Abstract:

BACKGROUND:

Atopic dermatitis is a highly prevalent inflammatory and pruritic dermatosis with a multifactorial etiology, which includes skin barrier defects, immune dysfunction, and microbiome alterations. Atopic dermatitis is mediated by genetic, environmental, and psychological factors and requires therapeutic management that covers all the aspects of its complex pathogenesis.

OBJECTIVES:

The aim of this article is to present the experience, opinions, and recommendations of Brazilian dermatology experts regarding the therapeutic management of atopic dermatitis.

METHODS:

Eighteen experts from 10 university hospitals with experience in atopic dermatitis were appointed by the Brazilian Society of Dermatology to organize a consensus on the therapeutic management of atopic dermatitis. The 18 experts answered an online questionnaire with 14 questions related to the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Afterwards, they analyzed the recent international guidelines on atopic dermatitis of the American Academy of Dermatology, published in 2014, and of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, published in 2018. Consensus was defined as approval by at least 70% of the panel.

RESULTS/CONCLUSION:

The experts stated that the therapeutic management of atopic dermatitis is based on skin hydration, topical anti-inflammatory agents, avoidance of triggering factors, and educational programs. Systemic therapy, based on immunosuppressive agents, is only indicated for severe refractory disease and after failure of topical therapy. Early detection and treatment of secondary bacterial and viral infections is mandatory, and hospitalization may be needed to control atopic dermatitis flares. Novel target-oriented drugs such as immunobiologicals are invaluable therapeutic agents for atopic dermatitis.

Keywords:

Atopic dermatitis; Interleukins; Inflammation; Keratinocytes; Skin barrier

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease, with lesions showing typical morphology and distribution, and whose hallmark is intense pruritus. AD presents in patients with a personal or family history of atopic diseases such as asthma, rhinitis, or AD itself. It is one of the most frequent diseases of childhood, and its prevalence reaches up to 20% in infants and 2.1 to 4.9% in adults in Europe, North America, and Japan.11 Eichenfield LF, Ellis CN, Mancini AJ, Paller AS, Simpson EL. Atopic dermatitis: epidemiology and pathogenesis update. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(3 Suppl):S3-5.

2 Watson W, Kapur S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7( Suppl 1):S4-33 Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, Girolomoni G, Puig L, Simpson EL, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: Results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73:1284-1293 Annual incidence of new cases of AD in patients below the age of 17 in the US is 11%; 85% of AD patients first manifest the disease before the age of 5, but 20-40% of children with AD persist with the skin disease in adulthood. 44 Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6 Suppl):S118-27.,55 Ozkaya E. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:579-82. In the Brazilian population, prevalence of AD symptoms according to Solé et al. was 8.2% in children and 5.0% in adolescents. 66 S Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Mallozi MC, Naspitz CK; Brazilian ISAAC Group. Prevalence of atopic eczema and related symptoms in Brazilian schoolchildren: results from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) phase 3. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2006;16:367-76.

Due to the complex pathogenesis of AD, which involves skin barrier defects, immune dysfunction, and microbiome alterations mediated by genetic, environmental, and psychological triggers, a single therapeutic approach is hardly capable of achieving disease control. 77 Orfali RL, Zaniboni MC, Aoki V. Profile of skin barrier proteins and cytokines in adults with atopic dermatitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:140-7. Increased transepidermal water loss (TEWL), decreased stratum corneum water content, and reduced expression of skin barrier proteins such as filaggrin and claudin 1 are the main alterations of the skin barrier in individuals with AD. 88 Batista DI, Perez L, Orfali RL, Zaniboni MC, Samorano LP, Pereira NV, et al. Profile of skin barrier proteins (filaggrin, claudins 1 and 4) and Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1091-5.

9 Elias PM, Hatano Y, Williams ML. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1337-43.-1010 Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulewicz KJ, Wang CQ, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1344-54.

Of note is the cytokine dysregulation, leading to Th2, Th1, Th17, and Th22 polarization, which varies according to age, ethnicity, and AD phase. 1111 Czarnowicki T, Gonzalez J, Shemer A, Malajian D, Xu H, Zheng X et al. Severe atopic dermatitis is characterized by selective expansion of circulating TH2/ TC2 and TH22/TC22, but not TH17/TC17, cells within the skin-homing T-cell population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:104-115.e7.

12 Leung DY. New insights into atopic dermatitis: role of skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Allergol Int. 2013;62:151-61.-1313 Shi B, Bangayan NJ, Curd E, Taylor PA, Gallo RL, Leung DYM, et al. The skin microbiome is different in pediatric versus adult atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1233-6.

Skin microbiome plays a crucial role in AD; about 90% of the skin of atopic individuals is colonized by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). 1414 Ong PY, Leung DY. Bacterial and Viral Infections in Atopic Dermatitis: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:329-37. The diversity of skin microbiome of AD patients shows temporal shifts, with a predominance of S. aureus during flares and Streptococcus, Propionibacterium, and Corynebacterium after treatment. 1515 Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-9.

AD remains a challenging disease. Ideal treatment is targeted to long-term disease control with reduction of flares and maintenance of good quality of life. Moreover, treatment approaches depend on geographic, economic, and genotypic/phenotypic variations.

This paper aims to communicate the experience, opinions, and recommendations of Brazilian dermatology experts on atopic dermatitis treatment.

METHODS

Eighteen faculty members from 10 university hospitals with expertise in AD were appointed by the Brazilian Society of Dermatology. The first step was the application of an online questionnaire with 14 questions regarding the management of AD patients by the experts at university hospitals. Table 1 shows the compiled answers.

The second step was the analysis of recent international guidelines (American Academy of Dermatology, published in 2014, and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, published in 2018). 1616 Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-51.

17 Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, Krol A, Paller AS, Schwarzenberger K, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-32.

18 Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, Cordoro KM, Berger TG, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-49

19 Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218-33.

20 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82.-2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78. All sections and recommendations regarding AD treatment were discussed with the 18 experts, and consensus was defined as approval by at least 70% of the panel. This paper expresses their opinions regarding international guidelines for AD treatment and provides practical guidance for dermatologists in Brazil.

RESULTS/DISCUSSION

Table 1 shows the data obtained from the applied questionnaire. The majority of experts (17/18) who answered the questionnaire work in public and private institutions. About 50% of the specialists see more than 50 AD patients/month, mostly at public hospitals. Twelve out of 18 of the dermatologists follow published consensuses, with emphasis on the American and European guidelines. The most widely used topical treatments are corticosteroids, followed by calcineurin inhibitors. The first choice for systemic therapy was cyclosporin, followed by methotrexate and azathioprine.

