Abstracts

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma is increasing worldwide. Since it has an aggressive behavior and difficult to treat in more advanced stages, early diagnosis is essential for cure. Dermoscopy is an auxiliary diagnostic method that allows an increase in the diagnostic accuracy for cutaneous melanoma using a hand-held microscope with a 10-fold magnification - a dermatoscope. The pattern analysis method is considered a reliable procedure to teach dermatology residents. It is based on global and specific patterns that enable classifying melanocytic and non-melanocytic lesions (which are important in the differential diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma). Among melanocytic lesions, dermoscopy is useful in recognize benign, suspect or malignant lesions.

Dermatology; Dermoscopy; Diagnostic imaging; Diagnosis differential; Melanoma

A incidência do melanoma cutâneo tem aumentado mundialmente e, por tratar-se de neoplasia bastante agressiva e de difícil tratamento em estádios mais avançados, o diagnóstico precoce é fundamental para a cura do paciente. A dermatoscopia surgiu como exame auxiliar in vivo, que tem papel fundamental na realização do diagnóstico precoce e amplifica a acurácia diagnóstica do melanoma. Para a realização do método, é necessário utilizar o dermatoscópio, aparato que permite aumentar a lesão, no mínimo, 10 vezes. A imagem obtida é interpretada utilizando-se o método diagnóstico da preferência do examinador. O método de Análise de Padrões é atualmente o mais utilizado e o que possui maior acurácia para o diagnóstico do melanoma cutâneo, tendo-se demonstrado confiável para o ensino de residentes em dermatologia. Baseia-se em padrões globais e específicos que permitem diferenciar as lesões melanocíticas das não melanocíticas (também importantes no diagnóstico diferencial com o melanoma cutâneo), assim como identificar lesões melanocíticas consideradas benignas, suspeitas ou malignas.

Dermatologia; Dermatoscopia; Diagnóstico por imagem; Diagnóstico diferencial; Melanoma

REVIEW ARTICLE

Dermoscopy: the pattern analysis* * Work done at Hospital do Câncer de São Paulo A.C.Camargo - São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Gisele Gargantini RezzeI; Bianca Costa Soares de SáII; Rogério Izar NevesIII

IPhD student in Oncology from the Graduate Course of the Fundação Antonio Prudente. Master´s degree in Oncology from the Graduate Course of the Fundação Antonio Prudente. Attending Dermatologist of the Department of Cutaneous Oncology of the Treatment and Research Center, Hospital do Câncer de São Paulo A.C.Camargo - São Paulo (SP), Brazil

IIMaster´s degree in Oncology from the Graduate Course of the Fundação Antonio Prudente. Attending Dermatologist of the Department of Cutaneous Oncology of the Treatment and Research Center, Hospital do Câncer de São Paulo A.C.Camargo - São Paulo (SP), Brazil

IIIPhD in Medicine from the Graduate Course of the Medical School - Universidade de São Paulo - USP - São Paulo (SP). Director of the Department of Cutaneous Oncology of the Treatment and Research Center, Hospital do Câncer de São Paulo A.C.Camargo - São Paulo (SP), Brazil

Correspondence Correspondence Gisele Gargantini Rezze R. Barata Ribeiro, 380 cj 34 - Bela Vista 01308-000 - São Paulo - SP E-mail: ggrezze@ludwig.org.br

ABSTRACT

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma is increasing worldwide. Since it has an aggressive behavior and difficult to treat in more advanced stages, early diagnosis is essential for cure. Dermoscopy is an auxiliary diagnostic method that allows an increase in the diagnostic accuracy for cutaneous melanoma using a hand-held microscope with a 10-fold magnification a dermatoscope. The pattern analysis method is considered a reliable procedure to teach dermatology residents. It is based on global and specific patterns that enable classifying melanocytic and non-melanocytic lesions (which are important in the differential diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma). Among melanocytic lesions, dermoscopy is useful in recognize benign, suspect or malignant lesions.

