canteens, and popular restaurants. The young girl employed by McDonald’s may be employed in the service economy, but her toil unquestionably produces capital while still being understood as a form of reproductive labor. In this way, the productive and reproductive spheres are increasingly confused without necessarily threatening the functioning of capitalism.

Although not every form of labor done by women today is productive, unquestionably the work traditionally “done for love” within the domestic space is increasingly being transformed into productive jobs, done for salary and by contract, generating capital and surplus. This transformation is neither simple nor neat, nor does it necessarily generate the relative feminine independence through proletarianization that Luxemburg and Kollontai imagined. To understand it better, we must now look at how it was foreshadowed in the historical constitution of the threshold sphere of women's work performed for income, not love.

4- Madams, servants and work relations in the mode of reproduction

The activities of washing, cooking, caring for children/the old/the sick, listening, empathizing, and having compulsory sexual relation16 16 It is important to remember here that sex is not only procreative: it is also reproductive of daily life, in the sense explored by Rubin, following Marx. Leaving aside the arguments about whether or not sex is a biological necessity, it is certainly understood to be a basic necessity in historical and moral terms in the vast majority of capitalist cultures. Therefore, as “beer is necessary for the reproduction of the working class in England, just as wine is in France” (Marx, apudRubin, 1993:4), a certain level of access to sexual relations is necessary for reproduction of the proletariat almost everywhere in the world. The “boom” of the last 40 years of sexual services and products aimed at women (the sale of erotic products and the presentation of these as a form of self-care [Gregori, 2013]; romantic trips to tropical destinations to create sexual encounters [Beleli, 2015]) indicate that this need is not only male and that it is also growing among women. are all forms of toil that were traditionally understood as domesticated and feminine tasks in the West. However, as Anne McClintock shows in her book Imperial Leather (2010), this kind of work needed to be invisible, at least in the case of the domestic spaces of the metropolitan bourgeoisie (and middle-class-in-formation) of the 19th century. Here, it was under the sign of leisure and love that the work of woman disappeared. The housewife's vocation “was not only to create a clean and productive family, but also to ensure the skilful concealment of every sign of her work”:

Her success as a wife depended on her skill in the art of working and apparently not working... The dilemma of these women was that the more convincing their performance of leisure work was, the greater their prestige. But this prestige was won not by leisure itself, but by a laborious imitation of leisure (McClintock, 2010McClintock, Anne. Couro Imperial: Raça, Gênero e Sexualidade no Embate Colonial. Campinas-SP, Editora da Unicamp, 2010.:244).

This imperative for invisibility created a contradiction within the mode of reproduction: the housewife gained prestige – or social capital – insofar as she kept her home absolutely flawless and productive. However, this state of comfort and hygiene had to appear as something that emanated from the housewife's own graceful nature: a task virtually impossible for one woman.

In this way, an increasing demand for the domestic labor of women in spaces that were not their own homes was generated. And this, for its part, further blurred the boundaries between production and reproduction:

Servants thus became the embodiment of a central contradiction within the modern industrial formation. The separation between the public and the private spheres was achieved only by paying working-class women for housework that wives could do for free. The work of servants was indispensable to the process of transforming the working capacity of wives into the political power of husbands. But the figure of the paid servant constantly endangered the “natural” separation between the private house and the public market. Silently crossing the boundaries between the private and the public, between the home and the market, between the working class and the middle class, servants brought to the middle-class house the smell of the market, the smell of money. Domestic workers thus embodied a double crisis in historical value: that between the paid labor of men and the unpaid labor of women and another between the economy of feudal servitude and the industrial economy of wages (McClintock, 2010McClintock, Anne. Couro Imperial: Raça, Gênero e Sexualidade no Embate Colonial. Campinas-SP, Editora da Unicamp, 2010., 247).