Baseline therapy and preventive measures

The recent guidelines are in accordance regarding baseline therapy. Key steps include maintenance of the skin barrier through the constant use of emollients, which recover the function of the damaged skin barrier in AD and consequently protect the skin from allergen penetration and subsequent inflammation. 2222 Åkerström U, Reitamo S, Langeland T, Berg M, Rustad L, Korhonen L, et al. Comparison of Moisturizing Creams for the Prevention of Atopic Dermatitis Relapse: A Randomized Double-blind Controlled Multicentre Clinical Trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:587-92.

Skin hydration improves xerosis and reduces pruritus, sparing topical corticosteroid use. Cleansing eliminates crusts and reduces bacterial contamination. The use of substances with physiological pH is recommended, and baths should last no longer than five minutes. 2323 Blume-Peytavi U, Cork MJ, Faergemann J, Szczapa J, Vanaclocha F, Gelmetti C. Bathing and cleansing in newborns from day 1 to first year of life: recommendations from a European round table meeting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:751-9. Sodium hypochlorite baths (bleach) may not always change the severity of AD but appear to reduce the need for topical anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. 2424 Hon KL, Tsang YC, Lee VW, Pong NH, Ha G, Lee ST, et al. Efficacy of sodium hypochlorite (bleach) baths to reduce Staphylococcus aureus colonization in childhood onset moderate-to-severe eczema: A randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:156-62.

Daily bathing is possible for regular skin hydration, and emollients should be applied on slightly wet skin, immediately after drying; application twice daily is usually sufficient. 2525 Koutroulis I, Pyle T, Kopylov D, Little A, Gaughan J, Kratimenos P. The Association Between Bathing Habits and Severity of Atopic Dermatitis in Children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:176-81. Some emollients have additional ingredients such as urea and propylene glycol, which may lead to skin irritation, and there is still inconclusive evidence about superiority of emollients enhanced with components of the skin barrier such as ceramides. 2525 Koutroulis I, Pyle T, Kopylov D, Little A, Gaughan J, Kratimenos P. The Association Between Bathing Habits and Severity of Atopic Dermatitis in Children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:176-81.,2626 Blume-Peytavi U, Lavender T, Jenerowicz D, Ryumina I, Stalder JF, Torrelo A, et al. Recommendations from a European Roundtable Meeting on Best Practice Healthy Infant Skin Care. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:311-21.

Recent concepts regarding the microbiome and the skin highlight that the cutaneous microbiome in AD is not as heterogeneous as in healthy individuals, with the predominance of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). 1515 Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-9.,2727 Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324:1190-2. Recovery of the skin barrier by adjusting the inflammatory response reestablishes the skin microbiome in AD patients. 2828 Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, Thomas KS, Cork MJ, McLean WH, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-23.,2929 Mohan GC, Lio PA. Comparison of Dermatology and Allergy Guidelines for Atopic Dermatitis Management. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1009-13. Bacterial lysates or topical application of commensal bacteria are promising, but skin hydration itself is able to recover the skin microbiome. 1515 Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-9.,3030 Myles IA, Earland NJ, Anderson ED, Moore IN, Kieh MD, Williams KW, et al. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI Insight. 2018;3. pii: 120608

There is evidence for early use of emollients in atopic dermatitis-prone children (three months of age and older) in the prevention of AD. 2828 Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, Thomas KS, Cork MJ, McLean WH, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-23.,2929 Mohan GC, Lio PA. Comparison of Dermatology and Allergy Guidelines for Atopic Dermatitis Management. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1009-13.

Recommendations by the dermatology experts for baseline therapy:

Daily cleansing for up to 5 minutes with mild agents with adequate pH

Emollient application twice daily on slightly wet skin is the main component of baseline therapy

Aeroallergens

Aeroallergens are relevant triggering factors of AD flares.3131 Werfel T, Heratizadeh A, Niebuhr M, Kapp A, Roesner LM, Karch A, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis on grass pollen exposure in an environmental challenge chamber. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:96-103.e9.

32 Garritsen FM, ter Haar NM, Spuls PI. House dust mite reduction in the management of atopic dermatitis. A critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:688-91-3333 Lorenzini D, Pires M, Aoki V, Takaoka R, Souza RL, Vasconcellos C. Atopy patch test with Aleuroglyphus ovatus antigen in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:38-41. Exacerbation of an eczematous lesion after skin contact or inhalation has been reported, but studies are still inconclusive. 3232 Garritsen FM, ter Haar NM, Spuls PI. House dust mite reduction in the management of atopic dermatitis. A critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:688-91 The skin prick test and specific IgE are routinely utilized but have a low positive predictive value. 3232 Garritsen FM, ter Haar NM, Spuls PI. House dust mite reduction in the management of atopic dermatitis. A critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:688-91

In the present panel of dermatology experts, 89% do not perform the skin prick test or RAST as part of routine practice.

Food allergy

One-third of the children with moderate/severe AD have associated food allergy; however, food allergy is not the cause of AD. 3434 Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BA, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E8. Restrictive diets should only be prescribed for children with proven food allergy. 3434 Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BA, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E8.,3535 Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-64. The published guidelines recommend restrictive diets only for those patients with a positive oral challenge test, the gold standard assay for food allergy. 1919 Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218-33.,3434 Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BA, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E8.

35 Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-64.-3636 Thompson MM, Tofte SJ, Simpson EL, Hanifin JM. Patterns of care and referral in children with atopic dermatitis and concern for food allergy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:91-6.

The detection of specific IgE to food through prick or serological tests does not prove food allergy, and their positive predictive value is low. 3737 Cuomo B, Indirli GC, Bianchi A, Arasi S, Caimmi D, Dondi A, et al. Specific IgE and skin prick tests to diagnose allergy to fresh and baked cow's milk according to age: a systematic review. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:93.

The present panel of dermatology experts does not recommend restrictive diets, but considers that food allergy may be investigated in children with severe, treatment-resistant AD and in those with a history of flares following ingestion of specific foods.

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is present in 40-65% of AD patients, usually exacerbating the existing eczema. 3838 Herro EM, Matiz C, Sullivan K, Hamann C, Jacob SE. Frequency of contact allergens in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:39-41. The patch test is recommended for refractory AD with atypical skin lesions. 3939 Arkwright PD, Motala C, Subramanian H, Spergel J, Schneider LC, Wollenberg A, et al. Management of difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:142-51.

Patients should be tested for fragrances, preservatives, topical corticosteroids, and other topical components. 3838 Herro EM, Matiz C, Sullivan K, Hamann C, Jacob SE. Frequency of contact allergens in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:39-41. Patients are more prone to develop occupational dermatoses, since AD exacerbates the irritant effect of allergens in certain professions such as hairdressers, mechanics, metalworkers, janitorial workers, and nurses, in whom hand eczema is commonly reported. 4040 Borok J, Matiz C, Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Contact Dermatitis in Atopic Dermatitis Children-Past, Present, and Future. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018. [Epub ahead of print] Preventive measures should be taken in order to reduce the incidence of AD in such patients.

