ABSTRACT

Background:

Sleep disturbances are common in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients and contribute to loss of life quality.

Objective:

To study associations of sleep quality with pain, depression and disease activity in RA.

Methods:

This is a transversal observational study of 112 RA patients submitted to measurement of DAS-28, Epworth scale for daily sleepiness, index of sleep quality by Pittsburg index, risk of sleep apnea by the Berlin questionnaire and degree of depression by the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale) questionnaire. We also collected epidemiological, clinical, serological and treatment data.

Results:

Only 18.5% of RA patients had sleep of good quality. In univariate analysis a bad sleep measured by Pittsburg index was associated with daily doses of prednisone (p = 0.03), DAS-28 (p = 0.01), CES-D (p = 0.0005) and showed a tendency to be associated with Berlin sleep apnea questionnaire (p = 0.06). In multivariate analysis only depression (p = 0.008) and Berlin sleep apnea questionnaire (p = 0.004) kept this association.

Conclusions:

Most of RA patients do not have a good sleep quality. Depression and risk of sleep apnea are independently associated with sleep impairment.

Keywords:

Rheumatoid arthritis; Sleep; Sleep apnea; Depression; Pain

RESUMO

Antecedentes:

Os distúrbios do sono são comuns em pacientes com artrite reumatoide (AR) e contribuem para a perda da qualidade de vida.

Objetivo:

Estudar as associações entre a qualidade do sono e a dor, depressão e atividade da doença na AR.

Métodos:

Estudo observacional transversal com 112 pacientes com AR submetidos à avaliação do DAS-28, escala de Epworth para sonolência diurna, qualidade do sono pelo índice de Pittsburg, risco de apneia do sono pelo questionário de Berlim e grau de depressão pelo questionário CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression). Também foram coletados dados epidemiológicos, clínicos, sorológicos e de tratamento.

Resultados:

Apenas 18,5% dos pacientes com AR tinham uma boa qualidade do sono. Na análise univariada, um sono ruim medido pelo índice de Pittsburg esteve associado à dose diária de prednisona (p = 0,03), DAS-28 (p = 0,01), CES-D (p = 0,0005) e mostrou uma tendência a estar associado à apneia do sono pelo questionário de Berlim (p = 0,06). Na análise multivariada, somente a depressão (p = 0,008) e a apneia do sono pelo questionário de Berlim (p = 0,004) mantiveram essa associação.

Conclusões:

A maior parte dos pacientes com AR não tem uma boa qualidade de sono. A depressão e o risco de apneia do sono estão independentemente associados ao comprometimento do sono.

Palavras-chave:

Artrite reumatoide; Sono; Apneia do sono; Depressão; Dor

Introduction

Patients’ well-being is a major concern in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Patients with RA suffer from a variety of symptoms such as joint pain and swelling, stiffness, fatigue and functional disability, that impair their quality of life. Sleep disturbances are also common in this population and contribute to the problem.11 Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52. Several studies have found sleep fragmentation, low sleep efficiency, frequent awakenings and poor sleep quality in this group of patients.11 Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52.

2 Bourguignon C, Labyak SE, Taibi D. Investigating sleep disturbances in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17:241-9.-33 Louie GH, Tektonidou MG, Caban-Martinez AJ, Ward MM. Sleep disturbances in adults with arthritis: prevalence, mediators, and subgroups at greatest risk. Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:247-60.

Nicassio et al.44 Nicassio PM, Ormseth SR, Kay M, Custodio M, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. The contribution of pain and depression to self-reported sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 2012;153:107-12. consider pain and sleep disturbance to be closely linked. However it is difficult to know which one is the primary problem. Although the inflammatory process brought by RA activity is responsible for pain initiation, investigators have found that, in some patients, pain intensity may be out of proportion to the severity of inflammation.55 Lee YC, Lu B, Edwards RR, Wasan AD, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ, et al. The role of sleep problems in central pain processing in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:59-68. It is believed that this is due to central nervous system pain amplification, mainly due to diminished conditioned pain modulation.55 Lee YC, Lu B, Edwards RR, Wasan AD, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ, et al. The role of sleep problems in central pain processing in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:59-68. Psychological distress, most notably depression and/or anxiety is another variable implicated in this relationship.11 Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52.,44 Nicassio PM, Ormseth SR, Kay M, Custodio M, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. The contribution of pain and depression to self-reported sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 2012;153:107-12.