According to McClintock (2010)McClintock, Anne. Couro Imperial: Raça, Gênero e Sexualidade no Embate Colonial. Campinas-SP, Editora da Unicamp, 2010., the complex dialectic between production and reproduction under conditions of modern capitalism was not simply expressed in a division between housewives and working men. There were millions of women –perhaps most, particularly in the new urban spaces that exploded in modernity – who found no place in the home (at least as "housewives") and also could not find steady work proletarizing themselves through direct exchange with capital. A complex hierarchy was thus established within the modern bourgeois house, Certain women became housewives, while other women, usually poorer (and, in the Americas, darker) became servants, key pieces in maintaining the comfort, efficiency, and political capital of the bourgeois family. These “servants” exchanged their labor power not for capital, as proletarian workers did, but for an income (or even for simple sustenance) in a space structured simultaneously by patriarchal logic and by the new bourgeois ideology of respectability. In this way, domestic labor, transferred from the hands of bourgeois wives into the hands of women of subordinate classes (and races), became, throughout modernity, a form of invisible labor, central to the (re)production of poverty, race, and gender.

In any case, proletarian is an adjective that does not account for the lives of these women. They often migrated constantly between the reproduction sphere (as wives), to the productive sphere (being employed in factories), to service work (employed in reproductive tasks in other women's homes), to prostitution. We are currently involved in a project (Garcia, et al, forthcomingGarcia, M.R.; Van Voss, L.H.; Meerkerk, E. (ed.) Sex Sold in World Cities: 1600s-2000s. Leiden, Holanda, Brill (prelo).) that investigates the history of prostitution in twenty global cities. One of the striking features of women's work in almost all the cities studied (particularly the Western ones) is how it was built into what the historian Olwen Hufton (1974)Hufton, O. H. The Poor of Eighteenth-Century France 1750–1789. Oxford, Clarendon, 1974. calls “the economy of makeshifts”: a patchwork quilt of occupations through which the poor seek to piece together survival. One of the most common trajectories detailed in the case studies of the project is the woman who migrates from the countryside to the city because she does not fit into the rural marital market, needing to sell her labor either as a proletarian woman or in the domestic space of another woman as a servant. Typically, however, these solutions prove to be precarious or insufficient, so the woman also ends up selling sex. Other women in this situation end up marrying, but nonetheless continue to toil outside the domestic space of their own home - often even as sex workers. Can we call these feminine lives, simply, proletarian, in the classical and Marxist sense of the word?

The question is more interesting than it may seem at first sight, for if we are taking seriously the great insight of Marxist feminism as to the existence of a mode of reproduction that exists in a dialectical relation with the mode of production, we must ask ourselves about the nature of social relations of labor that exist within the sphere of reproduction and which positions of power these relations produce. The mode of production notably generates the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. What does the mode of reproduction generate?

A simple way to solve this question would be to presume that the sex/gender system does not modify labor relations at all, with the woman acquiring the position of her husband and/or father, or even by understanding “proletarian” in its popular Brazilian meaning as a synonym simple of “poor”. Another way would be to understand women in themselves as a class. This seems to be the stance adopted by various strands of the “radfem”17

17

We use “radfem” as na emic category employed by self-labeled radical feminists who seek to understand prostitution via the works of authors such as Andrea Dworkin, Julie Bindel, Sheila Jeffreys, Catharine Mackinnon, and Melissa Farley, among others.

movement, exemplified by the writings of journalist Meghan Murphy (2015)Murphy, Meghan. 9 things that really do make you a better feminist than everybody else, 11.9.2015 [http://www.feministcurrent.com/2015/09/11/9-things-that-really-do-make-you-a-better-feminist-than-everybody-else/ – accessed on 12.3.2017].

http://www.feministcurrent.com/2015/09/1...

. For Marx, “woman” was definitely decisive for placing certain human beings in the sphere of reproductive work, regardless of the class situation of their male relatives. But, as Avtar Brah points out (2006), although women may indeed be the “second sex”, globally, this does not make sisterhood global. Women should not be understood as a homogenous group, subject to a unique and ineffable “female experience”, united in their class interests – a fact commented on by black feminism in the United States almost half a century ago (Davis, 1981Davis, Angela. Women, Race and Class. 1981. New York: Vintage Books., Collins, 2000Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought. New York, New York, Routledge, 2000.).