Fifty percent of the expert group recommend patch tests. The main problem is the difficulty in performing the test, since ideal sites are usually limited in AD patients.

Topical anti-inflammatory therapy

Topical anti-inflammatory therapy is the mainstay of AD treatment. Anti-inflammatory agents must have sufficient potency and should be applied on the skin lesions according to the recommendations and not exceeding the allowed amount per day. 4141 Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045-60

Topical corticosteroids (TC)

TC are the first line treatment for AD, with strong evidence of their superiority over placebo. 4242 Van Der Meer JB, Glazenburg EJ, Mulder PG, Eggink HF, Coenraads PJ. The management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults with topical fluticasone propionate. The Netherlands Adult Atopic Dermatitis Study Group. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1114-21. They are classified according to their potency based on vasoconstrictive effects, and every clinician should be aware of their potential local and systemic adverse effects, such as cutaneous atrophy and adrenal suppression.4343 Luger TA. Balancing efficacy and safety in the management of atopic dermatitis: the role of methylprednisolone aceponate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:251-8.,4444 Walsh P, Aeling JL, Huff L, Weston WL. Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression by superpotent topical steroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:501-3.

Strategies defining the use of TC vary according to their potency, but the suggested applied amounts of topical corticosteroids follow the fingertip unit rule.1919 Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218-33.,2020 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82. In the European guidelines, the approximate total amount of TC per month is 15g in infants, 30g in children, and 60-90g in adolescents and adults.2020 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82. The choice of corticosteroid and its vehicle depend on the affected site, the patients’ age and the severity and clinical phase of AD. Wet-wrap dressings may improve AD flares, and ultrahigh potent topical corticosteroids should be applied for up to two weeks.2929 Mohan GC, Lio PA. Comparison of Dermatology and Allergy Guidelines for Atopic Dermatitis Management. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1009-13.,4545 Lebwohl MG, Del Rosso JQ, Abramovits W, Berman B, Cohen DE, Guttman E, et al. Pathways to managing atopic dermatitis: consensus from the experts. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(7 Suppl):S2-S18.

TC use depends on the vehicle; as a cream, they should be applied 15 minutes before the moisturizer, and as an ointment, applied 15 minutes prior to the moisturizer.4141 Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045-60

Corticosteroid phobia is a relevant matter that should be addressed, especially due to its influence on adherence to treatment; it varies according to the country and culture.4646 Stalder JF, Aubert H, Anthoine E, Futamura M, Marcoux D, Morren MA et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: International feasibility study of the TOPICOP score. Allergy. 2017;72:1713-9.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line topical treatment for AD, according to the experts.

Calcineurin inhibitors (topical immunomodulators or TIM)

Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are second-line non-corticosteroid, anti-inflammatory therapies for AD with proven efficacy.2020 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82.,4747 Alomar A, Berth-Jones J, Bos JD, Giannetti A, Reitamo S, Ruzicka T, et al. The role of topical calcineurin inhibitors in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(Suppl 70):S3-27. The most widely reported adverse effect is burning sensation during the initial days of use (especially with tacrolimus); they do not induce skin atrophy, which makes them useful for application on eyelids, perioral lesions, axillae, and genitals.4848 Reitamo S, Rissanen J, Remitz A, Granlund H, Erkko P, Elg P, et al. Tacrolimus ointment does not affect collagen synthesis: results of a single-center randomized trial. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:396-8.

Despite a black box warning in the package insert, studies have not reported an increased risk of lymphoma with the topical use of TIM at therapeutic doses.4949 Arellano FM, Wentworth CE, Arana A, Fernández C, Paul CF.. Risk of lymphoma following exposure to calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:808-16. Intermittent use of TIM is recommended above two years of age.2020 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82.

Eighty percent of the Brazilian experts use TIM as a second-line therapy for AD.

Proactive treatment

Proactive treatment has been proposed in published guidelines. It consists of long-term use of topical anti-inflammatory agents, either TC or TIM (tacrolimus), twice a week in previously affected areas, combined with moisturizers. 2929 Mohan GC, Lio PA. Comparison of Dermatology and Allergy Guidelines for Atopic Dermatitis Management. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1009-13.,4545 Lebwohl MG, Del Rosso JQ, Abramovits W, Berman B, Cohen DE, Guttman E, et al. Pathways to managing atopic dermatitis: consensus from the experts. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(7 Suppl):S2-S18.,5050 Thaçi D, Reitamo S, Gonzalez Ensenat MA, Moss C, Boccaletti V, Cainelli T, et al. Proactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1348-56.,5151 Wollenberg A, Reitamo S, Girolomoni G, Lahfa M, Ruzicka T, Healy E, et al. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy. 2008;63:742-50. The rationale for proactive treatment is based on its efficacy and long-term safety (up to one year), reducing the number of flares and improving the quality of life of atopic patients. 5050 Thaçi D, Reitamo S, Gonzalez Ensenat MA, Moss C, Boccaletti V, Cainelli T, et al. Proactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1348-56.,5151 Wollenberg A, Reitamo S, Girolomoni G, Lahfa M, Ruzicka T, Healy E, et al. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy. 2008;63:742-50.

The Brazilian experts recommend proactive treatment with TC or TIM in AD patients.

Topical antimicrobial therapy

Colonization by S. aureus is frequent on the skin of AD patients and is much higher than in non-atopic individuals (100% vs. 30%). 5252 Orfali RL, Rivitti E, Sato MN, Takaoka R, Aoki V. Adult atopic dermatitis: Evaluation of TH17 and TH22 cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced by staphylococcal enterotoxins A and B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB68-AB.

53 Breuer K, Wittmann M, Kempe K, Kapp A, Mai U, Dittrich-Breiholz O, et al. Alphatoxin is produced by skin colonizing Staphylococcus aureus and induces a T helper type 1 response in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1088-95.-5454 Huang JT, Abrams M, Tlougan B, Rademaker A, Paller AS. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis decreases disease severity. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e808-14.Fortunately, the skin and nares of AD patients are not frequently colonized by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (7.4 and 4%, respectively). 5454 Huang JT, Abrams M, Tlougan B, Rademaker A, Paller AS. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis decreases disease severity. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e808-14.

The American Academy of Dermatology does not recommend the use of topical antibiotics, since they do not show clear benefits for AD patients. However, the use of 0.005% sodium chlorine in bathwater may be helpful in children and is recommended by the EADV. 1717 Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, Krol A, Paller AS, Schwarzenberger K, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-32.,2020 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82.

