Abstracts

The interaction between art and science was high during the Renaissance and it declined later to return significantly in the 20th century, mainly with the use of identification techniques, dating of art works and the development of new materials. The relationship between plastic arts and hand surgery is intense and artistic reproductions of hands are frequent in the illustration of scientific texts. With the objective of understanding the role of the hand in plastic arts, reproductions of works of art (sculptures and paintings) representative of several periods or styles in the history of art were analyzed emphasizing the study of the hands. Anatomical details, relationship with other structures of the human body, role in the composition and symbolic aspects of the hands were studied in historical and artistic contexts of art works in the Paleolithic period (pre-history) until the 20th century. The representation of the hands in plastic arts is directly related to the style or period of the work and to the individual ability of interpretation and execution by the artist.

Hand; art; history of the art

A interação entre arte e ciência foi intensa durante o Renascimento, sofrendo declínio nos anos posteriores com retomada significativa no século XX, principalmente com o uso de técnicas de identificação, datação de obras de arte e o desenvolvimento de novos materiais. O relacionamento entre artes plásticas e Cirurgia da Mão mantêm-se intenso , sendo freqüente o uso de reproduções artísticas da mão nas ilustrações de textos científicos. Objetivando compreender o papel da mão nas artes plásticas, reproduções de obras de artes (esculturas e pinturas) representativas de vários estilos ou períodos da história da arte foram analisadas com enfoque no estudo das mãos. Detalhes anatômicos, relacionamento com outras estruturas do corpo humano, papel na composição e aspectos simbólicos das mãos foram estudados no contexto histórico e artístico de obras de arte do período paleolítico (pré-história) até o século XX. A representação da mão nas artes plásticas está diretamente relacionada ao estilo ou período da obra e à capacidade individual de interpretação e execução do artista.

Mão; arte; história da arte

Evolution of representation of the hands in plastic arts

A evolução da representação da mão nas artes plásticas

Trajano SardenbergI; Gilberto José Cação PereiraI; Cleide Santos Costa BiancardiII; Sergio Swain MüllerIII; Hamilton da Rosa PereiraIII

IAssistant Professor

IIPhD Assitant Professor

IIIPhD Assistant Professor

Address for correspondence Address for correspondence Department of Surgery and Orthopedics, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu, UNESP CEP 18618-970 Botucatu, SP Email: tsarden@fmb.unesp.br

SUMMARY

The interaction between art and science was high during the Renaissance and it declined later to return significantly in the 20th century, mainly with the use of identification techniques, dating of art works and the development of new materials. The relationship between plastic arts and hand surgery is intense and artistic reproductions of hands are frequent in the illustration of scientific texts.

With the objective of understanding the role of the hand in plastic arts, reproductions of works of art (sculptures and paintings) representative of several periods or styles in the history of art were analyzed emphasizing the study of the hands. Anatomical details, relationship with other structures of the human body, role in the composition and symbolic aspects of the hands were studied in historical and artistic contexts of art works in the Paleolithic period (pre-history) until the 20th century. The representation of the hands in plastic arts is directly related to the style or period of the work and to the individual ability of interpretation and execution by the artist.

Key words: Hand; art; history of the art

RESUMO

A interação entre arte e ciência foi intensa durante o Renascimento, sofrendo declínio nos anos posteriores com retomada significativa no século XX, principalmente com o uso de técnicas de identificação, datação de obras de arte e o desenvolvimento de novos materiais. O relacionamento entre artes plásticas e Cirurgia da Mão mantêm-se intenso , sendo freqüente o uso de reproduções artísticas da mão nas ilustrações de textos científicos.

Objetivando compreender o papel da mão nas artes plásticas, reproduções de obras de artes (esculturas e pinturas) representativas de vários estilos ou períodos da história da arte foram analisadas com enfoque no estudo das mãos. Detalhes anatômicos, relacionamento com outras estruturas do corpo humano, papel na composição e aspectos simbólicos das mãos foram estudados no contexto histórico e artístico de obras de arte do período paleolítico (pré-história) até o século XX. A representação da mão nas artes plásticas está diretamente relacionada ao estilo ou período da obra e à capacidade individual de interpretação e execução do artista.