To look further into this issue, we have studied a sample of RA Brazilian patients in order to clarify the associations of sleep quality with pain, depression and disease activity.

Methods

After approval of the local Committee of Ethics in Research and signed consent from patients we studied 112 RA patients from a single University Center. This was a convenience sample of patients that came for regular consultations in the period of one year and accepted to participate in the study. All subjects had to fulfill at least four 1987 ACR criteria for RA classification.66 Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315-24. We excluded patients with age under 18 years, with disease beginning before 16 years, pregnant women, those with uncontrolled thyroid disease or with other chronic inflammatory condition and those using sleep inductor medications. We collected demographic, clinical and serological data, values of hemoglobin, ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), CRP (C reactive protein) and DAS-28. Diurnal somnolence was evaluated by the Epworth scale,77 Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Pedro VD, Menna Barreto SS, Johns MW. Portuguese-language version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: validation for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:877-83. the index of sleep quality by the Pittsburg index,88 Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Dartora EG, Miozzo IC, de Barba ME, et al. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med. 2011;12:70-5. and the risk of sleep apnea by the Berlin questionnaire.99 Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485-91. Depression was measured by the CES-D Questionnaire or Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.1010 da Silveira DX, Jorge MR. Reliability and factor structure of the Brazilian version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression. Psychol Rep. 2002;91(3 Pt 1):865-74. All the applied instruments were translated and validated for the Portuguese language. Fatigue and global health were measured by a visual analogic scale from 0 (none) to 100 (maximal).

Patients were divided in those with good and poor sleep quality according to the Pittsburg index (equal or lower than 5 = good sleep; >5 = sleep disorder) and these two samples were compared. For this comparison we used Fisher and chi-squared tests for nominal data and Mann Whitney and unpaired t test for numerical data. Associations with p ≤ 0.10 were studied through linear regression to test the variables independence. Significance adopted was of 5%.

Results

Overview of studied sample and prevalence of sleep disturbances

In the 112 RA patients, 83.1% were female, with age ranging from 21 to 77 years (mean 55.4 ± 10.9 years) and disease duration from 9 months to 53 years (median 11 years; IQR or interquartile rate = 5-18). Auto declared Afro descendants were 19.6%; 1.7% Asiatic descendants and 78.5% Caucasians. Tobacco exposure occurred in 39.2% while 60.3% never smoked. The body mass index varied from 17.3 to 46.4 kg/m2 (median of 27.5; IQR = 24.3-31.5 kg/m2). Rheumatoid factor (RF) was present in 59.6%; anti-CCP in 47.6%; ANA (antinuclear antibody) in 34.9%.

Treatment profile at the time of study showed that prednisone was used in 71.4% (doses from 5.0 to 60.0 mg; median 5.0; IQR = 5.0-10.0); methotrexate in 73.2%, antimalarial in 21.4%, leflunomide in 43.7%, anti TNF-alpha in 5.3% and abatacept in 2.6%.

Table 1 shows the results of laboratory tests and applied questionnaires.

Comparison study of RA patients with good and poor sleep quality

Studying the comparison of patients with and without good sleep quality according to the Pittsburg index we obtained the results in Table 2.

Comparison of demographic, laboratorial, serological and treatment data in rheumatoid arthritis patients according to sleep quality measured by Pittsburg index (good sleep ≤ 5; sleep disorder > 5).