During flares, 100% of the Brazilian experts use antibiotics. About 1/3 of the experts use topical antibiotics in acute phases of AD for short periods (up to one week).

Recommendations for topical therapy in AD:

TC are the first-line treatment for AD patients and must be carefully prescribed according to their potency and vehicle. Patient’s age, site, and phase of AD lesions are key factors when choosing TC.

TIM constitute the second-line treatment for AD and are suitable for application on areas with high risk of corticosteroid-induced atrophy.

Proactive therapy with either TC or TIM is safe, reduces flares and AD severity, and is indicated as long-term maintenance therapy.

The use of topical antibiotics and antiseptics is still variable. Topical antibiotics can be used for short periods, and bleachers (0.005% sodium hypochlorite may be useful for pediatric AD).

Wet-wrap bandages or occlusive treatment during hospitalization are helpful measures for improving flares.

In patients that fail to respond to topical treatment, the following should be considered:

-

-differential diagnoses of AD

-

-lack of adherence

-

-contact dermatitis

-

-secondary infection (bacterial, viral, or fungal)

-

-indication for systemic therapy

Systemic treatment

Systemic treatment of AD is recommended in moderate to severe cases that fail to respond topical therapies. Before initiating systemic treatment, it is mandatory to avoid aggravating factors, to diagnose and treat secondary infections, and to rule out differential diagnoses. The option for systemic therapy should also include the impact of the disease on the patient’s quality of life and a careful balance of risks and benefits with the chosen medication. 5555 Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, Ardern-Jones MR, Barbarot S, Deleuran M, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:623-633.,5656 Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176-93

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is a valid adjuvant therapeutic option, especially for chronic AD and in adults. It improves pruritus, thus reducing insomnia. 5757 Garritsen FM, Brouwer MW, Limpens J, Spuls PI. Photo(chemo)therapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: an updated systematic review with implications for practice and research. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:501-13. Ultraviolet B (UVB), narrow-band UVB, and psoralen + UVA (PUVA) are the main modalities. 1212 Leung DY. New insights into atopic dermatitis: role of skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Allergol Int. 2013;62:151-61.,5757 Garritsen FM, Brouwer MW, Limpens J, Spuls PI. Photo(chemo)therapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: an updated systematic review with implications for practice and research. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:501-13. UVB-NB (311-313nm) is the most widely used form and can be indicated for children. UVA1 (340-400nm) is seldom used in Brazil but is useful for flares. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,5757 Garritsen FM, Brouwer MW, Limpens J, Spuls PI. Photo(chemo)therapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: an updated systematic review with implications for practice and research. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:501-13.

In the Brazilian consensus group, 83% recommend this treatment modality, especially for the chronic phase of AD. Phototherapy improves clinical signs and reduces pruritus and bacterial colonization, thus being a steroid-sparing measure. It is important to avoid this treatment in patients with recurrent herpes simplex infection or history of eczema herpeticum. A limiting factor for this therapeutic modality is lack of adherence to long-term treatment.

Antihistamines

Oral antihistamines that block the histamine 1 receptor (H1R) have been prescribed for AD patients for decades; however, there are few randomized studies that evaluate their real efficacy in AD. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.

The aim of systemic antihistamines in AD is to allow better quality of sleep, since their role as anti-inflammatory agents in AD is controversial. There is no evidence of improvement of severity scores in randomized studies, and first-generation drugs are prescribed due to their sedative effect and to the relief of other conditions related to AD, such as asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, dermographism, and urticaria. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,5858 Diepgen TL; Early Treatment of the Atopic Child Study Group. Long-term treatment with cetirizine of infants with atopic dermatitis: a multi-country, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (the ETAC trial) over 18 months. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:278-86. However, our group stresses that the quality of sleep induced by anti-H1R drugs is not ideal, since they do not alter the REM phase. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,5858 Diepgen TL; Early Treatment of the Atopic Child Study Group. Long-term treatment with cetirizine of infants with atopic dermatitis: a multi-country, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (the ETAC trial) over 18 months. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:278-86.

Our group recommends the use of first-generation antihistamines (hydroxyzine and chlorpheniramine) based only on their sedative effect.

Anti-inflammatory agents

Cyclosporin A (CyA)

Cyclosporin A is approved in many European countries and in Brazil for severe AD. The U.S. FDA approves it for psoriasis. The initial dose for children and adults varies from 3 to 5 mg/kg/day, and the maintenance dose is from 2.5 to 3 mg/kg/day. 5555 Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, Ardern-Jones MR, Barbarot S, Deleuran M, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:623-633.,5959 Brasch J, Becker D, Aberer W, Bircher A, Kränke B, Jung K, et al. Guideline contact dermatitis: S1-Guidelines of the German Contact Allergy Group (DKG) of the German Dermatology Society (DDG), the Information Network of Dermatological Clinics (IVDK), the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Working Group for Occupational and Environmental Dermatology (ABD) of the DDG, the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), the Professional Association of German Dermatologists (BVDD) and the DDG. Allergo J Int. 2014;23:126-38.

60 van der Schaft J, Politiek K, van den Reek JM, Christoffers WA, Kievit W, de Jong EM, et al. Drug survival for ciclosporin A in a long-term daily practice cohort of adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1621-7.-6161 Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3. Clinical improvement can be observed after 2-8 weeks; CyA is recommended for up to 2 years with constant monitoring of blood pressure and kidney function. 5555 Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, Ardern-Jones MR, Barbarot S, Deleuran M, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:623-633.,5959 Brasch J, Becker D, Aberer W, Bircher A, Kränke B, Jung K, et al. Guideline contact dermatitis: S1-Guidelines of the German Contact Allergy Group (DKG) of the German Dermatology Society (DDG), the Information Network of Dermatological Clinics (IVDK), the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Working Group for Occupational and Environmental Dermatology (ABD) of the DDG, the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), the Professional Association of German Dermatologists (BVDD) and the DDG. Allergo J Int. 2014;23:126-38.

60 van der Schaft J, Politiek K, van den Reek JM, Christoffers WA, Kievit W, de Jong EM, et al. Drug survival for ciclosporin A in a long-term daily practice cohort of adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1621-7.-6161 Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3. Periodic intervals of 3-6 months off therapy decreases the occurrence of side effects. 62 The average length of treatment with CyA is 3-12 months, and the drug is usually considered first-line treatment for treatment-resistant AD and in acute flares. 6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47. Pregnancy is not a contraindication to CyA use. 6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.

Although CyA leads to prompt improvement in severity scores after 2 weeks from the initial dose, reactivation of AD after the drug’s suspension is equally rapid, occurring in 2 weeks. 6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.