Keywords: Dermatology/methods; Dermoscopy; Diagnostic imaging/methods; Diagnosis differential; Melanoma/diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of melanoma has doubled all over the world in fair-skin patients over the past 10 years.1 The highest incidence and mortality rates in the world are recorded in Australia, where it is the most common type of cancer in men and it ranks second in women, in the age group 15-44 years; therefore, it is considered a public health problem.2

Data from the Instituto Nacional do Câncer (INCA), in Brazil, show an estimate of 5760 new cases for 2006; in that, 2710 in men and 3050 in women.3 These data might not characterize the Brazilian reality, which is supposed to have a much higher incidence. At the Hospital do Câncer de Sao Paulo A.C. Camargo, there are approximately 200 new cases per year, that is, 10 new cases out of 2200 monthly appointments (unpublished data).

Cutaneous melanoma is a neoplasm that affects young individuals, has an aggressive nature, and it is refractory to current treatments in cases with metastases.4,5 Its cure is related to excision of tumor at an initial phase and the need of early diagnosis is well established.6 Since pigmented lesions are sometimes not diagnosed by their clinical characteristics even by experienced professionals, further criteria are required for more accurate clinical diagnosis of skin lesions. Dermoscopy was created as an auxiliary method to evaluate these lesions.7,8

Dermoscopy, also called surface microscopy or epiluminescence microscopy or dermatoscopy,9-15 is a method to visualize the structures located under the stratum corneum and indicated to make diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions, such as cutaneous melanoma in its initial phases and infiltration.7,16

The accuracy of clinical diagnosis of melanoma made by a dermatologist not using a dermatoscope was estimated as 75-80%; this rate is lower if diagnosis is made by residents in Dermatology or Internal Medicine.17 However, by performing a dermoscopic examination, a diagnostic accuracy of approximately 90% could be achieved for cutaneous melanoma.17 It is obvious that such accuracy is associated with experience of the examiner and his/her training about dermoscopic criteria,18 which could be fundamental.

The technique to perform dermoscopy consists of using an optical device that has a variable magnification of 6 to 400X. The dermatoscope most often used is a portable device with 10X magnification, which has a light beam, emitted by a halogenous bulb that strikes at a 20º angle on the skin surface. The skin is previously prepared by applying some fluid (oil, water, gel or glycerine) on the interface between the epidermis and the glass slide of the device in order to avoid light reflection. Light penetrates and enables visualization of dermoscopic features mainly related to the presence of the pigment melanin in different skin layers (epidermis and dermis), hemoglobin of vessels and dermal fibrosis.18

In search for instruments that provide greater diagnostic accuracy and improve follow-up of pigmented lesions, the dermoscopic devices are increasingly lighter and easier to handle. Some use polarized light, which is more potent and does not require the use of fluids, making the examination faster. The resources for digital dermoscopy have also improved, enabling monitoring of pigmented lesions throughout time by storing digital images and exporting suspected lesion images to other centers for discussion about diagnosis.18

PATTERN ANALYSIS METHOD

The Pattern Analysis method was first described by Perhamberger et al., in 1987, and standardized by the Consensus Hamburg, in 1989.19,20 This methodology defined the characteristic dermatoscopic patterns of pigmented skin lesions and was updated by the Consensus Net Meeting of 2000.18,21,22

It is the method most commonly used in dermoscopy for providing greater diagnostic accuracy for cutaneous melanoma. Moreover, in a recent study, it was demonstrated that it is the most reliable method to teach dermoscopy for residents (non- experts) in Dermatology.18,22,23

PATTERN ANALYSIS OF MELANOCYTIC LESIONS

To use this diagnostic method, the physician should first identify if the pigmented skin lesion is melanocytic or non-melanocytic. The presence of pigmented network, globules or dots characterizes the melanocytic lesions, whereas the blue nevus has a homogeneous blue-grayish area that determines its diagnosis.18,21,22

If the lesion presents none of the dermatoscopic features mentioned above, it is a non-melanocytic lesion. Therefore, specific criteria are used for diagnosis, which include findings of seborrheic keratoses, hemangiomas and angiokeratomas, pigmented basal cell carcinomas and dermatofibromas.21,22

The melanocytic lesions are identified by their general dermoscopic features, defining their global pattern, or by specific dermoscopic criteria that determine their local pattern (when it is not possible to define a global pattern). The specific dermatoscopic criteria used include regular pigmented network, irregular pigmented network, dots, globules, pseudopods, branched streaks, blue-whitish veil, regression areas, hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation areas (blotches).18,22

1. GLOBAL PATTERN

The global pattern is determined by the predominantly dermatoscopic feature in the lesion that enable its diagnosis.