Moreover, in terms of the social relations of labor within the sphere of reproduction, some women are placed to buy and/or manage the labor that others must offer. We agree with McClintock (2010)McClintock, Anne. Couro Imperial: Raça, Gênero e Sexualidade no Embate Colonial. Campinas-SP, Editora da Unicamp, 2010.: what is produced in the bourgeois metropolitan house of the 19th century is the “political power of husbands”. It would be more correct to say, however, that this production results in a series of symbolic, cultural, social, and political capitals, which may be appropriated by husbands, but which gain more prominence in the constitution and maintenance of what is properly called a Woman (singular and exemplary). For as the feminist theologian Elizabeth Schussler-Fiorenza has shown in analyzing the case of the classical patriarchy in ancient Greece, not every woman is a Woman:

Strictly speaking, female slaves and foreign female residents are not women. They are “gendered”, not with respect to male slaves or resident alien men, but with respect to their masters. They are subordinate and therefore “different by nature”, not only from elite men but also from elite women. As a result, the patriarchal pyramid of domination and subordination creates “natural differences” not only between men and women, or men and men, but also between women and women (Fiorenza, 1993Fiorenza, Elisabeth Schussler. But She Said: Feminist Practices of Biblical Interpretation. Boston, Beacon Press, 1993.).

In modern capitalism, this singular, exemplary Woman is the one McClintock (2010)McClintock, Anne. Couro Imperial: Raça, Gênero e Sexualidade no Embate Colonial. Campinas-SP, Editora da Unicamp, 2010. calls “bourgeois”. She is usually married to a man of this class, or is born to a father and mother of this class, but she is perhaps best conceived through another category, which arises in the sphere of reproduction. By borrowing an emic term from Brazilian reproductive relations, we can call this Woman the madam (although housewife also serves). And although she is still under the masculine domination of the patriarch, the madam dominates her servants in a manner which is analogous to the way in which the bourgeois dominates his workers. It is the madam who extracts the symbolic capital of the productive and hygienic leisure of the exemplary home, transforming it into something politically useful. Typically, she does this through the expropriation of her servants’ labor. And although the typical madam may be bourgeois and white (as McClintock presents her), not every madam is necessarily white or bourgeois.