Methotrexate (MTX)

MTX can be indicated as initial treatment for moderate/severe AD, recalcitrant to topical treatment with corticosteroids. The drug has a good safety profile and is indicated for long-term maintenance; clinical efficacy is reached after 8-12 weeks of administration.2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6161 Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.

The therapeutic dose varies from 15 to 25mg/week for adults and 10-15mg/m2/week for children (oral, intravenous, or subcutaneous), and folate should be added to the treatment, usually 1-2 days after MTX. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6161 Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47. Average length of treatment ranges from 6 to 12 months, and clinical improvement is seen at 8-12 weeks from the initial dose. Side effects include hematological disorders, liver enzyme alterations, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Its use is recommended for up to 2 years, with constant monitoring of bone marrow and liver function. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6161 Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.,6464 Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, Boguniewicz M, Beck L, LeBovidge J, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:295-9.e1-27. Contraception is mandatory, since the drug is considered category X. 6161 Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.

Azathioprine (AZA)

AZA can be indicated as systemic treatment for refractory AD. Peak efficacy of AZA is reached after 8-12 weeks of use. 6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47. The initial dose is usually 50 mg/day for 1-2 weeks, increased thereafter to 2-3 mg/kg/day. 6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.,6565 Meggitt SJ, Gray JC, Reynolds NJ. Azathioprine dosed by thiopurine methyltransferase activity for moderate-to-severe atopic eczema: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:839-46. It can increase the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer and lymphoma. 66,67 Thiopurine methyltransferase enzyme (TPMT) levels should be measured whenever possible, since TPMT deficiency while in use of AZA can lead to bone marrow aplasia. 6565 Meggitt SJ, Gray JC, Reynolds NJ. Azathioprine dosed by thiopurine methyltransferase activity for moderate-to-severe atopic eczema: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:839-46. It can be prescribed for children (off label for AD) and is subject to restricted indication during pregnancy. 6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.,6868 Waxweiler WT, Agans R, Morrell DS. Systemic treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis with azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:689-94

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

Clinical efficacy of MMF is reached after 8-12 weeks of use (off label in AD), and the drug has a good safety profile. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47. The recommended doses in adults are 1-2g/day (starting dose) and 2-3g/ day (maintenance); the pediatric doses are 20-50mg/kg/day (starting dose) and 30-50mg/kg/day (maintenance).2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6868 Waxweiler WT, Agans R, Morrell DS. Systemic treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis with azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:689-94 Gastrointestinal and hematological side effects have been reported. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.

Systemic corticosteroids (SC)

There are few randomized controlled studies regarding the use of systemic corticosteroids in AD. In the 2018 European consensus, SC are used in exceptional cases of AD, but only for one week.2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78. There is a rapid clear up of skin lesions , but severe rebound tends to occur in 2 weeks. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78. One controlled trial indicates lower efficacy of systemic prednisolone in comparison to CyA in severe AD.2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,6969 Schmitt J, Schäkel K, Fölster-Holst R, Bauer A, Oertel R, Augustin M, et al. Prednisolone vs. ciclosporin for severe adult eczema. An investigator-initiated double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:661-8.

Position/recommendations for the use of systemic anti-inflammatory drugs in AD:

CyA and MTX are the most widely used systemic drugs for severe refractory AD.

CyA leads to fast improvement of AD severity scores after 2 weeks of initial treatment, but reactivation of AD after drug suspension is equally fast, occurring in 2 weeks.

MTX can be used as the initial systemic medication for refractory moderate/severe AD and is indicated for long-term maintenance. Clinical efficacy is reached after 8-12 weeks of administration.

Oral corticosteroids are used in exceptional cases for short periods (up to 1 week).

Few dermatologists have experience with mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

Treatment of secondary infections (bacterial, viral, or fungal)

S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are the most common bacterial agents in AD. They are detected in more than 90% of AD lesions.5353 Breuer K, Wittmann M, Kempe K, Kapp A, Mai U, Dittrich-Breiholz O, et al. Alphatoxin is produced by skin colonizing Staphylococcus aureus and induces a T helper type 1 response in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1088-95. Systemic antibiotics are reserved for patients with clinical evidence of infection, and cephalosporins are the first choice of treatment.2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,7070 Park HY, Kim CR, Huh IS, Jung MY, Seo EY, Park JH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Acute and Chronic Skin Lesions of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:410-6.

Extensive viral infections such as eczema herpeticum (EH) are seen in AD patients. Skin barrier defects, including mutations of the filaggrin and claudin1 genes or abnormalities in IFN-gamma response may increase the risk of EH. 1212 Leung DY. New insights into atopic dermatitis: role of skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Allergol Int. 2013;62:151-61.,7171 Leung DY, Gao PS, Grigoryev DN, Rafaels NM, Streib JE, Howell MD, et al. Human atopic dermatitis complicated by eczema herpeticum is associated with abnormalities in IFN-gamma response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:965-73.e1-5. Risk factors for EH include early severe AD, high IgE levels, eosinophilia, and associated food allergy and asthma.1414 Ong PY, Leung DY. Bacterial and Viral Infections in Atopic Dermatitis: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:329-37.,4545 Lebwohl MG, Del Rosso JQ, Abramovits W, Berman B, Cohen DE, Guttman E, et al. Pathways to managing atopic dermatitis: consensus from the experts. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(7 Suppl):S2-S18.,6363 Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.,7272 Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious Complications in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:75-93.

Treatment for localized EH is oral acyclovir. Systemic involvement with fever, lethargy, headache, nausea, and dizziness requires hospitalization and intravenous acyclovir. 7272 Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious Complications in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:75-93.

As for fungal infections in patients with AD, Malassezia spp. appears to contribute to skin inflammation during flares, and there is an anti-IgE response to immunogenic proteins released by some Malassezia species. 7373 Glatz M, Bosshard P, Schmid-Grendelmeier P. The Role of Fungi in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:63-74.

Recommendations by the Brazilian experts:

oral antibiotics are indicated when there are signs of bacterial superinfection of the skin; cephalosporins are the first choice, followed by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Eczema herpeticum must be treated with systemic antiviral drugs; when it is followed by systemic symptoms and signs, hospitalization and intravenous antiviral therapy are indicated.

AD patients with head and neck involvement may benefit from treatment with antifungal agents.