Reticular pattern

In the reticular pattern there is a predominant presence of regular pigmented network or pigmented network in “honeycomb”. Histologically, the lesion presents basal cell layer hyperpigmentation and/or melanocytic hyperplasia, which may correspond to a junctional nevus, compound nevus, lentigo or melanosis.18

Globular pattern

The presence of multiple aggregated globules prevails in globular pattern. The globules may have different colors (black, brown, blue or gray) depending on how deep (epidermis, papillary dermis and reticular dermis) the pigment (melanin) is. Some lesions have light or pinkish globules with less pigmentation. The globular pattern has high specificity for diagnosis of compound and intradermal nevi.18

Cobblestone pattern

Globules also predominate in this pattern but they are large, closely aggregated (“fitted”) and somehow angulated globule-like structures resembling a cobblestone.18 (Figure 1).

Pointillist pattern

This pattern was recently described and is characterized by brown or grayish dots of regular size and uniform aspect on a slightly brownish basis. It is typically found in compound and intradermal nevi.24

Homogeneous pattern

Presence of diffuse and homogeneous blue-grayish pigmentation is observed and absence of pigmented network characterizes the blue nevi.18

Parallel pattern

This is the pattern found in palmoplantar lesions. Pigmentation along the superficial sulci occurs in 40% of benign palmoplantar melanocytic nevi (parallel sulcus pattern); whereas pigmentation along the rete ridge (with presence of eccrine glands) is observed in 86-98% of acral melanomas (parallel ridge pattern).18

Starburst pattern

It is characterized by the presence of pigmented streaks or pseudopods regularly distributed throughout the periphery of the lesion and intense pigmentation in the central area, which confers a starburst aspect. It occurs in 53% of spindle and/or epithelioid cell nevi (nevi of Reed or pigmented Spitz nevi).18

Multicomponent pattern

This pattern has high specificity for diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma and consists of presence of three or more dermoscopic feature in one single lesion. The characteristics that could be observed are presence of multiple colors, irregular pigmented network and/or hyperpigmented network (prominent), pseudopods, branched streaks, blue-whitish veil, regression areas (depigmentation or peppering), brown or black globules of irregular shape and unevenly distributed within the lesion, peripheral black dots, hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation (blotches) areas.18 (Figure 2).

2. LOCAL PATTERN

The presence of specific dermoscopic feature in different regions of the same lesion contribute to making diagnosis of melanocytic lesions and are called local pattern.

Junctional nevus

It presents regular pigmented network (honeycomb), of brownish and uniform color that is more prominent in the center, with gradual fading to the borders (reticular pattern). It may present black or brown globules and dots regularly distributed inside the lesion (usually in the central region).

Compound nevus

The pigmented network is generally discreet and peripherally located, presenting homogeneous central pigmentation or brown, black or blue-greyish globules and dots distributed in the center of the lesion (Figure 3). Some lesions present a hypopigmented area of regular and central aspect. The globular, cobblestone and pointillist global patterns also characterize the compound nevi.

Intradermal nevus

It is characterized by absence of pigmented network and presence of globules and dots, and may have a nodular aspect due to globules with little pigmentation or normal skin-like color. The papillomatous lesions may have follicular pseudo-openings and assume a globular, cobblestone or pointillist pattern.

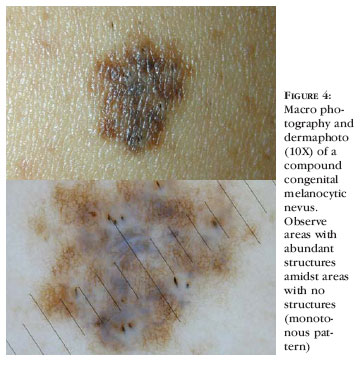

Congenital nevus

The small nevi usually have a globular or cobblestone pattern, whereas the larger nevi present areas with no structures amidst other that are rich in structures, and this pattern repeats throughout the lesion (monotonous aspect).18 (Figura 4).