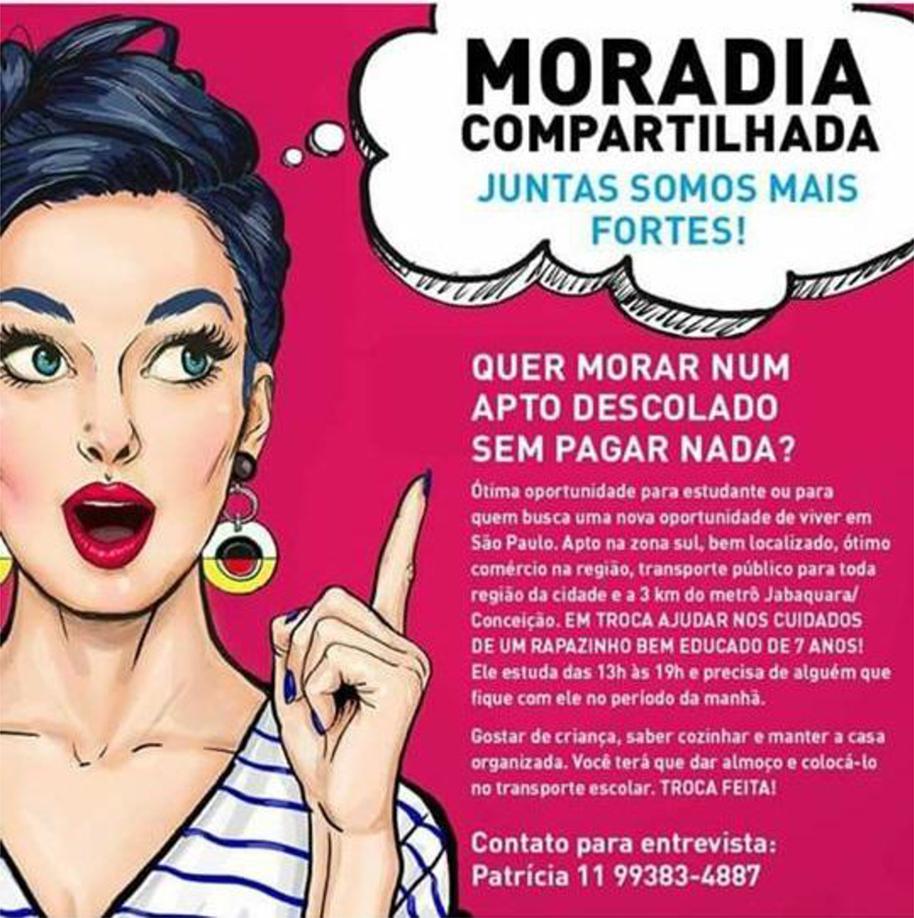

Being a housewife and being able to have servants was and still is an ambition for many women. In regions such as Brazil or the southern United States – which were strongly marked by African slavery in the nineteenth century and by an abolition that was reluctant to integrate the freemen and – women into the modernizing economy – racism and misery ensured that this ambition could be achieved by many who were less well-off than in the more metropolitan regions of the global system. In Brazil, this impetus is revealed in our traditional popular habit of “pegar para criar” (or "take to raise"), where even working-class, peasant, or middle-class families can appropriate children workers (as was the case with Nazaré) “who are almost family" and thus bound by obligations that can only be paid with labor for love. In fact, the tradition of "loving" housework is so dear and rooted in Brazilian culture that, to this day, it is difficult to find a flat or apartment, even the most modern ones, which do not include a maid's room on the premises.

5- (Re)produtive work, sex work, and the “economy of makeshifts”

The category servant has declined in size compared to other categories of women’s work in the last century. This is the case even in Brazil, where a significant portion of the female population is still economically active in the sale of domestic services. At the same time, there has been a growing proletarianization of reproductive work (Coburn, 1994Coburn, David. Professionalization and Proletarization: Medicine, Nursing, and Chiropractic in Historical Perspective. Labour/Le Travail, 34 (Fall), 1994, pp.139-162.; Réses, 2012Réses, Erlando Silva. Singularidade da profissão de professor e proletarização do trabalho docente na Educação Básica. SER Social, vol. 14, no 31, 2012, pp.419-452.; Read, 2003Read, Jason. The Micropolitics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the Present. New York: SUNY Press. 2003.). Indeed, it seems that the confusion between the sphere of reproduction and production is increasing. If we want to adopt Rubin’s perspective, perhaps it would be better to say that the overlapping interdependence of these two spheres has intensified to the point where they are increasingly congruent (even though, it must be pointed out, they were never entirely separate).

However, this “collapse” has not significantly changed the feminization and invisibility of reproductive work. The reproduction of family life continues to be thought of as a feminine obligation, expressed in the famous “double job” of salaried labor and housework. In other words, it remains the respectable woman’s responsibility to create a clean and productive family while ensuring the skilful concealment of every sign of housework –- even if she herself works outside the home. Nowadays, we can see this imperative in the numerous advertisements for household products and technologies that promise (for example) to eliminate bathroom odors without anyone noticing that they once existed. These products are displayed by women in mini-dramas that are directed almost exclusively towards the female consumer. Ironically, these advertisements are often the only dramatic productions on television that can pass the famous “Bechdel test”.18 18 Created by cartoonist Allison Bechdel, a fictional work passes the test IF, at some point, at least two women talk to each other about something other than a man.

But there is another kind of invisibilization under way: the proletarianization of the reproductive labor force within the service economy, which conceals the class difference between women that was earlier made explicit in the relationship between madams and servants. An excellent example of this "erasure" can be seen in the book Laughter Out of Place, where the anthropologist and Brazilianist Donna M. Goldstein (2013)Goldstein, Donna. Laughter Out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2013. directs a scathing critique of Brazilian middle-class families’ dependence on the domestic work usually performed by black and poor servants:

[These families] are constantly being looked after by others, usually women, who do the onerous tasks of everyday life, freeing up time for creative activities, including career advancement, hobbies, and an active social life. Engaged intellectuals, therefore, can work hard and still play the role of gracious hosts... (Goldstein, 2013Goldstein, Donna. Laughter Out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2013.:31)

Goldstein’s observation is insightful, but we should ask how she makes her own life possible as an engaged American intellectual. Who does the “burdensome tasks of everyday life” for Donna Goldstein and women like her? Who produces free time for her creative activities, hobbies, and professional advancement? Is it not the proletarianization of the reproductive tasks that, in the past were conducted by (mostly female) servants? Goldstein's discomfort with the Brazilian middle classes’ use of maids has, as its background, the normalization (and invisibilization) of another regimen of reproductive and feminized labor, one which is almost certainly amply utilized by the American anthropologist and which is growing in Brazil.