Education and AD

AD has a strong impact on the quality of life of patients and caregivers due to its chronic course and intense pruritus. 2121 Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.,4545 Lebwohl MG, Del Rosso JQ, Abramovits W, Berman B, Cohen DE, Guttman E, et al. Pathways to managing atopic dermatitis: consensus from the experts. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(7 Suppl):S2-S18.,7474 Gieler U, Köhnlein B, Schauer U, Freiling G, Stangier U. Counseling of parents with children with atopic dermatitis. Hautarzt. 1992;43(Suppl 11):S37-42. Sleep loss, school and work absenteeism, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation may be present. 5656 Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176-93,7474 Gieler U, Köhnlein B, Schauer U, Freiling G, Stangier U. Counseling of parents with children with atopic dermatitis. Hautarzt. 1992;43(Suppl 11):S37-42. Low treatment adherence is common in AD, and educational programs are needed to reinforce the patient’s understanding of the disease complexity and therapeutic approaches. 7575 Staab D, von Rueden U, Kehrt R, Erhart M, Wenninger K, Kamtsiuris P, et al. Evaluation of a parental training program for the management of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:84-90.

Various models focusing on AD education and with multidisciplinary approaches have shown subjective and objective improvement of AD worldwide. 7575 Staab D, von Rueden U, Kehrt R, Erhart M, Wenninger K, Kamtsiuris P, et al. Evaluation of a parental training program for the management of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:84-90.

76 Mancini AJ, Paller AS, Simpson EL, Ellis CN, Eichenfield LF. Improving the patient-clinician and parent-clinician partnership in atopic dermatitis management. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(3 Suppl):S23-8

77 Kupfer J, Gieler U, Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Lob-Corzilius T, Ring J, et al. Structured education program improves the coping with atopic dermatitis in children and their parents-a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:353-8.

78 Takaoka R, Aoki V. Education of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and Their Caregivers. Pediatric Allergy Immunology and Pulmonology. 2016;29:160-3.-7979 Weber MB, Lorenzini D, Reinehr CP, Lovato B. Assessment of the quality of life of pediatric patients at a center of excellence in dermatology in southern Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:697-702.

Future perspectives

Immunobiologicals and small molecules are targeted therapies that have been developed for many inflammatory, autoimmune, and oncologic diseases.

Crisaborole ointment is a topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor that was approved in the USA in 2017 for patients above the age of 2 years with mild/moderate AD. 8080 Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, Blumenthal RL, Boguniewicz M, Call RS, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody for AD that blocks the alfa-chain receptor for IL-4 and IL-13 (dupilumab) and is approved for adults with moderate/severe AD. 8181 Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Worm M, Soong W, Blauvelt A, Eckert L, et al. Dupilumab therapy provides clinically meaningful improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs): A phase IIb, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). J J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:506-15. Its efficacy after 16 weeks as monotherapy (initial dose: 600 mg, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks, SC), measured by the reduction of eczema severity scores (EASI) was 82.5% (EASI 50), 60.3% (EASI 75), and 36.5% (EASI 90).8181 Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Worm M, Soong W, Blauvelt A, Eckert L, et al. Dupilumab therapy provides clinically meaningful improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs): A phase IIb, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). J J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:506-15.

82 Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, Bieber T, Blauvelt A, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387:40-52.-8383 Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Dupilumab versus Placebo in Atopic Dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-48. Improvement of skin lesions and reduction of pruritus improved 2 weeks after initiating treatment. 8181 Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Worm M, Soong W, Blauvelt A, Eckert L, et al. Dupilumab therapy provides clinically meaningful improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs): A phase IIb, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). J J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:506-15.

82 Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, Bieber T, Blauvelt A, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387:40-52.-8383 Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Dupilumab versus Placebo in Atopic Dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-48.The studies show sustained long-term efficacy (one year) with dupilumab combined with TC in AD patients.8484 Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E, Leung DY. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad-spectrum and targeted therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4 Suppl):S65-76.,8585 Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303. The main adverse event reported with dupilumab was conjunctivitis, detected in 25-50% of AD patients.8585 Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.,8686 Wollenberg A, Ariens L, Thurau S, van Luijk C, Seegräber M, de Bruin-Weller M. Conjunctivitis occurring in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab-clinical characteristics and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1778-80.e1

There are ongoing studies (phases 2-3) with novel immunobiologicals and small molecules for AD treatment. See Chart 1. 8787 Wang D, Beck LA. Immunologic Targets in Atopic Dermatitis and Emerging Therapies: An Update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:425-43.,8888 Lee DE, Clark AK, Tran KA, Shi VY. New and emerging targeted systemic therapies: a new era for atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:364-74.

Chart 1: New systemic drugs for AD treatment. 8787 Wang D, Beck LA. Immunologic Targets in Atopic Dermatitis and Emerging Therapies: An Update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:425-43.,8888 Lee DE, Clark AK, Tran KA, Shi VY. New and emerging targeted systemic therapies: a new era for atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:364-74.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the cultural and economic differences between Brazil, USA, and Europe, including in access to immunobiological therapies, the ideal management of AD is based on a better understanding of disease pathogenesis and knowledge of treatment strategies.