Blue nevus

It has a homogeneous blue-greyish pattern, with no pigmented network, dots and globules. Diffuse hypopigmentation may be found due to deposition of collagen in the dermis and/or brown veil resulting from basal cell layer hyperpigmentation (Figure 5). Some lesions may have linear projections at the periphery mimicking pseudopods (structures called pseudo-pseudopods).18

Spindle and/or epithelioid cell nevi

The nevi of Reed and pigmented Spitz nevi could display a starburst, globular (homogeneous central pigmentation and peripheral brown globules) or atypical (no defined dermoscopic features) pattern. In 25% of lesions with an atypical dermatoscopic pattern the pathological examination shows atypia.25

The Spitz nevi are less pigmented and have na inverted network aspect characterized by lighter rete ridges around the darker globules (Figure 6).

Recurrent nevus (persistent nevus or pseudomelanoma)

These nevi occur after incomplete exeresis of a nevus and have a bizarre pigmentation and a white region corresponding to healing area.26,27

Atypical nevi

The dermatoscopic criteria for diagnosis of an atypical nevus are considered a challenge. The Pattern Analysis method has a diagnostic accuracy of approximately 76% for these lesions.28 The most common dermoscopic features found are listed in chart 1.18

Cutaneous melanoma

The lesions display an asymmetric aspect, with polymorphism of structures and colors and irregular shape (Figure 7). The most common characteristics are shown in chart 1. Some cutaneous melanoma lesions may have an inverted network, as described for Spitz nevi, and they are important in their differential diagnosis.18

Pattern Analysis of non-melanocytic lesions

The non-melanocytic lesions are important for the differential diagnosis with melanoma. These lesions have no network, globules or dots at dermoscopy, but have specific dermatoscopic features that define their diagnosis.

Hemangiomas and angiokeratomas

The dermoscopic features of hemangiomas and angiokeratomas are presence of blue-reddish color, blue-reddish lakes, scaring depigmentation (around vascular spaces, outlining the lake structures). When eruptive hemangiomas present thrombosis they become darker, with a black colour that is relevant for the differential diagnosis with cutaneous melanoma. Angiokeratomas show a peripheral clear structure (“jelly”) due to presence of acanthosis.18

Seborrheic keratoses

They are characterized by structures denominated horny pseudocysts, follicular pseudo-oppenings, cerebriform or fingerprint pattern and absence of pigmented network and globules.18

Pigmented basal cell carcinoma

The pigmented basal cell carcinoma is characterized by absence of pigmented network and presence of at least one dermoscopic finding: spoke wheel areas, large blue-greyish ovoid nests, multiple blue-greyish globules, maple leaf-like areas (or “glove finger”), arborizing or tree-like telangiectasias and ulceration.29 (Figure 8)

Pigmentation in basal cell carcinoma is primarily related to presence of melanin in the tumor mass (hyperplastic melanocytes or melanosomas phagocyted by the tumor) and is important in differential diagnosis with cutaneous melanoma, particularly if much pigmented.18,29

Dermatofibroma

The main dermoscopic features of dermatofibromas are a central white scarlike patch, subtle peripheral pigmented network, brown dots and globules and reddish coloration around the central scarlike patch.18,30,31 (Figure 9)

Despite its well-defined dermoscopic features, palpation is useful to make diagnosis (the lateral compression of the lesion makes a typical central depression or dimple).18

CONCLUSION

Today dermoscopy is a useful and essential technique to clinically manage pigmented skin lesions, and it plays a fundamental role in early identification of malignant pigmented lesions (cutaneous melanomas). The Pattern Analysis should be learned and disseminated because it is the most accurate method to diagnose cutaneous melanoma and is extremely reliable to teach non-experienced physicians.

REFERENCES

Conflict of interest: None

- 1. Lorentzen H, Weismann K, Petersen CS, Larsen FG, Secher L, Skodt V. Clinical and dermatoscopic diagnosis of malignant melanoma: assessed by expert and non-expert groups. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:301-4.

- 2. Marks R. The changing incidence and mortality of melanoma in Austrália. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2002;160:113-21.

-

33. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Estimativas/2006: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2005. p. 39.

- 4. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Nickoloff B, McClatchey K, Mihm MC, Ross JS. Molecular pathology of malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:788-94.

- 5. Shen SS, Zhang PS, Eton O, Prieto VG. Analysis of protein tyrosine kinase expression in melanocytic lesions by tissue array. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:539-47.