The work of professional women as university teachers, lawyers, designers and etc. is supported by a legion of workers earning the minimum wage or less. Today, the management of this work is often outsourced, making the madam a manager. Often, this labor is proletarianized, being productive (i.e., generating capital) as well as reproductive. Women, however, continue to be principal consumers of the services this labor produces, often paying for them with money received through their own salary. In this way, the class division among women, formerly operating in the reproductive sphere and expressed by the madam/created binomial, remains active. It can be glimpsed in the division between those women whose professional life is made possible through the consumption of reproductive services and those who need to sell their labor force to provide reproductive services, even though this sale is now increasingly made directly through capitalists, owners of service companies, and not to the family in the domestic sphere. A significant difference between the two systems, however, is that this proletarianization intensifies the illusion that (re)productive work has no origin, gender, or color.

Perhaps for this reason, a certain wing of feminism – most associated with the class of the madams – is reluctant to understand the perennial attraction of prostitution as a work option for many women. To better understand this apparent blindness, we need to move away from theory and offer up a brief summary of some of the salient findings of our ethnological investigations into prostitution and its related political issues.

Since 2004 we have investigated prostitution, sex tourism, and trafficking in women in the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.19 19 Our intellectual production is available on our Lattes curriculos: http://buscatextual.cnpq.br/buscatextual/busca.do?metodo=apresentar As a function of this research, we are also engaged in observation/participation in the Brazilian and international political fields that seek to combat human trafficking and reform prostitution laws – both as researchers and as allies of the organized prostitute movement. Our research has demonstrated the mismatch between how prostitution is imagined in Brazilian society and how it is presented and lived by its main protagonists, the women who sell sex.

During the course of our research, we have witnessed a growing acceptance of abolitionism20 20 Abolitionism: the political position that equates female prostitution with slavery and seeks to abolish it, generally through the intervention of the State and the partial or total criminalization of all or some of the actors involved in the sale and/or purchase of sex. in Brazilian civil society. Base on this sentiment, there are claims that prostitution is fundamentally an act of violence and an activity that no woman in her right mind would engage in unless she had no other choice at all. In public event after a public event, we have heard people, often women who claim to be feminists, equating the sale of sex with rape and slavery. What has impressed us on these occasions are three things that are often repeated: the women in question are usually white and middle class21 21 Obviously, there are Black and/or poor women who oppose prostitution, particularly those women involved in religious organizations. We have found relatively few women of this sort, however, at the public events where legislation regarding prostitution and/or trafficking of persons has been discussed. As we have described elsewhere (Blanchette and Silva, 2013), these events are majoritarily composed of white, middle class people who have a relatively high level of formal education. ; they have little or no contact with sex workers; and they seem to understand work as “exploitive” in the life of women only insofar as it involves the sale of sex.

This third characteristic is the most important in the context of this article. A typical conversation from our field work can illustrate what we mean. This happened recently in a lecture at UFRJ that discussed the decriminalization of prostitution. The protagonists were Thaddeus and Sandy22 22 The names of all informants have been changed to maintain anonymity.. , a 21-year-old white graduate student in law, who classified herself as Marxist, feminist, and as a member of a socialist party. The researcher began by asking what was the position of the girl and her party regarding the Gabriela Leita Bill, which would regulate sex work. The resulting dialogue was as follows:

Sandy: We are against prostitution because it exploits women.

Thaddeus: But all the work from which surplus is extracted is exploitation, is not it? You support the fight for labor rights in other areas of the economy, do you not, regardless of that fact? Why can’t sex workers have these rights?