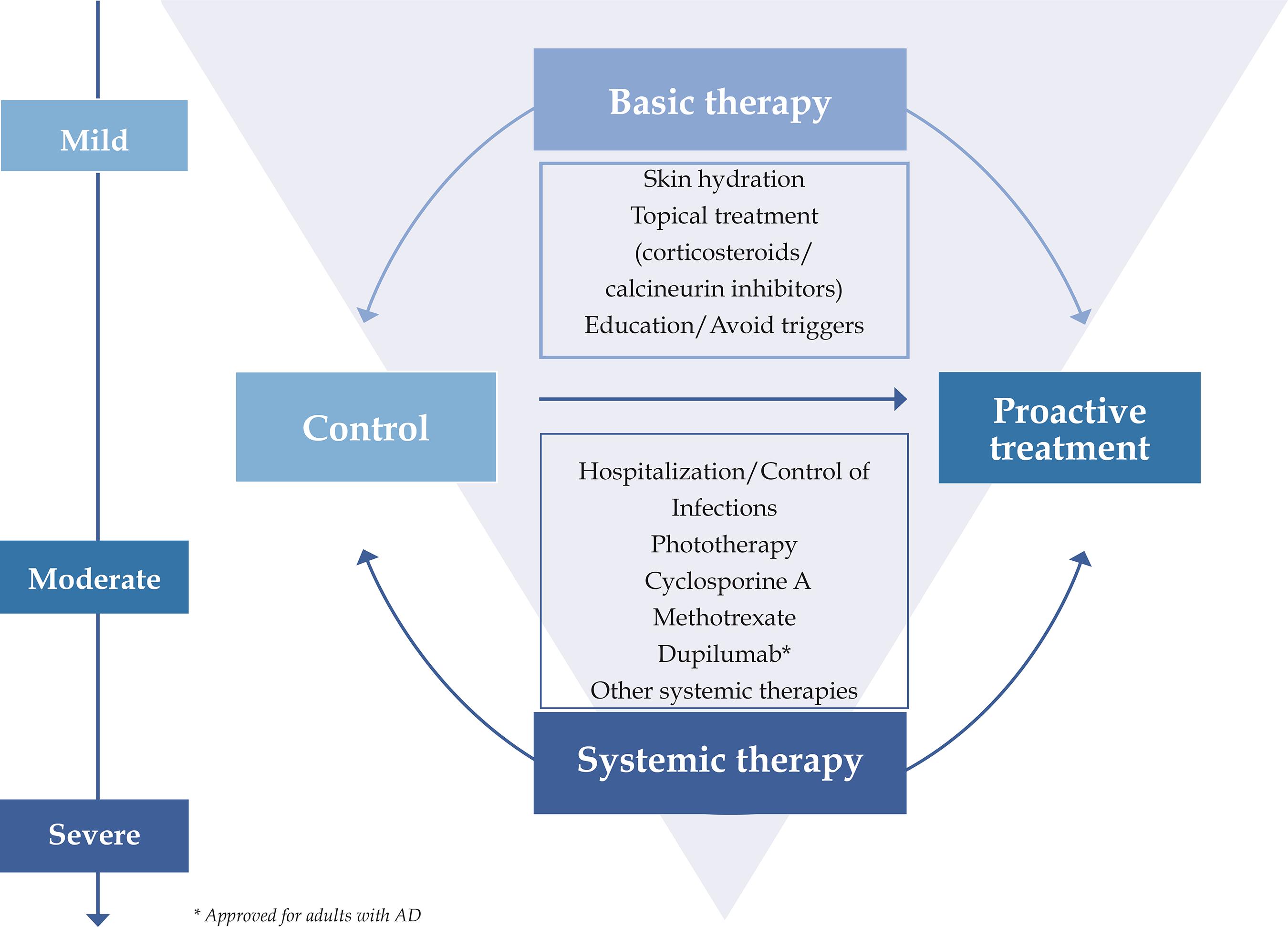

Basic treatment for AD includes skin hydration, topical anti-inflammatory therapy, avoidance of aggravating factors, and educational programs with a multidisciplinary approach. Systemic therapy should be only indicated for refractory or severe disease after attempts with topical therapy. Secondary infections must be diagnosed early and treated promptly, and hospitalization may be necessary to control flares (Figure 1).

Consensus-based recommendations of topical and systemic treatments for patients with atopic dermatitis (AD)

Novel target-oriented drugs are invaluable tools for AD treatment.

-

*

Work conducted at the Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia, Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil.

-

Financial support: None.

REFERENCES

-

1Eichenfield LF, Ellis CN, Mancini AJ, Paller AS, Simpson EL. Atopic dermatitis: epidemiology and pathogenesis update. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(3 Suppl):S3-5.

-

2Watson W, Kapur S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7( Suppl 1):S4

-

3Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, Girolomoni G, Puig L, Simpson EL, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: Results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73:1284-1293

-

4Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6 Suppl):S118-27.

-

5Ozkaya E. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:579-82.

-

6S Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Mallozi MC, Naspitz CK; Brazilian ISAAC Group. Prevalence of atopic eczema and related symptoms in Brazilian schoolchildren: results from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) phase 3. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2006;16:367-76.

-

7Orfali RL, Zaniboni MC, Aoki V. Profile of skin barrier proteins and cytokines in adults with atopic dermatitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:140-7.

-

8Batista DI, Perez L, Orfali RL, Zaniboni MC, Samorano LP, Pereira NV, et al. Profile of skin barrier proteins (filaggrin, claudins 1 and 4) and Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1091-5.

-

9Elias PM, Hatano Y, Williams ML. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1337-43.

-

10Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulewicz KJ, Wang CQ, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1344-54.

-

11Czarnowicki T, Gonzalez J, Shemer A, Malajian D, Xu H, Zheng X et al. Severe atopic dermatitis is characterized by selective expansion of circulating TH2/ TC2 and TH22/TC22, but not TH17/TC17, cells within the skin-homing T-cell population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:104-115.e7.

-

12Leung DY. New insights into atopic dermatitis: role of skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Allergol Int. 2013;62:151-61.

-

13Shi B, Bangayan NJ, Curd E, Taylor PA, Gallo RL, Leung DYM, et al. The skin microbiome is different in pediatric versus adult atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1233-6.

-

14Ong PY, Leung DY. Bacterial and Viral Infections in Atopic Dermatitis: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:329-37.

-

15Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-9.

-

16Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-51.

-

17Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, Krol A, Paller AS, Schwarzenberger K, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-32.

-

18Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, Cordoro KM, Berger TG, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-49

-

19Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218-33.

-

20Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-82.

-

21Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-78.

-

22Åkerström U, Reitamo S, Langeland T, Berg M, Rustad L, Korhonen L, et al. Comparison of Moisturizing Creams for the Prevention of Atopic Dermatitis Relapse: A Randomized Double-blind Controlled Multicentre Clinical Trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:587-92.

-

23Blume-Peytavi U, Cork MJ, Faergemann J, Szczapa J, Vanaclocha F, Gelmetti C. Bathing and cleansing in newborns from day 1 to first year of life: recommendations from a European round table meeting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:751-9.

-

24Hon KL, Tsang YC, Lee VW, Pong NH, Ha G, Lee ST, et al. Efficacy of sodium hypochlorite (bleach) baths to reduce Staphylococcus aureus colonization in childhood onset moderate-to-severe eczema: A randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:156-62.

-

25Koutroulis I, Pyle T, Kopylov D, Little A, Gaughan J, Kratimenos P. The Association Between Bathing Habits and Severity of Atopic Dermatitis in Children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:176-81.

-

26Blume-Peytavi U, Lavender T, Jenerowicz D, Ryumina I, Stalder JF, Torrelo A, et al. Recommendations from a European Roundtable Meeting on Best Practice Healthy Infant Skin Care. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:311-21.

-

27Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324:1190-2.

-

28Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, Thomas KS, Cork MJ, McLean WH, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-23.

-

29Mohan GC, Lio PA. Comparison of Dermatology and Allergy Guidelines for Atopic Dermatitis Management. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1009-13.

-

30Myles IA, Earland NJ, Anderson ED, Moore IN, Kieh MD, Williams KW, et al. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI Insight. 2018;3. pii: 120608

-

31Werfel T, Heratizadeh A, Niebuhr M, Kapp A, Roesner LM, Karch A, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis on grass pollen exposure in an environmental challenge chamber. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:96-103.e9.

-

32Garritsen FM, ter Haar NM, Spuls PI. House dust mite reduction in the management of atopic dermatitis. A critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:688-91

-

33Lorenzini D, Pires M, Aoki V, Takaoka R, Souza RL, Vasconcellos C. Atopy patch test with Aleuroglyphus ovatus antigen in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:38-41.