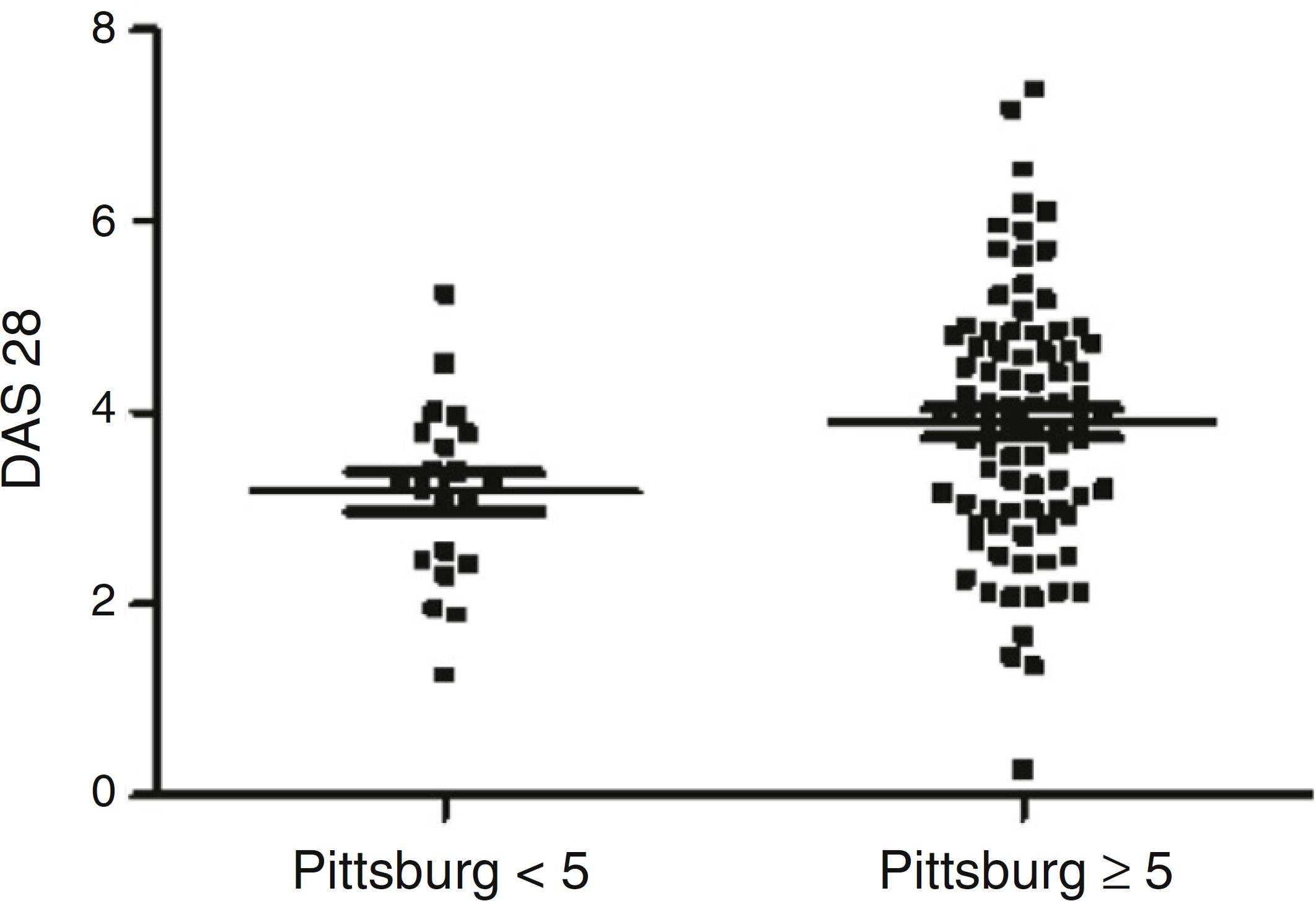

The result of DAS 28 (ESR) in the samples with and without good sleep quality is seen in Fig. 1.

Comparison of DAS-28 (ESR) according to sleep quality measured by Pittsburg index (p = 0.01; Mann Whitney). Comparison of ESR with p = 0.12; global VAS with p = 0.43; number of swollen joints with p = 0.31; number of painful joints with p = 0.005.