Descritores: Mão; arte; história da arte

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between plastic arts and Hand Surgery is constant both in professional and academic life of doctors who are dedicated to this surgical specialty. Classic and contemporary books on Hand Surgery constantly use reproductions of art works for their covers, such as the 1967's Spanish edition of Bunnell and Boyes book ¾ Cirurgía de La Mano, and the 1998's edition of the instructions manual of the AO/ASIF Hand Course. The scientific journal Acta Ortopaedica Scandinavica uses to publish in its covers reproductions of art works since 1991, being part of the issues linked to themes related to the upper limb.

The interaction between art and science, present during all human history, reached an overwhelming intensity during the Renaissance, declining in the following years with a significant retake in the XX Century, mostly with the use of identification and dating of art works and the development of new materials. In parallel, due to the intensive involvement with anatomy of upper extremity, Hand Surgery has kept strong links to plastic arts.

Scientific journals specialized in Hand Surgery use to reflect the medical area interest in artistic representations of the hand, publishing articles on this theme, such as the series in the Journal of Hand Surgery on the works by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Pablo Picasso and the chronicle by Verdan in the Annales de Chirurgie de La Main(12,13,14,18).

The history of Medicine has frequently used art works for the study of the evolution of techniques of treatment and knowledge of diseases. Hand deformities caused by Rheumatoid Arthritis were studied through detailed observation of art works, mainly the paintings by Flemish painters, generating important knowledge on the origins of this disease(1,2,3, 4,5,6,11,15,17).

Biological human inheritance behaves in a similar way as all other living beings, following contemporary Darwinian rules, with no transmission to the next generation of characteristics developed by the preceding generation. On the other hand, cultural inheritance of human beings is Lamarckian, involving transmission of knowledge and techniques developed by one generation to the future one(9). Studies of evolution of the hand performed by Paleontology contributed to the understanding of the functioning of the hand and, consequently, to the development of treatment of its diseases. The study of the evolution of the artistic representation of the hand can give elements for a better understanding of the man's view on his own anatomy and relationship to the environment.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Copies of art works, representative from several periods and stiles of the History of World Art (Table 1) involving representation of the hand, were selected and analyzed with a special focus on hands.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

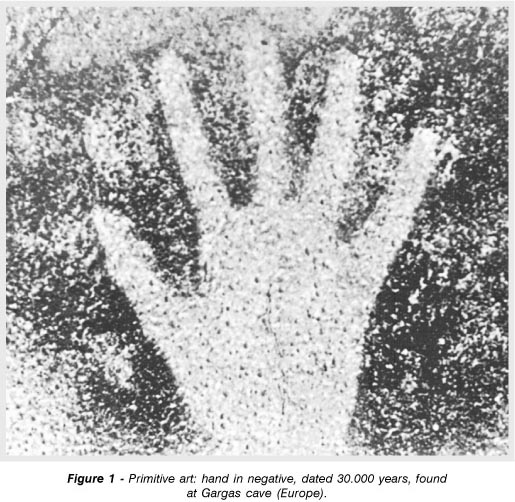

Primitive art: The 30.000 years old "hands in negative" found in the Gargas Cave were done by blowing ink, got from a mixture of coal and iron oxide (black) or manganese oxide (red) mixed to fat or blood, with the use of a bone tube over the hand resting on the wall. The majority of these hands were left, indicating a majority of right hand dominance, and some do not have the distal extremity of the fingers, indicating traumatic sequelae or religious sacrifices(10) (Figure1).

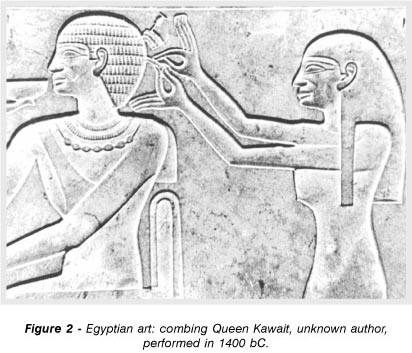

Egyptian art: The art done for the eternity and for the world of the dead followed rigid patterns. The hands of the slave combing Queen Kawait hairs (1400 bC) are shown in a lateral view, the fingers are all represented in similar sizes and the first commissure is emphasized, with no concern on anatomical details (Figure 2).