-

34Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BA, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E8.

-

35Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-64.

-

36Thompson MM, Tofte SJ, Simpson EL, Hanifin JM. Patterns of care and referral in children with atopic dermatitis and concern for food allergy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:91-6.

-

37Cuomo B, Indirli GC, Bianchi A, Arasi S, Caimmi D, Dondi A, et al. Specific IgE and skin prick tests to diagnose allergy to fresh and baked cow's milk according to age: a systematic review. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:93.

-

38Herro EM, Matiz C, Sullivan K, Hamann C, Jacob SE. Frequency of contact allergens in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:39-41.

-

39Arkwright PD, Motala C, Subramanian H, Spergel J, Schneider LC, Wollenberg A, et al. Management of difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:142-51.

-

40Borok J, Matiz C, Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Contact Dermatitis in Atopic Dermatitis Children-Past, Present, and Future. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]

-

41Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045-60

-

42Van Der Meer JB, Glazenburg EJ, Mulder PG, Eggink HF, Coenraads PJ. The management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults with topical fluticasone propionate. The Netherlands Adult Atopic Dermatitis Study Group. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1114-21.

-

43Luger TA. Balancing efficacy and safety in the management of atopic dermatitis: the role of methylprednisolone aceponate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:251-8.

-

44Walsh P, Aeling JL, Huff L, Weston WL. Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression by superpotent topical steroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:501-3.

-

45Lebwohl MG, Del Rosso JQ, Abramovits W, Berman B, Cohen DE, Guttman E, et al. Pathways to managing atopic dermatitis: consensus from the experts. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(7 Suppl):S2-S18.

-

46Stalder JF, Aubert H, Anthoine E, Futamura M, Marcoux D, Morren MA et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: International feasibility study of the TOPICOP score. Allergy. 2017;72:1713-9.

-

47Alomar A, Berth-Jones J, Bos JD, Giannetti A, Reitamo S, Ruzicka T, et al. The role of topical calcineurin inhibitors in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(Suppl 70):S3-27.

-

48Reitamo S, Rissanen J, Remitz A, Granlund H, Erkko P, Elg P, et al. Tacrolimus ointment does not affect collagen synthesis: results of a single-center randomized trial. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:396-8.

-

49Arellano FM, Wentworth CE, Arana A, Fernández C, Paul CF.. Risk of lymphoma following exposure to calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:808-16.

-

50Thaçi D, Reitamo S, Gonzalez Ensenat MA, Moss C, Boccaletti V, Cainelli T, et al. Proactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1348-56.

-

51Wollenberg A, Reitamo S, Girolomoni G, Lahfa M, Ruzicka T, Healy E, et al. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy. 2008;63:742-50.

-

52Orfali RL, Rivitti E, Sato MN, Takaoka R, Aoki V. Adult atopic dermatitis: Evaluation of TH17 and TH22 cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced by staphylococcal enterotoxins A and B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB68-AB.

-

53Breuer K, Wittmann M, Kempe K, Kapp A, Mai U, Dittrich-Breiholz O, et al. Alphatoxin is produced by skin colonizing Staphylococcus aureus and induces a T helper type 1 response in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1088-95.

-

54Huang JT, Abrams M, Tlougan B, Rademaker A, Paller AS. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis decreases disease severity. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e808-14.

-

55Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, Ardern-Jones MR, Barbarot S, Deleuran M, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:623-633.

-

56Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176-93

-

57Garritsen FM, Brouwer MW, Limpens J, Spuls PI. Photo(chemo)therapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: an updated systematic review with implications for practice and research. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:501-13.

-

58Diepgen TL; Early Treatment of the Atopic Child Study Group. Long-term treatment with cetirizine of infants with atopic dermatitis: a multi-country, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (the ETAC trial) over 18 months. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:278-86.

-

59Brasch J, Becker D, Aberer W, Bircher A, Kränke B, Jung K, et al. Guideline contact dermatitis: S1-Guidelines of the German Contact Allergy Group (DKG) of the German Dermatology Society (DDG), the Information Network of Dermatological Clinics (IVDK), the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Working Group for Occupational and Environmental Dermatology (ABD) of the DDG, the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), the Professional Association of German Dermatologists (BVDD) and the DDG. Allergo J Int. 2014;23:126-38.

-

60van der Schaft J, Politiek K, van den Reek JM, Christoffers WA, Kievit W, de Jong EM, et al. Drug survival for ciclosporin A in a long-term daily practice cohort of adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1621-7.

-

61Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Sallé D, Bernier C, Guillet G, Lahfa M, et al. Methotrexate Versus Cyclosporine in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:562-569.e3.

-

62van der Schaft J, van Zuilen AD, Deinum J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, de Bruin-Weller MS. Serum creatinine levels during and after long-term treatment with cyclosporine A in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:963-7.

-

63Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, Simon D, Szalai Z, Kunz B, et al. ETFAD/ EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729-47.

-

64Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, Boguniewicz M, Beck L, LeBovidge J, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:295-9.e1-27.

-

65Meggitt SJ, Gray JC, Reynolds NJ. Azathioprine dosed by thiopurine methyltransferase activity for moderate-to-severe atopic eczema: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:839-46.

-

66Khan N, Abbas AM, Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV Jr, Bazzano LA. Risk of lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with thiopurines: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1007-1015.e3.

-

67Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, Bouvier AM, Chevaux JB, Simon T, et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1621-28.e1-5.

-

68Waxweiler WT, Agans R, Morrell DS. Systemic treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis with azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:689-94

-

69Schmitt J, Schäkel K, Fölster-Holst R, Bauer A, Oertel R, Augustin M, et al. Prednisolone vs. ciclosporin for severe adult eczema. An investigator-initiated double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:661-8.

-

70Park HY, Kim CR, Huh IS, Jung MY, Seo EY, Park JH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Acute and Chronic Skin Lesions of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:410-6.

-

71Leung DY, Gao PS, Grigoryev DN, Rafaels NM, Streib JE, Howell MD, et al. Human atopic dermatitis complicated by eczema herpeticum is associated with abnormalities in IFN-gamma response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:965-73.e1-5.

-

72Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious Complications in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:75-93.

-

73Glatz M, Bosshard P, Schmid-Grendelmeier P. The Role of Fungi in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:63-74.

-

74Gieler U, Köhnlein B, Schauer U, Freiling G, Stangier U. Counseling of parents with children with atopic dermatitis. Hautarzt. 1992;43(Suppl 11):S37-42.

-

75Staab D, von Rueden U, Kehrt R, Erhart M, Wenninger K, Kamtsiuris P, et al. Evaluation of a parental training program for the management of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:84-90.

-