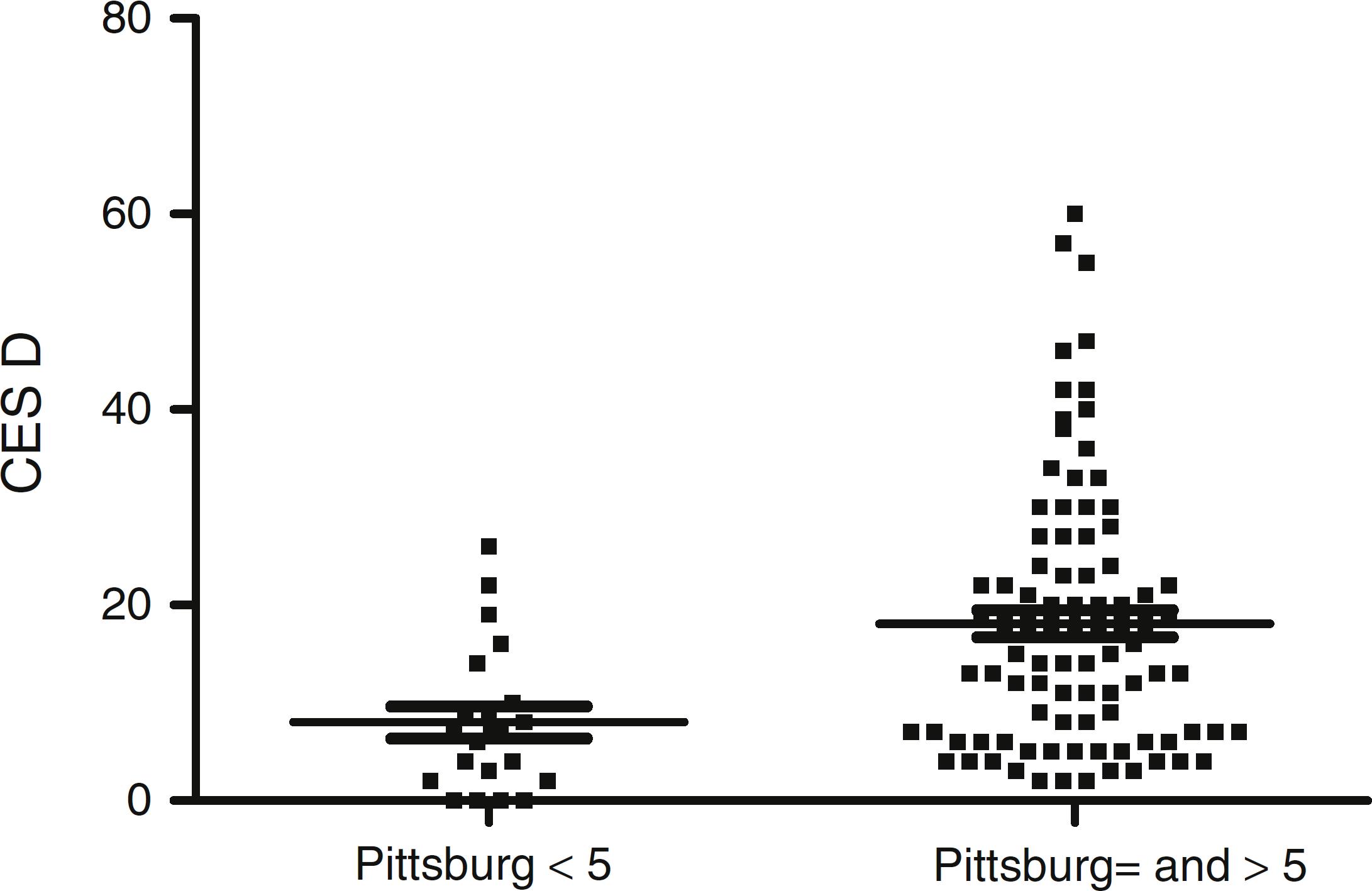

The comparison of VAS fatigue, Epworth sleepiness scale and Berlin sleep apnea screening questionnaire showed respectively p = 0.04, p = 0.84 and p = 0.06 (Mann Whitney). The result of association of Pittsburg index with depression (CES-D) is in Fig. 2.

Association study of depression measured by CES-D and sleep quality measured by Pittsburg index (p = 0.0005).

In a multiple regression study that included daily doses of prednisone, VAS fatigue, number of tender joints, results of Berlin sleep apnea screening questionnaire, Depression CES-D questionnaire and number of painful joints (from DAS 28), we found that the Pittsburg index associated independently with CES-D depression questionnaire (p = 0.008) and Berlin apnea screening questionnaire (p = 0.004).

Discussion

One of the most striking findings of the present study is that less than 20% of RA patients have a sleep of good quality. This must be taken into account in daily practice if one intends to improve patients’ quality of life. This high prevalence of sleep disorder has already been noted by others.11 Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52.

2 Bourguignon C, Labyak SE, Taibi D. Investigating sleep disturbances in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17:241-9.