Greek art: The work "Discobolo" created by the Greek artist Myron in 450 bC was performed in bronze and probably melted, and today one observe an Italian copy in marble. The image features precise details of the external anatomy and, most importantly, gets to transmit the impression of real movement. The left hand is perfect, with all details of real and ideal anatomy (Figure 3).

Medieval art: The scene represented in the Book of the Gospels of Otto III (1000 aC) refers to the Gospel of St. John, where he reports the episode after the last Supper, when Christ washed the feet of the apostles. The artist was fundamentally concerned in representing the essence of the report by St. John, with no concern on technique details. The background is simple and without any perspective; the central scene is Christ's blessing in face of the supplicant gesture by Peter(7). Christ's hands are simple, and the right one has flexion of fingers 4th and 5th. Peter's hands have some size proportionality of the fingers, and the first commissure is enhanced, and a drawing of the hypothenar eminence of the left hand is represented (Figure 4).

Renaissance: The "Creation of Adam", by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in 1511, demonstrates that anatomical precision together with movement sensation is able to express all human soul. Adam, laying on the ground, exhibits all beauty and vigor of the first man and looks to awake from a deep sleep, keeping his wrist lightly flexed and the fingers extended, due to the effect of the tenodesis by the extensor tendons, except for the index finger, in more extension and directed to God Father, who presents the wrist in neutral position and the index finger extended in order to touch and give life to his mud creation. Michelangelo, who considered himself more as an sculptor than as a painter, "sculpted" his characters on the walls of the Sistine Chapel(8).(Figure 5).

Baroque: The gospel by John is clear to state that Thomas needed not only to see, but also to touch Christ's wounds in order to believe in his resurrection. Caravaggio, painting the picture "Thomas, the unbeliever" (1600) disrupts the harmony of the classicism of Renaissance and brings the realistic naturalism to painting. Thomas' rude hand is anatomically perfect and, it is real, showing dirty under the thumb nail (Figure 6).

Neoclassicism: J.L. David, a French artist, who was sectarian of the French Revolution and friend of the leaders Roberspierre, Danton and Marat is one of the major responsibles for the regress of classicism in European painting of XVIII Century. Marat, a revolutionary leader and hero of the French people, used to work while bathing for treatment of skin lesions, probably psoriasis, when he was demanded by a fanatic counter-revolutionary woman to analyze a request, and, when about to sign it, was stabbed in the thorax. The treatment David used in the picture "Marat murdered" (1793) is centered on the principal elements of the facts, such as the knife, the plume and the letter from the murder. The hero of the people is represented as a saint, in a posture similar to the one of Christ in the "Pieta" by Michelangelo (16). The left hand presents a latero-lateral pinch, with the thumb and the index holding the letter of the murder (Figure 7).

Impressionism: Paul Cézanne presented a new treatment for surface appearance, not imitating the reality, but trying to penetrate the geometries underlying the objects, landscapes, men and women. In his picture "Card players" (1890), the composition is centered on the upper limbs, trunk and head of the characters, closing a circle that looks for drawing the attention to the hands with cards and the bottle over the table; nevertheless it is a portrait, it is treated as dead nature. There is no concern on details in representing the hands (Figure 8).

Modernism: In 1936, during the Spanish Civil War, the nazi German air force performed war training by bombing a small Basque village without any strategic military value, called Guernica. The Spanish artist, Picasso, represented his affliction and anger in his picture "Guernica" (1936). Using the colors white, black and grades of gray, the artist filled the screen with images of animals and human beings in a totally desperate status. Distorted and broken faces and hands transmit the feelings of anger and perplexity of the artist facing the war tragedy (Figure 9).