- 6. Soyer PH, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Corona R, Sera F, Talamini R, et al. Three-Point Checklist of Dermoscopy. Dermatol. 2004;208:27-31.

- 7. Dal Pozzo V, Benelli C, Roscetti E. The seven features for melanoma: a new dermoscopic algorithm for the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:303-8.

- 8. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Ruocco V, Chimenti S. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions (Part II). Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:483-98.

- 9. Soyer HP, Smolle J, Hodl S, Pachernegg H, Kerl H. Surface microscopy: a new approach to the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:1-10.

- 10. Yadav S, Vossaert KA, Kopf AW, Silverman M, Grin-Jorgensen C. Histopathologic correlates of structures seen on dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy). Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:297-305.

- 11. Nachbar F, Stolz W, Merkle T, Cognetta AB, Vogt T, Landthaler M, et al. The ABCD rule of dermatoscopy: high prospective value in the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:551-9.

- 12. Stolz W, Braun-Falco O, Bilek P, Lanthaler M, Cognetta AB. Colour atlas of dermatoscopy. Oxford : Blackwell Scientific; 1994. p 3.

- 13. Menzies SW, Crotty KA, Ingvar C, McCarthy WH. An atlas or surface microscopy of pigmented skin lesions. New York : McGraw-Hill; 1996. p 1.

- 14. Menzies SW. Surface microscopy of pigmented skin tumours. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38(Suppl 1):S40-3.

- 15. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, De Giorgi V, Sammarco E, Delfino M. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions: comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-70.

- 16. Rezze GG, Scramim AP, Neves RI, Landman G. Structural correlations between dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoma and histopathology using transverse sections. Am J Dermatophatol. 2006;28:13-20.

- 17. Menzies SW, Gutenev A, Avramidis M, Batrac A, McCarthy WH. Short-term digital surface microscopic monitoring of atypical or changing melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1583-9.

- 18. Rezze GG, Soares de Sá BC, Neves RI. Atlas de Dermatoscopia Aplicada. São Paulo: Lemar; 2004. p.19-109.

- 19. Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K. in vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions.I. Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:571-83.

- 20. Bahmer FA, Fritsch P, Kreusch J, Pehamberger H, Rohrer C, Schindera I, et al. Diagnostic criteria in epiluminescence microscopy: Consensus Meeting of the Professional Committee of Analytic Morphology of Society of Dermatologic Research, 17 November 1989 in Hamburg. Hautarzt. 1990;41:513-4.

- 21. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Chimenti S, Menzies S, Pehamberger H, Rabinovitz H, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: an atlas based on the consensus Net Meeting on dermoscopy 2000. Milan: Edra; 2001.

- 22. Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, Talamini R, Corona R, Sera F, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:679-93.

- 23. Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, Stante M, Ricci L, Brunasso G, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in Dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:981-4.

- 24. Huynh PM, Glusac EJ, Bolognia JL. Pointillist nevi. J Am Acad Dematol. 2001;45:397-400.

- 25. Argenziano G, Scalvenzi M, Staibano S, Brunetti B, Piccolo D, Delfino M, et al. Dermatoscopic pitfalls in differentiating pigmented Spitz naevi from cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:788-93.

- 26. Marghoob AA, Kopf AW. Persistent nevus: an exception to the ABCD rule of dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:474-5.

- 27. Stolz W, Braun-Falco O, Landthaler M, Burgdorf WHC, Cognetta AB. Atlas colorido de dermatoscopia. Traduzido por Araujo RSB. 2 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Di-Livros; 2002. p. 98.

- 28. Pehamberger H, Binder M, Steiner A, Wolff K. in vivo epiluminescence microscopy: improvement of early diagnosis of melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:356-62.

- 29. Menzies SW, Westerhoff K, Rabinovitz H, Koff AW, McCarthy WH, Katz B. Surface microscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1012-6.

- 30. Ferrari A, Soyer HP, Peris K, Argenziano G, Mazzocchetti G, Piccolo D, et al. Central scarlike patch: a dermatoscopic clue for the diagnosis of dermatofibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1123-5.

- 31. Wang SQ, Katz B, Rabinovitz H, Kopf AW, Oliviero M. Lessons on dermoscopy # 6 Dermatofibroma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:807-8.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

24 July 2006 -

Date of issue

June 2006