3 Louie GH, Tektonidou MG, Caban-Martinez AJ, Ward MM. Sleep disturbances in adults with arthritis: prevalence, mediators, and subgroups at greatest risk. Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:247-60.-44 Nicassio PM, Ormseth SR, Kay M, Custodio M, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. The contribution of pain and depression to self-reported sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 2012;153:107-12.

In this study, univariate analysis disclosed association of poor sleep with DAS 28, daily dose of prednisone, fatigue, depression and risk of sleep apnea. Sariyildiz et al.11 Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52. and Son et al.1111 Son CN, Choi G, Lee SY, Lee JM, Lee TH, Jeong HJ, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis, and its association with disease activity in a Korean population. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:384-90. have also found association of disease activity with poor sleep quality. Some studies have documented qualitative alterations and rupture in sleep continuity in relationship with certain immunological factors.1212 Krueger JM, Obal FJ, Faig J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:211-21. In RA, circulating TNF-α is increased and there has been a suggestion that the level of this cytokine may be connected to sleep disorders.1212 Krueger JM, Obal FJ, Faig J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:211-21. Brain levels of IL-1 and TNFα are linked with sleep deprivation.1212 Krueger JM, Obal FJ, Faig J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:211-21. One study1313 Taylor-Gjevre RM, Gjevre JA, Nair BV, Skomro RP, Lim HJ. Improved sleep efficiency after anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2011;3:227-33. conducted in ten RA patients to assess whether anti TNF drugs had any effect on the sleep pattern suggested that its quality improved with this type of medication.

However, in the present study, when the elements that are included in the DAS 28 were examined apart, the number of tender joint was the component responsible for the association. Thus, pain and not inflammation could be the real association. Sleep disturbance in patients with joint pain has been noted not only in RA but in other chronic painful conditions.1414 Brown GK. A causal analysis of chronic pain and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:127-37.

The daily dose of prednisone was also related to lower performance in the Pittsburg score in univariate analysis. Endogenous glucocorticoids are critical for the pathogenesis of sustained stress-related sleep disorders.1515 Wang ZJ, Zhang XQ, Cui XY, Cui SY, Yu B, Sheng ZF, et al. Glucocorticoid receptors in the locus coeruleus mediate sleep disorders caused by repeated corticosterone treatment. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9442. High serum levels of glucocorticoids induce poor sleep quality and shorter sleep duration through receptors that are highly expressed in the brain.1616 Bradbury M, Dement WC, Edgar DM. Effects of adrenalectomy and subsequent corticosterone replacement on rat sleep state and EEG power spectra. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R555-65. Nevertheless, higher doses of prednisone are used by patients with more inflammation and it is possible that, again, pain resulting from the inflammatory process could be the true responsible for the relationship.

The Berlin apnea screening questionnaire displayed an independent association with poor sleep in RA. Drossaers-Baker et al.1717 Drossaers-Bakker KW, Hamburger HL, Bongartz EB, Dijkmans BA, Van Soesbergen RM. Sleep apnoea caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:889-94. showed that sleep apnea in their RA patients was due to a mixed pattern: central and obstructive, suggesting that this problem is multifactorial. Contributors to the obstructive component could be increased neck circumference by glucocorticoid use, narrowing of upper airway by changes in temporomandibular joint, reposition of cervical axis in cases of cervical subluxation or even by diminished muscle tone in the airway.1717 Drossaers-Bakker KW, Hamburger HL, Bongartz EB, Dijkmans BA, Van Soesbergen RM. Sleep apnoea caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:889-94. A high BMI is also common in RA patients and was found in 60% of this sample. Vertical luxation of the odontoid process may cause compression of the brain stem and could result in central impairment of breathing.1818 Hamilton J, Dagg K, Sturrock R, Anderson J, Banham S. Sleep apnoea caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:679-80. Patients with hypoventilation complain of headache upon awakening, nocturnal unrest, day-time sleepiness and impaired concentration.1919 Walsh JA, Duffin KC, Crim J, Clegg DO. Lower frequency of obstructive sleep apnea in spondyloarthritis patients taking TNF-inhibitors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:643-8. These symptoms are often mild and may be easily overlooked. Curiously, anti TNF drugs are also described as improving the sleep apnea syndrome.1919 Walsh JA, Duffin KC, Crim J, Clegg DO. Lower frequency of obstructive sleep apnea in spondyloarthritis patients taking TNF-inhibitors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:643-8. In our sample the number of patients using this type of drug was too small to allow any conclusions.