Contemporary art: Nowadays artists broke with the screen ground and the space of sculpture, using creation of surroundings, called installations, constructed with the most variable objects and materials looking for expressing their feelings and interact with public. The Brazilian artist Nazaré Pacheco, in an installation (1994), performs an autobiographic trip composing a surrounding with plaster of normal hands of friends in contrast with a model of her own hands deformed by a congenital abnormality (Figure 10).

CONCLUSIONS

The hand has as a neurological feature, of presenting a representation area in brain that is disproportional to its dimension in the human body, and this fact was demonstrated by the "homunculus" proposed by Penfield and Rasmussen.

The representation of the hands in plastic arts, in a similar way, has a primordial role in the esthetic and symbolic contents of art works and, the aspect of the hands is directly related to the stile of the era and to the artist's individual capacity of interpretation and execution. The prominence of the hands in art is proportional to its importance as a segment of the human body which is fundamental for survival, technical and artistic culture and above all, for the expression of the relationship between the human beings.

Trabalho recebido em 01/11/2001. Aprovado em 15/05/2002

Work performed at Department of Surgery and Orthopedics of Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu - UNESP and at Arts Department of Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação de Bauru - UNESP.

- 1. Alarcón-Segovia, D.: Pré - Columbian representation of Heberden's nodes. Arthritis Rheum 19:125-126, 1976.

- 2. Alarcón-Segovia, D., Laffón, A., Alcocer-Varelar, J.: Probable depiction of juvenile arthritis by Sandro Botticelli. Arthritis Rheum 26: 1266-1268, 1983.

- 3. Appelboom, T., Boelpaepe, C., Ehrlich, G. E., Famaey, J. P.: Rubens and the question of antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA 245: 483-486, 1981.

- 4.Dequeker, J.: Arthritis in flemish paintings (1400-1700). BMJ 1:1203-1205, 1977.

- 5. Dequeker, J.: Siebrandus Sixtius: evidence of rheumatoid arthritis of the robust reaction type in a seventeenth century dutch priest. Ann Rheum Dis 51: 561-562, 1992.

- 6. Dequeker, J., Rico. H.: Rheumatoid arthritir like deformities in a early 16th century painting of the flemish-dutch shool. JAMA 268: 249-251, 1992.

- 7. Gombrich, E. H.: A arte ocidental em fase de assimilação; in A história da arte. Rio de Janeiro, Guanabara Koogan, 1993, p.113-124.

- 8. Gombrich, E. H.: Realização da harmonia; in A história da arte. Rio de Janeiro, Guanabara Koogan, 1993, p.217-245.

- 9. Gould, S. J.: Sombras de Lamark; in O polegar do panda. São Paulo, Livraria Martins, 1989, p.65-72.

- 10. Napier, J.: Destreza manual; in A mão do homem - anatomia, função, evolução. Rio de Janeiro, Zahar Editores, 1983, p.137-146.

- 11. Panush, R. B., Cardwell, J. R., Panush, R. S.: Corot's "Gout" and a "Gipsy"girl. JAMA 264: 1136-1138, 1990.

- 12. Robins, N., Robins, R.: Hands and the artist - Henry Moore. J Hand Surg 12B: 141-143, 1987.

- 13. Robins, R., Robins, N.: Hands and the artist - Barbara Hepworth. J Hand Surg 13B: 104-107, 1988.

- 14. Robins, N., Robins, R.: Hands and the artist. Pablo Picasso. J Hand Surg 15B:131-134, 1990.

- 15. Short, C. L.: The antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 17:193-205, 1974.

- 16. Strickland, C., Boswell, J.: Neoclassicismo: febre romana; in Arte comentada - da pré-história ao pós-moderno. Rio de Janeiro, Ediouro Publicações, 1999, p. 68-69.

- 17. Talbott, J. H.: Medical maladies as seen by the artist ¾ editorial. JAMA 245:497-498, 1981.

- 18. Verdan, C.: La main dans les arts. Ann Chir Main 8:182-188, 1989.

- 19. Wilson, F. R.: Notes; in The hand. New York, Pantheon Books, 1998, p. 320-321.

Address for correspondence

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

25 Feb 2003 -

Date of issue

Sept 2002

History

-

Accepted

15 May 2002 -

Received

01 Nov 2001