S: Because no one chooses to be a prostitute. Women only do this when they are forced to because they do not find any other job.

T: And do you think the other jobs that are traditionally 'womanly' - clerk, cook, day laborer, manicurist - are freely chosen by women?

S: No one wants to be a prostitute.

T: Are there people who want to be supermarket cashiers?

S: But prostitution is a patriarchal institution. It serves no other purpose. It is undignified work that hurts all women. It is essentially a form of rape or slavery.

T: Are you in favor of gay marriage?

S: Of course. Marrying who you want is a human right.

T: But isn’t marriage also a patriarchal institution? Women who work in it as wives, at home, reproducing the family but who do not earn a single penny – can’t these women also be thought of as captive?

S: Marriage is not like that today.

Even for this young woman who claims to be a Marxist and a feminist, work is not ipso facto exploitative: there is a moral divide that separates “good” jobs from “bad”. There are “dignified” jobs – and in this category one finds almost all feminized service labor, proletarianized or not – and “undignified” jobs, of which prostitution is the prime example.23 23 Domestic labor also appears in a minority of these discourses as “undignified labor”. In addition, marriage is seen by this young woman as something that is done essentially by choice or for love and not as an economic institution. In this view of the world, no woman would "choose" to work in sex, and by contrast, all other forms of work (including domestic and unpaid labor) are “voluntary”.

The conversation reported above is absolutely “normal” in the Durkheimian sense: it always appears in public events where the (de)criminalization of prostitution is discussed. But the characterization of sex work and other forms of work presented here differs, quite a lot, from that presented by the great majority of our sex worker interlocutors.

First, the power to give or withhold consent for access to one’s body is extremely important to our prostitute interlocutors. The majority of these women make a clear separation between prostitution and sexual violence and distinguish, with many details, the differences between the two. They point out how consent is not something simple, offered or denied only once. Rather they describe it is a complex process of constant (re)negotiation during the course of sex work. Sex workers describe boundaries beyond which they do not venture. If these are forced, they understand this as violation. This praxis is in stark contrast to the notion that prostitutes will accept everything the client wants, once the client pays: the good old stereotype of the prostitute who “sells her body”. We have not found any sex worker who would agree with the idea that what they sell is free access to their bodies, a kind of free pass for a sexual “anything goes”. In fact, many of our interlocutors qualify the notion that the prostitute “sells her body” as a “psychopathic” attitude: they feel that it is the attitude of the kind of person who intends to torture or kill women, and sex workers distinguish clients from this sort of person.

More importantly, most of our interlocutors do not describe prostitution as the “last option before death”. Most describe it as unpleasant work which nevertheless demonstrates clear advantages over the other occupations available on their horizon of possibilities. It is significant that, almost without exception, these women demonstrate varied histories of engagement with other forms of work prior to their entry into sex work. The list of previous occupations revealed by our last field incursion includes: waitress, bakery attendant, housekeeper, nanny, elementary school teacher, cook, construction worker, security, weaver, manicurist, clerk, supermarket cashier, telemarketer, saleswoman in a mall, and hairdresser. But the most common occupation (which almost all of our interlocutors have gone through) is wife, with the woman being economically supported by a husband.24 24 It is important to acknowledge that there are many reasons to sell sex and that each social class has its prostitutes. Here, we are principally talking about women who make prostitution their primary means of sustenance – workers, in other words.

Noteworthy here is the quantity of these occupations – the large majority – that can be classified as service labor, reproductive labor, or even “women’s work”. In fact, the past occupations of our prostitute interlocutors paint a well-delineated picture of what U.S. feminists call the “pink collar ghetto”: marginalized and underpaid jobs that are historically done almost exclusively by women (Napikoski, 2017Napikoski, Linda. What is a pink collar ghetto? Thought Co. March 3rd, 2017 [https://www.thoughtco.com/pink-collar-ghetto-meaning-3530822 – accessed on 14.07.2017].

https://www.thoughtco.com/pink-collar-gh...