Finally, depression was independently linked to poor sleep quality. Depression is a highly prevalent problem in RA11 Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52. and contributes to disability, bad adherence to treatment, and poor social functioning. Insomnia in depressed patients was first considered to be a symptom of depression.2020 Maglione JE, Ancoli-Israel S, Peters KW, Paudel ML, Yaffe K, Ensrud KE. Depressive symptoms and subjective and objective sleep in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:635-43. More recently there is evidence to sustain that there is a bidirectional connection between these two variables. According to some studies, sleep disorder is also a major risk factor for future onset and for recurrence of depressive episodes.2121 Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:473-81.,2222 Perlis ML, Smith LJ, Lyness JM, Matteson SR, Pigeon WR, Jungquist CR, et al. Insomnia as a risk factor for onset of depression in the elderly. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4:104-13.

Concluding, the present data show a high prevalence of poor sleep in RA patients and that the main associated factors are sleep apnea and depression.

REFERENCES

-

1Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, Yazmalar L, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44-52.

-

2Bourguignon C, Labyak SE, Taibi D. Investigating sleep disturbances in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17:241-9.

-

3Louie GH, Tektonidou MG, Caban-Martinez AJ, Ward MM. Sleep disturbances in adults with arthritis: prevalence, mediators, and subgroups at greatest risk. Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:247-60.

-

4Nicassio PM, Ormseth SR, Kay M, Custodio M, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. The contribution of pain and depression to self-reported sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 2012;153:107-12.

-

5Lee YC, Lu B, Edwards RR, Wasan AD, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ, et al. The role of sleep problems in central pain processing in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:59-68.

-

6Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315-24.

-

7Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Pedro VD, Menna Barreto SS, Johns MW. Portuguese-language version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: validation for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:877-83.

-

8Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Dartora EG, Miozzo IC, de Barba ME, et al. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med. 2011;12:70-5.

-

9Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485-91.

-

10da Silveira DX, Jorge MR. Reliability and factor structure of the Brazilian version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression. Psychol Rep. 2002;91(3 Pt 1):865-74.

-

11Son CN, Choi G, Lee SY, Lee JM, Lee TH, Jeong HJ, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis, and its association with disease activity in a Korean population. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:384-90.

-

12Krueger JM, Obal FJ, Faig J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:211-21.

-

13Taylor-Gjevre RM, Gjevre JA, Nair BV, Skomro RP, Lim HJ. Improved sleep efficiency after anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2011;3:227-33.

-

14Brown GK. A causal analysis of chronic pain and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:127-37.

-

15Wang ZJ, Zhang XQ, Cui XY, Cui SY, Yu B, Sheng ZF, et al. Glucocorticoid receptors in the locus coeruleus mediate sleep disorders caused by repeated corticosterone treatment. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9442.

-

16Bradbury M, Dement WC, Edgar DM. Effects of adrenalectomy and subsequent corticosterone replacement on rat sleep state and EEG power spectra. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R555-65.

-

17Drossaers-Bakker KW, Hamburger HL, Bongartz EB, Dijkmans BA, Van Soesbergen RM. Sleep apnoea caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:889-94.

-

18Hamilton J, Dagg K, Sturrock R, Anderson J, Banham S. Sleep apnoea caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:679-80.

-

19Walsh JA, Duffin KC, Crim J, Clegg DO. Lower frequency of obstructive sleep apnea in spondyloarthritis patients taking TNF-inhibitors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:643-8.

-

20Maglione JE, Ancoli-Israel S, Peters KW, Paudel ML, Yaffe K, Ensrud KE. Depressive symptoms and subjective and objective sleep in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:635-43.

-

21Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:473-81.

-

22Perlis ML, Smith LJ, Lyness JM, Matteson SR, Pigeon WR, Jungquist CR, et al. Insomnia as a risk factor for onset of depression in the elderly. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4:104-13.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Jul-Aug 2017

History

-

Received

10 Nov 2015 -

Accepted

15 June 2016