). More remarkable still is how many of these women have formally worked in proletarian occupations: only a minority has never worked with a formal contract, or in jobs that generated capital. However, this formalization and proletarianization has rarely translated into work situations that our interlocutors consider "dignified". A good example would be the experience of Luana, a 28-year-old black woman who was hired in the construction industry after three years of sex work in downtown Rio:

They used me to seal tiles in the bathrooms of one of those new condominiums here in Downtown. I had a signed work card and everything. So I thought “Yeah! Here we go!”. And I stopped whoring. After six weeks, however, I still hadn’t received my first paycheck. Worse, we worked without any protection and the chemicals we used caused open wounds on my arms and hands. I had to stay away from work for three days with a medical excuse, but when I got back, they fired me. They never paid me for the six weeks of work I did and they still have my work card. So I came back here [a brothel in the Center]. At least here I get paid.

We rarely hear prostitution presented as the only work available to women in an economic picture marked by unemployment and total misery. In general, we have heard many more stories of women who have left other jobs to sell sex. Ironically, it was after the outbreak of the current economic crisis in 2015 that we have seen a notable increase in the number of women seeking to leave prostitution for other forms of economic survival. In the words of one of our Carioca interlocutors, “A man who does not receive a salary does not usually go to a whorehouse”.

But the most salient feature of these women’s work histories is their rotation through different economic positions in what can only be described as a 21st century version of Hufton’s “economy of makeshifts” (1974). The circulate constantly through the domestic sphere of (re)productive labor (as wives), low paid feminized work in the service sector, and sex work. These three positions are presented by the women as complementary and equally (un)avoidable, each having its own problematic characteristics and rewards.

The story of one of our interlocutors – “Julia” (carioca, white, 24, residing in the Complexo do Alemão favela – who worked for a time as a sales clerk at Lojas Americanas (a local department store), exemplifies this circulation:

I got married four years ago when I became pregnant [at the age of 17]. Except my ex- was very jealous and we fought all the time. It couldn’t work. So when my daughter was 3, I left him and started working here [in a brothel in Downtown]. Two years ago, I applied for a position as a sales clerk at Lojas Americanas and I got it! I was so happy because it was a real job and I thought, “That’s okay. It’s a small salary, but I can grow in the company”. My mother [who knew that the woman worked in prostitution] was also happy, because this [prostitution] can make you money, but it has no future and is disgusting. Only the job didn’t work out. They said they needed to train me, but the job was no big deal [i.e. difficult]. It was months earning almost nothing because I was still in the training phase. And when it was over, the salary was still small. If I worked there for years, I could gain seniority and earn more, but my father died, my mother is retired ... If I do not earn money, I can’t raise my daughter. So I had to leave Lojas Americanas and come back here [to the brothel]. The work is what it is, but is it good to have a signed work card and starve to death?

It is important to note that most of our interlocutors do not like sex work. Like Julia, they find prostitution unpleasant. But, as several of them have pointed out during our years of fieldwork, “Since when do you work because you like it?”. When we ask about the work histories of these women, we always ask them if they would leave prostitution to return to the jobs of their past. Almost without exception, the answer is “not likely unless I can earn far more than I earned”.

The reason most quoted by our interlocutors for quitting prostitution is marriage, not work outside the sex trade. But marriage has its own problems, as the story of Julia stresses, usually associated with male domination (jealousy, domestic violence, controlling attitudes, etc.) and lack of money. The end of a marriage is also constantly cited by our interlocutors as a reason to (re)enter into prostitution.

It is this patchwork economy of makeshifts, delimited by the positions of being a wife, being a poorly paid worker in the service economy, and being a prostitute (and the possibility of moving between these positions or combining them in various ways), which we can perhaps usefully label as women's work, in an etic sense. Within this triangle, sex work rarely appears as “the last option”, at least in the words of our interlocutors. Rather, it is presented as a resource that allows women to leave an abusive relationship; which allows them to raise their children with a modicum of dignity; which generate the resources needed to build or purchase a home, or a business of their own. It is, above all, the space in which women “work for themselves”, raising capital for their own projects that would be unattainable through toil in the service sector. In this sense, it is also strongly contrasted by our interlocutors with domestic space, where the woman is chained to the needs of the family unit under male domination.